Abstract

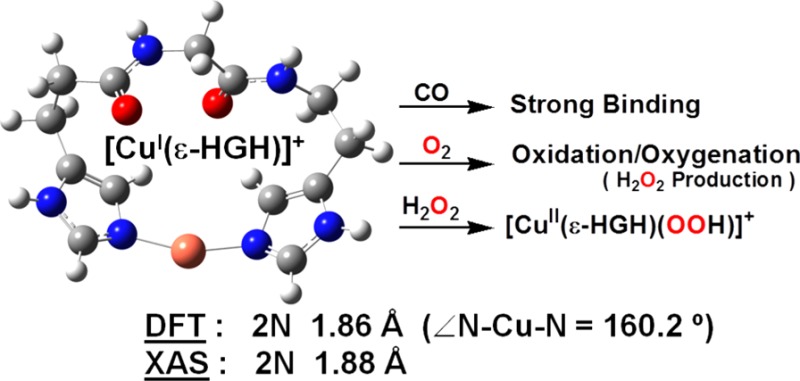

Oxygen-activating copper proteins may possess His-Xaa-His chelating sequences at their active sites and additionally exhibit imidiazole group δN vs εN tautomeric preferences. As shown here, such variations strongly affect copper ion’s coordination geometry, redox behavior, and oxidative reactivity. Copper(I) complexes bound to either δ-HGH or ε-HGH tripeptides were synthesized and characterized. Structural investigations using X-ray absorption spectroscopy, density functional theory calculations, and solution conductivity measurements reveal that δ-HGH forms the CuI dimer complex [{CuI(δ-HGH)}2]2+ (1) while ε-HGH binds CuI to give the monomeric complex [CuI(ε-HGH)]+ (2). Only 2 exhibits any reactivity, forming a strong CO adduct, [CuI(ε-HGH)(CO)]+, with properties closely matching those of the copper monooxygenase PHM. Also, 2 is reactive toward O2 or H2O2, giving a new type of O2-adduct or CuII–OOH complex, respectively.

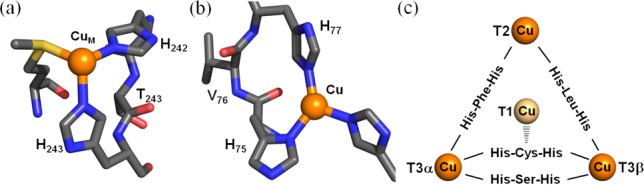

The study of peptide complexation to copper ions has been of great interest to (bio)chemists since the most common ligands at copper active sites in proteins are amino acids, most often histidine.1 A survey of His imidazole group binding to copper proteins involved in redox chemistry, including O2 reactivity, indicates that the His-Xaa-His (Xaa = amino acid) tripeptide motif is a frequently observed sequence, including, for example, His-Thr-His in PHM2,3 and DβM,4 His-Val-His in SOD55 and pMMO,6 and His-Gln-His in APLP2 and LYOX.7 Four highly conserved His-Xaa-His sequences exist in a bridging fashion in the trinuclear copper ion cluster of MCOs (Figure 1).8 Also, a similar motif appears in pentapeptide domains (HLHWH) present in the amyloid precursor protein (APP) associated with the development of Alzheimer’s disease.7,9

Figure 1.

His-Xaa-His sequences present in the copper active site of (a) PHM (PDB entry 1SDW),3 (b) SOD5 (4N3T),5 and (c) MCO (1ZPU).8

The imidazole group of histidine ligands can bind to Cu ion through either the δN or εN site, and tautomeric preferences occur in different classes of copper proteins.10 The variations most certainly are critical in determining the functions and properties of the enzymes because of differences in decisive steric/electronic effects imparted to the copper ion center, for example controlling the exact nature of O2 binding and consequent structure–reactivity and the specificity of substrate approach. For example, in PHM, O2 binds at the CuM site, which is close to where the substrate docks; CuM is ligated by two εN sites of His’s in an HTH sequence. CuH, which is ∼11 Å away, facilitates electron transfer, but it binds to three δNHis sites (in fact where two of the His residues are adjacent in the overall peptide sequence).3 These observations raise basic questions relevant to PHM active-site structure and function: how do these specific tautomeric imidazole N atom configurations imposed by nature control (i) copper coordination number and geometry, (ii) CuII/CuI redox potential, (iii) electronic structure/bonding and associated spectroscopic properties, and (iv) exogenous ligand preferences?

We have previously reported studies of CuI complexes of modified histidylhistidine (HisHis) peptides11 where imidazole N atoms were specifically blocked, allowing study of δ-HH (δN of both H’s available for metal coordination) or ε-HH (εN of both H’s available for metal coordination). Significantly, both dipeptides adopt a linear two-coordinate NHis–CuI–NHis environment. In the present work, we aimed to understand why the unique His-Xaa-His sequence is particularly “selected” in nature by generating CuI complexes of His-Gly-His tripeptides1h with varying δN versus εN atom availability and investigating their structural features and chemical properties.

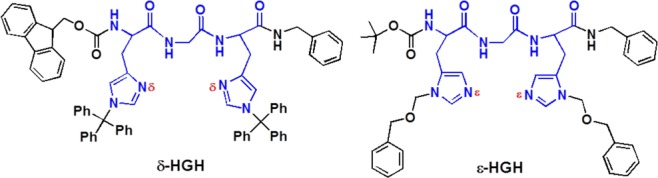

The tripeptides δ-HGH and ε-HGH (Chart 1) were synthesized by modifications of literature procedures and standard solution-phase peptide synthesis techniques.12 The N-/C-tripeptide terminal groups were also “protected” using either fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc), tert-butyloxycarbonyl (Boc), or benzyl groups to avoid any likelihood of terminal-group Cu coordination.13 δ-HGH and ε-HGH were metalated with [CuI(CH3CN)4]ClO4 in CH2Cl2. Solid complexes were isolated by precipitation and purified by recrystallization from CH2Cl2/Et2O; their elemental analysis and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry envelope isotope patterns were consistent with the [ligand–CuI]+ cation formulations.14

Chart 1.

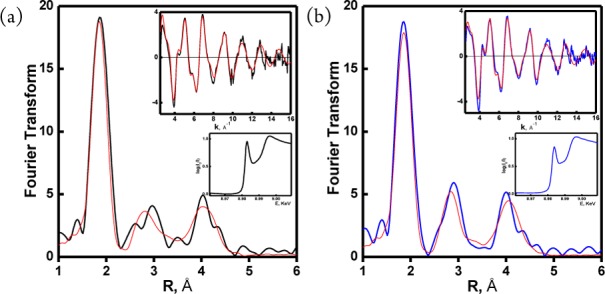

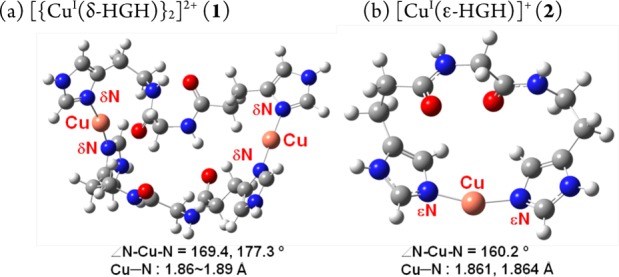

Extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy (Figure 2)14 of LCuI complex solids and accompanying computational analyses (Figure 3)14 provide strong evidence that CuI complexes of both δ-HGH and ε-HGH possess two-coordinate NHis–CuI–NHis geometries. Multiple scattering definitively reveals the patterns known for NHis–Cu coordination. For the CuI complex of δ-HGH, the data given in Figure 2a display the best fit to two δNHis-ligand scatterers with Cu–N = 1.867 Å, indicative of linear two-coordinate CuI, as observed earlier with the HisHis peptides.11 These very short CuI–N bonds are characteristic of this very low coordination, being significantly shorter than those found in three-coordinate CuI–N3 compounds.15

Figure 2.

EXAFS and XANES spectroscopic data for (a) [{CuI(δ-HGH)}2]2+ (1) [data (black), fit (red)] and (b) [CuI(ε-HGH)]+ (2) [data (blue), fit (red)]. Overlapped spectra for comparison are shown in the Supporting Information.

Figure 3.

DFT-optimized geometries (RB3LYP/6-311G**) for (a) dimer 1 and (b) mononuclear 2 (∠εN–Cu−εN = 160.2°). The calculations were carried out with the protecting groups on the non-copper-coordinating NHis atom and N-/C-termini replaced with H atoms.14

The EXAFS data for the solid complex of CuI with ε-HGH are extremely similar. The best and only fit was found with two-His ligation (Figure 2b)14 and a CuI–NHis bond length of 1.878 Å, also indicating two-coordinate CuI. The only significant difference is a small decrease in the intensity of the 8983 eV pre-edge transition found in the X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectroscopic data, which may suggest some deviation from a strictly linear geometry.11,16 As described below, this deviation seems to directly relate to this CuI compound’s remarkably different (compared with the δ-HGH CuI complex) electrochemical and CO-binding behavior and its reactivity toward O2 and H2O2.

Density functional theory (DFT) structural analyses and supporting solution conductivity measurements lead to differing formulations for δ-HGH and ε-HGH in comparison with our previous findings for HisHis dipeptides. The EXAFS data indicate near-perfect linear two-coordination for CuI in the δ-HGH complex. Solution conductivity data in dimethylformamide (DMF) provide an Onsager plot for a CuI–δ-HGH complex with a slope in the range expected for 2:1 electrolyte behavior, thus indicating a dimer formulation, [{CuI(δ-HGH)}2]2+ (1). We note that Figure 3a is a geometry optimization assuming a dimer formulation. In fact, higher-level computations and energy comparisons (in vacuum) reveal that a monomeric formulation and structure are slightly favored (by 11.5 kJ/mol).14 The stronger solution experimental evidence thus points to the dimer formulation; apparently, intramolecular two-coordination leads to an excessively strained structure. By contrast, structural energy minimization for a CuI–ε-HGH complex leads to a preferred mononuclear formulation, [CuI(ε-HGH)]+ (2) (Figure 3b), on the basis of electronic energies corrected for zero-point energy; a dimer structure as in 1 is thermodynamically disfavored by 44.0 kJ/mol. Also, a dimer is ruled out by solution conductivity measurements showing that this complex behaves as a 1:1 electrolyte.14,17 Notably, the DFT-derived structure for complex 2 reveals a significant bending in the two-coordinate CuI coordination, with ∠N–CuI–N = 160.2°, as suggested by the XANES data and the unexpected oxidative reactivity (vide infra); nevertheless, short CuI–NIm bond distances are present that are typical of this coordination number for CuI and much shorter than those observed in three-coordinate CuI–N3 compounds (vide supra).

The features observed here for CuI binding to His-Xaa-His peptides contrast greatly with those observed for the previously studied HisHis peptides,11 where the [CuI(δ-HH)]+ complex showed monomeric behavior (DFT and solution conductivity) while [CuI(ε-HH)]+ is a 2:1 solution electrolyte with a dimeric structure. Just inserting a Gly amino acid between two His residues leads to significant changes in the Cu coordination environment. Do these alterations affect other physical/spectroscopic properties or reactivity patterns?

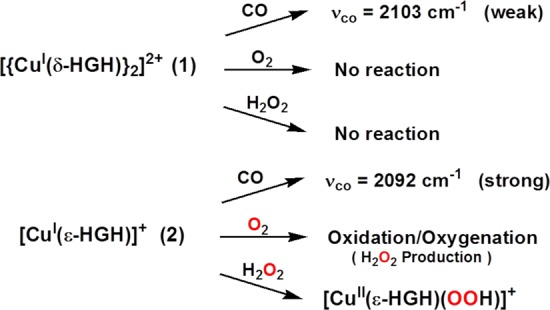

To address such questions, we first examined the CO binding behavior of the new CuI–peptide complexes, as CO is a CuI-specific ligand (and more generally an O2 surrogate) and can provide insights into coordination number and ligand donation ability. CO adducts of acetone solutions (under Ar) of 1 and 2 were generated by direct CO bubbling. As previously established for near-linear two-coordinate [CuI(HisHis)]+ complexes, CO binding is very weak, and high-frequency stretching vibrations (νCO = 2110–2112 cm–1) of low intensity are observed.11b,15c,18 This is also the case here, as the IR spectrum of 1–CO exhibits νCO = 2103 cm–1 (Table 1). By contrast, [CuI(ε-HGH)(CO)]+ (2–CO) displays a high-intensity absorption at lower frequency (νCO = 2092 cm–1).14 This observation suggests that there is a significant geometric-coordinative effect leading to stronger ligation of CO to CuI and better back-donation from CuI when it is bound to the ε-HGH ligand rather than to either the δ-HGH or HisHis system (Table 1). This νCO of 2092 cm–1 for 2–CO in fact compares very well with that observed for the enzyme CuM sites in PHM (2093 cm–1)19 and DβM (2089 cm–1),20 which are ligated by two histidyl εN atoms of the His-Thr-His active-site tripeptide sequence (Figure 1a). Thus, 2–CO possesses a chemical environment reasonably mimicking that of the protein active sites.

Table 1. Comparison of Properties of CuI–Peptide Complexes.

| complexa | Cu–NHis (Å)b | νCO (cm–1)c | redox behavior | O2 /H2O2 reactivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [{CuI(δ-HGH)}2]2+ | 1.867 | 2103 | irreversible | no |

| [CuI(ε-HGH)]+ | 1.878 | 2092 | quasi-reversible | yes |

| [CuI(δ-HH)]+ | 1.876 | 2110 | irreversible | no |

| [{CuI(ε-HH)}2]2+ | 1.863 | 2112 | irreversible | no |

Determined by solution conductivity.

Measured by XAS.

IR stretching frequency.

Cyclic voltammetry measurements were performed on 1 and 2 in DMF under argon to probe their electrochemical properties. Complex 1 displays irreversible redox behavior (Table 1),14 as expected for a two-coordinate CuI species; the same was shown previously for analogous complexes formed from HisHis ligand systems.11b On the other hand, 2 shows quasi-reversible redox behavior (E1/2 ≈ −390 mV vs Fc+/Fc).14 Such chemical effects derived from tautomeric preferences for binding of CuI to these HGH tripeptides were further clarified by studies of oxidative reactivity (vide infra).

Complex 1 is unreactive toward O2 as a solid or in solution below 0 °C [with only extremely slow oxidation and color change occurring at room temperature (RT)].21 This behavior is analogous to that observed for linear two-coordinate CuI complexes studied previously.11b,15a−15c In the context of other works, as an exception (i.e., the only case where we observe facile reactivity with O2), the reaction of 2 with O2 in acetone results in the formation of a metastable complex at −80 °C that exhibits absorptions at 336 nm (ε = 1110 M–1 cm–1) and 606 nm (ε = 110 M–1 cm–1).14 Frozen-solution electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) measurements were silent, indicating that whatever species is present is diamagnetic but that warming to RT results in the formation of a paramagnetic mononuclear species. The low-temperature UV–vis absorptions are not characteristic of any well-known O2–CuI adduct, such as a superoxo–CuII, peroxo–dicopper(II) (μ-1,2 or μ-η2:η2), or bis(μ-oxo)dicopper(III) complex.22 Also, warming the intermediate to RT and testing for peroxide using iodometric titrations gave a 100% yield of H2O2 based on a stoichiometry of two molar equiv of 2 per H2O2.14 This suggests that the reaction of 2 with O2 leads to a peroxide-level species (i.e., two-electron reduction of O2) but with unusual UV–vis features (see above). Further detailed studies are warranted. Following Na2EDTA/H2O/CH2Cl2 demetalation procedures,23 the organic product was identified as unreacted starting ligand. Therefore, whatever CuIn–O2 (n = 1, 2, ...) adduct forms at low temperature does not affect any ligand oxidation/oxygenation chemistry, as is sometimes observed.

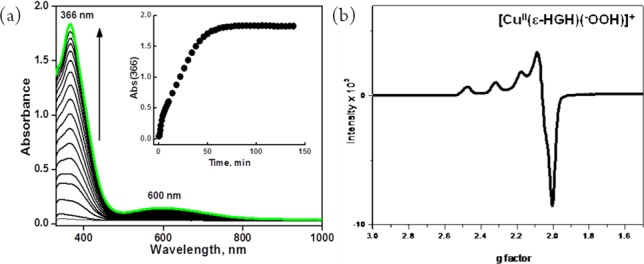

As CuII–hydroperoxo complexes are of interest as basic entities derived from CuI/O2 reactions and have been discussed in the realm of possible enzyme active intermediates capable of substrate oxidative behavior, we sought to study the present copper–peptide complexes. 1 is in fact unreactive toward H2O2, a remarkable observation that further demonstrates the extreme stability of CuI in a linear two-coordinate nitrogen ligand environment. However, we could generate a green-colored species (presumed to possess a [CuII(ε-HGH)(OOH)]+ formulation) in acetone at −80 °C by (i) addition of H2O2 (10 equiv)/Et3N to a mononuclear CuII derivative of ε-HGH, the newly synthesized cupric complex [CuII(ε-HGH)(H2O)](ClO4)2,14 or (ii) the reaction of 2 with 1.5 equiv of H2O2 (Figure 4a), a recently reported procedure for generating CuII–OOH species.24 [CuII(ε-HGH)(OOH)](ClO4) is presently characterized by (i) its UV–vis features [λmax = 366 nm (ε = 2600 M–1 cm–1), assignable to a −OOH → CuII ligand-to-metal charge transfer absorption on the basis of the correspondence with a number of literature examples,24,25 and λmax = 600 nm (ε = 200 M–1 cm–1), a d–d transition band] and (ii) its distinctive mononuclear-type axial EPR spectrum at 77 K (g∥ = 2.25, g⊥ = 2.05, A∥ = 192 G, A⊥ = 15 G; Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

(a) UV–vis spectra of [CuII(ε-HGH)(OOH)]+ generated by addition of 1.5 equiv of H2O2 to a 3.5 mM solution of 2 in acetone at 193 K. (b) EPR spectrum of [CuII(ε-HGH)(OOH)]+ at 77 K (g∥ = 2.25, g⊥ = 2.05, A∥ = 192 G, A⊥ = 15 G).

In conclusion, we have generated new CuI complexes with His-Gly-His tripeptides to probe fundamental aspects of CuI chemistry with this particular histidine-containing sequence; we have also probed the presence of synthetically imposed tautomeric preferences (δNIm vs εNIm availability) for CuI. The dimer [{CuI(δ-HGH)}2]2+ (1) exhibits favorable near-linear twofold coordination via intermolecular Cu−δNHis binding. This complex is not redox-active and only weakly binds CO. Furthermore, it does not react with either O2 or H2O2 (Scheme 1). However, [CuI(ε-HGH)]+ (2) shows two-His ligation with deviation from linearity. The similarity of our synthetic construct to the protein is notable: the IR spectrum of the carbonyl adduct 2–CO matches that observed for the enzyme PHM CuM–CO adduct with its active-site εH-Xaa-εH chelating moiety. Also, 2 displays redox activity and readily reacts with O2 and H2O2 to afford the first oxygen-intermediate species to be noted with CuI ligated to biologically relevant His-containing peptides.

Scheme 1.

It is striking that a switch in the imidazole tautomer can radically influence the reactivity of a CuI center. These results, in conjunction with our previous work with CuI-HisHis complexes,11 highlight the manner in which nature exerts its control of function. Even slight changes (dipeptide vs tripeptide; δNIm vs εNIm availability) can significantly affect an enzyme metal center’s structure and reactivity. Thus, our continuing research will add to an understanding of structure–function relationships in copper enzymes and the role of His binding motifs in facilitating Cu–O2 (and even reactive oxygen species) intermediate formation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support of this research from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM28962 to K.D.K. and R01 NS027583 to N.J.B.).

Supporting Information Available

Synthetic and analytical details; UV–vis, IR, and EPR spectra; cyclic voltammograms; and Onsager plots. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- a Sigel H.; Martin R. B. Chem. Rev. 1982, 82, 385. [Google Scholar]; b Daugherty R. G.; Wasowicz T.; Gibney B. R.; DeRose V. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 41, 2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Deschamps P.; Kulkarni P. P.; Gautam-Basak M.; Sarkar B. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005, 249, 895. [Google Scholar]; d Kozlowski H.; Kowalik-Jankowska T.; Jezowska-Bojczuk M. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005, 249, 2323. [Google Scholar]; e Rockcliffe D. A.; Cammers A.; Murali A.; Russell W. K.; DeRose V. J. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Shimazaki Y.; Takani M.; Yamauchi O. Dalton Trans. 2009, 7854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Tay W. M.; Hanafy A. I.; Angerhofer A.; Ming L.-J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 6709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Timari S.; Kallay C.; Osz K.; Sovago I.; Varnagy K. Dalton Trans. 2009, 1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbreviations: PHM = peptidylglycine α-hydroxylating monooxygenase; DβM = dopamine β-monooxygenase; SOD5 = superoxide dismutase; pMMO = particulate methane monooxygenase; APLP2 = Aβ precursor-like protein 2; LYOX = lysyl oxidase; MCO = multicopper oxidase.

- Prigge S. T.; Kolhekar A.; Eipper B. A.; Mains R. E.; Amzel M. Science 1997, 278, 1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigge S. T.; Mains R. E.; Eipper B. A.; Amzel L. M. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2000, 57, 1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason J. E.; Galaleldeen A.; Peterson R. L.; Taylor A. B.; Holloway S. P.; Waninger-Saroni J.; Cormack B. P.; Cabelli D. E.; Hart P. J.; Culotta V. C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111, 5866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman R. L.; Rosenzweig A. C. Nature 2005, 434, 177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse L.; Beher D.; Masters C. L.; Multhaup G. FEBS Lett. 1994, 349, 109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A. B.; Stoj C. S.; Ziegler L.; Kosman D. J.; Hart P. J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005, 102, 15459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. R. Dalton Trans. 2009, 4069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Karlin K. D.; Zhu Z.-Y.; Karlin S. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1998, 3, 172. [Google Scholar]; b Karlin S.; Zhu Z.-Y.; Karlin K. D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997, 94, 14225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Himes R. A.; Park G. Y.; Sutha Siluvai G. S.; Blackburn N. J.; Karlin K. D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 9084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Himes R. A.; Park G. Y.; Barry A. N.; Blackburn N. J.; Karlin K. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 5352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kovalainen J. T.; Christiaans J. A. M.; Kotisaari S.; Laitinen J. T.; Mannisto P. T.; Tuomisto L.; Gynther J. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Harding S. J.; Jones J. H.; Sabirov A. N.; Samukov V. V. J. Pept. Sci. 1999, 5, 368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Jones J. H.; Rathbone D. L.; Wyatt P. B. Synthesis 1987, 1110. [Google Scholar]

- a Isidro-Llobet A.; Alvarez M.; Albericio F. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b A reviewer asked about our choice of blocking groups, e.g., the use of Fmoc and trityl for blocking εN imidazole positions in the δ peptide. Fmoc was preferred over Boc and trityl was preferred over benzyl because Boc and benzyl protection was more expensive, gave lower yields in synthesis, and afforded final peptides exhibiting poor solubility in organic solvents. Examination of molecular models indicated that the nature of the protecting group should not influence CuI binding

- See the Supporting Information.

- a Sanyal I.; Strange R. R.; Blackburn N. J.; Karlin K. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 4692. [Google Scholar]; b Sanyal I.; Karlin K. D.; Strange R. W.; Blackburn N. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 11259. [Google Scholar]; c Sorrell T. N.; Jameson D. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 6013. [Google Scholar]; d Tan G. O.; Hodgson K. O.; Hedman B.; Clark G. R.; Garrity M. L.; Sorrell T. N. Acta Crystallogr. 1990, C46, 1773. [Google Scholar]; e Okkersen H.; Groeneve W.; Reedijk J. Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas 1973, 92, 945. [Google Scholar]; f Lewin A. H.; Cohen I. A.; Michl R. J. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1974, 36, 1951. [Google Scholar]; g Agnus Y.; Louis R.; Weiss R. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1980, 867. [Google Scholar]; h Engelhardt L. M.; Pakawatchai C.; White A. H.; Healy P. C. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1985, 117. [Google Scholar]; i Munakata M.; Kitagawa S.; Shimono H.; Masuda H. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1989, 158, 217. [Google Scholar]; j Habiyakare A.; Lucken E. A. C.; Bernardinelli G. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1991, 2269. [Google Scholar]

- a Kau L.-S.; Spira-Solomon A. J.; Penner-Hahn J. E.; Hodgson K. O.; Solomon E. I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 6433. [Google Scholar]; b Blackburn N. J.; Strange R. W.; Reedijk J.; Volbeda A.; Farooq A.; Karlin K. D.; Zubieta J. Inorg. Chem. 1989, 28, 1349. [Google Scholar]

- Geary W. J. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1971, 7, 81. [Google Scholar]

- a Voo J. K.; Lam K. C.; Rheingold A. L.; Riordan C. G. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 2001, 1803. [Google Scholar]; b Casella L.; Gullotti M.; Pallanza G.; Ligoni L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 4221. [Google Scholar]; c Pasquali M.; Floriani C.; Chiesivilla A.; Guastini C. Inorg. Chem. 1980, 19, 3847. [Google Scholar]; d Chou C. C.; Su C. C.; Yeh A. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 6122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaron S.; Blackburn N. J. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 15086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn N. J.; Pettingill T. M.; Seagraves K. S.; Shigeta R. T. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 15383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essentially all CuI complexes with nitrogenous ligands oxidize to CuII forms in an aerobic environment over hours or days or longer. Under such conditions, the complexes formed are not O2 adducts and are not relevant to the chemistry of species formed in fast reactions.

- a Mirica L. M.; Ottenwaelder X.; Stack T. D. P. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lewis E. A.; Tolman W. B. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hatcher L. Q.; Karlin K. D. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 9, 669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiti D.; Narducci Sarjeant A. A.; Karlin K. D. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 8736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.; Saracini C.; Siegler M. A.; Drichko N.; Karlin K. D. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wada A.; Harata M.; Hasegawa K.; Jitsukawa K.; Masuda H.; Mukai M.; Kitagawa T.; Einaga H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yamaguchi S.; Wada A.; Nagatomo S.; Kitagawa T.; Jitsukawa K.; Masuda H. Chem. Lett. 2004, 33, 1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Mizuno M.; Honda K.; Cho J.; Furutachi H.; Tosha T.; Matsumoto T.; Fujinami S.; Kitagawa T.; Suzuki M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 6911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Maiti D.; Narducci Sarjeant A. A.; Karlin K. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 6720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Yamaguchi S.; Nagatomo S.; Kitagawa T.; Funahashi Y.; Ozawa T.; Jitsukawa K.; Masuda H. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 6968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Yamaguchi S.; Masuda H. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2005, 6, 34. [Google Scholar]; g Fujii T.; Naito A.; Yamaguchi S.; Wada A.; Funahashi Y.; Jitsukawa K.; Nagatomo S.; Kitagawa T.; Masuda H. Chem. Commun. 2003, 2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.