Abstract

This study focused on characteristics of the family environment that may mediate the relationship between disaster exposure and the presence of symptoms that met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for symptom count and duration for an internalizing disorder in children and youth. We also explored how parental history of mental health problems may moderate this meditational model. Approximately 18 months after Hurricane Georges hit Puerto Rico in 1998, participants were randomly selected based on a probability household sample using 1990 US Census block groups. Caregivers and children (N=1,886 dyads) were interviewed with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children and other questionnaires in Spanish. Areas of the family environment assessed include parent-child relationship quality, parent-child involvement, parental monitoring, discipline, parents’ relationship quality and parental mental health. SEM models were estimated for parents and children, and by age group. For children (4–10 years old), parenting variables were related to internalizing psychopathology, but did not mediate the exposure-psychopathology relationship. Exposure had a direct relationship to internalizing psychopathology. For youth (11–17 years old), some parenting variables attenuated the relation between exposure and internalizing psychopathology. Family environment factors may play a mediational role in psychopathology post-disaster among youth, compared to an additive role for children. Hurricane exposure had a significant relation to family environment for families without parental history of mental health problems, but no influence for families with a parental history of mental health problems.

Keywords: natural disaster, family environment, mental health, internalizing symptoms, Latino

Warm, caring parenting behaviors tend to be protective against mental health (MH) problems (Greenberger & Chen, 1996; Greenberger, Chen, Tally & Dong, 2000); whereas, parental conflict and parent-child conflict are risks for problem behaviors (e.g., Chen, Greenberger, Lester, Dong, & Guo, 1998; Greenberger & Chen, 1996). When disasters strike, normally confident and protective adults may show terror, shock, and fear, which can affect parents’ relationships with each other and with their children. In their comprehensive review, Bonanno, Brewin, Kaniasty, and La Greca (2010) found that across many studies employing a range of samples, measurement strategies, and methodologies, greater parental distress post-disaster was related to higher levels of symptoms in children. They note that this was due in part to shared trauma exposure, but also because of a potential influence of disaster-related stressors on family dynamics, which needs further research. Stress in the aftermath can be prolonged for more severely exposed families, as parents cope with demands associated with recovery and reconstruction, such as rebuilding homes or relocating, as well as social disruptions and financial losses.

In this study, we assessed how disaster exposure affected the family environment and how this related to children and youth meeting the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders -4th edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) criteria for full symptom count and duration for an internalizing disorder at around 18 months post-disaster. Participants may or may not have met the functional impairment criteria, hence our specification of meeting diagnostic symptom criteria. The study aims were guided by the well-known conceptual model of children’s post-disaster functioning (Silverman & La Greca, 2002; Vernberg, 2002), and the Family Stress Model (FSM; Conger, Elder, Lorenz, Simons, & Whitbeck, 1994), which provided a possible explanation of how external stressors, such as disasters, can affect child MH through the distress it causes in parents.

In our study, we explored if aspects of the family environment (i.e., discipline, parental monitoring, parent-child relationship quality, parent-child involvement, and parents’ relationship quality) mediated the exposure-psychopathology relationship. As post-disaster parental distress is a known risk for maladjustment in the child (Norris, Friedman, Watson, Byrne, & Kaniasty, 2002), we explored if parental history of MH problems moderates our mediation model of the post-disaster family environment. A strength of this study is that assessing whether DSM-IV diagnostic symptom criteria (symptom count and duration) was met provided a reliable standard for determining the presence or absence of psychopathology, compared with sometimes arbitrary and varying symptom cut off points used in some disaster studies (Bonanno et al., 2010). Also, many disaster studies have used convenience samples rather than representative samples, which may result in an overestimation of the rate of psychopathology (Bonanno et al., 2010). In the following sections, we describe the conceptual models and extant research that has led to our hypotheses.

Conceptual Models of the Influence of the Recovery Environment

The model presented by Vernberg, La Greca, and colleagues (Silverman & La Greca, 2002; Vernberg, 2002) proposed that aspects of the disaster experience present adaptational challenges to children, and that efforts to cope with these challenges shape the persistence of MH symptoms. Characteristics of the post-disaster recovery environment influence child efforts to cope with the disaster. Family factors are proposed to play important roles in recovery, but most child-focused disaster research has been conducted with relatively limited measurement of the family environment (Bonnano et al., 2010; Kilmer & Gil-Rivas, 2010).

Although not specific to the impact of disasters, the FSM (Conger et al., 1994) described how life stressors such as poverty could affect child MH. The FSM proposed that life stressors affect parental MH, which negatively affects their parenting behavior, that in turn increases a child’s risk for MH problems. Both stress from general life events and stress related to the demands of the parenting role (parenting stress) can influence parenting behavior and child adjustment (Deater-Deckard, 1998). Parenting stress represents a complex interplay of the demands of parenting, the parent’s psychosocial adjustment, the quality of the parent-child relationship, and the child’s psychosocial adjustment (Deater-Deckard, 1998). Parenting stress can vary by sibling, as the child perceived as more demanding can generate more parenting stress (Deater-Deckard, 1998). Thus, there is a bi-directional influence between parent and child on parenting stress. Stressful life events have been shown to affect youth psychosocial adjustment, in part, through their negative effect on the quality of interactions between parents and their children (Kelly & Emery, 2003). This has been supported across cultures (Dmitrieva, Chen, Greenberger, & Gil-Rivas, 2004). The FSM has recently been applied to disasters (e.g., Scaramella, Sohr-Preston, Callahan, & Mirabile, 2008), and was related to variation in children’s MH for both disaster exposed and unexposed groups. We examined how parental history of MH problems influenced our family environment indicators, which includes involvement and relationship quality.

Family Influences on Children’s Post-Disaster Mental Health

Prior research with the sample used in this study has shown increased risk of internalizing disorders in children and youth approximately 18 months post-disaster (Felix et al., 2011). Although disaster-related distress tends to decrease over time (Norris et al., 2002), prolonged difficulties in the recovery environment may produce more persistent symptoms (Weems et al. 2010). Until recently, few child studies have examined the post-disaster family environment. As such, studies are not consistent on the aspects of the family environment measured.

Disasters can lead to increased family conflict, as families deal with the stresses associated with recovery and rebuilding. Interparental conflict has been connected to post-disaster posttraumatic stress symptoms in children (Wasserstein & La Greca, 1998). Caregiver-child conflict, caregiver unavailability to talk about the hurricane, and children’s perceptions of caregiver’s hurricane-related distress, was related to children’s post-disaster traumatic stress symptoms beyond what was explained by hurricane exposure alone (Gil-Rivas, Kilmer, Hypes, & Roof, 2010). However, in another study of parent-child factors affecting MH in Hurricane Katrina survivors, parenting behaviors did not add to the variance accounted for above and beyond hurricane exposure amongst those displaced after the storm (Kelley et al., 2010). This coupled with the lack of disaster studies on the role of parental discipline and monitoring on child and youth MH indicate a need for further research.

One necessary component of effective parenting is parental monitoring, which involves attention to and tracking of the whereabouts, activities, and adaptations of the child (Dishion & McMahon, 1998). Likewise, discipline is an essential part of parenting, and different styles of discipline are related to child adjustment and behavior (Baumrind, 1966). Inconsistent discipline and lack of parental monitoring were related to problem behavior (Dishion & McMahon, 1998; Patterson & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1984) in non-disaster studies. Likewise, research is beginning to show a link between harsh, ineffective discipline and internalizing symptoms (Laskey & Cartwright-Hatton, 2009). Thus, discipline style and parental monitoring should begin to be explored in disaster research, especially since discipline and monitoring are potentially modifiable targets for intervention (Dishion & McMahon, 1998). It is possible that the quality of parental discipline and parents’ ability to monitor their child may decrease following a disaster because of the stress and time demands association with recovery and rebuilding. This could be an addressable factor that differentiates children and youth who are resilient post-disaster to those at greater risk for psychopathology. We examined how hurricane exposure related to discipline and monitoring, and if this was associated with internalizing psychopathology. We explored the influence of frequency of use of discipline strategies that are positive (explaining what the child did wrong, removal of privileges) and negative (yelling, hitting). The behaviors characterized as negative discipline, such as hitting, if frequent enough, have been linked to increases in child aggressive behavior (e.g., Taylor, Manganello, Lee, & Rice, 2010). It is imperative that child-focused disaster research begins to explore how these essential components of parenting are influenced by a disaster and how this relates to child and youth MH.

Parental History of Mental Health Problems as a Moderator of Family Environment

Children whose parents were highly distressed following natural disasters appeared to have a greater number of disaster-related problems than children whose parents were not so distressed (Gil-Rivas, Silver, Holman, McIntosh, & Poulin, 2007; Norris et al., 2002; Spell et al., 2008). MH problems can influence parents to either over- or under-estimate children’s reaction to disaster (Silverman & La Greca, 2002). Indeed, parental MH or post-disaster distress can affect their ability to monitor their children, interpret cues and indicators of children’s emotional and behavioral functioning, and their ability to be responsive to children’s needs (Gil-Rivas et al., 2007). We expected that parental history of MH problems would moderate the relationship of hurricane exposure to family environment to child and youth internalizing psychopathology.

Current Study on Risk and Protection Within the Recovery Environment

In September, 1998, Hurricane Georges struck PR as a category 3 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. A category 3 hurricane rating indicates sustained winds of 111–130 mph, that devastating damage will occur, and a high risk of death and injury (National Hurricane Center, n.d.). Indeed, many communities reported property damage, 416 government shelters were opened for approximately 28,000 persons, 700,000 persons were without water and 1,000,000 had no electricity for some time (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998). An epidemiological study of psychopathology in a random sample of the island’s population of children and adolescents had already been planned and funded when Hurricane Georges made landfall. The Hurricane Georges disaster provided the opportunity to study how aspects of the family environment influenced the disaster exposure-psychopathology relationship. We assessed youth and parent report of discipline, parental monitoring, parents’ relationship quality, and whether the child met DSM-IV diagnostic symptom criteria for an internalizing disorder. Parents provided information on their own history of MH problems and their relationship quality with their child. Youth provided information on parent-child involvement. Prior research with this sample indicated that age had a relationship to internalizing disorder, in that the influence of demographic characteristics on psychopathology varied by age and there was an exposure by age interaction for youth (Felix et al., 2011). Given the large developmental span covered in the sample, and the potential for different patterns of relationships among age groups, we separated children (ages 4–10 years) and youth (ages 11–17 years) to explore potential differences. In addition, methodologically, this was a sensible division, as only youth age 11 years and older were interviewed in addition to the parent. We used this information to address the following hypotheses.

-

H1

Family environment will mediate the relationship between disaster exposure and meeting symptom criteria for an internalizing disorder.

-

H2

Parental history of mental health problems will moderate the relationship between exposure, family environment, and meeting symptom criteria for an internalizing disorder.

Methods

Participants

This study used the island-wide epidemiological dataset collected by Canino and colleagues (2004). Children aged 4 to 17 years were selected from a probability household sample that included four strata: PR’s health reform areas, urban vs. rural areas, participant age, and participant sex using US 1990 Census’ block groups as primary sampling units. These units were classified according to economic level and size, grouped into block clusters, and further classified as urban or rural. Three hundred block clusters were randomly selected and then divided into two random replicates. A household was selected for inclusion in the study if it had children between the ages of 4 to 17 years. One child was selected at random from each household using Kish (1965) Tables adjusted for age and gender. Out of 2,102 eligible households, 1,890 children and 1,897 primary caretakers were interviewed forming 1,886 parent-child dyads for total completion rate of 90.1% for parent-child dyads.

Interviews took place from September 1999 to December 2000 (50% completed by late May, 2000). The sample was weighted to represent the general population in the year 2000, which corrected for differences in the probability of selection because of the sampling design and adjusted for no response. Thus, the distribution by sex and age of the sample obtained is similar to that of the 2000 US census of the PR population, with 51.1% male, 50.2% age 4–10 years and 49.8% age 11–17 years. Over half the sample perceived they “lived well” (51.4%), 33.7% indicated they lived “check to check,” and 15.0% said they “lived poorly.” The final sample of 1,886 children and youth constituted a sampling fraction of approximately 2.2 per 1000 children in the population. Prior research with this sample indicated PTSD, Panic Disorder, and Dysthymia were the least common diagnoses (< 1%), whereas Social Phobia, Major Depression, Generalized Anxiety, and Separation Anxiety were more common (see Felix et al., 2011). Pre-hurricane estimates of prevalence rates from an epidemiological study of DSM-III diagnoses in children and youth age 6–16 years found rates of depression/dysthymia at 8.7%, separation anxiety at 6.8%, and simple phobias at 3.9%, if excluding impairment criteria (Bird et al., 1988). Post-hurricane DSM-IV diagnoses estimates, without impairment, include 4.1% for any depressive disorder and 9.5% for any depressive disorder (Canino et al., 2004). In our current study, 11.8% of the sample (9.0% for child; 13.4% for youth) met DSM-IV symptom criteria for an internalizing disorder.

Measures

A multi-stage method was used for cross-cultural adaptation and translation of study measures (Bullinger et al., 1998). The result was a translated version of the instrument that tackles the major dimensions of cross-cultural equivalence: content, semantic, technical, criterion and concept equivalence (Canino & Bravo, 1994; Bravo, Canino, Rubio-Stipec, & Woodbury, 1991; Matías-Carrelo et al., 2003).

Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV)

Last-year DSM-IV disorders were assessed using the latest translation into Spanish of the DISC-IV (Bravo et al., 2001), with parallel youth and parent interview versions. The test-retest reliability of the DISC-IV has been reported in both Spanish and English-speaking clinic samples yielding comparable results (Bravo et al., 2001; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000). In community samples, reports of parents and youth have shown a test-retest reliability ranging between .22–.85 for symptom counts across disorders in English-speaking samples and .29–.88 for different diagnoses in Spanish-speaking samples (Shaffer et al., 2000; Bravo et al. 2001). Procedures for Spanish translation and back translation are documented in the work of Bravo and colleagues (1991; 2001). Children under the age of 11 years were not interviewed with the DISC because there is evidence that their reports would not be reliable (Scwhab-Stone, Fallon, Briggs, & Crowther, 1994). The internalizing disorders assessed for this study were: Social Phobia, Separation Anxiety, Panic Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, PTSD, Major Depressive Disorder, and Dysthymia. Participants were judged to meet DSM-IV symptom criteria for a disorder if they met symptom diagnostic criteria based on either parent or youth report. The symptom diagnostic criteria included meeting the minimum number of symptoms, requirements for type of symptom category for that disorder, and duration requirements for a given disorder. We did not require participants to meet criteria for impairment in order to increase statistical power by increasing sample size to test the primary research hypotheses. As noted by Spitzer and Wakefield (1999), the use of symptom criteria alone results in higher estimates of the prevalence of disorders (compared to the added requirement of clinical significance), but may reduce problems of false negatives that arise when the judgment of clinical significance is added. Shaffer and colleagues (2000) note that meeting diagnostic symptom criteria but not clinical significance is not uncommon in a community sample, especially for anxiety. In sum, for this study, children and youth met DSM-IV diagnostic symptom criteria, without requiring impairment as measured by items on the DISC.

Hurricane Exposure Questionnaire

Questionnaires for caretakers (19 items) and youth (6 items; age 11–17 yrs.) were adapted from earlier disaster studies (Bravo, Rubio-Stipec, Canino, Woodbury, & Ribera, 1990; Norris & Kaniasty, 1992) and modified for children using the La Greca, Silverman, Vernberg, and Prinstein (1996) hurricane exposure questionnaire as a guide. Items assessed direct exposure to the child and to the family as a unit. Items pertaining to child exposure include life threat/loss (physical injury to the child or a significant other, loss of a family member or a person close to him/her), loss of material objects, and child’s disruption of everyday life (separation from family, still living out of home at time of interview). Parents provided information about their exposure to the hurricane (feeling afraid of dying or being hurt, becoming ill or injured during the hurricane) or loss or damage to their home. A continuous measure was developed by summing the counts for specific exposure experiences across the child and family unit, with higher scores indicating more severe exposure (range 0–15). This continuous score was used for the structural equation modeling (SEM) models. A dichotomous measure was also created that divided the sample into those who had no direct exposure experience and those with at least one direct experience of either child or family exposure. This was done to compare exposure groups. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was acceptable at .72.

Family Environment

The diagonal in Table 1 shows the significant, positive correlations of parent and youth report for the measures described below.

Table 1.

Correlations between Family Environment, Exposure, and Internalizing Psychopathology

| Factor name | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth (Age 11–17 years) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| 1. Parent-Child Involvement/Parent-Child Relationship Quality | .23* | .34* | −.20* | .16* | .32* | −.04 | −.05 |

| 2. Positive Discipline | −.18* | .18* | .26* | −.12* | .11* | −.06 | .07* |

| 3. Negative Discipline | −.51* | .29* | .26* | −.36* | −.13* | −.01 | .15* |

| 4. Parents’ Relationship Quality | .26* | .03 | −.20* | .32* | −.16* | −.16* | .15* |

| 5. Parental Monitoring | .31* | .11* | −.13* | .16* | .17* | .01 | −.07* |

| 6. Hurricane Exposure (cont.) | −.07* | −.06 | −.02 | −.12* | −.08* | _ | .07* |

| 7. Internalizing Psychopathology | −.17* | .05 | .16* | −.07 | −.003 | .07* | _ |

|

| |||||||

| Child (Age 4–10 years) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| 1. Parent-Child Relationship Quality | _ | ||||||

| 2. Positive Discipline | −.17* | _ | |||||

| 3. Negative Discipline | −.55* | .24* | _ | ||||

| 4. Parents’ Relationship Quality | .31* | .001 | −.27* | _ | |||

| 5. Parental Monitoring | .32* | .05 | −.10 | .22* | _ | ||

| 6. Hurricane Exposure (cont.) | −.05 | −.03 | .02 | −.002 | −.14* | _ | |

| 7. Internalizing Psychopathology | −.16* | .09* | .07* | −.13* | −.05 | .08* | _ |

Note:

p < .01. For youth sample, the top half of the table shows the correlation matrix for youth report and the bottom half is for parent report. Diagonals show the correlation between the youth and parent report versions.

Parental Monitoring (Patterson & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1984)

This 11-item questionnaire measures the extent of parental supervision and monitoring, with separate versions for children and adults. Items ascertain setting curfews, monitoring friends, supervision, and tracking of the child’s whereabouts after school. Higher scores indicate more monitoring. Scale reliabilities for the original instrument are .54 for White, .70 for African-American, and .72 for Hispanic participants. For this study, α=.64 for parent and α=.66 for youth.

Parental Discipline (Goodman et al., 1998)

This 10-item measure for children and adults assesses discipline style when the youth misbehave. Items measure positive (e.g., removal of privileges, have youth explain what they did wrong) and negative discipline strategies (e.g., yelling, hitting). Higher scores indicate greater use of that discipline type. In this sample, for positive discipline α=.51 for parent and α=.58 for youth, and for negative discipline α=.62 for parent and α=.63 for youth.

Parental Psychopathology Questionnaire (Lish, Weissman, Adams, Hoven, & Bird, 1995)

This 11-item questionnaire, administered to parents, is an adapted version of their Family History Screen for Epidemiological Studies. It specifically inquires about lifetime presence of symptoms of major depression, substance use problems, antisocial behavior, suicide attempts, history of any other serious mental illness or emotional problem, and mental health service utilization. This was dichotomized where ‘no’ equals the absence of any endorsement of the measured mental health symptoms and ‘yes’ indicates at least one of the 11 items was answered affirmatively.

Parent-Child Relationship Quality (Smith & Krohn, 1995)

This 10-item scale measures the parent or primary caretaker’s perception of the affective component of the parent-child relationship, including parent-child warmth, liking, lack of hostility, and sense of parental approval. Higher scores indicate more positive parent-child relationship quality. The estimates of scale reliability range from .76 to .82. For this study, α=.73.

Parent-Child Involvement (Loeber, Farrington, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Van Kammen, 1998)

This is a youth report measure of shared time (e.g. how often is your parent available to do things with you), support (e.g., help you with important decisions), and activities (e.g., play sports or games with you) with their parents or caregivers. Higher scores indicate greater involvement. A 12-item version of this scale has been used in prior research with Puerto Rican youth with good internal consistency (α=.85) (Bird et al., 2006). Internal consistency for the 10-item version used in this study was acceptable (α=.79).

Parents’ Relationship Quality (Marital Harmony and Discord Scale; Sharpley & Cross, 1982)

This is a 6-item short version of Spanier’s Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976). Respondents indicate the extent to which they and their spouse/partner agree on a philosophy of life, work and spend time together, agree on life goals and aims, and discuss and exchange ideas. Parents were also asked whether or not they ever hit each other when they quarrel. Higher scores indicate a more harmonious relationship. There is a 9-item child version that assesses the child’s perception of conflict between parents. For this study, α=.83 for parent and α=.76 for youth, indicating acceptable internal consistency.

Procedures

Informed consent was obtained from the parent; children aged 6–17 years provided assent. The survey was performed from September 1999 through December 2000. The primary caretaker selected for the interview was based on who had close and regular contact with the child for the longest time during the last 6 months and was at least 18 years old (biological mother=89.4%). Many interviews took place in the home of a relative because many houses were destroyed by the hurricane. Different interviewers were used for parent and child, and the interviewers were blind to the results of each other’s interviews. Interviews were audio taped, and 15% were spot checked for quality control purposes.

Analytic Strategy

T-tests were used to compare exposed and non-exposed groups on study variables, to give an indication of how hurricane exposure may affect our study constructs. Correlations by age showed the interrelationships among study variables. Prior research with this sample indicated that age had a relationship to internalizing disorder (Felix et al., 2011). Given the large developmental span covered in the sample, we separated children (ages 4–10 years) and youth (ages 11–17 years) to explore potential differences. We could not divide the sample further due to loss of statistical power (Felix et al., 2011). In addition, methodologically, this was a sensible division, as only youth age 11 years and older were interviewed in addition to the parent. As youths’ perceptions of parent-child relationships were likely to differ from their parents’, as indicated by the low correlations obtained, we analyzed parent and youth report separately.

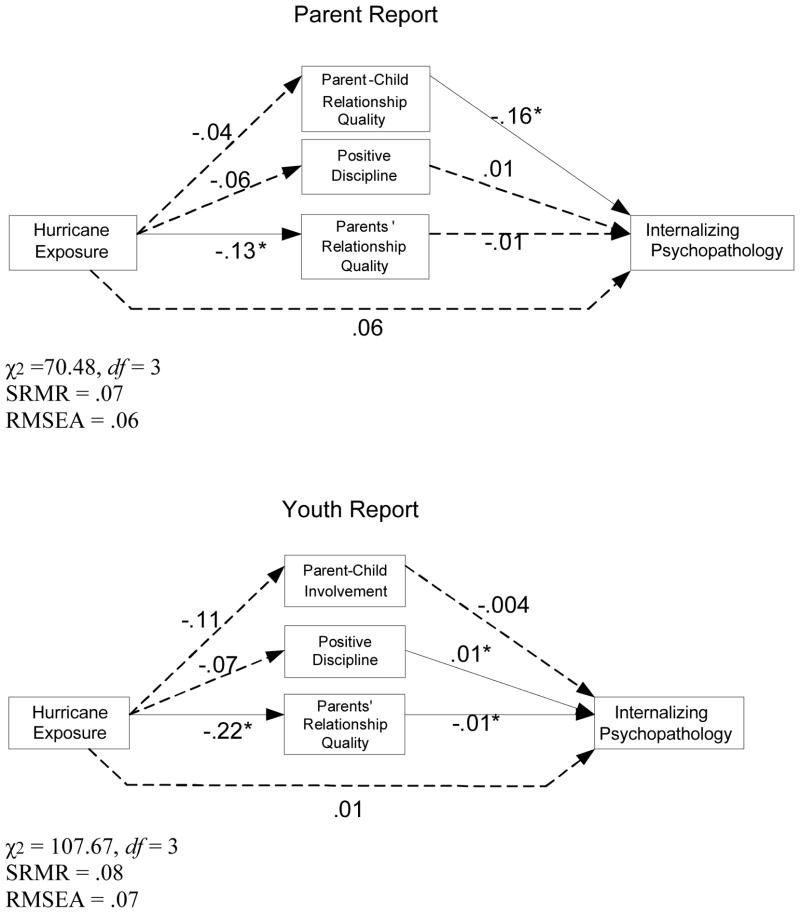

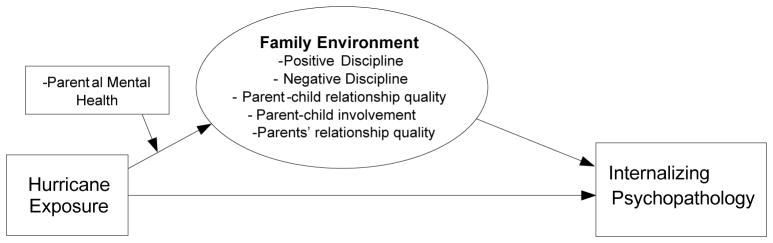

We used SEM to analyze the complex interplay among family environment variables on the relationship between disaster exposure and meeting symptom criteria for an internalizing disorder (see Figure 1). The continuous disaster exposure variable (range=0–15) was used. This method of analysis of disaster exposure has been used in numerous studies and is a well-recognized method of determining the influence of severity of exposure (North & Norris, 2006). Even though a participant may not have had a direct exposure experience as measured in our questionnaire, all were residing in PR when the hurricane struck and experienced indirect exposure. All procedures were performed using Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2003) with weighted data. After preliminary analysis, only those family variables with statistically significant effects on the outcome were retained to achieve a parsimonious model. For evidence of a mediating effect, both the path from a hurricane exposure to a family environment variable and the path from a family variable to internalizing psychopathology should be significant. Standardized coefficients are reported and are useful to determine whether a one standard deviation change in one independent variable produces more of a change in relative position than a one standard deviation change in another independent variable, when both of them are significant. The magnitude of standardized coefficients is not related to the significance of the variable. After exploring our mediation models, we examined the moderating role of history of parental MH problems. We divided the sample based on whether parents had history of MH problems or not as a method for determining moderation for categorical variables (Baron & Kenny, 1986). This is a succinct, straightforward way of exploring and interpreting differences between the groups, versus keeping parental history of MH problems as a continuous variable and computing interaction across all study variables.

Figure 1.

Path Diagram of Hypothesized Model

Model Evaluation and Missing Data

Given the categorical nature of many of our variables, all analyses were based on robust statistics. When data are non-normally distributed, maximum likelihood estimation can produce distorted results (Curran, West, & Finch, 1996). The Satorra-Bentler scaled statistic (S-B χ2) was used because it provides a correction to test statistics and standard errors when data are non-normally distributed. The data model fit was evaluated using the combinational rule recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999): standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). To obtain unbiased estimates of the parameters of interest despite the incomplete data, this study used full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

This study examined how disaster exposure and characteristics of the family environment affect meeting DSM-IV symptom criteria for an internalizing disorder among children and youth. Approximately, 11.8% of the sample met this definition for internalizing psychopathology. A total of 39% of the sample reported no direct exposure to hurricane-related negative events. Of the 61% directly exposed, the mean number of exposure events endorsed was just over two, with a range of 1 to 15. The unexposed group was interviewed an average of five days earlier than the exposed group, which was a statistically significant difference, but unlikely to be clinically meaningful. We explored the interaction of hurricane exposure and time since hurricane on internalizing psychopathology and found that those who were interviewed later were more likely to meet criteria. This was likely because more of the disaster-exposed participants were interviewed later. Given this, we did not control for time since hurricane in our subsequent analysis.

Table 1 shows the correlations among study variables by age group, and for youth by informant (parent report in the bottom half and youth report in the top half). The diagonal shows the correlations between parent and youth report. Parent and youth report were significantly, positively correlated with one another (r =.17–.26). However, as the magnitude of the correlations was small, we analyzed parent and youth report separately. In addition, there were some differences in the pattern of correlations between parent and youth report; for example, the negative correlation between hurricane exposure and parent-child relationship quality was not significant per youth, but was per parent report.

Likewise, there were some age differences, which supported our decision to examine the models separately by age group. For children, positive discipline was positively correlated to internalizing psychopathology, but for youth it varied by informant. Per parent report, there was a positive correlation, but per youth report there was not. Similarly, for children, parents’ relationship quality was negatively related to internalizing psychopathology, but varied for youth by informant (no relation per parent, but a significant, positive relation per youth). For children, hurricane exposure was negatively related to parental monitoring and positively related to internalizing psychopathology. For youth, per parent report, hurricane exposure was significantly negatively related to parents’ relationship quality, parent-child relationship quality, and parental monitoring. Per youth, hurricane exposure was negatively related to only parents’ relationship quality.

The Influence of the Family Environment on Post-Disaster Internalizing Symptoms

Independent-samples t-tests were conducted to compare the hurricane exposed and non-exposed groups on the family environment variables. There were significant differences in scores between groups on parent-child relationship quality and parents’ relationship quality (see Table 2) for both parent and youth report, with the exposed group faring worse. Hurricane-exposed parents also reported less parental monitoring. Also, there was a significant difference between exposed and unexposed children on parental history of MH problems (χ2= (1, 1889) =5.33; p<.05), with the exposed group having a higher percentage of parents with a history of a MH problem. These analyses give support to the potential role of family environment in understanding the exposure-psychopathology relationship.

Table 2.

Comparison of Exposed and Unexposed Children by Family Factors

| Unexposed | Exposed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Parent-Child Involvement/Parent-Child Relationship Quality | ||||

| Parent report* | 35.43 | 3.71 | 34.79 | 4.01 |

| Youth report* | 27.36 | 6.75 | 26.50 | 6.36 |

| Positive Discipline | ||||

| Parent report | 6.72 | 1.69 | 6.58 | 1.73 |

| Youth report | 10.40 | 2.69 | 10.21 | 2.83 |

| Negative Discipline | ||||

| Parent report | 5.65 | 1.67 | 5.73 | 1.71 |

| Youth report | 4.05 | 1.54 | 4.04 | 1.51 |

| Parents’ Relationship Quality | ||||

| Parent report* | 25.20 | 5.07 | 24.36 | 6.01 |

| Youth report* | 22.96 | 3.51 | 22.27 | 3.82 |

| Parental Monitoring | ||||

| Parent report* | 11.36 | 1.28 | 11.10 | 1.50 |

| Youth report | 8.19 | 1.68 | 8.19 | 1.78 |

Note.

Group differences at p< .01.

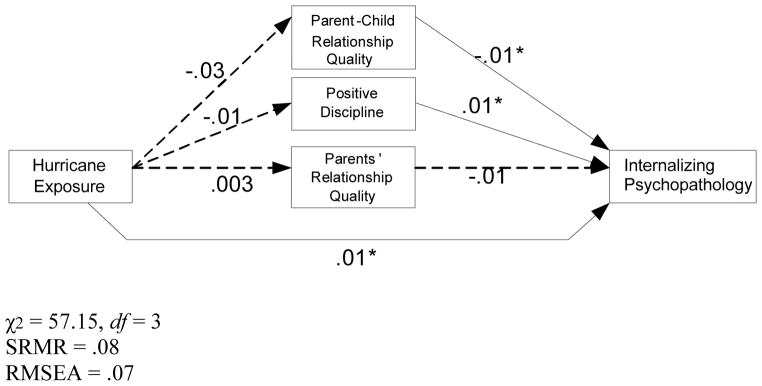

We tested the family environment variables as mediators between hurricane exposure and internalizing psychopathology (see Figure 1). The parameter estimates for the hypothesized models are presented in Figure 2 for children aged 4–10 years and Figure 3 for youth 11–17 years old. The fit of the models was deemed acceptable in terms of SRMR and RMSEA. Parental monitoring and negative discipline are not displayed because of a lack of significant relations to either hurricane exposure or internalizing psychopathology. For children aged 4–10 years, hurricane exposure had a significant, direct effect on internalizing psychopathology. Parent-child relationship quality was negatively related, whereas positive discipline was positively related, to internalizing psychopathology. However, none of the family variables had a significant mediating effect on the exposure-psychopathology relation.

Figure 2.

Final Model of the Influence of the Family Microsystem on the Exposure-Internalizing Psychopathology Relationship for Children Aged 4–10 Years

Figure 3.

Final Models of the Influence of the Family Microsystem on the Exposure-Internalizing Psychopathology Relationship for Youth Aged 11–17 Years

For youth aged 11–17 years, hurricane exposure no longer had a significant direct effect on internalizing psychopathology when the influence of family environment was considered. Rather, hurricane exposure influenced parents’ relationship quality, per both parent and youth report. Other aspects of the family environment that were related to hurricane exposure, internalizing psychopathology, and/or both (suggesting mediation) varied across parents and youth. Per parent report, parent-child relationship quality was significantly, negatively related to internalizing psychopathology, but no other parenting variable was. Per youth report, parents’ relationship quality was a significant, full mediator between hurricane exposure and internalizing psychopathology. In addition, more parental positive discipline was related to increased risk for internalizing psychopathology.

History of Parental Mental Health Problems as Moderator of the Family Recovery Environment

Table 3 shows the results of testing the moderating effect of parent’s history of MH problems on the relation between hurricane exposure, the family environment, and meeting DSM-IV symptom criteria for an internalizing disorder. SRMR and RMSEA values were acceptable across all groups. When comparing our mediation models by parental history of MH problems, we found that hurricane exposure did not have significant relations to internalizing psychopathology for either group, but did have a relationship to some characteristics of the family environment for youth. There were no significant relationships for children. When parents had a history of MH problems, hurricane exposure was not related to the family environment. However, when parents did not have a history of MH problems, for youth only, hurricane exposure did influence the family environment in terms of positive discipline and parents’ relationship quality. In addition, for youth, parent-child relationship quality (parent report) and parent-child involvement (youth report) decreased risk for internalizing psychopathology when parents did not have a MH problem, but were not protective when parents did have a history of MH problems (i.e., no significant relation).

Table 3.

Standardized Parameter Estimates of the Model Testing the Moderating Role of Parent’s Mental Health

| Path | Children 4–10 Years (Parent Report) | Youth11–17 Years (Parent Report) | Youth 11–17 Years (Youth Report) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Has a History of MH Problems | |||

|

| |||

| χ2 (3) = 23.77 SRMR=.08, RMSEA=.08 |

χ2 (3) = 20.38 SRMR=.08, RMSEA=.09 |

χ2 (3) = 27.93 SRMR =.08, RMSEA=.09 |

|

|

| |||

| Hurricane exposure → Internalizing Psychopathology | .08 | .07 | .07 |

| Hurricane exposure → Parent-Child Involvement/Parent-Child Relationship Quality | −.07 | −.11 | .01 |

| Hurricane exposure → Positive Discipline | .02 | .06 | .01 |

| Hurricane exposure → Parents’ Relationship Quality | −.07 | −.10 | −.08 |

| Parent-Child Involvement/→ Internalizing Psychopathology Parent-Child Relationship Quality | −.12 | −.10 | .01 |

| Positive Discipline → Internalizing Psychopathology | .14 | .04 | .20* |

| Parents’ Relationship Quality → Internalizing Psychopathology | −.10 | .05 | −.19 |

|

| |||

| Parent Does Not Have a History of MH Problems | |||

|

| |||

| χ2 (3) = 33.90 SRMR=.08, RMSEA=.08 |

χ2 (3) = 48.29 SRMR =.07, RMSEA=.07 |

χ2 (3) = 97.61 SRMR =.08, RMSEA=.08 |

|

|

| |||

| Hurricane exposure → Internalizing Psychopathology | .04 | .06 | .06 |

| Hurricane exposure → Parent-Child Involvement/Parent-Child Relationship Quality | .01 | −.01 | −.07 |

| Hurricane exposure → Positive Discipline | −.07 | −.11* | −.11* |

| Hurricane exposure → Parents’ Relationship Quality | .06 | −.13* | −.23* |

| Parent-Child Involvement/→ Internalizing Psychopathology Parent-Child Relationship Quality | −.06 | −.16* | −.11* |

| Positive Discipline → Internalizing Psychopathology | .10 | −.01 | .05 |

| Parents’ Relationship Quality → Internalizing Psychopathology | −.12 | .01 | −.04 |

Note:

p < .01

Discussion

A growing body of research suggests that disasters put families at risk for future problems, possibly through changing interpersonal dynamics (Bonanno et al., 2010). Approximately 18 months after Hurricane Georges hit PR, we examined how aspects of the family environment related to developing DSM-IV symptom criteria for an internalizing disorder among children and youth. It is worth noting that only approximately 11.8% of our sample met this criteria for internalizing psychopathology. This suggest that many of the children and youth either were either (a) resilient and never developed significant psychopathology after hurricane exposure, or (b) they recovered within the first several months post-disaster. The family environment factors examined in this study are ones that may give clues as to what may promote resilience and recovery in children and youth.

The Influence of Hurricane Exposure on the Family Microsystem

Our descriptive analysis indicated significant differences between the exposed and unexposed groups, as reported by both parent and youth, for parent-child relationship quality, parent-child involvement, and parents’ relationship quality, with exposed families doing worse. In addition, exposed parents reported less parental monitoring, and were more likely to report a history of MH problems, based on simple comparisons. Given that this study was conducted 12–27 months after the hurricane, it could be that parents with a high level of exposure developed MH problems in the period between the hurricane and the interviews. Correlations between parent and youth report were low, but positive, which is consistent with prior trauma and disaster research (e.g., Rowe, La Greca, & Alexandersson, 2010; Valentino, Berkowitz, & Stover, 2010). This indicated the need to examine models separately, as youth may have a different view from adults.

Children

For children aged 4–10 years, hurricane exposure had a direct effect on internalizing psychopathology, which was expected given our prior research (Felix et al., 2011). Although parent-child relationship quality was negatively related and positive discipline was positively related to internalizing psychopathology, they did not mediate the exposure-psychopathology relationship. Hurricane exposure did not have a direct effect on those family environment variables.

Youth

For youth aged 11–17 years, both parent and youth report were obtained and interesting similarities and differences were discovered. Our prior research with this sample indicated that hurricane exposure had a significant relationship to internalizing disorder at approximately 18 months post-hurricane (Felix et al., 2011). When examined within the context of the family environment, our results suggested that this may, in part, be through the impact of hurricane exposure on family dynamics. For both parent and youth report, when family factors were considered, hurricane exposure no longer had a direct effect on internalizing psychopathology. Per youth report, parents’ relationship quality fully mediated the relation between hurricane exposure and internalizing psychopathology. Hurricane exposure decreased parents’ relationship quality, whereas better relationship quality decreased risk of internalizing psychopathology. Per parent report, the disaster negatively affected their marital relationship (parents’ relationship quality), which was consistent with youth report. But in contrast to the full mediation finding with youth report, this did not affect their child’s risk for internalizing psychopathology. An extensive review supports that family conflicts and a negative family home environment can increase distress among youth post-disaster (Bonanno et al., 2010). It could be that parents were less aware of how their own relationship quality affects their son or daughter, especially in terms of internalizing forms of psychopathology, which tend to be less observable than if a youth had an externalizing behavior reaction to interparental conflict.

Our results suggest that positive discipline was positively related to internalizing psychopathology from the youth’s perspective. This may be because some items of the positive discipline scale involved parents telling and explaining to their child what they did wrong. It could be that youth with internalizing psychopathology were more likely to perceive they were disciplined frequently or were more sensitive to this type of discipline. It also could be that youth who were more distressed elicited more attention from parents (Wilson, Lengua, Meltzoff, & Smith, 2010), including discipline. Finally, this type of discipline may tap into parental intrusiveness to a degree, which was related to child separation anxiety (Wood, 2010). Per parent report, there was not a relationship between positive discipline and internalizing psychopathology for youth, but there was for children. Adolescence is a developmental period characterized by increased rebelliousness with parents and general rule-breaking. Therefore, parents may have perceived they were disciplining their adolescent fairly, but youth may perceive any discipline as too much or unfair.

Negative discipline and parental monitoring were not included in our final SEM models because of a lack of significant relations. In a community study of distant exposure to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, parental discipline also did not emerge as significantly related to posttraumatic stress symptoms (Wilson et al., 2010). Rowe and associates (2010) found that low parental monitoring was related to parent and adolescent reported posttraumatic stress in a clinical sample following Hurricane Katrina. Thus, parental monitoring may have more of an influence in clinical subsamples of youth. In our study, when examining frequencies we discovered that parents were much less likely to say they engaged in the behaviors composing the negative discipline scale. This may have limited variation to detect findings for that discipline subtype. It is possible parents may have been less likely to endorse negative discipline scale items due to self-presentation bias. Observational research of parenting could potentially reduce this problem. Second, parental monitoring and discipline have greater theoretical and empirical connections to risk of externalizing disorders than internalizing (e.g., Dishion & Patterson, 2006). We did not examine externalizing disorders because our prior research with this sample did not note a difference between exposed and unexposed groups for these disorders (Felix et al., 2011). Finally, monitoring and discipline may have more influence in other post-disaster outcome trajectories. The outcome in this study was meeting DSM-IV symptom criteria for an internalizing disorder, which was only one possible post-disaster outcome, representing a minority of the people exposed (Bonanno et al., 2010). It is worth investigating how parental monitoring and discipline may affect all potential post-disaster outcome trajectories of resilience, recovery, delayed, or chronicity (Bonanno et al., 2010).

Parental History of Mental Health Problems

Prior research has indicated that parental MH influences children’s post-disaster MH (e.g., Gil-Rivas et al., 2007; Silverman & La Greca, 2002; Spell et al., 2008; Rowe et al., 2010; Valentino et al., 2010), and we explored how parental history of MH problems may moderate our models of family influences on children’s post-disaster psychopathology. Our preliminary analysis comparing hurricane exposed and non-exposed families on history of MH problems showed that hurricane exposed parents were more likely to report a history of MH problems. Although some parents likely had MH difficulties prior to the disaster, the difference in rates between exposes and non-exposed groups in this representative sample suggest that some parents developed MH problems post-disaster. When comparing our models, we found that hurricane exposure did not have significant relations to internalizing psychopathology for children and youth, regardless of parental history of MH problems status (although previously in this study, it had a relation for children).

Parental history of MH problems moderated the relationship of exposure to family environment. When parents had a history of MH problems, hurricane exposure did not have a significant relation to the family environment. It could be that hurricane exposure no longer had the affect it may have had in the short term aftermath for families struggling with a potentially chronic stressor like parental history of MH problems. It is also possible that hurricane-related distress transformed into chronic MH problems for some parents, and thus no longer had a direct effect, but rather an indirect one. However, when parents did not have a history of MH problems, hurricane exposure influenced positive discipline and parents’ relationship quality for youth; thus, a direct effect on the family environment. This warrants further investigation as Scaramella and colleagues (2008) found that the FSM applied to both disaster-exposed and non-exposed samples.

Another interesting finding is that for youth, parent-child relationship quality (parent report) and parent-child involvement (youth report) decreased risk for internalizing psychopathology when parents did not have a history of MH problems, but was not protective when parents did have a history of MH problems. Youth may disengage from parents who were struggling to cope post-disaster, as it could be too overwhelming for them; hence, the non-significant relation for parent-child relationship quality to internalizing psychopathology for youth whose parents have a history of MH problems. It is also possible, given that both parent and youth psychosocial adjustment influence parenting stress (Deater-Deckard, 1998), that children with internalizing psychopathology post-disaster influenced parents’ MH post-disaster. Observational research of the parent-child relationship can potentially address this question.

Strength, Limitations, Implications, and Directions for Future Research

In recent years, especially following Hurricane Katrina, there has been an increase in published work examining the relation of the family environment to post-disaster MH, and this study contributes to this effort. The rigorous research design, sampling strategy, and interview methodology is an improvement over many prior disaster studies that often rely on convenience samples. Our design allowed for a comparison of exposed and non-exposed groups, and is generalizable to the child and adolescent population in PR. We assessed a wide range of internalizing disorders, which overcomes the predominant focus on PTSD symptoms in much post-disaster research. We were also able to assess a variety of family environment factors to discern which ones were most salient to long-term post-disaster recovery.

Nonetheless, there are limitations to consider that should be addressed in future research. Like most disaster studies, we do not have pre-hurricane information on family dynamics nor parent or child/youth MH that can help determine causality. Our randomly-selected, representative sample with both exposed and non-exposed groups helps address some of the concerns associated with this limitation. Second, although measures were selected from those with established psychometrics in the late 1990s, and were pilot-tested prior to data collection in PR, a few of our family environment measures had lower internal consistency with this sample, which could affect the ability to detect significant results. There is likely more culturally and linguistically appropriate measures to select from now. Third, to both methodologically and statistically test mediation, studies need three time points of data to understand the causal relationships among constructs. With hurricane exposure as one time point, and our assessment as the second time point, we still do not have enough measurement time points to fully assess for true mediation. This is a needed area of research to better understand the post-disaster recovery process. Fourth, our interviews were conducted approximately 18 months after the disaster, and future research would benefit from early assessments to understand the post-disaster response trajectories of children and families (Bonanno et al., 2010). Children who had transient internalizing psychopathology within the first few months of the disaster would not be detected in our study, given that the DISC assessed the past 12 months only. Also, some family factors that were non-significant in this study may have a stronger role to play in the first year of recovery. Finally, we assessed the family environment through surveys, and studies employing observational methods may have different results. Observational studies can overcome some of the limitations of parent and child report, by noting the types and frequency of transactions that occur that contribute to perceptions about the quality of relationships, discipline, and monitoring. Longitudinal, observational research has indicated the mutual influence between parenting behavior, child behavioral and emotional regulation, and subsequent child adjustment among boys (Yates, Obradović, & Egeland, 2010). Another needed line of study would be determining the potential parallel process between parent response and child response over the short, intermediate, and long-term aftermath of a disaster.

In sum, this study contributed to the growing body of literature examining how the family influences post-disaster recovery among children and youth. Our findings supported that disasters can increase risk of meeting DSM-IV symptom criteria for an internalizing disorder through their impact on family relationships for youth and those whose parents do not have a history of MH problems. However, for children, hurricane exposure had a direct relationship to symptoms, regardless of family factors. The fact that we can see this at approximately 18 months or more post-disaster speaks to the need to support survivors for the long term. There is no time clock to judge when a survivor “should be over it.” Clinicians serving children, youth, and families with on-going post-disaster distress should assess, monitor, and address the quality of family relationships and parenting, and provide needed therapeutic supports to parents who are struggling. Some of the differences between parent and youth report of how discipline and parents’ relationship quality affected youth MH indicates that clinicians should interview both parents and youth for their perspective on family dynamics post-disaster. The overall results of this study also suggest that family therapy may be an important additional treatment modality for children and youth showing evidence of psychopathology post-disaster, in conjunction with individually-focused interventions. The use of evidence-based interventions for the family and individual are crucial, and this study contributes to the understanding of the family dynamics that may need to be assessed and targeted when children and families are showing on-going MH problems post-disaster.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by 5R03 MH085276-02 by the National Institute of Mental Health.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Effects of authoritative parental controlo n child behavior. Child Development. 1966;37:887–907. [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Canino GJ, Davies M, Duarte CS, Febo V, Ramirez R, Loeber R. A study of disruptive behavior disorders in Puerto Rican youth: I. Background, design, and survey methods. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adoslescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:1032–1041. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000227878.58027.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Gould MS, Ribera J, Sesman M, Moscoso M. Estimates of the prevalence of childhood maladjustment in a community survey in Puerto Rico. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1988;45:1120–1126. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800360068010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Brewin CR, Kaniasty K, La Greca AM. Weighing the costs of disaster: Consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2010;11:1–49. doi: 10.1177/1529100610387086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo M, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Woodbury M. A cross-cultural adaptation of a diagnostic instrument: The DIS adaptation in Puerto Rico. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 1991;15:1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00050825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo M, Ribera J, Rubio-Stipec M, Canino G, Shrout P, Ramírez R, Martínez-Taboas A. Test-retest reliability of the Spanish version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV) Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:433–444. doi: 10.1023/A:1010499520090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo M, Rubio-Stipec M, Canino G, Woodbury M, Ribera J. The psychological sequelae of disaster stress prospectively and retrospectively evaluated. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1990;18:661–680. doi: 10.1007/BF00931236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullinger M, Alonso J, Apolone G, Leplege A, Sullivan M, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ware JE. Translating health status questionnaires and evaluating their quality: The IQOLA project approach. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51:913–923. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Bravo M. The adaptation and testing of diagnostic and outcome measures for cross-cultural research. International Review of Psychiatry. 1994;6:281–286. doi: 10.3109/09540269409023267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Shrout PE, Rubio-Stipec M, Bird HR, Bravo M, Ramirez R, Martinez-Taboas A. The DSM-IV rates of child and adolescent disorders in Puerto Rico: Prevalence, correlates, service use, and the effects of impairment. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:85–93. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Deaths associated with Hurricane Georges-Puerto Rico. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1736–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.20.1736-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Greenberger E, Lester J, Dong Q, Guo M. A cross-cultural study of family and peer correlates of adolescent misconduct. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:770–781. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.4.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB, editors. Families in troubled times: Adapting to change in rural America. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, West SG, Finch J. The robustness of test statistics to non-normality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:16–29. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K. Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1998;5:314–332. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1:61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. The development and ecology of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, Vol 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2006. pp. 503–541. [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrieva J, Chen C, Greenberger E, Gil-Rivas V. Family relationships and adolescent psychosocial outcomes: Converging findings from Eastern and Western cultures. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2004;14:425–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2004.00081.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felix ED, Hernández LA, Bravo M, Ramírez R, Cabiya J, Canino G. Natural disaster and risk of psychiatric disorders in Puerto Rican children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:589–600. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9483-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Rivas V, Kilmer RP, Hypes AW, Roof KA. The caregiver-child relationship and children’s adjustment following Hurricane Katrina. In: Kilmer RP, Gil-Rivas V, Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG, editors. Helping families and communities recover from disaster: Lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 55–76. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Rivas V, Silver RC, Holman EA, McIntosh DN, Poulin M. Parental response and adolescent adjustment to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:1063–1068. doi: 10.1002/jts.20277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Hoven CW, Narrow WE, Cohen P, Fielding B, Alegria M, Dulcan MK. Measurement of risk for mental disorders and competence in a psychiatric epidemiologic community survey: The National Institute of Mental Health Methods for Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders (MECA) Study. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1998;33:162–173. doi: 10.1007/s001270050039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Chen C. Perceived family relationships and depressed mood in early and late adolescence: A comparison of European and Asian Americans. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:707–716. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.32.4.707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Chen C, Tally SR, Dong Q. Family, peer, and individual correlates of depressive symptomatology among U.S. and Chinese adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:209–219. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, Palcic JL, Vigna JF, Wang J, Spell AW, Pellegrin A, Ruggiero KJ. The effects of parenting behavior on children’s mental health after Hurricane Katrina: Preliminary findings. In: Kilmer RP, Gil-Rivas V, Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG, editors. Helping families and communities recover from disaster: Lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 77–96. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JB, Emery RE. Children’s adjustment following divorce: Risk and resilience perspectives. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 2003;52:352–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00352.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer RP, Gil-Rivas V. Introduction: Attending to ecology. In: Kilmer RP, Gil-Rivas V, Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG, editors. Helping families and communities recover from disaster: Lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 3–24. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kish L. Survey sampling. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Vernberg EM, Prinstein M. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress in children after Hurricane Andrew: A prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:712–723. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskey BJ, Cartwright-Hatton S. Parental discipline behaviours and beliefs about their child: Associations with child internalizing and mediation relationships. Child: Care, Health, and Development. 2009;35:717–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lish JD, Weissman MM, Adams PB, Hoven CW, Bird H. Family psychiatric screening instruments for epidemiologic studies: Pilot testing and validation. Psychiatry Research. 1995;57:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02632-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen WB. Antisocial behavior and mental health problems: Explanatory factors in childhood and adolescence. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawerence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Matías-Carrelo LE, Chávez LM, Negrón G, Canino G, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Hoppe S. The Spanish translation and cultural adaptation of five mental health outcome measures. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2003;27:291–313. doi: 10.1023/A:1025399115023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: StatModel; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- National Hurricane Center. The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. n.d Retrieved on February 3, 2012 from http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/sshws.shtml.

- Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Kaniasty K. 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65:207–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Kaniasty K. Reliability of delayed self-reports in disaster research. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1992;5:575–588. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490050407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Norris FH. Choosing research methods to match research goals in studies of disaster or terrorism. In: Norris FH, Galea S, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, editors. Methods for disaster mental health research. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 45–77. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Stouthamer-Loeber M. The correlation of family management practices and delinquency. Child Development. 1984;55:1299–1307. doi: 10.2307/1129999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CL, La Greca AM, Alexandersson A. Family and individual factors associated with substance involvement and PTS symptoms in greater New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:806–817. doi: 10.1037/a0020808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Sohr-Preston SL, Callahan KL, Mirabile SP. A test of the Family Stress Model on toddler-aged children’s adjustment among Hurricane Katrina impacted and non-impacted low-income families. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:530–541. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab-Stone M, Fallon T, Briggs M, Crowther B. Reliability of diagnostic reporting for children aged 6–11 years: A test-retest study of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children – Revised. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1048–1054. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley CF, Cross DG. A psychometric evaluation of the Spanier Dyadic Adjustment Scale. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1982;44:739–741. doi: 10.2307/351594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, La Greca AM. Children experiencing disasters: Definitions, reactions, and predictions of outcomes. In: La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Vernberg EM, Roberts MC, editors. Helping children cope with disasters and terrorism. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 11–33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Krohn MD. Delinquency and family life among male adolescents: The role of ethnicity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1995;24:69–93. doi: 10.1007/BF01537561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1976;38:15–28. doi: 10.2307/350547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spell AW, Kelley ML, Wang J, Self-Brown S, Davidson KL, Pellegrin A, Baumeister A. The moderating effects of maternal psychopathology on children’s adjustment post-Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:553–563. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Wakefield JC. DSM-IV Diagnostic criterion for clinical significance: Does it help solve the false positives problem? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1856–1864. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.12.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CA, Manganello JA, Lee SJ, Rice JC. Mothers’ spanking of 3-year-old children and subsequent risk of children’s aggressive behavior. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1057–e1065. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino K, Berkowitz S, Stover CS. Parenting behaviors and posttraumatic symptoms in relation to children’s symptomatology following a traumatic event. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23:403–407. doi: 10.1002/jts.20525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg EM. Intervention approaches following disaster. In: La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Vernberg EM, Roberts MC, editors. Helping children cope with disasters and terrorism. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 55–72. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserstein SB, La Greca AM. Hurricane Andrew: Parent conflict as a moderator of children’s adjustment. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1998;20:212–224. doi: 10.1177/07399863980202005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weems CF, Taylor LK, Cannon MF, Marino RC, Romano DM, Scott BG, Triplett V. Post traumatic stress, context, and the lingering effects of the Hurricane Katrina disaster among ethnic minority youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:49–56. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9352-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AC, Lengua LJ, Meltzoff AN, Smith KA. Parenting and temperament prior to September 11, 2001 and parenting specific to 9/11 as predictors of children’s posttraumatic stress symptoms following 9/11. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:445–459. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.486317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ. Parental intrusiveness and children’s separation anxiety in a clinical sample. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2010;37:73–87. doi: 10.1007/s10578-006-0021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates TM, Obradović J, Egeland B. Transactional relations among contextual strain, parenting quality, and early childhood regulation and adaptation in a high risk sample. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:539–555. doi: 10.1017/S095457941000026X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]