Abstract

Despite the high prevalence of and significant psychological burden caused by anxiety disorders, as few as 25% of individuals with these disorders seek treatment, and treatment seeking by African-Americans is particularly uncommon. This purpose of the current study was to gather information regarding the public’s recommendations regarding help-seeking for several anxiety disorders and to compare Caucasian and African-American participants on these variables. A community sample of 577 US adults completed a telephone survey that included vignettes portraying individuals with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social phobia/social anxiety disorder (SP/SAD), panic disorder (PD), and for comparison, depression. The sample was ½ Caucasian and ½ African American. Respondents were significantly less likely to recommend help-seeking for SP/SAD and GAD (78.8% and 84.3%, respectively) than for depression (90.9%). In contrast, recommendations to seek help for panic disorder were common (93.6%) and similar to rates found for depression. The most common recommendations were to seek help from a primary care physician (PCP). African Americans were more likely to recommend help-seeking for GAD than Caucasians. Findings suggested that respondents believed individuals with anxiety disorders should seek treatment. Given that respondents often recommended consulting a PCP, we recommend educating PCPs about anxiety disorders and empirically-supported interventions.

Keywords: anxiety disorders, dissemination, mental health literacy, treatment-seeking, race, treatment

Anxiety disorders affect over 40 million Americans each year (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005) and are associated with elevated rates of unemployment, increased rates of suicidal ideation and attempts, and decreased quality of life(Greenberg et al., 1999; Sareen et al., 2005). It is estimated that the national economic burden of anxiety disorders is between $108.6 million and $615.4 million per year per million inhabitants (for a meta-analysis, see (Konnopka, Leichsenring, Leibing, & König, 2009) and that anxiety disorders account for approximately 1/3 of mental health care costs(Rice & Miller, 1998).

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are both efficacious treatments for anxiety disorders (Hofmann & Smits, 2008; Koen & Stein, 2011; Norton & Price, 2007; Ravindran & Stein, 2010). Across anxiety disorders, approximately 60–85% of individuals achieve substantial symptom reduction after 12 to 16 sessions of CBT, and these gains are typically maintained at one-year follow-up (for a meta-analysis, see (Hofmann & Smits, 2008). SSRIs have also been shown to frequently reduce anxiety symptoms (Koen & Stein, 2011).

Despite the availability of these effective treatments, up to 75% of individuals suffering from anxiety disorders never seek professional help (Roness, Mykletun, & Dahl, 2005). Further, data suggest that the rates of treatment-seeking are even lower among African Americans than among Caucasians, (Alegría et al., 2002; Alvidrez, 1999; Gonzalez, Alegría, Prihoda, Copeland, & Zeber, 2011; Snowden & Yamada, 2005; Thompson et al., 2013). These rates are particularly concerning given that prevalence rates for anxiety disorders are approximately equal, or slightly higher, in African Americans as compared to Caucasians (for a review, see (Neal & Turner, 1991).

Low rates of treatment seeking for anxiety disorders may be partially explained by a reticence to seek mental health services. However, rates of treatment seeking for depression are quite a bit higher than for anxiety disorders, so simple reticence to seek help is unlikely to be the sole explanation. Indeed, prior work has shown that up to 60% of individuals with depression disorders seek help (Roness et al., 2005), compared to only about 25% for anxiety disorders. Furthermore, a large majority of individuals with depression seek services within one year of symptom onset (Roness et al., 2005), whereas those with anxiety disorders have been found to delay help-seeking for up to 23 years after onset of their symptoms (Wang et al., 2005).

Low mental health literacy (MHL), an individual’s knowledge and beliefs regarding mental illness and its treatment (Jorm et al., 1997; Jorm, 2000), may also impede seeking help for anxiety disorders. Specifically, a person’s inability to recognize the symptoms of an anxiety disorder as a problem warranting intervention is likely to decrease help seeking. Beliefs that the symptoms will go away on their own or that beneficial treatments are not available will have similar effects. In addition, it is currently unknown whether levels of MHL are similar across the different anxiety disorders, given shared features/overlapping characteristics of anxiety disorders, or whether levels of MHL differ between anxiety disorders as a result of their unique features. Therefore, documenting current levels of MHL for anxiety disorders, and the extent to which MHL varies among them in members of the general public is important.

Prior work has shown that many individuals do not recognize symptoms of depression or schizophrenia when portrayed in a vignette (Gulliver, Griffiths, & Christensen, 2010; Schomerus et al., 2012). Initial data suggest that recognition of anxiety disorders may also be poor. Specifically, a recent study of college students found that even when presented with a list of possible conditions from which to choose, recognition of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and panic disorder (PD) were both lower than recognition of depression (M. E. Coles & Coleman, 2010). Given the highly educated nature of the sample, it is likely that these estimates provide a ‘best-case’ scenario and that members of the general community would show poorer recognition of anxiety disorders. More recently, two independent studies examining MHL for anxiety in a large community sample found that again, the lay public recognizes anxiety disorders at a lower rate than depression (M. Coles, Schubert, Heimberg, & Weiss, 2014; Furnham & Lousley, 2013). Together, these findings suggest that rates of treatment-seeking in the anxiety disorders may be associated with poor MHL, specifically low recognition of symptoms and need for professional help.

The current study builds on previous research by examining help-seeking recommendations for anxiety disorders in a large community sample and comparing recommendations provided by Caucasians and African-Americans. Specifically, this study had three primary aims. The first was to document rates of recommendations for treatment-seeking by the lay public for a variety of anxiety disorders. In aim two, we sought to examine whether rates of recommendations to seek treatment differed significantly among the various anxiety disorders. This would provide insight as to whether public education campaigns can group the anxiety disorders together or if addressing them separately may be more advantageous. The third aim was to examine potential differences between Caucasians’ and African Americans’ recommendations about treatment-seeking behaviors for anxiety disorders. Finally, exploratory analyses were conducted to assess whether age, sex, level of education, and personal history of mental health treatment predicted the likelihood of recommending any type of help for the three anxiety disorders. These factors were selected as they are basic variables that can impact help-seeking.

Method

Sampling Method

The methods for this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both Binghamton University and Temple University. We sampled adult community members from across the United States by telephone survey. Telephone numbers of potential participants from throughout the US (N = 10,546) were obtained by the Institute for Survey Research (ISR) at Temple University from the national 48-State Landline Random Digit Dialing (RDD) sample provided by Genesys Sampling Systems. Demographic profiles of individuals in the RDD database were examined to generate a sample based on specific demographic factors of interest (e.g., race: African American, Caucasian). Of the initial 10,546 phone numbers, 4,578 were nonworking numbers.

Measures

During the telephone calls, interviewers administered the Anxiety Knowledge Survey (AKS), a structured interview designed to assess MHL for anxiety disorders. The AKS presents participants with vignettes portraying anxiety disorders (SP/SAD, GAD, PD) and also a vignette of a patient with depression that is included for comparison. The AKS then presents participants with a series of open-ended response questions regarding the disorders and treatment. Frequencies of help-seeking recommendations for each anxiety disorder vignette (SP/SAD, GAD, PD) were calculated. For comparison, frequencies of help-seeking recommendations were also calculated for the depression vignette. Next, respondents were asked open-ended questions about potential sources of help for each anxiety disorder. Responses were coded into the following categories: 1) primary care physician (PCP), 2) psychologist, 3) psychiatrist, 4) nonspecific mental health providers (e.g., “therapist,” “counselor,” “mental health specialist,” “social worker”), 5) clergy, and 6) other. Additional information regarding the AKS, including scripts of the vignettes, has been previously published (M. Coles et al., 2014).

Procedure

Calls were made by the ISR staff within five time blocks (10:00AM–12:00PM, 12:00PM–4:00PM, 4:00PM–6:00PM, 6:00PM–8:00PM, 8:00PM–9:00PM) between December 2010 and October 2011. Attempts to reach any phone number were discontinued following six unsuccessful calls. When a call was answered, the interview continued only if an individual age 18 or older was available. If the speaker declined participation, interviewers asked for another individual at the residence. Race information was obtained by the interviewers via self-report. Participants were paid $20 for participating in the interview.

Analytic Plan

To test whether frequencies of recommendations to seek treatment differed significantly across the vignettes, Cochran’s Q-tests were conducted comparing rates of recommending professional help-seeking, medication, or psychotherapy across anxiety disorder vignettes. Where overall significant differences were found, follow-up McNemar tests were performed to determine more specifically which anxiety disorders differed from one another on each index. Bonferroni corrections were applied to all McNemar tests to correct for multiple comparisons. Specifically, a critical alpha level of .008 was used (.05/6) in comparisons among three anxiety disorder vignettes plus depression for all follow-up significance tests. Finally, binary logistic regressions were conducted for each of the anxiety disorders in order to examine moderators of help-seeking recommendations. Specifically, age, race, sex, level of education, and personal history of mental health treatment were entered as predictors.

Results

Participants

Eight-hundred thirty two individuals were read the consent. From these 832, 188 refused participation, and ten participants’ data were dropped due to inaccurate recording, disconnected phone calls, or language barriers. Five hundred eighty-three individuals completed the study; however, six were not included in the final sample due to missing information regarding race or reporting their race as anything other than Caucasian or African American. With regard to sex, participants included in the final sample were 55.8% female (44.2% male). Participants were either African American (50%, n = 287) or Caucasian (50%, n = 290). Participants ranged in age from 18 to 92 years, with the mean age of the sample at 52.25 years (SD = 16.21 years). Regarding level of education, the average number of years of education completed was 12.57 years (SD = 1.84). With regard to annual household income, 30.0% of respondents reported income under $25,000, 25.7% reported household income between $25,001 and $50,000, 27.0% reported annual income between $50,001 and $100,000, and 17.3% reported the household income between $100,001 and $150,000. Finally, potential racial differences (Caucasian vs African American) on the demographic variables were explored. In comparison to the African American participants, the Caucasian participants were significantly older, t (570) = 4.96, p <.001, have a significantly higher proportion of males, χ2 (1, N=576), 11.04, p <.001, report higher levels of education, χ2 (2, N=574), 29.12, p <.001, and report higher income χ2 (3, N=514), 26.60, p <.001.

Rates and Sources of Recommending Help-Seeking

Overall, rates of recommendations to seek help for the anxiety disorders were high, with at least 75% of respondents recommending that the individual portrayed in each vignette seek professional help. Rates for specific anxiety disorders ranged from 78.6% for social phobia, 84.4% for GAD, up to 93.3% for panic disorder. With regard to the depression vignette, 90.9% of the sample recommended help-seeking. A Cochran’s Q-test revealed significant differences in recommendations to seek help among the vignettes, Q (3) = 74.13 p < .001. Follow-up McNemar tests demonstrated that respondents recommended help for social phobia less frequently than for the other anxiety disorders (GAD: χ2 (1, N = 555) = 8.69, p < .005; PD: χ2 (1, N = 556) = 53.78, p < .001), and depression, χ2 (1, N = 558) = 33.77, p < .005. Help-seeking recommendations were less frequently endorsed for GAD than for PD, χ2 (1, N = 566) = 25.01, p < .001, or depression, χ2 (1, N = 567) = 11.34, p = .001. No significant differences in help-seeking recommendations were found comparing depression and PD, χ2 (1, N = 569) = 2.03, p = .15.

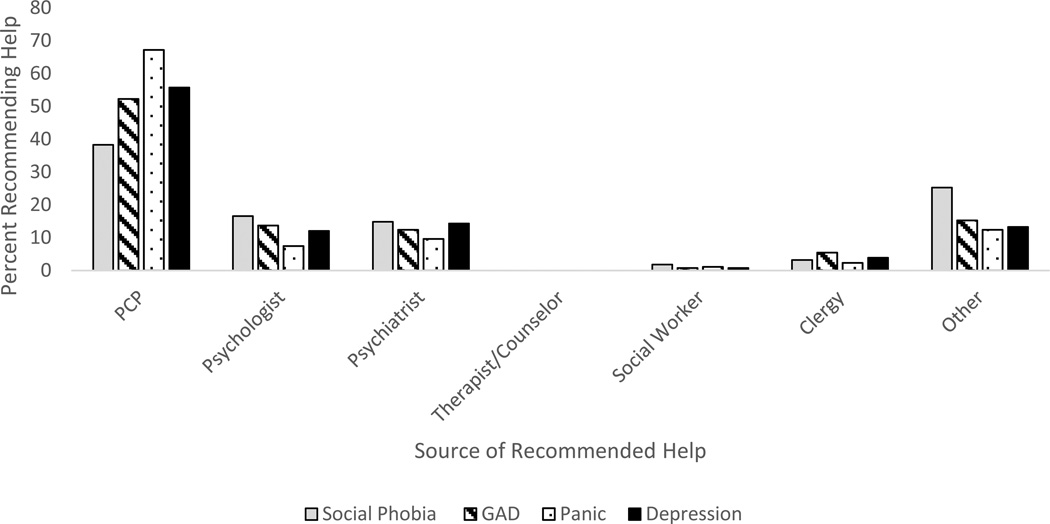

Turning to types of providers recommended as sources of help, between 35% and 70% of respondents recommended seeing a PCP, and other providers/sources of help were recommended by less than ¼ of respondents (See Figure 1). Pairwise comparisons were then conducted to further understand recommended sources of help. First, we examined the percent of respondents recommending seeing a primary care physician (PCPs) vs. mental health specialists (psychiatrists and psychologists). Cohchran’s Q-tests revealed significant differences in the types of providers recommended across anxiety disorders, Q (2) = 32.17, p < .001. Follow-up McNemar tests demonstrated that respondents recommended PCPs, as compared with mental health specialists, at greater rates for PD than for GAD, χ2 (1, N = 316) = 18.02, p < .001, or SP/SAD, χ2 (1, N = 259) = 28.46, p < .001. Recommendations to seek help from PCPs were greater for GAD than SP/SAD, χ2 (1, N = 235) = 6.78, p < .01. Next, comparing recommendations to seek help from psychologists versus psychiatrists, a Cochran’s Q-test revealed no significant differences across anxiety disorders, Q (2) = 0.57, p = .75. Finally, analyses compared responses reflecting specific health/mental health specialists (i.e., PCP, psychologist, psychiatrist) with responses reflecting non-specific mental health providers (i.e., therapist, counselor, mental health specialist, behavior health provider). Cohchran’s Q-tests revealed that there were significant differences in recommending specific versus non-specific providers across anxiety disorders, Q (2) = 52.53, p < .001. Follow-up McNemar tests demonstrated that respondents recommended specific providers, as compared with non-specific mental health professions, at greater rates for PD than for GAD, χ2 (1, N = 369) = 8.83, p < .01, or SP/SAD, χ2 (1, N = 331) = 46.08, p < .001. Recommendations to seek help from specific providers were greater for GAD than SP/SAD, χ2 (1, N = 293) = 24.50, p < .001.

Figure 1.

Recommended sources of help-seeking for anxiety disorder and depression vignettes.

Racial Differences

Potential racial differences in rates of recommending help-seeking were examined for each of the anxiety disorders. Chi-squared tests demonstrated that African Americans were significantly more likely to recommend seeking help for GAD than Caucasians, χ2 (1, N = 569) = 4.42, p < .04. Specifically, 87.6% of African-Americans recommended help-seeking for GAD in comparison to 81.2% of Caucasians. In contrast, significant racial differences were not found for SP/SAD, χ2 (1, N = 569) = .61, p = .44, or PD, χ2 (1, N = 569) = 1.29, p =.26. Next, logistic regressions were conducted to examine potential racial differences in the types of providers recommended for each of the three anxiety disorder vignettes. Significant differences were found showing that Caucasian participants were significantly more likely to recommend seeing a PCP for SP/SAD in comparison to African Americans who were more likely to recommended a mental health specialist (e.g., psychiatrist, psychologist) B= .88, OR= 2.40, p <.001. None of the other comparisons of the two races were statistically significant.

Additional Potential Moderators of Help-Seeking Recommendations

To determine whether additional demographic variables were related to the likelihood of recommendations to seek help for the anxiety disorders, a forward stepwise logistic regression was conducted for each of the three anxiety disorder vignettes (SP/SAD, GAD, PD). Predictors entered into the logistic regressions included: age, sex, level of education, and personal history of mental health treatment. Regarding the likelihood of recommending help for each of the anxiety disorders included, only one significant predictor was identified. Specifically, a personal history of psychotherapy significantly predicted the likelihood of recommending help-seeking for GAD, χ2 (1, N = 319) = 12.72, p <.001. Personal history of psychotherapy did not significantly predict recommendations related to SP/SAD or PD, and age, gender and income did not significantly predict the likelihood of recommending help for any of the anxiety disorders.

Discussion

Results of the current study showed that when presented with information regarding the symptoms and impact of experiencing an anxiety disorder, over 75% of respondents reported that they would recommend help-seeking. This rate is higher than what had been anticipated given that less than 25% of individuals with anxiety disorders seek help for themselves. Small differences were found among the different types of anxiety disorders studied herein, with social phobia associated with the lowest rates of respondents recommending help (79%). Findings of very few differences as a function of race were somewhat unexpected and suggest that lower rates of treatment seeking African Americans may occur at different points in the help seeking process. For example, our findings suggest that African-Americans and Caucasians similarly report that they would recommend help to a friend, however, the friend’s response to this recommendation and ability to access services may differ according to race. Regarding sources of help, primary care physicians were by far the most common source of help recommended. This suggests that efforts to further enhance primary care physician’s knowledge of the symptoms and evidence-based treatment of anxiety disorders would be beneficial. Finally, despite being encouraged by the findings overall, it is worth noting that the finding that 91% of respondents recommended help for depression suggests that mental health literacy for anxiety disorders can be improved further.

The findings herein that the majority of respondents would recommend help seeking to peers is important in understanding the pathways to receiving appropriate care for anxiety disorders. Given that anxiety disorders affect over 40 million Americans each year (Kessler et al., 2005), increasing the proportion of these individuals who receive evidence-based treatment would reduce the substantial burden on the healthcare system while reducing personal suffering as well. Further, given that most individuals reported that they would suggest seeking help for the individual suffering from the anxiety, future studies could examine whether these recommendations are voiced to the person experiencing them and how the other individual responds. They also suggest the possibility that campaigns to increase recognition of anxiety disorders may be needed to increase the proportion of individuals receiving treatment for anxiety disorders to levels similar to those found for depression. Finally, given that anxiety disorders often precede the onset of depression, increasing the number of individuals who receive effective treatment for anxiety disorders may also lead to decreases in rates of depression.

The current study is clearly not without limitations. First, sampling issues impact the nature of the findings. For example, as with many other studies of similar design, participation rates were far from universal. Recruitment of African Americans was particularly difficult and resulted in demographic differences between the groups. In addition, it appears that individuals who had previously received psychotherapy were overrepresented in the current sample. Specifically, over 50% of the sample endorsed having received counseling or therapy for psychological problems in the past, a rate that is considerably higher than reported in prior work examining treatment seeking in the general public (Andrews, Issakidis, & Carter, 2001; Levinson, Lerner, Zilber, Grinshpoon, & Levav, 2007).

Another potential limitation is that the vignettes used in this study were designed to accurately and comprehensively reflect DSM-IV criteria for the anxiety disorders and additional information about the persons in the vignettes that was not clearly relevant to their diagnosis was not included. Findings herein are therefore likely to be an overestimation of help-seeking recommendations, considering that it is unlikely that community members would communicate their own mental health concerns to others in such clearly defined terms without additional information. For example, in the ‘real world,’ friend’s reticence to give speeches and talk with authority figures may be less likely to be noticed when part of the larger context of the friend discussing her son’s upcoming graduation, her mother’s recent difficulty remembering things, and her plans for summer vacation. In addition, given that anxiety disorders typically onset during childhood or adolescence, individuals may view the affected individual as always having exhibited such behaviors and thereby less likely to see them as a problem.

Despite the limitations of the current study, the findings are important in showing that most individuals in the current sample reported that they would recommend help seeking when provided with clear information regarding an individual experiencing the symptoms and impact of anxiety disorders. In summary, the current study demonstrated that rates of recommending professional help for anxiety disorders in the community are relatively high in both Caucasians and African Americans. However, given the low rates of mental health service utilization for anxiety disorders, and the substantial societal burden of untreated anxiety, future work is needed to explore the relations among recommendations and actual treatment-seeking behavior.

Acknowledgements

Support for this research was provided by National Institute of Mental Health Award 1 R21 MH082754-01A1 to the first author. We would like to thank the staff of the Institute for Survey Research (ISR), particularly Keisha Miles and David Tucker, for their assistance on this project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alegría M, Canino G, Ríos R, Vera M, Calderón J, Rusch D, Ortega AN. Mental health care for latinos: Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among latinos, african americans, and non-latino whites. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(12):1547–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J. Ethnic variations in mental health attitudes and service use among low-income african american, latina, and european american young women. Community Mental Health Journal. 1999;35(6):515–530. doi: 10.1023/a:1018759201290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Issakidis C, Carter G. Shortfall in mental health service utilisation. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science. 2001;179:417–425. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.5.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles M, Schubert J, Heimberg R, Weiss B. Towards reducing the burdens of anxiety disorders-- step 1: Recognizing the problem. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.07.011. Submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles ME, Coleman SL. Barriers to treatment seeking for anxiety disorders: Initial data on the role of mental health literacy. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27(1):63–71. doi: 10.1002/da.20620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnham A, Lousley C. Mental health literacy and the anxiety disorders. Young. 2013;6:8. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JM, Alegría M, Prihoda TJ, Copeland LA, Zeber JE. How the relationship of attitudes toward mental health treatment and service use differs by age, gender, ethnicity/race and education. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2011;46(1):45–57. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0168-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, Kessler RC, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, Davidson JR, Fyer AJ. The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1999 doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(1):113. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Smits JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):621. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF. Mental health literacy public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;177(5):396–401. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.5.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Rodgers B, Pollitt P, Christensen H, Henderson S. Helpfulness of interventions for mental disorders: Beliefs of health professionals compared with the general public. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;171(3):233–237. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koen N, Stein DJ. Pharmacotherapy of anxiety disorders: A critical review. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2011;13(4):423. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.4/nkoen. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konnopka A, Leichsenring F, Leibing E, König H. Cost-of-illness studies and cost-effectiveness analyses in anxiety disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;114(1):14–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson D, Lerner Y, Zilber N, Grinshpoon A, Levav I. Twelve-month service utilization rates for mental health reasons: Data from the israel national health survey. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences. 2007;44(2):114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal AM, Turner SM. Anxiety disorders research with african americans: Current status. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;109(3):400. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Price EC. A meta-analytic review of adult cognitive-behavioral treatment outcome across the anxiety disorders. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195(6):521–531. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253843.70149.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran LN, Stein MB. The pharmacologic treatment of anxiety disorders: A review of progress. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71(7):839–854. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10r06218blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice DP, Miller LS. Health economics and cost implications of anxiety and other mental disorders in the united states. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roness A, Mykletun A, Dahl A. Help-seeking behaviour in patients with anxiety disorder and depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2005;111(1):51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, de Graaf R, Asmundson GJ, ten Have M, Stein MB. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: A population-based longitudinal study of adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(11):1249. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomerus G, Schwahn C, Holzinger A, Corrigan P, Grabe H, Carta M, Angermeyer M. Evolution of public attitudes about mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2012;125(6):440–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden LR, Yamada A. Cultural differences in access to care. Annu.Rev.Clin.Psychol. 2005;1:143–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R, Dancy BL, Wiley TR, Najdowski CJ, Perry SP, Wallis J, Knafl KA. African american families’ expectations and intentions for mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2013;40(5):371–383. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0429-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):603. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]