Abstract

The activity-regulated gene expression of transcription factors is required for neural plasticity and function in response to neuronal stimulation. T-brain-1 (TBR1), a critical neuron-specific transcription factor for forebrain development, has been recognized as a high-confidence risk gene for autism spectrum disorders. Here, we show that in addition to its role in brain development, Tbr1 responds to neuronal activation and further modulates the Grin2b expression in adult brains and mature neurons. The expression levels of Tbr1 were investigated using both immunostaining and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analyses. We found that the mRNA and protein expression levels of Tbr1 are induced by excitatory synaptic transmission driven by bicuculline or glutamate treatment in cultured mature neurons. The upregulation of Tbr1 expression requires the activation of both α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid (AMPA) and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. Furthermore, behavioral training triggers Tbr1 induction in the adult mouse brain. The elevation of Tbr1 expression is associated with Grin2b upregulation in both mature neurons and adult brains. Using Tbr1-deficient neurons, we further demonstrated that TBR1 is required for the induction of Grin2b upon neuronal activation. Taken together with the previous studies showing that TBR1 binds the Grin2b promoter and controls expression of luciferase reporter driven by Grin2b promoter, the evidence suggests that TBR1 directly controls Grin2b expression in mature neurons. We also found that the addition of the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) antagonist KN-93, but not the calcium-dependent phosphatase calcineurin antagonist cyclosporin A, to cultured mature neurons noticeably inhibited Tbr1 induction, indicating that neuronal activation upregulates Tbr1 expression in a CaMKII-dependent manner. In conclusion, our study suggests that Tbr1 plays an important role in adult mouse brains in response to neuronal activation to modulate the activity-regulated gene transcription required for neural plasticity.

Keywords: autism, Grin2b, immediate early gene, neuronal activation, Tbr1

INTRODUCTION

Neuronal activation regulates the activity of transcription factors to modulate the gene expression required for the formation of mature synapses and neural circuits and development of cognitive function (Parkes and Westbrook, 2011). Abnormalities in activity-regulated transcriptional pathways have been implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders (Pfeiffer et al., 2010; King et al., 2013), especially in autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), which are characterized by deficits in social interaction and communication, cognitive inflexibility, repetitive behaviors, and intellectual disability. Recent genetic studies have found recurrent mutations of T-brain-1 (TBR1), encoding a brain-specific T-box transcription factor (Bulfone et al., 1995), in ASD patients and identified Tbr1 as a causative gene in ASDs (Neale et al., 2012; O’Roak et al., 2012a; Huang et al., 2014).

Tbr1 is specifically expressed in the olfactory bulb, cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala (Bulfone et al., 1995, 1998; Medina et al., 2004; Remedios et al., 2007). Its peak expression is observed during the embryonic stage, and the expression gradually decreases after birth (Bulfone et al., 1995). TBR1 protein is expressed at low, but significant, levels in the adult forebrain (Hsueh et al., 2000). At the embryonic stage, Tbr1, which is abundantly expressed in post-mitotic projection neurons, controls the axonal connections between the cerebral cortex and thalamus and the formation of the corticospinal tract (Hevner et al., 2001). Studies using knockout mice demonstrated that Tbr1 plays important roles in the maintenance of neuronal projections in the olfactory bulb (Bulfone et al., 1998), layer and regional identification of the neocortex (Hevner et al., 2001; Bedogni et al., 2010), and migration of the amygdala (Remedios et al., 2007). Moreover, we recently showed that TBR1 modulates expression of Ntng1, Cdh8, and Cntn2 and regulates the axonal outgrowth of amygdalar neurons, which are critical for the inter- and intra-amygdalar connections (Huang et al., 2014). All of these studies indicate that Tbr1 is significantly involved in brain development.

Our previous studies showed that TBR1 interacts with CASK (calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine protein kinase; Hsueh et al., 2000; Hsueh, 2009). Mutations in the CASK gene result in X-linked mental retardation (Najm et al., 2008; Tarpey et al., 2009; Moog et al., 2011). The CASK-TBR1 protein complex regulates the expression of glutamate receptor, ionotropic, N-methyl-D-aspartate 2B (Grin2b, also known as Nmdar2b; Wang et al., 2004a,b), which is critical for learning and memory and involved in autism and schizophrenia (Kristiansen et al., 2010; O’Roak et al., 2012b). Recently, we demonstrated that Tbr1-deficient mice exhibit autistic-like behaviors (Huang et al., 2014). Upon behavioral stimulation, the induction of Grin2b expression was impaired in Tbr1 heterozygous mice, indicating that Tbr1 is likely required for the induction of Grin2b upon neuronal activation. Thus, in addition to regulating neuronal development, Tbr1 likely responds to neuronal activation and controls Grin2b expression in adult brains.

In literatures, neuronal activation-induced immediate early gene (IEG) responses have been demonstrated to be relevant to dysfunction of glutamatergic pathways and psychological stress. First of all, stress-induced dysregulation in glutamate transmission contributes to development of schizophrenia and other mood disorders (de Kloet et al., 2005; Popoli et al., 2012; Weickert et al., 2013), indicating glutamatergic system has a strong impact on psychiatric disorders. Moreover, acute stress elevates the glucocorticoid levels and activates glucocorticoid receptor, a ligand-inducible nuclear transcription factor, to induce an increase of presynaptic SNARE complexes and thus further enhance glutamate release (Popoli et al., 2012). At the post-synaptic sites, acute stressful conditions induce expression of a series of IEGs, including early growth response 1 (Egr1) and activity-regulated cytoskeletal-associated protein (Arc), and change α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid (AMPA)/N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-mediated glutamatergic transmission. It then impacts on neuronal activation-dependent synaptic plasticity (Revest et al., 2005; Fumagalli et al., 2011; Benekareddy et al., 2013). Besides, both acute behavioral stress in live animals and corticosterone treatment in brain slices increase the synaptic expressions and function of NMDA and AMPA receptors through the upregulation of serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase (SGK), another IEG, and activation of RAB4, a regulator for endocytic recycling of receptors (Yuen et al., 2011). All of these studies support that psychological stress influences the activity-mediated glutamatergic transmission and activates or regulates the downstream genes via IEGs. Since Tbr1 has been shown to directly regulate the expression of Grin2b and Tbr1 plays roles in psychiatric disorders, Tbr1 is a likely candidate that senses the neuronal stimulations and regulates glutamatergic pathways.

In this report, we demonstrate that neuronal activation in mature cultured neurons and behavioral stimulation in adult mice indeed upregulate the expression of Tbr1 and that the elevation of TBR1 can further induce Grin2b expression. We also found that activity-dependent Tbr1 expression is regulated via the NMDA receptor and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII)-mediated signaling, suggesting a positive feedback loop to control neuronal activity via TBR1 and NMDAR. Our study provides evidence that Tbr1 also plays a role in the response of mature neurons to neuronal activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

ANIMALS

Tbr1+/- mice were originally provided by Dr. Robert Hevner (Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle) with the permission of Dr. John Rubenstein (Department of Psychiatry, University of California at San Francisco; Hevner et al., 2001). The mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free temperature- and humidity-controlled facility at the Institute of Molecular Biology, Academia Sinica, and backcrossed into a C57BL/6 background for over 20 generations. Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the National Laboratory Animal Center, Taiwan. All animal experiments were conducted with the approval of the Academia Sinica Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee, and in strict accordance with its guidelines and those of the Council of Agriculture Guidebook for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

ANTIBODIES AND CHEMICALS

The rabbit polyclonal TBR1 antibody (TBRC) has been described previously (Hsueh et al., 2000). The mouse monoclonal MAP2 antibody was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The Alexa Fluor® 488- and Alexa Fluor® 555-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen. The following drugs were used: glutamate was purchased from Invitrogen; tetrodotoxin (TTX), bicuculline, 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo(f)quinoxaline (NBQX) and NMDA were obtained from Tocris Bioscience; DL-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (AP5), cyclosporin A (CsA) and KN-93 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

PRIMARY CULTURED NEURONS

The hippocampal and amygdalar neurons from postnatal day 1 (P1) mouse pups were dissociated with papain (Sigma) and grown in neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2% B27 supplement (Invitrogen), 0.5 mM glutamine, and 12.5 μM glutamate. The amygdala was dissected as described in a previous study (Lesscher et al., 2008). The cortices from embryonic day 17.5 mice were trypsinized, dissociated, and cultured in neurobasal medium with 2% B27 supplement and 0.5 mM glutamine. For immunofluorescence staining, 350,000 neurons per well were plated in 12-well plates with poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips. For quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis, neurons were plated at a density of 1,000,000 cells/well in poly-L-lysine-coated 6-well plates. Under these conditions, the cultures were treated with drugs and subjected to subsequent experiments after 21 days in vitro (DIV).

QUANTITATIVE PCR

The RNA from cultured neurons and different brain regions of adult mice was purified as described (Huang et al., 2014). The extracted RNA was then subjected to complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The LightCycler 480 Probes Master kit (Roche) was used for the quantitative-PCR assay. The primer sets for Tbr1 were 5′-CAAGGGAGCATCAAACAACA-3′ and 5′-GTCCTCTGTGCCATCCTCAT-3′. The primer sets for Grin2b were 5′-GGGTTACAACCGGTGCCTA-3′ and 5′-CTTTGCCGATGGTGAAAGAT-3′. The primer sets for c-Fos were 5′-GGGACAGCCTTTCCTACTACC-3′ and 5′- AGATCTGCGCAAAAGTCCTG-3′.

IMMUNOFLUORESCENCE STAINING

Primary cultured neurons were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and 4% sucrose in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature (RT) for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.1% TritonX-100 in PBS for 10 min, and blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 3% horse serum (HS) in PBS for 2 h. After blocking, the neurons were incubated with anti-TBR1 antibody (4 μg/ml) and anti-MAP2 antibody (1:500) in PBS containing 2% BSA and 3% HS overnight at 4∘C. After washing, the cells were incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor® 488 and Alexa Fluor® 555 at RT for 2 h, followed by mounting in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). Counter stain with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) was performed to label nuclei of neurons. The images were captured with a confocal microscope (LSM 700; Carl Zeiss) and then analyzed with the MetaMorph analysis software (MetaMorph) to quantify the TBR1 fluorescence intensity. The single-plane image was opened and the multi-wavelength cell scoring module was used to score the TBR1 fluorescence intensity of neurons. The regions of nuclei were defined by the signals of DAPI. The average intensity of nuclear TBR1 was determined to indicate the mean fluorescence intensity of TBR1. For each experiment, about thirty neurons were collected in each treatment. At least three independent experiments were carried out. The statistical analysis was performed using the pooled data from repeated experiments.

CONDITIONED TASTE AVERSION

The behavioral paradigm was as previously described (Huang et al., 2014). Briefly, water-deprived mice at 10–16 weeks of age were trained to receive their daily water for 15 min in the experimental cages during the pre-training period. On training day (D0), mice were offered a sucrose solution as a new pleasant taste for 15 min and were subsequently intraperitoneally injected with lithium chloride (LiCl; 0.15 M, 20 μl/g of body weight) to induce aversive responses or with sodium chloride (NaCl) as a control. Two or twenty-four hours after injection, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Different brain areas were then sampled for the subsequent quantitative PCR analysis.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. The statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Dunnett test (Figures 1, 3, 4C–E, and 6) and an unpaired t-test (Figure 2) in GraphPad Prism or a two-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test (Figures 4B and 5) via the SigmaStat software version 3.5 (Copyright© 2006 Systat Software, Inc., Germany). A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

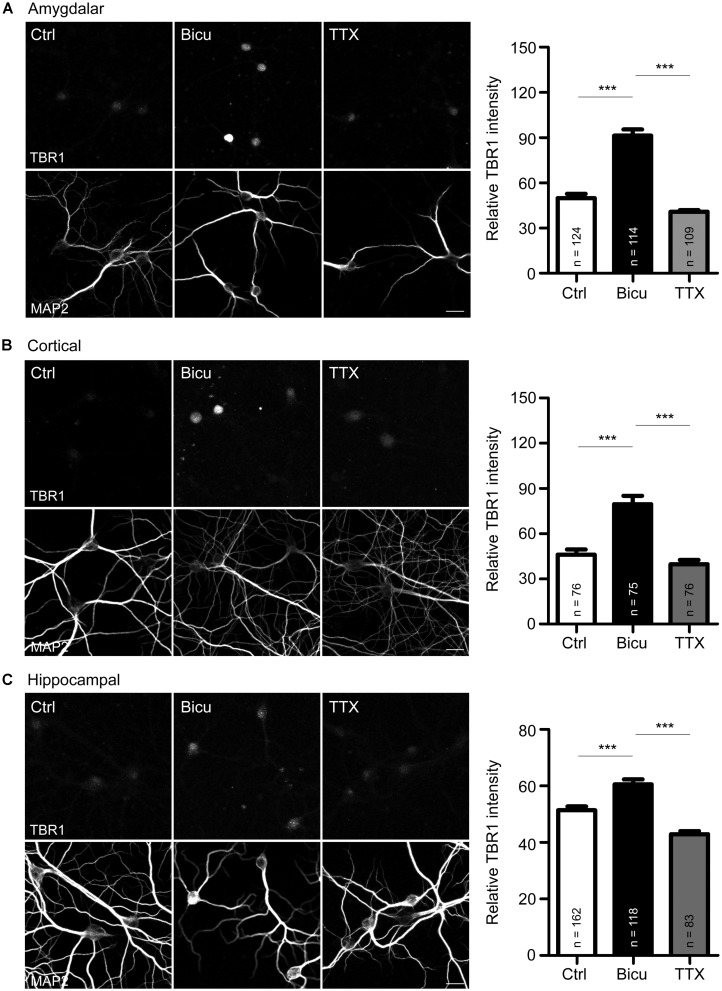

FIGURE 1.

T-brain-1 proteins are induced by neuronal activation in cultured neurons. (A–C) Double immunostaining with TBR1 and MAP2 antibodies. Primary amygdalar (A), cortical (B), and hippocampal (C) neurons were incubated with TTX (1 μM) or bicuculline (Bicu, 40 μM) for 6 h at 21 DIV. Neurons were then fixed for immunostaining. Scale bars: 20 μm. The bar graphs in right panels of (A–C) show the mean fluorescence intensity of TBR1 quantified by MetaMorph software. All data are presented as the mean + SEM. The number of neurons (n) analyzed for each experiment is indicated in the figure. ***P < 0.001.

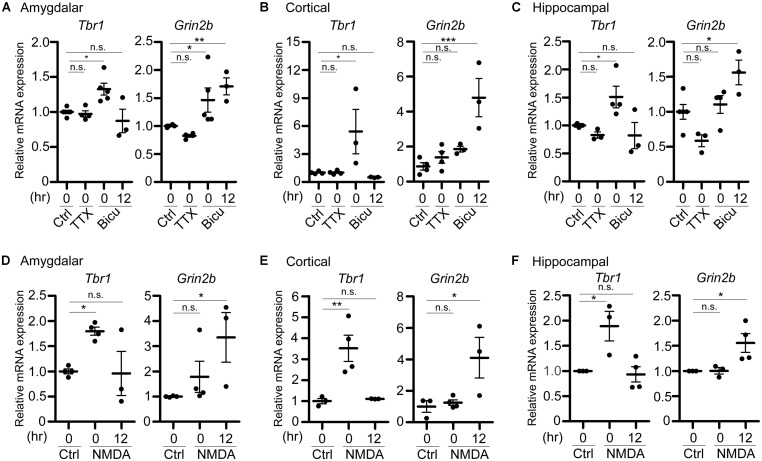

FIGURE 3.

Tbr1 upregulation correlates with Grin2b induction in cultured neurons. Quantitative-PCR analyses were performed to examine the expression of Tbr1 and Grin2b upon (A–C) TTX and bicuculline (Bicu) treatment and (D–F) NMDAR activation. Cultured amygdalar (A,D), cortical (B,E), and hippocampal (C,F) neurons were incubated with TTX (1 μM), bicuculline (40 μM), NMDA (10 μM), or vehicle (Ctrl) for 6 h. Immediately (0 h) or 12 more hours (12 h) after treatment, neurons were harvested for quantitative-PCR using Cyp as an internal control to quantify the relative mRNA levels of Tbr1 and Grin2b at 21 DIV. The experiments were performed independently at least three times. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.001; n.s., not significant.

FIGURE 4.

Behavioral stimulation results in upregulation of Tbr1 and Grin2b in adult brains. (A) A simple flowchart of CTA test. The tissues were sampled 2 and 24 h after injection. (B) The amounts of water drunk during pre-training (D-1) and sucrose drunk on the CTA training day (D0). (C–E) Quantitative-PCR analyses to examine the expression of Tbr1, Grin2b, and c-Fos upon behavioral training. Two hours after NaCl or LiCl injection and 24 h after LiCl injection, the lateral amygdala, insular cortex and ventral hippocampus were collected for quantitative-PCR using Cyp as an internal control to detect the relative mRNA levels of Tbr1 (C), Grin2b (D), and c-Fos (E) in adult mice. Six animals were used for each experiment. All data represent the mean + SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.001; n.s., not significant.

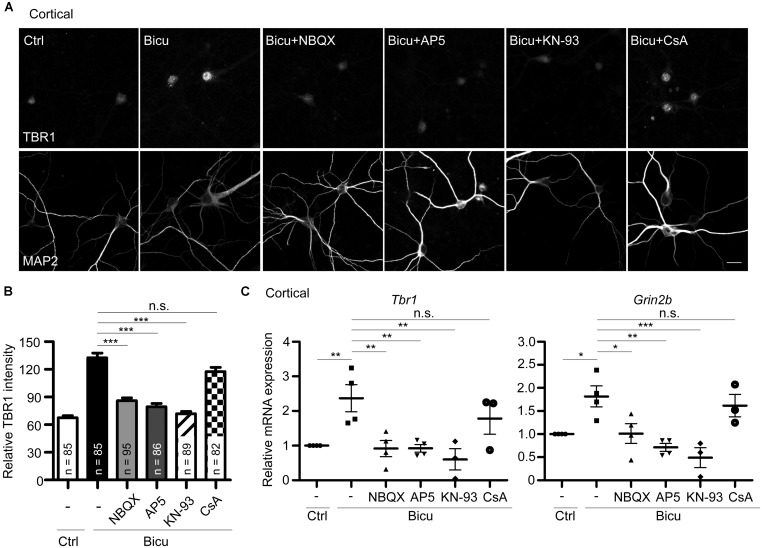

FIGURE 6.

T-brain-1 upregulation requires activation of CaMKII in neuronal cultures. Cultured cortical neurons of WT mice were pretreated with APV (100 μM), NBQX (100 μM), KN-93 (5 μM), or CsA (5 μM) for 30 min prior to bicuculline stimulation (Bicu, 40 μM) for 6 h. Neurons were then fixed for immunostaining (A,B) or harvested for quantitative-PCR (C) at 21 DIV. (A) Double immunostaining with TBR1 and MAP2 antibodies. Scale bars: 20 μm. The quantitative data of TBR1 fluorescence intensities are shown in (B). The number of neurons (n) for each experiment is indicated in the figures. All data represent the mean + SEM. (C) Real-time PCR to quantify the relative mRNA levels of Tbr1 and Grin2b upon bicuculline activation. The Cyp expression level was used as an internal control. Experiments were repeated at least three independent times. All data represent the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.001; n.s., not significant.

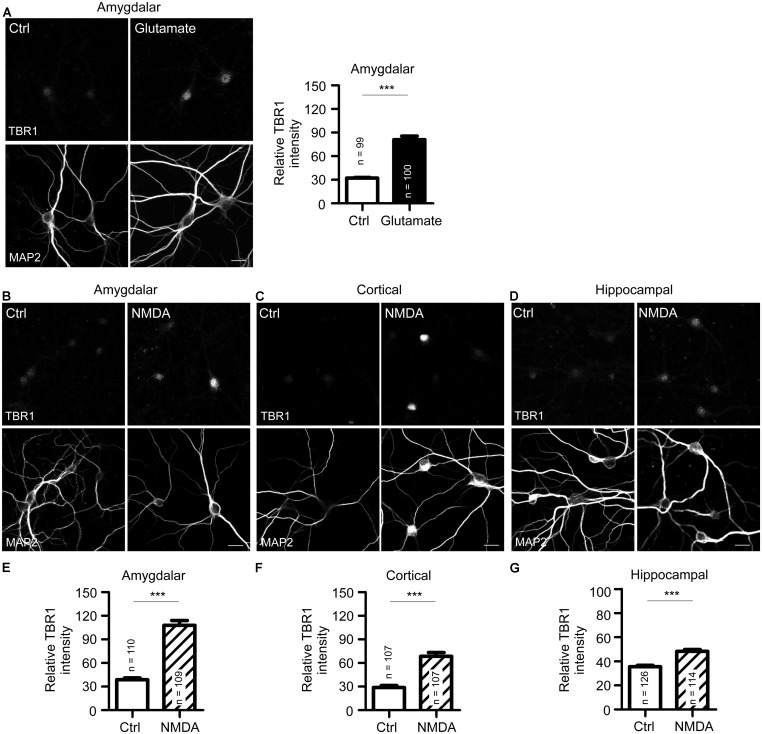

FIGURE 2.

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activation induces TBR1 expression in cultured neurons. (A) Mature amygdalar neurons at 21 DIV were treated with glutamate (50 μM) for 10 min and transferred to normal culture medium for 2 more hours. Neurons were then fixed and immunostained with TBR1 and MAP2 antibodies. Quantitative data show the relative intensity of TBR1 fluorescence. (B–D) The mature amygdalar (B), cortical (C), and hippocampal (D) neurons were incubated with NMDA (10 μM) for 6 h. After staining with TBR1 and MAP2 antibodies, the means of TBR1 fluorescence intensities are shown in (E–G). Scale bars: 20 μm. All data represent the mean + SEM. The number of neurons (n) for each experiment is indicated in the panels. ***P < 0.001.

FIGURE 5.

Grin2b induction upon neuronal activation requires Tbr1 expression in neuronal cultures. Bicuculline (Bicu, 40 μM) was added to the WT and Tbr1 KO amygdalar cultures at 21 DIV for 6 h. Quantitative-PCR analysis was conducted to measure the relative mRNA levels of Tbr1 (A) and Grin2b (B) immediately (0 h) and 12 h after bicuculline stimulation. The Cyp expression level was used as an internal control. Tbr1 KO amygdalar neurons did not respond to bicuculline in terms of Grin2b induction. Experiments were repeated three independent times. Data represent the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; n.s., not significant.

RESULTS

THE TBR1 PROTEIN LEVELS ARE REGULATED BY NEURONAL ACTIVITY IN CULTURED NEURONS

Upon behavioral stimulation, most TBR1-positive projection neurons in the amygdalae of adult brains express c-FOS (Huang et al., 2014), a marker for neuronal activity, which suggests the involvement of TBR1-positive neurons in behavioral responses. To examine whether Tbr1 is regulated by or participates in neuronal activation, we first examined the expression of TBR1 in mature amygdalar neurons at 21 DIV using double immunofluorescence staining with TBR1 and the neuronal marker MAP2. The cultures were incubated with the sodium channel blocker TTX (1 μm) or with the ionotropic GABAA-antagonist bicuculline (40 μm) for 6 h to reduce or activate neuronal activity, respectively. Consistent with the previous studies and the role of TBR1 as a transcription factor (Hsueh et al., 2000), we found that TBR1 was mainly located in cell nuclei in the absence of special treatment, though the levels were low (Figure 1A). Interestingly, we found that incubation with bicuculline but not TTX increased the protein expression levels of TBR1 in mature amygdalar neurons (Figure 1A). Because TBR1 is also expressed in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus of the adult brain (Hong and Hsueh, 2007), mature cortical and hippocampal neurons were also used to investigate the induction of TBR1 after neuronal activation. Similarly, bicuculline treatment increased the TBR1 protein levels in the cortical and hippocampal neurons (Figures 1B,C), though the degree of TBR1 induction in hippocampal neurons was much lower than those in amygdalar or cortical neurons (Figure 1). These data indicate that the protein levels of TBR1 are upregulated by neuronal activation.

NMDAR ACTIVATION STIMULATES TBR1 EXPRESSION

Because bicuculline drives neuronal excitability by blocking the activity of inhibitory neurons and because Tbr1 is expressed in excitatory projection neurons (Hevner et al., 2001; Huang et al., 2014), bicuculline likely reduces the inhibitory effect of inhibitory neurons and indirectly increases the expression of Tbr1 in projection neurons. We then examined whether the direct activation of projection neurons by glutamate stimulation also increases TBR1 expression. Similar to bicuculline treatment, we found that TBR1 expression was induced in mature amygdalar neurons after glutamate stimulation (Figure 2A). Among the various glutamate receptors, NMDA receptors are the major glutamate receptors to induce calcium influx and play important roles in the regulation of long-term potentiation, synaptic plasticity, learning and memory. We then investigated whether the induction of TBR1 expression by glutamate depended on the NMDA receptor. NMDA treatment also effectively induced TBR1 upregulation in amygdalar, cortical, and hippocampal neurons (Figures 2B–G). Together, these results support that TBR1 expression undergoes NMDA receptor-dependent regulation.

Tbr1 UPREGULATION ASSOCIATES WITH Grin2b INDUCTION IN NEURONAL CULTURES

In addition to the protein levels, we performed quantitative RT-PCR analysis to examine the change of the Tbr1 mRNA levels upon neuronal activation. Immediately after treatment with TTX or bicuculline for 6 h, cultured amygdalar neurons were either harvested for RNA extraction or washed and incubated in normal culture medium for 12 more hours. We found that while Tbr1 expression was not affected by TTX treatment, the Tbr1 mRNA levels were highly elevated immediately after bicuculline stimulation (labeled as “0” hour after treatment in the figure). Interestingly, we noticed that Tbr1 expression was significantly decreased to a level comparable to that of the vehicle control at 12 h after bicuculline treatment. Similarly, the expression levels of Tbr1 from both cortical and hippocampal neurons were upregulated immediately after bicuculline treatment and decreased 12 h after stimulation (Figures 3B,C), suggesting a transient induction of Tbr1 expression after neuronal activation.

To further confirm if NMDA receptor signaling is also involved in the induction of Tbr1 mRNA expression, we also stimulated cultured amygdalar, cortical, and hippocampal neurons with NMDA for quantitative RT-PCR analysis. We found that the mRNA levels of Tbr1 showed a noticeable increase immediately after NMDA treatment for 6 h and declined to basal levels 12 h after NMDA washout (Figures 3D–F). Together with the immunostaining analysis, these data support that both the mRNA and protein levels of Tbr1 are upregulated in an activity-dependent manner via the NMDA receptor.

Because TBR1 was shown to directly regulate the expression of Grin2b (Wang et al., 2004b), one of the NMDAR subunits implicated in proper neuronal activity, and because the GRIN2B expression levels were upregulated upon behavioral stimulation (Huang et al., 2014), we then assessed whether the activity-dependent upregulation of Tbr1 expression is relevant to the induction of Grin2b during neuronal activation. Therefore, the RNA expression level of Grin2b was also examined. We found that the Grin2b expression levels tended to be increased immediately after treatment with bicuculline or NMDA for 6 h, although only the bicuculline treatment of amygdalar neurons resulted in significant differences from vehicle-treated neurons (Figure 3). In all amygdalar, cortical and hippocampal neurons, the Grin2b mRNA levels were noticeably upregulated 12 h after bicuculline or NMDA treatment (Figure 3), suggesting a time delay in the upregulation of Grin2b expression after neuronal activation. These data indicate that neuronal activation first induces Tbr1 upregulation and then increases Grin2b expression.

BEHAVIORAL TRAINING INDUCES Tbr1 UPREGULATION IN ADULT MICE

We then employed behavioral stimulation to investigate whether Tbr1 responds to neuronal activity and regulates Grin2b expression in vivo. The conditioned taste aversion (CTA) test, an amygdala-dependent learning and memory test, was chosen for behavioral stimulation. In CTA, mice will learn to correlate a novel food (sucrose) with aversive responses induced by LiCl injection (Figure 4A). An injection of NaCl was used as a control. Consistent with a previous observation (Huang et al., 2014), the amounts of sucrose solution drunk on the training day (D0) were higher than the amounts of water drunk during pre-training (D-1), suggesting that all mice behaved normally to prefer to drink sucrose (Figure 4B). Two or 24 h after training, animals were sacrificed to examine the expression of Tbr1 and Grin2b mRNAs using quantitative RT-PCR. In the lateral amygdala, the expression levels of Tbr1 or Grin2b were highly upregulated 2 h but significantly decreased 24 h after CTA training (Figures 4C,D, the groups of 2 and 24 h after LiCl injection). Because the amygdala has strong reciprocal interactions with the ventral hippocampus and insular cortex to modulate behavioral responses (Piette et al., 2012; Felix-Ortiz and Tye, 2014), we then examined whether CTA training also increases the expression levels of Tbr1 and Grin2b in the ventral hippocampus and insular cortex. The induction of Tbr1 and Grin2b were observed in these two brain regions (Figures 4C,D). These in vivo data support that both Tbr1 and Grin2b were upregulated in the brain in response to behavioral stimulation.

Because c-Fos has been shown to be an IEG that is upregulated after behavioral training (Montag-Sallaz et al., 1999), we also included c-Fos as a positive control in the quantitative PCR assay. Similar to Tbr1 mRNA, we found that the c-Fos expression levels in the lateral amygdala, insular cortex, and ventral hippocampus were upregulated at 2 h but returned to a level comparable to that of the control 24 h after CTA training (Figure 4E). The c-Fos expression pattern confirmed the neuronal activation upon behavioral stimulation in our experiment.

TBR1 IS REQUIRED FOR THE INDUCTION OF Grin2b UPON NEURONAL ACTIVATION

To directly investigate whether an increase in TBR1 expression in cultured neurons is essential to Grin2b upregulation, Tbr1 knockout (KO) amygdalar neurons were cultured, and their response to bicuculline was investigated. Similar to the aforementioned data, the Tbr1 mRNA levels showed a noticeable increase in WT neurons immediately after bicuculline stimulation (Figure 5A). Tbr1 mRNA was not detected in Tbr1 KO neurons, supporting the specificity of our quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 5A). More importantly, we found that the Grin2b mRNA expression was no longer increased 12 h after bicuculline treatment in Tbr1 KO neurons (Figure 5B). These results support that TBR1 is required for the induction of Grin2b expression upon neuronal activation.

CaMKII IS REQUIRED FOR THE Tbr1 INDUCTION

The above results have demonstrated the upregulation of Tbr1 expression upon neuronal activation in vitro and in vivo. We next investigated the possible mechanisms by which neuronal activity induces Tbr1. Upon the excitatory synaptic transmission triggered by bicuculline or glutamate treatment, the depolarization of the plasma membrane via AMPA glutamate receptors can trigger the opening of NMDA receptors (Soderling and Derkach, 2000). Thus, we investigated whether the AMPA receptor was required for bicuculline-induced Tbr1 upregulation. The pre-incubation of cultured cortical neurons with the AMPA receptor antagonist NBQX (100 μM; for 30 min) inhibited the induction of Tbr1 expression by bicuculline at both the protein and mRNA levels (Figures 6A–C). Moreover, blocking NMDA receptor activation by incubating cells with the NMDA receptor antagonist APV (100 μM) for 30 min prior to bicuculline application noticeably inhibited activity-dependent Tbr1 upregulation (Figures 6A–C), which is consistent with the above data indicating that the NMDA receptor is required for Tbr1 induction. These data suggest that the activations of both the AMPA and NMDA receptors contribute to Tbr1 induction following bicuculline treatment.

Because the NMDA receptor promotes activity-dependent gene expression by directly or indirectly activating a number of signaling molecules, such as CaMKII or calcium-dependent phosphatase calcineurin (Greer and Greenberg, 2008), we investigated whether CaMKII or calcineurin is required for Tbr1 upregulation upon bicuculline treatment. To test this possibility, the mature cortical neurons were pretreated with the CaMKII antagonist KN-93 (5 μM) or calcineurin antagonist cyclosporin A (CsA; 5 μM) and then stimulated with bicuculline. Immunostaining with the TBR1 antibody indicated that pre-incubation with KN-93 could block the upregulation of TBR1 induced by bicuculline (Figures 6A,B), whereas CsA did not significantly affect TBR1 induction. In addition to blocking the protein levels, KN-93 but not CsA inhibited bicuculline-induced Tbr1 mRNA expression (Figure 6C), suggesting that neuronal activation upregulates Tbr1 expression in a CaMKII-dependent manner. Similar to the inhibition of Tbr1 upregulation, we found that the Grin2b induction in response to bicuculline activation was also blocked by inhibiting the CaMKII activity with KN-93 (Figure 6C).

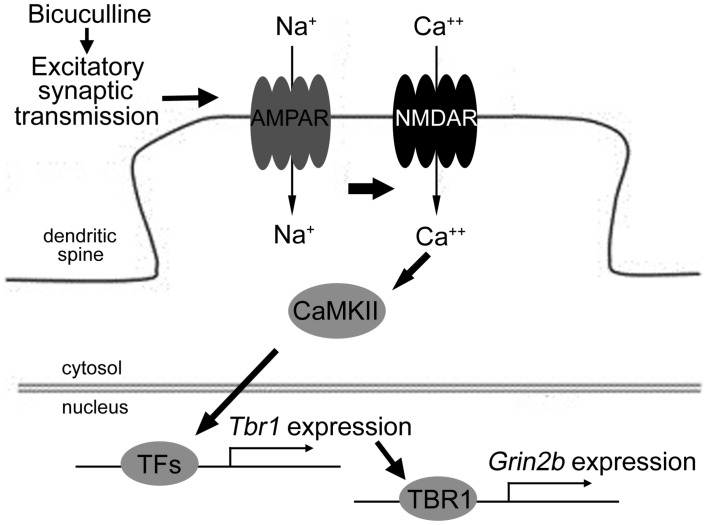

Together, these results suggest that excitatory synaptic transmission driven by bicuculline treatment can activate both the AMPA and NMDA receptors. The signaling pathway of CaMKII underlying the activation of NMDAR is involved in neuronal activation-dependent Tbr1 upregulation. The elevation of Tbr1 expression further increases Grin2b expression (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

The model of the signaling pathways elucidating Tbr1 upregulation by neuronal activation. Excitatory synaptic transmission driven by bicuculline treatment triggers the activation of the AMPA glutamate receptor. Na+ influx through the AMPA receptor depolarizes the plasma membrane and then activates the NMDA receptor. The activation of CaMKII signaling via NMDAR can induce Tbr1 expression perhaps via other activity-dependent transcription factors (TFs). The elevation of the TBR1 protein levels can further upregulate the Grin2b expression following neuronal activation.

DISCUSSION

Tbr1 EXPRESSION AND ITS UPSTREAM REGULATION

Tbr1 has been shown to play a critical role in brain development during the embryonic stage (Bulfone et al., 1995, 1998; Hsueh et al., 2000; Hevner et al., 2001; Medina et al., 2004; Remedios et al., 2007; Bedogni et al., 2010; Han et al., 2011). In the current report, we provide evidence that Tbr1 also impacts mature neurons: neuronal activation upregulates the expression of Tbr1 to further induce Grin2b expression. Tbr1 induction requires NMDA receptor-mediated excitatory synaptic transmission. Thus, TBR1 is involved in a positive feedback loop to upregulate NMDAR pathway.

Here, we show that the activation of CaMKII driven by calcium influx via NMDAR is required for Tbr1 expression in response to neuronal activation. However, how CaMKII signaling contributes to Tbr1 upregulation is unclear. The stimulation of NMDAR by synaptic activity activates the cyclic-AMP response element binding protein (CREB; Hardingham et al., 2002), an activity-dependent transcription factor critical for learning and memory. Furthermore, ample evidence suggests that CaMKII can regulate the rapid transcription of IEGs, including c-Fos and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Bdnf), by phosphorylating and activating CREB (Greer and Greenberg, 2008). Phosphorylation increases the interaction of CREB with the coactivator CREB-binding protein (CBP) and induces the binding to the full palindromic CRE sequence (TGACGTCA) or the half CRE site (TGACG/CGTCA) to promote expression of target genes (Zhang et al., 2005). Using the bioinformatics database (http://natural.salk.edu/CREB/), we found the several predicted CRE sites in both human and mouse Tbr1 genes from the range of 5 kb upstream to 1 kb downstream of the transcription start site. For mouse Tbr1 gene, the CREB binding sites are located around the nucleotide residues -4460, -4368, -3682, -3418, -3019, +432, and +536 relative to the transcription initiation site. For human TBR1 gene, the half CRE sites are positioned around nucleotide residues -4797, -862, and +478 relative to transcription start site. These bioinformative analyses also favor that CREB is likely a candidate to induce Tbr1 expression, although further experiments such as electrophoretic mobility shift assay and luciferase reporter assay are needed to confirm this speculation.

In addition to CaMKII, calcium influx also activates calcineurin, a calcium-activated serine phosphatase. Calcineurin plays a critical role in the synaptic plasticity through regulating the transcription factor nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT; Schwartz et al., 2009) and the activity of NMDA receptor channels (Lieberman and Mody, 1994; Victor et al., 1995). It also triggers nuclear export of histone deacetylases and thus modulates c-Fos expression (Parkes and Westbrook, 2011). To test the role of calcineurin in Tbr1 expression, we have applied cyclosporine A to the cultures and found that inhibition of calcineurin with cyclosporin A (CsA) could not block the Tbr1 upregulation triggered by bicuculline, suggesting that calcineurin is not involved in neuronal activity-induced Tbr1 expression. However, in addition to regulating calcineurin, CsA has the other activities. It binds to the cyclophilins (CyPs), small intracellular regulatory proteins, to exert its immunosuppressive action. CsA is also an inhibitor for mitochondrial permeability transition by binding mitochondrial matrix-specific CyP-D and blocking its translocation to the inner membrane of mitochondria (Friberg et al., 1998). CsA treatment is also able to increase the intracellular calcium level (Kaminska et al., 2001). Failure of CsA treatment to block the Tbr1 expression indicates that none of these pathways is involved in regulation of Tbr1 expression.

Moreover, the expression of activity-dependent genes can be triggered by the activation of a number of signaling molecules, such as calcium-related signaling cascades, the Ras/MAPK pathway and Rac GTPases (Greer and Greenberg, 2008). Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility of the involvement of other pathways in response to neuronal activation to induce Tbr1 expression. Conversely, the activity-dependent epigenetic modification of the chromatin structure has been implicated in the regulation of the expression of IEGs in response to neuronal activation (Parkes and Westbrook, 2011). Tbr1 expression is regulated by AF9/MLLT3 via the methylation of histone H3 lysine 79 at the Tbr1 transcriptional start site (Buttner et al., 2010), indicating that epigenetic modification may be associated with Tbr1 expression. Many studies have demonstrated that epigenetic DNA methylation at CpG dinucleotides plays important roles in the activity-dependent neural plasticity and memory formation of mature brains (Day and Sweatt, 2010; Stevenson et al., 2011). Therefore, the ability of neuronal activation-driven epigenetic regulations, such as DNA methylation, histone acetylation, or histone phosphorylation, to control the Tbr1 expression in adult brain also constitutes an interesting avenue for future research.

Post-translational modification, such as protein phosphorylation, mediated by neuronal activity has been shown to regulate the transcriptional activity of transcription factors and thus play an important role in neuronal plasticity (Soderling and Derkach, 2000; Greer and Greenberg, 2008). Therefore, in addition to promoting the expression levels of Tbr1, neuronal activation may increase the transcriptional activity of TBR1 to upregulate Grin2b expression. In fact, our previous findings showed that the PKA phosphorylation of CASK, a co-activator of TBR1 (Hsueh et al., 2000), enhances the interaction between CASK and TBR1 and then promotes Grin2b expression (Huang et al., 2010). The activation of the cAMP-PKA pathway plays a critical role in learning-related synaptic plasticity and long-term memory (Kandel, 2012). Thus, the PKA phosphorylation of CASK likely indirectly increased the transcriptional activity of TBR1, which upregulated Grin2b expression and promoted memory formation in adult mice. In the future, exploring the cAMP-PKA pathway to elucidate the role of Tbr1 in mature neurons will be important.

Tbr1 AND IMMEDIATE EARLY GENES

Our study indicated that Tbr1 and c-Fos show similar transient expression patterns upon neuronal activation (Parkes and Westbrook, 2011). As discussed above, similar to c-Fos promoter, there are several CRE sites predicted to locate in Tbr1 promoter. We therefore suggest that Tbr1 may act as an IEG to modulate neural activity-dependent gene transcription. In addition to Grin2b, the ability of TBR1 to control the expression of other neuronal activity-dependent genes is an interesting future avenue of research.

Immediate early genes are a group of genes that are expressed at low levels in quiescent cells, but are induced transiently and rapidly at the transcriptional levels in response to a variety of cellular stimulation (Sheng and Greenberg, 1990). Many IEGs, including the c-Fos family, Jun family, Zif268 (also termed Egr-1), Nur77 and c-Myc, function as transcriptional factors. Some of genes encoding secreted proteins such as Bdnf and cytoskeletal proteins such as Arc comprise other important classes of IEGs (Rial Verde et al., 2006; Parkes and Westbrook, 2011). Numerous studies have demonstrated that the induction of IEGs is differentially regulated during various neural stimulation including seizure activity, stress, focal brain injury, and long-term potential, and memory formation (Hughes and Dragunow, 1995). The previous study also showed that GABAergic inhibition in primary motor cortex induces focal synchronous activation and elicits selective induction of c-Fos and another member of the Jun family, JunB (Berretta et al., 1997). In the report, our data also suggest the involvement of Tbr1 in regulation of GABAergic interneurons in the IEG expression. Besides, the response of IEGs also couples to morphological plasticity. The small GTPases CDC42 and RAC1 are known to be downstream of NMDAR activation in triggering actin branching/polymerization and dendritic spine enlargement (Carlisle and Kennedy, 2005; Tolias et al., 2011; Saneyoshi and Hayashi, 2012). The actin remodeling induced by activated CDC42 and/or RAC1 is able to facilitate the association of Arc mRNA with remodeled actin network at the activated synapse (Huang et al., 2007). These small GTPases also influence gene expression in the nucleus. Expression of the dominant negative mutants of Cdc42, Rac, or RhoA impairs the activation of transcription factor serum response factor (SRF; Hao et al., 2003), which is required for neuronal activity-induced expression of IEGs such as c-Fos, Arc, and Egr1 (Ramanan et al., 2005). It suggests that the Rho GTPases reorganize actin cytoskeleton and thus control the SRF activity to activate IEG expression (Greer and Greenberg, 2008). Another example is the expression of pip92, an IEG critical for neuronal differentiation. RAC1 or CDC42 regulates the expression of pip92 through the activation of p21-activated kinase (PAK1; Park et al., 2007). Thus, the Rho GTPase family also contributes to the regulation of IEGs.

Tbr1 UPREGULATION AND NMDAR ACTIVITY IN AUTISM

In our analyses, Tbr1 expression was induced after the activation of the NMDA receptor, followed by an increase in the Grin2b mRNA levels. Our previous studies also indicated that TBR1 directly binds the Grin2b promoter and controls the expression of luciferase reporter under the control of Grin2b promoter (Wang et al., 2004a,b; Huang et al., 2010). Taken together, Tbr1 likely contributes to neuronal activation-dependent Grin2b expression via a positive feedback loop in mature neurons. Interestingly, our recent data demonstrate that Grin2b induction upon behavioral stimulation is impaired in Tbr1+/- mice, which thus show autism-like behaviors (Huang et al., 2014). Because the reduction of Grin2b likely leads to the deregulation or hypo-activation of NMDAR activity, it then results in an aberrant excitation/inhibition balance. Because the excitation/inhibition imbalance in the brain is highly associated with ASD (Rubenstein and Merzenich, 2003; Won et al., 2012), the impairment of neuronal activation in Tbr1+/- mice likely cannot trigger Tbr1 upregulation and thus cause the lack of Grin2b induction. Therefore, these findings support the hypothesis that neuronal activation-dependent Tbr1 upregulation plays critical roles in the regulation of its target genes relevant to synaptic modification, learning, memory, and psychiatric disorders. Tbr1 has been indicated as high-confidence risk gene for ASDs (Neale et al., 2012; O’Roak et al., 2012a; Huang et al., 2014). In addition to truncated mutants, two missense mutations, N374H and K228E, had been identified in patients with ASD (Neale et al., 2012; O’Roak et al., 2012b). Our previous studies indicated that the N374H mutation impairs the ability of Tbr1 to control the differentiation of amygdalar neurons (Huang et al., 2014). However, whether these autism-linked mutants of Tbr1 disrupt the ability of Tbr1 to sense neuronal activation signals and whether the N374H mutation influences the DNA binding ability or protein stability to further affect TBR1 function remains unclear. Further investigation is needed to elucidate these possibilities.

Note that we reported in an earlier study that NMDA stimulation results in a decrease of Grin2b in neurons (Wang et al., 2004a). Our data presented here indicate that Grin2b expression is upregulated after the activation of the NMDA receptor. This difference is likely due to the degree of activation of the NMDA receptor. In our previous study, 100 μM NMDA was used to stimulate neurons, while 10 μM NMDA was applied in the current study. Because low-dose NMDA leads to the phosphorylation and high-dose NMDA induces de-phosphorylation of CAMKIIα at Thr286 (Bozdagi et al., 2010), the opposite effect on CaMKII phosphorylation may then lead to different consequence in terms of Grin2b expression.

Another interesting data observed in this report is that only treatment with bicuculline, but not NMDA, significantly increased the expression of Grin2b right after 6 h stimulation. Bicuculline administration blocks the inhibitory effect of GABAA receptors, one of major receptors existed in interneurons, and indirectly promotes excitatory synaptic transmission mediated mainly by glutamatergic neurotransmission (Ferraro et al., 1999; Ch’ng et al., 2012). All of ionotropic glutamate receptors (NMDAR, AMPAR, and kainate receptors), metabotropic glutamate receptors and voltage-gated calcium channels can be indirectly activated by bicuculline and lead to calcium influx (Niciu et al., 2012; Banerjee et al., 2013). However, NMDA is a specific agonist for NMDA receptor and has no action on other glutamate receptors. Our condition (10 μM NMDA for 6 h) may not be strong enough to induce Grin2b expression.

In conclusion, our study showed that neuronal activation increases the mRNA and protein levels of Tbr1 via NMDAR-dependent activation. The upregulated TBR1 expression then promotes the expression of Grin2b in mature neurons and adult mice. This study elucidates the physiological significance of Tbr1 in adult brains and suggests the potential involvement of the activity-dependent upregulation of Tbr1 in cognition.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Hsiu-Chun Chuang designed and performed all of the experiments, analyzed the results, and drafted the manuscript. Tzyy-Nan Huang contributed to promoter analysis and discussion. Yi-Ping Hsueh designed the experiments and drafted the manuscript. All of the authors read and approved the final version of manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Profs. John Rubenstein and Robert Hevner for the Tbr1+/- mice, the Genomic Core of the Institute of Molecular Biology, Academia Sinica, for the technical assistance and members of the Hsueh lab for relabeling samples for the blind test. This work was supported by grants from the Academia Sinica (AS-103- TP-B05 to Yi-Ping Hsueh) and the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 102-2321-B-001-029, 102-2321-B-001-054, 103-2321-B-001-002, and 103-2321-B-001-018 to Yi-Ping Hsueh).

REFERENCES

- Banerjee A., Romero-Lorenzo E., Sur M. (2013). MeCP2: making sense of missense in Rett syndrome. Cell Res. 23 1244–1246 10.1038/cr.2013.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedogni F., Hodge R. D., Elsen G. E., Nelson B. R., Daza R. A., Beyer R. P., et al. (2010). Tbr1 regulates regional and laminar identity of postmitotic neurons in developing neocortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 13129–13134 10.1073/pnas.1002285107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benekareddy M., Nair A. R., Dias B. G., Suri D., Autry A. E., Monteggia L. M., et al. (2013). Induction of the plasticity-associated immediate early gene Arc by stress and hallucinogens: role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 16 405–415 10.1017/s1461145712000168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berretta S., Parthasarathy H. B., Graybiel A. M. (1997). Local release of GABAergic inhibition in the motor cortex induces immediate-early gene expression in indirect pathway neurons of the striatum. J. Neurosci. 17 4752–4763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozdagi O., Sakurai T., Papapetrou D., Wang X., Dickstein D. L., Takahashi N., et al. (2010). Haploinsufficiency of the autism-associated Shank3 gene leads to deficits in synaptic function, social interaction, and social communication. Mol. Autism 1:15 10.1186/2040-2392-1-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulfone A., Smiga S. M., Shimamura K., Peterson A., Puelles L., Rubenstein J. L. (1995). T-brain-1: a homolog of Brachyury whose expression defines molecularly distinct domains within the cerebral cortex. Neuron 15 63–78 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90065-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulfone A., Wang F., Hevner R., Anderson S., Cutforth T., Chen S., et al. (1998). An olfactory sensory map develops in the absence of normal projection neurons or GABAergic interneurons. Neuron 21 1273–1282 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80647-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner N., Johnsen S. A., Kugler S., Vogel T. (2010). Af9/Mllt3 interferes with Tbr1 expression through epigenetic modification of histone H3K79 during development of the cerebral cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 7042–7047 10.1073/pnas.0912041107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle H. J., Kennedy M. B. (2005). Spine architecture and synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 28 182–187 10.1016/j.tins.2005.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch’ng T. H., Uzgil B., Lin P., Avliyakulov N. K., O’Dell T. J., Martin K. C. (2012). Activity-dependent transport of the transcriptional coactivator CRTC1 from synapse to nucleus. Cell 150 207–221 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day J. J., Sweatt J. D. (2010). DNA methylation and memory formation. Nat. Neurosci. 13 1319–1323 10.1038/nn.2666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet E. R., Joels M., Holsboer F. (2005). Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6 463–475 10.1038/nrn1683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix-Ortiz A. C., Tye K. M. (2014). Amygdala inputs to the ventral hippocampus bidirectionally modulate social behavior. J. Neurosci. 34 586–595 10.1523/jneurosci.4257-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro L., Antonelli T., Tanganelli S., O’Connor W. T., Perez De La Mora M., Mendez-Franco J., et al. (1999). The vigilance promoting drug modafinil increases extracellular glutamate levels in the medial preoptic area and the posterior hypothalamus of the conscious rat: prevention by local GABAA receptor blockade. Neuropsychopharmacology 20 346–356 10.1016/s0893-133x(98)00085-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friberg H., Ferrand-Drake M., Bengtsson F., Halestrap A. P., Wieloch T. (1998). Cyclosporin A, but not FK 506, protects mitochondria and neurons against hypoglycemic damage and implicates the mitochondrial permeability transition in cell death. J. Neurosci. 18 5151–5159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli F., Caffino L., Vogt M. A., Frasca A., Racagni G., Sprengel R., et al. (2011). AMPA GluR-A receptor subunit mediates hippocampal responsiveness in mice exposed to stress. Hippocampus 21 1028–1035 10.1002/hipo.20817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer P. L., Greenberg M. E. (2008). From synapse to nucleus: calcium-dependent gene transcription in the control of synapse development and function. Neuron 59 846–860 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W., Kwan K. Y., Shim S., Lam M. M., Shin Y., Xu X., et al. (2011). TBR1 directly represses Fezf2 to control the laminar origin and development of the corticospinal tract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 3041–3046 10.1073/pnas.1016723108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao S., Kurosaki T., August A. (2003). Differential regulation of NFAT and SRF by the B cell receptor via a PLCgamma-Ca(2+)-dependent pathway. EMBO J. 22 4166–4177 10.1093/emboj/cdg401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham G. E., Fukunaga Y., Bading H. (2002). Extrasynaptic NMDARs oppose synaptic NMDARs by triggering CREB shut-off and cell death pathways. Nat. Neurosci. 5 405–414 10.1038/nn835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevner R. F., Shi L., Justice N., Hsueh Y., Sheng M., Smiga S., et al. (2001). Tbr1 regulates differentiation of the preplate and layer 6. Neuron 29 353–366 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00211-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong C. J., Hsueh Y. P. (2007). Cytoplasmic distribution of T-box transcription factor Tbr-1 in adult rodent brain. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 33 124–130 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2007.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh Y. P. (2009). Calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine protein kinase and mental retardation. Ann. Neurol. 66 438–443 10.1002/ana.21755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh Y. P., Wang T. F., Yang F. C., Sheng M. (2000). Nuclear translocation and transcription regulation by the membrane-associated guanylate kinase CASK/LIN-2. Nature 404 298–302 10.1038/35005118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F., Chotiner J. K., Steward O. (2007). Actin polymerization and ERK phosphorylation are required for Arc/Arg3.1 mRNA targeting to activated synaptic sites on dendrites. J. Neurosci. 27 9054–9067 10.1523/jneurosci.2410-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T. N., Chang H. P., Hsueh Y. P. (2010). CASK phosphorylation by PKA regulates the protein-protein interactions of CASK and expression of the NMDAR2b gene. J. Neurochem. 112 1562–1573 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T. N., Chuang H. C., Chou W. H., Chen C. Y., Wang H. F., Chou S. J., et al. (2014). Tbr1 haploinsufficiency impairs amygdalar axonal projections and results in cognitive abnormality. Nat. Neurosci. 17 240–247 10.1038/nn.3626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes P., Dragunow M. (1995). Induction of immediate-early genes and the control of neurotransmitter-regulated gene expression within the nervous system. Pharmacol. Rev. 47 133–178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminska B., Figiel I., Pyrzynska B., Czajkowski R., Mosieniak G. (2001). Treatment of hippocampal neurons with cyclosporin A results in calcium overload and apoptosis which are independent on NMDA receptor activation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 133 997–1004 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel E. R. (2012). The molecular biology of memory: cAMP, PKA, CRE, CREB-1, CREB-2, and CPEB. Mol. Brain 5:14 10.1186/1756-6606-5-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King I. F., Yandava C. N., Mabb A. M., Hsiao J. S., Huang H. S., Pearson B. L., et al. (2013). Topoisomerases facilitate transcription of long genes linked to autism. Nature 501 58–62 10.1038/nature12504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen L. V., Patel S. A., Haroutunian V., Meador-Woodruff J. H. (2010). Expression of the NR2B-NMDA receptor subunit and its Tbr-1/CINAP regulatory proteins in postmortem brain suggest altered receptor processing in schizophrenia. Synapse 64 495–502 10.1002/syn.20754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesscher H. M., Mcmahon T., Lasek A. W., Chou W. H., Connolly J., Kharazia V., et al. (2008). Amygdala protein kinase C epsilon regulates corticotropin-releasing factor and anxiety-like behavior. Genes Brain Behav. 7 323–333 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00356.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman D. N., Mody I. (1994). Regulation of NMDA channel function by endogenous Ca(2+)-dependent phosphatase. Nature 369 235–239 10.1038/369235a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina L., Legaz I., Gonzalez G., De Castro F., Rubenstein J. L., Puelles L. (2004). Expression of Dbx1, Neurogenin 2, Semaphorin 5A, Cadherin 8, and Emx1 distinguish ventral and lateral pallial histogenetic divisions in the developing mouse claustroamygdaloid complex. J. Comp. Neurol. 474 504–523 10.1002/cne.20141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montag-Sallaz M., Welzl H., Kuhl D., Montag D., Schachner M. (1999). Novelty-induced increased expression of immediate-early genes c-fos and arg 3.1 in the mouse brain. J. Neurobiol. 38 234–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moog U., Kutsche K., Kortum F., Chilian B., Bierhals T., Apeshiotis N., et al. (2011). Phenotypic spectrum associated with CASK loss-of-function mutations. J. Med. Genet. 48 741–751 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najm J., Horn D., Wimplinger I., Golden J. A., Chizhikov V. V., Sudi J., et al. (2008). Mutations of CASK cause an X-linked brain malformation phenotype with microcephaly and hypoplasia of the brainstem and cerebellum. Nat. Genet. 40 1065–1067 10.1038/ng.194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale B. M., Kou Y., Liu L., Ma’ayan A., Samocha K. E., Sabo A., et al. (2012). Patterns and rates of exonic de novo mutations in autism spectrum disorders. Nature 485 242–245 10.1038/nature11011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niciu M. J., Kelmendi B., Sanacora G. (2012). Overview of glutamatergic neurotransmission in the nervous system. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 100 656–664 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Roak B. J., Vives L., Fu W., Egertson J. D., Stanaway I. B., Phelps I. G., et al. (2012a). Multiplex targeted sequencing identifies recurrently mutated genes in autism spectrum disorders. Science 338 1619–1622 10.1126/science.1227764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Roak B. J., Vives L., Girirajan S., Karakoc E., Krumm N., Coe B. P., et al. (2012b). Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature 485 246–250 10.1038/nature10989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes S. L., Westbrook R. F. (2011). Role of the basolateral amygdala and NMDA receptors in higher-order conditioned fear. Rev. Neurosci. 22 317–333 10.1515/RNS.2011.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. B., Kim E. J., Yang E. J., Seo S. R., Chung K. C. (2007). JNK- and Rac1-dependent induction of immediate early gene pip92 suppresses neuronal differentiation. J. Neurochem. 100 555–566 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04263.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer B. E., Zang T., Wilkerson J. R., Taniguchi M., Maksimova M. A., Smith L. N., et al. (2010). Fragile X mental retardation protein is required for synapse elimination by the activity-dependent transcription factor MEF2. Neuron 66 191–197 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piette C. E., Baez-Santiago M. A., Reid E. E., Katz D. B., Moran A. (2012). Inactivation of basolateral amygdala specifically eliminates palatability-related information in cortical sensory responses. J. Neurosci. 32 9981–9991 10.1523/jneurosci.0669-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popoli M., Yan Z., Mcewen B. S., Sanacora G. (2012). The stressed synapse: the impact of stress and glucocorticoids on glutamate transmission. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13 22–37 10.1038/nrn3138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanan N., Shen Y., Sarsfield S., Lemberger T., Schutz G., Linden D. J., et al. (2005). SRF mediates activity-induced gene expression and synaptic plasticity but not neuronal viability. Nat. Neurosci. 8 759–767 10.1038/nn1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remedios R., Huilgol D., Saha B., Hari P., Bhatnagar L., Kowalczyk T., et al. (2007). A stream of cells migrating from the caudal telencephalon reveals a link between the amygdala and neocortex. Nat. Neurosci. 10 1141–1150 10.1038/nn1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revest J. M., Di Blasi F., Kitchener P., Rouge-Pont F., Desmedt A., Turiault M., et al. (2005). The MAPK pathway and Egr-1 mediate stress-related behavioral effects of glucocorticoids. Nat. Neurosci. 8 664–672 10.1038/nn1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rial Verde E. M., Lee-Osbourne J., Worley P. F., Malinow R., Cline H. T. (2006). Increased expression of the immediate-early gene arc/arg3.1 reduces AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission. Neuron 52 461–474 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein J. L., Merzenich M. M. (2003). Model of autism: increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes Brain Behav. 2 255–267 10.1034/j.1601-183X.2003.00037.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saneyoshi T., Hayashi Y. (2012). The Ca2+ and Rho GTPase signaling pathways underlying activity-dependent actin remodeling at dendritic spines. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 69 545–554 10.1002/cm.21037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz N., Schohl A., Ruthazer E. S. (2009). Neural activity regulates synaptic properties and dendritic structure in vivo through calcineurin/NFAT signaling. Neuron 62 655–669 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M., Greenberg M. E. (1990). The regulation and function of c-fos and other immediate early genes in the nervous system. Neuron 4 477–485 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90106-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderling T. R., Derkach V. A. (2000). Postsynaptic protein phosphorylation and LTP. Trends Neurosci. 23 75–80 10.1016/S0166-2236(99)01490-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson D. A., Yan J., He Y., Li H., Liu Y., Zhang Q., et al. (2011). Multiple increased osteoclast functions in individuals with neurofibromatosis type 1. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 155 1050–1059 10.1002/ajmg.a.33965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarpey P. S., Smith R., Pleasance E., Whibley A., Edkins S., Hardy C., et al. (2009). A systematic, large-scale resequencing screen of X-chromosome coding exons in mental retardation. Nat. Genet. 41 535–543 10.1038/ng.367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolias K. F., Duman J. G., Um K. (2011). Control of synapse development and plasticity by Rho GTPase regulatory proteins. Prog. Neurobiol. 94 133–148 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor R. G., Thomas G. D., Marban E., O’Rourke B. (1995). Presynaptic modulation of cortical synaptic activity by calcineurin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 6269–6273 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. S., Hong C. J., Yen T. Y., Huang H. Y., Ou Y., Huang T. N., et al. (2004a). Transcriptional modification by a CASK-interacting nucleosome assembly protein. Neuron 42 113–128 10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00139-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T. F., Ding C. N., Wang G. S., Luo S. C., Lin Y. L., Ruan Y., et al. (2004b). Identification of Tbr-1/CASK complex target genes in neurons. J. Neurochem. 91 1483–1492 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02845.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weickert C. S., Fung S. J., Catts V. S., Schofield P. R., Allen K. M., Moore L. T., et al. (2013). Molecular evidence of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor hypofunction in schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry 18 1185–1192 10.1038/mp.2012.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won H., Lee H. R., Gee H. Y., Mah W., Kim J. I., Lee J., et al. (2012). Autistic-like social behaviour in Shank2-mutant mice improved by restoring NMDA receptor function. Nature 486 261–265 10.1038/nature11208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen E. Y., Liu W., Karatsoreos I. N., Ren Y., Feng J., Mcewen B. S., et al. (2011). Mechanisms for acute stress-induced enhancement of glutamatergic transmission and working memory. Mol. Psychiatry 16 156–170 10.1038/mp.2010.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Odom D. T., Koo S. H., Conkright M. D., Canettieri G., Best J., et al. (2005). Genome-wide analysis of cAMP-response element binding protein occupancy, phosphorylation, and target gene activation in human tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 4459–4464 10.1073/pnas.0501076102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]