Abstract

Although a wide variety of genetic and nongenetic Alzheimer's disease (AD) risk factors have been identified, their role in onset and/or progression of neuronal degeneration remains elusive. Systematic analysis of AD risk factors revealed that perturbations of intraneuronal signalling pathways comprise a common mechanistic denominator in both familial and sporadic AD and that such alterations lead to increases in Aβ oligomers (Aβo) formation and phosphorylation of TAU. Conversely, Aβo and TAU impact intracellular signalling directly. This feature entails binding of Aβo to membrane receptors, whereas TAU functionally interacts with downstream transducers. Accordingly, we postulate a positive feedback mechanism in which AD risk factors or genes trigger perturbations of intraneuronal signalling leading to enhanced Aβo formation and TAU phosphorylation which in turn further derange signalling. Ultimately intraneuronal signalling becomes deregulated to the extent that neuronal function and survival cannot be sustained, whereas the resulting elevated levels of amyloidogenic Aβo and phosphorylated TAU species self-polymerizes into the AD plaques and tangles, respectively.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease involves a gradual decline of synaptic function which is clinically presented as dementia [1, 2]. AD brains are defined by the presence of two different protein aggregates: plaques and tangles. Plaques are assemblies of extracellularly deposited Aβ peptides predominantly comprising the Aβ40 and the highly amyloidogenic Aβ42 peptides. These peptides are the products of sequential processing of APP (amyloid precursor protein) by BACE1 and γ-secretase [3]. It is generally assumed that in AD homeostasis of Aβ40 and 42 species is altered resulting in increased formation of oligomeric Aβ (Aβo) and subsequent aggregation into plaques. Tangles comprise intracellular assemblies of hyperphosphorylated TAU, a protein which as monomer—among other functions—binds to and stabilizes microtubules [4, 5]. There is high degree of consensus that in AD kinase and/or phosphatase activities are deregulated, resulting in hyperphosphorylation of TAU. TAU then loses its ability to bind to microtubules and consequently acquires a high propensity to oligomerise and further aggregate in tangles [6].

Decades of AD research have culminated in a wealth of data on virtually every aspect of AD etiology and pathogenesis. This has led to detailed insights into the mechanisms of AD, such as APP processing or TAU-phosphorylation, but a coherent picture encompassing AD pathology (i.e., cause/etiology, mechanisms of development, structural changes of neurons, and clinical manifestations) is still in its infancy. This review attempts to contribute to this discussion by proposing mechanisms that may help to design a conceptual framework of AD pathology.

2. Intraneuronal Signaling and Endocytosis Are Dysregulated in AD Leading to Increased Aβo Formation and TAU-Phosphorylation, which in Turn Further Derange Signalling

2.1. Aβ Oligomers Impact Intraneuronal Signalling in Familial AD

Sporadic AD is often phrased as idiopathic to emphasise that the cause of the neuronal degeneration and symptoms is unknown. Although undoubtedly true for individual patients, epidemiological studies have revealed several positive and negative AD risk factors which may hold clues as to the mechanism of AD pathogenesis (Table 1). Remarkably, these risk factors are highly diverse, consisting of genetic, lifestyle, and environmental cues with various degrees of disease penetrance. For instance, ApoE variants and zygosity are either protective against or strongly increase the risk of AD [7]. Ageing, smoking, traumatic brain injury, or metabolic diseases such as diabetes are examples of nongenetic modifiers [8]. In rare familial cases mutations in APP or its processing machinery comprise highly penetrant risk factors which in itself suffices to trigger AD.

Table 1.

Sporadic and familial AD risk genes and nongenetic positive risk factors and possible pathogenic mechanisms [8, 132].

| Risk factor | Possible mechanism(s)∗ | References∗∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ homeostasis | Cellular signaling | ||

| Genetic | |||

| APP | APP processing | Erk1/2 | [61] |

| PS1 | Change in Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio | Wnt-signalling, Erk1/2, Akt, and Ca2+ signaling | [61, 64–66, 133] |

| PS2 | APP processing | Erk1/2 | [65, 134, 135] |

| BACE | APP processing | cAMP-PKA-CREB signaling | [68] |

| ApoE4 | Aβ clearance | Erk1/2, JNK | [136–140] |

| SORLA | APP processing | Neurotrophin signaling | [137, 141, 142] |

| EPHA1 | ? | Ephrin signalling (Erk1/2) | [143, 144] |

| MS4A6A/MS4A4A | ? | Signalling | [132] |

| CD2AP | ? | PI3K-Akt-GSK3 (podocytes) | [145] |

| CLU | Aβ sequestering | Leptin/clusterin signalling; p53-Dkk1-JNK pathway | [146–148] |

| β2-AR | ? | PKA, Erk1/2, and JNK | [149, 150] |

| CD33 | Aβ clearance | [151] | |

| PICALM | APP processing | Regulation of receptor-mediated endocytosis? | [152] |

| BIN1 | APP processing | Ca2+ dyshomeostasis | [153] |

| ABCA7 | Aβ clearance | ? | [154] |

|

| |||

| Nongenetic | |||

| Smoking | ? | Erk1/2 activation by oxidative stress | [155, 156] |

| Obesity | ? | Cytokine-induced activation of MAPKs (p38, JNK); leptin signalling | [157–160] |

| Traumatic brain injury (TBI) | APP processing | Activation of MAPKs (Erk1/2, p38, and JNK), Akt, GSK3β | [8, 161] |

| Type II diabetes | ? | Insulin signalling, cytokine-induced activation of MAPK's (p38, JNK) | [158–160, 162] |

| Stress (hormones) | ? | Glucocorticoid-induced activation of Erk1/2, JNK; oxidative stress-induced JNK-dependent APP processing | [163–166] |

| Anaesthetics | Activation of MAPKs (Erk1/2, JNK) | [167–170] | |

| Ageing | APP processing | Impaired Ca2+ dyshomeostasis and signalling, elevated cytokine signalling (“inflammaging”), impaired mitochondrial function with altered redox signalling (MAPKs, PI3K/Akt) |

[171–174] |

∗Not exhaustive. ∗∗Including reviews with original research papers cited.

Irrespective of their nature and origin, at a certain point these risk factors converge to a common mechanism involving synaptic failure, Aβ and TAU pathology, and subsequent neuronal loss. Thus, a key question of understanding AD is not what causes AD, as these are multifactorial and heterogeneous among patients, but how these may converge mechanistically to trigger AD pathology. Once understood, principally every condition impacting this mechanism could be considered as contributing to AD and effective therapeutic options targeting this mechanism could be rationalised for treating AD.

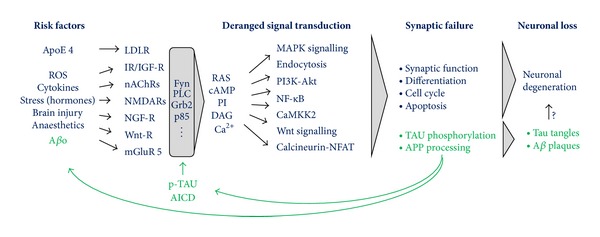

The discovery of genetic risk factors causing early onset AD has been extremely instructive to reveal such common mechanism since in these exceptional cases only one defined cause, namely, altered APP processing, triggers AD providing an relatively “simple” paradigm to investigate pathogenesis. From numerous studies on the mechanism of APP-dependent neurotoxicity, a picture emerges in which Aβo, but not plaques or monomers, comprises prime candidates responsible for synaptic failure, TAU-phosphorylation, and neuronal loss [9–15]. Also the AICD, another APP processing product, may play a role here [16–18]. Aβo has been shown to bind directly to, or modulate indirectly, numerous neuronal receptors [19] implying that these impact synaptic signalling cascades including MAPK, Akt, Wnt, and Rho pathways (summarized in Table 2 with references and Figure 1). It appears that Aβo acts as a nonspecific pathological receptor ligand/agonist, both at the pre- and postsynaptic membrane. In addition, Aβo binds to membranes directly which appear to involve GM1 ganglioside and as such are thought to induce structural and functional changes which may impact Ca2+ signalling and synaptic plasticity [20, 21]. A global impact of Aβo on different signalling pathways and their respective signalling components is consistent with the widely held view that kinase and phosphatase activities are imbalanced early on in the pathogenesis in diseased neurons [22], resulting in improper hyperphosphorylation of downstream substrates including TAU [6, 23].

Table 2.

Neuronal receptors impacted by Aβo [19, 175] and possible effects on downstream signalling pathways.

| Receptor | Signal transduction pathway | References∗ |

|---|---|---|

| NMDAR (NR2B subtype) | Erk1/2, CamKIV | [95, 176–182] |

| mGluR5 (with PrPC) | PKC, MAPKs (Erk1/2, p38, and JNK) | [79] |

| nAchR (α7 subtype) | Erk1/2, Akt, and JAK-STAT | [183, 184] |

| Wnt receptor | Wnt signalling (GSK3) | [185, 186] |

| IR/IGF | PI3K-Akt | [176, 187] |

| Amylin receptor | Erk1/2, PKA | [177] |

| RAGE | p38 | [188] |

| Neurotrophin receptors | Erk1/2, Akt | [45, 189] |

| β2AR | PKA, Erk1/2, and JNK | [149, 190, 191] |

∗Including reviews with original research papers cited.

Figure 1.

APP, its processing products and TAU are part of an intraneuronal signalling network required for neurogenesis, neuronal function, and survival which go awry in AD. Aβo and AD risk factors modulate receptor mediated intraneuronal signalling and endocytosis which impacts Aβ homeostasis and TAU-phosphorylation. TAU-hyperphosphorylation leads to decreased microtubule binding, somatodendritic redistribution, and altered signalling. Apart from a modulatory role of Aβo, AICD, and phosphorylated TAU on signalling, their formation is also controlled by signalling implying a positive feedback loop which could overtime lead to a dysfunction of signalling cascades underlying synaptic integrity and neuronal survival. High levels of Aβo and hyperphosphorylated-TAU species will, due to their intrinsic amyloidogenic propensity, ultimately aggregate into plaques and tangles. Risk factors which impact these signalling processes, either directly or indirectly (i.e., through impacting Aβo levels), will set off this cascade of events culminating in synaptotoxicity and pathology. Note that the schematic is highly simplified and intended to depict general principles. For a more exhaustive insight into the signalling pathways impacted in AD, see [30]. Abbreviations are as follows: LDLR: low density lipoprotein receptor; IR: insulin receptor; IGF-R: insulin-like growth factor receptor; nACHR: nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; NMDAR: N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor; NGF-R: nerve growth factor receptor; Wnt: Wingless Int; PrPc: cellular prion protein; RAS: rat sarcoma; cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate; PI: phosphoinositides; DAG: 1,2-diacylglycerol; mGluR5: metabotropic glutamate receptor; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; CamKK2: calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 2; and NFAT: nuclear factor of activated T-cells.

Also APP processing itself is controlled by signal transduction pathways. GPCR's, like GPR3 and β2-adrenergic, receptors mediate their effects on APP processing through interaction with β-arrestin and γ-secretase [24, 25]. Activation of JNK3 MAPK by Aβo phosphorylates APP at T668, thereby increasing its endocytosis and subsequent processing [26, 27]. Also, Ras-Erk1/2 and PI3K-Akt signalling pathways activate APP-expression [28] or PS1, a subunit of the APP processing machinery [29]. These results suggest that Aβo increases its own formation by modulating APP processing through these signalling pathways (Figure 1).

2.2. Signalling and Endocytosis: Intimate Partners in Crime

Cell signalling and endocytosis are increasingly recognized as intertwined and bidirectionally controlled processes [31–33]. Receptor internalisation by endocytosis is a common response upon ligand binding to desensitize cells. Internalised receptors are shuttled to early endosomes, which act as a sorting station for recycling to the plasma membrane or to the lysosome for degradation. Signal propagation is not restricted to the plasma membrane but (may) continue(s) after internalisation. Endosomes marked with active signalling pathways, referred to as signalling endosomes [34], prolong and even intensify signalling while transported through the cell. To illustrate this, activation of the NGF receptor at the presynaptic membrane transiently activates RAS-Erk1/2 signalling [31, 35]. Upon internalization, signalling is sustained as NGF-receptors remain actively coupled with Erk1/2, however, in this context via RAP1, while being transported to the nucleus in order to phosphorylate substrates such as CREB and Erk5. Another example of a close link between signalling and endocytosis entails Wnt signalling. Here, internalization of activated receptors is required to control GSK3 activity and β-catenin stability [36, 37]. Conversely, signalling controls the endocytic pathway itself by impacting the phospholipid turnover. Increases of PIP3 by activation of PI3K allows (apart from Akt) membrane recruitment of Rho and Arf GEFs and GAPs in turn modulating their respective GTPases involved in vesicular trafficking (among other functions such as cytoskeletal rearrangement) [38].

As discussed above, intracellular signalling is deregulated in AD by risk factors and Aβo and thus inevitably will impact endocytosis. Indeed, sporadic AD is characterised by an abnormal activation of the endocytic pathway, with associated increases in PI3K and RAS signalling and Rab5 levels, and comprises early neuropathological alteration even before Aβ pathology ensues [39–41]. Consistent with its role as a pathological receptor ligand, Aβo also increases internalisation of receptors by endocytosis [42–44]. An even more general effect on the endocytic pathway is expected by Aβo triggered receptor-mediated activation of phospholipid signalling through neurotrophin or insulin signalling pathways [45–48]. Likewise, stress-activated p38 MAPK, a kinase activated in AD, stimulates Rab5 which leads to acceleration of endocytosis [49].

Note that AICD, another APP processing product, activates signalling through interaction with Shc and Grb2, adaptor proteins that link with Ras/Erk1/2 and PI3K/Akt pathways (reviewed in [18]) and (perhaps as a consequence) trigger endocytic dysfunction [16]. In addition, GSK3 is also increased by AICD through inhibition of Wnt signalling [50]. Thus, apart from Aβo, other APP processing products also impact signalling and endocytosis in AD and may therefore, at least in part, contribute to the development of AD pathology independently of Aβ [17].

As BACE1 and γ-secretase are localised at endosomes, amyloidogenic, neurotoxic processing of APP requires endocytosis [51–54] and is controlled by vesicular trafficking [55]. Conditions that alter the residence time and/or levels of APP or its processing enzymes at the endocytic compartment impact Aβ production or clearance accordingly [55–58]. For instance, Arf6, a small GTPase controlled by phospholipid signalling, mediates endosomal sorting of BACE1 and thereby APP processing [59]. Or the already abovementioned JNK-driven phosphorylation of APP at T668 facilitates its endocytosis and processing [27]. Similarly, ApoE receptors facilitate the internalization of APP to the endosomal compartment [60].

Taken together, the processing of APP is controlled by signalling pathways which impact expression and endocytic localisation of APP and its processing machinery. Thus, aberrant activation of pathways that increase endocytic APP levels also allows more processing and hence elevates Aβo and AICD formation. This model implies a positive feedback loop as APP processing itself is activated by its own products through signalling (Figure 1). In this way, subtle genetic or nongenetic AD risk factors which lead to relatively small perturbations of signal transduction pathways could, if unchecked, trigger over time a large buildup of Aβo/AICD and thus amplify these subtle alterations into large derangements of signalling and associated endocytosis.

2.3. Derailed Intraneuronal Signalling Is a Common Denominator in Sporadic and Familial AD

As discussed above, in familial AD increased formation of Aβo impacts receptor-mediated signalling. In addition, APP, its processing machinery, and the AICD impact signalling independent of Aβ formation (reviewed in [61]). For instance, PS1, a subunit of the γ-secretase complex, cleaves numerous transmembrane signalling receptors and transducers other than APP CTFs, including Notch, cadherins, ErbB4, LDL receptor related proteins, and so forth [62, 63]. In addition, PS1 and PS2 impact signalling pathways directly. Deletion of PS1 and/or PS2 activates Erk1/2 activity in cell line models, whereas an early onset FAD mutation in PS1 results in constitute activation of CREB-phosphorylation which is associated with neurodegeneration [64–67] and BACE1 regulates the cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway independent of Aβ [68]. Thus, APP and components of its processing machinery impact neuronal signalling pathways independent of APP processing. Hence, FAD mutations can modulate signalling in potentially two ways: through elevated Aβo formation via abnormal APP processing and/or independently of Aβ through altered interactions with signalling pathways. Perhaps through these combined effects on signalling such mutations represent particularly aggressive and penetrant forms of AD.

Considering that signalling and associated endocytosis is abnormal in FAD, it begs the question how this relates to sporadic AD. As amyloidogenic processing of APP is controlled by signalling and endocytosis, it is highly relevant to observe that AD risk factors, although very heterogeneous, have common mechanistic underpinnings by impacting intracellular signal transduction pathways (summarized in Table 1). For example, ApoE4 and traumatic brain injury, two entirely unrelated AD risk factors, both directly activate common signalling pathways (such as Erk1/2). In fact, for most nongenetic AD risk factors no direct impact on Aβ homeostasis can be hypothesized but involve altered signalling. Metabolic disorders like obesity or diabetes are associated with high levels of cytokines which activate AD relevant pathways in neurons. Likewise, glucocorticoids produced under conditions of chronic stress impact AD relevant signalling cascades in their own right. AD risk factors, such as stroke or head injury involve glutamate receptor-mediated excitotoxicity and impact Ca2+ signalling in a way which mechanistically resembles Aβo-instigated activation of Erk1/2 by NMDA receptors. Ageing, the most prominent risk factor for AD, involves, apart from the abovementioned risk factors, altered redox signalling as a result of age-related decline of mitochondrial activity with concomitant increases in ROS production.

In summary, a common denominator in both FAD and sporadic AD comprises perturbation of intraneuronal signalling with associated changes in the endocytic pathway. As outlined above this may result in a vicious, self-enforcing cycle of deranged signalling and Aβ production driving the pathogenesis (Figure 1). In early onset FAD, this autocatalytic mechanism is directly and potently impacted by mutations in APP or its processing machinery. In late onset and sporadic AD initial, probably relatively minor, alterations of signalling by one or more AD risk factors may overtime set off this mechanism which once in motion drives AD pathogenesis.

This scenario resembles a domino system where tumbling of the stones (deranged signalling) is both cause and effect (autocatalytic effect), yet in order to let it happen a “risk factor” such as a sufficiently strong push, windfall, or vibration, is required to set off the cascade. To extent the metaphor further, FAD mutations could be seen as alterations of the core autocatalytic mechanism itself, for instance, as thinner domino stones, which make the system more unstable and thus more sensitive to risk factors. The opposite may be true for “protective” APP mutations (thicker stones, more resilient to risk factors) like the recently discovered Icelandic mutation which decreases APP processing [69].

From this perspective it can be envisaged that AD risk factors comprise a patient-specific constellation which determine the onset and progression of altered signalling and consequently AD pathogenesis. By extension any genetic, environmental, pharmacological, or lifestyle factor impacting this mechanism can, depending on the direction of the effect, be considered as a positive or negative AD risk factor.

2.4. A Signalling Function of Phosphorylated TAU Contributes to AD Pathogenesis

Besides Aβ polymerization and deposition into plaques, hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of TAU into intracellular tangles are other pathological features of AD. The identification of clinical mutations in TAU leading to FTLD strongly suggests that TAU in AD has an important role in pathogenesis [70–72]. Consistent with this notion, in many experimental paradigms a TAU-dependent neuronal degeneration was observed [23]. However, a key question remains as to the mechanism involved especially in relation to changes in signalling and Aβ homeostasis.

A study in transgenic APP mice, a model of early onset AD without TAU-tangle formation, revealed that deletion of the endogenous TAU mouse gene rescues cognitive decline without impacting plaque formation [73]. These findings position TAU as a downstream mediator required for APP-instigated neuronal toxicity, a feature not involving a loss-of-function (i.e., decreased microtubule stabilization), but a gain-of-toxic function which, however, does not involve TAU tangles [74]. Instead it was shown that TAU regulates postsynaptic NMDAR signalling directly by a mechanism involving recruitment of Src kinase Fyn to the PSD95-NMDA receptor complex [75, 76]. Combined with the observation that, like deletion of TAU, lowering of NMDAR-Erk1/2 signalling rescues APP-driven toxicity [75, 77] it appears that in AD such TAU function potentiates NMDA receptor signalling [76, 78]. Likewise, Aβo activation of the mGluR5 receptor through PrPC may also involve Fyn-TAU interaction [26, 79]. In other words TAU has, besides its well-known function in binding and stabilizing microtubules, a role in intracellular signalling. This raises the distinct possibility that when TAU's signalling activity goes awry it may contribute to AD pathogenesis.

Albeit TAU's signalling function is a somewhat neglected feature, a far more general role of TAU in signalling (apart from impacting NMDA receptors) can be considered. Table 3 shows numerous TAU interactors which are transducers of receptor-mediated signalling implying that TAU can modify their activity through these interactions. These interactors function in a variety of pathways both pre- and postsynaptically. Indeed, apart from impacting postsynaptic NMDA receptor activity, TAU activates presynaptic growth factor signalling through interaction with Src family kinases [80–82] or phospholipid signalling by activation of PLCγ [83] and would provide a mechanistic explanation as to the role of TAU in neurite outgrowth [84, 85] and cell cycle reentry [86, 87] in cell line models.

Table 3.

| Binding partner | Region of TAU involved | Function/identity of binding partner | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-tubulin | Repeat domains | Cytoskeleton | [193] |

| F-actin | Cytoskeleton | [194] | |

| ApoE3 | Repeat domains | Lipid carrier | [195, 196] |

| Fgr | Proline-rich domain | Src kinase family | [89] |

| Fyn | Proline-rich domain | Src kinase family | [82, 89] |

| Lck | Proline-rich domain | Src kinase family | [82, 89] |

| cSrc | Proline-rich domain | Src kinase family | [82, 89] |

| Grb2 | Proline-rich domain | Growth factor signalling | [89] |

| c-Abl | Src kinase family | [197] | |

| p85α | Proline-rich domain | Regulator PI3K, phospholipid signalling | [89] |

| PLCγ | Phospholipid signalling | [89, 198] | |

| GSK3β | N-terminal | Kinase | [199] |

| Calmodulin | Repeat domain | Ca2+ signalling | [200, 201] |

| 14-3-3 | Proline-rich domain and repeat domain | Signalling scaffold | [202–204] |

| Annexin A2 | Ca2+ signalling, membrane trafficking | [205] | |

| Pin1 | Proline-rich domain | Peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase regulates phosphorylation of TAU | [206, 207] |

From Table 3 it can also be appreciated that many interactors through their SH3 domains bind to the proline-rich domain (PRD) of TAU. Notably, TAU PRD is hyperphosphorylated in AD suggesting that these interactions are controlled by TAU-phosphorylation (and indirectly the relevant signalling cascades). Quantifying the TAU-SH3 interaction by surface plasmon resonance and sedimentation assays indicated this may indeed be the case [88, 89]. Phosphorylation-mimicking mutations of TAU were shown to increase or decrease (depending on the TAU-isoform) the affinity to Fyn or Src SH3 domains, consistent with the requirement of TAU-phosphorylation for regulation of NGF-RAS-Erk1/2 signalling [80]. Moreover, clinical FTLD-causing TAU-mutations were found to strongly increase the affinity to SH3, that is, phenocopying the effects of hyperphosphorylation [88]. Thus, these mutations could directly impact signalling, similar as in AD, which may contribute to neuronal degeneration. In fact, it may provide an explanation as to the mechanism of FTLD mutations in TAU which do not impact its aggregation propensity [90] such as R406W [91–94], which possesses an increased affinity to Fyn-SH3 of about 45 times [88]. Collectively, it seems possible that deregulation of signalling by hyperphosphorylated TAU constitutes a toxic gain-of-function of TAU driving pathogenesis in AD (Figure 1).

2.5. Deregulated Signalling by Aβo or Other AD Risk Factors Triggers TAU-Hyperphosphorylation

An important question however remains as to how TAU becomes hyperphosphorylated in the first place. The facts that TAU is a substrate of many of the kinases operating in the pathways modulated by Aβo (Table 2) or by AD risk factors or genes (Table 1) and that TAU is phosphorylated by neurons challenged with Aβo or other stresses/conditions [95–98], provide a mechanistic explanation as to TAU hyperphosphorylation in AD [5, 23, 99, 100]. Once phosphorylated, TAU may impact intracellular signalling further implying a positive feedback mechanism such as that proposed for TAU-potentiated NGF-Erk1/2 activation [80] and/or by recruitment of Fyn to NMDA receptors [75].

Another salient feature entails the somatodendritic redistribution of TAU in diseased neurons, a prerequisite for impacting postsynaptic signalling. This feature of TAU is controlled by phosphorylation of microtubule binding repeat domains which strongly reduces its affinity to microtubules [101]. Hyperphosphorylation of TAU (and presumably detachment from microtubules) is a prerequisite—by an as yet unclear mechanism—to cross an axonal diffusion barrier allowing TAU to invade the somatodendritic space [102]. Phosphorylation of TAU at the repeat domains, in particular Ser262, is required to elicit Aβ-instigated neurotoxicity [95, 103, 104], indicating that detachment from microtubules entails an important feature of AD pathogenesis. Moreover, Ser262 is one of the earliest sites phosphorylated in the course of pathogenesis [22] and its phosphorylation acts as a priming site for further, more extensive phosphorylation at sites that may control its signalling function [105]. These results indicate a sequential mechanism of TAU-phosphorylation by Aβo and other AD risk factors affecting its subcellular distribution and signalling.

Collectively TAU-phosphorylation comprises a gain-of-toxic function driving AD pathogenesis. Activation of signalling pathways by Aβo and/or by other triggers (see Table 1) leads to hyperphosphorylation of TAU which subsequently decreases its microtubule binding and alters its somatodendritic redistribution and signalling function. These effects may be amplified by a feedback mechanism as formation of Aβo and phosphorylated TAU not only control but are also controlled by signalling (Figure 1). The resulting deregulation of intraneuronal signalling contribute to neurodegeneration (see below), whereas the elevated levels of Aβo and phosphorylated TAU, which have a high propensity to aggregate, lead to Aβ plaques and TAU tangles.

3. Considerations on the Mechanism of Altered Signalling in Neurodegeneration

3.1. Intraneuronal Signalling Defines Fate and Function of a Neuron for Better and for Worse

As discussed above deregulation of signalling may drive the neuronal degeneration in AD. The question, however, remains as to how mechanistically “deregulation” of pathways lead to neuronal degeneration. Neuronal function and survival depend on a balance between neurotrophic and neurotoxic cues setting off signalling cascades which define the outcome ranging from proliferation, differentiation, synaptic plasticity to apoptosis. A classical example entails growth factor signalling which sustains neuronal survival and can trigger differentiation or even antagonize the effects of toxic insults, whereas neurons without sufficient trophic support are prone to undergo apoptosis, as it occurs in a developing nervous system [106, 107]. Thus, properly regulated and balanced signalling, in function of its developmental state, defines fate and function of a neuron [108]. Accordingly, pathological conditions, such as in AD, which off-balance signalling are expected to decrease neuronal integrity.

The underlying mechanisms of how signalling leads to altered neuronal function are poorly understood but extensive work on Erk1/2 signalling revealed insights which may be applicable to other neuronal signalling pathways as well [109]. Erk1/2 signalling is particularly relevant for AD since its aberrant activation is an important driver of neurodegeneration [109, 110]. Erk1/2 kinases are responsive to a wide variety of functional (learning and memory), trophic, and pathogenic stimuli leading to different, even opposing, outcomes including survival, proliferation, differentiation, and neuronal cell death [110–112]. Thus, the signal as such is not predictive of the outcome and additional layers of control exist to determine specificity of Erk1/2 activation. Compartmentalization is a prominent mechanism to ensure specificity as it directs and concentrates the kinase (or sometimes the whole signalling pathway) to appropriate substrates within the cell [113]. This remarkable feature involves several scaffold, anchor, and retention factors which bind to Erk1/2 and often also other signalling molecules determining its subcellular action and allowing crosstalk with other pathways [113].

Localisation of Erk1/2 to specify its output is in part controlled by the kinetics of the signal (reviewed in [114, 115]). During transient activation, Erk1/2 remains predominantly cytoplasmic promoting proliferation, whereas its sustained activation is needed for nuclear concentration and results in differentiation. Chronic stress causes prolonged Erk1/2 activation in the nucleus which contributes to cell death [109, 116]. Thus, the widely different outcomes of Erk1/2 signalling depends, at least in part, on its kinetics as it dictates its subcellular localisation and as such specifies accessibility of substrates (reviewed in [113, 115]). In several model systems, sustained Erk1/2 activation involves a nuclear accumulation which is associated with detrimental outcomes [116–120]. For instance, neurons challenged with stress trigger a persistent nuclear retention of activated Erk1/2 and elicit proapoptotic effects and cell death [109, 116]. Accordingly, it seems likely that the chronic activation of Erk1/2 in AD, presumably by Aβo and possibly other risk factors (see Tables 1 and 2), leads to an aberrant, prolonged nuclear accumulation contributing to neuronal demise.

3.2. Diseased Neurons in AD Display Signalling Configured for Immature Neurons

The insights obtained from the studies on Erk1/2 revealed that spatiotemporal control of Erk1/2 signalling determines its impact on neuronal function and survival [109] and as such provide a conceptual framework of the underlying mechanisms as to how derailed Erk1/2 signalling contributes to neuronal degeneration in AD. We anticipate that this concept is likely applicable to other signalling pathways as well.

In fact hyperphosphorylation of TAU in AD can be considered a reflection of such global deregulation of signalling in adult neurons [6] and illustrates how this may lead to inappropriate outcomes in function of the developmental state. As outlined above, hyperphosphorylation of TAU may lead to increased microtubule dynamics and the potentiating of pathways (such as Erk1/2) resulting in aberrant cell cycle entry and apoptosis. Such functional outcomes are expected to be detrimental in mature, postmitotic neurons of the adult brain. However, in a developing brain hyperphosphorylated TAU is fully appropriate as, in this context, neurons require dynamic microtubules to mediate sufficient synaptic plasticity, proliferation, and differentiation but also susceptibility to undergo apoptosis when trophic support by target cells is insufficient [108]. In other words, neuronal signalling in AD involving TAU-hyperphosphorylation appears to be geared to a situation resembling an immature brain.

Perhaps, a similar situation may apply for APP and its processing as well, given the neurotrophic properties of APP and its cleavage products [121]. Addition of APP to PC12 cells stimulates neurite outgrowth [122], whereas in transgenic mice expression of human APP results in increased neurogenesis [123, 124]. Moreover, the AICD promotes signalling associated with neurite outgrowth [18, 50], and secreted sAPPα impacts proliferation of embryonic stem cells [125]. Remarkably, at low concentration, Aβ has neurotrophic activity but only in undifferentiated neurons but is toxic to mature neurons [126–129]. Thus, APP and its processing products may have a role in proliferation and differentiation, functions that are particularly relevant in a developing brain, but, when unchecked, toxic to mature neurons.

Collectively it can be envisaged that APP, its processing products, and TAU are part of an intraneuronal signalling network required for neurogenesis, neuronal function, and survival which needs to be appropriately tuned to the developmental status. Accordingly, pathological conditions or risk factors which off-balance such signalling network to a state resembling immature neurons will be detrimental for mature neurons.

3.3. Considerations on Drug Discovery for Alzheimer's Disease

As discussed above aberrant activation of signalling cascades underlies mechanistically neurodegeneration in AD. As such it may provide a conceptual framework for successful drug discovery as it assumes that interventions aimed at normalizing signalling are expected to be neuroprotective, to reduce Aβ levels and TAU-phosphorylation and consequently plaque and tangle formation. In this way a fundamental mechanism driving pathogenesis in AD will be targeted and thus anticipates the minimum to preserve the function of still healthy neurons in the diseased brain and possibly may even restore dysfunctional synaptic activity of affected, but still living, neurons in symptomatic patients. However, given the multitude of pathways involved and considering their important neuronal functions, pharmacological modulation of one, specific target safely to achieve that goal will be a major challenge. Another confounding factor comprises the heterogeneity of sporadic patients, presumably reflected by the heterogeneity of risk factors each with their specific effects on the nature and effect size of the signalling pathways.

Aβ-directed therapeutic approaches to reduce Aβ levels have been and are still heavily explored and are expected to normalize signalling, at least to some extent, and thus have therapeutic potential. However, a possible downside may be that in symptomatic patients TAU-hyperphosphorylation has kicked in already to a level able to derange signalling and neuronal function in a feed forward fashion independent of Aβo (from that point on perhaps mechanistically similar to how clinical TAU mutations in FTLD lead to neurodegeneration). Thus, such approach would be most successful in a preventive setup very early in the development of AD. Another consideration is that the therapeutic intervention itself should not inadvertently impact neuronal signalling for the worse. For instance, inhibiting γ-secretase will, on one hand, lead to lowered Aβo levels and most likely to cognitive improvement in transgenic APP mouse models of familial AD but on the other hand may also impact signalling pathways (such as increased Erk1/2 activity [65]), independent of APP processing, which may impair a therapeutic response in sporadic AD patients. Likewise inhibition of CDK5, a prominent TAU-kinase and considered an attractive drug target for AD [130], may lead to sustained Erk1/2 activity and consequently neuronal apoptosis [131].

Nevertheless, promising drug targets to be considered for therapeutic intervention comprise components of signalling pathways impacted in AD [6, 130] although there is a risk—given the overall deregulation of signalling—that downregulation of only one kinase (or pathway) might be too limited to result in a satisfying therapeutic response. From this perspective, an interesting point of intervention may comprise the convergence where receptors relay their environmental cues to second messengers such as Ca2+ and/or small GTPases modules (Figure 1). Downregulating, but not fully inhibiting, the activity of such relay systems may lead to a more global normalization of signalling in AD and thus may constitute a promising therapeutic avenue.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Dick Terwel and Michael Dumbacher for critically reading the manuscript.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease is a synaptic failure. Science. 2002;298(5594):789–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1074069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2011;3(7):1–16. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Brien RJ, Wong PC. Amyloid precursor protein processing and alzheimer's disease. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2011;34:185–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris M, Maeda S, Vossel K, Mucke L. The many faces of tau. Neuron. 2011;70(3):410–426. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noble W, Hanger DP, Miller CC, Lovestone S. The importance of tau phosphorylation for neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in Neurology. 2013;4, article 83 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2013.00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin L, Latypova X, Wilson CM, et al. Tau protein kinases: involvement in Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Research Reviews. 2013;12(1):289–309. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu C, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein e and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2013;9(2):106–118. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayeux R, Stern Y. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2012;2(8) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brouillette J, Caillierez R, Zommer N, et al. Neurotoxicity and memory deficits induced by soluble low-molecular-weight amyloid-β1-42 oligomers are revealed in vivo by using a novel animal model. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(23):7852–7861. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5901-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forloni G, Balducci C. β-amyloid oligomers and prion protein: fatal attraction? Prion. 2011;5(1):10–15. doi: 10.4161/pri.5.1.14367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Itkin A, Dupres V, Dufrêne YF, Bechinger B, Ruysschaert J, Raussens V. Calcium ions promote formation of amyloid β-peptide (1-40) oligomers causally implicated in neuronal toxicity of Alzheimer's disease. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018250.e18250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lublin AL, Gandy S. Amyloid-β oligomers: possible roles as key neurotoxins in Alzheimer's disease. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. 2010;77(1):43–49. doi: 10.1002/msj.20160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miñano-Molina AJ, España J, Martín E, et al. Soluble oligomers of amyloid-β peptide disrupt membrane trafficking of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid receptor contributing to early synapse dysfunction. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(31):27311–27321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.227504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ono K, Yamada M. Low-n oligomers as therapeutic targets of Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2011;117(1):19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umeda T, Tomiyama T, Sakama N, et al. Intraneuronal amyloid β oligomers cause cell death via endoplasmic reticulum stress, endosomal/lysosomal leakage, and mitochondrial dysfunction in vivo. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2011;89(7):1031–1042. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang Y, Mullaney KA, Peterhoff CM, et al. Alzheimer's-related endosome dysfunction in Down syndrome is Aβ-independent but requires APP and is reversed by BACE-1 inhibition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(4):1630–1635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908953107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosal K, Vogt DL, Liang M, Shen Y, Lamb BT, Pimplikar SW. Alzheimer's disease-like pathological features in transgenic mice expressing the APP intracellular domain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(43):18367–18372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907652106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schettini G, Govoni S, Racchi M, Rodriguez G. Phosphorylation of APP-CTF-AICD domains and interaction with adaptor proteins: signal transduction and/or transcriptional role—relevance for Alzheimer pathology. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2010;115(6):1299–1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel AN, Jhamandas JH. Neuronal receptors as targets for the action of amyloid-beta protein (Aβ) in the brain. Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine. 2012;14(article e2):19 pages. doi: 10.1017/S1462399411002134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong S, Ostaszewski BL, Yang T, et al. Soluble Aβ oligomers are rapidly sequestered from brain ISF in vivo and bind GM1 ganglioside on cellular membranes. Neuron. 2014;82(2):308–319. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ledeen RW, Wu G. Ganglioside function in calcium homeostasis and signaling. Neurochemical Research. 2002;27(7-8):637–647. doi: 10.1023/a:1020224016830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Augustinack JC, Schneider A, Mandelkow E, Hyman BT. Specific tau phosphorylation sites correlate with severity of neuronal cytopathology in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathologica. 2002;103(1):26–35. doi: 10.1007/s004010100423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stoothoff WH, Johnson GVW. Tau phosphorylation: physiological and pathological consequences. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta: Molecular Basis of Disease. 2005;1739(2):280–297. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thathiah A, De Strooper B. The role of G protein-coupled receptors in the pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2011;12(2):73–87. doi: 10.1038/nrn2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thathiah A, Spittaels K, Hoffmann M, et al. The orphan G protein-coupled receptor 3 modulates amyloid-beta peptide generation in neurons. Science. 2009;323(5916):946–951. doi: 10.1126/science.1160649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mairet-Coello G, Polleux F. Involvement of ‘stress-response’ kinase pathways in Alzheimer's disease progression. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2014;27:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoon SO, Park DJ, Ryu JC, et al. JNK3 perpetuates metabolic stress induced by Aβ peptides. Neuron. 2012;75(5):824–837. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruiz-León Y, Pascual A. Regulation of β-amyloid precursor protein expression by brain-derived neurotrophic factor involves activation of both the Ras and phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase signalling pathways. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2004;88(4):1010–1018. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitsuda N, Ohkubo N, Tamatani M, et al. Activated cAMP-response element-binding protein regulates neuronal expression of presenilin-1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(13):9688–9698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006153200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizuno S, Iijima R, Ogishima S, et al. AlzPathway: a comprehensive map of signaling pathways of Alzheimer's disease. BMC Systems Biology. 2012;6, article 52 doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-6-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sorkin A, Von Zastrow M. Endocytosis and signalling: intertwining molecular networks. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2009;10(9):609–622. doi: 10.1038/nrm2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy JE, Padilla BE, Hasdemir B, Cottrell GS, Bunnett NW. Endosomes: a legitimate platform for the signaling train. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(42):17615–17622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906541106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dobrowolski R, de Robertis EM. Endocytic control of growth factor signalling: multivesicular bodies as signalling organelles. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2012;13(1):53–60. doi: 10.1038/nrm3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zweifel LS, Kuruvilla R, Ginty DD. Functions and mechanisms of retrograde neurotrophin signalling. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6(8):615–625. doi: 10.1038/nrn1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ascano M, Bodmer D, Kuruvilla R. Endocytic trafficking of neurotrophins in neural development. Trends in Cell Biology. 2012;22(5):266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Platta HW, Stenmark H. Endocytosis and signaling. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2011;23(4):393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kikuchi A, Yamamoto H, Sato A. Selective activation mechanisms of Wnt signaling pathways. Trends in Cell Biology. 2009;19(3):119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Paolo G, De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 2006;443(7112):651–657. doi: 10.1038/nature05185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nixon RA. Endosome function and dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiology of Aging. 2005;26(3):373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cataldo AM, Peterhoff CM, Troncoso JC, Gomez-Isla T, Hyman BT, Nixon RA. Endocytic pathway abnormalities precede amyloid β deposition in sporadic alzheimer's disease and down syndrome: differential effects of APOE genotype and presenilin mutations. The American Journal of Pathology. 2000;157(1):277–286. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64538-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ginsberg SD, Alldred MJ, Counts SE, et al. Microarray analysis of hippocampal CA1 neurons implicates early endosomal dysfunction during Alzheimer's disease progression. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68(10):885–893. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagele RG, D'Andrea MR, Anderson WJ, Wang H-Y. Intracellular accumulation of β-amyloid1-42 in neurons is facilitated by the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience. 2002;110(2):199–211. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goto Y, Niidome T, Akaike A, Kihara T, Sugimoto H. Amyloid β-peptide preconditioning reduces glutamate-induced neurotoxicity by promoting endocytosis of NMDA receptor. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;351(1):259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang D, Yuen EY, Zhou Y, Yan Z, Xiang YK. Amyloid β peptide-(1 - 42) induces internalization and degradation of β2 adrenergic receptors in prefrontal cortical neurons. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(36):31852–31863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.244335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bulbarelli A, Lonati E, Cazzaniga E, et al. TrkA pathway activation induced by amyloid-beta (Abeta) Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2009;40(3):365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stöhr O, Schilbach K, Moll L, et al. Insulin receptor signaling mediates APP processing and β-amyloid accumulation without altering survival in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Age. 2013;35(1):83–101. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9333-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O'Neill C. PI3-kinase/Akt/mTOR signaling: impaired on/off switches in aging, cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease. Experimental Gerontology. 2013;48(7):647–653. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Griffin RJ, Moloney A, Kelliher M, et al. Activation of Akt/PKB, increased phosphorylation of Akt substrates and loss and altered distribution of Akt and PTEN are features of Alzheimer's disease pathology. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;93(1):105–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cavalli V, Vilbois F, Corti M, et al. The stress-induced MAP kinase p38 regulates endocytic trafficking via the GDI:Rab5 complex. Molecular Cell. 2001;7(2):421–432. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou F, Gong K, Song B, et al. The APP intracellular domain (AICD) inhibits Wnt signalling and promotes neurite outgrowth. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2012;1823(8):1233–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cirrito JR, Kang J, Lee J, et al. Endocytosis is required for synaptic activity-dependent release of amyloid-β in vivo. Neuron. 2008;58(1):42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu C, Nwabuisi-Heath E, Laxton K, Ladu MJ. Endocytic pathways mediating oligomeric Aβ42 neurotoxicity. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2010;5(1, article 19) doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Small SA, Gandy S. Sorting through the cell biology of Alzheimer's disease: intracellular pathways to pathogenesis. Neuron. 2006;52(1):15–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu J, Petralia RS, Kurushima H, et al. Arc/Arg3.1 Regulates an endosomal pathway essential for activity-dependent β-amyloid generation. Cell. 2011;147(3):615–628. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Udayar V, Buggia-Prevot V, Guerreiro RL, et al. A Paired RNAi and RabGAP overexpression screen identifies Rab11 as a regulator of beta-amyloid production. Cell Reports. 2013;5(6):1536–1551. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Das U, Scott DA, Ganguly A, Koo EH, Tang Y, Roy S. Activity-induced convergence of app and BACE-1 in acidic microdomains via an endocytosis-dependent pathway. Neuron. 2013;79(3):447–460. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carey RM, Balcz BA, Lopez-Coviella I, Slack BE. Inhibition of dynamin-dependent endocytosis increases shedding of the amyloid precursor protein ectodomain and reduces generation of amyloid beta protein. BMC Cell Biology. 2005;6, article 30 doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Buggia-Prevot V, Fernandez CG, Udayar V, et al. A function for EHD family proteins in unidirectional retrograde dendritic transport of BACE1 and Alzheimer's disease Abeta production. Cell Reports. 2013;5(6):1552–1563. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sannerud R, Declerck I, Peric A, et al. ADP ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6) controls amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing by mediating the endosomal sorting of BACE1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(34):E559–E568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100745108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ulery PG, Beers J, Mikhailenko I, et al. Modulation of β-amyloid precursor protein processing by the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP). Evidence that LRP contributes to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(10):7410–7415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nizzari M, Thellung S, Corsaro A, et al. Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer disease: role of amyloid precursor protein and presenilin 1 intracellular signaling. Journal of Toxicology. 2012;2012:13 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/187297.187297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vetrivel KS, Zhang Y, Xu H, Thinakaran G. Pathological and physiological functions of presenilins. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2006;1(1, article 4) doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Haass C, de Strooper B. The presenilins in Alzheimer's disease—proteolysis holds the key. Science. 1999;286(5441):916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Müller M, Cárdenas C, Mei L, Cheung K, Foskett JK. Constitutive cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) activation by Alzheimer's disease presenilin-driven inositol trisphosphate receptor (InsP3R) Ca2+ signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(32):13293–13298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109297108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dehvari N, Isacsson O, Winblad B, Cedazo-Minguez A, Cowburn RF. Presenilin regulates extracellular regulated kinase (Erk) activity by a protein kinase C alpha dependent mechanism. Neuroscience Letters. 2008;436(1):77–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baki L, Shioi J, Wen P, et al. PS1 activates PI3K thus inhibiting GSK-3 activity and tau overphosphorylation: effects of FAD mutations. The EMBO Journal. 2004;23(13):2586–2596. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nizzari M, Venezia V, Repetto E, et al. Amyloid precursor protein and presenilin1 interact with the adaptor GRB2 and modulate ERK1,2 signaling. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(18):13833–13844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610146200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen Y, Huang X, Zhang Y, et al. Alzheimer's β-secretase (BACE1) regulates the cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway independently of β-amyloid. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(33):11390–11395. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0757-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jonsson T, Atwal JK, Steinberg S, et al. A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer's disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature. 2012;487(7409):96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature11283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, et al. Association of missense and 5′-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature. 1998;393(6686):702–705. doi: 10.1038/31508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goedert M, Crowther RA, Spillantini MG. Tau mutations cause frontotemporal dementias. Neuron. 1998;21(5):955–958. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80615-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Spillantini MG, Murrell JR, Goedert M, Farlow MR, Klug A, Ghetti B. Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(13):7737–7741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Roberson ED, Scearce-Levie K, Palop JJ, et al. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid β-induced deficits in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316(5825):750–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1141736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Santacruz K, Lewis J, Spires T, et al. Tau suppression in a neurodegenerative mouse model improves memory function. Science. 2005;309(5733):476–481. doi: 10.1126/science.1113694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ittner LM, Ke YD, Delerue F, et al. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-β toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Cell. 2010;142(3):387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mondragón-Rodríguez S, Trillaud-Doppia E, Dudilot A, et al. Interaction of endogenous tau protein with synaptic proteins is regulated by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-dependent tau phosphorylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287(38):32040–32053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.401240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Um JW, Nygaard HB, Heiss JK, et al. Alzheimer amyloid-β oligomer bound to postsynaptic prion protein activates Fyn to impair neurons. Nature Neuroscience. 2012;15(9):1227–1235. doi: 10.1038/nn.3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Amadoro G, Ciotti MT, Costanzi M, Cestari V, Calissano P, Canu N. NMDA receptor mediates tau-induced neurotoxicity by calpain and ERK/MAPK activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(8):2892–2897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511065103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Um JW, Kaufman AC, Kostylev M, et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 is a coreceptor for Alzheimer aβ oligomer bound to cellular prion protein. Neuron. 2013;79(5):887–902. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Leugers CJ, Lee G. Tau potentiates nerve growth factor-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling and neurite initiation without a requirement for microtubule binding. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(25):19125–19134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.105387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sharma VM, Litersky JM, Bhaskar K, Lee G. Tau impacts on growth-factor-stimulated actin remodeling. Journal of Cell Science. 2007;120(5):748–757. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee G, Todd Newman S, Gard DL, Band H, Panchamoorthy G. Tau interacts with src-family non-receptor tyrosine kinases. Journal of Cell Science. 1998;111(21):3167–3177. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.21.3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hwang SC, Jhon D, Bae YS, Kim JH, Rhee SG. Activation of phospholipase C-γ by the concerted action of tau proteins and arachidonic acid. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(31):18342–18349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yoshizaki C, Tsukane M, Yamauchi T. Overexpression of tau leads to the stimulation of neurite outgrowth, the activation of caspase 3 activity, and accumulation and phosphorylation of tau in neuroblastoma cells on cAMP treatment. Neuroscience Research. 2004;49(4):363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Biernat J, Wu Y, Timm T, et al. Protein kinase MARK/PAR-1 is required for neurite outgrowth and establishment of neuronal polarity. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2002;13(11):4013–4028. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-03-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Seward ME, Swanson E, Norambuena A, et al. Amyloid-β signals through tau to drive ectopic neuronal cell cycle re-entry in alzheimer's disease. Journal of Cell Science. 2013;126(5):1278–1286. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1125880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hoerndli FJ, Pelech S, Papassotiropoulos A, Götz J. Aβ treatment and P301L tau expression in an Alzheimer's disease tissue culture model act synergistically to promote aberrant cell cycle re-entry. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;26(1):60–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bhaskar K, Yen S, Lee G. Disease-related modifications in tau affect the interaction between Fyn and tau. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(42):35119–35125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reynolds CH, Garwood CJ, Wray S, et al. Phosphorylation regulates tau interactions with Src homology 3 domains of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, phospholipase Cγ1, Grb2, and Src family kinases. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(26):18177–18186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brandt R, Hundelt M, Shahani N. Tau alteration and neuronal degeneration in tauopathies: mechanisms and models. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2005;1739(2-3):331–354. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Goedert M, Jakes R, Crowther RA. Effects of frontotemporal dementia FTDP-17 mutations on heparin-induced assembly of tau filaments. FEBS Letters. 1999;450(3):306–311. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Deture M, Ko L, Yen S, et al. Missense tau mutations identified in FTDP-17 have a small effect on tau-microtubule interactions. Brain Research. 2000;853(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nacharaju P, Lewis J, Easson C, et al. Accelerated filament formation from tau protein with specific FTDP-17 missense mutations. FEBS Letters. 1999;447(2-3):195–199. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Goedert M, Spillantini MG. Tau mutations in frontotemporal dementia FTDP-17 and their relevance for Alzheimer's disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—Molecular Basis of Disease. 2000;1502(1):110–121. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mairet-Coello G, Courchet J, Pieraut S, Courchet V, Maximov A, Polleux F. The CAMKK2-AMPK kinase pathway mediates the synaptotoxic effects of Abeta oligomers through Tau phosphorylation. Neuron. 2013;78(1):94–108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jin M, Shepardson N, Yang T, Chen G, Walsh D, Selkoe DJ. Soluble amyloid β-protein dimers isolated from Alzheimer cortex directly induce Tau hyperphosphorylation and neuritic degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(14):5819–5824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017033108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zempel H, Thies E, Mandelkow E. Aβ oligomers cause localized Ca2+ elevation, missorting of endogenous Tau into dendrites, Tau phosphorylation, and destruction of microtubules and spines. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(36):11938–11950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2357-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rapoport M, Dawson HN, Binder LI, Vitek MP, Ferreira A. Tau is essential to β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(9):6364–6369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092136199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hanger DP, Anderton BH, Noble W. Tau phosphorylation: the therapeutic challenge for neurodegenerative disease. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2009;15(3):112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lee G, Leugers CJ. Tau and tauopathies. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. 2012;107:263–293. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385883-2.00004-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Biernat J, Gustke N, Drewes G, Mandelkow E. Phosphorylation of Ser262 strongly reduces binding of tau to microtubules: Distinction between PHF-like immunoreactivity and microtubule binding. Neuron. 1993;11(1):153–163. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90279-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li X, Kumar Y, Zempel H, Mandelkow E, Biernat J, Mandelkow E. Novel diffusion barrier for axonal retention of Tau in neurons and its failure in neurodegeneration. EMBO Journal. 2011;30(23):4825–4837. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Iijima K, Gatt A, Iijima-Ando K. Tau Ser262 phosphorylation is critical for Aβ42-induced tau toxicity in a transgenic Drosophila model of Alzheimer's disease. Human Molecular Genetics. 2010;19(15):2947–2957. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yu W, Polepalli J, Wagh D, Rajadas J, Malenka R, Lu B. A critical role for the PAR-1/MARK-tau axis in mediating the toxic effects of Aβ on synapses and dendritic spines. Human Molecular Genetics. 2012;21(6):1384–1390. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bertrand J, Plouffe V, Sénéchal P, Leclerc N. The pattern of human tau phosphorylation is the result of priming and feedback events in primary hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 2010;168(2):323–334. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Twiss JL, Chang JH, Schanen NC. Pathophysiological mechanisms for actions of the neurotrophins. Brain Pathology. 2006;16(4):320–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2006.00039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bibel M, Barde Y. Neurotrophins: Key regulators of cell fate and cell shape in the vertebrate nervous system. Genes and Development. 2000;14(23):2919–2937. doi: 10.1101/gad.841400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kole AJ, Annis RP, Deshmukh M. Mature neurons: equipped for survival. Cell Death & Disease. 2013;4, article e689 doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Colucci-D'Amato L, Perrone-Capano C, di Porzio U. Chronic activation of ERK and neurodegenerative diseases. BioEssays. 2003;25(11):1085–1095. doi: 10.1002/bies.10355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhu X, Lee H, Raina AK, Perry G, Smith MA. The role of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroSignals. 2002;11(5):270–281. doi: 10.1159/000067426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Thomas GM, Huganir RL. MAPK cascade signalling and synaptic plasticity. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2004;5(3):173–183. doi: 10.1038/nrn1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Grewal SS, York RD, Stork PJ. Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase signalling in neurons. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1999;9(5):544–553. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(99)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wortzel I, Seger R. The ERK cascade: distinct functions within various subcellular organelles. Genes and Cancer. 2011;2(3):195–209. doi: 10.1177/1947601911407328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Marshall CJ. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: Transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell. 1995;80(2):179–185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Caunt CJ, Keyse SM. Dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatases (MKPs): shaping the outcome of MAP kinase signalling. FEBS Journal. 2013;280(2):489–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08716.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Stanciu M, Defranco DB. Prolonged nuclear retention of activated extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase promotes cell death generated by oxidative toxicity or proteasome inhibition in a neuronal cell line. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(6):4010–4017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104479200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Subramaniam S, Strelau J, Unsicker K. Growth differentiation factor-15 prevents low potassium-induced cell death of cerebellar granule neurons by differential regulation of Akt and ERK pathways. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(11):8904–8912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kulich SM, Chu CT. Sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation by 6-hydroxydopamine: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2001;77(4):1058–1066. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Stanciu M, Wang Y, Kentor R, et al. Persistent activation of ERK contributes to glutamate-induced oxidative toxicity in a neuronal cell line and primary cortical neuron cultures. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(16):12200–12206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.12200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jiang Q, Gu Z, Zhang G. Nuclear translocation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases in neuronal excitotoxicity. NeuroReport. 2001;12(11):2417–2421. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200108080-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gralle M, Ferreira ST. Structure and functions of the human amyloid precursor protein: the whole is more than the sum of its parts. Progress in Neurobiology. 2007;82(1):11–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Milward EA, Papadopoulos R, Fuller SJ, et al. The amyloid protein precursor of Alzheimer's disease is a mediator of the effects of nerve growth factor on neurite outgrowth. Neuron. 1992;9(1):129–137. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jin K, Galvan V, Xie L, et al. Enhanced neurogenesis in Alzheimer's disease transgenic (PDGF-APP Sw,Ind) mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(36):13363–13367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403678101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yu Y, He J, Zhang Y, et al. Increased hippocampal neurogenesis in the progressive stage of Alzheimer's disease phenotype in an APP/PS1 double transgenic mouse model. Hippocampus. 2009;19(12):1247–1253. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Porayette P, Gallego MJ, Kaltcheva MM, Bowen RL, Meethal SV, Atwood CS. Differential processing of amyloid-β precursor protein directs human embryonic stem cell proliferation and differentiation into neuronal precursor cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(35):23806–23817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.López-Toledano MA, Shelanski ML. Neurogenic effect of β-amyloid peptide in the development of neural stem cells. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(23):5439–5444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0974-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Heo C, Chang K, Choi HS, et al. Effects of the monomeric, oligomeric, and fibrillar Aβ42 peptides on the proliferation and differentiation of adult neural stem cells from subventricular zone. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2007;102(2):493–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Calafiore M, Battaglia G, Zappalà A, et al. Progenitor cells from the adult mouse brain acquire a neuronal phenotype in response to β-amyloid. Neurobiology of Aging. 2006;27(4):606–613. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Yankner BA, Duffy LK, Kirschner DA. Neurotrophic and neurotoxic effects of amyloid β protein: reversal by tachykinin neuropeptides. Science. 1990;250(4978):279–282. doi: 10.1126/science.2218531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Mazanetz MP, Fischer PM. Untangling tau hyperphosphorylation in drug design for neurodegenerative diseases. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2007;6(6):464–479. doi: 10.1038/nrd2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zheng Y, Li B, Kanungo J, et al. Cdk5 modulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling regulates neuronal survival. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2007;18(2):404–413. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Tanzi RE. The genetics of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2012;2(10) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Wolfe MS. When loss is gain: reduced presenilin proteolytic function leads to increased Aβ42/Aβ40. Talking Point on the role of presenilin mutations in Alzheimer disease. EMBO Reports. 2007;8(2):136–140. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Park MH, Choi DY, Jin HW, et al. Mutant presenilin 2 increases β-secretase activity through reactive oxygen species-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. 2012;71(2):130–139. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182432967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kang DE, Yoon IS, Repetto E, et al. Presenilins mediate phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT and ERK activation via select signaling receptors: selectivity of PS2 in platelet-derived growth factor signaling. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(36):31537–31547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500833200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Korwek KM, Trotter JH, Ladu MJ, Sullivan PM, Weeber EJ. Apoe isoform-dependent changes in hippocampal synaptic function. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2009;4(1, article 21) doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Bu G. Apolipoprotein e and its receptors in Alzheimer's disease: حathways, pathogenesis and therapy. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10(5):333–344. doi: 10.1038/nrn2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Lleó A, Waldron E, Von Arnim CAF, et al. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) interacts with presenilin 1 and is a competitive substrate of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) for γ-secretase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(29):27303–27309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413969200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.DeMattos RB, Cirrito JR, Parsadanian M, et al. ApoE and clusterin cooperatively suppress Abeta levels and deposition: evidence that ApoE regulates extracellular Abeta metabolism in vivo. Neuron. 2004;41(2):193–202. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00850-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Harris FM, Brecht WJ, Xu Q, Mahley RW, Huang Y. Increased tau phosphorylation in apolipoprotein E4 transgenic mice is associated with activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase: modulation by zinc. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(43):44795–44801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408127200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Willnow TE, Carlo A, Rohe M, Schmidt V. SORLA/SORL1, a neuronal sorting receptor implicated in Alzheimer's disease. Reviews in the Neurosciences. 2010;21(4):315–329. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2010.21.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Glerup S, Lume M, Olsen D, et al. SorLA controls neurotrophic activity by sorting of GDNF and its receptors GFRα1 and RET. Cell Reports. 2013;3(1):186–199. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Nie D, di Nardo A, Han JM, et al. Tsc2-Rheb signaling regulates EphA-mediated axon guidance. Nature Neuroscience. 2010;13(2):163–172. doi: 10.1038/nn.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Elowe S, Holland SJ, Kulkarni S, Pawson T. Downregulation of the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by the EphB2 receptor tyrosine kinase is required for ephrin-induced neurite retraction. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2001;21(21):7429–7441. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7429-7441.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Huber TB, Hartleben B, Kim J, et al. Nephrin and CD2AP associate with phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase and stimulate AKT-dependent signaling. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2003;23(14):4917–4928. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.4917-4928.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Killick R, Ribe EM, Al-Shawi R, et al. Clusterin regulates β-amyloid toxicity via Dickkopf-1-driven induction of the wnt-PCP-JNK pathway. Molecular Psychiatry. 2012;19(1):88–98. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Gil SY, Youn B, Byun K, et al. Clusterin and LRP2 are critical components of the hypothalamic feeding regulatory pathway. Nature Communications. 2013;4, article 1862 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Narayan P, Orte A, Clarke RW, et al. The extracellular chaperone clusterin sequesters oligomeric forms of the amyloid-β 1-40 peptide. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2012;19(1):79–83. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Wang D, Fu Q, Zhou Y, et al. Β2 adrenergic receptor, protein kinase a (PKA) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathways mediate tau pathology in alzheimer disease models. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288(15):10298–10307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.415141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Yu JT, Tan L, Ou J, et al. Polymorphisms at the β2-adrenergic receptor gene influence Alzheimer’s disease susceptibility. Brain Research. 2008;1210:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Griciuc A, Serrano-Pozo A, Parrado AR, et al. Alzheimer's disease risk gene cd33 inhibits microglial uptake of amyloid beta. Neuron. 2013;78(4):631–643. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]