Abstract

Patient: Female, 45

Final Diagnosis: Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH)

Symptoms: Dyspnea • fatigue • palpitations

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Right heart catheterization • pulmonary endarterectomy

Specialty: Pulmonology

Objective:

Mistake in diagnosis

Background:

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension most often results from obstruction of the pulmonary vascular bed by nonresolving thromboemboli. Misdiagnosis of the disease is common because patients often present with subtle or nonspecific symptoms. Furthermore, some features in chest imaging may mimic parenchymal lung disease. The most clinically important mimic in high-resolution chest tomography is air trapping, which can be seen in a variety of small airway diseases.

Case Report:

We present the case of a 45-year-old woman with a long history of dyspnea and exercise intolerance, misdiagnosed with allergic alveolitis. The diagnosis of CTEPH was finally established with computed tomography (CT) angiography and hemodynamics.

Conclusions:

Chronic thromboembolism is under-diagnosed and also frequently misdiagnosed in clinical practice. The present report aims to increase the awareness of clinicians towards an accurate diagnosis of the disease, which is necessary for the early referral of CTEPH patients for operability.

MeSH Keywords: Diagnostic Imaging; Embolism and Thrombosis; Hypertension, Pulmonary

Background

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) results from obstruction of pulmonary vessels with organized blood clots [1]. The disease develops after acute or recurrent pulmonary emboli and has been associated with the presence of coagulation abnormalities and chronic inflammatory disorders. However, a majority of CTEPH cases may originate from asymptomatic venous thromboembolism. In this case, the signs and symptoms of the disease are relatively subtle and can be easily missed. We present the case of a 45-year-old woman with a long history of dyspnea and exercise intolerance that was finally diagnosed with CTEPH. The present report aims to increase the awareness of clinicians towards an accurate diagnosis of the disease.

Case Report

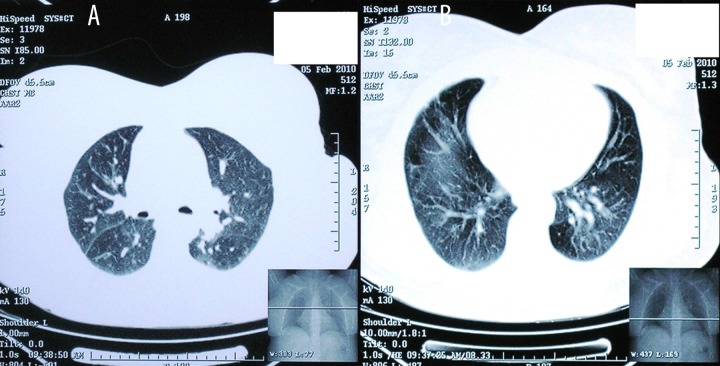

A 45-year-old woman presented to the Pulmonary Department with dyspnea on exertion, fatigue, and palpitations during the past 24 months. Her medical history included hypothyroidism (under hormone replacement with levothyroxine sodium) and type II diabetes treated with a combination of glimepiride, metformin, and sitagliptin. She was an ex-smoker with a history of smoking 5–8 cigarettes/day for 10 years. Chest X-ray demonstrated diffuse lung infiltrates and high-resolution computed tomography showed extensive ground-glass opacities prominent in the upper lobes (Figure 1A, 1B). Extrinsic allergic alveolitis, sarcoidosis, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia were initially considered in differential diagnosis. Blood gas analysis on room air revealed mild hypoxemia with a pH of 7.48, partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) 58 mm Hg, and partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) 35 mm Hg, with an oxygen saturation of 90%. Pulmonary function tests revealed a mild restrictive ventilatory defect with an FEV1 of 2.28 lt (80% of predicted), FVC 2.83 lt (86% of predicted), and TLC 3.91 lt (76% of predicted), whereas diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLco) was markedly reduced (59% of predicted). Bronchoalveolar lavage showed increased the number of T-lymphocytes, with a predominance of CD8+ subset. The patient was diagnosed with extrinsic allergic alveolitis and she was started on 32 mg of methylprednisolone per day.

Figure 1.

(A, B) High-resolution computed tomography demonstrating mosaic perfusion. Areas of pulmonary hyperperfusion are of high attenuation and are associated with large vessels, whereas areas of hypoperfusion are of low attenuation and contain small vessels.

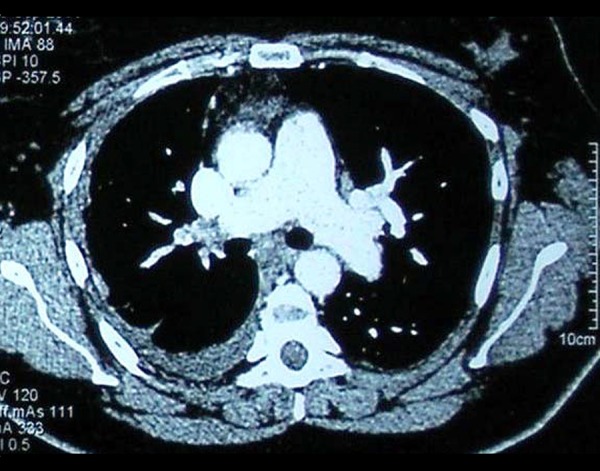

One month later, the patient presented with aggravation of dyspnea and marked limitation of functional capacity (NYHA III). Chest X-ray showed an enlarged heart with persistence of parenchymal infiltrates. Electrocardiogram showed right axis deviation. On the 6-minute walk test (6-MWT), the patient only managed to walk 190 m and presented with severe arterial oxygen desaturation of 77%. A transthoracic echocardiogram was then performed and revealed marked right atrial and ventricular enlargement, with normal left ventricular systolic and diastolic function. Doppler systolic pulmonary artery pressure was estimated at 67 mmHg. Computed tomography pulmonary angiography showed dilatation of the main pulmonary artery and filling defects corresponding to thrombus in the right main pulmonary artery down to the sub-segmental branches (Figure 2). The diagnosis of venous thromboembolism was established. Treatment with anticoagulants was initiated and adjusted to a target INR 2–3. Screening for thrombophilic disorders was negative. After 3 months of treatment, the patient did not show any improvement in symptoms and imaging. A new pulmonary angiography showed no signs of thrombi resolution. Right heart catheterization confirmed severe pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension, with high mean pulmonary arterial pressure at 43 mm Hg, while pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was within normal range (11 mm Hg), cardiac output was 4 liters/min, and pulmonary vascular resistance was elevated at 640 dyn/s/cm5. On the basis of clinical history, chest imaging, and hemodynamics, the patient was diagnosed with CTEPH. Ventilation-perfusion scan confirmed the diagnosis, demonstrating bilateral segmental perfusion defects with normal ventilation.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography pulmonary angiography showing dilatation of the main pulmonary artery and thrombus in the right main pulmonary artery.

The patient was referred to a specialized surgical center for operability assessment. She finally underwent a successful pulmonary thromboendarterectomy with uncomplicated recovery (Figure 3). Postoperative echocardiogram showed normal dimensions and contractility of the right ventricle. At the 3-month follow-up visit she was asymptomatic (NYHA I) and in the 6MWT she walked 630 m with no signs of oxygen desaturation.

Figure 3.

Material removed from the pulmonary vasculature by pulmonary endarterectomy.

Discussion

The basic workup of patients with dyspnea of unknown origin should include a chest X-ray and an electrocardiogram. These should be complemented by pulmonary function tests, exercise testing, and arterial blood gases. Echocardiography may be very useful in detecting the cause of cardiogenic dyspnea. It is virtually diagnostic in congestive heart failure and pericarditis and can be also used as the initial diagnostic tool when pulmonary hypertension is suspected.

CTEPH most often results from obstruction of the pulmonary vascular bed by nonresolving thromboemboli. The disease typically develops as a long-term complication of symptomatic pulmonary embolism, with an incidence of 1–5% within 2 years after the event [1,2]. Diagnostic delays are common because over one-third of patients do not report a history of pulmonary embolism. Moreover, since many of the symptoms (e.g., fatigue and dyspnea on exertion) are nonspecific, diagnosis is often missed. As a result, the disease is notoriously under-diagnosed and the true prevalence is still unclear. It is important to consider the diagnosis of CTEPH in all patients with unexplained pulmonary hypertension.

CTEPH patients are frequently characterized by numerous severe comorbidities [3]. A number of inherited and acquired coagulation abnormalities have been recognized as risk factors for the development of the disease. Certain chronic medical conditions (e.g., splenectomy, infected cardiac shunts, inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, and a genetic predisposition) have emerged as novel risk factors for the disease. Thyroid disease has been recognized as a risk factor for both CTEPH and idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Interestingly, treatment with levothyroxine increases von Willebrand factor levels and shortens in vitro platelet plug formation, possibly increasing thrombogenicity [4].

Chest imaging has become very valuable for diagnosing CTEPH and in monitoring the subsequent treatment [5]. Ventilation-perfusion scan is a useful diagnostic tool when screening for CTEPH. A normal perfusion scintigram practically rules out CTEPH. High-resolution CT scan of the lungs may present with a mosaic attenuation pattern. Mosaic pattern is characterized by patchy areas of decreased attenuation intermingled with areas of increased attenuation [6]. A classic example of this pattern is obliterative bronchiolitis. Subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis may also exhibit a mosaic attenuation pattern, combining both an interstitial and an obliterative small airway disease element. In the case of CTEPH, the characteristic mosaic attenuation of the parenchyma is due to patchy vascular hypoxemia; the darker areas correspond to the hypoperfused lung sections and contain vessels of significantly reduced caliber, while areas of pulmonary hyperperfusion are of high attenuation and are associated with large vessels. CT images obtained on expiration may help discriminate between these 2 conditions and in the case of small airways disease the differing attenuation is enhanced in expiratory scans.

If left untreated, the prognosis of CTEPH is poor and depends on the hemodynamic status at the time of diagnosis [1]. Pulmonary endarterectomy – the treatment of choice – is potentially curative and is associated with a reasonably low risk when performed in high-volume expert centers. Thus, early diagnosis and referral for operability assessment is crucial because CTEPH is one of the most treatable forms of pulmonary hypertension. Lifelong anticoagulation is also recommended for CTEPH patients to prevent the recurrent thromboembolic events. Advanced medical therapy with pulmonary vasodilators should be reserved for patients with inoperable disease and those with persistent or recurrent pulmonary hypertension after pulmonary endarterectomy.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of CTEPH may be difficult because symptoms are nonspecific and there is often no medical history of previous venous thromboembolism. Moreover, some of the signs on chest imaging may be subtle and mimic parenchymal lung disease. As a result, the disease is frequently under-recognized in clinical practice. Besides imaging, clinicians should keep in mind that certain clinical features may help discriminate between parenchymal and pulmonary vascular disease. Hypoxemia at rest, severe oxygen desaturation during exercise, and disproportionate decrease of diffusion capacity identify a higher probability of pulmonary vascular disease.

Abbreviations:

- CTEPH

chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Funding acknowledgment

This research received no funding.

References:

- 1.Hoeper MM, Mayer E, Simonneau G, Rubin LJ. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2006;113:2011–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.602565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pengo V, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al. Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension Study Group. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2257–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pepke-Zaba J, Delcroix M, Lang I, et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH): results from an international prospective registry. Circulation. 2011;124:1973–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.015008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lang IM, Klepetko W. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: an updated review. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2008;23:555–59. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328311f254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coulden R. State-of-the-art imaging techniques in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:577–83. doi: 10.1513/pats.200605-119LR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oikonomou A, Prassopoulos P. Mimics in chest disease: interstitial opacities. Insights Imaging. 2013;4:9–27. doi: 10.1007/s13244-012-0207-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]