Abstract

Our previous study revealed that the polymethoxy-flavonoids, as main components of Artemisia annua, could improve the antimalarial activity of Artemisinin. Here, we described the isolation, elucidation, constituent analysis, flavonoids enrichment of the extracts of A. annua. A total of 20 compounds were isolated including a new sesquiterpene (compound 12) and five (1, 5, 6, 7, 15) afforded for the first time from A. annua. The elucidation of eight flavonoids may be a useful phytochemical data and chemical foundation for further mechanism studies on improving the anti-malarial action of artemisinin. Furthermore, the antitumor activities of the compounds were assayed using four different kinds of human cancer cell lines.

Keywords: Antitumor activities, artemisinin, polymethoxy-flavonoid, sesquiterpene

INTRODUCTION

Artemisia annua L. (Qinghao), a traditional Chinese herb with pharmacological functions on clearances of heat and toxic materials as well as on antimalarial bioactivity, belongs to genus Artemisia (Composite family) and distributes mainly in the northern parts of Guangxi and Sichuan provinces in China. However, this plant now grows wildly in Europe and America. Phytochemical studies of A. annua revealed the presence of terpenoids, flavonoids, aliphatic hydrocarbons, aromatic ketones, aromatic acids, phenylpropanoids,[1] alkaloids and coumarins.[2]

Our previous study showed that the polymethoxy-flavonoids of A. annua had the effects on improving the antimalarial activity of artemisinin. Using liquid chromatographic tandem mass spectroscopy method for the determination of the antimalarial drug, artemisinin, in rat plasma using arteannuin B as internal standard (I.S.), the results demonstrated that different doses of CHR significantly increased the areas under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) (P < 0.01) compared with artemisinin alone and suggested that co-administration of CHR may be an efficient way to increase the anti-malarial action of artemisinin.

Here, we report the phytochemical research result of A. annua, including the isolation and elucidation of a new sesquiterpene (compound 12), together with four known sesquiterpenes (compounds 1, 2, 8 and 11), eight flavonoids (compounds 7, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19 and 20), two coumarins (compounds 3 and 6) and two acetophenones (compounds 4 and 5).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General

NMR spectra were measured with Bruker ARX-300 and ARX-600 spectrometers (Bruker Corporation, Germany), using DMSO-d6 and CDCl3 as solvent and TMS as an internal standard. HR-EST-MS was performed on Bruker micro TOF-Q mass spectrometer in m/z (rel.%) (Bruker Daltonics Inc., Germany). ESI-MS was performed on a Finnigan LCQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron, California, USA). Silica gel (200-300 mesh) and silica gel G (Qingdao Marine Chemical Group Co. Ltd, Qingdao, China) were used for column chromatography and TLC, respectively.

Extraction and Isolation

The acetone extracts of A. annua (200 g) was provided by Department of Pharmaceutics, Ningxia Medical University. Then it was subjected to HPD-100 macroporous adsorption resin and eluted with EtOH/H2O (3:2, 7:3, 4:1, 19:1) to yield 4 fractions (F1-F4), and these fractions were subjected to silica gel column chromatography (CC), Sephadex LH-20, polyamide CC, ODS CC and PHPLC to yield 20 compounds: 3α-hydroxy-1-deoxyartemisinin (1, 32.0 mg, colorless crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 3:1),[3] α-epoxy-dihydroartemisinic acid (2, 52.0 mg, colorless crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 1:1),[4] scopoletin (3, 116.0 mg, light yellow crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 2:1),[5] 4, 6-dihydroxy-2-methoxy acetophenone (4, 26.0 mg, colorless crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 3:1) (Brown, 1992),[6] 6-hydroxy-2,4-dimethoxy acetophenone (5, 17.2 mg, colorless crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 1:1) (Brown, 1992),[6] esculetin (6, 13.6 mg, light yellow crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 2:1),[5] quercetagetin-3,6,3’,4’-tetramethyl ether (7, 24.4 mg, yellow crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 2:1),[3] arteannuin M (8, 98.4 mg, colorless crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 1:1),[7] salicylic acid (9, 11.0 mg, colorless crystal in MeOH), β-sitosterol (10, 10.0 mg, white crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 10:1), artemisinin (11, 109.1 mg, colorless crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 2:1),[8] artemisilactone B (12, 42.0 mg, white crystal in MeOH), salvigenin (13, 114.2 mg, yellow crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 2:1),[9] 5,4’-dihydroxy-3,3’,7-trimethoxy flavone (14, 226.4 mg, yellow crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 2:1),[10] artemetin (15, 158.6 mg, yellow crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 4:1),[3] chrysosplenetin (16, 389.0 mg, yellow crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 2:1),[3] rutin (17, 56.5 mg, yellow crystal in MeOH), daucosterol (18, 32.1mg), 5-hydroxy-3,7,3’,4’-tetramethoxy flavone (19, 33.3 mg, yellow crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 4:1),[11] and 5-hydroxy-6,7,8,4’-tetramethoxy flavone (20, 12.0 mg, yellow crystal in CH2Cl2: MeOH 3:1).[12]

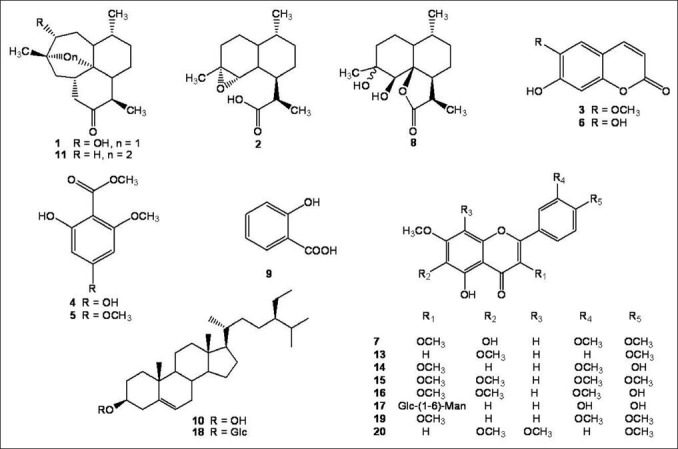

Compounds 1-8, 11-16 and 19-20 were identified by comparison of their physical and spectroscopic data (EIMS, IR, 1H and 13C NMR) with those reported in the literature [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Structures of compounds isolated from A. annua

In vitro cytotoxicity bioassay

A549, HL60, U87, DU145 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (#HB-8065, ACTT, Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (GIBCO, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Shengma Yuanheng, Beijing, China), 100 mg/L streptomycin, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 0.03% L-glutamine, and maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere.

Compounds 1-20 were resolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to make a stock solution. The DMSO concentration was kept below 0.10% throughout the cell culture period and did not exert any detectable effect on cell growth or cell death. The Hela, MCF-7 and HepG2 cells were incubated at 6 × 103 cells/well in 96-well plates, respectively. The cells were incubated with the five compounds at 1, 10, 50, 100 μM for 48 hours. Cell growth was measured by a 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. The percentage of cell growth inhibition was calculated as follows:

Cell growth inhibition (%) = [A490(control) - A490(compound)]/[ A490(control)] × 100

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

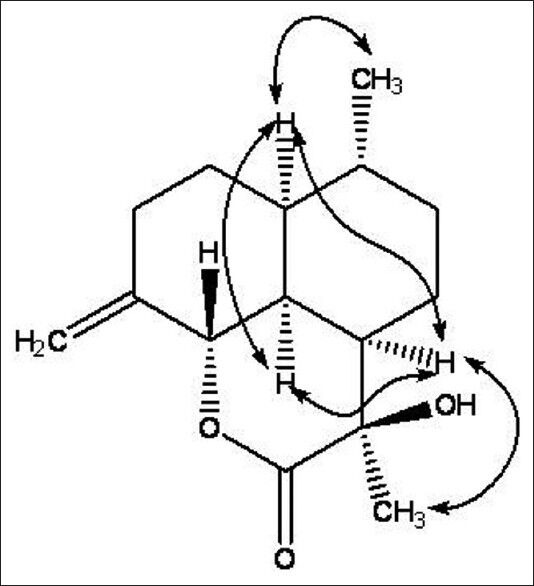

Compound 12 was obtained as a white crystal (MeOH). The molecular formula was established as C15H22O3 on the basis of ion peaks at m/z 273.1466 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C15H22O3Na, 273.1466) and 251.1640 [M + H]+ (calcd. for C15H23O3, 251.1646) in the HR-ESI-MS, with the help of NMR spectra. Its IR spectra showed absorption bands for hydroxyl groups (3427 cm-1), -CH2- (2921 cm-1), a terminal double bond (1630 cm-1) and a six-membered ring lactones unit (1720 cm-1). In the 1H NMR spectrum of 12 [Table 1], two methyl groups at δ 1.53 and δ 0.91 (3H, d, J = 5.4 Hz), a O-bearing methylidyne group at δ 4.47 (1H, d, J = 12.0 Hz), one pair of olefinic proton signals at δ 4.88/4.73, were observed. The 13C NMR spectrum [Table 1] of 12 showed 15 carbon signals that could be assigned to the sesquiterpene moiety. A lactone carbonyl (δ 175.1), a pair of olefinic signals with exo-cyclic double bond at δ 147.8 (101.9), which were assigned C-4 (15), three tertiary carbon signals at δ 49.0/46.2/41.4, a O-bearing tertiary carbon signal at δ 79.3 and a O-bearing quaternary carbon signal at δ 87.8, were observed in the 13C NMR spectrum of 12. Thus, these data above allowed the skeleton of 12 to be deduced as a cadinanolide-type sesquiterpene derivative. Furthermore, an examination of the 2D-NMR spectra (HMQC, HMBC) of 12 indicated that it was similar to artemisilactone,[13] but differed from artemisilactone at C-11 and C-4 [Table 1 and Figure 2]. The HMBC experiment showed 1H/13C correlations between H-15 and C-3, C-5, between H-14 and C-1, C-9, and between H-13 and C-7, C-12. Because the H-C (1), H-C (6) and 14-Me of cadinanolide-type are defined in the α-configuration, H-C (5) is defined in the β-configuration. Additionally, the NOESY experiment showed correlations between H-1 and H-2, 6, 7, 9, 14, H-5 and H-2, 3, 8, 10, H-6 and H-1, 2, 7, 13, H-7 and H-1, 6, 8, 9, 13, H-13 and H-7, H-14 and H-1, 2, 9, 10. So 7-H and 13-Me were defined as α-configuration and 13-OH was defined as β-configuration. As a result, those elucidation allowed the structure of compound 12 [Figure 2] to be deduced.

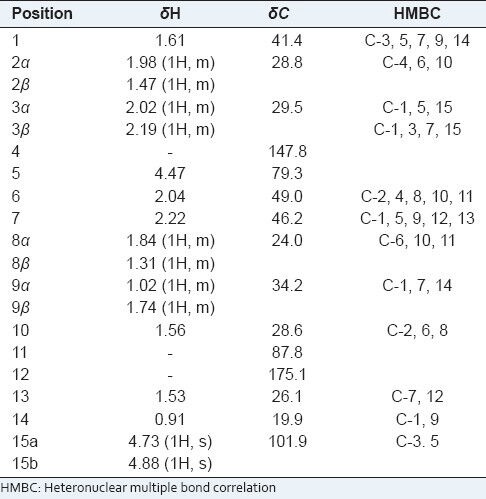

Table 1.

The 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectroscopic data and HMBC correlations of compound 12 (300 MHz for 1H; 75 MHz for 13C, CDCl3)

Figure 2.

Key NOESY correlations of compound 12

Using A549, HL60, U87 and DU145 cell lines, the antitumor activities of compounds 1-20 were evaluated in vitro. Compounds 16 showed significant cytotoxic activities against the A549, HL60 and U87 cell lines with IC50 value at 15.76, 13.65 and 22.37 μM, respectively. Compounds 4 and 5 exhibited moderate antitumor activities against HL60 cell line with an IC50 value at 84.07 and 50.60 µM.

CONCLUSION

The finding of the new sesquiterpene (compound 12) will provide reference for the taxonomy of A. annua, and the flavonoids may be a useful phytochemical data and chemical foundation for further mechanism studies on improving the anti-malarial action of artemisinin. Furthermore, the characteristic constituent 16, polymethoxy substituted flavonoid, is a potential antitumor agent.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This work was supported by Liaoning Province Innovation Project of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2001-lnzyxzk-07)

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown GD. The Biosynthesis of Artemisinin and the Phytochemistry of Artemisia annua L. Molecules. 2010;15:7603–98. doi: 10.3390/molecules15117603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhakuni RS, Jain DC, Sharma RP, Kumar S. Secondary metabolites of Artemisia annua and their biological activity. Curr Sci. 2001;80:35–48. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J, Zhou YB, Zhang X, Huang L, Sun W, Wang JH. Cemical constituents of Artemisia annua L. J Shenyang Pharm Univ. 2008;25:866–70. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sy LK, Zhu NY, Brown GD. Syntheses of dihydroartemisinic acid and dihydro-epi-deoxyarteannuin B incoroprating a stable isotope label at the 15-position for studies into the biosynthesis of artemisinin. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:8495. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiao W, Li N, Ni H, Li X, Qing DG, Jia XG. Isolation and identification of chemical constituents from the whole plant of Hibiscus trionum L. J Shenyang Pharm Univ. 2009;26:782–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown GD. Two New Compounds from Artemisia annua. J Nat Prod. 1992;55:1756–60. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sy LK, Brown GD. A novel endoperoxide and related sesquiterpenes from Artemisia annua which are possibly derived from allylic hydroperoxides. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:4345–56. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang JJ, Nicholls KM, Chen CH, Wang Y. Two-Dimensional NMR Studies of Arteannuin. Acta Chim Sin. 1987;45:305–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zou JH, Yang JS. Cemical constituents of Trollius ledebouri Reicb. Chin Pharm J. 2005;40:731–2. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang GE, Bao L, Zhang XQ, Wang Y, Li Q, Zhang WK, et al. Studies on flavonoids and their antioxidant activities of Artemisia annua. J Chin Med Mater. 2009;32:1683–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao JQ, Dang Q, Fu HW, Yao Y, Pei YH. Isolation and identification of chemical constituents from Blumea riparia DC. J Shenyang Pharm Univ. 2007;24:615–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang QA, Wu Z, Liu L, Zou LH, Luo M. Synthesis of citrus bioactive polymethoxyflavonoids and flavonoid glucosides. Chin J Org Chem. 2010;30:1682. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu DY, Deng DA, Zhang SG, Xu RS. Structure of artemisilactone. Acta Chim Sin. 1984;42:937–9. [Google Scholar]