Abstract

This review summarizes our understanding of economic factors during the obesity epidemic and dispels some widely held, but incorrect, beliefs: Rising obesity rates coincided with increases in leisure time (rather than increased work hours), increased fruit and vegetable availability (rather than a decline of healthier foods), and increased exercise uptake. As a share of disposable income, Americans now have the cheapest food available in history, which fueled the obesity epidemic. Weight gain was surprisingly similar across sociodemographic groups or geographic areas, rather than specific to some groups (at every point in time, however, there are clear disparities). It suggests that if we want to understand the role of the environment in the obesity epidemic, we need to understand changes over time affecting all groups, not differences between subgroups at a given time.

Although economic and technological changes in the environment drove the obesity epidemic, the evidence for effective economic policies to prevent obesity remains limited. Taxes on foods with low nutritional value could nudge behavior towards healthier diets, as could subsidies/discounts for healthier foods. However, even a large price change for healthy foods could only close a part of the gap between dietary guidelines and actual food consumption. Political support has been lacking for even moderate price interventions in the US and this may continue until the role of environment factors is accepted more widely. As opinion leaders, clinicians play an important role to shape the understanding of the causes of obesity.

Keywords: Economic environment, Food, Diet, Physical Activity, Obesity, Body weight, Price, Policy

Introduction

Obesity, a condition of an excessively high proportion of body fat, is associated with elevated risks of cancers of the breast, colon and rectum, endometrium, esophagus, gallbladder, kidney, pancreas, thyroid, and possibly other cancer types.1 Obesity is also a risk factor for coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, stroke, and other chronic illnesses. In the US, an estimated 34,000 new cases of cancer among men (4%) and 50,500 among women (7%) in 2007 were attributable to obesity, although there is great uncertainty in those estimates.2

Researchers have long recognized that the changes in dietary and physical activity patterns underlying the obesity epidemic were caused by changes in the economic, social and physical environments that people face.3,4 Reflecting this view, the American Cancer Society has added recommendations for community action to its guidelines.5 Recommended community actions to prevent cancer include increasing access to healthy foods, decreasing availability of foods of low nutritional value, and developing environments conducive to physically active recreation and transportation.5

While there is no disagreement about the broad goals of preventing obesity, improving diet quality, and reducing sedentary lifestyles, finding effective policy levers remains a challenging task. This includes consideration of political acceptability or such policies will either not be adopted or will be undermined quickly. Denmark imposed a tax on foods high in saturated fats in 2011, only to repeal it in 2012; a planned tax on foods with added sugars was cancelled at the same time.6 In the US, there have been numerous legislative proposals to tax soft drinks or junk food, but so far none have passed.

Various types of environments possibly play a role on the obesity epidemic, and we may classify them into 3 general categories: economic and policy environment (e.g., tax, subsidy, direct pricing, serving size regulation, nutrition labeling, etc.), social environment (e.g., family, school, community, workplace, social norms, mass media, food marketing, nutrition education, etc.), and physical environment (e.g., urban design, sidewalk, parks, food outlets, exercise facilities, transportation, etc.). We focus on the relationship between economic/policy environment and obesity in this review, with brief discussions of other factors. This is only due to the scope of a review article; addressing all areas and their interaction would require a book-length monograph.

Many factors have been suggested as causes: snack food, automobile, television, fast food, computer use, vending machine, suburban housing development, portion size, female labor force participation, poverty, affluence, supermarket, and even the absence of supermarkets (“food desert”). Putting a multitude of isolated research results and data points into a coherent picture is a necessary task to assess whether proposed solutions are promising or are likely to lead down a blind alley. As it turns out, some widely held beliefs about societal trends are unambiguously false; others require some qualifications.

This review uses the traditional narrative format, rather than a systematic review or meta-analysis. A systematic review or meta-analysis works best to compile information comprehensively and without bias when there is a well-defined research question addressed by a substantial number of comparable studies. A systematic review becomes less useful for summarizing studies across very different fields of investigation and if the heterogeneity of studies requires judgment about their contribution.

A general theme throughout this review is that the obesity epidemic was driven by changes in the environment, not by differences in the environment across population groups. However, comparable data across several years, let alone several decades, are rare, so research has primarily analyzed environmental differences existing at a point in time. While this identifies differences between sociodemographic groups, cross-sectional comparisons are not necessarily informative about the causes of obesity epidemic that occurred over time, nor will they suggest effective policies to change factors behind common trends.

What Can We Learn From Data on Social Trends?

The prevalence of obesity has increased rapidly over the last decades. This increase in prevalence became widely known in the medical literature by the late 1990s.7,8 While it is often thought that the obesity epidemic started in the 1980s or 1990s, increases in body mass index (BMI) have been going on for a much longer time. American children have been gaining excess weight slowly and persistently at least since the 1950s, but possibly earlier.9 Data prior to the 1950s are sparse, but regionally limited and socially selective samples of military cadets before nationally representative surveys became available suggest increasing BMI for young men from the 1920s on.9 For men 40-49, BMI may have increased since about 1900, without evidence of acceleration in recent decades.10

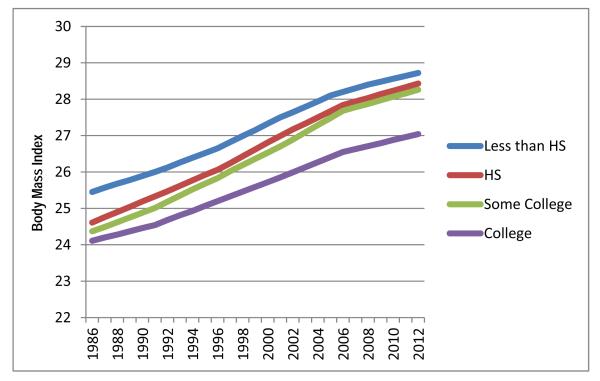

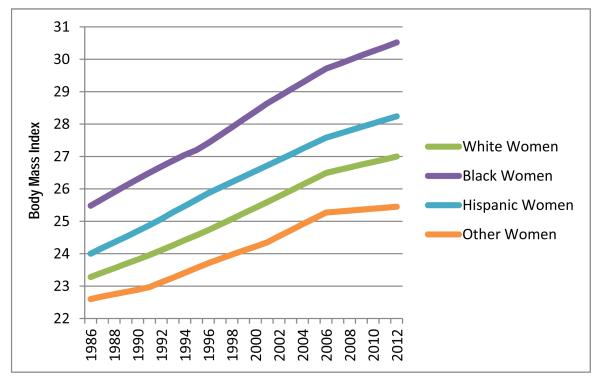

It is often believed that the obesity epidemic reflects increasing social disparities or that the largest weight gains are concentrated in groups identifiable by race/ethnicity, income, education, or geography. If true, focusing on cross-sectional environmental differences between subpopulations could reveal environmental factors behind the obesity epidemic and suggest policy levers. This belief, however, is incorrect: Changes in BMI appear to be very similar across all population subgroups, even though the average BMI (and the prevalence of obesity) at any point is highest among groups with lower income and education and among some ethnic minorities. Figures 1a, 1b, 1c show BMI trends in the US by educational level and by race/ethnicity (results are similar when stratifying by other variables). The striking finding is the similarity of increases in BMI across groups. This makes it very unlikely that the obesity epidemic is caused by environmental changes that affect certain sociodemographic subgroups disproportionally. Instead, we interpret those trends as similar environmental changes for all sociodemographic groups.

Figures 1. Increase in Body Mass Index Over Time.

a, b, c Source: Author’s calculations based on Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, smoothed trends adjusted for 2010 demographics.)

The trends of BMI gain by sociodemographic characteristics are never perfectly parallel, of course. For example, the gap between people without high school education and some college closes a bit over time while the gap between people with some college education and those with a college degree widens. The gap between Black and White men has recently narrowed, while the gap for women has widened. Women and non-Hispanic Blacks gained weight faster than other groups.11

Nevertheless, temporal changes in the gaps between groups are secondary to the increase that all groups experience over time. It suggests that if we want to understand the role of the environment in the obesity epidemic, we need to understand a bit more on the changes over time affecting all groups rather than differences between subgroups at a given time. Similarly, fighting obesity nationwide needs universal interventions. Targeting selected sociodemographic groups might help reduce disparities, a laudable goal itself, but it would seem very unlikely to address the much bigger effects that have occurred over time.

This is not a novel insight empirically or conceptually. Empirically, analyses using NHANES from over 30 years found no increase in socioeconomic differentials in self-reported dietary attributes and biomarkers (including objective measures of BMI), but rather that differentials in most outcomes persisted over three decades.12 No change in the socio-economic differences of BMI was observed in Finland between 1978 and 2002.13 Conceptually, the etiology of conditions needs to address two distinct issues: the determinants of individual cases, and the determinants of incidence rate, as explained in a now famous paper by Geoffrey Rose.14 Clinicians are concerned with the causes for individual cases, but the number of cases is driven by the cause of the incidence rate. If the cause of the obesity epidemic is an increasingly obesogenic environment to which all groups are exposed, then a cross-sectional comparison will fail to capture the major driver behind increasing obesity rates. Instead, they identify markers of susceptibility, which in this case are sociodemographic differences in obesity rates at a point in time. Focusing on more vulnerable populations and reducing disparities are important goals in their own right, but they alone are not likely to be sufficient in reversing the obesity trends in the whole population.

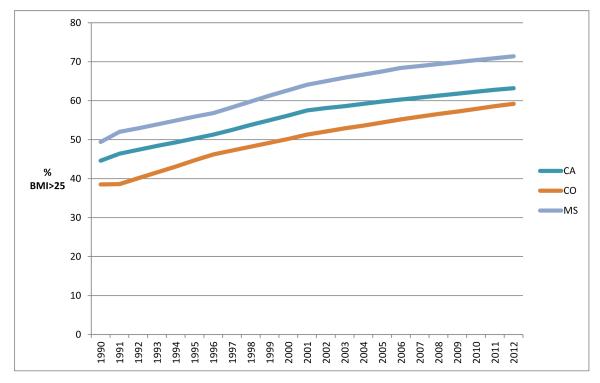

What about geographic differences? There is a famous set of maps by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which illustrates the changing obesity prevalence by stage since 1985.15 However, some interpretations of these maps seem to confuse cross-sectional differences with changes over time. A new diet book about the “Colorado diet” includes the following description by the publisher:16 “Americans are getting fatter. A third of them are now obese–not just a few pounds overweight, but heavy enough to put their health in jeopardy. But, one state bucks the trend. Colorado is the leanest state in the nation, but not because of something in the air or the water.”

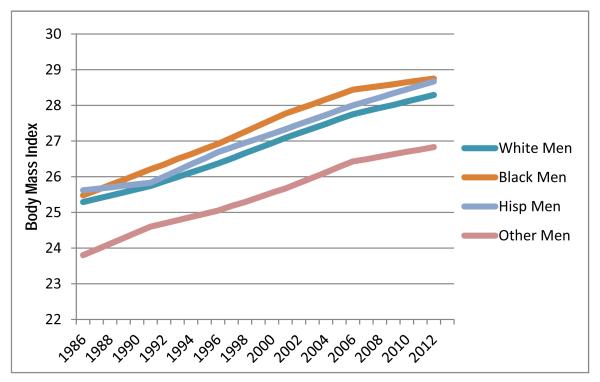

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of BMI over 25 (i.e. overweight or obese) over time for Colorado (the state with the lowest average BMI or overweight or obesity rates), California, and Mississippi (the state with usually the highest rates). The overweight/obesity rates in Colorado rates do lag behind those in Mississippi, but we see no evidence of any “bucking the trend.” Instead, we interpret the data as an indication that Colorado has exactly the same experiences as Mississippi, just delayed by a bit more than a decade.

Figure 2. Prevalence of Overweight Over Time.

Source: Author’s calculations based on Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, smoothed trends adjusted for 2010 demographics.)

Conventional wisdom is an unreliable guide, so we need to take a careful look at the (relatively limited) data about social trends. The American Cancer Society’s guidelines echo common beliefs by claiming, for example, that “longer workdays… reduce the amount of time available for the preparation of meals” or “reduced leisure time ….contribute[s] to reduced levels of physical activity.”5

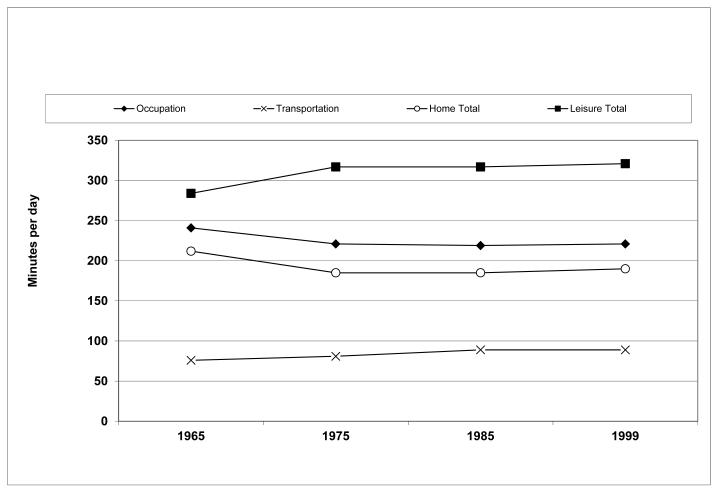

However, one of the most consistent trends over the past half century has been a reduction in work hours, and an increase in leisure or free time and time spent in transportation.17,18 Leisure time has seen a large increase since 1965 (Figure 3). Occupation and productive activities at home (cooking, cleaning, repairing things, childcare) have diminished to make room for this. Thus, increasing weight has been accompanied by increased rather than decreased leisure/free time. Women spend more time in the labor force than before, but that is more than offset by declines in home production (e.g. cooking, cleaning, child care). The increase in free time and in transportation time also occurs in all population groups, even if there are differences at any point in time (in particular, men have always had more free time than women when household activities are factored in). This trend is brought by the changes in the economic and technological environment that reduces the need for work (which includes unpaid work at home).

Figure 3. Trends in Time Use Among US Adults.

(Source: 1965-1985: Robinson and Godbey; 1999: our calculation using FISCT 1999)

Figure 3 shows trends by linking different surveys that were conducted prior to 2000. In 2003, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) started an annual time use survey in 2003 and BLS publications confirm that the trends shown in Figure 3 have continued: In 2012, people spent 10 minutes less on (paid) work and related activities and 24 minutes less on (nonpaid) household activities and caring for children than in 2003. In contrast, people watched 15 minutes more TV, participated 4 more minutes in active sports/exercise, and slept or napped 10 minutes more in 2012 than in 2003.19

Another persistent myth is that Americans are exercising less. In reality, there has been a consistent increase in active sports or walking/hiking, reflected both in time use data, expenditures on active sports activities (gyms, sports clubs, equipment) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Surveys (BRFSS). BRFSS has showed a consistent decline in sedentary behavior: The percentage of people reporting at least 30 minutes of moderate activity on 5 or more days or 20 minutes of vigorous activity on 3 or more days per week increased from 46% in 2001 to 51% in 2009 (median state rate in the BRFSS). Self-report is known to exaggerate actual levels of activity (just as self-reported height and weight understates actual BMI), but it nevertheless indicates an increase in activity levels. The American Time Use Survey showed an increase of 4 minutes between the first year conducted (2003) and the latest (2012).19 Obviously, only a rather small part of the increased free time went into active leisure. Leisure time physical activity is only one component of total physical activity and how total physical activity has changed depends also on labor force and home production as well as transportation patterns.

Transportation is part of everyday life, not only in order to get to work, but also to run (or drive) errands, go out for dinner, or see friends. It could also be a key factor of changes in physical activity because small shifts in travel modes noticeably alter energy expenditure. Adults spend over 10 hours a week traveling, more than ever before, about equally splitting into transportation related to occupation (work commute), home activities (child care/shopping/personal care), and leisure time activities. Transportation time, together with leisure time, has increased at the expense of occupation and household activities.

These social trends themselves do not identify the linkage between the environment and obesity, but they indicate that several popular ideas about causes of the obesity epidemic are misleading. Weight gain has not been concentrated among specific sociodemographic groups, nor in particular geographic areas, so we have to look for environmental changes that are similar for all groups rather than look for existing environmental differences. The obesity epidemic occurred as leisure time increased, and therefore it is not led by reduced leisure time. And even though many and possibly most Americans fall short of physical activity recommendations, leisure time physical activity has increased rather than fallen during the obesity epidemic. To understand the obesity epidemic, rather than asking a question like “Why are people in Colorado thinner than people in Mississippi,?” we need to ask a question like “Why are people in Colorado gaining weight at the same rates as people in Mississippi?”

Economic Environment

It has been argued that the obesity epidemic is primarily a story of economics and technology and we largely agree with this view.20,21 Food systems in developed countries have been extraordinarily successful in assuring a plentiful food supply. The major issue in developed and medium-income countries (like Brazil) is obesity, rather than a shortage of food (except for those at the lowest income level), which was experienced even in countries like the US or in Western Europe less than a century ago. The problem of food shortage has shaped agricultural policies. Worldwide, hunger and malnutrition remain very real and affect around 870 million people, primarily in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.22

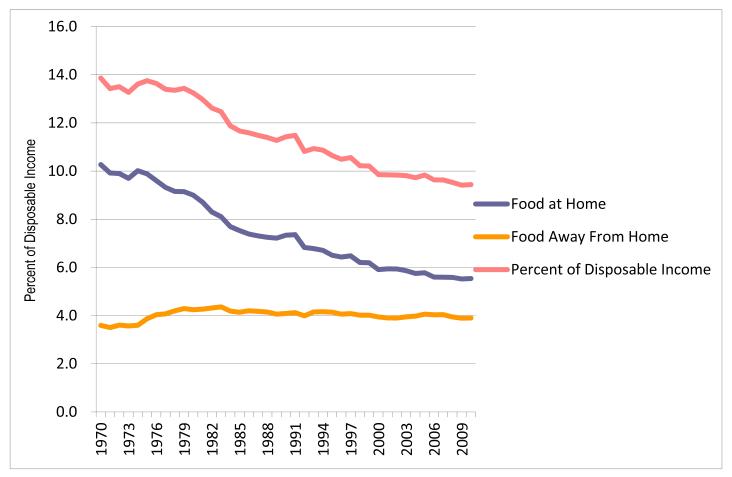

Americans now have the cheapest food in history when measured as a fraction of disposable income. In the 1930s, Americans spent a quarter of their disposable income on food, dropping to one fifth in the 1950. Figure 4 shows the trend since 1970 and the share is now under a tenth of disposable income (Figure 4). In contrast, about a quarter of income is spent on food in medium-income countries like Mexico and Turkey (comparable to the share of food expenditure in the 1930s in the US). In places like Kenya or Pakistan, food expenditures consume on average almost half of the disposable income. The share varies across income groups, of course, and is higher than the average for lower income groups in every country. For the bottom income quintile in the US, food expenditures account for about a third of disposable income.

Figure 4. Food Expenditure as Percent of Disposable Income.

(Source: USDA-ERS, Prices and Expenditures, Table 7)

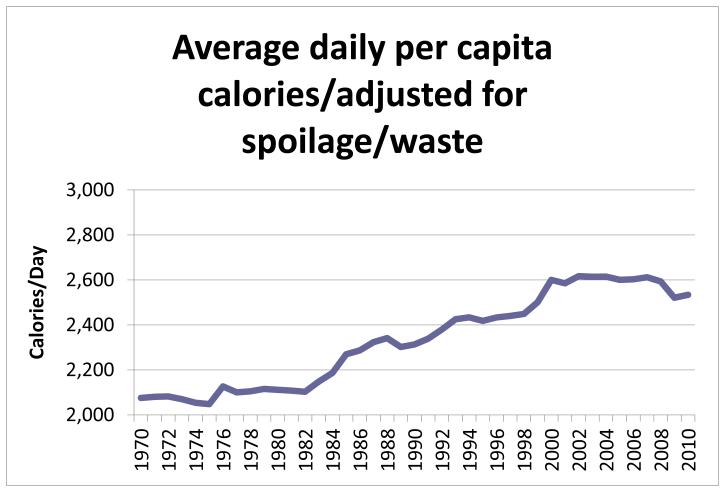

Along with the real decrease in food cost, per capita food availability has increased. Consequently, this smaller share of disposable income now buys many more calories (Figure 5). The decline of food expenditures relative to income becomes even more dramatic when one factors in “quality” improvements,21 including greater convenience, reduce time costs for preparation, variety, and ubiquitous availability of food. These changes have value to consumers. Married women outside the labor force spent more than two hours per day preparing meals and cleaning up in the 1960s; 30 years later, they spent half that amount of time. Greater convenience, reduced time costs of obtaining meals, and increased accessibility lead to increased food consumption and possible has been the major cause behind weight gain since 1980.20

Figure 5. Total Calories — Adjusted for Waste.

(Source: USDA-ERS, Food Availability (per capita) Data System)

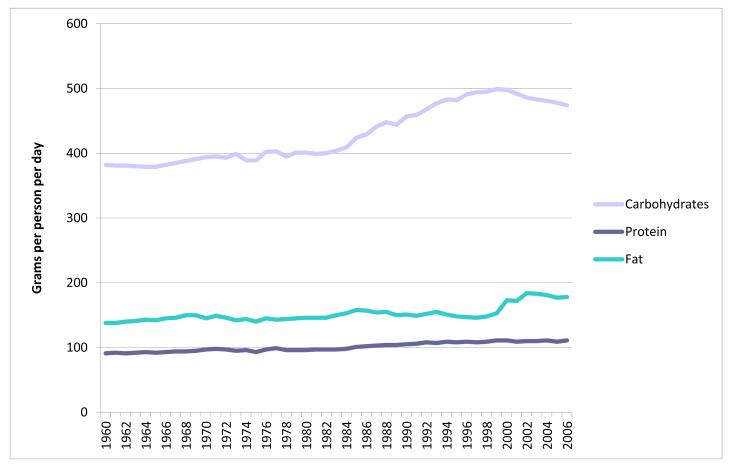

Regarding macronutrients, the most noticeable change was an increase in carbohydrates, especially during the 1980s (Figure 6). Although high fructose corn syrup became popular as a low cost sweetener, it accounts only for a small part of the carbohydrate increase, so there is no obvious economic/technological reason that drove this development. There could be reasons in the social environment, possibly the combination of widespread interest in a low fat diet to which the food industry responded with reduced fat products. After 2000, carbohydrates declined while fat availability increased. Again, this might be a reflection of changes in the social environment driving demand, possibly the popularity of Atkins-like diets, rather than changes in the economic or policy environment affecting food supply. The demand effects of fad diets can be very large even though there is no reliable way of tracking them. The most commonly quoted numbers come from a consulting firm and suggest that at the peak of the Atkins-diet boom (late 2003 to early 2004), about 9% of all adults were following the diet and 17% have tried it. By the end of 2004, the number of people following the diet dropped to 2% (which still would be about 5 million American adults) and Atkins Nutritionals filed for bankruptcy a year later.23,24

Figure 6. Change in Macronutrients During the Obesity Epidemic.

(Source: USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, data update Feb.1, 2012.)

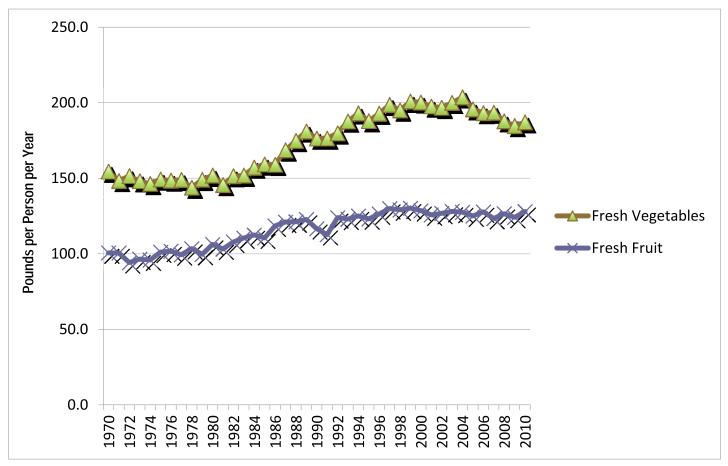

The general tenor in public debates is that diet quality has deteriorated by a shift towards “junk food,” that cross-sectional disparities in obesity rates are caused by lack of access to “healthy food,” or that “healthy food” has become too expensive. Americans eat less fruits and vegetables than recommended by dietary guidelines; current production would be insufficient to achieve guideline consumption; individuals who eat more fruits/vegetables tend to be thinner. All of this is true. However, preventing obesity is not about eating more food, regardless of how many nutrients it provides, but consuming less energy or expending more. Regardless of the coming and going of nutritional fads, fruit/vegetable consumption has increased, not fallen, while obesity rates increased. Figure 7 shows the increase in availability for fresh produce over the last 40 years, a 27% increase in fresh fruit and a 21% increase in fresh vegetables per capita from 1970 to 2010. Total produce (which includes frozen and canned) has increased similarly, by around 80 pounds per capita. Foods that increased above average include broccoli, cauliflower, tomatoes, onions, apples, bananas, and grapes. In contrast, there was a net decline in per capita potato lconsumption. Admittedly, analysis on aggregate data has limitations on potential confounding issue (a classic example of the Simpson’s paradox). However, individual-level food consumption surveillance data are much narrower in time coverage. Nevertheless, data from the BRFSS suggested the frequency of fruit and vegetable consumption remained relatively stable between 1994 and 2005 while small increases were found for men aged 18 to 24 years and for women who were aged 25 to 34 years, non-Hispanic African American, and nonsmokers.25

Figure 7. Availability of Fresh Fruit and Vegetables Has Increased (pounds per capita).

(Source: USDA/Economic Research Service. Data last updated Feb. 1, 2012.)

As most Americans still fall short of recommended intake of fruits and vegetables, additional increases could be desirable to improve diet quality, but it is much more questionable that this would reduce obesity. In experimental settings and weight loss programs, low energy dense foods are promising, so fruits and vegetables can be effective as they substitute for more energy dense foods.26,27 However, it is questionable that the substitution has taken place at the population level, because the widening of waistlines coincided with increased fruit and vegetable consumption. In fact, coinciding with the increase in fruit and vegetable intake over time, the percentage of adult sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) drinkers increased from 58% to 63%, per capita consumption of SSB increased by 46 kcal per day, and daily SSB consumption among drinkers increased by 6 oz from 1988 to 2004.28 Thus, the idea that increasing fruit and vegetables availability in isolation leads to less energy intake is probably just wishful thinking.29

There are many theories about obesity and even contradictory hypotheses can be correct if they apply to different situations — just as public health and clinical perspectives differ. Eventually, it is an empirical question what the primary effects are and whether there are special situations where other considerations apply. We want to contrast the two most prominent hypotheses and their empirical evidence:

The first hypothesis is the basic economic argument that people consume more when their income increases or prices fall.20,21,30 Moreover, the “full” price is not just money, but also the time and effort it takes to obtain it. The full price of a home-prepared meal includes not just ingredients, but travel to the store, time preparing the food, time cleaning up. As food becomes relatively cheaper, there is constant access, and people become wealthier (both occurred in the past 50 years), the simple economic theory predicts that obesity rates should increase.21 The basic economic effect is strengthened by natural biological and psychological factors i.e. that increased portion size, food visibility, salience of food cue stimulate the desire to eat more.31 Moreover, people are often unaware of the amount of food they have eaten or of the environmental influences on their eating, so the reducing economic constraints on consumption can have a larger effect than just a price effect for intentional purchases. This seems very consistent with the longitudinal data and the public health concept that the causes of the changing prevalence of obesity are environmental changes that affect all groups.

There is a set of related alternative hypotheses that recently received much media attention as a possible cause of the obesity epidemic that make essentially the opposite argument, in particular that low income or high food prices or limited access to food outlets (“food deserts”) cause obesity. Adam Drewnowski proposed what arguably is the most compelling hypothesis among that set.32,33 He argues that the lowest-cost options to obtain a given amount of energy from food is through an energy-dense diet composed of refined grains, added sugars, and fats. The high energy density and palatability of sweets and fats increase energy intake. Lower income people tend to spend less on food overall and specifically less on lower energy dense (but more costly) foods like fruits and vegetables. The high energy density and palatability of sweets and fat drive up caloric intake. A related argument was in a clinical case report of an obese 7-year old girl by Bill Dietz.34 Dietz argued that the increased fat content of food eaten during times when the family had insufficient income to buy a healthy diet was the primary reason, but offered as an alternative hypothesis that obesity is an adaptive response to episodic food insufficiency. Using the terminology introduced to public health by Geoffrey Rose,14 these ideas seem to be more consistent with the concept of “causes of cases,” i.e. they may identify individual risk factors in cross-sectional data, than with “causes of incidence.” According to a recent review of different variants of the “scarcity” hypothesis, its major shortcomings lie in the inconsistency with time trends in US as well as international data.35 More disconcertingly, even its relevance for cross-sectional differences is limited because it only seems to apply to women (obesity rates vary more than two-fold by income level) but not for men (there is no income gradient, only an education gradient).36

The economic and technological environment also affects physical activity. Digging trenches by hand or cutting wood without power tools may expend much energy, but is not a desirable use of time. Increased mechanization and a resulting shift of jobs from agriculture to industry and eventually to services meant that instead of being paid for expending energy as part of a job, people now have to budget time for leisure time exercise.

While the economic environment had a large impact on utilitarian physical activity historically (e.g. activity for work, transportation, rather than leisure), there are two reasons why it is a less plausible story for the obesity epidemic. First, the largest changes due to motorization precede the obesity epidemic by decades and are primarily a phenomenon of the first half of the 20th century. US macronutrients data (the same source as for Figure 6) even show a decline primarily in carbohydrates from 1910 to about 1960, indicating that people actually consumed fewer calories, presumably because energy needs for daily activities declined. Second, occupation-related changes in physical activity should have affected mainly people in the labor force, but weight changes have been similar across groups regardless of employment status and the obesity epidemic affected children as well. Increased mechanization/motorization is not limited to changes in the labor market, but also affects household tasks like gardening, cleaning, or washing. But the timing of the diffusion of those labor-saving devices for household production also seems to precede the obesity epidemic. Electric service was almost universal by 1950 and the diffusion of household washing machines peaked in 1980 (and has dropped since).

A more recent change in technology that seems to fit timing better has been electronics, which led to an explosion in the supply and variety of passive entertainment and communication options, and sedentary behavior and screening time have been well documented to contribute to very low energy expenditure, obesity, and many other illnesses.37-39 Video Cassette Recorders (VCR), already an obsolete entertainment technology by now, diffused rapidly during the 1980s. VCRs had been adopted by the majority of households within a decade after the first VHS-format player was introduced in 1976. A rapid flow of new entertainment options competes with more active recreation activities. Electronic communication may even make jobs more sedentary than before as personal computer (in the 1980s) and later the internet (in the 1990s) became available. The consequences of these changes on physical activity are too subtle to be measurable, even if they could contribute to energy imbalance.

Built Environment

The economic and built environment are inextricably linked. Some general trends for built environments are well known and could have led to higher obesity rates. This includes urbanization, increased personalized transportation, and some features of “urban sprawl,” characterized by developments with lower population density than traditional cities, and separation of residential, shopping, and business areas. This type of development increases dependence upon automobiles for transportation and increases commuting distances, a trend observed in Europe just as much as in the US.

Plausible pathways exist through which built environments can affect health.40 However, the evidence is almost exclusively cross-sectional, which may or may not be relevant to explaining changes over time, and results are much more ambiguous and fragile than typically presented in the media. The research literature tends to fall into two different areas with surprising little overlap.

The first area focuses on urban design and initial studies found correlations between built environments and obesity and chronic conditions related to lack of physical activity.41,42 Since then, much more research has been conducted and several systematic reviews have examined the empirical evidence for the influence of the built or physical environment on the risk of obesity.43-47 However, study results are rather mixed and at times contradictory, leading reviews to conclude that “few consistent findings emerged,” that “findings were inconsistent and mixed across studies,”46 and that “the great heterogeneity across studies limits what can be learned from this body of evidence.”45

While evidence for a causal relationship between characteristics of the built environment and obesity is weak, findings for an association between the built environment and physical activity seem more consistent.48,49 Access to a mix of local recreational and non-recreational destinations (e.g., cafes, grocery stores, food stores, other retail services, and schools) is positively associated with transportation and leisure walking.48,50 For children, the most supported correlates of physical activity were walkability, traffic speed/volume, access/proximity to recreation facilities, land-use mix, and residential density; for adolescents, the most supported correlates were land-use mix and residential density;51 for adults, there is consistent evidence that better access to relevant neighborhood destinations (e.g., local stores, services, transit stops) can be conducive to utilitarian walking.52 There is some, although weaker, evidence suggests that availability of sidewalks and well-connected streets can facilitate utilitarian walking.52 Built environments that incorporate diverse housing types, mixed land use, housing density, compact development patterns, and accessible open space were associated with increased levels of physical activity, primarily walking.47 Associations with other forms of physical activity were less common and there was no impact on body weight.47

The second area of research centers focused on food availability, in particular the concept of a “food desert.” The US Department of Agriculture originally defined an urban “food desert” as a census tract where a significant number of residents live more than ½ mile or 1 mile away from a supermarket. Conventional wisdom holds that obesity rates are higher in such “food deserts” because people shop for groceries at small stores with limited or no selection of attractive healthy foods. Indeed, densely populated low income neighborhoods tend to have fewer large supermarkets. This argument was cited in the American Cancer Society’s guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention.5

The evidence may be weaker than commonly thought. Recent research could not confirm the claims that distance to supermarkets predicts obesity or even diet quality.53-56 Across numerous studies, distance to various types of food stores showed no relationship to dietary outcomes.56,56 The only study that evaluated the impact of opening a new supermarket in a “food desert” found that this did not lead to changes in reported fruit and vegetable intake or body mass index.57 Proximity to the nearest supermarket had no impact on obesity rates in the Seattle Obesity Study, which also examined shopping patterns and found that only 1 in 7 respondents reported shopping at the nearest supermarket and the other 6 instead did their grocery shopping further away.53

Equating the absence of a supermarket with an unhealthy food environment or a “food desert” is a unique US concept. Elsewhere, the growth of supermarkets has been deplored as reducing access to fruit and vegetables and even increasing prices for fresh produce.58 Supermarkets are very efficient at supplying a wide range of brands (think about cereal or soft drink aisles). In the UK and Australia, “fruiterers and greengrocers” have been the traditional source for fresh produce, not supermarkets.

Policy Approaches

Obesity is a consequence of long-term changes in the environment that cannot easily be reversed, although policies can certainly be used to “nudge” people towards healthier (and maybe even smaller) diets and more active lifestyles, including suggestions for soft drink or fast food taxes or subsidies for healthier foods or sports activities. There are also structural policies that do not influence health-related behaviors directly, but are more upstream in that they alter characteristics of the food and built environment over the long run. Example would be production-liked payments to farms that led to overproduction of staples in many countries, mortgage tax deductions in the US that have contributed to urban sprawl, or transportation policies favoring individualized motorized transport almost everywhere.

Taxes and subsidies are obvious policy instruments to incentivize consumers to improve their food and beverage consumption patterns and related health outcomes. There has been a long history of price manipulation in food markets, but not with the goal of preventing obesity or improving diet quality. Traditional goals of agricultural and food policy have been self-sufficiency, national security, viability of rural communities, reducing hunger and food insecurity, occasionally preservation and heritage (an important theme in France, for example). In more recent years, biodiversity, sustainability, environmental protection, food safety, balanced diets have received some consideration, but policy change is slow. Every food system is multifunctional, which means it also creates outputs that are not traded on markets, whether they are positive (cultural heritage, food security) or negative (antibiotic resistance, water pollution), and this multifunctionality has shaped food policy.59

Health groups worldwide have started to call for agricultural policies to adopt dietary goals, such as intake of saturated fats, sugar, salt, or under-consumption of vitamins or minerals. The argument is that primary food production and processing stages can influence nutritional quality and the structural determinants of food choices, including availability and price. The US is not unusual in that the policies in traditional farm bills have become dysfunctional given today’s challenges, nor in the slow change to adapt to new challenges. In Europe, production-based payments to farmers led to overproduction of staples as well, which then were dumped on the world market or occasionally even on the home market. Germany held annual holiday surplus sales of “Christmas butter” until the 1980s. Even though the European Commission in 2010 expressed an intention to include dietary goals in the common agricultural policy (CAP), the only non-traditional goal in the 2013 political agreement on new directions for the common agricultural policy has been to promote sustainability and combat climate change.60

In the US, the traditional policy approach was to spur production of commodity crops and the production-led agricultural policy was very successful to produce cheap calories.61 Since 1974, the USDA implemented a federal policy that incentivized commodity farmers to produce as much as possible, which resulted in a massive overproduction of corns and soybeans. Not surprisingly their relative price plunged and government intervened by heavily subsidizing large-scale farmers to compensate for their loss, thus creating another round of overproduction and forming a vicious cycle. Consumers at the end of the food supply chain respond to the price drop for corn flour, corn syrup, soybean oil, etc. and increase their consumption noticeably. From 1970 to 2007, among American’s grain intake, corn calories led the way with a 191% increase, and added sugar intake from corn sweetener rose by 359%. Due to the extreme complexity of the US agricultural system which evolved over decades and promoted obesity, simply limiting or eliminating farm subsidies to commodity farmers is unlikely to be the quick fix.61 The 2014 US farm bill made several steps into that direction, such as ending more 15 years of crop programs that made payments to producers based on historical production.62 Although the farm bill represents around $1 trillion over the next decade, 80% of the funds are for nutrition programs, primarily supplemental nutrition assistance (previously known as food stamps).

Whether altering the costs of nutritionally less desirable foods versus “healthier” choices through pricing policies closer to the consumer end could change food consumption patterns and overall diet enough to significantly reduce population weight outcomes remains unclear. For some subgroups, price changes are more likely to have a measurable effect on weight outcomes, including youth, low socioeconomic populations, and those at risk for becoming obese.63 In areas with lower fruit and vegetable prices, children consume more fruit and vegetables and gain less excess weight over time.64-66 Generally, however, demand for most types of food is inelastic, which means that even large price changes only result in a moderate demand response.67 The exception might be SSB where demand may change proportional to price changes, but even in this case, large taxes would be needed to have noticeable effects on body weight.63,68

Attempts to raise taxes on nutritionally less desirable foods, in SSB, have so far been unsuccessful in the US. The most recent law was passed in Mexico in 2013. Although primarily a measure to reduce the budget deficit, curbing unhealthy consumption habits was an explicit goal and the soft drink and food industries lobbied heavily in an attempt to defeat the plan. Since January 2014, soft drinks are taxed one peso per liter (about 8 cents) and there is an 8 percent tax on high calorie snack foods, including chocolates, sweets, ice cream, chips, puddings, and processed foods based on cereals.

Denmark imposed a tax on saturated fat in 2011, but that tax was rescinded the following year and a planned sugar tax was shelved at the same time.6 In 2011, Hungary introduced a tax on foods with high fat, sugar and salt content, whereas France introduced a ‘soda tax’ on SSB in 2012.69 No data are available on the effects of any of these policies yet.

Subsidizing healthier foods can increase the purchase and consumption of subsidized products, but inelastic demand means that changes in consumption will be smaller than price changes. A typical magnitude is from an intervention in South Africa where a 25% rebate on healthy foods led to an 8.5 % increase in the share of purchases of fruits and vegetables and a drop of 7.2% in the share of nutritionally less desirable foods.70

Based on empirical evidence and expert opinion, three recommendations have been supported by a broad group of health economists in the obesity area:71 (1) Incorporate health impact assessment to review agricultural polices so that they do not have a deleterious impact on population rates of obesity; (2) Implement a caloric sweetened beverage tax, and (3) Examine how to implement fruit and vegetable subsidies targeted at children and low income households. It is unrealistic to expect those measures to be a quick and easy fix for the obesity epidemic, but at least they appear to be in the right direction.

From a policy perspective, it is less obvious what economic instruments can do to promote physical activity directly and clear policy recommendations cannot be made at this time.71 Most physical activity takes place in natural environments, not gyms, and does not need to be a purposeful exercise session. Walking for leisure is the most common activity people engage in and transportation walking also accounts for a substantial share of physical activity.71 Policy levers to affect physical activity are therefore more likely to be found in the built environment, rather than by providing subsidies for gyms. This is different from the food policies where taxes and subsidies can more directly influence consumption.

The design of built environments provides an opportunity, but also a challenge. Once in place, built environments can provide a sustainable strategy for physical activity. Neighborhoods are especially important as the majority of physical activity, including walking, occurs there. But if they are poorly designed and discourage physical activity, remodeling or rebuilding is extremely costly and time consuming.

Discussion

Changes in dietary and physical activity patterns are driven by changes in the environment and by the incentives that people face. Many factors have been suggested as causes of the “obesity epidemic.” Putting a multitude of isolated data points into a coherent picture is a challenging task, but necessary to assess whether proposed solutions are promising or likely to lead down a blind alley. Conventional wisdom tends to be a very unreliable guide and as the data in this review show, some widely held beliefs about obesity and environments have little evidence in their favor — and some are contradicted by the data.

The obesity epidemic is a phenomenon over time. BMI has increased similarly in different sociodemographic groups, suggesting that the same environmental changes impact all social groups. There are disparities in obesity prevalence across groups at every point in time, but reducing health disparities is different from addressing the obesity epidemic.

The obesity epidemic has been fueled by historically low food prices relative to income. Americans are spending a smaller share of their income (or corresponding amount of effort) on food than any other society in history or anywhere else in the world, yet get more for it. Although the prices for prepared foods (more commonly high in refined carbohydrates or fat) have become particularly cheap, fruits and vegetables are now more available than ever and consumption has increased rather than declined during the obesity epidemic. There appears to be reasonable evidence that weight outcomes are responsive to food and beverage prices, although (politically feasible) food taxes and subsidies may not do much more than “nudge” people towards healthier (and maybe even smaller) diets.

The built environment has received much attention, but strong evidence only emerges for physical activity. The association with obesity or even just diet behavior is tenuous, probably because the link between neighborhood stores and shopping has been weakened in a mobile society. A limitation is that the evidence on the effects of built environments on obesity, diet, and physical activity comes primarily from cross-sectional data. The contribution of long-run changes in built environments, including the increased dependence on cars, on obesity may very well be different than the current (minor or non-existent) association in cross-sectional data.

Looking at time trends for which there are data, what jumps out are changes in food availability, in particular the increase in caloric sweeteners and carbohydrates. Average daily discretionary calories from salty snacks, cookies, candy, and soft drinks now exceed discretionary calories recommended in the Dietary Guidelines for energy balance and essential nutrients and the ratio of consumed to recommended discretionary calories is a significant predictor of BMI in the population.72

It is true that people still do not eat as much fruit and vegetables as dietary guidelines recommend. But if people had access to more produce, cheaper produce, or just eat more of it, would they eat less candy and be thinner? Probably not. More variety means more eating, not less; outside clinical settings, there is limited evidence that people substitute; and as far as obesity is concerned, juice is not that different from soda in terms of energy content. Separately, some research also indicates that fruit juice has a less beneficial effect on health compared to whole fruit and might even increase the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes.73-75 The 2009 report by the Institute of Medicine on food deserts also points to total consumption: “greater fruit and vegetable consumption alone will not reduce weight without the qualification to moderate energy intake.”76 Unaffordability of healthy food may not be the problem as far as obesity is concerned - it is excess availability and affordability of all types of food. Effective policy interventions must address the need to reduce calories in the diet and replace calorie-dense foods with fruits and vegetables, rather than just add fruits and vegetables to the diet.

Many policy interventions are focusing on “positive” approaches or messages, such as increasing fruit and vegetable consumption and increasing physical activity. But an emphasis on reducing discretionary calorie consumption, particularly sugar-sweetened sodas and salted snacks, may be a promising lever to reduce overweight and obesity. The majority of adults exceed the amount of recommended discretionary calories for energy balance. While increasing fruit and vegetable consumption may be a laudable goal for other health reasons, it is unlikely to be an effective tool for obesity prevention.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the research was provided by the National Institutes of Health and RAND Internal Funds.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Authors have no other financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, et al. Diabetes and Cancer: A Consensus Report. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2010;60:207–221. doi: 10.3322/caac.20078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Risk/obesity.

- 3.Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Reed GW, Peters JC. Obesity and the Environment: Where Do We Go From Here? Science. 2003;299(5608):853–855. doi: 10.1126/science.1079857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine . Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, D.C.: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kushi LH, Doyle C, McCullough M, et al. 2010 Nutrition and Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee American Cancer Society Guidelines on Nutrition and Physical Activity for Cancer Prevention: Reducing the Risk of Cancer with Healthy Food Choices and Physical Activity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):30–67. doi: 10.3322/caac.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stafford N. Denmark cancels “fat tax” and shelves “sugar tax” because of threat of job losses. BMJ. 2012;(345):e7889. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson CL. Overweight and obesity in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1960-1994. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22(1):39–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Bowman BA, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The spread of the obesity epidemic in the United States, 1991-1998. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1519–1522. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komlos J, Breitfelder A, Sunder M. The transition to post-industrial BMI values among US children. Am J Hum Biol. 2009;21(2):151–160. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa D, Steckel R. Long-term trends in health, welfare, and economic growth in the United States. University of Chicago Press for National Bureau of Economic Research; Chicago: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Truong KD, Sturm R. Weight gain trends across sociodemographic groups in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1602–1606. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.043935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kant AK, Graubard BI. Secular trends in the association of socio-economic position with self-reported dietary attributes and biomarkers in the US population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1971-1975 to 1999-2002. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(2):158–167. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007246749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prättälä R, Sippola R, Lahti-Koski M, Laaksonen MT, Mäkinen T, Roos E. Twenty-five year trends in body mass index by education and income in Finland. BMC Public Health. 2012;(12):936. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1985;14(1):32–38. doi: 10.1093/ije/14.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Center for Disease Control Overweight and Obesity. 2013 http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.htm.

- 16.Hill JO, Wyatt H, Aschwanden C. State of Slim: Fix Your Metabolism and Drop 20 Pounds in 8 Weeks on the Colorado Diet. Rodale. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson JP, Godbey GG. Time for Life: The Surprising Ways Americans Use Their Time. Vol 2nd Ed Pennsylvania State University Press; University Park, PA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sturm R. Stemming the global obesity epidemic: What can we learn from data about social and economic trends? Public Health. 2008;122(8):739–746. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bureau of Labor Statistics American Time Use Survey: Time Spent in Detailed Primary Activities, and Percent of the Civilian Population Engaging in Each Detailed Activity Category. Averages Per Day By Sex. Table A1. 2013.

- 20.Cutler D, Glaeser E, Shapiro J. Why Have Americans Become More Obese? J Econ Perspect. 2003;17(3):93–118. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Variyam JN. The Price is Right: Economics and the Rise in Obesity. Amber Waves. 2005;3(1):20–27. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations . The State of Food Insecurity in the World. Rome: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.NPD Group NPD’s New Dieting Monitor Tracks America’s Dieting Habits. 2004.

- 24.Kaufman W. Atkins Bankruptcy a Boon for Pasta Makers. 2005 http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4783324.

- 25.Blanck H, Gillespie C, Kimmons J, Seymour J, Serdula M. Trends in Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Among U.S. Men and Women, 1994-2005. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(2):A35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rolls BJ, Drewnowski A, Ledikwe JH. Changing the energy density of the diet as a strategy for weight management. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(5 Suppl 1):S98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams RA, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Assessment of satiety depends on the energy density and portion size of the test meal. Obesity. 2014;22(2):318–324. doi: 10.1002/oby.20589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bleich S, Wang Y, Wang Y, Gortmaker S. Increasing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among US adults: 1988-1994 to 1999-2004. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(1):372–381. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen DASR, Scott M, Farley TA, Bluthenthal R. Not Enough Fruit and Vegetables or Too Many Cookies, Candies, Salty Snacks, and Soft Drinks? Public Health Rep. 2010;125(1):88–95. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakdawalla D, Philipson T. The growth of obesity and technological change. Econ Hum Biol. 2009;7(3):283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen D, Farley TA. Eating as an Automatic Behavior. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(1):A23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drewnowski A, Specter SE. Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(1):6–16. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drewnowski A. Obesity and the food environment: dietary energy density and diet costs. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(3S):154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dietz WH. Does hunger cause obesity? Pediatrics. 1995;95(5):766–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hruschka DJ. Do economic constraints on food choice make people fat? A critical review of two hypotheses for the poverty-obesity paradox. Am J Hum Biol. 2012;24(3):277–285. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sturm R, Bao Y. Socioeconomics of Obesity. In: Kushner R, Bessesen DH, editors. Contemporary Endocrinology: Treatment of the Obese Patient. The Humana Press, Inc.; Totowa, NJ: 2007. p. 444. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Kho ME, et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thorp A, Owen N, Neuhaus M, Dunton D. Sedentary Behaviors and Subsequent Health Outcomes in Adults: A Systemic Review of Longitudinal Studies, 1996-2011. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;41(2):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lynch B. Sedentary Behavior and Cancer: A Systemtic Review of the Literature and Proposed Biological Mechanisms. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2010;19:2691–2709. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frumkin H. Urban sprawl and public health. Public Health Rep. 2002;117(3):201–217. doi: 10.1093/phr/117.3.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frank LD, Andresen MA, Schmid TL. Obesity Relationships with Community Design, Physical Activity, and Time Spent in Cars. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sturm R, Cohen DA. Suburban Sprawl and Physical and Mental Health. Public Health. 2004;118(7):488–496. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papas MA, Alberg AJ, Ewing R, Helzlsouer KJ, Gary TL, Klassen AC. The Built Environment and Obesity. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29(1):129–143. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dunton GF, Kaplan J, Wolch J, Jerrett M, Reynolds KD. Physical Environmental Correlates of Childhood Obesity: A Systematic Review. Obes Reviews. 2009;10(4):393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feng J, Glass TA, Curriero FC, Stewart WF, Schwartz BS. The Built Environment and Obesity: A Systematic Review of the Epidemiologic Evidence. Health Place. 2010;16(2):175–190. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lachowycz K, Jones AP. Greenspace and Obesity: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Obes Rev. 2011;12(5):e183–e189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Durand CP, Andalib M, Dunton GF, Wolch J, Pentz MA. A Systematic Review of Built Environment Factors Related to Physical Activity and Obesity Risk: Implications for Smart Growth Urban Planning. Obes Rev. 2011;12(5):e173–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saelens BE, Handy SL. Built Environment Correlates of Walking: A Review. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2008;40(7 Suppl):S550. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c67a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCormack GR, Shiell A. In search of Causality: A Systematic Review of the Relationship Between the Built Environment and Physical Activity Among Adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):125. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krieger J, Saelens BE. Impact of Menu Labeling on Consumer Behavior: A 2008-2012 Update. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ding D, Sallis J, Kerr J, Lee S, Rosenberg DE. Neighborhood Environment and Physical Activity Among Youth: A Review. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4):442–455. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sugiyama T, Neuhaus M, Cole R, Giles-Corti B, Owen N. Destination and Route Attributes Associated with Adults’ Walking: A Review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(7):1275–1286. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318247d286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Drewnowski A, Aggarwal A, Hurvitz PM, Monsivais P, Moudon AV. Obesity and Supermarket Access: Proximity or Price? Am J Public Health. 2012;8:e74–80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.An R, Sturm R. School and Residential Neighborhood Food Environment and Diet Among California Youth. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(2):129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hattori A, An R, Sturm R. Neighborhood Food Outlets, Diet, and Obesity Among California Adults, 2007 and 2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E35. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Caspi CE, Sorensen G, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. The Local Food Environment and Diet: A Systematic Review. Health Place. 2012;5:1172–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cummins S, Flint E, SA M. New neighborhood grocery store increased awareness of food access but did not alter dietary habits or obesity. Health Affairs. 2014;33(2):283–291. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wallop H, Spencer P. 3,000 Greengrocers Lost in Last Decade. The Telegraph. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sturm R. Affordability and Obesity: Issues in the Multifunctionality of Agricultural/Food Systems. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2009;4(3-4):454–465. doi: 10.1080/19320240903336522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.European Commission Political agreement on new direction for common agricultural policy. 2013 http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-13-613_en.htm.

- 61.Wallinga D. Agricultural policy and childhood obesity: a food systems and public health commentary. Health Affairs. 2010;29(3):405–410. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, Farm Bill Resources. 2014.

- 63.Powell LM, Chriqui JF, Khan T, Wada R, Chaloupka FJ. Assessing the Potential Effectiveness of Food And Beverage Taxes and Subsidies for Improving Public Health: A Systematic Review of Prices, Demand and Body Weight Outcomes. Obes Rev. 2013;14(2):110–128. doi: 10.1111/obr.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sturm R, Datar A. Body Mass Index in Elementary School Children, Metropolitan Area Food Prices and Food Outlet Density. Public Health. 2005;119(12):1059–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sturm R, Datar A. Food Prices and Weight Gain During Elementary School: 5-Year Update. Public Health. 2008;122(11):1140–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sturm R, Datar A. Regional Price Differences and Food Consumption Frequency Among Elementary School Children. Public Health. 2011;125(3):136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Andreyeva T, Long MW, Brownell KD. The Impact of Food Prices on Consumption: A Systematic Review of Research on the Price Elasticity of Demand for Food. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):216–222. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.151415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Powell LM, Chaloupka FJ. Food Prices and Obesity: Evidence and Policy Implications for Taxes and Subsidies. Milbank Quarterly. 2009;87(1):229–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Holt E. Hungary to introduce broad range of fat taxes. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):755. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61359-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sturm R, An R, Segal D, Patel D. A Cash-Back Rebate Program for Healthy Food Purchases in South Africa: Results from Scanner Data. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(6):567–572. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Faulkner GE, Grootendorst P, Nguyen VH, et al. Economic Instruments for Obesity Prevention: Results of a Scoping Review and Modified Delphi Survey. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:109. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sturm R. Stemming the Global Obesity Epidemic: What Can We Learn from Data About Social and Economic Trends? Public Health. 2008;122(8):739–746. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Monsivais P, Rehm C. Potential Nutritional and Economic Effects of Replacing Juice With Fruit in the Diets of Children in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(5):459–464. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lindstrom J. The Diabetes Risk Score: A practical tool to predict type 2 diabetes risk. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Wojcicki J, Heyman M. Reducing Childhood Obesity by Eliminating 100% Fruit Juice. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(9):1630–1633. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Institute of Medicine . The Public Health Effects of Food Deserts. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]