Abstract

Background

An earlier Cochrane review of dietary advice identified insufficient evidence to assess effects of reduced salt intake on mortality or cardiovascular events.

Objectives

To assess the long term effects of interventions aimed at reducing dietary salt on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity.

To investigate whether blood pressure reduction is an explanatory factor in any effect of such dietary interventions on mortality and cardiovascular outcomes.

Search methods

The Cochrane Library (CENTRAL, Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effect (DARE)), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and PsycInfo were searched through to October 2008. References of included studies and reviews were also checked. No language restrictions were applied.

Selection criteria

Trials fulfilled the following criteria: (1) randomised with follow up of at least six-months, (2) intervention was reduced dietary salt (restricted salt dietary intervention or advice to reduce salt intake), (3) adults, (4) mortality or cardiovascular morbidity data was available. Two reviewers independently assessed whether studies met these criteria.

Data collection and analysis

Data extraction and study validity were compiled by a single reviewer, and checked by a second. Authors were contacted where possible to obtain missing information. Events were extracted and relative risks (RRs) and 95% CIs calculated.

Main results

Six studies (including 6,489 participants) met the inclusion criteria - three in normotensives (n=3518), two in hypertensives (n=758), and one in a mixed population of normo- and hypertensives (n=1981) with end of trial follow-up of seven to 36 months and longest observational follow up (after trial end) to 12.7 yrs. Relative risks for all cause mortality in normotensives (end of trial RR 0.67, 95% CI: 0.40 to 1.12, 60 deaths; longest follow up RR 0.90, 95% CI: 0.58 to 1.40, 79 deaths) and hypertensives (end of trial RR 0.97, 95% CI: 0.83 to 1.13, 513 deaths; longest follow up RR 0.96, 95% CI; 0.83 to 1.11, 565 deaths) showed no strong evidence of any effect of salt reduction. Cardiovascular morbidity in people with normal blood pressure (longest follow-up RR 0.71, 95% CI: 0.42 to 1.20, 200 events) or raised blood pressure at baseline (end of trial RR 0.84, 95% CI: 0.57 to 1.23, 93 events) also showed no strong evidence of benefit. We found no information on participants health-related quality of life.

Authors’ conclusions

Despite collating more event data than previous systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (665 deaths in some 6,250 participants), there is still insufficient power to exclude clinically important effects of reduced dietary salt on mortality or cardiovascular morbidity in normotensive or hypertensive populations. Our estimates of benefits from dietary salt restriction are consistent with the predicted small effects on clinical events attributable to the small blood pressure reduction achieved.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): *Diet, Sodium-Restricted; Cardiovascular Diseases [mortality; *prevention & control]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Sodium Chloride, Dietary [*administration & dosage]

MeSH check words: Adult, Humans

BACKGROUND

In 2002 it was estimated that nearly 17 million deaths globally per year result from cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Mackay 2004). Data on morbidity is more difficult to collect because there are so many different measures of cardiovascular morbidity. However, in 2002 it was estimated that over 34 million disability adjusted life years (DALYs) are lost each year to CVD in Europe (Allender 2008).

The current public health recommendations in most developed countries are to reduce salt intake by about half, i.e. from approximately 10 to 5 g/day (He 2010; SACN 2003; Whelton 2002).

Data from observational studies have indicated that a high dietary intake of salt is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease (He 2002, He 2010). This was confirmed by a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 prospective studies including 177,000 participants. A high salt intake was associated with a greater risk of stroke (relative risk, 1.23, 95% CI: 1.06 to 1.43) (Starzzullo 2009). However, there was no association between salt intake and all cardiovascular events, and total mortality was not reported. Furthermore, the interpretation of this observational evidence base is complicated by the heterogeneity in estimating sodium intake (diet or urinary salt excretion), types of participants (healthy, hypertensive, obese and non-obese), different end points, and definition of outcomes across studies (Alderman 2010).

The relationship of salt intake to blood pressure is the basis for the belief that restriction in dietary sodium intake will prevent blood pressure related cardiovascular events (Elliot 1996). A number of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials of salt reduction and blood pressure have been undertaken (He 2004; Jurgens 2004). Whilst these analyses consistently report a reduction in the level of blood pressure with reduced salt intake, the level of blood pressure reduction achieved is less impressive in the longer term. The 2004 Cochrane review of dietary salt restriction intervention studies of at least six months duration, found that intensive support and encouragement to reduce salt intake lowered blood pressure at 13 to 60 months but only by a small amount (systolic by 1.1 mm Hg, 95% CI: 1.8 to 0.4, diastolic by 0.6 mm Hg, 95% CI: 1.5 to −0.3) (Hooper 2004). The reduction in blood pressure appeared larger for people with higher blood pressure. A decrease in blood pressure is only important if it results in a decrease in cardiovascular events and deaths. Sustained reductions in mean blood pressure of 2-3 mmHg are necessary for important population reductions in cardiovascular events (Elliot 1991).

Whilst the Cochrane review also sought to assess the impact of dietary salt restriction on mortality and cardiovascular events, across the included 11 RCTs there were only 17 deaths spread evenly across groups and 46 cardiovascular events in the controls compared with 36 in low sodium diet groups. This extremely low number of events substantially limited the ability of this review to detect small to moderate reductions in the risk of cardiovascular events.

Given that the effect of interventions to reduce dietary salt on blood pressure is well established, the primary focus of this review is to confirm whether such changes in diet are associated with improvements in mortality and cardiovascular events.

OBJECTIVES

To assess the long term effects of interventions aimed at reducing dietary salt on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity.

To investigate whether a reduction in blood pressure is an explanatory factor in the effect of such dietary interventions on mortality and cardiovascular outcomes.

Interventions to reduce dietary salt were compared with usual, control or placebo diets, or no intervention.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs; individual or cluster level) with follow up of at least six months. Trials of patients with heart failure were excluded.

Types of participants

Studies of adults (18 years or older), irrespective of gender or ethnicity. Studies of children or pregnant women were excluded.

Types of interventions

The desired intervention was reduced dietary salt and could include studies that involved participants receiving a dietary intervention that restricted salt or studies where the intervention was advice to reduce salt intake. The comparison group could include usual, control or placebo diet, or no intervention.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Mortality (overall and cardiovascular), cardiovascular morbidity (including fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, angina, heart failure, peripheral vascular events, sudden death, revascularisation [coronary artery bypass surgery or angioplasty with or without stenting] and cardiovascular related hospital admissions). Primary outcomes were assessed at study end, and also at the latest trial follow up where participants had been followed observationally after the end of the original trial.

Secondary outcomes

In studies that reported primary outcomes we also sought the following secondary outcomes: systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and urinary salt excretion (or other method of estimation of salt intake) and health related quality of life using a validated outcome measure (e.g. Short Form 36, McHorney 1993).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Randomised controlled trials were identified by searching the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (Issue 4, 2008), MEDLINE (Ovid, 1950 to 29 October 2008), EMBASE (Ovid, 1980 to 30 October 2008), CINAHL (Ovid, 2001 to 3 November 2008), and PsycINFO (Ovid, 1806 to October 2008), Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) databases were searched via The Cochrane Library (Issue 4, 2008). Searches conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO included a controlled trials filter. Additional filters were applied to restrict searches to non-animal studies in MEDLINE and EMBASE and to exclude certain publication types from the search results [Medline: case reports/letters, EMBASE: letters/editorials, and PsycInfo: editorials/letters]. No language or additional limits or filters were utilized. See Appendix 1 for details of the search strategies.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of all eligible trials and relevant systematic reviews were searched for additional studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The titles and abstracts of studies identified by the search were independently screened by two reviewers (KA & RST) and clearly irrelevant studies discarded. In order to be selected, abstracts had to clearly identify the study design, an appropriate population and a relevant intervention/exposure, as described above. The full text reports of all potentially relevant studies were obtained and assessed independently for eligibility, based on the defined inclusion criteria, by two reviewers (KA & RST). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or where agreement could not be reached, by consultation with an independent third person (LH).

Data extraction and management

Standardised data extraction forms were used. Relevant data regarding inclusion criteria (study design, participants, intervention/exposure, and outcomes), risk of bias (see below) and outcome data were extracted. Data extraction was carried out by a single reviewer (KA or RST) and checked by a second reviewer (RST or KA). Disagreements were resolved by discussion or if necessary by a third reviewer (LH). We extracted outcomes at the latest follow up point within the trial, and also at the latest follow up after the trial where this was available, as we reasoned this would maximise the number of events reported. All included authors were contacted to clarify any missing outcome data or issues of risk of bias assessment.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Factors considered included random sequence generation and allocation concealment, description of drop-outs and withdrawals, blinding (participants, personnel and outcome assessment) and selective outcome reporting. In addition evidence was sought that the groups were balanced at baseline, that intention to treat analysis was undertaken and whether the period over which the salt intervention lasted and follow up of outcome were equivalent. The risk of bias of included studies was assessed by a single reviewer (KA) and checked by a second reviewer (RST). Disagreements were resolved by discussion or if necessary by a third reviewer (LH).

Data synthesis

Data were processed as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2009). For mortality and cardiovascular events, risk ratio and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each trial. For blood pressure and urinary sodium excretion, mean group differences and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using weighted mean difference. Heterogeneity amongst included studies was explored qualitatively (by comparing the characteristics of included studies), and quantitatively (using the Chi2 statistic of heterogeneity and I2 statistic). Results from included studies were combined for each outcome to give an overall estimate of treatment effect at the latest point available within the randomised trial, and, as a secondary analysis, at the latest point available (including where participants were followed after the end of the randomisation period). A fixed-effect meta-analysis was used except where statistical heterogeneity (Chi2 P ≤ 0.05 and I2 value ≥ 50%) was identified, in which case methodological and clinical reasons for heterogeneity were considered and a random-effects model was used.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

It was planned to use stratified meta-analysis to explore the differential effects that occur as a result of: individual advice vs. population level interventions, baseline risk of cardiovascualr disease (CVD), and salt reduction only interventions vs. multi-component dietary interventions that include salt restriction; and meta-regression to assess the effects of level of salt reduction achieved, baseline blood pressure (BP) and change in BP on mortality and CV event outcomes.

RESULTS

Description of studies

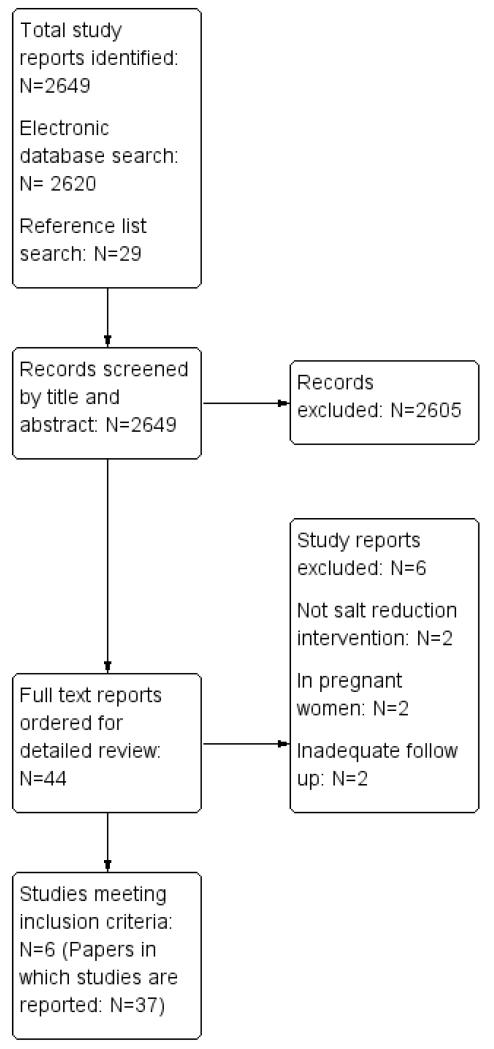

Our electronic and reference list searches identified a total of 2,649 titles of which 2,605 were excluded on title and abstract. After examining the full texts of the remaining 44 papers, six trials were included (37 reports) (Chang 2006; HPT 1989; Morgan 1978 [7-71 mo];TOHP I 1992 [18 mo]; TOHP II 1997; TONE 1998). The study selection process is summarised in the flow diagram shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram

Five studies from an earlier Cochrane review (Hooper 2004) met the inclusion criteria (TOHP I 1992 [18 mo]; TOHP II 1997; TONE 1998; HPT 1989; Morgan 1978 [7-71 mo]). The other six included studies from Hooper 2004 were excluded as they did not report mortality or cardiovascular events (Alli 1992; Arroll 1995; Costa 1981; Morgan 1987; Silman 1983; Thaler 1982). Studies that were assessed in full text, but excluded, are listed in Characteristics of excluded studies section.

Responses to our request for additional details were obtained from three of the included trial authors i.e. TOHP I and II and TONE.

Included studies

The six included studies are described in Characteristics of excluded studies section. Three trials in people with normotension (n=3518, HPT 1989; TOHP I 1992 [18 mo]; TOHP II 1997), two in people with hypertension (n=758, Morgan 1978 [7-71 mo]; TONE 1998), and one in a mixed population of people with normo- and hypertension (n=1981, Chang 2006) were included. Post-randomisation follow up varied from up to six to nine months (Morgan 1978 [7-71 mo]) to ~three-years (Chang 2006; HPT 1989 [36 mo]) and 10-15 years (TOHP I 1992 [18 mo]; TOHP II 1997; TONE 1998).

The three normotensive trials were in healthy people (predominantly [>75%] white, male [75%], median age 40) conducted in the USA. Entry criteria varied between trials, but included those with diastolic blood pressure from 78 to 89 mmHg, with a narrow range of means from 83 to 86 mmHg diastolic and 124 to 127 mmHg systolic and the number of participants included ranged from 392 to 2382.

All three studies (as well as TONE, below) in normotensives aimed to reduce salt by a comprehensive dietary and behaviour change programmes led by experienced personnel, including group counselling sessions, regularly over several months, with newsletters between sessions, self assessment, goal setting, food tasting and recipes. For example, the HPT study ran ten weekly group counselling sessions on food selection, food preparation and behaviour management skills, followed by semi-monthly and then bi-monthly meetings throughout the trial (with newsletters in the months where no meetings occurred). Sessions were run by nutritionists and behavioural scientists and individual counselling was provided where participants missed sessions or had special needs. Techniques used in the sessions included group discussions, instructions for dietary record keeping, goal setting, individual diet analysis for each participant, cooking demonstrations, provision of recipe books and tasting of new foods. The intervention duration ranged from seven months in the TONE study to some 36 months in TOHP II study. Control groups received no active intervention. Sodium excretion goals were set at less than 70 to 80mmol/24 hours.

The three trials that included hypertensives included one trial in treated hypertensive participants (TONE 1998) and two for participants with untreated hypertension (Chang 2006; Morgan 1978 [7-71 mo]). Some 40 percent of participants in the Chang study were defined as hypertensive. Studies were carried out in Australia, Taiwan and USA and ranged in size from 77 to 1,981 participants. 58 to 100% of participants were male with median age of 66 yrs and 76% were white in the TONE study and 100% were Asian in the Chang study (ethnicity was not reported in Morgan study). At study entry mean diastolic blood pressure ranged from 71 mmHg (Chang 2006; TONE 1998 on treatment) to 97 mmHg (Morgan 1978 [7-71 mo], untreated) and systolic blood pressure ranged from approximately 131mmHg (Chang 2006 untreated; TONE 1998 on treatment) to 162 mmHg (Morgan 1978 [7-71 mo], untreated).

Interventions in the three studies included:

a dietary programme by the cook of the kitchen to which they were assigned (clustered random allocation), to ‘high potassium salt’ containing 49% sodium chloride, 49% potassium chloride, and 2% other additives or control prepared diet using ‘usual salt’ containing 99.6% sodium chloride and 0.4% other additives (Chang 2006).

advice to reduce dietary sodium chloride intake, with advice repeated at 6 months compared with no dietary intervention in the control group (Morgan 1978 [7-71 mo]). Anti-hypertensive medication was stopped two months after randomisation to intervention or control, but restarted if diastolic blood pressure rose. After 6 months, four out of 10 men on low sodium diet were taking anti-hypertensive medication, compared to nine of the ten controls (relative risk: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.20 to 0.98).

a four-month ‘intensive’ plus three-month ‘extended’ individual nutrition and behavioural counselling programme (as above) or no such programme but with invitations to meetings on unrelated topics in the control group (TONE 1998). In the TONE study hypertensive medication withdrawal could be attempted began at three-months post randomisation. The primary composite outcome (high blood pressure at any visit, restarting anti-hypertensive medication or a cardiovascular event) was less common in the sodium reduction group than control (relative risk 0.83, 95% CI: 0.75 to 0.92). The proportions of individuals restarting medication was not separately reported.

Sodium goals varied from <80 mmol/day (TONE 1998) to 70-100 mmol/day and unspecified (Chang 2006) sodium intake.

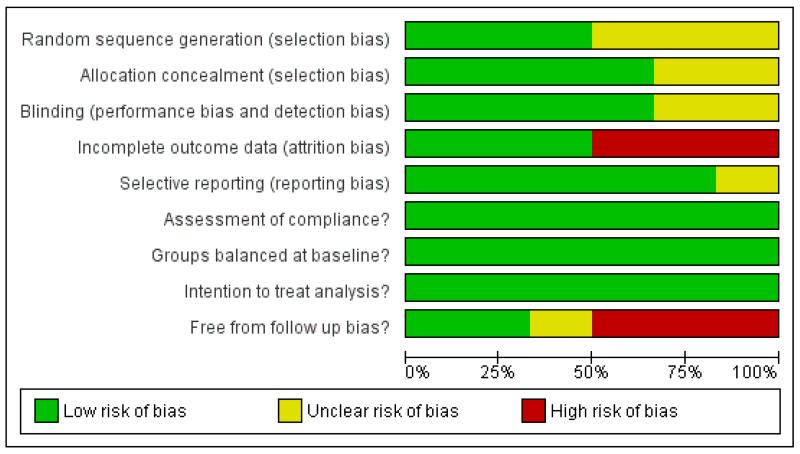

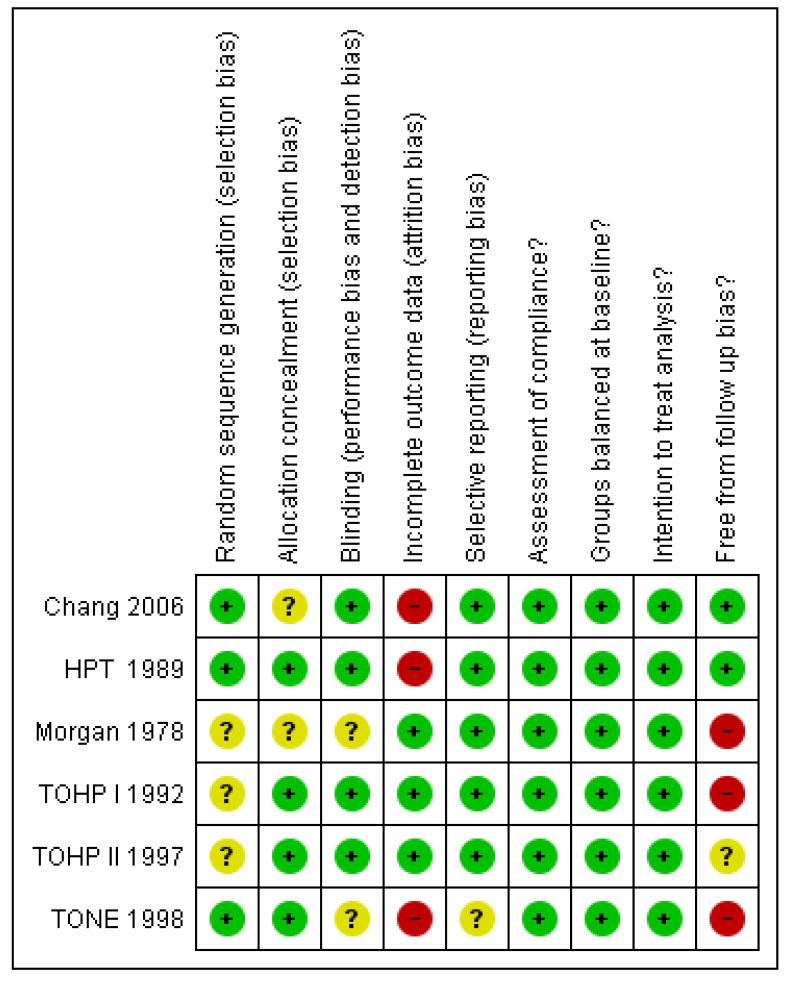

Risk of bias in included studies

A number of studies failed to give sufficient detail to assess their potential risk of bias. Details of generation and concealment of random allocation sequence were particularly poorly reported (Figure 2; Figure 3). However, in all cases there was objective evidence of balance in baseline characteristics of intervention and control participants. While studies reported loss to follow up and reasons for loss for follow, only a few undertook a sensitivity or imputation analysis to assess the impact of these losses, followed up participants for event outcomes and described reasons for loss to follow up for other outcomes. In the TONE trial, the authors stated that data were collected via psychological questionnaires at randomisation and a number of the follow-up visits. However, none of these data were found in trial reports. Although often not stated, all studies appeared to undertake an intention to treat analysis in that groups were analysed according to initial random allocation. All studies assessed compliance to salt reduction intervention using diet diaries or monitoring USE. However, in the longer term follow up of the TOHP I (11.5 yrs), TOHP II (8 yrs) and TONE (12.7 yrs) trials such compliance data was not reported beyond the official end of the study. Therefore it was unclear whether intervention groups encouraged to continue their low salt diets, or return to their pre-trial diet. Similarly, control groups may have been left to continue with their usual diet or advised to reduce their salt at the end of the trial.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

Given the heterogeneity in populations, results are presented and pooled separately for studies of people with normotension and hypertension. Outcomes were pooled at end of trial and at longest follow up point unless otherwise indicated.

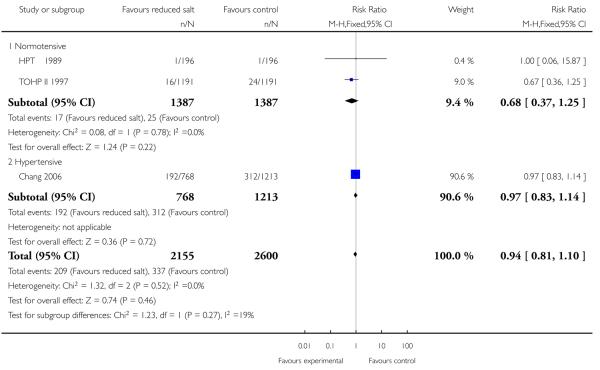

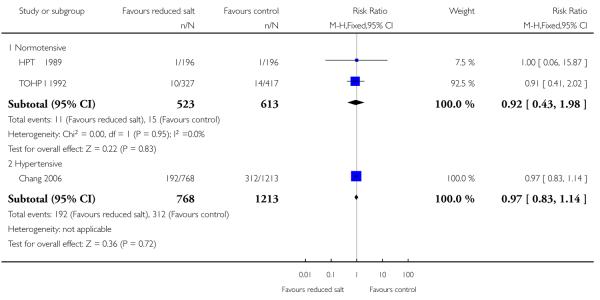

Mortality

All cause mortality was reported at the end of the trial in five of the included studies (HPT 1989; TOHP I 1992; TOHP II 1997; Chang 2008; Morgan 1978). Trials were homogeneous and therefore pooled using a fixed effect model. There was weak evidence of a reduction in the number of deaths in the reduced salt group relative to controls for normotensives (fixed effects RR 0.67, 95% CI: 0.40 to 1.12, 60 deaths in total, Chi2 p-value=0.96,I2 = 0%) and hypertensive populations (fixed effects RR 0.97, 95% CI: 0.83 to 1.13, 513 deaths, Chi2 p-value = 0.98, I2 = 0%). See Analysis 1.1 A longer observational follow up following the end of the randomised trial period was reported for the TOHP I (11.5 yrs) and TOHP II (8 yrs) trials (Cook 2007) and we were able to obtain longer observational unpublished data from the authors from the TONE study (12.7 yrs). Trials remained homogeneous. At longest follow up, there was still no strong evidence of a reduction in the number of deaths in the reduced salt group relative to controls, for the normotensives (fixed effects RR 0.90, 95% CI: 0.58 to 1.40, 79 deaths in total, Chi2 p-value=1.00,I2 = 0%) or hypertensive populations (fixed effects RR 0.96, 95% CI: 0.83 to 1.11, 565 deaths, Chi2 p-value = 0.92); I2 = 0%). See Analysis 1.2

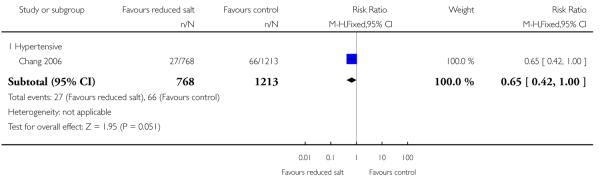

Cardiovascular mortality was only reported in two studies of hypertensive patients. Both studies only reported trial end data. Chang reported a lower proportion of cardiovascular deaths in reduced salt group (27 died; 1310.0 per 100,000 person years) than in the control group (66 died; 2,140 per 100,000 person years). Morgan reported only five cardiovascular deaths, three in the intervention and two in control group. The pooled relative risk was consistent with a halving of the relative risk of cardiovascular deaths or a small increase (fixed effects RR 0.69, 95% CI: 0.45 to 1.05, 98 cardiovascular deaths, Chi2 p-value = 0.26, I2 = 0%). See Analysis 1.3

Cardiovascular morbidity

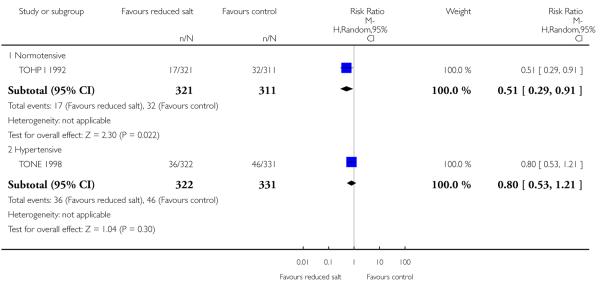

Overall cardiovascular morbidity was available for four trials. There was some evidence of statistical heterogeneity which may reflect that the definition of CV morbidity varied from trial to trial, although it broadly consisted of a composite of myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary artery bypass, PTCA, or death from a cardiovascular cause. At longer term observational follow up, TOHP I reported a relative risk reduction of cardiovascular events of 49% (95% CI: 9% to 71%) with reduced salt although when pooled with long term observational follow up of TOHP II there was no strong evidence of benefit in normotensive participants (random effects relative risk: 0.71, 95% CI: 0.42 to 1.20, 200 events, Chi2 p-value = 0.10; I2 = 63%). There were no reports of cardiovascular morbidity during or at the end of the randomised period for TOHP I or II trials. We found no strong evidence of benefits of salt reduction in hypertensive individuals (fixed effects relative risk: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.57 to 1.24, 93 events, Chi2 p-value = 0.53; I2 = 0%) at end of trial. See Analysis 1.4

Individual cardiovascular morbidity outcomes were infrequently reported and at trial end only. In TONE, three patients experienced strokes (one intervention, two control); six experienced a myocardial infarction (two intervention, four control); three developed heart failure (two intervention, one control) and 26 suffered from angina (nine intervention, 17 control) (TONE 1998).

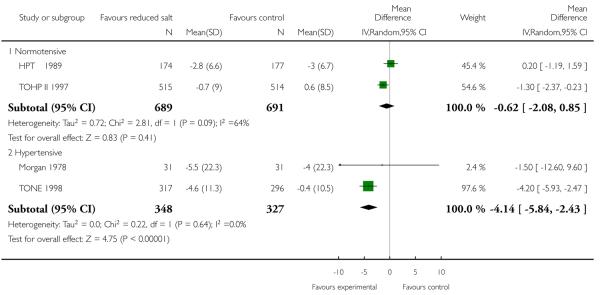

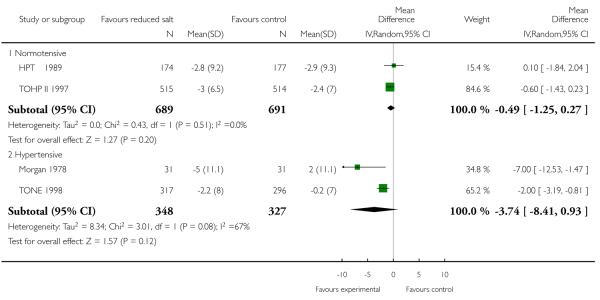

Blood pressure

End of trial blood pressure was reported by all studies. There was evidence of substantial statistical heterogeneity. Systolic blood pressure was reduced in all intervention arms - normotensives (random effects mean difference 1.1 mmHg, 95% CI -0.1 to 2.3, Chi2 p-value = 0.05, I2 = 67%), hypertensives (fixed effect mean difference 4.1 mmHg, 95% CI 2.4 to 5.8, Chi2 p-value = 0.64; I2 = 0%) and those with heart failure (by 4.0 mmHg, 95% CI 0.7 to 7.3). Diastolic blood pressure was also reduced in normotensives (fixed effect mean difference 0.8 mmHg, 95% CI 0.2 to 1.4, Chi2 p-value = 0.39); I2 = 0%) but not in hypertensives (random effect mean difference −3.7 mmHg, 95% CI: 0.9 to −8.4, Chi2 p-value = 0.08; I2 = 67%) or those with heart failure (mean difference −2.0 mmHg, 0.70 to −4.80). See Analysis 1.5 and Analysis 1.6.

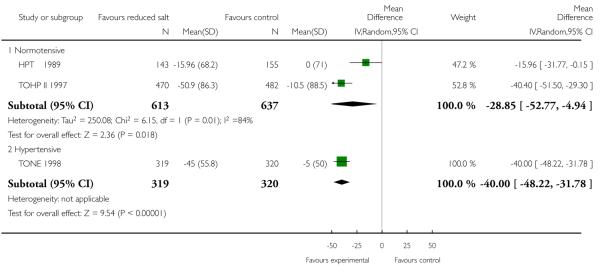

Urinary sodium excretion

Changes in urinary sodium excretion (USE) at the end of trial were reported by all studies. There was some evidence of statistical heterogeneity which may reflect different approaches to the assessment of 24-hr urinary sodium excretion. In the study by Morgan (Morgan 1978 [7-71 mo]), results were only reported as samples and therefore contained repeated observations for a number of patients. As for BP, in a number of studies, the last USE available was at a time point much preceding the timing of the reported mortality or CV events (BP follow up time: Morgan - six mo; TONE −30 mo, TOHP I −18 mo, TOHP II −36 mo). Urinary 24-hour USE was reduced by a similar amount across the three study subgroups - normotensives (by random effects 34.2 mmol/24 hrs, 95% CI: 18.8 to 49.6, Chi2 p-value = 0.03, I2 = 76%), and hypertensive (by fixed effects 39.1 mmol/24 hrs, 95% CI: 31.1 to 47.1, Chi2 p-value = 0.35; I2 = 0%). See Analysis 1.7

Health-related quality of life

No studies reported outcomes using a validated health-related quality of life instrument.

Subgroup analyses and investigation of heterogeneity

In order to take to take account of the heterogeneity in populations and CV baseline risk, we stratified meta-analyses according to whether studies were undertaken in normotensive or hypertensive populations. However, there was insufficient variability and number of studies to formally investigate heterogeneity. For example, as all studies applied participant level salt reduction interventions, we were unable to compare the effect of individual vs. population level interventions.

Small study bias

Given the small number of included studies it was not possible to assess small study bias using either funnel plot or statistically.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

This Cochrane review identified six randomised controlled trials that assessed the long-term (> six-months) effects of interventions aimed at reducing dietary salt on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity. Three trials were in normotensives (HPT 1989 [36 mo], TOHP I 1992 [18 mo]; TOHP II 1997, n=3518 participants), two in hypertensives (Morgan 1978 [7-71 mo]; TONE 1998, n= 758 participants),and one in a mixed population of normo- and hypertensives (Chang 2006, n=1981 participants).

We found no strong evidence that salt reduction reduced all-cause mortality in normotensives (end of trial RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.12, 60 deaths, 3518 participants; longest follow up - relative risk: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.58 to 1.40, 79 deaths, 3518 participants) or hypertensives (end of trial - relative risk: 0.97, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.13, 513 deaths, 2058 participants; longest follow up - relative risk: 0.96, 95% CI; 0.83 to 1.11, 565 deaths, 2349 participants). Few cardiovascular events were reported, and the lack of a statistically significant effect of reduced salt on cardiovascular morbidity in people with normal blood pressure (end of trial - relative risk: 0.71, 95% CI: 0.42 to 1.20, 200 events, 2502 participants) and high blood pressure (end of trial - relative risk: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.57 to 1.23, 93 events, 720 participants). We found no information on participant’s health-related quality of life assessed using either validated generic or disease-specific instruments.

The interventions were capable of reducing urinary sodium excretion and indicated that participants continued to comply with sodium restriction in the long-term, at least to some degree, although, as noted in a previous Cochrane review, the degree of sodium restriction is likely to attenuate over time (Hooper 2004). End of trial systolic and diastolic blood pressure were reduced by an average of some 1 mmHg in normotensives and by an average of 2 to 4 mmHg in hypertensives and those with heart failure. Sustained long-term reductions of blood pressure of 1 and 4 mmHg would be predicted to reduce CVD mortality by 5% and 20% respectively (MacMahon 1990). Our point estimates are consistent with effects of this size but have wide confidence intervals owing to the relatively small number of events.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

A previous Cochrane review was limited by the lack of reported events (17 deaths, 93 cardiovascular events) (Hooper 2004). In this review, because of longer observational follow up (up to 10 to 15-years) of three of the trials included in the previous Cochrane review (TOHP I 1992; TOHP II 1997 [8 yrs]; TONE 1998 [12.7 yrs]) and inclusion of one more recent RCT (Chang 2006; Chang 2006) we have gathered more evidence on mortality and cardiovascular outcomes (~6,270 participants, 644 deaths, 293 cardiovascular events). Nevertheless the total amount of evidence on events remains limited. Assuming a control risk of 14% (hypertension trial control event risk in present review) we would require some 2500 cardiovascular events in over 18,000 trial participants to detect a small reduction in relative risk (0.90) with dietary salt advice (at 80% power and 5% alpha).

Although a relatively small evidence base, the external validity of the review was potentially high. Most studies included men and women at varying levels of risk of cardiovascular risk, primarily free-living in a community setting in industrialised countries. One study was undertaken in veterans in a residential setting in Taiwan, a middle income country (Chang 2006).

Quality of the evidence

Although all included studies were randomised controlled trials, only one of the six included studies provided sufficient detail to be judged as having adequate random sequence generation, allocation concealment and outcome blinding. Nevertheless, all trials provided evidence of baseline balance. Although lack of blinding is unlikely to alter outcome assessment when outcomes include mortality and cardiovascular events, failure to blind participants may have lead to a positive change the lifestyle and dietary behaviours of control participants, leading to a reduction in the difference between groups.

Most trials appeared to be free from dietary changes in the intervention and control group apart from dietary sodium. The one major exception was the trial by Chang where sodium was replaced by a high potassium substitute (Chang 2006). Potassium has effects on blood pressure and may have deleterious effects in individuals with renal disease (Cappuccio 2000). Two studies in hypertensives allowed changes in anti-hypertensive medication during the period of the trial (Morgan 1978 [7-71 mo]; TONE 1998). In both trials, lower levels of hypertensive medication in the intervention group compared to control may have reduced the blood pressure lowering effect of reduced dietary sodium and therefore offset mortality and cardiovascular morbidity benefits.

By incorporating data from the longest follow up point, we sought to maximise the opportunity to capture all deaths and cardiovascular events that were affected by alterations in dietary salt, not just those within the RCT period. However, in doing so we may have introduced a major source of bias. For three large studies (TOHP I 1992, TOHP II 1997 [8 yrs], TONE 1998 [12.7 yrs]) the longest follow up was considerably beyond the official end of the trial and therefore observational. It was unclear if the intervention groups continued their low salt diets and whether control groups were left to continue with dietary advice or advised to reduce their salt. For this reason we included the primary analysis in each case as the latest data trial end, more robust but with slightly fewer deaths and cardiovascular events.

In summary, the overall internal validity of the evidence base in this review was limited and therefore our conclusions regarding the effect of a reduction in dietary salt may not be robust.

Potential biases in the review process

We searched comprehensively for randomised controlled trials of dietary sodium reduction, with a duration of 6-months or more and that reported mortality or cardiovascular events. We attempted to contact all authors of included studies to verify events. Never-theless, we were unable to report all relevant outcomes for all trials. The small number of included studies prevented us from being able to assess the presence of small study or publication bias.

In common with previous systematic reviews of dietary interventions, we observed marked heterogeneity across studies in terms of their population, sample size and follow up. Whilst we stratified meta-analysis by differing sub-populations (normotensives and hypertensives) and pooled studies using weighting based on sample size we did not account for the duration of follow up. A previous Cochrane review (Hooper 2004) suggests that over time the sodium reduction achieved is greatly reduced, as is the effect on blood pressure and therefore the effect on events potentially diminished.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Our finding of a lack of strong evidence of an effect of dietary sodium reduction on mortality and cardiovascular events is in contrast to Starzzullo 2009 who systematically reviewed prospective observational studies that examined the relationship between dietary sodium and cardiovascular events. They included 13 cohort studies (177,025 participants) over follow up three-17 years and found higher salt intake to be associated with greater risk of stroke (pooled relative risk: 1.23, 95% CI: 1.06 to 1.43, 5161 events) and cardiovascular events (pooled relative risk: 1.14, 95% CI: 0.99 to 1.32, 5346 events). Total and cardiovascular mortality were not reported. The inherent limitation of the Starzzullo review is the observational nature of the evidence i.e. studies describe the life course of persons who follow a self-selected diet unlike in randomized trials where allocation is at random and not self-selected. People who choose a lower salt diet are likely to also eat a diet of fresh foods, lower in fats and refined carbohydrate, take more exercise and be less likely to smoke, so that their lower levels of deaths and disease may not relate to salt intake at all.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

Our findings are consistent with the belief that salt reduction is beneficial in normotensive and hypertensive people. However, the methods of achieving salt reduction in the trials included in our review, and other systematic reviews, were relatively modest in their impact on sodium excretion and on blood pressure levels, generally required considerable efforts to implement and would not be expected to have major impacts on the burden of CVD. The challenge for clinical and public health practice is to find more effective interventions for reducing salt intake that are both practicable and inexpensive.

Many countries have national authoritative recommendations, often sanctioned by government, that call for reduced dietary sodium. In UK, the National Institute of Health and Clinical Guidance (NICE) has recently called for an acceleration of the reduction in salt in the general population from a maximum intake of 6 g per day per adult by 2015 and 3 g by 2025 (NICE 2010). Despite collating more events than previous systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (644 deaths in almost 7,000 participants) we were unable to demonstrate a robustly estimated effect of reduced dietary salt on mortality or cardiovascular morbidity in normotensive or hypertensive populations. Including a further 79 deaths from long-term observational follow up of three trials did not improve the statistical power of the meta-analysis which is underpowered to assess the likely small relative risk reductions on all-cause mortality or cardiovascular events of dietary salt restriction.

Implications for research

In accord with the research recommendation of a previous Cochrane review, three of the large trials (TOHP I, TOHP II, TONE) have assessed the long-term effects of reduced dietary salt advice on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity. Our findings support the recent call for further rigorous large long-term randomised controlled trials, capable of definitively demonstrating the cardiovascular benefit of dietary salt reduction (Alderman 2010). Such trials need to assess population level interventions that are likely to lead to sustained reductions in salt intake and are commensurate with current public health guidelines. It will be important to evaluate the effects of voluntary salt reductions by food industries as these may hold greater opportunities for practicable and inexpensive means of reducing salt intake in the population at large than focusing on dietary advice for individuals.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Advice to reduce salt consumption for reducing blood pressure; insufficient evidence to confirm predicted reductions in people dying prematurely or suffering cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease includes heart attacks, strokes, and the need for heart surgery and is a major cause of premature death and disability. This review set out to assess whether intensive support and encouragement to cut down on salt in foods reduced the risk of death or cardiovascular disease. This advice did reduce the amount of salt eaten which led to a small reduction in blood pressure by six months. There was not enough information to detect the expected effects on deaths and cardiovascular disease predicted by the blood pressure reductions found. There was limited evidence that dietary advice to reduce salt may increase deaths in people with heart failure. Our review does not mean that asking people to reduce salt should be stopped. People should continue to strive to do this. However, additional measures - reducing the amount of hidden salt in processed foods, for example - will make it much easier for people to stick to a lower salt diet. Further evidence of measures to cut dietary salt is needed from experimental or observational studies of population based interventions to reduce salt in hypertensives or healthy individuals assessing mortality and cardiovascular events.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This review was supported by a UK NIHR Cochrane Collaboration Programme grant ‘Cochrane Heart Public Health and Prevention Reviews’ CPGS10.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

NIHR programme grant, UK.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Cluster RCT [5 kitchens] | |

| Participants |

N Randomised: 1991 (N=768, intervention, 2 kitchens; N=1213 control, 3 kitchens) Baseline Blood Pressure: Int.: SBP mean 131.3 (SD 19.7), DBP mean 71.2 (SD 10.8) ; Ctrl: SBP mean 130.7 (SD 20.4), DBP mean 71.4 (SD 10.8) Case mix: Int.: 40.2% hypertension; Ctrl.: 40.4% hypertension Age: mean 75.6 (SD 7.7), 74.8 (7.0), 74.8 (7.3), 74.6 (6.7), 74.6 (6.1) in kitchens 2 and 3 (int. group), and 1, 4, and 5 (ctrl group) respectively CV diagnoses: None reported Percentage male: 100% Percentage white: Not reported. Inclusion/exclusion criteria: Inclusion: Veterans registered into a retired home in Northern Taiwan. Exclusion: Bed-ridden veterans, high serum creatinine (i.e. >=3.5mg/dL) |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention Total duration: Average of 31 months. Salt reduction/advice component: Ate food prepared by the cook of the kitchen to which they were assigned, using salt containing 49% sodium chloride, 49% potassium chloride, and 2% other additives. The ’potassium enriched salt’ replaced the regular salt in the selected kitchens in a gradual manner. It was mixed with regular salt in a 1:3 ratio for the first week, it was then increased to 1:1 for the second week, and 3:1 for the third week. By the fourth week cooks used solely the potassium enriched salt Other dietary component: Other condiments and spices such as soy sauce and monosodium glutamate were not limited because reasonably priced low-sodium soy sauce and monosodium glutamate were not available at the time of the trial Comparator Dietary: Ate food prepared by the cook of the kitchen to which they were assigned using ’regular salt’ containing 99.6% sodium chloride and 0.4% other additives at all times. Other condiments and spices such as soy sauce and monosodium glutamate were not limited because reasonably priced low-sodium soy sauce and monosodium glutamate were not available at the time of the trial |

|

| Outcomes | Deaths (all cause & CVD) | |

| Follow up | Average 31 months | |

| Country & setting | Taiwan - Veteran’s retirement home | |

| Notes | Outcomes are not reported by kitchen so not able to quantify effect of clustering | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “The simplest randomisation method, i.e., drawing lots, was used.” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “The veterans were told about the trial, but were not told to which salt they were assigned.” Yes - participants. Unclear - study personnel and outcome assessors |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | It appears that all subjects were followed-up for the deaths outcome. A consort diagram and reasons for losses to follow-up for other outcomes are given. No sensitivity analysis or imputation was carried out to assess the impact of missing data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes described in the methods are reported in the results |

| Assessment of compliance? | Low risk | Subjects ate food that was prepared for them. |

| Groups balanced at baseline? | Low risk | “The ages of persons in different kitchens were not significantly [different] at entry (P=0.24). The results also indicated that weight, height, body mass index, blood pressure, and electrolytes for a subsamples of persons in the experimental and control groups were not significantly different at baseline. Persons in [the experimental kitchens] had slightly longer follow-up times than did their counterparts [in the control kitchens]; however, the difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.11). ” |

| Intention to treat analysis? | Low risk | Not specifically reported, but on the basis of the consort diagram, subjects did appear to be analysed according to the groups to which they were originally allocated |

| Free from follow up bias? | Low risk | The dietary intervention was applied over the period of event outcome follow up |

| Methods | Individual RCT | |

| Participants |

N Randomised: 392 (N=196, intervention, N=196, control) Baseline Blood Pressure: Int.: SBP mean124.0 (SD NR), DBP mean 82.6 (SD NR); Ctrl: mean SBP 123.9(SD NR), DBP mean 83.0 (SD NR) Case mix: normotensives Age: Int. mean 39.0 (SD NR); Ctrl: mean 38.5 (SD NR) CV diagnoses: none Percentage male:65% Percentage white: 82% Inclusion/exclusion criteria: Inclusion: Men and women aged 25-49yrs; DBP 78-89mmHg Exclusion: Use of antihypertensive medication, evidence of CVD, BMI >=0.0035kg/cm2, dietary requirements incompatible with any of the interventions, drank 21 or more alcoholic drinks per week, pregnant women, unable to comply with the protocol requirements |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention Total duration: 36 months Salt reduction/advice component: Dietary counselling (in groups) aimed at sodium restriction. The groups met once a week for the first 10 weeks, once every two weeks for the next four weeks, and then once every month for the rest of treatment and follow-up. The group goal was a 50% reduction (<= 70mmol) in mean urine sodium. Personnel delivering the interventions were trained and experienced in effecting behaviour change. Counselling included a mixture of didactic presentations and demonstrations, token incentives, telephone calls, and newsletters Other dietary component: none stated Comparator Dietary: no dietary counselling |

|

| Outcomes | BP, Urinary Na excretion, Deaths (all cause) | |

| Follow up | 36 months | |

| Country & setting | US - 4 clinics | |

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “The randomisation procedure involved a fixed assignment ratio design that provided for equal numbers of assignments within clinic and weight strata in blocks (randomly ordered) of size 3, 6, or 9 for the normal weight stratum and of size 5 to 10 for the high-weight stratum. “Randomisations were performed on demand at the individual clinic centers (using a pseudo-random number generator provided with the S/23 BASIC language) with schedules and software for issuing assignments generated by the DCC. ” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “Randomisations were performed on demand at the individual clinic centers (using a pseudo-random number generator provided with the S/23 BASIC language) with schedules and software for issuing assignments generated by the DCC. Clinic personnel had to key all [Baseline 1 and Baseline 2 visit] data and those contained on part I of the [Baseline 3 visit] data before an assignment could be obtained (via the S/23)” |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “In order to reduce observer bias, data collection and treatment visits for dietary counselling were not held in the same week for a given participant, and data collection (i.e., interviews, measurements, food record review, and the like) were carried out by personnel not involved in treatment.” “Participants were asked not to […] divulge or discuss their dietary counselling with data collection personnel. ” No - participants; Yes - data collectors; Unclear - data analysts. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Numbers in each group at each assessment time point were reported. The only reasons given for losses to follow-up were non-attendance at follow-up visits or death. No sensitivity analysis or imputation undertaken to assess impact of loss to follow-up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes described in methods are reported in results. |

| Assessment of compliance? | Low risk | “Attendance during the first 12 counselling sessions ranged from a high of 86.5% for the Na treatment group in the sodium-calorie component at session 1 to a low of 46.8% for that same treatment group at session 12. Attendance for all counselling groups declined with time (test for linear decline, P<.001). Generally, attendance over the 12 sessions was better for the two treatment groups involving calorie restriction […] than for the other two dietary treatment groups [including the sodium reduction group]. ” “For the purposes of this article, we use progress toward or attainment of dietary treatment goals as indices of compliance. [[…] As a first level of exploratory analysis, univariate and multiple linear regressions were conducted comparing 34 baseline and process variables with urine sodium excretion [.…] as [one of the] dependent variables. [.[…]In the second level of analysis, compliance was definedin terms of achieving treatment goals. For the sodium reduction groups, compliance was defined as having a 24-hr urine excretion of less than or equal to 70mEq. ” |

| Groups balanced at baseline? | Low risk | “Except for sex there were no marked baseline differences among the treatment groups. ” |

| Intention to treat analysis? | Low risk | “All results are presented by original treatment assignment. ” |

| Free from follow up bias? | Low risk | Duration of intervention same as follow up time for event outcomes |

| Methods | Individual RCT | |

| Participants |

N Randomised: 77 (N=35 intervention N=42 control) groups Baseline Blood Pressure: Int: SBP mean 160 (SD 23), DBP 97 (SD 8); Ctrl: SBP mean 165 (SD 17), DBP mean 97 (SD 8) Case mix: Untreated hypertensives Age: Int. mean: 57.1 (SD NR); Ctrl. mean: 58.6 (SD NR) CV diagnoses: Borderline hypertensives (DBP = 95-109) Percentage male: 100% Percentage white: not reported Inclusion/exclusion criteria: Inclusion: Males with borderline hypertension on admission to hospital or outpatient visit Exclusion: Malignant disease, severe psychiatric disturbances, severe physical incapacity or a disease likely to be fatal in the next two years, serum-creatinine levels >0.18mmol/l, abnormal liver-function tests, in cardiac failure or on diuretic therapy |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention Total duration:6 months Salt reduction/advice component: Patients instructed to reduce their sodium chloride intake and were given a diet that should have reduced their sodium intake to 70-100mmol/day. The advice about diet was repeated at 6mths. No details on who gave advice Other dietary component: At each 6mth review visit, if serum potassium levels <3. 4mmol/L, potassium supplements were given Comparator No treatment reviewed at 6 mo (as intervention) Other: Not given any treatment, but reviewed at six-monthly intervals and if the DBP rose above 115mmHg treatment was started |

|

| Outcomes | Deaths (all cause & CVD); BP; Urinary Na Excretion | |

| Follow up | longest BP at 24 mo | |

| Country & setting | Australia - single hospital | |

| Notes | CV morbidity and CV mortality data taken from previous Cochrane review Taking antihypertensive medication (at 6 mo): Intervention - 4/10 vs Control - 9/10 (RR: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.20 to 0.98) |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “[patients] were randomly divided into 4 subgroups” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “Information regarding life or death was not known for two patients, who were excluded from the study. All patients included in the study were seen at the initial visit, and at a subsequent six-month visit. Patients who did not report back on at least one occasion have not been analysed. Five patients died in the first six months; these have been included in the analysis. There were no other known deaths in this time interval in the patients who did not report back. More than 90% of initially allocated patients reported back at the end of the first six-month period. ” The only reason given for losses to follow-up was patients not reporting back. No sensitivity analysis or imputation undertaken to assess impact of loss to follow-up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes described in the methods are reported at some point in the results |

| Assessment of compliance? | Low risk | Urinary sodium is measured, and although it is not specifically stated that this was used to assess compliance, it is implied: “Patients in the dietary therapy group who continued to have a high sodium excretion were advised about their diet. ” |

| Groups balanced at baseline? | Low risk | “At the start of the study the groups were similar in age, weight, height, pulse-rate, and serum electrolytes, urea, creatinine, uric acid glucose, and cholesterol. The initial systolic and diastolic blood-pressures, supine and standing, did not differ among the groups”. |

| Intention to treat analysis? | Low risk | Although the term ITT is not used by the authors it appears that groups were analysed as randomised “[Morgan et al.’s (1980)] report does not exclude patients who changed therapy or ceased therapy. It evaluates the proposition: ‘Did the decision to implement therapy alter the mortality rate in patients with mild hypertension’?” |

| Free from follow up bias? | High risk | Longest event follow up for mortality was 71 months but last stated diet advice stated as 6 months.No urinary sodium excretion data available at longest follow up |

| Methods | Individual RCT | |

| Participants |

N Randomised: 744 (327 intervention & 417 control) Baseline Blood Pressure: Int: SBP mean 124.8 (SD 8.5), DBP mean 83.7 (SD 2.7); Ctrl: SBP mean 125.1 (SD 8.1), mean DBP 83.9 (SD 2.8) Case mix: Normotensives Age: Int.: 43.4 (SD 6.6); Ctrl.: 42.6 (SD 6.5) CV diagnoses: None Percentage male: 71.4% Percentage white: 77.2% Inclusion/exclusion criteria: Inclusion: aged 30-54: mean DBP 80-89mmHg without antihypertensive medication; ability to complete and return a satisfactory 24-hour urine collection and food frequency questionnaire Exclusion: Long list of exclusion criteria, generally designed to eliminate patients with: evidence of medically diagnosed hypertension (DBP >= 90mmHg or use of BP medications within 2mths of first evaluation), cardiovascular or other life-threatening or disabling diseases, gross obesity (BMI>36.14), a contraindication to any of the phase I interventions, or might have difficulty complying with the treatment or follow-up requirements of the trial |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention Total duration: 18mths Salt reduction/advice component: Dietary and behavioural counselling on how to identify sodium in the diet, self-monitor intake, and select or prepare low sodium foods and condiments suited to personal preferences. Individual and weekly group counselling sessions were provided during the first 3mths, with additional less frequent counselling and support for the remainder of follow-up. Sessions were provided by nutritionists, psychologists, or other experienced counsellors. The objective was to reduce urinary sodium excretion in the intervention group to 80mmol/24h Comparator Dietary: Usual diet. General guidelines for healthy eating were given |

|

| Outcomes | All cause mortality, CV morbidity, BP and 24hr urinary sodium excretion | |

| Follow up | 11.5 years (“additional ~10 yrs observational follow up”) | |

| Country & setting | US - 6 clinics | |

| Notes | TOHP I design included allocation to other interventions (weight loss, stress management & supplements e.g.. fish oil) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “the clinic notified the coordinating center [of participant eligibility] by telephone and obtained a randomisation assignment. Clinics were also provided with sealed envelopes containing randomization assignments for use when telephone contact with the coordinating center was not possible. ” “adherence to the appropriate assignment sequence was monitored by the coordinating center. ” |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “To minimize bias, [BP] observers were blinded to treatment allocation. Persons certified to measure BP were not involved with intervention aspects of the trial, nor were they allowed access to data that would reveal group assignment. When possible, separate facilities or entrances were used for data collection visits as compared to intervention visits.” “In order to reduce observer bias, data collectors were blinded to the treatment assignment of the participants. ” No - participants; Yes - data collectors; Unclear - data analysts |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “In the analyses shown, participants with no follow-up visits […] were assigned a zero value for BP change (“intention-to-treat” analysis). These results did not differ appreciably from those in which missing BP values were treated as missing at random and excluded from the analysis. ” “The effect of missing urinary sodium excretion data at follow-up on estimates of the absolute change from baseline was assessed by assuming no change (the baseline sodium excretion value was imputed). To reduce the likelihood that estimates of treatment group differences were influenced by the inclusion of incomplete samples, mean differences in urinary sodium excretion at 6, 12, and 18 months were recalculated excluding urine values associated with a volume less than 500g or, in separate analyses , associated with creatinine or creatinine per kilogram of body weight less than 85% of the within-person average. Mean treatment group differences with these exclusions were very similar to each other and to those calculated when all samples were included. ” |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes described in methods are reported in results. |

| Assessment of compliance? | Low risk | “Twenty-four-hour urine samples were used to monitor sodium reduction” [.…] In addition, food frequency questionnaire and 24hour dietary recall estimates of sodium intake were obtained from all life-style participants.” “Compliance with the three life-style interventions was satisfactory, both in terms of attendance at counselling sessions and in reaching specific goals. […] The group difference [in urinary Na excretion] was maximal (58mmol/24h) at 6 months, […] the mean reduction [in urinary Na excretion] was well-maintained. ” “The Data Coordinating Center provided guidelines for estimating adherence to the counselling goal of 60mmol sodium /24hr from the average sodium excretion in two 8-hour urine samples collected at least 2 days apart. ” |

| Groups balanced at baseline? | Low risk | “Baseline characteristics were evenly distributed, except for age, which was higher in the sodium reduction intervention group” |

| Intention to treat analysis? | Low risk | “In a sensitivity analysis using logistic regression we performed an intention to treat analysis treating non-responders as non-events Because mortality follow-up was virtually complete, we included all randomised participants in analyses of mortality alone in a full intention to treat analysis. ” |

| Free from follow up bias? | High risk | Longest event follow up for mortality and CV morbidity was ~11.5 years but last stated diet advice stated as 18 months. No urinary sodium excretion data available at longest follow up |

| Methods | Individual RCT | |

| Participants |

N Randomised: 2382 (1191 intervention; 1191 control) Baseline Blood Pressure: Int: mean SBP 127.5 (SD 6.6), DBP mean 86.0 (SD 1.9); Ctrl: SBP mean 127.4 (SD 6.2), DBP SD 85.9 (SD 1.9) Case mix: Normotensives Age: Int.: mean 43.9 (SD 6.2); Ctrl.: mean 43.3 (SD 6.1) CV diagnoses: None Percentage male: 65.7% Percentage white: 79.3% Inclusion/exclusion criteria: Inclusion: 30-54 year old adults with no evidence of medically diagnosed hypertension who were moderately overweight (men: between 26.1-37.4kg/m2; women: between 24.4-37.4kg/m2), and had average DBP between 83-89mmHg, and an SBP <140mmHg. Participants also had to demonstrate compliance with the more difficult data collection tasks Exclusion: Evidence of current hypertension. History of CVD, diabetes mellitus, malignancy other than nonmelanoma skin cancer during the past 5yrs, or any other serious life-threatening illness that requires regular medical treatment. Current use of prescription medications that affect BP, as well as non-prescription diuretics. Serum creatinine level >= 1.7mg/dL for men or 1.5mg/dL for women, or casual serum glucose >=200mg/dL. Current alcohol intake >21 drinks/wk. Pregnancy, or intent to become pregnant during the study. Plans to move or inability to cooperate |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention Total duration: 36 mths Salt reduction/advice component: Individual and weekly group counselling sessions were provided initially followed by additional less intensive counselling and support for the remainder of follow-up. Mini-modules to reinforce the content of the counselling session were offered in the later years of the intervention. The content of sessions included sodium information, self-management and social support components. Sessions were provided by registered dieticians mainly, plus a few psychologists, or other experienced counsellors. The objective was to reduce urinary sodium excretion in the intervention group to 80mmol/24h Other: The salt reduction intervention was combined with a weight loss intervention or alone Comparator Dietary: No advice Other: Usual care or weight loss intervention alone. |

|

| Outcomes | All cause mortality CV morbidity (a composite of myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary revascularisation or CV death), BP, urinary excretion | |

| Follow up | 36 mths | |

| Country & setting | US - 9 clinics | |

| Notes | This study had a 2×2 factorial design in which the groups were: weight loss alone, sodium reduction alone, a combination of weight loss and sodium reduction, and a usual care group. The long term effects of the sodium reduction intervention were analysed by grouping data for the two sodium reduction interventions (alone or with weight loss) and for the two non-sodium reduction groups (usual care and weight loss alone) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “The clinic then notified the coordinating center [of participant eligibility] by telephone and obtained a randomisation assignment. In those cases where random assignment was not done by phone, clinics also were provided with sealed randomization envelopes for use when contact with the coordinating center was not possible. ” |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “With respect to the determination of categorical end points, in order to minimize bias in the ascertainment of hypertension, an Endpoints Subcommittee conducts a blind review of study forms, and as necessary, the medical records of participants who are considered to have had hypertensive events. Potential hypertensive end points identified are either confirmed or refuted by the subcommittee. ” “[Data collectors] were masked to participants’ intervention assignments. ” No - participants; Yes - data collectors; Unclear - data analysts |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “For those with BP measurements but without urinary sodium excretion data at the corresponding follow-up visit, a 0 change in urinary sodium excretion was imputed in a secondary analysis. ” “For the small number of participants with no useable BP readings after randomisation (n=99, of whom 57% were treated early with BP medications by their physicians), measures from a randomly selected participant in the usual care group were imputed under the assumption that having little or no exposure to the intervention programs would produce similar results to that of the usual care group. ” |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes described in methods are reported in results. |

| Assessment of compliance? | Low risk | “Intervention attendance also is collected for participants within each of the active intervention groups. The dietary data are collected on random samples of equal numbers of participants across the treatment groups. The 24-hour urine specimens for sodium, potassium and creatinine measurements are collected from all participants at 18 and 36 months. An additional 24-hour urine specimen, collected on a 25% sample of trial participants at 6 months, was added to more fully assess sodium intakes at this time as compared to baseline levels. ” “Urinary sodium excretion and weight change are collected as intermediate end points for all participants. These intermediate end points were selected to evaluate compliance to specific interventions ” |

| Groups balanced at baseline? | Low risk | “Baseline characteristics were evenly distributed, except for age, which was higher in the sodium reduction intervention group” |

| Intention to treat analysis? | Low risk | “In a sensitivity analysis using logistic regression we performed an intention to treat analysis treating non-responders as non-events. Because mortality follow-up was virtually complete, we included all randomised participants in analyses of mortality alone in a full intention to treat analysis. ” |

| Free from follow up bias? | Unclear risk | Longest event follow up for mortality and CV morbidity was ~8years but last stated diet advice stated as 36 months. No urinary sodium excretion data available at longest follow up |

| Methods | Individual RCT | |

| Participants |

N Randomised: 681 (N=340, intervention & N=341, control) - part of factorial design study Baseline Blood Pressure: SBP 128.0 (9.4), DBP 71.3 (7.3) mm Hg Case mix: Treated hypertensives Age: 65.8 (SD 4.6) CV diagnoses: None Percentage male: 53% Percentage white: 76% Inclusion/exclusion criteria: Inclusion: Healthy, aged 60-80yrs, SBP <145mm Hg &DBP <85mm Hg while taking a single antihypertensive medication or a single combination regimen consisting of a diuretic agent and a non-diuretic agent. Individuals taking two antihypertensive medications were also eligible if they were successfully weaned off one of them during the screening phase. Independencein activities of daily living. Capacity to alter diet and physical activity in accordance with the requirements of any TONE intervention Exclusion: Diagnosis or treatment of cancer within the last 5yrs; treatment with diuretics, ACE-inhibitors, or digitalis for CHF or unknown reason; drug therapy with nitrates, beta blockers, or calcium channel blockers for CHD or reason other than hypertension; MI or stroke within 6mths; “active” CHD (e.g. angina pectoris); CHF; atrial fibrillation; second- or third-degree heart block without permanent pacemaker; drug therapy for ventricular arrhythmias; self-report of heart valve replacement; clinically important valvular heart disease; insulin dependent diabetes mellitus; severe hypertension; current or recent (within 6mths) drug therapy for asthma or chronic obstructive lung disease; use of corticosteroid therapy for >1mth; serious mental or physical illness; unexplained or involuntary weight loss (>=4.5kg) during the previous year; BMI<21 in men or women, or >33 in men or >37 in women; serum creatinine >2mg/dL; non-fasting blood glucose level of >260mg/dL; hyperkalemia (>5.5mmol/L); anaemia (Hb level <110g/L); >14 alcoholic drinks per week (assessed by self-report); severe visual or hearing impairment; other reason making it difficult for the participant to comply fully with any part of the study protocol |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention Total duration: 4mth “intensive” phase, plus 3mth “extended” phase, and then a maintenance phase (duration of this phase is unclear) Salt reduction/advice component: Individual & group sessions with an interventionist (typically a registered dietician) who provided information using both centrally and locally prepared materials, motivated participants to make and sustain long-term lifestyle changes, and frequently monitored progress of groups and individuals. Individualised feedback was provided. Participants learned about sources of sodium, in particular those foods with a high salt content, and they learned about possible alternatives. They also learned how to adapt the recommendations for a low salt diet to their own lifestyle. The goal of this intervention for the group was to achieve and maintain a 24hr dietary sodium intake of 80mmol (1800mg) or less (as measured by 24hr urine collection) Other: Attempt to withdraw hypertensive therapy began 3 months post randomisation Comparator Dietary: In order to enhance retention of control participants, meetings were held on a regular basis with speakers on subjects unrelated to BP, CVD or nutrition Other: Drug withdrawal began at a comparable time to the intervention group |

|

| Outcomes | Mortality (all cause & cardiovascular), cardiovascular morbidity (a composite of myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG)), BP, urinary sodium | |

| Follow up | 30 mo | |

| Country & setting | US - 4 clinical academic centres | |

| Notes | Unpublished all cause mortality data at 12.7 yrs obtained from authors No data specifically reported on number of individuals who stopped antihypertensive medication in 2 groups |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “Overweight participants were randomly assigned, in a 2×2 factorial design […] Nonoverweight participants were randomly assigned[…]” “We used a variable block length randomization algorithm. ” (from investigators) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “Assignments were made via computers at the clinic sites, after eligibility criteria were confirmed. The sequences were concealed from clinic staff only known to statisticians at the coordinating center. ” (from investigators) |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | “To facilitate masking of the data collectors, intervention visits were conducted at separate times and placesfom the data collection visits.” “An endpoint committee, maskedto intervention assignment, made final decisions concerning the endpoint status of each participant. ” “Outcome information was obtained by staff members who were blindto the participants’ intervention assignment, at different times and different locations from those used for the intervention visits. Participants were instructed not to reveal their intervention assignment to the data collection staff. ” “Intervention staff members were masked with respect to the participants’ BP and drug withdrawal status. ” “When questioned at the final follow-up visit, the data collectors guessed the correct treatment assignment in 31% of the obese participants (compared with an expected rate of 25% on the basis of chance) and in 45% of the nonobese participants (compared with and expected rate of50% on the basis of chance). ” No - participants; Yes - data collectors; Unclear - data analysts |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | The only reason given for losses to follow-up was non-attendance at follow-up visits. No sensitivity analysis or imputation undertaken to assess impact of loss to follow-up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | The authors report that data was collected via psychological questionnaires at randomisation and a number of the follow-up visits, but none of the data from these appear to be reported, unless they are in a separate publication. |

| Assessment of compliance? | Low risk | “Monitoring adherence (Reduced sodium life-style): Attendance; urinary data; food and behaviour records; adherence-related incentives. Monitoring adherence (Usual (control) life-style): Attendance. ” |

| Groups balanced at baseline? | Low risk | “There was no evidence of a substantial imbalance between the reduced sodium and UL [usual lifestyle] groups [at baseline]” |

| Intention to treat analysis? | Low risk | “Analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis. ” |

| Free from follow up bias? | High risk | Mortality outcome provided by authors at 12.7 yrs average follow up. No urinary sodium excretion data available at longest follow up |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Bentley 2006 | Inadequate follow up duration |

| Knuist 1998 | Pregnant women |

| Koopman 1997 | No appropriate outcomes |

| Licata 2003 | Not dietary salt reduction intervention |

| van der Post 1997 | Pregnant women |

| Velloso 1991 | Inadequate follow up duration |

DATA AND ANALYSES

Comparison 1. Reduced salt vs control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 All cause mortality at end of trial | 3 | 4755 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.81, 1.10] |

| 1.1 Normotensive | 2 | 2774 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.37, 1.25] |

| 1.2 Hypertensive | 1 | 1981 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.83, 1.14] |

| 2 All cause mortality at longest follow up | 3 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Normotensive | 2 | 1136 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.43, 1.98] |

| 2.2 Hypertensive | 1 | 1981 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.83, 1.14] |

| 3 CV mortality at longest follow up | 1 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Hypertensive | 1 | 1981 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.42, 1.00] |

| 4 CV morbidity at longest follow up | 2 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Normotensive | 1 | 632 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.29, 0.91] |

| 4.2 Hypertensive | 1 | 653 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.53, 1.21] |

| 5 Systolic BP at end of trial | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Normotensive | 2 | 1380 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −0.62 [−2.08, 0.85] |

| 5.2 Hypertensive | 2 | 675 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −4.14 [−5.84, −2.43] |

| 6 Diastolic BP at end of trial | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Normotensive | 2 | 1380 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −0.49 [−1.25, 0.27] |

| 6.2 Hypertensive | 2 | 675 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −3.74 [−8.41, 0.93] |

| 7 Urinary sodium excretion at end of trial | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Normotensive | 2 | 1250 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −28.85 [−52.77, −4.94] |

| 7.2 Hypertensive | 1 | 639 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | −40.0 [−48.22, −31.78] |

Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Reduced salt vs control, Outcome 1 All cause mortality at end of trial.

Review: Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease

Comparison: 1 Reduced salt vs control

Outcome: 1 All cause mortality at end of trial

|

Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Reduced salt vs control, Outcome 2 All cause mortality at longest follow up.

Review: Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease

Comparison: 1 Reduced salt vs control

Outcome: 2 All cause mortality at longest follow up

|

Analysis 1.3. Comparison 1 Reduced salt vs control, Outcome 3 CV mortality at longest follow up.

Review: Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease

Comparison: 1 Reduced salt vs control

Outcome: 3 CV mortality at longest follow up

|

Analysis 1.4. Comparison 1 Reduced salt vs control, Outcome 4 CV morbidity at longest follow up.

Review: Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease

Comparison: 1 Reduced salt vs control

Outcome: 4 CV morbidity at longest follow up

|

Analysis 1.5. Comparison 1 Reduced salt vs control, Outcome 5 Systolic BP at end of trial.

Review: Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease

Comparison: 1 Reduced salt vs control

Outcome: 5 Systolic BP at end of trial

|

Analysis 1.6. Comparison 1 Reduced salt vs control, Outcome 6 Diastolic BP at end of trial.

Review: Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease

Comparison: 1 Reduced salt vs control

Outcome: 6 Diastolic BP at end of trial

|

Analysis 1.7. Comparison 1 Reduced salt vs control, Outcome 7 Urinary sodium excretion at end of trial.

Review: Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease

Comparison: 1 Reduced salt vs control

Outcome: 7 Urinary sodium excretion at end of trial

|

WHAT’S NEW

Last assessed as up-to-date: 1 April 2009.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 June 2013 | Amended | The Paterna trial has now been retracted and data from this trial have been removed from this review |

| 13 March 2013 | Amended | Doubts have been raised about the intergrety of research from the Paterna group. The previously published results should be discounted for now |

HISTORY

Review first published: Issue 7, 2011

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 September 2011 | Amended | Amended Plain Language Summary |

| 6 July 2011 | Amended | Corrected typo error in ’Abstract - Results’ section |

Appendix 1. Search strategies

The Cochrane Library 2008 Issue 4

Results for CENTRAL, Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effect (DARE)