Abstract

Little research has explored same-sex parents’ school engagement, although there is some evidence that same-sex parents’ perceptions of openness versus exclusion in the school setting –as well as other interrelated contexts – may have implications for their relationships with and perceptions of their children’s schools. The current cross-sectional study used multilevel modeling to examine the relationship between same-sex parents’ perceptions of stigma in various contexts and their self-reported school involvement, relationships with teachers, and school satisfaction, using a sample of 68 same-sex adoptive couples (132 parents) of kindergarten-age children. Parents who perceived their communities as more homophobic reported higher levels of school-based involvement. Parents who perceived lower levels of sexual orientation-related stigma at their children’s schools reported higher levels of school satisfaction. Parents who perceived lower levels of exclusion by other parents reported higher levels of school-based involvement and better relationships with teachers. However, perceived exclusion interacted with parents’ level of outness with other parents, such that parents who were very out and reported high levels of exclusion reported the lowest quality relationships with teachers. Our findings have implications for scholars who study same-sex parent families at various stages of the life cycle, as well as for teachers and other professionals who work with diverse families.

Keywords: gay, kindergarten, lesbian, outness, parent-teacher relationships, same-sex school involvement, school satisfaction, stigma

As more and more lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people become parents, their unique experiences and challenges in the school context become increasingly important to study. To date, little work has explored LGBT parents’ experiences with schools (Kosciw & Diaz, 2008; Lindsay et al., 2006; Mercier & Harold, 2003). This work has established that LGBT parent families are vulnerable to stigma, rejection, and exclusion in school settings. School personnel may hold negative attitudes about LGBT people and their children (Herbstrith, Tobin, Hesson-McInnis, & Schneider, 2013) or simply fail to acknowledge the existence of LGBT-parent families in school policies or curriculum, in that these families “lie outside taken for granted heteronormative assumptions” (Lindsay et al., 2006, p. 1060). Both direct and indirect forms of marginalization by their children’s schools have implications for LGBT parents’ connection to and involvement in schools (Byard, Kosciw, & Bartkiewicz, 2013).

The current study focuses on whether and how perceptions of openness and acceptance within various social contexts are related to same-sex parents’ school engagement. According to minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003), if the broader social environment is stigmatizing, minority group members (i.e., sexual minority parents) may experience incongruence between their own needs, experiences, and values and the constraints imposed by social structures. In turn, perceptions of rejection or invisibility within their children’s schools and other interrelated social structures may create minority stress, to which same-sex parents may respond in a variety of ways (e.g., they may advocate for their families, or they may withdraw).

In exploring how same-sex parents’ perceptions of stigma and exclusion in various contexts may relate to their engagement in children’s education, we focus specifically on the outcomes of school involvement, relationships with teachers, and school satisfaction, insomuch as these dimensions of engagement have implications for children’s socioemotional and cognitive development and future academic success (Culp, Hubbs-Tait, Culp, & Starost, 2001; Dearing, Kreider, & Weiss, 2008). When parents develop strong ties with teachers and seek involvement in schools, this may model for children the importance of relationships with teachers, in turn affecting children’s academic experience, as well as providing teachers with a more thorough understanding of children’s developmental needs and strengths via the information that they gain from parents (Dearing et al., 2008). Further, parents’ engagement in school (e.g., via volunteering) may benefit child-teacher relationships indirectly, as such involvement can promote positive family-teacher interactions (Hornby, 2011). Given that parents’ early relationships with their children’s schools can set in motion long-term patterns of school engagement (Beveridge, 2005), this study focuses on understanding predictors of school engagement in a sample of same-sex adoptive parents of young (i.e., kindergarten-age) children. In this study, we seek to examine sexual minority-specific predictors of school engagement (e.g., perceptions of stigma), rather than established predictors of heterosexual parents’ school engagement, although we include some of these (e.g., parent education, work hours) as controls.

Perceptions of Openness and Acceptance

Same-sex parents’ perceptions of openness and acceptance in various contexts, including their children’s school, the broader community in which they live, and the parent community, may influence their views of and relationships with schools. Further, same-sex parents’ own openness about their sexual orientation may shape their engagement with schools. Finally, parents’ openness may also interact with their perceptions of acceptance in various contexts to affect their school engagement.

School Climate

The overall school climate – whether it is open and inclusive, or rejecting and stigmatizing – may shape same-sex parents’ school engagement. Findings from a national study of K-12 public school principals suggest that school administrators themselves are often aware of the chilly climate for LGBT parents (GLSEN & Harris Interactive, 2008). Many of the principals surveyed believed that an LGBT parent might be uncomfortable attending a school function, with 1 in 6 reporting that an LGBT parent would feel “less than comfortable” participating in the following activities at their school: joining the parent-teacher organization (15%), helping in the classroom (15%), or chaperoning a field trip (16%). Likewise, the Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) surveyed LGBT parents with children ranging from kindergarten through 12th grade and found that LGBT parents described various types of exclusion, both explicit and implicit, including being excluded by school policies and procedures, being excluded from school activities and events, and being ignored/feeling invisible.

Perceptions of stigma and exclusion may, in turn, impact same-sex parents’ relationships and engagement with their children’s schools. For example, same-sex parents who perceive their children’s schools as less open and accepting may be less satisfied with these schools and may report less positive relationships with teachers. They may also be less willing to become involved in school activities. For example, the GLSEN study found that LGBT parents who felt excluded from the school community were less likely than those who did not feel excluded to be involved in a parent-teacher organization (44% versus 63%; Kosciw & Diaz, 2008).

The GLSEN study is not specific to parents of young children, as it surveyed parents of children from a wide range of ages. This raises the possibility that divergent findings might be obtained among parents of younger children, who tend to be more involved, overall, in their children’s education (Hornby, 2011). Same-sex parents of young children who view their children’s schools as stigmatizing may demonstrate greater school engagement than those who perceive less stigma, in that concerns for their children’s well-being may prompt vigilance and advocacy (Byard et al., 2013). Support for this possibility comes from qualitative work (Mercier & Harold, 2003; Nixon, 2011) that suggests that same-sex parents – particularly those with young children – who worry about the potential for discrimination at school may strive to be more visible, in an effort to make it harder for school personnel to ignore or mistreat them.

The Broader Community

Families, and schools, exist in a larger context (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). Just as same-sex parents who perceive their children’s schools as stigmatizing with respect to their sexual orientation may respond by becoming more involved in the school, same-sex parents who reside in communities that they perceive as homophobic may increase their involvement and advocacy on behalf of their children. Same-sex parents who live in rural or conservative communities have been found to report various challenges and barriers in terms of accessing needed services and community supports, which they sometimes respond to by employing strategies of resourcefulness and self-advocacy (Goldberg, Weber, Moyer, Shapiro, 2014; Kinkler & Goldberg, 2011). Same-sex parents’ perceptions of their broader community climate, then, may shape how they approach their children’s schools. Same-sex parents who view their communities as homophobic may be more vigilant about minimizing their children’s exposure to potential bias and respond proactively by becoming involved in their children’s schools.

The Parent Community

Another important part of the school community is other parents. Perceptions of exclusion from other parents have implications for parents’ school engagement, such that parents who form ties with other parents feel more connected to and are more involved in the school (Levine-Rasky, 2003; Sheldon, 2002). By extension, feeling disconnected from one’s community in general and the other parents at one’s child’s school can inhibit parent engagement (Hindman, Miller, Froyen, & Skibbe, 2012), especially in minority communities (Simoni & Perez, 1995).

Same-sex parents may be particularly vulnerable to perceived exclusion by other parents. The GLSEN survey found that a quarter of LGBT parents reported mistreatment (e.g., being whispered about or ignored) by other parents at their children’s schools (Kosciw & Diaz, 2008). In a study of lesbian mothers, Morris, Balsam, and Rothblum (2002) found that 16% of women reported having experienced harassment, threats, or discrimination at their children’s school or by other parents. Of interest is whether perceived exclusion by other parents is related to parents’ assessment of and engagement with their children’s schools. It is possible that same-sex parents who perceive the parent community as more rejecting – and who thus experience less of a sense of connection to other parents – report less involvement with their children’s schools, poorer relationships with teachers and school personnel, and less satisfaction with schools.

Parents’ Openness About Sexual Orientation

Because of their stigmatized status in society, sexual minorities must manage disclosure of their sexual orientation (Frost & Meyer, 2009). Some theoretical models have conceptualized outness as a minority stressor (Meyer, 2003), whereas others have posited that disclosure (e.g., at work, at school) enables people to achieve congruence in their private and public identities (Fassinger, 1995; Ragins, 2004). Empirical research on the relationship between outness and well-being is mixed, possibly due to differences in the way that outness is experienced by different individuals in different contexts (Legate, Ryan, & Weinstein, 2012). Further, recent work has documented the complex, dual impact of outness on mental health (i.e., it has both positive and negative consequences for well-being; Feldman & Wright, 2013; Kosciw, Palmer, & Kull, 2014). For example, Kosciw and colleagues (2014) found that outness was related to higher victimization, but also higher self-esteem, in LGBT adults.

Research on same-sex parents suggests that they often navigate a “dance of disclosure” with respect to their children’s school communities, and other parents in particular (Lindsay et al., 2006; Nixon, 2011). Parents may experience hesitation or anxiety about coming out to other parents at their children’s schools, and the possible implications of doing so (Byard et al., 2013). Being less “out” with other parents may seem to serve a protective function, by preserving parents’ privacy and minimizing their sense of vulnerability in the school community. But being less “out” with other parents may also interfere with the development of strong relationships with other parents, possibly impeding same-sex parents’ sense of connection to the school community, thus undermining their school engagement (Goldberg, 2010; Ryan & Martin, 2004).

Thus, one possibility is that parents’ outness with other parents is directly and positively related to school engagement (i.e., involvement, relationships with teachers, school satisfaction). Alternatively, it might interact with perceived exclusion by other parents, such that the effects of perceived exclusion by parents on school engagement are exacerbated when same-sex parents are more out with other parents. In other words, same-sex parents who are more out with other parents may be more negatively affected by perceived exclusion, as they may be more likely to attribute perceived rejection to their sexual orientation and, in turn, to be less engaged with the school. Likewise, parents who are very out with other parents, and who perceive high levels of acceptance by other parents, may demonstrate high levels of engagement (Ryan & Martin, 2000).

Parent Gender

Research on parents’ school-based engagement has historically focused on heterosexual parents, and has generally found that mothers are more engaged in their children’s education than fathers (e.g., they volunteer more; Coyl-Shepherd & Newland, 2013). Some authors have suggested that this finding may reflect traditional beliefs about gender roles and gender-based patterns of power in society (Palm & Fagan, 2008). Unknown is whether such gendered patterns manifest in same-sex parent families, who cannot fall back on or assign roles based on (sex) difference, and who are also more likely to share parenting responsibilities than heterosexual parents (Goldberg, Smith, & Perry-Jenkins, 2012). Thus, a question of interest is whether female same-sex parents are more engaged in their children’s education than male same-sex parents, or whether gender differences disappear, or are reversed, in the same-sex parent context.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

This study aims to identify predictors of parents’ self-reports of their school-based involvement, parent-teacher relationships, and school satisfaction, in 68 same-sex parent couples (n = 132 individuals). The limited prior research in this area makes it difficult to develop firm hypotheses regarding many relationships. Our research hypotheses are:

We expect that perceived school stigma will be positively related to involvement (H1A), and negatively related to parent-teacher relationships (H1B) and satisfaction (H1C).

We expect that perceived community homophobia will be positively related to involvement (H2A), and we explore, but do not have hypotheses about, the relationship between community homophobia and the other two school engagement outcomes.

We expect that perceived exclusion by parents will be negatively related to involvement (H3A), parent-teacher relationships (H3B), and school satisfaction (H3C).

We expect that outness with other parents will be positively related to involvement (H4A), parent-teacher relationships (H4B), and school satisfaction (H4C).

We also expect the effect of outness on school engagement to vary according to the level of perceived exclusion, such that parents who are very out and perceive low levels of exclusion will report greater involvement (H5A), better relationships with teacher (H5B), and higher school satisfaction (H5C)

We expect that female same-sex parents may be more involved than male same-sex parents (H6A), but we do not expect them to report better relationships with their children’s teacher (H6B) or to be more satisfied with their children’s schools (H6C).

Method

Description of the Sample

Data were taken from a longitudinal study of the transition to adoptive parenthood. All 68 couples had adopted their first child five years earlier. Respondents’ data were included in the current study if their adopted child was in kindergarten.

Descriptive data for the full sample, and broken down by gender, appear in Table 1. ANOVA revealed that mean annual family income differed by gender, F(1, 67) = 28.88, p < .001, with men reporting higher household incomes (M = $210,137, Mdn = $170,000, SE = $19,008) than women (M = $112,750, Mdn = $108,000, SE = $8,000). The sample as a whole is more affluent compared to national estimates for same-sex adoptive families, which indicate that the average household incomes for same-sex couples with adopted children is $102,474 (Gates, Badgett, Macomber, & Chambers, 2007). The average number of hours per week that parents worked was 36.56 (SE = 1.45). The sample as a whole is well-educated, M = 4.39 (SE = .11), where 4 = bachelor’s degree and 5 = master’s degree. Multilevel linear modeling (MLM, in which parents were nested within couples) revealed no differences in weekly work hours or education level by parent gender.

Table 1.

Descriptives, Controls, Predictors, and Outcomes

| Total M, SD | Female Couples (n = 37; 72 women) M, SD | Male Couples (n = 31; 60 men) M, SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family income | $151,850 ($89,653) | $112,750 ($40,666) | $210,137 ($103,820) |

| Parent work hours | 36.56 (15.09) | 34.71 (14.93) | 38.73 (15.34) |

| Education | 4.39 (.76) | 4.37 (.91) | 4.41 (.54) |

| School stigma | 1.86 (.58) | 1.85 (.55) | 1.87 (.63) |

| Community homophobia | 1.49 (.73) | 1.45 (.70) | 1.53 (.77) |

| Parent exclusion | 1.82 (.67) | 1.82 (.70) | 1.82 (.64) |

| Parent involvement | 2.20 (.53) | 2.28 (.49) | 2.12 (.58) |

| Parent-teacher relationship | 3.38 (.56) | 3.37 (.60) | 3.40 (.52) |

| School satisfaction | 3.20 (.40) | 3.10 (.42) | 3.30 (.31) |

| % | % | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child age (months) | 70.11 (14.02) | 70.01 (15.01) | 70.26 (12.69) |

| Parent race (of color) | 12% | 12% | 11% |

| Child race (of color) | 59% | 71% | 40% |

| Child gender (boy) | 52% | 47% | 58% |

| Adoption type | |||

| Public domestic | 10% | 9% | 14% |

| Private domestic | 75% | 74% | 76% |

| International | 15% | 17% | 10% |

| School type (public) | 55% | 59% | 50% |

| Outness to parents (very out) | 24.5% | 67% | 85% |

Chi-square analyses indicated that the racial distribution of the children in the sample differed by parent gender, χ2(1, 67) = 5.87, p = .002, such that female same-sex couples were more likely to have adopted a child of color (71%) than male same-sex couples (40%). Parents in the sample were mostly Caucasian (88%), compared to 73% of same-sex adoptive parents in national samples (Gates et al., 2007): 5% of the sample was Hispanic/Latino/Latin American, 3% was biracial/multiracial, 2% was African American/Black, and 2% was Asian. Children were mostly of color (59%), compared to 53% of children in same-sex adoptive parent families in national samples (Gates et al., 2007). Namely, 21% were biracial/multiracial, 18% were Hispanic/Latino/Latin American, 10% were African American/Black, and 10% were Asian. The remaining 41% of the children were Caucasian. Fifty-two percent of couples adopted boys, and 48% adopted girls. Chi-square analyses showed that the distribution of parent race and child gender did not significantly differ by parent gender.

The average age of the children in the sample was 5.84 years, or 70.11 months (SD = 14.02 months); ANOVA showed that child age did not differ by parent gender. Fifty-five percent of children attended public school, and 45% of children attended private schools. Chi-square analyses showed that school type did not differ by parent gender.

Regarding geographic location, 42% of the sample resided on the East Coast, 32% lived on the West Coast, 10% lived in the Midwest, and 16% lived in the South. Just over half of the sample (52%) lived in metropolitan areas (i.e., a core urban area of 50,000 or more population); the remainder (48%) lived in non-metropolitan communities (US Census, 2013). Chi-square analyses showed that geographic region did not differ by parent gender.

Attrition analyses were conducted to determine whether the current sample of same-sex adoptive parents, who were assessed when their children were in kindergarten, differed from those who dropped after the one year post-placement follow-up. Eight female same-sex couples and eight male same-sex couples (19% of the sample) dropped out of the study; we compared these 16 couples to our sample of 68 same-sex couples on race, education, income, and geographic region, and found no significant differences between the two groups.

Recruitment and Procedures

Inclusion criteria for the larger study from which this sample was drawn required that (a) couples must be adopting their first child, and (b) both partners must be becoming parents for the first time. Participants were recruited during the pre-adoptive period. Adoption agencies in the US were asked to provide study information to clients who had not yet adopted, typically in the form of a brochure which invited them to participate in a study of the transition to adoptive parenthood. U.S. census data were utilized to identify states with a high percentage of same-sex couples (Gates & Ost, 2004) and effort was made to contact agencies in those states. Over 30 agencies provided information to their clients. Interested couples were asked to contact the principal investigator for details. Because some same-sex couples may not be “out” to agencies about their sexual orientation, several national LGBT organizations assisted with recruitment.

Five years after they had been placed with a child, parents in the original study were contacted and asked to complete an in-depth questionnaire packet that focused on their experiences with regard to their children’s kindergartens. Questionnaires included closed- and open-ended items that addressed parents’ school-related experiences. The data for the current study are drawn from this five-year post-adoptive placement assessment point.

Measures

Outcomes

Dimensions of parent engagement: School involvement, parent-teacher relationships, and school satisfaction

Three dimensions of parent involvement were assessed using the widely-used Parent-Teacher Involvement Questionnaire (PTIQ; Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1995; Kohl, Lengua, & McMahon, 2000), which contains three subscales: (a) the parent’s involvement in the school, (b) the quality of the relationship between the parent and teacher, and (c) the parent’s satisfaction with the school. Parents responded to all items using a 5-point scale, where 0 = never/not at all; 1 = once or twice a year/a little; 2 = almost every month/some; 3 = almost every week/a lot; and 4 = more than once per week/a great deal. The first subscale, Parents’ Involvement and Volunteering at School, contained 9 items, (e.g., “You volunteer at your child’s school”). One item (“You have attended PTA meetings”) was dropped because it was not deemed applicable to kindergarten-age children. The second subscale, Quality of the Relationship between Parent and Teacher, contained 7 items (e.g., “You think your child’s teacher is interested in getting to know you”). The third subscale, Parents’ Endorsement of Child’s School (School Satisfaction), contained 4 items (e.g., “Your child’s school is a good place for your child to be”). The items were summed and averaged for each subscale.

Cronbach’s alphas for the three scales are as follows: .73 for Parent Involvement, .82 for Parent-Teacher Relationship, and .75 for School Satisfaction. Other studies have found similar alphas for these subscales (El Nokali, Bachman, & Votruba-Drzal, 2010; Kohl et al., 2000). The scales are intercorrelated (Involvement and Parent-Teacher Relationship, .42; Parent Involvement and Satisfaction, .37; Parent-Teacher Relationship and Satisfaction, .46; see Table 2 for full intercorrelations table), but represent distinct constructs with differential predictors.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations Among Predictor and Outcome Variables

| Schl Stigma | Com Hom | Par Excl | Out Parent | Fem Par | Educ | Inc | Wk Hrs | Ch Age | Pub Schl | Scl Inv | P-T Rel | Schl Sat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schl Stigma | -- | ||||||||||||

| Community Homophobia | .30 | -- | |||||||||||

| Parent Exclusion | .54 | .18 | -- | ||||||||||

| Out to Parents | −.08 | −.09 | −.23 | -- | |||||||||

| Female Parent | −.02 | −.05 | .001 | −.21 | -- | ||||||||

| Education | .003 | .02 | −.007 | .05 | −.02 | -- | |||||||

| Family Income | .01 | .20 | −.05 | .21 | −.57 | .01 | -- | ||||||

| Work Hours | .14 | .17 | .20 | .09 | −.13 | −.07 | .21 | -- | |||||

| Child Age | .14 | −.09 | .18 | .11 | −.01 | −.01 | −.09 | .09 | -- | ||||

| Public School | .04 | −.14 | .16 | −.03 | −.01 | .16 | −.20 | .04 | .12 | -- | |||

| Schl Involvement | −.32 | .08 | −.35 | .11 | .15 | −.01 | −.04 | −.22 | −.36 | −.01 | -- | ||

| P-T Relationships | −.32 | .01 | −.42 | .03 | −.03 | −.06 | .05 | −.12 | −.10 | −.04 | .42 | -- | |

| Schl Satisfaction | −.35 | −.09 | −.29 | .15 | −.22 | .18 | −.01 | −.12 | −.08 | −.03 | .37 | .46 | -- |

Note: Schl = School; P-T = Parent-Teacher.

Hypothesis testing was not conducted for the bivariate correlations in order to limit the overall number of statistical tests. Consequently, statistical significance is not reported.

Predictors

Parent gender

We examined differences by parent gender by creating a dummy variable where 1 = female and 0 = male.

Perceived sexual orientation-related stigma and exclusion

Perceived school stigma due to sexual orientation was assessed using an 8-item measure (Goldberg & Smith, 2014), which assesses perceived exclusion and mistreatment by teachers, school personnel, and other parents, related to parents’ sexual orientation. Parents responded to the following six items using a 1–5 response scale (1 = not at all true, 5 = very true): 1. I have felt that my parenting skills were questioned because I am a lesbian/gay parent; 2. I have felt mistreated by school staff because I am a lesbian/gay parent; 3. I have felt that staff members/school personnel treat my child differently because his/her parents are lesbian/gay; 4. My child’s teacher uses language that acknowledges lesbian/gay parent families (reverse scored); 5. My child’s teacher sensitively handles assignments that could be hurtful to lesbian/gay-parent families (e.g., Mother’s Day/Father’s Day) (reverse scored); 6. My child’s school uses forms that allow families to identify themselves in the way that they choose (reverse scored). Parents also responded to the following two items using 1–5 scale (1 = not at all excluded, 5 = very excluded): 1. To what degree do you feel excluded from your child’s school on the basis of your sexual orientation?; 2. To what degree do you feel excluded by the parents of your children’s peers on the basis of your sexual orientation? The 8 items were summed and averaged; the variable was mean-centered. Cronbach’s alpha for this measure is .75.

Perceived exclusion by other parents at the school

To measure parents’ perceptions of being accepted and included by other parents at their children’s schools, we adapted a measure by Goodenow (1993), whose measure assessed adolescents’ subjective connection to peers. The original 5 items assessed how connected the person feels to the peers at their school, and we adapted these so that they assess parents’ perceptions of acceptance and inclusion by the other parents at their children’s school. Specifically, each parent responded to the 5 items (e.g., “Other parents at this school are friendly to me” [reverse scored] and “Other parents at this school are not interested in people like me” on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all true; 5 = very true). The 5 items were summed and averaged; the variable was mean-centered. Cronbach’s alpha is .87.

Perceived community homophobia

We asked parents, “How gay-friendly is your immediate community?” and provided these response options: 1 = extremely gay-friendly, 2 = somewhat gay-friendly, 3 = neutral, 4 = not very gay-friendly, and 5 = not at all gay-friendly. Higher scores indicate greater perceived homophobia. The variable was mean-centered.

Outness to other parents

Participants were presented with the prompt, “Please indicate how ‘out’ (open about your sexual orientation) you are to other parents at your child’s school,” and given the following response options: 1 = closeted; 2 = mostly closeted; 3 = somewhat out; 4 = mostly out; and 5 = completely out. Higher scores indicate greater outness. Because there was limited variability in responses (i.e., only 24.5% of participants reported being anything other than “completely out” to other parents), we dichotomized this variable such that 1 = completely out (high outness) and 0 = less than completely out (low outness).

Controls

Education

Parents’ education ranged from 1–6, where 1 = less than high school education, 2 = high school diploma, 3 = associate’s degree or some college, 4 = bachelor’s degree, 5 = master’s degree, and 6 = Ph.D./M.D./JD. We included education (mean-centered), as a control in that both educational and financial resources represent forms of “social capital” that increase the likelihood of parent involvement in education. Greater access to education and income contributes to a sense of investment in and entitlement to education by parents, whereas parents with fewer resources may feel alienated by their children’s schools (Hornby, 2011). Research is fairly consistent in finding that more educated parents tend to be more involved in children’s school lives (Fantuzzo, Tighe, & Childs, 2000; Waanders, Mendez, & Downer, 2007) but do not necessarily have stronger relationships with teachers (Waanders et al., 2007).

Family income

We used parents’ annual combined income (divided by 10,000, and mean-centered) as a control given its association with parents’ school engagement, whereby, for example, parents with more income are more likely to be involved in volunteering and to attend school events (Arnold, Zeljo, Doctoroff, & Ortiz, 2008; Durand, 2011).

Work hours

Parents’ weekly work hours (mean-centered) were included as a control, given that working more hours (Weiss et al., 2003) and interfering work schedules (Hindman et al., 2012) have been linked less school involvement. Additionally, Fantuzzo, Perry, and Childs (2006) found that parents who worked full time were less satisfied with their children’s educational programs than those who worked less than full time.

Child age

We included children’s age, in months (mean-centered), as a control. We suspected that parents of younger children (or children in their first year of kindergarten) might be more involved than parents of older children, in light of prior research showing that parents may be particularly invested in school involvement during the initial transition to kindergarten (McIntyre, Eckert, Fiese, DiGennaro, & Wildenger, 2007).

School type

Parents were asked to indicate whether their child attended a public or private preschool. School type was dummy coded such that 1 = public and 0 = private school. We controlled for school type based on research suggesting that insomuch as parents who send their children to private school chose that school (i.e., over public school, and possibly other private school options), they may be more satisfied with their children’s schools (Warner, 2010) and more engaged in these schools (Goldring & Philips, 2008). Notably, some research (e.g., Hashmi & Akhter, 2013) has found few differences in parent involvement by school type.

Analytic Strategy

Since we examined partners nested in couples, it was necessary to use a method that would account for the within-couple correlations in the outcome scores. Multilevel modeling (MLM) permits examination of the effects of individual and dyad level variables, accounts for the extent of the shared variance, and provides accurate standard errors for testing the regression coefficients relating predictors to outcome scores (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). MLM adjusts the error variance for the interdependence of partner outcomes within the same dyad, which results in more accurate standard errors and associated hypothesis tests. Another methodological challenge is introduced in the study of dyads when there is no meaningful way to differentiate the two dyad members (e.g., male/female). In this case, dyad members are considered to be exchangeable or interchangeable (Kenny et al., 2006). The multilevel models tested were two-level random intercept models such that partners (Level 1) were nested in couples (Level 2; see Smith, Sayer, & Goldberg, 2013). To deal with intracouple differences, the Level-1 model was a within-couples model that used information from both members of the couple to define one parameter—an intercept, or average score—for each couple. This intercept is a random variable that is treated as an outcome variable at Level 2. Predictors that differed within couples (e.g., work hours) were entered at Level 1. Predictors that varied between couples (e.g., child age) were entered at Level 2. Continuous predictors were grand mean-centered and dichotomous variables were dummy coded (0, 1). Interactions were created by multiplying mean-centered continuous variables and dummy-coded dichotomous variables. For each of the three outcomes, we estimated a final, more parsimonious model in which we trimmed nonsignificant predictors and included only predictors that were statistically significant (p < .05) and those whose absence caused a predictor to fall above the p < .05 level. Effect sizes are not presented, as it is not possible to get reliable effect size estimates for multilevel models examining cross-sectional dyadic data, due to the unreliability of the variance estimates provided by those models (Raudenbush, 2008; Smith et al., 2013). Data were missing for 4 partners (2 lesbian, 2 gay) in the 68 couples. For all analyses there were 132 persons nested in 68 couples.

Results

Descriptive Findings

Descriptive statistics for all continuous and dichotomous predictors and controls, and the continuous outcomes, for the full sample and by parent gender, are in Table 1. For individual level variables, in which there were two reports per couple (e.g., work hours), we used MLM to examine differences by gender. Regarding the predictors, outness with other parents differed by parent gender, such that men reported being more out than women, χ2 (1, 132) = 5.54, p = .022: 85% of men reported being very out, compared to 67% of women. Regarding the outcomes, school satisfaction differed by parent gender, F(1, 67) = 5.44, p = .023, with men reporting higher satisfaction (M = 3.30, SE = .06) than women (M = 3.10, SE = .05).

Intercorrelations among predictor and outcome variables are in Table 2. Parents’ perception of school stigma was highly correlated with perceived exclusion by parents, r = .54, and moderately correlated with perceived community homophobia, r = .30. There were small correlations between perceived exclusion by parents and community homophobia, r = .18, and perceived exclusion by parents and outness with parents, r = −.23.

Multilevel Model Predicting Parent Involvement

In the MLM model predicting parent involvement, perceived school stigma, perceived community homophobia, perceived exclusion by parents, outness with parents, and gender were entered as predictors (Table 3). The following controls were also included: child age, school type, parent education, family income, and parent work hours. Our hypotheses were partially supported. In this main effects model, community homophobia was positively related to involvement, such that parents who perceived their communities as more homophobic reported being more involved, β = .15, SE = .06, t(112) = 2.26, p = .026 (H2A). Perceived exclusion by other parents was negatively related to involvement, such that parents who perceived higher levels of exclusion reported being less involved, β = −.20, SE = .07, t(110) = −2.77, p = .007 (H3A). Regarding the controls, parents of younger children, β = −.005, SE = .001, t(63) = −3.62, p = .001, and parents who worked fewer hours, β = −.007, SE = .002, t(90) = −2.57, p = .012, reported being more involved. School stigma, outness, and parent gender were unrelated to involvement. Of the controls, school type, education, and income were unrelated to involvement.

Table 3.

Multilevel Models with Parent Engagement Subscales as Outcomes

| Predictors | Parent Involv (PI) β (SE) | PI with inter β (SE) | PI trim β (SE) | Par- Teach Rel (PTR) β (SE) | PTR with inter β (SE) | PTR trim β (SE) | School Sat (SS) β (SE) | SS with int β (SE) | SS trim β (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1.95 (.12)*** | 1.93 (.13)*** | 2.19 (.05)*** | 3.41 (.13)*** | 3.36 .13)*** | 3.40 (.12)*** | 3.21 (.10)*** | 3.22 (.11)*** | 3.29 (.06)*** |

| Child age | −.005 (.001)*** | −.005 (.001)*** | −.005 (.001)*** | −.001 (.01) | .001 (.01) | −.002 (.01) | −.002 (.001) | ||

| School type | .13 (.10) | .12 (.10) | .12 (.10) | .10 (.10) | .08 (.08) | .09 (.08) | |||

| Family income | −.001 (.001) | −.001 (.001) | .002 (.007) | .002 (.06) | .006 (.006) | .006 (.006) | .004 (.005) | ||

| Parent education | .07 (.06) | .08 (.06) | −.06 (.06) | −.04 (.06) | −.04 (.05) | −.05 (.05) | |||

| Parent work hours | −.007 (.002)* | −.007 (.002)*** | −.007 (.002)** | −.003 (.003) | −.002 (.003) | −.003 (.002) | −.003 (.002) | ||

| Parent gender | .13 (.12) | .12 (.12) | −.08 (.12) | −.11 (.12) | −.15 (.10) | −.15 (.10) | −.15 (.09) | ||

| School stigma | .02 (.09) | .03 (.09) | −.21 (.09)* | −.20 (.09)* | −.17 (.08)* | −.20 (.07)** | −.20 (.07)** | −.21 (.06)** | |

| Community homophobia | .15 (.06)* | .15 (.06)* | .13 (.05)* | .13 (.07) | .12 (.07) | .009 (.05) | .01 (.05) | ||

| Parent exclusion | −.20 (.07)** | −.09 (.14) | −.19 (.06)** | −.29 (.08)** | −.02 (.16) | −.03 (.14) | −.15 (.09) | −.16 (.11) | −.11 (.05)* |

| Outness to parents | .14 (.11) | .16 (.11) | −.06 (.11) | −.005 (.12) | .004 (.11) | .04 (.09) | .03 (.09) | ||

| Parent exclusion x outness to parents | −.15 (.15) | −.36 (.16)* | −.38 (.17)* | .08 (.12) |

Note: Inter = Interactions; Trim = Trimmed

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Next, we tested the interaction between perceived exclusion by other parents and outness with other parents. The interaction was not significant. We then trimmed each predictor, one by one, from the least significant to the most significant, retaining anything in the final trimmed model with p < .05 or whose absence caused a predictor to lose significance. In this final model, all of the predictors that were statistically significant remained significant and no non-significant predictors gained significance.

Multilevel Model Predicting Parent-Teacher Relationships

In the MLM model predicting parent-teacher relationships, the same set of predictors and controls were included (Table 3). In this main effects model, perceived school stigma was negatively related to parent-teacher relationships, such that parents who reported higher stigma reported poorer relationships, β = −.21, SE = .09, t(106) = −2.18, p = .032 (H1B). Additionally, perceived exclusion by parents was negatively related to parent-teacher relationships, such that parents who perceived more exclusion reported poorer relationships, β = −.29, SE = .08, t(114) = −3.39, p = .001 (H3B). The following predictors were nonsignificant: community homophobia, outness, and parent gender. None of the controls (child age, school type, education, income, work hours) were significant.

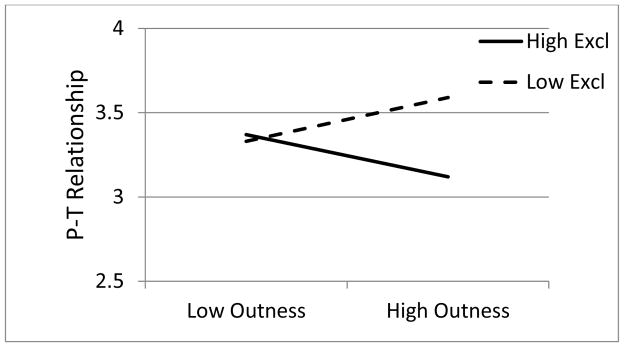

Next, we tested the interaction between perceived exclusion by other parents and outness with other parents. The interaction was significant, β = −.36, SE = .16, t(115) = −2.03, p = .046. In this model, perceived school stigma continued to be significant, but perceived exclusion by other parents was not. In our final trimmed model, perceived school stigma continued to be significant (p = .048); additionally, the exclusion x outness interaction was significant, β = −.38, SE = .17, t(124) = −2.14, p = .034 (H5B). Graphing the interaction revealed that the effect of outness was dependent on exclusion, such that parents who were very out and perceived high levels of exclusion reported the poorest relationships with teachers, whereas parents who were very out and perceived low levels of exclusion reported the best relationships with teachers (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Interaction of Parents’ Outness to Parents with Perceived Exclusion by Other Parents on Parent-Teacher Relationship Quality

Multilevel Model Predicting School Satisfaction

In the MLM model predicting school satisfaction, the same set of predictors and controls were included (Table 3). Perceived school stigma was negatively related to satisfaction, such that parents who reported higher levels of stigma reported lower satisfaction, β = −.20, SE = .07, t(112) = −2.85, p = .005 (H1C). No other predictors were statistically significant.

We tested the exclusion x outness interaction, which was not significant. As with the prior models, we trimmed the predictors from least to most significant. In the final trimmed model, perceived school stigma remained significant (p = .002) and perceived exclusion by other parents emerged as significantly and negatively related to the outcome, β = −.11, SE = .05, t(63) = −2.06, p = .042. Both parent gender and family income were included in this final trimmed model, since both were significant when entered alone (i.e., male same-sex parents and parents with higher incomes were more satisfied), but these effects became nonsignificant when both variables were in the model together.

Discussion

The current study is one of the first to examine how perceptions of openness and acceptance in the broader social context relate to same-sex parents’ school experiences. Our findings have implications for scholars and professionals seeking to understand the consequences of perceived exclusion and rejection for sexual minority parents and their children.

We found that perceptions of school stigma were related to school satisfaction, such that parents who perceived school personnel, teachers, and the curriculum as less inclusive of same-sex parent families reported less enthusiastic endorsements of their children’s schools. In that dissatisfaction with schools may prompt relocation and/or school transfer (Hornby, 2011), parents who report greater school dissatisfaction may be more likely to seek out alternative schools for their children, either mid-year or for the next academic year. Future work should examine the long-term implications of school dissatisfaction for same-sex parents.

Perceptions of school stigma were also related to parent-teacher relationships, such that same-sex parents who viewed their children’s schools as more stigmatizing and less inclusive were at risk for developing poorer relationships with teachers, which may ultimately interfere with their children’s academic (Powell, Son, File, & San Juan, 2010) and social (Serpell & Mashburn, 2012) development. Indeed, if parents feel negatively about their children’s teachers, they may be less likely to seek out or value their input about their children’s development or progress, which may negatively impact their children (Hornby, 2011).

Contrary to expectation, perceived stigma in the school was not positively related to parent involvement. Yet, at a broader level, perceived community homophobia was related to greater school involvement. Thus, while perceptions of homophobia in the immediate school community may not have the effect of rousing same-sex parents to proactively engage themselves in their children’s schools, perceptions of homophobia in the community in which they live may prompt parents to consider the possibility of – and thus seek to avoid – a negative response to their family within the school. Perhaps parents who live in communities that they view as homophobic are used to playing the role of self-advocate; that is, they may be accustomed to having to fight for their family’s rights (Goldberg et al., 2014). By serving on school committees, chaperoning field trips, and attending school events, same-sex parents boldly announce themselves to schools and also establish themselves as valuable members of the school community. Their efforts may have the effect of reducing discomfort on the part of school personnel, thus improving the school climate for same-sex parent families (Byard et al., 2013).

In terms of relationships with other parents, we found that parents who perceived higher levels of exclusion by other parents reported being less involved in the school – a finding that is consistent with research on members of other (e.g., racial) minority groups (Simoni & Perez, 1995). Thus, parents who view other parents as unwelcoming may be less inclined to involve themselves in school activities out of a desire to avoid negative treatment or uncomfortable situations (Hindman et al., 2012). Of course, given the cross-sectional nature of the data, other explanations are possible. Perhaps same-sex parents who are less involved have fewer opportunities to get to know other parents, and to establish a sense of communion with them; in turn, they may view other parents as less welcoming.

Notably parents’ outness with other parents was not directly related to any of the school engagement outcomes. Rather, we found that the effect of parents’ outness on their self-reported relationships with teachers depended upon their perceptions of acceptance versus exclusion by other parents, such that parents who were very out, and perceived high levels of exclusion, reported the poorest quality relationships with teachers. We suspect that same-sex parents who are more out with other parents may be more negatively affected by perceived exclusion, as they may be more likely to attribute perceived rejection to their sexual orientation and, in turn, to feel less connected to their children’s classrooms – and in turn their children’s teachers. Likewise, parents who were very out with other parents, and who perceived high levels of acceptance (low levels of exclusion) by other parents, reported the most positive relationships with teachers, suggesting the significance of parents’ relationships with other parents in creating a sense of community that can foster school connectedness and engagement (Ryan & Martin, 2000). Of course, given the cross-sectional nature of the study, other explanations are possible. For example, parents may report better relationships with teachers who actively foster other parents’ acceptance. Longitudinal research that assesses parents at various points during the school year may be able to clarify the directionality of these relationships.

Notably, gender was not related to parent engagement, once other factors were taken into account, in contrast to some research with heterosexual couples (Coyl-Shepherd & Newland, 2013). Rather, both male and female same-sex couples demonstrated high levels of involvement in their children’s schools, which is somewhat consistent with some prior work showing that (a) both male and female same-sex couples show higher levels of coparenting than heterosexual couples, and (b), there do not appear to be differences between male and female couples in the degree to which they share parenting responsibilities (Farr & Patterson, 2013; Goldberg et al., 2012). Their high, and similar, levels of involvement may also reflect their status as adoptive parents; couples who adopt tend to exhibit a very high level of motivation to become parents, which may predispose them toward an intensive, involved style of parenting (Goldberg, 2010).

The focus of the current study was on factors that are unique to same-sex couples with children which may affect their school engagement. However, it is notable that many of our findings are consistent with prior research on heterosexual parents. Parents of younger children (McIntyre et al., 2007) and parents who worked fewer hours (Hindman et al., 2012) reported greater involvement. In that parents who work more hours and have less flexible schedules have less time to devote to school-based activities, research should seek to establish how to effectively engage working parents without significantly adding to their workload (Hornby, 2011).

Limitations and Conclusions

This study was cross-sectional, which limits our ability to draw conclusions about causality. Perhaps same-sex parents who are more highly engaged in their children’s schools develop more positive relationships with, and thus more positively evaluate, other parents (i.e., they view them as more accepting) rather than the other way around. The self-report nature of the data is also a limitation. Obtaining data on parents’ school involvement from teachers, as some research has done (El Nokali et al., 2010), would have enhanced the study. While the reliability of the multi-item self-report instruments was adequate (Cronbach’s alpha > .70), it was less than ideal. Better instruments should be developed and tested in more diverse samples. We also relied on single-item measures, with unknown psychometric properties, to assess perceived community homophobia and outness with other parents. These constructs may not be adequately captured via single-item measures. Future work should utilize multi-item measures, as well as examining our single-item measures alongside established measures to determine their validity.

The sample was relatively affluent and well-educated. This necessarily shaped important aspects of same-sex parents’ school experiences, such that they likely had some choice as to where they lived, thus limiting their exposure to homophobia in their schools and communities. Further, the male same-sex couples in the sample had particularly high levels of affluence. This finding is likely a sampling artifact: National data on same-sex adoptive parents show that same-sex male and same-sex female couples have similar family incomes (both about $102,000; Gates et al., 2007). Also, parents living on the West and East Coasts were overrepresented; indeed, there is evidence that many same-sex couples who are raising children live in the Midwest and South (Gates, 2013). The sample was relatively out to other parents about their sexual orientation, overall, which may have in part been a function of where they lived, and their access to relatively gay-friendly communities. Future work should aim to recruit a sample of parents that is more variable with regard to both geographic region and outness. In addition, the current sample all adopted their children. It is difficult to know whether these findings generalize to planned same-sex parent families with biological children (e.g., children conceived via reproductive technologies). Likewise, most of the parents in the sample were Caucasian whereas their children were of color. Although this feature of our sample is similar to that of national samples of same-sex adoptive parents (Gates et al., 2007), unknown is how the racial aspects of these families impacts parents’ school engagement; future research should address this.

Despite these limitations, our study provides insight into the kinds of supportive versus rejecting contexts that may shape, or interact with, same-sex parents’ perceptions of and relationships with their children’s schools. As children of same-sex parents grow older, they increasingly report instances of homophobia at school (Byard et al., 2013). In turn, it is important to understand the types of factors that are likely to facilitate more positive parent engagement with schools early on, as such early relationships may set the stage for long-term patterns (Beveridge, 2005). Efforts to reduce sexual orientation-related stigma in school and non-school contexts have direct and indirect implications for same-sex parent families. In addition to positively impacting parent and child well-being (Goldberg, 2010), improved community and school climate will likely encourage more positive relationships between same-sex parent families and schools, which has the capacity to benefit parents and their developing children.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by several grants, awarded to the first author: Grant# R03HD054394, from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development; the Wayne F. Placek award, from the American Psychological Foundation; and a Small Grant, from the Spencer Foundation.

Contributor Information

Abbie E. Goldberg, Email: agoldberg@clarku.edu, Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, 950 Main St, Worcester MA 01610, 508 793 7289

JuliAnna Z. Smith, Email: julianns@acad.umass.edu, Methodology Consultant, Center for Research on Families, University of Massachusetts, Amherst MA 01003

References

- Arnold D, Zeljo A, Doctoroff G, Ortiz C. Parent involvement in preschool: Predictors and the relation of involvement to preliteracy development. School Psychology Review. 2008;37:74–90. [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge S. Children, families, and schools: Developing partnerships for inclusive education. London, England: Routledge Falmer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The ecology of developmental processes. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 1: Theoretical models of human development. 5. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 993–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Byard E, Kosciw J, Bartkiewicz M. Schools and LGBT-parent families: Creating change through programming and advocacy. In: Goldberg AE, Allen KR, editors. LGBT-parent families: Innovations in research and implications for practice. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 275–290. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Unpublished technical report. 1995. Technical reports for the construct development for the measures for Year 2 outcome analyses. [Google Scholar]

- Coyl-Shepherd DD, Newland L. Mothers’ and fathers’ couple and family contextual influences, parent involvement, and school-age child attachment. Early Child Development & Care. 2013;183:553–569. [Google Scholar]

- Culp A, Hubbs-Tait L, Culp R, Starost HJ. Maternal parenting characteristics and school involvement: Predictors of kindergarten cognitive competence among Head Start children. Journal of Research in Childhood Education. 2001;15:5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dearing E, Kreider H, Weiss HB. Increased family involvement in school predicts improved child-teacher relationships and feelings about school for low-income children. Marriage and Family Review. 2008;43:226–254. [Google Scholar]

- Durand T. Latino parental involvement in kindergarten: Findings from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2011;33:469–489. [Google Scholar]

- El Nokali N, Bachman H, Votruba-Drzal E. Parent involvement and children’s academic and social development in elementary school. Child Development. 2010;81:988–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, Tighe E, Childs S. Family involvement questionnaire: A multivariate assessment of family participation in early childhood education. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2000;92:367–376. [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, Perry M, Childs S. Parent Satisfaction with Educational Experiences scale: A multivariate examination of parent satisfaction with early childhood education programs. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2006;21:142–152. [Google Scholar]

- Farr R, Patterson C. Coparenting among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual couples: Associations with adopted children’s outcomes. Child Development. 2013;84:1226–1240. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassinger RE. From invisibility to integration: Lesbian identity in the workplace. Career Development Quarterly. 1995;44:148–167. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S, Wright A. Dual impact: Outness and LGB identity formation on mental health. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2013;25:443–464. [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Meyer IH. Internalized homophobia and relationship quality among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:97–109. doi: 10.1037/a0012844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates G. LGBT parenting in the United States. 2013 Retrieved from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LGBT-Parenting.pdf.

- Gates G, Ost J. The gay and lesbian atlas. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gates G, Badgett MVL, Macomber JE, Chambers K. Adoption and foster care by gay and lesbian parents in the United States. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- GLSEN & Harris Interactive. The principal’s perspective: School safety, bullying and harassment, A survey of public school principals. New York: Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AE. Lesbian and gay parents and their children: Research on the family life cycle. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AE, Smith JZ, Perry-Jenkins M. The division of labor in lesbian, gay, and heterosexual new adoptive parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74:812–828. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AE, Weber ER, Moyer AM, Shapiro J. Seeking to adopt in Florida: Lesbian and gay parents navigate the legal process. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. 2014;26:37–69. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AE, Smith JZ. Preschool selection considerations and experiences of school mistreatment among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual adoptive parents. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2014;29:64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring E, Phillips K. Parent preferences and parent choices: The public-private decision about school choice. Journal of Education Policy. 2008;23:209–230. [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow C. The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools. 1993;30:79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi A, Akhter M. Assessing the parental involvement in schooling of children in public/private schools, and its impact on their achievement at elementary level. Journal of Educational Research. 2013;16:27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Herbstrith J, Tobin R, Hesson-McInnis M, Schneider J. Pre-service teacher attitudes toward gay and lesbian parents. School Psychology Quarterly. 2013;28:183–194. doi: 10.1037/spq0000022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindman A, Miller A, Froyen L, Skibbe L. A portrait of family involvement during Head Start: Nature, extent, and predictors. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2012;27:654–667. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover-Dempsey KV, Sandler HM. Parental involvement in children’s education: Why does it make a difference? Teachers College Record. 1995;97:310–331. [Google Scholar]

- Hornby G. Parent involvement in childhood education: Building effective school-family partnerships. New York: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D, Kashy K, Cook W. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kinkler LA, Goldberg AE. Working with what we’ve got: Perceptions of barriers and supports among same-sex adopting couples in non-metropolitan areas. Family Relations. 2011;60:387–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00654.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl G, Lengua L, McMahon R the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Parent involvement in school: Conceptualizing multiple dimensions and their relations with family and demographic risk factors. Journal of School Psychology. 2000;38:501–523. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(00)00050-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Diaz EM. Involved, invisible, ignored: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender parents and their children in our nation’s K-12 schools. New York: Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw J, Palmer NA, Kull RA. Reflecting resiliency: Openness about sexual orientation and/or gender identity and its relationship to well-being and educational outcomes for LGBT students. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9642-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legate N, Ryan R, Weinstein N. Is coming out always a ‘good thing’? Exploring the relations of autonomy support, outness, and wellness for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Social Psychology & Personality Science. 2012;3:145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Levine-Rasky C. Dynamics of parent involvement at a multicultural school. British Journal of Sociology of Education. 2003;30:331–344. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay J, Perlesz A, Brown R, McNair R, de Vaus D, Pitts M. Stigma or respect: Lesbian-parented families negotiating school settings. Sociology. 2006;40:1059–1077. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre L, Eckert T, Fiese B, DiGennaro F, Wildenger L. The transition to kindergarten: Family experiences and involvement. Early Childhood Education Journal. 2007;35:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Mercier LR, Harold RD. At the interface: Lesbian-parent families and their children’s schools. Children & Schools. 2003;25:35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer I. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual pop-populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–97. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J, Balsam K, Rothblum E. Lesbian and bisexual mothers and nonmothers: Demographics and the coming-out process. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:144–156. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon C. Working-class lesbian parents’ emotional engagement with their children’s education: Intersections of class and sexuality. Sexualities. 2011;14:79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Palm G, Fagan J. Father involvement in early childhood programs: Review of the literature. Early Child Development and Care. 2008;178:745–759. [Google Scholar]

- Powell DR, Son SH, File S, Jan Juan R. Parent-school relationships and children’s academic and social outcomes in public school pre-kindergarten. Journal of School Psychology. 2010;48:269–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragins BR. Sexual orientation in the workplace: The unique work and career experiences of gay, lesbian and bisexual workers. Research in Personnel & Human Resource Management. 2004;23:37–122. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW. Many small groups. In: de Leeuw J, Meijer E, de Leeuw J, Meijer E, editors. Handbook of multilevel analysis. New York, NY: Springer; 2008. pp. 207–236. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan D, Martin A. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender parents in the school systems. School Psychology Review. 2000;29:207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Serpell Z, Mashburn A. Family–school connectedness and children’s early social development. Social Development. 2012;21:21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon S. Parents’ social networks and beliefs as predictors of parent involvement. The Elementary School Journal. 2002;102:301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Simoni J, Perez L. Latinos and mutual support groups: A case for considering culture. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1995;63:440–445. doi: 10.1037/h0079697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JZ, Sayer A, Goldberg AE. Multilevel modeling approaches to the study of LGBT parent-families. In: Goldberg AE, Allen K, editors. LGBT-parent families: Innovations in research and implications for practice. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 307–23. [Google Scholar]

- US Census. Metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/metro/

- Waanders C, Mendez JL, Downer J. Parent characteristics, economic stress, and neighborhood context as predictors of parent involvement in preschool children’s education. Journal of School Psychology. 2007;45:619–636. [Google Scholar]

- Warner C. Emotional safeguarding: Exploring the nature of middle-class parents’ school involvement. Sociological Forum. 2010;25:703–724. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss H, Mayer E, Kreider H, Vaughan M, Dearing E, Pinto K. Making it work: Low-income working mothers’ involvement in their children’s education. American Education Research Journal. 2003;40:879–901. [Google Scholar]