Abstract

Background

At laparoscopic cholecystectomy, most surgeons have adopted the operative approach where the ‘critical view of safety’ (CVS) is achieved prior to dividing the cystic duct and artery. This prospective study evaluated whether an adequate critical view was achieved by scoring standardized intra-operative photographic views and whether there were other factors that might impact on the ability to obtain an adequate critical view.

Methods

One hundred consecutive patients undergoing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy were studied. At each operation, two photographs were taken. Two independent experienced hepatobiliary surgeons scored the photographs on whether a critical view of safety was achieved. Inter-observer agreement was calculated using the weighted kappa coefficient. The Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test was used to analyse the scores with potential confounding clinical factors.

Results

The kappa coefficient for adequate display of the cystic duct and artery was 0.49; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.33 to 0.64; P = 0.001. No bias was detected in the overall scorings between the two observers (χ2 1.33; P = 0.312). Other clinical factors including surgeon seniority did not alter the outcome [odds ratio (OR) 0.902; 95% confidence interval 0.622 to 1.264].

Conclusion

Heightened awareness of the CVS through mandatory documentation may improve both trainee and surgeon technique.

Introduction

Since the introduction and routine use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the 1990s, the reported incidence of biliary injuries has doubled to 0.4%.1,2 Many factors have been shown to influence the risk of biliary injury including patient factors (obesity, older age, male gender and adhesions), local factors (severe gallbladder inflammation/infection, aberrant anatomy and haemorrhage) as well as surgeon volume.3 Given that most of these are beyond the surgeon's control, heightened alertness to the increased risk of injury is an important consideration when any of these factors are present.

Identifying the common bile duct as the cystic duct is the commonest cause of major bile duct injury;4–7 active identification of cystic structures within Calot's triangle is the key to a reduction in biliary injury. Strasberg first coined the term ‘critical view of safety’ (CVS) in 19958 and this approach of identification of cystic structures has been adopted by many surgeons as the standard of operative technique to reduce the incidence of biliary injury.

To fulfil the criteria for a CVS requires Calot's triangle to be cleared free of fat and fibrous tissue (‘fat cleared’), for the lowest part of the gallbladder to be dissected free from the cystic plate (‘liver visible’) and for there to be only two structures entering the gallbladder (‘2 structures’).8 The published rate of bile duct injury is low and prohibitively large numbers would be needed to conduct a randomized trial to ascertain whether Strasberg's approach actually decreases the rate of major bile duct injury.9

A quality audit in surgery involves reviewing surgical performance and comparing this with accepted standards of what this performance should be.10 Most often, surgical outcomes such as complication and mortality rates are measured. However, surgeons should also be scrutinizing their actual practices and processes, and auditing how well they are performing these in order to improve patient care. The steps taken to achieve the CVS may in fact be more important than the actual final view obtained. To take aviation safety as an example, monitoring of how often the pre-flight check is performed, rather than the frequency of airplane crashes.

Aim

The aim of this study was to prospectively audit how often an adequate CVS during a laparoscopic cholecystectomy was achieved and if there were other potential confounding factors that might impact on the ability to obtain an adequate critical view.

Methods

One hundred consecutive patients undergoing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy at a metropolitan tertiary teaching hospital were prospectively studied. Patients undergoing both elective and emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy were included. Demographic data, indication for surgery, operative diagnosis, clinical data and operative time were collected.

The surgeon was instructed to take two photos once the critical view had been obtained and when no further dissection is to be performed prior to clipping/division of the cystic duct and artery. These were scanned and de-identified, then reviewed by two independent examiners (both specialist hepatobiliary surgeons). They scored each photo on the three criteria set by Strasberg,8 as well as an overall mark of adequate, borderline or inadequate. Confounding factors that might potentially influence the difficulties of the procedure [age, gender, body mass index (BMI), diabetic status, white cell count, gallbladder wall thickness, ‘American’ (supine) or ‘French’ (low lithotomy) approach] were recorded. Operator experience – whether the primary operator was a consultant or trainee – was also recorded. The consultant surgeon, although available, did not physically participate during the trainees' procedures.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using STATA v12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Inter-observer agreement for scores of the CVS was assessed using the weighted kappa (κw) statistic (quadratic weighting) for ordered categories. A minimum sample size of 38 patients for two observers was calculated to achieve a power of 80% (two-sided alpha = 0.05) to detect κw > 0.4. For analysis of bias between the two observers (one giving consistently higher or lower scores than the other), an exact single binomial test was used to calculate a χ2 where two-sided P < 0.05 indicates bias between observers.11 A three-way tabulation for the operator, the scores (‘borderline’ and ‘inadequate’ combined as ‘inadequate’) and potential confounding factors was analysed using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test. A significant P-value implies that clinical factors might have influenced the scores of the operators. Two-sided P < 0.05 was chosen to be statistically significant.

Ethics approval was obtained from the institution's Low Risk Ethics Panel according to the requirements of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and assigned the project number QA2012.75.

Results

Data on the 100 patients undergoing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy are shown in Table 1. An intra-operative cholangiogram was successfully completed in 91 of the operations. There were no conversions to open operation and one bile leak which settled without the need for further intervention. The only other major complication was an infected collection requiring computed tomography-guided percutaneous drainage.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data for 100 patients undergoing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy

| Gender | |

| Male | 35 |

| Female | 65 |

| Age (years) | |

| Median (IQR) | 49 (33–70) |

| Diabetic (%) | 13 |

| BMI | |

| Median (IQR) | 28 (25–33) |

| Timing of Surgery | |

| Elective | 72 |

| Emergency | 28 |

| Gallbladder wall | |

| >3 mm | 39 |

| ≤3 mm | 61 |

| Positioning | |

| French | 30 |

| American | 70 |

| WCC (×106) | |

| Median (IQR) | 7.20 (6.08–8.93) |

| Surgeon | |

| Consultant | 20 |

| Trainee | 80 |

| Indication | |

| Biliary colic | 51 |

| Gallstone pancreatitis | 18 |

| Acute cholecystitis | 15 |

| Gallbladder polyps | 7 |

| Choledocholithiasis/cholangitis | 6 |

| Othera | 3 |

IQR, inter-quartile range.

1 idiopathic pancreatitis, 1 acalculous cholecystitis, 1 not documented.

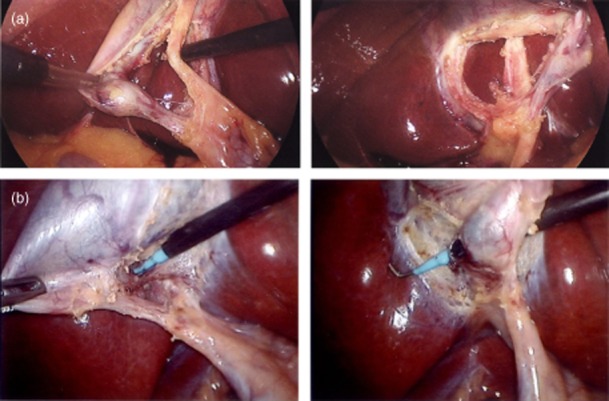

The frequencies of the two observers' scores are listed in Table 2a. The weighted kappa coefficient (κw) was strongest for the display of ‘2 structures’ (0.49) and weakest for ‘fat cleared’ (0.18) (Table 2b). There was no bias detected in the overall ratings of the two observers (χ2 1.33; 1 d.f. P = 0.312). An example of a CVS with an ‘adequate’ overall score is seen in Fig. 1a, and an ‘inadequate’ overall score in Fig. 1b.

Table 2a.

Frequencies of observers' scores for the critical view of safety (CVS) photos (n = 100)

| Two structures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observer 2 | Observer 1 | |||

| Adequate | Borderline | Inadequate | Total | |

| Adequate | 42 | 2 | 1 | 45 |

| Borderline | 23 | 2 | 3 | 28 |

| Inadequate | 9 | 5 | 13 | 27 |

| Total | 74 | 9 | 17 | 100 |

| Fat cleared | ||||

| Observer 2 | Observer 1 | |||

| Adequate | Borderline | Inadequate | Total | |

| Adequate | 30 | 7 | 3 | 40 |

| Borderline | 26 | 6 | 5 | 37 |

| Inadequate | 13 | 3 | 7 | 23 |

| Total | 69 | 16 | 15 | 100 |

| Liver visible | ||||

| Observer 2 | Observer 1 | |||

| Adequate | Borderline | Inadequate | Total | |

| Adequate | 37 | 7 | 6 | 50 |

| Borderline | 17 | 8 | 2 | 27 |

| Inadequate | 5 | 8 | 10 | 23 |

| Total | 59 | 23 | 18 | 100 |

| Overall score | ||||

| Observer 2 | Observer 1 | |||

| Adequate | Borderline | Inadequate | Total | |

| Adequate | 30 | 11 | 4 | 45 |

| Borderline | 15 | 10 | 5 | 30 |

| Inadequate | 7 | 6 | 12 | 25 |

| Total | 52 | 27 | 21 | 100 |

Table 2b.

Inter-observer agreement and bias of CVS scores

| κw | 95% CI | P | Biasχ2 | pbias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two structures | 0.49 | 0.33 to 0.64 | 0.001 | 22.35 | 0.001 |

| Fat cleared | 0.18 | 0.01 to 0.36 | 0.020 | 12.79 | 0.001 |

| Liver visible | 0.39 | 0.20 to 0.58 | 0.001 | 5.00 | 0.036 |

| Overall | 0.38 | 0.19 to 0.57 | 0.001 | 1.33 | 0.312 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Figure 1.

(a) Example of an ‘adequate’ critical view of safety photo. (b) Example of an ‘inadequate’ critical view of safety photo

There was no difference in achieving adequate CVS scores with operator experience (consultant vs. trainees) when analysed against potential clinical confounding factors. An odds ratio (ORs) Forest Plot did not favour consultants or trainees [combined OR: 0.902; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.622 to 1.264].

Discussion

Inter-observer agreement using photographic documentation of the critical view of safety was better than one would expect by chance in this prospective study. Furthermore, there was no bias detected in the overall ratings between the two observers. The measured rate of an adequate critical view of safety was 52% and 45% from two experienced observers. This is similar to a recent study by Buddingh et al.12 The highest agreement and largest numbers of adequate score for the critical view was in the ‘two structures’ category. Arguably, definitive demonstration of the cystic duct and artery entering the gallbladder is the most objective of the three criteria for a CVS as defined by Strasberg.8

In the analyses of potential clinical factors that might impact on the ability to achieve an adequate critical view, a conservative approach was adopted by combining the ‘borderline’ and ‘inadequate’ scores as ‘inadequate’ as it was not possible to gauge how many ‘borderline’ scores belong to either the ‘adequate’ or ‘inadequate’ categories.

There are limitations to this study. Awareness of being ‘observed’ (the Hawthorne effect13) could very well have influenced the performance of the operators. It may be argued that this is a positive effect of the study. Perhaps in future all surgeons should document the critical view at all laparoscopic cholecystectomies: to remind the surgeon to take a small moment to assess the structures on the screen and be certain the critical view is in fact adequately displayed prior to any division of structures. These could then be randomly audited for quality control purposes. Comments from the two observers highlighted that the photo quality affected the scoring for some patients and previous studies have suggested that taking a short video may provide a more accurate documentation of the CVS.14

Examples of audits already used for quality assessment in surgery are: monitoring the caecal intubation rate as a surrogate for completeness of a colonoscopy;15,16 determining how often the recurrent laryngeal nerves are identified at thyroidectomy17; and documenting lymph node counts in bowel cancer surgery.18 A laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a common operation, but can incur the potentially devastating complication of major bile duct injury. Given this, ongoing scrutiny of a surgeon's practice is important to ensure the best outcomes are achieved for patients. In the future, mandatory documentation of the CVS will be performed in this unit for audit and educational purposes. A recent publication has created a proposed laparoscopic cholecystectomy checklist to attempt to create a standard approach to the operation.19 Perhaps not only the CVS, but also the key steps leading to this should be documented. These and scoring systems such as that described by Eubanks et al.20 would potentially make for more structured and reliable methods of teaching trainees or auditing surgeons.

A further prospective study of the documentation of the steps during a laparoscopic cholecystectomy and exploring more accurate ways to document the CVS (such as with a short video clip) is planned. It is probable that using photos alone to document the adequacy of the CVS may not provide the medico-legal protection that some surgeons may believe these pictures confer.

Within the limitations of the photographic documentation used in the current study an adequate CVS was achieved only approximately half of the time. Although the true rate is likely to be higher owing to the varying quality of the photographs, it can still be improved upon. It does not appear there were any particular factors that correlated with a lower likelihood of achieving a CVS – including operator experience. Ongoing scrutiny of this common operation is required to provide continuing improvement.

In summary, this study has demonstrated that an adequate and safe display of the cystic duct and artery was achieved as assessed by photographic documentation with good inter-rater agreement. Factors including seniority of the operator did not affect the performance; however, this study was not powered to specifically examine this. A heightened awareness of the CVS through mandatory documentation may improve both trainee and surgeon technique in laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to our independent observers of the CVS photos: Mr Peter Evans and Mr Saxon Connor.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Giovannini I, Ardito F, D'Acapito F, Vellone M, et al. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: results of an Italian national survey on 56591 cholecystectomies. Arch Surg. 2005;140:986–992. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savassi-Rocha PR, Ferreira JT, Diniz MT, Sanchez SR. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Brazil: analysis of 33 563 cases. Int Surg. 1997;82:208–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YV, Linehan DC. Bile duct injuries in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:787–802. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigot J, Etienne J, Aerts R, Wibin E, Dallemagne B, Deweer F, et al. The dramatic reality of biliary tract injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an anonymous multicenter Belgian survey of 65 patients. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:1171–1178. doi: 10.1007/s004649900563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff AM, Pappas TN, Murray EA, Hilleren DJ, Johnson RD, Baker ME, et al. Mechanisms of major biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 1992;215:196–202. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199203000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker SW, Hugh TB. Laparoscopic bile duct injury: understanding the psychology and heuristics of the error. ANZ J Surg. 2008;78:1109–1114. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2008.04761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kholdebarin R, Boetto J, Harnish JL, Urbach DR. Risk factors for bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a case-control study. Surg Innov. 2008;15:114–119. doi: 10.1177/1553350608318144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:101–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasberg SM, Brunt LM. Rationale and use of the critical view of safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal Australasian College of Surgeons. Surgical Audit and Peer Review: A Guide By the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons. 3rd edn. Melbourne: Royal Australasian College of Surgeons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ludbrook J. Statistical techniques for comparing measurers and methods of measurement: a critical review. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2002;29:527–536. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buddingh KT, Morks AN, ten Cate Hoedemaker HO, Blauww CB, van Dam GM, Ploeg RJ, et al. Documenting the correct assessment of biliary anatomy during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:79–85. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1831-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale EAM. The Hawthorne studies – a fable for our times? Q J Med. 2004;97:439–449. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hch070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaiser PW, Pauwels MMS, Lange JF. Quality control in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: operation notes, video or photo print? HPB. 2001;3:197–199. doi: 10.1080/136518201753242208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:873–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Bowel Cancer Screening Program Quality Working Group. Improving Colonoscopy Services in Australia. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2009. [WWW document]. URL http://www.cancerscreening.gov.au/internet/screening/publishing.nsf/Content/3FD09B61D2B4E286CA25770B007D1537/$File/Improving%20col%20serv0709.pdf (last accessed 29 December 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar S, Randolph G, Seidman M, et al. Clinical practice guideline: improving voice outcomes after thyroid surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(6 Suppl):S1–S37. doi: 10.1177/0194599813487301. . doi: 10.1177/0194599813487301 [WWW document]. URL http://oto.sagepub.com/content/148/6_suppl/S1.full.pdf+html (last accessed 29 December 2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otchy D, Hyman NH, Simmang C, Thomas A, Buie WD, Cataldo P, et al. Practice parameters for colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1269–1284. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0598-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor SJ, Perry W, Nathanson L, Hugh TB, Hugh TJ. Using a standardized method for laparoscopic cholecystectomy to create a concept operation-specific checklist. HPB (Oxford) 2013 doi: 10.1111/hpb.12161. . [WWW document]. URL http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezproxy.surgeons.org/doi/10.1111/hpb.12161/full (last accessed 29 December 2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eubanks TR, Clements RH, Pohl D, Williams N, Schaad DC, Horgan S, et al. An objective scoring system for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:566–574. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]