Abstract

Objective To investigate the long term effectiveness of integrated disease management delivered in primary care on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) compared with usual care.

Design 24 month, multicentre, pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial

Setting 40 general practices in the western part of the Netherlands

Participants Patients with COPD according to GOLD (Global Initiative for COPD) criteria. Exclusion criteria were terminal illness, cognitive impairment, alcohol or drug misuse, and inability to fill in Dutch questionnaires. Practices were included if they were willing to create a multidisciplinary COPD team.

Intervention General practitioners, practice nurses, and specialised physiotherapists in the intervention group received a two day training course on incorporating integrated disease management in practice, including early recognition of exacerbations and self management, smoking cessation, physiotherapeutic reactivation, optimal diagnosis, and drug adherence. Additionally, the course served as a network platform and collaborating healthcare providers designed an individual practice plan to integrate integrated disease management into daily practice. The control group continued usual care (based on international guidelines).

Main outcome measures The primary outcome was difference in health status at 12 months, measured by the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ); quality of life, Medical Research Council dyspnoea, exacerbation related outcomes, self management, physical activity, and level of integrated care (PACIC) were also assessed as secondary outcomes.

Results Of a total of 1086 patients from 40 clusters, 20 practices (554 patients) were randomly assigned to the intervention group and 20 clusters (532 patients) to the usual care group. No difference was seen between groups in the CCQ at 12 months (mean difference –0.01, 95% confidence interval –0.10 to 0.08; P=0.8). After 12 months, no differences were seen in secondary outcomes between groups, except for the PACIC domain “follow-up/coordination” (indicating improved integration of care) and proportion of physically active patients. Exacerbation rates as well as number of days in hospital did not differ between groups. After 24 months, no differences were seen in outcomes, except for the PACIC follow-up/coordination domain.

Conclusion In this pragmatic study, an integrated disease management approach delivered in primary care showed no additional benefit compared with usual care, except improved level of integrated care and a self reported higher degree of daily activities. The contradictory findings to earlier positive studies could be explained by differences between interventions (provider versus patient targeted), selective reporting of positive trials, or little room for improvement in the already well developed Dutch healthcare system.

Trial registration Netherlands Trial Register NTR2268.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a disabling respiratory disease affecting millions of people worldwide.1 Although no medical treatment can modify the course of the disease, multiple interventions are available to improve the wellbeing of patients and to reduce unnecessary hospital admissions due to exacerbations. However, these interventions are underused or suboptimally implemented.2 Irregular exacerbations, fluctuating symptoms, and various disabilities require a collaborative interaction between actively involved patients and a proactive multidisciplinary team.3 Such interaction is promoted by integrated disease management programmes developed in response to the evidently unsuccessful reactive response to disease progression.2

Recently, we published a Cochrane systematic review showing clinically relevant effects on disease specific health related quality of life and exercise capacity of COPD patients following an integrated disease management programme for at least three months.4 The review also showed that integrated disease management reduced respiratory related hospital admissions and days in hospital. This led to potential savings in healthcare costs, as shown in a second review.5 Interestingly, the effects and cost savings increased with severity of COPD. As COPD is a disease with increasing prevalence, and general practitioners and family physicians treat most patients, well designed studies of pragmatic integrated disease management programmes in primary care are essential. However, in COPD trials, the participants commonly comprise a small and selected fraction of the real world population, resulting in leading medical journals calling for studies in more representative patient populations.6 7 The few studies of integrated disease management in primary care recruited patients in secondary care,8 9 10 11 consisted of palliative programmes for severe patients,12 13 had a short duration of intervention,9 10 11 12 14 or did not correct for cluster analysis.15 The true effect of integrated disease management in primary care thus remains inconclusive. Therefore, the aim of this large pragmatic RECODE (randomized clinical trial on effectiveness of integrated COPD management in primary care) cluster randomised trial was to assess whether integrated disease management implemented in primary care is effective in improving the quality of life of COPD patients.

Methods

This study was performed in accordance with the study protocol.16

Study design and patients

We did a 24 month, cluster randomised controlled trial in which general practitioners were randomly assigned to the intervention (integrated disease management) or usual care. General practitioners were recruited from the western part of the Netherlands. Patients in both groups received an information leaflet stating that the aim of the study was to improve treatment of COPD in primary care and that general practitioners were randomised to two groups. All general practitioners and all participants gave written informed consent. Eligible participants had a diagnosis of COPD, according to GOLD (Global Initiative for COPD) guidelines.1 For all included patients, we attempted to verify the diagnosis by lung function tests. If spirometry data were not of sufficient quality or not available, patients were invited to participate for a lung function assessment, according to the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines for spirometry.17 Exclusion criteria were terminal illness, cognitive impairment, hard drug or alcohol misuse, and inability to fill in questionnaires. Recruitment of practices started in September 2010 and was finished in September 2011.

Intervention

The intervention was delivered at the cluster level. General practitioners, practice nurses, and specialised physiotherapists in the intervention group received a two day training course on incorporating integrated disease management in practice. Optionally, an additional team member (such as a dietitian or pulmonary specialist) could attend the course if they expressed interest. Elements of the course included performing/interpreting spirometry, assessment of disease burden, review of advice from international guidelines, motivational interviewing to stimulate a healthier lifestyle, and smoking cessation. Furthermore, the healthcare providers were trained in adopting self management action plans, including early recognition and treatment of exacerbations, encouragement of regular exercise and guideline based physical reactivation, cooperation with secondary care, and instructions in nutritional support. The secondary aim of the course was to provide a network platform for team members.

At the end of the second day, each practice team designed a specific time contingent plan in a group discussion with their multidisciplinary members. They decided which elements of integrated care they wanted to start implementing first, who would be responsible for which part of the interventions, and which steps to take to integrate integrated disease management into their daily practice. The practice plan they agreed to depended not only on the chairperson and the capacity of the team but also on the COPD care already provided at baseline and the priorities and feasibility in their practice. They received advice on the content and feasibility of their plan from the experts who guided the training. After six and 12 months, the intervention practices had a refresher course.

During the course, the team learnt the details of a web based decision support system for audit and feedback with patients’ and professionals’ portals, named Zorgdraad (“care ties”). The teams received practice tailored benchmark reports at baseline and at six and 12 months. All practices were free to determine and follow their individual plans and could choose to implement the Zorgdraad programme. The intensity of the integrated disease management programme for individual patients depended on health status, personal needs, and preferences, as well as on the capacity of the general practice team. As a result, patients with severe disease or at high risk were encouraged to receive multiple interventions, whereas other (for example, stable) patients had only regular control visits. All patient care was covered by the basic health insurance package that is compulsory in the Netherlands, except physiotherapy, which was additionally reimbursed for all RECODE patients with a Medical Research Council dyspnoea score above 2.

Healthcare providers in the control group were asked to continue their usual care, based on Dutch general practice COPD guidelines, in line with GOLD guidelines.1 The practice nurses in the usual care group received a course on technical performance of spirometry only, to divert attention from topics related to our intervention.

Randomisation and masking

To enhance comparability, a blinded researcher (NHC) stratified and matched participating clusters according to the following criteria: percentage of patients in practice from ethnic minorities, type of practice (single handed, one or more partner practice, or healthcare centre), practice location (urban/rural), age of general practitioner, and sex of general practitioner. Following this procedure, the same blinded researcher randomised matched clusters in pairs by using a computer generated list in four blocks of 10. Because of the nature of the intervention, participating healthcare providers and patients could not be blinded. Therefore, blinded research nurses assessed outcomes to minimise detection bias. Patients were instructed not to report on their type of management to these research nurses.

Outcomes

All outcomes were assessed at the level of the individual participant and are reported in supplementary table A. The primary outcome was change in health related quality of life on the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ)18 at 12 months. Secondary outcomes were change in health related quality of life as measured by the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ),19 Euro Qol-5D (EQ-5D),20 and Short Form 36 (SF-36).21 In addition, we measured MRC dyspnoea,22 Self-Management Ability Scale-30 (SMAS-30),23 daily physical activities (International Physical Activity Questionnaire; IPAQ24), level of care integration according to patients, measured by the Patient Assessment Chronic Illness Care (PACIC),25 smoking behaviour, and healthcare usage (including hospital admissions and moderate/severe exacerbations). Blinded research nurses administered these questionnaires at baseline and at six and 12 months. Postal questionnaires were sent at nine, 18, and 24 months. We extracted data on moderate exacerbations over the complete trial period from electronic medical records at 24 months. We defined a moderate exacerbation as a worsening of daily symptoms that led a patient’s physician to prescribe systemic corticosteroids, antibiotics, or both, without hospital admission. A severe exacerbation occurred when worsening symptoms required a hospital admission.

Statistical analysis

We based sample size estimates on the mean difference in CCQ score between intervention and control groups at 12 months. We used methods for standard sample size estimates for trials that randomise at the level of the individual,26 adjusting for clustering by inflating sample size estimates by the design effect given by 1+(n–1)ρ, where n is the average cluster size and ρ is the estimated intra-class correlation coefficient.27 Using the minimal clinically important mean difference of 0.4 for the CCQ,28 with a standard deviation of CCQ equal to 0.49 at 12 months, and the upper value of 0.05 from a range of intra-class correlation coefficient values identified in primary care studies,29 power calculations indicated that we needed 40 clusters of practices with an average of 27 participants per cluster. To allow for subgroup analysis of MRC scores 1-2 versus 3-5, a total of 1080 participants were needed to achieve a power of at least 80% with α levels of 0.05, including a loss to follow-up of 10% of participants or a loss of four clusters at 12 months.

The primary effectiveness analysis was an intention to treat analysis of the difference in mean CCQ score between groups at 12 months. Because of repeated measurements for all patients, we used linear mixed model analyses to assess differences within and between groups for all continuous outcomes, correcting for baseline scores, age, sex, proportion of patients with MRC score above 2, and clustering of patients per general practice. We used baseline scores as a dependent variable, the cluster was represented by a random effect, and the within patient covariance structure was unstructured. For dichotomous outcomes, we used logistic link generalised linear mixed models for repeated measurements to analyse differences within and between groups at all time points, correcting for the same covariates. We compared differences in two year moderate and severe exacerbation counts by using the negative binomial model,30 correcting for age, sex, MRC score above 2, exacerbation rate in the year before baseline, and clustering of patients per practice. This model returns incidence rate ratios, which in this case are exacerbation rates. On the basis of the literature, we did a priori defined subgroup analyses on the primary outcome of CCQ at 12 months.16

Results

Patients

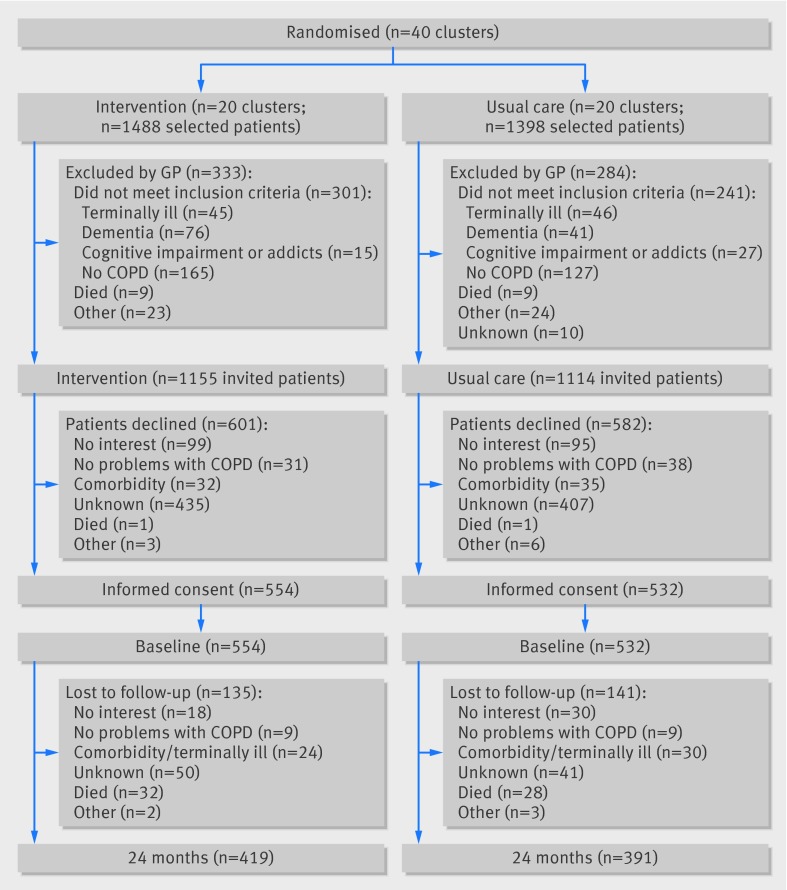

Figure 1 shows the screening, randomisation, and follow-up of patients.31 Supplementary figure A shows the dropout rates at the various time points. Table 1 summarises the baseline characteristics of the patients. Supplementary table B shows the characteristics of the general practices. Dropout rates at 12 months (9% intervention v 11% usual care) and 24 months (24% v 26%) were similar in the two groups. Patients who dropped out at 24 months were significantly older (P=0.002) and had worse scores on the CCQ, EQ-5D, PACIC, SF-36, SGRQ, and MRC questionnaires at baseline. Thirty two patients died in the intervention group and 28 in the usual care group. Causes of death were comparable between groups (P=0.54): COPD related (28% intervention; 36% usual care), cardiovascular disease (16%; 14%), and malignancies (16%; 21%). In 40% of the intervention patients and in 29% of the usual care patients, the cause of death was unknown.

Fig 1 Flow diagram of RECODE study

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients included in RECODE study. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Intervention (n=554; 20 clusters) | Usual care (n=532; 20 clusters) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Observations | Value | Observations | |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 68.2 (11.3) | 554 | 68.4 (11.1) 4 |

532 |

| Male sex | 280 (50.5) | 554 | 305 (57.3)* | 532 |

| Employment | 140 27.7 | 505 | 142 28.8 | 493 |

| Low education | 195 (39.2) | 498 | 195 (41.5) | 491 |

| Mean (SD) FEV1 % predicted | 67.7 (20.3) | 522 | 67.9 (20.5) | 498 |

| GOLD stage: | (n=458) | (n=409) | ||

| I—mild | 116 (25.3) | 458 | 97 (23.7) | 409 |

| II—moderate | 241 (52.6) | 458 | 220 (53.8) | 409 |

| III—severe | 87 (19.0) | 458 | 81 (19.8) | 409 |

| IV—very severe | 14 (3.1) | 458 | 11 (2.7) | 409 |

| Current smoker | 179 (34.8) | 515 | 196 (38.7) | 506 |

| Relevant comorbidities: | ||||

| Major cardiovascular disease | 81 (14.6) | 522 | 94 (17.7) | 515 |

| Hypertension | 196 (35.4) | 522 | 204 (38.3) | 515 |

| Diabetes | 81 (14.6) | 522 | 79 (14.8). | 515 |

| Depression | 54 (9.8) | 522 | 54 (10.1) | 515 |

| Mean (SD) CCQ score: | ||||

| Total | 1.5 (1.0) | 553 | 1.5 (1.0) | 527 |

| Symptoms | 2.1 (1.2) | 554 | 2.1 (1.2) | 531 |

| Functional | 1.5 (1.2) | 553 | 1.3 (1.2)* | 531 |

| Mental | 0.5 (1.0) | 554 | 0.5 (1.0) | 527 |

| Mean (SD) SGRQ score: | ||||

| Total | 36.7 (21.1) | 551 | 34.5 (19.8) | 529 |

| Symptoms | 51.6 (20.8) | 554 | 49.3 (20.9) | 530 |

| Activities | 49.4 (29.9) | 551 | 46 (29) | 531 |

| Impact | 24 (20.2) | 554 | 22.7 (19) | 530 |

| Mean (SD) MRC total score | 2.0 (1.3) | 553 | 2.0 (1.3) | 529 |

| MRC score >2 | 194 (35.1) | 553 | 167 (31.6) | 529 |

| Mean (SD) EQ-5D score | 0.74 (0.25) | 546 | 0.73 (0.28) | 528 |

| Mean (SD) EQ-5D VAS score | 66.6 (17.6) | 554 | 67.3 (17.3) | 532 |

| Mean (SD) SF-36 score, physical component | 38 (10.9) | 512 | 38.6 (10.7) | 503 |

| Mean (SD) SF-36 score, mental component | 48.3 (10.5) | 512 | 48.9 (10.3) | 503 |

| Mean (SD) SMAS score: | ||||

| Taking initiatives | 56.8 (17.8) | 518 | 56.9 (17.4) | 509 |

| Investment behaviour | 61.4 (16.8) | 517 | 59.3 (17.9) | 511 |

| Self-efficacy | 65.7 (17.2) | 516 | 64.3 (17.6) | 512 |

| Mean (SD) IPAQ, total MET minutes | 3150 (4696) | 546 | 3087 (4809) | 526 |

| IPAQ, high/moderate | 54 (10.0) | 541 | 70 (13.4) | 523 |

| IPAQ, low | 487 (90.0) | 541 | 453 (86.6) | 523 |

| Mean (SD) PACIC score: | ||||

| Total | 2.3 (0.9) | 436 | 2.3 (0.9) | 437 |

| Activation | 2.4 (1.2) | 435 | 2.2 (1.2) | 435 |

| Delivery system design | 3 (1.2) | 432 | 2.9 (1.1) | 436 |

| Goal setting | 2.2 (1.0) | 431 | 2.1 (0.9) | 433 |

| Problem solving | 2.3 (1.2) | 430 | 2.2 (1.0) | 433 |

| Follow-up/coordination | 1.8 (0.9) | 433 | 1.8 (0.8) | 431 |

| Mean (SD) exacerbations: | ||||

| Moderate exacerbation rate (12 months) | 0.4 (0.8) | 554 | 0.3 (0.8) | 532 |

| Severe exacerbation rate (3 months) | 0.02 (0.2) | 554 | 0.02 (0.2) | 532 |

| Hospital admission days (3 months) | 6 (2.1) | 554 | 8.6 (4.7) | 532 |

CCQ=Clinical COPD Questionnaire; GOLD=Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; EQ-5D=Euro Qol-5D; FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 second; IPAQ=International Physical Activity Questionnaire; MET=metabolic equivalent of task; MRC=Medical Research Council; PACIC=Patient Assessment Chronic Illness Care; SF-36=Short Form 36; SGRQ=St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; SMAS=Self-Management Ability Scale.

*Statistically significant difference between intervention and usual care groups.

Primary outcome

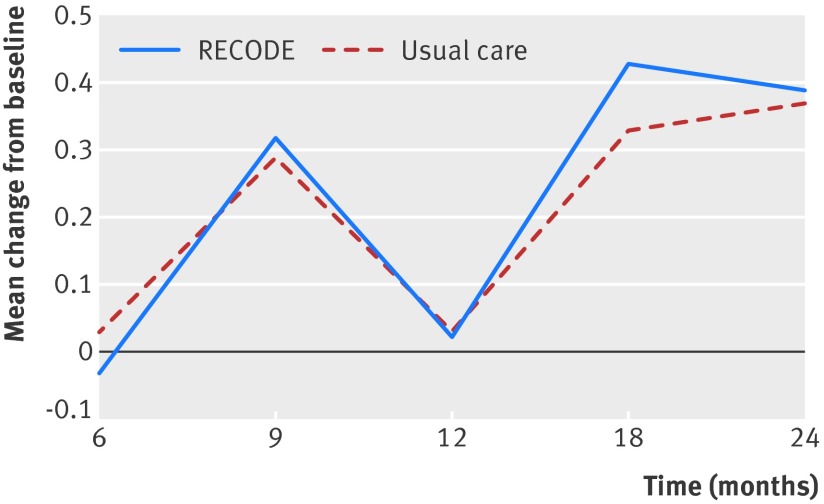

We found no statistically significant difference between the intervention and usual care groups in the CCQ score at 12 months (mean difference –0.01, 95% confidence interval –0.10 to 0.08; P=0.8) (table 2; fig 2).

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes: within and between group differences at 12 months, corrected for age, sex, baseline score, and MRC score >2. Values are mean (95% CI) unless stated otherwise

| Outcome | Intervention (n=554; 20 clusters) | Usual care (n=532; 20 clusters) | Mean difference (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCQ total score | –0.03 (–0.09 to 0.03) | 0.03 (–0.03 to 0.09) | –0.01 (–0.10 to 0.08) | 0.80 |

| CCQ—symptoms domain | –0.07 (–0.15 to 0.02) | –0.10 (–0.19 to 0.01) | 0.03 (–0.09 to 0.15) | 0.59 |

| CCQ—functional domain | 0.16 (0.08 to 0.25) | 0.21 (0.12 to 0.29) | –0.04 (–0.16 to 0.07) | 0.48 |

| CCQ—mental domain | –0.09 (–0.16 to –0.02) | –0.06 (–0.14 to 0.01) | –0.03 (–0.13 to 0.07) | 0.57 |

| SGRQ total score | –0.40 (–1.46 to 0.65) | 0.33 (–0.78 to 1.43) | –0.73 (–2.25 to 0.78) | 0.34 |

| SGRQ—symptoms domain | –0.75 (–2.43 to 0.93) | 0.22 (–1.52 to 1.96) | –0.97 ( –3.33 to 1.39) | 0.42 |

| SGRQ—activities domain | 0 ( –1.51 to 1.50) | 1.25 ( –0.32 to 2.82) | –1.25 ( –3.41 to 0.90) | 0.26 |

| SGRQ—impact domain | –0.31 (–1.46 to 0.85) | –0.35 (1.96 to 5.33) | 0.04 ( –1.61 to 1.70) | 0.96 |

| MRC dyspnoea score | 0.23 (0.14 to 0.33) | 0.19 (0.09 to 0.29) | 0.04 (–0.09 to 0.18) | 0.52 |

| EQ-5D | –0.04 (–0.06 to –0.02) | –0.01 (–0.03 to 0.01) | –0.03 (–0.06 to 0) | 0.07 |

| EQ-5D VAS score | –1.71 (–2.95 to 0.46) | –1.92 (–3.21 to –0.63) | 0.21 (–1.44 to 1.87) | 0.80 |

| SF-36—physical domain | –1.1 (–1.82 to –0.38) | –0.48 (–1.23 to 0.26) | –0.61 (–1.61 to 0.39) | 0.23 |

| SF-36—mental domain | 0.73 (–0.07 to 1.54) | 0.09 (–0.74 to 0.92) | 0.64 (–0.45 to 1.73) | 0.25 |

| SMAS—taking initiatives | –1.27 (–2.5 to 0) | –1 (–2.3 to 0.33) | –0.28 (–2.00 to 1.43) | 0.75 |

| SMAS—investment behaviour | –1.5 (–2.75 to –0.25) | –1.43 (–2.73 to –0.12) | –0.07 (–1.78 to 1.63) | 0.93 |

| SMAS—self-efficacy | –1.17 (–2.39 to 0.05) | –0.38 (–1.65 to 0.89) | –0.79 (–2.47 to 0.88) | 0.35 |

| IPAQ—total MET minutes | –44 (–475 to 387) | –438 (–886 to 11) | 393 (–179 to 965) | 0.18 |

| IPAQ—high/moderate (%) | 32.2 | 22.1 | 10.1 | <0.001 |

| PACIC—total score | –0.02 ( –0.11 to 0.08) | –0.08 (–0.18 to 0.02) | 0.06 (–0.06 to 0.19) | 0.31 |

| PACIC—activation | –0.03 (–0.16 to 0.1) | –0.5 (–0.19 to 0.08) | 0.03 (–0.14 to 0.19) | 0.76 |

| PACIC—delivery system design | –0.20 (–0.32 to –0.8) | –0.27 (–0.40 to –1.30) | 0.07 (–0.10 to 0.23) | 0.43 |

| PACIC—goal setting | 0.04 (–0.06 to 0.13) | –0.08 (–0.18 to 0.03) | 0.11 (–0.10 to 0.25) | 0.10 |

| PACIC—problem solving | 0.02 (–0.09 to 0.14) | –0.02 (–0.14 to 0.1) | 0.04 (–0.10 to 0.19) | 0.58 |

| PACIC—follow-up/coordination | 0.13 (0.04 to 0.21) | –0.02 (–0.11 to 0.07) | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.26) | 0.01 |

| Current smokers (%) | 48.6 | 51.7 | 3.1 | 0.56 |

| Hospital admission days | 10.5 (7.6 to 13.3) | 10.7 (7.4 to 14.0) | 0.2 (–4.3 to 4.3) | 0.92 |

| Moderate exacerbations (rate) | 0.58 (0.45 to 0.75) | 0.48 (0.37 to 0.62) | 1.22 (0.97 to 1.54)* | 0.09 |

| Severe exacerbations (rate) | 0.13 (0.08 to 0.21) | 0.10 (0.06 to 0.18) | 1.20 (0.78 to 1.84)* | 0.42 |

CCQ=Clinical COPD Questionnaire; EQ-5D=Euro Qol-5D; IPAQ=International Physical Activity Questionnaire; MET=metabolic equivalent of task; MRC=Medical Research Council; PACIC=Patient Assessment Chronic Illness Care; SF-36=Short Form 36; SGRQ=St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; SMAS=Self-Management Ability Scale.

Values are corrected for clustering, age, sex, score at baseline, and MRC score >2.

*Means rate ratio.

Fig 2 Change in Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) score at 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months, corrected for age, sex, baseline CCQ score, and MRC score above 2. Error bars represent standard errors. Score lower than 0 means improvement compared with baseline

Secondary outcomes and subgroup analyses

At 6, 9, 18, and 24 months, we found no statistically significant difference between intervention and usual care in the CCQ score (fig 2). At 12 months, the change from baseline in SGRQ, EQ-5D, SF-36, MRC, and SMAS scores was not significantly different between the intervention and usual care groups (table 2). The proportion of patients with moderate or high activity levels at 12 months as measured with the IPAQ improved significantly in the intervention group compared with the usual care group (mean difference 10.1; P<0.001). The PACIC domain “follow-up and coordination,” measuring improvement in follow-up structure of COPD patients, was significantly higher in the intervention group at 12 months (mean difference 0.15; P=0.01). The proportion of current smokers, as well as moderate and severe exacerbation rates and hospital admission rates, did not differ (table 2).

After 24 months of follow-up, the PACIC follow-up and coordination domain remained significantly higher in the intervention group (data not shown; mean difference 0.15; P=0.03). The other secondary outcomes did not differ significantly between groups at 24 months. Subgroup analyses showed no statistically significant effect of the intervention in any of the a priori defined subgroups (table 3). We did additional, a posteriori defined, subgroup analyses, which showed no significant effect of the intervention (supplementary table C).

Table 3.

Subgroup analyses: difference between intervention and usual care groups in change from baseline to 12 months’ follow-up in CCQ score for pre-specified subgroups. Values are mean (SE) unless stated otherwise

| Group | Intervention (20 clusters) | Usual care (20 clusters) | Intervention–usual care | P value | Subgroup by treatment interaction P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Mean (SE) | No | Mean (SE) | |||||

| Full cohort | 554 | 0.02 (0.03) | 532 | 0.03 (0.03) | –0.01 (0.04) | 0.82 | ||

| Sex: | 0.3 | |||||||

| Male | 280 | 0 (0.06) | 305 | 0 (0.06) | 0 (0.05) | 0.99 | ||

| Female | 274 | 0.01 (0.04) | 227 | 0.03 (0.03) | –0.02 (0.05) | 0.66 | ||

| Age: | 0.15 | |||||||

| <65 years | 212 | 0.17 (0.09) | 199 | 0.15 (0.09) | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.71 | ||

| ≥65 years | 342 | 0 (0.04) | 333 | 0.03 (0.03) | –0.03 (0.05) | 0.54 | ||

| GOLD stage: | 0.47 | |||||||

| I-II | 357 | –0.29 (0.07) | 317 | –0.33 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.46 | ||

| III-IV | 101 | 0.03 (0.06) | 92 | 0.03 (0.04) | 0 (0.07) | 0.96 | ||

| MRC score: | 0.2 | |||||||

| ≤2 | 359 | 0.03 (0.04) | 362 | 0.03 (0.03) | 0 (0.05) | 0.97 | ||

| >2 | 194 | 1.10 (0.07) | 167 | 1.13 (0.06) | –0.03 (0.06) | 0.63 | ||

Lower CCQ score means better quality of life. Values are corrected for clustering, age, sex, score at baseline, and MRC score >2.

Discussion

This cluster randomised trial examined a pragmatic set of interventions aiming to establish an integrated disease management programme, delivered by a multidisciplinary team to primary care patients with COPD. We found no differences between groups in quality of life, exacerbation related outcomes, self management, or MRC dyspnoea scores. However, significantly more patients in the intervention group had a self reported higher degree of daily activities, and the level of follow-up and coordination of the COPD patients improved.

Interpretation of findings

The results from our study were contrary to our expectations and to the positive results of the Cochrane systematic review.4 Several reasons might explain the difference in findings.

Firstly, our intervention was implemented at the level of the healthcare provider, whereas earlier studies were of patient targeted interventions. We specifically chose to study a pragmatic intervention that was developed on the basis of positive results of a controlled primary care study and implementation project.32 33 In these times of heavy workload in primary care, we gave the integrated disease management teams responsibility to develop their individual practice plans tailored to their own needs, to ensure ongoing implementation after the study was finished. This is clearly in contrast to other integrated disease management studies that applied patient targeted interventions and operated under more intensively supported, time consuming, and strictly regulated conditions.4 Therefore, a suboptimal intensity, but more realistic, implementation of the intervention may have contributed to the difference in effect between this study and earlier studies.

Secondly, in the intervening years, COPD care in the Netherlands has substantially evolved, which was partially unforeseen. Probably one of the most important triggers for general practitioners to start implementing integrated disease management was the start of a bundled payment system in 2010, which was our first study year. Although nationwide implementation of integrated disease management of COPD is still lacking, several regional projects have been started during recent years.34 35 Nowadays, COPD care has a better prepared delivery system with structured collaboration between healthcare professionals, more and better equipped nurses, and the development of clinical information systems to support the professional and the patient.36 Therefore, the considerable drive by health policies and providers to improve COPD care could have stimulated general practitioners in the usual care group to start implementing integrated disease management as well. The absence of effect due to already high levels of care was pointed out in other well designed Dutch and English primary care trials, studying components of COPD care.36 37 38 In contrast, a community based integrated intervention for early prevention and management of COPD in a Chinese setting, with a potentially larger room for improvement, showed a significant effect on smoking cessation rates and improvements in knowledge.39

Thirdly, studies with positive results are more likely to be published, and in high impact journals. In contrast to trial settings, healthcare providers trying to implement COPD programmes in daily life often experience problems with poor adherence or non-response, owing to lack of time, motivation, or cooperation of patients. This mismatch was illustrated by Bjoernshave et al, who showed that the populations included in the Cochrane systematic review of pulmonary rehabilitation were highly motivated and not representative of the target population, as 75% of the initially suitable patients were omitted owing to exclusion or drop out.40 Additionally, positive trial results have a higher chance of being referred to in guidelines. For example, the recent American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement41 recommends offering pulmonary rehabilitation to patients with milder COPD on the basis of results of two positive trials,8 42 whereas negative trials were not taken into consideration when these recommendations were formulated.14 43

Strengths and weaknesses of study

To best of our knowledge, this is the largest trial to date assessing the effectiveness of integrated disease management in primary care. Important features of this study are the long term follow-up and the inclusion of a sizeable real world, heterogeneous study population,6 7 which provided sufficient power to study differences in effect in subgroup analyses. Additionally, this pragmatic study included a wide range of outcomes relevant to primary care, including objective outcomes (moderate and severe exacerbation rates) and subjective measures (quality of life).7 We applied sophisticated regression techniques to facilitate the analysis of clustered longitudinal data.

After 24 months, dropout rates were low but selectively higher in patients with worse baseline scores. This raises questions of generalisability, although after correction for baseline scores no evidence existed for health benefits of the intervention at all, indicating that dropout is unlikely to have biased the result.

Blinding of participants and clinicians for this type of intervention was impossible. In an attempt to minimise bias, blinded research nurses collected the data and patients were instructed not to talk about their type of intervention. Although pairing and randomisation of the practices was done by a member of the research team, he was provided only with the characteristics of the practices (age and sex of general practitioner, type of practice). He was blinded to the identity of the practices and had no contact with the general practitioners.

The included practices were diverse in terms of setting, practice size, distribution of ethnic minorities, and level of COPD care at baseline.16 We corrected for most practice related factors by matching and stratification. However, a pre-existing high level of COPD care at baseline may have limited the potential for further improvement in already well developed practices. Additionally, because of the complex character of the intervention and the pragmatic study design, we were unable to assess the effect of individual components of the intervention.

Implications for practice

We found that an integrated disease management programme implemented in primary care did not improve quality of life and exacerbation related outcomes in a representative group of Dutch primary care patients with COPD. We observed an improved level of follow-up and structure of COPD care, as measured with the Patient Assessment Chronic Illness Care in the intervention group over the two year period, indicating important changes at an organisational level. However, this did not translate into differences in health outcomes. When interpreting the unforeseen findings of our study, policy makers and healthcare professionals should take into account the fact that primary care for COPD in the Netherlands is already at a high standard and has further evolved during the years of our intervention. Effect sizes might be greater in countries where primary care is less well developed.

On the basis of our experiences, an intervention directed at healthcare providers cannot be recommended for the generality of COPD patients. We advise application of more intensive, but still pragmatic programmes aiming at a selection of patients with a higher burden of disease and thus larger room for improvement. Exercise can be recognised as a compulsory element of integrated disease management.4 However, healthcare providers and insurers should realise that patients with mild disease often lack the motivation or do not feel the need (yet) to commit to an intensive (and expensive) integrated care or exercise programme.14 Therefore, resources are probably better spent if patients with a higher burden of disease are firstly thoroughly assessed and stratified for risk, after which a personalised treatment plan is made using a shared decision making process between patient and physician. The individual patient’s needs, preferences, and personal goals should play a key role in this process. Finally, we should take into account the fact that COPD is only one of the several chronic conditions we manage in primary care. Therefore, a more fruitful approach might be to consider integrated care for a suite of long term conditions with a high burden of disease, of which COPD is one component. The absolute number of patients eligible for this selective approach is probably relatively low, which makes having proper case management interventions in place possible.

Conclusion

In this study, integrated disease management incorporated in primary care was not effective in improving quality of life. The contradictory findings to earlier positive studies could be explained by differences between interventions (provider- versus patient targeted), selective reporting of positive trials, or little room for improvement in the well developed Dutch healthcare system.

What is already known on this topic

In a Cochrane systematic review, integrated disease management programmes for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) showed clinically relevant effects on quality of life and exercise tolerance and reductions in admissions and hospital days

However, most studies were in patients with severe COPD, and the studies in primary care recruited patients in secondary care, consisted of palliative programmes for severe patients, had a short duration of intervention, or did not correct for cluster analysis

What this study adds

Integrated disease management incorporated in primary care was not effective in improving quality of life or exacerbation related outcomes, such as hospital admissions and hospital days

The contradictory findings to earlier positive studies could be explained by differences between interventions (provider versus patient targeted), selective reporting of positive trials, or little room for improvement in the well developed Dutch healthcare system

A healthcare provider directed intervention cannot be recommended for the general population of COPD patients

Contributors: WJJA, JG, MPHMR, JKS, and NHC conceived and designed the study. ALK, MRSB, AT, and CB acquired the data. CB designed the integrated disease management programme for the study. ALK, MRSB, AT, NHC, and MPHMR analysed and interpreted the data. TS provided statistical expertise on this paper and analysed and interpreted the data. ALK drafted the manuscript. MRSB, NHC, AT, JG, WJJA, and MPHMR advised on the preparation of the manuscript. All authors read, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. ALK and MRSB are the guarantors.

Funding: This paper presents independent research funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (Zon-MW), subprogramme Effects and Costs (project number 171002203), and Stichting Achmea Gezondheidszorg, a Dutch Healthcare insurance company. The funding agencies (Zon-MW and Achmea Zorgverzekeringen) had no influence on the design of the study, the analysis, or the writing of the paper. Throughout the RECODE intervention period, physiotherapists in the intervention group received supplementary funding for providing a COPD specific exercise training programme in patients with MRC scores >2. This fund is provided by two local Dutch healthcare insurers: “Centraal Ziekenfonds (CZ) Zorgverzekeringen” and “Zorg en Zekerheid.” All other components of the integrated disease management programme were financially covered by the patients’ basic insurance scheme. The views expressed in this presentation are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the sponsors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work other than those detailed above; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the medical ethical committee of the Leiden University Medical Centre, the Netherlands. All general practitioners and participants gave written informed consent.

Data sharing: We are planning on producing publications using this dataset. Afterwards, the technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset will be available from the corresponding author.

Declaration of transparency: The lead authors (study guarantors) affirm that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;349:g5392

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: updated 2014. GOLD, 2014 (available at www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report_2014_Jun11.pdf).

- 2.Morgan MD. Action plans for COPD self-management: integrated care is more than the sum of its parts. Thorax 2011;66:935-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kruis AL, Chavannes NH. Potential benefits of integrated COPD management in primary care. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2010;73:130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kruis AL, Smidt N, Assendelft WJ, Gussekloo J, Boland MR, Rutten-van MM, et al. Integrated disease management interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;10:CD009437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boland MR, Tsiachristas A, Kruis AL, Chavannes NH, Rutten-van Molken MP. The health economic impact of disease management programs for COPD: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med 2013;13:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahlen SE, Dahlen B, Drazen JM. Asthma treatment guidelines meet the real world. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1769-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ware JH, Hamel MB. Pragmatic trials—guides to better patient care? N Engl J Med 2011;364:1685-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Wetering CR, Hoogendoorn M, Mol SJ, Rutten-van Molken MP, Schols AM. Short- and long-term efficacy of a community-based COPD management programme in less advanced COPD: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2010;65:7-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cambach W, Chadwick-Straver RV, Wagenaar RC, van Keimpema AR, Kemper HC. The effects of a community-based pulmonary rehabilitation programme on exercise tolerance and quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Resp J 1997;10:104-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wijkstra PJ, Ten Vergert EM, van Altena R, Otten V, Kraan J, Postma DS, et al. Long term benefits of rehabilitation at home on quality of life and exercise tolerance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1995;50:824-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendes de Oliveira JC, Studart Leitao Filho FS, Malosa Sampaio LM, Negrinho de Oliveira AC, Hirata RP, Costa D, et al. Outpatient vs. home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: a randomized controlled trial. Multidiscip Respir Med 2010;5:401-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boxall AM, Barclay L, Sayers A, Caplan GA. Managing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the community: a randomized controlled trial of home-based pulmonary rehabilitation for elderly housebound patients. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2005;25:378-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez AM, Pascual J, Ferrando C, Arnal A, Vergara I, Sevila V. Home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in very severe COPD: is it safe and useful? J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2009;29:325-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottlieb V, Lyngso AM, Nybo B, Frolich A, Backer V. Pulmonary rehabilitation for moderate COPD (GOLD 2)—does it have an effect? COPD 2011;8:380-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rea H, McAuley S, Lamont C, Roseman P, Didsbury P, Stewart A. A chronic disease management program can reduce days in hospital for patients with COPD. Respirology 2002;7:A6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruis AL, Boland MR, Schoonvelde CH, Assendelft WJ, Molken MP, Gussekloo J, et al. RECODE: design and baseline results of a cluster randomized trial on cost-effectiveness of integrated COPD management in primary care. BMC Pulm Med 2013;13:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van der Molen T, Willemse BW, Schokker S, ten Hacken NH, Postma DS, Juniper EF. Development, validity and responsiveness of the Clinical COPD Questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD 2005;2:75-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamers LM, McDonnell J, Stalmeier PF, Krabbe PF, Busschbach JJ. The Dutch tariff: results and arguments for an effective design for national EQ-5D valuation studies. Health Econ 2006;15:1121-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, Essink-Bot ML, Fekkes M, Sanderman R, et al. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1055-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, Garnham R, Jones PW, Wedzicha JA. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999;54:581-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schuurmans H, Steverink N, Frieswijk N, Buunk BP, Slaets JP, Lindenberg S. How to measure self-management abilities in older people by self-report: the development of the SMAS-30. Qual Life Res 2005;14:2215-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vandelanotte C, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Phillippaerts R, Sjostrom M, Sallis JF. Reliability and validity of a computerized and Dutch version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). J Phys Act 2005;63-75.

- 25.Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Schaefer J, Mahoney LD, Reid RJ, Greene SM. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC). Med Care 2005;43:436-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M. How many do I need? Basic principles of sample size estimation. J Adv Nurs 2004;47:297-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donner A, Birkett N, Buck C. Randomization by cluster: sample size requirements and analysis. Am J Epidemiol 1981;114:906-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kocks JW, Tuinenga MG, Uil SM, van den Berg JW, Stahl E, van der Molen T. Health status measurement in COPD: the minimal clinically important difference of the clinical COPD questionnaire. Respir Res 2006;7:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smeeth L, Ng ES. Intraclass correlation coefficients for cluster randomized trials in primary care: data from the MRC Trial of the Assessment and Management of Older People in the Community. Control Clin Trials 2002;23:409-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keene ON, Calverley PM, Jones PW, Vestbo J, Anderson JA. Statistical analysis of exacerbation rates in COPD: TRISTAN and ISOLDE revisited. Eur Respir J 2008;321:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2012;345:e5661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chavannes NH, Grijsen M, van den Akker M, Schepers H, Nijdam M, Tiep B, et al. Integrated disease management improves one-year quality of life in primary care COPD patients: a controlled clinical trial. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18:171-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kruis AL, van Adrichem J, Erkelens MR, Scheepers H, In ’t Veen H, Muris JW, et al. Sustained effects of integrated COPD management on health status and exercise capacity in primary care patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2010;5:407-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gress S, Baan CA, Calnan M, Dedeu T, Groenewegen P, Howson H, et al. Co-ordination and management of chronic conditions in Europe: the role of primary care—position paper of the European Forum for Primary Care. Qual Prim Care 2009;17:75-86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsiachristas A, Hipple-Walters B, Lemmens KM, Nieboer AP, Rutten-van Molken MP. Towards integrated care for chronic conditions: Dutch policy developments to overcome the (financial) barriers. Health Policy 2011;101:122-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bischoff EW, Akkermans R, Bourbeau J, van Weel C, Vercoulen JH, Schermer TR. Comprehensive self management and routine monitoring in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in general practice: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2012;345:e7642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trappenburg JC, Monninkhof EM, Bourbeau J, Troosters T, Schrijvers AJ, Verheij TJ, et al. Effect of an action plan with ongoing support by a case manager on exacerbation-related outcome in patients with COPD: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2011;66:977-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinnock H, Hanley J, McCloughan L, Todd A, Krishan A, Lewis S, et al. Effectiveness of telemonitoring integrated into existing clinical services on hospital admission for exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: researcher blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2013;347:f6070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou Y, Hu G, Wang D, Wang S, Wang Y, Liu Z, et al. Community based integrated intervention for prevention and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Guangdong, China: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;341:c6387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bjoernshave B, Korsgaard J, Nielsen CV. Does pulmonary rehabilitation work in clinical practice? A review on selection and dropout in randomized controlled trials on pulmonary rehabilitation. Clin Epidemiol 2010;2:73-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, Zuwallack R, Nici L, Rochester C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;188:e13-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vogiatzis I, Terzis G, Stratakos G, Cherouveim E, Athanasopoulos D, Spetsioti S, et al. Effect of pulmonary rehabilitation on peripheral muscle fiber remodeling in patients with COPD in GOLD stages II to IV. Chest 2011;140:744-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roman M, Larraz C, Gomez A, Ripoll J, Mir I, Miranda EZ, et al. Efficacy of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.