Abstract

Background

Primary prevention programmes in many countries attempt to reduce mortality and morbidity due to coronary heart disease (CHD) through risk factor modification. It is widely believed that multiple risk factor intervention using counselling and educational methods is efficacious and cost-effective and should be expanded. Recent trials examining risk factor changes have cast considerable doubt on the effectiveness of these multiple risk factor interventions.

Objectives

To assess the effects of multiple risk factor intervention for reducing cardiovascular risk factors, total mortality, and mortality from CHD among adults without clinical evidence of established cardiovascular disease.

Search strategy

MEDLINE was searched for the original review to 1995. This was updated by searching the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials on The Cochrane Library Issue 3 2001, MEDLINE(2000 to September 2001) and EMBASE (1998 to September 2001).

Selection criteria

Intervention studies using counselling or education to modify more than one cardiovascular risk factor in adults from general populations, occupational groups, or high risk groups. Trials of less than 6 months duration were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

Data were extracted by two reviewers independently. Investigators were contacted to obtain missing information.

Main results

A total of 39 trials were found of which ten reported clinical event data. In the ten trials with clinical event end-points, the pooled odds ratios for total and CHD mortality were 0.96 (95% confidence intervals (CI) 0.92 to 1.01) and 0.96 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.04) respectively. Net changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and blood cholesterol were (weighted mean differences) −3.6 mmHg (95% CI −3.9 to −3.3 mmHg), −2.8 mmHg (95% CI −2.9 to −2.6 mmHg) and −0.07 mMol/l (95% CI −0.8 to −0.06 mMol/l) respectively. Odds of reduction in smoking prevalence was 20% (95% CI 8% to 31%). Statistical heterogeneity between the studies with respect to mortality and risk factor changes was due to trials focusing on hypertensive participants and those using considerable amounts of drug treatment.

Authors’ conclusions

The pooled effects suggest multiple risk factor intervention has no effect on mortality. However, a small, but potentially important, benefit of treatment (about a 10% reduction in CHD mortality) may have been missed. Risk factor changes were relatively modest, were related to the amount of pharmacological treatment used, and in some cases may have been over-estimated because of regression to the mean effects, lack of intention to treat analyses, habituation to blood pressure measurement, and use of self-reports of smoking. Interventions using personal or family counselling and education with or without pharmacological treatments appear to be more effective at achieving risk factor reduction and consequent reductions in mortality in high risk hypertensive populations. The evidence suggests that such interventions have limited utility in the general population.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Coronary Disease [mortality; *prevention & control], Patient Education as Topic, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Risk Factors

MeSH check words: Humans

BACKGROUND

In apparently healthy and asymptomatic people, the incidence of cardiovascular disease is in part explained by the modifiable risk factors: serum total cholesterol and reduced high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, blood pressure, cigarette smoking and diabetes. Primary prevention programmes attempt to reduce coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality and morbidity through risk factor modification. While the identification of high risk individuals and treatment according to level of cardiac risk may be effective at an individual level, population strategies may be more effective in reducing the burden of cardiovascular disease (Emberson 2004). Recent findings suggest that increasingly effective drug treatments for high risk individuals and widespread implementation of population wide strategies of tobacco control and dietary changes is increasing the advantage of high risk approaches to prevention. (Jackson 2006)

In the UK, the National Service Framework for coronary heart disease promotes multiple risk factor counselling and health education (NSF-CHD 2000). In the USA, the AHA Guidelines for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: 2002 update identify areas for intervention based on the non-pharmacological treatment of established risk factors (AHA 2002). Similarly, the Third Joint Task Force of the European and other Societies recommend use of behavioural counselling for stopping smoking tobacco, making healthy food choices and increasing physical activity (ESC 2003).

Primary prevention programmes in many countries attempt to reduce mortality and morbidity due to coronary heart disease through risk factor modification (Canadian 1986; Kickbush 1988). Randomized controlled trials of the efficacy of multiple risk factor intervention using counselling and education in addition to, or instead of, pharmacological treatments to modify major cardiovascular risk factors have been carried out in primary care and in the work place. The findings of these trials have been equivocal; efficacy in reducing disease incidence appears to be associated with the degree of risk factor control achieved (Editorial I 1982; Editorial II 1982). Taken with evidence from quasi-experimental studies, such as the North Karelia project (Puska 1976; Puska 1981) and the Stanford Heart Disease Prevention Programme (Farquhar 1977; Farquhar 1990; Fortmann 1993), it was widely believed that multiple risk factor intervention using counselling and educational methods was efficacious and cost-effective and should be expanded.

Along side this research health services have acted by developing health promotion as a specialty (Editorial 1984), organising the routine collection of data on cardiovascular risk factors in British primary care, and issuing primary prevention policy, for example the Health of the Nation strategy in England (DoH 1992). More recent trials examining risk factor changes have cast considerable doubt on the effectiveness of these multiple risk factor interventions (Stott 1994a; Stott 1994b) and even interventions specifically against smoking (COMMIT I 1995; COMMIT II 1995) prompting a review of the reasons for the frequent failure of such community experiments (Susser 1995). A new generation of population based interventions such as the Minnesota Heart Health Program (Luepker 1994), Heartbeat Wales (Tudor-Smith 1998), the Malmö preventive project (Berglund 2000) have cast further doubt on the value of such interventions.

Treatment of multiple risk factors by diet modification, promotion of physical activity, weight loss and smoking cessation has been evaluated in a number of randomised trials. Two previous reviews (McCormick 1988; Schoenberger 1990) of multiple risk factor intervention using counselling and education with or without pharmacological treatments were conducted prior to the publication of more recent trials, were not systematic in their coverage, and did not formally aggregate the findings through meta-analysis.

In a systematic review, fourteen randomised trials were identified up until April 1995. Meta-analyses suggested that although interventions achieved reductions in risk factors, these were small and were not translated into significant decreases in morbidity or mortality (Ebrahim 1997). Since this systematic review was published a number of trials of multiple risk factor interventions have been reported and update of the review is needed.

OBJECTIVES

To assess the effectiveness of multiple risk factor intervention using counselling and/or educational approaches with or without pharmacological interventions in:

-

a)

reducing systolic and diastolic blood pressure;

-

b)

reducing blood cholesterol levels;

-

c)

reducing smoking rates;

-

d)

reducing total mortality;

-

e)

reducing CHD mortality;

among middle-aged (40+) adults.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials of at least 6 months duration with parallel group design. Trials may be randomized by individual or by group (e.g. family, workplace site).

Types of participants

Adults aged at least 40 years old.

General populations, workforce populations and high risk groups.

Participants without clinical evidence of cardiovascular diseases.

Types of interventions

Counselling or educational interventions, with or without pharmacological treatments, which aim to reduce more than one cardiovascular risk factor (i.e. blood pressure, smoking, total blood cholesterol, physical activity, diet).

Types of outcome measures

Total mortality, CHD mortality, net change in blood pressure, smoking and total blood cholesterol.

Search methods for identification of studies

MEDLINE was searched from 1966 to April 1995 using an RCT filter (Dickersin 1994) together with relevant diagnostic terms (i.e. coronary heart disease and stroke) and text word searches for specific interventions (e.g. dietary change, smoking cessation, exercise, blood pressure control, prevention, cholesterol lowering). Searches of reference lists of papers, expert advice and use of citation searches. This was updated by searching the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) on the Cochrane Library Issue 3 2001, MEDLINE (2000 to September 2001) and EMBASE (1998 to September 2001),using an RCT filter for MEDLINE (Dickersin 1994) and EMBASE (Lefebvre 1996). See additional tables for details of search strategies (Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4).

Strategy used for searching The Cochrane LIbrary:

-

#1

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

-

#2

CORONARY DISEASE

-

#3

cardiovascular

-

#4

(coronary near disease*)

-

#5

(heart near disease*)

-

#6

HYPERTENSION

-

#7

hypertension

-

#8

(atherosclerosis or arteriosclerosis)

-

#9

(hyperlipidaemia or hyperlipidemia)

-

#10

ARTERIOSCLEROSIS

-

#11

CHOLESTEROL

-

#12

HYPERLIPIDEMIA

-

#13

cholesterol

-

#14

(multiple next risk next factor*)

-

#15

(coronary next risk next factor*)

-

#16

(#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10)

-

#17

(#11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15)

-

#18

(#16 or #17)

-

#19

HEALTH EDUCATION

-

#20

HEALTH PROMOTION

-

#21

HEALTH BEHAVIOR

-

#22

PRIMARY PREVENTION

-

#23

COUNSELING

-

#24

counsel*

-

#25

(health near educat*)

-

#26

(patient near educat*)

-

#27

(education* near program*)

-

#28

(health near promotion*)

-

#29

(health near behaviour*)

-

#30

(health near behavior*)

-

#31

(primary next prevention)

-

#32

((multiple next risk) near intervention*)

-

#33

(multifactor* near intervention*)

-

#34

(multifactor* near prevention)

-

#35

((risk next factor*) near reduc*)

-

#36

((risk next factor*) near manag*)

-

#37

((risk next factor*) near intervent*)

-

#38

(lifestyle near intervention*)

-

#39

(lifestyle near advice)

-

#40

(life-style near intervention*)

-

#41

(life-style near advice)

-

#42

(life-style near alter*)

-

#43

(lifestyle near alter*)

-

#44

(lifestyle near educat*)

-

#45

(life-style near educat*)

-

#46

(life-style near chang*)

-

#47

(lifestyle near chang*)

-

#48

(behavior* near chang*)

-

#49

(behaviour* near chang*)

-

#50

((health next care) near advice)

-

#51

(healthcare near advice)

-

#52

nonpharmacologic*

-

#53

non-pharmacologic*

-

#54

(#19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 or # 27 or #28 or #29)

-

#55

(#30 or #31 or #32 or #33 or #34 or #35 or #36 or #37 or # 38 or #39)

-

#56

(#40 or #41 or #42 or #43 or #44 or #45 or #46 or #47 or # 48 or #49 or #50 or #51 or #52 or #53)

-

#57

((#54 or #55 or #56)

-

#58

(#18 and #57)

Data collection and analysis

For the original search titles and abstracts obtained through searches were checked by two reviewers. Each paper thought to be of possible relevance was obtained and read by each reviewer independently to determine whether it fitted specified inclusion criteria. Disagreements were discussed and resolved between the two reviewers. The results of the updated search were checked by one reviewer to eliminate those studies that were definitely not relevant to the review. Remaining records were checked by two reviewers independently. All papers that were thought to be of relevance were obtained and read by two reviewers independently. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or by consultation with a third reviewer. The main aspect of quality that was formally assessed was the adequacy of concealment of randomisation as other aspects (e.g. blinding) are of less relevance in non-pharmacological interventions. In addition, comparability of baseline characteristics and completeness of follow up were assessed.

Independent data abstraction was performed and chief investigators were contacted to provide additional relevant information where necessary.

For continuous variables, net changes were compared (i.e. control group minus intervention group differences) at the longest duration of follow up available and the standardised mean difference were examined using random and fixed effects model. Categorical variables (mortality rates) were expressed as odds ratios and fixed effect models used except where there was significant heterogeneity of effects.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Details of the studies included in the review are shown in the table of characteristics of included studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

The quality of the trials examined deserves comment. Very few of the published reports provided sufficient detail to replicate the intervention used, and in several trials the intervention varied between sites and over time. It is likely that the quality of the intervention, in terms of intensity and frequency, person carrying out activities, and the theoretical framework of behavioural change used will determine the impact of intervention. Losses to follow up were a particular problem as changes in risk factors cannot be assessed in an intention to treat analysis. Validation of smoking outcomes using biochemical assay of cotinine was only used in one trial.

Random allocation methods were not usually reported in the smaller trials and specific enquiries were not made of investigators. In the large trials, it is unlikely that the allocation method was suspect. Blinding of intervention allocation is not possible in lifestyle interventions and this inevitably raises the possibility of bias. Outcomes were usually assessed with knowledge of treatment allocation and this too makes biased assessment of some outcomes possible. It seems unlikely that lack of blinding had any effect on clinical event outcomes, but it is possible that participants randomised to a control or usual care group might have been more likely to take health preventive activity as they may have felt they were missing potential benefits. Lack of blinding in assessment of smoking histories may have resulted in a reporting bias with those allocated to interventions more likely to say they had stopped smoking. Validation of self-reported smoking outcomes using biochemical assay of serum thiocyanate was reported in three trials.

Effects of interventions

Details of the studies included in the review are shown in Table 1. A total of 39 trials of multiple risk factor intervention were found comprising 44 distinct study groups. This is more than double the 18 trials identified for the original review. Ten trials reported total or coronary heart disease mortality as outcomes but none of these were additional to those in the original review. One trial from the original review, the Swedish RIS study, reported extended mortality follow up. Only four trials were sufficiently large to have adequate power to show meaningful changes in total or coronary heart disease mortality. More recent trials focussed on the outcomes: blood pressure, serum cholesterol, physical activity, diet, control of diabetes and weight loss. In the original review eleven studies reported smoking habit as an outcome. Among the newly identified trials only a further three reported an outcome relating to smoking cessation.

In more recent trials the quality of reporting was noticeably improved. It was noted in the original review that few early trials provided sufficient detail to replicate the intervention used and that several studies reported interventions that varied between sites and over time.

In general, the trials compared an intervention comprising some form of counselling and education with control groups, which either received nothing or usual care. The type of behavioural intervention used was seldom reported. In the few studies reporting the type of intervention a Stages of Change model (Diclemente 1991; Prochaska 1983) and a person centred and self directed psychological approach (Meichenbaum 1993) were described. In trials included in the review, education and counselling targeted combinations of diet, exercise, weight loss, smoking cessation, diabetes management and use of medication.

With the exception of one study comprising men and women aged 60-85 years (Applegate 1992), the oldest subjects included in the trials were 75 years of age. The majority of trials randomised only middle-aged adults and some included younger adults. One trial was not included in analyses (Connell 1995) as losses to follow up were extremely high.

Sixty seven trials identified as involving multiple risk factor interventions were excluded from consideration for the following reasons: no risk factor changes measured and/or reported (n=9), non-random or inadequate allocation to intervention and control groups (n=21), no specific multiple risk factor intervention (n=3), control group received substantial intervention (n=17), follow up to 6 months was not reported (n=6), the mean age of participants was less than 40 (n=5), a substantial proportion of participants had heart disease (n=3), numbers in groups were not reported (n= 1), or baseline or follow up data were not provided (n=2). A large number of studies were set up in what was then the Soviet Union but it appears that allocation to intervention and control groups was not random although attempts to trace the investigators have been unsuccessful.

The trials with clinical end-points comprise approximately 903,000 patient years of observation and those with risk factor end-points had 303,000 patient-years of observation. The oldest subjects included in any of the trials were less than 74 years of age, with the majority of trials randomising only middle-aged adults.

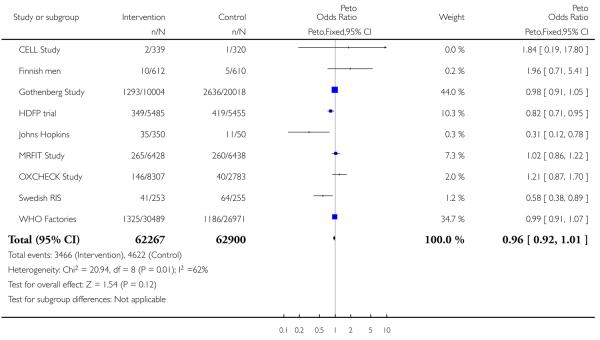

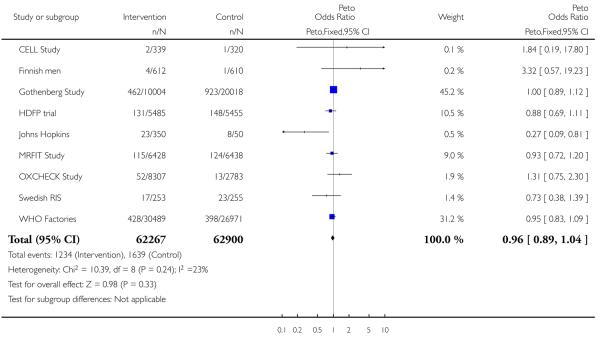

Total mortality and coronary heart disease mortality

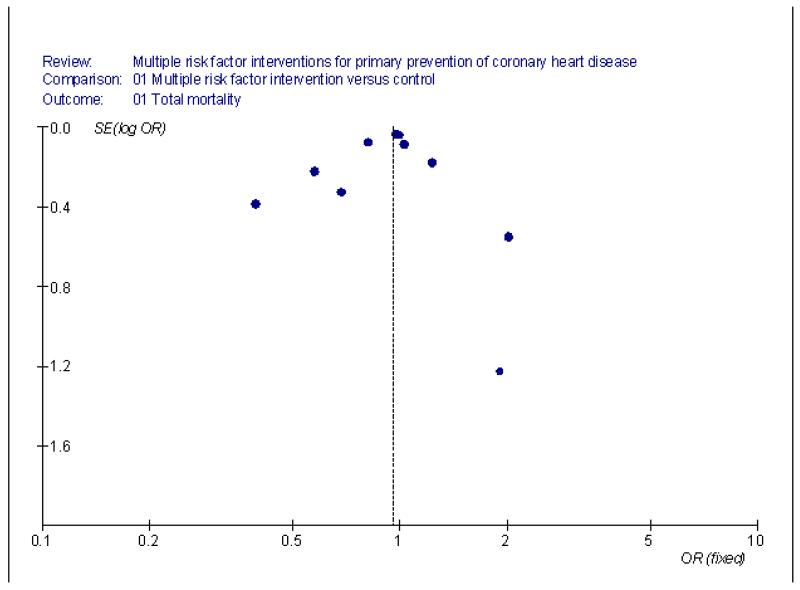

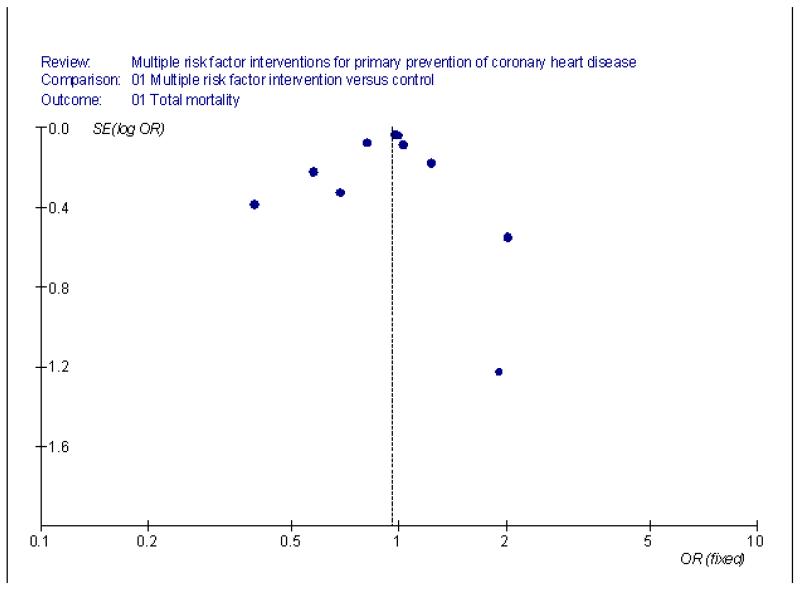

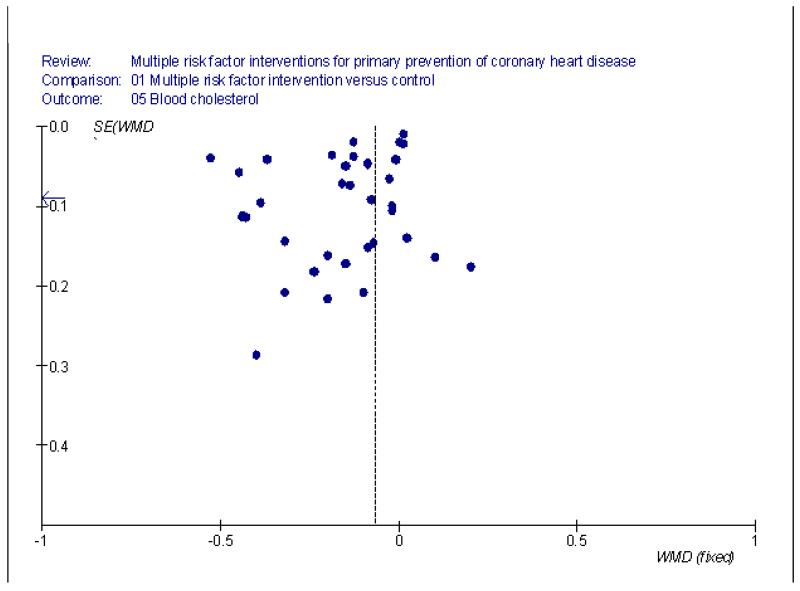

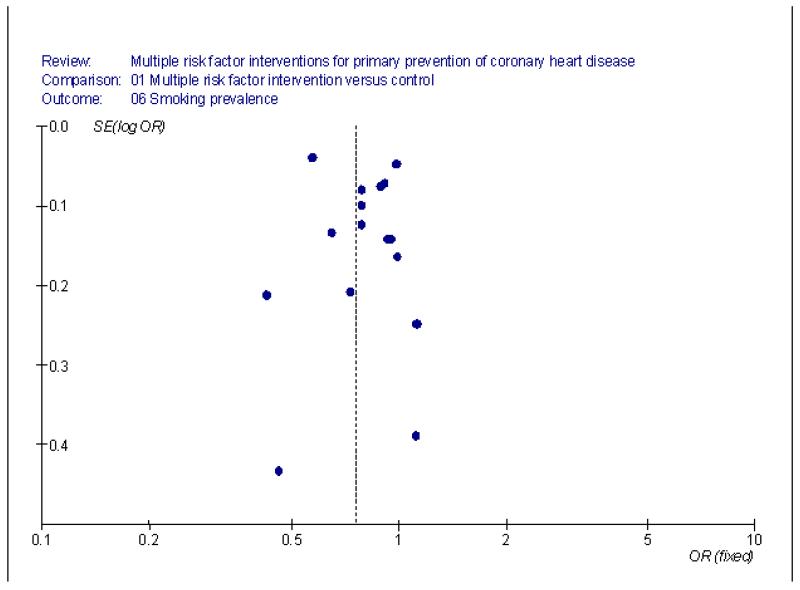

Ten trials reported total and coronary heart disease mortality outcomes. For total mortality there was a pooled odds ratio of 0.96 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.01) favouring intervention. With regard to coronary heart disease mortality the odds ratio favouring intervention was 0.96 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.04). Funnel plots suggested little evidence of small study bias in trials with these outcomes (Figure 1; Figure 2). Only the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program, Johns Hopkins Hypertension Trial and Swedish RIS reported significant effects on total mortality (HDFP trial, Johns Hopkins, Swedish RIS). The Johns Hopkins Hypertension Trial also showed a significant benefit for coronary heart disease mortality.

Figure 1.

Total mortality funnel plot

Figure 2.

Coronary heart disease mortality funnel plot

Evidence of statistical heterogeneity was apparent in the pooled odds ratios for total mortality but not for coronary heart disease mortality when all studies were included. Removal of the trials including hypertensives (HDFP trial; Johns Hopkins) reduced the heterogeneity for total mortality. Including a term for interaction between treatment effect and baseline level of coronary heart disease risk calculated using either control group coronary heart disease risk or combined control and intervention group risk reduced heterogeneity between the trials to insignificant levels for total and coronary heart disease mortality.

Modelling the effects of age using the mean age of study participants and proportion of patients on antihypertensive treatment and cholesterol lowering drug treatment did not reveal any significant interactions between age, drug treatments and outcome. The significant interaction between intervention and level of coronary heart disease risk indicated that trials recruiting higher risk participants were more likely to demonstrate beneficial effects. This effect is explained by the inclusion of the two trials which studied hypertensive patients rather than general population or workforce subjects. It is impossible to separate this effect of baseline coronary heart disease risk from the benefits of pharmacological treatment of hypertension.

Non-fatal myocardial infarctions were reported in the WHO Factory Study, the Gothenberg Study and in the Oslo Study (WHO Factories; Gothenberg Study; The Oslo Study). The pooled odds ratio for non-fatal myocardial infarction in these three trials was 1.01 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.10).

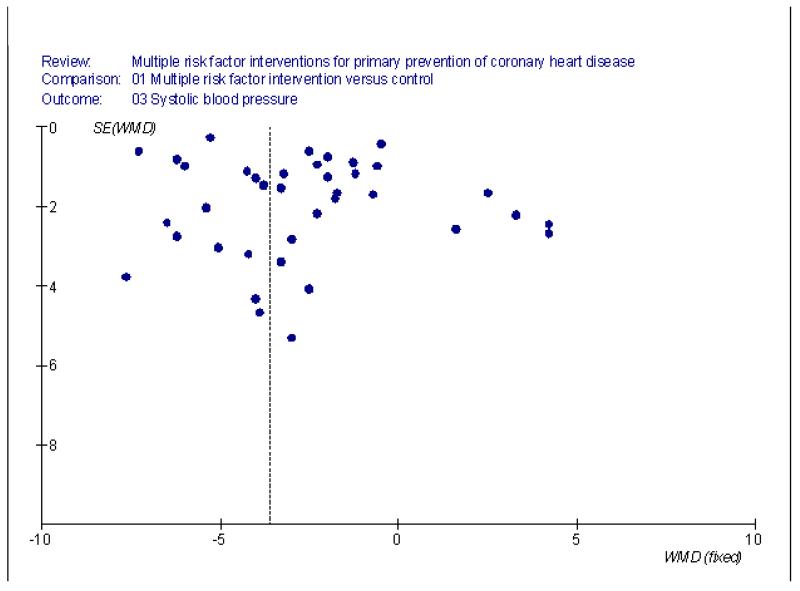

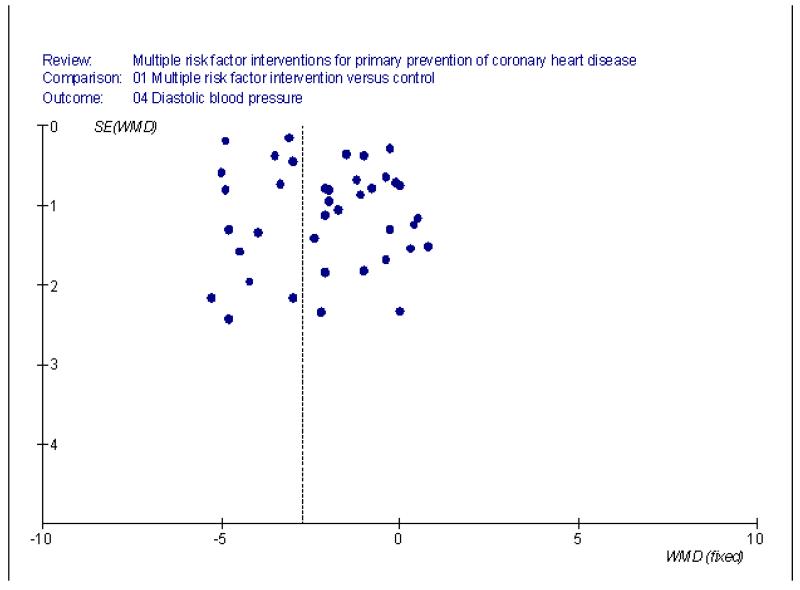

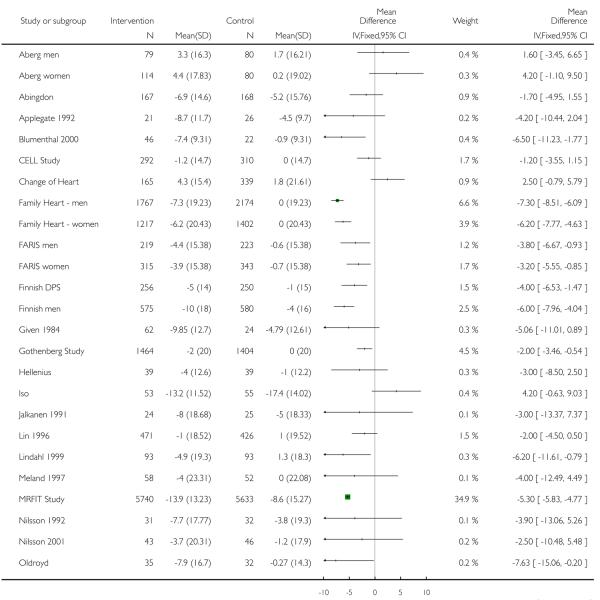

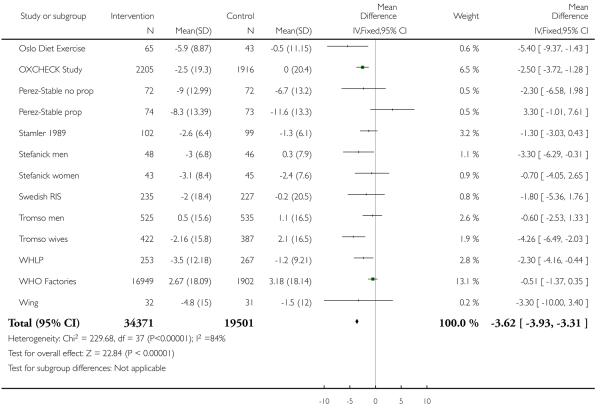

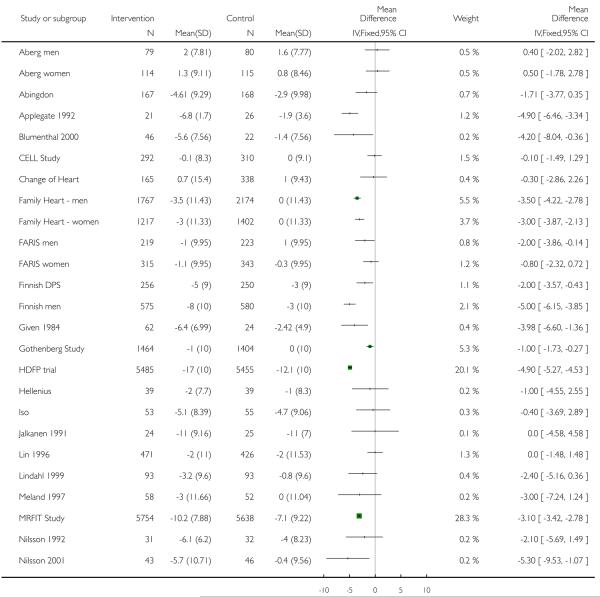

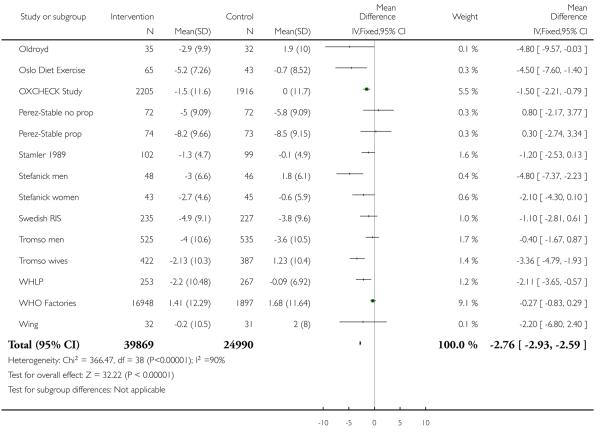

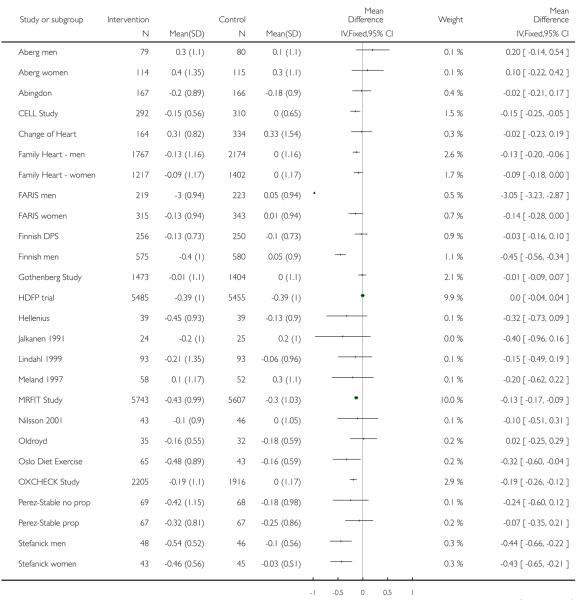

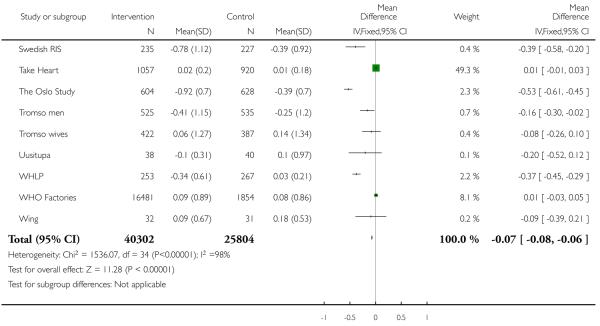

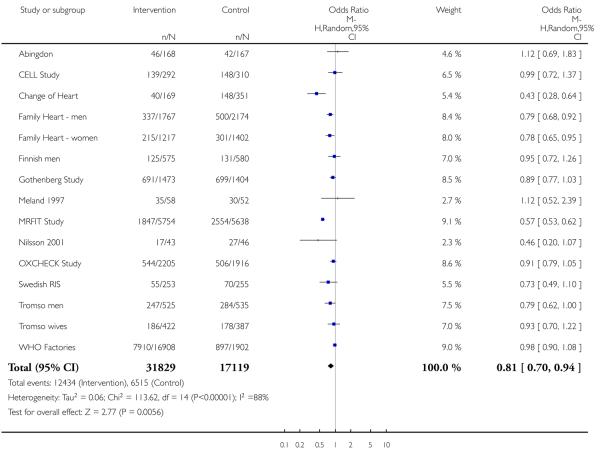

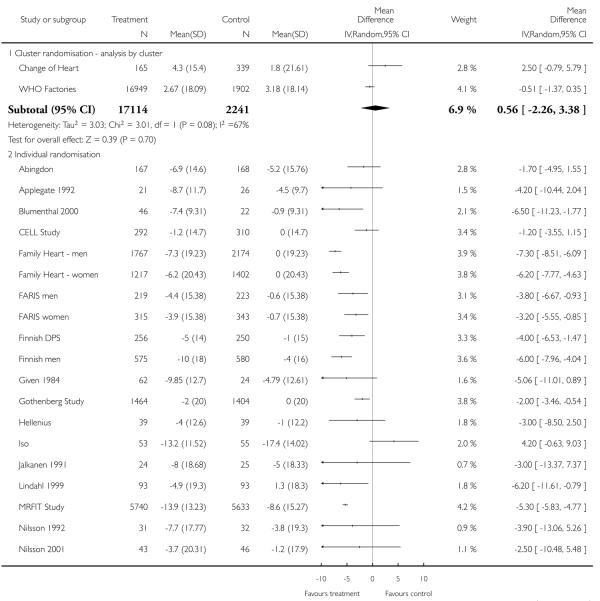

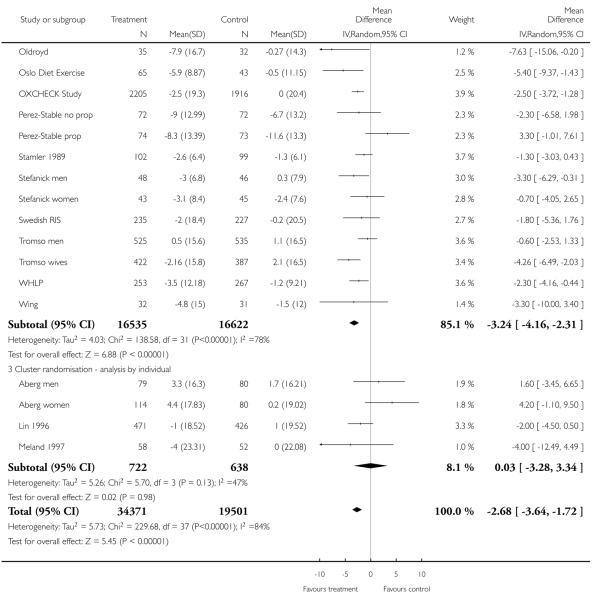

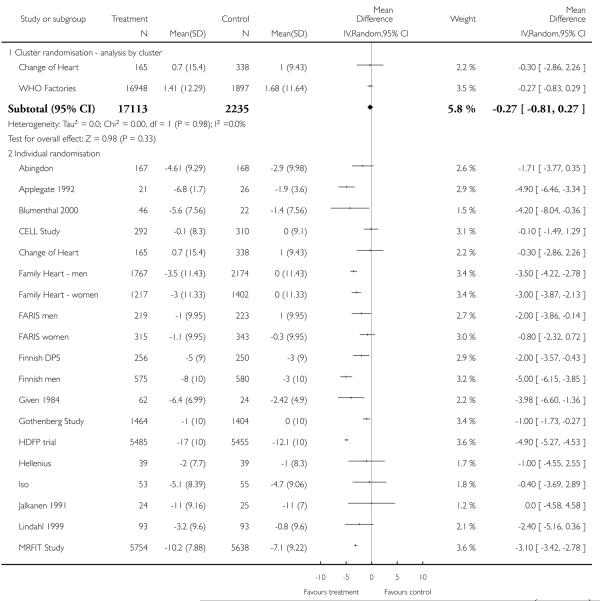

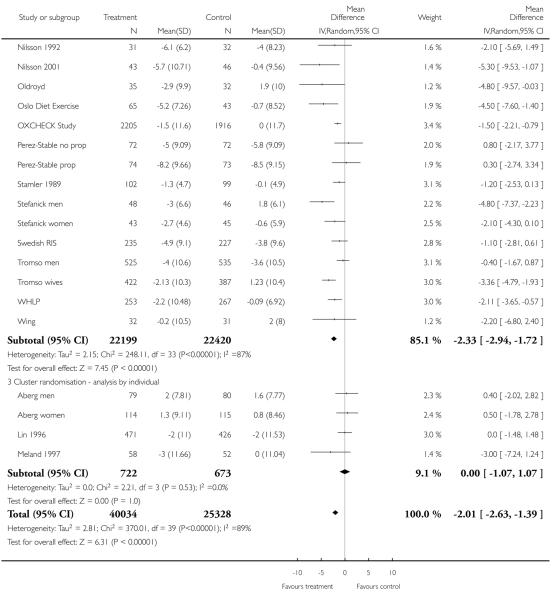

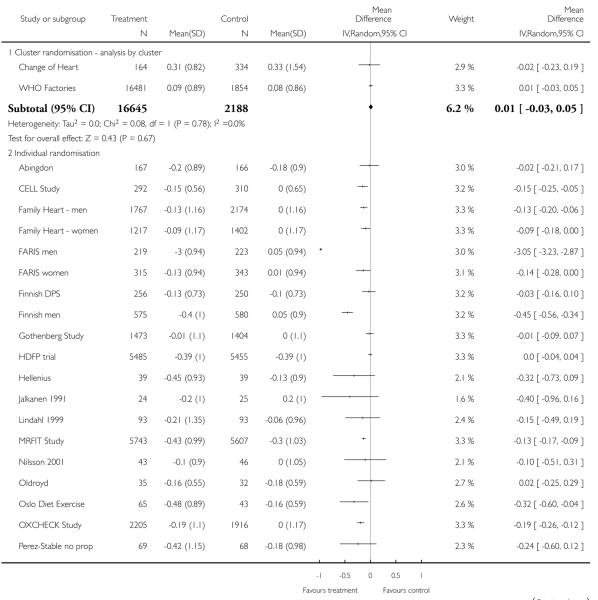

Changes in risk factors

In all but five of the trials reporting systolic blood pressure as an outcome there was a tendency for reduced systolic blood pressure in intervention groups. Changes in blood pressure were small and slightly less in the updated compared with the original review. In 38 interventions reporting systolic blood pressure change, the weighted mean difference between intervention and control was −3.6 mm Hg (95% CI −3.9 to −3.3) in fixed effect analysis. For diastolic blood pressure the weighted mean difference was −2.8 mm Hg (95% CI −2.9 to −2.6). For both outcomes there was no evidence of small study bias in the trials as shown by the funnel plots (Figure 3; Figure 4; Figure 5; Figure 6).

Figure 3.

Systolic blood presure funnel plot

Figure 4.

Diastolic blood presure funnel plot

Figure 5.

Cholesterol funnel plot

Figure 6.

Smoking funnel plot

The Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial, the Hypertension Detection and Follow Up Program, the WHO factories study, the Gothenburg study and the Finnish Businessmen study used antihypertensive drug therapy if indicated (Finnish men; Gothenberg Study; HDFP trial; MRFIT Study; WHO Factories). Exclusion of those trials in which a high proportion of participants were on pharmacological treatment (CELL Study; Gothenberg Study; Finnish men; HDFP trial; MRFIT Study; Perez-Stable prop) resulted in smaller, but still statistically significant, net reductions in blood pressure: systolic −2.7 mmHg (CI −3.9 to −3.3), diastolic −1.7 mmHg (CI −2.0 to −1.5).

Not all trials reported, or were able to provide data on, blood pressure at follow up. Investigators from the Oslo study stated that there were no changes observed (Hjerman I. personal communication, 1996).

Blood cholesterol

Blood cholesterol levels showed a small but highly significant fall (net difference −0.07 mmol/L, 95% CI −0.08 to −0.06 mmol/L). This was half the fall seen in the earlier review and may reflect more widespread use of cholesterol lowering medication in recent years. Substantial heterogeneity was apparent in this meta-analysis. The Hypertension Detection & Follow-up Program reported no reduction in blood cholesterol levels but published quantitative data are not available (HDFP trial). The Finnish Businessmen Trial made substantial use of cholesterol lowering drugs (mainly probucol and clofibrate) which probably explains the larger reduction in blood cholesterol observed in this trial (Finnish men). In the FARIS trial there was a mean reduction in cholesterol of 3.0 mmol/L in men randomised to multifactorial intervention (FARIS men; FARIS women). This is probably a consequence of statin prescription being recommended after 3 months of intervention if cholesterol control was not adequate by lifestyle modification. Exclusion of these trials did not make a difference to the pooled fall observed.

Smoking

Smoking prevalence showed an overall net reduction of 24%. Substantial heterogeneity was apparent and an odds reduction of 20% was observed in a random effects model. In the Hypertension Detection & Follow up Program quantitative data were not available but no changes in smoking rates were found (HDFP trial). Smoking rates fell particularly sharply in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial and in the Oslo Study which both used individual smoking advice given by a physician (MRFIT Study; The Oslo Study) and in the Change of Heart study where large baseline differences between groups were noted and losses to follow up were high (Change of Heart study). Validation of self-reported smoking rate reductions in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial by comparison with serum thiocyanate levels suggested that the improvement might be overestimated (MRFIT Study).

Heterogeneity of effects

Blood pressure, smoking, and blood cholesterol outcomes were subject to substantial heterogeneity. Random effects analyses were also conducted which showed similar pooled net effects but as the variation between trials is taken into account (which is large), confidence intervals were wider. The heterogeneity between trials is probably explained by differences in the use of both antihypertensive and cholesterol-lowering drugs, and the populations studied. Risk factor net changes were strongly correlated with the initial level of diastolic blood pressure, smoking and blood cholesterol but not systolic blood pressure. The sample size weighted correlation coefficients between initial level and magnitude of risk factor reduction for diastolic blood pressure, smoking and blood cholesterol were 0.73, p=0.006, 0.63, p=0.01 and 0.74, p=0.004 respectively. Those studies with the highest baseline diastolic blood pressure, smoking prevalence and blood cholesterol levels demonstrated larger intervention associated falls in these risk factors.

Cluster-randomisation

In meta-analysis the weighting given to trials with a cluster design may be over-estimated. In trials with cluster design analysed by individual or by cluster there was no evidence of overall benefit with regard to lowering of blood pressure or cholesterol. Benefits tended to be in trials with randomisation by individual.

DISCUSSION

Findings

As reported in the earlier review, multiple risk factor interventions comprising counselling, education and drug therapies were ineffective in achieving reductions in total or cardiovascular disease mortality when used in general or workforce populations of middle-aged adults. The pooled effects of intervention were statistically insignificant but a potentially useful benefit of treatment (about a 10% reduction in coronary heart disease mortality) may have been missed.

The risk factor changes associated with interventions were modest, but are probably optimistic estimates as changes could only be measured in those remaining in the trials. Habituation to blood pressure measurement, regression to the mean, and self-reports of smoking will also tend to exaggerate the changes observed. It is, however, not possible to separate participants’ level of risk from the use of anti-hypertensives in the present set of trials, as studies with high-risk participants tended to be the ones which included participants with high levels of anti-hypertensive drug use. Furthermore, there are many problems in relating trial outcome to a risk measure which is itself dependent on the outcome in meta-analysis (Egger 1995). Therefore our conclusions on these issues can only be tentative.

Heterogeneity of intervention effects is apparent. This is probably caused by two factors: the participants included in the trials, and the use of pharmacological treatments. Hypertensives, at highest risk, were more likely to benefit from counselling and education, and effective drugs. These findings suggest that targeting of current health promotion activities to high risk individuals might be of more value than more general health promotion for everyone.

The interventions used

The benefits of drug treatments for lowering blood pressure and cholesterol are clear (Collins 1994; Davey Smith 1993; CTT 2005). However, those people at highest risk of disease in both hypertension control (Mulrow 1995) and cholesterol lowering (Davey Smith 1993) benefit most. Treatment of low risk populations may result in small treatment benefits being outweighed by small treatment risks (Davey Smith 1994) which may have occurred in both the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial and the Finnish businessmen’s trial (Finnish men; MRFIT Study). There were strong associations between baseline levels of risk factors and net falls experienced, suggesting that intervention may be more effective in populations with particularly adverse risk factor profiles.

More intensive interventions might be expected to produce better effects although those used in many of the trials would far exceed what is feasible in routine practice. A meta-analysis of dietary modifications found that increasing intensity of dietary intervention was associated with greater falls in blood cholesterol levels in high risk participants (Brunner 1997). In the Minnesota Heart Health Programme, a non-randomised community trial of intensive health promotion, both risk-factor and mortality changes showed virtually no difference between intervention and control communities (Luepker 1996). The continued enthusiasm for health promotion practices given the failure of these community intervention trials is curious, especially given the huge resources which have been put into them.

Latency of effects

It is possible that benefits cannot be detected in the early stages but emerge over time. Longer term follow up of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial participants has demonstrated increased divergence between control and intervention group mortality rates (MRFITRG 1990) which has also been found in the Tromso Family Trial (Professor S. Knutson, personal communication). However, evidence from pharmacological trials suggests benefits from reduction of blood pressure and blood cholesterol are observed within two to four years (Collins 1994; Scandanavian 1994). The effects of giving up smoking vary depending on the clinical outcome considered: stroke risk falls rapidly after stopping (Wannamethee 1995), but coronary heart disease risk may be less reversible (Ben-Shlomo 1994; Cook 1986).

Evidence of benefit

The quasi-experimental North Karelia study has been very influential in supporting multiple risk factor intervention. Examination of the trends in both risk factors (Puska 1985; Vartiainen 1994) and coronary heart disease mortality (Valkonen 1992) observed in North Karelia and comparison regions show similar patterns occurring at the same time, suggesting that the interventions in North Karelia were not instrumental in causing the improvements observed (Ebrahim 2001). Indeed, the North Karelia and similar projects may be viewed as effects, or epiphenomena, of the very high coronary heart disease mortality rates experienced in many countries in the 1960s.

In secondary prevention following myocardial infarction and angina, trials of multiple and single risk factor interventions have suggested substantial benefits (Mullen 1992; Oldridge 1988; O’Connor 1989). It is probable that intervention aimed at lifestyle modification following myocardial infarction is effective because participants are much more likely to change their behaviours.

Limitations of randomised controlled trials

The interventions reviewed were essentially individual or family approaches. Randomised controlled trials impose limitations on the nature of interventions that may be tested and are of more value in examining high risk rather than population and social approaches to prevention (Rose 1992).

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

The use of “health promotion” techniques of one-to-one or family orientated information and advice on a range of life-styles (exercise, smoking cessation, diet) given to people at relatively low risk of cardiovascular disease is not particularly effective in terms of reducing the risk of clinical events. The costs of such interventions are high and it seems likely that these resources and techniques may be better used in people at high risk of cardiovascular disease where evidence of effectiveness is much stronger.

Policy implications

Health protection through national fiscal and legislative changes that aim to reduce smoking, dietary consumption of fats, “hidden” salt and calories, and increase facilities and opportunities for exercise should have a higher priority than health promotion interventions applied to general and workforce populations. It is essential that the current concepts and practices of multiple risk factor intervention, primarily through individual risk factor counselling, are not exported to poorer countries as the best policy option for dealing with existing and projected burdens of cardiovascular disease, as is currently happening (Pearson 1993). Health protection should be promoted as the mainstay of chronic disease prevention in poorer countries (Ebrahim 2001).

Implications for research

It is unlikely that any further large-scale multiple risk factor intervention trials will be mounted in high income countries in the future. It is also unlikely that uncontrolled or quasi-experimental study designs will produce more robust answers to questions of the effectiveness of multiple risk factor intervention by means of individual or family health information and advice.

Research on the effects and costs of health protection (i.e. fiscal and legislative approaches) and primary prevention would be of direct policy relevance, particularly in low and middle income countries.

Qualitative studies examining how participants perceived and responded to the advice and treatment given in these randomised controlled trials could be very helpful in shaping future interventions.

Our methods of attempting behaviour change in the general population are very limited. Different approaches to behaviour change are needed and should be tested empirically before being widely promoted. For example, the availability of foods and better access to recreational and sporting facilities may have a greater impact on dietary and exercise patterns respectively, than health professional advice. The effects of new approaches need to be examined in a wide range of people as it seems likely that the poor, socially excluded, specific ethnic groups and older people may all react in different ways.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease

In many countries, there is enthusiasm for “Healthy Heart Programmes” that use counseling and educational methods to encourage people to reduce their risks for developing heart disease. These risk factors include high cholesterol, excessive salt intake, high blood pressure, excess weight, a high-fat diet, smoking, diabetes, and a sedentary lifestyle. This updated review of all relevant studies found that the approach of trying to reduce more than one risk factor - multiple risk factor intervention - advocated by these Programmes do result in small reductions in blood pressure, cholesterol, salt intake, weight loss, etc. Contrary to expectations, these lifestyle changes had little or no impact on the risk of heart attack or death. Possible explanations for this are that the small risk factor changes are not maintained long-term or are not real but caused by some of the studies being poorly conducted. This review is based on the findings from 39 trials conducted in several countries over the course of three decades. Its authors discourage more research on the topic: “Our methods of attempting behaviour change in the general population are very limited. Different approaches to behaviour change are needed and should be tested empirically before being widely promoted. For example, the availability of foods and better access to recreational and sporting facilities may have a greater impact on dietary and exercise patterns respectively, than health professional advice.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are extremely grateful to the following investigators who provided us with data: M. Shipley (WHO Factories), L. Wilhelmsen (Gothenberg Study), I. Hjermann (The Oslo Study), J. Shaten (MRFIT Study), T. Miettinen (Finnish men), J. Muir and T. Lan-caster (OXCHECK Study), J. Baron (Abingdon), S. Pyke (Family Heart - men), S. Boles (Take Heart), T. Ekbom (CELL Study), A Goble and M. Worcester (FARIS). The following investigators replied to our request but were unable to provide us with further data for various reasons: G. Payne (HDFP trial), D. Morisky (Johns Hopkins), R. Stamler (Stamler 1989), S.Knutson (Tromso men), C Connell (Connell 1995), P. Whelton and M. Espelund (TONE 1998), A Steptoe (Change of Heart), G Berglund (Persson 1996), Emmons K (WHP). We would also like to thank M. Napoli (Center for Medical Consumers) for her help with the plain language summary.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

MRC Health Services Research Collaboration, UK.

Systematic Reviews Training Unit, University of London, UK.

Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol, UK.

Department of Epidemiology & Population Health, London School of Hygeine & Tropical Medicine, UK.

External sources

NHS Centre for Reviews & Dissemination, University of York, UK.

Health Education Authority, London, UK.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Primary care. Random allocation by health centre (centres paired according to size, number of doctors and personnel). Unit of analysis was individual |

| Participants | Men and women on anti-hypertensive drugs aged 30-69 years N=159 |

| Interventions | Group based video taped lifestyle counselling: Dietary change, stress management, increased physical activity. home blood pressure monitoring. Up to 8 group sessions. |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes. Change in anti-hypertensive treatment, weight, hypertension, cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, life quality |

| Notes | All patients followed the same schedule for reduction and withdrawal of antihypertensive drugs. Concluded that intervention was effective in reducing hypertensive medication |

| Methods | Primary care. Random allocation by health centre (centres paired according to size, number of doctors and personnel) . Unit of analysis was individual |

| Participants | Men and women on anti-hypertensive drugs aged 30-69 years N=129 |

| Interventions | Group based video taped lifestyle counselling: Dietary change, stress management, increased physical activity. home blood pressure monitoring. Up to 8 group sessions. |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes. Change in anti-hypertensive treatment, weight, hypertension, cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, life quality |

| Notes | All patients followed the same schedule for reduction and withdrawal of antihypertensive drugs. Concluded that intervention was effective in reducing hypertensive medication |

| Methods | Primary care Random allocation by individual |

| Participants | Men and women, mean age 42 years (range 25-60) N=368 |

| Interventions | Diet, weight control, smoking advice, exercise, alcohol advice carried out by nurse Duration 1 year |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol, smoking prevalence |

| Notes | Main focus was on dietary change, but despite self reported behaviour change, no changes in blood cholesterol found |

| Methods | Community screening and volunteers Randomisation by individual |

| Participants | Men and women aged 60-85 with mild diastolic hypertension and modestly overweight N=56 |

| Interventions | Nutritionist supervised. Individual weight loss goals, exercise and diet self-monitoring with behavioural feedback. Duration 6 months |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes. Weight, urinary sodium, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, waist-hip ratio, exercise |

| Notes | Reduction in weight and systolic blood pressure in those folowed up. Authors report good compliance with intervention. Authors conclusions: results indicate intervention will lower borderline or mild diastolic hypertension |

| Methods | Volunteers screened Randomisation by individual |

| Participants | Men and women aged 29+ with unmedicated high-normal blood pressure. Overweight and not performing regular aerobic exercise. N=79 |

| Interventions | Exercise physiologist supervised exercise and behavioural intervention including diet. Duration 6 months |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, glucose tolerance, weight, exercise test |

| Notes | Another intervention group received only exercise intervention. Authors conclusions: Exercise alone reduced BP and the addition of behavioural weight loss programme enhanced this |

| Methods | Primary care screening Randomisation of individuals in 2×3 factorial design |

| Participants | People with at least two risk factors in addition to moderately raised blood cholesterol Men and women, mean age 49 years (30-59) N=681 |

| Interventions | Factor 1: Counselling on health problems and risk factor management, food purchasing, exercise vs. usual care Factor 2: Pravastatin vs. placebo vs control without drug Duration 1 year |

| Outcomes | Total mortality and CHD mortality Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol, smoking prevalence, exercise score |

| Notes | At one year counselling intervention main effects showed lower blood cholesterol and lower Framingham risk factor scores compared with groups not receiving counselling intervention. No significant differences in blood pressures, smoking prevalence, or exercise score |

| Methods | General practice, cluster allocation by minimisation to balance for social deprivation, practice nurse hours and fundholding status. 20 practices. Unit of analysis was general practice |

| Participants | Men and women mean age 47 years with one or more cardiovascular risk factors. No treatment. N=883 |

| Interventions | Nurse led stages of change behavioural counselling on smoking, diet, physical activity. 2 or 3 20 minute counselling sessions + telephone contact |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes. Diet, exercise, smoking habits, blood pressure, cholesterol, weight, BMI Follow up 4 and 12 months |

| Notes | Based on stages of change model. Less smokers at baseline in intervention group (39%) than control (49%) Problems with recruitment and dropout - more recruited to intervention than control group - 59% of patients followed up at 12 months. Those at higher risk received more intensive treatment |

| Methods | Worksite volunteers Randomisation by worksite. Unit of analysis was individual |

| Participants | Men and women age 19-67 N=1432 |

| Interventions | Health risk assessment and individual health counselling Educational classes and self-help material Duration 1 year |

| Outcomes | Total cholesterol, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, BMI, exercise frequency One year follow up |

| Notes | Large loss to follow up |

| Methods | Primary care Random allocation of households to intervention and control groups |

| Participants | Primary care screening, mean age 50 (40-59) N=3941 |

| Interventions | Intensity of intervention depended on individual’s level of risk. Nurse counselling on diet, weight, smoking, exercise, alcohol Duration 1 year |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol, smoking prevalence |

| Notes | Two control groups used: internal to study used for comparisons in this review. Drop outs were more likely to have high CVD risk factor levels. Overall predicted risk reduction of 12% achieved but thought to be too costly in practice - no cost-effectiveness analysis conducted however |

| Methods | Primary care Random allocation of households to intervention and control groups |

| Participants | Primary care: women age 50 (40-59) N=2619 |

| Interventions | Intensity of intervention depended on level of individual’s risk Nurse counselling on diet, weight control, smoking advice, exercise, alcohol Duration 1 year |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol, smoking prevalence |

| Notes | Two control groups used but internal control used in this review |

| Methods | First degree relatives of AMI, CABG and PTCA patients Randomised by family. |

| Participants | Families of people with CHD event, age 18-69, N=442 |

| Interventions | Individualised risk factor advice. 3 months dietary advice and lipid lowering medication if required |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes Systolic blood pressure diastolic blood pressure, cholesterol, smoking, BMI and CVD risk |

| Notes | Results are for people without cardiovascular disease attending combined primary and secondary prevention clinic. Information on baseline and follow up smoking prevalence not available. No significant effect of intervention on smoking quit rate |

| Methods | First degree relatives of AMI, CABG and PTCA patients Randomised by family. |

| Participants | Families of people with CHD event, age 18-69, N=658 |

| Interventions | Individualised risk factor advice. 3 months dietary advice and lipid lowering medication if required |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes Systolic blood pressure diastolic blood pressure, cholesterol, smoking, BMI and CVD risk |

| Notes | Results are for people without cardiovascular disease attending combined primary and secondary prevention clinic. Information on baseline and follow up smoking prevalence not available. No significant effect of intervention on smoking quit rate |

| Methods | High risk groups identified from epidemiological surveys, opportunistic screening, volunteers. Randomisation by individual, stratified by sex, centre and OGTT result |

| Participants | Overweight or with family history of type 2 diabetes men and women aged 40-64 years with impaired glucose tolerance N=523 |

| Interventions | Nutritionist delivered individual and group dietary advice. Weight goal established with physician and nutritionist and reguar assessment. Supervised exercise. Each person had 7 sessions in the first year and one session every 3 months subsequently |

| Outcomes | No clinical events outcomes. Development of diabetes, weight, diet, exercise, waist circumference, glucose, insulin, cholesterol, HDL, triglycerides, systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Follow up reported end of year 1 |

| Notes | Study planned for 6 years, recruited 1993 to 1998. In March 2000 study stopped on basis of results regarding reduction in incidence in diabetes in treatment group |

| Methods | Volunteers recruited Randomisation by individual |

| Participants | Men only, mean age 48 years (40-58) High risk N = 1222 |

| Interventions | Diet, smoking, exercise, antihypertensive drugs, cholesterol lowering drugs Duration 5 years |

| Outcomes | Total mortality, CHD mortality Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol, smoking prevalence |

| Notes | Large reductions in blood pressure and blood cholesterol achieved largely through drug treatments, reductions in smoking prevalence. Control group risk factors increased. CHD event rates higher in intervention group but stroke rates significantly lower. Concluded that adverse effects of drug treatment may explain lack of benefit |

| Methods | Primary care Selection of hypertensives by screening Randomisation of individuals |

| Participants | Men and women with hypertension on a prescribed regimen of diet or medication, mean age 47 years (18-65) N=86 |

| Interventions | Educational handbook on risk, impact and benefits of controlling hypertension. Individual problem solving sessions on medication, diet and exercise. Duration 6 months |

| Outcomes | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, weight, patient beliefs, symptom severity |

| Notes | Authors note reduction in diastolic blood pressure. Intervention affected patient beliefs |

| Methods | Population based Selection of high risk people by screening Randomisation of individuals |

| Participants | Men only, mean age 51 years (47-55) N=30,022 |

| Interventions | Diet, smoking, antihypertensive drugs, cholesterol lowering drugs Duration 11.8 years |

| Outcomes | Total mortality, coronary heart disease mortality Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol, smoking prevalence |

| Notes | Large falls in risk factors occurred in both intervention and control groups. Concluded that other strategies in high risk men are required to have a major impact on incidence of disease in the general population |

| Methods | Population screening Randomisation of individuals |

| Participants | Men and women, all hypertensives, age range 30-69 years N=10,940 |

| Interventions | Stepped care: Antihypertensive drugs, diet, smoking advice, weight control, exercise vs. Referred care: usual primary care Duration 5 years |

| Outcomes | Total mortality, CHD mortality, Stroke mortality Non-fatal CHD and stroke events Diastolic blood pressure |

| Notes | No reductions in smoking prevalence of blood cholesterol (data not published) but significant reductions in blood pressure. Total mortality, CHD and stroke mortality significantly lower in intervention group. Benefits attributed to treatment of high blood pressure and sustained over prolonged follow up |

| Methods | Randomization of individuals in a 2×2 factorial design |

| Participants | Men only, mean age 46 years (35-60) Moderately raised CVD risk factors - already involved in a primary prevention programme N=158 |

| Interventions | Diet and exercise advised Duration 6 months |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol Data also given on BMI, Waist/Hip ratio, HDL/LDL/VLDL cholesterol, tryglycerides, dietary intake, physical activity |

| Notes | Only data from control group (N=39) and diet and exercise group (N=39) used in this review |

| Methods | Community screening. Randomisation by individual using permuted block method, stratified by blood pressure |

| Participants | Untreated hypertensive men and women age 35-69 years N=111 |

| Interventions | Physician, public health nurse and nutritionist led education, counselling and practical sessions. Individual goals for sodium intake, weight control, walking and alcohol intake. Duration 18 months |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes. Urinary sodium and potassium, sodium reduction behaviours, alchohol intake, calcium intake, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure |

| Notes | Intervention associated with reduced systolic blood pressure, reduction in sodium excretion, alcohol consumption. No change in BMI, diastoilc blood pressure. Greater use of anti-hypertensive medication in control group |

| Methods | Patients from hypertension clinic Randomisation of individuals |

| Participants | Men and women, mean age 49 years (range 35-59) With hypertension and overweight N=50 |

| Interventions | Individually planned diet (1000-1500kcal per day) Advice on exercise and weight reduction, weekly meetings for 6 months then 3 weekly. Duration 12 months |

| Outcomes | No clinical events outcomes. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol, weight, food intake, urinary sodium and potassium |

| Notes | Intervention led to reduction in weight |

| Methods | Clinic attenders Randomisation by individual to a complex factorial design with 8 groups |

| Participants | Men and women, all hypertensives, mean age 54.1 years N=400 |

| Interventions | Antihypertensive drugs, weight control, general health advice vs. no extra educational interventions Duration 5 years |

| Outcomes | Total and CHD mortality |

| Notes | Better control of blood pressure (but values not reported), weight and better adherence with treatment and appointments in intervention group. Concluded that educational programmes for hypertensive patients were beneficial |

| Methods | Primary care screening 4 villages randomly assigned. Unit of analysis was individual |

| Participants | Men and women aged 40+ (mean 60) N=1102 |

| Interventions | Home visits by public health nurse students aimed at weight reduction, physical activity, compliance with medication. Trained volunteers and community leaders involved. Education classes and speeches. Duration 6 months |

| Outcomes | No clinical events outcomes. Blood pressure, behavioural changes |

| Notes | Hypertensives received more intensive intervention |

| Methods | Participants in health survey screened for abnormal glucose tolerance |

| Participants | Men and women with abnormal glucose tolerance and high BMI mean age 55 N=301 |

| Interventions | One month stay in full-board wellness centre. Scheduled aerobic physical activity, stress management, diet modification, smoking cessation encouraged |

| Outcomes | No clinical events outcomes. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, cholesterol, fibrinolysis, BMI, physical fitness, Follow up of 12 months |

| Notes | Not all participants were followed up Intense programme compared with usual care group |

| Methods | Primary care opportunistic screening. Randomisation by general practice (N=22). Unit of analysis was individual |

| Participants | Men aged 30-59 at high risk for CVD by infarction score N=127 |

| Interventions | Counselling on health promotion and behaviour change. Self help and self monitoring. Duration 1 year |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcome. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, weight, resting pulse, cholesterol, lipid profile, smoking habit, thiocyanate, C-peptide |

| Notes | Kanfer and Gaelick (1986), and Meichenbaum (1986), person centred and self directed psychological approach. Self efficacy was related to exercise change |

| Methods | Worksite, population and volunteer screening Randomisation by individual |

| Participants | Men only, mean age 46 years (35-47) N=12,866 |

| Interventions | Diet, smoking, weight, antihypertensive drugs Duration 6 years |

| Outcomes | Total mortality, coronary heart disease mortality stolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol, smoking prevalence |

| Notes | Small reductions in blood cholesterol concentration. Large reductions in blood pressure and smoking rates. No significant reduction in disease events. Concluded that possibly effective in sub-groups but no net benefit because of potentially harmful effects of antihypertensive drugs used. Small benefits emerging after prolonged follow up |

| Methods | Randomisation of hyperinsulinaemics by individual within cross-sectional study of treated hypertensives and normotensive controls |

| Participants | Men and women, mean age 56.1 years with hyperinsulinaemia but not diabetic N=59 |

| Interventions | Group education and individual counselling on diet and physical activity by nurse, dietician and physiotherapist. Duration 1 year |

| Outcomes | Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol, LDL/HDL cholesterol ratio, weight, waist hip ratio, blood glucose, insulin, c-peptide, urate, glucose tolerance |

| Notes | 63 randomised Intervention group had reduced weight, waist hip ratio, blood pressure and LDL/HDL ratio. Also dietary improvements. Controls informed of hyperinsulinaemic status |

| Methods | Worksite screening Randomisation by individual |

| Participants | Men and women, mean age 50 years (range 28-65) N=89 |

| Interventions | Multidisciplinary education and counselling. Weight reduction in obese, diet, physical activity, stress management, smoking cessation Duration 18 months |

| Outcomes | Risk scores, BMI, waist hip ratio, sick days, sedentary behaviour, heart rate, smoking, CHD risk factors, glucose, insulin, liver function, cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) |

| Notes | 128 randomised (Intervention group: 5 did not attend baseline, 16 dropouts or excluded for medical reasons at 12 months, 1 lost to followup at 18 month; control group corresponding figures 10, 5, 2 respectively) |

| Methods | People with impaired glucose tolerance identified in research studies, hospital databases and by GPs. Randomisation by individual |

| Participants | Men and women aged 24-75 years with impaired glucose tolerance identified in 2 OGTT N=78 |

| Interventions | Dietician and physiotherapist counselling on diet and physical activity. Targets set by Stages of Change. Duration 6 months |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes. Diet, aerobic physical activity, glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, cholesterol, weight, BMI, waist hip ratio |

| Notes | Intervention group showed increased physical activity, decreased fat consumption but no change in glucose tolerance |

| Methods | Open, randomized 2×2 factorial design |

| Participants | Men and women, mean age 40 years N=219 |

| Interventions | Diet advice and supervised endurance exercise programme Duration 1 year |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes reported Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol Also measured haemostatic factors, BMI, body weight, waist hip ratio, aerobic capacity, thiocyanate, triglycerides, HDL/LDL cholesterol |

| Notes | Comparison used in this review is between the control group (N=43) and the diet+exercise group(N=65). Diet only and exercise only groups were not considered as single interventions |

| Methods | Primary care practices in urban area Randomisation by household |

| Participants | Men and women, mean age 49 years (35-64) No risk screening N=11,090 |

| Interventions | Diet, smoking advice, weight control, alcohol advice, exercise, protocols for management of high blood pressure and raised blood cholesterol vs. usual care. Duration 3 years |

| Outcomes | Total mortality and CHD mortality Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol, smoking prevalence, BMI |

| Notes | Changes in diet and small changes in blood cholesterol, blood pressure and body mass index. No effect on smoking prevalence. Concluded that primary prevention programmes were able to achieve benefits which were real but must be weighted against the costs in relation to other priorities. Study was not designed to examine mortality effects but those randomised to health checks in years 1 to 3 were considered to be intervention group and those randomised to checks in year 4 were the control group. Deaths up to year 4 were compared |

| Methods | Volunteers screened Randomised by individual stratified for sex, diastolic blood pressure and weight |

| Participants | Men and women aged 18-59 Mild hypertension N=156 |

| Interventions | Nutritionist, health educator, behavioural psychologist, general internist supervised Aerobic exercise, diet, relaxation 8 weekly meetings, subsequent meeting at 3 months |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, cholesterol, physical activity, self-reported adverse effects dietary intake, weight, 24 hour uring (sodium, potassium) Follow up at 1 year |

| Notes | Four treatment arms other two had propanolol. Intervention did not promote persistent behaviour change. |

| Methods | Volunteers screened Randomised by individual stratified for sex, diastolic blood pressure and weight |

| Participants | Men and women aged 18-59 Mild hypertension on propanolol N=156 |

| Interventions | Nutritionist, health educator, behavioural psychologist, general internist supervised Aerobic exercise, diet, relaxation. 8 weekly meetings, subsequent meeting at 3 months |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, cholesterol, physical activity, self-reported adverse effects, dietary intake, weight, 24 hour uring (sodium, potassium) Follow up at 1 year |

| Notes | Four treatment arms - other two did not have propanolol. Intervention did not promote persistent behaviour change. |

| Methods | Worksite screening. Randomisation of individuals |

| Participants | Volunteers from worksites, raised body weight, high pulse rate and DBP 80-89mmHg Men and women, mean age 37.5 (30-44) N=201 |

| Interventions | Diet, weight control, exercise, alcohol Duration 5 years |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes Systolic BP, diastolic BP |

| Notes | Small but significant reduction in blood pressure; other risk factors not reported. Volunteers who were thought unlikely to comply with intervention (eg. heavy drinkers, very obese) were excluded from the trial |

| Methods | Volunteers screened for HDL and LDL cholesterol Randomisation by individual |

| Participants | Men aged 30-64, HDL <45mg/dl, LDL 126-189mg/dl 126-209mg/dl N=98 |

| Interventions | Individual diet counselling and group education. Weight loss groups. Supervised and home-based exercise. Duration 1 year |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes. Diet assessment, body weight, exercise tests, CHD risk factors |

| Notes | Concluded that diet and aerobic exercise was effective in reducing LDL cholesterol |

| Methods | Volunteers screened for HDL and LDL cholesterol Randomisation by individual |

| Participants | Post-menopausal women aged 45-64, HDL <60mg/dl, LDL N=89 |

| Interventions | Individual diet counselling and group education. Weight loss groups. Supervised and home-based exercise. Duration 1 year |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes. Diet assessment, body weight, exercise tests, CHD risk factors |

| Notes | Concluded that diet and aerobic exercise was effective in reducing LDL cholesterol |

| Methods | Clinic attending hypertensives Randomisation by individual after stratification by serum cholesterol, smoking habit and target organ damage |

| Participants | All men, age 50-72 years N=508 |

| Interventions | Smoking advice + nicotine gum, dietary habits, weight control, spouse involved. Lipid lowering drugs used in needed. vs. usual care. All patients on antihypertensive medication Duration 6 years |

| Outcomes | Total mortality, CHD and stroke mortality Non-fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, new onsets of claudication and angina Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol, (HDL, LDL), smoking prevalence, body weight, BMI, blood glucose, heart rate, gGT, HbA1c |

| Notes | Significant reductions in blood cholesterol and smoking were achieved. No changes in diastolic blood pressure and HbA1c. Stroke incidence reduced in intervention group |

| Methods | Workplace screening. Matched pairs of worksites randomised. Unit of analysis was worksite |

| Participants | Men and women mean age 40 (17-73). N=1977 |

| Interventions | Stage of change model used; motivational, educational, workplace environment and community reinforcement; focus on smoking and food choices. Duration 18 months |

| Outcomes | Smoking, blood cholesterol, dietary intake. |

| Notes | Despite documented implementation of interventions no evidence that changes in smoking, cholesterol concentration of dietary intakes were greater than improvements associated with secular trends observed in control sites. Large variation in rates of stopping smoking between sites suggested variable use and uptake of interventions |

| Methods | Population screening. Selected for raised blood cholesterol. Randomisation by individual. |

| Participants | Men only, mean age 45.2 (40-49). N=1232 |

| Interventions | Diet and smoking Duration 5 years |

| Outcomes | Total mortality, CHD mortality, smoking prevalence, blood cholesterol |

| Notes | Reduction in smoking rates and blood cholesterol. Significant reduction in cardiovascular disease events. Concluded that advice to stop smoking and change eating habits reduces first myocardial infarctions and sudden deaths |

| Methods | Randomisation of individuals at high risk detected by primary care screening |

| Participants | Men and women, age 30-45 years N=1373 |

| Interventions | Physician and dietician counselling of family, diet, smoking advice, exercise Duration 6 years |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol, smoking prevalence |

| Notes | Participants showed little interest in group meetings. Small significant reductions in blood cholesterol but no effects on smoking or blood pressure. Mortality and clinical event follow up is proceding in the trial and lead author has not yet published data |

| Methods | Wives of the men randomised in the Tromso trial are considered to be a seperate trial. Randomisation therefore by husband |

| Participants | Women aged 30-45 N=809 |

| Interventions | Physician and dietician counselling on diet, smoking, exercise Duration 6 years |

| Outcomes | No clinical event data Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood cholesterol, smoking prevalence |

| Notes | Mortality data may be available in the future |

| Methods | Diabetes clinic. Randomisation by individual |

| Participants | Newly diagnosed NIDDM, men and women aged 40-64 years N=86 |

| Interventions | Education on weight reduction, diet, physical activity. Goals and regular monitoring. Duration 12 months |

| Outcomes | No clinical event data. Weight reduction, normoglycaemia, correction of dislipidaemias, blood pressure |

| Notes | Intervention and control received 3 months basic diabetes education before randomisation |

| Methods | Volunteers recruited. Randomisation of individuals |

| Participants | Women aged 44-50 N=535 |

| Interventions | Cognitive- behavioural programme with intensive group and individual guidance on diet, exercise and prevention of weight gain. Duration 4.5 years |

| Outcomes | No clinical event outcomes Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, blood LDL and HDL cholesterol |

| Notes | One accidental death. Participants were receptive to preventive approach and were successful in making initial lifestyle changes |

| Methods | Worksites in Belgium, Italy, Poland, Spain, UK; randomisation by factory. Unit of analysis was factory |

| Participants | Men only, mean age 48.5 (40-59) N=63,732 |

| Interventions | Diet, smoking, weight, exercise, antihypertensive drugs, mass media Control factories had usual occupational health service Duration 6 years |

| Outcomes | Mortality: cause specific blood pressure, blood cholesterol, smoking rates |

| Notes | Only small reductions in risk factors found. Spanish arm not included in event ascertainment. Belgium arm showed significant reduction in mortality and was written up seperately. Concluded that advice on risk factor reduction is effective to the extent that it is taken up and seems to be safe |

| Methods | Volunteers Randomisation by individual |

| Participants | Overweight men and women aged 40-55. Non diabetic but with 1 or 2 parents with type 2 diabetes. N=80 |

| Interventions | Multidisciplinary led behavioural strategies. Group and individual education. Low calorie, low fat diet. Supervised walking and other activities. Duration 2 years |

| Outcomes | No clinical events outcomes. Eating and exercise behaviours, weight, incidence of diabetes, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, cholesterol |

| Notes |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Andersen 1999 | Both groups received an intervention |

| Basler 1985 | Non-random allocation |

| Blake 1987 | No risk factor change measured or reported |

| Bruno 1983 | Six month data not available |

| Burke 1999 | Participants were younger adults |

| Cambien 1981 | Participants were younger adults |

| Carlberg 1992 | No risk factor data measured or reported |

| Crouch 1986 | Control group received some elements of intervention |

| Da Qing 1997 | No risk factor changes reported |

| Domarkene 1990 | Non-random allocation |

| DPP 1999 | Control group received some elements of intervention |

| Dunn 1997 | Both groups recevied an exercise only intervention |

| Edye 1989 | Non-random allocation |

| Fielding 1994 | Control group received some elements of intervention |

| Fox 1996 | Non-random allocation |

| Frommer 1990 | Inadequate randomisation |

| Fuchs 1993 | Both groups received an intervention |

| Fullard 1987 | Non-random allocation |

| Gemson 1990 | Control group received some elements of intervention |

| Gemson 1995 | Control group received some elements of intervention |

| German 1994 | Control group received some elements of intervention |

| Gomel 1993 | Inadequate randomisation |

| Gordon 1997 | Control group received some elements of intervention |

| Hanlon 1995 | Six month data not available |

| Haskell 1988 | Secondary prevention |

| Hedberg 1998 | Non-randomised allocation |

| Jula 1990 | Inadequate randomisation |

| Kawakami 1999 | Participants were younger adults |

| Ketola 2001 | Mixed primary and secondary prevention |

| Knappe 1982 | Inadequate randomisation |

| Kreuter 1996 | Outcome is contemplation of quitting smoking |

| Lasater 1986 | No risk factor changes measured or reported |

| Lauritzen 1995 | Health screening only |

| Leighton 1990 | Control group received some elements of intervention |

| Lindahl 1998 | Uncontrolled study |

| Lovibond 1986 | Control group received some elements of intervention |

| Macdonald 1990 | RCT assessing simvastatin |

| Martinez-A 1990 | No risk factor changes measured or reported |

| McCance 1985 | Two month follow up |

| McCann 1997 | Control group received some element of the intervention |

| Meimanaliev 1991 | Non-random allocation |

| Miemanaliev 1993 | Non-random allocation |

| Murray 1986 | No control group baseline data available |

| Nikitin 1991 | Non-random allocation |

| Nisbeth 2000 | Participants were younger adults |

| Nolte 1997 | Two month follow up |

| Ostwald 1989 | Control group received some element of the intervention |

| Patterson 1988 | No risk factor changes measured or reported |

| Persson 1996 | No 6 month follow up data available. After 6 months pharmacological treatment was provided to intervention group patients (67% on lipid-lowering drugs and 13% on antihypertensives at 1 year) |

| Pierce 1984 | No risk factor change measured or reported |

| Reid 1995 | Control group received some element of the intervention |

| Robson 1989 | No risk factor changes measured or reported |

| Rosamond 2000 | Non-random allocation |

| Rowland 1994 | Non-random allocation |

| S-E London 1977 | Intervention not characterised |

| Schwandt 1999 | Children and families |

| Smith 1991 | Non-random allocation |

| Steinbach 1982 | Non-random allocation |

| TOMHS 1991 | All participants received intervention |

| TONE 1998 | Three month blood pressure follow up |

| Tsuyuki 1999 | Secondary prevention |

| Velonakis 1999 | Non-random allocation |

| Volozh 1991 | Non-random allocation |

| WHP | Numbers in intervention and control group not reported |

| Wisewoman 1999 | Control group received some element of the intervention |

| Working Well Trial | Baseline data only, no follow up |

| Wu 1999 | Non-random allocation |

DATA AND ANALYSES

Comparison 1. Multiple risk factor intervention versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Total mortality | 9 | 125167 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.92, 1.01] |

| 2 Coronary heart disease mortality | 9 | 125167 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.89, 1.04] |

| 3 Systolic blood pressure | 38 | 53872 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | −3.62 [−3.93, −3.31] |

| 4 Diastolic blood pressure | 39 | 64859 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | −2.76 [−2.93, −2.59] |

| 5 Blood cholesterol | 35 | 66106 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | −0.07 [−0.08, −0.06] |

| 6 Smoking prevalence | 15 | 48948 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.70, 0.94] |

| 7 Systolic blood pressure (individual analysis or cluster) | 38 | 53872 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −2.68 [−3.64, −1.72] |

| 7.1 Cluster randomisation - analysis by cluster | 2 | 19355 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.56 [−2.26, 3.38] |

| 7.2 Individual randomisation | 32 | 33157 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −3.24 [−4.16, −2.31] |

| 7.3 Cluster randomisation - analysis by individual | 4 | 1360 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.03 [−3.28, 3.34] |

| 8 Diastolic blood pressure (individual analysis or cluster) | 39 | 65362 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −2.01 [−2.63, −1.39] |

| 8.1 Cluster randomisation - analysis by cluster | 2 | 19348 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −0.27 [−0.81, 0.27] |

| 8.2 Individual randomisation | 34 | 44619 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −2.33 [−2.94, −1.72] |

| 8.3 Cluster randomisation - analysis by individual | 4 | 1395 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −0.00 [−1.07, 1.07] |

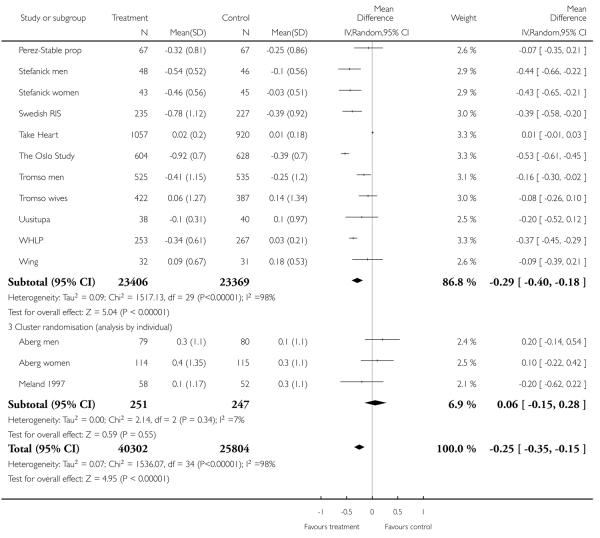

| 9 Cholesterol (individual analysis or cluster) | 35 | 66106 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −0.25 [−0.35,−0.15] |

| 9.1 Cluster randomisation - analysis by cluster | 2 | 18833 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.01 [−0.03, 0.05] |

| 9.2 Individual randomisation | 30 | 46775 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −0.29 [−0.40, −0.18] |

| 9.3 Cluster randomisation (analysis by individual) | 3 | 498 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.06 [−0.15, 0.28] |

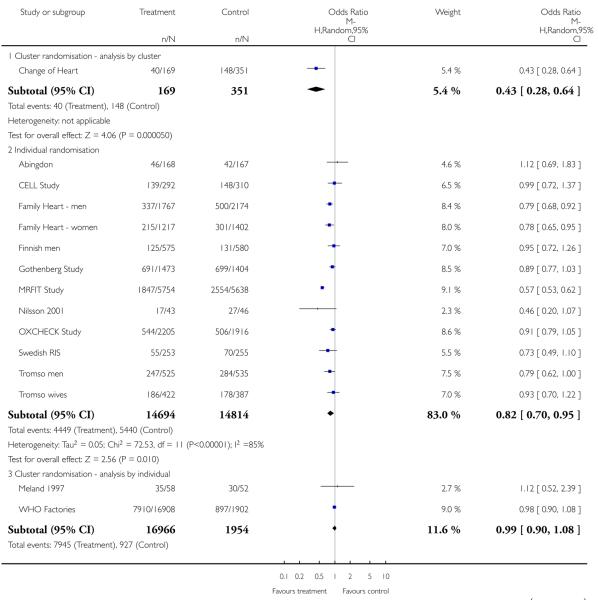

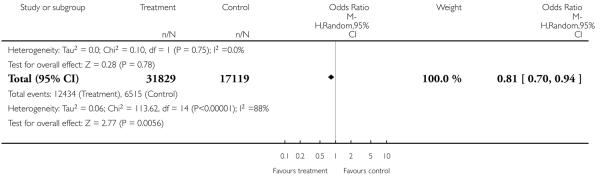

| 10 Smoking prevalence (individual analysis or cluster) | 15 | 48948 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.70, 0.94] |

| 10.1 Cluster randomisation - analysis by cluster | 1 | 520 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.28, 0.64] |

| 10.2 Individual randomisation | 12 | 29508 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.70, 0.95] |

| 10.3 Cluster randomisation - analysis by individual | 2 | 18920 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.90, 1.08] |

Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Multiple risk factor intervention versus control, Outcome 1 Total mortality.

Review: Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease

Comparison: 1 Multiple risk factor intervention versus control

Outcome: 1 Total mortality

|

Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Multiple risk factor intervention versus control, Outcome 2 Coronary heart disease mortality.

Review: Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease

Comparison: 1 Multiple risk factor intervention versus control

Outcome: 2 Coronary heart disease mortality

|

Analysis 1.3. Comparison 1 Multiple risk factor intervention versus control, Outcome 3 Systolic blood pressure.

Review: Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease

Comparison: 1 Multiple risk factor intervention versus control

Outcome: 3 Systolic blood pressure

|

|

Analysis 1.4. Comparison 1 Multiple risk factor intervention versus control, Outcome 4 Diastolic blood pressure.

Review: Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease

Comparison: 1 Multiple risk factor intervention versus control

Outcome: 4 Diastolic blood pressure

|

|

Analysis 1.5. Comparison 1 Multiple risk factor intervention versus control, Outcome 5 Blood cholesterol.

Review: Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease

Comparison: 1 Multiple risk factor intervention versus control

Outcome: 5 Blood cholesterol

|

|

Analysis 1.6. Comparison 1 Multiple risk factor intervention versus control, Outcome 6 Smoking prevalence.

Review: Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease

Comparison: 1 Multiple risk factor intervention versus control

Outcome: 6 Smoking prevalence

|

Analysis 1.7. Comparison 1 Multiple risk factor intervention versus control, Outcome 7 Systolic blood pressure (individual analysis or cluster).

Review: Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease