Abstract

Background:

Alcohol is widely consumed in Ireland; more so in major urban centers. Alcohol-related problems account for a significant number of Accident and Emergency (A and E) department presentations in Ireland. As a result, the national alcohol policy calls on doctors to be proactive in screening for and addressing alcohol misuse.

Aim:

The aim of the following study is to determine if patients presenting to a tertiary North Dublin A and E were asked about their alcohol use habit and if it was recorded.

Materials and Methods:

This was a descriptive observational study involving the retrospective review of case-notes for all patients who were assessed at the A and E Department of a North Dublin general hospital over a 1 week period for screening about their alcohol use habit. Data was entered into and analyzed using Microsoft Excel.

Results:

Only 17% (106/613) of the A and E attendees over the study period were asked about their alcohol use habit or had it recorded. No case-note examined documented use of alcohol screening instruments.

Conclusion:

This study has revealed an inadequacy of enquiry about alcohol use habit. In light of high rates of alcohol misuse in Ireland we suggest the need for improved enquiry/screening and recording of alcohol use among all patients attending A and E's.

Keywords: Alcohol, Screening, Recording, Accident and Emergency

Introduction

Alcohol use has been implicated in a myriad of social and medical problems.[1] Alcohol was responsible for 4% of the global disease burden in 2000; second only to tobacco use and high blood pressure.[2] The consumption of alcohol usually reflects the cultural and religious norms of that society. In Ireland, alcohol consumption is an integral part of social life and Irish people are reported to drink more than their international counterparts in all age groups; indeed Irish teenagers have been reported to have the highest rate of binge drinking in Europe.[3] In a study of prevalence of alcohol abuse in an Irish general hospital, Hearne et al. estimated that 30% of men and 8% of women met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence.[4] This figure may be as high as 40% for patients attending the Accident and Emergency (A and E).[5]

With this widespread use comes the inevitable potential for an increase in alcohol-related harm. Most harm has been reported to occur in non-dependent drinkers.[6] In recent years there has been an escalation in the health consequences of increased alcohol consumption in Ireland with a doubling of admission rates and deaths from alcohol-related liver disease.[7] The Department of Health in Ireland estimates that alcohol was responsible for about 1500 deaths in 2004.[8] And according to the Second Report of the Strategic Task Force on Alcohol[9] Ireland's alcohol-related problems continue to increase, costing Irish society in excess of €2.6 billion in 2003. In recognition of these data the Irish government endorsed and adopted the European charter on alcohol in 1995 which outlined 10 areas of health promotion by which various European governments could help curb the misuse of alcohol; ensure effective treatment services for those adversely affected by alcohol and provide information and education about potential dangers of alcohol misuse.[10] The government also launched the National Alcohol Policy in 1996 aimed at promoting the moderation of alcohol consumption for those who wish to drink, and reduce the prevalence of alcohol related problems in Ireland.[11]

Central to the success of these policy initiatives is the role of medical and allied health professionals. This is reflected in the fact that these statements underscore the role of physicians at all levels in ensuring the effective implementation of the charter with an expectation that health professionals must play a proactive role in education, identification, diagnosis and treatment of patients with alcohol-related problems[12] who present at health facilities. Internationally, agencies such as the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism have recommended that all physicians routinely ask patients about their alcohol use.[13] They are joined in this by the United States Preventative Task Force who recommended population level screening to identify problem drinking. Other agencies like the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network suggest that these be done only when there is a suspicion of alcohol abuse.[14]

However, studies in Australia, UK, USA and Finland have demonstrated that physicians infrequently screen for alcohol use disorder and that in at least a third to half of cases where the diagnosis is known that they fail to address the problem.[15,16,17] Other researchers have reported on the quality of history taking in relation to alcohol use.[6,18] A study by Farrelly et al. suggests that poor alcohol history taking is prevalent in many clinical settings.[19] It has been documented that just as in smoking where simple advice by physicians regarding effects of smoking was found to decrease rates of cigarette consumption[20], screening and brief intervention programs have beneficial long term effects in cases of alcohol misuse[21], and hospital-based psychiatric substance use consultations are reported to improve engagement in alcohol rehabilitation and treatment outcome.[22]

Bearing the afore discussed in mind and considering the national alcohol policy call for proactivity in terms of screening and detecting alcohol (mis) use in patients presenting at health facilities we set out to systematically review all case-notes of patients who were assessed at the A and E Department of a North Dublin general hospital in Ireland over a certain period in order to ascertain if indeed these patients had been asked (screened) about their alcohol use habit by the recording of this in their case-note. We hypothesized that every patient presenting to the A and E in our hospital would be screened for alcohol use and that this would be documented in their case-notes.

Materials and Methods

Setting

The study was conducted at the A and E unit of Beaumont Hospital Dublin, which is one of the largest acute general hospitals in Ireland. This academic teaching hospital situated in North Dublin was established in 1987[23] and is the Neuropsychiatric center of excellence in Ireland. It has about 54 medical specialties and provides acute and emergency care to a community of approximately 290,000 people in the North Dublin catchment area[23] with a bed complement of approximately 820 beds. The A and E unit serves approximately 45,000 patients every year with a 24 hour emergency service 365 days/year. The hospital also serves as the national tertiary referral center for neurological problems. The North Dublin area has a mixed socio-economic profile with pockets of social deprivation mixed in with working-class areas and some more prosperous suburbs.

Data collection

All consecutive attendees to the A and E unit of Beaumont hospital over a 1 week period were included in the study. A and E case-notes of these patients were identified through the A and E attendance register system. These notes were retrieved and examined for required data. This exercise was carried out by NN, GU and ME. It took approximately 7 minutes to review each case-note. Variables collected include demographic data, recording of an alcohol history, its comprehensiveness and recording of any screening tool used for alcohol use, screening for drug use and recording of a history of psychiatric problems and referral to specialist services. Results were compiled and analyzed using the Microsoft Excel. The study was approved by the Local Ethics Research Board.

Results

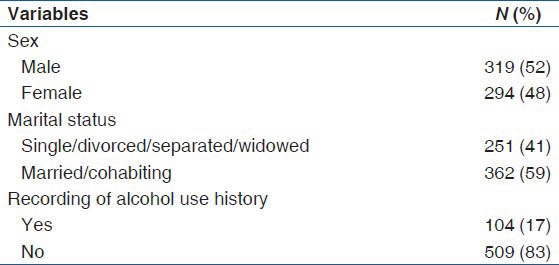

There were a total of 613 patients who attended the A and E during the study period and all their case-notes were reviewed. Males accounted for 52% (319/613) of the cohort with age ranging from 17 to 77 years. Approximately 41% (251/613) of the cohort were single, and we were unable to ascertain employment history in 99% (607/613) of the cohort as their case-notes had no recording of information relating to employment status [Table 1]

Table 1.

Summary of result

About 17% (104/613) of the cohort of case-notes had an alcohol use habit recorded (Do you drink?), while 83% (509/613) had no alcohol use history recorded. Only 5% (31/613) had a recording of units consumed, while 1% (6/613) had a recording of frequency of consumption of alcohol. The numbers who had a recording for tolerance (0.7%, 4/613) or withdrawal symptoms (0.5%, 3/613) in their case-notes were quite low.

None of the case-notes examined documented the use of any formal alcohol screening instrument. Only 0.7% (4/613) had any recording of pharmacological treatment for alcohol use. Less than 1% (4/613) of the case-notes had a recording for patients who received detoxification, all of whom were referred to alcohol treatment services. Approximately 5% (31/613) of the case-notes had the patients documented as having co-morbid psychiatric problems but only 1% (6/613) were documented as having been referred to liaison psychiatry. Only 1% (6/613) of the case-notes examined had a recreational drug use history recorded.

Discussion

We found a relatively low rate of screening for alcohol use history in the A and E of our hospital. Although other studies have found a low frequency of screening for alcohol use disorder amongst physicians[15], most have focused on physicians in primary care with a few documenting a low frequency of clinician enquiry about alcohol use in specialist settings.[24,25] Indeed considering that the A and E is a gatekeeper for the inpatient hospital care, the low numbers screened on a background of high prevalence of use of alcohol in Ireland, could have an important impact on the quality of treatment provided at hospitals including missed opportunities for alcohol (mis) use intervention in those who would otherwise have been identified as having a problem with alcohol use. This runs contrary to the spirit of the national alcohol policy documented by the Irish government in order to address alcohol difficulties in the country.

Interestingly, we found no evidence of use of any alcohol screening instruments even though nearly 1 in 6 patients had an enquiry about their alcohol use. Where patients had a slightly more detailed enquiry about their alcohol use, quantity (5%) and frequency (1%) were often the questions asked. This is reflective of previous findings by illustrated in the meta-analysis by Mitchell et al.[15]

Several barriers have been cited as affecting enquiry into, and the quality of enquiry about alcohol use habit. These include lack of time[26], inadequate training[27] and a belief that patients will not disclose their drinking habits.[28] The latter is controversial as some authors have shown that in most instances patients are not disagreeable when questioned about their alcohol use.[29,30] Indeed a meta-analysis by Mitchell et al. suggests that patients will disclose their alcohol history if asked in a sensitive manner.[15] In addition, medical education has been shown to lead to improvements in the detection of alcohol misuse.[31] As such all doctors (new or experienced) at the A and E and the hospital as a whole need regular refresher training in detecting, recording and managing alcohol (mis) use as part of routine medical assessment. There is also a potential role for alcohol liaison nurses who may focus on brief intervention, (which has been shown to be beneficial in harmful drinkers)[21] and ensure proper linkage with general practitioners and alcohol service for rapid intervention.

Other ways of addressing the deficit in enquiry about and recording of alcohol use could involve the redesign of A and E case-notes with the incorporation of a dedicated section for recording an alcohol history. This will serve as a reminder to busy doctors and health care professionals to enquire about alcohol use and to record it. There are medico-legal implications of not recording/documenting a history if it were enquired about. This dedicated section on the case-note would serve to protect the healthcare professional and hospital from charges of professional incompetence, and for the patient, would serve to ensure that they receive proper and adequate professional management/care on presentation to hospital.

Limitations

This is an exploratory descriptive study and as such we have not examined the reasons for the low rates of recording of substance use history. It is possible that lack of awareness, high case load of A and E staff, and as such a lack of time explains the deficiency in recording a substance use history. In addition it may be the case that the patients did have an alcohol use history taken but not recorded, but our study has focused solely on the recording/documentation of this history and used this as a proxy measure for screening of patients presenting to hospitals for their alcohol use. Since we did not set this study up as analytical study we have not examined the link between being asked about alcohol use history and symptom at presentation. This will be undertaken at a future study.

Future work should focus on education to improve screening and enquiry in this area as this has been shown to improve diagnostic habits.[15,27]

Conclusion

Our study has revealed a deficiency in the recording of and screening for alcohol use history in a major urban hospital in Ireland. Although alcohol misuse is common in Ireland most patients in our cohort had not been asked about this problem by their doctors at first point of contact with the hospital usually the A and E, and/or where it has been asked, it has not been recorded. This may lead to lack of identification of alcohol misuse and dependence and its early treatment, thus hampering the full and proper implementation of the national alcohol action plan.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Eckardt MJ, Harford TC, Kaelber CT, Parker ES, Rosenthal LS, Ryback RS, et al. Health hazards associated with alcohol consumption. JAMA. 1981;246:648–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. The World Health Report 2002. Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smyth B, Keenan E, Flannery W, Scully M. Calling time on Alcohol advertising and sponsorship in Ireland. Supporting a ban on Alcohol Advertising in Ireland. Protecting Children and Adolescents-A Policy paper by the Faculty of addiction psychiatry, Irish College of Psychiatrists. 2008. [Last accessed on 10 August 2012]. Available from: http://www.irishpsychiatry.ie .

- 4.Hearne R, Connolly A, Sheehan J. Alcohol abuse: Prevalence and detection in a general hospital. J R Soc Med. 2002;95:84–7. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.95.2.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conigrave KM, Burns FH, Reznik RB, Saunders JB. Problem drinking in emergency department patients: The scope for early intervention. Med J Aust. 1991;154:801–5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1991.tb121368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proude EM, Conigrave KM, Britton A, Haber PS. Improving alcohol and tobacco history taking by junior medical officers. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:320–5. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mongan D, Reynolds S, Fanagan S, Long J. Dublin: Health Research Board; 2002. Health related consequences of problem alcohol use overview 6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dublin: Health Promotion Unit, Dept. of Health and Children; 2004. Department of Health and Children. Strategic Task Force on Alcohol: Second Report. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strategic Task force on Alcohol, Second report. 2004. [Last accessed on 29 December 2013]. Available from: http://www.drugs.ie/resourcesfiles/reports/886-STFASECONDreport.pdf .

- 10.European charter on alcohol. 1995. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/Document/EUR_ICP_ALDT_94_03_CN01.pdf .

- 11.National Alcohol Policy. Executive summary report 1996. 1996. Available from: http://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/5262/1/1254-1013.pdf .

- 12.Irish College of General Practitioners. Submission to the Advisory Council on Health Promotion. 1991. Available from: http://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/5262/1/1254-1013.pdf .

- 13.Rockville, MD: The Institute; 1995. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The Physicians Guide to Helping Patients with Alcohol Problems, NIH Publications 95-3769. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scottish Intercollegiate Network Guidelines. The Management of harmful Drinking and Alcohol Dependence in Primary Care. National Clinical Guidelines. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Bird V, Rizzo M. Clinical recognition and recording of alcohol disorders by clinicians in primary and secondary care: Meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:93–100. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.091199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rydon P, Redman S, Sanson-Fisher RW, Reid AL. Detection of alcohol-related problems in general practice. J Stud Alcohol. 1992;53:197–202. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aalto M, Pekuri P, Seppä K. Primary health care professionals’ activity in intervening in patients’ alcohol drinking during a 3-year brief intervention implementation project. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69:9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor S. Changes in alcohol history taking by psychiatric junior doctors, an audit. Ir J Psychol Med. 1995;12:37–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrell MP, David AS. Do psychiatric registrars take a proper drinking history? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988;296:395–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6619.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stead LF, Bergson G, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16(2):CD000165. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub3. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Dauser D, Burleson JA, Zarkin GA, Bray J. Brief interventions for at-risk drinking: Patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness in managed care organizations. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:624–31. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hillman A, McCann B, Walker NP. Specialist alcohol liaison services in general hospitals improve engagement in alcohol rehabilitation and treatment outcome. Health Bull (Edinb) 2001;59:420–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. [Last accessed on 2013 May 20]. Available from: http://www.beaumont.ie/about/

- 24.Huang MC, Yu CH, Chen CT, Chen CC, Shen WW, Chen CH. Prevalence and identification of alcohol use disorders among severe mental illness inpatients in Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63:94–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aira M, Kauhanen J, Larivaara P, Rautio P. Factors influencing inquiry about patients’ alcohol consumption by primary health care physicians: Qualitative semi-structured interview study. Fam Pract. 2003;20:270–5. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson L, Ries R, Russo J. Barriers to identification and treatment of hazardous drinkers as assessed by urban/rural primary care doctors. J Addict Dis. 2003;22:79–90. doi: 10.1300/J069v22n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seale JP, Shellenberger S, Boltri JM, Okosun IS, Barton B. Effects of screening and brief intervention training on resident and faculty alcohol intervention behaviours: A pre- post-intervention assessment. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-6-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mäkelä P, Havio M, Seppä K. Alcohol-related discussions in health care-A population view. Addiction. 2011;106:1239–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller PM, Thomas SE, Mallin R. Patient attitudes towards self-report and biomarker alcohol screening by primary care physicians. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:306–10. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaughwin M, Dodding J, White JM, Ryan P. Changes in alcohol history taking and management of alcohol dependence by interns at The Royal Adelaide Hospital. Med Educ. 2000;34:170–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cornuz J, Ghali WA, Di Carlantonio D, Pecoud A, Paccaud F. Physicians’ attitudes towards prevention: Importance of intervention-specific barriers and physicians’ health habits. Fam Pract. 2000;17:535–40. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.6.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]