Abstract

We tested the relationship of objectively-measured sleep quantity and quality with positive characteristics of the child. Sleep duration, sleep latency, and sleep efficiency were measured by an actigraph for an average seven (range = 3 to 14) consecutive nights in 291 eight-year-old children (SD = 0.3 years). Children's optimism, self-esteem, and social competence were rated by parents and/or teachers. Sleep duration showed a non-linear, reverse J-shaped relationship with optimism (P = 0.02) such that children with sleep duration in the middle of the distribution scored higher in optimism compared to children who slept relatively little. Shorter sleep latency was related to higher optimism (P = 0.01). The associations remained when adjusting for child's age, sex, body mass index and parental level of education; the effects of sleep on optimism were neither changed when the parents' own optimism was controlled. In conclusion, sufficient sleep quantity and good sleep quality are associated with positive characteristics of the child, further underlining their importance in promoting well-being in children.

Keywords: Sleep quantity, sleep quality, optimism, self-esteem, childhood

Introduction

Insufficient sleep quantity and poor sleep quality, defined as short sleep duration, long sleep latency and low sleep efficiency, are common among adults as well as children. In industrialized countries, the average sleep duration among adults (Bonnet & Arand, 1995, Rajaratnam & Arendt, 2001) and children (Iglowstein et al., 2003) has decreased substantially during the past few decades, and complaints about poor sleep quality are frequent (Heath et al., 1998; Sateia et al., 2000). Estimates are that between 20 – 40% of children suffer from poor sleep (Fricke-Oerkermann, et al., 2007; Liu, et al., 2005; Smaldone, et al., 2007), with half of them having persistent problems over time (Fricke-Oerkermann, et al., 2007).

Epidemiological evidence in adults shows that both short and/or long sleep duration and poor sleep quality relate to a wide spectrum of detrimental physical health consequences, such as obesity (Gangwisch, et al., 2005; Hasler, et al., 2004; Patel, et al., 2008; Vioque et al., 2000), type 2 diabetes (Ayas et al., 2003b; Gangwisch et al., 2007; Knutson et al., 2006; Yaggi et al., 2006), hypertension (Gangwisch et al., 2006), coronary heart disease (Ayas et al., 2003a), and even premature death (Ferrie et al., 2007; Heslop et al., 2002; Hublin et al., 2007; Kripke, et al., 2002; Tamakoshi et al., 2004; Kojima et al., 2000). Insufficient sleep quantity is also associated with poor health in children and adolescents. Children with shorter sleep duration are more likely to be obese (Patel & Hu, 2008; for meta analyses see Chen et al., 2008, and Cappuccio et al., 2008), and prospective studies show that short sleep duration predicts a higher body mass index (BMI) later in childhood (Reilly et al., 2005) and in adolescence (Snell et al., 2007). Furthermore, poor sleep in children is associated with poorer cognitive performance (Meijer et al., 2000; Randazzo et al, 1998; Sadeh et al., 2002, Touchette et al., 2007), and with depression, anxiety, conduct problems, and hyperactivity (Aronen et al., 2000; Cohen-Zion et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2002; Gregory et al., 2004; Ivanenko et al., 2006; El-Sheikh et al., 2007).

Relative to the wealth of studies focusing on the negative consequences of poor sleep, much less is known about the beneficial consequences of sufficient sleep quantity and good sleep quality. There is evidence that adults who get adequate sleep report more optimism and satisfaction with life compared to adults who sleep less than six hours a night (National Sleep Foundation, 2002). Experimentally-induced sleep deprivation in adults results in a gradual reduction in optimism and sociability, suggesting that the association between sufficient sleep and these positive characteristics may be causal (Haack & Mullington, 2005). In adolescents, longer sleep duration predicts prospectively higher self-esteem (Fredriksen et al., 2004). However, we are not aware of any studies focusing on associations between sufficient sleep quantity, good sleep quality, and positive characteristics in young children.

Accordingly, we examined if objectively measured sleep quantity and quality are associated with optimism rated by parents, and with self-esteem and social competence rated by parents and teachers in 8-year-old children. We focused on optimism, self-esteem, and social competence as a wealth of evidence suggests that these are important characteristics promoting good physical and mental health in children and/or in adults (Aspinwall & Taylor, 1992; Ben-Zur, 2003; Bromberger & Matthews, 1996; Burt, Obradovic, Long, & Masten, 2008; Carvajal et al., 1998; Chang & Mackenzie, 1998; McGee & Williams, 2000; Matthews et al., 2004; Orth, Robins, & Roberts, 2008; O’Donnell et al., 2008; Räikkönen et al., 1999; Reitzes & Mutran, 2006; Roberts et al., 1998; Scheier & Carver, 2003; Stamatakis et al., 2004; Trzesniewski et al., 2006). We hypothesized that children whose sleep duration is sufficient (not short or long in duration) and who have shorter sleep latency and higher sleep efficiency are more optimistic and less pessimistic, and have higher self-esteem and social competence, relative to their same-aged peers with compromised sleep quantity and quality.

Method

Participants

The children came from an initial cohort comprising 1049 infants born between March 1 and November 30 of 1998 in Helsinki, Finland, and their mothers. In 2006, children and their parents were invited to participate in a follow-up with a focus on individual differences in physical and psychological development (Räikkönen et al., 2009). Nine-hundred and fifty-eight (91.3%) mothers of the initial cohort gave permission to be included in the follow-up, 922 (87.9%) could be contacted. Of these, a sub-sample of 413 children was invited for a follow-up examination, and 321 (77.7%) agreed to participate. Non-participation did not relate to child's gender, birth date, weight, length, head circumference or BMI at birth, birth order, mode of delivery, mother's gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, age, height, weight, BMI, occupational status or blood pressure at delivery, alcohol consumption, licorice confectionery consumption or stress during pregnancy (all p-values > 0.10); non-participation was related to more frequent maternal smoking during pregnancy (p = 0.02). The Ethical Committee of the City of Helsinki Health Department and the Ethical Committee of the Helsinki University Hospital of Children and Adolescents at Helsinki and the Uusimaa Hospital District approved the project. Each child and its parent gave an informed consent.

Of the 321 children participating in the follow-up, 305 participated in the actigraphy protocol, of whom 291 (91%; 150 girls and 141 boys) provided valid readings. Three hundred and five children had maternal and 227 children had paternal ratings of child optimism, self-esteem, and social competence available; 255 children had teacher ratings of child self-esteem and social competence available. The analyses excluded children who, according to parental report, had been diagnosed with a developmental delay (n = 3) or Asperger syndrome (n = 1).

Measures

Sleep quantity and quality

Sleep parameters were estimated from actigraphy data by automatic scoring (Actiwatch AW4, Cambridge Neurotechnology Ltd, UK) and subsequent manual verification. The wrist actigraph was approximately the size of a standard wristwatch and provides a non-intrusive instrument to measure sleep parameters by assessing body movement (Sadeh et al., 1995). As described elsewhere (Paavonen et al., 2009; Pesonen et al., 2009a), the participants were instructed to wear the actigraphs for at least 7 consecutive days on their nondominant wrist; on average, the devices were worn for 7.1 days (SD = 1.2; 3-4 days, n = 2; 5 days, n = 6; 6 days, n = 43; 7 days, n = 171; 8 days, n = 41; 9 days, n = 25; 10 days, n = 6; 11-14 days, n = 3), including nights on weekdays (mean = 5.1, SD = 1.0; range 1-10) and weekends (mean = 2.0, SD = 0.4; range 1-4). We instructed the parents to keep a sleep log on bedtimes and waking times, temporary pauses in actigraph registration (eg, while taking a shower), and significant events that might affect sleep quantity or quality (illness, pain, injury, travel, or other events likely to disturb sleep). The child was instructed to press a button (event marker) in the actigraph at bedtime and waking times. A completed sleep log was obtained from all participants, including both parent-reported sleep log and event markers on bedtimes and waking times reported by the child. The activity data were visually inspected to detect significant discrepancies among the sleep log, event markers, and the activity pattern. If there were several event markers for 1 night, the most recent was used and compared with the sleep log. If the sleep log was not synchronous with the event marker, the event marker was used to define the bedtime. We found high compliance in the sleep-log registrations in relation to the event markers; for 71% of the participants, no discrepancies were found; for 21%, a discrepancy was found for 1 or 2 nights; and, for 8%, a discrepancy was found for 3 or more nights. Nights were excluded from further sleep analysis if (a) the actigraph was not in use, (b) information on bedtime was missing, (c) the child was asleep according to the data of reported bedtime, (d) information on waking time was missing and the activity pattern was not unequivocally interpretable, or (e) the parent reported a change in normal life due to, for example, illness or travel. There were 257 participants (89%) without excluded nights. Data were scored with Actiwatch Activity & Sleep Analysis version 5.4 software with medium sensitivity and a 1-minute epoch duration. Sleep duration refers to the actual sleeping time. Sleep latency was defined as the time it takes the child to fall asleep after he or she went to bed. We used the validated Actiwatch algorithm (Tonetti, Pasquini, Fabbri, Belluzzi, & Natale, 2008), which defines “sleep start” as 10 minutes of consecutively recorded immobile data. Sleep efficiency was defined as the actual sleep time divided by the time in bed, thus including sleep latency.

Dispositional Optimism

Dispositional optimism of the children was rated by their parents. The parents filled in the Parent-rated Life Orientation Test of children (the PLOT; Lemola et al., 2009). The PLOT is composed of 8 items rated on a scale ranging from “not at all true of my child” (1) to “very true of my child” (4). Four items measure generalized optimistic expectations; a sample item is “When entering a new situation, my child expects to have fun.” The other four items measure generalized pessimistic expectations; a sample item is “My child often expects that the day will not turn out to be nice.” In addition to a total score derived from summing the optimism and reverse-scored pessimism items with a higher score indicating higher optimism, subscale scores with higher scores indicating higher optimism and higher pessimism can be derived by summing the four optimism items and the four pessimism items, respectively. As shown previously, the scale has good construct and convergent validity (Lemola et al, 2009). For the current analyses, mother and father ratings were averaged to increase reliability of measurement. The general coefficients of reliability (Tarkkonen & Vehkalahti, 2005) were .82, .85, and .78 for the combined mother- and father-rated total optimism scale, and optimism, and pessimism subscales, respectively.

Self-esteem

Parents and teachers filled in the Behavioral Rating Scale of Presented Self-Esteem in Young Children (Haltiwanger & Harter, 1988, Fuchs- Beauchamp, 1996). The scale has 15 items assessing young children's behavioral manifestations of self-esteem (e.g. self-confidence, independence, initiative), which are rated on a 4-point Likert scale. A sample item is “My child approaches challenging tasks with confidence.” The scale has good validity, internal consistency (Fuchs- Beauchamp, 1996; Verschueren et al., 2001), and stability over a three year period (r = .59) (Verschueren et al., 1998). For the current analyses, mother, father, and teacher ratings were averaged to increase reliability of measurement. In the current study, the general coefficient of reliability (Tarkkonen & Vehkalahti, 2005) was .92 for the combined mother-, father-, and teacher-rated scale.

Social Competence

Parents and teachers filled in the Social Competence subscale of the Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation Scale (the Short Form; SCBE-30; LaFreniere & Dumas, 1996). Social competence is defined as well-adjusted, flexible, emotionally mature and generally pro-social behavior, and is assessed by 10 items rated on a 6-point Likert scale. A sample item includes “My child comforts or assists another child in difficulty”. The scale has good construct validity and internal consistency (LaFreniere & Dumas, 1996). For the current analyses, mother, father, and teacher ratings were averaged to increase reliability of measurement. In the current study, the general coefficient of reliability (Tarkkonen & Vehkalahti, 2005) was .87 for the combined mother-, father-, and teacher-rated scale.

Covariates

Mothers and fathers reported their level of education, and the highest achieved level of education of either parent was dummy coded (with the lower level of education as the referent) and used in the analyses. In conjunction with a clinical visit, the child's weight (kg) and height (cm) were measured and BMI was calculated (kg/m2). Mothers and fathers also reported their own optimism using the Life Orientation Test—Revised (LOT-R, Scheier et al., 1994).

Statistical analyses

Linear associations of sleep duration, latency and efficiency with optimism, self-esteem and social competence were tested by using multiple linear regression analyses. Multiple linear regression analysis was also used in testing if sleep duration displayed a non-linear association with the psychological outcomes, such that children in the middle of the distribution would show higher optimism, and higher self-esteem and social competence. Non-linearity was modeled by entering a squared term of sleep duration together with sleep duration as a linear term (squared and linear terms centred around grand mean) in the regression equation.

In addition to treating the sleep variables as continuous, we treated them as categorical predictors in multiple regression analyses with the psychological variables as outcomes, as previous studies in this and other cohorts (e.g., Ferrie et al., 2007; Heslop et al., 2002; Paavonen et al., 2009; Pesonen et al., 2009b; Räikkönen et al., in press) found stronger effects for categorized compared to linear sleep parameters. Furthermore, categorizing sleep duration in particular is important because health effects have been found for both long and short sleep (Ayas et al., 2003a; Ferrie et al., 2007; Kaneita et al., 2006). As in our previous analyses (Paavonen et al., 2009; Pesonen et al., 2009a; Pesonen et al., 2009b, Räikkönen et al., in press) we used the 10th and 90th percentiles as cut-offs. For sleep duration, we used three groups (≤ 7.6 hours: ≤10th percentile, 7.7 to 9.3 hours: 10th – 90th percentile, ≥ 9.4 hours: > 90th percentile), with the middle category as the referent. Sleep latency (short to average vs. ≥ 32 minutes, > 90th percentile) and sleep efficiency (≤ 77.2%, ≤ 10th percentile vs. average to high) were dichotomized.

All analyses adjusted for child's sex, age, BMI, and parental level of education. Additionally, the associations between sleep and optimism were tested adjusting for parental optimism.

We calculated effect sizes by using a hierarchical multiple linear regression approach where sleep variables (each tested in a separate model) were entered into the regression equation in the last step, after the covariates (sex, age, BMI, parental education), with effect size being the R-square change in the explained variance.

Moreover, we tested whether any associations varied for boys and girls by including interaction terms in the models. In no instance was there a significant sex - interaction term (p values > 0.10) (data not shown). For this reason we report the results with both sexes combined.

Results

On average the children slept 8.4 hours (SD = 40 minutes), their average sleep latency was 19 minutes (SD = 11 minutes), and they were asleep on average for 84.0% (SD = 5.9%) of the time they spent in bed. Sleep duration correlated significantly with sleep efficiency (r = .80), and sleep latency (r = –.19), and sleep latency with sleep efficiency (r = –.48) (all P-values < 0.001). In Table 1 means and standard deviations for sleep duration, sleep latency, and sleep efficiency are displayed separately for girls and boys. In comparison to boys, girls slept on average longer (P = 0.001), their sleep latency was marginally shorter (P = 0.06) and their sleep efficiency higher (P = 0.01).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample.

| Girls N = 150 |

Boys N = 141 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Mean N |

(SD) (%) |

Mean N |

(SD) (%) |

P | |

| Child | |||||

| Age (years) | 8.1 | (0.3) | 8.2 | (0.3) | 0.096 |

| Weight (kg) | 28.3 | (5.2) | 29.4 | (7.5) | 0.160 |

| Height (cm) | 130.4 | (5.3) | 131.8 | (5.9) | 0.033 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 16.6 | (2.2) | 16.9 | (4.2) | 0.945 |

| Parent | |||||

| Maternal age (years) | 39.1 | (4.4) | 38.4 | (4.5) | 0.195 |

| Paternal age (years) | 41.1 | (5.1) | 40.9 | (6.4) | 0.819 |

| Highest education in the family | |||||

| High-school diploma | 16 | (10.7) | 23 | (16.3) | 0.158 |

| Vocational education | 48 | (32.0) | 31 | (22.0) | |

| Some college | 24 | (16.0) | 20 | (14.2) | |

| Degree beyond college | 62 | (41.3) | 67 | (47.5) | |

| PLOT-Scales (mother- and father ratings averaged): | |||||

| Total Optimism | 27.2 | (2.2) | 26.6 | (2.6) | 0.016 |

| Optimism subscale | 12.3 | (1.7) | 11.9 | (1.9) | 0.032 |

| Pessimism subscale | 5.1 | (1.1) | 5.2 | (1.1) | 0.332 |

| Self-Esteem (mother-, father-, and teacher-ratings averaged) | 50.0 | (4.3) | 47.6 | (5.2) | <0.001 |

| Social Competence (mother-, father-, and teacher-ratings averaged) | 46.7 | (4.9) | 43.1 | (5.9) | <0.001 |

| Sleep quantity and quality: | |||||

| Sleep duration (hour) | 8.5 | (0.6) | 8.3 | (0.7) | 0.001 |

| Sleep latency (minutes) | 18.1 | (9.8) | 20.2 | (11.4) | 0.064 |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 84.9 | (6.0) | 83.2 | (5.7) | 0.013 |

Table 1 also presents, for girls and boys separately, the means and standard deviations for parent-rated total optimism score, and optimism and pessimism subscale scores as well as parent- and teacher-rated self-esteem and social competence scores. On average, the girls were rated as more optimistic (P-values < 0.03) and higher in self-esteem and social competence than the boys (both P-values < 0.001); girls and boys did not differ in pessimism (P = 0.20).

Sleep quantity, quality, and positive characteristics

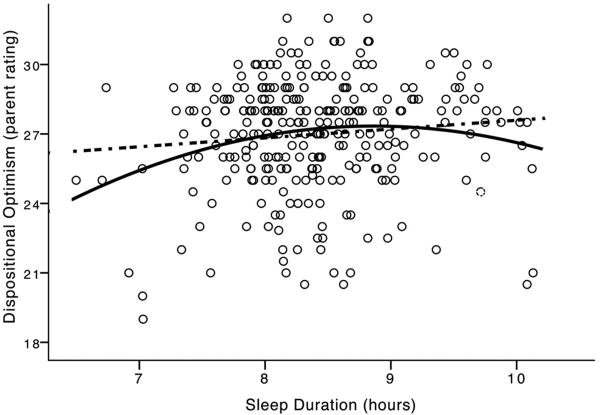

Table 2 shows that sleep duration had a non-linear relationship with parent-rated optimism (total optimism score: R2 change = 2.0%, P = 0.02; optimism subscale score: R2 change = 2.7%, P = 0.005). Children in the middle of the distribution of sleep duration were rated as more optimistic (Figure 1) than children in the shorter or longer ends of the distribution of sleep duration. Analyses of sleep duration as categorical revealed that children whose sleep duration was between the 10th and 90th percentiles of the distribution were more optimistic (total optimism score: R2 change = 2.3%, P = 0.01; optimism subscale score: R2 change = 2.6%, P = 0.009) than children whose sleep duration was short (below 10th percentile); average (10th – 90th percentiles) and long sleepers (above 90th percentile) did not differ significantly from each other (P-values > 0.16).

Table 2.

Associations of sleep quantity and quality with parent-rated optimism, and parent-, and teacher-rated self-esteem, and social competence of the child.

| Total Optimism | Optimism subscale | Pessimism subscale | Self-esteem | Social Competence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| Sleep quantity and quality: | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P |

|

|

||||||||||

| Sleep Duration | ||||||||||

| Linear effect | 0.08 | 0.161 | 0.08 | 0.206 | -0.06 | 0.309 | .04 | .515 | .06 | .309 |

| Non-linear effect | -0.15 | 0.015 | -0.17 | 0.005 | 0.04 | 0.469 | -.05 | .373 | -.10 | .096 |

| Average (7.7-9.3 hours) vs. | ||||||||||

| Short (≤ 7.6 hours) | -0.15 | 0.014 | -0.16 | 0.009 | 0.07 | 0.291 | -.05 | .444 | -.07 | .239 |

| Long (≥ 9.4 hours) | 0.04 | 0.537 | 0.00 | 0.977 | -0.09 | 0.166 | -.02 | .720 | -.04 | .478 |

| Sleep Latency | ||||||||||

| Linear effect | -0.15 | 0.010 | -0.13 | 0.024 | 0.12 | 0.044 | -.11 | .060 | .04 | .515 |

| Short-average (< 32 minutes) vs. | ||||||||||

| Long (> 32 minutes) | -0.08 | 0.179 | -0.05 | 0.356 | 0.08 | 0.162 | -.12 | .026 | -.03 | .620 |

| Sleep Efficiency | ||||||||||

| Linear effect | 0.07 | 0.265 | 0.07 | 0.226 | -0.03 | 0.603 | -.01 | .892 | -.01 | .809 |

| Average-high (> 77.4%) vs. | ||||||||||

| Low (< 77.4%) | -0.05 | 0.443 | -0.09 | 0.131 | -0.04 | 0.523 | .01 | .905 | .01 | .823 |

Note. Coefficients represent standardized regression coefficients derived from multiple linear regression analyses adjusted for child's sex, age, body mass index, and parental level of education.

Figure 1.

Non-linear relationship between sleep duration and parent-rated dispositional optimism (total score) of the child. Linear regression equation: y = 0.4b + 23.8; Non-linear regression equation: y = −0.6b2 + 9.8b – 16.0.

Table 2 also shows that sleep latency and parent-rated optimism (total optimism score: R2 change = 2.3%, P = 0.01; optimism subscale score: R2 change = 1.7%, P = 0.02) and pessimism (R2 change = 1.4%, P = 0.04), and combined parent- and teacher-rated self-esteem (R2 change = 1.1%, approaching statistical significance, P = 0.06) were linearly related, such that the shorter the sleep latency, the higher the child's optimism and self-esteem, and the lower the child's pessimism. Analyses of sleep latency as dichotomous revealed no significant differences between children with short to average and long sleep latency in optimism and social competence, while there was a difference in self-esteem: the children with a short to average sleep latency were higher in parent- and teacher-rated self-esteem (R2 change = 1.5%, P = 0.03). All the significant associations listed above were adjusted for child's age, sex, BMI, and highest education in the family. The significant associations between sleep and child optimism remained also when further controlling for maternal and paternal optimism (all P-values < 0.05).

Discussion

We examined if sufficient sleep quantity and good sleep quality are associated with optimism, self-esteem, and social competence in children. In accordance with our hypothesis, we found a non-linear relationship between sleep duration and optimism. The relation resembled a reverse J-shaped curve, such that children whose sleep duration was in the middle of the distribution scored higher on optimism compared to children who slept relatively little. Further, children with shorter sleep latency scored higher on optimism and tended to have higher scores on self-esteem. The associations remained when adjusting for child's age, sex, body mass index and parental level of education, factors that may increase risk for less optimal sleep pattern and/or for lower scores on positive characteristics. Additionally, the association of sleep with optimism did not change when the parents' ratings of their own optimism were controlled.

Our findings in the 8-year-old children are consistent with the previous epidemiological and experimental studies in adults (National Sleep Foundation, 2002; Haack & Mullington, 2005). The findings are, however, not in line with those by Fredriksen et al. (2004) who showed that adolescents who report sleeping longer scored higher on self-esteem. There are methodological differences in the measure of sleep duration, however, between the current and the Fredriksen et al. (2004) studies that may explain the differences. It is also worth noting that adolescence is a period when the biological need for sleep is altered (e.g., Iglowstein et al, 2003). Therefore, our findings in pre-pubertal children may not be directly compared with the findings in adolescents.

Our findings also parallel data in adults showing that physical and mental health may be better among those with average sleep duration compared to those with either short and/or long sleep duration (e.g., Ayas et al., 2003a; Ferrie et al., 2007; Kaneita et al., 2006) and among those with short sleep latency or without problems initiating sleep compared to those suffering from long sleep latency or insomnia (Paudel et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2007; Vgontzas & Kales, 1999). Data in adults and adolescents show that optimism and self-esteem are predictors of good physical and mental health in subsequent life. For instance, optimistic adults have lower ambulatory blood pressure levels (Räikkönen et al., 1999), and are less likely to develop signs of subclinical cardiovascular disease (Matthews et al., 2004), and are less likely to suffer from symptoms of depression (Bromberger & Matthews, 1996). Further, more optimistic adolescents report more positive and less negative affect, depression, hopelessness, suicidal ideation, and substance abuse (Ben-Zur, 2003; Carvajal et al., 1998; Chang & Sanna, 2003; Roberts et al., 1998). Higher self-esteem, in turn, is associated in adults, for instance, with better functional health (Reitzes & Mutran, 2006), lower stress-induced cardiovascular and inflammatory responses (O’Donnell et al., 2008), and lower risk of all-cause mortality (Stamatakis et al., 2004), and in adolescents with better psychological adjustment, better school adjustment, lower delinquency, and lower level of health symptoms (Aspinwall & Taylor, 1992, Donnellan et al., 2005; McGee & Williams, 2000; Orth, Robins, & Roberts, 2008, Trzesniewski et al., 2006). Thus, our findings suggest that sleep-associated positive characteristics may add to the explanation why a more optimal sleep pattern is associated with better physical and mental health.

The associations between the children's sleep duration and latency with optimism and/or self-esteem were, however, modest in effect size. In interpreting the effect sizes, one should keep in mind that we examined a generally healthy population of young children. The effect sizes are, however, comparable to, for instance, the size of the relation of sleep duration with BMI reported in some epidemiological studies in children. While it is well acknowledged that short sleep duration poses a risk for obesity in children/adolescents (Chen et al., 2008; Cappuccio et al., 2008), in some large-scale epidemiological studies the size of the cross-sectional relation between sleep duration and body mass index has been modest (Eisenmann et al. 2006; Snell et al. 2007) – comparable or even smaller than the effect sizes we report for the relation of sleep with optimism and self-esteem in this study. It should also be kept in mind that we cannot draw causal inferences from the cross-sectional findings of this study. Hence, it is possible that good sleep and positive characteristics are reciprocally related. In other words, good sleep, by promoting better physical and mental well-being, may result in a more positive psychological profile. Equally, it may be true that positive psychological characteristics, by promoting better physical and mental-well being, result in quantitatively and qualitatively better sleep. Further, the associations may also be determined by a common, but yet unknown, underlying factor, such as genetic variants for sleep-wake cycles. Thus, the underlying physical, genetic or psychological mechanisms linking sleep and positive characteristics have yet to be identified.

Apart from the cross-sectional study design and lack of data on the underlying mechanisms, a further limitation of our study relates to the generalizability of the findings. Sleep pattern changes with age and pubertal maturation (Iglowstein et al., 2003). Thus, our findings cannot be generalized to much younger or older age groups. Our sample was predominately Caucasian and none of the children suffered from severe physical or mental health problems. Our findings may not either generalize to samples with different ethnic backgrounds or with greater variance in health. Also, nearly half of the sample had rather well-educated parents with degrees beyond college. While we did not observe associations between parental level of education and sleep pattern, our findings may not generalize to less affluent populations.

Further, whereas sleep duration and sleep efficiency in children, measured with the chosen actigraph brand have shown high agreement with polysomnography (with agreement rate of 87.3, sensitivity of 93.9, and specificity of 59.0 with a medium activity threshold, Hyde et al., 2007), concerns have been raised about the reliability of sleep latency in children (Sitnick et al., 2008), which is highly dependent on the reliability of the bedtime reported in a sleep log. However, very rarely have sleep logs and event marker data been compared to assess the reliability of the reported bedtime. We were able to do this in our study, and found very high correspondence between the sleep log completed by the parents and the event markers in the actigraph data. Still, it has to be kept in mind that results involving sleep latency should be interpreted cautiously.

Although the actigraphy measurement may lack the accuracy provided by the polysomnography in measuring sleep quantity and quality in young children (Ohayon et al., 2004), actigraphy has the benefit of being ecologically valid in studying sleep patterns over many consecutive nights at the children's own beds at home (Acebo & LeBourgeois, 2006). A further strength to our study is that we did not rely on a single informant in measuring the children's positive characteristics, but both mothers and fathers rated their children's optimism, and mothers, fathers and teachers rated the children's self-esteem and social competence.

To aggregate, we found associations between objectively measured sleep pattern and positive psychological characteristics in 8-year-old children. Our results show that sufficient sleep quantity is associated with higher levels of optimism, and good sleep quality is associated with higher levels of optimism and self-esteem. Thus, our results further underscore the importance of sufficient sleep quantity and good sleep quality in promoting well-being in children.

Acknowledgments

Sponsored by grants from the Juho Vainio Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the European Science Foundation (EuroSTRESS), the Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation, the Finnish Medical Society Duodecim, the Finnish Foundation for Pediatric Research, the Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation, and the Academy of Finland. Preparation of the manuscript was supported by a grant for individual short visits of the Swiss National Science Foundation awarded to Sakari Lemola (grant IZKOZ1- 127779 /1) and by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH HL076852 and HL076858).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No author indicated any conflicts of interest

References

- Acebo C, Lebourgeois MK. Actigraphy. Respir Care Clin N Am. 2006;12:23–30. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.rcc.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist 4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aronen ET, Paavonen EJ, Fjallberg M, Soininen M, Torronen J. Sleep and psychiatric symptoms in school-age children. J Am Acad Child Psy. 2000;39:502–08. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall LG, Taylor SE. Modeling cognitive adaptation: A longitudinal investigation of the impact of individual differences and coping on college adjustment and performance. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:989–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayas NT, White DP, Al-Delaimy WK, et al. A prospective study of self-reported sleep duration and incident diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2003a;26:380–384. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayas NT, White DP, Manson JE, et al. A prospective study of sleep duration and coronary heart disease in women. Arch Intern Med. 2003b;163:205–209. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zur H. Happy adolescents: The link between subjective well-being, internal resources, and parental factors. J Youth Adolescence. 2003;32:67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet MH, Arand DL. We are chronically sleep deprived. Sleep. 1995;18:908–911. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.10.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberger JT, Matthews KA. A longitudinal study of the effects of pessimism, trait anxiety, and life stress on depressive symptoms in middle-aged women. Psychol Aging. 1996;11:207–213. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt KB, Obradović J, Long JD, Masten AS. The interplay of social competence and psychopathology over 20 years: Testing transactional and cascade models. Child Dev. 2008;79:359–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccio FP, Taggart FM, Kandala NB, et al. Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep. 2008;31:619–626. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.5.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal SC, Clair SD, Nash SG, Evans RI. Relating optimism, hope, and self-esteem to social influences in deterring substance use in adolescents. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1998;17:443–465. [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC, Sanna LJ. Optimism, accumulated life stress, and psychological and physical adjustment: Is it always adaptive to expect the best? J Soc Clin Psychol. 2003;22:97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Chang AM, Mackenzie AE. State self-esteem following stroke. Stroke. 1998;29:2325–2328. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.11.2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Beydoun MA, Wang Y. Is sleep duration associated with childhood obesity? A systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obesity. 2008;16:265–274. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Zion M, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a review of naturalistic and stimulant intervention studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8:379–402. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Trzesniewski KH, Robins RW, et al. Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior, and delinquency. Psychol Sci. 2005;16:328–335. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann JC, Ekkekakis P, Holmes M. Sleep duration overweight among Australian children adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:956–963. doi: 10.1080/08035250600731965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Buckhalt JA, Cummings EM, Keller P. Sleep disruptions and emotional insecurity are pathways of risk for children. J Child Psychol Psyc. 2007;48:88–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Cappuccio FP, et al. A prospective study of change in sleep duration: associations with mortality in the Whitehall II cohort. Sleep. 2007;30:1659–1666. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen K, Rhodes J, Reddy R, Way N. Sleepless in Chicago: Tracking the effects of adolescent sleep loss during the middle school years. Child Dev. 2004;75:84–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke-Oerkermann L, Pluck J, Schredl M, et al. Prevalence and course of sleep problems in childhood. Sleep. 2007;30:1371–1377. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.10.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs-Beauchamp KD. Preschoolers' inferred self-esteem: The behavioral rating scale of presented self-esteem in young children. J Genet Psychol. 1996;157:204–210. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1996.9914858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, et al. Sleep duration as a risk factor for diabetes incidence in a large U.S. sample Sleep. 2007;30:1667–1673. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, et al. Short sleep duration as a risk factor for hypertension: analyses of the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hypertension. 2006;47:833–839. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000217362.34748.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangwisch JE, Malaspina D, Boden-Albala B, Heymsfield SB. Inadequate sleep as a risk factor for obesity: analyses of the NHANES I. Sleep. 2005;28:1289–1296. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.10.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AM, Eley TC, O'Connor TG, Plomin R. Etiologies of Associations Between Childhood Sleep and Behavioral Problems in a Large Twin Sample. J Am Acad Child Psy. 2004;43:744–751. doi: 10.1097/01.chi/0000122798.47863.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AM, O’Connor TG. Sleep problems in childhood: a longitudinal study of developmental change and association with behavioral problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:964–971. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haack M, Mullington JM. Sustained sleep restriction reduces emotional and physical well-being. Pain. 2005;119:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltiwanger J, Harter S. Behavioral measure of young children's presented self-esteem. University of Denver; 1988. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Hasler G, Buysse DJ, Klaghofer R, et al. The association between short sleep duration and obesity in young adults: a 13-year prospective study. Sleep. 2004;27:661–666. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Eaves LJ, Kirk KM, Martin NG. Effects of lifestyle, personality, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and genetic predisposition on subjective sleep disturbance and sleep pattern. Twin Res. 1998;1:176–188. doi: 10.1375/136905298320566140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslop P, Smith GD, Metcalfe C, Macleod J, Hart C. Sleep duration and mortality: the effect of short or long sleep duration on cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in working men and women. Sleep Med. 2002;3:305–314. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(02)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hublin C, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J. Sleep and mortality: A population-based 22-Year follow-up study. Sleep. 2007;30:1245–1253. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.10.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde M, O'Driscoll DM, Binette S, et al. Validation of actigraphy for determining sleep and wake in children with sleep disordered breathing. J Sleep Res. 2007;16:213–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglowstein I, Jenni OG, Molinari L, Largo RH. Sleep Duration From Infancy to Adolescence: Reference Values and Generational Trends. Pediatrics. 2003;111:302–307. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanenko A, Crabtree VM, Obrien LM, Gozal D. Sleep complaints and psychiatric symptoms in children evaluated at a pediatric mental health clinic. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:42–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneita Y, Ohida T, Uchiyama M, et al. The relationship between depression and sleep disturbances: A Japanese nationwide general population survey. J Clin Psychiat. 2006;67:196–203. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson KL, Ryden AM, Mander BA, Van Cauter E. Role of sleep duration and quality in the risk and severity of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1768–1774. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.16.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima M, Wakai K, Kawamura T, et al. Sleep patterns and total mortality: a 12-year follow-up study in Japan. J Epidemiol. 2000;10:87–93. doi: 10.2188/jea.10.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2002;59:131–136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafreniere PJ, Dumas JE. Social competence and behavior evaluation in children ages 3 to 6 years: The short form (SCBE-30) Psychol Assessment. 1996;8:369–377. [Google Scholar]

- Lemola S, Räikkönen K, Matthews KA, et al. A new measure for dispositional optimism and pessimism in young children. Eur J Personality. 2009 e-pub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Liu L, Owens JA, Kaplan DL. Sleep patterns and sleep problems among schoolchildren in the United States and China. Pediatrics. 2005;115:241–249. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0815F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Räikkönen K, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Kuller LH. Optimistic attitudes protect against progression of carotid atherosclerosis in healthy middle-aged women. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:640–644. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000139999.99756.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee R, Williams S. Does low self-esteem predict health compromising behaviors among adolescents? J Adolescence. 2000;23:569–582. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer AM, Habekothe HT, Van Den Wittenboer GLH. Time in bed, quality of sleep and school functioning of children. J Sleep Res. 2000;9:145–153. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Sleep Foundation. Executive summary of the 2002 Sleep in America Poll. [Accessed on: November 14, 2008]; Available at: http://www.sleepfoundation.org/site/c.huIXKjM0IxF/b.2417355/k.143E/2002_Sleep_in_America_Poll.htm.

- Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MV. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep. 2004;27:1255–1273. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Robins RW, Roberts BW. Low self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in adolescence and young adulthood. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95:695–708. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Brydon L, Wright CE, Steptoe A. Self-esteem levels and cardiovascular and inflammatory responses to acute stress. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:1241–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paavonen EJ, Räikkönen K, Lahti J, et al. Short sleep duration and behavioral symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in healthy 7- to 8-year-old children. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e857–e864. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SR, Hu FB. Short Sleep Duration and Weight Gain: A Systematic Review. Obesity. 2008;16:643–653. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paudel ML, Taylor BC, Diem SJ, et al. Association between depressive symptoms and sleep disturbances among community-dwelling older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1228–1235. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesonen AK, Räikkönen K, Matthews K, et al. Prenatal origins of poor sleep in children. Sleep. 2009a;32:1086–1092. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.8.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesonen AK, Räikkönen K, Paavonen EJ, et al. Sleep Duration and Regularity are Associated with Behavioral Problems in 8-year-old Children. Int J Behav Med. 2009b doi: 10.1007/s12529-009-9065-1. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Räikkönen K, Matthews KA, D FJ, Owens JF, Gump BB. Effects of optimism, pessimism and trait anxiety on ambulatory blood pressure and mood during everyday life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76:104–113. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Räikkönen K, Pesonen AK, Heinonen K, et al. Maternal licorice consumption and detrimental cognitive and psychiatric outcomes in 8 –year-old children. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:1137–1146. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaratnam SMW, Arendt J. Health in a 24-h society. Lancet. 2000;358:999–1005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo AC, Muehlbach MJ, Schweitzer PK, Walsh JK. Cognitive function following acute sleep restriction in children ages 10-14. Sleep. 1998;21:861–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly J, Armstrong J, Dorosty A, et al. Early life risk factors for obesity in childhood: cohort study. Brit Med J. 2005;330:1357–1363. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38470.670903.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzes DC, Mutran EJ. Self and health: factors that encourage self-esteem and functional health. J Gerontol. 2006;61B:S44–S51. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.s44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen YR. Suicidal thinking among adolescents with a history of attempted suicide. J Am Acad Child Psy. 1998;37:1294–1300. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Bukowski W, Parker JG. Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development. Vol. 3. New York, NY, US: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1998. pp. 619–700. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Gruber R, Raviv A. Sleep, neurobehavioral functioning, and behavior problems in school-age children. Child Dev. 2002;73:405–417. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Hauri PJ, Kripke DF, Lavie P. The role of actigraphy in the evaluation of sleep disorders. Sleep. 1995;18:288–302. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.4.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sateia MJ, Doghramji K, Hauri PJ, Morin CM. Evaluation of Chronic Insomnia. Sleep. 2000;23:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognitive Ther Res. 1992;16:201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Self-regulatory processes and responses to health threats: Effects of optimism on well-being. In: Suls J, Wallston K, editors. Social psychological foundations of health. Oxford UK: Blackwell; 2003. pp. 395–428. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A re-evaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Matthews KA, Owens JF, et al. Optimism and rehospitalization after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:829–835. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.8.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitnick SL, Goodlin-Jones BL, Anders TF. The use of actigraphy to study sleep disorders in preschoolers: some concerns about detection of nighttime awakenings. Sleep. 2008;31:395–401. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.3.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaldone A, Honig JC, Byrne MW. Sleepless in America: indadequate sleep and relationships to health and well-being of our nation's children. Pediatrics. 2007;119:S29–S37. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snell EK, Adam EK, Duncan GJ. Sleep and the body mass index and overweight status of children and adolescents. Child Dev. 2007;78:309–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis KA, Lynch JW, Everson SA, Raghunathan TE, Salonen JT, Kaplan GA. Self-esteem and mortality: Prospective evidence from a population- based study. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14:58–65. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00078-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamakoshi A, Ohno Y. Self-reported sleep duration as a predictor of all-cause mortality: results from the JACC study, Japan. Sleep. 2004;27:51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DJ, Mallory LJ, Lichstein KL, et al. Comorbidity of chronic insomnia with medical problems. Sleep. 2007;30:213–218. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonetti L, Pasquini F, Fabbri M, Belluzzi M, Natale V. Comparison of two different actigraphs with polysomnography in healthy young subjects. Chronobiol Int. 2008;25:145–153. doi: 10.1080/07420520801897228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touchette E, Petit D, Seguin JR, Boivin M, Tremblay RE, Montplaisir JY. Associations between sleep duration patterns and behavioral/cognitive functioning at school entry. Sleep. 2007;30:1213–1219. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzesniewski KH, Donnellan MB, Moffitt TE, et al. Low self-esteem during adolescence predicts poor health, criminal behavior, and limited economic prospects during adulthood. Dev Psychol. 2006;42:381–390. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verschueren K, Buyck P, Marcoen A. Self-representations and socioemotional competence in young children: A 3-year longitudinal study. Dev Psychol. 2001;37:126–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verschueren K, Marcoen A, Buyck P. Five-year-olds' behaviorally presented self- esteem: relations to self-perceptions and stability across a three-year period. J Genet Psychol. 1998;159:273–79. doi: 10.1080/00221329809596151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vioque J, Torres A, Quiles J. Time spent watching television, sleep duration and obesity in adults living in Valencia, Spain. Int J Obesity. 2000;24:1683–1688. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vgontzas AN, Kales A. Sleep and its disorders. Annu Rev Med. 1999;50:387–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaggi HK, Araujo AB, McKinlay JB. Sleep duration as a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:657–661. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-0879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]