Abstract

Transmission electron microscopic studies on CS2 hydrolase provide direct evidence for the existence of the hexadecameric catenane and octameric ring topologies. Reconstructions of both protein assemblies are in good agreement with crystallographic analyses of the catenane and ring forms of CS2 hydrolase.

Molecular topology, the organisation of molecular structure in three dimensional space, often determines the physico-chemical properties of molecules and molecular systems.1 Molecular topology has most notably been recognised in biochemistry by providing the link between the function and structure of biomolecules.2 Naturally-occurring and designed protein assemblies that exist in a diverse set of supramolecular topologies, including catenanes, knots, tubes, cages, and rings have been identified and characterised.3, 4

CS2 hydrolase from hyperthermophilic Acidianus A1–3 archaeon appears in two well-defined oligomeric states, namely the hexadecameric catenane and the octameric ring assemblies. The active site of both assemblies contains the zinc ion cofactor, which is chelated by two cysteines and one histidine. Both forms of the enzyme are catalytically active for the conversion of CS2 into CO2 and H2S.5–7 The non-covalently maintained hexadecameric catenane and octameric ring assemblies have been detected in the crystal state, gas phase and dilute aqueous solutions.5–7 High-resolution structural analyses of both assemblies illustrated that the ring form exhibits a square-shaped geometry and that the two mechanically-interlocked rings in the catenane architecture are positioned perpendicularly (i.e. the angle between both octameric rings is exactly 90°).5 Comparative biochemical analyses of the catenane and ring forms of CS2 hydrolase demonstrated that the catanene is enzymatically more active then the ring (per assembly), whereas the ring is overall more active (per monomer).7 A decreased enzymatic activity for the catenane can be attributed, at least in part, to the compact organisation of both rings in the catenane, that makes some of its sixteen active sites partially inaccessible for binding of CS2 substrate.7

To date, the catenane topology of protein assemblies has only been demonstrated by X-ray structural analyses. The catenane quaternary structure has been verified for: (i) CS2 hydrolase,5 (ii) bacteriophage HK97,8, 9 (iii) citrate synthase,10 (iv) mitochondrial peroxiredoxin III,11 (v) recombinant protein RecR,12 and (vi) ribonucleotide reductase (RNR).13 In addition to crystallographic support, there have been limited additional biophysical and bioanalytical data that support the existence of the unique catenane topologies in the protein world. Most solution state data have only provided complementary indirect support of catenane topology. Few catenane proteins have been examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and only in low resolution 2-D images.7, 14 In the case of peroxiredoxin III, interestingly, TEM preparation caused the catenane form of the protein to almost completely disassemble into rings.14 Nevertheless, the presences of catenane forms of RecR12 and RNR13 in the crystals were resulted from high protein concentration or high crystallisation precipitant concentration. Indeed, the high protein concentration and crystal contacts which hold molecules in the symmetric crystal lattice in the crystal may influence and alter the organisation and topology of the assembly when compared to the assembly in solution, especially in proteins that have multiple conformations. Therefore, it is important to provide independent high-resolution characterisation of these protein assemblies.

Herein, we report the TEM-based 3-D reconstruction of the catenane and ring assemblies of CS2 hydrolase. To the best of our knowledge, this study presents the first 3-D TEM reconstruction of a non-covalent catenane protein. CS2 hydrolase was expressed in E. coli.6, 7 Catenane and ring forms of CS2 hydrolase were then purified by two rounds of size exclusion chromatography (SEC) in sodium phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.5).7 Low-dose TEM and single-particle reconstruction techniques were performed to analyse the spatial configurations of these two assemblies.

To initially characterize the unique hexadecameric catenane form of CS2 hydrolase, negative stained TEM micrographs were collected and 2-D image analysis was performed.15 TEM specimens were prepared by applying a dilute solution of the catenane assembly (0.1 mg mL−1) on to a glow-discharged carbon-coated grid and staining with 2% uranyl acetate (detailed methods see supplementary information). Images were collected in low-dose TEM mode to minimize radiation damage caused by the electron beam.

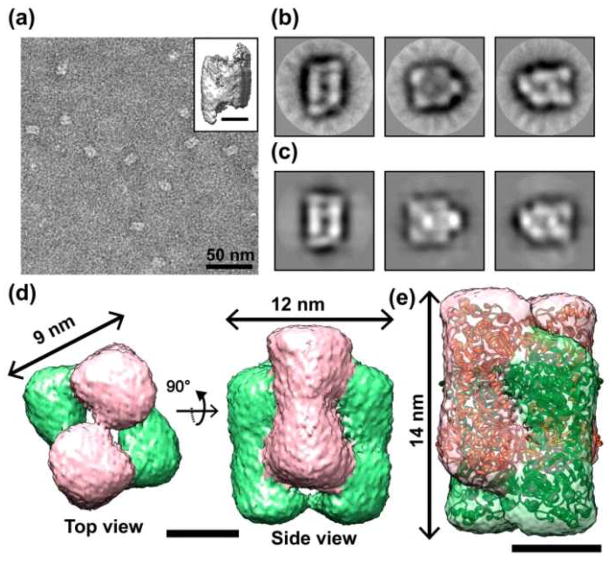

Though samples were randomly oriented, the majority of images showed short ladder-like side views and elliptical tilted views (Fig. 1a) with the measured dimension of approximately 10 nm in length and 16 nm in width. Reference-free classification allowed identification of typical views of the specimen (Fig. 1b).16, 17 These class averages clearly revealed the presence of two square-ring elements that interlocked through the central cavity. However, no class average provided a putative top view, suggesting that the sample has preferred orientations on the grid (Fig. S1 and S2).

Fig. 1.

Structural analysis of the catenane form of CS2 hydrolase. (a) A representative TEM image of negatively stained catenane assemblies. Scale bar, 50 nm. Inset shows a de novo built initial 3-D model from these particles. Scale bar, 5 nm. (b) Selected reference-free 2-D class averages and (c) their corresponding model re-projections. (d) Top view (left) and side view (right) of the 3-D reconstruction of the catenane assembly. Note that the structure showed two interlocked rings (pink and light green). Scale bar, 5 nm. (e) Transparent isosurface rendering of catenane assembly fitted with the atomic coordinates (PDB ID: 3TEO, showed in red and green) revealed a good agreement between the atomic coordinates and EM density map. Scale bar, 5 nm.

3-D models were built from the 2-D data using the EMAN software package.18 An initial 3-D model was built de novo using 19,243 particles without any symmetry constraints (Fig. 1a, inset). This model had dimensions of 9 nm × 12 nm × 14 nm. Because of the models shape, it was iteratively refined with D2 symmetry to yield the final 3-D reconstructions (Fig. 1d). The 3-D electron density map clearly showed a mechanically interlocked catenane assembly that consisted of two equal ring structures (Fig. 1c and d). Interpretation of the catenane assembly as two interlocked square rings was further supported by fitting the atomic coordinates of a CS2 hydrolase catenane assembly solved by X-ray crystallography into the TEM reconstruction (Fig. 1e). The structure shows that the rings of the catenane assembly are approximately perpendicular to one another. There was no large internal hole hidden between the two interlocked rings (Fig. 1d and e).

The squares were not uniform. Each square has the appearance of two dumbbell-shaped components connected by a narrow contact. This weak connection may be due, in part, to the paucity of top and bottom images in the raw data; this suggests that “standing up” on the grid is structurally unfavourable.

The TEM-based 3-D reconstruction of the hexadecameric catenane form of CS2 hydrolase is in good agreement with the crystallographically-obtained structure (PDB ID: 3TEO, Fig. 1e). The corners of the ring, the top and bottom of the dumbbell, are bulbous, consistent with the globular CS2 dimer. These dimers are linked by narrower stretches consistent with the N- and C-termini of CS2 hydrolase (Fig. S3). Both structures, the cryo-EM and the crystal structure, provide direct evidence for the catenated quaternary topology. The most important difference between the two techniques is that the architecture obtained by TEM, though showing the molecule envelop at the lower resolution, was observed at very dilute protein concentrations and without the network of protein-protein interactions required to stabilize a three-dimensional crystal.

To confirm the octameric quaternary structure of each ring in the catenane, TEM structures were determined for the individual octameric ring assembly. A dilute solution of ring (0.1 mg mL−1) was used for the preparation of the uranyl formate-negatively stained TEM grids. We collected about 15,666 particles of the putative ring assembly (Fig. 2a). The initial model was generated de novo without symmetry constrains (Fig. 1a, inset), to eliminate bias. The generation of reference-free 2-D class averages resulted in square ring architecture with 4 blobs of density at each corner that were connected by narrower stretches of density (Fig. 2b). These class averages clearly showed the top/bottom, side, and tilted views of the ring assembly (Fig. 2b, left, middle, and right, respectively). The top and bottom views are consistent with D4 symmetry for each ring. Class averages were consistent with re-projections of obtained from the subsequently calculated 3-D model (Fig. 2c). A final 3-D reconstruction of the ring was computed to 15 Å, somewhat better than the 23 Å catenane form (Fig. 2d and 3).

Fig. 2.

Image reconstruction of the ring form CS2 hydrolase assembly. (a) A representative TEM image of negatively stained ring assemblies. Most particles lay on the carbon-coated grid with either top view or side views. Inset shows a de novo built initial 3-D model from the selected particles. Scale bar is 5 nm. (b) Selected reference-free 2-D class averages and (c) their corresponding model re-projections. (d) Top view (top) and side view (bottom) of the 3-D reconstruction of the ring assembly. Scale bar, 5 nm. (e) Transparent isosurface rendering of ring assembly (blue) fitted with the atomic coordinates (PDB ID: 3TEN) revealed a good agreement between the atomic coordinates and EM density map. Scale bar, 5 nm.

Fig. 3.

Resolution estimation of the 3-D reconstructions. Fourier shell correlation (FSC) at the 0.5 cutoff was used to estimate the resolutions for the catenane form (solid line, 23 Å) and ring form (dashed line, 15 Å) of the CS2 hydrolase reconstructions.

The TEM-derived structure of the octamer has square ring topology with a central hole surrounded by four equally-sized assemblies. The ring is about 11 nm from side to side and the diameter of the central hole was approximately 4 nm (Fig. 2d). These distances are similar to the dimensions obtained from the X-ray structures indicating that the negative stain did not unduly distort the structure. The 3-D density map is well fit by atomic coordinates of the ring assembly (PDB ID: 3TEN): four dimers of CS2 hydrolase fit precisely into the volume, with each dimer positioned at the corner (Fig. 2e). The docked CS2 hydrolase dimers occupy essentially all of the assigned density. This structure is essentially identical to one ring of the catenane form. Notably, this indicates that this quaternary structure is also present in dilute protein concentrations.

The resolutions of the hexadecameric catenane and octameric ring forms of CS2 hydrolase were found to be 23 Å and 15 Å, respectively (Fig. 3). The negative stain used in these micrographs provides contrast, facilitating reconstruction of lower molecular weight complexes. The negative stain provides a molecular envelope but masks out most internal features. There is a slight additional loss of detail in the EM density maps due to the thickness of the stain layer. However, even with unstained cryo-EM data, these resolutions do not provide proteins’ secondary structures. Nonetheless, for our protein complexes, these resolutions provide the unambiguous proof for the catenane and ring topologies of CS2 hydrolase. Our transmission electron microscopy-based reconstruction data provide independent description of well-defined catenane and ring quaternary structures in the absence of potentially confounding crystal contacts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark van Eldijk for assistence with preparation of TEM samples. Microscopy data were collected at the IU Electron Microscopy Center. J.C.-Y.W and A.Z. were supported by NIH-R01-AI077688 to A.Z.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Procedures and additional data for the transmission electron microscopy experiments. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Contributor Information

Joseph Che-Yen Wang, Email: wangjoe@indiana.edu.

Jasmin Mecinović, Email: j.mecinovic@science.ru.nl.

References

- 1.Forgan RS, Sauvage JP, Stoddart JF. Chem Rev. 2011;111:5434–5464. doi: 10.1021/cr200034u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petsko GA. Protein structure and function. New Science Press; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeates TO, Norcross TS, King NP. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11:595–603. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanghamitra NJ, Ueno T. Chem Commun. 2013;49:4114–4126. doi: 10.1039/c2cc36935d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smeulders MJ, Barends TR, Pol A, Scherer A, Zandvoort MH, Udvarhelyi A, Khadem AF, Menzel A, Hermans J, Shoeman RL, Wessels HJ, van den Heuvel LP, Russ L, Schlichting I, Jetten MS, Op den Camp HJ. Nature. 2011;478:412–416. doi: 10.1038/nature10464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Eldijk MB, van Leeuwen I, Mikhailov VA, Neijenhuis L, Harhangi HR, van Hest JC, Jetten MS, Op den Camp HJ, Robinson CV, Mecinovic J. Chem Commun. 2013;49:7770–7772. doi: 10.1039/c3cc43219j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Eldijk MB, Pieters BJ, Mikhailov VA, Robinson CV, van Hest JCM, Mecinovic J. Chem Sci. 2014;5:2879–2884. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helgstrand C, Wikoff WR, Duda RL, Hendrix RW, Johnson JE, Liljas L. J Mol Biol. 2003;334:885–899. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wikoff WR, Liljas L, Duda RL, Tsuruta H, Hendrix RW, Johnson JE. Science. 2000;289:2129–2133. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boutz DR, Cascio D, Whitelegge J, Perry LJ, Yeates TO. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:1332–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao Z, Roszak AW, Gourlay LJ, Lindsay JG, Isaacs NW. Structure. 2005;13:1661–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee BI, Kim KH, Park SJ, Eom SH, Song HK, Suh SW. EMBO J. 2004;23:2029–2038. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimanyi CM, Ando N, Brignole EJ, Asturias FJ, Stubbe J, Drennan CL. Structure. 2012;20:1374–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao Z, Bhella D, Lindsay JG. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:1022–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li C, Wang JC, Taylor MW, Zlotnick A. J Virol. 2012;86:13062–13069. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01033-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorzano CO, Bilbao-Castro JR, Shkolnisky Y, Alcorlo M, Melero R, Caffarena-Fernandez G, Li M, Xu G, Marabini R, Carazo JM. J Struct Biol. 2010;171:197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorzano CO, Marabini R, Velazquez-Muriel J, Bilbao-Castro JR, Scheres SH, Carazo JM, Pascual-Montano A. J Struct Biol. 2004;148:194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ludtke SJ, Baldwin PR, Chiu W. J Struct Biol. 1999;128:82–97. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.