Abstract

Green tea polyphenols are strong antioxidants and can reduce free radical damage. To investigate their neuroprotective potential, we induced oxidative damage in spinal cord neurons using hydrogen peroxide, and applied different concentrations (50–200 μg/mL) of green tea polyphenol to the cell medium for 24 hours. Measurements of superoxide dismutase activity, malondialdehyde content, and expression of apoptosis-related genes and proteins revealed that green tea polyphenol effectively alleviated oxidative stress. Our results indicate that green tea polyphenols play a protective role in spinal cord neurons under oxidative stress.

Keywords: nerve regeneration, spinal cord injury, nerve cells, green tea polyphenols, spinal cord neurons, oxidative stress, apoptosis, malondialdehyde, superoxide dismutase, rats, NSFC grant, neural regeneration

Introduction

Spinal cord injury is a global medical problem, with an estimated incidence of 233–755 cases per million worldwide (Windaele et al., 2006). Spinal cord injuries comprise primary and secondary injuries. The former refers to mechanical injury to the spinal cord, and the latter to a series of pathological changes, such as oxidative stress and release of inflammatory factors, with a complicated pathogenesis. Secondary injury has a severe impact on the functional recovery of the spinal cord (Beattie et al., 2004), and inhibiting its development is critical in treating spinal cord injury. In addition, increasing attention has been paid to reducing a series of cascade reactions triggered by secondary injury. Various factors contribute to the pathological changes that occur in secondary spinal cord injury, such as the inflammatory response, electrolyte disturbances, intracellular calcium overload, cell apoptosis, and the involvement of free radicals and vascular factors. Although the pathophysiological mechanisms of primary and secondary spinal cord injury remain unclear, oxidative stress is known to have an important role (Jia et al., 2012). The generation of reactive oxygen species is a basic response to disease and trauma, but beyond a certain level the body's antioxidant capacity is exceeded, leading to oxidative damage and resulting in the body being subjected to a state of oxidative stress (Campuzano et al., 2011). The damage from oxidative stress caused by reactive oxygen species contributes significantly to secondary injury (Azbill et al., 1997), and antioxidant substances are effective in the treatment of spinal cord injuries (Liu et al., 2011; Sahin et al., 2011; Shaafi et al., 2011; Jia et al., 2012). Oxidative stress and inflammation induce apoptosis of nerve cells and oligodendrocytes, and are the main pathogenic processes leading to spinal cord injury (Yune et al., 2007, 2008). The lipid peroxidation products generated by oxidative stress are able to damage the structure and function of lipid bilayers of cells and organelles (Catala et al., 2011, 2012). One such product, 4-hydroxynonenal, is elevated after spinal cord injury (Carrico et al., 2009). Mitochondria in the spinal cord are highly sensitive to 4-hydroxynonenal, around 10 times more than those in the brain (Vaishnav et al., 2010). However, although the importance of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of spinal cord injury is recognized, no drug as yet is entirely effective against it.

Polyphenols are the main active ingredient in green tea (Cabrera et al., 2006) and have strong free radical scavenging and antioxidant activity (Thielecke et al., 2009). They protect against oxidative stress in a variety of tissues and organs, including bone tissue (Shen et al., 2008) and kidneys (Takako et al., 2012). Depending on their antioxidant capacity, green tea polyphenols can also improve deficits in spatial cognitive ability caused by cerebral hypoperfusion (Yan et al., 2010). In the present study, we applied hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to spinal cord neurons to produce a model of oxidative damage, and explored the neuroprotective effects of different concentrations of a green tea polyphenol, a possible new treatment for the functional recovery and regeneration of neurons after spinal cord injury.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

A green tea polyphenol (C17H19N3O, 281.36) was purchased from Purifa Biotechnology Co. (Chengdu, China). After the polyphenol was dissolved in triple-distilled water, the stock solution was microfiltered to remove bacteria and then stored at −20°C.

Animals

Ten male and ten female Sprague-Dawley rats, provided by the Experimental Animal Center of Liaoning Medical University in China (license No. SCXK (Liao) 2003-0011), were mated. At 16 days of gestation (E16), pregnant rats were anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate to remove the gravid uterus. The embryos were isolated and stored in sterile Hanks solution. The experimental procedure had full ethical approval from the Animal Ethics Committee of Liaoning Medical University in China.

Primary culture of spinal cord neurons from rat embryos

Spinal cord tissue from E16 rat embryos was isolated under a light microscope (Zeser, Shanghai, China). After removing the nerve roots and backbone, the tissue samples were digested with trypsin. The reaction was terminated using culture medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and pipetted to make a cell suspension. After filtration and centrifugation, the cells were cultured in α-minimal essential medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma). Penicillin (100 U/mL) and streptomycin (100 mg/mL) were added to the medium, and the cells were incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 7 days. The cells were then fixed with paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes and placed in 0.3% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes. After two washes with PBS, the cells were mixed with 3% H2O2 for 30 minutes and placed in blocking buffer for 20 minutes. The cells were then incubated with a mouse anti-rat neuron-specific enolase antibody (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C, followed by goat anti-mouse IgG (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 2 hours and then a streptavidin-biotin complex for 30 minutes. Tissue binding of the antibodies was visualized using a diaminobenzidine kit (Wuhan Boster, Wuhan, Hubei Province, China) for 30 minutes and stained with hematoxylin for 30 seconds. Cells were dehydrated through an ethanol series (80%, 90%, 95% and 100%; 4 minutes each), placed in xylene I and xylene II for 10 minutes each, and mounted with glycerin for observation under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Green fluorescence could be seen in the cytoplasm of cells positive for neuron-specific enolase.

Cell viability assay

Cells were inoculated into 96-well cell culture plates and incubated for 7 days. H2O2 was added to the medium at concentrations of 50, 100, 200, 500 and 1,000 μmol/L (six wells per concentration), and a blank control was also set. After 72 hours, the cells were digested with trypsin and made into a suspension at a density of 1 × 106 cells per mL. The cell suspension was mixed with 0.4% trypan blue solution in a 9:1 ratio and the cell viability was determined by the number of unstained (viable) cells counted within 3 minutes.

Grouping and polyphenol treatment

Cells in the normal control group were cultured for 7 days without further intervention. In the oxidative damage control group, cells were treated with 100 μmol/L H2O2 for 3 days. Cells in the green tea polyphenol groups were exposed to 100 μmol/L H2O2 for 3 days and then treated with different concentrations (50–200 μg/mL) of green tea polyphenol for 24 hours.

Determination of superoxide dismutase activity and malondialdehyde content

After treatment with green tea polyphenol for 24 hours, cells were collected and rinsed three times with PBS. The cells were then lysed and centrifuged, and 100 μL of supernatant was kept. Superoxide dismutase activity was determined using xanthine oxidase and malondialdehyde content was measured using thiobarbituric acid, both from kits (Jiancheng, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Real time-PCR detection of apoptosis-related gene expression

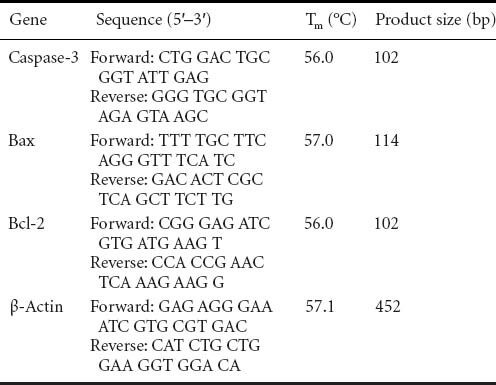

Following green tea polyphenol treatment for 24 hours, the total mRNA was extracted from the cell suspension, using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The expression of Bcl-2, Bax, caspase-3 and β-actin genes was determined by real time-PCR using an RNA PCR Kit (AMV) Version 3.0 (Takara Biotechnology, Otsu, Japan). All primer sequences were designed and synthesized by Takara Biotechnology Company (Dalian, China). The primer sequences are as follows:

The reaction mixture was pre-degenerated at 94°C for 15 minutes and 95°C for 30 seconds, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds and 56°C (for caspase-3 and Bcl-2), 57°C (for Bax) or 57.1°C (for β-actin) for 30 seconds. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, photographed under UV light and analyzed using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Heraules, CA, USA). Quantity One was used to calculate the optical density of bands in the acquired images of the samples. The area of each band was defined manually, and the software calculated the average intensity of each row of pixels and the number of rows of pixels in the area, resulting in an intensity profile for each band. The signal intensity represented the amount of mRNA expression.

Western blot analysis

Following green tea polyphenol treatment for 24 hours, the cells were lysed immediately in Laemmli buffer for 5 minutes at 95°C. Equal amounts of proteins from each group were prepared using bicinchoninic acid and separated by SDS/PAGE. The proteins were transferred electrophoretically from the gels to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories) which were then incubated with anti-rat caspase-3, -Bcl-2 and -Bax antibodies (all at 1:500 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C, followed by goat anti-mouse antibody (1:500 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Immunoreactive proteins were revealed using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL, USA). Expression of β-actin (mouse anti-β-actin, 1:500 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as the internal control. The autoradiograms were imaged on an Alpha Innotech Photodocumentation System (Alpha Innotech, Hayward, CA, USA) and the relative absorbance of the bands, representing amount of protein expression, was analyzed using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SD of separate experiments (n ≥ 3) and analyzed using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). One way analysis of variance and least significant difference test were used to compare groups, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Identification of spinal cord neurons

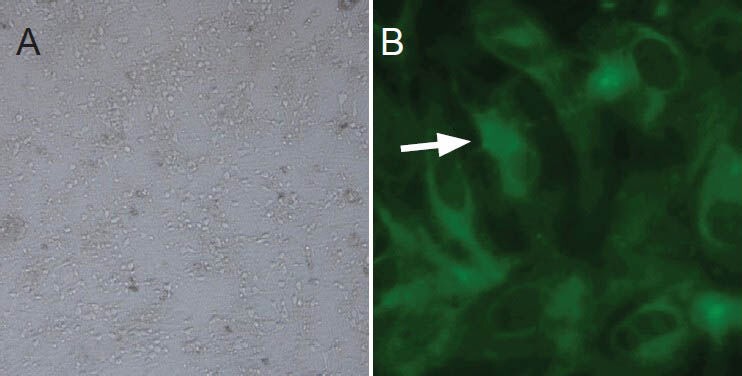

The cytoplasmic protein neuron-specific enolase is located in the cell bodies, axons and dendrites of neurons. Its expression correlates with cell differentiation and viability during the different stages of neuronal development and maturation. We counted the percentage of cells expressing neuron-specific enolase in 10 randomly chosen fields of view under a light microscope (Figure 1). The percentage of positive cells was 94.3%.

Figure 1.

Primary culture and identification of embryonic rat spinal nerve cells.

(A) Light microscopy (× 100) of primary spinal cord neurons, showing adherent and healthy neurons; some of the neurons showed small bumps. (B) Fluorescence microscopy (× 400) of spinal cord neurons identified using neuron-specific enolase, which fluoresced green (arrow) in the cytoplasm.

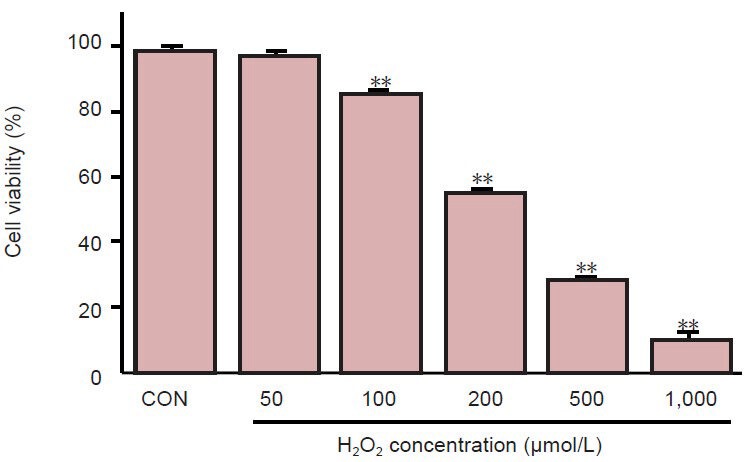

H2O2 reduced cell viability

Incubation of neurons with different concentrations of H2O2 for 72 hours caused a dose-dependent reduction in cell viability (Figure 2). High cellular activity was maintained with 100 μmol/L H2O2. At 100 μmol/L, a degree of cell damage was induced but high cellular activity remained; the cell survival rate of approximately 90% met the requirements for subsequent tests.

Figure 2.

Effect of hydrogen perioxide (H2O2) on the viability of primary spinal cord neurons from rat embryos.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, vs. CON group (one-way analysis of variance and least significant difference test). CON: Normal control group.

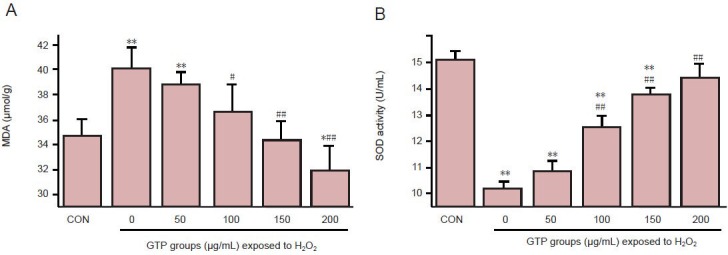

Malondialdehyde content and superoxide dismutase activity after treatment with green tea polyphenol

Malondialdehyde level in H2O2-treated spinal cord neurons was higher than that in normal control cells (P < 0.05) and treatment with green tea polyphenol produced a dose-dependent decrease in malondialdehyde level in H2O2-injured spinal cord neurons (Figure 3A). The activity of superoxide dismutase was significantly lower after oxidative damage than in normal control cells (P < 0.01). A dose-dependent increase in superoxide dismutase activity was observed with green tea polyphenol treatment in H2O2-exposed cells; after 200 μg/mL green tea polyphenol, superoxide dismutase activity was not significantly different from that in normal control cells (P > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effect of 24 hour treatment with green tea polyphenols (GTP) on malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity in spinal cord neurons under oxidative stress.

(A) A dose-dependent reduction in MDA level was seen with increasing concentrations of GTP, in particular 200 μg/mL, at which the MDA level was significantly lower than that in normal control cells. (B) SOD activity in H2O2-damaged cells was dose-dependently increased by GTP, in particular 200 μg/mL, at which SOD activity was not significantly different from that in the CON group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. CON group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, vs. 0 μg/mL GTP group (one-way analysis of variance and least significant difference test). CON: Normal control cells; H2O2: hydrogen perioxide.

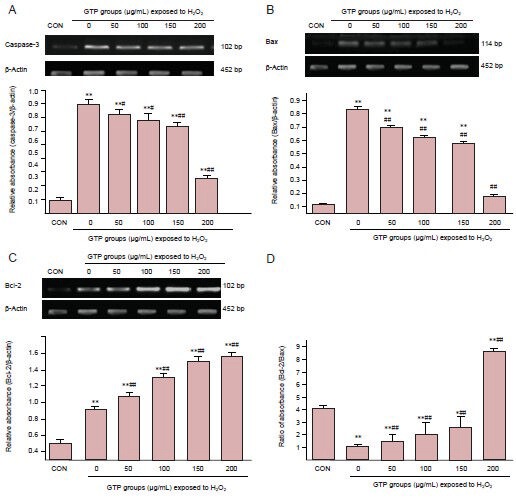

Apoptosis-related gene expression after treatment with green tea polyphenol

Caspase-3 and Bax mRNA expression was significantly greater after oxidative damage than in normal control cells, but this effect was reduced with increasing concentrations of green tea polyphenol (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01), in particular at the 200 μg/mL concentration (P < 0.01; Figure 4). Correspondingly, Bcl-2 mRNA expression and Bcl-2/Bax ratio increased significantly with increasing concentrations of green tea polyphenol (P < 0.01; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Expression of the apoptosis-related genes caspase-3 (A), Bax (B) and Bcl-2 (C), and the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax (D), in spinal cord neurons under H2O2-induced oxidative stress, after treatment with 0–200 μg/mL green tea polyphenol (GTP) for 24 hours (Real-time PCR).

Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, vs. CON group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, vs. 0 μg/mL GTP group (one-way analysis of variance and least significant difference test). CON: Normal control; H2O2: hydrogen perioxide.

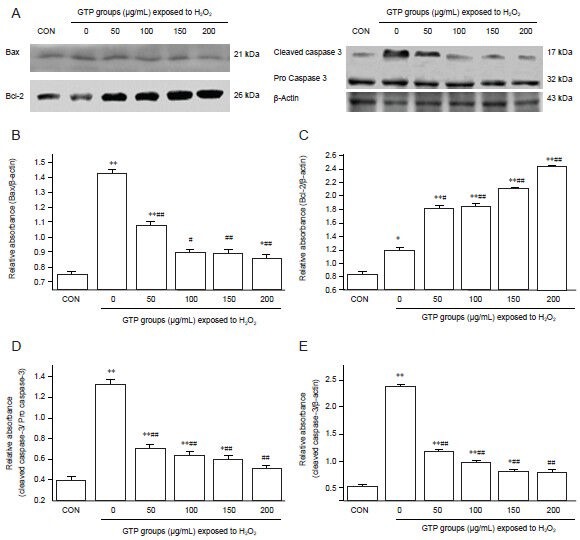

Apoptosis-related protein expression after treatment with green tea polyphenol

Western blot assay showed that protein expression of activated caspase-3 and Bax, and the ratio of activated caspase-3/caspase-3 precursor protein, in H2O2-exposed cells were markedly reduced by green tea polyphenol (P < 0.01), and Bcl-2 protein expression increased with increasing concentrations of green tea polyphenol (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Western blot assay (A) and quantification (B–E) of the expression of apoptosis-related proteins Bax (B), Bcl-2 (C) and caspase-3 (D, E) in spinal cord neurons under oxidative stress, after treatment with green tea polyphenol (GTP; 0–200 μg/mL) for 24 hours.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3, one-way analysis of variance and least significant difference test). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, vs. CON group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, vs. 0 μg/mL GTP group. CON: Normal control; H2O2: hydrogen perioxide.

Discussion

Oxidative stress is an important factor in secondary injury after damage to the spinal cord (Liu et al., 1998); as such, it is a key target in the treatment of spinal cord injury. Reactive oxygen species, including the superoxide anion, hydroxyl free radicals and hydrogen peroxide, are the components that induce oxidative stress damage (Taoka et al., 1995; Liu et al., 2004). Accumulation of oxidation products can cause a series of harmful effects such as lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, and DNA damage. The lipid peroxidation produced by oxidative stress damages the structure and function of cell and organelle lipid bilayers, and eventually leads to an increase in malondialdehyde (Seligman et al., 1997; Liu et al., 2004). Protein oxidation and DNA damage can also be harmful in a variety of ways. The extent of oxidative stress can be determined by peroxide indicators, such as active oxygen, H2O2 and malondialdehyde, and antioxidant indicators including superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase (Grabitz et al., 1990). Intracellular superoxide dismutase and malondialdehyde content can reflect the level of oxidative stress and metabolism in cells.

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is a specific procedure of cell death, controlled genetically and stimulated by physiological or pathological signaling. Many studies have confirmed the close relationship between oxidative stress and apoptosis (Gorman et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 2008; Tabas et al., 2011; Gogna et al., 2012). Apoptosis is a critical process in the maintenance of homeostasis in the body; however, in excess, it may cause tissue damage and lead to dysfunction. The process of apoptosis is regulated by promoting and inhibiting factors. The Bcl-2 and caspase families play a key role among these factors. The Bcl-2 gene is one of the most extensive apoptosis suppressor genes. Bax is one of the members of the Bcl-2 family, and has the opposite role to Bcl-2. The combined function of Bcl-2 and Bax determines the degree of apoptosis that occurs. The monomer Bax contributes towards apoptosis in two ways, by inhibiting the antiapoptotic effect of Bcl-2, and by forming excessive Bax homologous dimers that can induce apoptosis. If Bcl-2 is expressed excessively, however, Bcl-2 homologous dimers form and inhibit the process of apoptosis (Klemm et al., 2008). Pro-apoptotic factors in the caspase family include caspases 3, 6 and 7; of these, caspase-3 is the most important factor in mediating the process of apoptosis (Watanabe et al., 2004; Wajant et al., 2002). Bcl-2 can prevent apoptosis by suppressing the activation of caspase-3; but once caspase-3 is activated, the Bcl-2 protein is digested into shorter pieces by the caspase-3 enzyme, and its function changes to activation rather than inhibition of apoptosis (Fu et al., 2002). This shows that the Bcl-2 and caspase families interact closely in the regulation of apoptosis.

In the present study, we found that after oxidative damage, the intracellular malondialdehyde level in the injured spinal cord neurons was higher than that in normal cells. Green tea polyphenol caused a significant, concentration-dependent decrease in malondialdehyde content. After oxidative stress, the intracellular level of superoxide dismutase was significantly decreased; this effect was reversed with increasing concentrations of green tea polyphenol. Under oxidative stress, the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax was also significantly lower than in control cells, but this ratio increased significantly after treatment with green tea polyphenol. The present results reveal that after oxidative damage, the intracellular peroxidation index increased significantly in spinal cord neurons, while the antioxidant index showed the opposite trend. Pro-apoptotic gene expression increased significantly and anti-apoptotic gene expression decreased. Our results demonstrate that green tea polyphenols play a protective role in spinal cord neurons under oxidative stress, which can alleviate oxidation damage to the spinal cord neurons and inhibit cell apoptosis. These findings provide a new theoretical basis for reducing oxidative damage to the spinal cord neurons after spinal cord injury. In vivo experiments are needed to determine the protective effects of green tea polyphenols on spinal cord neurons after injury, and to identify further mechanisms and anti-oxidative stress pathways.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Song CM from the First Affiliated Hospital of Liaoning Medical University, China, for technical support.

Footnotes

Funding: This project was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81171799, and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, No. 2013T60948.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Copyedited by Slone-Murphy J, Wang J, Wang L, Li CH, Song LP, Zhao M

References

- 1.Azbill RD, Mu X, Bruce-Keller AJ, Mattson MP, Springer JE. Impaired mitochondrial function, oxidative stress and altered antioxidant enzyme activities following traumatic spinal cord injury. Brain Res. 1997;765:283–290. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beattie MS. Inflammation and apoptosis: linked therapeutic targets in spinal cord injury. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:580–583. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabrera C, Artacho R, Giménez R. Beneficial effects of green tea-a review. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006;25:79–99. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2006.10719518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campuzano O, Castillo-Ruiz MD, Acarin L, Gonzalez B, Castellano B. Decreased myeloperoxidase expressing cells in the aged rat brain after excitotoxic damage. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46:723–730. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrico KM, Vaishnav R, Hall ED. Temporal and spatial dynamics of peroxynitrite-induced oxidative damage after spinal cord contusion injury. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1369–1378. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008-0870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catala A. Lipid peroxidation of membrane phospholipids in the vertebrate retina Front. Biosci (Schol Ed) 2011;3:52–60. doi: 10.2741/s131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catala A. Lipid peroxidation modifies the picture of membranes from the “Fluid Mosaic Model” to the “Lipid Whisker Model”. Biochimie. 2012;94:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu YF, Fan TJ. Bcl-2 family proteins and apoptosis. Sheng Wu Hua Xue Yu Sheng Wu Wu Li Xue Bao. 2002;34:389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gogna R, Madan E, Kuppusamy P, Pati U. ROS-mediated p53 core-domain modifications determine apoptotic or necrotic death in cancer cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16:400–412. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorman AM, McGowan A, O’Neill C, Cotter T. Oxidative stress and apoptosis in neurodegeneration. J Neurol Sci. 1996;139(Suppl):45–52. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(96)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grabitz K, Freye E, Prior R, Kolvenbach R, Sandmann W. The role of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in preventing postischemic spinal cord injury. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1990;264:13–16. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5730-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jia Z, Zhu H, Li J, Wang X, Misra H, Li Y. Oxidative stress in spinal cord injury and antioxidant-based intervention. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:264–274. doi: 10.1038/sc.2011.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klemm K, Eipel C, Cantré D. Multiple doses of erythropoietin impair liver regeneration by increasing TNF-alpha, the Bax to Bcl-xL ratio and apoptotic cell death. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu D, Liu J, Sun D, Wen J. The time course of hydroxyl radical formation following spinal cord injury: the possible role of the iron-catalyzed Haber-Weiss reaction. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:805–816. doi: 10.1089/0897715041269650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu D, Sybert TE, Qian H, Liu J. Superoxide production after spinal injury detected by microperfusion of cytochrome c. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;25:298–304. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu J, Tang T, Yang H. Protective effect of deferoxamine on experimental spinal cord injury in rat. Injury. 2011;42:742–745. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu JB, Tang TS, Xiao DS. Changes of free iron contents and its correlation with lipid peroxidation after experimental spinal cord injury. Chin J Traumatol. 2004;7:229–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahin Kavakli H, Koca C, Alici O. Antioxidant effects of curcumin in spinal cord injury in rats. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2011;17:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seligman ML, Flamm ES, Goldstein BD, Poser RG, Demopoulos HB, Ransohoff J. Spectrofluorescent detection of malonaldehyde as a measure of lipid free radical damage in response to ethanol potentiation of spinal cord trauma. Lipids. 1997;12:945–950. doi: 10.1007/BF02533316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaafi S, Afrooz MR, Hajipour B, Dadadshi A, Hosseinian MM, Khodadadi A. Antioxidative effect of lipoic acid in spinal cord ischemia/reperfusion. Med Princ Pract. 2011;20:19–22. doi: 10.1159/000319772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen CL, Wang P, Guerrieri J, Yeh JK, Wang JS. Protective effect of green tea polyphenols on bone loss in middle-aged female rats. Osteoporosis Int. 2008;19:979–990. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0527-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabas I, Ron D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:184–190. doi: 10.1038/ncb0311-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takako Yokozawa, Jeong Sook Noh, Chan Hum Park. Green tea polyphenols for the protection against renal damage caused by oxidative stress. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012. 2012:845917. doi: 10.1155/2012/845917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taoka Y, Naruo M, Koyanagi E, Urakado M, Inoue M. Superoxide radicals play important roles in the pathogenesis of spinal cord injury. Paraplegia. 1995;33:450–453. doi: 10.1038/sc.1995.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thielecke F, Boschmann M. The potential role of green tea catechins in the prevention of the metabolic syndrome-a review. Phytochemistry. 2009;70:11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaishnav RA, Singh IN, Miller DM, Hall ED. Lipid peroxidation-derived reactive aldehydes directly and differentially impair spinal cord and brain mitochondrial function. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1311–1320. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wajant H. The Fas signaling pathway: more than a paradigm. Science. 2002;296:1635–1636. doi: 10.1126/science.1071553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watanabe M, Kitano T, Kondo T. Increase of nuclear ceramide through caspase-3-dependent regulation of the “sphingomyelin cycle” in Fas-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1000. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wyndaele M, Wyndaele JJ. Incidence, prevalence and epidemiology of spinal cord injury: what learns a worldwide literature survey? Spinal Cord. 2006;44:523–529. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu Y, Zhang JJ, Xiong L, Zhang L, Sun D, Liu H. Green tea polyphenols inhibit cognitive impairment induced by chronic cerebral hypoperfusion via modulating oxidative stress. J Nutr Biochem. 2010;21:741–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yune TY, Lee JY, Jiang MH, Kim DW, Choi SY, Oh TH. Systemic administration of PEP-1-SOD1 fusion protein improves functional recovery by inhibition of neuronal cell death after spinal cord injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:1190–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yune TY, Lee JY, Jung GY, Kim SJ, Jiang MH, Kim YC, Oh YJ, Markelonis GJ, Oh TH. Minocycline alleviates death of oligodendrocytes by inhibiting pro-nerve growth factor production in microglia after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7751–7761. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1661-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. From endoplasmic-reticulum stress to the inflammatory response. Nature. 2008;454:455–462. doi: 10.1038/nature07203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]