Abstract

Background

Codeine is an opioid metabolised to active analgesic compounds, including morphine. It is widely available by prescription, and combination drugs including low doses of codeine are commonly available without prescription.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy, the time to onset of analgesia, the time to use of rescue medication and any associated adverse events of single dose oral codeine in acute postoperative pain.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and PubMed to November 2009.

Selection criteria

Single oral dose, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials of codeine for relief of established moderate to severe postoperative pain in adults.

Data collection and analysis

Studies were assessed for methodological quality and data independently extracted by two review authors. Summed total pain relief (TOTPAR) or pain intensity difference (SPID) over 4 to 6 hours were used to calculate the number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief, which were used to calculate, with 95% confidence intervals, the relative benefit compared to placebo, and the number needed to treat (NNT) for one participant to experience at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours. Numbers using rescue medication over specified time periods, and time to use of rescue medication, were sought as additional measures of efficacy. Data on adverse events and withdrawals were collected.

Main results

Thirty‐five studies were included (1223 participants received codeine 60 mg, 27 codeine 90 mg, and 1252 placebo). Combining all types of surgery (33 studies, 2411 participants), codeine 60 mg had an NNT of at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours of 12 (8.4 to 18) compared with placebo. At least 50% pain relief was achieved by 26% on codeine 60 mg and 17% on placebo.

Following dental surgery the NNT was 21 (12 to 96) (15 studies, 1146 participants), and following other types of surgery the NNT was 6.8 (4.6 to 13) (18 studies, 1265 participants). The NNT to prevent use of rescue medication within 4 to 6 hours was 11 (6.3 to 50) (11 studies, 765 participants, mostly non‐dental); the mean time to its use was 2.7 hours with codeine and 2.0 hours with placebo. More participants experienced adverse events with codeine 60 mg than placebo; the difference was not significant and none were serious. Two adverse event withdrawals occurred with placebo.

Authors' conclusions

Single dose codeine 60 mg provides good analgesia to few individuals, and does not compare favourably with commonly used alternatives such as paracetamol, NSAIDs and their combinations with codeine, especially after dental surgery; the large difference between dental and other surgery was unexpected. Higher doses were not evaluated.

Plain language summary

Single dose oral codeine, as a single agent, for acute postoperative pain in adults

This review assessed evidence from 2411 adults with moderate to severe postoperative pain in studies comparing single doses of codeine 60 mg with placebo. The number of individuals achieving a clinically useful amount of pain relief (at least 50%) with codeine compared to placebo was low. In all types of surgery combined, 12 participants would need to be treated with codeine 60 mg for one to experience this amount of pain relief who would not have done so with placebo. The need for use of additional analgesia within 4 to 6 hours was 38% with codeine compared with 46% with placebo, and the mean time to the use of additional analgesia was only slightly longer with codeine (2.7 hours) than with placebo (2 hours). More individuals experienced adverse events with codeine than with placebo, but the difference was not significant and none were serious or led to withdrawal. Other commonly used analgesics, alone and in combination with codeine 60 mg, provide better pain relief. Higher doses of codeine were not investigated in these studies.

Background

Acute pain occurs as a result of tissue damage either accidentally due to an injury or as a result of surgery. Acute postoperative pain is a manifestation of inflammation due to tissue injury. The management of postoperative pain and inflammation is a critical component of patient care. This is one of a series of reviews whose aim is to increase awareness of the range of analgesics that are potentially available, and present evidence for relative analgesic efficacy through indirect comparisons with placebo, in very similar trials performed in a standard manner, with very similar outcomes, and over the same duration. Such relative analgesic efficacy does not in itself determine choice of drug for any situation or patient, but guides policy‐making at the local level. Recently published reviews include paracetamol (Toms 2008), celecoxib (Derry 2008), naproxen (Derry C 2009a), ibuprofen (Derry C 2009b), diclofenac (Derry P 2009) and etoricoxib (Clarke 2009).

Single dose trials in acute pain are commonly short in duration, rarely lasting longer than 12 hours. The numbers of participants are small, allowing no reliable conclusions to be drawn about safety. To show that the analgesic is working it is necessary to use placebo (McQuay 2005). There are clear ethical concerns in doing this. These ethical concerns are answered by using acute pain situations where the pain is expected to go away, and by providing additional analgesia, commonly called rescue analgesia, if the pain has not diminished after about an hour. This is reasonable, because not all participants given an analgesic will have significant pain relief. Approximately 18% of participants given placebo will have significant pain relief (Moore 2005), and up to 50% may have inadequate analgesia with active medicines. The use of additional or rescue analgesia is hence important for all participants in the trials.

Clinical trials measuring the efficacy of analgesics in acute pain have been standardised over many years. Trials have to be randomised and double blind. Typically, in the first few hours or days after an operation, patients develop pain that is moderate to severe in intensity, and will then be given the test analgesic or placebo. Pain is measured using standard pain intensity scales immediately before the intervention, and then using pain intensity and pain relief scales over the following 4 to 6 hours for shorter acting drugs, and up to 12 or 24 hours for longer acting drugs. Pain relief of half the maximum possible pain relief or better (at least 50% pain relief) is typically regarded as a clinically useful outcome. For patients given rescue medication it is usual for no additional pain measurements to be made, and for all subsequent measures to be recorded as initial pain intensity or baseline (zero) pain relief (baseline observation carried forward). This process ensures that analgesia from the rescue medication is not wrongly ascribed to the test intervention. In some trials the last observation is carried forward, which gives an inflated response for the test intervention compared to placebo, but the effect has been shown to be negligible over 4 to 6 hours (Moore 2005). Patients usually remain in the hospital or clinic for at least the first 6 hours following the intervention, with measurements supervised, although they may then be allowed home to make their own measurements in trials of longer duration.

Codeine is an opioid. Its analgesic effects are attributed to its metabolism in the liver to the active compounds morphine and morphine‐6‐glucuronide. Normally between 5% and 10% is converted to morphine, and a dose of about 30 mg codeine phosphate is considered equivalent to 3 mg morphine. The capacity to metabolise codeine to its active metabolites varies between individuals, however, with up to 10% of Caucasians, 2% of Asians and 1% of Arabs being "poor metabolizers" (Cascarbi 2003). In these individuals codeine is a relatively ineffective analgesic. A few individuals are "extensive metabolizers" and are able to convert more of the codeine to morphine, putting them at increased risk of toxicity from standard doses. Various medications interfere with the enzymes that catalyse the metabolism of codeine, increasing or decreasing the extent of conversion and hence the analgesic effect. For example, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors fluoxetine and paroxetine reduce conversion, while rifampicin and dexamethasone increase it.

As with other opioids, repeated administration of codeine in the absence of pain can cause dependence and tolerance, but long term use for pain relief, or use of high doses, tends to be limited by adverse effects, in particular constipation and drowsiness. In severe or persistent pain, or both, for which large amounts of codeine are required, smaller doses of stronger opioids are thought to be better tolerated. Respiratory depression is dose‐related and may have serious consequences in people without previous experience of opioid use, those who are "extensive metabolizers", and the elderly in whom reduced renal function leads to accumulation of active metabolites.

Codeine is administered by mouth (as tablets or syrup) or intramuscular injection, and in some countries as suppositories. In many countries it is a controlled substance, but may be available in small quantities without prescription, in combination analgesics such as paracetamol plus codeine, and in cough syrups. In 2008 in England, there were almost 2.6 million prescriptions for codeine phosphate, mostly as 30 mg and 15 mg tablets, with many more for combination products (PCA 2008).

Objectives

To evaluate the analgesic efficacy and safety of single dose oral codeine using methods that permit comparison with other analgesics evaluated in the same way, using wider criteria of efficacy recommended by an in‐depth study at the individual patient level (Moore 2005).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies were included if they were full publications of double blind trials of single dose oral codeine as a single agent compared with placebo for the treatment of moderate to severe postoperative pain in adults, with at least 10 participants randomly allocated to each treatment group. Multiple dose studies were included when appropriate data from the first dose were available, and cross‐over studies were eligible for inclusion provided that data from the first arm were presented separately. Comparisons using codeine in combination with a non‐opioid analgesic, such as paracetamol, aspirin or ibuprofen, were not included in this review (paracetamol with codeine is reviewed in Toms 2009).

Studies were excluded if they were:

posters or abstracts not followed up by full publication;

reports of studies concerned with pain other than postoperative pain (including experimental pain);

studies using healthy volunteers;

studies where pain relief is assessed by clinicians, nurses or carers (i.e. not patient‐reported);

studies of less than 4 hours' duration or which fail to present data over 4 to 6 hours post‐dose.

Types of participants

Studies of adult participants (15 years old or above) with established moderate to severe postoperative pain were included. For studies using a visual analogue scale (VAS), pain of at least moderate intensity was assumed when the VAS score was greater than 30 mm (Collins 1997). Studies of participants with postpartum pain were included provided the pain investigated resulted from episiotomy or Caesarean section (with or without uterine cramp). Studies investigating participants with pain due to uterine cramps alone were excluded.

Types of interventions

Orally administered codeine or matched placebo for relief of postoperative pain.

Types of outcome measures

Data collected included the following:

characteristics of participants;

pain model;

patient‐reported pain at baseline (physician, nurse, or carer reported pain was not included in the analysis);

patient‐reported pain relief or pain intensity, or both, expressed hourly over 4 to 6 hours using validated pain scales (pain intensity and pain relief in the form of visual analogue scales (VAS) or categorical scales, or both), or reported total pain relief (TOTPAR) or summed pain intensity difference (SPID) at 4 to 6 hours;

patient‐reported global assessment of treatment (PGE), using a standard five‐point scale;

number of participants using rescue medication, and the time of assessment;

time to use of rescue medication;

withdrawals ‐ all cause, adverse event;

adverse events ‐ participants experiencing one or more, and any serious adverse event, and the time of assessment.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following electronic databases were searched:

Cochrane CENTRAL (issue 4, 2009);

MEDLINE via Ovid (November 2009);

EMBASE via Ovid (November 2009;

Oxford Pain Database (Jadad 1996a);

Search strategies were developed in co‐operation with the Cochrane Pain, Palliative Care and Supportive Care Cochrane Review Group. See Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy, Appendix 2 for the EMBASE search strategy, and Appendix 3 for the CENTRAL search strategy.

Additional studies were sought from the reference lists of retrieved articles and reviews.

Language

No language restriction was applied.

Unpublished studies

Abstracts, conference proceedings and other grey literature were not searched.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed and agreed the search results for studies that might be included in the review. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or referral to a third review author.

Quality assessment

Two review authors independently assessed the included studies for quality using a five‐point scale (Jadad 1996b).

The scale used is as follows.

Is the study randomised? If yes give one point.

Is the randomisation procedure reported and is it appropriate? If yes add one point, if no deduct one point.

Is the study double blind? If yes then add one point.

Is the double blind method reported and is it appropriate? If yes add one point, if no deduct one point.

Are the reasons for patient withdrawals and dropouts described? If yes add one point.

Data management

Two review authors extracted data using a standard data extraction form. Data suitable for pooling were entered into RevMan 5.0.

Data Analysis

QUOROM guidelines were followed (Moher 1999). For efficacy analyses we used the number of participants in each treatment group who were randomised, received medication, and provided at least one post‐baseline assessment. For safety analyses we used the number of participants who received study medication in each treatment group. Analyses were planned for different doses. Sensitivity analyses were planned for pain model (dental versus other postoperative pain), trial size (39 or fewer versus 40 or more per treatment arm), and quality score (two versus three or more). A minimum of two studies and 200 participants were required for any analysis (Moore 1998).

Primary outcome:

Number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief

For each study, mean TOTPAR (total pain relief) or SPID (summed pain intensity difference) for active and placebo groups were converted to %maxTOTPAR or %maxSPID by division into the calculated maximum value (Cooper 1991). The proportion of participants in each treatment group who achieved at least 50%maxTOTPAR was calculated using verified equations (Moore 1996; Moore 1997a; Moore 1997b). These proportions were then converted into the number of participants achieving at least 50%maxTOTPAR by multiplying by the total number of participants in the treatment group. Information on the number of participants with at least 50%maxTOTPAR for active treatment and placebo was used to calculate relative benefit (RB), and number needed to treat to benefit (NNT) when there was a statistically significant effect. Pain measures accepted for the calculation of TOTPAR or SPID were:

five‐point categorical pain relief (PR) scales with comparable wording to "none, slight, moderate, good or complete";

four‐point categorical pain intensity (PI) scales with comparable wording to "none, mild, moderate, severe";

Visual analogue scales (VAS) for pain relief;

VAS for pain intensity.

If none of these measures were available, numbers of participants reporting "very good or excellent" on a five‐point categorical global scale with the wording "poor, fair, good, very good, excellent" could be taken as those achieving at least 50% pain relief (Collins 2001).

Further details of the scales and derived outcomes are in the glossary (Appendix 4).

Secondary outcomes:

1. Use of rescue medication

The numbers of participants requiring rescue medication were used to calculate relative risk (RR) and numbers needed to treat to prevent (NNTp) use of rescue medication for treatment and placebo groups. Median (or mean) time to use of rescue medication were used to calculate the weighted mean of the median (or mean) for the outcome. Weighting was by number of participants.

2. Adverse events

Numbers of participants reporting adverse events for each treatment group were used to calculate RR and numbers needed to treat to harm (NNH) estimates for:

any adverse event;

any serious adverse event (as reported in the study);

withdrawal due to an adverse event.

3. Withdrawals

Withdrawals for reasons other than lack of efficacy (participants using rescue medication ‐ see above) and adverse events were noted, as were exclusions from analysis where data were presented.

RB or RR estimates were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using a fixed‐effect model (Morris 1995). NNT, NNTp and NNH with 95% CI were calculated using the pooled number of events by the method of Cook and Sackett (Cook 1995). A statistically significant difference from control was assumed when the 95% CI of the RB did not include the number one.

Homogeneity of studies was assessed visually (L'Abbe 1987). The z test (Tramer 1997) was used to determine if there was a significant difference between NNTs for different doses of active treatment, or between groups in the sensitivity analyses.

Results

Description of studies

Searches identified 25 potentially relevant reports, 20 of which satisfied inclusion criteria. One,(Moore 1997) was a meta‐analysis of 17 unpublished trials involving tramadol and codeine. One of these trials was subsequently published and identified by our searches (Moore 1998), and reported some outcomes not available in the meta‐analysis. In 17 studies (nine in Moore 1997) participants had undergone dental or oral surgery, in five they had mostly episiotomy, and in 13 (eight in Moore 1997) they underwent various surgical procedures including Caesarian section, urogenital surgery, appendectomy, cholecystectomy and herniorrhaphy.

The 35 studies involved 1223 participants treated with a single 60 mg dose of codeine, 27 with 90 mg codeine, and 1252 with placebo.

Study duration was six hours in 30 studies, four hours in two studies, and 12, eight and five hours in the remaining three studies. Two studies (Hebertson 1986; Yonkeura 1987) included a multiple dose phase, but reported efficacy outcomes for a single dose of study medication at 4 or 6 hours.

Details of included studies are in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Five studies were excluded after reading the full paper (Brunelle 1988; Coutinho 1976; Gleason 1987; Offen 1985; Petersen 1978). Details are in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Methodological quality of included studies

All included studies were both randomised and double blind. Six studies had a score of 3 using the Oxford Quality Scale (Bentley 1987; Defoort 1983; Honig 1984; Jain 1988; Sunshine 1988, van Steenberghe 1986), 9 a score of 4 (Baird 1980; Bloomfield 1981; Cooper 1982; Desjardins 1984; Giglio 1990; Hersh 1993; Mehlisch 1984; Sunshine 1987; Yonkeura 1987), and 20 a score of 5 (Forbes 1986; Hebertson 1986; Moore 1997 (17 studies); Sunshine 1983). Points were mainly lost due to inadequate description of the methods of randomisation and double blinding. Two studies (Honig 1984; Mehlisch 1984) did not adequately report on withdrawals and exclusions. Details are in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

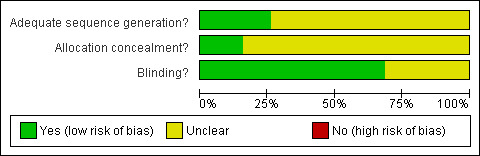

The Risk of Bias assessment did not identify any studies at high risk of bias, based on randomisation, allocation and blinding (Figure 1).

1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Effects of interventions

All studies used a 60 mg dose of codeine except for Mehlisch 1984, which used a 90 mg dose. There were insufficient data on the 90 mg dose for any analysis.

Number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief

Codeine 60 mg versus placebo

Thirty‐three studies (2411 participants) provided data (Baird 1980; Bentley 1987; Bloomfield 1981; Cooper 1982; Defoort 1983; Desjardins 1984; Forbes 1986; Giglio 1990; Hebertson 1986; Hersh 1993; Honig 1984; Jain 1988; Moore 1997 (17 studies); Sunshine 1983; Sunshine 1987; Sunshine 1988; Yonkeura 1987). One study (van Steenberghe 1986) did not provide data for this outcome.

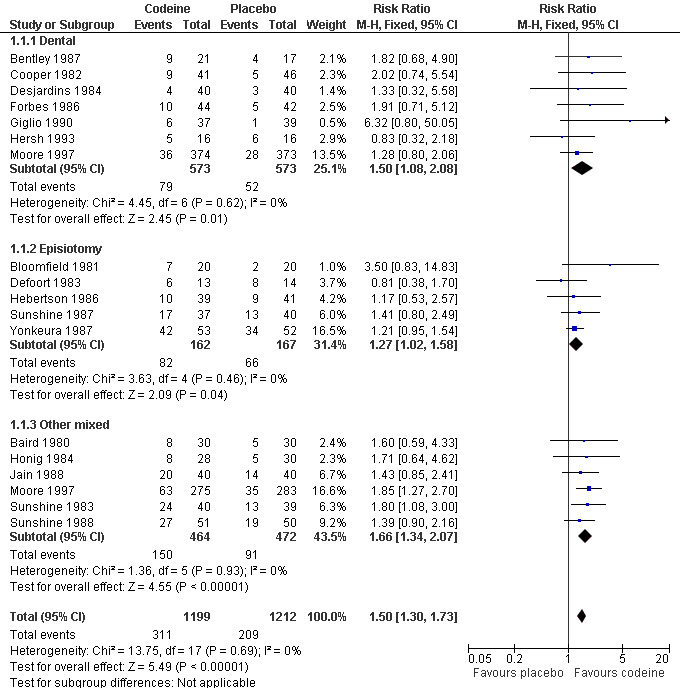

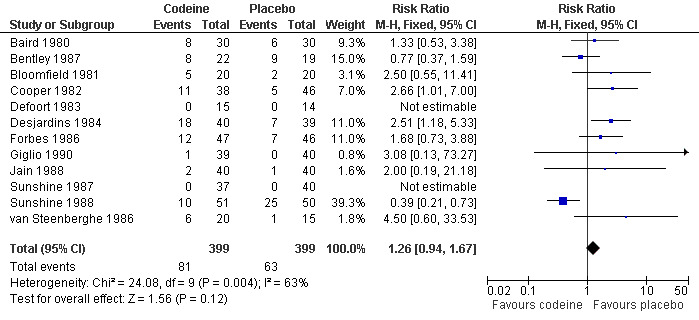

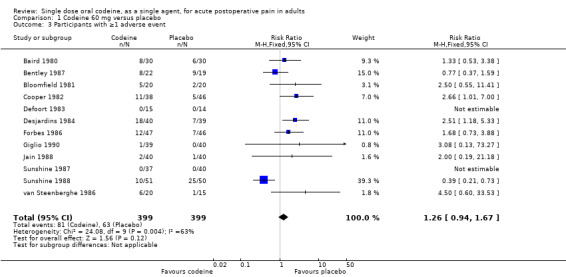

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours with codeine 60 mg was 26% (311/1199; range 10% to 79%).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours with placebo was 17% (209/1212; range 3% to 65%).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7), giving an NNT for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours of 12 (8.4 to 18) (Analysis 1.1).

Sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome

Methodological quality

All studies had scores of 3 or more, so no sensitivity analysis could be carried out for this criterion.

Pain model: dental versus other surgery

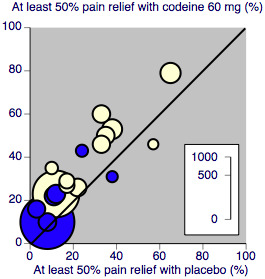

(Figure 2)

2.

L'Abbé plot showing heterogeneity between studies in dental pain (blue) and in other types of surgery (cream). Study size is proportional to size of circle (inset scale)

In 15 studies (nine in Moore 1997) 1146 participants underwent dental or oral surgery. The proportion of participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours was 14% (79/573) with codeine 60 mg and 9% (52/573) with placebo, giving a relative benefit of treatment compared to placebo of 1.5 (1.08 to 2.1), and an NNT of 21 (12 to 96).

In 18 studies (eight in Moore 1997) 1265 participants underwent other types of surgery, including episiotomy, Caesarian section, other gynaecological procedures, urogenital surgery, appendectomy, cholecystectomy and herniorrhaphy. The proportion of participants with at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours was 37% (232/626) with codeine 60 mg and 25% (157/639) with placebo, giving a relative benefit of treatment compared to placebo of 1.5 (1.3 to 1.8), and an NNT of 8.0 (5.7 to 13). There was no significant change in NNT when episiotomy and non‐episiotomy studies were analysed separately (Figure 3).

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Codeine 60 mg versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Participants with ≥50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

There was a significant difference in NNTs between studies in dental surgery and other types of surgery; z = 2.443, P = 0.015

Study size

Individual studies were small, with numbers of participants in active treatment arms ranging from 13 to 53, and in placebo treatment arms from 14 to 52. No sensitivity analysis could be carried out for this criterion.

| Summary of results A: Number of participants with ≥50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | ||||||

| Dose (mg) | Surgery | Studies | Participants | Codeine (%) | Placebo (%) | NNT (95%CI) |

| 60 | All | 33 | 2411 | 26 | 17 | 12 (8.4 to 18) |

| 60 | Dental | 15 | 1146 | 14 | 9 | 21 (12 to 96) |

| 60 | Non‐dental | 18 | 1265 | 37 | 25 | 8.0 (5.7 to 13) |

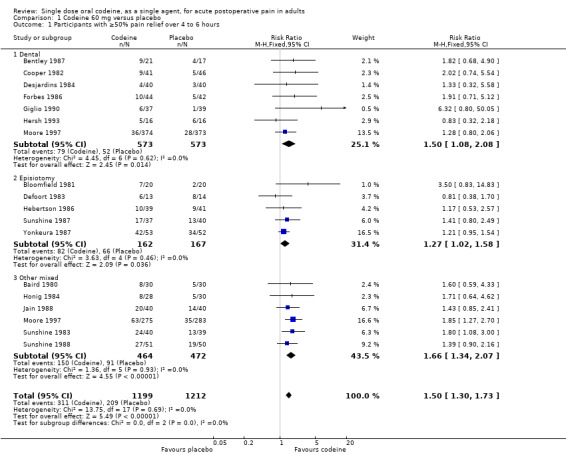

Use of rescue medication

Proportion of participants using rescue medication

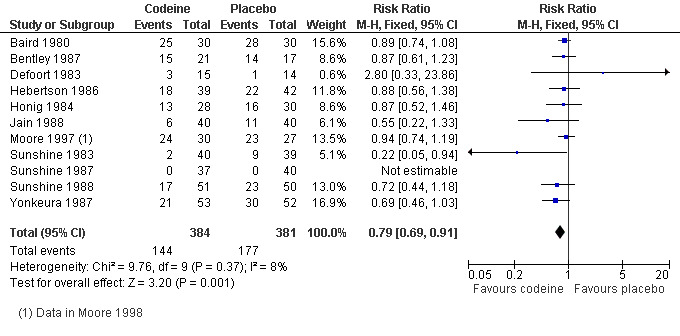

Eleven studies (765 participants) using codeine 60 mg reported this outcome after 4 or 6 hours. The proportion of participants using rescue medication was 38% (144/384) with codeine 60 mg and 46% (177/381) with placebo, giving a relative risk of 0.79 (0.69 to 0.91), and a number needed to treat to prevent remedication (NNTp) of 11 (6.3 to 50) (Figure 4).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Codeine 60 mg versus placebo, outcome: 1.2 Participants using rescue medication within 4 to 6 hours.

Time to use of rescue medication

Only two studies, with 124 participants, reported on median time to use of rescue medication. There were insufficient data for analysis. Four studies, with 275 participants, reported on mean time to use of rescue medication. The weighted mean of the mean time to use of rescue medication with codeine was 2.7 hours, and with placebo was 2.0 hours.

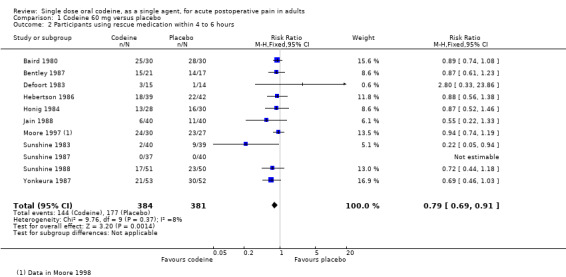

Adverse events

Any adverse event

It was not always clear what methods were used to collect adverse event data, and studies did not specify whether adverse event data continued to be collected after participants took rescue medication (which may have its own adverse events).

No details about adverse events were available for 18 of the 35 studies (the 17 studies reported in Moore 1997, and Hersh 1993)

Four studies (Honig 1984; Mehlisch 1984; Moore 1998 (included in Moore 1997, but published subsequently); Sunshine 1983) did not provide any usable data.

Two studies (Hebertson 1986; Yonkeura 1987) did not provide any data for the single dose phase.

Twelve studies (798 participants) using codeine 60 mg reported on the number of participants experiencing at least one adverse event. Most reported over 4 to 6 hours, but one reported over 8 hours (Jain 1988) and one over 12 hours (Sunshine 1988). It was not always clear whether studies continued to collect data for adverse events after participants withdrew, for example due to lack of efficacy (took rescue medication). Where specified, adverse events were usually of mild or moderate intensity.

The proportion of participants experiencing adverse events with codeine 60 mg was 20% (81/399) and with placebo was 16% (63/399), giving a relative risk of 1.3 (0.94 to 1.7). Although there were numerically more adverse events with codeine than placebo, the rates in the two treatment arms were not significantly different and the NNH was not calculated (Figure 5).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Codeine 60 mg versus placebo, outcome: 1.3 Participants with ≥1 adverse event.

Serious adverse events

No serious adverse events were reported in any included studies, although van Steenberghe 1986 reported that one participant treated with codeine 60 mg and one with placebo "had to seek immediate medical care after taking medication".

Withdrawals

Participants who took rescue medication were classified as withdrawals due to lack of efficacy. Details are reported under 'Use of rescue medication' above.

Only one study (Sunshine 1988) reported any withdrawals due to adverse events. These occurred in two participants treated with placebo.

Several other studies reported exclusions from analysis usually due to protocol violations, inadequate data collection and loss to follow up. In most cases the number of participants involved was unlikely to affect the results, but in two studies (Cooper 1982; Hersh 1993) more than 10% of participants were lost to follow up. Removing these studies from the analysis of the primary outcome did not change the result.

No details about withdrawals were available from the 17 studies in Moore 1997, although the studies were all scored as reporting on withdrawals in the meta‐analysis.

Details of analgesia outcomes and use of rescue medication in individual studies are in Table 1, and of adverse events and withdrawals in Table 2.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Thirty‐five studies were identified for inclusion, with 2411 participants in comparisons of codeine 60 mg with placebo. The size of individual study arms was relatively small, ranging from 13 to 53 participants across all the studies. Too few participants received codeine 90 mg for analysis of this dose.

The proportion of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours with codeine 60 mg in dental studies was 14%, compared with 9% with placebo, giving an NNT of 21 (12 to 96). In other types of surgery the proportion with this level of pain relief was higher at 37% with codeine 60 mg and 25% with placebo, giving an NNT of 8.0 (5.7 to 13).

No significant difference in NNTs was originally found between pain models for ibuprofen, paracetamol, and aspirin in relatively large data sets (Barden 2004). Subsequent analysis with more studies showed that the dental third molar extraction model produced significantly greater efficacy estimates than other types of surgery for ibuprofen (Derry C 2009b), with some support from analyses of naproxen (Derry C 2009a) and rofecoxib (Bulley 2009), but not paracetamol (Toms 2008). The results here with codeine indicate significantly lower efficacy estimates in the dental pain model, the opposite conclusion. This analysis, on 2400 participants, is the largest data set in which difference between NNTs in different pain models has been tested for an opioid. This preliminary evidence suggests that the dental pain model may be a less useful test of analgesic efficacy for opioids than other analgesics, especially non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs and paracetamol.

Slightly fewer participants required rescue medication over 4 to 6 hours with codeine 60 mg (38%) than with placebo (47%): for every 11 participants treated with codeine, one would not require rescue medication who would have done so with placebo. The mean time to use of rescue medication was 2.7 hours with codeine and 2.0 hours with placebo, based on data available from four studies.

More participants experience at least one adverse event with codeine 60 mg (21%) than with placebo (16%), but the difference was not significantly different.

Indirect comparisons of NNTs for at least 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours in reviews of other analgesics using identical methods indicate that codeine 60 mg performs poorly in comparison with other commonly used analgesics such as paracetamol 1000 mg (NNT 3.6 (3.4 to 4.0; Toms 2008), ibuprofen 400 mg (2.5 (2.4 to 2.6); Derry C 2009a), and naproxen 500 mg (2.7 (2.3 to 3.2); Derry C 2009b). For other outcomes, such as NNT to prevent use of rescue medication and time to use of rescue medication, codeine also performs poorly.

The reason for poor performance with codeine compared to non‐opioid analgesics in single dose postoperative pain studies is not understood. In part it may be due to about 10% of participants being poor metabolizers, and being unable to obtain any analgesia from codeine. Additionally, these studies provided information on only one dose of codeine, and higher doses may provide better pain relief. At some doses, adverse events commonly associated with opioids, particularly nausea, vomiting, and sedation, become intolerable, but that was not evident at 60 mg, and dose response was not investigated in these studies. Poor performance may also reflect that non‐opioid analgesics have more often been tested in the dental pain model, and that codeine is in some way disadvantaged by dental pain studies. Clinical experience with opioids in chronic pain conditions is that they are effective analgesics where adverse events are tolerated. Addition of 60 mg codeine to effective doses of paracetamol (600 mg to 1000 mg) increased the number of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief by 10% to 15% (roughly the same proportion as experienced this level of relief with codeine compared with placebo), giving NNTs of 5 to 8 for the combination compared to the same dose of paracetamol alone (Toms 2009). The corresponding NNTs for the same combinations compared with placebo were 2.2 and 3.9.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

All but one study contributed data for the primary outcome of at least 50% pain relief, but the number of studies contributing to analyses of adverse events and numbers of participants using rescue medication were considerably smaller. In part this is because data for these outcomes were not available from the unpublished studies used in the meta‐analysis of Moore 1997, where the aim was to validate meta‐analytical methods for efficacy. Despite this, the available data were sufficient to provide reasonable confidence in the results. Information was not available for analysis of doses other than 60 mg. This may be because clinical experience has shown that lower doses are ineffective and higher doses are compromised by troublesome adverse events.

Studies involved participants undergoing a variety of surgical procedures, including extraction of impacted third molars, episiotomy, Caesarian section, appendectomy, herniorrhaphy, gynaecologic, and other elective surgery, indicating that the results apply to a diverse range of postoperative situations. While elderly participants were not excluded from studies, the mean age in included studies ranged from 21 to 45 years, where most individuals were probably otherwise fit and healthy. Results may not be directly applicable to older patients, and those with co‐morbidities.

Quality of the evidence

All studies were randomised and double blind, scoring 3/5 or more for methodological quality on the Oxford Quality Scale, indicating that they are likely to be methodologically robust. Two studies did not adequately report exclusions and withdrawals. One (Mehlisch 1984) used codeine 90 mg so did not contribute to any analyses. Excluding the other (Honig 1984) from analyses did not change the results. A number of studies reported exclusions following randomisation, but these are unlikely to have resulted in overestimation of treatment effect. In single dose studies most exclusions occur for protocol violations such as failing to meet baseline pain requirements, or failing to return for post‐treatment visits after the acute pain results are concluded (McQuay 1982). For missing data it has been shown that over the 4 to 6 hour period, there is no difference between the baseline observation carried forward, which gives the more conservative estimate, and last observation carried forward (Moore 2005).

Studies were valid in that they recruited participants with adequate baseline pain and used clinically useful outcome measures. Treatment groups in individual studies were small, but pooling studies provided sufficient data for reliable estimates of efficacy outcomes for the 60 mg dose. Adverse event data were less well reported, with little information on whether data were collected after use of rescue medication (which may cause its own adverse events).

Potential biases in the review process

Exhaustive searches were carried out to identify relevant studies. Data extraction and analysis followed well established methods. We do not think there are any biases in the review process.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We are not aware of any other reviews of single dose codeine in acute postoperative pain.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Single doses of codeine 60 mg provide poor levels of analgesia in acute postoperative dental pain compared with other commonly used analgesics, such as ibuprofen, as measured by both numbers of participants achieving clinically useful levels of pain relief and duration of analgesia; better results are obtained for other types of postoperative pain, though these results are still relatively poor compared with other analgesics. In situations where an NSAID is contraindicated, paracetamol 1000 mg is likely to be a more effective option, and particularly the combination of paracetamol 1000 mg plus codeine 60 mg.

Implications for research.

It seems unlikely that further studies will use codeine as a single agent in acute pain situations, given the availability of good alternatives in terms of NSAIDs and paracetamol/opioid or NSAID/opioid combinations. Higher doses may provide better pain relief but adverse events are likely to be unacceptable. More understanding of the efficacy of fixed combinations of paracetamol with codeine would be welcome, as would more understanding of potential differences in sensitivity of pain models to analgesic drugs with different mechanisms of action.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 May 2019 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 10 November 2010 | Review declared as stable | The authors declare that there is unlikely to be any further studies to be included in this review and so it should be published as a 'stable review'. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2009 Review first published: Issue 4, 2010

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 September 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

Notes

The authors declare that there is unlikely to be any further studies to be included in this review and so it should be published as a 'stable review'.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE (via OVID) search strategy

Codeine/ or codeine.mp.

Pain, Postoperative/

((postoperative adj4 pain*) or (post‐operative adj4 pain*) or post‐operative‐pain* or (post* adj4 pain*) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi*) or (post‐operative adj4 analgesi*) or "post‐operative analgesi*").mp.

((post‐surgical adj4 pain*) or ("post surgical" adj4 pain*) or (post‐surgery adj4 pain*)).mp.

("pain‐relief after surg*" or "pain following surg*" or "pain control after").mp.

(("post surg*" or post‐surg*) and (pain* or discomfort)).mp.

((pain* adj4 "after surg*") or (pain* adj4 "after operat*") or (pain* adj4 "follow* operat*") or (pain* adj4 "follow* surg*")).mp.

((analgesi* adj4 "after surg*") or (analgesi* adj4 "after operat*") or (analgesi* adj4 "follow* operat*") or (analgesi* adj4 "follow* surg*")).mp.

exp Surgical Procedures, Operative/

or/2‐9

randomized controlled trial.pt.

controlled clinical trial.pt.

randomized.ab.

placebo.ab.

drug therapy.fs.

randomly.ab.

trial.ab.

groups.ab.

or/11‐18

1 and 10 and 19

Appendix 2. EMBASE (via OVID) search strategy

Codeine/

codeine.mp.

OR/1‐2

Pain, postoperative/

((postoperative adj4 pain$) or (post‐operative adj4 pain$) or post‐operative‐pain$ or (post$ adj4 pain$) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi$) or (post‐operative adj4 analgesi$) or ("post‐operative analgesi$")).mp.

((post‐surgical adj4 pain$) or ("post surgical" adj4 pain$) or (post‐surgery adj4 pain$)).mp.

(("pain‐relief after surg$") or ("pain following surg$") or ("pain control after")).mp.

(("post surg$" or post‐surg$) AND (pain$ or discomfort)).mp.

((pain$ adj4 "after surg$") or (pain$ adj4 "after operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")).mp.

((analgesi$ adj4 "after surg$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "after operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ surg$")).mp.

OR/4‐10

clinical trials.sh.

controlled clinical trials.sh.

randomized controlled trial.sh.

double‐blind procedure.sh.

(clin$ adj25 trial$)

((doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$))

placebo$

random$

OR/12‐19

3 AND 11 AND 20

Appendix 3. CENTRAL search strategy

MeSH descriptor Codeine.

codeine:ti,ab,kw.

or/1‐2

MESH descriptor Pain, postoperative

((postoperative near/4 pain*) or (post‐operative near/4 pain*) or post‐operative‐pain* or (post* near/4 pain*) or (postoperative near/4 analgesi*) or (post‐operative near/4 analgesi*) or ("post‐operative analgesi*")):ti,ab,kw.

((post‐surgical near/4 pain*) or ("post surgical" near/4 pain*) or (post‐surgery near/4 pain*)):ti,ab,kw.

(("pain‐relief after surg*") or ("pain following surg*") or ("pain control after")):ti,ab,kw.

(("post surg*" or post‐surg*) AND (pain* or discomfort)):ti,ab,kw.

((pain* near/4 "after surg*") or (pain* near/4 "after operat*") or (pain* near/4 "follow* operat*") or (pain* near/4 "follow* surg*")):ti,ab,kw.

((analgesi* near/4 "after surg*") or (analgesi* near/4 "after operat*") or (analgesi* near/4 "follow$ operat*") or (analgesi* near/4 "follow* surg*")):ti,ab,kw.

or/4‐10

Randomized controlled trial:pt.

random*:ti,ab,kw.

MeSH descriptor Double‐blind Method

or/12‐14

3 and 11 and 15

Limit 16 to Clinical Trials (CENTRAL)

Appendix 4. Glossary

Categorical rating scale: The commonest is the five category scale (none, slight, moderate, good or lots, and complete). For analysis numbers are given to the verbal categories (for pain intensity, none = 0, mild = 1, moderate = 2 and severe = 3, and for relief none = 0, slight = 1, moderate = 2, good or lots = 3 and complete = 4). Data from different subjects is then combined to produce means (rarely medians) and measures of dispersion (usually standard errors of means). The validity of converting categories into numerical scores was checked by comparison with concurrent visual analogue scale measurements. Good correlation was found, especially between pain relief scales using cross‐modality matching techniques. Results are usually reported as continuous data, mean or median pain relief or intensity. Few studies present results as discrete data, giving the number of participants who report a certain level of pain intensity or relief at any given assessment point. The main advantages of the categorical scales are that they are quick and simple. The small number of descriptors may force the scorer to choose a particular category when none describes the pain satisfactorily. VAS: Visual analogue scale: For pain intensity, lines with left end labelled "no pain" and right end labelled "worst pain imaginable", and for pain relief lines with left end labelled "no relief of pain" and right end labelled "complete relief of pain", seem to overcome the limitation of forcing patient descriptors into particular categories. Patients mark the line at the point which corresponds to their pain or pain relief. The scores are obtained by measuring the distance between the no relief end and the patient's mark, usually in millimetres. The main advantages of VAS are that they are simple and quick to score, avoid imprecise descriptive terms and provide many points from which to choose. More concentration and coordination are needed, which can be difficult post‐operatively or with neurological disorders. TOTPAR: Total pain relief (TOTPAR) is calculated as the sum of pain relief scores over a period of time. If a patient had complete pain relief immediately after taking an analgesic, and maintained that level of pain relief for six hours, they would have a six‐hour TOTPAR of the maximum of 24. Differences between pain relief values at the start and end of a measurement period are dealt with by the trapezoidal rule. This is a simple method that approximately calculates the definite integral of the area under the pain relief curve by calculating the sum of the areas of several trapezoids that together closely approximate to the area under the curve. SPID: Summed pain intensity difference (SPID) is calculated as the sum of the differences between the pain scores and baseline pain score over a period of time. Differences between pain intensity values at the start and end of a measurement period are dealt with by the trapezoidal rule. VAS TOTPAR and VAS SPID are visual analogue versions of TOTPAR and SPID. See "Measuring pain" in Bandolier's Little Book of Pain, Oxford University Press, Oxford. 2003; pp 7‐13 (Moore 2003).

Appendix 5. Summary of outcomes: analgesia and use of rescue medication

| Analgesia | Rescue medication | |||||

| Study ID | Treatment | PI or PR | Number with 50% PR | PGE: v good or excellent | Median time to use (h) | Number using |

| Baird 1980 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 30 (2) Zomepirac 50 mg, n = 30 (3) Zomepirac 100 mg, n = 29 (4) APC+codeine 60 mg, n = 29 (5) Placebo, n = 30 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 7.0 (5) 5.1 |

(1) 8/30 (5) 5/30 |

No data | No data | At 6 h: (1) 25/30 (5) 28/30 |

| Bentley 1987 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 21 (2) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n = 41 (3) Paracetamol + codeine 1000/60 mg, n = 41 (4) Placebo, n = 17 |

TOTPAR 5: (1) 7.8 (4) 4.9 |

(1) 9/21 (4) 4/17 |

Not reported | (1) 1.84 (4) 1.44 |

At 4 h: (1) 15/21 (4) 14/17 |

| Bloomfield 1981 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 20 (2) Propiram 50 mg, n = 20 (3) Propiram 100 mg, n = 20 (4) Placebo, n = 20 |

SPID 6: (1) 39.0 (4) 31.7 |

(1) 7/20 (4) 2/20 |

No data | No data | No data |

| Cooper 1982 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 41 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 38 (3) Ibuprofen + Codeine 400/60 mg, n = 41 (4) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 38 (5) Aspirin + codeine 650/60 mg, n = 45 (6) Placebo, n = 46 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 4.1 (6) 2.7 |

(1) 9/41 (6) 5/46 |

No usable data | Mean: (1) 2.64 (6) 2.39 |

No data |

| Defoort 1983 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 15 (2) Ciramadol 30 mg, n = 13 (3) Ciramadol 60 mg, n = 12 (4) Placebo, n = 14 |

SPID 6: (1) 22.2 (4) 19.9 |

(1) 6/13 (4) 8/14 |

No data | No data | (1) 3/15 (4) 1/14 |

| Desjardins 1984 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 40 (2) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 40 (3) Propiram 50 mg, n = 40 (4) Placebo, n = 40 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 3.9 (4) 3.23 |

(1) 4/40 (4) 3/40 |

No usable data | Mean: (1) 2.1 (4) 2.0 |

No data |

| Forbes 1986 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 44 (2) Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 38 (3) Naproxen sodium + codeine 550/60 mg, n = 38 (4) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 36 (5) Placebo, n = 42 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 6.4 (5) 4.1 |

(1) 10/44 (5) 5/42 |

No usable data | (1) 2.83 (5) 1.94 |

At 12 h: (1) 33/44 (5) 36/42 |

| Giglio 1990 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 39 (2) Meclofenamate 100 mg, n = 41 (3) Meclofen/codeine 50/30 mg, n = 40 (4) Meclofen/codeine 100/60 mg, n = 40 (5) Placebo, n = 40 196 for efficacy: 37, 41, 39, 39, 39 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 5.0 (5) 2.6 |

(1) 6/37 (5) 1/39 |

No usable data | Mean: (1) 2.89 (5) 1.80 |

No data |

| Herbertson 1986 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 39 (2) Meclofenamate 100 mg, n = 41 (3) Meclofenamate 200 mg, n = 40 (4) Placebo, n = 41 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 6.9 (4) 5.9 |

(1) 10/39 (4) 9/41 |

No usable data | No data | At 6 h: (1) 18/39 (4) 22/42 |

| Hersh 1993 | All pts pretreated with placebo (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 16 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 12 (3) Placebo, n = 16 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 7.4 (3) 9.0 |

(1) 5/16 (3) 6/16 |

No usable data | Mean: (1) 4.2 (3) 1.5 |

No data |

| Honig 1984 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 28 (2) Paracetamol 600 mg, n = 28 (3) Paracetamol + codeine 600/60 mg, n = 30 (4) Placebo, n = 30 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 7.2 (4) 5.2 |

(1) 8/28 (4) 5/30 |

At 6 h: (1) 6/27 (4) 4/30 |

No data | At 6 h: (1) 13/28 (4) 16/30 |

| Jain 1988 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 40 (2) Diflunisal 500 mg, n = 41 (3) Diflunisal + codeine 500/60 mg, n = 40 (4) Placebo, n = 40 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 7.3 (4) 5.5 |

(1) 20/40 (4) 14/40 |

At 8 h: (1) 12/40 (4) 7/40 |

No data | At 4 h: (1) 6/40 (4) 11/40 |

| Mehlisch 1984 | (1) Codeine 90 mg, n = 27 (2) Ketoprofen 25 mg, n = 24 (3) Ketoprofen 50 mg, n = 27 (4) Ketoprofen 100 mg, n = 27 (5) Placebo, n = 24 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 3.8 (5) 1.8 |

(1) 3/27 (5) 0/24 |

No usable data | No data | At 6 h: (1) 23/27 (5) 23/24 |

| Moore 1997 | Dental: (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 374 (2) Placebo, n = 373 Other surgery: (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 275 (2) Placebo, n = 283 |

Dental (1) 36/374 (2) 28/373 Other (1) 63/275 (2) 35/283 |

No data | No data | No data | |

| Moore 1998 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 33 (2) Aspirin + codeine 650/60 mg, n = 41 (3) Tramadol 50 mg, n = 49 (4) Tramadol 100 mg, n = 49 (5) Placebo, n = 27 |

included in Moore 1997 | No usable data | No usable data | At 6 h: (1) 24/30 (5) 23/27 |

|

| Sunshine 1983 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 40 (2) Propiram fumarate 50 mg, n = 41 (3) Placebo, n = 39 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 8.6 (3) 5.3 |

(1) 24/40 (3) 13/39 |

No data | No data | At 6 h: (1) 2/40 (3) 9/39 |

| Sunshine 1987 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 37 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 38 (3)Ibuprofen + codeine 200/30 mg, n= 40 (4) Ibuprofen + codeine 400/60 mg, n = 40 (5) Placebo, n = 40 |

TOTPAR 4: (1) 7.0 (5) 5.2 |

(1) 17/37 (2) 13/40 |

No useable data | No useable data | At 4 h: (1) 8/37 (5) 20/40 |

| Sunshine 1988 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 51 (2) Piroxicam 20 mg, n = 50 (3) Placebo, n = 50 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 11.8 (3) 9.1 |

(1) 27/51 (3) 19/50 |

No data | No usable data | At 6 h: (1) 17/51 (3) 23/50 |

| van Steenberghe 1986 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 20 (2) Ciramadol 15 mg, n = 13 (3) Ciramadol 30 mg, n = 15 (4) Ciramadol 60 mg, n = 20 (5) Placebo, n = 15 |

No usable data | No data | No data | No usable data | |

| Yonkeura 1987 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 53 (2) Meclofenamate 100 mg, n = 55 (3) Meclofenamate 200 mg, n = 55 (4) Placebo, n = 52 |

TOTPAR 6: (1) 16.4 (4) 14.0 |

(1) 42/53 (4) 34/52 |

No usable data | No data | At 6 h: (1) 21/53 (4) 30/52 |

Appendix 6. Summary of outcomes: adverse events and withdrawals

| Adverse events | Withdrawals | ||||

| Study ID | Treatment | Any | Serious | Adverse event | Other |

| Baird 1980 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 30 (2) Zomepirac 50 mg, n = 30 (3) Zomepirac 100 mg, n = 29 (4) APC+codeine 60 mg, n = 29 (5) Placebo, n = 30 |

At 6 h: (1) 8/30 (5) 6/30 Mostly minimal CNS |

None | None | Exclusions: 8 from efficacy for administrative reasons |

| Bentley 1987 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 21 (2) Paracetamol 1000 mg, n = 41 (3) Paracetamol + codeine 1000/60 mg, n = 41 (4) Placebo, n = 17 |

At 5 h: (1) 8/22 (2) 21/42 (3) 15/42 (4) 9/19 |

None reported | None | Exclusions: 5 did not take med appropriately, 1 took rescue med <1 h, 1 vomited <30 min, 1 lost to follow up |

| Bloomfield 1981 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 20 (2) Propiram 50 mg, n = 20 (3) Propiram 100 mg, n = 20 (4) Placebo, n = 20 |

At 6 h: (1) 5/2 (4) 2/20 |

None reported | None | None |

| Cooper 1982 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 41 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 38 (3) Ibuprofen + Codeine 400/60 mg, n = 41 (4) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 38 (5) Aspirin + codeine 650/60 mg, n = 45 (6) Placebo, n = 46 |

At 4 h: (1) 11/38 (6) 5/46 |

None | None | Exclusions: 30 lost to follow up, 15 did not require medication, 11 remedicated before 1 h, 6 missed more the 1 evaluation, 3 medicated with slight pain, 1 did not take all the medication, 1 medicated over 24h after surgery |

| Defoort 1983 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 15 (2) Ciramadol 30 mg, n = 13 (3) Ciramadol 60 mg, n = 12 (4) Placebo, n = 14 |

1 pt in (3) | None | None | Exclusions from efficacy analysis: 5 (2 codeine ‐ unable to use VAS) |

| Desjardins 1984 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 40 (2) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 40 (3) Propiram 50 mg, n = 40 (4) Placebo, n = 40 |

(1) 18/40 (2) 14/40 (3) 18/40 (4) 7/39 |

None reported | None | Exclusion: 1 placebo pt lost to follow up |

| Forbes 1986 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 44 (2) Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 38 (3) Naproxen sodium + codeine 550/60 mg, n = 38 (4) Aspirin 650 mg, n = 36 (5) Placebo, n = 42 |

(1) 12/47 (5) 7/46 |

None | None reported | None reported |

| Giglio 1990 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 39 (2) Meclofenamate 100 mg, n = 41 (3) Meclofen/codeine 50/30 mg, n = 40 (4) Meclofen/codeine 100/60 mg, n = 40 (5) Placebo, n = 40 196 for efficacy: 37, 41, 39, 39, 39 |

(1) 1/3 (5) 0/40 |

None reported | None | Exclusions: 2 codeine , 2 meclofen/codeine, 1 placebo (took rescue med early) |

| Herbertson 1986 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 39 (2) Meclofenamate 100 mg, n = 41 (3) Meclofenamate 200 mg, n = 40 (4) Placebo, n = 41 |

No usable single dose data. Did not differ between groups |

None reported | None | None |

| Hersh 1993 | All pts pretreated with placebo (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 16 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 12 (3) Placebo, n = 16 |

No data | None reported | None reported | Exclusions from entire study: 19 lost to follow up, 11 did not require medication, 3 excluded for various protocol violations. |

| Honig 1984 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 28 (2) Paracetamol 600 mg, n = 28 (3) Paracetamol + codeine 600/60 mg, n = 30 (4) Placebo, n = 30 |

Occurred in all groups, all mild or moderate, except 1 severe dry mouth | None reported | None reported | None reported |

| Jain 1988 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 40 (2) Diflunisal 500 mg, n = 41 (3) Diflunisal + codeine 500/60 mg, n = 40 (4) Placebo, n = 40 |

(1) 2/40 (4) 1/40 All somnolence |

None | None | 1 participant in (2) excluded because took aspirin |

| Mehlisch 1984 | (1) Codeine 90 mg, n = 27 (2) Ketoprofen 25 mg, n = 24 (3) Ketoprofen 50 mg, n = 27 (4) Ketoprofen 100 mg, n = 27 (5) Placebo, n = 24 |

54 participants in total | None reported | None reported | 9 participants received medication but were not included in analysis. Reasons and groups not given. |

| Moore 1997 | Dental: (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 374 (2) Placebo, n = 373 Other surgery: (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 275 (2) Placebo, n = 283 |

No data | No data | No data | No data |

| Moore 1998 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 33 (2) Aspirin + codeine 650/60 mg, n = 41 (3) Tramadol 50 mg, n = 49 (4) Tramadol 100 mg, n = 49 (5) Placebo, n = 27 |

No usable data | None reported | None | Exclusions: 7 (2 codeine) for protocol violations or inadequate data |

| Sunshine 1983 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 40 (2) Propiram fumarate 50 mg, n = 41 (3) Placebo, n = 39 |

No usable data | None | None | Exclusions: 2 (codeine and placebo) for protocol violations |

| Sunshine 1987 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 37 (2) Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 38 (3)Ibuprofen + codeine 200/30 mg, n = 40 (4) Ibuprofen + codeine 400/60 mg, n = 40 (5) Placebo, n = 40 |

At 4 hrs: (1) 0/37 (5) 0/40 |

None | None | Exclusions: 5 (1 had not complied with the washout period and 4 did not complete the evaluations) |

| Sunshine 1988 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 51 (2) Piroxicam 20 mg, n = 50 (3) Placebo, n = 50 |

At 12 h: (1) 10/51 (3) 25/50 |

None | 2 in placebo group | None |

| van Steenberghe 1986 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 20 (2) Ciramadol 15 mg, n = 13 (3) Ciramadol 30 mg, n = 15 (4) Ciramadol 60 mg, n = 20 (5) Placebo, n = 15 |

(1) 6/20 (5) 1/15 considered at least poss rel to study drug |

None reported as serious. "1 codeine and 1 placebo pt had to seek immediate medical care after taking medication" | None reported | None reported |

| Yonkeura 1987 | (1) Codeine 60 mg, n = 53 (2) Meclofenamate 100 mg, n = 55 (3) Meclofenamate 200 mg, n = 55 (4) Placebo, n = 52 |

No single dose data | None reported | None reported | 5 exclusions for protocol violations |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Codeine 60 mg versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Participants with ≥50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | 17 | 2411 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.50 [1.30, 1.73] |

| 1.1 Dental | 7 | 1146 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.50 [1.08, 2.08] |

| 1.2 Episiotomy | 5 | 329 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [1.02, 1.58] |

| 1.3 Other mixed | 6 | 936 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.66 [1.34, 2.07] |

| 2 Participants using rescue medication within 4 to 6 hours | 11 | 765 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.69, 0.91] |

| 3 Participants with ≥1 adverse event | 12 | 798 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.26 [0.94, 1.67] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Codeine 60 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 Participants with ≥50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Codeine 60 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Participants using rescue medication within 4 to 6 hours.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Codeine 60 mg versus placebo, Outcome 3 Participants with ≥1 adverse event.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Baird 1980.

| Methods | R, DB, 5 parallel groups. Single oral dose Medication administered when baseline pain reached moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 min, then hourly up to 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Various surgical procedures, including orthopaedic, hernia, hysterectomy N = 156 (148 analysed for efficacy) M = 86, F = 60 Mean age 40 years |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 30 Zomepirac 50 mg, n = 30 Zomepirac 100 mg, n = 29 APC+codeine 60 mg, n = 29 Placebo, n = 30 (APC ‐ aspirin 454 mg, phenacetin 324 mg, caffeine 64 mg) |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4 Rescue medication allowed after 2 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | "identical‐appearing capsules" |

Bentley 1987.

| Methods | R, DB, 4 parallel groups. Single oral dose Medication administered when baseline pain reached moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at baseline then hourly up to 5 hours |

|

| Participants | Oral surgery involving impacted tooth or removal of bone N = 128 (120 analysed for efficacy) M = 46, F = 74 Mean age 25 years |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 21 Paracetamol 1000 mg, n = 41 Paracetamol + codeine 1000/60 mg, n = 41 Placebo, n = 17 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: non‐standard 10 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale PGE: standard 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described |

Bloomfield 1981.

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, 4 parallel groups. Single oral dose Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 min, then hourly up to 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Episiotomy N = 80 All F Mean age not given |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 20 Propiram 50 mg, n = 20 Propiram 100 mg, n = 20 Placebo, n = 20 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale Averse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | "identical in appearance and taste" |

Cooper 1982.

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, 6 parallel groups. Single oral dose Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at baseline then hourly to 4 hours |

|

| Participants | Surgical removal of 1 to 4 impacted third molars N = 249 M = 83, F = 166 Mean age 23 years |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 41 Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 38 Ibuprofen + Codeine 400/60 mg, n = 41 Aspirin 650 mg, n = 38 Aspirin/codeine 650mg/60 mg, n = 45 Placebo, n = 46 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale PGE: standard 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4 Rescue medication allowed after 1 hour |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Pharmaceutical company held randomisation code and packaged bottles, which were identified by sequential code number only |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | tablets "appeared identical for every patient" |

Defoort 1983.

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, 4 parallel groups. Single oral dose Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 min, then hourly up to 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Episiotomy N = 54 All F Age not reported |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 15 Ciramadol 30 mg, n = 13 Ciramadol 60 mg, n = 12 Placebo, n = 14 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 10 cm VAS PR: standard 10 cm VAS Use of rescue medication Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 3 Rescue medication allowed after 2 hours |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described |

Desjardins 1984.

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, 4 parallel groups. Single oral dose Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 min, then hourly up to 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Surgical removal of impacted teeth, mainly third molars N = 160 M = 77, F = 82 Man age 25 years |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 40 Aspirin 650 mg, n = 40 Propiram 50 mg, n = 40 Placebo, n = 40 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale PGE: standard 5 point scale Time use of rescue medication Adverse events: any, serious Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4 Participants asked to wait "as long as possible" before using rescue medication |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Medication "identified only by numerical code" |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | capsules "identical in appearance" |

Forbes 1986.

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, 5 parallel groups. Single oral dose Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at baseline, then hourly up to 12 hours |

|

| Participants | Surgical removal of impacted third molars N = 198 M = 79, F = 119 Mean age 25 years |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 44 Naproxen sodium 550 mg, n = 38 Naproxen sodium + codeine 550/60 mg, n = 38 Aspirin 650 mg, n = 36 Placebo, n = 42 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale PGE: standard 5 point scale Time use of rescue medication Adverse events: any, serious Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R2, DB2, W1. Total = 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Computer assigned patient numbers "using a random‐numbers generator" |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | "All tablets were identical in appearance" |

Giglio 1990.

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, 5 parallel groups. Single oral dose Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 min, then hourly to 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Surgical removal of impacted third molars N = 200 (196 analysed for efficacy) M = 35, F = 165 Mean age 23 years |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 39 Meclofenamate 100 mg, n = 41 Meclofenamate/codeine 50/30 mg, n = 40 Meclofenamate/codeine 100/60 mg, n = 40 Placebo, n = 40 196 for efficacy: 37, 41, 39, 39, 39 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale PGE: standard 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4 Timing for use of rescue medication not given |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | "All study medications were identical in appearance" |

Hebertson 1986.

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, 4 parallel groups. Single and multiple oral dose phases Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 mins, then hourly to 6 hours for single dose |

|

| Participants | Episiotomy N = 161 All F Mean age 24 years |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 39 Meclofenamate 100 mg, n = 41 Meclofenamate 200 mg, n = 40 Placebo, n = 41 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale PGE: non‐standard 3 point scale Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R2, DB2, W1. Total = 5 Rescue medication allowed after 1 hour |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | "computer‐generated randomization table" |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | "All capsules were identical in appearance" |

Hersh 1993.

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, 3 parallel groups. Single oral dose (placebo given to all participants pre‐surgery) Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 mins, then hourly to 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Surgical removal of impacted third molars N = 114 M/F not given Age not given |

|

| Interventions | One group of participants received placebo before surgery Codeine 60 mg, n =16 Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 12 Placebo, n = 16 Remaining group (37) received naltrexone before surgery, then codeine, ibuprofen or placebo postoperatively |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale PGE: standard 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events: any, serious Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | "capsules appeared identical" |

Honig 1984.

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, 4 parallel groups. Single oral dose Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 mins, then hourly to 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Various elective surgical procedures, including orthopaedic, abdominal and thoracic N = 116 M = 71, F = 45 Mean age 45 years |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 28 Paracetamol 600 mg, n = 28 Paracetamol + codeine 600/60 mg, n = 30 Placebo, n = 30 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale PGE: standard 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events: any, serious Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R1, DB2, W0. Total = 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | "Capsules were identical in appearance" |

Jain 1988.

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, 4 parallel groups. Single oral dose Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 mins, then hourly to 8 hours |

|

| Participants | Various surgical procedures, mostly Cesarian section and common gynaecological operations N = 161 M = 29, F = 132 Mean age 29 years |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 40 Diflunisal 500 mg, n = 41 Diflunisal/codeine 500/60 mg, n = 40 Placebo, n = 40 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale PGE: standard 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events: any, serious Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 3 No details about timing of rescue medication |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described |

Mehlisch 1984.

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, 5 parallel groups. Single oral dose Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 mins, then hourly to 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Surgical removal of impacted third molars N = 129 M/F not given Mean age 26 years |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 90 mg, n = 27 Ketoprofen 25 mg, n = 24 Ketoprofen 50 mg, n = 27 Ketoprofen 100 mg, n = 27 Placebo, n = 24 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale PGE: standard 5 point scale (1 to 5 and reverse order) Use of rescue medication Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R2, DB2, W0. Total = 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Medication "distributed on the basis of a random code" |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Medication was in an envelope |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | "identical capsules" |

Moore 1997.

| Methods | Individual patient data meta‐analysis of trials of tramadol versus placebo, codeine and combination analgesics. All included trials were randomised, double blind, parallel group studies using a single oral doses. Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 mins, then hourly to 6 hours |

|

| Participants | A. Dental surgery, such as removal of impacted third molars (9 trials) N = 747 B. Various surgical procedures, such as abdominal, orthopaedic or gynaecological operations (9 trials) N = 558 M/F not reported Age not reported |

|

| Interventions | A. Codeine 60 mg, n = 374 Placebo, n = 373 B. Codeine 60 mg, n = 275 Placebo, n = 283 |

|

| Outcomes | Number of participants with ≥50% pain relief over 6 h | |

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1. Total = 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | "computerised random number generation" |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | identical or double dummy (from individual reports) |

Sunshine 1983.

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, 3 parallel groups. Single oral dose Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 mins, then hourly to 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Various surgical procedures including cholecystectomy, appendectomy, gynaecological operations, Cesarian section N = 120 M = 23, F = 97 Mean age 23 years |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 40 Propiram fumarate 50 mg, n = 41 Placebo, n = 39 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R2, DB2, W1. Total = 5 Rescue medication allowed after 1 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | "randomized by a computer programme" |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Capsule "was identical in appearance and packaging" |

Sunshine 1987.

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, 5 parallel groups. Single oral dose Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 mins, then hourly to 4 hours |

|

| Participants | Episiotomy, Cesarian section or gynaecological operations N = 195 All F Mean age 26 years |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 37 Ibuprofen 40mg, n = 38 Ibuprofen + Codeine 400/60 mg, n = 40 Ibuprofen + Codeine 200/30 mg, n = 40 Placebo, n = 40 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4 Rescue medication allowed after 1 hour |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | "All unit doses were identical in appearance and packaging" |

Sunshine 1988.

| Methods | Study 1. Randomised, double blind, 3 parallel groups. Single oral dose Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 mins, then hourly to 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Various surgical procedures including cholecystectomy, appendectomy and gynaecological operations N = 151 M = 6, F = 145 Mean age 39 years |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 51 Piroxicam 20 mg, n = 50 Placebo, n = 50 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 3 Rescue medication available on request |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described |

van Steenberghe 1986.

| Methods | Study 1. Randomised, double blind, 5 parallel groups. Single oral dose Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 mins, then hourly to 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Oral surgery on the periodontium N = 73 M 43, F 36 Mean age 40 years |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 20 Ciramadol 15 mg, n = 13 Ciramadol 30 mg, n = 15 Ciramadol 60 mg, n = 20 Placebo, n = 15 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 10 cm VAS, but baseline pain not reported using this scale Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1. Total = 3 No details about timing of rescue medication |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described |

Yonkeura 1987.

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, 4 parallel groups. Single and multiple oral dose phases Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 30, 60 mins, then hourly to 6 hours |

|

| Participants | Episiotomy N = 218 All F Mean age 24 years |

|

| Interventions | Codeine 60 mg, n = 53 Meclofenamate 100 mg, n = 55 Meclofenamate 200 mg, n = 55 Placebo, n = 52 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: standard 4 point scale PR: standard 5 point scale Use of rescue medication Adverse events Withdrawals |

|

| Notes | Oxford Qualtiy Score: R1, DB2, W1. Total = 4 Rescue medication allowed after 1 hour |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | "identically appearing capsules" |

DB ‐ double blind, N ‐ number of participants in study, n ‐ number of participants in treatment arm, PGE ‐ patient global evaluation, PI ‐ pain intensity, PR ‐ pain relief, R ‐ randomised, W ‐ withdrawals h ‐ hours, pts ‐ participants, mins ‐ minutes

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Brunelle 1988 | Not specifically described as randomised |

| Coutinho 1976 | Included participants with mild baseline pain |

| Gleason 1987 | Included participants who had taken a single dose of rescue medication in efficacy analysis |

| Offen 1985 | No separate results for studies without uterine cramping |

| Petersen 1978 | Study medication administered preoperatively |

Differences between protocol and review

The search terms for codeine have been narrowed to exclude codeine derivatives, which are not considered in this review.

Contributions of authors

All review authors contributed to the writing of the protocol. SD and RAM carried out searches and data extraction. All authors were involved with analysis and writing. HJM acted as arbitrator.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Oxford Pain Research funds, UK.

External sources