Abstract

The hip joint is one of the most surgically exposed joints in the body. The indications for surgical exposure are numerous ranging from simple procedures such as arthrotomy for joint drainage in infection to complex procedures like revised total hip replacement. Tissue dissections based on sound knowledge of anatomic orientations is essential for best surgical outcomes. In this review, the anatomical basis for the various approaches to the hip is presented. Systematic review of the literature was done by using PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, OVID, and Google databases. Out of the initial 150 articles selected from the the review and selection criteria, only 37 that suited the study were eventually used. Selected articles included case reports, clinical trials, review and research reports. Each of these approaches has various modifications that seek to correct certain difficulties or problems encountered with previous descriptions. An ideal approach for a procedure should be safe and provide satisfactory exposure of the joint. It should avoid bone and soft tissue damage as well as avoid unnecessary devascularization. Among the factors that determine the choice of surgical approach to the hip are the indication for the procedure; the influence of previous surgical incisions as well as the personal preferences and training of the operating surgeon.

Keywords: Anatomy, Arthroplasty, Hip joint, Surgical approach

Introduction

Operations of the hip joint are among the most common procedures in orthopedics.[1] Surgical exposure of the hip joint is required for tumor surgery, treatment of infection in the hip joint, treatment of hip fractures, hemi-arthroplasty as well as primary and revised total hip replacement.[2,3,4,5,6,7] The principles of surgical exposure include a thorough knowledge of anatomy of the region and its variations,[8,9,10,11] proper patient positioning and adequate incisions. Dissections through natural cleavage planes help to minimize bleeding and disruption of important functional structures.

Classification of surgical approaches to the hip joint into well-defined groupings is usually difficult. However, a general classification on the basis of the approach to the capsule of the hip joint into anterior, anterolateral, lateral, posterior and medial approaches[1,9] has been used. These surgical approaches should provide sufficient anatomic orientation and exposure to allow surgical procedures to be performed safely.

The minimally-invasive two-incision approach to the hip joint is also described.

Skin incisions for various surgical approaches to the hip joint are created to maximize surgical exposure and whenever possible old scars should be incorporated. Hip surgery usually requires careful pre-operative planning and the choice of surgical approach is one of the most important components of this plan.[12] An ideal approach should be safe, simple and anatomic, thus preventing unnecessary devascularization. It should provide satisfactory exposure to the joint and not result in unnecessary bone and soft-tissues damage.[9,12]

There are certain factors that influence the choice of surgical approach to the hip joint. Among these factors are the indication for the procedure; the type of implant to be used; the presence of acetabular or femoral bone loss; the training and personal preferences of the surgeon and the influence of previous surgical incisions.[1,8,9,12] Of these factors, the influence of the surgeon's training and preferences in the choice of surgical approach to the hip appears to be overwhelming. Many surgeons usually use a preferred approach to the hip for routine hip operations. This approach will be the one to which the surgeon was most widely exposed during residency or fellowship training;[12] with little consideration given to the anatomical basis for the approach.[1,9,10,11] It is important to stress that no one surgical approach is the most appropriate for all hip exposures. The need to choose an approach that provides the best exposure for a specific procedure and causes minimum anatomic disruptions cannot be over-emphasized. Therefore, the surgeon must be familiar with the anatomy of the various approaches if the clinical result is to be optimized.

The aim of this study is to review the anatomical basis for the various approaches to the hip and to highlight the need for surgeons to be conversant with the full gamut of surgical approaches to the hip, so that the most appropriate one can be used for each procedure. All the approaches have their advantages and also disadvantages and it is very imperative that surgeons must have precise details of this information prior to any surgery.

Methods of Literature Search

Systematic review of the literature was done by using PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, OVID, and Google databases to look for peer reviewed papers using the key words “Anatomy, Arthroplasty, Hip joint, Surgical approach”. Only studies in English were included. Search duration covered all publication prior to the time of the search (2012). Out of the initial 150 articles selected from the the review and selection criteria, only 37 that suited the study were eventually used. Selected articles included case reports, clinical trials, review and research reports. All articles on surgery of the hip joint that had focus outside the contest of the review were excluded.

Anatomy and Surgical Approaches

Bony landmarks

Identification of bony landmarks surrounding the hip joint may be difficult because of the large surrounding muscle envelope. These landmarks are the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), posterior superior iliac spine, the greater trochanter, the pubic tubercle and pubic symphysis. These landmarks are important in creating incisions for surgical approaches to the hip.

Muscles

The hip joint is covered by a large muscle envelope with 21 muscles crossing the joint. In hip surgery, certain muscles have major surgical significance. The tensor fascia latae and gluteus maximus have been described as the doorway to the hip joint.[13] These muscles together with the iliotibial band form the outer layer of the muscular envelope of the gluteal region. One of these muscles or the iliotibial band must be split in order to gain access to the deeper muscles of the gluteal region. The gluteus medius is another muscle of surgical importance. It is the major abductor of the hip joint and together with the gluteus minimus help to stabilize the hip joint in the swing phase of the gait cycle.

The lateral approaches are designed to either avoid detachment of the gluteus medius or displace the abductors by mechanisms that facilitate reattachment.[9,14,15] The gluteus minimus plays a much less role. It is a weak abductor of the hip but also provides some flexion and internal rotation of the hip. It contributes to the stability of the hip joint in the swing phase of the gait cycle. Accurate reattachment of its tendon must not be overlooked during hip surgery.

Of the short external rotators of the hip, the piriformis is of great surgical importance,[13] it provides the key to the understanding the neurovascular anatomy of the gluteal region. Therefore, the superior gluteal vessels and nerve enter the gluteal region above the pelvis pass below it. The iliopsoas tendon inserts into the lesser trochanter posteromedially. Its release is needed to facilitate exposure of the hip in the anterior and medial approaches.

Vessels

The groin and gluteal regions have an extensive arterial blood supply. A sound knowledge of the anatomy of these vessels is important not only to minimize intra-operative bleeding, but also to prevent the effect of vascular complications on the outcome of the procedure.[9,16] The superior gluteal artery is most at risk at its division at the upper border of piriformis. This “danger spot” is located three finger breaths anterior to the posterior superior iliac spine. The deep branch is also at risk as it traverses with the corresponding nerve about 4-6 cm above the acetabular rim.[9] The lateral femoral circumflex artery, a branch of the profunda femoris artery is encountered and requires ligation during Smith-Petersen approach.

Although the incidence of major vascular injury during hip surgery is about 0.2-0.3%,[17] they can pose a threat to the survival of the limb and the patient. A good knowledge of the anatomy and mechanisms of vascular injury is important to avoid vascular complications.

Nerves

The nerves of surgical importance in hip operations include lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, the femoral nerve, the superior and inferior gluteal nerves, the sciatic and obturator nerve. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is the most encountered during anterior approaches. Sciatic nerve is an important posterior relation of the hip. The incidence of the sciatic nerve injury associated with posterior approaches to the hip is estimated at 0.7-1.0%.[18] The various anatomical arrangements of the sciatic nerve in relationship to the piriformis must be known to the surgeon. The nerve must be identified and protected.[19] The superior gluteal nerve has a significant potential for injury particularly in gluteus-splitting approaches. The “safe area” when splitting the abductors (gluteus medius) is 5 cm from the tip of the greater trochanter.[9,17,20] Other authors report that the course of the superior gluteal nerve runs as close as 3 cm from the tip of the greater trochanter.[21]

Joint capsule and ligament

The hip capsule is a strong fibrous tissue that extends down to the intertrochanteric line anteriorly; however, posteriorly it is deficient. The capsule is reinforced anteriorly by the iliofemoral ligament of Bigelow; inferiorly by the pubofemoral condensation and posteriorly by a thin ischiofemoral ligament. The ligamentum fovea extends from the fovea of the femoral head to the acetabular fovea.

Anterior Approaches

The anterior approach is also known as anterior iliofemoral or Smith-Petersen approach.[22] It affords good exposure of the acetabulum and avoids disruption of the abductor mechanism. The indications for this approach include open reduction of congenital dislocation of the hip, synovial biopsy, hemiarthroplasty, pelvic osteotomies, total hip replacement and joint drainage and irrigation for infection. The skin incision is made from the middle of the iliac crest and carried anteriorly to the ASIS. From there the incision is carried distally and slightly laterally for 8-10 cm.

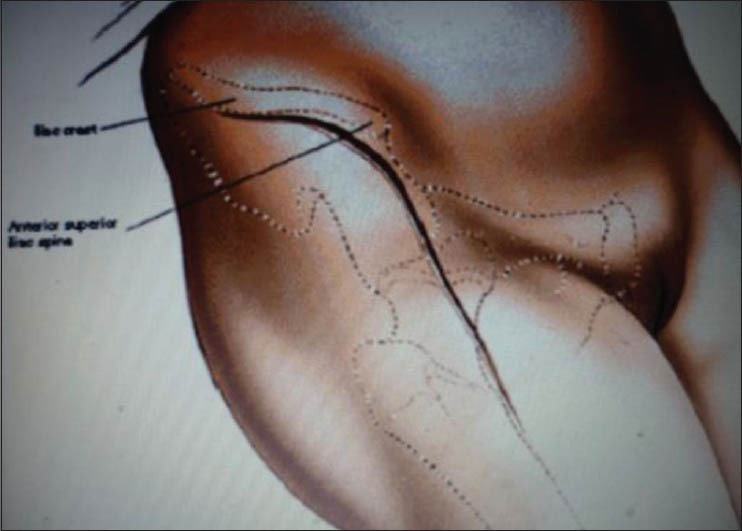

The mini-incision anterior approach starts at a point 2 cm posterior and 2 cm caudal to the ASIS and extends 6-8 cm along an imaginary line joining the ASIS to the head of fibula. The superficial and deep fasciae are divided and the attachments of the gluteus medius and tensor fasciae latae from the iliac crest are freed. Identify the interval between the tensor fasciae latae and the Sartorius by blunt dissection approximately 2-3 inches below the ASIS [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Anterior approach

Identify and protect the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, which pierces the deep fascia close to the intramuscular interval.

The Sartorius is retracted upward and medially and the tensor fasciae latae is retracted downward and laterally. The ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery crosses this interval. It must be identified, clamped and ligated.

The deep dissection is through the interval between the rectus femoris (femoral nerve) and the gluteus medius (superior gluteal nerve). The rectus femoris is detached from its origins and retracted medially while the gluteus medius is retracted laterally. The capsule of the hip joint is now exposed.

Somerville[23] described an anterior approach using a transverse “bikini” incision for irreducible congenital dislocation of the hip in a young child. This approach allows sufficient exposure of the ilium and acetabulum. Schaubel[24] modified the Smith-Petersen approach. He found reattachment of fascia lata to the fascia on the iliac crest difficult, so he performed an osteotomy of the iliac crest between attachments of the external oblique muscle medially and the fascia lata laterally. The tensor fasciae latae, gluteus medius and gluteus minimums attachments were subperiosteally dissected to expose the hip joint capsule. At closure, the iliac osteotomy is reattached with non-absorbable sutures.

Merits

Both the superficial and deep dissections are through internervous planes

It provides good exposure of the anterior column and medial wall of acetabulum, thus very commonly used in surgery of congenital hip dislocation and acetabular dysplasia

It avoids disruption of the abductor mechanisms, thus preventing post-operative limping

There is low risk of dislocation.

Demerits

It provides unsatisfactory access to the posterior column of the acetabulum and femoral medullary canal

There is incongruency of the skin incision with the plane of intramuscular interval.

Anterolateral Approach

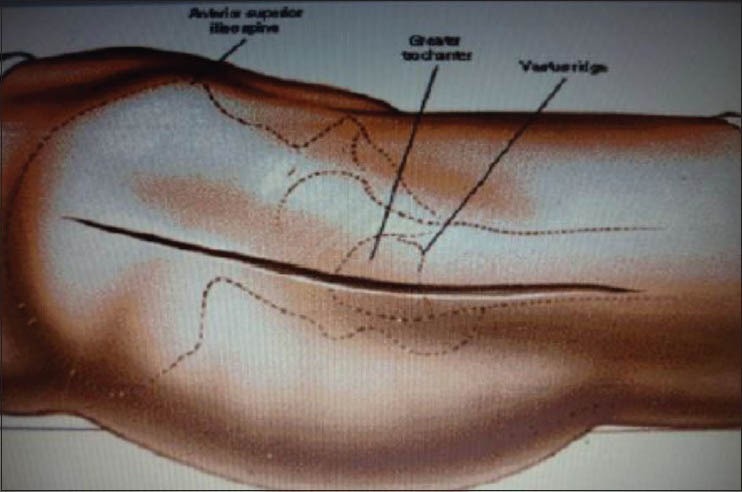

This approach combines an excellent exposure of the acetabulum with safety. It exploits the intramuscular plane between the tensor fasciae latae and gluteus medius.[7,25] Watson-Jones[26] popularized this approach, but it has been modified by Charnley,[27] Harris[28] and Muller.[29] It also involves partial or complete detachment of some or all of the abductor mechanism so that the hip can be adducted and the acetabulum can be more fully exposed. The indications for this approach include: Total hip replacement; hemiarthroplasty; open reduction and internal fixation of the femoral neck fractures, synovial biopsy of the hip and biopsy of the femoral neck. The skin incision starts at a point 2-3 cm posterior to the ASIS and is directed toward the mid portion of the greater trochanter. It then continues 10-15 cm along the axis of the femur [Figure 2]. Incise the fascia lata in line with the skin incision at the posterior margin of the greater trochanter.

Figure 2.

Antero-lateral approach

Extend this incision superiorly and anteriorly toward the ASIS and also distally and anteriorly to expose the underlying vastus lateralis.

Identify the interval between the gluteus medius and tensor fasciae latae by blunt dissection. This is best done at a point mid-way between the ASIS and greater trochanter to avoid injury to the inferior branch of the superior gluteal nerve that supplies the tensor fasciae latae.

The gluteus medius and the underlying gluteus minimus are retracted proximally and laterally to expose the superior aspect of the joint capsule covering the femoral neck. The ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery that passes deep to tensor fasciae latae and gluteus medius requires ligation as the gap between these muscles is opened up. The superior retinacular vessels which are a major source of blood supply to the head of the femur are however not interrupted; therefore, the chances of avascular necrosis of the femoral head are low.

Merits

It retains the advantages of the anterior approach.

It provides good exposure of the femoral neck.

There is low risk of avacular necrosis of the femoral head.

Demerits

There is limited exposure of the acetabulum.

There is risk of damage to superior gluteal nerve.

Lateral Approaches

The lateral approaches can be subdivided into direct lateral and trans-trochanteric techniques. Both methods displace a portion of or the entire abductor mechanisms to facilitate exposure.[9]

Direct lateral approaches are based on the observation that the gluteus medius and vastus lateralis can be regarded as being in direct functional continuity through the thick tendinous periosteum covering the greater trochanter.[14,30]

It was first introduced by McFarland and Osborne[14] in 1954, and was modified by Hardinge[15] in 1982.

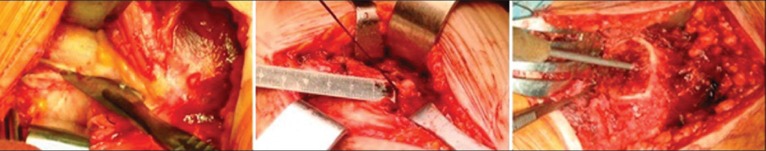

McFarland and Osborne technique

A mid-lateral skin incision centered over the greater trochanter is made [Figure 3]. Expose the fascia lata and iliotibial band and divide them in the line of skin incision. The gluteus maximus is retracted posteriorly and the tensor fasciae latae anteriorly. The gluteus medius is now identified and separated from surrounding muscles by blunt dissection. Incise the posterior border down to the bone obliquely downwards across the greater trochanter and along the vastus lateralis. Elevate the tendon of gluteus medius, the periosteum and origin of vastus lateralis in one piece and retract anteriorly to expose the gluteus minimus. Divide the tendon of gluteus minimus and retract proximally to expose the joint capsule.

Figure 3.

McFarland and osbrne technique

In 1982, Hardinge modified this technique (trans-gluteal approach) by incising the tendon of gluteus medius obliquely across the greater trochanter leaving the posterior half still attached to the trochanter [Figure 4]. He observed that the post-operative abductor weakness was less and the rehabilitation of patients was faster. It is important to note that the abductor split must never be more than 5 cm above the tip of the greater trochanter to avoid injury to superior gluteal vessels and nerve.

Figure 4.

Harris trochanteric approach

Merits

It provides adequate exposure of the acetabulum

It avoids the problems of trochanteric reattachment.

Demerits

There is post-operative abductor weakness (better in Hardinge technique) with associated limping

There is a potential for damage to superior gluteal vessel and nerve.

Trans-trochanteric technique

In trans-trochanteric technique, the attachment of gluteus medius and vastus lateralis at the greater trochanter is osteotomized so that the muscles and a chip of bone are lifted in one piece.

This technique provides excellent acetabular visualization and orientation and permits trochanteric transfer if desired. It was introduced by Charnley and Ferreiraade[31] for improving abductor lever arm by a distal and lateral transfer of the greater trochanter, which restored abductor power after total hip replacement.

Subsequently, the role of trochanteric osteotomy in facilitating surgical exposure became a central theme in hip surgery.[9]

Harris technique[32] is the most popular transtrochanteric lateral approach which is recommended for extensive exposure of the hip. Testa and Mazur[33] reported that the incidence of significant or disabling heterotopic ossification is increased by this technique.

Harris technique

A U-shaped skin incision is made with its base at the posterior border of the greater trochanter. It is begun 5 cm posterior and slightly proximal to ASIS. The iliotibial band is divided in line of skin incision. Osteotomize the greater trochanter and reflect the tendon of gluteus medius with the chip of bone proximally. The origin of vastus lateralis is reflected distally [Figure 5]. The short rotators of the hip are divided at the femoral insertion to expose the joint capsule.

Figure 5.

Harris trochanteric approach

Glassman et al.[34] modified the transtrochanteric technique, by preserving the continuity of the gluteus medius and vastus lateralis by performing the osteotomy in the sagittal plane. The intact musculo osseous sleeve is displaced anteriorly.

In the McLauchlan[35] modification, the gluteus medius and vastus lateralis muscles are split in line of their fibers and the greater trochanter is cut in the form of two rectangular slices. The gluteus medius is attached proximally and the vastus lateralis distally on each of these bone chips. One is retracted anteriorly and the other posteriorly to expose the hip joint.

Merits

There is extensive exposure of the acetabulum and proximal femur.

Demerits

There is abductor weakness

Trochanteric non-union may occur

Trochanteric bursitis and heterotopic ossification may occur.

Posterior Approach

The posterior approach is probably the most commonly used approach for total hip replacement.[1,9,36] It was first described by Langenbeck and modified by Kocher[37] in 1907. It is commonly used in total hip replacement because it does not disrupt the abductor mechanism thereby making rehabilitation rapid. However, it is less popular for open reduction and internal fixation of fracture neck of femur. This is because the superior retinacular vessels and the ascending branch of the medial circumflex femoral artery are in jeopardy with increased chances of avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

There are many variations of the posterior approach and these vary primarily in the placement of the skin incision and the level gluteus maximus splitting.[38,39,40,41] Moore's description in 1957[42] is the most popular posterior approach. Indications include: Hemiarthroplasty; total hip replacement; open reduction and internal fixation of posterior acetabular fractures; open reduction of posterior hip dislocations;[43] dependent drainage of hip sepsis and pedicle bone grafting.

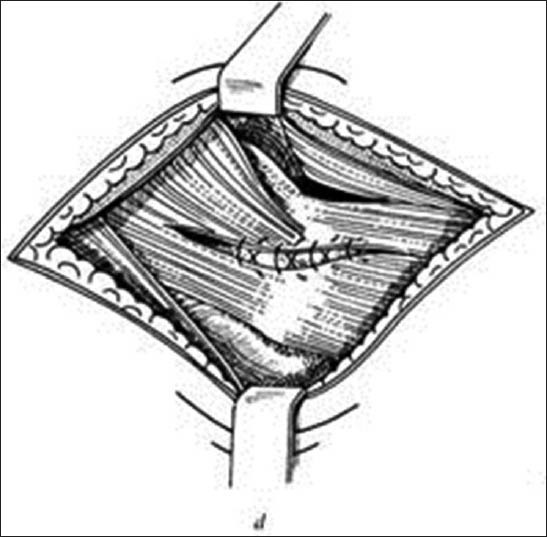

Moore technique

It is also known as “Southern” approach. The skin incision is 10 cm distal to the posterior superior iliac spine and extends laterally and distally to the greater trochanter. It is then carried distally 15 cm along the femoral shaft. The fascia lata and gluteal fascia are divided in line with skin incision [Figure 6]. The fibers of the gluteus maximus are separated bluntly in line with skin incision. This ensures that branches of the superior gluteal vessels and nerve in the proximal half of the muscle and those of the inferior gluteal vessels and nerve in the distal half of the muscle are preserved. The sciatic nerve is then identified and protected.

Figure 6.

Moore's posterior approach

The short external rotators are bluntly dissected and detached near their femoral insertion. The muscles are retracted medially to protect the sciatic nerve and the capsule is now exposed.

In Marcy and Fletcher[40] technique, the interval between the gluteus maximus and gluteus medius is developed. It is a more natural separation and dissection is through an internervous plane; however, the exposure is not optimal.

Merits

It provides safe and easy access to the hip

There is no disruption of the abductor mechanism

Post-operative rehabilitation is rapid.

Demerits

Higher incidence of post-operative dislocation

Risk of injury to the sciatic nerve is significant

Higher incidence of post-operative wound infection.

Medial Approach

This approach was developed by Ludloff[44] in 1908 for surgery of congenital hip dislocation in early childhood.

Ferguson's modification[45] in 1973 popularized this approach. In Ludloff technique, the plane of dissection is between the adductor longus and pectineus (anteromedial). Therefore, in Ferguson's techniques, the superficial muscle interval is between the gracilis and adductor longus and the deep interval between the adductor brevis and adductor Magnus. Indications include: Open reduction of congenital dislocation of the hip; biopsy of tumors of the medial aspect of the proximal femur; release of iliopsoas tendon in the treatment of hip contractures and obturator neurectomy.

Ferguson's technique

In the supine position with hip flexed, abducted and externally rotated, the lesser trochanter and medial joint capsule are closer to the skin surface. A longitudinal skin incision, 3 cm distal to public tubercle is made in line with adductor longus. Develop the plane between the adductor longus and gracilis by blunt dissection [Figure 7]. The deep dissection is in the interval between the adductor brevis and adductor magnus. Retract the adductor longus and brevis anterior and the gracilis and adductor magnus posteriorly.

Figure 7.

Ferguson's medial approach

The posterior branch of the obturator nerve is visible on the belly of the adductor magnus. Identify the anterior branch of the obturator nerve lying on the anterior surface of the adductor brevis. If the approach is not for obturator neurectomy, avoid transecting the nerves. Isolate the lesser trochanter in the base of the wound by blunt dissection and transect the iliopsoas tendon. This allows exposure of the medial hip joint capsule.

Merits

Little dissection is needed

Operation time is short

Blood loss is low.

Demerits

Technically difficult especially in adults

It has limited use only in infants

Risk of damage to medial circumflex femoral artery with increased risk of avascular necrosis of the femoral head (Ludloff technique).

Two-incision Approach

The Zimmer minimally invasive solution two-incision approach to the hip joint was introduced in 2001. The indication was majorly for primary total hip replacement. The aim is to facilitate implantation of the femoral and acetabular components of the hip prosthesis through two small incisions with fewer traumas to soft-tissue than other conventional approaches. A 5 cm anterior skin incision placed over the femoral neck is used to access the acetabulum. A 3 cm posterior incision placed in line with femoral canal is used for femoral preparation. The merits include: Smaller incision (scar); less blood loss; less post-operative pain; quicker rehabilitation and shorter hospital stay. Although the demerits are: Extended learning curve for surgeons; malpositioning of prosthesis; superficial nerve damage and proximal femoral fractures.

Conclusion

Hip operations are common procedures in orthopedic practice. There is a gamut of surgical approaches to the hip and no single approach is suitable for all hip procedures. The surgeon who performs these procedures should be conversant with a range of approaches. The choice of a surgical exposure for any given hip procedure should be based on the indication, its merits and demerits as well as a good knowledge of the anatomic basis of the approach and not merely the surgeon's personal preference.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Hoppenfeld S, DeBoer P, Buckley R. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. Surgical Exposures in Orthopaedics: The Anatomic Approach; pp. 403–61. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eijer H, Leunig M, Mahomed M, Ganz R. Cross-table lateral radiographs for screening of anterior femoral head-neck offset in patients with femoro-acetabular impingement. Hip Int. 2001;11:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan RJ, Maor D, Hofmann M, Haebich S. A comparison of a less invasive piriformis-sparing approach versus the standard posterior approach to the hip: A randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:43–50. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B1.27001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Browne JA, Pagnano MW. Surgical technique: A simple soft-tissue-only repair of the capsule and external rotators in posterior-approach THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:511–5. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2113-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li M, Luettringhaus T, Walker KR, Cole PA. Operative treatment of femoral neck osteochondroma through a digastric approach in a pediatric patient: A case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2012;21:230–4. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0b013e3283524bc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Man FH, Sendi P, Zimmerli W, Maurer TB, Ochsner PE, Ilchmann T. Infectiological, functional, and radiographic outcome after revision for prosthetic hip infection according to a strict algorithm. Acta Orthop. 2011;82:27–34. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.548025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sköldenberg O, Ekman A, Salemyr M, Bodén H. Reduced dislocation rate after hip arthroplasty for femoral neck fractures when changing from posterolateral to anterolateral approach. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:583–7. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.519170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harty M, Joyce JJ. Surgical approaches to the hip and femur. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1963;45A:175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen AD. Anatomy and surgical approaches. In: Morrey BF, editor. Reconstructive Surgery of the Joints. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996. pp. 883–909. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlisle JC, Zebala LP, Shia DS, Hunt D, Morgan PM, Prather H, et al. Reliability of various observers in determining common radiographic parameters of adult hip structural anatomy. Iowa Orthop J. 2011;31:52–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kijowski R, Gold GE. Routine 3D magnetic resonance imaging of joints. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;33:758–71. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masterson EL, Masri BA, Duncan CP. Surgical approaches in revision hip replacement. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6:84–92. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199803000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tronzo RG. Surgical approaches to the hip. In: Tronzo RD, editor. Surgery of the Hip Joint. 2nd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1984. p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McFarland B, Osborne G. Approach to the hip: A suggested improvement on Kocher's method. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1954;36B:364. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardinge K. The direct lateral approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64:17–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.64B1.7068713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beaule PE. Vascularity of the arthritic femoral head and its implications for hip resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94-B(Suppl VIII):41. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harkess JW. Arthroplasty of the hip. In: Canale ST, editor. Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics. 10th ed. St Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby; 2003. on CD-ROM. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmalzried TP, Amstutz HC, Dorey FJ. Nerve palsy associated with total hip replacement. Risk factors and prognosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:1074–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutter M, Hersche O, Leunig M, Guggi T, Dvorak J, Eggspuehler A. Use of multimodal intra-operative monitoring in averting nerve injury during complex hip surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:179–84. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B2.28019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs LG, Buxton RA. The course of the superior gluteal nerve in the lateral approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:1239–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nazarian S, Tisserand P, Brunet C, Müller ME. Anatomic basis of the transgluteal approach to the hip. Surg Radiol Anat. 1987;9:27–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02116851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith-Petersen MN. Approach to and exposure of the hip joint for mold arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1949;31A:40–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Somerville EW. Open reduction in congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1953;35-B:363–71. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.35B3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaubel HJ. Modification of the anterior iliofemoral approach to the hip. Int Surg. 1980;65:347–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Müller M, Tohtz S, Dewey M, Springer I, Perka C. Evidence of reduced muscle trauma through a minimally invasive anterolateral approach by means of MRI. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:3192–200. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1378-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson-Jones R. Fractures of the neck of the femur. Br J Surg. 1936;23:787. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charnley J. New York: Springer Verlag; 1979. Low Friction Arthroplasty of the Hip: Theory and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris WH. A new lateral approach to the hip joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1967;49:891–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller ME. Proceedings of the Second Scientific Meeting of the Hip Society. St Louis: C.V. Mosby; 1974. Total hip replacement without trochanteric osteotomy; pp. 231–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alecci V, Valente M, Crucil M, Minerva M, Pellegrino CM, Sabbadini DD. Comparison of primary total hip replacements performed with a direct anterior approach versus the standard lateral approach: Perioperative findings. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;12:123–9. doi: 10.1007/s10195-011-0144-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charnley J, Ferreiraade S. Transplantation of the greater trochanter in arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1964;46:191–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris WH. Extensive exposure of the hip joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;91:58–62. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197303000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Testa NN, Mazur KU. Heterotopic ossification after direct lateral approach and transtrochanteric approach to the hip. Orthop Rev. 1988;17:965–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glassman AH, Engh CA, Bobyn JD. A technique of extensile exposure for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1987;2:11–21. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(87)80026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLauchlan J. The stracathro approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984;66:30–1. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.66B1.6693474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macpherson GJ, Hank C, Schneider M, Trayner M, Elton R, Howie CR, et al. The posterior approach reduces the risk of thin cement mantles with a straight femoral stem design. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:292–5. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.487239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Carr A. Comparison of measures to assess outcomes in total hip replacement surgery. Qual Health Care. 1996;5:81–88. doi: 10.1136/qshc.5.2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibson A. Posterior exposure of the hip joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1950;32-B:183–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.32B2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horwitz T. The posterolateral approach in the surgical management of basilar neck, intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures of the femur; a report of its use in 36 acute fractures. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1952;95:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marcy GH, Fletcher RS. Modification of the posterolateral approach to the hip for insertion of femoral-head prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1954;36-A:142–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osborne RP. The approach to the hip joint: A critical review and suggested new route. Br J Surg. 1930;18:49. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore AT. The self-locking metal hip prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1957;39-A:811–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gaskill TR, Philippon MJ. Surgical hip dislocation for femoroacetabular impingement. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:NP1–2. doi: 10.1177/0363546511430061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koizumi W, Moriya H, Tsuchiya K, Takeuchi T, Kamegaya M, Akita T. Ludloff's medial approach for open reduction of congenital dislocation of the hip. A 20-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:924–929. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x78b6.6885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferguson AB., Jr Primary open reduction of congenital dislocation of the hip using a median adductor approach. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:671–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]