Abstract

Exposure to early adversity places young children at risk for behavioral, physiological, and emotional dysregulation, predisposing them to a range of long-term problematic outcomes. Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC) is a 10-session intervention designed to enhance children’s self-regulatory capabilities by helping parents to behave in nurturing, synchronous, and non-frightening ways. The effectiveness of the intervention was assessed in a randomized clinical trial, with parents who had been referred to Child Protective Services (CPS) for allegations of maltreatment. Parent-child dyads received either the ABC intervention or a control intervention. Following the intervention, children from the ABC intervention (n = 56) expressed lower levels of negative affect during a challenging task compared to children from the control intervention (n = 61).

Keywords: Neglect, Parenting, Emotion expression

Young children referred to Child Protective Services (CPS) may experience a range of adverse early experiences, including abuse, homelessness, poverty, neglect, and exposure to violence. These experiences can lead to a variety of problems, including difficulties with the regulation of behavior, physiology, and affect (Bernard, Butzin-Dozier, Rittenhouse, & Dozier, 2010; Gunnar & Vazquez, 2001). Parents, serving as co-regulators, play a critical role in supporting young children’s regulatory development during infancy, and in helping children as they gradually begin to take over regulatory functions themselves during the toddler and preschool years (Calkins & Keane, 2009; Kopp, 1982; Raver, 1996). However, CPS-referred and other high-risk parents often fail to provide the kinds of interactions critical for the development of children’s regulatory capabilities (Dadds, Mullins, McAllister, & Atkinson, 2003; Shipman et. al., 2007). Thus, there is a compelling need for effective interventions for families who have been referred to CPS but whose children remain living with their biological caregivers.

The Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC) intervention was developed to help parents learn to behave in ways that support children’s ability to develop self-regulatory skills, and addresses many issues relevant for CPS-referred families. The present study assessed the effects of this intervention on expression of negative affect in CPS-referred children, a key component of affect regulation.

Effects of Early Adversity on Emotion Expression

Early childhood is an important period for the development of emotional competence in children (Kopp, 1989; Kopp & Neufeld, 2003). Emotional competence involves the expression of emotions and the appropriate control of emotional expressiveness under different conditions (Denham et al., 2003; Miller et al., 2006; Saarni, 1999). An important component of this control of emotional expressiveness is the ability to regulate expression of negative affect during challenging or frustrating situations. Difficulties regulating the expression negative affect have been linked with later behavior problems and lower social competence (Cole & Smith, 1993; Dennis, Cole, 2009; Eisenberg, 2000; Fabes, 1991; Hill, Calkins, 2006).

Given the central role that parents play in the development of children’s ability to regulate their emotion expression, it is not surprising that maltreated children display deficits in emotional development (Field, 1994; Graziano, Keane, & Calkins, 2010; Thompson, 1994). Human infants are born almost fully dependent on parents, and many aspects of development rely on parent’s involvement (Hofer, 1994; Winberg, 2005). This is especially true of children’s developing regulation abilities, as parents serve a key role as co-regulators of behavior, affect, and physiology (Calkins & Keane, 2009; Hofer, 1994). Through many successful experiences in which infants regulate emotions effectively with the help of a parent, children are gradually able to take over the regulatory processes themselves. Therefore, these parent-child interactions during infancy and toddlerhood are critical for the development of child emotion expression and regulation capabilities (Calkins, 1994; Thompson & Myer, 2007).

Maltreating parents often fail to provide the critical support necessary for the development of children’s emotional competence. Specifically, maltreating parents have been found to engage in less validation and more invalidation of children’s emotions compared to non-maltreating parents (Dadds et al., 2003; Shipman et al., 2007). These controlling and dismissing parental responses have been linked to greater emotion regulation difficulties and increased anger expression in young children (Dadds & Rhodes, 2008; Denham, Mitchell, Strandberg, Auerbach, & Blair, 1997; Lunkenheimer, Shields, & Cortina, 2007).

Children who experience maltreatment lack a co-regulator at a crucial time in development. As would be expected given how central parental input is to children’s developing regulatory capabilities, problems are seen among maltreated children in the regulation of behavior, physiology, and emotions (Bernard et al., 2010; Blandon et al., 2010). Bernard et al. (2010) demonstrated that children living with maltreating parents showed a dysregulated, flatter, pattern of diurnal cortisol production compared to children living with foster parents or children living under low-risk conditions. Blunted cortisol is predictive of externalizing behavior problems in early childhood (Alink et al., 2008). Parental maltreatment and inattention have also been associated with deficits in inhibitory control and problems regulating behavior (e.g., Blandon et al., 2010; Field, 1994). Most important to the issues addressed in this paper, maltreated children exhibit more negative affect under challenging conditions than seen among non-maltreated children (Calkins et al., 1998; Erickson, Egeland, & Pianta, 1989; Gaensbauer, 1982; Shields, 1998).

Targeting Emotion Expression through Intervention

Given that maltreatment is associated with problems regulating the expression of negative affect, it is critical that interventions target this key developmental task among CPS-referred children. Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC) was designed to enhance children’s ability to regulate their affect, behavior, and physiology by helping parents serve as co-regulators. The specific parent behaviors targeted in the intervention include: a) behaving in synchronous ways, b) responding in nurturing ways to children’s distress, and c) avoiding frightening behaviors. Taken together, synchronous, nurturing, and non-frightening interactions are expected to enhance children’s developing regulatory capabilities.

The first component, enhancing parental synchrony, was included as an intervention target to help improve children’s ability to regulate physiology, emotions, and behavior. During the intervention sessions, parents are helped to follow their child’s lead and give the child control over the interactions. Shonkoff and Bales (2011) described this give and take of synchronous interactions as “serve and return” (e.g., the child “serves” with a bid for the parent’s attention, and the parent “returns” with an immediate and appropriate response). For example, if a child bangs two blocks together, a parent might respond synchronously by imitating the child (i.e., also banging two blocks together), commenting on what the child is doing (e.g., “You’re banging the blocks!”), or taking delight in what the child is doing. According to Shonkoff and Bales, these “serve and return” interactions are integral to the development of young children’s brain architecture, laying the foundation for the development of behavioral and regulatory capabilities over time (National Scientific Council of the Development Child, 2004). Further, by responding quickly and sensitively, parents both help children to regulate their affect, and also provide children opportunities to express emotions in ways that feel controllable (Maughen & Cicchetti, 2002). This synchronous responding has been shown to decrease the amount and intensity of negative affect displayed by infants (Spinrad & Stifter, 2002), with infants of unresponsive parents showing significantly more sadness and anger compared to infants of responsive parents (Cohn & Tronick, 1983; Pickens & Field, 1994).

The second intervention component, enhancing parental nurturance when children are distressed, is associated with children developing secure, organized attachments (Bernard et al., 2012; De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997), and learning to manage negative affect effectively (Brown, Fitzgerald, Shipman, & Schneider, 2007; Eisenberg, Fabes, & Murphy, 1996; Spinrad, Stifter, Donelan-McCall, & Turner, 2004). Nurturance refers to sensitive responses that occur specifically in response to child distress. For example, when a child falls down and bumps his head, a mother might say, “Oh sweetie, are you okay?” while reaching out her arms to invite the child in for comfort. A supportive and nurturing parent can help children learn to rely upon the parent for support, and help children develop the capacity to manage their distress (Calkins, 1994; Fogel, 1982). In the long term, these experiences with a nurturing parent are expected to enhance children’s sense of efficacy in modulating their emotions (Cole, Martin, & Dennis, 2004).

The intervention’s third objective is to help parents learn to behave in ways that are not frightening to the child. Frightening behavior can take many forms, such as being physically intrusive (e.g., rough tickling that disregards the child’s cues), yelling or verbally threatening the child, and hitting the child. When parents behave in frightening ways, children experience “fright without solution” in the words of Mary Main (1995). Frightening parental behavior is associated with disorganized attachment in infancy (van IJzendoorn, Schuengel, C., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1999), which is the type of attachment pattern most commonly observed in maltreated children and children who experience multiple risk factors (Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn., 2010). Further, frightening parental behavior is associated with controlling, angry behavior in preschool children (Moss, Cyr, Bureau, Tarabulsy, & Dubois-Comtois, 2005). Thus, harsh, controlling, or frightening parental behavior can interfere with children’s ability to control their emotion expression (Calkins et al., 1998; Eisenberg et al., 1999; Spinrad et al., 2004). Helping parents avoid behavior that is frightening to children is therefore an important objective of the ABC intervention.

The ABC intervention has proven effective in enhancing children’s attachment organization and regulation of cortisol production during early stages of children’s development. In a study of infants in foster care, children who received the ABC intervention displayed a more normalized cortisol production pattern, compared to children who received the control intervention (Dozier et al., 2006). In an earlier follow-up of the CPS-referred children, Bernard et al. (2012) found that fewer of the children whose parents received the ABC intervention developed disorganized attachments to their parents around 20 months of age than children whose parents received the control intervention. The effects of the intervention on children’s expression of negative affect had not been investigated prior to the current study.

The Present Study

This study investigated the effectiveness of the Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up intervention in a randomized clinical trial for young children who had been reported to Child Protective Services (CPS). We expected children in the ABC intervention group to show lower expression of negative affect in a challenging task than children in the control intervention group.

Method

Participants

Participants included 117 children and 112 caregivers (5 parents had two children enrolled in the study) who had been reported to Child Protective Services (CPS) in a large, mid-Atlantic city due to allegations of maltreatment. We did not have access to case records, so were unable to systematically measure reason for referral or history of other risk factors (e.g., substance abuse). However, all children referred to the present study remained with their biological parents. Given that children with unsubstantiated reports of maltreatment look very similar to those with substantiated reports in terms of concurrent risk factors, negative outcomes, and rates of future re-reports to CPS (Drake, Jonson-Reid, Way, & Chung, 2003; Drake, 1996; English, Marshall, Coghlan, Brummel, & Orme, 2002; Hussey et al., 2005; Jonson-Reid, Drake, Kim, Porterfield, S., & Han, 2004), we aimed to intervene with families regardless of substantiation status.

Demographic information for children and parents is presented in Table 1. Of the 103 parents who provided information about their level of education, 68% did not complete high school, 29% earned a high school diploma, and 3% completed some college. One child (in the control group) was living with a relative caregiver at the time of providing post-intervention data used in analyses for the present study. This child was removed from birth parent care following enrollment, and the relative caregiver completed the intervention sessions and post-intervention research visits.

Table 1.

Demographic Information across Intervention Groups at Post-intervention Follow-up

| Variable | Intervention Group

|

|

|---|---|---|

| ABC Child: (n = 56) CG: (n = 54) |

DEF Child: (n = 61) CG: (n = 58) |

|

| Child Demographic Characteristics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 31 (55%) | 31 (51%) |

| Female | 25 (45%) | 30 (49%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 5 (9%) | 5 (8%) |

| African American | 35 (62%) | 37 (61%) |

| Biracial | 14 (25%) | 5 (8%) |

| Hispanic | 2 (4%) | 14 (23%) |

| Age at Tool Task (months) | M = 26.7 (SD = 3.8) | M = 26.2 (SD = 3.0) |

| Caregiver Demographic Characteristics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) |

| Female | 52 (96%) | 57 (98%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 10 (19%) | 6 (10%) |

| African American | 35 (65%) | 36 (62%) |

| Biracial | 4 (7%) | 1 (2%) |

| Hispanic | 5 (9%) | 15 (26%) |

| Age at Tool Task (years) | M = 28.7 (SD = 7.5) | M = 27.7 (SD = 8.3) |

Procedure

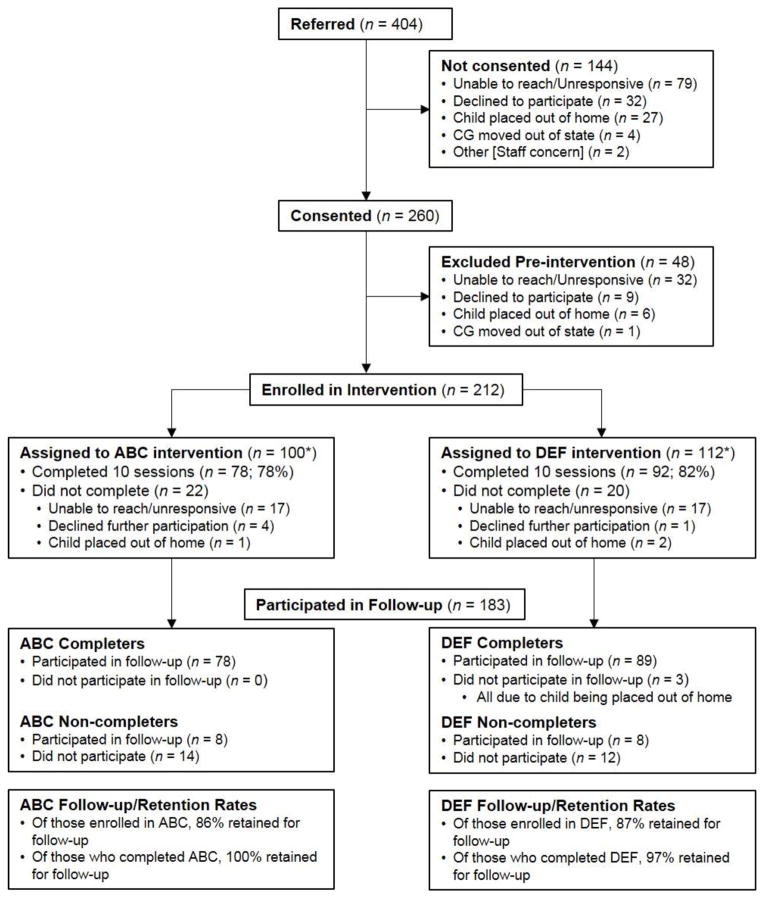

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram is presented in Figure 1. This figure presents a breakdown of the sample across different phases of the randomized clinical trial, including referral/consent, pre-intervention, randomization and enrollment in intervention, and post-intervention.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram. *We report numbers of children enrolled in ABC (n = 100) and DEF (n = 112) following completion of pre-intervention baseline visits. However, participants were randomly assigned to group upon consenting (N= 260; ABC n = 129, DEF n = 131), at which time the intervention group sample sizes were more similar. Follow-up numbers include participants seen for any post-intervention visits. More specific information is provided in Method section.

Participant recruitment

Parents and children were referred to the study following CPS involvement. Caseworkers within agencies contracted by CPS were encouraged to refer families to the study. There were no specific inclusionary criteria beyond CPS involvement, except that children were required to be less than 2 years old at the time of referral and living with their biological parents. When parents were referred, research staff initially contacted them by phone to describe the research protocol and the parent training sessions. If the parents were interested, a researcher visited the parent in the home to review the procedures in more detail and obtain consent.

Pre-intervention and post-intervention research assessments

Approval for the conduct of this research was obtained from the (university deleted to allow blind review) Institutional Review Board. After consent, parents were randomly assigned to receive either the Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC) intervention or a control intervention (Developmental Education for Families: DEF). A total of 260 children were randomly assigned to an intervention group (129 to ABC; 131 to DEF). Of these, 212 children (100 in ABC; 112 in DEF) were enrolled in the intervention phase of the study, following completion of pre-intervention research visits. Reasons for exclusion prior to enrollment in the intervention included: difficulty contacting for pre-intervention research visits, child being removed from parental care, and family moving from the area (See Figure 1). The intended schedule for follow-up included a post-intervention home visit approximately one month after the intervention, and yearly post-intervention research visits around the time of the child’s birthday. Efforts were made to conduct research visits with children during the follow-up phase even if families did not complete the intervention.

Outcome data for the present study were collected during one of two post-intervention visits that occurred when children were approximately 24- to 36-months old. 183 children were retained for the follow-up phase of the study, with 117 participating in the outcome assessment of negative affect regulation. Data for the present study were not available for the remaining 66 children for multiple reasons, including: the family was not able to be reached within the window of the 24- to 36-month post-intervention visit (n = 40), the family only partially completed the measures at this time-point (i.e., completed one visit, but not the other at which the assessment of interest would have occurred, n = 12), experimenter/equipment error (e.g., task broken, experimenter did not conduct assessment, video not recorded, n = 13), or the child was too developmentally-delayed for the task (n = 1).

Interventions

Parents were randomly assigned to one of two interventions. In both interventions, sessions were implemented by parent coaches with strong interpersonal skills and past experience working with children. Parent coaches for both interventions were a mix of bachelor- and master’s-level and received similar supervision. The experimental and control intervention were comparable in structure, frequency, and duration. Both consisted of 10 training sessions, were based on structured manuals, and sessions were conducted in the families’ homes. Children ranged from 3.4 months to 25.8 months old (M = 13.4, SD = 6.3) at the completion of the intervention.

Experimental intervention

Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up Intervention (ABC)

The ABC intervention was designed to help parents engage in synchronous interactions with their children, to provide nurturing care in response to child distress, and to avoid frightening behavior. These three targets were intended to enhance children’s ability to develop secure and organized attachments, to develop normative cortisol production, and to develop the ability to regulate emotions effectively (Dozier, Bernard, & Meade, in press)

Although session content was guided by a manual, the parent coach’s primary role was to provide “in the moment” feedback about the parent’s interactions with his or her child (Bernard, Meade, & Dozier, in press). Throughout all sessions, the parent coach observed the parent’s behavior and made comments on behaviors that relate to the intervention targets. For the most part, these comments were positive in nature, describing how the parent behaved in line with an intervention target and how this behavior is likely to support the child’s development. At other times, the parent coach made suggestions as a way to scaffold the parent’s behavior, orto gently challenge the parent when he or she behaves in a non-synchronous, non-nurturing, or frightening way. This frequent “in the moment” feedback focused attention on the target behaviors, which was expected to enhance the parent’s understanding of the content and support the parent in practicing the target behaviors. Along with “in the moment” comments, parent coaches provided video feedback to highlight parents’ strengths, challenge weaknesses, and celebrate changes in behaviors.

Target behaviors were presented sequentially across the first 6 sessions of the intervention, with sessions 1 and 2 focused on providing nurturance when children are distressed, sessions 3 and 4 focused on behaving in synchronous ways (or following the child’s lead with delight), and sessions 5 and 6 focused on avoiding intrusive and frightening behavior. Despite session-specific topics, these targets were addressed across sessions through frequent “in the moment” commenting whenever opportunities arose. Sessions 7 through 10 were further tailored to address the needs of each parent. In sessions 7 and 8, the parent coach discussed how the parent’s own attachment experiences may influence the parent’s current interactions with their children. In particular, the parent coach helped the parent identify possible “voices from the past” that may interfere with responding sensitively to their children’s distress, interacting synchronously with their children, and avoiding intrusive and frightening behaviors. Sessions 9 and 10 help consolidate gains made through the prior sessions and celebrate change.

Control intervention

Developmental Education for Families (DEF)

The DEF intervention was designed to enhance motor, cognitive, and language skills. It was adapted from a home-visiting program that was previously shown to be effective in enhancing intellectual functioning (Brooks-Gunn, Klebanov, Liaw, & Spiker, 1993; Ramey, McGinness, Cross, Collier, & Barrie-Blackley, 1982; Ramey, Yeates & Short, 1984). Components that targeted parental sensitivity were removed to keep the interventions distinct.

Measures

Tool task

The Tool Task (Matas, Arend, & Sroufe, 1978) is a parent-child interaction procedure designed to assess children’s emotion expression during a challenging task. This assessment was conducted when the children were approximately 24 to 36 months old (M = 26.6, SD = 3.5), which ranged from 1.0 month to 27.2 months (M = 12.5, SD = 6.6) following the final intervention session. The majority of children (approximately 62%) participated in the Tool Task procedure more than 12 months following the final intervention session.

During the Tool Task assessment, a researcher presented three problem-solving tasks to the parent and child, and videotaped their interaction for later coding. In each task, a small toy (e.g., ball, small car) was visible inside a clear Plexiglas container but could only be retrieved by the child if he or she used a tool in a specific way. The tasks increased in difficulty, and the final two tasks were intended to be too difficult for a young child to solve without help. The first problem was designed to be simple: removing a toy from a tube using a stick. The other two problems were presented in the order of increasing difficulty: putting two sticks end to end in order to retrieve a toy from a tube; and retrieving a car from a plexiglass box in a multi-step task.

At the beginning of the procedure, the researcher explained to the parent that the tasks were too difficult for most young children to solve by themselves. The researcher instructed the parent to allow the child to attempt each task by him or herself for a few minutes, and then to give the child “any assistance that you think he (or she) needs.”

For the current study, videotapes were coded using the Revised Manual for Scoring Mother Variables in the Tool-Use Task (Sroufe, Matas, Rosenberg, & Levy, 1980) on the following scales: anger, anger towards parent, and global sadness/anger. The 6-point anger scale assessed the degree of anger expressed by the child, with lower scores reflecting no signs of anger, and higher scores reflecting angry attitudes or tantrums that predominated throughout the tasks. Scores on the anger scales ranged from 1 to 6 (M = 1.96, SD = 1.35). The 7-point anger toward parent scale assessed the degree to which the child showed anger, dislike, or hostility toward the parent. Low scores reflected the absence of both overt and covert signs of anger, and high scores reflected repeated and overt anger towards the caregiver. Scores on the anger toward parent scale ranged from 1 to 7 (M = 1.59, SD = 1.03). The 4-point global sadness/anger scale assessed general negative affect, with lower scores reflecting neutral or positive affect throughout, and higher scores reflecting predominant negative affect. Scores on the global sadness/anger scale ranged from 1 to 4 (M = 1.52, SD = 0.86).

Coders were undergraduate and graduate student research assistants who were blind to other study information. Coders were trained by a senior graduate student. They established acceptable levels of inter-rater reliability on a set of training videotapes prior to coding for the present study. Twenty-one percent of the tapes were double coded to assess reliability. The Spearman correlation for inter-rater reliability was 0.90 for anger, 0.65 for anger toward caregiver, and 0.62 for global sadness/anger. For cases that were double-coded, averaged scores between the two coders were used in analyses.

Variables for analysis were created by first transforming the scale scores into z scores. The scales were highly correlated (with correlations ranging from 0.71 to 0.79) and thus combined to yield a composite score of negative affect expression. If group differences emerged for this composite scale, we planned to conduct analyses separately for the subscales.

Results

Preliminary results

Children randomly assigned to the ABC intervention did not differ significantly from children assigned to the DEF intervention with regard to age at enrollment, age at Tool Task, gender, or minority status. Similarly, there were no group differences in parent age, parent education, or parent minority status.

Primary results

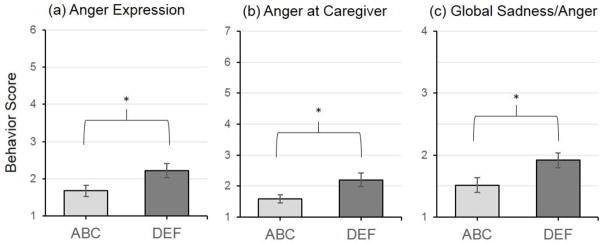

Differences in the negative affect composite variable were examined through analyses of variance, with intervention group as the independent variable and negative affect composite as the dependent variable in the first analyses. As predicted, children in the ABC group showed lower levels of negative affect expression compared to children in the control intervention, F(1, 115) = 5.04, p < .05, which represented a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.42). To further explore the differences in groups, analyses were conducted for each of the three subscales comprising the composite. Children in the ABC group displayed lower levels of anger, F (1,115) = 4.69, p < 0.05 (Cohen’s d = 0.40), lower levels of anger towards parent, F (1,115) = 5.35, p < 0.05 (Cohen’s d = 0.43), and lower levels of global anger/sadness, F (1, 115) = 5.66, p < 0.05 (Cohen’s d = 0.44), compared to children in the control intervention (See Figure 2). All of these findings held when one child of each sibling pair (n = 5) were excluded from analyses. As described above, there was a wide range in time between the intervention and the emotion expression outcome assessment. Within the ABC intervention group, the correlations between time since the intervention and each of the negative affect scores were non-significant.

Figure 2.

Intervention effects on negative affect subscale scores. *p < .05.

Our analyses reflected a conservative intent-to-treat approach, with all children included who provided post-intervention data regardless of whether or not the parent completed the intervention. There were 8 children included whose parents did not complete the full 10 sessions of their respective interventions (DEF non-completers n = 6, ABC non-completers n = 2); findings held for the effect of intervention group on the negative affect composite and individual subscales when these non-completers were excluded.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that a relatively brief parenting program can change children’s expression of negative affect. CPS-referred children in the ABC intervention group showed lower rates of negative affect expression during a series of challenging tasks than children in the control intervention. ABC children showed less anger towards their parents and less anger more generally than children in the control intervention group. Given the prediction from Calkins and colleagues (Blandon et al., 2010; Calkins & Keane, 2009) that problems regulating negative affect among toddlers heighten risk for both externalizing problems and internalizing problems, ABC effects on early emotion expression may have implications for children’s developmental trajectories.

Infants and young children are especially dependent upon parents for help regulating affect, physiology, and behavior. Children who experience parental maltreatment show difficulties in coping with arousal, perhaps because they lack a partner who can help them develop their regulatory capabilities. Such children are therefore likely to develop problems learning to regulate affect independently (Calkins, 1994; Cole, Zahn-Waxler, & Smith, 1994). The ABC intervention aimed to help CPS-referred parents behave in synchronous and nurturing ways with their children, which appears to have supported children’s development of more effective regulation of emotion expression.

Parenting interventions for older children have been effective in reducing negative emotion expression (Domitrovich, Cortes, & Greenberg 2007; Izard, Trentacosta, King, & Mostow, 2004). Two school-based interventions, Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS) and Emotion Course (Domitrovich et al., 2007; Izard et al., 2004) found increased emotion knowledge skill, lower growth in negative emotion expression, and increased social competence among children who received the interventions compared to children who did not receive the interventions. These studies targeted children who experienced a form of early adversity (low income), suggesting that early intervention can have positive effects on emotional and behavioral development for children facing early risks. The ABC intervention focuses on infant and toddlers exposed to both CPS-involvement and low income, extending these promising findings of effective intervention to a younger population of children. In previous studies, the ABC intervention has proven effective in helping children develop organized attachments and develop more normative regulation of cortisol (Bernard et al., 2012; Dozier et al., 2006). The present study extends these findings to emotion expression.

Intervention studies, such as the present study, provide a strong test of models of developmental psychopathology—allowing us to manipulate parenting and examine how it influences trajectories. Although beyond the scope of the present study design, future research could parse the specific parenting behaviors that were targeted through ABC. Identifying specific mechanisms by which the intervention worked can help efforts to refine and tailor parenting interventions for children in need.

This study has several methodological strengths, including the randomized design, high-risk community sample of families identified by the child welfare system, and use of observational assessment of the outcome variable. There were also several limitations. First, we did not have access to records regarding children’s histories of maltreatment and other early risk factors. Thus, we were not able to report on detailed information about children’s early experiences, or examine whether differences in risk (e.g., substantiated vs. unsubstantiated neglect) moderated the effectiveness of the intervention. Relatedly, there was a large proportion of families that were referred to the study that did not enroll. To better understand for whom the ABC intervention is effective, it will be important in future studies to examine differences between families who decline to participate and families who complete the intervention. Second, we did not have a pre-intervention assessment of emotion expression because children were too young at pre-intervention to allow such an assessment. Thus, we were not able to examine change over time in emotion expression from pre- to post-intervention. Also, we did not have data from a low-risk comparison group, preventing us from comparing levels of negative affect expression to what would be expected for typically developing children. Finally, the Tool Task is not a clinical measure of emotion expression, and therefore we did not have standards to which we could compare the CPS-referred children. Future work should focus on exploring the clinical implications of these varying levels of emotion expression. Nonetheless, these results point to powerful effects on emotion expression for a brief time-limited intervention implemented in infancy.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Numbers R01MH052135, R01MH074374, and R01MH084135 from the National Institute of Mental Health to the fourth author.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alink LR, Van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Mesman J, Juffer F, Koot HM. Cortisol and externalizing behavior in children and adolescents: Mixed meta-analytic evidence for the inverse relation of basal cortisol and cortisol reactivity with externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychobiology. 2008;50:427–450. doi: 10.1002/dev.20300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Butzin-Dozier Z, Rittenhouse J, Dozier M. Cortisol production patterns in young children living with birth parents vs. children placed in foster care following involvement of child protective services. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164:438–443. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Dozier M, Bick J, Lewis-Morrarty E, Lindhiem O, Carlson EA. Enhancing attachment organization among maltreated children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Child Development. 2012;83:623–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Meade EB, Dozier M. Targeting sensitivity in an attachment-based intervention: A tribute to Mary Ainsworth. Attachment and Human Development. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2013.820920. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandon AY, Calkins SD, Keane SP. Predicting emotional and social competence during early childhood from toddler risk and maternal behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:119–132. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK, Liaw F, Spiker D. Enhancing the development of low-birthweight premature infants: Changes in cognition and behavior over the first three years. Child Development. 1993;64:736–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AM, Fitzgerald MM, Shipman K, Schneider R. Children’s expectations of parent–child communication following interparental conflict: Do parents talk to children about conflict? Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:407–412. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9095-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD. Origins and outcomes of individual differences in emotion regulation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59(2/3):53–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Keane SP. Developmental origins of early antisocial behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:1095–1109. doi: 10.1017/S095457940999006X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Smith CL, Gill KL, Johnson MC. Maternal interactive style across contexts: Relations to emotional, behavioral and physiological regulation during toddlerhood. Social Development. 1998;7:350–369. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Martin SE, Dennis TA. Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development. 2004;75:317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Zahn-Waxler C, Smith KD. Expressive control during a disappointment: Variations related to preschoolers’ behavior problems. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:835–846. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.30.6.835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr C, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:87–108. doi: 10.1017/S09545794099990289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Mullins MJ, McAllister RA, Atkinson E. Attributions, affect, and behavior in abuse-risk mothers: A laboratory study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:21–45. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00510-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Rhodes T. Aggression in young children with concurrent callous- unemotional traits: Can the neurosciences inform progress and innovation in treatment approaches? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 2008;363:2567–2576. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Mitchell J, Strandberg K, Auerbach S, Blair KA. Parental contributions to preschoolers’ emotional competence: Direct and indirect effects. Motivation and Emotion. 1997;21:65–86. doi: 10.1023/A:1024426431247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Wolff MS, van IJzendoorn MH. Sensitivity and attachment: A meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Development. 1997;68:571–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb04218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domitrovich CE, Cortes RC, Greenberg MT. Improving young children’s social and emotional competence: A randomized trial of the preschool “PATHS” curriculum. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2007;28(2):67–91. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Manni M, Gordon MK, Peloso E, Gunnar MR, Stovall-McClough KC, Eldreth D, Levine S. Foster children’s diurnal production of cortisol: An exploratory study. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11:189–197. doi: 10.1177/1077559505285779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Meade EB, Bernard K. Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up: An intervention for parents at risk of maltreating their infants and toddlers. In: Timmer S, Urquiza A, editors. Evidence-based approaches for the treatment of child maltreatment. New York, NY: Springer; pp. 43–60. (In press) [Google Scholar]

- Drake B. Unraveling “unsubstantiated. Child Maltreatment. 1996;1:261–271. doi: 10.1177/1077559596001003008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, Jonson-Reid M, Way I, Chung S. Substantiation and recidivism. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8:248–260. doi: 10.1177/1077559503258930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy BC. Parents’ reactions to children’s negative emotions: Relations to children’s social competence and comforting behavior. Child Development. 1996;67:2227–2247. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Marshall DB, Coghlan L, Brummel S, Orme M. Causes and consequences of the substantiation decision in Washington State child Protective Services. Children and Youth Services Review. 2002;24:817–851. doi: 10.1016/S0190-7409(02)00241-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson MF, Egeland B, Pianta R. The effects of maltreatment on the development of young children. In: Cicchetti D, Carlson V, editors. Child maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1989. pp. 647–684. [Google Scholar]

- Field T. The effects of mother’s physical and emotional unavailability on emotion regulation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59:208–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel A. Social play, positive affect, and coping skills in the first 6 months of life. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 1982;2(3):53–65. doi: 10.1177/027112148200200309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano PA, Keane SP, Calkins SD. Maternal behaviour and children’s early emotion regulation skills differentially predict development of children’s reactive control and later effortful control. Infant and Child Development. 2010;19:333–353. doi: 10.1002/icd.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Vazquez DM. Low cortisol and a flattening of expected daytime rhythm: Potential indices of risk in human development. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:515–538. doi: 10.1017/S0954579401003066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer MA. Hidden regulators in attachment, separation, and loss. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59:192–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey J, Marshal J, English D, Knight E, Lau A, Dubowitz H, Kotch JB. Defining maltreatment according to substantiation: Distinction without a difference? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:479–492. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE, Trentacosta CJ, King KA, Mostow AJ. An emotion-based prevention program for Head Start children. Early Education & Development. 2004;15:407–422. doi: 10.1207/s15566935eed1504_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M, Drake B, Kim J, Porterfield S, Han L. A prospective analysis of the relationship between reported child maltreatment and special education eligibility among poor children. Child Maltreatment. 2004;9:382–394. doi: 10.1177/1077559504269192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Antecedents of self-regulation: A developmental perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:199–214. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.18.2.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer ES, Shields AM, Cortina KS. Parental emotion coaching and dismissing in family interaction. Social Development. 2007;16:232–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00382.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Main M. Attachment: Overview, with implications for clinical work. In: Goldberg S, Muir R, Kerr J, editors. Attachment theory: Social, developmental and clinical perspectives. Hillsdale NJ: Analytic Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Matas L, Arend RA, Sroufe LA. Continuity of adaptation in the second year: The relationship between quality of attachment and later competence. Child Development. 1978;49:547–556. doi: 10.2307/1128221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moss E, Cyr C, Bureau JF, Tarabulsy GM, Dubois-Comtois K. Stability of attachment during the preschool period. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:773–783. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Young children develop in an environment of relationships. Working Paper No 1. 2004 Retrieved from http://www.developingchild.net.

- Ramey CT, McGinness GD, Cross L, Collier AM, Barrie-Blackley S. The Abecedarian approach to social competence: Cognitive and linguistic intervention for disadvantaged preschoolers. In: Borman K, editor. The social life of children in a changing society. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1982. pp. 14–174. [Google Scholar]

- Ramey CT, Yeates KO, Short EJ. The plasticity of intellectual development: Insights from preventative intervention. Child Development. 1984;55:1913–1925. doi: 10.2307/1129938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC. Relations between social contingency in mother-child interaction and 2- year-olds’ social competence. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:850–859. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.32.5.850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Bales SN. Science does not speak for itself: Translating child development research for the public and its policymakers. Child Development. 2011;82:17–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipman KL, Schneider R, Fitzgerald MM, Sims C, Swisher L, Edwards A. Maternal emotion socialization in maltreating and non-maltreating families: Implications for children’s emotion regulation. Social Development. 2007;16:268–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00384.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Stifter CA, Donelan-McCall N, Turner L. Mothers’ regulation strategies in response to toddlers’ affect: Links to later emotion self-regulation. Social Development. 2004;13:42–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2004.00256.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Matas L, Rosenberg D, Levy A. Revised Manual for Scoring Mother Variables in the Tool-Use Task. University of Minnesota; 1980. Unpublished document. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA, Meyer S. Socialization and emotion regulation in the family. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. Vol. 249. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Schuengel C, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Disorganized attachment in early childhood: Meta-analysis of precursors, concomitants, and sequelae. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:225–250. doi: 10.1017/S0954579499002035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winberg J. Mother and newborn baby: Mutual regulation of physiology and behavior- A selective review. Developmental Psychobiology. 2005;47:217–229. doi: 10.1002/dev.20094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]