Abstract

Acinar cell carcinomas (ACCs) of the pancreas are a rare tumor accounting for only about 2% of all pancreas tumors. We report herein on this case and discuss how to distinguish ACCs from neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) and solid pseudo-papillary tumor (SPTs) morphologically and immunohistochemically. In cytological findings, the nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio was high, and the cytoplasm was granular, but zymogen granules were not evident. The nucleus was biased in location, assuming small circular and irregular forms. Chromatin was fine granular in shape and distributed nonuniformly, accompanied by evident nucleoli. Immunohistochemically was positive for β-catenin (cell membrane and part of nuclei), synaptophysin (focal), chromogranin A (focal) and chymotrypsin were all positive. Although the cytological distinction of ACCs from NETs and SPTs is difficult, the nuclear chromatin pattern and nuclear inclusion bodies, pseudopapillary arrangement and hyaline globules seem to play an important role in the cytological differential diagnosis. Furthermore, not only enzymatic and neuroendocrine markers, but also antibodies to β-catenin, vimentin and so on seem to be useful in the differential diagnosis.

Keywords: Acinar cell carcinoma, cytological differential diagnosis, endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration

Introduction

Acinar cell carcinomas (ACCs) of the pancreas are a rare tumor accounting for only about 2% of all pancreas tumors. Because ACCs morphologically resemble neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) and solid pseudopapillary tumors (SPTs), differential diagnosis of ACC based on the cytological findings has been reported to be difficult.[1,2,3] We recently encountered a case of ACC, which was difficult to distinguish morphologically from an NET and SPT on the basis of the pancreatic endoscopic ultrasound-guided and fine-needle aspiration biopsy findings. We report herein on this case and discuss how to distinguish ACCs from NETs and SPTs morphologically and immunohistochemically.

Case Report

At another hospital, a 41-year-old woman was found to have multiple tumors in the liver on ultrasound (US) and computed tomography (CT) scan images, and a pancreatic head tumor was detected on a contrast-enhanced CT scan. She was thus referred to our hospital with the suspected diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and multiple liver metastases. A low echoic 20 mm mass at the pancreatic head was punctured with a 22 gauge needle. The specimen was subjected to Diff-Quick staining and Pap staining. An ACC was suggested from the findings, but the possibility of NET or SPT was not ruled out. Subsequent cell block immunostaining strongly suggest a diagnosis of ACC. A definitive diagnosis of ACC was confirmed with a liver biopsy. Combined chemotherapy (TS1 + Gemzar) was applied.

Cytological findings

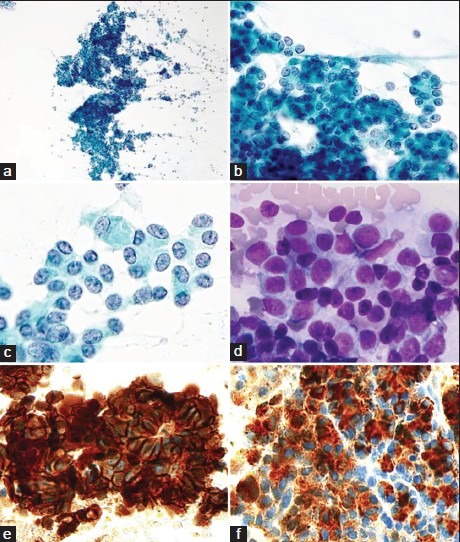

The background was necrotic, with atypical cells forming clusters or showing sporadic distribution. The clusters were solid and assumed an acinar structure, with numerous loosely bound atypical cells found around the clusters. The nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio was high, and the cytoplasm was granular, but zymogen granules were not evident. The nucleus was biased in location, assuming small circular and irregular forms. Chromatin was fine granular in shape and distributed nonuniformly, accompanied by evident nucleoli [Figure 1a–d]. Cell block staining was positive for β-catenin (cell membrane and part of nuclei) [Figure 1e], synaptophysin (focal), chromogranin A (focal) and chymotrypsin [Figure 1f] were all positive thus allowing a diagnosis of ACC.

Figure 1.

(a) The tumor cells forming clusters or showing sporadic distribution (Pap, ×100). (b) Acinar structures (Pap, ×200). (c, and d) The tumor cells show high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio and granular cytoplasm. The nuclei are small round in shape with fine granular chromatin (c: Pap, ×400, d: Diff -Quik, ×400). (e) β-catenin shows cell membrane and nuclear positivity (IHC, ×400). (f) Chymotrypsin shows cytoplasmic positivity (IHC, ×400)

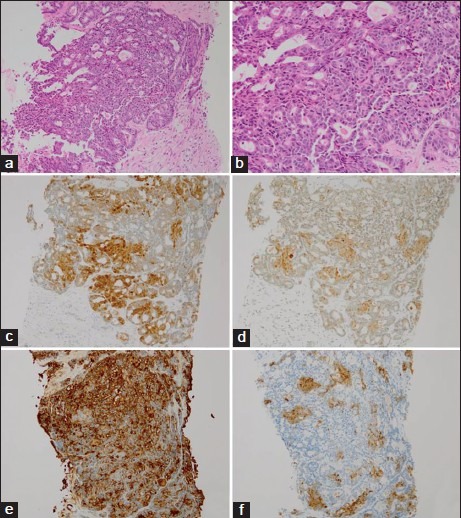

Histological findings: Liver biopsy

Tumor cells with evident nucleoli, densely stained nuclei and slightly eosinophilic scant cytoplasm had proliferated, assuming a fused gland-like and cribriform structure [Figure 2a and b]. Immunostaining was positive for β-catenin (cell membrane and part of nuclei), synaptophysin (focal), chromogranin A (focal), chymotrypsin and amylase [Figure 2c–f], thus confirming a definitive diagnosis of ACC.

Figure 2.

(a and b) The tumor cells showed growth into fused ductal or cribriform structures (a: H and E, ×100; b: H and E, ×200). (c) β-catenin shows cell membrane and nuclear positivity (IHC, ×100). (d) Synaptophysin shows focal cytoplasmic positivity (IHC, ×100). (e) Chymotrypsin shows cytoplasmic positivity (IHC, ×100). (f) Amylase show focal cytoplasmic positivity (IHC, ×100)

Discussion

Acinar cell carcinomas morphologically resemble tumors of a neuroendocrine feature such as PDAs, NETs, and SPTs, and for this reason, the accurate diagnosis rate of ACC based on cytological findings is low.[1,2,3] Sigel and Klimstra[1] have reported a discrepancy between the cytological and histological diagnoses in 14 of the 29 cases of malignant acinar tumors of the pancreas, stating that many cases of ACC were cytologically rated as NETs or PDAs. Also, in the present case, a definitive diagnosis of ACC was not possible on the basis of the cytological findings alone, and its distinction from a NET and SPT was difficult. The prognosis of ACCs is poor as compared with NETs and SPTs[2,4,5] and different chemotherapeutic regimens may be indicated for cases not indicated for surgery.[2,6] A firm differential diagnosis is therefore important. Cytological features allowing distinction between ACCs and NETs include structural and cytoplasmic features and the nuclear chromatin pattern. ACCs assume an acinar structure and possess zymogen granules in the cytoplasm. However, the cytological distinction of an acinar structure from rosette formation associated with NETs is difficult, and the zymogen granules in the cytoplasm are also difficult to detect with Diff-Quik or Pap staining.[1,2,3] For detection of zymogen granules, electron microscopy or the postperiodic acid-Schiff staining diastase digestive test is used, but these techniques are not specific to ACCs because zymogen granules are small in number or may have been replaced with mitochondria in the case of ACCs.[1,7] Additionally, in the present case, distinction from rosette formations and the detection of zymogen granules were difficult based on the cytodiagnosis although acinar structures and granular cytoplasms were noted. The nuclear chromatin in this case was fine granular and distributed nonuniformly, unlike the salt and pepper-like form associated with NETs. Labate et al.[3] also pointed out a similar nuclear chromatin pattern, reporting that it would be useful in distinction from NETs. Thus, differences in the nuclear chromatin pattern would appear to be useful in differential diagnosis. Furthermore, considering that an inclusion body in the nucleus was present in cases of NETs,[8] but absent in the present case, the nuclear inclusion bodies may also be useful as a feature toward differential diagnosis. Distinction from SPTs is also difficult because the cytological features of an ACC resemble an SPT and because the cytological findings from NETs are partially in common with ACCs.[1] Additionally, in the present case, distinction from an SPT was necessitated by the finding of clusters appearing pattern, a scattered distribution of numerous cells with biased nucleus location and myxomatous stroma. SPTs can be characterized by the pseudopapillary arrangement and the presence of hyaline globules,[9] which are usually absent in ACCs. These features were absent also in the present case, suggesting that the pseudopapillary arrangement and hyaline globules are useful in distinguishing ACC from an SPT. Immunohistologically, chymotrypsin and trypsin are positive in ACCs, but negative in NETs and SPTs. However, there is a report that enzymatic markers were positive in 5-66% of all cases of NETs,[10] so care is needed when differential diagnosis is attempted on the basis of enzymatic markers alone. In NET cases, neuroendocrine markers show a strong positive reaction diffusely, but these markers are often positive locally in ACCs and SPTs.[1,2,3] Furthermore, in the present case, neuroendocrine markers were locally positive and enzymatic markers were diffusely positive. For distinguishing ACC from NET by means of immunostaining, the expression pattern and intensity of neuroendocrine markers and enzymatic markers seem to be important. β-catenin is positive in the nucleus and cell membrane of ACCs while it is positive only in the cell membrane of NETs. This may therefore help achieve differential diagnosis. Distinguishing ACCs from SPTs on the basis of β-catenin seems to be difficult because β-catenin is positive in the nucleus and cytoplasm of SPTs, resembling its positive sites in ACC cases. However, since vimentin is strongly positive in SPTs,[2] the presence/absence of expression of enzymatic markers and vimentin would appear to be useful in distinguishing ACCs from SPTs. Although the cytological distinction of ACCs from NETs and SPTs is difficult, the nuclear chromatin pattern and nuclear inclusion bodies, pseudopapillary arrangement and hyaline globules seem to play an important role in the differential diagnosis. For precise distinction from NETs and SPTs, immunocytochemical staining and immunohistochemical staining are needed, and not only enzymatic and neuroendocrine markers, but also antibodies to β-catenin, vimentin and so on seem to be useful in the differential diagnosis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Sigel CS, Klimstra DS. Cytomorphologic and immunophenotypical features of acinar cell neoplasms of the pancreas. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:459–70. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stelow EB, Bardales RH, Shami VM, Woon C, Presley A, Mallery S, et al. Cytology of pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:367–72. doi: 10.1002/dc.20450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Labate AM, Klimstra DL, Zakowski MF. Comparative cytologic features of pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma and islet cell tumor. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;16:112–6. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199702)16:2<112::aid-dc3>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seth AK, Argani P, Campbell KA, Cameron JL, Pawlik TM, Schulick RD, et al. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: An institutional series of resected patients and review of the current literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1061–7. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0338-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowery MA, Klimstra DS, Shia J, Yu KH, Allen PJ, Brennan MF, et al. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: New genetic and treatment insights into a rare malignancy. Oncologist. 2011;16:1714–20. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valentino JD, Li J, Zaytseva YY, Mustain WC, Elliott VA, Kim JT, et al. Cotargeting the PI3K and RAS pathways for the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:1212–22. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hruban RH, Pitman MB, Klimstra DS. Tumors of the Pancreas. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu M, Ghafari S, Lin F, Ramzy I. Cytological diagnosis of endocrine tumors of the pancreas by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Diagn Cytopathol. 2005;32:204–10. doi: 10.1002/dc.20224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bardales RH, Centeno B, Mallery JS, Lai R, Pochapin M, Guiter G, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology diagnosis of solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: A rare neoplasm of elusive origin but characteristic cytomorphologic features. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:654–62. doi: 10.1309/DKK2-B9V4-N0W2-6A8Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yantiss RK, Chang HK, Farraye FA, Compton CC, Odze RD. Prevalence and prognostic significance of acinar cell differentiation in pancreatic endocrine tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:893–901. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]