Abstract

Background and purpose

Despite the view that only β2- as opposed to β1-adrenoceptors (βARs) couple to Gi, some data indicate that the β1AR-evoked inotropic response is also influenced by the inhibition of Gi. Therefore, we wanted to determine if Gi exerts tonic receptor-independent inhibition upon basal adenylyl cyclase (AC) activity in cardiomyocytes.

Experimental approach

We used the Gs-selective (R,R)- and the Gs- and Gi-activating (R,S)-fenoterol to selectively activate β2ARs (β1AR blockade present) in combination with Gi inactivation with pertussis toxin (PTX). We also determined the effect of PTX upon basal and forskolin-mediated responses. Contractility was measured ex vivo in left ventricular strips and cAMP accumulation was measured in isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes from adult Wistar rats.

Key results

PTX amplified both the (R,R)- and (R,S)-fenoterol-evoked maximal inotropic response and concentration-dependent increases in cAMP accumulation. The EC50 values of fenoterol matched published binding affinities. The PTX enhancement of the Gs-selective (R,R)-fenoterol-mediated responses suggests that Gi regulates AC activity independent of receptor coupling to Gi protein. Consistent with this hypothesis, forskolin-evoked cAMP accumulation was increased and inotropic responses to forskolin were potentiated by PTX treatment. In non-PTX-treated tissue, phosphodiesterase (PDE) 3 and 4 inhibition or removal of either constitutive muscarinic receptor activation of Gi with atropine or removal of constitutive adenosine receptor activation with CGS 15943 had no effect upon contractility. However, in PTX-treated tissue, PDE3 and 4 inhibition alone increased basal levels of cAMP and accordingly evoked a large inotropic response.

Conclusions and implications

Together, these data indicate that Gi exerts intrinsic receptor-independent inhibitory activity upon AC. We propose that PTX treatment shifts the balance of intrinsic Gi and Gs activity upon AC towards Gs, enhancing the effect of all cAMP-mediated inotropic agents.

Introduction

According to conventional understanding, G proteins transduce signals from activated G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) via second messengers to regulate numerous downstream signalling targets in the cell [1], [2]. G proteins are found on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane, composed of a guanine nucleotide binding α subunit (Gα) and a βγ dimer (Gβγ). Upon GPCR activation, GDP is exchanged for GTP on Gα, and both the GTP-liganded Gα and the Gβγ dimer regulate downstream targets. Five subfamilies of Gα have been classified, whereof Gαi/o is the only one able to inhibit adenylyl cyclase (AC) and the production of cAMP [3].

The predominant Gi-coupled receptor in the heart ventricle is the M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor [4]. Constitutive activity of this receptor exerts a mild, continuous inhibition of AC activity in normal rat ventricular cardiomyocyte membranes [5]–[7]. It is well established that the muscarinic system also antagonizes the inotropic responses mediated by β-adrenoceptors (βARs) [4], known as accentuated antagonism [8], [9].

The major stimulatory input in the myocardium comes from the β1- and β2ARs, whereby activation of these receptors leads to positive inotropic responses. In 1995, Xiao et al. made the intriguing observation that pertussis toxin (PTX), known to cause ADP-ribosylation of the Gαi subunit, uncoupling the GPCRs from Gi, enhanced β2AR- but not β1AR-mediated positive inotropic responses in isolated rat cardiomyocytes [10]. Together with subsequent studies [11]–[14], it has been widely accepted that in addition to Gs, the β2ARs also couple to Gi in native systems while the β1ARs do not.

However, we recently reported that the isoproterenol-mediated inotropic response in left ventricular muscle strips was potentiated by PTX [15]. When examined separately, both the β1- and β2AR-mediated inotropic response (βAR-IR) and cAMP accumulation in isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes were increased by PTX pre-treatment [16]. Additional data from rat [17], guinea-pig [18] and normal [19] as well as transgenic mice overexpressing the β2AR [20] indicate that β1AR-evoked contractility in the heart may also be regulated by Gi activity. Due to conflicting data on the role of Gi in β1AR signalling, we wanted to further investigate this issue.

It has previously been reported that AC activity evoked by forskolin and agonists at Gs-coupled receptors can be increased by prior PTX treatment in various cell types [21]–[24], as well as in cardiomyocytes [25] and sarcolemmal membranes from failing human myocardium [26]. However, these studies did not take into account the presence of constitutively active GPCRs which are known to regulate basal AC activity [7], [27]. It has been suggested by El-Armouche et al. [28], and shown by Rau et al. [17] through overexpression of Gαi2 as well as by Hussain et al. [15] by the use of phosphodiesterase (PDE) 3 and 4 inhibitors that Gi may have receptor-independent effects, whereby it directly inhibits AC activity. We examined the possibility that Gi may have receptor-independent effects in the absence of constitutively active receptors by using the unique properties exhibited by stereoisomers of the β2AR agonist fenoterol. (R,R)-fenoterol was first characterized by Woo et al. (2009) to selectively activate only the Gs pathway of the β2AR, whereas the other stereoisomers, including (R,S) used in this study, activate both the Gs and Gi pathways [29]. On this basis, (R,R)-fenoterol has been used as a tool to differentiate Gs- and Gi-coupling of the β2AR [30]. We further studied receptor-independent effects of Gi by using the direct AC activator forskolin, as well as the effects of PDE3 and 4 inhibition in the absence and presence of known antagonists or inverse agonists.

Our data indicate that in addition to the traditional role of Gi in receptor signalling, this G protein exerts a constant intrinsic inhibition upon AC independent of receptor activation.

Methods

Animal care

Experiments and animal care were conducted in accordance with the European Convention for the protection of vertebrate animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes (Council of Europe no. 123, Strasbourg 1985) and approved by the Norwegian Animal Research Authority. The animals were housed with a 12/12 h cycle at 21°C, food and water available ad libitum.

Measurement of contractility in left ventricular strips

Left ventricular strips (diameter ∼1.0 mm) were prepared from male Wistar rats (Taconic, Skensved, Denmark) weighing 300–350 g, mounted in 31°C organ baths containing physiological salt solution with 1.8 mM Ca2+, equilibrated and field-stimulated at 1 Hz [31], [32]. Contraction-relaxation cycles were recorded and analysed as previously described [33], [34]. Maximal development of force (dF/dt)max was measured and inotropic responses were expressed as increase in (dF/dt)max. Concentration-response curves were constructed by estimating centiles (EC10 to EC100) and calculating the corresponding means, and the horizontal positioning is expressed as –logEC50 values [33].

In a subset of rats, PTX was administered at a dose of 60 µg/kg i.p. as a single injection three days prior to isolation of the left ventricular muscle strips. Control rats were given a saline injection of equal volume. Data from animals treated with PTX were only included if carbachol inhibition of the βAR-IR was completely abolished (Fig. 1B). To confirm the effectiveness of PTX treatment in vivo (subset of 6 PTX-treated rats and 7 saline-treated rats) and in cardiomyocytes (see below), we measured the level of PTX-catalysed incorporation of [32P]ADP-ribose from [32P]NAD into available Gi as previously described [15].

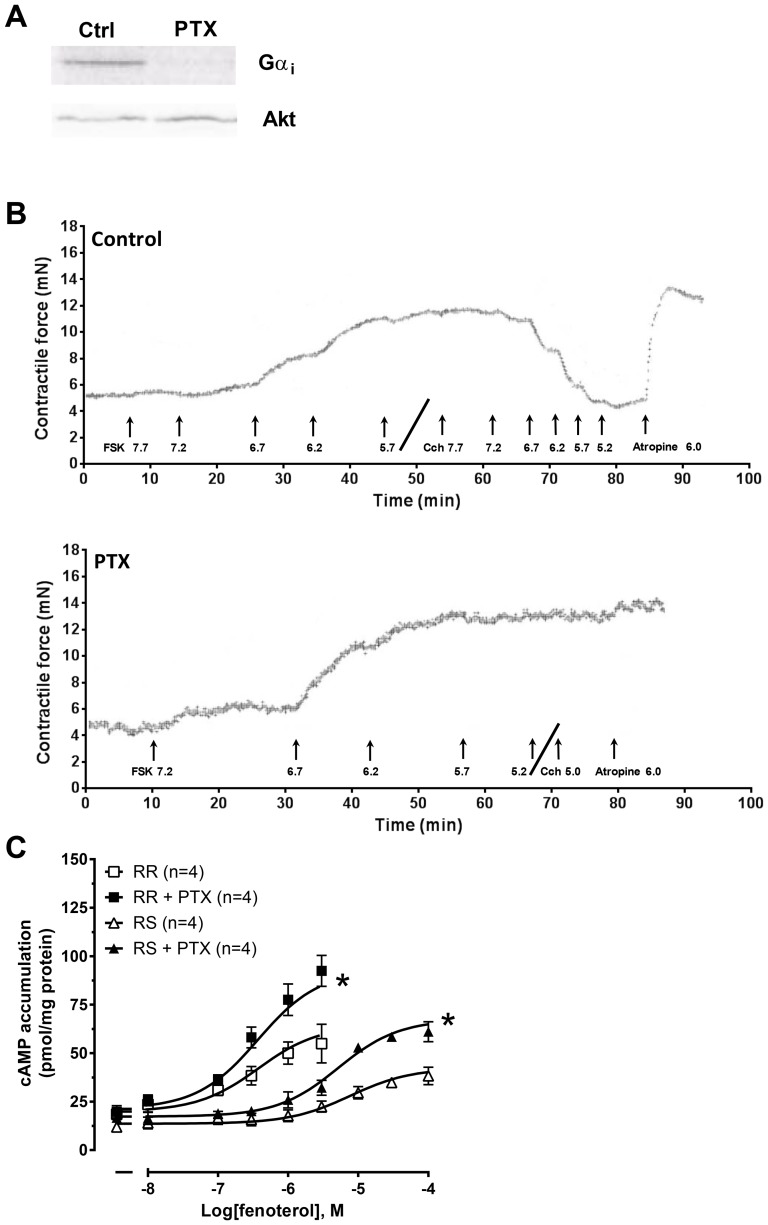

Figure 1. Effect of PTX upon (R,R)- and (R,S)-fenoterol-induced cAMP accumulation.

(A) Representative autoradiogram showing ADP-ribosylated Gαi protein levels in rat ventricle pre-treated with saline (control) or PTX. (B) Representative traces showing inotropic responses (mN) evoked by forskolin (FSK) and the subsequent effect of carbachol (Cch) and reversal of carbachol effects by atropine in left ventricular strips from rats pre-treated with saline (Control; top) or with PTX (bottom). Drug concentrations are given in -Log(M). (C) Concentration-response curves to (R,R)- and (R,S)-fenoterol-mediated cAMP accumulation in isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes in the presence of IBMX and the β1AR antagonist CGP20712 (300 nM) in control or after PTX pre-treatment. Data are mean ± SEM. Basal cAMP accumulation was (in pmol cAMP/mg protein): (R,R-series) control: 18.5±2.8; PTX: 19.7±3.2; (R,S-series) control 11.9±2.5; PTX 16.7±2.0. RR: (R,R)-fenoterol; RS: (R,S)-fenoterol; *P<0.05, paired t-test.

Measurement of cAMP accumulation in left ventricular cardiomyocytes

Adult left ventricular cardiomyocytes were isolated from excised male Wistar rat hearts by retrograde aortic perfusion with a nominally Ca2+-free JOKLIK-MEM solution and enzymatic digestion using collagenase (90 U/mL) as previously described [35]. Left ventricular cardiomyocytes were incubated for 20 h in the absence or presence of 1 µg/ml PTX (1.2 ml reaction volume). Experiments were conducted in the presence of the β1AR blocker CGP20712 (300 nM), the non-selective PDE inhibitor IBMX (0.5 mM) or PDE3 and 4 inhibitors cilostamide (1 µM) and rolipram (10 µM), as indicated. cAMP accumulation was measured by radioimmunoassay as previously described [36]. Protein was measured with the Coomassie Plus Protein Assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's protocol and cAMP accumulation was normalized to the amount of protein in each sample.

Measurement of (R,R)- and (R,S)-fenoterol-mediated inotropic responses and ability to activate adenylyl cyclase

To evaluate the β2AR-mediated inotropic response, Gs-selective (R,R)-fenoterol and Gs- and Gi-activating (R,S)-fenoterol were assessed by conducting a concentration-response experiment in the presence of a selective β1AR antagonist (300 nM CGP20712). Likewise, (R,R)- and (R,S)-mediated activation of AC was assessed by incubating cardiomyocytes for 10 min with increasing concentrations of either stereoisomer (0–100 µM) in the presence of 300 nM CGP20712. All cAMP accumulation experiments in this subset were conducted in the presence of the non-selective PDE inhibitor IBMX (0.5 mM).

Measurement of spontaneous intrinsic Gi inhibition upon adenylyl cyclase activity

Receptor-independent Gi activity was assessed through forskolin concentration-response curves (50 nM-10 µM) in left ventricular strips and isolated cardiomyocytes in the presence of the non-selective βAR antagonist timolol (1 µM) and α1-adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin (0.1 µM, ventricular strips only) with and without prior pre-treatment with PTX (as described above). To determine if spontaneous intrinsic activity of Gi regulated basal AC activity, the inotropic response in ventricular strips or cAMP accumulation in cardiomyocytes pre-treated with or without PTX was measured in the presence of both the PDE3 inhibitor cilostamide (1 µM) and PDE4 inhibitor rolipram (10 µM) in the presence of the non-selective βAR antagonist timolol (1 µM) and α1-adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin (0.1 µM, ventricular strips only).

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM from n animals. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant (One-way ANOVA and student's t-test). When appropriate, Bonferroni corrections were made to control for multiple comparisons.

Drugs and solutions

Prazosin hydrochloride, (-)isoprenaline hydrochloride, timolol maleate, atropine sulphate, lidocaine (2-diethylamino-N-[2,6-dimethylphenyl]-acetamide) hydrochloride, L-ascorbic acid and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). CGP20712 dihydrochloride, CGS 15943, cilostamide and rolipram were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). Forskolin was from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA). (R,R)- and (R,S)-fenoterol were a kind gift from J. Kozocas (SRI International, Menlo Park, CA, USA). Isoflurane (1-chloro-2,2,2-trifluoroethyl difluoromethyl ether; Forene) was from Abbot Scandinavia (Solna, Sweden). Pertussis toxin was from Merck chemicals (Nottingham, UK). [3H]cAMP was from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA, USA).

Results

Gi was essentially inactivated by pertussis toxin

The effectiveness of in vivo PTX treatment to inhibit Gi was assessed by measuring PTX-catalysed incorporation of [32P]ADP-ribose from [32P]NAD into available Gi in ventricular tissue. An ∼80-90% reduction was seen in the ability of subsequent PTX to ADP-ribosylate Gi in vitro in animals pre-treated with PTX compared to animals given saline injection (PTX-treated n = 6, saline-treated control n = 7, see Fig. 1A). It was not possible to distinguish the different Gαi isoforms in the autoradiogram due to the similarity in size (39-41 kDa). Importantly, in the PTX-treated group, data were included only if carbachol-induced inhibition of the βAR-IR was abolished (Fig. 1B). In the (R,R)- and (R,S)-fenoterol study, 83% of the PTX-treated rats were included in the study. In the forskolin and PDE inhibitor study 88% of the rats met the criteria and were included.

(R,R)- and (R,S)-fenoterol-stimulated cAMP accumulation was amplified after inactivation of Gi

(R,R)- and (R,S)-fenoterol-induced AC activation was assessed by measuring cAMP accumulation in isolated left ventricular cardiomyocytes in the presence of the non-selective PDE inhibitor IBMX. Surprisingly, PTX inactivation of Gi amplified the concentration-response curve to Gs-selective (R,R)-fenoterol (Fig. 1C). (R,R)-fenoterol selectively activated the β2AR at the concentration range 10 nM-3 µM, after which it overcame β1AR blockade by CGP20712 (not shown). Maximal cAMP accumulation evoked by 3 µM (R,R)-fenoterol was enhanced by 60% from 55 pmol/mg protein in control to 92 pmol/mg protein in the presence of PTX. The EC50 was not significantly different after PTX treatment (140±48 nM in control and 245±22 nM after PTX treatment) (Fig. 1C). These EC50 values were similar to the previously published binding affinity of (R,R)-fenoterol at the β2AR (350 ± 30 nM [37]).

As expected, (R,S)-fenoterol concentration-response curves were similarly modified by PTX treatment. Maximal cAMP accumulation evoked by the highest selective concentration of (R,S)-fenoterol for the β2AR (100 µM) was enhanced by 62% from 38 pmol/mg protein in control to 61 pmol/mg protein in the presence of PTX. The EC50 value was not significantly shifted from 3.5±0.5 µM in control to 5.0±0.9 µM after PTX treatment (Fig. 1C). Again, these EC50 values were similar to the published binding affinity of (R,S)-fenoterol of 3.7 ± 0.3 µM [37]. Together, these data demonstrate that PTX amplifies the amount of cAMP produced by both stereoisomers, despite dissimilar G protein-coupling profiles. This suggests that Gi exerts inhibitory activity upon AC downstream of receptor coupling to G protein.

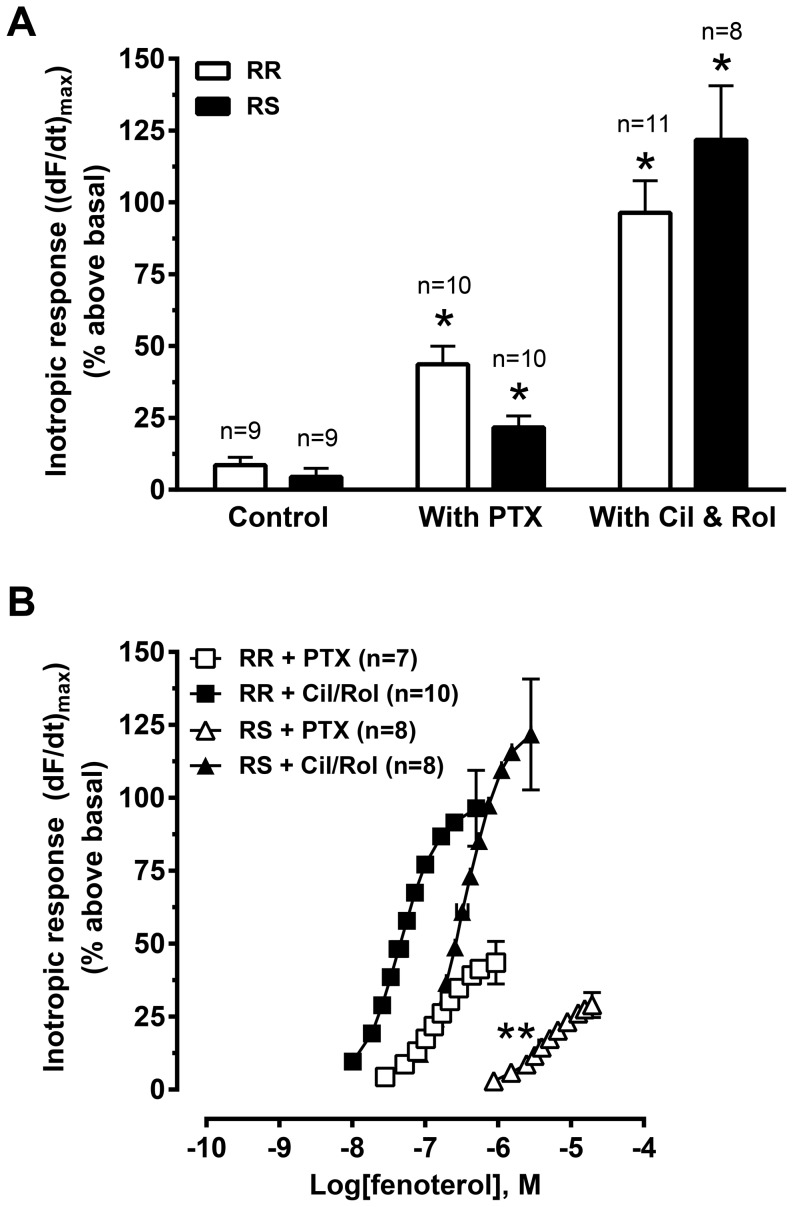

Maximal inotropic responses to both (R,R)- and (R,S)-fenoterol were amplified by Gi inactivation or PDE inhibition

In untreated (control) left ventricular muscle strips, the highest concentration given of (R,R)- and (R,S)-fenoterol elicited very small inotropic responses of 8.6±2.7% and 4.4±2.9% above basal, respectively (β1AR antagonist CGP20712 present; Fig. 2A). These values were slightly lower than inotropic responses obtained by β2AR stimulation by adrenaline in the presence of CGP20712 (∼11% above basal, data not shown).

Figure 2. Effect of PTX and PDE3 and 4 inhibition upon the inotropic response to (R,R)- and (R,S)-fenoterol stimulation.

Maximal inotropic response (A) and concentration-response curves (B) to (R,R)- or (R,S)-fenoterol in left ventricular strips from saline-treated rats (control) or PTX-treated rats or strips from saline-treated rats given PDE3 (cilostamide, Cil, 1 µM) and PDE4 (rolipram, Rol, 10 µM) inhibitors. All experiments were conducted in the presence of the β1AR blocker CGP20712 (300 nM). Inotropic responses are expressed as (dF/dt)max as percent above basal. Basal force was (in mN/mm2) (R,R) control: 4.3±0.4; (R,S) control: 4.2±0.6; (R,R) PTX: 3.5±0.5; (R,S) PTX: 3.5±0.4; (R,R) with Cil/Rol: 3.6±0.3; (R,S) with Cil/Rol: 3.9±0.4. Data are mean ± SEM. RR: (R,R)-fenoterol; RS: (R,S)-fenoterol; *P<0.05 vs. control, One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. **P<0.05 vs. (R,S) with Cil/Rol, One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons.

The inotropic responses evoked by maximal concentrations of both (R,R)- and (R,S)-fenoterol were significantly amplified by either PTX pre-treatment (44±6% or 22±4% above basal, respectively) or PDE3 and 4 inhibition (96±11% or 122±19% above basal, respectively) (Fig. 2A). These data are consistent with the cAMP accumulation data and reinforce the hypothesis that Gi may have downstream effects independent of receptor activation in a physiological model using intact, isometrically contracting ventricular muscle. Further, the data reflect that increased cAMP accumulation translates to an increased inotropic response.

In the absence of PTX treatment or PDE inhibition it was not possible to determine the EC50 values for either fenoterol isoform, due to the very small inotropic response. However, in the presence of PTX, the EC50 of (R,R)-fenoterol was 139±18 nM and of (R,S)-fenoterol 4.1±0.4 µM (Fig. 2B), very similar to that obtained from cAMP accumulation (Fig. 1C) and corresponding to the affinity values reported in the literature [37]. PDE3 and 4 inhibition shifted the concentration-response curves of both stereoisomers to lower concentrations (EC50: 58±16 nM for (R,R)- and 0.44±0.01 µM for (R,S)-fenoterol), indicating that both Gi and PDE3 and 4 regulate translation of the cAMP signal to a functional inotropic response.

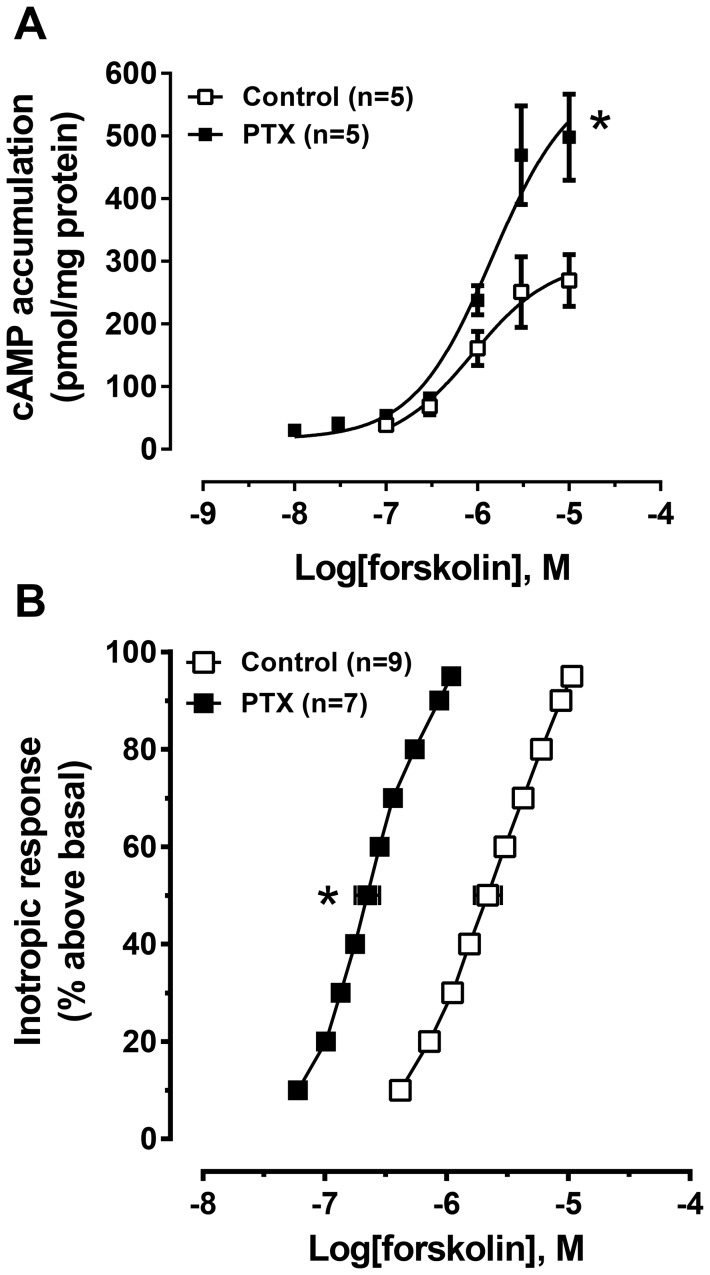

Forskolin responses are enhanced by inactivation of Gi

Forskolin, a direct activator of AC, was used to study receptor-independent effects of Gi on AC activity. To eliminate the influence of constitutive βAR activation of Gs (known to enhance forskolin responses), all experiments were conducted in the presence of the βAR inverse agonist timolol. cAMP accumulation in response to the maximum concentration of forskolin tested (10 µM; this concentration was sufficient to reach an asymptotic response) was enhanced by 85% by PTX treatment from 269±41 pmol/mg protein in control to 498±69 pmol/mg protein in the presence of PTX (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Effect of PTX upon the forskolin-evoked cAMP accumulation and inotropic response.

Concentration-response curves of forskolin-evoked cAMP accumulation in ventricular cardiomyocytes (A) and the inotropic response in ventricular strips (B) in the presence of the βAR blocker timolol (1 µM) in control or after PTX pre-treatment. Accumulation of cAMP was measured in the presence of IBMX, with basal cAMP accumulation (in pmol cAMP/mg protein): control: 38.8±5.3; PTX: 30.4±4.0. Basal force was (in mN/mm2): control: 4.05±0.56; PTX: 3.91±0.66. Data are mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, paired t-test (cAMP accumulation) or unpaired t-test (inotropic response).

In control left ventricular strips, forskolin (10 µM) evoked an inotropic response 120±15% above basal with an EC50 of 2.2 µM. After pre-treatment with PTX, the response to forskolin was significantly shifted to 10-fold lower concentrations, yielding an EC50 of 0.22 µM, with no change in the maximum inotropic response (103±20% above basal) at maximal tested concentrations (asymptote reached in range from 1–10 µM, Fig. 3B). Together, these data demonstrate that forskolin-stimulated AC activity and functional response in the absence of G protein-coupled receptor activation is modified by PTX treatment.

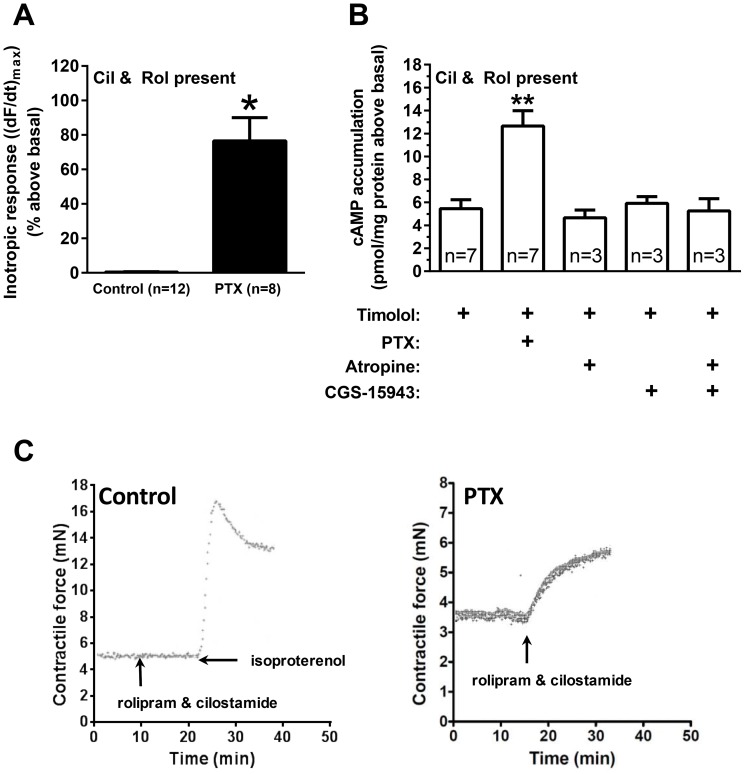

Simultaneous inactivation of PDE3 and PDE4 produced a robust cAMP-dependent inotropic response in myocardium only after prior inactivation of Gi

The following experiments were conducted in the presence of βAR blockade (timolol, 1 µM), to eliminate a possible effect of residual endogenous noradrenaline or constitutive activation of Gs through β1- or β2ARs. As previously reported [15], and replicated in this study, concomitant PDE3 and PDE4 inhibition (1 µM cilostamide and 10 µM rolipram) was sufficient to elicit a large inotropic response in ventricular strips (77±14% above basal) after PTX treatment (Fig. 4A,C right trace). However, simultaneous inhibition of PDE3 and 4 did not cause an inotropic effect in control hearts (0.42±0.19% above basal) (Fig. 4A,C left trace), indicating the absence of constitutively active Gs-coupled receptors. To test whether the effect of PTX occurred as a result of removing constitutive receptor activation of Gi, we evaluated the effect of two established Gi-coupled receptor systems in the heart. Neither the muscarinic inverse agonist atropine (1 µM) nor the non-selective adenosine inverse agonist CGS 15943 (1 µM), shown to be an inverse agonist at the Gi-coupled A1 adenosine receptor [38], alone or in combination evoked a change in contractile force above basal (Fig. S1).

Figure 4. Effect of PTX upon PDE3 and PDE4 inhibitor-induced cAMP accumulation and inotropic response.

(A) Effect of simultaneous inhibition of PDE3 (cilostamide, 1 µM) and PDE4 (rolipram, 10 µM) to evoke an inotropic response in left ventricular strips in control (open bars) and after PTX pre-treatment (solid bars) in the presence of timolol (1 µM). Basal force was (in mN/mm2): control: 3.3±0.4; PTX: 3.1±0.3. (B) Effect of PTX, βAR inverse agonist timolol (1 µM), non-selective muscarinic inverse agonist atropine (1 µM) or non-selective adenosine receptor inverse agonist CGS 15943 (1 µM) upon PDE3 (cilostamide, 1 µM) and PDE4 (rolipram, 10 µM)-evoked cAMP accumulation. Basal cAMP accumulation (in pmol/mg protein): timolol control: 4.8±0.6 (n = 7). (C) Representative traces showing inotropic responses (mN) evoked by inactivation of PDE3 and 4 simultaneously (1 µM cilostamide and 10 µM rolipram) in left ventricular strips of saline-treated control (left) and after PTX pre-treatment (right) in the presence of 1 µM timolol and 0.1 µM prazosin. Isoproterenol (100 µM displacing timolol) was given to demonstrate that an inotropic effect could be elicited through βARs. Data are mean ± SEM. * P<0.05 PTX vs. control, unpaired t-test; ** P<0.05 vs. timolol, One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons.

To investigate the relationship between cAMP and the inotropic response evoked by PDE3 and 4 inhibition after PTX treatment, cAMP accumulation was measured in isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes with or without PTX pre-treatment (Fig. 4B). Simultaneous inhibition of PDE3 and 4 increased cAMP levels in control cardiomyocytes (5.5±0.8 pmol/mg protein above basal). The level of cAMP accumulation evoked by simultaneous inhibition of PDE3 and 4 was significantly increased (∼2-fold) in cardiomyocytes pre-treated with PTX (to 12.7±1.3 pmol/mg protein above basal, Fig. 4B). The effect of PTX was not due to removal of constitutively active Gi-coupled receptors, since neither atropine (1 µM) nor CGS 15943 (1 µM) alone or in combination in the presence of simultaneous inhibition of PDE3 and 4 mimicked the effect of PTX treatment (Fig. 4B).

Discussion and Conclusions

Data from this study indicate that Gi tonically inhibits basal cAMP production, limiting functional responses. This inhibition appears to be independent of constitutive receptor activation of Gs and Gi upon AC. In support, (1) PTX treatment increased responses evoked by both the Gs-selective (R,R)- and the dually coupled (R,S)-fenoterol isoforms (Fig. 1C & 2A); this should not occur if the PTX effect was dependent upon receptor activity, since β2ARs stimulated by (R,R)-fenoterol have been shown to only activate Gs [29], [39]. (2) PTX treatment amplified forskolin-evoked cAMP accumulation and increased the potency of forskolin to evoke an inotropic response (Fig. 3A,B). Responses to forskolin, being a direct activator of AC [40], should not have been enhanced by inactivation of Gi; and (3) PTX treatment revealed intrinsic AC activity upon basal responses only after inhibition of PDE3 and 4, whereas inverse agonists at muscarinic receptors and adenosine receptors were without effect after PDE3 and 4 inhibition (Fig. 4A,B). This indicates that PDE3 and 4 inhibition, even in the presence of the βAR inverse agonist timolol, increased cAMP levels in PTX-treated tissue sufficiently to produce an inotropic response (Fig 4A,B,C). If constitutively active Gs-coupled receptors were mediating this effect, an inotropic response should have occurred after PDE3 and 4 inhibition alone in the absence of PTX treatment. Further, PDE3 and, at least in the rat ventricle, PDE4 activity (Fig. 4A,B; [41]) normally degrades low basal levels of cAMP, maintaining basal contractile force. These data highlight the necessity to remove the tonic inhibition of Gi upon AC prior to PDE inhibition to allow for the enhanced cAMP signal to be transduced into a functional response. We propose that PTX removes an intrinsic inhibition of Gi upon AC that is independent of Gi-coupled receptors. That neither the inverse agonist atropine (muscarinic M2) nor the non-selective adenosine receptor antagonist CGS 15943, alone or in combination, elicits effects similar to PTX (Fig. 4B, Fig. S1) indicates that PTX does not simply remove the effect of constitutively active Gi-coupled receptors.

Gi has a propensity to be in a spontaneously active conformation

There is a good basis indicating that Gi has receptor-independent activity. Lutz et al. [26] reported that in sarcolemmal membranes from failing human myocardium, Gi rapidly released GDP in a time- and temperature-dependent manner. When GDPβS was used in place of GDP to hold Gi in the inactive state, AC activity increased, suggesting relief of tonic inhibition. This effect was replicated by Mn2+ or high Mg2+, which prevent AC inhibition by Gi. The authors suggest that AC was inhibited by an empty but apparently active Gi (even in the absence of activating GTP), further highlighting the inhibitory potential of presumably inactivated Gi. [26].

Further, Piacentini et al. [42] reported that the synthetic GTP analogue Gpp(NH)p had no effect on basal AC activity. With the Gs∶Gi ratio ranging from ∼1∶10 to 1∶40 [43], [44], Gi would be the predominant G protein activated under these conditions. Since AC may already be maximally inhibited by spontaneously active Gi, it is expected that no additional effect of Gpp(NH)p is seen. However, when the stable GDP analogue GDPβS was used, basal AC activity increased, presumably through relief of tonic Gi inhibition. Under this condition, subsequent addition of Gpp(NH)p caused inhibition of AC, presumably through competition with GDPβS [42]. Thus, AC inhibition could be relieved by introduction of synthetic GDP-analogues and re-introduced by synthetic GTP-analogues, providing further support for receptor-independent Gi intrinsic activity.

Regulators of G protein signalling (RGS) are GTPase-accelerating proteins that promote rapid GTP hydrolysis and consequently inhibit signal transduction by inactivating G proteins and returning them to the GDP-bound heterotrimeric state. The effect of mutated, RGS-insensitive Gαi2 has been studied in cardiomyocytes derived from embryonic stem cells [45] and mice homozygous for the mutated, RGS-insensitive Gαi2 [46], providing a model for studying active Gi. Interestingly, basal inotropic and lusitropic responses were reduced by ∼10% in these mice compared to wildtype [46]. Also, Gs-dependent stimulation of beating rate by the β2-AR agonist procaterol was nearly abolished in foetal RGS-insensitive Gαi2-cardiomyoctes via a PTX-sensitive mechanism, further indicating that Gi exerts tonic inhibition on AC [45].

Chen-Goodspeed et al. [47] reported that human AC5 has high basal activity when expressed in Sf9 cell membranes, which was concentration-dependently inhibited by GTPγS-activated Gαi. AC6 basal activity was low, but could be inhibited by Gαi if previously activated with GTPγS-Gαs [47]. Thus, the two most common AC isoforms in the heart have the tendency to be spontaneously active, providing a substrate for opposition by intrinsic Gi activity.

In addition, data suggest that AGS proteins (activators of G protein signalling) may promote G protein activation by either directly acting as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor or by interfering with subunit association/dissociation/trafficking (both dependent and independent of nucleotide exchange) preventing heterotrimeric Gαβγ formation [48]. Together, these effects of AGS could potentially provide another plausible mechanism for mediation of receptor-independent Gi activity. Consistent with this hypothesis, Graham et al. [49] have shown that AGS1, which is selective for Gαi2 and Gαi3, inhibited cAMP accumulation evoked by constitutively active Gs or forskolin in 293T cells [49].

Does PTX treatment shift the balance of intrinsic Gi and Gs activity upon AC towards Gs?

Although the current data support the hypothesis that Gi exerts intrinsic receptor independent inhibition upon spontaneous AC activity, the mechanism is still unknown. Further, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that PTX treatment removes an unknown constitutively active Gi-coupled receptor. Despite these limitations, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the ratio of Gs∶Gi has important implications for the regulation of basal AC activity. As reported here, a minimum of 80-90% ADP-ribosylation of Gi was necessary to reveal functional effects of PTX treatment in our models. Under this scenario, the normal reported ratio of Gs∶Gi of ∼1∶10 to ∼1∶40 would be altered to ∼1∶1 to ∼1∶4, giving Gs more favourable terms to compete for binding to AC. This is consistent with Lutz et al. [26] who suggested that the AC system may be designed to operate from a predominantly off position (high intrinsic Gi activity), as both basal AC activity and Gs-coupled receptor activation would be enhanced by PTX inactivation of Gi. The mechanism that mediates these effects of PTX treatment remains to be determined.

It has recently been reported that Gs and Gi compete for an apparently limited pool of βγ [50]. Based on this finding, it is possible that as inactive GDP-bound Gi becomes ADP-ribosylated by PTX, Gi sequesters βγ from the total shared pool. Under this scenario, over time, there will be less βγ available for Gs, consequently increasing the probability of Gs to be in its active state (GTP-bound) in addition to the corresponding removal of intrinsically active Gi. A plausible hypothesis would be that Gi acts as a βγ sink. In support, overexpression of βARK-ct, a βγ scavenger, resulted in increased AC stimulation [51]. The net effect of PTX treatment would be to shift the balance from largely intrinsic inhibition to a greater intrinsic stimulation upon AC, thereby sensitising AC and enhancing/amplifying those systems known to activate AC (Fig. 5A).

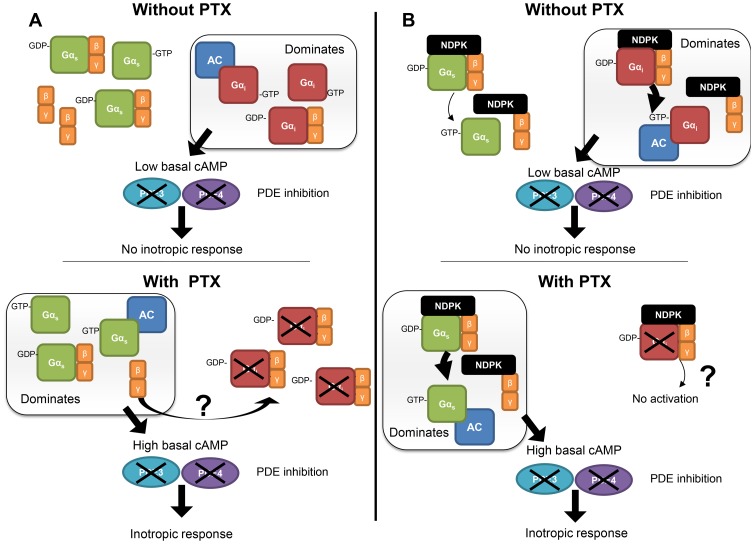

Figure 5. Possible mechanisms mediating the receptor-independent role of Gi in regulating basal AC activity.

(A) βγ-sink hypothesis: In the absence of PTX (top panel), spontaneously active Gi dominates, inhibiting basal AC activity and maintaining low cAMP levels which are incapable of eliciting an inotropic response even after inhibition of PDE3 and 4 (inhibition marked by X). After PTX treatment (bottom panel), Gi is not only inactivated (through ADP-ribosylation, marked by X) removing its spontaneous intrinsic inhibition upon AC, but also sequesters a large proportion of the shared Gβγ pool. This indirectly increases the proportion of receptor-independent spontaneously active Gs, leading to increased basal AC activity and cAMP that is normally readily degraded by PDE3 and 4. However, inhibition of PDE3 and 4 (marked by X) allows for translation of this cAMP increase into an inotropic response (see Fig. 4A). The net result is a shift from predominantly spontaneous Gi activity towards Gs activity, increasing basal AC activity and promoting activation of AC and positive inotropic effects of all inotropic agents working through increased cAMP signalling. (B) NDPK-hypothesis: In the absence of PTX (top panel), NDPK-activation of Gi dominates due to excess of Gi protein levels over Gs, resulting in low cAMP production readily degraded by PDE3 and 4. In the presence of PTX (bottom panel), Gi is inactivated by permanent ADP-ribosylation (marked by X). Thus, NDPK B could predominantly activate Gs, leading to both increased basal contractile force and cAMP accumulation that becomes revealed after PDE3 and 4 inhibition (marked by X).

Alternatively, based on the findings of Hippe et al. [52], PTX treatment may shift the ability of endogenous nucleoside diphosphate kinase B (NDPK B) to activate the Gi and Gs proteins. NDPK B is a G protein histidine kinase that regulates cAMP synthesis and cardiomyocyte contractility independent of GPCRs through the formation of an NDPK B-Gβγ complex that activates G protein through a phosphotransfer from NDPK B to His-266 in Gβ [52]. The phosphate is then transferred onto GDP, and the resultant GTP leads to receptor-independent G protein activation [52]–[54]. In the normal state, due to the excess of Gi over Gs, NDPK B would predominantly activate Gi and the stimulatory effects of Gs upon basal cAMP generation may be neutralized [52]. After PTX treatment, Gi is inactivated by permanent ADP-ribosylation. Thus, NDPK B would predominantly activate (potentiate) Gs activity leading to both increased basal contractile force and cAMP accumulation that becomes revealed after PDE3 and 4 inhibition (Fig. 5B). That we also observe enhancement of other cAMP signalling inotropes and forskolin is consistent with this hypothesis. To this end, experiments are currently underway to test both hypotheses, and should provide greater clarity of the mechanism behind intrinsic receptor-independent inhibitory activity of Gi upon AC.

Supporting Information

Effect of PTX, βAR inverse agonist timolol (1 µM), non-selective muscarinic inverse agonist atropine (1 µM) or non-selective adenosine receptor inverse agonist CGS-15943 (1 µM) upon PDE3 (cilostamide, 1 µM) and PDE4 (rolipram, 10 µM)-evoked inotropic response. Data are mean ± SEM. * P<0.05 vs. PTX, One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test adjustment for multiple comparisons.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Iwona Gutowska Schiander for excellent technical assistance and Joe Kozocas (SRI International, Menlo Park, CA, USA) for the kind gift of (R,R)- and (R,S)- fenoterol.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The present work was supported by The Norwegian Council on Cardiovascular Disease, The Research Council of Norway, South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority, Stiftelsen Kristian Gerhard Jebsen, Anders Jahre’s Foundation for the Promotion of Science, The Family Blix foundation, The Simon Fougner Hartmann foundation and grants at the University of Oslo. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Birnbaumer L (1990) G proteins in signal transduction. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 30: 675–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gilman AG (1987) G proteins: transducers of receptor-generated signals. Annu Rev Biochem 56: 615–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Taussig R, Gilman AG (1995) Mammalian membrane-bound adenylyl cyclases. J Biol Chem 270: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dhein S, van Koppen CJ, Brodde OE (2001) Muscarinic receptors in the mammalian heart. Pharmacol Res 44: 161–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ricny J, Gualtieri F, Tucek S (2002) Constitutive inhibitory action of muscarinic receptors on adenylyl cyclase in cardiac membranes and its stereospecific suppression by hyoscyamine. Physiol Res 51: 131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jakubik J, Bacakova L, El-Fakahany EE, Tucek S (1995) Constitutive activity of the M1-M4 subtypes of muscarinic receptors in transfected CHO cells and of muscarinic receptors in the heart cells revealed by negative antagonists. FEBS Lett 377: 275–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hanf R, Li Y, Szabo G, Fischmeister R (1993) Agonist-independent effects of muscarinic antagonists on Ca2+ and K+ currents in frog and rat cardiac cells. J Physiol 461: 743–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Levy MN (1971) Sympathetic-parasympathetic interactions in the heart. Circ Res 29: 437–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harvey RD, Belevych AE (2003) Muscarinic regulation of cardiac ion channels. Br J Pharmacol 139: 1074–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xiao RP, Ji X, Lakatta EG (1995) Functional coupling of the β2-adrenoceptor to a pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein in cardiac myocytes. Mol Pharmacol 47: 322–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuschel M, Zhou YY, Cheng H, Zhang SJ, Chen Y, et al. (1999) Gi protein-mediated functional compartmentalization of cardiac β2-adrenergic signaling. J Biol Chem 274: 22048–22052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xiao RP, Avdonin P, Zhou YY, Cheng H, Akhter SA, et al. (1999) Coupling of β2-adrenoceptor to Gi proteins and its physiological relevance in murine cardiac myocytes. Circ Res 84: 43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xiao RP (2001) β-adrenergic signaling in the heart: dual coupling of the β2-adrenergic receptor to Gs and Gi proteins. Sci STKE 2001: re15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xiao RP, Zhang SJ, Chakir K, Avdonin P, Zhu W, et al. (2003) Enhanced Gi signaling selectively negates β2-adrenergic receptor (AR) - but not β1-AR-mediated positive inotropic effect in myocytes from failing rat hearts. Circulation 108: 1633–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hussain RI, Aronsen JM, Afzal F, Sjaastad I, Osnes JB, et al. (2013) The functional activity of inhibitory G protein Gi is not increased in failing heart ventricle. J Mol Cell Cardiol 56: 129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melsom CB, Hussain RI, Ørstavik Ø, Aronsen JM, Sjaastad I, et al. (2014) Non-classical regulation of β1- and β2-adrenoceptor-mediated inotropic responses in rat heart ventricle by the G protein Gi. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol In press. doi: 10.1007/s00210-014-1036-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17. Rau T, Nose M, Remmers U, Weil J, Weissmuller A, et al. (2003) Overexpression of wild-type Gαi-2 suppresses β-adrenergic signaling in cardiac myocytes. FASEB J 17: 523–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ranu HK, Mak JC, Barnes PJ, Harding SE (2000) Gi-dependent suppression of β1-adrenoceptor effects in ventricular myocytes from NE-treated guinea pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H1807–H1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heubach JF, Rau T, Eschenhagen T, Ravens U, Kaumann AJ (2002) Physiological antagonism between ventricular β1-adrenoceptors and α1-adrenoceptors but no evidence for β2- and β3-adrenoceptor function in murine heart. Br J Pharmacol 136: 217–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gong H, Adamson DL, Ranu HK, Koch WJ, Heubach JF, et al. (2000) The effect of Gi-protein inactivation on basal, and β1- and β2AR-stimulated contraction of myocytes from transgenic mice overexpressing the β2-adrenoceptor. Br J Pharmacol 131: 594–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hsia JA, Moss J, Hewlett EL, Vaughan M (1984) Requirement for both choleragen and pertussis toxin to obtain maximal activation of adenylate cyclase in cultured cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 119: 1068–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Malaisse WJ, Svoboda M, Dufrane SP, Malaisse-Lagae F, Christophe J (1984) Effect of Bordetella pertussis toxin on ADP-ribosylation of membrane proteins, adenylate cyclase activity and insulin release in rat pancreatic islets. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 124: 190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Griffin MT, Law PY, Loh HH (1985) Involvement of both inhibitory and stimulatory guanine nucleotide binding proteins in the expression of chronic opiate regulation of adenylate cyclase activity in NG108-15 cells. J Neurochem 45: 1585–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Davenport CW, Heindel JJ (1987) Tonic inhibition of adenylate cyclase in cultured hamster Sertoli cells. J Androl 8: 314–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reithmann C, Werdan K (1995) Chronic muscarinic cholinoceptor stimulation increases adenylyl cyclase responsiveness in rat cardiomyocytes by a decrease in the level of inhibitory G-protein α-subunits. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 351: 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lutz S, Baltus D, Jakobs KH, Niroomand F (2002) Spontaneous release of GDP from Gi proteins and inhibition of adenylyl cyclase in cardiac sarcolemmal membranes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 365: 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Milligan G (2003) Constitutive activity and inverse agonists of G protein-coupled receptors: a current perspective. Mol Pharmacol 64: 1271–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. El-Armouche A, Zolk O, Rau T, Eschenhagen T (2003) Inhibitory G-proteins and their role in desensitization of the adenylyl cyclase pathway in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 60: 478–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Woo AY, Wang TB, Zeng X, Zhu W, Abernethy DR, et al. (2009) Stereochemistry of an agonist determines coupling preference of β2-adrenoceptor to different G proteins in cardiomyocytes. Mol Pharmacol 75: 158–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chakir K, Depry C, Dimaano VL, Zhu WZ, Vanderheyden M, et al. (2011) Gαs-biased β2-adrenergic receptor signaling from restoring synchronous contraction in the failing heart. Sci Transl Med 3: 100ra88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Skomedal T, Osnes JB, Øye I (1982) Differences between α-adrenergic and β-adrenergic inotropic effects in rat heart papillary muscles. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 50: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Skomedal T, Borthne K, Aass H, Geiran O, Osnes JB (1997) Comparison between α1 adrenoceptor-mediated and β-adrenoceptor-mediated inotropic components elicited by norepinephrine in failing human ventricular muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 280: 721–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sjaastad I, Schiander I, Sjetnan A, Qvigstad E, Bøkenes J, et al. (2003) Increased contribution of α1- vs. β-adrenoceptor-mediated inotropic response in rats with congestive heart failure. Acta Physiol Scand 177: 449–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qvigstad E, Brattelid T, Sjaastad I, Andressen KW, Krobert KA, et al. (2005) Appearance of a ventricular 5-HT4 receptor-mediated inotropic response to serotonin in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 65: 869–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Andersen GØ, Skomedal T, Enger M, Fidjeland A, Brattelid T, et al. (2004) α1-AR-mediated activation of NKCC in rat cardiomyocytes involves ERK-dependent phosphorylation of the cotransporter. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H1354–H1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Skomedal T, Grynne B, Osnes JB, Sjetnan AE, Øye I (1980) A radioimmunoassay for cyclic AMP (cAMP) obtained by acetylation of both unlabeled and labeled (3H-cAMP) ligand, or of unlabeled ligand only. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 46: 200–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jozwiak K, Khalid C, Tanga MJ, Berzetei-Gurske I, Jimenez L, et al. (2007) Comparative molecular field analysis of the binding of the stereoisomers of fenoterol and fenoterol derivatives to the β2 adrenergic receptor. J Med Chem 50: 2903–2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shryock JC, Ozeck MJ, Belardinelli L (1998) Inverse agonists and neutral antagonists of recombinant human A1 adenosine receptors stably expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Pharmacol 53: 886–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Woo AY, Jozwiak K, Toll L, Tanga MJ, Kozocas JA, et al. (2014) Tyrosine 308 is necessary for ligand-directed Gs-biased signaling of β2-adrenoceptor. J Biol Chem 289: 19351–19363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dessauer CW, Chen-Goodspeed M, Chen J (2002) Mechanism of Gαi-mediated inhibition of type V adenylyl cyclase. J Biol Chem 277: 28823–28829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Levy FO (2013) Cardiac PDEs and crosstalk between cAMP and cGMP signalling pathways in the regulation of contractility. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 386: 665–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Piacentini L, Mura R, Jakobs KH, Niroomand F (1996) Stable GDP analog-induced inactivation of Gi proteins promotes cardiac adenylyl cyclase inhibition by guanosine 5'-(βγ-imino)triphosphate and muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. Biochim Biophys Acta 1282: 11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Scherer NM, Toro MJ, Entman ML, Birnbaumer L (1987) G-protein distribution in canine cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum and sarcolemma: comparison to rabbit skeletal muscle membranes and to brain and erythrocyte G-proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys 259: 431–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Eschenhagen T (1993) G proteins and the heart. Cell Biol Int 17: 723–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fu Y, Huang X, Zhong H, Mortensen RM, D'Alecy LG, et al. (2006) Endogenous RGS proteins and Gα subtypes differentially control muscarinic and adenosine-mediated chronotropic effects. Circ Res 98: 659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Waterson RE, Thompson CG, Mabe NW, Kaur K, Talbot JN, et al. (2011) Gαi2-mediated protection from ischaemic injury is modulated by endogenous RGS proteins in the mouse heart. Cardiovasc Res 91: 45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen-Goodspeed M, Lukan AN, Dessauer CW (2005) Modeling of Gαs and Gαi regulation of human type V and VI adenylyl cyclase. J Biol Chem 280: 1808–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Blumer JB, Smrcka AV, Lanier SM (2007) Mechanistic pathways and biological roles for receptor-independent activators of G-protein signaling. Pharmacol Ther 113: 488–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Graham TE, Qiao Z, Dorin RI (2004) Dexras1 inhibits adenylyl cyclase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 316: 307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hippe HJ, Ludde M, Schnoes K, Novakovic A, Lutz S, et al. (2013) Competition for Gβγ dimers mediates a specific cross-talk between stimulatory and inhibitory G protein α subunits of the adenylyl cyclase in cardiomyocytes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 386: 459–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Koch WJ, Rockman HA, Samama P, Hamilton RA, Bond RA, et al. (1995) Cardiac function in mice overexpressing the β-adrenergic receptor kinase or a βARK inhibitor. Science 268: 1350–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hippe HJ, Lutz S, Cuello F, Knorr K, Vogt A, et al. (2003) Activation of heterotrimeric G proteins by a high energy phosphate transfer via nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK) B and Gβ subunits. Specific activation of Gsα by an NDPK B.Gβγ complex in H10 cells. J Biol Chem 278: 7227–7233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hippe HJ, Luedde M, Lutz S, Koehler H, Eschenhagen T, et al. (2007) Regulation of cardiac cAMP synthesis and contractility by nucleoside diphosphate kinase B/G protein βγ dimer complexes. Circ Res 100: 1191–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hippe HJ, Wolf NM, Abu-Taha I, Mehringer R, Just S, et al. (2009) The interaction of nucleoside diphosphate kinase B with Gβγ dimers controls heterotrimeric G protein function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 16269–16274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Effect of PTX, βAR inverse agonist timolol (1 µM), non-selective muscarinic inverse agonist atropine (1 µM) or non-selective adenosine receptor inverse agonist CGS-15943 (1 µM) upon PDE3 (cilostamide, 1 µM) and PDE4 (rolipram, 10 µM)-evoked inotropic response. Data are mean ± SEM. * P<0.05 vs. PTX, One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test adjustment for multiple comparisons.

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.