Abstract

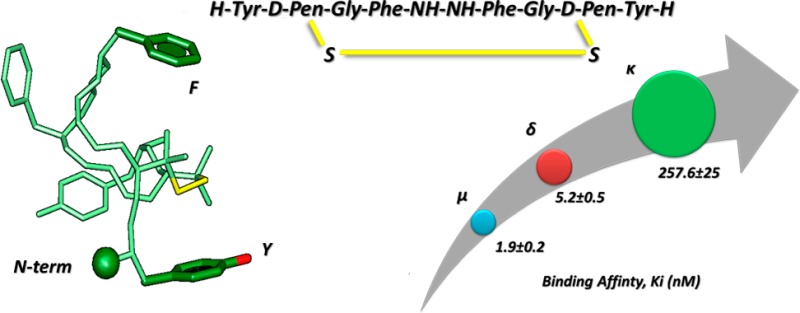

Two novel opioid analogues have been designed by substituting the native d-Ala residues in position 2,2′ of biphalin with two residues of d-penicillamine or l-penicillamine and by forming a disulfide bond between the thiol groups. The so-obtained compound 9 containing d-penicillamines showed excellent μ/δ mixed receptor affinities (Kiδ = 5.2 nM; Kiμ = 1.9 nM), together with an efficacious capacity to trigger the second messenger and a very good in vivo antinociceptive activity, whereas product 10 was scarcely active. An explanation of the two different pharmacological behaviors of products 9 and 10 was found by studying their conformational properties.

Keywords: Analgesics, biphalin, dimeric opioid peptides, cyclic analogues

In the field of dimeric opioid peptides, biphalin presents a unique structure based on two enkephalin-like branch (H-Tyr-d-Ala-Gly-Phe, 1) linked by a hydrazine moiety.1,2 Its noticeable bioactivity is due to the peculiar structure, which has the ability to match the topographical requirements for both μ and δ opioid receptors.3−5 Furthermore, this opioid octapeptide induces less physical dependence and toxicities than other opioids.6−8

Unfortunately, structural flexibility, scarce metabolic and chemical stability, low bioavailability, and distribution represent some of the major problems concerning the use of native opioid peptides as drugs when administered in vivo.9 Different approaches have been explored in an effort to overcome these limits, including the use of d-amino acids, β-homoamino acids, other types of nonproteinogenic residues, cyclization, and their combinations.10−13 Particularly appealing is the cyclization of peptides, which has been demonstrated to be a useful approach for developing diagnostic and therapeutic peptidic and peptidomimetic drugs. Cystine or penicillamine containing cyclic peptides are often obtained by substituting nonbonding residues in the linear native peptide sequence with two Cys or Pen residues, followed by oxidation of the thiol groups.14−16 If compared with the corresponding linear peptides, cyclic derivatives have shown a great improvement of the conformational rigidity, premising meaningful conformational studies to determining the bioactive conformation. Cyclic peptides are blocked to assume the best conformation to interact with their specific receptors, thus the loss of internal rotational entropy compared to the linear analogues upon binding should be smaller.17,18 Cyclic peptides offer advantages over linear peptides in terms of (i) stability; (ii) conformational rigidity; and (iii) suited templates for orally available small molecule.5,14−16

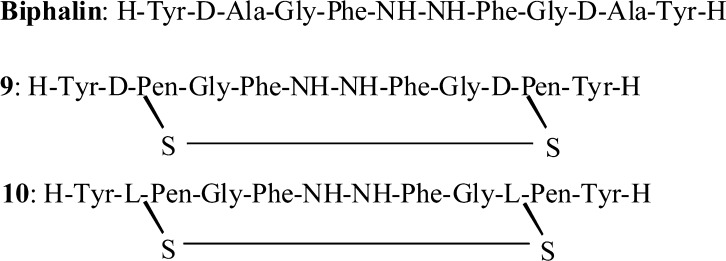

In the last decades we extensively studied several linear and cyclic biphalin analogues,19−21 and in the present study, we pointed our attention to the design of two novel cyclic biphalin-like structures, as part of our program in search for new antinociceptive agents. This work reports the synthesis, the in vitro and in vivo biological activity, and the conformational analysis of two novel cyclic biphalin analogues 9 and 10 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structures of biphalin and derivatives 9 and 10.

We initiated this research with the aim to optimize the previous reported first cyclic model of biphalin containing a disulfide bridge.19−21 Since advantages of using penicillamine residues in place of cysteine were already shown, especially in the field of DPDPE and its derivatives,14,22−24 the original design of cyclic biphalin analogues was modified accordingly. Thus, two novel cyclic biphalin analogues (9 and 10) were developed (Figure 1), and their in vitro biological activities were tested. The analgesic activity of the most active model 9 was further investigated by in vivo studies. The cyclic final products 9 and 10 were synthesized starting from the previously reported tetrapeptide 2·TFA-(H-Gly-Phe-NH−)2 by symmetrically coupling the remaining two amino acids (see Scheme 1).19−21 It is worth noting that no protecting group was adopted for the side chain of the penicillamine residues since the thiol groups were stable in the condition of the reactions.

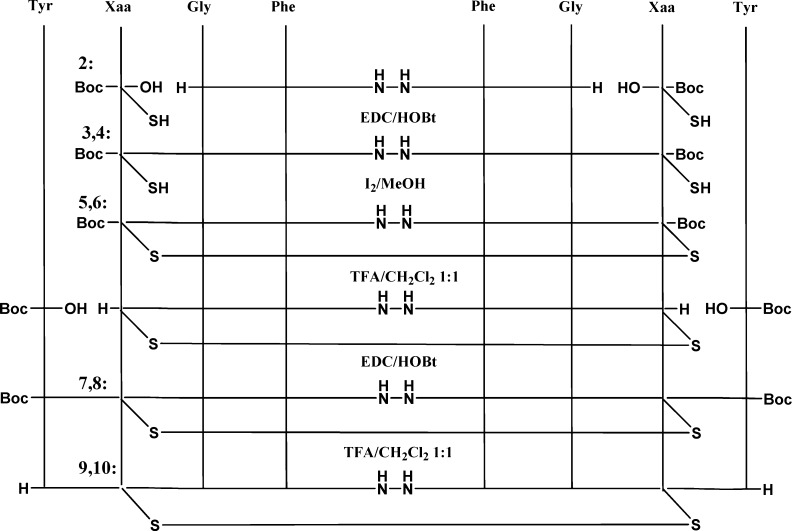

Scheme 1. Syntheses of Biphalin Analogues 9 and 10 from Tetrapeptide 2.

Reference (10). Compounds 3,5,7,9: Xaa = d-Pen. Compounds 4,6,8, 10: Xaa = l-Pen.

Cyclization was obtained by the oxidation of the thiols group of the d-Pen or l-Pen residues by a treatment of the peptides 3 and 4 with a mixture of MeOH/I2. The resultant cyclic intermediate products 5 and 6 were deprotected in standard conditions by TFA/DCM and used for the next coupling without further purification to give the final Boc-protected products 7 and 8. Products 9 and 10 were purified as TFA salts.

To determine the affinity to the μ-opioid receptor (MOR),25,26 the δ-opioid receptor (DOR), and to the κ-opioid receptor (KOR) of compounds 9 and 10, tritiated opioid peptides DAMGO ([3H]-[d-Ala2,N-Me-Phe4,Gly-ol5]enkephalin), Ile5,6deltorphin II, and U69593 (selective agonists for MOR, DOR, and KOR, respectively) were used. Ki values are shown in Table 1 (binding curves are shown in Figure S1, Supporting Information). Analogue 9 has a very good μ and δ opioid receptor affinity, showing comparable Ki values with respect to biphalin for MOR (Ki = 1.9 nM), DOR (Ki = 5.2 nM), and KOR (Ki = 260 nM). Analogue 10 shows very low affinity for all opioid receptors.

Table 1. Binding Affinity and in Vitro Bioactivity for Compounds 9 and 10.

| binding affinity,aKi (nM)b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| compd | δ | μ | κ |

| Ctrlc | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 5.7 ± 0.5 |

| Bph | 15 ± 2.3 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 283.1 ± 182.3 |

| 9 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 257.6 ± 25 |

| 10 | amb. | amb. | amb. |

Displacement of [3H]Ile5,6deltorphin II (δ-ligand), [3H]DAMGO (μ-ligand), and [3H]U69593 (κ-ligand) from binding sites on rat brain membrane.

±SEM.

The control was the appropriate opioid receptor specific ligand. amb.: ambiguous fitting since the compound can inhibit specific receptor binding significantly only in the highest concentration.

Isolated tissue based functional assays were also performed on guinea pig ileum/longitudinal muscle myenteric plexus (GPI) and mouse vas deferens (MVD) (Table 2).27−29 While compound 9 was potent in inhibiting muscle contraction both in MVD (expressing DOR) and in GPI (expressing MOR) assays, analogue 10 showed activity only in the micromolar range. These data are coherent with those obtained from the binding assays.

Table 2. [35S]GTPγS Binding (G-Protein Activation) and Functional Assays.

| δ

receptor |

μ receptor |

κ receptor |

bioassay, IC50d (nM)b |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | Emax (%)a | EC50 (nM)b | Emax (%)a | EC50 (nM)b | Emax (%)a | EC50 (nM)b | MVD (δ) | GPI (μ) |

| Ctrlc | 142.6 ± 1.4 | 7.7 ± 1.9 | 465.2 ± 7.7 | 81 ± 12 | 202 ± 3.3 | 7.7 ± 1.8 | ||

| Bph | 219.6 ± 5.7 | 90.5 ± 25 | 178.2 ± 3.6 | 12 ± 4.6 | 108.9 ± 4.1 | amb. | 27 ± 15e | 8.8 ± 0.3e |

| 9 | 149.5 ± 2.3 | 7.1 ± 1.7 | 474.5 ± 4.1 | 76.2 ± 7.4 | 126.8 ± 4.4 | 480 ± 385 | 7.2 ± 0.8 | 21 ± 4 |

| 10 | 142.6 ± 2.8 | 360 ± 121 | 162.2 ± 3.2 | 230 ± 82 | 124.5 ± 2.7 | 205.1 ± 137 | 21% at 1 mM | 4% at 1 mM |

Net total bound/basal binding × 100 ± SEM.

±SEM.

The control was the corresponding opioid receptor specific ligand (δ, Ile5,6deltorphine II; μ, DAMGO; and κ, U69593).

Concentration at 50% inhibition of muscle contraction in electrically stimulated isolated tissues (n = 4).

The ability of 9 and 10 to stimulate the activation of G-proteins associated with the opioid receptors has been evaluated by [35S]GTPγS binding assay (Table 2 and Figure S2, Supporting Information).30−33 Analogue 9 has a similar μ and δ opioid receptor activation profile as specific opioid ligands (DAMGO and Ile5,6deltorphin II), unlike the κ opioid receptor. Furthermore, compound 9 has a significantly higher efficacy than biphalin in activating MOR. Interestingly, its efficacy (Emax) on MOR is also higher than that of the cyclic Cys derivatives.19−21

According to other in vitro assays, compound 10 shows a lower activity for all receptors.

Overall in vitro results clearly suggest that d-residues in position 2,2′ are crucial for opioid receptor affinity, which is in accordance with our previous SAR.19−21 Thus, ligand 10, which possesses a disulfide bridge between l-penicillamines displays a remarkable loss of activity when compared to 9 and biphalin, displaying reduced binding affinities for DOR and MOR, as well as for all the functional activities in the [35S]GTPγS binding and the functional assays.

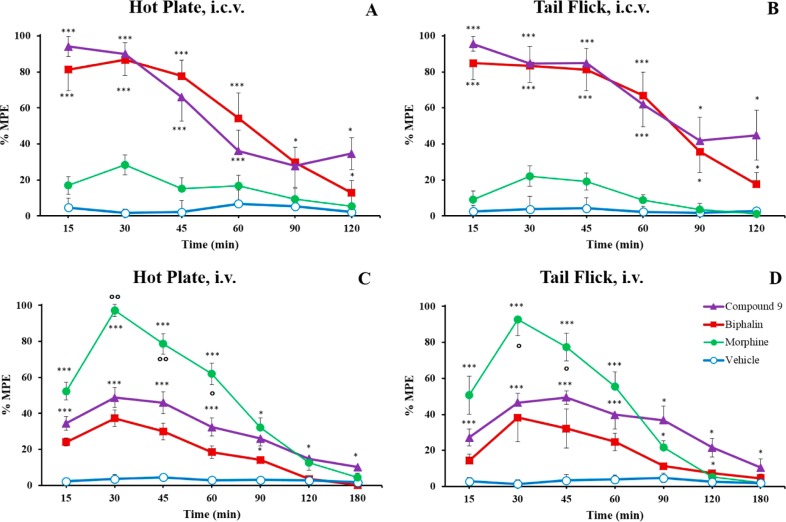

Product 9 was also tested in vivo for its antinociceptive activity. In the “hot plate” and “tail flick” tests, analogue 9 produced about 95% of the MPE 15 min after i.c.v. administration. The maximum effect was obtained 15–30 min after drug injection, and minimal decrease was observed for the next 30 min in both in vivo models (Figure 2). Product 9 showed an activity several times higher than morphine after i.c.v. administration. Following i.v. administration (“hot plate” and “tail-flick” tests), compound 9 displayed a greater and longer lasting antinociceptive effect than biphalin, thus suggesting a likely improvement of the pharmacokinetic parameters if compared to biphalin, in accordance with the cyclization strategy.34,35 Also, the increased efficacy of 9 at the MOR with respect to biphalin should play a role in this antinociceptive effect. For detailed experimental procedures36,37 see Supporting Information.

Figure 2.

Antinociceptive results, reported as maximum possible effect (MPE), of hot plate and tail flick in vivo bioassays for compound 9, biphalin, and morphine sulfate. Compounds were injected i.c.v. (A,B) at a dose of 0.1 nmol/rat and systemic i.v. administration (C,D) at a dose of 1500 nmol/kg. The data represent the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assumed for P < 0.05. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 vs vehicle-treated animals; °P < 0.05 and °°P < 0.01 vs biphalin-treated animals. N = 8–10.

The bioactivity of 9 is still lower than morphine following i.v. administration probably due to a reduced blood–brain barrier penetration of 9 compared to morphine.

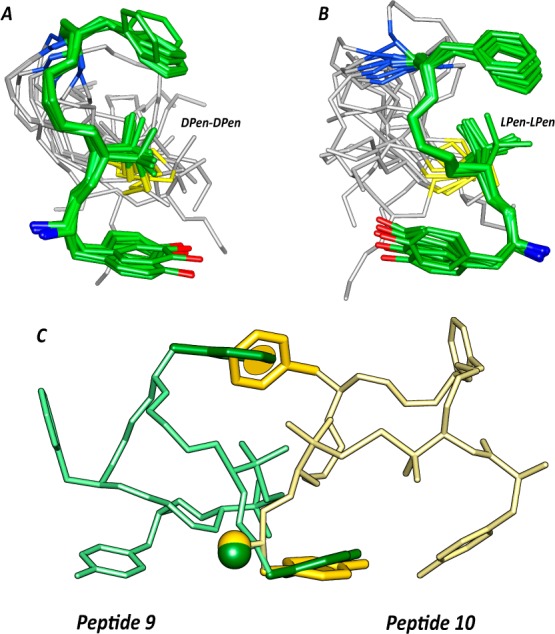

To explain the activity differences between 9 and 10, a conformational analysis of the two analogues was carried out by solution NMR (Supporting Information, Tables S1–S5). Dodecylphosphocoline (DPC) micelle solution was used to mimic a membrane environment considering that opioid peptides interact with membrane receptors.38,39 Using the NMR data as input, structure calculations by restrained simulated annealing gave the conformers shown in Figure 3. More details are reported in the Supporting Information.

Figure 3.

Superposition of the ten lowest energy conformers of 9 (A) and 10 (B). Structure models were superimposed using the backbone heavy atoms of residues 1–4. Heavy atoms have different colors (carbon, green; nitrogen, blue; oxygen, red; sulfur, yellow). Hydrogen atoms are hidden for a better view. (C) Superposition of peptides 9 (green) and 10 (yellow) using the three pharmacophoric points, i.e., terminal amino group (Nterm), center of the Tyr phenol (Y), and center of the Phe phenyl ring (F).

Both peptides 9 and 10 show a well-defined structure encompassing residues 1–4 (backbone root-mean-square deviation values are 0.27 and 0.21 Å, respectively). A γ-turn centered on Gly3 is seen in peptide 9 (Figure 3A,B; Table S5, Supporting Information). As expected from the NOE cross-peaks between the aromatic rings and the methyl groups of d-Pen2 (Figure S3, Supporting Information), a sandwich-like π-CH3-π geometry of the signal sequence of the peptides was observed.

Peptide 9 has similar activity profile of the linear parent biphalin (MOR and DOR agonist) and different from DPDPE, which inspired the d-Pen–d-Pen bridge (selective DOR agonist).14 To explain peptide 9’s lack of μ/δ selectivity, we considered the distances between pharmacophoric points obtained by restrained molecular dynamics (Figure S4, Supporting Information). Indeed, these distances are compatible with both μ and δ opioid receptors.40,41 In fact, considering μ-selective peptides, the distances between the aromatic rings of Tyr1 and Phe4 should be in the range 10–13 Å,40 while the range characteristic for peptide and nonpeptide δ-selective compounds is about 7 Å.41 We found this distance ranging between 6 and 12 Å in peptide 9 (Figure S4c, Supporting Information) thus fitting both the pharmacophores.

In contrast, κ-receptor agonists require a shorter Tyr1 and Phe4 distance (about 5 Å) and a g– orientation of the Tyr1 side chain.42 Those criteria are both unsatisfied by peptide 9. Finally, the inactivity of peptide 10 can be tentatively explained by a comparison of the peptide structures (Figure 3C). As observed, while the three pharmacophoric points (i.e., terminal amino group, center of the Tyr phenol, and center of the Phe phenyl ring) overlap very efficiently, the backbone atoms of residues 2–4 are not overlapping and the palindromic fragments (residues 1′–4′) point in opposite directions.

Those nonfitting regions probably form incompatible interactions with the receptors in the case of peptide 10 thus accounting for its lack of activity.

In conclusion, we have successfully developed two novel cyclic biphalin analogues. Compound 9, containing a d-Pen residue at position 2,2′, showed improved in vitro and in vivo activity compared to biphalin. According to previous SARs, compound 10, containing l-Pen, was virtually inactive. Conformational analysis pointed to a different 3D structure of the two analogues explaining their activity profiles. Further studies on the promising novel compound 9 using additional animal models are currently underway.

Supporting Information Available

Synthetic procedures, characterization of intermediates and final products, biological assays, NMR analysis, and structure calculations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lipkowski A. W.; Konecka A. M.; Sroczynska I. Double-enkephalins-synthesis, activity on guinea-pig ileum, and analgesic effect. Peptides 1982, 3, 697–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciani F.; Pinnen F.; Stefanucci A.; Costante R.; Cacciatore I.; Lucente G.; Mollica A. Structure-activity relationships of biphalin analogs and their biological evaluation on opioid receptors. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 11–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portoghese P. S. From models to molecules: opioid receptor dimers, bivalent ligands, and selective opioid receptor probes. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 2259–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkowski A. W.; Misicka A.; Davis P.; Stropova D.; Janders J.; Lachwa M.; Porreca F.; Yamamura H. I.; Hruby V. Biological activity of fragments and analogues of the potent dimeric opioid peptide, biphalin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999, 9, 2763–2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbert B. S.; Lipkowski A. W.; Cepeda M. S.; Szyfelbein S. K.; Osgood P. F.; Carr D. B. Analgesic activity of a novel bivalent opioid peptide compared to morphine via different routes of administration. Agents Actions 1991, 3, 382–387.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan P. J.; Mattia A.; Bilsky E. J.; Weber S.; Davis T. P.; Yamamura H. I.; Malatynska E.; Appleyard S. M.; Slaninova J.; Misicka A. Antinociceptive profile of biphalin, a dimeric enkephalin analog. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993, 265, 1446–1454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki M.; Suzuki T.; Narita M.; Lipkowski A. W. The opioid peptide analogue biphalin induces less physical dependence than morphine. Life Sci. 2001, 69, 1023–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbruscato T. J.; Thomas S. A.; Hruby V. J.; Davis T. P. Brain and spinal cord distribution of biphalin: correlation with opioid receptor density and mechanism of CNS entry. J. Neurochem. 1997, 69, 1236–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tömböly C.; Péter A.; Tóth G. In vitro quantitative study of the degradation of endomorphins. Peptides 2002, 23, 1573–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica A.; Pinnen F.; Costante R.; Locatelli M.; Stefanucci A.; Pieretti S.; Davis P.; Lai J.; Rankin D.; Porreca F.; Hruby V. J. Biological active analogues of the opioid peptide biphalin: mixed α/β3-peptides. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 3419–3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica A.; Pinnen F.; Stefanucci A.; Feliciani F.; Campestre C.; Mannina L.; Sobolev A. P.; Lucente G.; Davis P.; Lai J.; Ma S. W.; Porreca F.; Hruby V. J. The cis-4-amino-l-proline residue as a scaffold for the synthesis of cyclic and linear endomorphin-2 analogues. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3027–3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica A.; Pinnen F.; Stefanucci A.; Mannina L.; Sobolev A. P.; Lucente G.; Davis P.; Lai J.; Ma S. W.; Porreca F.; Hruby V. J. cis-4-Amino-l-proline residue as a scaffold for the synthesis of cyclic and linear endomorphin-2 analogues: part 2. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 8477–8482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruby V. J. Designing peptide receptor agonists and antagonists. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2002, 1, 847–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosberg H. I.; Hurst R.; Hruby V. J.; Gee K.; Yamamura H. I.; Galligan J. J.; Burks T. F. Bis-penicillamine enkephalin possess highly improved specificity toward delta opioid receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1983, 80, 5871–5874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieleniak A.; Rodziewicz-Motowidło S.; Rusak L.; Chung N. N.; Czaplewski C.; Witkowska E.; Schiller P. W.; Ciarkowski J.; Izdebski J. Deltorphin analogs restricted via a urea bridge: structure and opioid activity. J. Pept. Sci. 2008, 14, 830–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weltrowska G.; Berezowska I.; Lemieux C.; Chung N. N.; Wilkes B. C.; Schiller P. W. N-Methylated cyclic enkephalin analogues retain high opioid receptor binding affinity. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2010, 75, 82–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezowska I.; Chung N. N.; Lemieux C.; Wilkes B. C.; Schiller P. W. Dicarba Analogues of the cyclic enkephalin peptides H-Tyr-c[d-Cys-Gly-Phe-d (or l)-Cys]NH2 retain high opioid activity. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 1414–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica A.; Guardiani G.; Davis P.; Ma S. W.; Porreca F.; Lai J.; Mannina L.; Sobolev A. P.; Hruby V. J. Synthesis of stable and potent δ/μ opioid peptides: analogues of H-Tyr-c[d-Cys-Gly-Phe-d-Cys]-OH by ring-closing metathesis. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 3138–3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica A.; Davis P.; Ma S. W.; Porreca F.; Lai J.; Hruby V. J. Synthesis and biological activity of the first cyclic biphalin analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 367–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica A.; Costante R.; Stefanucci A.; Pinnen F.; Lucente G.; Fidanza S.; Pieretti S. Antinociceptive profile of potent opioid peptide AM94, a fluorinated analogue of biphalin with non-hydrazine linker. J. Pept. Sci. 2013, 19, 233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone S.; Chiavaroli A.; Orlando G.; Mollica A.; Di Nisio C.; Brunetti L.; Vacca M. The analgesic activity of biphalin and its analog AM 94 in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 685, 70–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froimowitz M.; Hruby V. J. Conformational analysis of enkephalin analogs containing a disulfide bond. Models for δ and μ-receptor opioid agonists. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1989, 34, 88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruby V. J.; Gehrig C. A. Recent developments in the design of receptor specific opioid peptides. Med. Res. Rev. 1989, 9, 343–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosherg H. I.; Hurst R.; Hruby V. J.; Galligan J. J.; Burks T. F.; Gee K.; Yamanura H. I. [d-Pen2,l-Cys5] Enkephalinamide and [d-Pen2,d-Cys5]enkephalinamide, conformationally constrained cycle enkephalinamide analogues with delta receptor specificity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1982, 106, 506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevin S. T.; Kabasakal L.; Ötvös F.; Tóth G.; Borsodi A. Binding characteristics of the novel highly selective delta agonist, [3H-Ile5,6]deltorphin II. Neuropeptides 1994, 26, 261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojnik E.; Farkas J.; Magyar A.; Tömböly C.; Güçlü U.; Gündüz O.; Borsodi A.; Corbani M.; Benyhe S. Selective and high affinity labeling of neuronal and recombinant nociceptin receptors with the hexapeptide radioprobe [(3)H]Ac-RYYRIK-ol. Neurochem. Int. 2009, 55, 458–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polt R. L.; Porreca F.; Szabo L. Z.; Bilsky E. J.; Davis P.; Abbruscato T. J.; Davis T. P.; Horvath R.; Yamamura H. I.; Hruby V. J. Glycopeptide enkephalin analogues produce analgesia in mice: evidence for penetration of the blood-brain barrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994, 91, 7114–7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci M.; Mastriota M.; Maione F.; Di Giannuario A.; Mascolo N.; Palmery M.; Severini C.; Perretti M.; Pieretti S. Guinea pig ileum motility stimulation elicited by N-formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLF) involves neurotransmitters and prostanoid. Peptides 2011, 32, 266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer T. H.; Davis P.; Hruby V. J.; Burks T. F.; Porreca F. In vitro potency, affinity and agonist efficacy of highly selective delta opioid receptor ligands. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993, 266, 577–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidhammer H.; Burkard W. P.; Eggstein-Aeppli L.; Smith C. F. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 14-alkoxymorphinans. 2. (−)-N-(Cyclopropylmethyl)-4,14-dimethoxymorphinan-6-one, a selective mu opioid receptor antagonist. J. Med. Chem. 1989, 32, 418–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim L. J.; Selley D. E.; Childers S. R. In vitro autoradiography of receptor-activated G proteins in rat triphosphate binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995, 92, 7242–7246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynor R.; Nahorski R.; Traynor J. R.; Nahorski S. R. Modulation by mu-opioid agonists of guanosine-5′-O-(3-[35S]thio)triphosphate binding to membranes from human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995, 47, 848–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekeres P. G.; Traynor J. R. δ opioid modulation of the binding of guanosine-5′-O-(3-[35S]thio)triphosphate to NG108–15 cell membranes: characterization of agonist and inverse agonist effects. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997, 283, 1276–1284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egleton R. D.; Davis T. P. The development of neuropeptide drugs that cross the blood-brain barrier. J. Am. Soc. Exp. NeuroTher. 2005, 2, 44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilucci L. New trends in the development of opioid peptide analogues as advanced remedies for pain relief. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2004, 4, 19–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida J.; Murray R. B. Manual of pharmacologic calculations with computer programs. Second edition. J. Pharm. Sci. 1988, 77, 284. [Google Scholar]

- Pieretti S.; Di Giannuario A.; De Felice M.; Perretti M.; Cirino G. Stimulus-dependent specificity for annexin 1 inhibition of the inflammatory nociceptive response: the involvement of the receptor for formylated peptides. Pain 2004, 109, 52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cianni A.; Carotenuto A.; Brancaccio D.; Novellino E.; Reubi J. C.; Beetschen K.; Papini A. M.; Ginanneschi M. Novel octreotide dicarba-analogues with high affinity and different selectivity for somatostatin receptors. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 6188–6197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T.; Nair P.; Jacobsen N. E.; Davis P.; Navratilova E.; Moye S.; Lai J.; Yamamura H. I.; Vanderah T. W.; Porreca F.; Hruby V. J. The importance of micelle-bound states for the bioactivities of bifunctional peptide derivatives for δ/μ opioid receptor agonists and neurokinin 1 receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 6334–6347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki T.; Ro S.; Goodman M.; Chung N. N.; Schiller P. W. A topochemical approach to explain morphiceptin bioactivity. J. Med. Chem. 1993, 36, 708–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenderovich M. D.; Liao S.; Qian X.; Hruby V. J. A three-dimensional model of the δ-opioid pharmacophore: comparative molecular modeling of peptide and nonpeptide ligands. Biopolymers 2000, 53, 565–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. C.; Lin J. S.; Hwang C. C. Structure-activity relationships of αS1-casomorphin using AM1 calculations and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 7377–7383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.