Abstract

WRKY transcription factors are known to function in a number of plant processes. Here we have characterized 15 WRKY family genes of the important ornamental species chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium). A total of 15 distinct sequences were isolated; initially internal fragments were amplified based on transcriptomic sequence, and then the full length cDNAs were obtained using RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) PCR. The transcription of these 15 genes in response to a variety of phytohormone treatments and both biotic and abiotic stresses was characterized. Some of the genes behaved as would be predicted based on their homology with Arabidopsis thaliana WRKY genes, but others showed divergent behavior.

Keywords: Chrysanthemum morifolium, phylogenetic analysis, stress response, transcription pattern

1. Introduction

Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat.) is a leading ornamental species, second only to the rose in terms of its market value [1]. In 2010, more than two billion cut chrysanthemum stems were produced in China, and almost the same number in Japan [2]. Since the major constraints faced by chrysanthemum producers are a range of biotic and abiotic stresses, enhancing the crop’s resistance/tolerance to these is an important breeding aim.

The WRKY family is prominent among plant transcriptional regulators, so named because of the presence of the characteristic peptide sequence WRKYGQK [3]. Sweet potato SPF1 was the first WRKY protein to have been isolated [4]. Based on the number of WRKY domains present and the structure of the protein’s zinc finger motifs, three major groups of WRKY proteins have been recognized [5]. Group I proteins contain two WRKY domains and a C2H2 zinc finger motif, group IIs a single WRKY domain and a C2H2 zinc finger motif, and group IIIs a C2HC zinc finger motif [5]. WRKY transcription factors are known to be involved in the regulation of a number of aspects of plant growth and development, as well as in the response to stress [6,7,8,9]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, for example, they participate in the response to low temperature, drought and salinity [10], while others have been implicated in signaling in the context of pathogen infection [11,12,13,14,15] and herbivore attack [16]. They have been shown to interact with phytohormones, especially salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonate (JA) [17,18].

As yet, however, the various activities of WRKY proteins in chrysanthemum have not been explored. Here, we report the isolation of 15 chrysanthemum WRKY transcription factors, based on a set of transcriptomic data, and have analyzed the effect of various stress and phytohormone treatments on their level of transcription.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. The WRKY Gene Content of Chrysanthemum

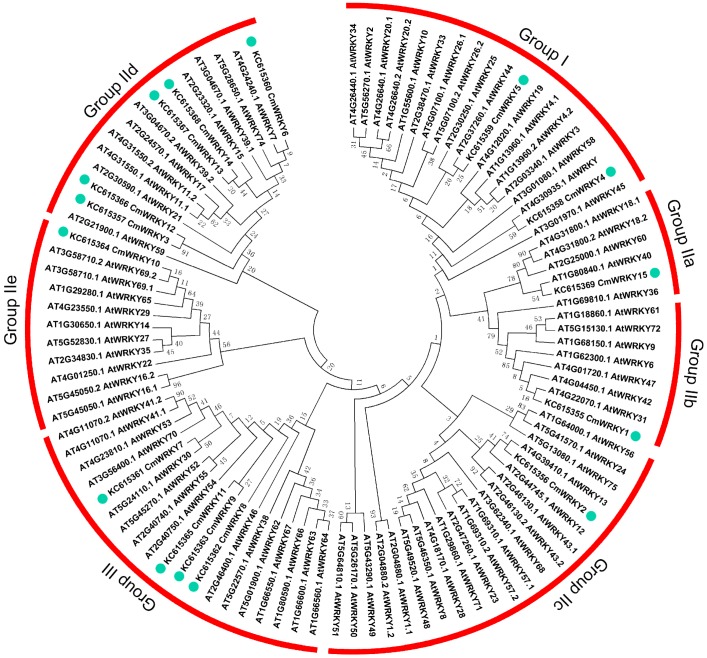

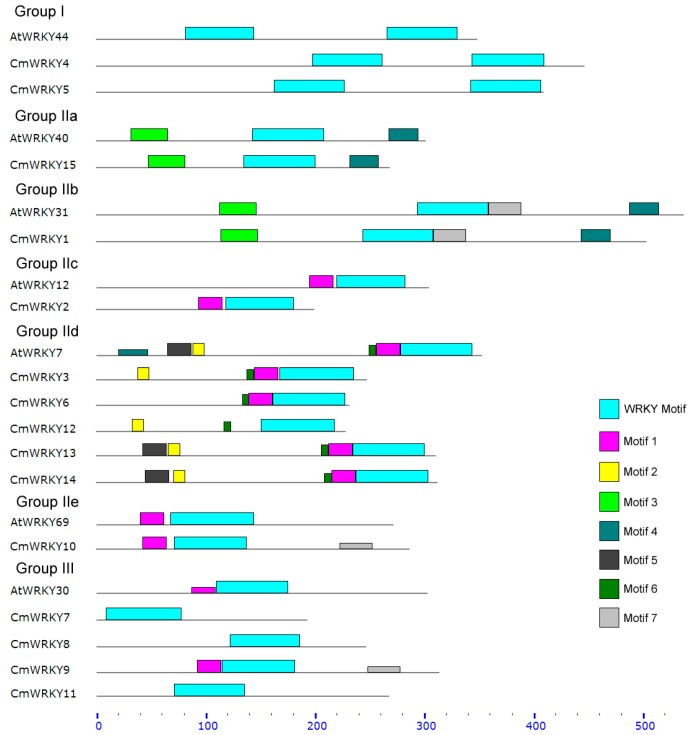

The 15 WRKY sequences isolated were designated CmWRKY1 through CmWRKY15 (GenBank: KC615355–KC615369). The full length cDNAs varied in length from 757 to 1750 bp, and their predicted protein products comprised between 193 and 504 residues. Full details of the CmWRKY sequences are given in Table 1. A combination of sequence comparison, phylogenetic and structural analyses suggested that the 15 CmWRKY genes were distributed across the three known WRKY groups (Figure 1), and a schematic overview of the core motifs present is shown in Figure S1. There was a high degree of homology between the motifs present in the CmWRKYs and those in the AtWRKYs (Figure 2). Motif 6 only featured in Group IId, while motif 3 was present in both Groups IIa and IIb (Figure S1).

Table 1.

CmWRKY gene sequences and the identity of likely A. thaliana homologs.

| Gene | GenBank Accession No. | cDNA Length (bp) | Amino Acids Length (aa) | AtWRKY Orthologs | Locus Name | E-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CmWRKY1 | KC615355 | 1750 | 504 | AtWRKY6 | AT1G62300 | 5e-86 |

| CmWRKY2 | KC615356 | 823 | 200 | AtWRKY13 | AT4G39410 | 2e-47 |

| CmWRKY3 | KC615357 | 928 | 248 | AtWRKY11 | AT4G31550 | 3e-38 |

| CmWRKY4 | KC615358 | 1608 | 447 | AtWRKY32 | AT4G30935 | 3e-68 |

| CmWRKY5 | KC615359 | 1668 | 410 | AtWRKY44 | AT2G37260 | 5e-74 |

| CmWRKY6 | KC615360 | 1119 | 232 | AtWRKY21 | AT2G30590 | 2e-56 |

| CmWRKY7 | KC615361 | 757 | 193 | AtWRKY41 | AT4G11070 | 2e-31 |

| CmWRKY8 | KC615362 | 1019 | 247 | AtWRKY41 | AT4G11070 | 5e-30 |

| CmWRKY9 | KC615363 | 1331 | 314 | AtWRKY46 | AT2G46400 | 8e-37 |

| CmWRKY10 | KC615364 | 1216 | 287 | AtWRKY65 | AT1G29280 | 3e-49 |

| CmWRKY11 | KC615365 | 1117 | 268 | AtWRKY70 | AT3G56400 | 6e-31 |

| CmWRKY12 | KC615366 | 875 | 229 | AtWRKY17 | AT2G24570 | 3e-24 |

| CmWRKY13 | KC615367 | 936 | 311 | AtWRKY7 | AT4G24240 | 6e-65 |

| CmWRKY14 | KC615368 | 942 | 313 | AtWRKY7 | AT4G24240 | 1e-53 |

| CmWRKY15 | KC615369 | 941 | 268 | AtWRKY40 | AT1G80840 | 1e-43 |

Figure 1.

An unrooted phylogenetic tree of the WRKY peptide sequences of chrysanthemumand A. thaliana. Sequences were aligned using ClustalW and the phylogeny constructed using the neighbor-joining method. The red arcs indicate the various groups (and subgroups) defined by the presence/absence of known WRKY domains. Dots indicate likely homologs.

Figure 2.

The amino acid motifs present in the CmWRKY and AtWRKY proteins, as determined by Meme 4.8.1 software [19]. The cyan boxes represent WRKY motif, and other colored boxes each represent a specific motif with uncharacterized function.

Orthology detection is critically important for accurate functional annotation, and has been widely used to facilitate studies on comparative and evolutionary genomics. A trade-off between sensitivity and specificity in orthology detection was observed, with BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool)-based methods characterized by high sensitivity, and phylogeny-based methods by high specificity [20], so the relationship between the chrysanthemum and A. thaliana WRKY genes was analyzed using both BLAST (which delivers a local sequence alignment) and by a rooted phylogenetic tree (global sequence alignment) (Table 1, Figure 1). Some inconsistencies were noted: for example, CmWRKY7 and AtWRKY69 appeared to be closely related according to the phylogenetic analysis, but the BLAST comparison predicted that the closest A. thaliana sequence to CmWRKY7 was AtWRKY41. Gene function analysis may therefore be needed to conclude which of these relationships is the more likely to be valid.

2.2. Transcription Profiling of CmWRKY Genes

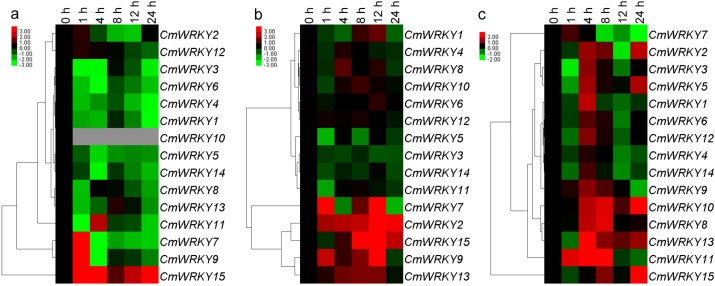

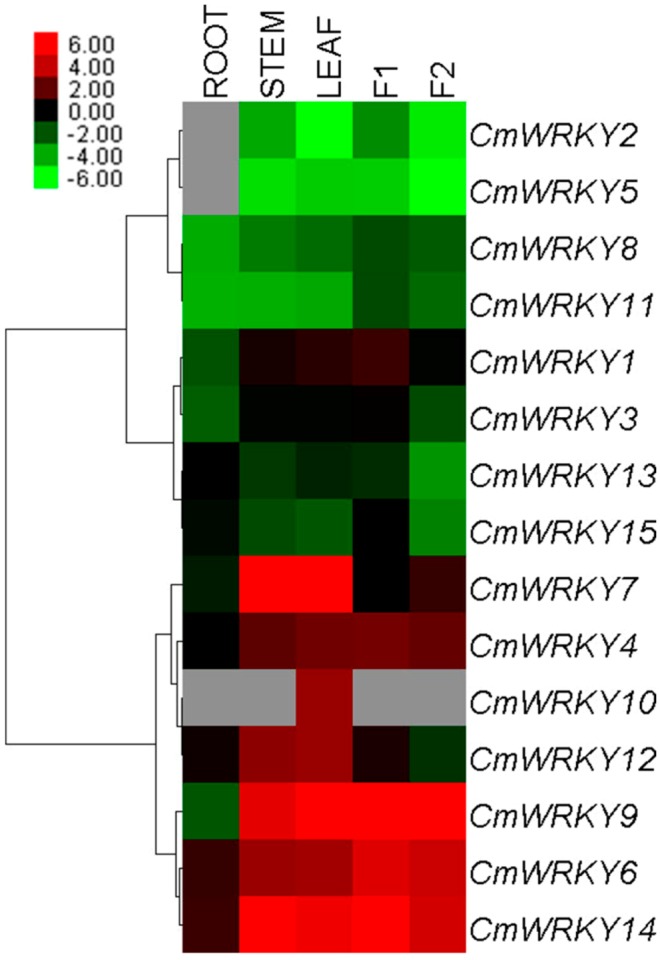

The 15 CmWRKY genes were differentially transcribed throughout the plant (Figure 3). The transcript abundance of CmWRKY14 was more than three orders of magnitude higher than that of CmWRKY2 in the leaf, while CmWRKY10 transcript was only detectable in the leaf under non-stressed conditions. Neither CmWRKY2 nor CmWRKY5 transcript was present in the root. The level of transcription shown by CmWRKY in tube florets was at least double that present in ray florets at budding stage, besides CmWRKY7 was exception.

Figure 3.

Differential transcription of CmWRKY genes. F1: tube florets, F2: ray florets at budding stage. Green indicates lower and red higher transcript abundance compared to the relevant control. Grey blocks indicate that transcription was not detected.

2.3. The Transcription of CmWRKY Genes in Plants Challenged by Phytohormones and Abiotic Stress

Twelve of the 15 genes were down-regulated by exogenous ABA (abscisic acid) (the exceptions were CmWRKY7, 9 and 15), while the abundance of CmWRKY10 transcript was below the level of detection. CmWRKY15 was induced by this treatment, while CmWRKY7 and 9 were also induced, but only after exposure of least 1 h (Figure 4a). None of CmWRKY1, 4, 6, 8, 10 or 12 were responsive to MeJA (methyl jasmonate) treatment, but CmWRKY2, 9, 13 and 15 were induced, while CmWRKY3, 5, 11 and 14 were all repressed (Figure 4b). Eleven of the genes (the exceptions were CmWRKY7, 9, 10 and 11) were repressed after 1 h exposure to SA treatment, but their transcription was triggered after 4 h (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Differential transcription of CmWRKY genes in leaves as induced by the exogenous supply of (a) abscisic acid (ABA); (b) methyl jasmonate (MeJA) and (c) salicylic acid (SA). Green indicates lower and red higher transcript abundance compared to the relevant control. Grey blocks indicate that transcription was not detected.

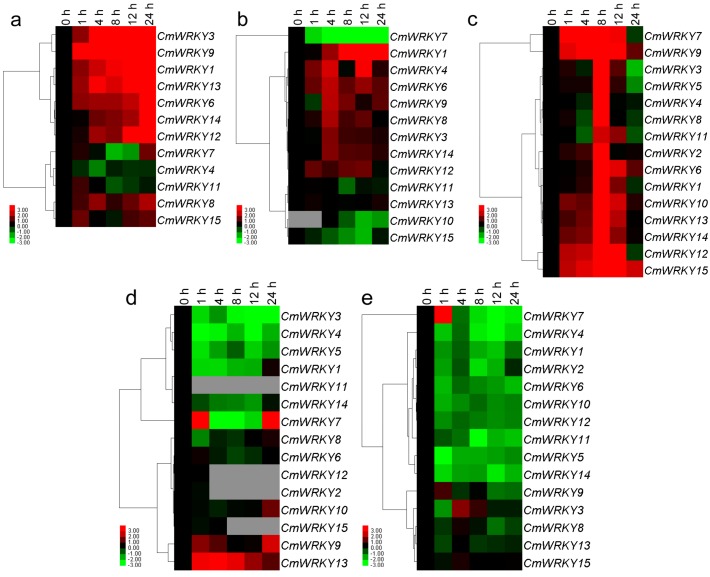

CmWRKY1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 13 and 14 were all up-regulated in the root by salinity stress, while CmWRKY4 was down-regulated. The transcript abundance of CmWRKY7, 11 and 15 was enhanced after 1 h of exposure, but later fell back (Figure 5a). The effect of moisture stress was to up-regulate CmWRKY1, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 12 and 14 in the root by various amounts, while CmWRKY7 transcription was markedly suppressed. Transcription of CmWRKY10 was noted after 4 h of exposure to PEG (polyethylene glycol), but was not transcribed in non-stressed roots (Figure 5b). All of the CmWRKY genes were induced by exposure to low temperature, with the peak transcript abundance occurring after 8 h (Figure 5c). With the exception of CmWRKY7, 9 and 13, the genes were all down-regulated by high temperature; the abundance of CmWRKY2, 11, 12 and 15 transcript was below the level of detection (Figure 5d). Apart from CmWRKY7 and 9, the genes were all down-regulated by wounding (Figure 5e).

Figure 5.

Differential transcription of CmWRKY genes as induced by abiotic treatments at the seedling stage. (a) roots in salinity; (b) roots in moisture stress; (c) leaves in low temperature; (d) leaves in high temperature and (e) leaves undergo wounding. Green indicates lower and red higher transcript abundance compared to the relevant control. Grey blocks indicate that transcription was not detected.

2.4. Differential Responses of the CmWRKY Genes to Biotic Stress

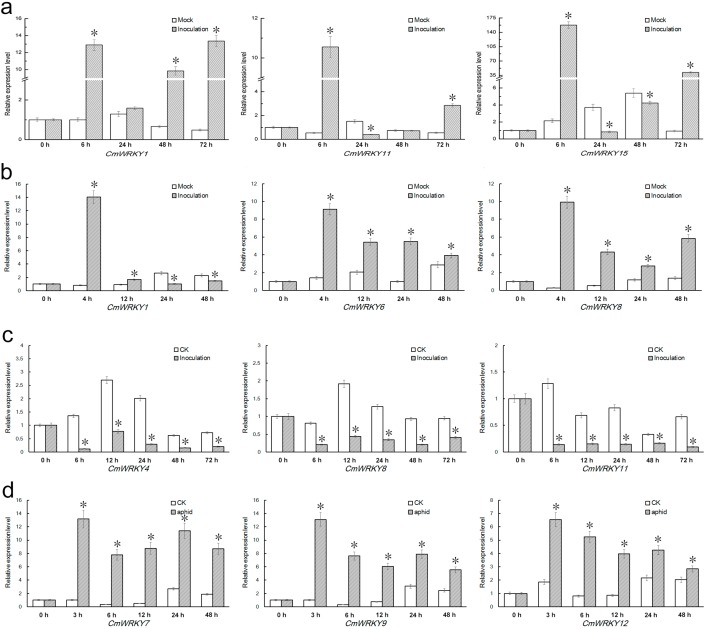

CmWRKY1, 11 and 15 were strongly induced by the presence of A. tenuissima inoculum, particular CmWRKY15, for which the level of transcript was some 80 fold higher than that of the non-inoculated control after 6 h (Figure 6a). CmWRKY1, 6 and 8 were all induced by about 10 fold when assayed 4 h after inoculation with F. oxysporum (Figure 6b). CmWRKY4, 8 and 11 were markedly suppressed by P. horiana inoculation (Figure 6c), while CmWRKY7, 9 and 12 responded positively to aphid infestation (Figure 6d). The expression changes of other CmWRKY genes were less than two fold in magnitude.

Figure 6.

Differential expression patterns of the CmWRKY genes in leaves to biotic stress. (a) inoculation with A. tenuissima; (b) inoculation with F. oxysporum; (c) inoculation with P. horiana; and (d) infestation with the aphid M. sanbourni. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between treatment and control plants.

2.5. Comparison of the Expression Pattern between CmWRKY Genes and Correlated Arabidopsis Homologs

Accumulating evidence suggests that many WRKY genes are involved in the regulation of plant development and their stress response [3,21]. Here, it was clear that the CmWRKY genes differed from one another with respect to their tissue specificity and inducibility. The various stress treatments affected the transcription level of different combinations of the 15 CmWRKY genes, implying that most of them do contribute to the stress responses of chrysanthemum. The A. thaliana genes AtWRKY6 [22], 40 [23], 41 [14] and 70 [24] all participate in the defense against pathogen attack, and their homologs (as determined by BLAST) CmWRKY1, 8, 11 and 15 were similarly induced by pathogen inoculation. On the other hand, AtWRKY31 (the homolog of which, based on phylogeny, is CmWRKY1) has no known involvement in the disease response. AtWRKY17 is up-regulated by salinity stress [25], as is its homolog CmWRKY12. AtWRKY11, 17 and 70, all of which are induced by wounding, drought and low temperature [26,27,28], also play a role in the interaction between SA and JA [29,30]. Their orthologs in chrysanthemum (respectively, CmWRKY3, 12 and 11) were also induced by moisture stress (PEG treatment) and low temperature, but were down-regulated by wounding; and in converse response to exogenous SA and JA. AtWRKY70 is activated by SA but suppressed by JA [29]; its constitutive expression improves the level of resistance to biotrophic, but not to necrotrophic fungi [17,31]. Its chrysanthemum homolog CmWRKY11 was inducible by inoculation with necrotrophic fungi and the exogenous supply of SA, but suppressed by biotrophic fungi and JA, which is rather different from the behavior of AtWRKY70. AtWRKY40 is an important component of WRKY-mediated ABA signaling, and exogenous ABA treatment reduces both its transcription and translation [32]. CmWRKY15, its chrysanthemum homolog, was notably up-regulated by exogenous ABA, which again suggests that some pairs of WRKY homologs have evolved different functionality between A. thaliana and chrysanthemum. The function of AtWRKY13, 21 and 32 is not well understood, so little can be concluded by comparing these with their chrysanthemum homologs, respectively, CmWRKY3, 12 and 11.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Plant Materials

Cuttings of the cut flower chrysanthemum cultivar “Jinba”, maintained by the Chrysanthemum Germplasm Resource Preserving Center (Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China), were rooted in vermiculite in the absence of fertilizer in a greenhouse. After 14 days, they were transplanted into growth substrate, in preparation for exposure to a range of stress and phytohormone treatments.

3.2. Isolation and Sequencing of Full-Length CmWRKY cDNAs

Total RNA was isolated from leaves, stems, roots or florets using the RNAiso reagent (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The first cDNA strand was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA using M-MLV (Moloney murine leukemia virus) reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer pairs (listed in Table S1) were designed to amplify internal CmWRKY fragments, based on sequences identified in a chrysanthemum transcriptome database (unpublished data). The sequences of the resulting amplicons were used to derive full length cDNAs via 5'- and 3'-RACE PCR. For the 3' reaction, the first cDNA strand was synthesized using the dT adaptor primer dT-AP, and this was followed by a nested PCR based on the primer pair CmWRKYx-3-F1/F2 and the adaptor primer AP (Table S2). For the 5' reaction, the primers consisted of AAP and AUAP (provided with the 5' RACE System kit v2.0, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), along with the gene-specific primer pairs CmWRKYx-5-F1/F2 (Table S3). Where required, amplicons were purified using an AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction kit (Axygen, Hangzhou, China) and cloned into pMD19-T (TaKaRa) for sequencing. Finally, 15 pairs of gene-specific primers (CmWRKYx-ORF-F/R, Table S4) were elaborated to amplify the full open reading frame sequences.

3.3. Phylogeny of WRKY Sequences

A. thaliana WRKY sequences were downloaded from the Database of Arabidopsis Transcription Factors (DATF) [33], and combined with the newly acquired CmWRKY sequences to perform a multiple alignment analysis based on ClustalW software [34]. The subsequent phylogenetic analysis utilized the Neighbor-Joining method, and a graphical representation was produced with the help of MEGA5 software [35]. Internal branching support was estimated using 1000 bootstrap replicates. The MEME v4.8.1 program [19] served to identify the motifs present in the 15 CmWRKY proteins, using the parameter settings suggested by Huang [21], and retaining only motifs associated with an E value <e−5.

3.4. Plant Treatments

The tissue-specific and treatment-induced transcription profiles of the 15 CmWRKY genes was explored in young seedling roots, stems and leaves, and in the tube and ray florets of inflorescences at the bud stage. A variety of abiotic stresses was imposed, namely salinity (200 mM NaCl), moisture deficit (20% w/v polyethylene glycol (PEG6000)) [36], low temperature (4 °C), high temperature (40 °C) and wounding. Plants were also inoculated separately with three different fungi, namely the necrotroph Alternaria tenuissima, the biotroph Puccinia horiana and the hemibiotroph Fusarium oxysporum; further plants were infested with the aphid Macrosiphoniella sanbourni.

For the NaCl and PEG6000 assays, young plants were transferred to a liquid medium containing the stress agent, and the roots were sampled at various time points. Other seedlings were exposed to a period of either 4 or 40 °C in a chamber delivering a 16 h photoperiod and 50 μmol·m−2·s−1 light, after which the second true leaves were sampled [37]. The wounding treatment involved cutting the second true leaf. The phytohormone treatments involved spraying the leaves with either 50 μM abscisic acid (ABA) [38], 1 mM methyl JA (MeJA) [39] or 200 μM SA [40]. Plants were sampled prior to the stress treatment and then after one, four, eight, 12 and 24 h.

Spore suspensions of A. tenuissima and F. oxysporum were obtained from a 14 day old PDA (potato dextrose agar) cultures, to which 10 mL of sterile water had been added; the spore suspension was then filtered through four layers of cheesecloth, and the spore concentration adjusted to 107 per mL using a haemocytometer [41,42]. Leaves were sampled before inoculation with A. tenuissima and then after six, 24, 48 and 72 h; the roots were sampled prior to F. oxysporum inoculation, and then after four, 12, 24 and 48 h. Infection with P. horiana was achieved using the spray method described by Zandvoort et al. [43] with the following modifications: Briefly, the infected leaves containing white rust pustules were cut into small pieces and were dispersed in deionized water and filtered through medical gauze to remove any plant debris. The concentration of the pathogenic spore suspension was then adjusted using a hemacytometer slide to a concentration of 106 zoosporangia·mL−1 with deionized water containing one drop of Tween 20 before application to the plants until run-off, using a hand-held sprayer. Leaves were sampled before inoculation and then after six, 12, 24, 48 and 72 h. The method used for aphid infestation followed [44] with the following minor modifications: Briefly, twenty aphids in two instar nymphs were transferred to the plants by a soft brush. A 25 cm long × 12 cm diameter polyester cylinder capped with fine gauze was placed over each plant to prevent any movement of aphids between adjacent plants. Leaves were sampled prior to infestation, and then after three, six, 12, 24 and 48 h.

After sampling, all the material was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70 °C. Each treatment was replicated three times.

3.5. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

qPCRs were performed on Mastercycler ep realplex device (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Each 20 μL qPCR contained 10 μL SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara), 0.4 μL of each primer (10 μM), 4.2 μL H2O and 5 μL cDNA template. The PCR cycling regime comprised an initial denaturation (95 °C/2 min), followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C/10 s, 55 °C/15 s, 72 °C/20 s. A melting curve analysis was conducted following each assay to confirm the specificity of the amplicons. Gene special primers (sequences shown in Table S5) were designed using PRIMER3 RELEASE 2.3.4 [45], and the EF1α gene was used as a reference sequence. Relative transcript abundances were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method [46].

3.6. Data Analysis

The relative transcription levels of each CmWRKY were log2 transformed, and the profiles compared using Cluster v3.0 software [47] and visualized using Treeview [48]. SPSS v17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

4. Conclusions

The comparative analysis of functionality in chrysanthemum and A. thaliana suggests that the local alignment method is superior to phylogenetic analysis in predicting functional homology. The present study has documented the transcription behavior of 15 CmWRKY genes in response to a range of stress treatments. These data provide a basis for identifying which individual CmWRKY genes might be usefully targeted for improving the stress tolerance of chrysanthemum.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Natural Science Fund of Jiangsu Province (BK2011641, BK2012773), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University of the Chinese Ministry of Education (Grant No. NCET-10-0492, NCET-12-0890), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (KYZ201112, KYZ201147), Fund for Independent Innovation of Agricultural Sciences in Jiangsu Province [CX(12)2020], the Program for Hi-Tech Research, Jiangsu, China, (Grant No. BE2012350, BE2011325).

Supplementary Files

Author Contributions

SAP, LPL and CFD contributed to RACE PCR, real-time PCR, bioinformatics analysis and writing of the manuscript. JJF and CSM designed the experiments and contributed to revisions of the manuscript. LHY, ZJ, and SYF contributed to the biotic stresses treatments. ZL contributed to the abiotic stresses treatments. ZZH helped with the RNA extraction. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Shinoyama H., Aida R., Ichikawa H., Nomura Y., Mochizuki A. Genetic engineering of chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium): Current progress and perspectives. Plant Biotechnol. 2012;29:323–337. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teixeira da Silva J.A., Shinoyama H., Aida R., Matsushita Y., Raj S.K., Chen F. Chrysanthemum biotechnology: Quo vadis? Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2012;32:21–52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rushton P.J., Somssich I.E., Ringler P., Shen Q.J. WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishiguro S., Nakamura K. Characterization of a cDNA encoding a novel DNA-binding protein, SPF1, that recognizes SP8 sequences in the 5' upstream regions of genes coding for sporamin and beta-amylase from sweet potato. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1994;244:563–571. doi: 10.1007/BF00282746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eulgem T., Rushton P.J., Robatzek S., Somssich I.E. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01600-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo M., Dennis E.S., Berger F., Peacock W.J., Chaudhury A. MINISEED3 (MINI3), a WRKY family gene, and HAIKU2 (IKU2), a leucine-rich repeat (LRR) KINASE gene, are regulators of seed size in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17531–17536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508418102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pnueli L., Hallak-Herr E., Rozenberg M., Cohen M., Goloubinoff P., Kaplan A., Mittler R. Molecular and biochemical mechanisms associated with dormancy and drought tolerance in the desert legume Retama raetam. Plant J. 2002;31:319–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson C.S., Kolevski B., Smyth D.R. TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA2, a trichome and seed coat development gene of Arabidopsis, encodes a WRKY transcription factor. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1359–1375. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robatzek S., Somssich I.E. Targets of AtWRKY6 regulation during plant senescence and pathogen defense. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1139–1149. doi: 10.1101/gad.222702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seki M., Narusaka M., Ishida J., Nanjo T., Fujita M., Oono Y., Kamiya A., Nakajima M., Enju A., Sakurai T., et al. Monitoring the expression profiles of 7000 Arabidopsis genes under drought, cold and high-salinity stresses using a full-length cDNA microarray. Plant J. 2002;31:279–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim K.C., Lai Z., Fan B., Chen Z. Arabidopsis WRKY38 and WRKY62 transcription factors interact with histone deacetylase 19 in basal defense. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2357–2371. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.055566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukhtar M.S., Deslandes L., Auriac M.C., Marco Y., Somssich I.E. The Arabidopsis transcription factor WRKY27 influences wilt disease symptom development caused by Ralstonia solanacearum. Plant J. 2008;56:935–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai Z., Vinod K., Zheng Z., Fan B., Chen Z. Roles of Arabidopsis WRKY3 and WRKY4 transcription factors in plant responses to pathogens. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:1471–2229. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higashi K., Ishiga Y., Inagaki Y., Toyoda K., Shiraishi T., Ichinose Y. Modulation of defense signal transduction by flagellin-induced WRKY41 transcription factor in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2008;279:303–312. doi: 10.1007/s00438-007-0315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandey S.P., Roccaro M., Schon M., Logemann E., Somssich I.E. Transcriptional reprogrammingregulated by WRKY18 and WRKY40 facilitates powdery mildew infection of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2010;64:912–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhattarai K.K., Atamian H.S., Kaloshian I., Eulgem T. WRKY72-type transcription factors contribute to basal immunity in tomato and Arabidopsis as well as gene-for-gene resistance mediated by the tomato R gene Mi-1. Plant J. 2010;63:229–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shim J.S., Jung C., Lee S., Min K., Lee Y.W., Choi Y., Lee J.S., Song J.T., Kim J.K., Choi Y.D. AtMYB44 regulates WRKY70 expression and modulates antagonistic interaction between salicylic acid and jasmonic acid signaling. Plant J. 2013;73:483–495. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao Q.-M., Venugopal S., Navarre D., Kachroo A. Low oleic acid-derived repression of jasmonic acid-inducible defense responses requires the WRKY50 and WRKY51 proteins. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:464–476. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.166876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailey T.L., Boden M., Buske F.A., Frith M., Grant C.E., Clementi L., Ren J., Li W.W., Noble W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. [(accessed on 12 March 2013)];Nucleic Acids Res. 2009 37:W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. Available online: http://meme.nbcr.net/meme/intro.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen F., Mackey A.J., Vermunt J.K., Roos D.S. Assessing performance of orthology detection strategies applied to eukaryotic genomes. PLoS One. 2007;2:e383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang S., Gao Y., Liu J., Peng X., Niu X., Fei Z., Cao S., Liu Y. Genome-wide analysis of WRKY transcription factors in Solanum lycopersicum. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2012;287:495–513. doi: 10.1007/s00438-012-0696-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robatzek S., Somssich I.E. A new member of the Arabidopsis WRKY transcription factor family, AtWRKY6, is associated with both senescence- and defence- related processes. Plant J. 2001;28:123–133. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu X., Chen C., Fan B., Chen Z. Physical and functional interactions between pathogen-induced Arabidopsis WRKY18, WRKY40, and WRKY60 transcription factors. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1310–1326. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knoth C., Ringler J., Dangl J.L., Eulgem T. Arabidopsis WRKY70 is required for full RPP4-mediated disease resistance and basal defense against Hyaloperonospora parasitica. Mol. Plant Microbe Ineract. 2007;20:120–128. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-2-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang Y., Deyholos M. Comprehensive transcriptional profiling of NaCl-stressed Arabidopsis roots reveals novel classes of responsive genes. BMC Plant Biol. 2006;6:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-6-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen W., Provart N.J., Glazebrook J., Katagiri F., Chang H.-S., Eulgem T., Mauch F., Luan S., Zou G., Whitham S.A., et al. Expression profile matrix of Arabidopsis transcription factor genes suggests their putative functions in response to environmental stresses. Plant Cell. 2002;14:559–574. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee B.-H., Henderson D.A., Zhu J.-K. The Arabidopsis cold-responsive transcriptome and its regulation by ICE1. Plant Cell. 2005;17:3155–3175. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taki N., Sasaki-Sekimoto Y., Obayashi T., Kikuta A., Kobayashi K., Ainai T., Yagi K., Sakurai N., Suzuki H., Masuda T., et al. 12-Oxo-Phytodienoic acid triggers expression of a distinct set of genes and plays a role in wound-induced gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:1268–1283. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.067058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J., Brader G., Palva E.T. The WRKY70 transcription factor: A node of convergence for jasmonate-mediated and salicylate-mediated signals in plant defense. Plant Cell. 2004;16:319–331. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Journot-Catalino N., Somssich I.E., Roby D., Kroj T. The transcription factors WRKY11 and WRKY17 act as negative regulators of basal resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3289–3302. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.044149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J., Brader G., Kariola T., Tapio Palva E. WRKY70 modulates the selection of signaling pathways in plant defense. Plant J. 2006;46:477–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shang Y., Yan L., Liu Z.Q., Cao Z., Mei C., Xin Q., Wu F.Q., Wang X.F., Du S.Y., Jiang T., et al. The Mg-Chelatase H Subunit of Arabidopsis Antagonizes a Group of WRKY Transcription Repressors to Relieve ABA-Responsive Genes of Inhibition. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1909–1935. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.073874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo A., He K., Liu D., Bai S., Gu X., Wei L., Luo J. DATF: A database of Arabidopsis transcription factors. [(accessed on 22 January 2013)];Bioinformatics. 2005 21:2568–2569. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti334. Available online: http://datf.cbi.pku.edu.cn/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larkin M.A., Blackshields G., Brown N.P., Chenna R., McGettigan P.A., McWilliam H., Valentin F., Wallace I.M., Wilm A., Lopez R., et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song A., Lu J., Jiang J., Chen S., Guan Z., Fang W., Chen F. Isolation and characterisation of Chrysanthemum crassum SOS1, encoding a putative plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter. Plant Biol. (Stuttg.) 2012;14:706–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2011.00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song A., Zhu X., Chen F., Gao H., Jiang J., Chen S. A chrysanthemum heat shock protein confers tolerance to abiotic stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15:5063–5078. doi: 10.3390/ijms15035063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ricachenevsky F.K., Sperotto R.A., Menguer P.K., Fett J.P. Identification of Fe-excess-inducedgenes in rice shoots reveals a WRKY transcription factor responsive to Fe, drought and senescence. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2010;37:3735–3745. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.War A.R., Hussain B., Sharma H.C. Induced resistance in groundnut by jasmonic acid and salicylic acid through alteration of trichome density and oviposition by Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) AoB Plants. 2013;5:plt053. doi: 10.1093/aobpla/plt053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alaey M., Babalar M., Naderi R., Kafi M. Effect of pre-and postharvest salicylic acid treatment on physio-chemical attributes in relation to vase-life of rose cut flowers. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2011;61:91–94. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song A., Zhao S., Chen S., Jiang J., Chen S., Li H., Chen Y., Chen X., Fang W., Chen F. The abundance and diversity of soil fungi in continuously monocropped chrysanthemum. Sci. World J. 2013;2013:632920. doi: 10.1155/2013/632920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H., Chen S., Song A., Wang H., Fang W., Guan Z., Jiang J., Chen F. RNA-Seq derived identification of differential transcription in the chrysanthemum leaf following inoculation with Alternaria tenuissima. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zandvoort R., Groenewegen C.A.M., Zadoks J.C. Methods for the inoculation of Chrysanthemum morifolium with Puccinia horiana. Neth. J. Plant Pathol. 1968;74:174–176. [Google Scholar]

- 44.He J., Chen F., Chen S., Lv G., Deng Y., Fang W., Liu Z., Guan Z., He C. Chrysanthemum leaf epidermal surface morphology and antioxidant and defense enzyme activity in response to aphid infestation. J. Plant Physiol. 2011;168:687–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rozen S., Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol. 2000;132:365–386. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Hoon M.J., Imoto S., Nolan J., Miyano S. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1453–1454. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eisen M.B., Spellman P.T., Brown P.O., Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.