Abstract

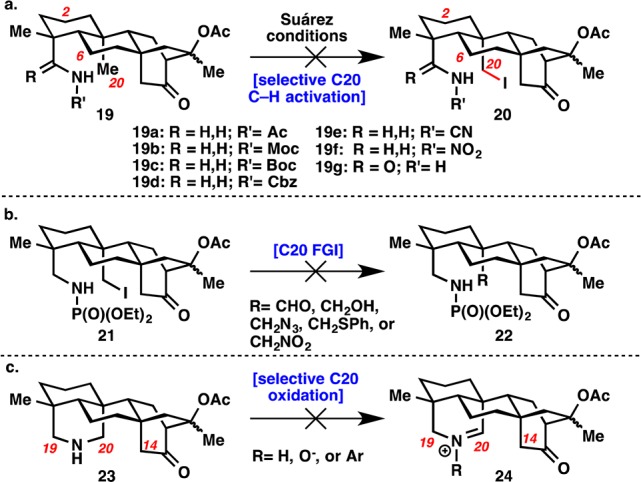

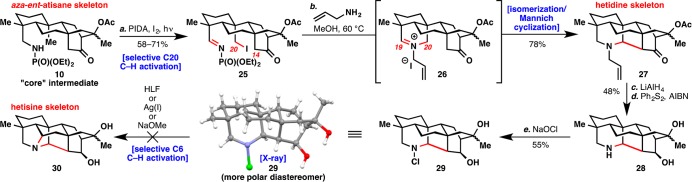

A unified approach to ent-atisane diterpenes and related atisine and hetidine alkaloids has been developed from ent-kaurane (−)-steviol (1). The conversion of the ent-kaurane skeleton to the ent-atisane skeleton features a Mukaiyama peroxygenation with concomitant cleavage of the C13–C16 bond. Conversion to the atisine skeleton (9) features a C20-selective C–H activation using a Suárez modification of the Hofmann–Löffler–Freytag (HLF) reaction. A cascade sequence involving azomethine ylide isomerization followed by Mannich cyclization forms the C14–C20 bond in the hetidine skeleton (8). Finally, attempts to form the N–C6 bond of the hetisine skeleton (7) with a late-stage HLF reaction are discussed. The synthesis of these skeletons has enabled the completion of (−)-methyl atisenoate (3) and (−)-isoatisine (4).

The ent-atisane diterpenes and related diterpenoid-alkaloids have attracted attention from the synthetic community for several decades.1 Synthetic efforts toward ent-atisane, atisine, hetidine, and hetisine natural products have culminated in syntheses of (−)-methyl atisenoate (3) (Figure 1a),2a−2c atisine,2d−2i azitine,2j dihydronavirine,2k,2l and nominine.2m−2o While successful pursuits to convert the hetidine skeleton into the hetisine skeleton have been reported,3 a unifying approach to the ent-atisane skeleton and related alkaloids (e.g., natural products 4–6) remains to be realized.

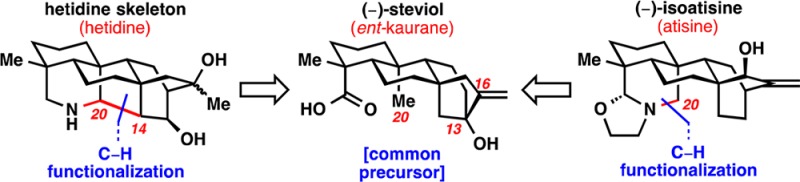

Figure 1.

(a) Representative members of each natural product family targeted. (b) Unified retrosynthetic strategy from (−)-steviol (1).

Our laboratory has applied a two-phase synthetic approach to access eudesmane, ingenane, and taxane natural products.4 Given our interest in this synthetic strategy, application to diterpenoid-alkaloids was envisioned. Building upon the previously reported syntheses of ent-kaurane steviol (1) and ent-beyerane isosteviol (2),5 a unified approach facilitated by a C–H functionalization6 strategy would access not only ent-atisanes but also related alkaloids (atisines, hetidines, and hetisines). Unified access to the ent-atisane, atisine, and hetidine skeletons (8–10, Figure 1b) and the syntheses of (−)-methyl atisenoate (3) and (−)-isoatisine (4) are disclosed.

Retrosynthetically, the N–C6 bond present in the heptacyclic hetisine skeleton (7) would be broken to give rise to the hetidine skeleton (8; Figure 1b). In the forward sense, a Hofmann–Löffler–Freytag (HLF) reaction could be used to install the N–C6 bond.7 Breaking the C14–C20 bond in 8 with a Mannich disconnection would lead back to atisine skeleton 9. Atisine skeleton 9 contains a N–C20 bond that would be installed with a Suárez modification of the HLF reaction on substrate 10.8 “Core” intermediate 10 would serve as a common precursor for all three of the alkaloid skeletons. This aza-atisane skeleton (10) would be derived from steviol (1), which could be obtained in decagram quantities from commercially available stevioside 11.9 Additionally, a non-nitrogen containing ent-atisane skeleton would be targeted to access (−)-methyl atisenoate (3). The ultimate goal of this endeavor would be to convert skeletons 7–9 into natural products 4–6.

The ent-atisanes were targeted first: beginning from (−)-steviol (1), conversion to the methyl ester followed by treatment with Mukaiyama’s conditions10a led directly to diketone 12 (Scheme 1a). This diketone likely arises from the fragmentation of the C13–C16 bond via an intermediate α-peroxy alcohol.10b An aldol cyclization catalyzed with Amberlyst 15 gave the bicyclo[2.2.2]octane system in the ent-atisanes as an inconsequential mixture of alcohol epimers. Treatment with Martin’s sulfurane gave exo-olefin 13 in good selectivity. Other conditions for the elimination (acids, Burgess’ reagent, SOCl2) gave inferior exo/endo ratios. Wolff–Kishner reduction of the ketone, followed by re-esterification, gave (−)-methyl atisenoate (3) in six steps from (−)-steviol (1).

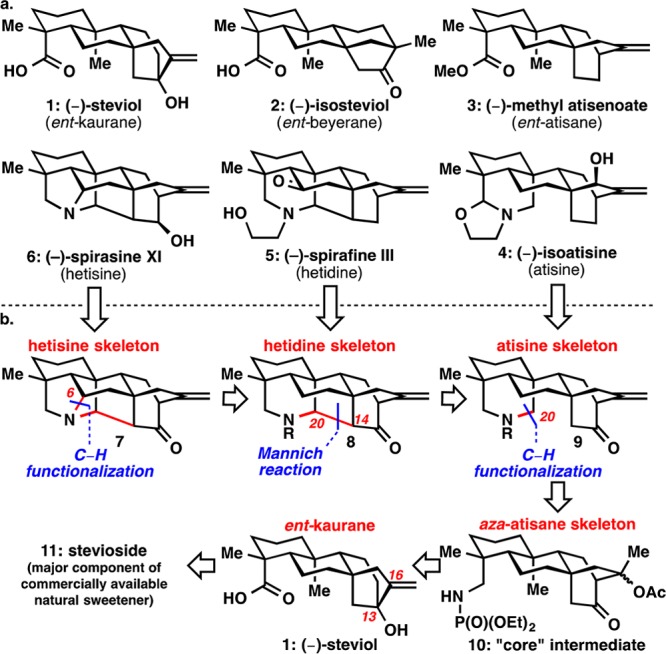

Scheme 1. Synthesis of (−)-Methyl Atisenoate (3) and (−)-Isoatisine (4).

Reagents and conditions: (a) Methyl iodide (1.2 equiv), TBAF (1.2 equiv), THF, 23 °C, 16 h (91%); (b) TESH (2.2 equiv), Co(acac)2 (0.2 equiv), O2 (balloon), DCE, 40 °C, 6 h (75%); (c) Amberlyst 15 resin (0.5 mg/mg substrate), acetone, 40 °C, 3 h (98%); (d) Martin’s sulfurane (2 equiv), CH2Cl2, −78 °C to room temp. (91%); (e) H2NNH2 (20 equiv), diethylene glycol, 100 °C, 90 min; KOH (5 equiv), 200 °C, 21 h (73%); (f) MeI (1.5 equiv), TBAF (1.5 equiv), THF, 23 °C, 3 h (85%); (g) HOBt·H2O (1.4 equiv), EDCI·HCl (2.8 equiv), NH4OH, THF, 23 °C, 36 h (80%); (h) LiAlH4 (5 equiv), THF, 70 °C, 48 h, (94%); (i) (iPr)2NEt (6 equiv), P(O)(OEt)2Cl (3 equiv), ACN, 60 °C, 16 h (93%); (j) TESH (2.2 equiv), Co(acac)2 (0.2 equiv), O2 (balloon), DCE, 40 °C, 16 h (59%); (k) Amberlyst 15 resin (0.5 mg/mg substrate), acetone, 40 °C, 3 h (87%); (l) Ac2O (5 equiv), DMAP (1 equiv), CHCl3/Et3N (1:1), 40 °C, 16 h (90%); (m) NaBH4 (3 equiv), MeOH, 0 to 23 °C; (n) TCDI (4 equiv), DCE, 80 °C, 18 h; (o) (TMS)3SiH (10 equiv), AIBN (0.5 equiv), dioxane, 80 °C (40% over 3 steps); (p) PIDA (4 equiv), I2 (5 equiv), DCE, 90-W sunlamp, 40 °C, 40 min; K2CO3 (25 equiv), MeOH, 65 °C, 36 h (71%); (q) Martin’s sulfurane (2 equiv), CH2Cl2, −78 to 23 °C; (r) SeO2 (4 equiv), tBuOOH (30 equiv), CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 1 h (63%, 2 steps), (s) ethanolamine (3 equiv), MeOH, 23 °C (89%). THF = tetrahydrofuran, TBAF = tetra-n-butyl ammonium fluoride, TESH = triethylsilane, DCE = 1,2-dichloroethane, HOBt = hydroxybenzotriazole, EDCI = 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)carbodiimide, ACN = acetonitrile, DMAP = 4-dimethylaminopyridine, TCDI = 1,1′-thiocarbonyldiimidazole, AIBN = azobis(isobutyronitrile), PIDA = phenyliodine diacetate.

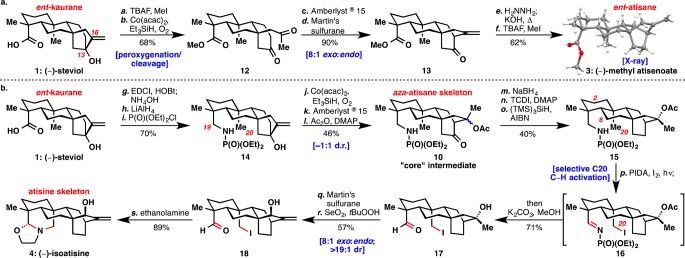

Pursuit of the atisines also started from (−)-steviol (1). Nitrogen was introduced at C19 with an amide bond formation (Scheme 1b). Reduction and then treatment of the resulting primary amine with diethyl chlorophosphate led to phosphoramidate 14, the necessary directing group for C20 C–H activation. A variety of other directing groups (19a–g) failed in the Suárez reaction (see Figure 2a). The bicyclo[2.2.2]octane system in the ent-atisane skeleton was formed in a three-step sequence: Mukaiyama oxidation/cleavage, aldol cyclization, and acetylation of the tertiary alcohol epimers. Protection proved necessary as the α-cleavage occurred under Suárez conditions on the free alcohol. This six-step sequence routinely yielded 2–3 g of “core” intermediate 10 in a single pass.

Figure 2.

(a) Other substrates explored in the Suárez reaction to activate C20. (b) Attempt to convert neopentyl iodide 21 into 22 where R = CHO or CH2OH. (c) Attempt to oxidize piperidine 23 into 24.

Specifically for (−)-isoatisine (4), the ketone in 10 needed to be removed. Direct methods of reduction were unsuccessful, and ultimately a Barton–McCombie deoxygenation gave 15. Yields for this transformation were low because only one diastereomer reacts productively in the reduction. Treatment of 15 with Suárez conditions provided iodo-imine 16. This reaction selectively goes through a 1,7-hydrogen abstraction at C20 as opposed to a typically more favorable 1,6-hydrogen abstraction at C2 or C6.11 Iodo-imine 16 was then treated with potassium carbonate and methanol in the same pot to give iodo-aldehyde 17. Martin’s sulfurane again gave good exo selectivity, and allylic oxidation of the olefin was highly diastereoselective to yield 18.2n Condensation and iodide displacement with ethanolamine gave (−)-isoatisine (4).12

Many challenges were encountered while attempting to forge the C14–C20 bond of the hexacyclic hetidine skeleton (8). Several efforts are summarized in Figure 2b and c. Conversion of the iodide in 21 to (1) an aldehyde with Kornblum or Ganem conditions; (2) an alcohol by treating with Ag(I) salts in the presence of water; (3) an alcohol through radical decomposition followed by trapping with TEMPO or O2; (4) an alcohol through oxidation of the iodide followed by rearrangement; or (5) an azide, thioether, or nitro group by displacement were all unsuccessful (Figure 2b). Alternatively, piperidine 23 was synthesized and a C20-selective oxidation to 24 was attempted (Figure 2c). Treatment with oxidants to form either the imine or the nitrone gave exclusive C19 oxidation. Attempts to isomerize the nitrone with a Behrend rearrangement failed.13 Inspired by the work of Seidel et al., condensation with a hindered benzaldehyde in the presence of a base to isomerize the iminium to C20 failed.14 Some desired product was obtained with a borrowing hydrogen strategy using [Cp*IrI2]2, but yields were only 20–30% at best.15

After extensive experimentation, a successful sequence was realized (see Scheme 2). Suárez conditions were again C20-selective to give iodo-imine 25. The yield was compromised by the formation of side products containing C14 iodination. Treatment of 25 with allylamine in methanol at 60 °C directly yielded hetidine skeleton 27. Allylamine served two purposes in this reaction: it condensed to form iminium 26, and it deprotonated at C20 to form an azomethine ylide. This species presumably isomerizes to the C20 iminium leading to Mannich cyclization.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Hetidine Skeleton 27 and Attempted Conversion to Hetisine Skeleton (30).

Reagents and conditions: (a) PIDA (4 equiv), I2 (5 equiv), DCE, 90-W sunlamp, 35 °C, 1 h (58–71%); (b) allylamine (5 equiv), MeOH, 60 °C, 12 h (78%); (c) LiAlH4 (4 equiv), ether, 0 °C, 1 h (62%); (d) Ph2S2 (1.5 equiv), AIBN (0.2 equiv), benzene, 80 °C, 2 h (78%); (e) NaOCl (5 equiv), CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 30 min (55%). PIDA = phenyliodine diacetate, DCE = 1,2-dichloroethane, THF = tetrahydrofuran, AIBN = azobis(isobutyronitrile), TFA = trifluoroacetic acid.

Hexacycle 27 was prone to a retro-Mannich reaction under mildly acidic conditions (i.e., SiO2 chromatography). To complicate matters, the deallylated, free amine form of this compound would undergo retro-Mannich cyclization under both mildly basic conditions (Hunig’s base, THF, rt) and acidic conditions (5% TFA, DCM, rt). For this reason, the carbonyl group was reduced to prevent decomposition. Several standard conditions to deprotect the allyl group failed presumably due to the extreme steric environment around the allylamine: it is essentially inside the “cage” of the molecule. The only successful procedure for deprotection was treatment with diphenyl disulfide and AIBN, a modified protocol inspired by the work of Bertrand.16

With the free amine 28 in hand, the final C6 C–H activation to form the hetisine skeleton was attempted. Formation of the chloramine went smoothly to give 29 (characterized by X-ray crystallography). Unfortunately, a variety of HLF conditions failed to give any chlorinated product. With Okamoto’s work3 as inspiration, the chloramine was also treated with Ag(I) salts or sodium methoxide; however, no desired product was formed in our hands. Indeed, we only observed returned secondary amine 28 (with or without the tertiary alcohol intact) or elimination of the chloramine to give either the C19 or C20 imine. After it was conceded that a C6 selective C–H activation on substrate 28 or 29 may not be possible, other substrates were pursued to complete the heptacyclic hetisine skeleton (30).

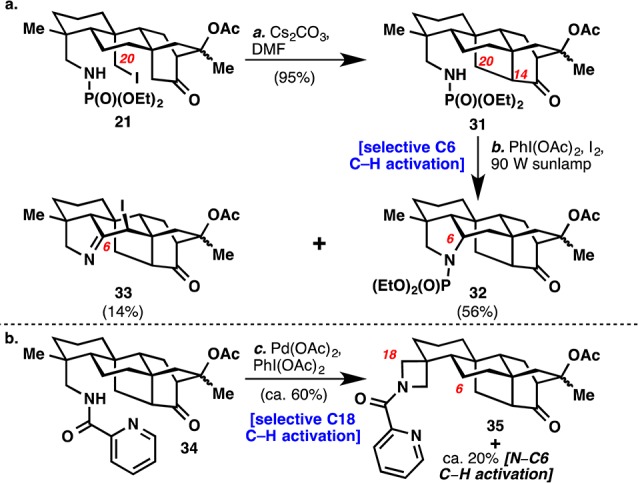

Many alternative strategies were attempted to complete the hetisine skeleton. One involved reversing the order of C–H activation to form the N–C6 bond prior to the N–C20 bond (Scheme 3a). Starting from iodide 21, intramolecular displacement formed the C14–C20 bond in 31. Interestingly, when this compound was subjected to the Suárez conditions, C–H activation occurred exclusively at C6 to give compounds 32 and 33. While the desired C6 oxidation was achieved, neither of these could be elaborated forward to the hetisine skeleton. During attempts to take advantage of work by Daugulis and Chen using the picolinamide directing group in 34, primarily C18 oxidation product 35 was observed.17 While this oxidation could be useful to access diterpenoid alkaloids with C18 oxidation such as davisinol,18 it was not useful for completing the hetisine skeleton or (−)-spirasine XI (6).

Scheme 3. Development of C6- and C18-Selective C–H Activation Reactions.

Reagents and Conditions: (a) Cs2CO3 (5 equiv), DMF, 40 °C, 22 h (95%); (b) PhI(OAc)2 (6 equiv), I2 (6 equiv), DCE, 90-W sunlamp, 23 °C, 1 h (32: 56%)(33: 14%); (c) Pd(OAc)2 (5 mol %), PhI(OAc)2 (2 equiv), toluene/acetonitrile (9:1), 80 °C, 14 h (ca. 60%).

In conclusion, ent-kaurane (−)-steviol (1) was successfully used as a common intermediate to access the ent-atisane, atisine, and hetidine natural product skeletons. In the case of the ent-atisanes and atisines, these skeletons were elaborated to (−)-methyl atisenoate (3) and (−)-isoatisine (4) in 6 and 13 steps from (−)-steviol (1), respectively. A unique Mukaiyama oxidation/fragmentation sequence was used to access the bicyclo[2.2.2]octane system. A Suárez modification of the HLF reaction provided exclusive C20 C–H activation via a 1,7-hydrogen abstraction overriding the typical 1,6-hydrogen abstraction selectivity. Finally, tandem condensation/azomethine ylide isomerization/intramolecular Mannich cyclization allowed access to the hetidine skeleton 27 in only 8 steps from (−)-steviol (1). While attempting to complete the hetisine skeleton, C6- and C18-selective C–H activation reactions were developed by taking advantage of subtle changes in substrate bias and mechanism. This work provides the most unified access to ent-atisanes and related diterpenoid-alkaloids to date.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by an unrestricted grant from TEVA, the NIH (GM-097444), the NSF (predoctoral fellowship to E.C.C.), and Bristol-Myers Squibb (fellowship to E.C.C.). We thank Dr. D.-H. Huang and Dr. L. Pasternack for NMR spectroscopic assistance and Dr. G. Siuzdak for assistance with mass spectroscopy. Prof. A. L. Rheingold and Dr. C. E. Moore are acknowledged for X-ray crystallographic assistance.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures, analytical data for all new compounds including 1H and 13C NMR spectra, and X-ray crystallographic data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- a Hamlin A. M.; Kisunzu J. K.; Sarpong R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Cherney E. C.; Baran P. S. Isr. J. Chem. 2011, 51, 391.and references therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Toyota M.; Wada T.; Fukumoto K.; Ihara M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 4916. [Google Scholar]; b Toyota M.; Waka T.; Ihara M. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 4565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Toyota M.; Asano T.; Ihara M. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 3929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Pelletier S. W.; Jacobs W. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956, 78, 4144. [Google Scholar]; e Pelletier S. W.; Parthasarathy P. C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1963, 4, 205. [Google Scholar]; f Nagata W.; Sugasawa T.; Narisada M.; Wakabayashi T.; Hayase Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 2342. [Google Scholar]; g Nagata W.; Sugasawa T.; Narisada M.; Wakabayashi T.; Hayase Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 1483. [Google Scholar]; h Ihara M.; Suzuki M.; Fukumoto K.; Kametani T.; Kabuto C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 1963. [Google Scholar]; i Ihara M.; Suzuki M.; Fukumoto K.; Kametani T.; Kabuto C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 1164. [Google Scholar]; j Liu X.-Y.; Cheng H.; Li X.-H.; Chen Q.-H.; Xu L.; Wang F.-P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Hamlin A. M.; Jesus-Cortez F.; Lapointe D.; Sarpong R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l Hamlin A. M.; Lapointe D.; Owens K.; Sarpong R. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 6783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m Muratake H.; Natsume M. Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 4746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n Peese K. M.; Gin D. Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 8734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o Peese K. M.; Gin D. Y. Chem.—Eur. J. 2008, 14, 1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Yatsunami T.; Isono T.; Hayakawa I.; Okamoto T. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1975, 3030. [Google Scholar]; b Yatsunami T.; Furuya S.; Okamoto T. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1978, 3199. [Google Scholar]

- a Ishihara Y.; Baran P. S. Synlett 2010, 12, 1733. [Google Scholar]; b Chen K.; Baran P. S. Nature 2009, 459, 824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Jørgensen L.; McKerrall S. J.; Kuttruff C. A.; Ungeheuer F.; Felding J.; Baran P. S. Science 2013, 341, 878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wilde N. C.; Isomura M.; Mendoza A.; Baran P. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 4909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherney E. C.; Green J. C.; Baran P. S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gutekunst W. R.; Baran P. S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yamaguchi J.; Yamaguchi A. D.; Itami K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 8960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibanuma Y.; Okamoto T. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1985, 33, 3187. [Google Scholar]

- Francisco C. G.; Herrera A. J.; Suárez E. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T.; Nozaki M.; Matsui M. Tetrahedron 1980, 36, 2641. [Google Scholar]

- a Isayama S.; Mukaiyama T. Chem. Lett. 1989, 1071. [Google Scholar]; b Gu X.; Zhang W.; Salomon R. G. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghisalberti E. L.; Jefferies P. R.; Mincham W. A. Tetrahedron 1967, 23, 4463. [Google Scholar]

- 4 was isolated as a mixture of (−)-isoatisine and 19-epi-(−)-isoatisine. See:Reinecke M. G.; Watson W. H. J. Org. Chem. 1987, 52, 5051. [Google Scholar]

- a Behrend R. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1891, 265, 238. [Google Scholar]; b Smith P. A. S.; Gloyer S. E. J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 2504. [Google Scholar]

- Das D.; Sun A. X.; Seidel D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 3765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saidi O.; Blacker A. J.; Farah M. M.; Marsden S. P.; Williams J. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 7375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoubet S.; Gastaldi S.; Timokhin V.; Bertrand M.; Siri D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 12343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhang S.; He G.; Zhao Y.; Wright K.; Nack W. A.; Chen G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 7313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nadres E. T.; Daugulis O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c He G.; Zhao Y.; Zhang S.; Lu C.; Chen G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulubelen A.; Desai H. K.; Srivastava S. K.; Hart B. P.; Park J. C.; Joshi B. S.; Pelletier W. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.