Abstract

Honey bees form complex societies with a division of labor for reproduction, nutrition, nest construction and maintenance, and defense. How does it evolve? Tasks performed by worker honey bees are distributed in time and space. There is no central control over behavior and there is no central genome on which selection can act and effect adaptive change. For 22 years we have been asking these questions by selecting on a single social trait associated with nutrition: the amount of surplus pollen (a source of protein) that is stored in combs of the nest. Forty-two generations of selection have revealed changes at biological levels extending from the society down to the level of the gene. We show how we constructed this vertical understanding of social evolution using behavioral and anatomical analyses, physiology, genetic mapping, and gene knockdowns. We map out the phenotypic and genetic architectures of food storage and foraging behavior and show how they are linked through broad epistasis and pleiotropy affecting a reproductive regulatory network that influences foraging behavior.

Keywords: genetic mapping, reproductive ground plan, pollen hoarding syndrome, evo-devo, insulin signaling, social evolution

1. BACKGROUND

The honey bee is the only social insect that has been successfully bred for social traits with clear documentation of selective improvement. The most successful and best documented case demonstrates how selection on a social phenotype resulted in changes in the reproductive anatomy and regulatory network effecting changes in social behavior (6; 39; 68). Reproductive mechanisms and social behavior have dominated hymenopteran genetics since their origin more than 160 years ago. In 1845, Johannes Dzierson, a parish priest in Salesia (now a part of Poland) published a paper where he hypothesized that male honey bees are derived from unfertilized eggs (25). They have mothers but no fathers. Female honey bees are derived from fertilized eggs, they are biparental. His hypothesis, the first proposed mechanism for sex determination, was met with great skepticism from his beekeeping colleagues but was confirmed in 1856 by Carl Th. von Siebold (114) whose microscopic studies showed that male-destined eggs did not contain sperm. This was 50 years before the discovery of sex chromosomes (121). Subsequent cytological studies of Nachstheim (61) confirmed that male honey bees had a single set of chromosomes (haploid) while females had two sets (diploid). Recently, a single gene was identified and characterized, the complementary sex determining (csd) gene, that provides the primary signal for haplodiploid sex determination in honey bees (13; 32).

Dzierson's discovery did not go unnoticed by Gregory Mendel. He wanted to use Dzierson's discovery of haplodiploidy to confirm his theory of inheritance with an animal system. The basic idea was to produce queens that were hybrids of two different geographical races that differed in body color, black and yellow. Then, since the males have no fathers, the two color types should segregate equally in male progeny of the queen. However, he ran into the immediate difficulty that honey bee queens mate with many males (106) while they fly through the air, often kilometers away from the hive (nest); he was unable to control which males were successful (49; 65; 71). The lack of control of mating also thwarted his life-long ambition to breed bees to be better honey producers, a social trait.

It took nearly 150 years before the problem, the control of mating, was solved through the efforts of Loyd Watson, W.J. Nolan, Otto Mackensen, and Harry Laidlaw (53). Their efforts spanned three decades but by the 1950's instrumental insemination technology was perfected, and control of honey bee matings was possible. Honey bee genetics began in earnest. One carefully executed and documented case of successful artificial selection is that of Hellmich et al. (39). They successfully selected lines of honey bees that stored more (high lines) and less (low lines) pollen. Page and Fondrk (68) used the social phenotype, selection, and breeding methods of Hellmich et al. to begin an investigation of the genetic and phenotypic architectures of a social trait across levels of biological organization. Their endeavor was joined by others who now form a collaborative community.

2. HONEY BEE NATURAL HISTORY

A honey bee society (colony) typically consists of a single queen who has mated with a large number of males (estimates vary but often more than 10) and store their sperm for her normal egg laying life of 1–2 years. Ten to 40,000 facultatively sterile worker adults, all female, perform all the tasks required for colony growth, maintenance, and defense. Anywhere from zero to several hundred males may be present, depending on the time of year. Worker adults progress through a behavioral-developmental process where they perform tasks within the nest while young, such as cleaning, feeding larvae, constructing comb, processing food, etc., to foraging outside the nest for food, water, and a building material called propolis. This transition usually takes place in the second or third week of life. The queen lays almost all of the eggs (there may be rare worker-laid eggs on occasion (67) and at any time more than 30,000 eggs, larvae, and pupae may be present (see Winston 1987(122) for review of honey bee biology).

3. A SOCIAL PHENOTYPE

Pollen hoarding is the storing of surplus pollen in wax combs of the honey bee nest. It is a complex behavior involving thousands of socially interacting individuals. The nest of a honey bee colony is organized spatially such that the eggs, larvae, and pupae (brood) are located in the 3-dimensional center of the nest toward the bottom. A thin envelope of pollen surrounds the brood. Honey is stored to the sides and the above the brood. Bees that are less than about 2 weeks old feed proteinaceous glandular secretions to developing larvae. The secretions are derived from proteins contained in the pollen consumed by the nurse bees. The quantity of pollen stored by a colony in a nest is regulated by foragers (17; 23; 24; 29; 83; 112). When stored pollen is added to a colony, pollen foraging activity is reduced until the excess is consumed. When stored pollen is removed, pollen foraging activity increases until the loss is replaced. Stored pollen inhibits pollen foraging behavior in individuals while brood pheromone, a blend of hydrocarbons produced and secreted by larvae to their external cuticle, stimulates pollen foraging (78). The response of foragers to the combination of these stimuli results in the regulation of stored pollen. Therefore, the amount of pollen stored in the comb is an easily measured phenotype that results from the combined effects of the larvae, pollen-consuming nurse bees, and pollen-collecting foragers.

4. PHENOTYPIC ARCHITECTURE

Page and Fondrk (68) selected for a single trait, high and low pollen hoarding, for more than 40 generations spanning more than 22 years (unpublished). The result was two strains of bees that differ dramatically in the amount of pollen they store. The purpose was to document changes at different levels of biological organization from colony-level traits to the genome and map the architecture of the pollen hoarding phenotype. Table 1 provides details of the phenotypic architecture along with a comprehensive list of citations supporting each entry in the table. In the sections below, we provide brief descriptions of the important consequences of colony level selection.

Table 1.

Phenotypic traits of high and low strain bees for different levels of organization. Traits differed between high and low strain bees for some traits as a consequence of the effects of selection.

| Level | Trait | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colony | stored pollen | H<L | (68) |

| stored honey | none | (68) | |

| brood area | none | (68) | |

| number of bees | none | (68) | |

| number of foragers | none | (68) | |

| number of pollen foragers | H>L | (33; 68; 72) | |

| number of nectar foragers | L>H | (33; 68; 72) | |

| proportion pollen foragers | H>L | (33; 68; 72) | |

| queen cues | none | (72) | |

| larval cues | none | (72) | |

| Individual | pollen load nectar load |

H>L L>H |

(27; 28; 33; 68; 72; 75–77; 79; 92) |

| nectar sugar concentration | L>H usually | (66; 77; 79); cf. (92) | |

| water load | H>L | (66; 75) | |

| floral preference | none | (33) | |

| age of foraging onset | L>H | (77; 79; 90) | |

| response to pollen foraging stimuli | H>L | (28; 75; 77; 111) | |

| dance for pollen | H>L | (115) | |

| scout for pollen | H>L | (22) | |

| attend pollen dances | H>L | C. Dreller & R. Page unpublished data | |

| Anatomy | body mass | L>H | (55; 56) |

| ovariole number | H>L | (1; 34; 55; 56; 89) | |

| Development | time egg-adult | H>L | (7) |

| juvenile hormone in larval stage 5 | H>L | (7) | |

| juvenile hormone in pupal stage and young adults | different dynamics | (7; 102) | |

| ecdysteroids in pupal stage and young adults | different dynamics | (7) | |

| vitellogenin in young adult workers | H>L | (2; 3; 7) | |

| vitellogenin/juvenile hormone dual repression regulation | H = yes L= no |

(2; 47) | |

| ecdysteroid production by worker ovaries | H>L | (7) | |

| sensitivity to colony rearing environment | H>L | (55; 56; 79) | |

| sensitivity to in vitro rearing environment | L>H | (56) | |

| body mass : ovariole number (reared in colonies) | Strain x rearing environment interactions | (56) (note that panels in figure 1 are reversed); 0. Kaftanoglu and R. Page unpublished data | |

| Sensory-motor | sensitivity to sugar and water | H>L | (66; 75; 79; 80; 97; 98; 110) |

| sensitivity to light | H>L | (110) | |

| locomotor activity | H>L | (42; 87) | |

| Associative learning | tactile and odor | H>L | (54; 97; 98) |

| Non-associative learning | sensitization | H>L | V. Kolavenuu & R. Page unpublished |

| habituation | L>H | V. Kolavenuu & R. Page unpublished | |

| Neuro-biochemisty | protein kinase A | H>L | (43) |

| protein kinase C | H>L | (43) | |

| octopamine | H=L | (102) | |

| serotonin | H=L | (102) | |

| dopamine | H=L | (102) |

4.1 Colony level

A significant colony-level response to selection was seen in a single generation (68). By generation 5 the high strain had 6 times more stored pollen than the low strain. Currently, the high strain hoards more than 12 times more pollen (Page and Fondrk unpublished data). The proportion of the foragers collecting pollen was increased in the high strain. This was a result of a reallocation of foragers from nectar to pollen foraging biases in the highs and from pollen to nectar in the lows. The total number of foragers did not change. Differences in stored pollen were not a consequence of differential queen or brood cues and signals (68).

4.2 Individual level

High-strain foragers initiate foraging earlier in life, are more likely to return with a load of pollen and collect larger loads of pollen than low-strain foragers. The reverse is automatically true for nectar because the number of foragers is not different between high- and low-strain colonies. Total load size is restricted for foragers, therefore, bees that collect larger pollen loads collect smaller loads of nectar (45; 69; 92). Foraging bias can be expressed as the proportion of the total foraging load that is pollen, or (pollen load)/(pollen load + nectar load).

When foraging for liquids, high strain bees are more likely to return with nectar with lower sugar concentrations and are more likely to be water foragers. This is probably a consequence of their greater response sensitivity to water and sugar solutions (see sensory-motor section below). Nectar load size positively correlates with nectar sugar concentration (69; 79; 92; 105) and pollen load size negatively correlates with nectar load. Therefore, the sensitivity to sugar is a fundamental component of honey bee forage loading algorithms (105).

Selection for pollen hoarding did not affect floral preferences, highs and lows apparently visit the same flowers, at least in the environments where they were tested (33). However, social signaling during recruitment to food sources was affected. Some foragers are scouts, they fly out from the nest without being recruited by others, and find new resources. They return and perform recruitment dances that advertise the quality and location of the food sources they discover (104; 113). High strain bees are more likely to find and recruit to pollen sources when they are scouts (22), dance more for pollen sources (115) and as potential recruits, spend more time attending pollen dances (C. Dreller and R. Page, unpublished data). High strain bees are more responsive to pollen foraging stimuli, brood pheromone and stored pollen, and demonstrate larger changes in response to changing cues and signals (28; 78; 80; 111).

4.3 Reproductive anatomy and development

Several developmental differences were noted between high and low strain workers. Some of these are likely developmental signatures of colony level selection. High strain bees require about 18 hours longer to develop from egg to adult. High strain workers have slightly lower body mass and more ovarioles than low strain bees. Using the data from Linksvayer et al. (56), high and low strain bees had wet weight body masses of 101.8 and 105.4 mg (F1,249 = 6.17; P < 0.05) and 11.2 and 9.2 ovarioles (F1,243 = 16.71 P < 0.0001), respectively. Worker honey bees normally have fewer than about 25–30 total ovarioles while queens have more than 300 (1; 34; 55; 56; 89; 91). Worker ovaries undergo programmed cell death beginning in about the 5th larval instar (100; 101). Queen ovaries are rescued from apoptosis by elevated blood titers of juvenile hormone, an insect growth regulator. Worker larvae have reduced amounts of juvenile hormone during the critical window. High strain larvae have significantly more JH and more ovarioles complete development (7). We believe this is a signature of colony selection because of the subsequent effects of worker ovaries on foraging bias (see below). JH and ecdysteroids work together in interacting dynamics throughout larval and adult reproductive development (38). High and low strain workers differ in the dynamics of these two hormones throughout development, however, the functional significance of these traits remains unknown. It is interesting to note that males of the high and low strains also differ phenotypically in their adult maturation rate, indicated by differences in the timing of the onset of mating flight behavior (87).

In insects, ovaries and fat body interact in a reproductive regulatory network (6; 38). Key signaling elements are JH produced in the corpora allata, paired glands associated with the brain, ecdysteroids produced in the ovary, and vitellogenin (Vg) produced in the fat body. When signaled, the fat body produces Vg, a lipoprotein that is taken into ovaries and incorporated into eggs. High strain ovaries produce more ecdysteroid and their fat body produces more Vg in young workers, prior to foraging (7; 109). Vg inhibits JH production and JH inhibits Vg production in a double repressor feedback loop (5). The two of them regulate the onset of foraging. Vg titres in young adults affect sensory response systems and foraging behavior later in life (47; 62; 109), as explained further below. Low strain bees have lost the double repressor regulation of JH and Vg (2; 47), another developmental signature of colony level selection on a social trait.

4.4 Sensory-motor response and learning

High strain bees are more sensitive to water and to lower concentrations of sugar solutions when tested using the proboscis extension response test (52). Sugar serves as a reward in classical associative learning studies and high strain bees perform better on the learning tests, a consequence of them placing a higher value on the sugar reward because they are more sensitive (96). Sucrose sensitivity of newly emerged bees has been shown to be linked to age of onset of foraging and foraging bias later in life (73; 74; 76).

4.5 The pollen hoarding syndrome

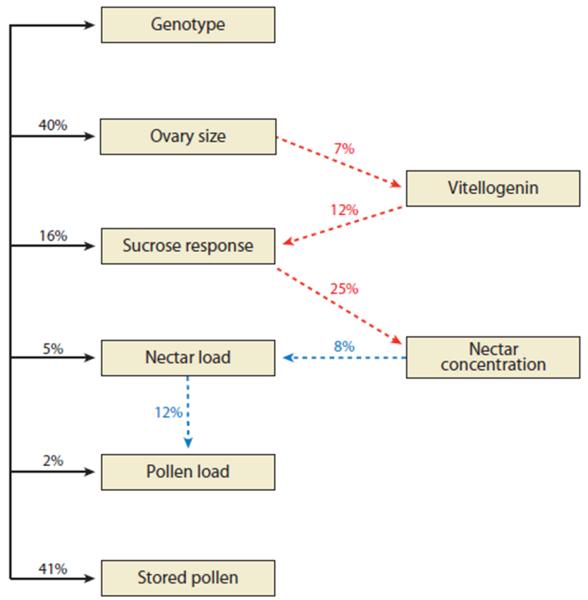

Comparison of differences found between high and low strain workers with wild-type (not part of the selected populations) revealed suites of traits that covary (Table 2) and confirm the role of colony level selection in shaping the differences observed in highs and low strains. The role of the ovaries is apparent in that wild-type bees with more ovarioles produce more vitellogenin, forage earlier in life, are more sensitive to dilute sugar solutions, and demonstrate a pollen foraging bias. Newly emerged bees that are more sensitive to sucrose solutions and water forage earlier in life, collect larger pollen loads, and as nectar foragers collect more dilute nectar. These are the anatomical and behavioral traits that define the high and low pollen hoarding strains, were a consequence of selection for pollen hoarding, and we have called the pollen hoarding syndrome (42). We assume a simple model that selection on the colony level trait affects ovary size that affects vitellogenin that affects the sensory system, measured by the response to sugar, and in turn the loading of the forager with pollen and nectar (Figure 1). Effects were measured on these components and are presented as the proportion of the variance in combined groups of high and low strain bees, or between groups of wild type bees, that can be explained by their genotypes, the statistical R2. Effects were strongest for the social trait selected. Effects on ovary size were nearly as strong, followed by sensitivity to sugar, while direct effects of genotype on individual foraging behavior were relatively weak, though statistically significant.

Table 2.

Statistically significant correlations (P < 0.05) between traits related to the pollen hoarding syndrome for high and low strain bees and for wild-type (not selected for pollen hoarding) bees.

| Correlation | Stock | References |

|---|---|---|

| Ovarioles : vitellogenin | wild-type | (1; 3; 7; 109) |

| Ovarioles : foraging onset | wild-type | (1; 116; 118) |

| Ovarioles : foraging bias | H,L; wild type, AHB, Apis cerana | (2; 88; 105; 116; 118); Siegel and Page in review |

| Ovarioles : nectar sugar concentration | H,L; wild type | (1; 105; 116) |

| Ovarioles : sucrose response | wild-type | (4) |

| Ovarioles : HR46 expression | H, L; wild type | (116–118) |

| Ovarioles : PDK1 expression | H, L, H/L backcross | (116) |

| Ovarioles :TYR expression | H, L; wild type | (117) |

| Vitellogenin : foraging onset | H,L; wild type | (47; 62) |

| Vitellogenin : nectar load | H,L; wild type | (47; 62) |

| Vitellogenin : sucrose response | wild-type | (4; 109) |

| Sucrose response : light response | H,L; wild-type | (26; 86; 110) |

| Sucrose response : associative learning | H,L; wild type, | (96–98) |

| Sucrose response : non-associative learning | wild-type | (95) |

| Sucrose response : locomotor activity | wild-type | (42) |

| Sucrose response : foraging onset | wild-type, AHB | (73; 76) |

| Sucrose response : foraging bias | wild-type, AHB | (66; 73; 74; 76; 97); A. Siegel and R. Page in review |

| Sucrose response : nectar concentration | wild-type | (73; 74; 76); A. Siegel and R. Page in review |

Figure 1.

The R2 values are presented as the percent of the total variance explained by regressing the variable shown at the head of the arrow against the variable at the base. All R2 were statistically significant (P < 0.05). The relationship between genotype and stored pollen was estimated from unpublished breeding records by R.E. Page and M.K. Fondrk: Solid black lines indicate comparisons of high- and low-strain bees, red dashed lines represent wild-type bees, and dashed-dotted blue lines indicate wild-type bees and bees from the high and low strains. Figure based on data from several studies (1, 5, 73, 76, 109; also see figure 2 in Reference 2).

The pollen hoarding syndrome was further confirmed through genomic mapping of quantitative trait loci (QTL) associated with many of the traits. The genetic architecture revealed an overlapping network of QTL showing broad epistasis and pleiotropy for the suite of traits. We identified candidate genes from the QTL regions, tested for mRNA expression differences between bees of the high and low pollen-hoarding strains, and developed RNAi knockdown methods to study their effects (see below).

5. GENETIC ARCHITECTURE

Quantitative trait locus (QTL) studies using the high and low pollen hoarding strains have revealed a highly epistatic and pleiotropic genomic network that maps onto the phenotypic architecture of the pollen hoarding syndrome. Until the mid-1990's, complex behavior in a natural context, such as the pollen hoarding syndrome, was considered by most as too stochastic to be studied genetically and only one behavioral gene, the for gene in Drosophila, had been identified in a natural context (20). However, the strong initial selection response in the divergent pollen hoarding strains encouraged genetic studies of these behavioral differences, especially because the focal trait of selection, pollen hoarding, is a highly regulated, colony-level trait (29; 39; 72). Colony-level traits result from the joint action of thousands of individuals, reducing the stochastic variance (11) that is inherent to many behavioral and other complex phenotypes.

5.1 Pollen hoarding

Thus, after two generations of divergent selection and preliminary genetic analyses (72), the first genetic mapping study of social behavior in honey bees focused on the composite trait of pollen hoarding at the colony level. The study used 38 colonies derived from backcrosses of inter-strain hybrid males to super-sister queens (70) of the high pollen hoarding selection line (45). Despite this relatively small sample size, one significant and one suggestive QTL (pln1 and pln2) were identified through genotypic analysis of the recombinant haploid fathers that sired all workers in the respective colonies (45). Although the linkage map was sufficiently saturated, further QTL could not be excluded and the identified QTL could not be localized due to the anonymous nature of the randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers that were used (45). Attesting to their true Mendelian nature however, two RAPD markers linked to the two pln QTL could be scored three generations later to reconfirm the two QTL by association with individual foraging behavior (45). Later, these RAPD markers were sequenced to convert them to genome site-specific sequence tagged site (sts) markers.

5.2 Foraging behavior

In addition to further confirmation of these existing QTL, a third and fourth QTL for foraging choices were subsequently discovered (69; 92). The first of these studies used a cross between Africanized and European honey bees to re-map the colony level trait “pollen hoarding”, verifying pln2 in this independent cross (69). The same study also re-mapped pollen hoarding in the high and low strains after outcrossing in the sixth generation, discovering a new significant QTL (pln3). After a second outcross, another backcross showed that allelic variation at pln QTL affected foraging choices of workers. Nectar load size and nectar concentration of nectar foragers and pollen load size of pollen foragers were affected by pln3, pollen load size of pollen foragers by pln2, demonstrating pleiotropy of these QTL across social and individual behavior (69).

The third QTL study of the foraging phenotype focused exclusively on individual foraging behavior of inter-strain backcross-derived workers during their first foraging trip. It used amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers for genome coverage in conjunction with the available sts markers to investigate the effects of pln1–3 and the genome region near the candidate amfor gene (92). Unlike the previous studies, reciprocal backcrosses to the pollen hoarding strains [(H×L) × H and (H×L) × L] were studied. Furthermore, interactions between genotype markers were included in the analysis, implicating all four loci in significant multi-way interactions (92). Direct effects were detected for pln2 and a marker located in the amfor region, which was named pln4 (44). In addition, two statistically significant and several new suggestive new QTL influencing worker foraging behavior were found (92). However, these QTL lacked independent confirmation and genomic localization, two important requirements for follow-up studies, and were, therefore, not investigated further.

With the assembly and annotation of the honey bee genome (19) several sts-markers were used to localize pln1–4 in the genome and identify positional candidate genes (44). This analysis suggested the insulin-insulin like signaling (IIS) pathway to be involved because genes associated with this pathway were significantly over-represented in all four pln QTL (44), including several central components to the IIS pathway (Table 3). Numerous subsequent studies of candidate gene expression and repression have since confirmed the involvement of the IIS pathway in the pollen hoarding syndrome (see below).

Table 3.

The pln QTL contain a significant number of genes associated with IIS (44)

| QTL | ILS associated genes | Total # of candidate genes | Physical size of QTL interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| pln1 | PIG-P, bazooka | 18 | 3,390kb |

| pln2 | PIP5K, HR46 | 59 | 2,106kb |

| pln3 | PI3K II, PDK1 | 32 | 1,484kb |

| pln4 | IRS | 4 | 131kb |

5.3 Sucrose responsiveness and age of foraging onset

Due to the phenotypic associations of the pollen hoarding syndrome, the genetic architecture of other behavioral phenotypes was predicted to overlap with the genetic architecture of foraging behavior and pollen hoarding. The first two traits investigated were the age of first foraging (AFF) of workers and the sucrose responsiveness of newly emerged workers and drones. High and low strain bees showed significant differences and both traits were influenced by pln QTL, particularly pln1 ((85; 90). The influence of pln1 on sucrose responsiveness was detected in workers and drones (85) confirming the association of the pollen hoarding syndrome to male behavioral phenotypes. Additional, two-way interaction effects between the remaining pln QTL were detected in the workers but not in drones (85). No new QTL for sucrose responsiveness were discovered in the high backcross, but in the low backcross and the male mapping population, two and one new QTL were discovered, respectively (85).

The age of first foraging of honey bee workers represents a textbook example of a complex life history trait. Significant genetic differentiation exists between multiple natural populations (15; 73) and between the high and low pollen hoarding strains (77). Initially, two reciprocal backcrosses of these strains were analyzed with over 400 AFLP markers, revealing four QTL (aff1–4) in addition to a direct effect of pln1 (90). After the publication of the genome sequence, three aff QTL (aff2–4) were localized and one (aff1) was rejected by a study that combined AFLP marker sequencing, combined single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) and AFLP mapping, and microsatellite genotyping (84). No formal analysis was performed to link these QTL to IIS, but the positional candidates near aff QTL include homologs of genes that are involved in metabolic regulation (e.g. amontillado (82)) and several kinases, such as PKC, which varies in expression between high and low strain workers (43), and the MAP-kinase ERK7, that influence numerous physiological processes, including reproduction. Functional genetic studies have provided corroborative evidence for some of these genes (e.g. ERK7) and the general involvement of reproductive hormones in the regulation of social behavior (120).

5.4 Ovary size in workers

Based on the finding of the phenotypic association between worker ovary size and other aspects of the pollen hoarding syndrome (Table 2), two QTL studies were conducted on the genetic architecture of worker ovary size (34; 57; 89). These studies relied on a set of SNP markers, filling the remaining linkage gaps with additional microsatellite markers. This marker strategy allowed for even genome coverage and immediate localization of the genetic effects. Three significant QTL were detected in reciprocal backcrosses between the high and low pollen hoarding strains (89). A similar crossing scheme of selected Africanized and European sources resulted in strongly transgressive phenotypes in the Africanized backcrosses (57). QTL analysis of the two crosses demonstrating the most extreme transgressive phenotypes resulted in three significant QTL (34).

Previously identified behavioral QTL showed significant effects on ovary size in both studies of the genetic architecture of ovary size. Among the pln QTL, pln2 and pln3 exhibited additive effects in the high pollen hoarding backcross (116). Effects of pln1 and pln2 were identified (34) in the parallel backcrosses to the Africanized parent while the effects of pln3 were suggestive. In these Africanized × European crosses, the aff QTL were also investigated and effects of aff2 and aff4 detected (34). In fact, the strongest ovary size QTL coincided with aff2 and the third strongest QTL overlaid pln1 in this study. Two particularly interesting candidate genes in the ovary size QTL intervals are long, non-coding RNAs that exhibit some of the most significant expression differences between the developing ovaries of workers and queens (41). Thus, widespread genetic overlap between worker ovary size and social behavior was found, confirming the central prediction of genetic co-segregation of social behavior and reproductive traits made by the reproductive ground plan hypothesis (34; 116).

In order to link the associations between the worker ovary and social behavior to hormonal dynamics, an additional QTL mapping study investigated simultaneously the ovary size of workers and their JH-titer in response to vitellogenin knock-down (see below) in a backcross of an inter-strain hybrid queen to a high pollen hoarding drone. This experiment relied on restriction site associated DNA sequencing (RAD-tag markers(10)) which can be generated rapidly in great numbers through high-throughput sequencing. As predicted, considerable overlap with previously identified QTL was found: Markers near all six previously mapped ovary size QTL showed significant effects on ovary size and two of these QTL (on chromosome 2 and 3) coincided also with the strongest genetic effects on the workers' JH titers (unpublished). Since one of these ovary QTL corresponds to aff2 and another to pln1, the association of these behavioral QTL to ovary size was additionally confirmed. Furthermore, the pln3 genotype influenced the JH titer and pln4 exhibited an effect on ovary size (48).

In sum, we have identified a network of interacting, pleiotropic genetic elements that underlie the central aspects of the pollen hoarding syndrome (Table 3). This network is partially overlapping between traits and presumably incomplete because it explains just a part of the total genetic variation. Furthermore, our body of work has revealed that the effect of particular QTL strongly depends on the genetic background. Nevertheless, single, segregating factors with considerable effects have been identified and the majority of the localized QTL have proven robust because their effects on the pollen hoarding trait network has been confirmed in additional study populations. This result is particularly remarkable in honey bees, which do not allow prolonged inbreeding and that have an exceptionally high recombination rate (12). The general importance of the main QTL is emphasized by the overlapping results between selected strain crosses and population crosses. However, we have not performed general population association studies of any QTL or candidate gene to assess its importance in population-wide variation. Follow-up studies have instead focused on expression and repression studies, particularly of the IIS genes in the pln QTL, as described in the following section.

6. CANDIDATE GENES

QTL mapping and the honey bee genome annotation provided several candidate genes involved in insulin-insulin like signaling (IIS) and hormonal response signaling in the pollen hoarding QTL regions (Table 3). In addition pln2 contains a receptor for a neuromodulator shown to affect sucrose sensitivity (99), the reproductive states of workers (93; 94; 107), and the onset of foraging (103), all components of the pollen hoarding syndrome. We looked at gene expression patterns of 6 candidate genes in fat body, brain, and ovary of high and low strain workers of different ages and found significant differences in expression for Tyr (pln2), PDK1 (pln3), and HR46 (pln2), making them targets for further investigation. Three candidate genes did not show differential expression: PAR3 (pln1), P13K (pln3), and IRS (pln4), but IRS demonstrated a trend toward elevated expression in the high strain worker fat body, and this difference was significant in a later study (118). Association studies using wild-type bees subsequently showed that PDK1 and HR46 covary in expression in the fat body with the number of ovarioles (116) suggesting that differential ecdysteroid signaling, as a consequence of ovary size (7), affects expression of those genes in the fat body. PDK1 is a kinase with downstream functions in the IIS and target of rapamycin (TOR) cascades. HR46 is an ecdysone inducible nuclear hormone receptor that is involved in many processes including nervous system development. TYR shows tissue-specific differential expression in the brain, fat body, and ovaries of high and low strain bees.

6.1. Transcriptional profiles of worker ovaries

Transcriptional patterns between high and low strain young-worker ovaries were compared (117) using an established microarray platform (35; 119) and qRT-PCR. About 20% of the 10,586 transcripts in the microarray varied between workers of the high and low pollen hoarding strains, including two of the positional candidate genes for pln QTL, TYR and HR46. In addition, HR46 and TYR were differentially expressed in wild-type workers with more, and fewer, ovarioles. Because high and low strain bees also differ in ovariole number, this supports the relationships between ovariole number and ovary expression of those candidate genes. ftz-fl1 is an additional gene of interest identified in the microarray study. ftz-fl1 and HR46 are both involved in the ecdysteroid signaling cascade and show correlated expression with ovariole number in pollen hoarding strains was well as wild-type bees (116; 117).

6.2 The function of reproductive gene expression in honey bee social behavior

QTL mapping and gene expression studies on bees from the high and low strains and on wild-type bees clearly demonstrate the links between reproduction and individual, and social behavior. They also demonstrate that reproductive regulatory systems have been used by natural selection and by the pollen hoarding artificial selection program to shape foraging division of labor in honey bees. As described above, candidate genes have emerged from these studies that warrant further functional investigation. In honey bees, adult gene expression can be suppressed by RNA interference (RNAi) mediated by inter-abdominal injections of double stranded RNA (dsRNA). The technique was first developed for long interfering (>500 bp) RNA and later expanded to short interfering (si)RNA (50; 51). Initial experiments focused on vitellogenin, which encodes a yolk protein precursor protein that is exclusively synthesized by the trophocyte cells of the fat body. Insect fat body tissue is functionally homologous to the vertebrate liver and white fat, and consists of trophocyte and oenocyte cells in honey bees. In Drosophila melanogaster, the oenocyte cells are central to lipid metabolism, while similar functional compartmentalization is not verified in honey bees. Trophocytes and oenocytes, however, differ in dsRNA accessibility. Trophocytes can take up considerable amounts of dsRNA (50) that remains detectable several days after injection (8). Oenocytes take up significantly less dsRNA, and similar reduced uptake is found in ovary and brain tissue (50). The restrictions of honey bee cells and organs to dsRNA limits the functional testing of reproductive genes in honey bee behavior, but also provides opportunities. Therefore, the genes that are expressed by trophocyte cells, like vitellogenin, currently represent the most feasible targets for functional genetic research on honey bee behavior.

The insect brain contains critical control-circuits for behavioral programs that are involved in reproduction (21). Such circuits remain challenging to manipulate with functional genetics in honey bees, but peripheral cells and organs also affect animal brain and behavior. The fat body, for example, produces yolk proteins and peptides that are essential for insect egg development, it stores nutrients that fuel oogenesis and reproductive activity, it partakes in nutrient sensing, and it communicates nutrient status to the brain (31). These peripheral processes are critical to reproduction, and can be specifically targeted by intra-abdominal dsRNA because the resulting RNAi response will not suppress target genes in other tissues. RNAi-mediated gene knockdown in honey bees, in other words, provides unique opportunities for studying the roles of a peripheral (non-neural) tissue in the `remote control' of behavior.

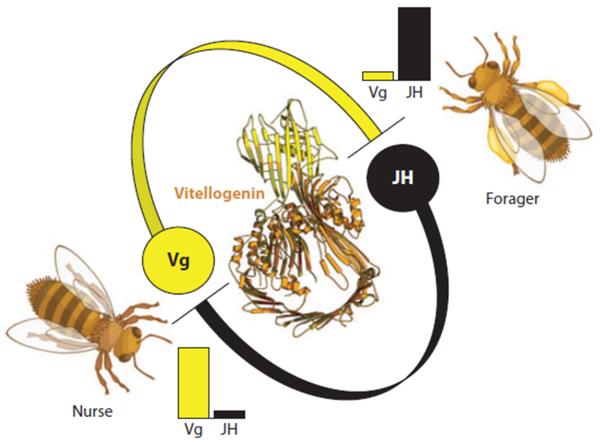

6.2.1 Vitellogenin

Knockdown of the vitellogenin gene provided the first functional genetic evidence for a role of fat body cells in regulation of social behavior (4; 36; 62). This role was proposed several years earlier by a theoretical model where the Vg protein suppressed an endocrine factor, juvenile hormone (JH), that was believed to be central to foraging behavior. Vg and JH acted together in a feedback-loop to control the timing of foraging onset in workers: High Vg levels suppressed JH and foraging behavior while high JH levels suppressed Vg and nursing behavior (Figure 2). RNAi experiments confirmed that JH increased when vitellogenin was suppressed (36), and that vitellogenin knockdown workers foraged precociously (59; 62). The vitellogenin knockdowns, however, also biased their foraging efforts toward nectar (62). This result established that a yolk precursor gene also affected the foraging preference of honey bee workers.

Figure 2.

The honeybee vitellogenin (Vg) protein (structural model in center) suppresses juvenile hormone (JH) and forager behavior in worker bees. Nurse bees are high in Vg and low in JH. Nurses use Vg to produce proteinaceous jelly that is fed to larvae.

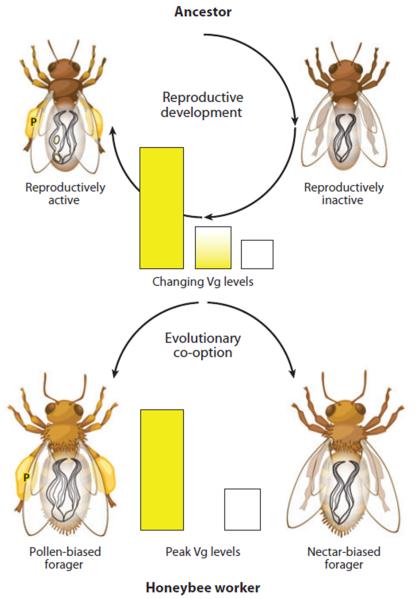

The effect of vitellogenin on the foraging preference of worker bees was explained by a theoretical framework of the reproductive ground plan hypothesis (RGPH). In solitary ancestors of honey bees, high vitellogenin levels were connected to pollen feeding that fueled vitellogenesis and pollen hoarding that provided provisions for the growing larvae. The gene regulatory network that ensured that vitellogenin production and pollen hoarding was linked became co-opted during social evolution (Figure 3). Expression of vitellogenin, thereby, biases honey bee workers toward pollen foraging, while suppression of vitellogenin by RNAi results in a bias toward nectar. Nectar is consumed by many insects also during non-reproductive phases of their life cycle.

Figure 3.

Female ancestors of honeybees went through a phase of reproductive inactivity with low vitellogenin (Vg) levels and a phase of reproductive activity with high Vg, vitellogenesis, and pollen hoarding. Pollen hoarding differs from pollen consumption. In hoarding, pollen is collected and stored in a nest as a protein source for larval development. Similarly, high vitellogenin gene expression is linked to pollen hoarding in honeybees.

The connection between the expression level of vitellogenin and worker foraging bias was also confirmed in the high and low pollen-hoarding strains. Like vitellogenin gene knockdowns, low pollen hoarding strain bees have low vitellogenin levels and bias foraging toward nectar, while high pollen hoarding strain bees have high vitellogenin levels and bias foraging toward pollen (3). The strains' vitellogenin expression differences are most pronounced during the first 15 days of life, but are also detectible in foragers (K. Ihle, R. Page, G.V. Amdam, unpublished data). Similarly, RNAi-mediated gene knockdown reduces vitellogenin during the nurse stage as well as the forager stage of workers (K. Ihle, R. Page, G.V. Amdam, unpublished data). The functional genetic data and the results from pollen hoarding strains, therefore, do not resolve whether the influence of Vg on foraging bias takes place in foragers, or whether it requires that Vg is consistently low during worker maturation.

The cumulative data on vitellogenin demonstrate that a reproductive gene affects complex social behavior in worker honey bees by affecting the onset of foraging and foraging bias. Both wild-type (unselected) and high pollen-hoarding strain worker bees respond to vitellogenin down-regulation with precocious foraging and nectar collection. Low pollen hoarding strain bees, on the other hand, show no phenotypic response to vitellogenin RNAi: they do not forage precociously, and they do not collect more nectar (46). In accordance with this `null' response, low strain bees also lack the JH increase that is induced by vitellogenin downregulation (2). This `null mutant' genotype may, in combination with high strain and wild type bees, provide unique opportunities to study the vitellogenin-JH feedback loop, as it appears to have been at least partly disabled by colony-level selection for low levels of pollen hoarding.

6.2.2 Target of rapamycin (TOR), ultraspiracle (usp)

TOR is a nutrient sensing molecular machine that responds to amino acids (64). Insect Vg levels are sensitive to protein availability (14; 18), and RNAi-mediated suppression of TOR reduces vitellogenin expression in honey bees and mosquitoes (81). Vitellogenin RNAi, moreover, does not affect TOR, therefore, TOR is upstream of vitellogenin. TOR signaling is central to reproduction in many insects and can affect JH levels (58; 60). Thus, TOR can provide another connection between reproductive gene networks and worker honey bee behavior. Experiments with the drug rapamycin, a competitive inhibitor of TOR signaling, suggest that TOR may indeed influence age at foraging onset (9). However, the studies were not conclusive. Foraging onset was both accelerated and retarded by rapamycin. Interactions between TOR signaling, other nutrient sensing pathways, and environmental factors may have explained these variable results (9), but more research is clearly needed to validate the connections.

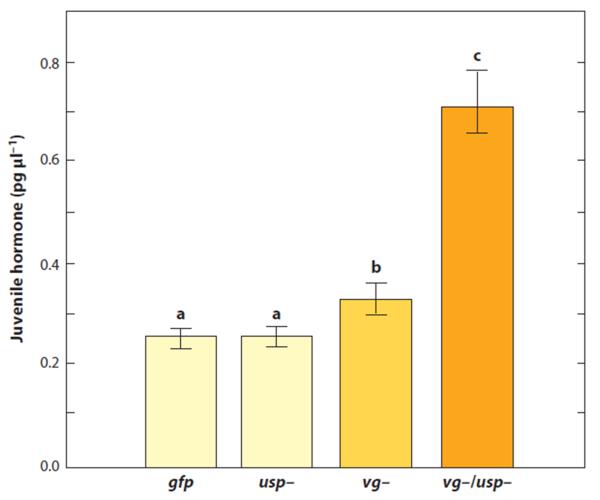

Usp is an ecdysteroid receptor and putative JH receptor/response element in insects that functions in development, growth, and reproduction (40). In combination with vitellogenin RNAi, RNAi-mediated knockdown of usp in honey bees results in highly elevated JH levels, an increase in gustatory responsiveness, reduced starvation resistance, and mobilization of sugars (trehalose and glucose) to the hemolymph (Y. Wang, G.V. Amdam, unpublished data). Ecdysteroid signaling via USP is believed to have little, if any role in the behavioral regulation of eusocial insects since ecdysteroid levels are very low in the adults (37). The combined effect of vitellogenin and usp RNAi may instead be due to a compensatory increase in hormone (i.e., JH, released by vitellogenin RNAi) that is often observed in mutants with deficient receptors. JH, moreover, does not increase when usp is suppressed in bees with normal Vg levels, supporting the hypothesis that it is vitellogenin that controls JH (Figure 4). The effects of vitellogenin and usp `double knockdown' have not been tested for behavior other than gustatory responsiveness, which is a predictor of foraging bias (Table 2). Future experiments should test the Vg/usp connection to foraging preference as well as age at onset of foraging.

Figure 4.

Juvenile hormone (JH) is increased by vitellogenin gene knockdown (vg−) relative to controls (gfp) and ultraspiracle knockdowns (usp−). JH levels in the blood increase more than twofold when vg and usp are suppressed together (vg−/usp−). Bars with different letters (a, b, c) are statistically different (P < 0.05).

6.2.3 Insulin receptor substrate (IRS) and other insulin-like signaling genes

An overabundance of IIS genes in the mapped pollen hoarding QTL suggested that this signaling network was affected by selection and is influencing behavior associated with the pollen hoarding syndrome. The insulin/insulin signaling system can be essential to insect egg development (16) but more generally it guides resource allocation to reproduction during times of surplus and to somatic maintenance during times of famine (108). IRS is a candidate gene for pln4 and encodes the substrate protein that communicates signals via the insulin receptor, and, therefore, a central gene in the cascade. IRS, however, provides a substrate for other receptors too, including the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Effects of IRS downregulation in honey bees may therefore not be exclusively due to changes in insulin signaling (60).

RNAi-mediated suppression of fat body IRS expression was performed in high and low pollen hoarding strain bees (118). In contrast to vitellogenin RNAi, which does not affect low strain workers, both genotypes responded with reduced nectar collection coupled in high strain knockdowns with an increase in pollen collection. Also unlike vitellogenin RNAi, the knockdown of IRS did not affect gustatory responsiveness or the vitellogenin mRNA level (118). An experiment on honey bee larvae also suggests that IRS downregulation can suppress JH (60) although this result is not validated in adult bees. These studies demonstrate an influence of IRS on worker behavior that appears to be at least partly independent of the control circuit of vitellogenin.

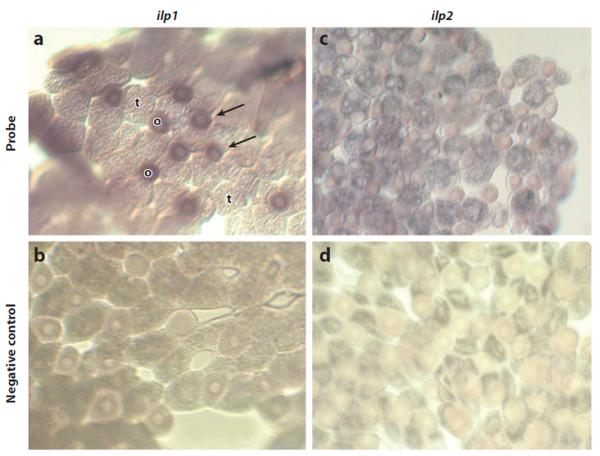

The honey bee fat body also expresses genes for two putative ligands of the insulin receptor, insulin peptide 1 and 2 (ilp1, ilp2). Secretion of insulin peptides from the brain is heavily studied in Drosophila, and this mechanism has been linked to regulation of reproduction and aging (30; 31). Less is known about functions of insulin peptides that are produced by peripheral tissues. In honey bees, ilp1 expression is confined to oenocytes, while ilp2 is expressed in both oenocytes and trophocytes (Figure 5). Thus, it should be possible to test the role of ilp2 in behavior.

Figure 5.

Insulin peptide (ilp) mRNA in honeybee worker fat-body cells stained by in situ hybridization. (a) ilpl is expressed in oenocytes (o), whereas (c) ilp2 is expressed in both oenocyte and trophocyte (t) cells. (b,d) Negative controls. From Reference 62.

7. SUMMARY

Two-way colony level selection on a single social trait, the amount of pollen stored in the comb, resulted in changes at different levels of biological organization constituting a complex phenotypic architecture that we call the pollen hoarding syndrome. Genetic mapping has demonstrated that the phenotypic architecture is derived from a complex epistatic and pleiotropic genetic network with effects on the reproductive regulation of honey bees. Honey bee sequence data of mapped quantitative trait loci reveal candidate genes that are differentially expressed in bees from the artificially selected strains and between wild-type bees that vary in phenotypes that define the pollen-hoarding syndrome. Gene knockdown studies of candidate genes, using RNA interference, confirm the effects of some of the candidate genes on behavior and other elements of the reproductive regulatory network and signaling networks closely associated with reproduction and development. Selection at the colony level for a social trait also left its signature on the hormonal control of ovary development that takes place in worker larvae. The work presented here represents the only detailed study of the genetics and developmental evolution of complex social organization.

Table 4.

Mapped QTL for pollen hoarding, sucrose responsiveness, foraging behavior, age of foraging onset, and worker ovary size.

| QTL (chromonsome:Mb) Trait | Map Population | Effect and interactions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| pln1 (13:3.5) | |||

| Pollen hoarding | HBC | direct | (45) |

| Pollen load size | HBC | direct x pln2 x pln3 | (45)(92) |

| Nectar load size | HBC | direct | (45) |

| Pollen proportion | LBC | x pln3 x pln2 x pln3 x pln4 | (92) |

| Nectar concentration | LBC | x pln2 x pln3 x pln4 | (92) |

| Sucrose responsiveness | HBC, LBC, HXL hybrid males | direct | (85) |

| Age of first foraging | HBC, LBC | direct x pln3 x pln2 x pln3 | (90) |

| Worker ovary size | ABC, HBC | direct | (34) (48) |

| pln2 (1:16.5) | |||

| Pollen hoarding | HBC, EBC | direct | (45) (69) |

| Pollen load size | HBC | direct x pln4 x plnl x pln3 x pln3 x pln4 | (45; 69) (92) |

| Nectar load size | HBC | direct x pln4 | (45) (92) |

| Pollen proportion | HBC, LBC | direct x pln4 x plnl x pln3 x pln4 | (92) |

| Nectar concentration | HBC, LBC | direct x plnl x pln3 x pln4 | (45) (92) |

| Sucrose responsiveness | HBC | x pln3 | (85) |

| Age of first foraging | LBC | x plnl x pln3 | (90) |

| Worker ovary size (HBC) | HBC | direct | (116) |

| Worker ovary size | ABC | direct | (34) |

| pln3 (1:9.2) | |||

| Pollen hoarding | HBC | direct | (69) |

| Nectar load size | HBC | direct | (69) |

| Pollen load size | HBC | direct x plnl x pln2 x pln2 x pln4 | (69) (92) |

| Pollen proportion | LBC | x pln1 x plnl x pln2 x pln4 | (92) |

| Nectar concentration | HBC, LBC | direct x pln4 x plnl x pln2 x pln4 | (69) (92) |

| Sucrose responsiveness | HBC, LBC | x pln2 x pln4 | (85) |

| Age of first foraging | LBC | x plnl x plnl x pln2 | (90) |

| Worker ovary size | HBC | direct | (116) |

| JH response to Vg-RNAi | HBC | direct | (48) |

| pln4 (13:9.0) | |||

| Nectar load size | HBC | x pln2 | (92) |

| Pollen load size | HBC | xpln2 x pln2 x pln3 | (92) |

| Pollen proportion | HBC, LBC | direct x pln2 x plnl x pln2 x pln3 | (92) |

| Nectar concentration | HBC, LBC | direct x pln3 x plnl x pln2 x pln3 | (92) |

| Sucrose responsiveness | HBC, LBC | direct x pln3 | (85) |

| Worker ovary size | HBC | direct | (48) |

| aff2 (11:13.1) | |||

| Age of first foraging | HBC | direct | (84; 90) |

| Worker ovary size | ABC | direct | (34) |

| aff3 (4:9.1) | |||

| Age of first foraging | LBC | direct | (84; 90) |

| aff4 (5:8.8) | |||

| Age of first foraging | LBC | direct | (84; 90) |

| Worker ovary size | ABC | direct | (34) |

| perl (??) | |||

| Sucrose responsiveness | LBC | direct | (85) |

| wosl (3:13.1) | |||

| Worker ovary size | HBC | direct | (48; 89) |

| JH response to Vg-RNAi | HBC | direct | (48) |

| wos2 (2:10.7) | |||

| Worker ovary size | HBC | direct | (48; 89) |

| JH response to Vg-RNAi | HBC | direct | (48) |

| wos3 (4:1.8) | |||

| Worker ovary size | LBC LBC |

direct | (48; 89) |

| wos4 (11:10.7) | |||

| Worker ovary size | ABC HBC |

direct | (34) (48) |

| wos5 (6:14.2) | |||

| Worker ovary size | ABC HBC |

direct | (34) (48) |

Crosses for map populations are: HBC = High Strain Backcross, LBC = Low Strain Backcross, HXL hybrid cross, ABC = Africanized Backcross; EBC = European Backcross. For each QTL effects are shown as direct or in interaction with other QTL.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank K.E. Ihle and Y. Wang for assistance with the figures. This work spans more than 20 years and was generously supported by the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the United States Department of Agriculture, and the Almond Board of California. Specific thanks goes to the PEW Charitable Trust (to GVA.), the Norwegian Research Council (180504, 185306, and 191699 to GVA), the National Institute on Aging (PO1AG22500 to REP and GVA), the National Science Foundation (#0615502 to GVA and OR, and #0926288 to OR), and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, US Department of Agriculture (#2010-65104-20533 to OR).

9. LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Amdam GV, Csondes A, Fondrk MK, Page RE. Complex social behaviour derived from maternal reproductive traits. Nature. 2006;439:76–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amdam GV, Nilsen KA, Norberg K, Fondrk MK, Hartfelder K. Variation in endocrine signaling underlies variation in social life history. Am. Nat. 2007;170:37–46. doi: 10.1086/518183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amdam GV, Norberg K, Fondrk MK, Page RE., Jr. Reproductive ground plan may mediate colony-level selection effects on individual foraging behavior in honey bees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:11350–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403073101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amdam GV, Norberg K, Page RE, Erber J, Scheiner R. Downregulation of vitellogenin gene activity increases the gustatory responsiveness of honey bee workers (Apis mellifera) Behav. Brain Res. 2006;169:201–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amdam GV, Omholt SW. The hive bee to forager transition in honeybee colonies: the double repressor hypothesis. J. Theor. Biol. 2003;223:451–64. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(03)00121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amdam GV, Page RE. The developmental genetics and physiology of honeybee societies. Anim. Behav. 2010;79:973–80. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amdam GV, Page RE, Fondrk MK, Brent CS. Hormone response to bidirectional selection on social behavior. Evol Dev. 2010;12:428–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2010.00429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amdam GV, Simões ZLP, Guidugli KR, Norberg K, Omholt SW. Disruption of vitellogenin gene function in adult honeybees by intra-abdominal injection of double-stranded RNA. BMC Biotechnol. 2003;3:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ament SA, Corona M, Pollock HS, Robinson GE. Insulin signaling is involved in the regulation of worker division of labor in honey bee colonies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:4226–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800630105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baird NA, Etter PD, Atwood TS, Currey MC, Shiver AL, et al. Rapid SNP discovery and genetic mapping using sequenced RAD markers. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beshers SN, Fewell JH. Models of division of labor in social insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2001;46:413–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.46.1.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beye M, Gattermeier I, Hasselmann M, Gempe T, Schioett M, et al. Exceptionally high levels of recombination across the honey bee genome. Genome Res. 2006;16:1339–44. doi: 10.1101/gr.5680406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beye M, Hasselmann M, Fondrk MK, Page RE, Omholt SW. The gene csd is the primary signal for sexual development in the honeybee and encodes an SR-type protein. Cell. 2003;114:419–29. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bitondi MMG, Simões ZLP. The relationship between level of pollen in the diet, vitellogenin and juvenile hormone titres in Africanized Apis mellifera workers. J. Apic. Res. 1996;35:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brillet C, Robinson GE, Bues R, LeConte Y. Racial differences in division of labor in colonies of the honey bee (Apis mellifera) Ethology. 2002;108:115–26. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown MR, Clark KD, Gulia M, Zhao Z, Garczynski SF, et al. An insulin-like peptide regulates egg maturation and metabolism in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5716–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800478105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calderone NW, Johnson BR. The within-nest behaviour of honeybee pollen foragers in colonies with a high or low need for pollen. Anim. Behav. 2002;63:749–58. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clements AN. The Biology of Mosquitoes: Volume 1: Development, Nutrition and Reproduction. Chapman and Hall; New York: 1992. p. 536. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Consortium THG. Insights into social insects from the genome of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Nature. 2006;443:931–49. doi: 10.1038/nature05260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Debelle JS, Hilliker AJ, Sokolowski MB. Genetic localization of foraging (for) - a major gene for larval behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1989;123:157–63. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dickson BJ. Wired for sex: the neurobiology of Drosophila mating decisions. Science. 2008;322:904–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1159276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dreller C. Division of labor between scouts and recruits: Genetic influence and mechanisms. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1998;43:191–6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dreller C, Page RE, Fondrk MK. Regulation of pollen foraging in honeybee colonies: effects of young brood, stored pollen, and empty space. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1999;45:227–33. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dreller C, Tarpy D. Perception of the pollen need by foragers in a honeybee colony. Anim. Behav. 2002;59:91–6. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dzierzon J. Gutachten über die von Herrn Direktor Stöhr im ersten und zweiten Kapitel des General-Gutachtens aufgestellten Fragen. Eichstädter Bienenzeitung. 1845;1109–113:119–21. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erber J, Hoormann J, Scheiner R. Phototactic behaviour correlates with gustatory responsiveness in honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) Behavioural Brain Research. 2006;174:174–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fewell JH, Page RE. Genotypic variation in foraging responses to environmental stimuli by honey bees, Apis mellifera. Experientia. 1993;49:1106–12. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fewell JH, Page RE. Colony-level selection effects on individual and colony foraging task performance in honeybees, Apis mellifera L. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2000;48:173–81. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fewell JH, Winston ML. Colony state and regulation of pollen foraging in the honey-bee, Apis mellifera L. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1992;30:387–93. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flatt T, Min KJ, D'Alterio C, Villa-Cuesta E, Cumbers J, et al. Drosophila germ-line modulation of insulin signaling and lifespan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:6368–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709128105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geminard C, Rulifson EJ, Leopold P. Remote control of insulin secretion by fat cells in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 2009;10:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gempe T, Beye M. Function and evolution of sex determination mechanisms, genes and pathways in insects. Bioessays. 2011;33:52–60. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordon DM, Barthell JF, Page RE, Fondrk MK, Thorp RW. Colony performance of selected honey-bee (Hymenoptera, Apidae) strains used for Alfalfa pollination. J Econ Entomol. 1995;88:51–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graham AM, Munday MD, Kaftanoglu O, Page RE, Jr., Amdam GV, Rueppell O. Support for the reproductive ground plan hypothesis of social evolution and major QTL for ovary traits of Africanized worker honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grozinger CM, Sharabash NM, Whitfield CW, Robinson GE. Pheromone-mediated gene expression in the honey bee brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:14519–25. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335884100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guidugli KR, Nascimento AM, Amdam GV, Barchuk AR, Omholt SW, et al. Vitellogenin regulates hormonal dynamics in the worker caste of a eusocial insect. FEBS Letters. 2005;579:4961–5. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hartfelder K, Bitondi MMG, Santana WC, Simões ZLP. Ecdysteroid titer and reproduction in queens and workers of the honey bee and of a stingless bee: loss of ecdysteroid function at increasing levels of sociality? Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002;32:211–6. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(01)00100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartfelder K, Engels W. Social insect polymorphism: Hormonal regulation of plasticity in development and reproduction in the honeybee. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. 1998;40:45–77. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60364-6. 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hellmich RL, Kulincevic JM, Rothenbuhler WC. Selection for high and low pollen-hoarding honey bees. J Hered. 1985;76:155–8. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hult EF, Tobe SS, Chang BS. Molecular evolution of ultraspiracle protein (USP/RXR) in insects. Plos One. 2011;6:e23416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Humann FC, Hartfelder K. Representational Difference Analysis (RDA) reveals differential expression of conserved as well as novel genes during caste-specific development of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) ovary. Insect Biochem Molec. 2011;41:602–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Humphries MA, Fondrk MK, Page RE. Locomotion and the pollen hoarding behavioral syndrome of the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) J Comp Physiol A. 2005;191:669–74. doi: 10.1007/s00359-005-0624-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Humphries MA, Muller U, Fondrk MK, Page RE. PKA and PKC content in the honey bee central brain differs in genotypic strains with distinct foraging behavior. J Comp Physiol A. 2003;189:555–62. doi: 10.1007/s00359-003-0433-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hunt GJ, Amdam GV, Schlipalius D, Emore C, Sardesai N, et al. Behavioral genomics of honeybee foraging and nest defense. Naturwissenschaften. 2007;94:247–67. doi: 10.1007/s00114-006-0183-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hunt GJ, Page RE, Jr., Fondrk MK, Dullum CJ. Major quantitative trait loci affecting honey bee foraging behavior. Genetics. 1995;141:1537–45. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.4.1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ihle K, Fondrk MK, Page RE, Amdam GV. Proc. GRC Genes and Behavior. Italy: 2008. Gene network perturbation in response to vitellogenin (vg) knockdown provides insight into endocrine feedback regulation of honey bee (Apis mellifera) behavioral ontogeny. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ihle KE, Page RE, Frederick K, Fondrk MK, Amdam GV. Genotype effect on regulation of behaviour by vitellogenin supports reproductive origin of honeybee foraging bias. Anim. Behav. 2010;79:1001–6. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ihle KE, Rueppell O, Page RE, Amdam GV. QTL for ovary size and juvenile hormone response to Vg-RNAi knockdown. unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iltis H. Life of Mendel. W. W. Norton; New York: 1924. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jarosch A, Moritz RF. Systemic RNA-interference in the honeybee Apis mellifera: tissue dependent uptake of fluorescent siRNA after intra-abdominal application observed by laser-scanning microscopy. J Insect Physiol. 2011;57:851–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jarosch A, Stolle E, Crewe RM, Moritz RF. Alternative splicing of a single transcription factor drives selfish reproductive behavior in honeybee workers (Apis mellifera) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:15282–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109343108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kuwabara M. Bildung des bedingten Reflexes vom Pavlov Typus bei der Honigbiene (Apis mellifica) J. Fac. Sci. Hokkaido Univ. Zool. 1957;13:458–64. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laidlaw HH. Instrumental insemination of honeybee queens: its origin and development. Bee World. 1987;68:17–36. 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Latshaw JS. How honey bees learn to ignore irrelevant stimuli: are learning and foraging genotypes part of the same behavioral syndrome? Arizona State University; Tempe: 2008. p. 129. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Linksvayer TA, Fondrk MK, Page RE. Honeybee social regulatory networks are shaped by colony-level selection. Am. Nat. 2009;173:E99–E107. doi: 10.1086/596527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Linksvayer TA, Kaftanoglu O, Akyol E, Blatch S, Amdam GV, Page RE. Larval and nurse worker control of developmental plasticity and the evolution of honey bee queen-worker dimorphism. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2011;24:1939–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Linksvayer TA, Rueppell O, Siegel A, Kaftanoglu O, Page RE, Amdam GV. The genetic basis of transgressive ovary size in honey bee workers. Genetics. 2009;183:693–707. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.105452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maestro JL, Cobo J, Belles X. Target of rapamycin (TOR) mediates the transduction of nutritional signals into juvenile hormone production. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5506–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marco Antonio DS, Guidugli-Lazzarini KR, Nascimento AM, Simões ZLP, Hartfelder K. RNAi-mediated silencing of vitellogenin gene function turns honeybee (Apis mellifera) workers into extremely precocious foragers. Naturwissenschaften. 2008;95:953–61. doi: 10.1007/s00114-008-0413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mutti NS, Dolezal AG, Wolschin F, Mutti JS, Gill KS, Amdam GV. IRS and TOR nutrient-signaling pathways act via juvenile hormone to influence honey bee caste fate. J Exp Biol. 2011;214:3977–84. doi: 10.1242/jeb.061499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nachtsheim H. Cytologische Studien über die Geschlechtsbestimmung bei der Honigbiene (Apis mellifica L.) Archiv für Zellforschung. 1913;11:169–241. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nelson CM, Ihle K, Amdam GV, Fondrk MK, Page RE. The gene vitellogenin has multiple coordinating effects on social organization. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:673–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nilsen KA, Ihle KE, Frederick K, Fondrk MK, Smedal B, et al. Insulin-like peptide genes in honey bee fat body respond differently to manipulation of social behavioral physiology. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2011;214:1488–97. doi: 10.1242/jeb.050393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oldham S, Hafen E. Insulin/IGF and target of rapamycin signaling: a TOR de force in growth control. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Orel V. Gregor Mendel the First Geneticist. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Page RE, Erber J, Fondrk MK. The effect of genotype on response thresholds to sucrose and foraging behavior of honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) Journal of Comparative Physiology A - Sensory, Neural and Behavioral Physiology. 1998;182:489–500. doi: 10.1007/s003590050196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Page RE, Erickson EH. Reproduction by worker honey bees (Apis mellifera L) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1988;23:117–26. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Page RE, Fondrk MK. The effects of colony level selection on the social organization of honey bee (Apis mellifera L) colonies - colony level components of pollen hoarding. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1995;36:135–44. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Page RE, Fondrk MK, Hunt GJ, Guzman-Novoa E, Humphries MA, et al. Genetic dissection of honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) foraging behavior. J Hered. 2000;91:474–9. doi: 10.1093/jhered/91.6.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Page RE, Laidlaw HH. Full sisters and super sisters: a terminological paradigm. Anim. Behav. 1988;36:944–5. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Page RE, Laidlaw HH. The Hive and Honey Bee:235–67. Dadant and Son; Hamilton, IL: 1992. Honey bee genetics and breeding. Number of 235–67 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Page RE, Waddington KD, Hunt GJ, Fondrk MK. Genetic determinants of honey bee foraging behaviour. Anim. Behav. 1995;50:1617–25. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pankiw T. Directional change in a suite of foraging behaviors in tropical and temperate evolved honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2003;54:458–64. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pankiw T, Nelson M, Page RE, Fondrk MK. The communal crop: modulation of sucrose response thresholds of pre-foraging honey bees with incoming nectar quality. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2004;55:286–92. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pankiw T, Page RE. The effect of genotype, age, sex, and caste on response thresholds to sucrose and foraging behavior of honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 1999;185:207–13. doi: 10.1007/s003590050379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pankiw T, Page RE. Response thresholds to sucrose predict foraging division of labor in honeybees. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2000;47:265–7. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pankiw T, Page RE. Genotype and colony environment affect honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) development and foraging behavior. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2001;51:87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pankiw T, Page RE, Fondrk MK. Brood pheromone stimulates pollen foraging in honey bees (Apis mellifera) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1998;44:193–8. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pankiw T, Tarpy DR, Page RE. Genotype and rearing environment affect honeybee perception and foraging behaviour. Anim. Behav. 2002;64:663–72. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pankiw T, Waddington KD, Page RE. Modulation of sucrose response thresholds in honey bees (Apis mellifera L.): influence of genotype, feeding, and foraging experience. Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 2001;187:293–301. doi: 10.1007/s003590100201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Patel A, Fondrk MK, Kaftanoglu O, Emore C, Hunt G, Amdam GV. The making of a queen: TOR pathway governs diphenic caste development. Plos One. 2007;6:e509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rhea JM, Wegener C, Bender M. The proprotein convertase encoded by amontillado (amon) is required in Drosophila corpora cardiaca endocrine cells producing the glucose regulatory hormone AKH. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rotjan RD, Calderone NW, Seeley TD. How a honey bee colony mustered additional labor for the task of pollen foraging. Apidologie. 2002;33:367–73. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rueppell O. Characterization of quantitative trait loci for the age of first foraging in honey bee workers. Behavior Genetics. 2009;39:541–53. doi: 10.1007/s10519-009-9278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rueppell O, Chandra SBC, Pankiw T, Fondrk MK, Beye M, et al. The genetic architecture of sucrose responsiveness in the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) Genetics. 2006;172:243–51. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.046490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rueppell O, Christine S, Mulcrone C, Groves L. Aging without functional senescence in honey bee workers. Current Biology. 2007;17:R274–R5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rueppell O, Fondrk MK, Page RE. Male maturation response to selection of the pollen-hoarding syndrome in honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) Animal Behavior. 2006;71:227–34. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rueppell O, Hunggims E, Tingek S. Association between larger ovaries and pollen foraging in queenless Apis cerana workers supports the reproductive ground - plan hypothesis of social evolution. Journal of Insect Behavior. 2008;21:317–21. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rueppell O, Metheny JD, Linksvayer TA, Fondrk MK, Page RE, Jr, Amdam GV. Genetic architecture of ovary size and asymmetry in European honeybee workers. Heredity. 2011;106:894–903. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2010.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rueppell O, Pankiw T, Nielson DI, Fondrk MK, Beye M, Page RE., Jr The genetic architecture of the behavioral ontogeny of foraging in honey bee workers. Genetics. 2004;167:1767–79. doi: 10.1534/genetics.103.021949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rueppell O, Phaincharoen M, Kuster R, Tingek S. Cross-species correlation between queen mating numbers and worker ovary sizes suggests kin conflict may influence ovary size evolution in honeybees. Naturwissenschaften. 2011;98:795–9. doi: 10.1007/s00114-011-0822-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rüppell O, Pankiw T, Page RE., Jr Pleiotropy, epistasis and new QTL: the genetic architecture of honey bee foraging behavior. J Hered. 2004;95:481–91. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esh072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sasaki K, Harano KI. Potential effects of tyramine on the transition to reproductive workers in honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) Physiol Entomol. 2007;32:194–8. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sasaki K, Nagao T. Brain tyramine and reproductive states of workers in honeybees. Journal of Insect Physiology. 2002;48:1075–85. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(02)00200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Scheiner R. Responsiveness to sucrose and habituation of the proboscis extension response in honey bees. J Comp Physiol A. 2004;190:727–33. doi: 10.1007/s00359-004-0531-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Scheiner R, Erber J, Page RE., Jr Tactile learning and the individual evalution of the reward in honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 1999;185:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s003590050360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Scheiner R, Page RE, Erber J. The effects of genotype, foraging role, and sucrose responsiveness on the tactile learning performance of honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2001;76:138–50. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2000.3996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Scheiner R, Page RE, Erber J. Responsiveness to sucrose affects tactile and olfactory learning in preforaging honey bees of two genetic strains. Behavioural Brain Research. 2001;120:67–73. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Scheiner R, Pluckhahn S, Oney B, Blenau W, Erber J. Behavioural pharmacology of octopamine, tyramine and dopamine in honey bees. Behavioural Brain Research. 2002;136:545–53. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schmidt Capella IC, Hartfelder K. Juvenile hormone effect on DNA synthesis and apoptosis in caste-specific differentiation of the larval honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) ovary. Journal of Insect Physiology. 1998;44:385–91. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(98)00027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schmidt Capella IC, Hartfelder K. Juvenile-hormone-dependent interaction of actin and spectrin is crucial for polymorphic differentiation of the larval honey bee ovary. Cell and Tissue Research. 2002;307:265–72. doi: 10.1007/s00441-001-0490-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Schulz DJ, Pankiw T, Fondrk MK, Robinson GE, Page RE. Comparisons of juvenile hormone hemolymph and octopamine brain titers in honey bees (Hymenoptera : Apidae) selected for high and low pollen hoarding. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2004;97:1313–9. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schulz DJ, Robinson GE. Octopamine influences division of labor in honey bee colonies. Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 2001;187:53–61. doi: 10.1007/s003590000177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Seeley D. The Wisdom of the Hive: The Social Physiology of Honey Bee Colonies. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1995. pp. 295–xiv. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Siegel AJ, Kaftanoglu O, Fondrk MK, Smith NR, Page RE. Ovarian regulation of foraging division of labour in africanized backcross honey bees. Anim. Behav. 2012 Online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.12.009.

- 106.Tarpy DR, Nielsen R, Nielsen DI. A scientific note on the revised estimates of effective paternity frequency in Apis. Insectes Sociaux. 2004;51:203–4. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Thompson GJ, Yockey H, Lim J, Oldroyd BP. Experimental manipulation of ovary activation and gene expression in honey bee (Apis mellifera) queens and workers: Testing hypotheses of reproductive regulation. J Exp Zool Part A. 2007;307A:600–10. doi: 10.1002/jez.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Toivonen JM, Partridge L. Endocrine regulation of aging and reproduction in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009;299:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tsuruda JM, Amdam GV, Page RE. Sensory response system of social behavior tied to female reproductive traits. Plos One. 2008;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tsuruda JM, Page RE. The effects of foraging role and genotype on light and sucrose responsiveness in honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) Behavioural Brain Research. 2009;205:132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tsuruda JM, Page RE. The effects of young brood on the foraging behavior of two strains of honey bees (Apis mellifera) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2009;64:161–7. doi: 10.1007/s00265-009-0833-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vaughan DM, Calderone NW. Assessment of pollen stores by foragers in colonies of the honey bee, Apis mellifera L. Insectes Sociaux. 2002;49:23–7. [Google Scholar]

- 113.von Frisch K. The dance language and orientation of bees. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1967. p. 566. [Google Scholar]