Abstract

Background:

Eucalyptus cinerea F. Muell. ex Benth. is native to Australia and acclimatized to Southern Brazil. Its aromatic leaves are used for ornamental purposes and have great potential for essential oil production, although reports of its use in folk medicine are few.

Objective:

This study evaluated the composition of E. cinerea leaves using the solid state 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and isolation of the compound from the semipurified extract (SE).

Materials and Methods:

The SE of E. cinerea leaves was evaluated in the solid state by 13C-NMR spectrum, and the SE was chromatographed on a Sephadex LH-20 column, followed by high-speed counter-current chromatography to isolate the compound. The SE was analyzed by 13C-NMR and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight spectra.

Results:

Flavan-3-ol units were present, suggesting the presence of proanthocyanidins as well as a gallic acid unit. The uncommon ent-catechin was isolated.

Conclusion:

The presence of ent-catechin is reported for the first time in this genus and species.

Keywords: Circular dichroism, Eucalyptus cinerea, ent-catechin, flavan-3-ol units, solid-state 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance

INTRODUCTION

Eucalyptus cinerea F. Muell. ex Benth. (Myrtaceae) is known as “silver dollar tree”, “silver dollar gum,” “argyle apple,” or “silver eucalyptus.” Its young leaves are widely used in floral arrangements.[1,2] Native to Australia, this tree can reach up to 20 m high,[3] growing in any type of soil. It is grown in the Brazilian state of Paraná.[4] More resistant to cold climates than Eucalyptus globulus Labill., E. cinerea is considered valuable because it produces 1,8-cineol.[5] The 1,8-cineol content found in the aerial parts of E. cinerea (i.e. leaves, flowers, and fruits) may exceed 80%.[6,7] The essential oil from E. cinerea leaves showed activity against Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus.[7] Safaei-Ghomi and Ahd (2010) found antimicrobial and antifungal activity in the essential oil and methanol extract of two Eucalyptus species.[8] Previous phytochemical analyses of hydroalcoholic and aqueous extracts showed some positive biological results, indicating the presence of flavonoids and tannins that are frequently found in Eucalyptus species.[9] The structure of polyphenols has been identified by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) in the solid state.[10,11] This study analyzed a semi-purified fraction of E. cinerea leaves by the use of the solid-state 13C-NMR spectrum. The compound was isolated by high-speed counter-current chromatography (HSCCC) and characterized by the NMR technique and circular dichroism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

The plant material from E. cinerea was collected at the Centro Politécnico of the Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR), at Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil (25° 27’ 4” S, 49º 13’ 52” W, altitude 922 m), in 2009-2010. A voucher specimen of the material is deposited at the herbarium of the Botanical Department in the Sector of Biological Sciences at UFPR, under registration number UPCB#47863.

Preparation of extracts

The crude extract from dried and crushed E. cinerea leaves (600 g) was prepared by turbo-extraction (SKYMSEM, TA-02) using acetone/water (7:3; v/v) at a proportion of 10% (w/v) during 25 min.[12] The crude extract was then filtered and concentrated in a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure (Büchi R-114, t < 40°C) and then lyophilized, yielding 171.24 g. About 150 g of the crude extract was resuspended in distilled water (1500 mL) and partitioned with ethyl acetate (1500 mL, 10 times).[13] The ethyl acetate phases were combined, concentrated by rotary evaporator under reduced pressure, and lyophilized, yielding the ethyl-acetate fraction (56.53 g) and the aqueous phase (50.89 g). The amount of 500 mg of the semi-purified ethyl-acetate fraction was separated for structural analysis of the solid-state 13C-NMR spectrum.

Column chromatography

The ethyl-acetate fraction (6 g) was subjected to column chromatography (h: 700 mm, Ø: 55 mm) containing Sephadex®LH-20, using the mobile phase: 50% ethanol (F1, 1000 mL); 100% ethanol (F2, 800 mL); 50% methanol (F3, 600 mL); 100% methanol (F4, 600 mL), and 70% acetone (F5, 600 mL). Monitoring was performed on silica gel 60 F254 precoated thin layer chromatography (TLC) plates (0.200 mm, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and an eluent system composed of ethyl acetate:formic acid:water (90:5:5; v/v). The compounds were observed under UV light at 254 nm and then revealed by using FeCl3 at 1% in ethanol. Fractions were concentrated by rotary evaporator under reduced pressure, and then lyophilized, yielding 2.89 g (F1), 0.46 g (F2), 0.028 g (F3), 0.12 g (F4), and 0.35 g (F5). The F1 fraction (1 g) was partitioned with 400 mL of n-hexane/water (1:1; v/v). The hexane phase (F1-1) and the aqueous phase (F1-2) were concentrated and lyophilized. Subfraction F1-2 yielded 0.5853 g.

High-speed counter-current chromatography

Subfraction F1-2 (0.4 g) was subjected to HSCCC according to Mello et al.[13] and Lopes et al.[14] The eluent system used was n-hexane:ethyl acetate:methanol:water (1:5:1:5; v/v), with the lower phase being the stationary phase and the upper phase being the mobile phase. The 352 tubes were monitored by TLC and then combined by similarity, yielding 17 subfractions. From these subfractions, the isolated compound termed F1-2#10 was selected.

Structural analysis

The isolated compound F1-2#10 was analyzed by 1D (1H and 13C) and 2D (1H/1H COSY) NMR spectra and by optical methods (polarimetry,  Perkin Elmer 343, USA, and Circular Dichroism, Jasco J-815, Japan). NMR spectra were obtained on a Varian Mercury Plus 300BB, 300 MHz for 1H and 75 MHz for 13C, using deuterated solvent (CD3OD). The spectra of the compound were analyzed and compared with literature data.

Perkin Elmer 343, USA, and Circular Dichroism, Jasco J-815, Japan). NMR spectra were obtained on a Varian Mercury Plus 300BB, 300 MHz for 1H and 75 MHz for 13C, using deuterated solvent (CD3OD). The spectra of the compound were analyzed and compared with literature data.

The ethyl-acetate fraction was analyzed by solid-state 13C-NMR, with a 7 mm CP-MAS solid-state probe and a 7 mm silicon nitride rotor with a Kel-F cap, with rotation of 5 kHz, 33.9° pulse of 4.9 s and 1.0 s interval between pulse sequences (4168 repetitions) at frequency of 75 MHz.

The spectrum was recorded in a micrOTOF-QII-electrospray ionization (ESI)-TOF mass spectrometer (MS) (Brucker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA). ESI was performed using a time-of-flight analyzer (ESI-TOF-MS) in positive and negative modes within the range of m/z 900-3000.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

13C-nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum

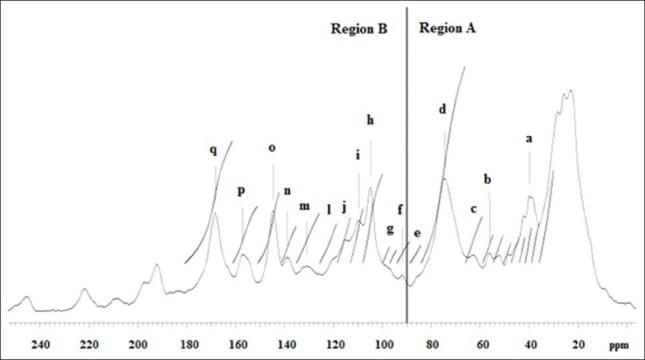

The 13C-NMR spectrum was obtained with the ethyl-acetate fraction from the semi-purified extract of E. cinerea leaves [Figure 1]. This analysis was based on Czochanska et al.[10] and Navarrete et al.[11] The spectrum was divided into two regions, A and B.

Figure 1.

Solid-state 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum of ethyl-acetate fraction. (a) prodelphinidin and procyanidin units (C-4); (b) methoxy carboxylic acid; (c) C-3 terminal unit flavan-3-ol; (d) C-2 prodelphinidin units (configuration 2,3-cis); (e) C-4 glucose; (f) C-8 flavonol unit; (g) C6 and C8 procyanidins; (h) C-3′, C-4’ and C-5′-OH of B ring; (i) C-2’ and C-6’ of prodelphinidin nonsubstituted B rings; (j) C-5’ inter-flavonoids; (l) C-6’ catechin unit; (m) C-1’ procyanidin unit; (n) C-4” gallic acid; (o) C-3’ and C-4′-OH of B ring; (p) C-5 and C-7-OH of flavonoids and condensed tannins; (q) C = O at position C-4 of flavonols

The chemical shifts of 30-90 ppm correspond to the ring in region A, and between 90 and 160 ppm, to the ring in region B. The region between 70 and 90 ppm corresponds to the stereochemistry of C ring.[15]

In region A, a bandwidth of δ 40 ppm can be seen, corresponding to C-4, which can be related to the cis or trans configuration.[10] Signals at δ 56 ppm correspond to the methoxy group,[16] which can be at C-4’ units of proanthocyanidins or at C-4” gallic acid.[13] Signals at δ 122 and 140 ppm correspond to C-1” and C-4” of gallic acid, respectively.[17] Signals at δ 65-66 ppm correspond to C-3 of the terminal unit flavan-3-ol.[10] At δ 75 ppm a bandwidth that corresponds to C-2 of prodelphinidin units with 2,3-cis configuration can be seen.[18] A signal at δ 92 ppm corresponds to C-8 of flavonols.[19] The chemical shift at δ 110 ppm confirms the presence of prodelphinidin units and the absence of procyanidins, indicating the presence of OH in C-3’. According to Koupai-Abyazani et al.[18] this signal corresponds to C-2’ and C-6’ of prodelphinidins, and Ishida et al.[14] established that there is no substitution of these carbons in the B ring, confirming the trihydroxylation in this ring.[18] A signal at δ 105 ppm indicates C-4 and C-8 with a 4 → 8 type bond, and perhaps a small contribution of C-6 in 4 → 6 bonds of procyanidin and prodelphinidin. The absence of a signal at δ 95 ppm combined with the presence of a signal at δ 105 ppm indicate the predominance of interflavonoid bonds with a 4 → 8 type of bonding, the standard classification of procyanidins.[20] Signals at δ 102-107 ppm indicate the presence of hydroxyls at positions C-3’, C-4’ and C-5’ of the B ring.[18] A signal at δ 86 ppm, although with low intensity, corresponds to the glycosidic bond of glucose in C4.[21] Signals at δ 116 ppm represent C-5’ of inter-flavonoid 4 → 8 type units, and for 4 → 6 bonds the signal is at δ 105 ppm.[11] A signal at δ 120 ppm indicates C-6’ of the catechin unit. At δ 130 ppm it characterizes C-1’ of procyanidin, at δ 139 ppm C-4” of gallic acid, and at δ 144 ppm C-3’ and C-4’-OH of the B ring.[21] A signal at δ 97 ppm suggests C6, C8 and C10 of procyanidins.[21] At δ 157 ppm, it corresponds to C-5 and C-7 with OH groups of flavonoids and condensed tannins related to the A ring.[11] A signal at δ 160-180 ppm indicates the presence of a C = O group at the C-4 position of flavonols.[19]

In the matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-TOF spectrum, a combination of the masses of the catechin and gallic acid monomers can be used to determinate the masses of the oligomer peaks. The peak in m/z 1055 [M + 23] + may be a combination of three catechin and one gallic acid units, additionally with a CH3 unit. Another peak in m/z 1261 [M + 1] + was calculated with three catechin and two gallic acid units.

Isolation and identification of compound by high-speed counter-current chromatography

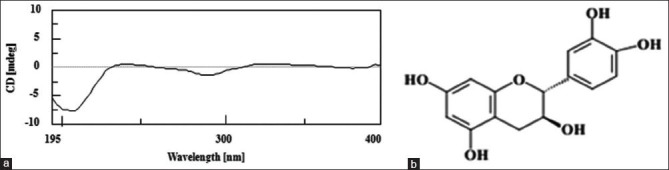

Analysis of spectral and chromatographic data of 1H NMR, 1H/1H COSY and 13C-NMR spectra of the isolated compound termed F1-2#10 showed close similarity to catechin compounds. Using authentic material,[22,23,24] the compound was easily identified by comparison of spectroscopic data (1H-and 13C-NMR spectra,  and circular dichroism). The absolute stereochemistry of compound F1-2#10 was carried out using the specific optical rotation, obtaining

and circular dichroism). The absolute stereochemistry of compound F1-2#10 was carried out using the specific optical rotation, obtaining  = −4.69° (methanol; c = 0.64). Analysis of catechin derivatives showed two aromatic chromophores - A and B benzene rings -, with absorption bands at around 280 nm (called transition Lb) and 240 nm (transition La). Concerning the A chromophore (transition Lb), the configurations 2 (R) and 2 (S) generate negative and positive Cotton effects, respectively. With respect to the B chromophore (transition La), a positive Cotton effect characterizes configuration 3(R) and a negative Cotton effect characterizes configuration 3 (S).[25] Thus, as seen in Figure 2a, it is concluded that catechin is 2 (S), 3 (R), because it has a positive Cotton effect in the A chromophore and a negative Cotton effect in the B chromophore. Therefore, the isolated compound F1-2#10 was identified as ent-catechin or (-)-catechin [Figure 2b], which is reported for the first time in this genus and species.

= −4.69° (methanol; c = 0.64). Analysis of catechin derivatives showed two aromatic chromophores - A and B benzene rings -, with absorption bands at around 280 nm (called transition Lb) and 240 nm (transition La). Concerning the A chromophore (transition Lb), the configurations 2 (R) and 2 (S) generate negative and positive Cotton effects, respectively. With respect to the B chromophore (transition La), a positive Cotton effect characterizes configuration 3(R) and a negative Cotton effect characterizes configuration 3 (S).[25] Thus, as seen in Figure 2a, it is concluded that catechin is 2 (S), 3 (R), because it has a positive Cotton effect in the A chromophore and a negative Cotton effect in the B chromophore. Therefore, the isolated compound F1-2#10 was identified as ent-catechin or (-)-catechin [Figure 2b], which is reported for the first time in this genus and species.

Figure 2.

(a) Circular dichroism spectroscopy of compound F1-2#10; (b) ent-catechin

CONCLUSION

The ethyl-acetate fraction from the leaves of E. cinerea contains units of flavan-3-ols, suggesting the presence of proanthocyanidins, as well as gallic acid and methoxy units. The uncommon ent-catechin is reported for the first time in leaves of E. cinerea.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the REUNI- Programa de Apoio ao Plano de Reestruturação e Expansão das Universidades Federais, CNPq and FINEP for financial support provided. Special thanks to Professor Dr. Olavo Guimarães (in memoriam), taxonomist of the Department of Botany/UFPR, for identifying the plant species.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The authors are grateful to the REUNI- Programa de Apoio ao Plano de Reestruturação e Expansão das Universidades Federais, CNPq and FINEP for financial support provided

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wirthensohn MG, Sedgley M. Effect of pruning on regrowth or cut foliage stems of seventeen Eucalyptus species. Aust J Exp Agric. 1998;38:631–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell SJ, Ogle HJ, Joyce DC. Glycerol uptake preserves cut juvenile foliage of Eucalyptus cinerea. Aust J Exp Agric. 2000;40:483–92. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mangieri HR, Dimitri MJ. Los Eucaliptos en la Silvicultura. Buenos Aires: Editorial Acme S.A.C.L. 1958 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreira EA, Cecy C, Nakashima T, Franke TA, Miguel OG. O óleo essencial de Eucalyptus cinerea F.v.M aclimatado no estado do Paraná-Brasil. Trib Farm. 1980;48:44–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rumyantseva LA. Eucalyptus cinerea as a source of cineol. Aptechn Delo. 1958;7:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zrira S, Bessiere JM, Menut C, Elamrani A, Benjilali B. Chemical composition of the essential oil of nine Eucalyptus species growing in Morocco. Flavour Fragr J. 2004;19:172–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva SM, Abe SY, Murakami FS, Frensch G, Marques FA, Nakashima T. Essential oils from different plant parts of Eucalyptus cinerea F Muell ex Benth (Myrtaceae) as a source of 1,8-cineole and their bioactivities. Pharmaceuticals. 2011;4:1535–50. doi: 10.3390/ph4121535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Safaei-Ghomi J, Ahd AA. Antimicrobial and antifungal properties of the essential oil and methanol extracts of Eucalyptus largiflorens and Eucalyptus intertexta. Pharmacogn Mag. 2010;6:172–5. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.66930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa AF. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian; 1986. Farmacognosia. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Czochanska Z, Foo LY, Newman RH, Porter LJ. Polymeric proanthocyanidins Stereochemistry, structural units, and molecular weight. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans I. 1980:2278–86. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navarrete P, Pizzi A, Pasch H, Rode K, Delmotte L. MALDI-TOF and 13C-NMR characterization of maritime pine industrial tannin extract. Ind Crops Prod. 2010;32:105–10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cork SJ, Krockenberger AK. Methods and pitfalls of extracting condensed tannins and other phenolics from plants: Insights from investigations on Eucalyptus leaves. J Chem Ecol. 1991;17:123–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00994426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mello JC, Petereit F, Nahrstedt A. Flavan-3-ols and prodelphinidins from Stryphnodendron adstringens. Phytochemistry. 1996;41:807–13. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopes GC, Machado FA, Toledo CE, Sakuragui CM, Mello JC. Chemotaxonomic significance of 5-deoxyproanthocyanidins in Stryphnodendron species. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2008;36:925–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishida K, de Mello JC, Cortez DA, Filho BP, Ueda-Nakamura T, Nakamura CV. Influence of tannins from Stryphnodendron adstringens on growth and virulence factors of Candida albicans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58:942–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Behrens A, Maie N, Knicker H, Kögel-Knabner I. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and PSD fragmentation as means for the analysis of condensed tannins in plant leaves and needles. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:1159–70. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00660-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newman RH, Porter LJ. Solid state 13C-NMR studies on condensed tannins. In: Hemingway RW, Laks PE, editors. Plant Polyphenols: Synthesis, Properties, Significance. Vol. 59. New York: Plenum Press; 1992. pp. 339–47. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koupai-Abyazani MR, McCallum J, Muir AD, Lees GL, Bohm BA, Towers GH, et al. Purification and characterization of a proanthocyanidin polymer from seed of alfalfa (Medicago sativa Cv. Beaver) J Agric Food Chem. 1993;41:565–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agrawal PK. The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers B.V; 1989. Carbon-13 NMR of Flavonoids. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oo CW, Kassim MJ, Pizzi A. Characterization and performance of Rhizophora apiculata mangrove polyflavonoid tannins in the adsorption of copper (II) and lead (II) Ind Crops Prod. 2009;30:152–61. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wawer I, Wolniak M, Paradowska K. Solid state NMR study of dietary fiber powders from aronia, bilberry, black currant and apple. Solid State Nucl Magn Reson. 2006;30:106–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ssnmr.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cren-Olivé C, Wieruszeski JM, Maes E, Rolando C. Catechin and epicatechin deprotonation followed by 13C-NMR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:4545–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ushirobira TM, Yamaguti E, Uemura LM, Nakamura CV, Dias FB, Mello JC. Chemical and microbiological study of extract from seeds of guaraná (Paullinia cupana var. sorbilis) Latin Am J Pharm. 2007;26:5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopes GC, Rocha JC, Almeida GC, Mello JC. Condensed tannins from the bark of Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. (Sterculiaceae) J Braz Chem Soc. 2009;20:1103–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korver O, Wilkins CK. Circular dichroism spectra of flavanols. Tetrahedron. 1971;27:5459–65. [Google Scholar]