Abstract

Optical imaging has made it possible to monitor response to anticancer therapies in tumor xenografts. The concept of treating breast cancers with 131I is predicated on the expression of the Na+/I symporter (NIS) in many tumors and uptake of I in some. The pattern of 131I radioablative effects were investigated in an MCF-7 xenograft model dually transfected with firefly luciferase and NIS genes. On Day 16 after tumor cell implantation, 3 mCi of 131I was injected. Bioluminescent imaging using d-luciferin and a cooled charge-coupled device camera was carried out on Days 1, 2, 3, 7, 10, 16, 22, 29, and 35. Tumor bioluminescence decreased in 131I-treated tumors after Day 3 and reached a nadir on Day 22. Conversely, bio-luminescence steadily increased in controls and was 3.85-fold higher than in treated tumors on Day 22. Bioluminescence in 131I-treated tumors increased after Day 22, corresponding to tumor regrowth. By Day 35, treated tumors were smaller and accumulated 33% less 99mTcO4 than untreated tumors. NIS immunoreactivity was present in <50% of 131I-treated cells compared to 85–90% of controls. In summary, a pattern of tumor regression occurring over the first three weeks after 131I administration was observed in NIS-expressing breast cancer xenografts.

Keywords: Bioluminescence, luciferase, sodium iodide symporter, NIS, breast cancer, radioabalation

Introduction

Cells with I -accumulating properties are potential targets for 131I radioablative therapy. The clinical utility of this unique mechanism has been recognized for many decades in the context of the thyroid gland, particularly in the treatment of hyperthyroidism and thyroid cancer metastasis [1–3]. Interest in I transport has grown following the sequencing and characterization of the sodium iodide symporter (Na+/I symporter [NIS]) [4], an integral membrane glycoprotein localized along the basolateral membrane of thyrocytes, gastric mucosa, salivary gland, and lactating mammary cells [5, 6]. These molecular advances have made it possible to use NIS as a reporter gene [7–10] and test its potential for gene-delivered therapy [11–13].

The generation of anti-NIS antibodies facilitated the identification of NIS protein expression across many tissues [5, 6, 14]. Thus, varying degrees of NIS expression were detected in a majority of invasive and in situ carcinomas of the breast [6]. However, the presence of protein expression does not imply active I transport, because the prerequisite for isotope uptake is localization of NIS in the plasma membrane. Despite observations that NIS immunoreactivity is predominantly intracellular in human primary and metastatic breast cancers, in vivo accumulation of radioiodides has been demonstrated on nuclear scans in some cases [15, 16]. These findings have encouraged and fostered investigations in the area of NIS-mediated 131I radioablative therapy.

Little is known of the time course of radiation-induced cellular changes and cell death in response to intracellular accumulation of 131I. Clinically, radioablation has been used for decades to eradicate remnant thyroid cervical tissue or treat thyroid cancer metastasis. The effects of 131I are monitored indirectly over a period of months through clinical examinations, serum thyroglobulin levels, and reimaging of patients to determine tumor response [1]. Because human breast cancers could potentially be targeted with 131I, the development of a preclinical model to evaluate the pattern and time course of tumor response may be useful to guide future applications of NIS-based therapies. Overall breast cancers are radiosensitive, but susceptibility to radiation may vary by tumor phenotype as shown in cell lines [17–19]. Therefore, the tumor model described herein provides insight into the timing of maximal response and onset of tumor regrowth.

New optical imaging modalities have facilitated the process of in vivo monitoring of molecular and cellular events in animal tumor models [20, 21]. Specifically, photoproteins encoded by firefly luciferase (Fluc) gene can be engineered into cells resulting in the biosynthesis of luciferase enzyme, which will emit photons or luminescence upon catalysis of d-luciferin [22]. This signal is captured by a cooled charge-coupled device (CCD) camera as a pseudocolor image and superimposed onto a grayscale picture of the mouse [20, 23]. Bioluminescent imaging has thus made it possible to perform serial imaging of small animals to observe biological processes in vivo without sacrificing mice at different time points [21, 23–25]. By comparison, the resolution of scintigraphic images of small animals injected with 131I is poor and subject to the limitations of its half-life. Furthermore, tumor viability can only be assessed as a function of I accumulating capacity.

Significant endogenous expression of NIS associated with avid accumulation of I has not been identified in any human breast cancer cell lines. For this reason, MCF-7 cells were dually stably transfected with NIS and a replication-deficient lentiviral vector carrying the Fluc gene under the control of cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter [25]. Herein we report the effect of 131I therapy over time on human breast cancers xenografts. We postulated that bioluminescent flux would be representative of tumor volume and that signaling would remain stable or diminish as a function of tumor growth inhibition or tumor regression induced by 131I.

Methods

NIS Transfection of MCF-7

MCF-7, an estrogen-responsive human breast cancer cell line, was cultured in DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were then transfected with pcDNA 3.1 plasmid containing human NIS cDNA (kindly obtained from Dr. Nancy Carrasco at Albert Einstein College of Medicine) by using Lipofect-amine 2000 (Invitrogen, Inc, Carlsbad, CA) and selected with 1000 µg/mL G418 (Clontech, Inc, Mountain View, CA). After 2 weeks, cultured cells were split in 96-well plates to obtain single clones. Forty-eight single colonies were screened for NIS activity by evaluating I transport using 99mTcO4.

Luciferase Transfection

The lentiviral vector CS-CMV Fluc was used to transform NIS-transfected MCF-7 cells with Fluc reporter gene for optical imaging of tumor cell activity. The viral construct was made by replacing the GFP with 1.7 kb Fluc gene under the internal CMV promoter of the original CS-CG lentiviral backbone [25]. Viral particles were produced by using standard calcium phosphate transfection method in human embryonic kidney fibroblast (293T) cells. Harvested viruses were collected and purified using ultracentrifugation.

Iodide Uptake Assay

Cells were washed three times with HBSS after medium was removed and then incubated with HBSS–HEPES + 50 µCi 99mTcO4 and 10 µM NaI for 2 hr at 37 °C. Per-chlorate inhibition (selective block of I transport) was carried out in parallel. After all iodide-containing solutions were thoroughly washed, cells were treated with 1% NP-40 cell lysis buffer to release intracellular radioactivity. Counts were measured on a Packard Cobra γ-counter and normalized to radioactivity counts per microgram protein (cpm/µg protein). Total cellular protein content was calculated by use of the protein assay reagent (BCA Protein Assay, Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Luciferase Activity

Luciferase activity was evaluated in selected clones by the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay system (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). Briefly, after removal of culture media, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with 100 µL passive lysis buffer in an orbital shaker for 15 min. The lysate was centrifuged and analyzed for luciferase reporter activity with the Luciferase Assay II Reagent (LAR II). Readings were carried out with a TD 20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA), noted as relative light units (RLU) and reported as RLU per minute per microgram protein (RLU min−1 µg protein−1). For in vitro bioluminescence studies, 100,000 cells of selected single clones with both NIS and Fluc activity were plated in duplicate 24-well tissue culture plates. The next day, the medium was aspirated, washed once with PBS and incubated with d-luciferin (Biosynth International, Inc, Naperville, IL) at a concentration of 150 µg/mL in PBS. Cells were then imaged in their well plates on the Xenogen IVIS 100 (Xenogen Inc., Alameda, CA) camera. Clonal selection involved selecting single-cell colonies analyzed for both high I uptake capacity as well as high firefly luciferase signal.

Tumor Xenografts and 131I Therapy

Stably transfected NIS-Fluc–MCF-7 cells were cultured until 75% confluent, trypsinized, washed in cold HBSS, and counted. Cells were resuspended with HBSS + 0.04% DNAse I (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Four- to five-week-old female nude mice Ncr-nu (Taconics, Germantown, NY) were injected subcutaneously with 2 × 106 cells with 100 µL Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) on their right or left dorsal flanks as approved by the Stanford University Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care. Simultaneously, an estradiol pellet (SE-121, 0.72 mg, 60-day release) and a thyroxine pellet (ST-131, 0.05 mg, 90-day release) were implanted in each mouse (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL), the latter for the purpose of down-regulating thyroid NIS and thyroidal I uptake.

Tumors were measured in two dimensions and the third measurement (height of tumor) was closely approximated. Volume was calculated using the formula for a prolate ellipsoid [p/6(a × b × c)] [26]. Mice were divided into two groups of five mice each. The experimental group was injected with 3 mCi of 131I (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) via the tail vein 16 days after implantation of tumor cells. Serial bioluminescent monitoring began on this day, designated as Day 0, and continued for the next 36 days whereupon mice were euthanized.

In Vivo Optical Imaging

Bioluminescence was measured after an intraperitoneal injection of mice with 100 µL of 30 mg/mL of d-luciferin (Biosynth International). Imaging was carried out on a highly sensitive IVIS 100 CCD camera (Xenogen, Inc., Alameda, CA) and viewed in real time on a computer screen using a color scale expressed as total flux (photons per second per square centimeter per steradian [photons sec−1 cm−2 sr−1]). Mice were anesthetized with isofluorane and placed in the 37 °C warmed platform chamber with continuous 1.5% isofluorane administration via a nasal cone. Acquisition times of 1 and 10 sec were used and signal was measured in the region of interest (ROI) overlying the tumor. Serial readings were taken after each injection at 5, 10, 15, and 20 min. Maximum values obtained from each mouse at individual time points were averaged for each set and the mean values were compared over time. An identical ROI was taken in a remote area in the mouse to assess background bioluminescence.

Baseline readings were taken in all mice 9 days after implantation, when tumors were approximately 2 to 4 mm. Again on Day 16, a second pretreatment imaging was carried out. Serial bioluminescence was monitored at 5 hr after treatment and then on Days 1, 2, 3, 9, 16, 22, 29, and 36. Data were analyzed using Living Image® Version 2.5 software (Xenogen, Inc., Alameda, CA).

Posttreatment Iodide Tumor Uptake

Pertechnetate (100 µCi) was injected intraperitoneally 1 hr prior to euthanasia on Day 37 after 131I treatment. Partial necropsy of thyroid, tumor, and muscle was performed. Thyroid weights were estimated at 3 mg because of the difficulty of dissecting adherent thyroid tissue off the trachea. Organs were weighed and well counted (counts per milligram tissue) in a Packard Cobra Gamma Counter (140 kV, 10% window calibrated 99mTc). Counts were normalized to 1% of injected dose.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Tumors were fixed in formalin and tissue sections were used for immunohistochemical studies. Sections were deparaffinated in xylene, hydrated through graded alcohols, and subjected to antigen retrieval with a rice steamer. The Catalyzed Amplification Kit (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) was employed as described before [6]. Slides were incubated for 15 min with affinity-purified antibody (Ab) (1:1000) generated against the last 16 amino acids of the C-terminal peptide (GHDGGRDQQETNL, corresponding to residues 631–643) of human NIS (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA). Immunoreactivity was graded according to the intensity of the peroxidase reaction using a 0 to 3+ scale.

Results

Clonal Selection

Multiple cell clones were tested and the clone with greatest I -accumulating capacity and high Fluc expression was selected. Specifically, a 100-fold greater uptake was noted as compared to perchlorate-inhibited NIS-transfected MCF-7 cells. Similarly, luciferase activity was measured as 3500 RLU µg−1 min−1 over negative control. The relative stability of transfection was verified after continuous propagation of cells in culture for 4 weeks. Reevaluation demonstrated an approximate decrease of 15% in NIS activity. Bioluminescence in these cells remained stable.

In Vivo Bioluminescence Studies

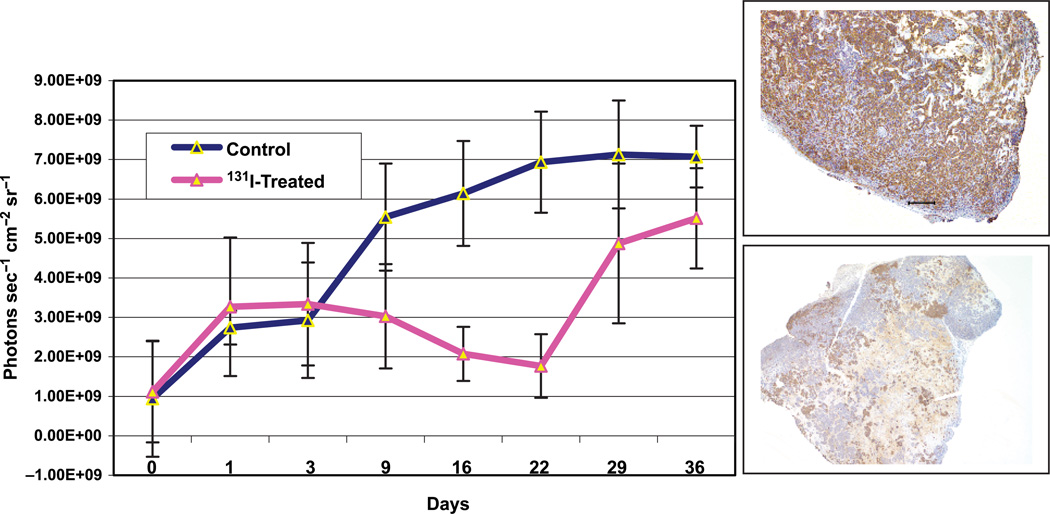

Baseline bioluminescence was measured in developing tumors 9 days after implantation, and again on Day 16 just prior to 131I administration. The latter was renamed Day 0 of treatment. Figure 1 depicts bioluminescence data over time for the two groups. The experimental or treated group demonstrated an increase in bioluminescence identical to that observed in the control group during the first three days. After Day 3, treated tumors showed a distinct downward trend in bio-luminescence through Day 22, decreasing from (3.65 ± 1.6) × 109 to 1.80 × 109 (± 0.75 × 108) photons sec−1 cm−2 sr−1. Contrastingly, a continuous rise in bioluminescence is observed from Days 3 to 22 in the control group, increasing from (3.00 ± 1.57) × 109 to (6.93 ± 2.45) × 109 photons sec −1 cm −2 sr−1. At their nadir, 131I-treated tumors had 51% less bioluminescence than the same tumors on Day 3. In contrast, control tumor bioluminescence increased by 2.31-fold in the same time frame but remained virtually the same through Day 36. Treated tumors grew rapidly after Day 22, achieving on Day 36 a final bioluminescence of (5.43 ± 1.54) × 109 photons sec−1 cm−2 sr−1 comparable to the untreated mouse tumors. The divergence in bioluminescent curves approached significance on Day 22, p = .026 (Figure 2A), when untreated tumors had 3.85-fold higher bioluminescence than treated tumors. The differences in each of the animal groups are illustrated in Figure 2B, which details computer-generated serial images obtained from one control and one treated mouse. In summary, the luciferase activity data obtained from these tumors indicate that NIS-mediated radio-ablative therapy results in tumor regression during the first three weeks followed by a regrowth phase indicated by increasing bioluminescence.

Figure 1.

Bioluminescent signaling in NIS-Luc –MCF-7 breast cancer xenografts. Baseline bioluminescence was recorded on Day 0 of treatment (16 postimplantation). Group B mice were treated with 3 mCi 131I on Day 16 (Day 0 of treatment in graph) postimplantation. Graph illustrates mean bioluminescent measurements. Control tumors exhibited increasing bioluminescence through Day 22, whereas treated tumors reached a nadir on Day 22 posttreatment, and then began on an upward trend. Inserted are microphotographs of a representative control tumor and treated tumor sections showing pattern of immunoreactivity to anti-human NIS antibody.

Figure 2.

Bioluminescent imaging of NIS-Luc – MCF-7 xenografts. (A) Bar graph comparing average tumor bioluminescent signal on Days 3 and 22, p = .026. Error bars represent SEM, n = 3. (B) Select serial images of one control and one treated nude mouse with NIS-positive and Fluc positive MCF-7 breast cancer tumor xenografts. Mice were imaged at time 0 (before injection of 3 mCi 131I in the experimental group), Days 1, 3, 9, 16, 22, 29, and 36. Increasing bioluminescence is clearly observed on Days 9 – 36 in the control tumor, whereas signal decreases from Day 9 through 22. In the experimental group, comparably high signals are seen on Days 29 and 36, indicating tumor regrowth.

Tumor Size

Tumors were first visible approximately 7 days post-implantation. Their irregular shape confounds the accuracy of in vivo tumor measurements. Therefore, calculations based on these three tumor diameters are at best approximations of actual tumor volume. Mean tumor volumes on Day 16 after 131I therapy were 86 mm3 for the control group versus 13.7 mm3 for treated mice, p = .02. Two of the five treated mice died with very tiny tumors (volumes 3.12 and 6.24 mm3), whereas another two showed tumor fibrosis and cellular apoptosis (Figure 3E). After Day 22, tumor regrowth was apparent in the experimental group, whereas tumor growth in controls began to plateau in this same time frame.

Figure 3.

Histological and immunohistochemical analysis of breast cancer xenografts. NIS immunoreactivity and associated bioluminescence (expressed as photons per second per square centimeter per steradian) in control (A, B) and 131I-treated tumors (C – H). (A) Highly cellular control tumor, 7.1 × 109; (B) NIS immunopositivity in approximately 90% of control tumor cells; (C) predominantly acellular treated tumor, 4.71 × 109; (D) higher magnification showing islands of NIS-positive cells; (E) focal area of apoptotic cells in treated tumor, 7.2 × 109; (F) lower magnification of tumor shown in (E) demonstrating focal necrosis and NIS-positive cells surrounded by NIS-negative tumor cells; (G) treated tumor showing at low magnification NIS-positive and NIS-negative cells, 5.76 × 109; (H) residual NIS-positive cells demonstrating plasma membrane immunoreactivity. Ruler represents 200 µm.

By the end of the study, mean tumor volume of control tumors was 58.5 ± 30.9 mm3 versus 14.1 ± 11.7 mm3 of treated mice ( p = .057). Final mean tumor weights also reflect a nonsignificant 2.4-fold difference between the two groups, 80.5 mg for controls (n = 3) versus 33.3 mg (n = 5) for treated mice (p = .26). A positive correlation was established between tumor volume and bioluminescent signaling in control tumors. On Day 16, the correlation coefficient was .95 based on in vivo tumor measurements. There was no correlation between bioluminescence and volume in treated mice because tumors encompass areas of necrosis and fibrosis.

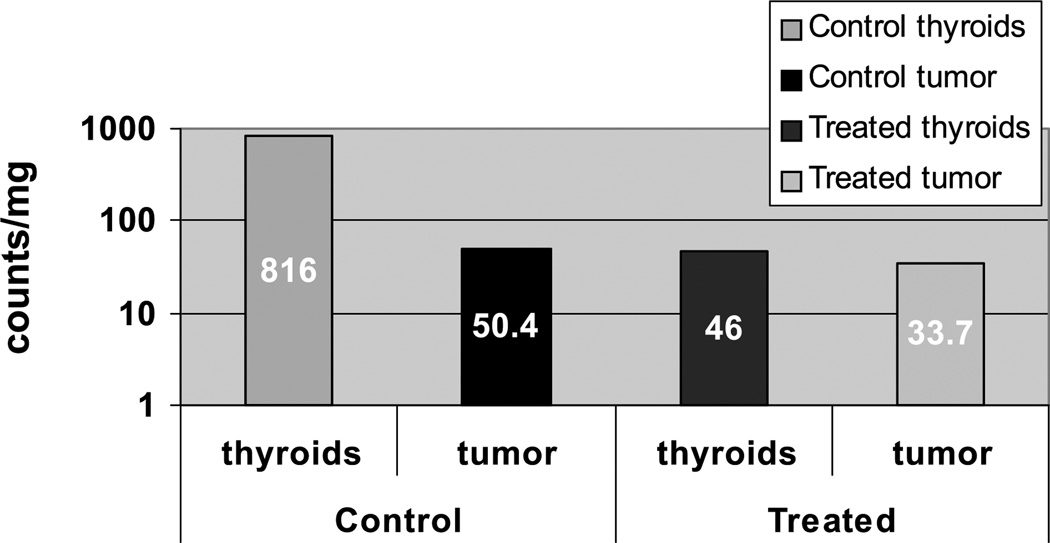

99mTcO4 Uptake Studies

Isotope accumulation was calculated in two control and three experimental mice, injected 2 hr prior to euthanasia. Two of the treated and one control animal died prior to this experiment, and the remaining control animals were not sacrificed. Sample well counts were expressed as counts per milligram tissue percent. Thyroid uptake was approximately 10.9-fold greater in the untreated controls than in mice treated with 131I, indicating only partial down-regulation of NIS-mediated I uptake with thyroxine treatment via implanted pellets (Figure 4). In other words, noncontrol thyroids showed 94% higher pertechnetate accumulation than treated thyroids. Less of a difference was noted in tumor tissue between the two groups, which can be attributed to tumor regrowth. Control tumors had 33% higher TcO4 uptake than treated tumors.

Figure 4.

Pertechnetate uptake in nude mice with NIS-Luc – MCF-7 xenografts. One hour after injecting 100 µCi 99mTcO4, mice were sacrificed on Day 36 and tissues well counted. Logarithmic scale illustrates the radioablative effects of 131I on thyroid and tumor tissue. In spite of tumor regrowth after Day 22 in treated mice, tumor tissue still had lower uptake than control tumors, whereas thyroid tissue showed a near-20-fold decrease in I accumulating activity.

Immunohistochemical Studies

Control tumor xenografts show high cellularity with 85–90% or more of cells exhibiting intense NIS immunopositivity including plasma membrane immunoreactivity (Figures 1 and 3A and B). Contrastingly, 131I treated tumors differ greatly both in their pattern of cellularity as well as in their pattern of NIS immunoreactivity (Figure 3C, D, and F–H). Foci of apoptosis were identified on hematoxylin–eosin stain as shown in Figure 3E. The pattern of NIS immunopositivity was not uniform in treated tumors. For example, one predominantly fibrotic, small tumor (volume 12.5 mm3) had residual small clusters of NIS-positive cells with NIS-negative tumor cells in the periphery of the tumor (Figure 3C and D). Another pattern is that shown in Figure 3G, where an equally small tumor has a very cellular composition with only half of the tumor cells expressing NIS. The combination of apoptosis and relative proliferation of NIS-negative cells in the treated tumors, provides evidence that NIS-expressing, Fluc-expressing cells were eliminated.

Discussion

The outcomes of 131I radioablative therapy in patients with thyroid cancer are well known [2, 27, 28]. The discovery of endogenous NIS expression in extrathyroidal cancers such as breast cancer and the possibility of using NIS gene transfer therapy for other malignancies have heightened interest in evaluating the effectiveness of 131I as an anticancer treatment. These experiments were designed to determine the onset, magnitude, and duration of 131I ablative effects in NIS-transfected MCF-7 xenografts exhibiting avid I uptake. MCF-7 cells were selected based on their extensive use in breast cancer research and NIS-related investigations.

Herein we coexpressed the luciferase reporter gene with human NIS to evaluate inhibition of tumor growth after the administration of 131I. We assumed that if in vitro cells retain over 85% to 100% of NIS and luciferase activity, respectively, then similar activity would remain operant in vivo. In this study we demonstrate correspondence between the downward trend in tumor bioluminescence and tumor growth inhibition or tumor regression in mice treated with 131I.

The timing of treatment of tumor xenografts may be a critical factor. We chose to deliver the therapy early during the steep growth phase of the tumor. Tumor volume and tumor weight were evaluated but are potentially inaccurate measures of tumor cell mass after radioablative therapy. This is clearly illustrated by our histologic findings wherein areas of necrosis, fibrosis, or cystic degeneration were noted in treated tumors. A large proportion of the remaining cells were NIS-negative suggesting that the elimination or arrested growth of NIS-positive cell population favored the growth of nontransfected cells or that radiation influenced the loss of NIS gene expression in remaining cells. By comparison, control tumors remained predominantly cellular and exhibit NIS immunopositivity in 85% to 90% of cells. It is possible that the magnitude of the therapeutic effect would be different with either earlier or later administration of radioablative therapy.

Detection of tumor bioluminescence signal may be confounded by several factors such as tumor perfusion, regional hypoxia, and large tumor size itself. Although bioluminescence does not accurately represent tumor mass or activity, it provides a relative measure and thus is a useful tool for serial monitoring of tumor xenografts. These observations offer insights into the patterns of cell death and the time course of radiation effects in human breast cancer xenografts ablated with 131I. Thus, in this study the treated tumors began to decrease in size, whereas untreated tumors continued in a pattern of growth so that on Day 22 the bioluminescence of control tumors was 3.85-fold higher than that of treated ones.

Extrathyroidal I accumulating cancers are not known to organify I in the manner of thyroid follicular cells. In spite of this, NIS-expressing cells or tumor xenografts respond to 131I radioablative therapy, even with short intracellular residence times [11, 29–31]. One possible explanation for the observed therapeutic effect may be the increased radiosensitivity of cancer cells, which may compensate for the shorter residence time of the radioisotope.

Pertechnetate uptake was evaluated at the end of the experiment confirming the presence of I accumulation in residual tumor, a finding that is congruent with the immunohistological studies showing residual NIS-positive cells. This suggests that repeat dosing with 131I or a higher dose may have increased the effectiveness of the radioablative treatment and tumor response. Thyroid I accumulation decreased 20-fold in treated mice to the level of tumor tissue. This reflects incomplete suppression of I transport by T4 therapy and consequent significant radioablative effects of 131I. The addition of methimazole and increased dose of T4/T3 treatments would be necessary for more effective down-regulation of thyroid I uptake [16]. Despite tumor re-growth in treated animals, pertechnetate accumulation in this group was one third lower than in control mice tumors at the end of the experiment. Of note, wild-type MCF-7 xenografts do not accumulate radioiodides, and tumor growth is not altered if mice receive a radioablative dose of 131I (data not shown).

Other factors, such as the biodistribution of isotope to the tumor tissue relative to other tissues, the accumulation of tracer, and the radiosensitivity of the cell, may influence the effectiveness of treatment in tumor xenografts [17]. Radiation-induced cell death depends not only on the rate and amount of uptake of radioisotope, but also on the residence time in the cell and the biologic radiosensitivity of the targeted cells. Moreover, tumor hypoxia may lower radiosensitivity of tumor cells further. Differences in tumor cells may account for differences in successful induction of irreversible cell damage [11, 31]. These experiments in conjunction with those of other investigators show that 131I can cause tumor cell death in the absence of organification [12, 32]. Ablation of malignant cells with 131I may occur in spite of short residence times if the cells are indeed more radiosensitive.

Evaluation of tumor response in mouse models is limited to in vivo tumor measurements or ex vivo measurement requiring the sacrifice of animals at different time points. Herein, serial bioluminescent imaging demonstrated a treatment-induced downward trend in tumor volume and provided insight into the timing of the maximal therapeutic effect in NIS-expressing, Fluc-expressing tumors targeted with 131I. This approach is practical, nontoxic, and preferable to serial scintigraphic imaging of mice. Nuclear scanning is inadequate to monitor the effects of 131I on tumor regression serially. Repeat imaging would naturally indicate sites of isotope retention and be limited by the physical half-life of the isotope. Alternatively, repeat administration of isotope would not offer an assessment on tumor response and lead to potential additive toxicity to the thyroid gland.

Pathological and immunohistological studies provide a qualitative and semiquantitative look at the characteristics of the residual cell population. The pattern of tumor regrowth after 22 days is disappointing, but may be a true reflection of the limitations of this therapy in the MCF-7 NIS-Fluc-transfected xenografts. It is also possible that a single treatment is insufficient to induce complete tumor regression, but that with repeat dosing a cumulative effect and a sustained response would be achieved. Bioluminescent monitoring is shown here to be an accessible tool for studying tumor xenografts. These findings provide a preclinical guide on which to formulate treatment algorithms and design of clinical trials. Further studies are warranted to expand upon our results.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Meike Schipper and Mangala Dandekar for their assistance in some experiments. We are indebted to Caroline Tudor for her assistance in configuring the microphotographs. This study was supported by Grant 5 R01 CA082214-06 (SSG), ICMIC P50 (SSG), Small Animal Imaging Resource Program (SAIRP) R24 CA 92862, CA-Breast Cancer Research Program 7WB-0137 (IW).

Abbreviations

- NIS

Na+ I symporter, sodium iodide symporter

References

- 1.Schlumberger M, Tubiana M, De Vathaire F, Hill C, Gardet P, Travagli JP, Fragu P, Lumbroso J, Caillou B, Parmentier C. Long-term results of treatment of 283 patients with lung and bone metastases from differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;63:960–967. doi: 10.1210/jcem-63-4-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlumberger MJ. Papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:297–306. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801293380506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazzaferri E. Radioiodine and other treatment and out-comes. In: Braverman LE, Utiger RD, editors. Werner and Ingbar’s the thyroid: A fundamental and clinical text. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 2000. pp. 904–929. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai G, Levy O, Carrasco N. Cloning and characterization of the thyroid iodide transporter. Nature. 1996;379:458–460. doi: 10.1038/379458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tazebay UH, Wapnir IL, Levy O, Dohan O, Zuckier LS, Zhao QH, Deng HF, Amenta PS, Fineberg S, Pestell RG, Carrasco N. The mammary gland iodide transporter is expressed during lactation and in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2000;6:871–878. doi: 10.1038/78630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wapnir IL, van de Rijn M, Nowels K, Amenta PS, Walton K, Montgomery K, Greco RS, Dohan O, Carrasco N. Immunohistochemical profile of the sodium/iodide symporter in thyroid, breast, and other carcinomas using high density tissue microarrays and conventional sections. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1880–1888. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim YH, Lee DS, Kang JH, Lee YJ, Chung JK, Roh JK, Kim SU, Lee MC. Reversing the silencing of reporter sodium/iodide symporter transgene for stem cell tracking. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:305–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee KH, Kim HK, Paik JY, Matsui T, Choe YS, Choi Y, Kim BT. Accuracy of myocardial sodium/iodide symporter gene expression imaging with radioiodide: Evaluation with a dual-gene adenovirus vector. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:652–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.So MK, Kang JH, Chung JK, Lee YJ, Shin JH, Kim KI, Jeong JM, Lee DS, Lee MC. In vivo imaging of retinoic acid receptor activity using a sodium/iodide symporter and luciferase dual imaging reporter gene. Mol Imaging. 2004;3:163–171. doi: 10.1162/15353500200404130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin JH, Chung JK, Kang JH, Lee YJ, Kim KI, So Y, Jeong JM, Lee DS, Lee MC. Noninvasive imaging for monitoring of viable cancer cells using a dual-imaging reporter gene. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:2109–2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandell RB, Mandell LZ, Link CJ., Jr Radioisotope concentrator gene therapy using the sodium/iodide symporter gene. Cancer Res. 1999;59:661–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho JY, Xing S, Liu X, Buckwalter TL, Hwa L, Sferra TJ, Chiu IM, Jhiang SM. Expression and activity of human Na+/I symporter in human glioma cells by adenovirus-mediated gene delivery. Gene Ther. 2000;7:740–749. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho JY, Shen DH, Yang W, Williams B, Buckwalter TL, La Perle KM, Hinkle G, Pozderac R, Kloos R, Nagaraja HN, Barth RF, Jhiang SM. In vivo imaging and radioiodine therapy following sodium iodide symporter gene transfer in animal model of intracerebral gliomas. Gene Ther. 2002;9:1139–1145. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spitzweg C, Joba W, Eisenmenger W, Heufelder AE. Analysis of human sodium iodide symporter gene expression in extrathyroidal tissues and cloning of its complementary deoxyribonucleic acids from salivary gland, mammary gland, and gastric mucosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1746–1751. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.5.4839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moon DH, Lee SJ, Park KY, Park KK, Ahn SH, Pai MS, Chang H, Lee HK, Ahn IM. Correlation between 99mTc-pertechnetate uptakes and expressions of human sodium iodide symporter gene in breast tumor tissues. Nucl Med Biol. 2001;28:829–834. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(01)00243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wapnir IL, Goris M, Yudd A, Dohan O, Adelman D, Nowels K, Carrasco N. The Na+/I symporter mediates iodide uptake in breast cancer metastases and can be selectively down-regulated in the thyroid. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4294–4302. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gudkov AV, Komarova EA. The role of p53 in determining sensitivity to radiotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:117–129. doi: 10.1038/nrc992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia F, Powell SN. The molecular basis of radiosensitivity and chemosensitivity in the treatment of breast cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2002;12:296–304. doi: 10.1053/srao.2002.35250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stassen T, Port M, Nuyken I, Abend M. Radiation-induced gene expression in MCF-7 cells. Int J Radiat Biol. 2003;79:319–331. doi: 10.1080/0955300032000093146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Contag CH, Jenkins D, Contag PR, Negrin RS. Use of reporter genes for optical measurements of neoplastic disease in vivo. Neoplasia. 2000;2:41–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edinger M, Cao YA, Hornig YS, Jenkins DE, Verneris MR, Bachmann MH, Negrin RS, Contag CH. Advancing animal models of neoplasia through in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:2128–2136. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00410-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Wet JR, Wood KV, Helinski DR, DeLuca M. Cloning of firefly luciferase cDNA and the expression of active luciferase in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:7870–7873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.7870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu Y, Dang H, Middleton B, Zhang Z, Washburn L, Campbell-Thompson M, Atkinson MA, Gambhir SS, Tian J, Kaufman DL. Bioluminescent monitoring of islet graft survival after transplantation. Mol Ther. 2004;9:428–435. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Hellstrom KE, Chen L. Luciferase activity as a marker of tumor burden and as an indicator of tumor response to antineoplastic therapy in vivo. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1994;12:87–92. doi: 10.1007/BF01753974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De A, Lewis XZ, Gambhir SS. Noninvasive imaging of lentiviral-mediated reporter gene expression in living mice. Mol Ther. 2003;7:681–691. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00070-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wapnir IL, Wartenberg DE, Greco RS. Three-dimensional staging of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;41:15–19. doi: 10.1007/BF01807032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schlumberger M, Challeton C, De Vathaire F, Parmentier C. Treatment of distant metastases of differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J Endocrinol Invest. 1995;18:170–172. doi: 10.1007/BF03349735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pacini F, Schlumberger M, Harmer C, Berg GG, Cohen O, Duntas L, Jamar F, Jarzab B, Limbert E, Lind P, Reiners C, Franco FS, Smit J, Wiersinga W. Post-surgical use of radioiodine (131I) in patients with papillary and follicular thyroid cancer and the issue of remnant ablation: A consensus report. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;153:651–659. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spitzweg C, O’Connor MK, Bergert ER, Tindall DJ, Young CY, Morris JC. Treatment of prostate cancer by radioiodine therapy after tissue-specific expression of the sodium iodide symporter. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6526–6530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boland A, Ricard M, Opolon P, Bidart JM, Yeh P, Filetti S, Schlumberger M, Perricaudet M. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of the thyroid sodium/iodide symporter gene into tumors for a targeted radiotherapy. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3484–3492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spitzweg C, Dietz AB, O’Connor MK, Bergert ER, Tindall DJ, Young CY, Morris JC. In vivo sodium iodide symporter gene therapy of prostate cancer. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1524–1531. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scholz IV, Cengic N, Baker CH, Harrington KJ, Maletz K, Bergert ER, Vile R, Goke B, Morris JC, Spitzweg C. Radioiodine therapy of colon cancer following tissue-specific sodium iodide symporter gene transfer. Gene Ther. 2005;12:272–280. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]