Abstract

Background

The treatment of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) following early detection is associated with good outcomes. Therefore, the survival and prognosis of OSCC patients could be hugely improved by identifying reliable biomarkers for the early diagnosis of the disease. Our previous methylation microarray analysis results have suggested that the gene encoding tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 (TFPI-2) is a potential clinical predictor as well as a key regulator involved in OSCC malignancy.

Methods

Methylation of the TFPI-2 promoter in oral tissue specimens was evaluated by bisulfite sequencing assay, quantitative methylation-specific PCR, and pyrosequencing assay. The differences in methylation levels among the groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) was used to evaluate the discrimination ability for detecting OSCC. Cellular TFPI-2 expression was analyzed by quantitative reverse-transcription PCR before and after treatment with 5′-aza-2′-deoxycytidine and trichostatin A, to confirm whether TFPI-2 was epigenetically silenced in OSCC cells. We investigated whether TFPI-2 plays a role as a tumor suppressor by establishing TFPI-2-overexpressing OSCC cells and subjecting them to in vitro cellular proliferation, migration, and invasion assays, as well as an in vivo metastasis assay.

Results

TFPI-2 was hypermethylated in OSCC tissues versus normal oral tissues (P < 0.0001), with AUROC = 0.91, when using a pyrosequencing assay to quantify the methylation level. TFPI-2 silencing in OSCC was regulated by both DNA methylation and chromatin histone modification. Restoration of TFPI-2 counteracted the invasiveness of OSCC by inhibiting the enzymatic activity of matrix metalloproteinase-2, and consequently interfered with OSCC metastasis in vivo.

Conclusions

Our data suggest strongly that TFPI-2 is a down-regulated tumor suppressor gene in OSCC, probably involving epigenetic silencing mechanisms. The loss of TFPI-2 expression is a key event for oral tumorigenesis, especially in the process of tumor metastasis.

Keywords: Oral squamous cell carcinoma, DNA methylation, Biomarker, TFPI-2, Tumor suppressor gene, Metastasis, Matrix-associated serine protease inhibitor, Matrix metalloproteinase-2

Background

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), which constitutes more than 90% of oral cancers arising from the oral cavity [1], is not only one of the most frequently occurring cancers worldwide, but is also particularly prevalent in Taiwan. Oral cancer has been the fourth leading cause of death from cancer among males in Taiwan since 2003 [2]. As a molecularly heterogeneous disease, OSCC is strongly associated with risk factors including alcohol, tobacco, and betel nut consumption [3–6]. OSCC is a particularly troublesome cancer due to its rapid progression and frequent metastasis [7], causing deaths at an increasing rate in Taiwan [2]. The treatment of oral cancer following early detection is associated with good outcomes, but the 5-year survival rate is <30% among patients with stage IV disease [8]. Therefore, identifying reliable biomarkers for the early diagnosis of OSCC may help to improve the patients’ survival and prognosis.

In addition to genetic alterations such as gene mutation [9], loss of heterozygosity [10], and microsatellite instability [11], epigenetic alterations (particularly hypermethylation in the promoter region of regulatory genes) have been increasingly recognized as key events in oral tumorigenesis [12]. By taking advantage of the genome-wide screening approach, we have recently employed the Illumina GoldenGate Methylation Array to identify methylated genes in OSCC tissues (unpublished data). One of the genes identified with this approach was that encoding tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 (TFPI-2). With a molecular weight of 27, 31, or 33 kDa, depending upon the level of glycosylation [13], TFPI-2 is synthesized and secreted extracellularly mainly by keratinocytes, fibroblasts, smooth-muscle cells, synoviocytes, and endothelial cells [14–17]. As a known Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitor and placental protein 5 [13,18,19], TFPI-2 counteracts the activity of several extracellular matrix (ECM)-associated serine proteases, including trypsin, plasmin, chymotrypsin, cathepsin G, plasma kallikrein, and the factor VIIa-tissue factor complex [20,21]. Previous studies have demonstrated that TFPI-2 suppresses tumor invasion and metastasis via its inhibitory activity on ECM degradation and remodeling [22,23]. Roles of TFPI-2 in induction of the apoptosis pathway and in angiogenesis have also been demonstrated [24–27]. It has been shown that TFPI-2 is down-regulated via epigenetic silencing mechanisms including promoter hypermethylation and histone deacetylation in several types of tumor, such as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [28], melanoma [29], hepatocellular carcinoma [30], gastric carcinoma [31], and glioma [32]. The level of TFPI-2 methylation was also found to differ between preoperative and postoperative saliva DNA in oral cancer patients, highlighting its potential diagnostic value as a biomarker for oral cancer [33].

In the present study we first examined the methylation level of TFPI-2 in clinical OSCC specimens. Current techniques used to measure DNA methylation, including bisulfite sequencing assay, quantitative methylation-specific PCR (qMSP), and pyrosequencing assay, were applied to uncover the DNA methylation status of the TFPI-2 promoter region. The methylation level of TFPI-2 was further statistically analyzed to determine whether there was any correlation with the pathological stages of OSCC patients. We then restored the gene expression of TFPI-2 in OSCC cell lines by using epigenetic drugs and employing lentivirus vector-mediated gene transfer of TFPI-2. Restoration of TFPI-2 significantly suppressed the invasion and metastasis of OSCC cells. Our data strongly suggest that epigenetic silencing of TFPI-2 plays an important role in oral tumorigenesis.

Methods

Collection of oral tissue specimens and bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA

Normal oral tissues, OSCC tissues and their corresponding non-tumor tissues were obtained from the tissue banks of China Medical University Hospital and Buddhist Tzu Chi General Hospital in Taiwan. Genomic DNA of the tissues was isolated using Gentra Puregene Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and 500 ng of genomic DNA was subjected to bisulfite conversion using EZ DNA methylation kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA). Bisulfite conversed Universal Methylated Genomic DNA (Millipore, Billerica, MA,) was used as in-vitro methylated DNA (IVD) control for the methylation level determined by qMSP and pyrosequencing assays.

Bisulfite sequencing assay and real-time quantitative methylation-specific PCR

For bisulfite sequencing, the primers targeting the promoter region near the TFPI-2 transcription start site were used for PCR as previously described [30]. The PCR products were separated by gel electrophoresis, purified with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), cloned into the yT&A cloning vector (Yeastern Biotech, Taipei, Taiwan), and sequenced. For real-time qMSP, primers targeting the promoter region of TFPI-2 were as follows: forward, 5′-ATAAAGCGGGTATTCGGGTC-3′; reverse, 5′-CTCCGCCGATTAAAAAAA-3′. Real-time qMSP was performed using ABI StepOne real-time PCR system according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems, Forster City, CA). As an input control for real-time qMSP, a DNA fragment devoid of any CpG dinucleotide in ACTB was amplified using the following primers: forward, 5′-TGGTGATGGAGGTTTAGTAAGT-3′; reverse, 5′-AACCAATAAAACCTACTCCCTTAA-3′. The extents of methylated TFPI-2 and ACTB were determined by the threshold cycle number for each sample. The percentage of TFPI-2 methylation was calculated as the ratio of TFPI-2 to ACTB of a sample divided by the same ratio of IVD.

Pyrosequencing methylation assay

To further verify the results of bisulfite sequencing and qMSP, pyrosequencing primers were designed for the region of interest using Pyromark Assay Design v2.0 (Qiagen): forward, 5′-Bio+GGGTGATAGTTTTAGTGTATGAATTAGTT-3′; reverse, 5′-CTAAACAACATCCCCCAATACAACCTC-3′; reverse sequencing primer, 5′-ACTTTCTACTCCAAAC-3′. Pyrosequencing assay was carried out using the PyroMark Q24 System (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Epigenetic drug treatment

1 × 106 OSCC cells were seeded onto 10-cm culture dishes and treated with 0.5 μM or 5 μM 5′-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-azaDC) (Sigma, St Louis, MO) for 72 h followed by 0.25 μM trichostatin A (TSA) (Sigma) or DMSO for 12 h. For TSA treatment alone, cells were incubated with DMSO for 72 h followed by 0.25 μM TSA for 12 h. Drugs and culture medium were refreshed every 24 h during the treatments.

Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cell lines using REzol (Protech, Taipei, Taiwan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using ABI StepOne real-time PCR system as the following steps: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 50 cycles of successive incubation at 95°C for 15 sec and at 68°C for 45 sec. TFPI-2 and GAPDH cDNA were amplified with the following primers: TFPI-2 forward, 5′-GCGATGCTGCTCAGGAG-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCTGCGTGTACCTGTCGTAGTAG-3′; GAPDH forward, 5′-TTGACGGTGCCATGGAATTT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCCATCAATGACCCCTTCATT-3′. TFPI-2 expression was normalized against that of GAPDH.

Quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation-PCR

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-PCR was performed as previously described [34]. In brief, 2 × 106 OSCC cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde and washed with PBS in the presence of protease inhibitors. Cells were homogenized and their chromatin was subjected to ChIP using magnetic Dynal beads (Invitrogen) and antibody against acetylated or trimethylated lysine 9 of histone H3 (H3K9) (Millipore, Temecula, CA). Fold-enrichment of amplified DNAs by ChIP was assessed using protocols as previously described [35]. Specific primers targeting the promoter region of TFPI-2 were as follows: R1-forward, 5′-GCAGGTCATTTCCGTCTAGCTT-3′ and R1-reverse, 5′-ACCTGCCTCCCAAACTTTCTC-3′; R2-forward, 5′-ACCACTTTCCCTCTCTTTTGCT-3′ and R2-reverse, 5′-TCGTAGTAGTAACGGAGAAGTAGGGC-3′.

Cell lines

The OSCC cell lines OC2 and OCSL [36], derived from Taiwanese male patients who had habits of alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and betel nut chewing, were maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen, Federick, MD). HEK293T cells were grown in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS.

Plasmid construction and cell infection

The full-length human TFPI-2 cDNA (~0.7 kb) was cloned from the immortalized ovarian surface epithelia cell line IOSE [37] by RT-PCR with primers 5′-TTTCTCGGACGCCTTGCC-3′ and 5′-GAATGTTTAAAATTGCTTC-3′. The cDNA was introduced into a lentiviral vector plasmid pSin-IRES-GFP (pIG) [38] at the EcoRI and XbaI sites to generate pSin-TFPI2-IRES-GFP (pTIG). The plasmids pIG, pTIG and pSin-FLuc-IRES-GFP (pFIG, a firefly luciferase-expressing lentiviral vector plasmid) were transiently transfected into HEK293T cells and at 48 h posttransfection the lentivirus-containing supernatants were collected for infection. Successful infection was monitored by GFP expression and the infected cells were sorted by FACSAria III Cell Sorter (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Extracellular matrix protein extraction and immunoblot assay

Cells were grown to ~90% confluence in culture dishes and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins was harvested from the cells as described by Ehrlich et al. [39]. Briefly, cells were washed three times with PBS and lysed through the incubation with PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were washed three times with PBS and another three times with 20 nM Tris–HCl [pH 7.4] containing 100 mM NaCl and 0.1% Tween 20. Finally, 200 μl of 1 × SDS-PAGE sample buffer was added to the culture dishes and agitated for 20 min at room temperature. The collected ECM proteins were boiled and 50 μl of aliquots of the extracts was assayed using 12% polyacrylamide gels. The expression of TFPI-2 protein was detected by a polyclonal antibody against TFPI-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Cell proliferation assay

The lentiviral vector-infected cells were seeded onto replicate 96-well plates (500 cells per well). Cell proliferation was determined daily with MTS assay using the CellTiter Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Relative cell number was measured on an ELISA plate reader with an absorbance set at a wavelength of 490 nm.

Cell cycle analysis

The lentiviral vector-infected cells were seeded onto replicate 6-well plates (1 × 105 cells per well). After 48 h, the cells were collected, washed, and fixed in 75% ethanol at −20°C for 48 h. The cells were then treated with 0.1 mg/ml RNase A (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany), stained with 10 μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma), and analyzed by FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). The percentage of apoptotic cells in sub-G1 area was quantified using CellQuest Pro software (BD Biosciences).

Matrigel invasion assay

Invasion assay was done on 6-well Transwells (Millipore) with Matrigel-coated polycarbonate filters (8 μm pore size). Two × 104 cells were suspended in 200 μl of RPMI medium supplemented with 0.5% FBS and seeded on the upper chamber well. The lower chamber well was filled with RPMI medium containing 10% FBS. After 48 h of incubation at 37°C, nonpenetrating cells were removed from the upper surface of the filter and penetrating cells on the lower surface of the filter were fixed with methanol and stained with Giemsa solution (Sigma). The numbers of penetrating cells were counted under a light microscope.

Collagen zymography

The inhibitory effect of TFPI-2 on enzymatic activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) was assayed by collagen zymography. Two × 105 OC2 cells were suspended in complete medium and plated onto culture dishes. After 48 h of incubation, the medium was changed to serum-free RPMI and the cells were incubated for another 24 h. The conditioned medium was collected and the protein concentrations were determined by BCA Protein Assays (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA). Fifty μg of total proteins was mixed with non-reducing sample buffer containing 315 mM Tris [pH 6.8], 50% glycerol, 5% SDS and 0.025% bromophenol for electrophoresis. Without boiling, the mixed solution was loaded on a 10% polyacrylamide gel containing 0.5 mg/ml collagen (Sigma). After electrophoresis, gel was incubated for 1 h at 25°C in a 2.5% Triton X-100 solution followed by 20-min wash with deionized water for 2 times, and then incubated overnight at 37°C in a 50 mM Tris–HCl [pH 8.0], containing 5 mM CaCl2. The gel was stained with 0.25% Coomassie blue and destained with 10% methanol and 7% acetic acid. Enzymatic activity attributed to MMPs can be visualized as clear bands against a blue background. The relative intensity of the bands was quantified by ImageJ.

In vivo tumor metastasis assay

Athymic BALB/c nude mice were obtained from National Laboratory Animal Center, Taiwan. Cells at a density of 1 × 106 in 100 μl of PBS were intravenously injected into the tail veins of athymic BALB/c nude mice. Forty days after tumor cell inoculation, the mice were sacrificed and their lungs were excised. The lung tissues were fixed with 10% formaldehyde and the number of pulmonary tumor nodules on each lung was counted.

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the methylation levels between or among groups of tissue specimen. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the ROC curve (AUROC) was calculated to summarize the accuracy of using methylation level for detecting OSCC. The odds ratios between methylation level and OSCC were measured by logistic regression models. Differences with P < 0.05 were deemed significant. Analyses were performed in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Box plots were generated by SigmaPlot version 10 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA).

Results

TFPI-2 is frequently hypermethylated in OSCC tissues

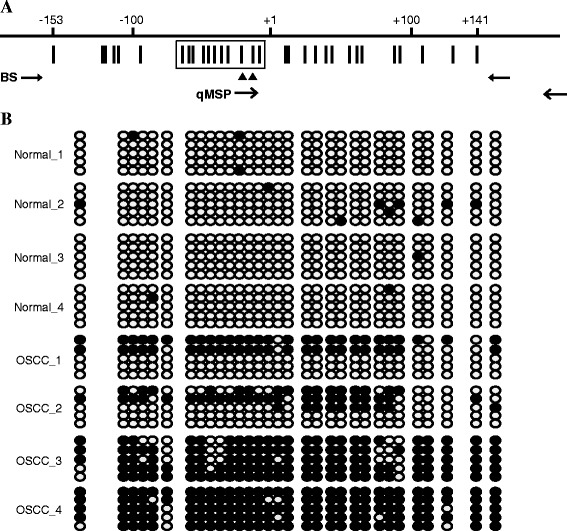

Based on our recent methylation array analysis involving specimens of normal oral tissues and OSCC tissues at different pathological stages, the methylation level of TFPI-2 was found to differ between normal- and tumor-tissue DNA. The average β values in the three query sites (P152, P9, and E141) were all significantly higher in the tumor tissues than in normal tissues (data not shown). To validate the methylation array data, we further analyzed the methylation status of several oral tissue specimens by bisulfite sequencing assay. As shown in the target region centering on the TFPI-2 transcription start site comprising 31 CpG sites (Figure 1A), highly dense methylation was observed in the tumor tissues, whereas the normal tissues were essentially free of methylation (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Bisulfite sequencing of TFPI-2 in normal oral and OSCC tissues. (A) The region centering on the TFPI-2 transcription start site, comprising 31 CpG sites. The distribution of CpG sites (vertical bar) and the position of the hybridized PCR primer pairs for bisulfite sequencing (BS) and quantitative methylation-specific PCR (qMSP) are shown. Two CpG sites in the qMSP forward primer are indicated (filled triangles), and the 11 CpG sites analyzed by pyrosequencing assay are boxed. (B) Representative bisulfite sequencing assay for normal oral and OSCC tissues. For each tissue sample, five randomly chosen clones were sequenced and the methylation status of each of the 31 CpG sites is indicated by the circles: closed and open circles represent methylated and unmethylated CpG sites, respectively.

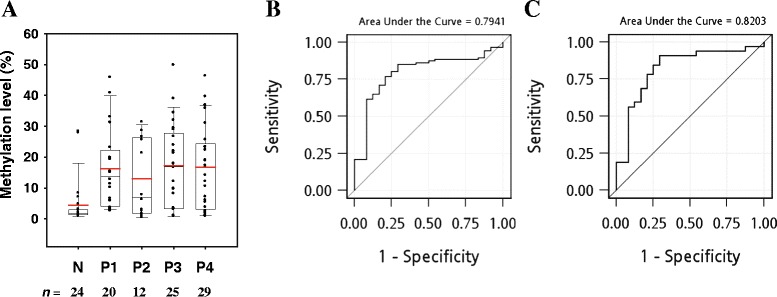

To further quantify the methylation level of TFPI-2, we performed real-time qMSP and pyrosequencing methylation assays for oral tissue specimens. The selected patients’ characteristics are presented in Table 1. In total, 110 samples were analyzed by qMSP, while 60 samples were subjected to pyrosequencing methylation assay. The methylation level is summarized as mean and standard deviation values or median and interquartile range values. The 110 oral tissue specimens analyzed by qMSP comprised 86 tumor tissues and 24 normal tissues; the TFPI-2 methylation level was significantly higher in tumors than in normal tissue (P < 0.0001; Figure 2A). The median methylation percentages in tumor tissues at stages P1–P4 were 13.87%, 6.96%, 16.86%, and 16.64%, respectively; the corresponding value in normal tissues was 1.79% (P < 0.05 for any specific stage vs the normal tissues). A similar pattern of TFPI-2 methylation status was obtained using pyrosequencing assay with 60 oral tissue specimens comprising 49 tumor tissues and 11 normal tissues (P < 0.0001; Figure 3A). The median methylation percentages in P1–P4 tumors were 18.26%, 12.17%, 21.03%, and 33.10%, respectively, while in normal tissues it was 3.82% (P < 0.05 for any specific stage vs the normal tissues). The methylation level differed not only between the normal and tumor tissues, but also between the early- and late-stage tumor tissues. Figure 3B shows the differential pattern of TFPI-2 methylation levels among the 11 CpG sites between the early-stage (P1 and P2) and late-stage (P4) tumor tissues. The methylation levels were significantly higher in the P4 tumors compared to the P1 and P2 tumors at most of the CpG sites.

Table 1.

Selected patients’ characteristics

| (a) TFPI-2 methylation level by qMSP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 110 | (100) | 13.64 | 13.05 | 8.94 | 21.06 |

| Pathological Stage | ||||||

| Normal | 24 | (21.8) | 4.45 | 7.51 | 1.79 | 1.62 |

| I | 20 | (18.2) | 16.23 | 12.97 | 13.87 | 16.71 |

| II | 12 | (10.9) | 12.96 | 12.46 | 6.96 | 23.95 |

| III | 25 | (22.7) | 17.19 | 13.62 | 16.86 | 23.15 |

| IV | 29 | (26.4) | 16.67 | 13.60 | 16.64 | 19.61 |

| Cancer Site | ||||||

| Buccal | 36 | (41.9) | 17.05 | 12.46 | 15.95 | 18.90 |

| Tongue | 50 | (58.1) | 15.59 | 13.71 | 11.66 | 22.63 |

| (b) TFPI-2 methylation level by pyrosequencing | ||||||

| n | (%) | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 60 | (100) | 18.80 | 14.99 | 15.58 | 23.79 |

| Pathological Stage | ||||||

| Normal | 11 | (18.3) | 4.43 | 1.91 | 3.82 | 2.94 |

| I | 15 | (25.0) | 20.35 | 12.19 | 18.26 | 23.14 |

| II | 12 | (20.0) | 16.21 | 9.48 | 12.17 | 12.97 |

| III | 14 | (23.3) | 21.63 | 16.08 | 21.03 | 28.34 |

| IV | 8 | (13.3) | 34.63 | 18.06 | 33.10 | 23.50 |

| Cancer Site | ||||||

| Buccal | 19 | (38.8) | 29.70 | 14.41 | 28.12 | 16.07 |

| Tongue | 30 | (61.2) | 17.18 | 12.96 | 13.86 | 20.82 |

SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range.

Figure 2.

Methylation status of TFPI-2 determined by qMSP assay. (A) Box plots of the TFPI-2 methylation level as determined by the qMSP assay. The amount of methylated TFPI-2 was normalized to the amount of ACTB and is expressed as a percentage of that in IVD (given as 100%). N, normal oral tissues; P1–P4, OSCC tissues classified according to pathological stage. In each box plot, the whiskers represent the 10th and 90th percentiles, the lower and upper limits of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the red line is the mean. (B) ROC curve obtained using TFPI-2 methylation to detect OSCC. The AUROC was 0.79. (C) ROC curve obtained using TFPI-2 methylation to detect early-stage OSCC (P1 and P2). The AUROC was 0.82.

Figure 3.

Methylation status of TFPI-2 determined by pyrosequencing assay. (A) Box plots of TFPI-2 methylation level determined by the pyrosequencing assay. TFPI-2 methylation level is expressed as a percentage of that in IVD (given as 100%). The median methylation percentage across all 11 CpG sites was 3.82% in normal oral tissues, and 18.26%, 12.17%, 21.03%, and 33.10% in P1–P4 tumors, respectively. In each box plot, the whiskers represent the 10th and 90th percentiles, the lower and upper limits of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the red line is the mean. (B) Differential pattern of TFPI-2 methylation at each individual CpG site between early-stage (P1 and P2) and late-stage (P4) tissues. Numbers at the x-axis indicate nucleotide positions of CpG site relative to the transcription start site. Statistically significant differences in methylation levels are indicated by asterisks (*). (C) ROC curve obtained using TFPI-2 methylation to detect OSCC. The AUROC was 0.91. (D) ROC curve obtained using TFPI-2 methylation to detect early-stage OSCC (P1 and P2). The AUROC was 0.94.

TFPI-2 methylation is a good biomarker for OSCC detection

TFPI-2 hypermethylation could be used to discriminate tumor tissues from the normal ones. The AUROC values for using methylation level to detect OSCC were 0.79 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.69–0.89; Figure 2B) and 0.91 (95% CI = 0.83–0.98; Figure 3C) for the qMSP and pyrosequencing assays, respectively. A 1% increase in methylation level, as quantified by pyrosequencing assay, was associated with a 1.49-fold higher of risk of OSCC (95% CI = 1.06–2.10, P = 0.023), while the odds ratio was 1.13 (95% CI = 1.05–1.22, P = 0.001) per 1% increase of methylation level when quantified by qMSP. Moreover, TFPI-2 hypermethylation could be used to discriminate the early-stage tumor tissues from the normal ones. The AUROC values for using methylation level to detect early-stage OSCC (P1 and P2) were 0.82 (95% CI = 0.70–0.94; Figure 2C) and 0.94 (95% CI = 0.87–1.00; Figure 3D) for the qMSP and pyrosequencing assays, respectively.

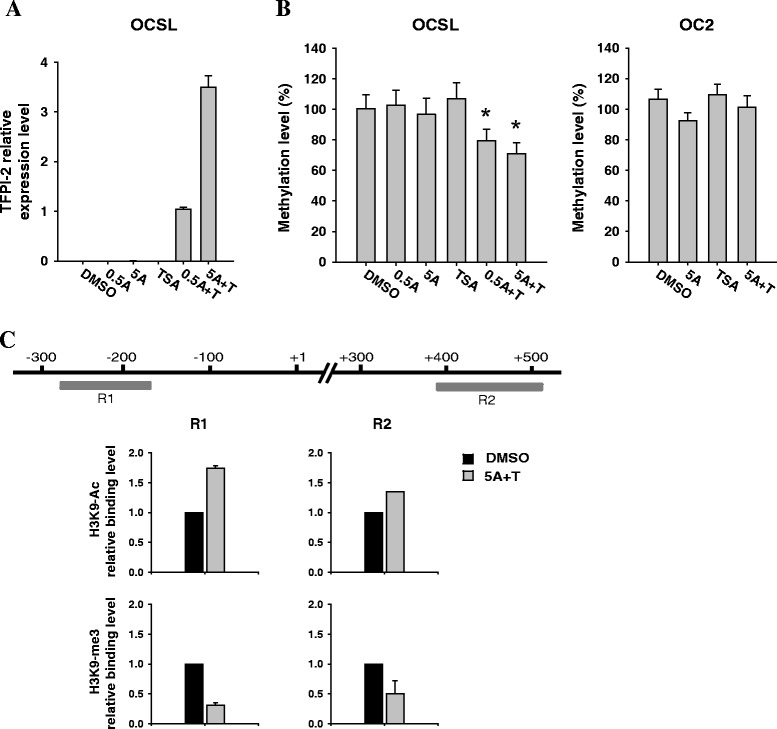

Promoter hypermethylation and histone modification contribute to TFPI-2 inactivation in OCSL cells

Aberrant DNA methylation in the promoter region is a key mechanism for gene silencing, and so we treated the OSCC cell lines OCSL and OC2 with the demethylating agent 5-azaDC to determine whether TFPI-2 expression could be restored. We also investigated whether histone modification is involved in TFPI-2 silencing using the histone deacetylase inhibitor TSA. RT-PCR revealed no detectable TFPI-2 mRNA expression in OC2 cells irrespective of the treatment (data not shown). In OCSL cells, neither 5-azaDC nor TSA treatment alone induced the expression of TFPI-2; however, a dramatic increase in TFPI-2 expression was observed after combined treatment with 5-azaDC and TSA (Figure 4A). In agreement with TFPI-2 reactivation in OCSL cells, TFPI-2 methylation levels in OCSL were decreased when treated with the combination of 5-azaDC and TSA (Figure 4B, left); in contrast, there was no such effect in OC2 cells (Figure 4B, right). To further confirm the involvement of histone modification in TFPI-2 regulation in OCSL cells, we performed ChIP-PCR assay to analyze histone status in respect to active and repressive chromatin marks at the promoter region of TFPI-2 by using antibodies against acetylated H3K9 (H3K9-Ac) and trimethylated H3K9 (H3K9-me3). After combined treatment with 5-azaDC and TSA, higher levels of the active histone mark H3K9-Ac were found at the TFPI-2 promoter regions. In contrast, lower levels of the repressive histone mark H3K9-me3 were found at the same regions (Figure 4C). Together these observations show that the synergistic effect of 5-azaDC and TSA inducing a substantial TFPI-2 reexpression implies that both DNA methylation and histone deacetylation play important roles in TFPI-2 silencing in OCSL.

Figure 4.

Reactivation of TFPI-2 using epigenetic drugs. (A) RT-PCR analysis of TFPI-2 expression in OCSL cells treated with 5-azaDC, TSA, or both. 0.5A, 0.5 μM 5-azaDC; 5A, 5 μM 5-azaDC; TSA, 0.25 μM TSA; 0.5A + T, 0.5 μM 5-azaDC and 0.25 μM TSA; 5A + T, 5 μM 5-azaDC and 0.25 μM TSA. The mRNA level of TFPI-2 in OCSL was compared with that of the control cell line IOSE, which was assigned a value of 1. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) Methylation levels of OCSL and OC2 cells treated with 5-azaDC, TSA, or both. The DNA of OCSL and OC2 was bisulfite converted and the percentage of TFPI-2 methylation was determined using the pyrosequencing assay. The TFPI-2 methylation level is expressed as a percentage of that in IVD (given as 100%). The DMSO- and drug-treated groups were compared using Student’s t-test; P < 0.05 (*) was considered statistically significant. (C) Histone modifications at the promoter region of TFPI-2 in OCSL cells. ChIP assays were performed with antibodies against H3K9-Ac and H3K9-me3 in OCSL cells. Regions of the TFPI-2 promoter for quantitative ChIP-PCR assay are indicated as R1 and R2. The binding of H3K9-Ac and H3K9-me3 antibodies to regions R1 and R2 was measured by the quantification of ChIP DNA against a standard curve generated from input DNA. The binding level of each antibody in OCSL treated with 5 μM 5-azaDC and 0.25 μM TSA was compared with that of the cell treated with DMSO, which was assigned a value of 1.

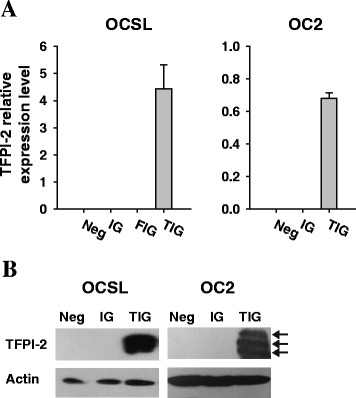

Effects of TFPI-2 on the growth of OSCC cells

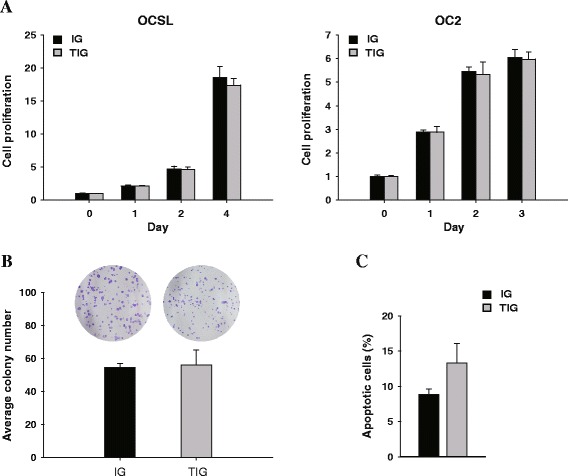

The observation of TFPI-2 silencing in OSCC tissues and cells inspired us to examine the tumor-suppressive role of TFPI-2 in OSCC. We prepared OSCC cells transduced with TFPI-2-expressing lentiviral vector (TIG) and confirmed the reexpression of TFPI-2 in the cells by qRT-PCR (Figure 5A). Western blot analysis also revealed the presence of TFPI-2 triplets in the ECM of TIG-transduced OSCC cells, while no such protein expression was observed in IG-transduced or untransduced cells (Figure 5B). The effect of restoring TFPI-2 expression in OSCC was examined by performing cell proliferation, colony formation, and apoptosis assays. Restoration of TFPI-2 in OSCC cells did not significantly affect the cell proliferation rate, the number of colonies being formed, or the percentage of apoptotic cells (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Reexpression of TFPI-2 in OSCC cells by gene transfer. (A) RT-PCR analysis of TFPI-2 expression in OSCC cells. Experiments were performed in triplicate and the results are shown as the changes in the expression relative to IOSE. Neg, untransduced cells; IG, cells transduced with a control lentiviral vector; FIG, cells transduced with a firefly luciferase-expressing lentiviral vector; TIG, cells transduced with a TFPI-2-expressing lentiviral vector. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) Western blot analysis of ectopic TFPI-2 overexpression in OSCC cells. ECM proteins were extracted from the cells for Western blot analysis and TFPI-2 isoforms with molecular weights of 27, 31, and 33 kDa due to different extents of glycosylation are indicated with arrows. Beta-actin was used as a loading control.

Figure 6.

Effects of TFPI-2 on the growth of OSCC cells. (A) Effect of TFPI-2 on the cell proliferation of OSCC cells was determined by MTS assay. (B) Quantitative analysis of the number of colonies formed using the colony formation assay. OC2 cells transduced with TIG exhibited no change in the number of colonies formed. (C) Effect of TFPI-2 on apoptosis of OC2 cells was determined by cell cycle analysis. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

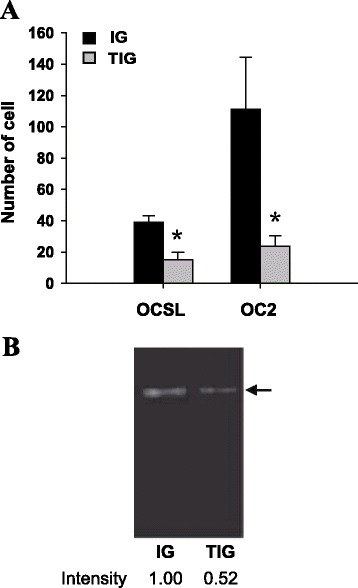

TFPI-2 suppresses OSCC cell invasion and blocks MMP-2 activity to reduce tumor metastasis in vivo

A Matrigel invasion assay was performed to determine whether TFPI-2 has an inhibitory effect on OSCC cell invasion. It was found that TFPI-2 significantly abolished the invasiveness of OCSL and OC2 cells (Figure 7A). Interestingly, the migratory ability did not differ significantly between IG- and TIG-transduced OSCC cells (data not shown), highlighting the ability of TFPI-2 to inhibit ECM degradation during the process of metastasis. Collagen zymography was performed on conditioned medium from the transduced OC2 cells in order to examine whether tumor-secreted proteases were targeted by TFPI-2 inhibition. A less-dense band was found at the position corresponding to the protein size of active MMP-2, demonstrating that the enzymatic activity of MMP-2 was reduced in TIG-transduced cells (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Inhibitory effect of TFPI-2 on OSCC invasion and MMP-2 enzymatic activity. (A) In vitro cell-invasion assay. Cells that penetrated the Matrigel-coated filter were fixed, stained, and counted in at least three fields of view under a microscope. Comparison between IG and TIG groups was evaluated by Student’s t-test, and P < 0.05 (*) was considered statistically significant. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) The enzymatic activity of MMP-2 was determined by collagen zymography. Conditioned medium containing secreted collagenases was collected from the transduced OC2 cell cultures and subjected to collagen zymography. The position of MMP-2 (62 kDa) is indicated by an arrow.

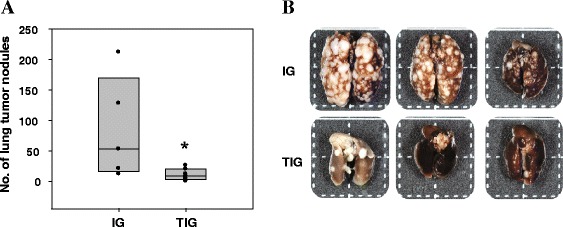

It could be reasoned that TFPI-2 restoration counteracted tumor invasion by negatively regulating MMP-2 activation. To confirm the role of TFPI-2 in the suppression of OSCC metastasis, we performed an experimental metastasis assay by intravenously injecting transduced OC2 cells into nude mice. The number of lung metastatic nodules derived from the circulating cells in each mouse was counted 40 days after tumor-cell inoculation. As shown in Figure 8, far fewer metastatic nodules developed in the TIG group compared to the IG group, demonstrating that TFPI-2 overexpression restrained OC2 metastasis and alleviated tumor malignancy.

Figure 8.

TFPI-2 reduced OSCC metastasis in vivo. (A) IG- or TIG-transduced OC2 cells were intravenously injected into the tail veins of athymic BALB/c nude mice (n = 5 in the IG group; n = 7 in the TIG group). Forty days after tumor cell inoculation, the number of pulmonary metastatic nodules derived from circulating cells in each mouse was counted. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the numbers of tumor nodules between groups. *, P = 0.023. (B) Representative photograph of lung tissues excised from the mice.

Discussion

In this study we applied a high-throughput methylation array to investigate the DNA methylation status in oral tissue specimens. Comparison of gene methylation profiling between normal oral and OSCC tissues has suggested that TFPI-2 is hypermethylated in OSCC tissues, an observation that has been confirmed by qMSP and pyrosequencing assays. In agreement with the concept that TFPI-2 methylation is an early event in esophageal carcinogenesis [40], a significant difference in methylation level of TFPI-2 was found between normal oral tissues and tumor tissues at early stages, further validating the clinical value of TFPI-2 methylation profiling for the early detection of OSCC. In addition, the TFPI-2 methylation level in tumor tissues was higher at the P4 stage than at earlier stages (P1 and P2). Most of the 11 CpG sites analyzed by pyrosequencing assay displayed significant differences in methylation level between early and late stages, indicating the trend of increased methylation with progressive oral tumorigenesis.

While it is clear that TFPI-2 methylation profiling allows clinical samples to be discriminated, the difference in TFPI-2 mRNA expression between tumor and normal tissues was not as convincing as was expected (data not shown), mostly due to the heterogeneity of OSCC tissue specimens, in which both TFPI-2-expressing and nonexpressing cells were present [41]. Therefore, we measured TFPI-2 mRNA expression in OSCC cell lines and determined whether TFPI-2 down-regulation was caused by DNA methylation and histone deacetylation. We successfully reactivated TFPI-2 expression in OCSL cells but not in OC2 cells after combined treatment with 5-azaDC and TSA. In addition, the extent of TFPI-2 restoration in OCSL was comparable to that in TIG-transduced OCSL (3.5-fold vs 4.4-fold changes in TFPI-2 expression relative to IOSE). It is thus possible that for cells that are nonresponsive to 5-azaDC and TSA, such as OC2, the alternatives of viral or non-viral vector-mediated gene transfer for achieving sufficient TFPI-2 restoration are candidates for OSCC therapy.

The mechanism underlying the effect of DNA methylation on the repression of TFPI-2 in breast cancer cell lines has been reported previously [42]. Sequence analysis of the TFPI-2 promoter region identified a potential Kruppel-like factor 6 (KLF6) binding site, suggesting that the aberrant DNA methylation in the KLF6 binding site diminishes the binding of transcription factor KLF6 to the TFPI-2 promoter to decrease TFPI-2 expression. Furthermore, Konduri et al. reported that methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2) was associated with the methylated TFPI-2 promoter using a ChIP assay in human glioma cells [32]. The loss of MeCP2 from the activated TFPI-2 after combined treatment with 5-azaDC and TSA delineated the interplay between histone deacetylation and DNA methylation in the gene-silencing machinery. Together our findings corroborate the earlier conclusion that both promoter methylation and chromatin histone modification play important roles in TFPI-2 down-regulation.

Consistent with our in vitro data showing that TFPI-2 restoration neither suppressed cell proliferation nor promoted cell apoptosis, the tumor size did not differ significantly between IG- and TIG- transduced OSCC cells in a subcutaneous OSCC xenograft model in animals (data not shown). Although TFPI-2 has been found to reduce the cell proliferation rate in various human tumors [40,43–46] by triggering apoptosis [24,44], it has been suggested by some that TFPI-2 has no antiproliferation effect [47–49]. Therefore, the effect of TFPI-2 on cell proliferation and apoptosis may be complex and cell-type specific.

In the present study we demonstrated that TFPI-2 restoration could significantly abolish the invasiveness of OCSL and OC2 cells, but had no inhibitory effect on cell migration. Although TFPI-2 was previously shown to reduce tumor cell invasiveness, the findings regarding its influences on cell migration have been controversial [40,43,45,47,48]. As an inhibitor of ECM degradation, TFPI-2 has been described as an indirect inhibitor of MMPs via plasmin inhibition [27,45,47]. Our data also showed that TFPI-2 counteracts tumor invasion by negatively regulating MMP-2 activation, consistent with the finding that TFPI-2 is associated mainly with the inhibition of ECM degradation [13]. As also reported by Izumi et al. [27], TFPI-2 suppressed cell invasion via the down-regulation of the level of active MMP-2 to interfere with the process of tumor metastasis. In addition, we successfully established a metastatic tumor model in animals by the intravenous injection of TFPI-2-expressing OC2 cells, and observed a marked inhibitory effect of TFPI-2 in the formation of lung tumor nodules, demonstrating that TFPI-2 is a silenced tumor suppressor gene in OSCC.

Conclusions

The significance of the reported differential pattern of TFPI-2 hypermethylation between normal oral and OSCC tissues makes it a promising biomarker for the early detection of OSCC. TFPI-2 expression in OSCC can be reactivated after combined treatment with 5-azaDC and TSA, revealing a synergistic regulation of DNA methylation and histone deacetylation in TFPI-2 silencing. Our data suggest that TFPI-2 is a down-regulated tumor suppressor gene in OSCC, and that loss of TFPI-2 expression is a key event in oral tumorigenesis.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence (DOH102-TD-B-111-004) and the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC99-2320-B-194-004-MY3).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YHL performed the laboratory experiments and the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. RYH and JLC contributed in the laboratory works. MWYC participated in the project design. YFL was responsible for collecting clinical samples and performed the statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. CKT conceived and coordinated the overall study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yi-Hui Lai, Email: psynicki@gmail.com.

Ru-Yin He, Email: ishucka@gmail.com.

Jian-Liang Chou, Email: alien0937@gmail.com.

Michael W-Y Chan, Email: biowyc@ccu.edu.tw.

Yu-Fen Li, Email: yufenli@mail.cmu.edu.tw.

Chien-Kuo Tai, Email: biockt@ccu.edu.tw.

References

- 1.Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health, Executive Yuan, ROC (TAIWAN): 2009 Statistics of Causes of Death. Taipei: 2010.

- 3.Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK, Winn DM, Austin DF, Greenberg RS, Preston-Martin S, Bernstein L, Schoenberg JB, Stemhagen A, Fraumeni JF., Jr Smoking and drinking in relation to oral and pharyngeal cancer. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3282–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashibe M, Brennan P, Benhamou S, Castellsague X, Chen C, Curado MP, Dal Maso L, Daudt AW, Fabianova E, Fernandez L, Wunsch-Filho V, Franceschi S, Hayes RB, Herrero R, Koifman S, La Vecchia C, Lazarus P, Levi F, Mates D, Matos E, Menezes A, Muscat J, Eluf-Neto J, Olshan AF, Rudnai P, Schwartz SM, Smith E, Sturgis EM, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Talamini R, et al. Alcohol drinking in never users of tobacco, cigarette smoking in never drinkers, and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;777:789. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao CT, Chang JT, Wang HM, Ng SH, Hsueh C, Lee LY, Lin CH, Chen IH, Huang SF, Cheng AJ, Yen TC. Analysis of risk factors of predictive local tumor control in oral cavity cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:915–922. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9761-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ko YC, Huang YL, Lee CH, Chen MJ, Lin LM, Tsai CC. Betel quid chewing, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption related to oral cancer in Taiwan. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:450–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1995.tb01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jerjes W, Upile T, Petrie A, Riskalla A, Hamdoon Z, Vourvachis M, Karavidas K, Jay A, Sandison A, Thomas GJ, Kalavrezos N, Hopper C. Clinicopathological parameters, recurrence, locoregional and distant metastasis in 115 T1-T2 oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Head Neck Oncol. 2010;2:9. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo WL, Kao SY, Chi LY, Wong YK, Chang RC. Outcomes of oral squamous cell carcinoma in Taiwan after surgical therapy: factors affecting survival. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:751–758. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyle JO, Hakim J, Koch W, van der Riet P, Hruban RH, Roa RA, Correo R, Eby YJ, Ruppert JM, Sidransky D. The incidence of p53 mutations increases with progression of head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4477–4480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Field JK. Genomic instability in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:2421–2431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Field JK, Kiaris H, Howard P, Vaughan ED, Spandidos DA, Jones AS. Microsatellite instability in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Br J Cancer. 1995;71:1065–1069. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw R. The epigenetics of oral cancer. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao CN, Reddy P, Liu Y, O’Toole E, Reeder D, Foster DC, Kisiel W, Woodley DT. Extracellular matrix-associated serine protease inhibitors (Mr 33,000, 31,000, and 27,000) are single-gene products with differential glycosylation: cDNA cloning of the 33-kDa inhibitor reveals its identity to tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;335:82–92. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao CN, Peavey CL, Liu YY, Lapiere JC, Woodley DT. Partial characterization of matrix-associated serine protease inhibitors from human skin cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:379–383. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12665851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herman MP, Sukhova GK, Kisiel W, Foster D, Kehry MR, Libby P, Schonbeck U. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 is a novel inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases with implications for atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1117–1126. doi: 10.1172/JCI10403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugiyama T, Ishii S, Yamamoto J, Irie R, Saito K, Otuki T, Wakamatsu A, Suzuki Y, Hio Y, Ota T, Nishikawa T, Sugano S, Masuho Y, Isogai T. cDNA macroarray analysis of gene expression in synoviocytes stimulated with TNFalpha. FEBS Lett. 2002;517:121–128. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iino M, Foster DC, Kisiel W. Quantification and characterization of human endothelial cell-derived tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:40–46. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.18.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sprecher CA, Kisiel W, Mathewes S, Foster DC. Molecular cloning, expression, and partial characterization of a second human tissue-factor-pathway inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3353–3357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butzow R, Huhtala ML, Bohn H, Virtanen I, Seppala M. Purification and characterization of placental protein 5. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;150:483–490. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(88)90546-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chand HS, Schmidt AE, Bajaj SP, Kisiel W. Structure-function analysis of the reactive site in the first Kunitz-type domain of human tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17500–17507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen LC, Sprecher CA, Foster DC, Blumberg H, Hamamoto T, Kisiel W. Inhibitory properties of a novel human Kunitz-type protease inhibitor homologous to tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Biochemistry. 1996;35:266–272. doi: 10.1021/bi951501d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konduri SD, Tasiou A, Chandrasekar N, Rao JS. Overexpression of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 (TFPI-2), decreases the invasiveness of prostate cancer cells in vitro. Int J Oncol. 2001;18:127–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanamandra N, Kondraganti S, Gondi CS, Gujrati M, Olivero WC, Dinh DH, Rao JS. Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) expressing TFPI-2 inhibits invasion, angiogenesis and tumor growth in a human glioblastoma cell line. Int J Cancer. 2005;115:998–1005. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.George J, Gondi CS, Dinh DH, Gujrati M, Rao JS. Restoration of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 in a human glioblastoma cell line triggers caspase-mediated pathway and apoptosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3507–3517. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu Z, Maiti D, Kisiel W, Duh EJ. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 is upregulated by vascular endothelial growth factor and suppresses growth factor-induced proliferation of endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2819–2825. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000248731.55781.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golino P, Forte L, De Rosa S. Inhibition of the tissue factor coagulation pathway. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2004;2:319–327. doi: 10.2174/1570161043385402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Izumi H, Takahashi C, Oh J, Noda M. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 suppresses the production of active matrix metalloproteinase-2 and is down-regulated in cells harboring activated ras oncogenes. FEBS Lett. 2000;481:31–36. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01902-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato N, Parker AR, Fukushima N, Miyagi Y, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Eshleman JR, Goggins M. Epigenetic inactivation of TFPI-2 as a common mechanism associated with growth and invasion of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2005;24:850–858. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nobeyama Y, Okochi-Takada E, Furuta J, Miyagi Y, Kikuchi K, Yamamoto A, Nakanishi Y, Nakagawa H, Ushijima T. Silencing of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 gene in malignant melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:301–307. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong CM, Ng YL, Lee JM, Wong CC, Cheung OF, Chan CY, Tung EK, Ching YP, Ng IO. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 as a frequently silenced tumor suppressor gene in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2007;45:1129–1138. doi: 10.1002/hep.21578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jee CD, Kim MA, Jung EJ, Kim J, Kim WH. Identification of genes epigenetically silenced by CpG methylation in human gastric carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1282–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konduri SD, Srivenugopal KS, Yanamandra N, Dinh DH, Olivero WC, Gujrati M, Foster DC, Kisiel W, Ali-Osman F, Kondraganti S, Lakka SS, Rao JS. Promoter methylation and silencing of the tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 (TFPI-2), a gene encoding an inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases in human glioma cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:4509–4516. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Viet CT, Schmidt BL. Methylation array analysis of preoperative and postoperative saliva DNA in oral cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3603–3611. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qin H, Chan MW, Liyanarachchi S, Balch C, Potter D, Souriraj IJ, Cheng AS, Agosto-Perez FJ, Nikonova EV, Yan PS, Lin HJ, Nephew KP, Saltz JH, Showe LC, Huang TH, Davuluri RV. An integrative ChIP-chip and gene expression profiling to model SMAD regulatory modules. BMC Syst Biol. 2009;3:73. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-3-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng AS, Jin VX, Fan M, Smith LT, Liyanarachchi S, Yan PS, Leu YW, Chan MW, Plass C, Nephew KP, Davuluri RV, Huang TH. Combinatorial analysis of transcription factor partners reveals recruitment of c-MYC to estrogen receptor-alpha responsive promoters. Mol Cell. 2006;21:393–404. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong DY, Chang KW, Chen CF, Chang RC. Characterization of two new cell lines derived from oral cavity human squamous cell carcinomas–OC1 and OC2. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:385–390. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90436-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gillan L, Matei D, Fishman DA, Gerbin CS, Karlan BY, Chang DD. Periostin secreted by epithelial ovarian carcinoma is a ligand for alpha(V)beta(3) and alpha(V)beta(5) integrins and promotes cell motility. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5358–5364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shichinohe T, Bochner BH, Mizutani K, Nishida M, Hegerich-Gilliam S, Naldini L, Kasahara N. Development of lentiviral vectors for antiangiogenic gene delivery. Cancer Gene Ther. 2001;8:879–889. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ehrlich HJ, Gebbink RK, Preissner KT, Keijer J, Esmon NL, Mertens K, Pannekoek H. Thrombin neutralizes plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) that is complexed with vitronectin in the endothelial cell matrix. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1773–1781. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.6.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jia Y, Yang Y, Brock MV, Cao B, Zhan Q, Li Y, Yu Y, Herman JG, Guo M. Methylation of TFPI-2 is an early event of esophageal carcinogenesis. Epigenomics. 2012;4:135–146. doi: 10.2217/epi.12.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wojtukiewicz MZ, Sierko E, Zimnoch L, Kozlowski L, Kisiel W. Immunohistochemical localization of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 in human tumor tissue. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90:140–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo H, Lin Y, Zhang H, Liu J, Zhang N, Li Y, Kong D, Tang Q, Ma D. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 was repressed by CpG hypermethylation through inhibition of KLF6 binding in highly invasive breast cancer cells. BMC Mol Biol. 2007;8:110. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-8-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang Z, Geng G, Huang Q, Xu G, Hu H, Chen J, Li J. Expression of tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 in human pancreatic carcinoma and its effect on tumor growth, invasion, and migration in vitro and in vivo. J Surg Res. 2011;167:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qin Y, Zhang S, Gong W, Li J, Jia J, Quan Z. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 inhibits gallbladder carcinoma growth in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:723–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gessler F, Voss V, Seifert V, Gerlach R, Kogel D. Knockdown of TFPI-2 promotes migration and invasion of glioma cells. Neurosci Lett. 2011;497:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou Q, Xiong Y, Chen Y, Du Y, Zhang J, Mu J, Guo Q, Wang H, Ma D, Li X. Effects of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 expression on biological behavior of BeWo and JEG-3 cell lines. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2012;18:526–533. doi: 10.1177/1076029611429785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaud G, Iochmann S, Guillon-Munos A, Brillet B, Petiot S, Seigneuret F, Touze A, Heuze-Vourc'h N, Courty Y, Lerondel S, Gruel Y, Reverdiau P. TFPI-2 silencing increases tumour progression and promotes metalloproteinase 1 and 3 induction through tumour-stromal cell interactions. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:196–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ran Y, Pan J, Hu H, Zhou Z, Sun L, Peng L, Yu L, Liu J, Yang Z. A novel role for tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 in the therapy of human esophageal carcinoma. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:41–49. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lakka SS, Konduri SD, Mohanam S, Nicolson GL, Rao JS. In vitro modulation of human lung cancer cell line invasiveness by antisense cDNA of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2000;18:239–244. doi: 10.1023/A:1006755223357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]