Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy of an intervention designed to promote resilience in young children living with their HIV-positive mothers.

Design/Methods

HIV-positive women attending clinics in Tshwane, South Africa and their children, aged 6 - 10 years, were randomised to the intervention (I) or standard care (S). The intervention consisted of 24 weekly group sessions led by community care workers. Mothers and children were in separate groups for 14 sessions, followed by 10 interactive sessions. The primary focus was on parent-child communication and parenting. Assessments were completed by mothers and children at baseline and 6, 12 and 18 months. Repeated mixed linear analyses were used to assess change over time.

Results

Of 390 mother-child pairs, 84.6% (I:161 & S:169) completed at least two interviews and were included in the analyses. Children's mean age was 8.4 years and 42% of mothers had been ill in the prior three months. Attendance in groups was variable: only 45.7% attended >16 sessions. Intervention mothers reported significant improvements in children's externalizing behaviors (β=-2.8, P=0.002), communication (β=4.3, P=0.025) and daily living skills (β=5.9, P=0.024), while improvement in internalizing behaviors and socialization was not significant (P=0.061 and 0.052 respectively). Intervention children reported a temporary increase in anxiety but did not report differences in depression or emotional intelligence.

Conclusions

This is the first study demonstrating benefits of an intervention designed to promote resilience among young children of HIV-positive mothers. The intervention was specifically designed for an African context, and has the potential to benefit large numbers of children, if it can be widely implemented

Keywords: Vulnerable children, maternal HIV, resilience, child behavior, adaptive functioning, parenting, latency-age children

Introduction

The scope of the AIDS epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa and its devastating effects on families has potentially serious implications for a growing generation of children. Approximately 17 million children have already been orphaned by the disease,[1] but now, with increased access to antiretroviral medications, millions more children are being raised by parents living with HIV. In 2012, 61% of all persons eligible for HIV treatment (based on the 2010 World Health Organization guidelines) were receiving treatment, almost doubling the number receiving treatment just three years earlier.[1] In South Africa, antenatal surveys indicate that as many as one-third of women aged 25 to 39 are HIV positive,[2] an age at which these women may already be mothers of young children.

Reports examining the psychological and behavioral effects of parental HIV infection have primarily focused on children orphaned by the disease, but there is now an extensive literature suggesting that children living with their HIV-infected parents – those often referred to as vulnerable children – also experience a psychological burden.[3-5] Most studies have examined adolescents, but there are a few studies, conducted in Europe [6] and the U.S.[7-10] that have demonstrated increased depressive symptoms and behavior problems among young vulnerable children – those in middle childhood, between the ages of six and ten years. Despite the fact that young children are seldom told their parents' HIV status,[11,12] they may still suffer as a result of the psychological effects of HIV on their parents.[13-16] There is also evidence that young children are most affected when their parents are symptomatic,[9,17,18] which can contribute to compromised parenting, resulting in children's behavioral difficulties and poor functioning.[8,19-22]

There has been a sustained call for interventions to address the psychological needs of HIV-affected children [23-24] and many diverse programs do exist. There is, however, a dearth of empirical evidence establishing the success of interventions, whether they are community-based programs [25] or those providing family-centered, psychosocial support.[26-28] A systematic review by Betancourt et al. in 2012 [28] identified four intervention studies designed to promote resilience in HIV-affected children. Two focused on adolescents in the U.S. [29] and France [30] and the third was a school-based intervention for orphans aged 10-15 years in Uganda.[31] The fourth study, considered most rigorous in its design, demonstrated the efficacy of a support group intervention for adolescents in New York [32] with some positive effects persisting for as long as six years.[33,34] To date, however, there have been no studies that have examined whether younger children of HIV-infected mothers – those in middle childhood– might benefit from resilience-promoting interventions. Compared to interventions for adolescents, an intervention for young children requires a greater focus on the parent-child dyad and attention to issues of parenting.

The purpose of this study was to assess the efficacy of an intervention designed to promote resilience among young children living with their HIV-positive mothers. Resilience is defined as the capacity for successful adaptation despite challenging circumstances [9,35-38]. It is generally not measured as a single construct, and in this study was operationalized as a decrease in problem behaviors and improved adaptive and psychological functioning in the context of maternal HIV infection.

The intervention was provided in a structured group setting for both the mothers and their children and was specifically developed for use in an African setting through action research that involved focus groups with HIV positive mothers in South Africa, and piloting and refinement of the intervention following this formative evaluation.[39] The conceptual framework has been described previously [39] and is based on the understanding that the psychological trauma experienced by mothers dealing with HIV,[13-16] and the resulting compromised parenting contributes to children's behavioral difficulties and poor functioning.[8,19-22] Thus the intervention was designed not only to improve the wellbeing of the mother and child but also the interaction between them. The intervention was also informed by literature on resilience theory [36-38] and similar programmes for older children.[40] Promotion of resilience involves addressing personal characteristics such as increasing self-esteem as well as enhancing contextual variables such as family relationships.

Methods

The study was conducted in two separate communities within Tshwane (formerly Pretoria), South Africa and was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Pretoria and Yale University School of Medicine.

Enrollment

HIV positive women attending clinics in each of the communities were referred to the study by clinic staff and invited to participate. All women provided written consent and verbal assent was obtained from the children. Participants were eligible for the study if they were able to communicate in at least one of five local languages (Sepedi, Setswana, Sesotho, isiZulu or English) and the children were aged six to ten years and lived with their mothers at least five days per week. If there was more than one child in the family within the age range, the oldest child was selected. To decrease the potentially confounding effect of other persons being ill, families were excluded if the child or others living in the household were known to be HIV positive or were reported as having a life-threatening illness. After completing baseline interviews conducted by trained research assistants, mother-child pairs were randomized to either the intervention (“I”) or standard care (“S”) conditions at each of the two study sites separately, using a block randomization process and table of random numbers with 30 subjects in each block. Subjects randomized to the standard care condition were provided with information about local resources available for assistance.

Description of the intervention

The intervention groups were conducted over 24 weekly sessions, each lasting 75 minutes. For the first 14 sessions, mothers and children participated in separate groups occurring concurrently and thereafter they participated together in ten interactive sessions (see Table 1). The mother and child groups were each facilitated by two community care workers. These were individuals who exhibited good interpersonal skills and had at least 12 years of education. They were trained within the project and supervised by a social worker. The training included information about HIV and AIDS and skills for facilitating groups, counseling, and identification and management of children's emotional and behavioral problems. A manual identified specific objectives for each session and provided an outline for experiential learning activities such as games, group discussions and behavioural modelling.

Table 1. Summary of sessions provided in the intervention.

| Separate sessions 1-14 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mothers | Children | |

| Week 1 | Introduction, orientation and relationships of trust | Introduction and getting to know each other. ‘Let's get to know one another’ |

| Week 2 | Living positively “How do I look after myself?” (Basic HIV&AIDS info) | Developing relationships within the group ‘Let's get to know one another’ |

| Week 3 | Disclosure | Describe self and self in family ‘Who am I?’ |

| Week 4 | HIV and relationships | Describe self and family within community ‘My community’ |

| Week 5 | The emotional experience of having HIV (Part 1), ‘How do I feel?’ | Identify strengths within self ‘What do I look like? I have, I am, I can!’ |

| Week 6 | The emotional experience of having HIV (Part 2), ‘How do I feel?’ | Identifying coping that is linked to strengths identified ‘What can I do/ What am I good at?’ |

| Week 7 | Coping, problem solving and stress management | Problem solving ‘How can I do it?’ |

| Week 8 | HIV in the household, human rights and stigma | Protecting self and identifying boundaries ‘Protecting myself’ |

| Week 9 | Parenting skills (Part 1), ‘Knowing and understanding myself as a parent’ | Social skills ‘Socializing with peers’ |

| Week 10 | Parenting skills (Part 2), ‘Knowing and understanding myself as a parent’ | Identifying emotions (focus on self) ‘How do I feel?’ |

| Week 11 | Development of children (Part 1), ‘Knowing and understanding my child’ | Identifying emotions (focus on other and communication skills) |

| Week 12 | Development of children (Part 2), ‘Knowing and understanding my child’ | Survival skills (Part 1), ‘Look and learn’ |

| Week 13 | My child and HIV | Survival skills (Part 2), ‘Look and learn’ |

| Week 14 | Life planning and goal setting | Identifying meaning, purpose and future orientations ‘Let's live life’ |

| Joint sessions 15-24 | ||

| Week 15 | Mother and child getting to know each other (Part 1) ‘Knowing me, knowing you’ | |

| Week 16 | Mother and child getting to know each other (Part 2) ‘Knowing me, knowing you’ | |

| Week 17 | Mother and child getting to know each other (Part 3) ‘Knowing me, knowing you’ | |

| Week 18 | Creating a legacy. (Part 1), ‘Let's make a family memory’ | |

| Week 19 | Creating a legacy. (Part 2), ‘Let's make a family memory’ | |

| Week 20 | Interaction between mother and child (Part 1), ‘Let's have fun’ | |

| Week 21 | Interaction between mother and child (Part 2), ‘Let's have fun’ | |

| Week 22 | Mother and child sessions revisited (Separate session), ‘Where are we at now?’ | |

| Week 23 | Planning for the future. ‘Let's dream together’ | |

| Week 24 | Family celebration. ‘Let's celebrate life’ | |

The first seven sessions focused on the mothers' issues relating to living with HIV; these were followed by sessions addressing parenting. The children's sessions focused on building self-esteem and enhancing interpersonal and practical life skills. Activities included board games, story telling and traditional cultural games. The final ten joint sessions were designed to promote healthy parent-child interaction and modelling of positive parenting behaviours and included activities such as compiling a family legacy box. The focus was on overarching skills rather than HIV-specific themes.

The study included 12 groups, with approximately 15 participants in each group. Participants were reimbursed for travel expenses and meals were provided. Following each session, the community care workers completed quality assurance questionnaires that were used to ensure fidelity to the intervention.

Assessment and measures

Interviews were conducted at baseline and follow-up at 6, 12 and 18 months in research offices located within each of the two communities. Participants were reimbursed for travel expenses. Because the instruments used had originally been developed in English and validated in western populations, cultural modifications were made through consultation with local personnel, before translating, back translating and piloting with 22 HIV positive mothers. The modifications were minor and included such things as substituting words that might not be clearly understood with more colloquial words and changing a reference to a toy that was likely not familiar to the children with another more commonly available toy.

Maternal illness and HIV status disclosure

Mothers were considered ill if, in the prior three months, they reported any non-specific symptoms (unintentional weight loss > 5 kg or fatigue that interfered with daily activities for more than two weeks) or they had an HIV-related illness that satisfied WHO clinical staging 3 or 4.[41] Mothers were asked whether the participating children had been told their HIV status.

Maternal assessment

The reliability of all scales was examined using the data collected at baseline.

Maternal psychological characteristics

Maternal depression was measured with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression Scale (CES-D) (α = 0.87).[42] As done in earlier studies, five items that assess somatic symptoms were excluded as these symptoms could be attributed to HIV disease, giving a range of scores of 0-45.[43] Maternal coping was assessed using The Brief COPE.[44] In this study, a factor analysis of the baseline data identified three different coping styles, which were labeled “self coping” (range 12-48, α=0.70), “seeking help from others” (range 9-36, α=0.71) and “avoidant coping” (range 7-28, α=0.71). The internal consistency of the three coping domains are within the range obtained by Carver for the individual scales in the development of the Brief COPE, [44] and the reliability of the CES-D is similar to that found in other studies [45-46].

Maternal parenting characteristics

Parenting stress was assessed using two subscales of the Parenting Stress Index (PSI): Parenting Distress (range 11-55, α=0.82) and Parent-Child Dysfunction (range 12-60, α=0.82).[47] Mothers' responses to their children's negative behaviors were assessed using the Coping with Children's Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES).[48] This scale assesses maternal responses to distressing situations for their children. Three parenting behaviors (emotion-focused, problem-focused, and expressive encouragement) were combined to form a measure of positive parenting (range 27-162, α=0.79) and two parenting behaviors (distress and punitive reaction) were combined to form a negative parenting domain (range 18–36, α=0.67).

Child assessment

Parent-reported measures

Parental perception of children's behavior was assessed using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) which provides two subscales: Internalizing (range 0-64, α=0.85) and Externalizing behaviors (range 0-64,α=0.92).[49] Children's adaptive functioning was measured using the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS) which assesses the parent's perception of a child's functioning across three domains: communication, daily living skills, and socialization (range 20-160 for each).[50]

Child-reported measures

Depressive symptoms among children were assessed using the Child Depression Inventory (CDI)(range 0-42, α=0.68).[51] Children's anxiety was measured using the Revised Child Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS)(range 0-28, α=0.82).[52] The BarOn EQ-i: Youth Version (range 24-96, α=0.80) assesses emotional intelligence, which comprises abilities related to understanding oneself and others and managing one's emotions.[53] The RCMAS is intended for use for children as young as six years, whereas the CDI and Bar-On are intended for children age seven and older. While the study included children younger than seven at enrollment, all children were at least seven years old by the 12-month follow-up evaluation.

Statistical analyses

Potential differences in the baseline socio-demographic characteristics of mothers and children randomized to the two conditions were examined using Chi-square test and student t-test, with the Mann Whitney U test being used when data were not normally distributed. The efficacy of the intervention was examined using Repeated Mixed Linear Analysis, which assesses change over multiple time points, while taking into account within-subject dependence and allowing for missing data points.[54-56] Variables that were significantly different between the two conditions (I and S) at baseline were included in all models and the baseline value for each outcome was entered as a covariate into the specific model for the outcome.[57] The interviews were treated as a continuous variable, thus as a covariate. No random effects were specified and the covariance structure found to be the most suitable in all analyses was that of compound symmetry.[56]

Further analyses were performed to examine whether there might be interaction effects, with certain groups responding differently to the intervention. Three-way interactions were created between specific variables (i.e. gender, age of child and maternal illness), condition and interview. In these analyses the order of the interview (baseline, 1, 2 or 3) was treated as a categorical variable in order to make interpretation of the interactions easier.[56]

Results

A total of 390 mother-child pairs completed the enrollment process and were randomized to one of the two conditions. The socio-demographic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 2. Forty-two percent of the women reported having had an illness in the prior six months. Approximately one-quarter of the women were pregnant. Significantly fewer mothers in the intervention condition were employed. The women had known of their HIV status for a mean of 24.3 months, with 30.6% having known for less than six months. The children randomized to the intervention condition were significantly younger than those in the standard care condition. Only 7% of the children had been told of their mother's HIV status.

Table 2. Characteristics of intervention and standard care conditions at baseline.

| Characteristic | Intervention (N = 199) |

Standard Care (N = 191) |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal socio-demographic characteristics | ||

|

| ||

| Mean age (S.D.) | 33.1 (5.9) | 33.1 (6.0) |

|

| ||

| Marital status, %: | ||

| Married | 19 % | 17 % |

| Single with partner | 48 % | 55 % |

| Single, no partner | 28 % | 22 % |

| Widowed | 5 % | 6 % |

|

| ||

| Education, % | ||

| Primary | 12 % | 14 % |

| Secondary | 86 % | 83 % |

| Tertiary | 2 % | 3 % |

|

| ||

| Employed % | 23 % | 34 % * |

|

| ||

| Mean housing score (S.D.) | 3.6 (1.7) | 3.6 (1.7) |

|

| ||

| Mean persons in household (S.D.) | 6.5 (2.7) | 6.2 (3.0) |

|

| ||

| Maternal health | ||

|

| ||

| Months since HIV diagnosis (S.D.) | 22.2 (27.6) | 26.6 (31.1) |

|

| ||

| HIV-related illness in prior 3 months, | ||

| None or mild | 62 % | 53 % |

| Moderate or severe | 38 % | 47 % |

|

| ||

| Mean CD4 (S.D.) | 288 (224) | 312 (221) |

|

| ||

| Presently pregnant, % | 21 % | 28 % |

|

| ||

| Child characteristics | ||

|

| ||

| Gender: Male, % | 54 % | 52 % |

|

| ||

| Mean Age (S.D.) | 8.22 (1.51) | 8.51 (1.46) * |

|

| ||

| Mean number of siblings (S.D.) | 2.3 (1.1) | 2.1 (1.2) |

|

| ||

| Stays overnight with someone else at least once per week | 15 % | 12 % |

|

| ||

| Disclosure of mother's status | ||

| No disclosure | 86 % | 90 % |

| Told health problem or something wrong | 6 % | 3 % |

| HIV disclosed | 8 % | 7 % |

Difference between groups at P<0.05

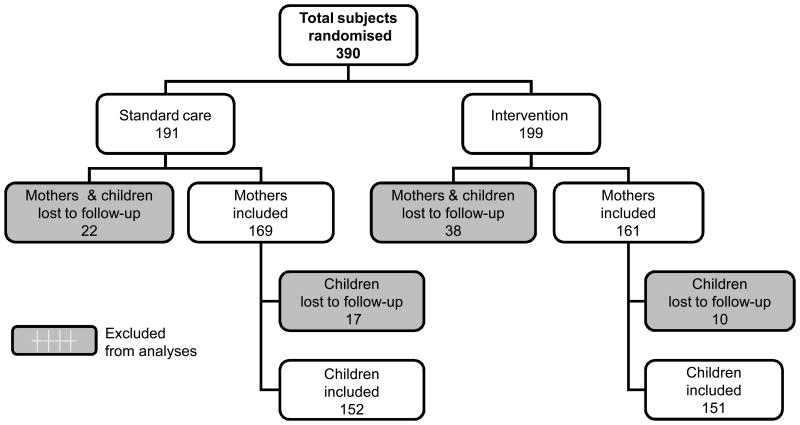

As seen in Figure 1, 161 (81%) mothers in the intervention condition and 169 (88%) mothers in the standard care condition completed at least one follow-up interview and were included in the analysis. Women lost to follow-up were less likely to be living with a partner (29% versus 50%, P=0.03) and had known of their HIV status for a shorter period of time (median 9 versus 13 months, P=0.013). The proportions completing the 6, 12 and 18-month follow-up interviews were 73.9%, 73.7% and 74.7% respectively with no significant differences in attendance between the two study conditions. Of those included in the analyses, 72% of the women and 63% of the children completed all three follow-up interviews. Twenty women are known to have died during the period of follow-up, 10 in each condition.

Figure 1. Subject participation.

Attendance at support group sessions for those in the intervention condition

Intervention exposure varied: nearly half (45.7%) of the mothers attended >16 sessions, 25.8% attended 9-16 session, 14.6% <9 sessions, and 13.9% failed to attend any sessions. Attendance was relatively constant over time, however, with a mean of eight women attending each session. In 62% of instances the reason for not attending is unknown, but when information was available, the reasons given were: obtained employment (14%); lack of interest (10%); death (8%); relocation out of area (4%) and illness (2%).

Efficacy of the intervention

The efficacy of the intervention was examined with inclusion of all subjects for whom there were follow-up data. The two variables that were significantly different between the two conditions -- maternal employment and child age -- were included in the analyses.

Maternal Psychological and Parenting Characteristics

As illustrated in Table 3, there were no significant effects of the intervention on any of the maternal psychological or parenting measures. While there were substantial improvements in depression over time, this was true for mothers in both conditions and the difference between conditions was not significant (β = -1.07, P=0.092). In further analyses to assess whether higher attendance at group sessions increased the effectiveness of the intervention, the number of sessions attended was entered into the model as a continuous variable with those randomized to the standard care condition receiving a value of zero. These analyses demonstrated that increased attendance in the intervention was significantly associated with decreased maternal depression (β = -0.096, P=0.047) and an increase in the coping domain of seeking help from others (β = 0.047, P=0.032). Subsequent analyses did not demonstrate any threshold effect.

Table 3. Baseline and estimated mean scores at follow-up for intervention (I) and standard care (S) conditions.

| Variable | Estimated Mean Value (Standard Error) | Overall effect: Estimated β | Overall P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Maternal Psychological Measures | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Depression (CES-D) | I | 16.51 (.74) | 12.07 (.92) | 10.79 (.91) | 10.43 (.89) | - 1.07 | 0.092 |

| S | 15.87 (.76) | 13.77 (.85) | 12.35 (.85) | 11.50 (.86) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Coping (Brief-Cope) | |||||||

| Self coping | I | 40.96 (.42) | 41.72 (.47) | 41.39 (.46) | 42.20 (.45) | 0.05 | 0.94 |

| S | 40.21 (.46) | 41.43 (.44) | 41.82 (.43) | 42.16 (.44) | |||

| Help from others | I | 25.57 (.48) | 27.73 (.44) | 27.68 (.44) | 28.49 (.43) | 0.32 | 0.21 |

| S | 24.50 (.44) | 26.51 (.41) | 27.75 (.41) | 28.17 (.42) | |||

| Avoidant coping | I | 14.21 (.38) | 13.55 (.44) | 13.60 (.44) | 13.02 (.43) | - 0.24 | 0.99 |

| S | 13.88 (.39) | 13.91 (.41) | 13.02 (.41) | 13.26 (.41) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Parenting | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Parenting Stress Index (PSI) | |||||||

| Parental distress | I | 30.71 (.67) | 29.48 (.77) | 28.77 (.76) | 26.98 (.75) | - 2.15 | 0.41 |

| S | 30.31 (.64) | 29.76 (.72) | 28.09 (.71) | 29.13 (.72) | |||

| Parent-child dysfunction | I | 25.69 (.61) | 26.02 (.67) | 25.54 (.66) | 25.64 (.65) | - 0.20 | 0.89 |

| S | 25.51 (.61) | 26.07 (.62) | 25.57 (.62) | 25.83 (.63) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Coping with Children's | |||||||

| Negative Emotions (CCNES) | |||||||

| Positive responses | I | 119.8 (1.2) | 116.9 (1.3) | 121.6 (1.3) | 118.3 (1.3) | - 1.10 | 0.84 |

| S | 119.8 (1.1) | 119.4 (1.3) | 118.7 (1.2) | 119.4 (1.3) | |||

| Negative responses | I | 78.7 (0.8) | 78.7 (0.9) | 80.7 (0.9) | 78.5 (0.9) | - 0.86 | 0.98 |

| S | 79.2 (0.8) | 79.7 (0.9) | 78.9 (0.9) | 79.4 (0.9) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Child Outcomes | |||||||

| Parent-reported measures | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Behavior Problems (CBCL) | |||||||

| Externalizing behaviors | I | 13.29 (.79) | 11.16 (.79) | 10.91 (.78) | 9.06 (.76) | - 2.81 | 0.002 |

| S | 13.73 (.88) | 13.48 (.73) | 13.32 (.73) | 11.87 (.74) | |||

| Internalizing behaviors | I | 11.73 (.59) | 9.75 (.60) | 10.24 (.60) | 8.85 (.58) | - 1.43 | 0.061 |

| S | 12.05 (.67) | 11.56 (.56) | 10.43 (.56) | 10.28 (.57) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Adaptive Functioning (VABS) | |||||||

| Communication | I | 95.7 (1.5) | 102.0 (1.4) | 100.7 (1.4) | 104.1 (1.4) | 4.26 | 0.025 |

| S | 95.0 (1.4) | 97.9 (1.3) | 100.9 (1.3) | 99.9 (1.3) | |||

| Daily living skills | I | 93.8 (1.4) | 100.0 (1.7) | 101.6 (1.6) | 107.7 (1.7) | 5.86 | 0.024 |

| S | 95.4 (1.3) | 96.6 (1.5) | 100.2 (1.5) | 101.8 (1.6) | |||

| Socialization | I | 109.0 (1.3) | 117.2 (1.6) | 115.7 (1.6) | 11.7.4 (1.6) | 1.53 | 0.052 |

| S | 110.3 (1.4) | 111.8 (1.4) | 114.9 (1.6) | 115.9 (1.5) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Child-reported measures | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Depression (CDI) | I | 7.41 (.36) | 7.71 (.44) | 6.70 (.44) | 5.81 (.42) | - 0.67 | 0.88 |

| S | 7.52 (.35) | 6.91 (.41) | 6.65 (.43) | 6.49 (.42) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Anxiety (RCMAS) | I | 8.85 (.38) | 9.60 (.45) | 8.36 (.45) | 8.01 (.43) | 0.50 | 0.044 |

| S | 9.33 (.39) | 8.01 (.42) | 7.73 (.43) | 7.50 (.43) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Emotional Intelligence | I | 59.6 (0.7) | 59.5 (0.9) | 59.6 (0.9) | 61.0 (0.8) | 0.61 | 0.63 |

| (Bar-On) | S | 58.6 (0.7) | 60.1 (0.8) | 60.8 (0.8) | 60.3 (0.8) | ||

Child Psychological and Behavioral Functioning

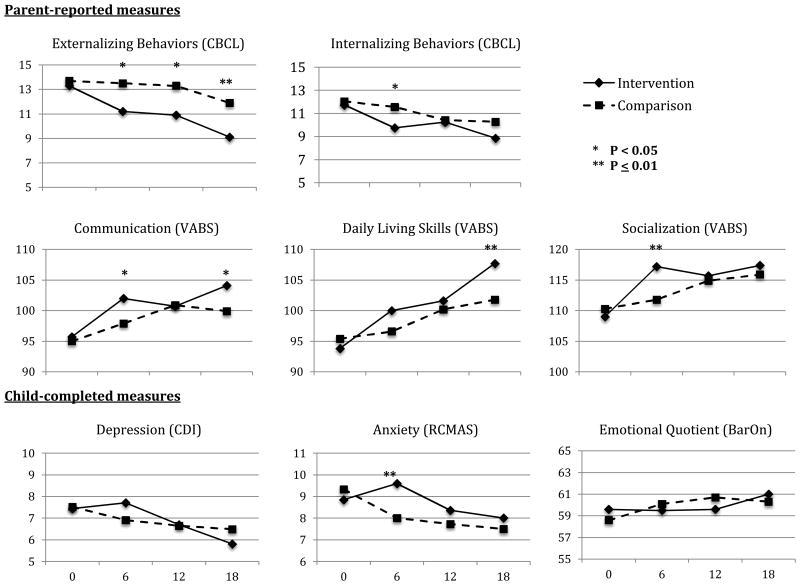

Child outcomes based on mother's reporting showed significant improvements. Externalizing behaviors improved significantly for those in the intervention condition (β = -2.81, P = 0.002), while improvement in internalizing behaviors was more modest (β = -1.43, P = 0.061). The intervention also resulted in significant improvements in two of the adaptive functioning domains assessed by the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales: communication (β = 4.26, P = 0.025) and daily living skills (β = 5.86, P = 0.024) but improvement in the socialization domain was not significant approached significance (β = 0.53, P = 0.052). There were no significant differences between conditions in the child-reported measures except for anxiety, which increased for those randomized to the intervention groups (β = 0.50, P = 0.044). The analyses were repeated excluding subjects who were younger than seven years at the time of enrollment, but this produced little change in the results (not shown). Similarly, analyses conducted to assess the potential effect of increased attendance at groups showed little change in child outcomes.

As seen in Figure 2, the results provide some evidence of sustainability of effect over time for some of the children's outcomes. Externalizing behaviors continued to decrease for the children in the intervention condition after the six-month intervention resulting in an even greater difference between conditions at 18 months (P < 0.001). The responses in communication and daily living skills were slightly different; for both of these the intervention children showed significantly greater improvement during the six-month intervention period but differences between groups were not sustained at 12 months. Subsequently at 18 months the intervention group again had significantly higher scores. For both internalizing behaviors and socialization the intervention appeared to have an immediate effect but differences were not sustained post-intervention. Similarly, the increased anxiety experienced by those in the intervention condition did not persist.

Figure 2. Child outcomes for intervention and comparison conditions.

Potential interactions

Three variables were examined to determine whether certain characteristics might have affected intervention outcomes; these included maternal illness and the gender and ages of the children (< 8 years versus ≥ 8 years). Maternal illness affected mother's coping responses but did not affect any other outcomes: mothers who had been ill and were assigned to the intervention condition had a decrease in avoidant coping over the period of follow-up while this increased among those in the standard care condition and remained relatively unchanged in both groups for those women who had not experienced illness (P<0.001). Boys tended to gain greater benefit from the intervention than did girls. There was a significant three-way interaction between gender, condition and follow-up for externalizing behaviors (P=0.035), internalizing behaviors (P=0.05) and depression (P=0.038), with improvement occurring among the boys assigned to the intervention, while scores for boys in the standard care condition tended to remain stable. Girls tended to improve over time whether or not they were in the intervention or standard care condition. There was no effect of children's ages on outcomes and no interaction effects on the other outcomes assessed.

By 18 months rates of maternal HIV-status disclosure had increased but remained low in both conditions (Intervention: 16.7%, Standard care: 13.8%), making it impossible to assess the potential effect of disclosure on child outcomes.

Discussion

This is the first study to provide empirical evidence of the benefits of a parent-child group intervention for young children living with their HIV-infected mothers. Other programs that have been shown to be beneficial have focused on children in different circumstances including a school-based intervention for older children (10-15 years) who were orphaned;[31] and an intervention for adolescents in the United States, who were all aware that their mothers were HIV-positive.[32] In contrast, the objective of the present study was to promote resilience in children at a younger age through strengthening the parent-child dyad.

The primary effect of the intervention was on decreasing children's externalizing behavior problems and increasing children's adaptive functioning, particularly in the areas of communication and daily living skills. Prior studies attempting to assess resilience in children have specifically focused on such areas of behavior and adaptive functioning.[9,19,58] Importantly, the beneficial effects persisted at least 12 months beyond the period of the intervention suggesting that the intervention potentially has a long-lasting effect on children's resilience.

The children in the intervention condition reported greater anxiety at the end of the intervention and the boys reported a significant decrease in depression, but there were no other differences in the child-reported measures. The fact that children attending the intervention had increased anxiety suggests the intervention included anxiety-provoking content despite the fact that HIV was not mentioned. This increase in anxiety was temporary, however, and happened concurrently with reported improvements in behavior and functioning, suggesting it likely had little adverse effect on the children.

It does appear that the intervention had a greater beneficial effect for boys than it did for girls. These differences were limited to the children's behavior and measure of depression and not to their adaptive functioning and are likely related to differences between the genders in their expression of distress. For practical reasons, however, these differences have little relevance as the intervention was shown to have an effect on the two genders combined and it would be very unlikely that in the future the intervention would be offered to families with boys and not to those with girls.

It remains unknown why findings on the child-reported measures were not more robust, when improvements were evident on the mother-reported measures. Such discrepancies have been found in other studies of young children[59] and in this instance could be explained by a reporting bias among the intervention mothers. If this were the case, however, one might expect greater consistency across time intervals. For example, it is particularly notable that intervention mothers reported significant improvements in children's adaptive functioning at 6 and 18 months but not at 12 months. It is also possible that the instruments used with the children were not sufficiently reliable in this sample of children. The instruments have not been validated in the South African context and despite our best efforts at cultural adaptation and translation, difficulties with nuances pertaining to emotion-focused concepts continued to exist. For example, items such as “Nothing bothers me” in the BarOn EQ-i and “Nothing is fun at all” in the CDI are not easily translated and may be considered differently by children in different cultures.

Children whose mothers had been ill might be expected to have greater benefit from the intervention, as these children are more likely to suffer psychologically.[9,17,18] There was, however, no direct evidence of increased benefit for these children although the intervention did result in decreasing avoidant coping among their mothers. In a prior analysis of the baseline data collected in this study,[60] avoidant coping by mothers was shown to have a direct effect on increasing children's externalizing and internalizing behaviors and both avoidant coping and maternal illness had indirect effects on children's adaptive functioning by increasing parenting stress. Thus, the finding in this study that the intervention decreased avoidant coping among the mothers who had been ill suggests this likely contributed to the improvements in child behavior and adaptive functioning among the children.

Study limitations

Study limitations include varied intervention exposure. The intervention was lengthy, however, and evening complete attendance may have contributed to the effects observed. Poor attendance is a known difficulty with group-based interventions with disadvantaged populations.[61,62] The finding that increased attendance was associated with a decrease in maternal depression and an increase in coping through seeking help from others suggests that mothers who did attend more frequently experienced more personal psychological improvement. A further limitation was the lack of follow-up data for some subjects. The data analysis, however, allowed for missing data. There was only a relatively small number of subjects (15.4%) for whom there were no follow-up data, thus these likely had only a limited effect on the results obtained.

The results demonstrated no change in the mothers' parenting behaviors, despite the fact that the intervention model was specifically designed to address parenting. This finding is surprising, particularly because the previously reported analyses of the baseline data suggested that parenting has an important mediating effect on child outcomes.[60] The fact that there were improvements in child behavior and adaptive functioning without measureable improvements in parenting, suggest there are potentially other mediating variables that were not measured or that the instruments used did not appropriately assess the relevant changes in parent-child interactions.

Conclusions

The demonstration of the efficacy of this intervention in an African setting has important implications for addressing the psychological consequences of parental HIV infection on young children. The success attained in decreasing AIDS-related mortality has not negated the need to address the epidemic's effects on very large numbers of children. This intervention was designed for use in a resource-poor area and because it is manual guided and provided by trained, lay facilitators, it offers real promise for wider implementation. Future research is needed to examine whether the increased resiliency and improved functioning demonstrated over the 18-month follow-up period will persist into adolescence and adulthood. Recognizing the limitations on resources, it would also be important to provide greater understanding of what components of the intervention were most effective and whether a shortened intervention might produce similar results.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant Number: 5R01MH076442)

References

- 1.UNAIDS. World AIDS Day Report. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Republic of South Africa. Global AIDS Response Progress Report. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cluver L, Gardner F. The mental health of children orphaned by AIDS: a review of international and southern African research. J Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2007;19(1):1–17. doi: 10.2989/17280580709486631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandt R. Maternal well-being, childcare and child adjustment in the context of HIV/AIDS: What does the psychological literature say? Centre for Social Science Research: University of Cape Town. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chi P, Li X. Impact of parental HIV/AIDS on children's psychological well-being: a systematic review of the global literature. AIDS Behav. 2012;17(7):2554–2574. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0290-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esposito S, Musetti L, Musetti MC, Tornaghi R, Corbella S, Massironi E, et al. Behavioral and psychological disorders in uninfected children aged 6 to 11 years born to human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive mothers. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1999;20(6):411–417. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199912000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forehand R, Steele R, Armistead L, Morse E, Simon P, Clark L. The Family Health Project: psychosocial adjustment of children whose mothers are HIV infected. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(3):513–520. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forehand R, Jones DJ, Kotchick BA, Armistead L, Morse E, Morse PS, et al. Noninfected children of HIV-infected mothers: A 4-year longitudinal study of child psychosocial adjustment and parenting. Behav Ther. 2002;33(4):579–600. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy DA, Marelich WD. Resiliency in young children whose mothers are living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2008;20(3):284–291. doi: 10.1080/09540120701660312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauman LJ, Camacho S, Silver EJ, Hudis J, Draimin B. Behavioral problems in school-aged children of mothers with HIV/AIDS. Clin Child Psychol Psych. 2002;7(1):39–54. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nostlinger C, Bartoli G, Gordillo V, Roberfroid D, Colebunders R. Children and adolescents living with HIV positive parents: emotional and behavioural problems. Vulerable Children and Youth Studies. 2006;1(1):29–43. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palin FL, Armistead L, Clayton A, Ketchen B, Lindner G, Kokot-Louw P, et al. Disclosure of maternal HIV-infection in South Africa: description and relationship to child functioning. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1241–1252. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9447-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lightfoot M, Shen H. Levels of emotional distress among parents living with AIDS and their adolescent children. AIDS Behav. 1999;3:367–372. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrison MF, Petitto JM, Ten Have T, Gettes DR, Chiappini MS, Weber AL, et al. Depression and anxiety disorders in women with HIV infection. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):789–796. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherr L, Clucas C, Harding R, Sibley E, Catalan J. HIV and depression--a systematic review of interventions. Psychol Health Med. 2011;16(5):493–527. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.579990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner GJ, Goggin K, Remien RH, Rosen MI, Simoni J, Bangsberg DR, et al. A closer look at depression and its relationship to HIV antiretroviral adherence. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42(3):352–360. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9295-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy DA, Marelich WD, Hoffman D. A Longitudinal Study of the Impact on Young Children of Maternal HIV Serostatus Disclosure. Clin Child Psychol Psych. 2002;7(1):55–70. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy DA, Marelich WD, Herbeck DM. Impact of Maternal HIV Health: A 12-year study of children in the Parents and Children Coping Together Project. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(4):313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dutra R, Forehand R, Armistead L, Brody G, Morse E, Morse PS, et al. Child resiliency in inner-city families affected by HIV: the role of family variables. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38(5):471–486. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hough ES, Brumitt G, Templin T, Saltz E, Mood D. A model of mother-child coping and adjustment to HIV. Soc Sci Med Feb. 2003;56(3):643–655. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy DA, Marelich WD, Herbeck DM, Payne DL. Family routines and parental monitoring as protective factors among early and middle adolescents affected by maternal HIV/AIDS. Child Dev. 2009;80(6):1676–1691. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy DA, Marelich WD, Armistead L, Herbeck DM, Payne DL. Anxiety/stress among mothers living with HIV: effects on parenting skills and child outcomes. AIDS Care. 2010;22(12):1449–1458. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.487085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richter LM, Sherr L, Adato M, Belsey M, Chandan U, Desmond C, et al. Strengthening families to support children affected by HIV and AIDS. AIDS Care. 2009;21(sup1):3–12. doi: 10.1080/09540120902923121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandan U, Richter L. Strengthening families through early intervention in high HIV prevalence countries. AIDS Care. 2009;21(sup1):76–82. doi: 10.1080/09540120902923097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schenk KD. Community interventions providing care and support to orphans and vulnerable children: a review of evaluation evidence. AIDS Care. 2009;21(7):918–942. doi: 10.1080/09540120802537831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Quality Assurance Project, USAID; Health Care Improvement Project, UNICEF. The Evidence Base for Programming for Children Affected by HIV/AIDS in Low Prevalence and Concentrated Epidemic Countries. [Accessed 5th December, 2013];2008 http://www.unicef.org/aids/files/OVC_final.pdf.

- 27.King E, deSilva M, Stein A, Patel V. Interventions for improving the psychosocial well-being of children affected by HIV and AIDS. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006733.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Betancourt TS, Meyers-Ohki SE, Charrow A, Hansen N. Research Review: Mental health and resilience in HIV/AIDS-affected children: a review of the literature and recommendations for future research. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(4):423–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyon M, Garvie P, Kao E, Briggs L, He J, Malow R, et al. Spirituality in HIV-infected adolescents and their families: Family centered (FACE) advance care planning and medication adherence. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48:633–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Funck-Brentano I, Dalban C, Veber F, Quartier P, Hefez S, Costagliola D, et al. Evaluation of a peer support group therapy for HIV-infected adolescents. AIDS. 2005;19(14):1501–1508. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000183124.86335.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumakech E, Cantor-Graae E, Maling S, Bajunirwe F. Peer-group support intervention improves the psychosocial well-being of AIDS orphans: cluster randomized trial. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(6):1038–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rotheram-Borus M, Lee M, Gwadz M, Draimin B. An intervention for parents with AIDS and their adolescent children. Amer J Pub Health. 2001;91(8):1294–1302. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rotheram-Borus M, Lee M, Lin Y, Lester P. Six-year intervention outcomes for adolescent children of parents with the human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:742–748. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rotheram-Borus M, Stein J, Lester P. Adolescent adjustment over six years in HIV-affected families. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luthar SS. Annotation: methodological and conceptual issues in research on childhood resilience. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1993;34(4):441–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01030.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garmezy N. Vulnerability and Resilience. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity. Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. British J Psychiatry. 1985;147:598–611. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masten AS, Best KM, Garmezy N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:425–444. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Visser M, Finestone M, Sikkema K, Boeving-Allen A, Ferreira R, Eloff I, et al. Development and piloting of a mother and child intervention to promote resilience in young children of HIV-infected mothers in South Africa. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2012;35:491–500. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mallman SA. Program of the Catholic AIDS Action. Namibia: Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman; 2003. Building resilience in children affected by HIV/AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- 41.WHO. WHO case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunological classification of HIV-related diseases in adults and children. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M. Distinguishing between overlapping somatic symptoms of depression and HIV disease in people living with HIV-AIDS. J Nerv Mental Dis. 2000;188:662–670. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200010000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4(1):92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bird ST, Bogart LM, Delahanty DL. Health-related correlates of perceived discrimination in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2004;18(1):19–26. doi: 10.1089/108729104322740884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simoni JM, Ng MT. Trauma, coping and depression among women with HIV/AIDS in New York City. AIDS Care. 2000;12(5):567–580. doi: 10.1080/095401200750003752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abidin R. Parenting Stress Index: Professional Manual. 3rd. New York: Psychological Resources, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fabes RA, Poulin RE, Eisenberg GN, Madden-Derdich DA. The Coping with Children's Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES): Psychometric Properties and relations with children's emotional competence. New York: Harworth Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Achenbach T. Integrative Guide to the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR and TRF Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychology; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sparrow S, Cicchetti D, Balla D. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. 2nd. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson, Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kovacs MK. Children's Depression Inventory (CDI) New York: Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reynolds CR, R B. Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale. Vol. 2. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bar-On R, Parker J. EQ-i: YV BarOn Emotional Quotient Inventory Youth Version. North Tonawanda, New York, USA, Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Second. Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chan YHC. Biostatistics 301A. Repeated measurement analysis (mixed models) Singapore Med J. 2004;45:456–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Norusis M. SPSS 14.0 Advanced Statistical Procedures Companion. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cnaan A, L N, Slasor P. Using the general linear mixed model to analyse unbalanced measures and longitudinal data. Statist Med. 1997;16:2349–2380. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19971030)16:20<2349::aid-sim667>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gordon Rouse KA, Ingersoll GM, Orr DP. Longitudinal health endangering behavior risk among resilient and nonresilient early adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1998;23(5):297–302. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shaffer A, Jones DJ, Kotchick BA, R F. Telling the children: Disclosure of maternal HIV infection and its effects on child psychosocial adjustment. J Child Family Studies. 2001;10(3):301–313. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boeving-Allen A, Finestone M, Eloff I, Sipsma H, Mkin J, Triplett K, Ebersöhn L, Sikkema K, Briggs-Gowan M, Visser M, Ferreira R, Forsyth BWC. The role of parenting in affecting the behavior and adaptive functioning of young children of HIV-infected mothers in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0544-7. Online First. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mundell JP, Visser MJ, Makin JD, et al. The impact of structured support groups for pregnant South African women recently diagnosed HIV positive. Women & Health. 2011;51(6):546–565. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2011.606356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mendez JL, Carpenter JL, LaForett DR, Cohen JS. Parental engagement and barriers to participation in a community-based preventive intervention. Amer J Comm Psychol. 2009;44(1-2):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]