Summary

The sigma-1 receptor (Sig-1R), an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperone protein, is an inter-organelle signaling modulator that potentially plays a role in drug-seeking behaviors. However, the brain site of action and underlying cellular mechanisms remain unidentified. We found that cocaine exposure triggers a Sig-1R-dependent upregulation of D-type K+ current in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) that results in neuronal hypoactivity, and thereby enhances behavioral cocaine response. Combining ex vivo and in vitro studies, we demonstrated that this neuroadaptation is caused by a persistent protein-protein association between Sig-1Rs and Kv1.2 channels, a phenomenon that is associated to a redistribution of both proteins from intracellular compartments to the plasma membrane. In conclusion, the dynamic Sig-1R - Kv1.2 complex represents a novel mechanism that shapes neuronal and behavioral response to cocaine. Functional consequences of Sig-1R binding to K+ channels may have implications for other chronic diseases where maladaptive intrinsic plasticity and Sig-1Rs are engaged.

Introduction

The Sigma-1 receptor is a chaperone protein residing at the interface between the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the mitochondrion (Mitochondrion-Associated ER Membrane, MAM) (Hayashi and Su, 2007), that is ubiquitously expressed throughout the brain (Gundlach et al., 1986). Upon ligand stimulation the Sig-1R translocates from the MAM to the ER and plasmalemma (Hayashi and Su, 2003). Acting as an inter-organelle signaling modulator, it regulates a variety of functional proteins (Su et al., 2010) either directly or indirectly through G protein-, as well as protein kinase C (PKC)- and protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent signaling pathways (Maurice and Su, 2009). In addition, in vitro activation of the Sig-1R increases (Soriani et al., 1998) or decreases (Zhang and Cuevas, 2005) neuronal excitability through changes in voltage-gated K+ currents (Kourrich et al., 2012b). Whether these changes occur through G protein-dependent signaling pathways (He et al., 2012; Soriani et al., 1998) remains controversial (Lupardus et al., 2000; Zhang and Cuevas, 2005). To date, only one study has provided clear evidence showing that Sig-1Rs can modulate K+ currents through a direct protein interaction in the central nervous system (CNS) (Aydar et al., 2002).

By increasing voltage-gated K+ currents (Kv), contingent or non-contingent cocaine exposure induces a persistent firing rate depression in the NAc shell medium spiny neurons (MSNs) (Ishikawa et al., 2009; Kourrich and Thomas, 2009; Mu et al., 2010), a brain region involved in reward-processing and motivation (Kelley, 2004). This cocaine-induced neuronal adaptation is sufficient to elicit long-lasting hyper-responsiveness to cocaine, also known as behavioral sensitization (Kourrich et al., 2012a)—a phenotype that is thought to reflect increased rewarding properties of cocaine that may contribute to the development of addictive processes (Robinson and Berridge, 2008). Interestingly, blockade of Sig-1R activity reliably attenuates cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization (Maurice and Su, 2009). However, the underlying cellular mechanisms remain unknown. Because cocaine activates the Sig-1R (Hayashi and Su, 2001), we hypothesize that the Sig-1R is a key link between cocaine exposure and the persistent decrease in NAc shell MSN intrinsic excitability that promotes behavioral sensitization to cocaine.

Here, we identify the Sig-1R as a critical molecular link between cocaine exposure and long-lasting behavioral hyper-sensitivity to cocaine. Knockdown of Sig-1Rs in the NAc medial shell prevented cocaine-induced persistent MSN firing rate depression and attenuated psychomotor responsiveness to cocaine. This cocaine-induced neuroadaptation occurred through Sig-1R-dependent upregulation of a subtype of transient K+ current, the slowly-inactivating D-type K+ current (ID, also called IAs). To this end, Sig-1Rs form complexes with Kv1.2 channels at the plasma membrane. Importantly, we show that such protein-protein associations can undergo enduring experience-dependent plasticity, evidenced here by a cocaine-induced long-lasting increase in protein-protein association between Sig-1Rs and Kv1.2 channels in the NAc shell.

Results

Systemic blockade of Sig-1Rs attenuates behavioral sensitivity to cocaine through modulation of accumbal firing

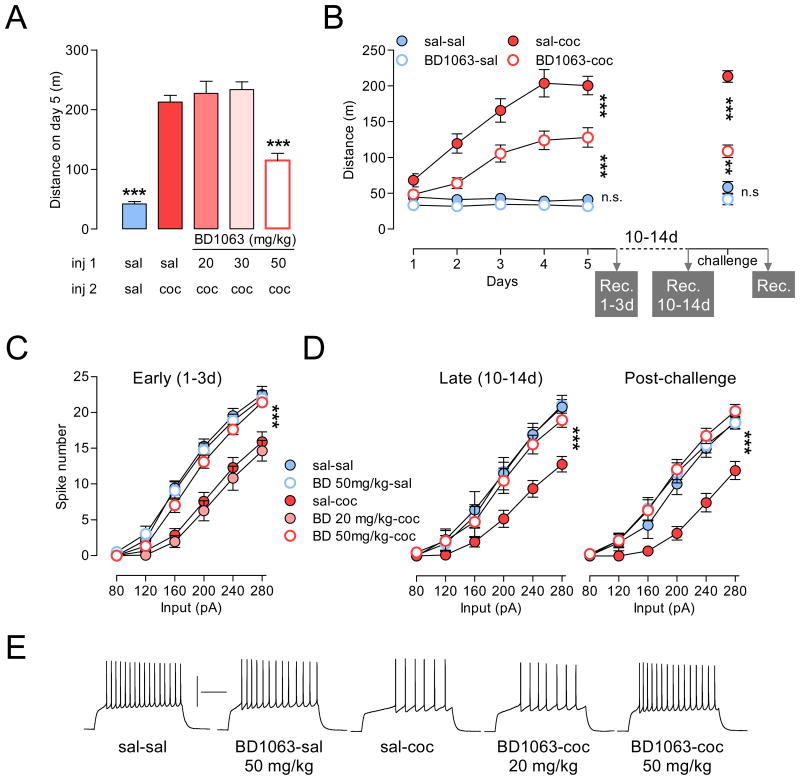

Sig-1R antagonists, agents that prevent Sig-1R translocation, attenuate psychomotor and rewarding effects of cocaine (Maurice and Su, 2009). To investigate the neuroanatomical site of action of Sig-1R antagonists and their functional consequences, we first used a pharmacological approach by systemically administering BD1063, a selective and prototypical Sig-1R antagonist, or BD1047, a Sig-1R antagonist that has less selectivity, however, a 10-fold higher affinity (Ki) (see Experimental Procedures for details) (Matsumoto et al., 1995). After five consecutive once-daily intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of saline ± BD1063 (or BD1047) or cocaine ± BD1063 (or BD1047) (Figure 1A, 1B, S1A), we assessed firing capability of MSNs with current-clamp recordings. Both Sig-1R antagonists abolished cocaine-induced firing rate depression (Figure 1C, S1B); with BD1063 at 50 mg/kg (Figure 1A, B) and BD1047 at 5 mg/kg (Figure S1A), doses that also attenuated psychomotor sensitization. Cocaine-induced firing rate depression in NAc MSNs, however, was preserved at lower doses of BD1063 (Figure 1C; 20 and 30 mg/kg), where animals showed normal cocaine-induced psychomotor sensitization. Further analyses showed that repeated treatment with BD1063 or BD1047 alone did not alter either basal locomotion (Figure 1B, Figure 1SA) or basal firing rate (Figure 1C, Figure 1SB). In summary these data strongly indicate a Sig-1R-dependent mechanism as both antagonists attained similar physiological and behavioral effects despite their different pharmacological properties at the Sig-1R. Because BD1063 exhibits a higher selectivity, we used this compound in all subsequent experiments.

Figure 1. Effects of the Sig1R pharmacological blockade on psychomotor responsiveness to cocaine and accumbal firing are persistent.

(A) Dose-response to i.p. BD1063 (BD), a selective Sig-1R antagonist, on cocaine-induced locomotion. Injections of BD1063 or saline (inj 1) were performed 15 min prior to daily i.p. injections of cocaine (15mg/kg) or saline (inj 2). One-way ANOVA: ***p < 0.0001 different from all groups. (B) Cocaine-induced sensitization of locomotor activity is attenuated by inhibition of the Sig-1R with BD1063 (50 mg/kg) (n = 19-20). Ten to fourteen days after the last injection a subset of animals received a cocaine (10 mg/kg) challenge injection (n = 4-9). Data indicate distance traveled during 30 min following i.p. injection of either saline or cocaine. The x-axis also represents the timeline for current-clamp recordings (Rec.). BD1063 at 50 mg/kg, but not at 20 mg/kg, prevents cocaine-induced firing rate depression when recorded at an early withdrawal time point (C, 1-3 days post-treatment), following 10-14 days of abstinence (D, left), and 24h after cocaine challenge injection (D, right). In C: N = 14-20 cells per group; 3-5 mice per group; in D left: N = 7-14 cells per group; 3-5 mice per group. In D right: N = 8-15 cells per group; 3-4 mice per group. (E) Sample traces at 200 pA from all groups shown in (D). Calibration: 200 ms, 50 mV. In panels B, C and D, two-way ANOVA: p < 0.0001; post-hoc tests: ***p < 0.0001; **p < 0.01; n.s: non-significant. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

One hallmark of drug addiction is its persistence despite long periods of drug abstinence, as is cocaine-induced firing rate depression, an adaptation that is induced by both contingent (Mu et al., 2010) and non-contingent administration of cocaine (Ishikawa et al., 2009; Kourrich and Thomas, 2009). Consistent with previous reports, after a two-week period of abstinence from 5 once-daily cocaine injections the firing rate depression was still present; and its rescue by prior treatment with BD1063 was long-lasting as well (Figure 1D, left). Since a single re-exposure to cocaine can trigger relapse in humans and animals (Stewart, 2004), we examined the long-lasting effect of prior treatment with BD1063 on psychomotor responsiveness to cocaine re-exposure. Specifically, if BD1063 during cocaine treatment prevents sensitization mechanisms, the attenuated psychomotor sensitization should persist as well. Indeed, mice pre-treated with BD1063 (BD1063-coc) still exhibited decreased psychomotor activation to a cocaine challenge (Chal, Figure 1B). Furthermore, and as expected by our previous findings (Kourrich and Thomas, 2009), MSN firing rate was not decreased 24 h after a single cocaine injection (Figure 1D, right). These data suggest that effects of Sig-1R blockade during cocaine treatment are long-lasting, both in terms of behavioral effects and intrinsic excitability. A possible explanation for such lasting effects may lie in blockade of functional outcomes that are triggered by cocaine-induced Sig-1R activation, in particular during abstinence or following re-exposure to a single cocaine administration. Altogether, our results indicate that the Sig-1R plays a central role in modulating the responsiveness to cocaine through modulation of accumbal firing capability.

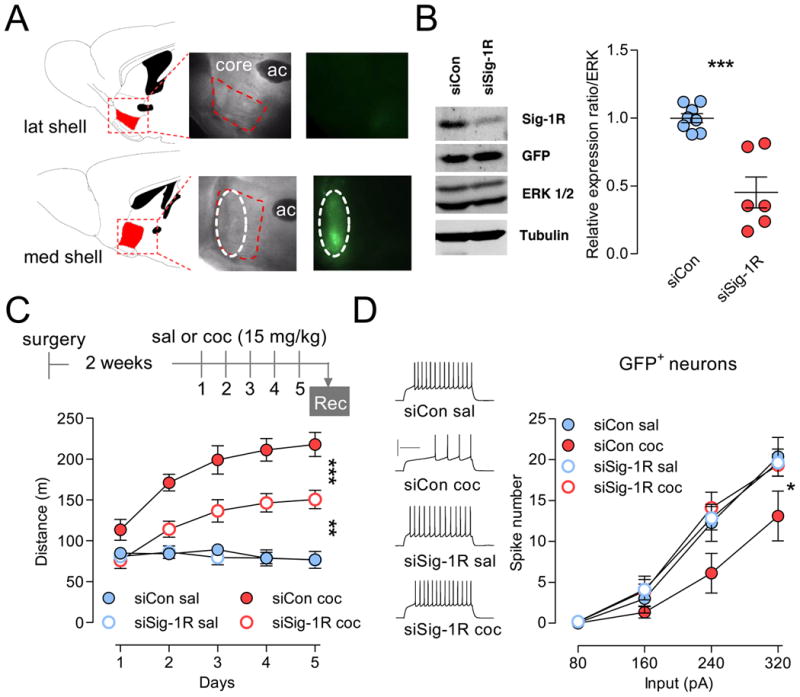

Specific blockade of Sig-1Rs in the NAc shell prevents cocaine-induced behavioral and neuronal adaptations

To increase both regional and molecular specificity we then employed an adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector to knockdown Sig-1R protein expression in the NAc rostro-medial shell (Figure, 2A, S2A). This is the only shell region exclusively associated with purely appetitive behaviors (Reynolds and Berridge, 2002), and is most responsive to psychostimulant drugs (Ikemoto, 2010).

Figure 2. Knockdown of Sig-1R protein expression in the NAc shell attenuates psychomotor responsiveness to cocaine and prevents cocaine-induced firing rate depression.

(A) Sagittal brain sections showing expression of siRNA specifically in the rostro-medial shell (ML: 0.48 mm) and not lateral shell or core (ML: 0.84 mm). Diagrams and coordinates are from Paxinos and Franklin, 2001. (B) Total protein was collected after transduction and analyzed by western blotting. Left, Immunoblot showing decreased Sig-1R proteins expression. Note that GFP expression stays unchanged. Right, ERK-normalized Sig-1R protein expression shows a 50% depletion. However, this percentage is only a representative estimate of actual depletion as variability due to several factors can affect this number, including the volume of NAc shell that has been infused, protein degradation and microdissection-mediated dilution. Each data point represents NAc shell from one animal (n = 7-8). Hash marks indicate group means. Two-tailed Student's t-test: ***p < 0.001. (C) Top, Experimental timeline (rec, recordings). Bottom, siSi-1R attenuates psychomotor activation to chronic cocaine (n = 8-16). Data indicate distance traveled during 30 min following i.p. injection of either saline or cocaine. Two-way ANOVA: ***p < 0.0001. Post-hoc tests: **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001. (D) Left, Sample traces at 240 pA. Right, mean number of spikes for a given magnitude of current injection was decreased in neurons from cocaine-treated animals infused with siCon, but prevented in neurons from animals infused with siSig-1R. Two-way ANOVA: * p < 0.05. Post-hoc tests: siSig-1R coc GFP+ is different from siCon coc and not different from any saline-treated groups. Calibration: 200 ms, 50 mV. N = 6-15 cells per group; 4-7 mice per group. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S2.

Knockdown of Sig-1R protein expression in the rostro-medial shell by ∼50% (Figure 2B, S2B, S2C) attenuated psychomotor activation to cocaine by ∼35% (Figure 2C). When firing capability was assessed in transduced neurons (GFP+ cells, Figure 2D), expression of Sig-1R siRNA normalized cocaine-induced firing rate depression (siSig-1R coc) to control levels (siCon sal). Additionally, AAV transduction itself (siCon or siSig-1R) did not affect basal firing levels when compared to non-transduced control cells (GFP- neurons, Figure S2D).

Taken together these results demonstrate that inhibition of the Sig-1R, either via systemic pharmacological antagonism or Sig-1R knockdown in the NAc rostro-medial shell attenuates psychomotor responsiveness to cocaine and counteracts cocaine-induced firing rate depression.

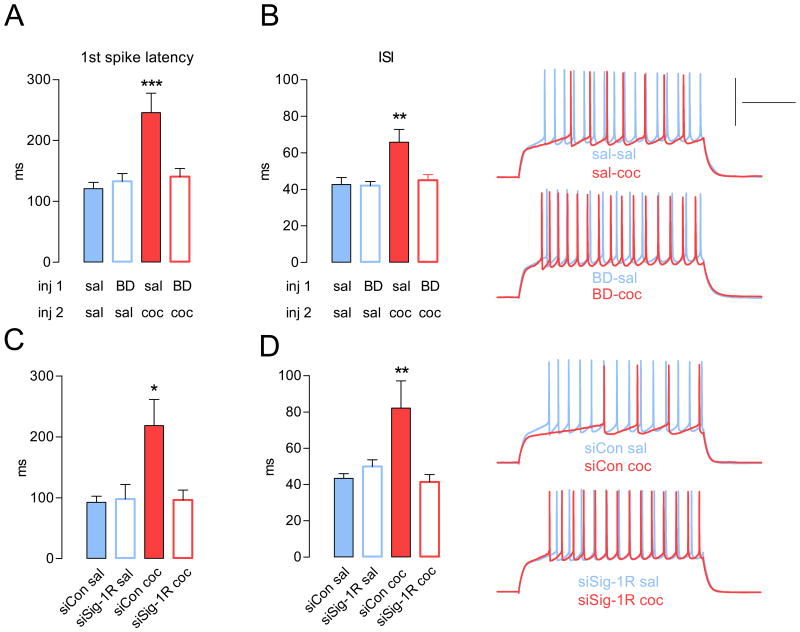

Cocaine-induced NAc shell MSN hypoactivity is triggered through Sig-1R-dependent upregulation of a slowly-inactivating D-type K+ current

Recent studies showed that repeated cocaine administration decreases NAc MSN intrinsic excitability via an increase of K+ conductances (Ishikawa et al., 2009; Kourrich and Thomas, 2009). A first step to identify these associated key K+ currents is to quantify the observed differences in spiking patterns. We analyzed fundamental characteristics of spike trains elicited at a non-saturating current injection that reliably elicits spikes. Spike train analysis revealed that MSNs from mice injected with cocaine showed a longer delay for spike onset (∼100%, Figure 3A) and a longer inter-spike interval (∼57%, ISI) (Figure 3B) when compared to saline-injected animals. Importantly, inhibition of Sig-1Rs with either BD1063, BD1047 or Sig-1R siRNA rescued both spike onset (Figure 3A, C, Figure S3C) and ISI (Figure 3B, D, Figure S3D).

Figure 3. Cocaine-induced alterations in firing pattern are prevented by both pharmacological blockade and gene knockdown of the Sig-1R.

(A) Cocaine-induced increase in the latency to the fist spike is rescued by BD1063 (BD-coc). One-way ANOVA: p < 0.0001. (B) Left, Cocaine-induced increase in the inter-spike interval (ISI) is rescued by BD1063 (BD-coc). P < 0.005. Right, Sample traces at 200 pA. For panel A and B, n = 13-17 cells per group; 4-5 mice per group. (C) Cocaine-induced increase in the latency to the fist spike (siCon-coc) is rescued by Sig-1R siRNA (siSig-1R coc) (**p < 0.01). (D) Left, Cocaine-induced increase in the inter-spike interval (siCon-coc) is rescued by Sig-1R siRNA (siSig-1R coc) (**p < 0.01). Right, Sample traces at 240 pA. Calibration: 200 ms, 50 mV. For panel C and D, n = 6-17 cells per group; 4-6 mice per group. For all panels, post-hoc tests show that sal-coc and siCon coc are different from all other groups: ***p < 0.0001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S3.

Analysis of the action potential (AP) waveforms revealed a larger medium after-hyperpolarization (mAHP) (Figure S3A, S3E), a factor that determines the duration of the inter-spike interval and therefore results in decreased train frequency in neurons from cocaine-treated animals (Figure S3B). Medium AHP was also rescued by both BD1063 (Figure S3A) and BD1047 (Figure S3E). Consistent with a role of the Sig-1R in decreasing Na+ current (Johannessen et al., 2009), the time taken for the spike to rise was longer (sal-sal: 0.30 ± 0.02; sal-coc: 0.36 ± 0.02 ms; p < 0.05). However, slowing down the AP rise did not translate into increased AP width (sal-sal: 1.29 ± 0.06; sal-coc: 1.29 ± 0.03 ms), perhaps because cocaine also increases repolarizing K+ currents (Hu et al., 2004). Alteration in AP rise is then unlikely to play a significant role in cocaine-induced NAc MSN firing rate depression. No significant differences were observed in AP amplitude, threshold and fast AHP (data not shown).

In summary, changes in these electrophysiological components of the spike train indicate that multiple K+ conductances are altered. In MSNs, slowly inactivating D-type K+ currents (ID, also called IAs, mediated by Kv1 family) control subthreshold excitability (delaying AP onset) and regulate repetitive discharge (Nisenbaum et al., 1994). However, because mAHP is also altered, SK currents may play a role (Stocker, 2004). Thus, we hypothesized that MSN firing rate depression induced by repeated cocaine is due to increased ID and SK currents. Because ID activates at sub-threshold potentials and inactivates slowly, increased ID would delay spike onset and increase ISI. Since SK activates after a spike, increased SK would delay occurrence of subsequent spikes, which results in increased ISI (or decreased frequency).

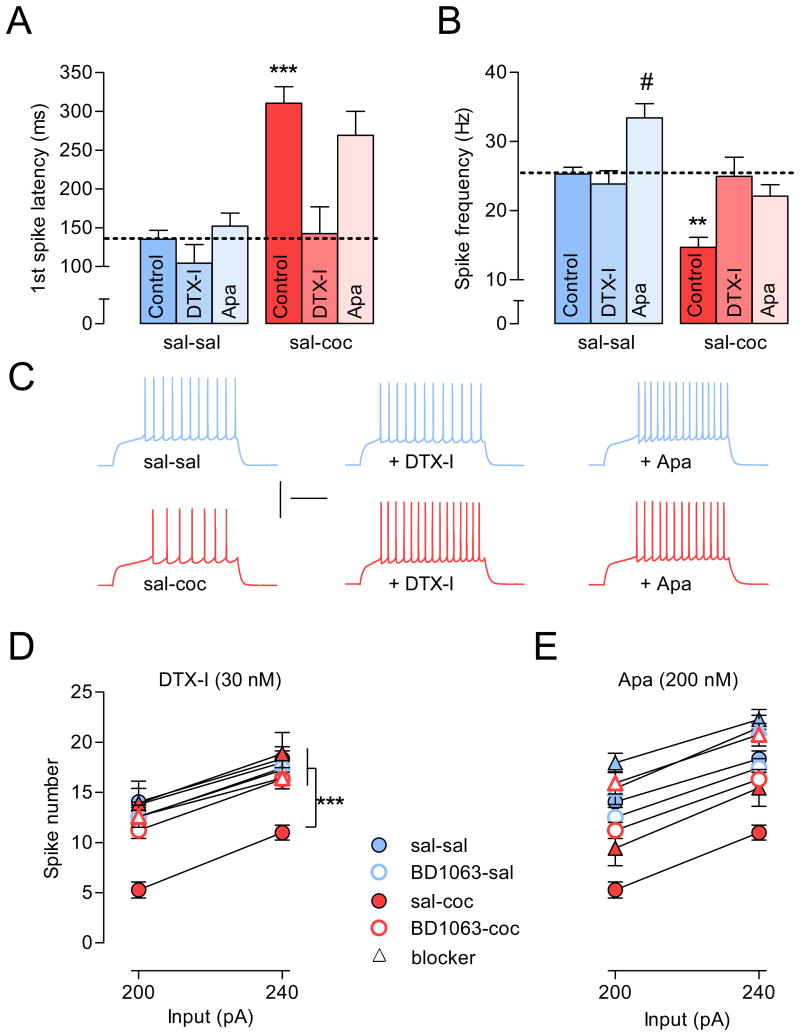

Thus, we investigated the potential involvement of ID and SK currents by using toxins that selectively block these K+ currents. We hypothesized that if repeated cocaine administration increases ID and SK currents, toxins that block these currents should have larger effects on cells from cocaine-treated animals compared to cells from saline- or BD1063-treated animals (BD1063-sal or BD1063-coc). Following the same experimental design as described in Figure 1B (ex vivo current-clamp recordings at 10-14 days after the last injection), we found that dendrotoxin-I (DTX-I, 30 nM), a selective Kv1.x-mediated ID blocker (Nisenbaum et al., 1994), decreased the latency to the 1st spike in cocaine-treated animals only [sal-coc vs. sal-sal, (Figure 4A, C)]. Consistent with its role in regulating APs discharge, blocking ID with DTX-I increased firing frequency only in the cocaine-treated group [sal-coc vs. sal-sal (Figure 4B, C)]. Effects of DTX-I on AP discharge could also be influenced by the role of ID in AHP (Shen et al., 2004), and consequently in ISI. Indeed, ID inhibition with DTX-I restored both the ISI (sal-sal: 44.34 ± 2.05; sal-coc: 85.74 ± 9.83; sal-coc + DTX-I: 50.76 ± 6.32 ms; one-way ANOVA, p < 0.01) and mAHP levels (sal-sal: 8.48 ± 1.34; sal-coc: 10.85 ± 0.34; sal-coc + DTX-I: 7.84± 0.70 ms; one-way ANOVA, p < 0.0001) to control levels (sal-sal). Furthermore, specific DTX-induced modulations of firing patterns translated to increased NAc shell MSN AP firing selectively in cocaine treated animals (sal-coc) without altering firing level in any other group (sal-sal, BD1063-sal and BD1063-coc) (Figure S4), an effect that normalized MSN firing rate depression to control levels (sal-sal) (Figure 4D). These results suggest that chronic cocaine administration depresses MSN firing rate through upregulation of ID.

Figure 4. Cocaine-induced shell MSN hypoactivity is triggered through Sig-1R-dependent upregulation of the D-type K+ current.

(A) ID inhibition with DTX-I (30 nM) but not SK inhibition with Apa (200 nM) rescues cocaine-induce increase in the latency to the 1st spike. One-way ANOVA: p < 0.0001; post hoc analysis: ***p < 0.0001, sal-coc group is different from all other groups except sal-coc + Apa. Dashed lines represent basal level for sal-sal control group. (B) While ID inhibition with DTX-I (30 nM) specifically rescues cocaine-induce decrease in the spike frequency, SK inhibition with Apa (200 nM) increases spike frequency in both control (sal-sal) and cocaine-treated group (sal-coc). One-way ANOVA: p < 0.0001. Post hoc analysis: **p < 0.001, sal-coc group is different from all other groups; #p < 0.05, sal-sal is different from sal-sal + Apa. Dashed lines represent basal level for sal-sal control group. In A and B, values correspond to parameters measured at 200 pA current injection. (C) Sample traces at 200 pA from sal-sal and sal-coc groups before and after toxins. (D) In cells from cocaine-treated animals, DTX-I renormalizes the number of spikes to control levels without affecting any other groups. For clarity, only number of spikes at 200 and 240 pA are presented, however statistical analysis was performed on the entire range of current injections (from 80 to 280 pA with 40 pA increment; two-way ANOVA, p < 0.0001). Post hoc analysis: sal-coc group is significantly different from any other groups. (E) Apamin positively shifts number of spikes in all groups. Two-way ANOVA: p < 0.0001; post-hoc analysis: all groups + blocker are significantly different from their respective group with no blocker. Calibration: 200 ms, 50 mV. For all panels, n = 5-28 cells per group; 3-11 mice per group. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S4.

Cocaine-induced increase in mAHP, a component that is influenced by SK current, may also contribute to the decreased firing frequency. Although the effects are opposite, two recent studies suggested that both cocaine (Ishikawa et al., 2009) and the Sig-1R (Martina et al., 2007) can modulate SK currents. Thus, we investigated a potential role for SK in cocaine-induced firing adaptation using the selective blocker apamin. SK inhibition with apamin (Apa) decreased mAHP to the same extent independent of cocaine treatment (e.g. delta from respective control at 200 pA: sal-sal + Apa = 1.6± 0.73; sal-coc + Apa = 2.3 ± 0.38 mV; p > 0.05), which translated into increased frequency in both groups [sal-sal and sal-coc (Figure 4B, C)]. As expected, because SK is not activated at subthreshold potential, apamin did not alter the latency to the first spike (Figure 4A). Furthermore, apamin-induced modulation of mAHP led to a similar increase in NAc shell MSN AP firing in all behavioral groups (Figure 4E and Figure S4). Analysis of a wide range of depolarizing current injections eliciting either low or high spike frequency (from 160 to 280 pA) did not reveal differential effects of apamin in any of the experimental groups, which indicates that 200 nM apamin is not a saturating and thereby potentially confounding dose. Our results suggest that, SK current is unlikely to play a role in cocaine-induced MSN hypoactivity.

Finally and because pre-treatment with BD1063 (BD1063-coc group) occluded subsequent effects of DTX-I but not apamin (Figure 4D, E, S4), our results indicate that long-lasting psychomotor responsiveness to cocaine is maintained via Sig-1R-dependent upregulation of the transient slowly-inactivating K+ current ID.

The Sig-1R upregulates ID through physical association with Kv1.2 channel

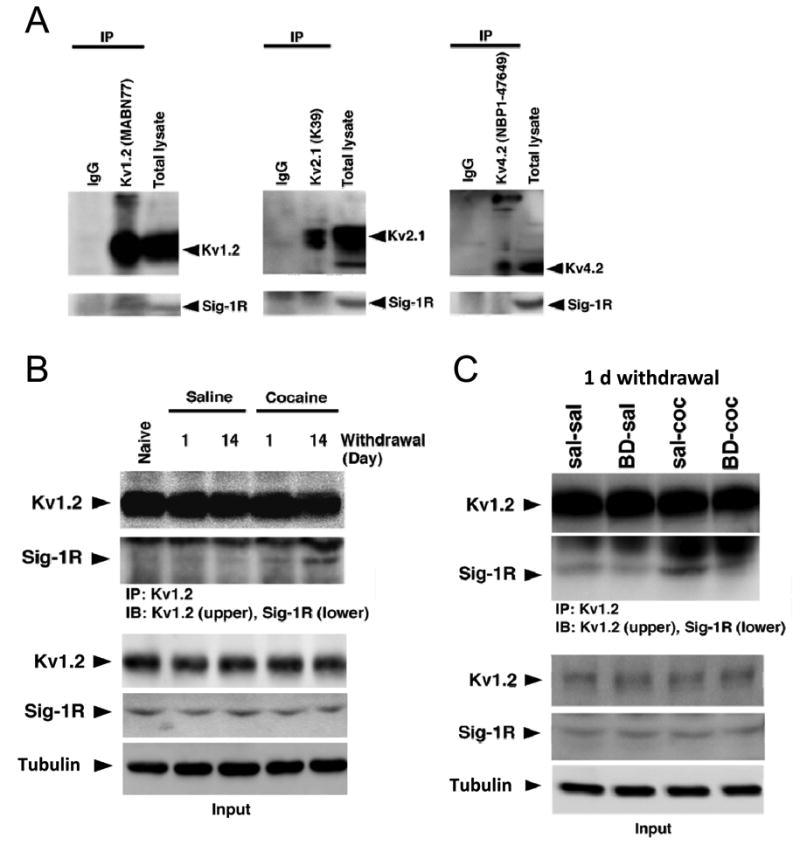

Increasing evidence suggest that in a heterologous system Sig-1R-dependent modulation of K+ currents may occur through direct protein-protein interaction to either modulate K+ channel function (Aydar et al., 2002; Kinoshita et al., 2012) or to regulate subunit trafficking (Crottes et al., 2011). We thus tested the hypothesis that activation of Sig-1Rs increases ID currents through physical interaction with K+ channel α-subunits that are known to generate ID in MSNs. Although many Kv1.x channel subunits that are expressed in MSNs can contribute to the generation of ID, including Kv1.1, Kv1.2 and Kv1.6 (Shaker family), Shen et al. (2004) demonstrated that Kv1.2 channels, but not Kv1.1 or Kv1.6, control the latency to the 1st spike and repetitive AP discharge. In addition, Kv2.1 channels (Shab family, mediating IK current), which co-localize with Sig-1Rs (Mavlyutov et al., 2010), and Kv4.2 channels (Shal family, mediating the fast-inactivating A-type K+ currents IAf), are both highly expressed in striatal neurons (Vacher et al., 2008), and also regulate substhreshold voltage behavior, firing frequency and voltage trajectory after spikes. To determine whether Kv1.2, Kv2.1 and/or Kv4.2 physically interact with Sig-1Rs, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments using membrane lysates from the NAc medial shell. We found that a marginal, yet detectable level of Sig-1Rs was co-immunoprecipitated with Kv1.2 (Figure 5A), and that no visible interaction between Kv2.1 or Kv4.2 and Sig-1Rs was detected, suggesting that in a basal state a fraction of Sig-1Rs form a complex with Kv1.2 channels in the NAc shell. We also observed similar results in mouse prefrontal cortex (Figure S5A), suggesting that the association between Kv1.2 and Sig-1Rs may not be restricted to the NAc but may also occur elsewhere in the brain.

Figure 5. Repeated in vivo cocaine upregulates physical association of Sig-1Rs with Kv1.2 α-subunits.

(A) Post-nuclear cell lysates were prepared from NAc medial shell tissue, immunoprecipitated with anti-Kv1.2, -Kv2.1 and -Kv4.2 antibodies or with normal immunoglobulins as control (IgG), then probed with anti-Sig-1R antibody. Only Kv1.2 co-immunoprecipitated Sig-1R (left panel, middle lane). Arrowheads indicate the position of the monomeric form of respective proteins. Kv1.2 and 4.2 also show oligomeric forms at the top of the images. (B) Cell lysates from NAc medial shell tissue were prepared from drug-naïve, saline and cocaine-treated groups collected at both early (one day) and late abstinence time points (14 days). Samples were immunoprecipitated with the anti-Kv1.2 antibody and probed with the anti-Kv1.2 (upper) or the anti-Sig-1R antibody (lower). Top, Repeated cocaine enhances Sig-1Rs co-immunoprecipitation with Kv1.2 (4th lane), an effect that is further increased after 14 days of protracted abstinence (5th lane). Bottom, Immunoblots quantifying total protein levels of Sig-1Rs and Kv1.2 subunits. Note that the protein levels remained unchanged throughout cocaine abstinence. (C) In a different set of animals, cell lysates of NAc medial shell tissue were prepared from saline ± BD1063 (sal-sal and BD-sal) and cocaine ± BD1063 (sal-coc and BD-coc) following the same experimental design as in Figure 1. Tissue was collected on the day following the last injection. Top, BD1063 prevents Sig-1Rs to co-immunoprecipitate with Kv1.2 (4th lane). Bottom, Immunoblots quantifying total protein levels of Sig-1Rs and Kv1.2 subunits. Note that protein levels remained unchanged following either of the treatment. Assays were performed with two samples per group, where each sample was prepared by combining NAc medial shell tissue pooled from 4-5 mice. See also Figure S5.

Because cocaine experience leads to an enduring Sig-1R-dependent upregulation of a DTX-sensitive K+ current, we then tested if cocaine upregulates interactions between Sig-1Rs and Kv1.2 channels in the NAc medial shell. Compared to controls, cell lysates from cocaine-treated mice exhibit higher binding levels between Sig-1Rs and Kv1.2 channels after one day of abstinence (Figure 5B, S5B), an effect that is prevented by BD1063 (Figure 5C, S5C left). Interestingly, this physical interaction seems to be further increased following a protracted abstinence period of 14 days (Figure 5B, S5B). Immunoblot quantification of cell lysates indicates that total protein levels of Sig-1Rs and Kv1.2 subunits were not different among groups, and remained unchanged across all time points (Figure 5C, S5C right). Taken together, our data suggest that Sig-1Rs form protein complexes with Kv1.2 channels in the NAc medial shell; and that this complex formation is increased upon cocaine experience.

These results are of particular importance as they provide, for the first time, evidence that the specific protein-protein interaction involving Sig-1Rs and Kv channels represent a novel element constituting experience-dependent neuronal plasticity in the NAc caused by cocaine exposure.

Cocaine induces trafficking of Sig-1Rs and Kv1.2 to the plasma membrane

Upon cocaine exposure, Sig-1Rs form additional physical associations with Kv1.2 channels to upregulate ID current. Since total protein levels of Sig-1Rs and Kv1.2 α-subunits were not different between saline- and cocaine-treated animals (Figure 5B, C), it appears likely that increased Sig-1R and Kv1.2 association may not be driven by transcriptional modifications of Sig-1R or Kv1.2 proteins per se, but rather by translocation of Sig-1Rs from the ER to the plasmalemma and binding to a pre-existing pool of Kv1.2 channels. However, because Sig-1Rs can also modulate K+ currents through the regulation of subunit trafficking activity (Crottes et al., 2011), it is possible that Sig-1Rs also traffic mature Kv1.2 channels from the ER to the plasmalemma.

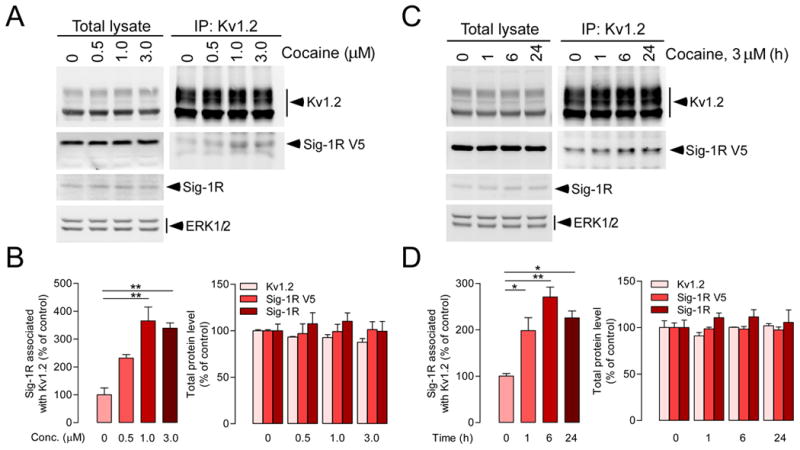

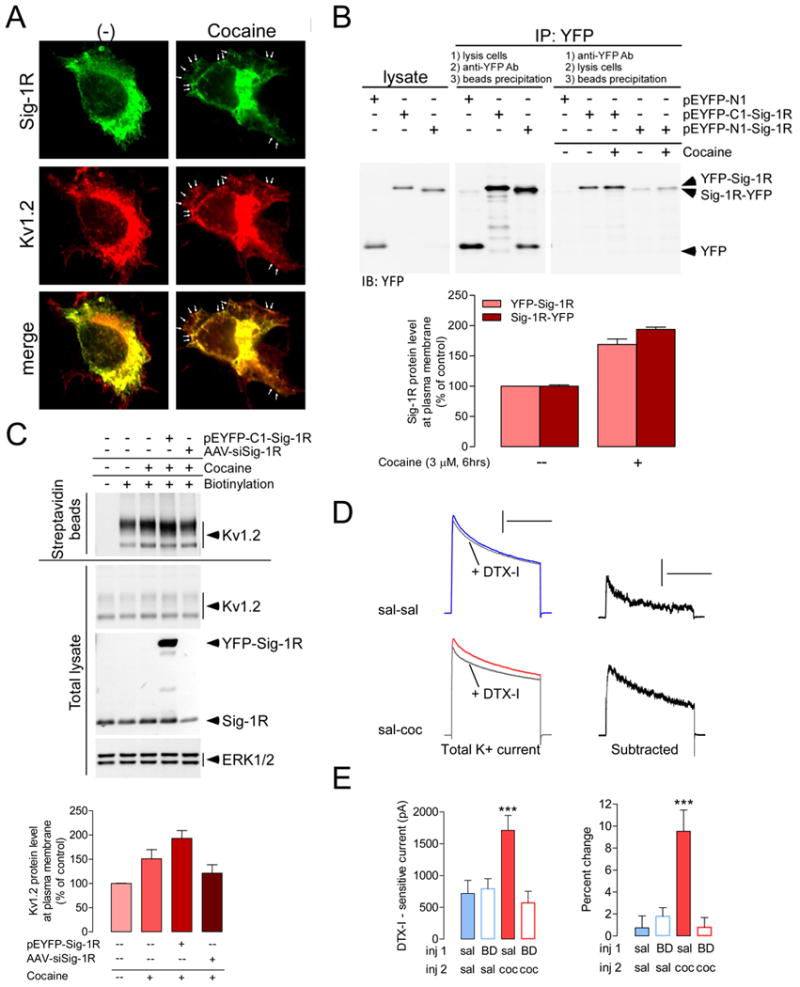

To differentiate between these two scenarios we overexpressed the Sig-1R and Kv1.2 subunits in the NG108-15 cell line. As in the NAc shell, Sig-1Rs bound to Kv1.2 channels in a basal state (Figure S6A, a and b, fourth lane) and cocaine bath application (3 μM, 6h) increased the binding (Figure S6Ba, compare 4th and 5th lane), an effect that is also observed in the neuro-2A cell line (Figure S6Bb). Furthermore, the cocaine-induced increase in Sig-1R and Kv1.2 binding is seemingly dose- (Figure 6B, left) and time-dependent (Figure 6D, left). Consistent with the NAc ex vivo study (Figure 5, S5C), cocaine did not change protein levels of Sig-1Rs and Kv1.2 α-subunits (Figure 6B and D, right panels), suggesting a cocaine-triggered subcellular redistribution of Sig-1Rs and Kv1.2 channels. Indeed, immunofluorescence double-labeling with anti-V5 (Sig-1R, green) and anti-Kv1.2 (red) antibodies revealed that cocaine (3 μM, 6 hrs) promotes co-localization of Kv1.2 and Sig-1Rs at the cellular surface (Figure 7A). Next, to provide direct evidence for the Sig-1R and Kv1.2 trafficking to the plasma membrane we used cell surface immunoprecipitation and biotinylation methods respectively. Beforehand, we demonstrated that cocaine decreased a small portion of Sig-1Rs at the MAM (Figure S7A, B). As the aim of this experiment was to test for a cocaine-induced decrease of Sig-1Rs specifically at the MAM we then performed assays using NG108-15 cells to address whether Sig-1Rs subsequently move to the plasma membrane. Since N- and C-termini of the Sig-1R are lumenal (Hayashi and Su, 2007), Sig-1R termini should upon translocation to the plasma membrane face the extracellular space. Using antibodies that specifically target N- and C-termini of the Sig-1R we showed that Sig-1Rs were present at the plasma membrane and that cocaine (3μM, 6h) further increased their levels by ∼75% (Figure 7B). Our data reveal for the first time that Sig-1Rs can be fully integrated into the phospholipidic layers rather than translocating at the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane. Next, we performed a biotinylation assay to detect the Kv1.2 subunit on the surface of the plasma membrane. Cocaine (3μM, 6h) increased membrane levels of Kv1.2 channels in both NG108-15 (Figure 7C) and neuro-2a cells (Figure S7C), an effect that was amplified by overexpression of the Sig-1R (+ pEYFP-Sig-1R) and prevented by Sig-1R knockdown with AAV-siSig-1R (Figure 7C). These results demonstrate that the cocaine-induced increase in membrane Kv1.2 channels is a consequence of Sig-1R activation.

Figure 6. Cocaine enhances the interaction between Sig-1R and Kv1.2 α-subunit in NG108-15 cells.

NG 108-15 cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1-Sig-1R-V5-His and pCMV6-Kv1.2 plasmids to overexpress Sig-1R-V5 and Kv1.2 respectively. Sig-1R-V5- and Kv1.2-overexpressing NG108-15 cells were treated with different doses of cocaine as indicated for 6 hrs (A, B) or with 3 μM of cocaine for different periods of time (0, 1, 6, and 24 h) (C, D). Cell extracts were then immunoprecipitated with the anti-Kv1.2 antibody followed by immunoblotting using anti-Kv1.2 or anti-V5 antibody respectively. The protein level of endogenous Sig-1Rs was detected using anti-Sig-1R antibody, and ERK1/2 was used as the loading control. Cocaine increases Sig-1R and Kv1.2 binding (B left, one-way ANOVA: treatment, p < 0.001; D left, one-way ANOVA: treatment, p < 0.01). In B and D (left panels), post-hoc tests when compared to control (0 μM or 0 h), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Consistent with NAc ex vivo studies (Figure 5), cocaine did not change protein levels of Sig-1Rs and Kv1.2 α-subunits (B and D, right). The graph represents means ± S.E.M. from three independent experiments. See also Figure S6.

Figure 7. Cocaine treatment increases the localization of Sig-1R and Kv1.2 α-subunit at the plasma membrane.

(A) In NG108-15 cells, cocaine (3 μM, 6 hrs) increases co-localization (arrowheads indicate puncta) of Kv1.2 (red) and Sig-1R (green) at the cellular surface. (B) NG108-15 cells were transfected with pEYFP-N1, pEYFP-C1-Sig-1R or pEYFP-N1-Sig-1R to express YFP, YFP-Sig-1R or Sig-1R-YFP respectively. Cocaine (3 μM, 6 hrs) increases Sig-1Rs at the membrane (blot in right) by ∼80% (bottom). Variations in the procedure between immunoprecipitation assays are indicated on the figure and described in methods. Differences in the intensity between the immunoblotting for the YFP-Sig-1R vs. Sig-1R-YFP may reflect differential receptor trafficking activity following the addition of YFP to either the N- or the C-terminal. Another explanation may lie in the different conformation of YFP-Sig-1R and Sig-1R-YFP at the surface and thereby differentially affecting the accessibility of antigenic sites of YFP to the detecting antibody. Nonetheless, cocaine enhances the surface expression of both YFP-Sig-1R and Sig-1R-YFP. (C) Kv1.2-overexpressing NG108-15 cells were co-transfected with pEYFP-C1-Sig-1R or AAV-siSig-1R as indicated. Cocaine (3 μM, 6 hrs) increases biotinylated Kv1.2 (streptavidin beads panel), but not total Kv1.2 (total lysate panel). ERK1/2 was used as the loading control. Bottom, Immunoblot quantifications showing that cocaine (3μM, 6 hrs) increases membrane levels of Kv1.2 channels, an effect that is amplified by overexpression of the Sig-1R (+ pEYFP-C1-Sig-1R) and prevented by Sig-1R knockdown with AAV-siSig-1R. The graphs represent means ± SEM from two independent experiments. (D) Left, K+ current traces in control solution and during bath application of DTX-I (30 nM) in sal-sal and sal-coc groups. Currents were evoked by depolarizing test pulses to + 30 mV after a prepulse of 2 s to -90 mV. Calibration: 500 ms, 5 nA. Right, Subtraction of current trace obtained in the presence of DTX-I from control solution. Calibration: 500 ms, 1 nA. (E) Repeated cocaine administration following the same experimental design as in Figure 1 (recordings at 10-14 days of abstinence) increases DTX-I - sensitive K+ current (left), a change that corresponds to a ∼10% blockade in cocaine-treated animals compared to ∼1% in control group [(Pre-DTX minus Post-DTX)/Pre-DTX × 100]. ANOVA: ***p < 0.0001. Post-hoc analysis for panel E left and right: sal-coc is different from all other groups. N = 7-10 cells per group; 4 mice per group. The graphs represent means ± SEM. See also Figure S7.

To assess functional outcomes of this effect, we have combined electrophysiological and pharmacological approaches and directly measured DTX-I - sensitive currents from the total K+ currents in NAc shell MSNs. Consistent with the specific effect of DTX-I on cocaine-induced firing rate depression, repeated cocaine administration increased DTX-I-sensitive currents (sal-coc vs. sal-sal; sal-sal: ∼720 pA; sal-coc: ∼1700 pA) which was prevented by pretreatment with BD1063 (BD-coc group) (Figure 7D, E).

Discussion

Our studies demonstrate that the accumbal Sig-1R enhances long-lasting behavioral sensitivity to cocaine through a decrease of neuronal intrinsic excitability—an effect that is induced by Sig-1R-dependent upregulation of ID. Furthermore, we provide the first evidence that in a basal state Sig-1Rs physically interact with Kv1.2 channels in the CNS—a channel that mediates ID in MSNs (Shen et al., 2004). Importantly, our data suggest that long-lasting behavioral sensitivity to cocaine is in part due to a persistent upregulation of the Sig-1R and Kv1.2 complex in the NAc shell. In vitro studies in cell lines suggest that this event occurs at the plasma membrane, however, ex vivo recordings in NAc shell provided functional evidence that such phenomenon may also occur in vivo.

Target Specificity

When investigating the role of the Sig-1R, ligand specificity is a major limiting factor. Therefore, to provide strong evidence for the involvement of the Sig-1R in the phenomena investigated in the present study, we used a multi-approach strategy including pharmacological tools, gene knockdown and biochemical assays (ex vivo and in vitro). First, we pharmacologically targeted the Sig-1R with two highly selective antagonists, BD1063 and BD1047 (Matsumoto et al., 1995). We found that both BD1063 (50 mg/kg) and BD1047 (5 mg/kg) attenuated cocaine-induced psychomotor sensitization in a similar manner and prevented cocaine-induced firing rate depression in NAc neurons (Figure 1, S1, 3, S3). Second, we used an AAV-siRNA targeting the Sig-1R protein expression. Effects of the Sig-1R siRNA yielded similar behavioral and physiological results as BD1063 and BD1047 (Figure 2, S2). Third, repeated administration of cocaine upregulated Kv1.2-mediated ID currents. If the Sig-1R was not a major mediator of this effect, increased cocaine-induced Sig-1R and Kv1.2 channel binding (in vivo in NAc shell and in vitro using NG108-15 and neuro-2a cell lines) and binding blockade by in vivo BD1063 would have been unlikely (Figure 5, S5, 6, S6, S7C). And last, overexpression or knockdown of the Sig-1R in vitro enhanced or prevented the cocaine-induced increase in membrane Kv1.2 channels respectively (Figure 7C), which demonstrates a causal relationship between the cocaine-induced increase in membrane Kv1.2 channels and Sig-1R activation. Taken together, results from our multi-approach strategy all converge towards a major role for accumbal Sig-1Rs in long-lasting effects of cocaine on both behavioral response to the drug and MSN firing rate.

Plasticity of the Sig-1R and Kv1.2 complex: a candidate substrate for long-lasting cocaine-induced MSN firing rate depression

Our data suggest that Sig-1R and Kv1.2 channel interaction is constitutive and/or occurs with endogenous agonists. The Kv1.2-mediated current plays a major role in controlling fundamental parameters that determine neuronal communication in striatal MSNs (Shen et al., 2004). This includes the capability of neurons to transition from silent to firing mode and the regulation of the inter-spike interval—a major parameter that tightly controls the frequency-modulated code that is characteristic of neurons (Hille, 2001). Recently, in vitro studies in heterologous systems showed that the Sig-1R, via physical association, modulates K+ currents either through the regulation of subunit trafficking (Crottes et al., 2011) or via ligand-independent modulation of channel function (Kinoshita et al., 2012). Taken together, the Sig-1R is emerging as a potential auxiliary subunit for voltage-gated K+ channels that is reminiscent of the already documented auxiliary β or KChip subunits (Vacher et al., 2008)—an idea first proposed by Jackson's group, which demonstrated in Xenopus oocytes that the Sig-1R, through physical association and in ligand-independent manner, regulates Kv1.4-mediated currents (Aydar et al., 2002).

Putative Sig-1R-dependent synergetic pathways in cocaine-induced accumbal hypoactivity

The present findings suggest a novel role for the Sig-1R that is linked to behavioral sensitivity to drugs of abuse, however, other cocaine-triggered Sig-1R signaling pathways may also contribute to the decreased shell MSN excitability. As the primary consequence of cocaine exposure is the accumulation of extracellular dopamine (DA) following DA transporter blockade, excess DA receptor (DAR) activation has been a prominent hypothesis for cocaine-induced changes in firing rate (Hopf et al., 2003; Perez et al., 2006). However, a recent study uncovered a novel cocaine-mediated signaling pathway that is independent of DA transporter blockade (Navarro et al., 2010). Sig-1Rs and DA 1 receptors (D1Rs) can form heteromers and when cocaine binds to this complex it amplifies D1R-mediated increases in cyclic AMP (cAMP). Cyclic AMP-dependent PKA activation regulates the striatal slowly-inactivating A-type K+ current ID (Hopf et al., 2003; Perez et al., 2006). However, in those studies, inhibiting PKA pathways decreases AP firing. Therefore, one might expect that cocaine binding to D1R-Sig-1R heteromers, which amplifies PKA signaling, would result in increased firing—an effect that is opposite to what we have observed. Although the complex formed by the D1R and the Sig-1R likely plays a role in the behavioral effects of cocaine, the signaling pathway that is initiated does not seem to result in changes in intrinsic postsynaptic neuronal excitability; perhaps, based on previous studies, one role for D1R-Sig-1R complexes is to modulate presynaptic glutamate release (Dong et al., 2007).

Another possibility involves αCaMKII, a strong modulator of fast-inactivating A-type K+ current (IAf) (Varga et al., 2004)—a current that may regulate MSN firing rate (Varga et al., 2000). A recent report showed that a transgenic mouse line overexpressing a constitutively active form of striatal-specific αCaMKII exhibits decreased intrinsic excitability in the NAc shell, which enhances cocaine reward, including psychomotor sensitization and conditioned place-preference (Kourrich et al., 2012a). Although the activated form of αCaMKII (CaMKII-pThr286) seems to occur through a D1R-dependent mechanism (Anderson et al., 2008), recent data suggest that activation of the Sig-1R also has the capability to increase αCaMKII-pThr286 (Moriguchi et al., 2011). Whether this mechanism results in modulation of neuronal firing is yet to be investigated. If so, this mechanism could represent an additional synergetic pathway through which cocaine-induced Sig-1R activation indirectly modulates shell neuronal excitability.

Data based Model

In drug-naïve animals, Sig-1Rs may constitutively regulate Kv1.2 channels to control MSN firing capability. Cocaine can bind to Sig-1Rs at a reward-relevant concentration (Chen et al., 2007; Kahoun and Ruoho, 1992), which triggers the Sig-1R to dissociate from the Binding immunoglobulin Protein (BiP), another ER chaperone protein that in absence of ligands prevents the Sig-1R from translocating to the plasmalemma (Hayashi and Su, 2003; Su et al., 2010). Repeated exposure to cocaine causes intracellular Sig-1Rs to persistently bind to Kv1.2 α-subunits and to traffic from the ER to the plasma membrane, which enhances ID. As a result, shell MSN intrinsic excitability is decreased—an adaptation that can promote appetitive reward-seeking behaviors (Kelley, 2004; Krause et al., 2010; Taha and Fields, 2006) and that is potentially involved in encoding the positive hedonic qualities of a stimulus (Carlezon and Thomas, 2009).

In conclusion, the functional consequence of the long-lasting interaction of Sig-1Rs and Kv1.2 channels represents a novel mechanism that shapes cocaine-dependent neuronal excitability. Whether this mechanism is involved in the development of drug addiction is yet to be investigated. Nonetheless, drug addiction is a chronic neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by its long-lasting vulnerability to relapse. Preventing the development of such a phenomenon by targeting the Sig-1R may provide complementary means to cope with this disease. However, because the Sig-1R, via interaction with various proteins (Kourrich et al., 2012b), is involved in a plethora of signaling pathways, directly targeting the Sig-1R is likely going to interfere with other cellular mechanisms and may lead to unwanted or potentially dangerous side effects. Therefore, and as shown here for the Sig-1R and Kv1.2 binding, the next step is clearly to establish a causal relationship between specific Sig-1R – protein associations and physiological outcomes, a step that will bolster the development of new efficient therapeutic tools that disrupt specific bindings. This advancement in basic cellular mechanisms will not only contribute to the development of treatment for drug addiction but also for other chronic diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, neuropathic pain and cardiac pathologies where both plasticity of intrinsic excitability and Sig-1Rs are engaged, some of which may occur through persistent Sig-1R binding to voltage-gated channels. Such innovation will certainly provide new avenues to target specific Sig-1R-related afflictions.

Experimental Procedures

Drug Treatment Regimen and Behavior

Male C57BL/6J mice (4–5 weeks of age) were habituated to the animal colony for 1 week before testing. For experiments in Figure 2, intra-NAc medial shell AAV-siRNA (containing either siCon, inactive siRNA; or siSig-1R, Sig-1R siRNA; Figure S2D) was infused two weeks before testing. In this experiment, mice were 7-8 weeks of age at the time of surgery. For all experiments, mice were group housed and maintained on a 12 hour light/dark cycle (light on at 7:00 A.M). On each of the five consecutive testing days (between 10:00 A.M. and 2:00 P.M.), mice were transferred from the animal colony to a testing room and placed individually into activity arenas (clear rectangular box, 13 × 15.5 × 7.5 inches). See Extended Experimental Procedures for details. The experimental procedures followed the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (eighth edition) and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee.

Drugs

1-[2-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl]-4-methylpiperazine (BD1063, Tocris) and N-[2-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl]-N-methyl-2-(dimethylamino)ethylamine (BD1047, Tocris) have preferential affinities for Sig-1R sites, with Ki values of ∼9 nM and ∼0.9 nM respectively. BD1063 has a 49-fold greater affinity for Sig-1R sites than Sig-2R sites. BD1047, likewise, has a 51-fold greater affinity for Sig-1R binding sites compared to Sig-2R sites (Matsumoto et al., 1995). BD1063 and cocaine hydrochloride were dissolved in 0.9% NaCl, and BD1047 in distilled water. Drugs were injected i.p. at a volume of 10 ml/kg.

Slice Preparation and Solutions

Sagittal slices of the NAc shell (240 μm) were prepared as described previously (Kourrich and Thomas, 2009). Slices recovered in a holding chamber for at least 1 h before use. During recording they were superfused with ACSF (31.5–32.5°C) saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2 and containing (in mM) 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 1.3 MgSO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 26.2 NaHCO3 and 11 glucose. During recordings, ACSF containing picrotoxin (100 μM) was used to block GABAA receptor-mediated IPSCs and kynurenic acid (2 mM) to block glutamate receptors. For voltage-clamp experiments investigating ID (DTX-I-sensitive current) (Figure 7D, E), voltage-dependent Na+, Ca2+ and Ca2+-dependent K+ currents were blocked with TTX (500 nM) and CdCl2 (100 μM). See Extended Experimental Procedures for details.

Electrophysiology

To quantify firing properties, whole-cell current-clamp recordings were performed with electrodes (3–5 MΩ) containing 120 K-gluconate, 20 KCl, 10 HEPES, 0.2 EGTA, 2 MgCl2, 4 Na2ATP, and 0.3 Tris–GTP at a pH of 7.20-7.25. Data were filtered at 5 KHz, digitized at 10 kHz, and collected and analyzed using Clampex 10.3 software (Clampex 10.3.0.2, Molecular Devices, Inc.). Membrane potentials were maintained at – 80 mV, series resistances (10–18 MΩ) and input resistances were monitored on-line with a 40 pA current injection (150 msec) given before each 700 msec current injection stimulus. Only cells with a stable Ri (Δ < 10%) for the duration of the recording were kept for analysis. The value of each parameter for a given cell was the average value measured from 2 to 4 cycles (experiments in Figure 1: 700 ms duration at 0.1 Hz, −80 to +280 pA range with a 40 pA step increment; experiments in Figure 2: 700 ms duration at 0.1 Hz, 0 to +320 pA range with a 80 pA step increment). For experiments in Figure 2, recordings from the two time points (1-3 days and 10-14 days) yielded similar effects per groups, therefore data from each group were pooled. See Extended Experimental Procedures for details on the method for quantifying differences in firing pattern and APs waveform.

K+ channel blockers (dendrotoxin-I, DTX-I at 30 nM; or apamin, Apa at 200 nM; Sigma-Aldrich) were either bath applied during recordings or administered in holding chambers containing brain slices. Because these two methods yielded similar effects per groups, data from each group were pooled.

For experiments in Figure 7D and 7E, voltage-clamp protocols to measure D-type K+ currents consisted of a voltage-step command from a holding potential of -80 mV. The neuron was hyperpolarized to -90 mV for 2 s and then to +30 mV for 1 s. Algebraic isolation of ID was performed by subtracting the current evoked in the presence of the ID channel blocker DTX-I (30 nM) from currents evoked in control solution. The peak current amplitude for each voltage command was calculated from the average of 3-5 traces. Leak subtraction was not performed, and series resistance was compensated at 60 %.

AAV siRNA vectors

The construction and packaging of the AAV vectors encoding Sig-1R siRNA (AAV-Sig-1R) and control siRNA (AAV-siCon) has been described previously (Tsai et al., 2009). Maps and siRNA sequences are shown in Supplemental Figure 2.

Cell Culture and Transfection

Mouse neuroblastoma × Rat glioma hybrid NG108-15 cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Invitrogen) without sodium pyruvate containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 0.1 mM hypoxanthine, 400 nM aminopterin, 0.016 mM thymidine. Mouse neuroblastoma Neuro-2a cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM, Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, and 100 U/ml penicillin G sodium. Transfection of cells with expression vectors was done by using PolyJet™ DNA In Vitro Tranfection Reagent (Signagen Laboratories) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Western Blotting

NAc medial shell tissue was microdissected for western blotting following electrophysiological recordings from mice that were infused with AAV-siRNA. See Extended Experimental Procedures for details.

Immunoprecipitation

NAc medial shell was collected using the same procedure as described in “Slice preparation and Solutions”, except that slices were transferred to ice-cold ACSF for microdissection and stored on ice until frozen at -80 °C. Brain tissues (NAc medial shell combining 4 or 5 brains/frontal cortices) were microdissected for immunoprecipitation assays. See Extended Experimental Procedures for details.

Statistics

On >90% of recording days, data were collected from both saline ± BD1063 or cocaine ± BD1063 groups in semi-randomized manner. Results are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Statistical significance was assessed using two-tailed Student's t-tests, one-way ANOVA or 2-way repeated measures ANOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc tests when appropriate.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Sig-1R activity enhances sensitivity to cocaine by decreasing accumbal firing

Cocaine decreases accumbal firing via Sig-1R-dependent increase of Kv1.2 current

The Sig-1R forms a complex with Kv1.2 channel in the NAc shell

Cocaine triggers a long-lasting upregulation of the Sig-1R-Kv1.2 channel complex

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Billy T. Chen, Beate C. Finger and Roy A. Wise for careful reading of the manuscript. We thank Dhara V. Patel, Stephanie Goddard, Janice Joo and Keenan Hope for technical help. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Viral vectors provided by the NIDA Optogenetics and Transgenic Technology Core facility (Lab head: Brandon K. Harvey).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information: Supplemental Information includes Extended Experimental Procedures and seven figures.

References

- Aydar E, Palmer CP, Klyachko VA, Jackson MB. The sigma receptor as a ligand-regulated auxiliary potassium channel subunit. Neuron. 2002;34:399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00677-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Thomas MJ. Biological substrates of reward and aversion: a nucleus accumbens activity hypothesis. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Hajipour AR, Sievert MK, Arbabian M, Ruoho AE. Characterization of the cocaine binding site on the sigma-1 receptor. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3532–3542. doi: 10.1021/bi061727o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crottes D, Martial S, Rapetti-Mauss R, Pisani DF, Loriol C, Pellissier B, Martin P, Chevet E, Borgese F, Soriani O. Sig1R protein regulates hERG channel expression through a post-translational mechanism in leukemic cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:27947–27958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.226738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong LY, Cheng ZX, Fu YM, Wang ZM, Zhu YH, Sun JL, Dong Y, Zheng P. Neurosteroid dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate enhances spontaneous glutamate release in rat prelimbic cortex through activation of dopamine D1 and sigma-1 receptor. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:966–974. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundlach AL, Largent BL, Snyder SH. Autoradiographic localization of sigma receptor binding sites in guinea pig and rat central nervous system with (+)3H-3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-N-(1-propyl)piperidine. J Neurosci. 1986;6:1757–1770. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-06-01757.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Su TP. Regulating ankyrin dynamics: Roles of sigma-1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:491–496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Su TP. Intracellular dynamics of sigma-1 receptors (sigma(1) binding sites) in NG108-15 cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:726–733. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.051292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Su TP. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones at the ER-mitochondrion interface regulate Ca(2+) signaling and cell survival. Cell. 2007;131:596–610. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YL, Zhang CL, Gao XF, Yao JJ, Hu CL, Mei YA. Cyproheptadine Enhances the I(K) of Mouse Cortical Neurons through Sigma-1 Receptor-Mediated Intracellular Signal Pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. 3rd. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hopf FW, Cascini MG, Gordon AS, Diamond I, Bonci A. Cooperative activation of dopamine D1 and D2 receptors increases spike firing of nucleus accumbens neurons via G-protein betagamma subunits. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5079–5087. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05079.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu XT, Basu S, White FJ. Repeated cocaine administration suppresses HVA-Ca2+ potentials and enhances activity of K+ channels in rat nucleus accumbens neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1597–1607. doi: 10.1152/jn.00217.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S. Brain reward circuitry beyond the mesolimbic dopamine system: a neurobiological theory. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:129–150. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M, Mu P, Moyer JT, Wolf JA, Quock RM, Davies NM, Hu XT, Schluter OM, Dong Y. Homeostatic synapse-driven membrane plasticity in nucleus accumbens neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5820–5831. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5703-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen M, Ramachandran S, Riemer L, Ramos-Serrano A, Ruoho AE, Jackson MB. Voltage-gated sodium channel modulation by sigma-receptors in cardiac myocytes and heterologous systems. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296:C1049–1057. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00431.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahoun JR, Ruoho AE. (125I)iodoazidococaine, a photoaffinity label for the haloperidol-sensitive sigma receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1393–1397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AE. Ventral striatal control of appetitive motivation: role in ingestive behavior and reward-related learning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;27:765–776. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M, Matsuoka Y, Suzuki T, Mirrielees J, Yang J. Sigma-1 receptor alters the kinetics of Kv1.3 voltage gated potassium channels but not the sensitivity to receptor ligands. Brain Res. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.02.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourrich S, Klug JR, Mayford M, Thomas MJ. AMPAR-independent effect of striatal alphaCaMKII promotes the sensitization of cocaine reward. J Neurosci. 2012a;32:6578–6586. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6391-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourrich S, Su T, Fujimoto M, Bonci A. The sigma-1 receptor: roles in neuronal plasticity and disease. Trends in Neurosciences. 2012b doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.1009.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourrich S, Thomas MJ. Similar neurons, opposite adaptations: psychostimulant experience differentially alters firing properties in accumbens core versus shell. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12275–12283. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3028-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause M, German PW, Taha SA, Fields HL. A pause in nucleus accumbens neuron firing is required to initiate and maintain feeding. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4746–4756. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0197-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupardus PJ, Wilke RA, Aydar E, Palmer CP, Chen Y, Ruoho AE, Jackson MB. Membrane-delimited coupling between sigma receptors and K+ channels in rat neurohypophysial terminals requires neither G-protein nor ATP. J Physiol. 2000;526(Pt 3):527–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martina M, Turcotte ME, Halman S, Bergeron R. The sigma-1 receptor modulates NMDA receptor synaptic transmission and plasticity via SK channels in rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2007;578:143–157. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.116178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto RR, Bowen WD, Tom MA, Vo VN, Truong DD, De Costa BR. Characterization of two novel sigma receptor ligands: antidystonic effects in rats suggest sigma receptor antagonism. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;280:301–310. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice T, Su TP. The pharmacology of sigma-1 receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;124:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavlyutov TA, Epstein ML, Andersen KA, Ziskind-Conhaim L, Ruoho AE. The sigma-1 receptor is enriched in postsynaptic sites of C-terminals in mouse motoneurons. An anatomical and behavioral study. Neuroscience. 2010;167:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi S, Yamamoto Y, Ikuno T, Fukunaga K. Sigma-1 receptor stimulation by dehydroepiandrosterone ameliorates cognitive impairment through activation of CaM kinase II, protein kinase C and extracellular signal-regulated kinase in olfactory bulbectomized mice. J Neurochem. 2011;117:879–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu P, Moyer JT, Ishikawa M, Zhang Y, Panksepp J, Sorg BA, Schluter OM, Dong Y. Exposure to cocaine dynamically regulates the intrinsic membrane excitability of nucleus accumbens neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3689–3699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4063-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro G, Moreno E, Aymerich M, Marcellino D, McCormick PJ, Mallol J, Cortes A, Casado V, Canela EI, Ortiz J, et al. Direct involvement of sigma-1 receptors in the dopamine D1 receptor-mediated effects of cocaine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18676–18681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008911107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisenbaum ES, Xu ZC, Wilson CJ. Contribution of a slowly inactivating potassium current to the transition to firing of neostriatal spiny projection neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1174–1189. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.3.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Perez MF, White FJ, Hu XT. Dopamine D(2) receptor modulation of K(+) channel activity regulates excitability of nucleus accumbens neurons at different membrane potentials. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:2217–2228. doi: 10.1152/jn.00254.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds SM, Berridge KC. Positive and negative motivation in nucleus accumbens shell: bivalent rostrocaudal gradients for GABA-elicited eating, taste “liking”/“disliking” reactions, place preference/avoidance, and fear. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7308–7320. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-07308.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Review. The incentive sensitization theory of addiction: some current issues. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:3137–3146. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Hernandez-Lopez S, Tkatch T, Held JE, Surmeier DJ. Kv1.2-containing K+ channels regulate subthreshold excitability of striatal medium spiny neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:1337–1349. doi: 10.1152/jn.00414.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriani O, Vaudry H, Mei YA, Roman F, Cazin L. Sigma ligands stimulate the electrical activity of frog pituitary melanotrope cells through a G-protein-dependent inhibition of potassium conductances. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:163–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. Pathways to relapse: factors controlling the reinitiation of drug seeking after abstinence. Nebr Symp Motiv. 2004;50:197–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker M. Ca(2+)-activated K+ channels: molecular determinants and function of the SK family. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:758–770. doi: 10.1038/nrn1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su TP, Hayashi T, Maurice T, Buch S, Ruoho AE. The sigma-1 receptor chaperone as an inter-organelle signaling modulator. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:557–566. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taha SA, Fields HL. Inhibitions of nucleus accumbens neurons encode a gating signal for reward-directed behavior. J Neurosci. 2006;26:217–222. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3227-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SY, Hayashi T, Harvey BK, Wang Y, Wu WW, Shen RF, Zhang Y, Becker KG, Hoffer BJ, Su TP. Sigma-1 receptors regulate hippocampal dendritic spine formation via a free radical-sensitive mechanism involving Rac1xGTP pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:22468–22473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909089106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacher H, Mohapatra DP, Trimmer JS. Localization and targeting of voltage-dependent ion channels in mammalian central neurons. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1407–1447. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga AW, Anderson AE, Adams JP, Vogel H, Sweatt JD. Input-specific immunolocalization of differentially phosphorylated Kv4.2 in the mouse brain. Learn Mem. 2000;7:321–332. doi: 10.1101/lm.35300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga AW, Yuan LL, Anderson AE, Schrader LA, Wu GY, Gatchel JR, Johnston D, Sweatt JD. Calcium-calmodulin-dependent kinase II modulates Kv4.2 channel expression and upregulates neuronal A-type potassium currents. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3643–3654. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0154-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Cuevas J. sigma Receptor activation blocks potassium channels and depresses neuroexcitability in rat intracardiac neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:1387–1396. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.084152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.