Abstract

Background

Caesarean section rates are over 20% in many developed countries. The main diagnosis contributing to the high rate in nulliparae is dystocia or prolonged labour. The present review assesses the effects of a policy of early amniotomy with early oxytocin administration for the prevention of, or the therapy for, delay in labour progress.

Objectives

To estimate the effects of early augmentation with amniotomy and oxytocin for prevention of, or therapy for, delay in labour progress on the caesarean birth rate and on indicators of maternal and neonatal morbidity.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (15 February 2012), MEDLINE (1966 to 15 February 2012), EMBASE (1980 to 15 February 2012), CINAHL (1982 to 15 February 2012), MIDIRS (1985 to February 2012) and contacted authors for data from unpublished trials.

Selection criteria

Randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials that compared oxytocin and amniotomy with expectant management.

Data collection and analysis

Three review authors extracted data independently. We stratified the analyses into ’Prevention Trials’ and ’Therapy Trials’ according to the status of the woman at the time of randomization. Participants in the ’Prevention Trials’ were unselected women, without slow progress in labour, who were randomized to a policy of early augmentation or to routine care. In ’Treatment Trials’ women were eligible if they had an established delay in labour progress.

Main results

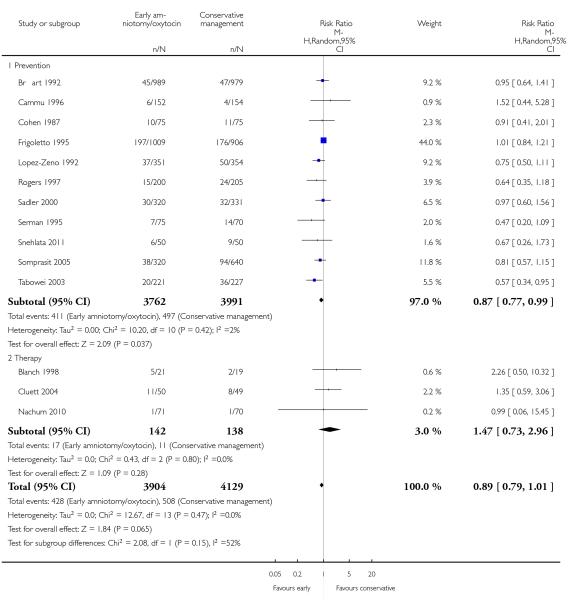

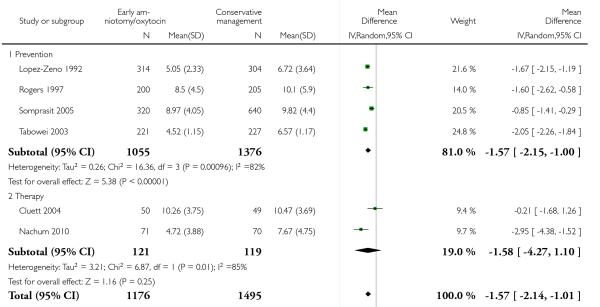

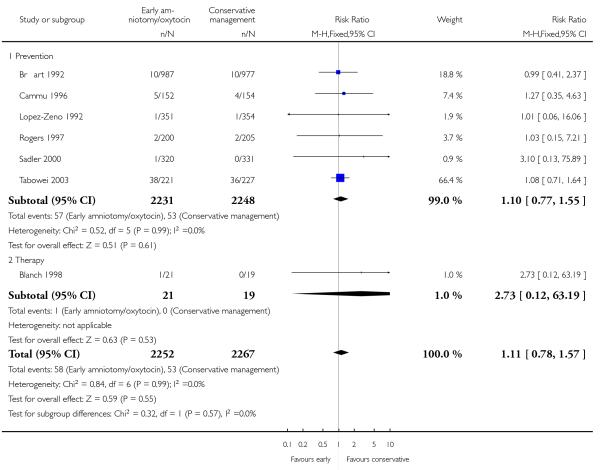

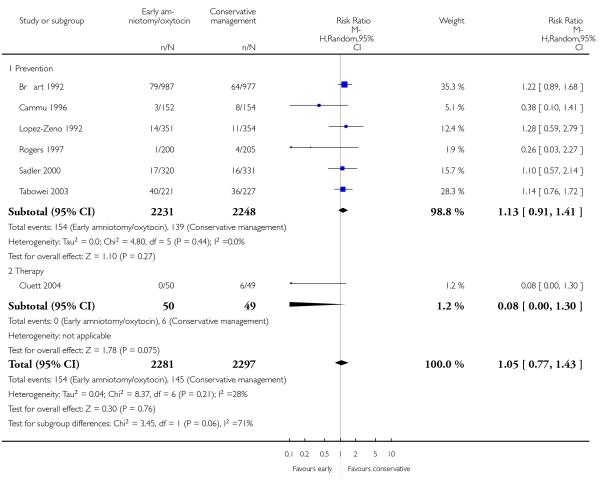

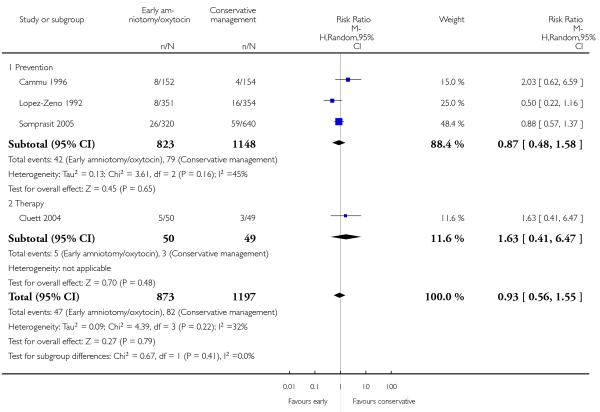

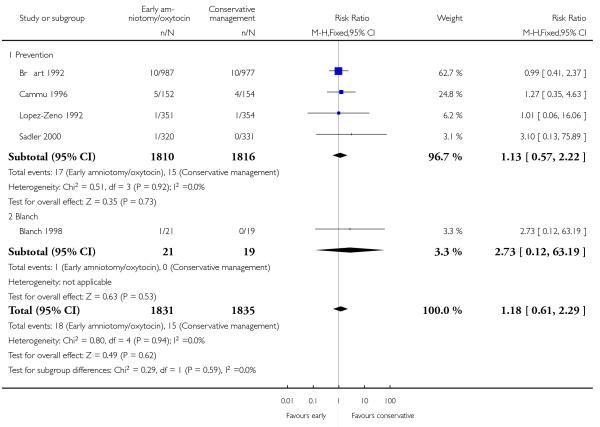

For this update, we have included a further two new clinical trials. This updated review includes 14 trials, randomizing a total of 8033 women. The unstratified analysis found early intervention with amniotomy and oxytocin to be associated with a modest reduction in the risk of caesarean section; however, the confidence interval (CI) included the null effect (risk ratio (RR) 0.89; 95% CI 0.79 to 1.01; 14 trials; 8033 women). In prevention trials, early augmentation was associated with a modest reduction in the number of caesarean births (RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.77 to 0.99; 11 trials; 7753). A policy of early amniotomy and early oxytocin was associated with a shortened duration of labour (average mean difference (MD) −1.28 hours; 95% CI −1.97 to −0.59; eight trials; 4816 women). Sensitivity analyses excluding four trials with a full package of active management did not substantially affect the point estimate for risk of caesarean section (RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.05; 10 trials; 5165 women). We found no other significant effects for the other indicators of maternal or neonatal morbidity.

Authors’ conclusions

In prevention trials, early intervention with amniotomy and oxytocin appears to be associated with a modest reduction in the rate of caesarean section over standard care.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): *Labor Stage, First; Amnion [*surgery]; Cesarean Section [utilization]; Obstetric Labor Complications [prevention & control; *therapy]; Oxytocics [*administration & dosage]; Oxytocin [*administration & dosage]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Time Factors

MeSH check words: Female, Humans, Pregnancy

BACKGROUND

Caesarean section rates are over 20% in many developed countries (Betran 2007) and have increased nearly four-fold relative to the 5% rate observed in the early 1970s (NCCWCH 2004). The main diagnosis contributing to this increase is dystocia or prolonged labour (Anderson 1989; Liu 2004). Factors such as increasing maternal age appear to have contributed to the increase in the incidence of dystocia (Treacy 2006).

The ’active management’ of labour is a clinical protocol that was designed to facilitate the organization of obstetric care in a busy labour ward. The active management of labour has been proposed as an alternative approach to the problem of dystocia, as well as a strategy to reduce the high rate of caesarean sections (O’Driscoll 1984). Active management includes: selective admission to the labour ward; selective use of electronic fetal monitoring; early intervention with amniotomy and oxytocin for delay in labour progress; routine use of a simplified 1 cm/hour partogram to guide clinical decision making; and continuous professional support. Classically, the protocol has included restricted use of epidural analgesia. To date, there is no consensus with respect to the timing of amniotomy and oxytocin administration in the presence of a delay in labour.

Description of the condition

Dystocia is a term used for delay of labour progress and usually refers to abnormally slow cervical dilatation. O’Driscoll proposed a partogram that includes, as a diagnostic criterion, a 1 cm/hour line originating at admission (O’Driscoll 1984). In contrast, Philpott suggested that the intervention threshold for dystocia should be based on an action line which is parallel to that proposed by O’Driscoll, but four hours to the right (Philpott 1982). Peisner noted that a high proportion of nulliparous women enter active phase dilatation only after 4 cm (Peisner 1986). This would argue against early intervention prior to 4 cm dilatation. The World Health Organization has proposed a modified partogram that recommends that active phase be diagnosed only at 4 cm or more (WHO 2000).

Description of the intervention

Active management is a protocol that includes strict criteria for the diagnosis of labour, early amniotomy, prompt oxytocin with high-dose oxytocin in the event of inefficient uterine action, and continuous professional support during labour. A policy of combining early amniotomy with early oxytocin administration, which are applied sequentially in the active management of labour, are the key medical components of this approach to care. Several trials which have been labelled by the author as a trial of active management have only contrasted the used of early oxytocin and early amniotomy relative to routine care. Other studies of early amniotomy and early oxytocin, not labelled as active management trials, have been conducted. This review assessed the effects of early amniotomy and early oxytocin versus a more conservative form of management in the context of care.

How the intervention might work

Active management is based on the hypothesis that the most frequent cause of dystocia is inadequate uterine action: true cephalopelvic disproportion is assumed to be an infrequent cause of dystocia (O’Driscoll 1970). Amniotomy and oxytocin are performed with the purpose of increasing the frequency and intensity of contractions. Both the administration of oxytocin and amniotomy have been demonstrated to increase the frequency and intensity of uterine contractions (Blanks 2003). As dystocia is primarily a problem of women who are in their first labour, active management focuses on nulliparous women. Clearly, the active management protocol proposes a low threshold for intervention for delay in labour progress. Early intervention is not without its risks. Uterine hyperstimulation and fetal heart rate abnormalities may result from oxytocin and amniotomy. The frequency of such complications needs to be better quantified.

Why it is important to do this review

Early amniotomy and oxytocin influence the overall organization of intrapartum obstetric care; therefore, this review is relevant to clinicians, consumers, and policy makers. For clinicians and consumers, the key issues are the effect of early augmentation in labour on indicators of morbidity and satisfaction with care. For policy makers, the key issues are the impact on the organization of care, including the appropriate settings and technical support required for routine obstetric care and their costs.

OBJECTIVES

To estimate the effects, among unselected women, of a policy of early augmentation with amniotomy and oxytocin (prevention) on the caesarean birth rate and on indicators of maternal and neonatal morbidity.

To evaluate the effects, among women with established delay in labour progress, of early augmentation with amniotomy plus oxytocin (therapy) on the caesarean birth rate and on indicators of maternal and neonatal morbidity.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized or quasi-randomized studies.

Types of participants

Pregnant women in spontaneous labour.

Types of participants are divided into two separate groups:

unselected pregnant women in spontaneous labour;

pregnant women in spontaneous labour where there is delay in the first stage.

Types of interventions

Early augmentation with amniotomy and oxytocin versus a more conservative form of management in the context of care. Trials where patients in both groups underwent amniotomy were excluded from this review.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Caesarean section rate.

Secondary outcomes

Maternal

Related to delivery method and labour duration

Spontaneous vaginal delivery

Instrumental vaginal delivery (forceps or vacuum, or both)

Length of first stage of labour

Duration of labour (duration in hours from admission in labour)

Satisfied with labour experience

Related to pain

Use of epidural analgesia

Potential adverse effects

Hyperstimulation of labour

Postpartum haemorrhage (greater than 500 mL)

Maternal blood transfusion

Postpartum fever or infection

Fetal/infant

Apgar score less than seven at five minutes

Acidosis as defined abnormal arterial cord pH (pH less than 7.10 or 7.20)

Suboptimal or abnormal fetal heart tracing

Fetal distress

Admission to special care nursery

Seizure/neurological abnormalities

Jaundice or hyperbilirubinaemia

Some outcomes proposed in the protocol were not included in the review because there were no data available in the included trials. Future updates of this review will include these outcomes if data become available. These outcomes are:

women’s use of non-epidural analgesia;

level of pain;

perineal trauma;

antepartum haemorrhage;

serious maternal morbidity or death;

maternal health service utilization (cost);

infant health service utilization (cost).

Future clinical trials are needed for these effects.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co-ordinator (15 February 2012).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co-ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ’Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co-ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

In addition, we searched MEDLINE (1966 to 15 February 2012), EMBASE (1980 to 15 February 2012), CINAHL (1982 to 15 February 2012) and MIDIRS (1985 to February 2012) (Appendix 1).

Searching other resources

We obtained data from any unpublished trials through direct communication with the authors.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, see Appendix 2.

For this update we used the following methods when assessing the reports identified by the updated search.

Selection of studies

Three review authors (SQ Wei, BL Wo and HP Qi) independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We excluded studies where women in both treatment groups underwent amniotomy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or consulted a third author (WD Fraser).

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, at least two review authors (SQW, BL Wo or HPQ) extracted the data independently. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or consulted a third author (WD Fraser). We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2011) and checked them for accuracy. When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three review authors (SQ Wei, HP Qi and HR Xu) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a fourth author (WD Fraser).

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We have described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non-random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment. We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomization; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non-opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomized participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or can be supplied by the trial authors, we re-included missing data in the analyses which we have undertaken.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. where there was no missing data or low levels of missing data,and where reasons for missing data were balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. where there were high levels of missing data or where attrition was not balanced across groups);

unclear risk of bias.(e.g. where there was insufficient reporting of attrition or exclusions to permit a judgement to be made).

(For outcomes measured in labour, we would expect low levels of missing data to be no more than 10%.)

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We have described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it was clear that all of the study’s pre-specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre-specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre-specified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We have described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias. For example, where there was a potential source of bias related to the specific study design, where the protocol changed part-way through, where there was extreme baseline imbalance, or where the study had been claimed to be fraudulent.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about risk of bias for important outcomes both within and across studies. With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on findings. We set out assessments of bias for included studies in the ’Risk of bias’ tables. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We planned to use the standardized mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster-randomized trials

We did not identify any cluster-randomized trials on this topic.

Other unit of analysis issues

We excluded cross-over trials.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition.

We analyzed data on all participants with available data in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention, on an intention-to-treat basis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We applied tests of heterogeneity between trials, if appropriate, using T2, I2 and Chi2 statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if the I2 was greater than 30% and either T2 was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi2 test for heterogeneity. If this was the case, then a random-effects meta-analysis was used as an overall summary.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where we suspected reporting bias or where missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, this has been reported.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2011). We used fixed-effect inverse variance meta-analysis for combining data where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar. Where we suspected clinical or methodological heterogeneity between studies sufficient to suggest that treatment effects may differ between trials, we used random-effects meta-analysis.

If substantial heterogeneity was identified in a fixed effect meta-analysis, the analysis was repeated using a random-effects method.

If we used random-effects analyses, the results were presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of T2 and I2.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted the following subgroup analyses.

’Prevention Trials’, which were defined as trials that included unselected women in early spontaneous labour who were allocated to either early amniotomy and oxytocin in the case of delay in progress, or to usual care.

’Therapy Trials’, which were defined as trials that only included women with an established delay in labour progress. In these trials, women had been allocated to either early amniotomy and oxytocin, or to routine care.

We conducted subgroup analyses on all outcomes.

We planned to assess differences between subgroups by interaction tests available in RevMan 2011.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out a sensitivity analysis to explore the effects of a policy of early amniotomy and oxytocin alone, without the full package of co-interventions that are usually considered as constituting active management: continuous professional care, selective admission at the labour ward. Four such studies of active management (Frigoletto 1995; Rogers 1997; Snehlata 2011; Tabowei 2003) were excluded in the sensitivity analysis in order to assess the combined effect of early amniotomy and oxytocin on the primary outcome.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

We identified 23 studies. Nine were excluded.

Included studies

Fourteen trials including 8033 women in labour were analyzed. The characteristics of the women at the time of admission to the studies are shown in Table 1. Twelve randomized control trials (Blanch 1998; Bréart 1992; Cammu 1996; Cluett 2004; Frigoletto 1995; Lopez-Zeno 1992; Nachum 2010; Rogers 1997; Sadler 2000; Snehlata 2011; Somprasit 2005; Tabowei 2003) and two quasi-randomized trials (Cohen 1987; Serman 1995) were included in this review, see Characteristics of included studies. In one study (Frigoletto 1995), randomization was performed at the beginning of the third trimester and approximately one-third of the women were excluded from the analysis after randomization as they became ineligible for the intervention. Only caesarean section (CS) was reported by intention-to-treat. This study was only included for the CS outcome. Eleven trials the enrolled women who were in normal spontaneous labour at randomization, allocating them either to early amniotomy and oxytocin if slow progress in labour ensued or to expectant management. These studies were termed ’prevention studies’ (Bréart 1992; Cammu 1996; Cohen 1987; Frigoletto 1995; Lopez-Zeno 1992; Rogers 1997; Sadler 2000; Serman 1995; Snehlata 2011; Somprasit 2005; Tabowei 2003). Three trials (Blanch 1998; Cluett 2004; Nachum 2010) which included only women with an established abnormality in the progress of labour were grouped as ’therapy’ trials. Twelve trials were conducted in nulliparous women (Bréart 1992; Cammu 1996; Cluett 2004; Cohen 1987; Frigoletto 1995; Lopez-Zeno 1992; Rogers 1997; Sadler 2000; Serman 1995; Snehlata 2011; Somprasit 2005; Tabowei 2003). Two trials were conducted in a mixed population of nulliparous and multiparous women (Blanch 1998; Nachum 2010). No studies were conducted solely in multiparous women. There were four trials of active management of labour (Frigoletto 1995; Rogers 1997; Snehlata 2011; Tabowei 2003) which, in the experimental intervention, included strict criteria for the diagnosis of labour, early amniotomy, prompt oxytocin with high-dose oxytocin in the event of inefficient uterine action and continuous professional support.

In all studies, the more interventionist policy consisted of early amniotomy if membranes were intact and early oxytocin infusion. Oxytocin was used in women in the control group if a more marked delay in labour progress ensued. The severity of delay which justified oxytocin augmentation in the control group varied from usual care to an eight-hour period of expectant management following randomization. Care of the amniotic membranes for women in control groups also varied across trials. There was either an attempt to avoid amniotomy in control group women (Bréart 1992; Cammu 1996; Lopez-Zeno 1992; Nachum 2010; Rogers 1997; Sadler 2000; Serman 1995) or membranes were managed according to usual care ’no attempt to modify care from what is usually given on the service’ (Cluett 2004; Cohen 1987; Frigoletto 1995; Snehlata 2011; Somprasit 2005; Tabowei 2003). Studies varied in the degree of contrast achieved between groups with respect to the proportion undergoing the interventions (see Characteristics of included studies for details). In some trials, the proportion of women receiving oxytocin was similar in the two groups (Bréart 1992; Lopez-Zeno 1992; Rogers 1997; Serman 1995). However, in these studies, the groups contrasted in respect of the time between randomization and the initiation of oxytocin.

Excluded studies

The characteristics of the excluded studies are outlined in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. In the study by Rouse (Rouse 1994), study groups differed only with respect to the use of amniotomy. The trial by Cardozo 1990 was excluded as the groups differed only in the use of oxytocin. In Hogston 1993, the method of allocation depended on the labour ward policies of the woman’s treating physician. One study (Ruiz Ortiz 1991), was a non-randomized trial. There was no control group in two other studies (Cummiskey 1989; Xenakis 1995). Two trials were for induction labour, not augmentation (Gagnon-Gervais 2011; Selo-Ojeme 2009). Finally, in one study (Verkuyl 1986), there was no information on the inclusion or exclusion characteristics of the women.

Risk of bias in included studies

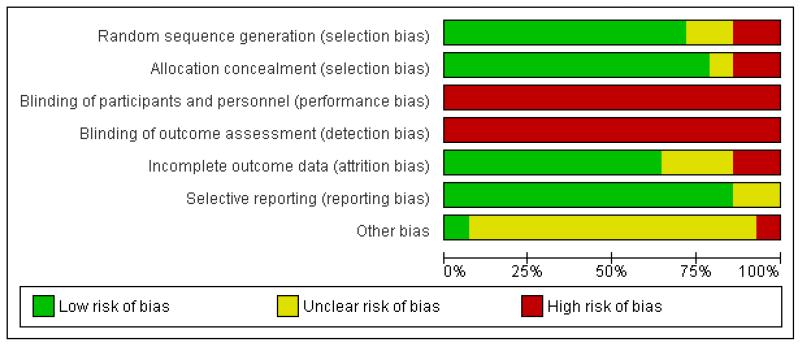

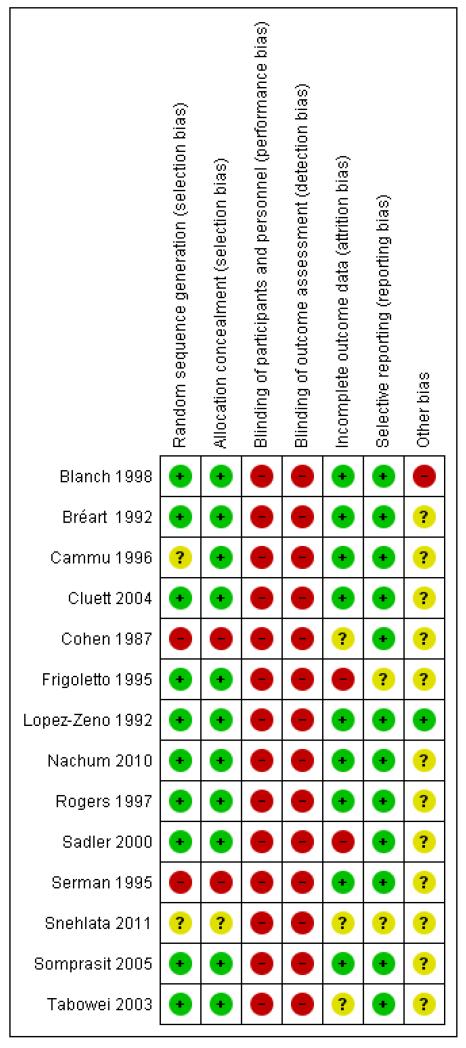

See Figure 1 and Figure 2, for summaries of all ’Risk of bias’ assessments.

Figure 1.

‘Risk of bias’ graph: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 2.

‘Risk of bias’ summary: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

We independently considered 14 trials for randomization method and attrition bias. Amniotomy is virtually impossible to mask, and oxytocin was not blinded in the trials. In one trial (Snehlata 2011), there is only abstract information available, we could not evaluate the risk of bias for allocation, outcome data, reporting and other potential sources of bias.

Allocation

In the majority of studies randomization was described as being performed using either a random number table or a computer-generated random number schedule (Blanch 1998; Bréart 1992; Cluett 2004; Frigoletto 1995; Lopez-Zeno 1992; Nachum 2010; Rogers 1997; Sadler 2000; Somprasit 2005; Tabowei 2003). In two studies the method of randomization was not reported (Cammu 1996; Snehlata 2011). In one study alternation was used (Cohen 1987) and in another study randomization was based on the last digit of the medical notes (Serman 1995). Randomization was concealed in 11 out of the 14 studies contributing data to the meta-analysis (Blanch 1998; Bréart 1992; Cammu 1996; Cluett 2004; Frigoletto 1995; Lopez-Zeno 1992; Nachum 2010; Rogers 1997; Sadler 2000; Somprasit 2005; Tabowei 2003). In one study (Serman 1995), the method of allocation was based on the woman’s medical file number (odd or even numbers). In another study (Cohen 1987), women were allocated by alternate assignment. Allocation concealment, when performed, was achieved by telephone in one trial (Frigoletto 1995), and by sealed envelopes in the remaining studies.

Blinding

Amniotomy is virtually impossible to mask, and oxytocin was not blinded in the trials. Therefore, in all the studies, the participants and clinicians were not blinded to the treatment, the risks of bias were high.

Incomplete outcome data

Most studies were at low risk of bias. In the Frigoletto 1995 trial, one-third of the women became ineligible for the study between randomization and the onset of labour because they developed medical complications or their labour was induced with oxytocin. In one trial (Sadler 2000), the overall response rate to the maternal satisfaction questionnaire was 72% (28% attrition).

Selective reporting

Most studies reported the main outcomes. In the Frigoletto 1995 trial, one-third of the women became ineligible for the study between randomization and the onset of labour, since post-randomization attrition is likely to introduce bias, we only included the CS data from this study as it was the only outcome that was reported in an intention-to-treat analysis. In one trial (Snehlata 2011), there is only abstract information available; only CS and duration of labour were available.

Other potential sources of bias

In one study (Blanch 1998), the data on the number of women eligible for the trial were not available. The trial was stopped early with only half of the women recruited due to slow recruitment rate. In the Frigoletto 1995 trial, the protocol was changed during the study.

Effects of interventions

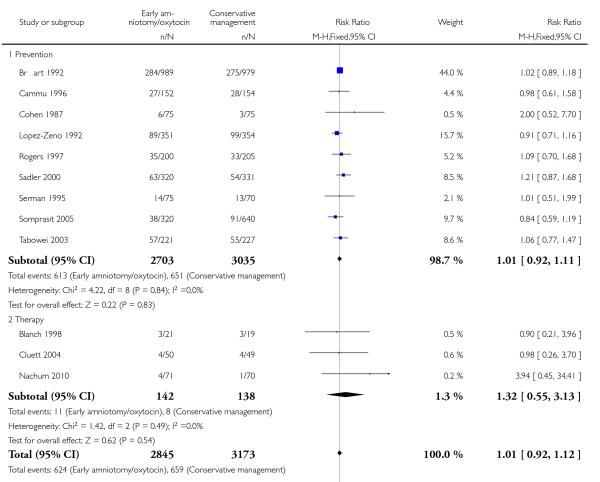

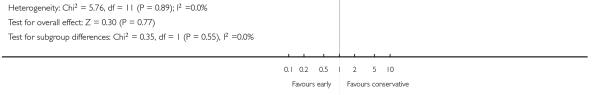

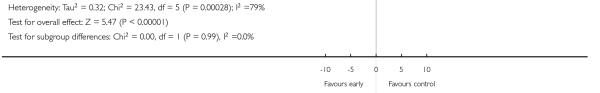

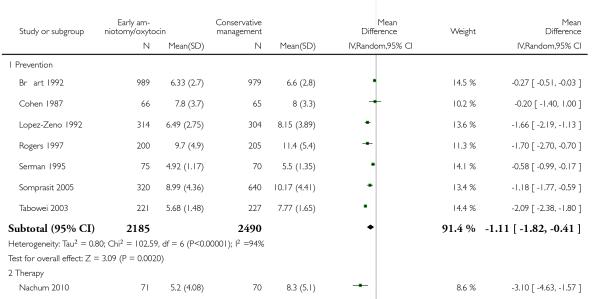

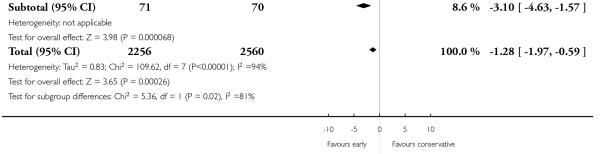

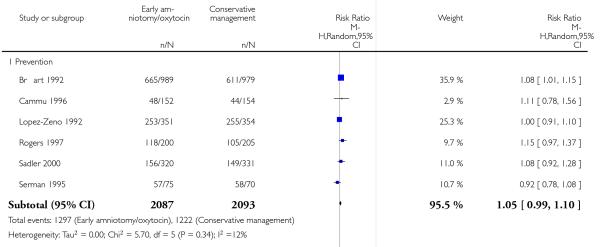

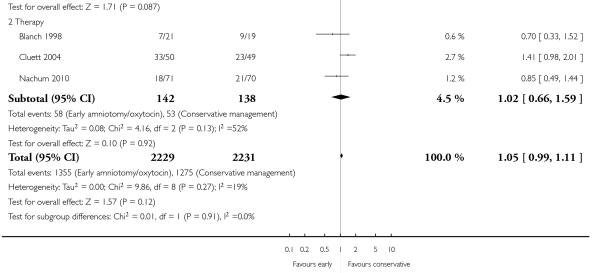

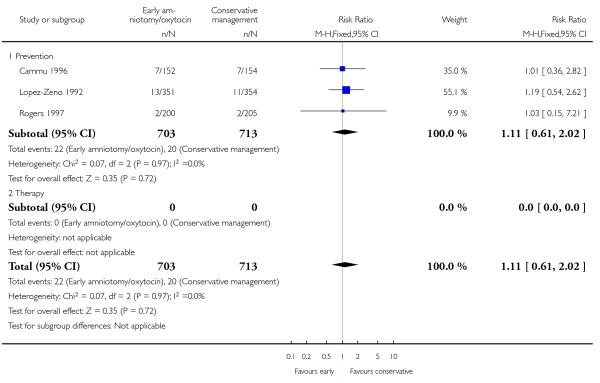

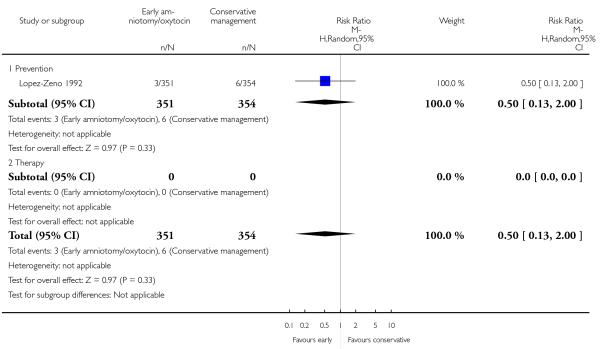

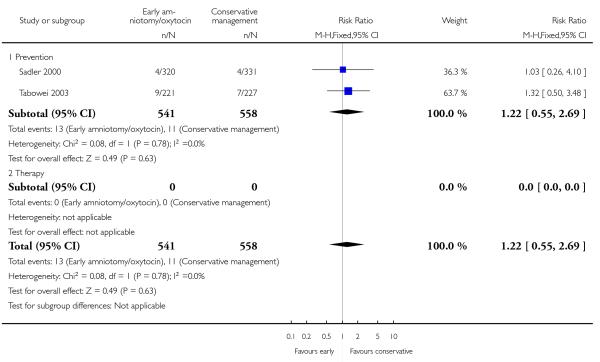

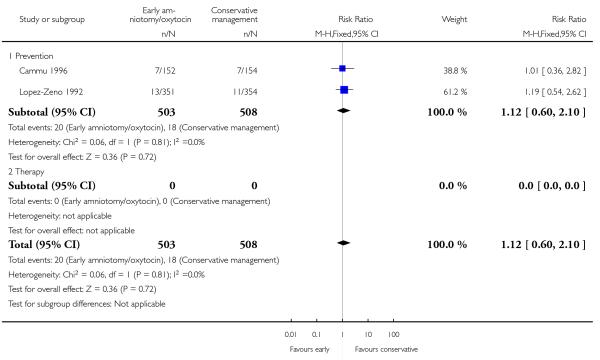

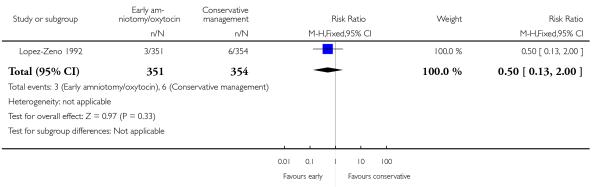

There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity for the following outcomes: the length of the first stage of labour (I2 = 79%), Analysis 1.4; the overall duration of labour (I2 = 94%), Analysis 1.5; and use of epidural analgesia in the therapy (I2 = 52%), Analysis 1.6; test for subgroup differences in postpartum haemorrhage(I2 = 49%), Analysis 1.8; maternal blood transfusion (I2 = 49%), Analysis 1.9. For the sensitivity analyses, length of first stage of labour (I2 = 75%), Analysis 2.4; duration of labour (I2 = 86%), Analysis 2.5; use of epidural analgesia in the therapy (I2 = 52%), Analysis 2.6; postpartum haemorrhage (I2 = 47%), Analysis 2.7; maternal blood transfusion (I2 = 49%), Analysis 2.8; postpartum fever or infection (I2 = 32%), Analysis 2.9; admission to special care nursery (I2 = 39%), Analysis 2.14.

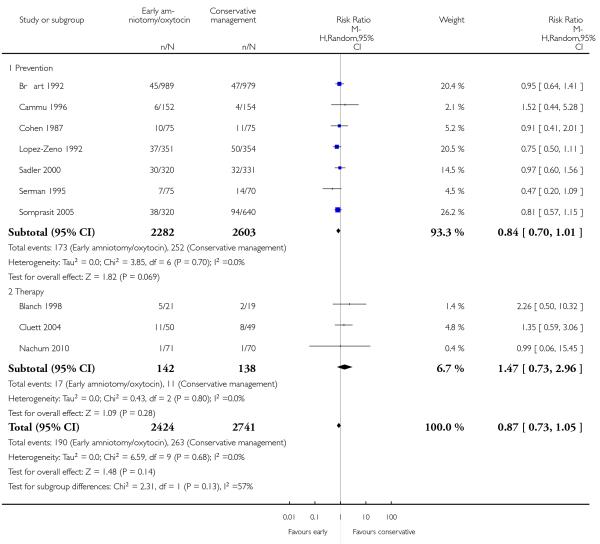

Primary outcome

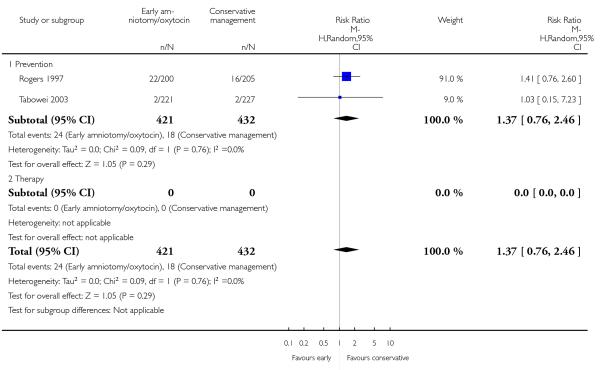

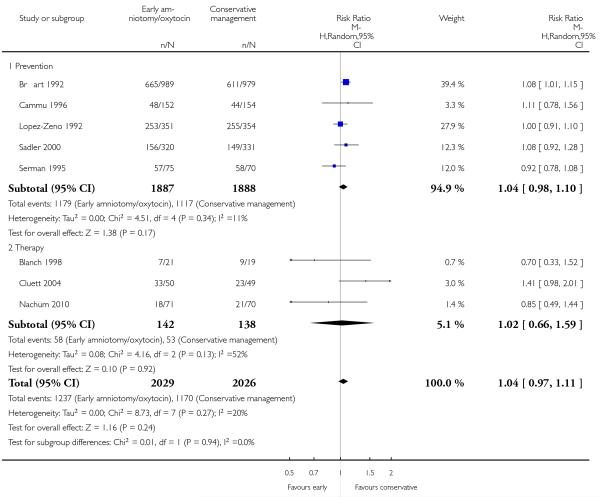

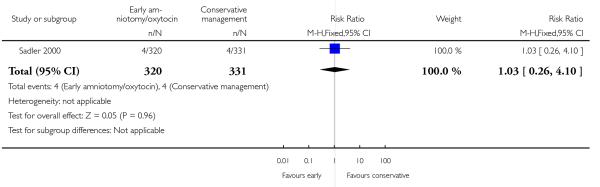

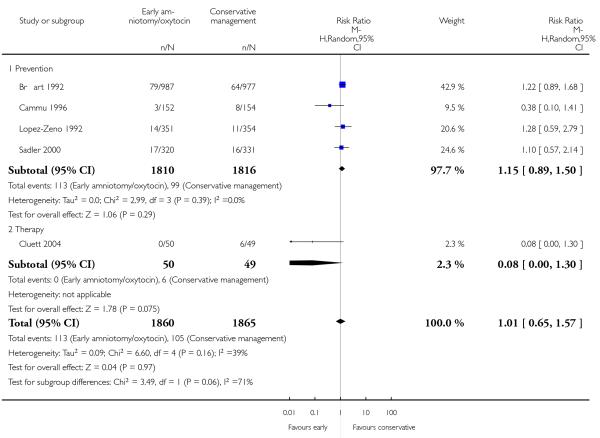

In the unstratified analysis, the point estimate for CS suggested a modest reduction with early amniotomy and oxytocin although the confidence interval (CI) included null effect (average risk ratio (RR) 0.89; 95% CI 0.79 to 1.01), Analysis 1.1. In the stratified analysis, for prevention trials early augmentation was associated with a modest reduction in the CS rate (average RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.77 to 0.99), Analysis 1.1.1. The difference in caesarean risk was 0.02. The number of women needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one CS was approximately 65. This conclusion is based on 11 randomized controlled trials involving 7653 women. In contrast, there was no statistical evidence of such an effect in therapy trials (average RR 1.47; 95% CI 0.73 to 2.96), Analysis 1.1.2. However, the number of therapy trials was small (three trials involving 280 women). An interaction test (Breslow -Day test) between prevention and therapy groups for CS, showed a Chi2 value was 2.08, P = 0.15. Thus, there was no statistical evidence of an interaction between treatment effect and trial type (prevention versus therapy); however, the statistical power of this test was low. In a sensitivity analysis, we excluded the four prevention trials where the experimental intervention consisted of the full active management pack-age. Results revealed that the effect estimate was not modified by excluding these four trials (unstratified analysis: average RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.05; prevention trials: average RR 0.84; 95% CI 0.70 to 1.01), Analysis 2.1.

Secondary outcomes

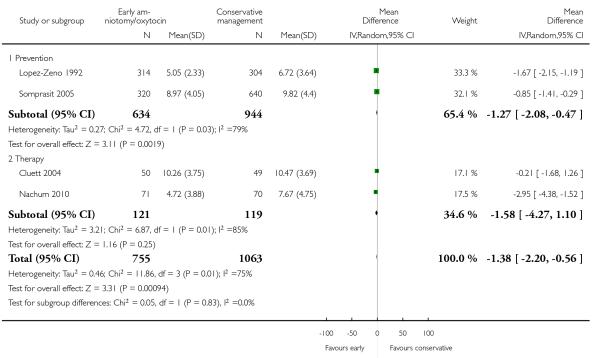

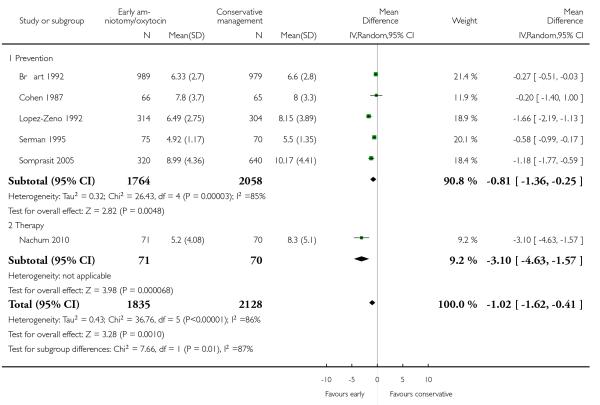

The length of first stage of labour was shortened in the early amniotomy and oxytocin group compared with the expectant management group (average mean difference (MD) −1.57 hours; 95% CI −2.14 to −1.01; random effects, T2 = 0.32, I2 = 79%), Analysis 1.4. In the stratified analysis, the effect of the study group on the duration of the first stage of labour was most marked in the prevention trials (average MD −1.57 hours; 95% CI −2.15 to −1.00; random effects, T2 = 0.26, I2 = 82%), Analysis 1.4 1. There was also statistical evidence of such an effect in the therapy trials (average MD −1.58 hours; 95% CI −4.27 to 1.10; random effects, T2 = 3.21, I2 = 85%), Analysis 1.4.2.

Eight trials reported duration of labour (admission to delivery interval) (mean±standard deviation). Overall, early amniotomy and oxytocin was associated with a reduction in the duration of labour (average MD -1.28 hours; 95% CI −1.97 to −0.59; random effects, T2 = 0.83, I2 = 94%), Analysis 1.5. However, there was significant heterogeneity across the studies, even when using standardized mean difference instead of mean difference (I2 = 94%).

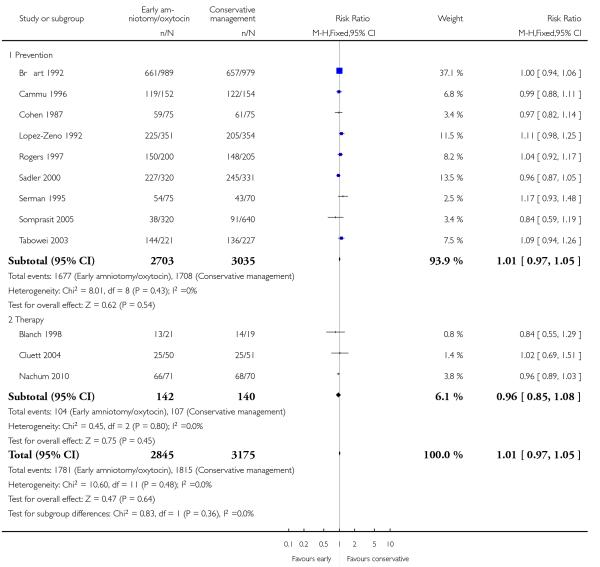

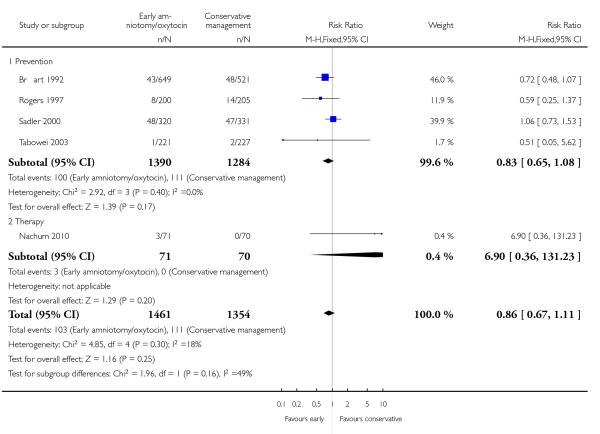

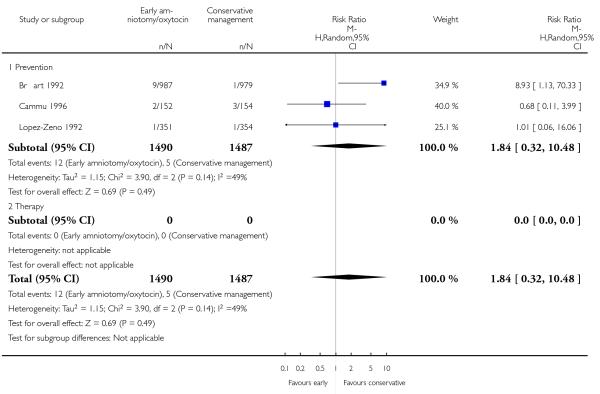

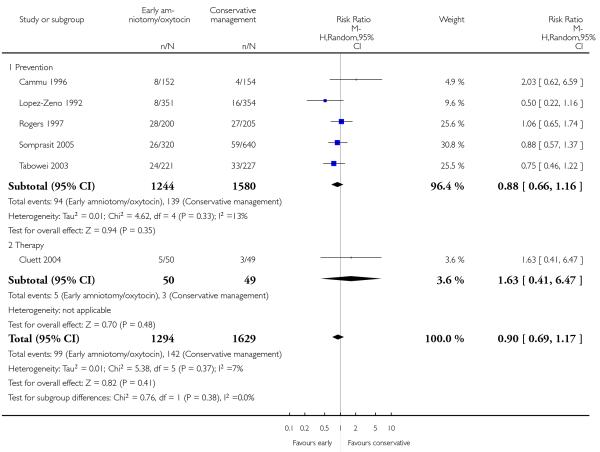

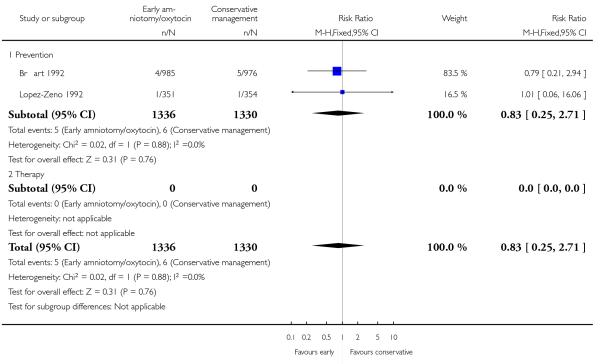

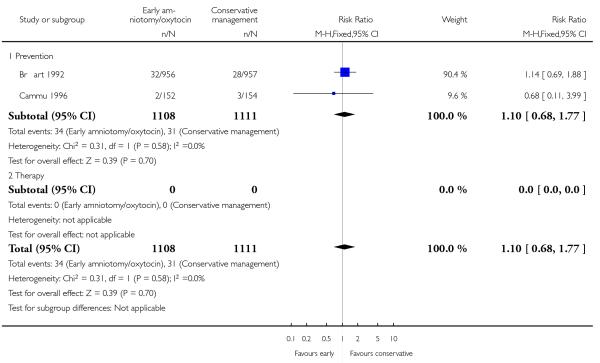

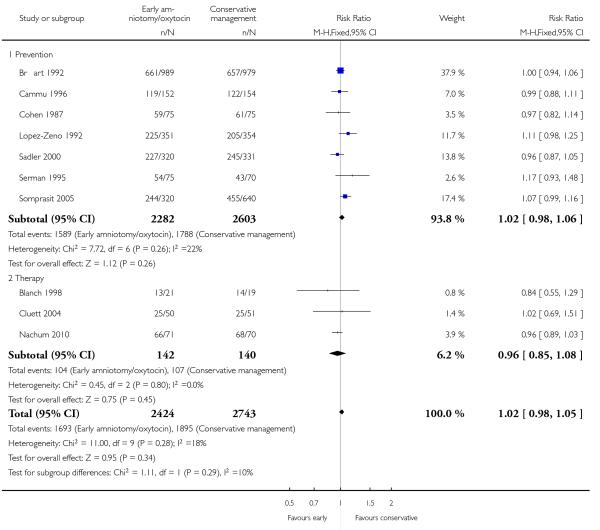

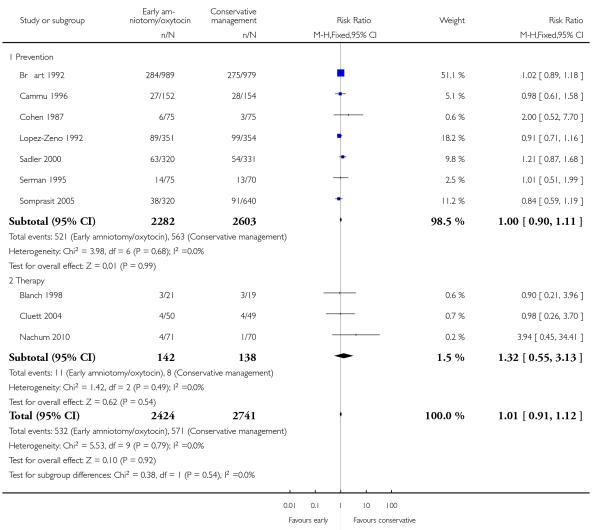

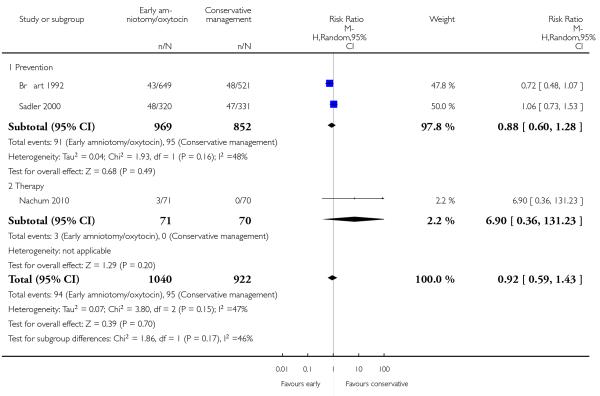

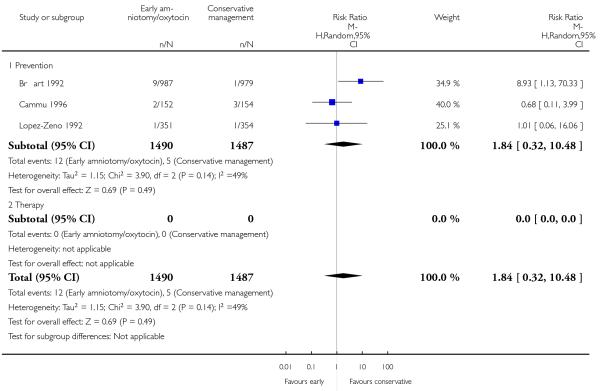

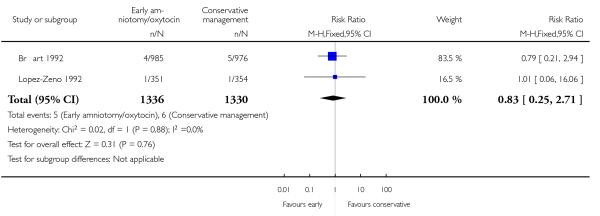

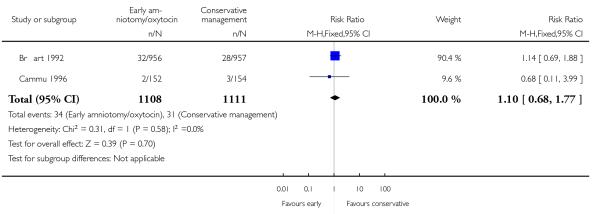

As for other maternal outcomes such as spontaneous delivery (RR 1.01; 95% CI 0.97 to 1.05), Analysis 1.2, instrumental vaginal delivery (RR 1.01; 95% CI 0.92 to 1.12), Analysis 1.3 and use of epidural analgesia (average RR 1.05; 95% CI 0.99 to 1.11), Analysis 1.6, there was no evidence of an effect on early amniotomy and oxytocin. Three trials (Bréart 1992; Cammu 1996; Lopez-Zeno 1992) reported on the frequency of requirement for maternal blood transfusion. A trend towards an increase in transfusion was noted (average RR 1.84; 95% CI 0.32 to 10.84), Analysis 1.9, in association with early intervention. This effect was mainly due to one study (Bréart 1992). There was no evidence of an effect of early intervention on a range of adverse maternal outcome indicators including hyperstimulation of labour, postpartum haemorrhage (greater than 500 ml), maternal blood transfusion, or postpartum fever or infection.

The relative risk for a number of indicators of fetal/infant morbidity and mortality (Apgar less than seven at five minutes; abnormal arterial blood cord pH (pH less than 7.10 or 7.20); suboptimal or abnormal fetal heart tracing; fetal distress; admission to special care nursery; seizure/neurological abnormalities; or jaundice or hyperbilirubinaemia) showed no evidence of differences between early amniotomy and oxytocin groups and control groups, Analysis 1.11; Analysis 1.12; Analysis 1.13; Analysis 1.14; Analysis 1.15; Analysis 1.16; Analysis 1.17.

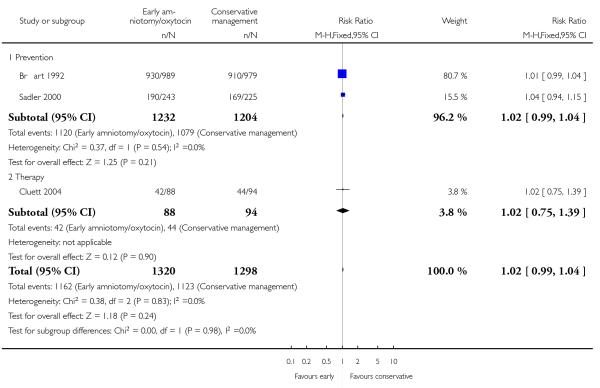

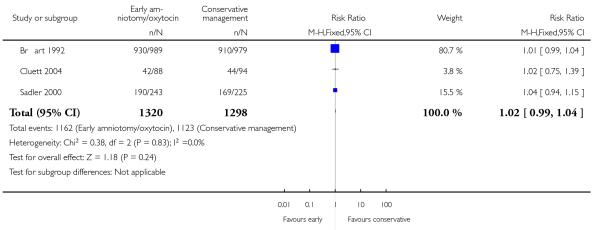

Three studies assessed the effects of the policy of early amniotomy and oxytocin on subjective indicators. Three trials (Bréart 1992; Cluett 2004; Sadler 2000) asked women about their overall satisfaction with the care they received. In one study (Bréart 1992), a majority of mothers rated their experience of delivery as satisfactory or unsatisfactory, with similar levels of satisfaction reported in both groups (RR 1.01; 95% CI 0.99 to 1.04). In another trial (Cluett 2004), the proportion of women that indicated that they were satisfied with their labour experience was similar in two groups (RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.75 to 1.39). In the trial (Sadler 2000), the proportion of women reporting that they were very satisfied was also similar in the two groups (RR 1.04; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.15). However, there was a higher proportion of non-responders in the control group. When results were summarized across trials, there was no difference between groups in the proportion who indicated that they were satisfied with their labour experience (RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.99 to 1.04), Analysis 1.18.

In the sensitivity analyses, we excluded the four prevention trials where the experimental intervention consisted of the full active management package. Results revealed that the effects estimate of the secondary outcomes were not modified, Analysis 2.2 to Analysis 2.6; Analysis 2.7 to Analysis 2.17.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this systematic review suggests that a policy of early intervention with amniotomy and oxytocin, when applied in the context of a prevention strategy for women in normal spontaneous labour with mild delays in progress, may result in a clinically modest reduction in the rate of caesarean section. A labour shortening effect was observed consistently across trials. In prevention trials, there was estimated 70-minute reduction in the duration of labour. While labour shortening could be viewed as a desirable effect, little information is available concerning women’s views on this effect. More information is required about women’s perceptions of early intervention, and the effects of early intervention on pain during labour.

A major shortcoming of several of these studies was their difficulty in obtaining a contrast between treatment groups in the interventions provided. Obstetricians who have strong beliefs about the efficacy of routine methods of care may have difficulty in attaining the equipoise that is required to achieve the desired degree of contrast in the interventions administered (Klein 1995). With respect to outcomes, when a policy designed to reduce caesarean rates is implemented for women in the experimental arm of a trial, it is likely to impact on care providers attitudes concerning the use of caesarean in the control arm. Cluster-randomized designs, where centres are allocated either to the implementation of a new policy or to usual care, could provide a partial solution to these problems. This design would permit researchers to undertake efforts to optimise compliance while minimising contamination.

Active management of labour protocol (O’Driscoll 1970) consists of an accurate diagnosis of labour, early amniotomy, frequent vaginal examinations, high dose oxytocin augmentation for slow labour progress (cervical dilatation less than 1 cm/hour), and continuous professional social support. Early amniotomy and oxytocin are two key components of active management. This meta-analysis included four trials where the experimental intervention consisted of the full package of active management of labour (Frigoletto 1995; Rogers 1997; Snehlata 2011; Tabowei 2003).

Concerning other indicators of maternal and neonatal morbidity, we found no evidence of an effect.

We wanted to assess whether the observed effect on caesarean section would be altered when we excluded studies of the active management of labour that included the full package of components making up this intervention. To this end, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding four such trials. The direction and the magnitude of the effect of the point estimates were similar, irrespective of whether these three trials were included or not.

Over the past several years, a number of randomized clinical trials have assessed the effectiveness of the components of active management, either alone or in combination. A Cochrane review assessing the effects of early amniotomy as an isolated intervention has been published (Smyth 2007). It found that amniotomy was associated with an increased risk of delivery by caesarean section compared with women in the control group, although the difference was not statistically significant. Few randomized studies have been designed to assess oxytocin as an isolated intervention (Bidgood 1987; Hinshaw 2008). We are unaware of any systematic review assessing this specific component of active management. Other aspects of active management have also been studied separately: continuous support in labour has been found to be associated with a small but statistically significant reduction in caesarean risk (Hodnett 2011). A recent Cochrane review examines the effect of active management (as a package of care) on the rate of caesarean (Brown 2008). It found that active management is associated with modest reductions in the caesarean section rate. Our review, which assessed early augmentation with amniotomy and oxytocin for women in spontaneous labour, showed that early amniotomy and oxytocin applied in the context of a prevention strategy for women in normal spontaneous labour or with mild delays in progress, may result in a clinically modest reduction in the rate of caesarean section. It is of interest that when early amniotomy is performed alone, it seems to increase the risk of caesarean. When combined with oxytocin, it appears to have a protective effect. There is a need for better information about the effect of oxytocin alone.

In 1998, we published a systematic review of the effects of early augmentation of labour in nulliparous women (Fraser 1998). The direction and magnitude of the observed effect was similar to that in the current review: a small reduction in the risk of caesarean section was observed, but the 95% confidence interval included the null effect. The current review adds several new studies which results in narrower confidence intervals and a change in the conclusion of the meta-analysis. In the stratified analysis, for prevention trials, early augmentation was associated with a modest reduction in the caesarean section rate with the 95% confidence interval excluding the null effect. We believe that the stratified results can be considered separately from the overall results, in that we planned a priori to test our hypothesis in both the prevention and treatment strata. Furthermore, the context of care is somewhat different between prevention and treatment trials.

A limitation of this review is the lack of documentation from most trials relating to other aspects of care during childbirth, such as continuous professional support, mobility and positions during labour. It was difficult to determine how these co-interventions interact with the medical components of active management (early amniotomy and oxytocin) and their impact on clinical outcomes. Also, the degree of delay, that justified the use of oxytocin, varied across trials. Additionally, the criteria of ’treatment failure’ (duration of cervical arrest following oxytocin treatment which justifies a caesarean section) were not standardized. It is highly plausible that standard diagnostic for ’treatment failure’ could contribute to reducing the caesarean section rate.

In summary, data from the meta-analysis indicate that a policy of early routine augmentation for mild delay in labour progress results in a modest reduction of caesarean section rate. The severity of delay which is sufficient to justify intervention remains to be defined.

AUTHORS ’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

These data suggest that early labour augmentation, when used in a context similar to that seen in prevention trials, results in a modest reduction in caesarean section rate in nulliparous women. These interventions are the main medical interventions included in the active management of labour: a complex protocol that traditionally included, in addition to amniotomy and oxytocin, the prospective diagnosis of labour, continuous professional social support, limited use of epidural anaesthesia, maternal ambulation in early labour, and the selective use of electronic fetal monitoring. The approach to these co-interventions are likely to impact on the overall effects of such a program. Centres that opt to implement a policy of early labour augmentation should carefully consider their policies concerning these other aspects of labour management. Given widespread concerns regarding increasing caesarean section rates, women should be informed of the possible benefits of early intervention by amniotomy and oxytocin to reduce caesarean section, and of the apparent relative safety of the procedure.

Implications for research

Further studies are required to assess the risks and benefits of active management. Standardization of diagnostic criteria regarding the degree of delay following treatment that is sufficient to justify a caesarean section needs further consideration. A period of two hours of observation after oxytocin, as reported in the Lopez-Zeno study (Lopez-Zeno 1992) may not be sufficient to judge treatment response, particularly in the low-dose oxytocin group. Limited information is available on the mothers’ views of the two approaches to treatment.

Subsequent studies should focus on the effects of early labour augmentation versus expectant management among two specific contexts of increased caesarean rate: (1) where risk status is based on an established delay in labour progress, or on other characteristics which place the women at an increased risk (cervical status at admission) (Turcot 1997); (2) where risk status is based on the practice patterns of the care providers. We suggest that a cluster-randomization design may be the best methodology to assess the benefits of early augmentation in the latter context of increased risk.

In most adequately resourced centres, oxytocin augmentation is accompanied by continuous electronic fetal monitoring. One study (Tabowei 2003), conducted in Nigeria, did not report on the approach to fetal monitoring that was used. The results of this review cannot be generalized to settings where electronic fetal monitoring is not available.

It would be important to undertake an economic analysis in order to compare costs between active management of labour versus standard treatment. Early oxytocin use without rupture of membranes should be the subject of another Cochrane review. An additional key issue is the recommendation to avoid early artifical rupture of the membranes among patients who are HIV positive in order to prevent viral transmission. This is especially important in developing countries where a high proportion of women are HIV positive.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Early amniotomy and early oxytocin for delay in first stage spontaneous labour compared with routine care

Caesarean section rates have increased substantially since the early 1970s; many women having their first babies are older and this may contribute to ineffective or difficult labour, most often because of inadequate uterine action (dystocia). The Active Management of Labour is a clinical protocol that includes early intervention with amniotomy and oxytocin to increase the frequency and intensity of uterine contractions (augmentation) when the progress of labour is delayed. Continued ineffective labour (’cervical arrest’) can result in the decision to undertake a caesarean section. Early intervention also has risks that include uterine hyperstimulation and fetal heart rate abnormalities.

This review includes 14 trials, randomizing a total of 8033 women, and showed that a policy of early routine augmentation for mild delays in labour progress resulted in a modest reduction of the caesarean section rate compared with expectant management. The reduction in caesarean sections was most evident in the 11 trials looking at prevention of abnormal progression, rather than therapy (three trials). In these women, the time from admission to giving birth was also reduced (mean difference 1.3 hours).

The trials did not provide sufficient evidence on indicators of maternal or neonatal health, including women’s satisfaction and views on the experience. Documentation of other aspects of care, such as continuous professional support, mobility and positions during labour, was limited as was the degree of contrast between groups. Women in the control group also received oxytocin but often later than in the intervention group. The severity of delay which was sufficient to justify interventions remains to be defined.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

During the study, Dr Fraser was supported by a Canada Research Chair in Perinatal Epidemiology, from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Drs Shuqin Wei and Hairong Xu are supported by a Scholarship from the CIHR Strategic Training Initiative in Research in Reproductive Health Sciences (STIRRHS). Dr Luo is supported by a Junior Scholar award from the Quebec Foundation of Health Research (FRSQ).

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

University of Montreal, Canada.

External sources

-

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Canada.

Dr Fraser is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Perinatal Epidemiology, from the CIHR.

-

CIHR Strategic Training Initiative in Research in Reproductive Health Sciences (STIRRHS), Canada.

Drs Shuqin Wei and Hairong Xu are supported by a Scholarship from the CIHR Strategic Training Initiative in Research in Reproductive Health Sciences (STIRRHS).

-

Quebec Foundation of Health Research (FRSQ), Canada.

Dr Luo is supported by a Junior Scholar award.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT. | |

| Participants | 40 women making slow progress in active phase of spontaneous labour with intact membranes (n = 21 in the amniotomy and oxytocin group, n = 19 in the control group) Inclusion criteria: cephalic presentation; gestation 37 or more weeks; full cervical effacement; cervical dilation 3 cm or more; regular uterine contractions at least every 5 minutes, lasting at least 20 seconds; no known contraindication to oxytocin; no evidence of fetal distress |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: amniotomy and oxytocin, oxytocin infusion was commenced immediately after amniotomy. The oxytocin infusion rate was doubled every 30 minutes, starting with 2 mU/minute; continuous electronic fetal monitoring was mandatory in this group Control group: expectant management, intermittent auscultation was permitted |

|

| Outcomes | Instrumental delivery; CS; cord pH; Apgar score; satisfaction score | |

| Notes | Therapy trial. Mix of primiparous and multiparous women. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random number table. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed opaque envelopes. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The participants were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The clinicians were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | There were some missing data for the outcome of cord pH (10%) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Main outcomes of interest to the review have been reported. |

| Other bias | High risk | The data on the number of women eligible for the trial were not available. The trial was stopped early with only half of the women recruited due to slow recruitment rate |

| Methods | RCT. | |

| Participants | 1968 women (n = 989 in the early rupture group and n = 979 in the control group). Inclusion criteria: primiparous women, singleton birth, spontaneous labour, vertex presentation, full term, less than full dilatation, without conditions indicating a specific policy of management of labour, informed consent |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: early amniotomy and oxytocin; use oxytocin to induce a 1 cm/per hour dilatation; amniotomy had to take place as soon as possible and before 5 cm dilatation. Control group: conservative approach, amniotomy was to be done after 5 cm dilatation |

|

| Outcomes | Mode of delivery; duration of labour; blood transfusion; Apgar scores; admission to special care unit; neurological anomalies; maternal perception; maternal characteristics; policies and type of rupture of membranes; economic consequences; jaundice; resuscitation | |

| Notes | Prevention trial. Nulliparous women. Only the data from France were included in the meta-analysis |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer-generated numbers. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The participants were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The clinicians were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | No post-randomization exclusions. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Main outcomes have been reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No information on the number of eligible women. |

| Methods | RCT. | |

| Participants | Study in a teaching hospital with mostly urban middle-class women. 306 women in spontaneous labour (n = 152 in the active management group and n = 154 in the conservative management group). Inclusion criteria: nulliparous in spontaneous labour at or over 37 weeks of gestation, with a singleton fetus in cephalic presentation with a normal admission cardiotocogram and clear amniotic fluid on admission, being 150 cm or more in height and seen at least once antenatally in the outpatient clinic |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: early amniotomy and early oxytocin; amniotomy within 1 hour after admission; oxytocin augmentation when cervical dilation was less than 1 cm/hour; Initial oxytocin infusion at 2 mU/minute. Control group: selective management; no routine amniotomy, amniotomy only after arrest of dilatation; and use of oxytocin only if delay in progress > 2 hours |

|

| Outcomes | Maternal characteristics; gestational age; cervical dilatation; intrapartum meconium; birthweight; breastfeeding; fetal scalp blood sampling; use of oxytocin and amniotomy; labour duration; instrumental and spontaneous vaginal deliveries; epidural; CS; Apgar < 7 at 5 minutes; umbilical arterial pH = < 7.1; admission to neonatal intensive care | |

| Notes | Prevention trial. Nulliparous women. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No information provided. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed opaque envelopes. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The participants were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The outcome assessors were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | 2% post-randomization exclusions. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Main outcomes have been reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No information on the number of eligible women. |

| Methods | RCT. | |

| Participants | 99 nulliparous women with dystocia (cervical dilation rate < 1 cm/hour in active labour) at low risk of complications; amniotomy and oxytocin group: n = 50; birth pool group: n = 49 | |

| Interventions | Immersion in water in birth pool or standard augmentation for dystocia (amniotomy and intravenous oxytocin) | |

| Outcomes | Epidural analgesia and operative delivery rates; augmentation rates with amniotomy and oxytocin; length of labour; maternal and neonatal morbidity including infections, maternal pain score, and maternal satisfaction with care | |

| Notes | Therapy trial. Nulliparous women. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer-generated randomization schedule in balanced block of 20 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The participants were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The clinicians were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Post-randomization exclusions in postpartum interview (4%). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Main outcomes have been reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Methods | Randomization was accomplished by alternating women to aggressive management or control groups | |

| Participants | 150 women (n = 75 in each group). Inclusion criteria: 37-42 weeks’ gestation; uterine contractions accompanied by cervical dilatation of 3 cm or ruptured membranes; less than 3 contractions lasting 40 seconds each in a 10-minute time period |

|

| Interventions | Early aggressive management: amniotomy if required, and oxytocin infusion. This was accomplished within 30 minutes of the admission. Initial oxytocin infusion rate:1 mU/ minute and increased by 1 mU/minute every 30 minutes until adequate contraction pattern was achieved. Control group: usual care. |

|

| Outcomes | Maternal characteristics; cervical dilatation; effacement %; caesarean delivery; instrumental and spontaneous vaginal deliveries; duration of labour; Apgar score at 1 and 5 minutes; cord pH; birthweight | |

| Notes | Prevention trial. Nulliparous women. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Quasi-randomization by alternating women. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | The women were allocated by alternate assignment. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The participants were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The clinicians were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | No information on numbers of postpartum women followed up. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Main outcomes reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No information on eligible women. |

| Methods | RCT (group assignments, stratified according to site). | |

| Participants | 1915 women (n = 1009 in the active management group, n = 906 in the usual care group) from 17 prenatal care sites. Inclusion criteria: nulliparous; at least 18 years old; English-speaking. Exclusion criteria: women with conditions associated with an increased risk of preterm or caesarean delivery |

|

| Interventions | Active management group: standardized criteria for the diagnosis of labour; amniotomy as soon as possible and oxytocin if cervical dilatation < 1 cm/hour. Initial oxytocin infusion rate at 4 mU/minute and increased by 4 mU/minute every 15 minutes to a maximum rate of 40 mU/minute unless uterine hyperstimulation or non-reassuring fetal heart pattern; 1-to-1 nursing care. Control group: usual care. No standardized protocol. |

|

| Outcomes | Instrumental and spontaneous vaginal deliveries; CS; epidural administration; duration of labour; cervical dilatation; complications and neonatal adverse events | |

| Notes | Prevention trial. Nulliparous women. One-third of women were post-randomization exclusions, outcome data for exclusions were only given for CS but not for the other outcomes. (Attrition rates: less than 1% for the CS outcome, 35% attrition between randomization and labour); this study has been included only for CS outcome |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random numbers in permuted blocks. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomization was through telephone calls by recruiters to the co-ordinating centre; sealed opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The participants were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Blinding ofoutcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The clinicians were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Large number of post-randomization exclusions. Outcome data for exclusions were only given for CS in intention-to-treat analysis. (Attrition rates: CS: less than 1%; the other outcomes: 35%.) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Only CS reported for whole randomized sample. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Changed protocol during study. |

| Methods | RCT was based on a permuted-blocks design. | |

| Participants | 705 women (n = 351 in the active management group, n = 354 in the traditional management group). Inclusion criteria: nulliparous women in spontaneous labour after 37 weeks of gestation. Exclusion criteria: multiple gestation; non-cephalic presentation; previous uterine surgery; if amniotomy was performed or augmentation of labour with oxytocin was begun before labour diagnosis |

|

| Interventions | Active management group: amniotomy within 1 hour of the diagnosis of labour; oxytocin if rate of cervical dilatation < 1 cm/hour. Initial oxytocin infusion rate was 6mU/minute and increased by 6 mU/minute every 15 minutes until reaching 7 contractions per 15 minute or until maximum rate of 36 mU/minute. Traditional management group: care was left up to attending obstetrician, if cervical dilation was less than 1 cm per hour, oxytocin use at a lower dose |

|

| Outcomes | CS; instrumental and spontaneous vaginal deliveries; length of first and second stage of labour; epidural; maternal and neonatal morbidities | |

| Notes | Prevention trial. Nulliparous women. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomized assignment based on a permuted-block design. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The participants were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The clinicians were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Post-randomization exclusion was 2%. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Main outcomes reported. |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

| Methods | RCT. | |

| Participants | 141 women (n = 71 in the active labour management group, n = 70 in the traditional labour management (controls) group) Inclusion criteria: gestational age of 37 weeks or more, with intact amniotic membranes and a singleton fetus in cephalic presentation, a spontaneous onset of labour, a cervical dilatation between 2 and 4 cm, vertex level of no more than 2 cm above the pelvic inlet, a prolonged latent phase of labour Exclusion criteria: a previous uterine scar, rupture of membranes, placental abruption, severe pre-eclampsia, suspected fetal macrosomia (greater than 4000 g), a non-reassuring fetal heart rate tracing or any contraindication for a trial of labour |

|

| Interventions | Active management group: oxytocin administration was one mU/min increased by 1 mU/min every 20 minutes until 5 concontractions in 10 minutes or cervical progress was documented Traditional management group: without intervention. |

|

| Outcomes | CS, instrumental and spontaneous vaginal delivery, length of first stage of labour; duration of labour; postpartum hemorrhage; postpartum fever | |

| Notes | Therapy trial. Mix of primiparity and multiparity. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer-generated random numbers. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The participants were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The clinicians were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | No post-randomization exclusion. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Primary outcomes reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No evidence of other biases. |

| Methods | RCT. | |

| Participants | 405 women (n = 200 for active management, n = 205 for usual care control protocol). Inclusion criteria: gestational age at or more than 37 weeks; low risk; term; nulliparous; cephalic presentation; no known maternal medical complications or fetal anomalies. Exclusion criteria: placenta praevia; abruptio placenta; twin gestation; prior uterine surgery; or any other obstetric or any medical complication of pregnancy |

|

| Interventions | Active management group: strict diagnosis of labour, amniotomy was performed within 2 hours of admission, and augmentation of labour with oxytocin was initiated if cervical dilatation of 1 cm/hour in the first stage of labour or descent of 1 cm/hour in the second stage failed to occur. Initial oxytocin infusion rate at 6 mU/minute and increased every 15 minutes Control group: usual care; oxytocin if progression in labour was not made, defined as cervical change of 1.25 cm/hour once the women was in the active phase of labour. Initial oxytocin infusion rate at 1 mU/minute and increased by 1 mU/minute every 30 to 40 minutes |

|

| Outcomes | Maternal characteristics; cervical dilatation; thick meconium; internal fetal monitors; epidural; length of labour; instrumental and spontaneous vaginal deliveries; CS; Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes; cord pH <7.1; admission to neonatal intensive care unit | |

| Notes | Prevention trial. Nulliparous women. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer-generated random numbers. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed, opaque envelopes. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The participants were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The clinicians were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Low numbers of post-randomization exclusions (0.5% attrition) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No information on the number of the eligible women. |

| Methods | RCT. | |

| Participants | 651 women (n = 320 in the active management group, n = 331 in the routine care group) Inclusion criteria: nulliparity; singleton pregnancy; cephalic presentation; spontaneous labour. Exclusion criteria: non-cephalic presentation; uterine scar; severe cardiac disease; contracted pelvis; gestation < 37 completed weeks; fetal distress on admission to the labour ward; elective CS; intrauterine death; multiparity |

|

| Interventions | Active management group: early amniotomy at diagnosis of labour,and early use of high-dose oxytocin for slow progress (less than 1 cm/hour cervical dilatation) in labour. Initial oxytocin infusion rate was 6 mU/minute and increased by 6 mU/minute every 15 minutes to a maximum rate of 36 mU/minute. Routine care: usual care. Initial oxytocin infusion rate was1 mU/minute and doubled the rate every 10 minutes to 8 mU/minutes, then increased by 2 mU/minutes to a maximum rate of 40 mU/minutes |

|

| Outcomes | CS; operative vaginal delivery; fetal distress; maternal and neonatal complications; duration of labour; maternal satisfaction with care | |

| Notes | Prevention trial. Nulliparity. Some aspects of the active management protocol were not respected in 127 (40%) women. The majority of these related to failure to initiate or follow the high-dose oxytocin augmentation protocol. A meta-analysis is included in the article | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer-generated random numbers. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The participants were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The clinicians were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Postpartum (breastfeeding and maternal satisfaction) attrition rates were 24% in the intervention group, and control group attrition rates were 32% (overall attrition rates were 28%) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Main outcomes reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No information for the eligible women. Postpartum data were missing |

| Methods | Randomization was based on the woman’s medical file number (odd or even numbers) | |

| Participants | 145 women (n = 75 in the active labour management group, n = 70 in the traditional labour management (controls) group) | |

| Interventions | Active management group: amniotomy was performed and oxytocin given as soon as cervical dilatation was less than 1 cm/hour for the first 3 hours of labour. Traditional management group: routine care. Initial oxytocin infusion rate in both groups: 5 mU/minute and increased every 15 minutes up to a maximum rate of40 mU/minute. It was decreased if signs of fetal distress or uterine contractions < 2 minutes apart were present |

|

| Outcomes | Mode of delivery; epidural; Apgar < = 6 at 1 minute and 5 minutes; length of labour; meconium; neonatal and maternal morbidity | |

| Notes | Prevention trial. Nulliparous women. Article written in Spanish. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Last digit hospital record number. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | The method of allocation was based on the woman’s medical file number (odd or even numbers) |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The participants were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The clinicians were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | No post-randomization exclusions. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Main outcomes reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | No information on the number of eligible women. |

| Methods | RCT. | |

| Participants | 100 primigravidas at term were randomly assigned to 2 groups:active management (n = 50) and control group (n = 50) | |

| Interventions | Women in the intervention group were managed by early amniotomy and augmentation with oxytocin at 6 miu/mL. In the control group, women received conservative care, amniotomy after 6 cm dilatation and oxytocin at 1 miu/mL | |

| Outcomes | CS; length of labour; maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality | |

| Notes | Prevention trial. Nulliparous women. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only abstract information available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only abstract information available. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The participants were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The clinicians were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Only abstract information available. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Only abstract information available. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Only abstract information available. |

| Methods | RCT. | |

| Participants | 960 women in Thailand. Inclusion criteria: nulliparous women at or more than 37 weeks’ gestation; spontaneous labour; cephalic presentation; single fetus without fetal distress Exclusion criteria: thick meconium-stained amniotic fluid at admission; contraindications to vaginal delivery or oxytocin augmentation; medical or surgical complications |

|

| Interventions | Active management group: early amniotomy within 1 hour of admission, and high doses of oxytocin if cervical dilatation was less than 1 cm/hour in the first stage of labour. Initial oxytocin infusion rate was 6 mU/minute and increased by 2 mU/minute every 30 minutes to a maximum rate of 40 mU/minute. Routine care: usual care, no standard protocol, there was variation among obstetricians |

|

| Outcomes | CS; duration of labour; maternal complications and neonatal outcomes | |

| Notes | Prevention trial. Nulliparous women. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random number table. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | It was impossible to blind the treatment (active management of labour) to patients |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The clinician was not blinded to the treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Some post-randomization exclusions (1.5%), but analysis by intention-to-treat |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Reported on main outcomes. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | The management of the comparison group was not clearly described |

| Methods | RCT. | |

| Participants | 448 women in Nigeria. Inclusion criteria: nulliparous women in spontaneous labour, single fetus with cephalic presentation at term Exclusion criteria: contraindications to vaginal delivery or oxytocin augmentation, pregnancy or medical complications |

|

| Interventions | Active management group: early amniotomy was performed when labour was diagnosed, high doses of oxytocin if cervical dilatation was less than 1 cm/hour in the first stage of labour or descent was not demonstrated for 1 hour or more in second stage. Initial oxytocin infusion rate was 6mU/minute and increased by 6 mU/minute every 15 minutes to a maximum rate of 36 mU/minutes, separate labour room cared for by a nurse-midwife. Routine care: usual care, no standard protocol, there was variation among obstetricians |

|

| Outcomes | Mode of delivery; duration of labour; maternal complications and neonatal outcomes | |

| Notes | Prevention trial. Nulliparous women. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer-generated random schedule. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Opaque, sealed envelopes. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The participants were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The clinicians were not blinded to the treatment. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Some post-randomization exclusions (11.7%). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Main outcomes were reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Number of women eligible for recruitment were not shown. |

CS: caesarean section

RCT: randomized controlled trial

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Cardozo 1990 | The trial was oxytocin only. |

| Cummiskey 1989 | Data compare 2 methods of administration of the same medication. Women were randomized to the pulsatile-infusion group and the continuous-infusion group. No control group |

| Gagnon-Gervais 2011 | It is for induction labour, not augmentation. |

| Hogston 1993 | No randomization. Treatment depending on labour ward of the treating consultant |

| Rouse 1994 | 2 groups; 1 group was oxytocin and amniotomy, the other was oxytocin. There was no control group |

| Ruiz Ortiz 1991 | Method of distribution between experimental group and control group are not mentioned. No randomization |

| Selo-Ojeme 2009 | It is for induction labour, not augmentation. |

| Verkuyl 1986 | No information on inclusion or exclusion criteria. |

| Xenakis 1995 | Low-dose versus high-dose oxytocin augmentation of labour. No control group. |

DATA AND ANALYSES

Comparison 1. Early amniotomy and early oxytocin versus routine care on spontaneous labour.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Caesarean section rate | 14 | 8033 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.79, 1.01] |

| 1.1 Prevention | 11 | 7753 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.77, 0.99] |

| 1.2 Therapy | 3 | 280 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.47 [0.73, 2.96] |

| 2 Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 12 | 6020 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.97, 1.05] |