Abstract

Background

Because classical pneumococcal serotyping cannot distinguish between serotypes 6A and 6C, the effects of pneumococcal vaccines against serotype 6C are unknown. Pneumococcal vaccines contain 6B, but do not contain 6A and 6C.

Methods

We used a phagocytic killing assay to estimate the immunogenicity of 7-valent conjugate vaccine (PCV7) in children and 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23) in adults against serotypes 6A and 6C. We evaluated trends in invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) caused by serotypes 6A and 6C using active surveillance in the U.S.

Results

Sera from PCV7-immunized children had median opsonization indices of 150 and <20 for serotypes 6A and 6C, respectively. Similarly, only 52% (25/48) of adults vaccinated with PPV23 showed opsonic indices greater than 20 against serotype 6C. During 1999–2006, the incidence (cases per 100,000) of serotype 6A IPD declined from 4.9 to 0.46 (−91%, P<0.05) among children aged <5 years, and from 0.86 to 0.36 (−58%, P<0.05) among persons aged ≥5 years. Although incidence of 6C IPD showed no consistent trend (range 0–0.6) among <5 year-olds, it increased from 0.25 to 0.62 (P<0.05) among persons aged ≥5 years.

Conclusions

PCV7 introduction has led to reductions in serotype 6A IPD, but not serotype 6C IPD in the U.S.

Keywords: Pneumococcus, vaccine, cross-protection, serotype, herd immunity

INTRODUCTION

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a common cause of pneumonia, bacteremia, meningitis, and otitis media. Two different pneumococcal vaccines are currently used in the U.S.: a 23-valent polysaccharide (PS) vaccine (PPV23) has been used in adults since 1983, and a 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7, Prevnar) has been used for young children since 2000 [1]. These vaccines elicit polysaccharide-capsule-specific antibodies that provide serotype-specific protection by opsonizing pneumococci for phagocytes. PCV7 has been highly effective in young children, among whom it has dramatically reduced the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) [2–4]. PCV7 has also provided strong herd immunity by reducing the incidence of IPD among unvaccinated children and adults [3, 5, 6].

While recently observed reductions in IPD are largely attributable to reductions in IPD caused by the serotypes included in PCV7, it was hoped that PCV7 would also reduce the incidence of IPD caused by serologically related pneumococcal serotypes. For instance, PCV7 contains 6B and 19F capsular PSs but not the related 6A and 19A PSs. However, studies have shown that PCV7 does not provide cross-protection against serotype 19A [6, 7] and that the incidence of IPD caused by serotype 19A has increased dramatically since 2000 [6, 8, 9]. In contrast, most [10–12] but not all [13] studies have found that PCV7 and similar conjugate vaccines do provide cross-protection against serotype 6A.

Recently, we reported a new pneumococcal serotype, which we named 6C for its serologic similarities to serotype 6A [14]. Classical serotyping methods do not distinguish between 6A and 6C [15], but recent retrospective work has shown that serotype 6C has circulated for more than 25 years [16]. Serotype 6C is both genetically and biochemically different from serotypes 6A and 6B [14, 16]. In view of these findings, we investigated the impact of pneumococcal vaccines on the 6A/6C serotypes by determining the prevalence of the 6A and 6C serotypes among IPD isolates and the capacity of sera from vaccinees to opsonize 6A and 6C serotypes in vitro.

METHODS

Serum samples from children for serologic studies

The serum samples used were from 19 children (from one of two large private pediatric practices in southeastern Massachusetts) who 1) were born between 7/3/1999 and 7/2/2003, 2) participated in a prospective study of nasopharyngeal colonization, 3) were identified as having been colonized with S. pneumoniae on at least one occasion without having had invasive pneumococcal disease, and 4) received three or four doses of PCV7. The children’s vaccination status was confirmed from pediatric provider records. The children were between 39 to 86 months old at the time of serum collection. The study was approved by the Boston University Medical Campus institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from a parent or guardian of each subject.

Serum samples from older adults for serologic studies

The older subjects were medically stable, community-dwelling adults ≥65 years of age who were participants in an IRB-approved clinical trial comparing 9-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV9) (Wyeth, Pearl River, NY) with PPV23 (Merck, West Point, PA). Only the subjects immunized with PPV23 were described in this report and were recruited in Rochester, NY, and Cincinnati, OH. Peripheral blood samples were obtained from the subjects 1 month after their PPV23 vaccinations. Approximately half of the subjects had previously received PPV23. Serum was obtained from the blood samples, and the serum samples were kept frozen until analysis.

Opsonophagocytosis assay

The opsonic capacity of the serum samples was determined using the killing-type opsonization assay, which is currently accepted as the reference method [17] and was previously described in detail [18]. Differentiated HL-60 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were used as phagocytes, and baby rabbit sera (Pel-Freez, Rogers, AK) were used as the complement source. To eliminate clonal differences, isogenic target bacteria were prepared by inserting 6A, 6B, and 6C capsule gene loci into a TIGR4 background, as previously described [16]. The opsonization index is defined as the serum dilution that kills 50% of the target bacteria. Since all sera were diluted 5-fold before the assay and diluted 4 fold during the assay, the minimum detectable opsonization index was 20.

Population Surveillance for invasive pneumococcal disease

Cases of IPD were defined by the isolation of pneumococci from a normally sterile site among residents of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) areas [19]. Trends over time in the incidence of IPD caused by serotype 6C were evaluated by comparing rates in 2006 with rates in 1999 (pre-PCV7 baseline period) for areas under continuous surveillance, which included all of Connecticut and selected counties in California, Georgia, Maryland, New York, Oregon, and Tennessee. The total population in 2006 for these continuous surveillance areas was 17,922,545 persons (1,189,369 children <5 years old), according to 2006 post-census population estimates.

Serotyping

Pneumococcal isolates available from IPD cases occurring in 1999 and 2003–2006 in ABCs sites were serotyped by CDC. Those isolates were initially serotyped at the CDC by the quellung reaction, which classifies serotype 6C as “6A.” All available isolates serotyped as “6A” were sent to the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) to distinguish between the 6A and 6C serotypes using two different monoclonal antibodies: Hyp6AG1 and Hyp6AM3 [14].

Susceptibility testing

Susceptibility testing was performed using broth microdilution according to the 2007 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines [20]. Susceptibility testing was performed for penicillin G, erythromycin, cefotaxime, and levofloxacin at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, San Antonio and at CDC.

Statistical analysis

Because not all cases identified by ABCs from 1999 and 2003–2006 had isolates available for serotyping, we assumed that the serotype distribution among cases without isolates was similar to that of cases with isolates, adjusting for age. We evaluated trends over time in the incidence of IPD caused by serotype 6C by comparing rates in 2006 with rates in 1999 using the chi-square method or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. For all analyses, p-values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Trends in incidence of serotypes 6A and 6C following PCV7 introduction

During 1999 and 2003–2006, a total of 13,907 cases of IPD were identified through ABCs; 12,219 (88%) of these isolates were available for serotyping. Of these, classical serotyping showed that 778 (6.4%) were serotype 6A and 752 (97%) of those were available for further characterization. Of these 752 isolates, monoclonal antibody typing confirmed that 486 (65%) were serotype 6A and the remaining 266 (35%) were serotype 6C.

Among children aged <5 years, we found no serotype 6C cases among the 42 classically serotyped 6A cases during 1999, the pre-PCV7 period (Table 1). During 2003–2006, the incidence of serotype 6A IPD among children aged <5 years declined steadily, and, by 2006, it had declined by 91% (95% CI −97, −78) (Table 1). We identified only 13 cases of serotype 6C IPD among children <5 years of age during the entire observation period and did not observe a consistent trend in the incidence of serotype 6C IPD among children. Among adults and children aged ≥5 years, serotype 6A IPD declined by 58% (95% CI −69, −43) between 1999 and 2006. The rate of IPD caused by serotype 6C in this age group increased by 158% (95% CI 77–274); the absolute rate increased from 0.25 to 0.62 cases per 100,000.

Table 1.

Incidence (number) of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) caused by serotypes 6A and 6C in selected U.S. sites in 1999 and 2003–2006

| Year | Serotype 6A | Serotype 6C | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 1999 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | |

| <5 years of age | 4.9* (42) | 2.0 (19) | 0.23 (2) | 0.34 (3) | 0.46 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.10 (1) | 0.70 (6) | 0 (0) | 0.55 (6) |

| ≥5 years of age | 0.86 (111) | 0.88 (118) | 0.57 (80) | 0.40 (57) | 0.36 (49) | 0.25 (32) | 0.29 (40) | 0.29 (41) | 0.37 (53) | 0.62 (87) |

Incidence indicates the number of cases per 100,000 persons.

Susceptibility to antimicrobials by serotypes 6A and 6C pneumococcal isolates

All of the 486 serotype 6A isolates and 265 of the 266 serotype 6C isolates were tested for their susceptibility to four antimicrobials. A significantly higher percentage of 6C than 6A isolates was susceptible to penicillin (71% vs. 51%). Among persons 5 years of age and older, the rate IPD caused by penicillin-nonsusceptible serotype 6C increased from 0.03 cases to 0.24 cases per 100,000 (p<0.02). Also, 70% of the 6C isolates were susceptible to erythromycin compared with 50% of the 6A isolates (Table 2). With respect to cefotaxime and levofloxacin, both 6A and 6C isolates were almost uniformly susceptible.

Table 2.

Percentage (number) of serotype 6A and 6C IPD isolates susceptible, intermediate, and resistant to indicated antibiotics in selected U.S. sites, 1999 and 2003–2006

| Antibiotics | Serotype 6A n=486 isolates |

Serotype 6C n=265 isolates |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant | Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant | P-value* | |

| Penicillin | 51 (246) | 33 (162) | 16 (78) | 71 (188) | 28 (73) | 2 (4) | <0.0001 |

| Erythromycin | 50 (245) | 0 (0) | 50 (241) | 70 (186) | 1 (2) | 29 (77) | <0.0001 |

| Cefotaxime | 97 (474) | 2 (10) | 0.4 (2) | 99 (264) | 0.4 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.11 |

| Levofloxacin | 99 (484) | -- | 0.4 (2) | 100 (265) | -- | 0 (0) | 0.3 |

Chi-square test for difference in distribution of susceptible, intermediate, and resistant strains among serotype 6A versus 6C cases

Immunologic effects of pneumococcal vaccines against serotypes 6A and 6C

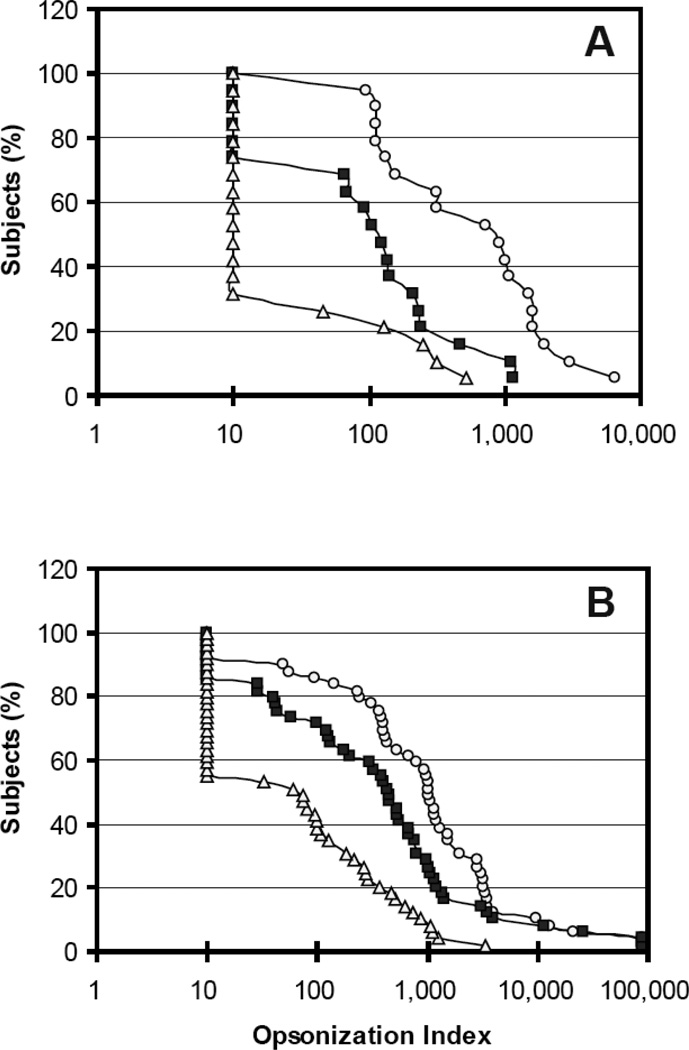

Since anti-capsule antibodies provide protection by opsonizing pneumococci, serum samples from PCV7-vaccinated children were examined for their ability to opsonize pneumococci expressing serotypes 6A, 6B, and 6C in vitro (Figure 1A). Opsonic indices against serotype 6B were high; sera from almost all children (18/19) had opsonization indices greater than 20, and the median of their opsonization indices was 1000. Although the opsonic indices against serotype 6A were less than those against serotype 6B, the children had a significant capacity to opsonize serotype 6A. Thirteen (68%) of 19 children had opsonic indices against 6A greater than 20, with this 6A response (13/19) not being significantly different from the 6B response (18/19) (p=0.09 by Fisher’s exact test), and the median of their opsonization indices against serotype 6A was about 150 (p=0.0002 for 6B vs. 6A medians {1000 vs 150} by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test). In contrast, the children had very little capacity to opsonize 6C: only 26% of children (5/19) had opsonic indices against 6C greater than 20. The proportions of sera with opsonization indices ≥20 differed significantly for 6A and 6C (13/19 vs. 5/19, p<0.03 by Fisher’s exact test), and even more so for 6B and 6C (18/19 vs. 5/19, p<0.00003 by Fisher’s exact test). Also, the median opsonization index (<20) for serotype 6C was 10–100 fold less than those for serotype 6A and 6B (p<0.0002 for 6A vs. 6C medians and p<0.0002 for 6B vs. 6C medians by Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Figure 1.

Reverse cumulative distribution curve of opsonization indices for serotypes 6A (solid square), 6B (open circle), and 6C (open triangle) obtained with sera from children immunized with PCV7 (panel A) or older adults immunized with PPV23 (panel B). The X axis shows the opsonic index, and the Y axis shows the percentage of persons with opsonic indices greater than value shown on the X axis. The detection limit of the assay was 20, and samples with undetectable opsonic indices were assigned an opsonic index of 10.

Sera from adults immunized with PPV23 showed response patterns (Figure 1B) similar to those of the children; almost all adults had opsonic indices >20 against serotypes 6A or 6B (81% {42/48} for 6A, 87.5% {39/48} for 6B), but only 52% (25/48) of adults showed opsonic indices >20 against serotype 6C (p<0.0002 for 6B vs 6C or p<0.005 6A vs 6C by Fisher’s exact test). When the median responses were compared, PPV23 elicited strong responses to 6B (median=967) and 6A (median=401) serotypes; the 6B response was about 2 fold bigger than the 6A response (Figure 1B) (p<0.0001 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test). However, the median response to 6C (median=26) was low and was significantly less than that to either 6A or 6B (p<0.0001 by Wilcoxon signed-rank test). These results suggest that the two currently available pneumococcal vaccines, both of which contain the serotype 6B capsule, elicit significant cross-opsonic antibodies to 6A but not to 6C.

DISCUSSION

PCV7 was introduced into the U.S. routine childhood vaccination program in 2000. To estimate the population-level effects of PCV7 on IPD caused by serotypes 6A and 6C, we evaluated rates of IPD during 1999 and 2003–2006. We found that in children under 5 years old (the population targeted for PCV7 vaccination), rates of 6A IPD declined markedly. Few cases of 6C IPD cases occurred among children, indicating no clear trend after PCV7 introduction. Among older children and adults, we observed both a reduction in the incidence of serotype 6A IPD and an increase in the incidence of serotype 6C IPD of similar magnitude (Table 1). These findings suggest that, at the population level, PCV7 provides cross-protection against 6A but not against 6C.

This conclusion is further supported by the in vitro opsonization studies. The protective effect of pneumococcal vaccine has been associated with the capacity of anti-capsule antibodies to opsonize pneumococci in vitro [21]. We found that high percentages (70% and 95%) of PCV7-vaccinated children have opsonic indices greater than 20 against serotypes 6A and 6B. These opsonic indices should be sufficient to protect young children [21]. However, against serotype 6C, only 26% (5/19) of the vaccinated children had opsonic indices greater than 20. Furthermore, their median opsonic index against serotype 6C was 10–100 fold less than their median opsonic indices against serotypes 6A and 6B. Similar observations were shown with adults in response to a routinely used 23-valent PS vaccine. Thus, the in vitro opsonization studies also suggest that currently available pneumococcal vaccines provide little or no protection against serotype 6C.

Since the introduction of PCV7, the incidence of IPD caused by a few non-PCV7 serotypes has increased significantly [6, 22, 23]. Such increases have been most evident for serotype 19A, which accounted for 2.5% of IPD cases in children before 2000 and 36% of IPD cases in 2005 [24]. Rates of IPD caused by serotype 19A increased from 2.6 cases per 100,000 among children <5 years-old before PCV7 introduction to 8.9 cases per 100,000 in 2005 [6, 9]. The incidence of serotype 6C among children <5 years-old and among older children and adults is less than that of serotype 19A but, similar to serotype 19A, serotype 6C has increased 2.5-fold from 1999 to 2006 among persons ≥5 years old (Table 1). Whether this increase in 6C is causally associated with the introduction of PCV7 is unclear. A trend toward an increase in the incidence of serotype 19A has been observed in association with antibiotic-resistant and susceptible pneumococcal clones [9, 25] and in the presence and absence of PCV7 [25, 26]

The difference in vaccine-induced cross-protection against serotypes 6A and 6C may reflect the presence of just one structural difference (rhamnose-ribitol linkage) between 6A and 6B PS but of two structural differences (rhamnose-ribitol linkage and glucose/galactose substitution) between 6C and 6B PS. However, the induction of cross-protective antibodies depends upon the exact methods used to conjugate PS to protein [27]. Also, a pneumococcal vaccine already under development that contains 6A PS [28] may provide sufficient protection against serotype 6C as 6A PS elicits antibodies cross-reactive with 6C in animals [15]. Consequently, pneumococcal conjugate vaccines may vary in their abilities to protect against serotypes 6A, 6B, and 6C.

Another striking observation with PCV7 is its indirect protective effect on unvaccinated populations. Presumably, this occurs because PCV7 reduces nasopharyngeal colonization with pneumococci and subsequent transmission. This indirect effect, or herd immunity, has not been evident for serotype 6A [6, 29]. Our results suggest that this apparent lack of indirect cross-protection against serotype 6A among unvaccinated persons can be explained by the inability of classical serotyping to distinguish serotypes 6A and 6C. Using our monoclonal antibody assay, we observed a reduction in the incidence of serotype 6A IPD among older children and adults concomitant with a nearly equivalent increase in the incidence of serotype 6C IPD, the net effect of which was no change in the incidence of IPD caused by classically serotyped 6A.

In considering cross-protection, one generally evaluates the production of cross-reactive antibodies but does not evaluate the presence of unidentified subtypes within the pneumococci of the cross-reactive serotype. Our experience with serotype 6C shows that the latter possibility must be considered. The presence of 6C might explain inconsistent findings by investigators evaluating the cross-protection to 6A among young children. Vaccine trials from Israel and Finland reported cross-protection [10–12], but a study from South Africa did not find such cross-protection [13]. A recent study performed with children (<18 years) in Philadelphia, PA suggested an increase in the incidence of serotype 6A since the introduction of PCV7 [8]. The ambiguity may have arisen from the relatively small number of children evaluated in these studies. Alternatively, we speculate that serotype 6C might have been more prevalent in South Africa than in Europe (or in Philadelphia than in other parts of the US) and these studies identified serotype 6C as “6A”, resulting in ambiguity in cross-protection due to the failure to distinguish between 6C and 6A. Indeed a recent abstract reported the presence of 6C in S. Africa [30]. Distinguishing serotype 6C from 6A is essential if cross-protection is to be measured precisely.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Delois Jackson and her team at the CDC for serotyping pneumococci for the ABCs program and Dr. Genevieve Barkocy-Gallagher at the Streptococcus Laboratory of the CDC for organizing isolate shipment. We also acknowledge Dr. James Jorgensen for conducting pneumococcal susceptibility testing.

This work was funded by NIH AI-30021 (MHN), N01-AI-45248 (JJT), and AI-31473 (MHN), CDC’s Emerging Infections Program and CDC’s Antimicrobial Resistance Working Group, CDC K01 CI000301-01 (BEM).

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest

Moon H. Nahm: University of Alabama at Birmingham has applied for a patent covering the discovery of the 6C serotype.

References

- 1.Preventing pneumococcal disease among infants and young children: recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR. 2000;49:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shinefield HR, Black S. Efficacy of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in large scale field trials. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:394–397. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200004000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J, et al. Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1737–1746. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Invasive pneumococcal disease in children 5 years after conjugate vaccine introduction - eight states, 1998–2005. MMWR. 2008;57:144–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lexau CA, Lynfield R, Danila R, et al. Changing epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease among older adults in the era of pediatric pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Jama. 2005;294:2043–2051. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hicks LA, Harrison LH, Flannery B, et al. Incidence of pneumococcal disease due to non-pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) serotypes in the United States during the era of widespread PCV7 vaccination, 1998–2004. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1346–1354. doi: 10.1086/521626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitney CG, Pilishvili T, Farley MM, et al. Effectiveness of seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease: a matched case-control study. Lancet. 2006;368:1495–1502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69637-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steenhoff AP, Shah SS, Ratner AJ, Patil SM, McGowan KL. Emergence of vaccine-related pneumococcal serotypes as a cause of bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:907–914. doi: 10.1086/500941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore MR, Gertz RE, Jr, Woodbury RL, et al. Population snapshot of emergent Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 19A in the United States, 2005. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1016–1027. doi: 10.1086/528996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dagan R, Melamed R, Muallem M, et al. Reduction of nasopharyngeal carriage of pneumococci during the second year of life by a heptavalent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1996;174:1271–1278. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.6.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dagan R, Givon-Lavi N, Zamir O, et al. Reduction of nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae after administration of a 9-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to toddlers attending day care centers. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:927–936. doi: 10.1086/339525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eskola J, Kilpi T, Palmu A, et al. Efficacy of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against acute otitis media. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344(6):403–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mbelle N, Huebner RE, Wasas AD, Kimura A, Chang I, Klugman KP. Immunogenicity and impact on nasopharyngeal carriage of a nonavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1171–1176. doi: 10.1086/315009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park IH, Pritchard DG, Cartee R, Brandao A, Brandileone MC, Nahm MH. Discovery of a new capsular serotype (6C) within serogroup 6 of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:1225–1233. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02199-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin J, Kaltoft MS, Brandao AP, et al. Validation of a multiplex pneumococcal serotyping assay with clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:383–388. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.383-388.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park IH, Park S, Hollingshead SK, Nahm MH. Genetic basis for the new pneumococcal serotype, 6C. Infect Immun. 2007;75:4482–4489. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00510-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romero-Steiner S, Frasch CE, Carlone G, Fleck RA, Goldblatt D, Nahm MH. Use of opsonophagocytosis for the serological evaluation of pneumococcal vaccines. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:165–169. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.2.165-169.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burton RL, Nahm MH. Development and validation of a fourfold multiplexed opsonization assay (MOPA4) for pneumococcal antibodies. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:1004–1009. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00112-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kyaw MH, Lynfield R, Schaffner W, et al. Effect of introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1455–1463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: sixteenth informational supplement. Approved standard M100-S17. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2007. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jodar L, Butler JC, Carlone G, et al. Serological criteria for evaluation and licensure of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine formultions for use in infants. Vaccine. 2003;21:3265–3272. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pai R, Moore MR, Pilishvili T, Gertz RE, Whitney CG, Beall B. Postvaccine genetic structure of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 19A from children in the United States. J. Infect. Dis. 2005;192:1988–1995. doi: 10.1086/498043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzalez BE, Hulten KG, Lamberth L, Kaplan SL, Mason EO., Jr Streptococcus pneumoniae serogroups 15 and 33: an increasing cause of pneumococcal infections in children in the United States after the introduction of the pneumococcal 7-valent conjugate vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:301–305. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000207484.52850.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beall B. Vaccination with the pneumococcal 7-valent conjugate: a successful experiment but the species is adapting. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2007;6:297–300. doi: 10.1586/14760584.6.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi EH, Kim SH, Eun BW, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 19A in Children, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:275–281. doi: 10.3201/eid1402.070807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dagan R, Givon-Lavi N, Leibovitz E. Increased importance of antibiotic-resistant (AR) S. pneumoniae serotype 19A (Pn19A) in Acute Otitis Media (AOM) occurring before introduction of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) in southern Israel. Abstracts of the 47th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Vol. Abstract C-1001; Chicago: Washington, DC USA. American Society for Microbiology; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu X, Gray B, Chang SJ, Ward JI, Edwards KM, Nahm MH. Immunity to cross-reactive serotypes induced by pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in infants. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1569–1576. doi: 10.1086/315096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott DA, Komjathy SF, Hu BT, et al. Phase 1 trial of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in healthy adults. Vaccine. 2007;25:6164–6166. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haber M, Barskey A, Baughman W, et al. Herd immunity and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: a quantitative model. Vaccine. 2007;25:5390–5398. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.04.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hattingh O. Abstracts of 6th International Symposium on Pneumococci and Pneumococcal Diseases. Reykjavik, Iceland: 2008. Jun 8–12, Detection of Serotype 6C among South African Serotype 6A Pneumococci causing Invasive Disease, 2005–2006; p. 187. 2008; Abstract P2-002. [Google Scholar]