Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Injection of water into the pharynx induces contraction of the upper esophageal sphincter (UES), triggers the pharyngo-UES contractile reflex (PUCR), and at a higher volume, triggers an irrepressible swallow, the reflexive pharyngeal swallow (RPS). These aerodigestive reflexes have been proposed to reduce the risks of aspiration. Alcohol ingestion can predispose to aspiration and previous studies have shown that cigarette smoking can adversely affect these reflexes. It is not known whether this is a local effect of smoking on the pharynx or a systemic effect of nicotine. The aim of this study was to elucidate the effect of systemic alcohol and nicotine on PUCR and RPS.

METHODS

Ten healthy non-smoking subjects (8 men, 2 women; mean age: 32±3 s.d. years) and 10 healthy chronic smokers (7 men, 3 women; 34±8 years) with no history of alcohol abuse were studied. Using previously described techniques, the above reflexes were elicited by rapid and slow water injections into the pharynx, before and after an intravenous injection of 5% alcohol (breath alcohol level of 0.1%), before and after smoking, and before and after a nicotine patch was applied. Blood nicotine levels were measured.

RESULTS

During rapid and slow water injections, alcohol significantly increased the threshold volume (ml) to trigger PUCR and RPS (rapid: PUCR: baseline 0.2±0.05, alcohol 0.4±0.09; P=0.022; RPS: baseline 0.5±0.17, alcohol 0.8±0.19; P=0.01, slow: PUCR: baseline 0.2±0.03, alcohol 0.4±0.08; P=0.012; RPS: baseline 3.0±0.3, alcohol 4.6±0.5; P=0.028). During rapid water injections, acute smoking increased the threshold volume to trigger PUCR and RPS (PUCR: baseline 0.4±0.06, smoking 0.67±0.09; P=0.03; RPS: baseline 0.7±0.03, smoking 1.1±0.1; P=0.001). No similar increases were noted after a nicotine patch was applied.

CONCLUSIONS

Acute systemic alcohol exposure inhibits the elicitation PUCR and RPS. Unlike cigarette smoking, systemic nicotine does not alter the elicitation of these reflexes.

INTRODUCTION

Recently, several aerodigestive reflexes have been described, which have been proposed to protect the airways against aspiration during the retrograde transit of gastric contents (1–13). Distension of the esophagus can trigger the esophago-upper esophageal sphincter (UES) contractile reflex (1–4), and the resulting enhanced UES pressure may prevent entry of esophageal contents into the pharynx. If fluid does enter the pharynx, pharyngeal stimulation by the fluid can also enhance UES pressure by triggering the pharyngo-UES contractile reflex (PUCR) (5–8) and this in turn may protect against further esophagopharyngeal reflux. Fluid in the pharynx can also trigger closure of the tracheal intriotus by eliciting the PGCR (pharyngo-glottal closure reflex) (9–11) and the reflexive pharyngeal swallow (RPS) (8,12), which will not only close the tracheal intriotus but will also clear the pharynx of any residual fluid (8,12,13). Adduction of the vocal cords can also be induced by distension of the esophagus through the esophagoglottal closure reflex (1,2).

Integrity of the aerodigestive reflexes may be important in protecting the airways against aspiration injury. Alcoholics are at risk of developing aspiration pneumonia during an episode of severe alcohol intoxication. It is plausible that the depressant effect of alcohol on the central nervous system blunts the airway protective reflexes that may then predispose those with alcohol intoxication to aspiration of gastric contents. It is also not uncommon for cigarette smokers to have recurrent laryngeal and pulmonary disorders. In previous studies, we have shown that acute and chronic cigarette smoking can adversely affect the elicitation of PGCR, PUCR, and RPS (8,10), thereby predisposing cigarette smokers to risks of aspiration. As smokers are given nicotine patches to help them quit smoking, it is important to know whether this adverse effect of smoking on the aerodigestive reflexes is secondary to the local effect of cigarette smoke on the pharynx or to the effect of systemic nicotine.

The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking adversely affected the elicitation of PUCR and RPS through a systemic effect of alcohol and nicotine, respectively. This study was designed to elucidate the effect of acute intravenous (IV) administration of alcohol and systemic administration of nicotine through a nicotine patch on PUCR and RPS.

METHODS

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical College of Wisconsin and all subjects gave informed written consent before the study. Healthy volunteers were recruited for the study. Unsedated transnasal endosopy was performed in all subjects to rule out any associated silent upper gastrointestinal disorders. On the day of the study, all subjects underwent a brief history and physical examination.

To determine the effect of systemic alcohol on PUCR, and RPS, we studied 10 healthy (8 men, 2 women; 32± 3 years) subjects without any history of alcohol abuse. None of the volunteers smoked cigarettes as our previous studies have shown that these reflexes are adversely affected by cigarette smoking. Each subject was studied before and during a sustained breath alcohol level of 0.1%. This level is within the legal driving limits of the state where the study was carried out and hence, at this level, we did not expect any major changes in the cognitive, motor, or sensory functions of the individual. An electrocardiogram was obtained and a peripheral IV line was placed. Before investigation, female subjects underwent a serum pregnancy test to rule out pregnancy.

After initial data recordings, a baseline breath alcohol level was obtained using a breathalyzer machine. After baseline recordings, blood pressure was measured every 15 min, and finger stick blood glucose was measured every half an hour. Heart rate and pulse oximetry were monitored continuously. Subsequently, IV 5% alcohol in normal saline was infused at a precalculated rate based on patient weight. The breath alcohol level was measured every 15 min. Once a level of 0.1% was reached, a blood sample was sent for confirmation. The rate of infusion was then cut in half to maintain the breath alcohol level at 0.1%, and repeat pharyngeal stimulations were performed. On completion of the pharyngeal stimulations, the IV infusion was stopped and the instruments removed. Patients were fed a meal and monitored by the General Clinical Research Center until the breath alcohol level returned to 0.0% as determined by the breathalyzer. Subjects were accompanied home by a friend.

To evaluate the effect of systemic nicotine on aerodigestive reflexes, we studied 10 healthy chronic smokers (mean age: 34 ± 8 s.d. years; 7 men) in the sitting upright position. Smokers were defined as those who smoked one or more packs of cigarettes per day for at least 2 years. None of the smokers studied were consuming alcohol. The smokers were instructed to abstain from smoking for 12 h before the study after which 5 ml of blood was collected to measure the serum nicotine level to ascertain compliance. They were then studied before and 10 min after smoking two cigarettes (Marlboro, Philip Morris, Richmond, VA). The 10-min interval after smoking allowed for the pharyngeal temperature to return to baseline. Blood for serum nicotine level was also collected immediately after smoking. On a different day, smokers were again studied after they refrained from smoking for 12 h during which they applied a nicotine patch that delivered 21 mg of nicotine over 24h (Nicoderm CQ, SmithKline Beecham, Pittsburgh, PA). Serum nicotine concentrations were determined using a modification of the gas chromatography-mass spectrometry method described by Feyerabend and Russel (14). Nicotine was extracted from 1 ml of serum using Varian Inc. (Palo Alto, CA), Bond-Elut C18, solid-phase columns. It was quantified using a Hewlett Packard (Palo Alto, CA) 5890 gas chromatograph—5989 MS Engine mass spectrometer (Hewlett Packard). In our previous studies that compared smokers with non-smokers (8,10), for ethical reasons, non-smokers were not asked to smoke. In this study, we did not include non-smokers as our aim was to compare the effects of acute smoking vs. nicotine patch on the aerodigestive reflexes and hence, only smokers were enrolled.

To monitor the UES resting pressure and its response to pharyngeal water stimulation, we used a UES sleeve assembly (Dent-sleeve, Adelaide, Australia) that incorporated a sleeve device (6×0.5×0.3 cm) with side hole recording ports at its proximal and distal ends for manometric positioning (5–8,12). The sleeve assembly also had additional recording sites at 4.5, 7, and 14 cm distal and 3 cm proximal to the sleeve sensor. After the application of a non-anesthetic lubricant jelly (Surgilube, E. Fougera, Atlanta, Melville, NY) to the nasal cavity using a cotton-tipped applicator (to prevent the possibility of anesthetizing the pharynx, anesthetic jelly was not used) the manometric assembly was introduced through the nose and positioned such that the manometric port immediately proximal to the sleeve sensor was positioned 2 cm above the UES high pressure zone and directed posteriorly. After manometric positioning, this port was used for water injection and was not used for pressure recording.

The injection port, the esophageal ports, and the sleeve sensor were connected to pressure transducers in line with a minimally compliant pneumohydraulic pump (Arndorfer Medical Specialities, Greendale, WI). With this arrangement, the onset and offset of water injection and UES pressure were recorded using the MMS Motility System (Medical Measurement Systems, Enschede, The Netherlands).

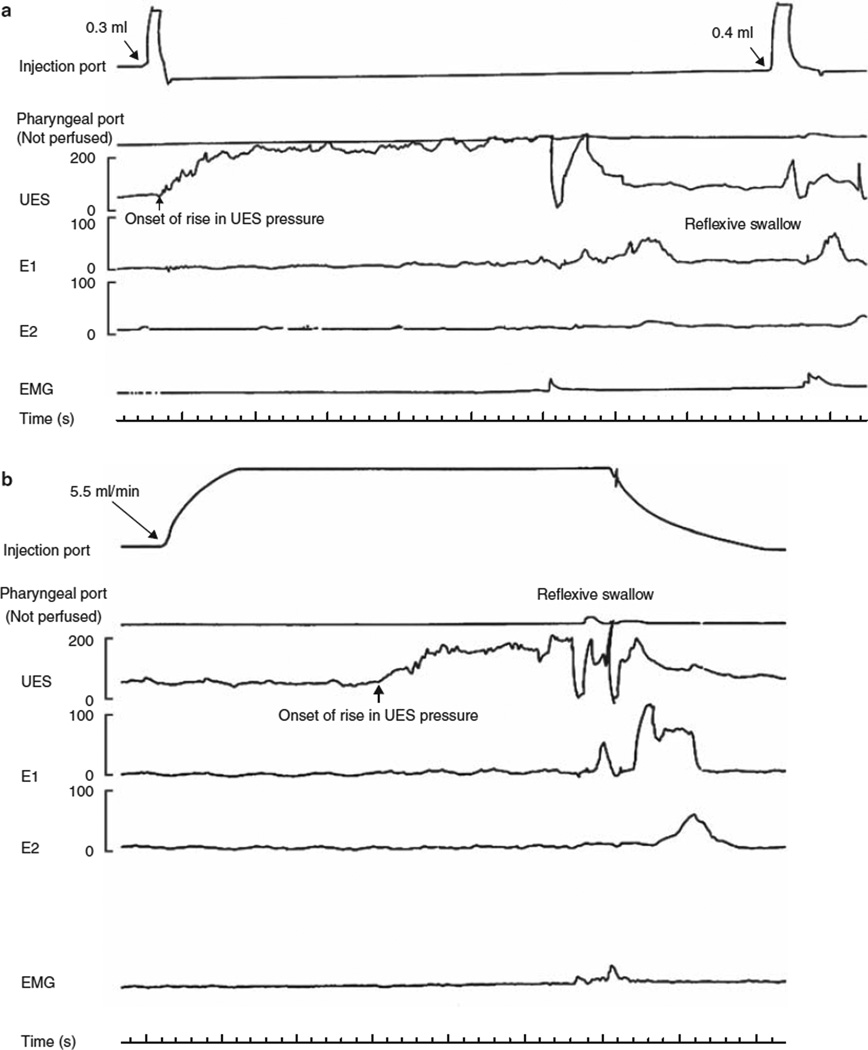

For pharyngeal water stimulation, we used previously described techniques (6–8,10). We tested two modes of fluid delivery into the pharynx, such as rapid pulse injection and slow continuous infusion (Figure1a, b). For rapid pulse injection, water was injected rapidly using a hand-held syringe. We started with 0.1 ml of water and then increased the volume by 0.1-ml increments until an irrepressible swallow occurred (RPS). After each injection, the subject was asked to swallow so as to clear the pharynx of any residual water. Slow continuous infusion was performed at a rate of 5.5 ml/min using a Harvard infusion pump (Model N0975; Harvard Apparatus, Dover, MA) until an irrepressible swallow occurred. Each injection was started 5–10 s after the UES pressure returned to baseline after a command swallow (to clear the pharynx), and subjects then withheld swallowing as long as they could. For both rapid and slow injections, water was maintained at room temperature.

Figure 1.

Pharyngo-UES contractile reflex and reflexive pharyngeal swallow during rapid and slow pharyngeal water injection. Upper esophageal sphincter (UES) pressure after (a) rapid and (b) slow injections of water into the pharynx. Rapid injection of 0.3 ml of water into the pharynx resulted in an increase in UES pressure over the baseline (pharyngo-UES contractile reflex). This pressure increase was not associated with any electromyographic (EMG) activity of sub-mental muscles. Injection of 0.4ml of water into the pharynx resulted in a reflexive pharyngeal swallow (E1, E2, E3: proximal esophageal perfusion ports). Slow perfusion of water (5.5 ml/min) into the pharynx also resulted in an increase in UES pressure over the baseline. Similar to rapid water injection, this pressure increase was not associated with any EMG activity of the sub-mental muscles until a reflexive pharyngeal swallow was triggered 24s after the onset of pharyngeal water perfusion.

We then determined in each subject the change in UES pressure (three out of three injections) in response to various volumes of pharyngeal water injections (PUCR). For comparison of the UES pressure before and after the injection, we used the average end-expiratory pressure for a 10-s period before the injection as the baseline. We measured the maximum UES pressure after pharyngeal water injection, excluding the 3-s interval before deglutitive relaxation, if a swallow occurred. This was done to avoid counting in the commonly seen pressure increase that is registered by the sleeve immediately before its swallow-induced relaxation. We determined in each subject, for both rapid pulse and slow continuous injection, the smallest volume of water that in three out of three injections triggered the UES contractile reflex and pharyngeal swallow. These volumes were termed “the threshold volume,” the threshold volume required to elicit the reflex.

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way or two-way analysis of variance as appropriate. Students t-test was used for normally distributed data. Values in the text are presented as mean±s.d. unless stated otherwise.

RESULTS

All subjects completed the study and none of the volunteers experienced any adverse effects.

Effect of systemic alcohol on aerodigestive reflexes

PUCR

The threshold volume of water for triggering PUCR at a breath alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0% during rapid injection of water into the pharynx was 0.2 ±0.05 s.d. ml. After IV alcohol with a blood BAC of 0.1%, it took a significantly larger volume of water to elicit this reflex (0.4 ± 0.09; P = 0.022; Table 1). Similar to rapid water injections, the threshold volume required to trigger PUCR during slow water injection into the pharynx was significantly higher with a BAC of 0.1% compared with a BAC of 0% (Table 1, slow injection: before 0.2±0.03, after 0.4±0.08; P = 0.012).

Table 1.

Threshold volume (ml±s.d.) to elicit aerodigestive reflexes before and after IV alcohol

| BAC | PUCR rapid | PUCR slow | RPS rapid | RPS slow |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 0.2±0.05 | 0.2±0.03 | 0.5±0.17 | 3.0±0.3 |

| 0.1% | 0.4±0.09 | 0.4±0.08 | 0.8±0.19 | 4.6±0.5 |

| P value | 0.022 | 0.012 | <0.0001 | 0.028 |

BAC, breath alcohol concentration; IV, intravenous; PUCR, pharyngo-upper esophageal sphincter contractile reflex; RPS, reflexive pharyngeal swallow.

The basal (pre-alcohol) mean UES pressure was 66 ± 29 s.d. After IV alcohol, the mean UES pressure was 72 ± 23 which was not significantly different from the basal mean pressure (P = 0.7). The percentage increase in UES pressure over basal pressure after injection of water into the pharynx was 105±68% s.d. After IV alcohol, although the observed percentage increased in UES pressure was less pronounced (74±55%), this did not reach statistical significance.

RPS

When RPS was elicited by rapid water injections, the difference in threshold volume for eliciting this reflex at a BAC of 0.1% (0.8±0.19) was significantly higher compared with the volume at a BAC of 0.0% (0.5 ±0.17; P<0.01). During slow infusion of water into the pharynx, the threshold volume of water required to trigger RPS was 3.0 ±0.3 ml with a BAC of 0%. A larger volume was required to elicit this reflex with a BAC of 0.1%(3.6±0.5; P = 0.028).

Effect of systemic nicotine on aerodigestive reflexes

Serum nicotinelevels

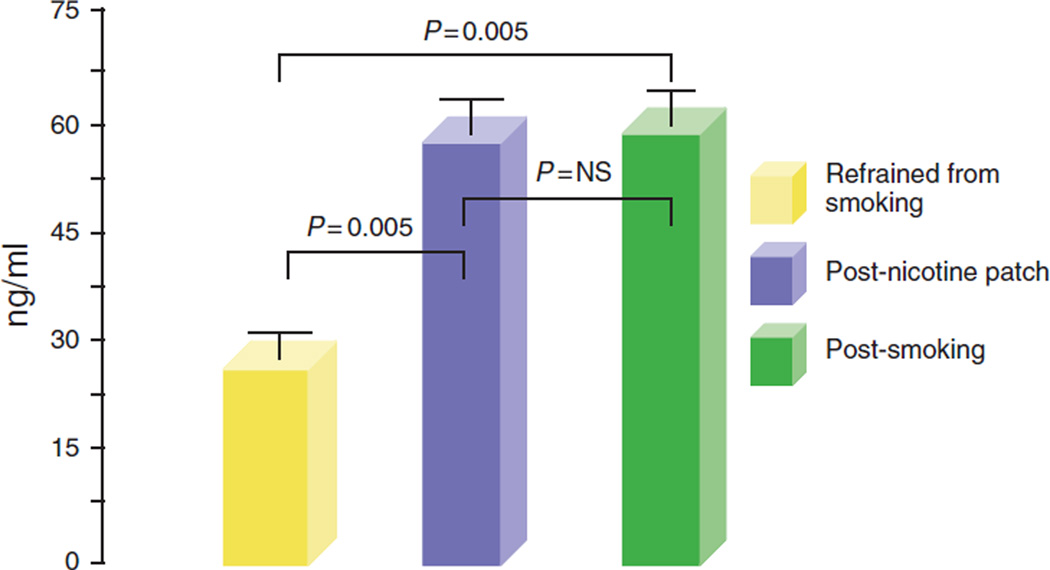

Compared with baseline( 12 habstinence from smoking), serum nicotine levels were significantly higher immediately after smoking two cigarettes (baseline 24.5 ± 6 s.e. ng/ml; after smoking 54.4±7ng/ml; P = 0.005). Similarly, a 12-h application of a nicotine patch (subject refrained from smoking during this period) resulted in a significantly higher serum nicotine level as compared with baseline (after nicotine patch 54.2±7ng/ml;P = 0.006). There was no significant difference in the peak serum nicotine levels attained after smoking and after the application of a nicotine patch (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Serum nicotine levels. Compared with baseline (12 h abstinence from smoking), serum nicotine levels were significantly higher immediately after smoking two cigarettes. Similarly, a 12-h application of a nicotine patch (subject refrained from smoking during this period) also resulted in a significantly higher serum nicotine level as compared with baseline. There was no significant difference in the peak serum nicotine levels attained after smoking and after a nicotine patch.

PUCR

Except for in two smokers, rapid or slow injection of water into the pharynx at a threshold volume resulted in an increase in UES pressure. Smoking of two cigarettes abolished the PUCR in three additional smokers (during slow pharyngeal injection).

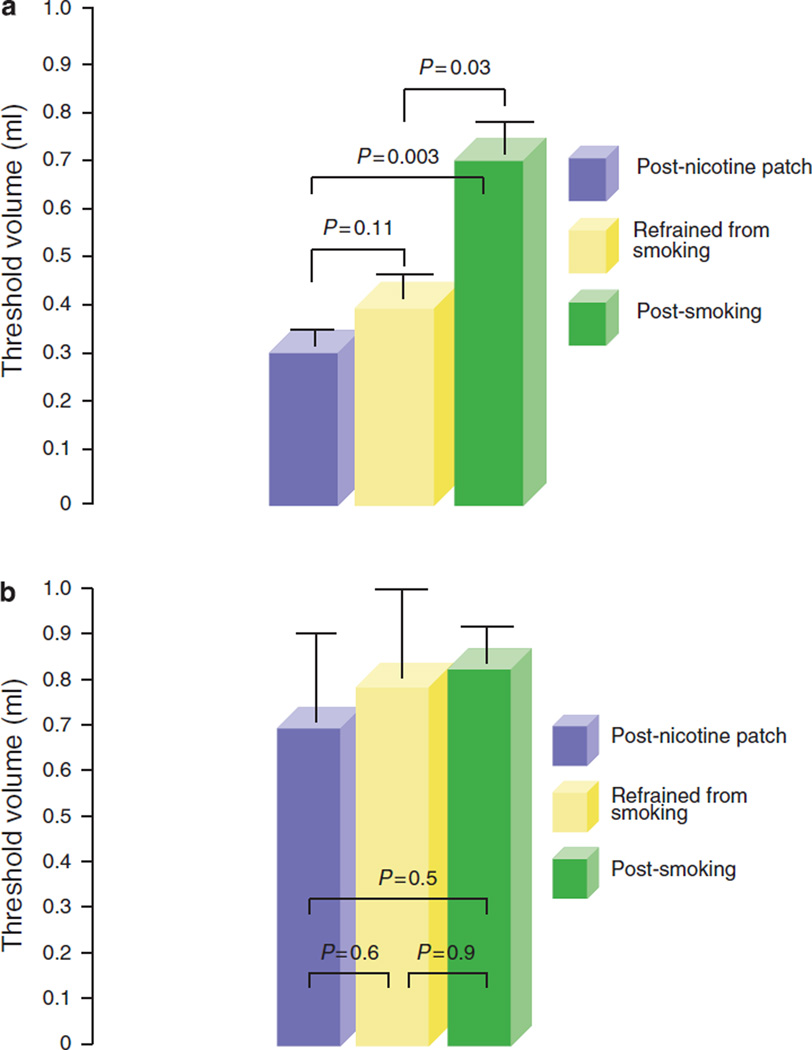

During rapid and slow water injections, the threshold volume required to trigger PUCR was 0.4 ± 0.06 s.d. ml and 0.8 ± 0.2 ml (P = 0.005), respectively. Acute smoking of two cigarettes further increased the threshold volume required to trigger the reflex on rapid water injection (before smoking 0.4 ±0.06 ml, after smoking 0.67 ±0.09 ml; P = 0.03). No such increase was noted after the application of a nicotine patch despite serum nicotine levels increasing to similar peak values after smoking and after nicotine patch (threshold volume: rapid injection: before nicotine patch 0.4 ±0.06 ml, after nicotine patch 0.3 ±0.04 ml, P = NS). During slow water injection, neither acute smoking of two cigarettes nor nicotine patch increased the threshold volume required to trigger PUCR (before smoking 0.8 ± 0.2 ml, after smoking 0.83±0.1 ml, after nicotine patch 0.7±0.2 ml, P = NS) (Figure 3a, b).

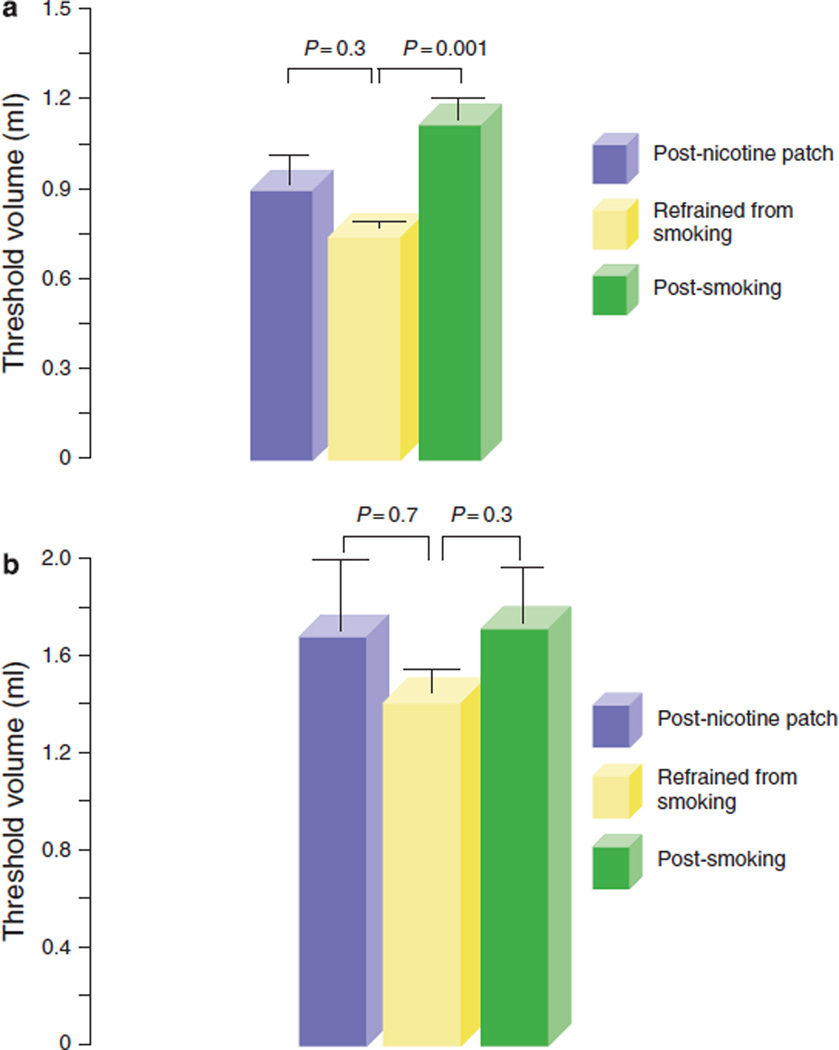

Figure 3.

Pharyngo-UES contractile reflex during rapid and slow pharyngeal water injections in smokers. Threshold volume required for triggering pharyngo- upper esophageal sphincter (UES) contractile reflex (PUCR) during (a) rapid and (b) slow pharyngeal water injections. Acute smoking of two cigarettes significantly increased the threshold volume required to trigger the PUCR on rapid water injection. No such increase was noted after an application of a nicotine patch despite serum nicotine levels ncreasing to similar peak values observed after smoking.

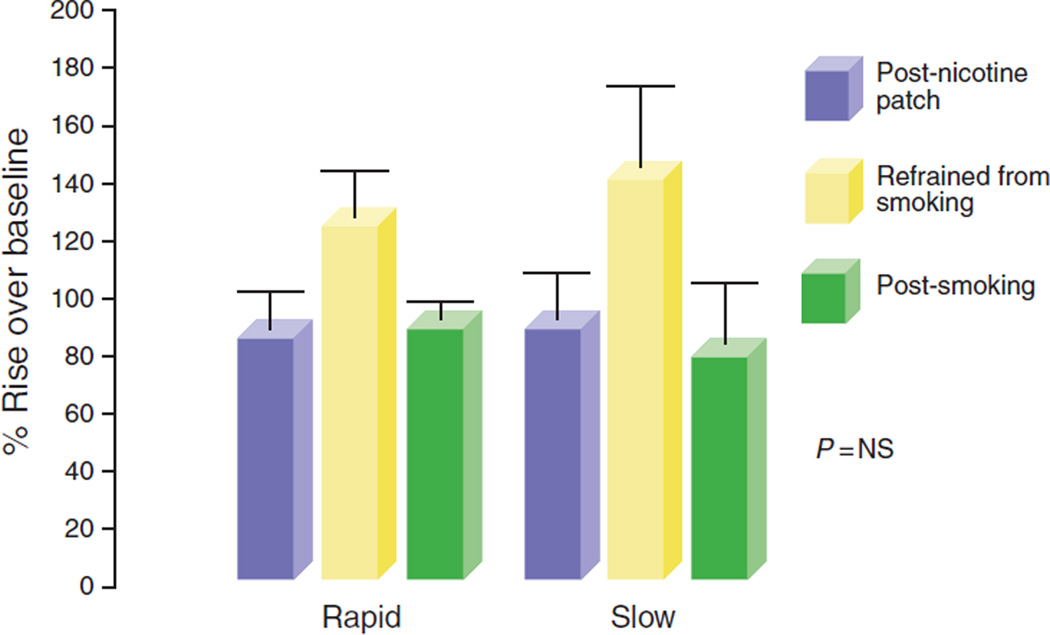

The percentage increase in UES pressure over basal values after pharyngeal stimulation by both rapid and slow water injections was similar after smoking and after nicotine patch (Figure 4, rapid: before smoking 83±16% s.e., after smoking 86±8%, after nicotine patch 126±17; slow: before smoking 91±19%, after smoking 78±27%, after nicotine patch 141±34%).

Figure 4.

Percentage rise if UES pressure is over baseline during rapid and slow pharyngeal water injections. The percentage increase in upper esophageal sphincter (UES) pressure over basal values after pharyngeal stimulation by both rapid and slow water injections after acute smoking or after an application of a nicotine patch was similar.

RPS

The threshold volume for triggering RPS during rapid water injection into the pharynx was 0.7 ± 0.03 ml and after acute smoking of two cigarettes, it further increased to l.l±0.1 ml (P= 0.001). No similar increase was noted after the nicotine patch was applied (post nicotine patch 0.9±0.2, P = NS). The threshold volume required to trigger RPS by slow pharyngeal water injection was 1.4±0.1 ml. However, no significant increase in the threshold volume was observed after smoking or after nicotine patch (Figure 5a, b).

Figure 5.

Reflexive pharyngeal swallow during rapid and slow pharyngeal water injections in smokers. Threshold volume required for triggering a reflexive pharyngeal swallow (RPS) during (a) rapid and (b) slow pharyngeal water injections. After acute smoking of two cigarettes, the threshold volume for triggering RPS increased significantly during rapid water injection. No similar increase was noted after an application of a nicotine patch or during slow water injections.

DISCUSSION

Anatomical proximity of the inlets of the respiratory and digestive tracts in the pharynx can predispose the airways to risks of aspiration when gastric refluxate reaches the pharynx. Several aerodigestive reflexes have been identified that have been proposed to help prevent the aspiration of gastric contents (1–13). Among these are the PUCR and RPS. These reflexes are triggered in response to the stimulation of the posterior pharynx by water. Entry of fluid into the pharynx during reflux events can reflexively enhance UES pressure (PUCR), thereby preventing further esophagopharyngeal reflux. At a larger volume, water in the pharynx triggers a reflexive swallow (RPS) that not only lifts the larynx and closes the laryngeal intriotus but also clears the pharynx of any residual fluid volume. Blunting of these protective reflexes may predispose the airway to aspiration. Direct evidence for this airway protective function of these reflexes was recently shown in cigarette smokers in whom these reflexes are defective and by blunting these reflexes by pharyngeal anesthesia in healthy subjects and perfusing water into the pharynx (15,16).

During an episode of severe alcohol intoxication, it is not uncommon for alcoholics to develop aspiration pneumonia especially during spells of vomiting or regurgitation. Studies have also shown that alcohol intake can predispose to gastroesophageal reflux by delaying gastric emptying, stimulating gastrin and acid secretion, decreasing lower esophageal sphincter pressure, inducing abnormal secondary peristalsis, and decreasing esophageal motility (17–19). Similarly, cigarette smoking/nicotine can also predispose to gastroesophageal reflux by delaying gastric emptying, decreasing lower esophageal sphincter pressure, and impairing esophageal acid clearance (20–28). Gastroesophageal reflux in turn can predispose to microaspiration (29–31). Although simultaneously monitoring esophageal and tracheal pH, Jack et al. (29) showed that of the 37 episodes of esophageal reflux, each lasting longer than 5 min, 5 were associated with a decrease in tracheal pH. Peak expiratory flow rates decreased over ten times more when both esophageal acid and tracheal acid were present compared with when only esophageal acid was present. Hence, besides the risks of overt aspiration pneumonia with acute alcohol intoxication, chronic alcohol intake can predispose one to risks of microaspiration. Integrity of the aerodigestive reflexes that potentially protect against aspiration may be important in alcohol consumption and in cigarette smoking. In previous studies, we did show that chronic and acute cigarette smoking can adversely affect the triggering of PGCR, PUCR, and RPS (8,10). However, we do not know whether this effect is secondary to systemic nicotine or due to the local effect of cigarette smoking on the pharynx. It is important to know this as preparations that deliver systemic nicotine-like nicotine patches or gums are used to help quit smoking. There are no previous studies investigating the effect of systemic alcohol or systemic nicotine on the aerodigestive reflexes.

In this study, we have shown that systemic alcohol exposure to a BAC of 0.1% has an adverse effect on the elicitation of PGCR, PUCR, and RPS. This level is within the legal driving limits of the state where the study was carried out and hence, at this level, we did not expect any major changes in the cognitive, motor, or sensory functions in the individual. Subjects were closely monitored during the study. Although we did not study the aerodigestive reflexes at multiple alcohol levels, it is intuitive that higher alcohol levels will induce more alterations in the reflex thresholds. This assumption is based on the clinical observation that cognitive impairment is directly related to an increase in alcohol level. However, determining the actual dose response will be of clinical importance. In this study, we did not evaluate the influence of alcohol on the aerodigestive reflexes in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia. One can speculate that suppression of the residual-preserved reflexes by alcohol in patients with baseline-compromised aerodigestive reflexes can potentially further contribute to the risks of aspiration. This assumption is supported by some recent data from our laboratory showing that values as small as 0.6 ml can be aspirated if RPS is not triggered (15,16).

The exact mechanism(s) by which alcohol adversely affects the elicitation of the above reflexes is not known. However, as none of the volunteers were chronic alcoholics and all were given IV alcohol, the adverse effect of alcohol on these reflexes seems to be systemic in nature rather than its local action on pharyngeal receptors. Studies (32,33) have shown that in both humans and in cats, acute alcohol decreases contractibility of both the lower esophageal sphincter and the smooth muscles of the lower esophagus. In cats, this inhibitory effect was not abolished by cervical vagotomy or IV tetrodotoxin, thereby suggesting a direct effect of alcohol on these muscles. They also showed that the inhibitory effect occurred at pharmacological concentrations of alcohol and was not simply caused by cytotoxicity. However, contrary to its effect on the smooth muscles of the esophagus, Keshavarzian et al. (34) showed that alcohol does not inhibit calcium influxes into the striated muscles of the esophagus. Hence, it is unlikely that the mechanism of the deleterious effect of alcohol on the studied aerodigestive reflexes could be secondary to the direct effect of alcohol on the striated muscles of the larynx, pharynx, and the UES. It is likely that these deleterious effects could be secondary to the known inhibitory effect of alcohol on the central nervous system. Studies have shown a reduction in the cerebral blood flow in subjects with chronic alcoholism (35,36). However, as none of the volunteers studied were chronic alcoholics and had normal responses to pharyngeal water injections before IV alcohol, it is likely that the acute depressant effect of a BAC of 0.1% could have altered the response to pharyngeal water injections. On the basis of this preliminary study, further studies using functional brain imaging, evoked potentials, or afferent nerve activity will be required to determine the mechanism of alcohol-induced alterations in aerodigestive reflexes.

In a previous study, we found that a significantly higher volume of water was required in chronic smokers to trigger PUCR and RPS compared with non-smokers, and acute smoking of two cigarettes by smokers further significantly increased the threshold volume required to trigger these reflexes (8). Secondary to ethical concerns, in these previous studies, non-smokers were not asked to smoke cigarettes. In this study, we did not enroll non-smokers as our aim was to compare the influence of acute smoking (in smokers) with that of a nicotine patch on the aerodigestive reflexes. Similar to our previous studies, in this study, we found that cigarette smoking adversely affects the elicitation of these reflexes. However, no such adverse effect was noted after the application of a nicotine patch despite peak serum nicotine levels increasing to similar values after smoking two cigarettes and after nicotine patch application. These findings suggest that the negative effect of smoking on these reflexes may be a peripheral local effect of smoking on the sensory afferent branches of these reflexes rather than a systemic effect of nicotine. However, a central effect cannot be completely ruled out as, during rapid water injection, the difference in the threshold volume for triggering RPS between post-nicotine patch and post-real smoking was not significant.

It is possible that chronic cigarette smoking may affect the pharyngeal mucosa and/or alter the concentration and function of the pharyngeal sensory nerve endings. It is still not clear whether the local effect could be due to nicotine or the effect of the contents of the cigarette smoke on the pharynx. Nicotine has been shown to adversely affect the esophageal mucosa by producing free radicals resulting in oxidative stress injury (37), and by inhibiting sodium transport (38). It is possible that cigarette smoking may have similar effects on the pharyngeal mucosa leading to an alteration in the function of the pharyngeal sensory nerve endings.

In summary, we state that acute alcohol exposure can adversely affect the triggering of PUCR and RPS. These effects of alcohol can weaken the airway protective mechanisms against aspiration and may have implications in the pathogenesis of pneumonia after acute alcohol intoxication. This deleterious effect of alcohol appears to be secondary to a systemic effect of alcohol rather than its local effect on the pharynx. Similarly, like previous studies (8,10), acute cigarette smoking further increased the threshold volume required to trigger these reflexes, whereas no such adverse effect was seen after a nicotine patch was applied. This finding suggests that the negative effect of smoking on these reflexes may be due to a local effect of smoking on the pharynx rather than a systemic action of nicotine. Hence, preparations that deliver systemic nicotine to help quit smoking like nicotine patches may be used without compromising the aerodigestive reflexes.

Although not the subject of this study, it is conceivable that concurrent use of tobacco and alcohol may have an additive deleterious effect on the aerodigestive reflexes. Given the fact that these substances are commonly used together, this potential effect may have clinical and health ramifications.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

-

✓

Aerodigestive reflexes protect the airways against aspiration.

-

✓

Cigarette smoking can adversely affect these reflexes.

-

✓

Alcohol ingestion can predispose to aspiration.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

-

✓

Acute systemic alcohol exposure inhibits the elicitation pharyngo-UES contractile reflex and reflexive pharyngeal swallow.

-

✓

Unlike cigarette smoking, systemic nicotine does not adversely affect the elicitation of these reflexes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Mechanisms of Upper Gut and Airway Interaction grant P01DK068051-01A1 and the Esophageal Motor Function in Health and Disease grant 5R01DK025731-28.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Reza Shaker, MD.

Specific author contributions: Study concept and design, performance of the procedures, analysis, statistics, majority of the writing, and review: Kulwinder Dua; study concept and design, majority of the writing, and review: Reza Shaker; data analysis: Sri Naveen Surapaneni; performance of the procedures, data collection, and statistics: Rajesh Santharam; performance of the procedures, data collection, and statistics: David Knuff; performance of the procedures: Candy Hofmann.

Potential competing interests: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaker R, Dodds WJ, Ren J, et al. Esophagoglottal closure reflex: a mechanism of airway protection. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:857–861. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90169-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaker R, Ren J, Medda B, et al. Identification and characterization of the esophagoglottal closure reflex in a feline model. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:G147–G153. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.266.1.G147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freiman JM, El-Sharkay TY, Diamant NE. Effect of bilateral vagosympathetic nerve blockade on response of the dog upper esophageal sphincter (UES) to intra esophageal distention and acid. Gastroenterology. 1981;812:78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enzman DR, Harell GS, Zboralske FF. Upper esophageal sphincter response to intraluminal distention in man. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:1292–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medda BK, Lang IM, Layman RD, et al. Characterization and quantification of a pharyngo-UES contractile reflex in the cat. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:G972–G983. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.267.6.G972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ren J, Shaker R, Lang I, et al. Effect of volume, temperature and anesthesia on the pharyngo-UES contractile reflex in humans. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:A677. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaker R, Ren J, Xie P, et al. Characterization of the pharyngo-UES contractile reflex in humans. Am J Physiol. 1997;36:G854–G858. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.4.G854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dua K, Ren J, Sui Z, et al. Effect of chronic and acute cigarette smoking on the pharyngo-upper oesophageal sphincter contractile reflex and reflexive pharyngeal swallow. Gut. 1998;43:537–541. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.4.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ren J, Shaker R, Dua K, et al. Glottal adduction response to pharyngeal water stimulation: evidence for a pharyngoglottal closure reflex. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:A558. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dua K, Bardan E, Ren J, et al. Effect of chronic and acute cigarette smoking on the pharyngo-glottal closure reflex. Gut. 2002;51:771–775. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaker R, Ren J, Bardan E, et al. Pharyngoglottal closure reflex: characterization in healthy young, elderly and dysphagic patients with predeglutitive aspiration. Gerontology. 2003;49:12–20. doi: 10.1159/000066504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaker R, Ren J, Zamir Z, et al. Effect of aging, position, and temperature on the threshold volume triggering pharyngeal swallows. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:396–402. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishino T. Swallowing as a protective reflex for the upper respiratory tract. Anesthesiology. 1993;79:588–601. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199309000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feyerabend C, Russel MAH. A rapid gas-liquid chromatographic method for the determination of cotinine and nicotine in biological fluids. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1990;42:450–452. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1990.tb06592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Surapaneni S, Dua K, Kuribayashi S, et al. Direct evidence on the role of aerodigestive reflexes in airway protection. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:101–102. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Surapaneni S, Dua K, Kuribayashi S, et al. Mechanism of airway protection against aspiration of refluxate: relationship between critical volume and threshold volume (abstract) Neurogastroenterol & Motil. 2008;20:21. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bujanda L. The effects of alcohol consumption upon the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3374–3382. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boguradzka A, Tarnowski W, Mazurczak-Pluta T. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in hazardous drinkers. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2006;21:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keshavarzian A, Polepalle C, Iber FL, et al. Secondary esophageal contractions are abnormal in chronic alcoholics. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:517–522. doi: 10.1007/BF01307573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott AM, Kellow JE, Shuter B, et al. Effect of cigarette smoking on solid and liquid intragastric distribution and gastric emptying. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:410–416. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson RD, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, et al. Cigarette smoking and rate of gastric emptying: effect on alcohol absorption. Br Med J. 1991;302:20–23. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6767.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahrilas PJ, Gupta RR. Mechanisms of acid reflux associated with cigarette smoking. Gut. 1990;31:4–10. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chattopadhyay DK, Greaney MG, Irvin TT. Effect of cigarette smoking on the lower oesophageal sphincter. Gut. 1977;18:833–835. doi: 10.1136/gut.18.10.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanciu C, Bennett JR. Smoking and gastro-oesophageal reflux. Br Med J. 1972;3:793–795. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5830.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dennish GW, Castell DO. Inhibitory effect of smoking on the lower esophageal sphincter. N Engl J Med. 1971;284:1136–1137. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197105202842007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahal PS, Wright RA. Transdermal nicotine and gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:919–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahrilas PJ, Gupta RR. The effect of cigarette smoking on salivation and oesophageal acid clearance. J Lab Clin Med. 1989;114:431–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rattan S, Goyal RK. Effect of nicotine on the lower esophageal sphincter. Gastroenterology. 1975;69:154–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jack CI, Calverley PM, Donnelly RJ, et al. Simultaneous tracheal and oesophageal pH measurements in asthamatic patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux. Thorax. 1995;50:201–204. doi: 10.1136/thx.50.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hunt JF, Fang K, Malik R, et al. Endogenous airway acidification; implication for asthma pathophysiology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:694–699. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.3.9911005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruth M, Carlsson S, Mansson I, et al. Scintigraphic detection of gastro-pulmonary aspiration in patients with respiratory disorders. Clin Physiol. 1993;13:19–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1993.tb00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keshavarzian A, Polepalle C, Iber FL, et al. Esophageal motor disorder in alcoholics: result of alcoholism or withdrawal? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1990;14:561–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keshavarzian A, Urban G, Sedghi S, et al. Effect of acute ethanol on esophageal motility in cat. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1991;15:116–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keshavarzian A, Zorub O, Sayeed M, et al. Acute ethanol inhibits calcium influxes into esophageal smooth but not striated muscle: a possible mechanism for ethanol-induced inhibition of esophageal contractility. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:1057–1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rogers RL, Meyer JS, Shaw TG, et al. Reductions in regional cerebral blood flow associated with chronic consumption of alcohol. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31:540–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1983.tb02198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lotfi J, Meyer JS. Cerebral hemodynamic and metabolic effects of chronic alcoholism. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1989;1:2–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wetscher GJ, Bagchi D, Perdikis G, et al. In vitro free radical production in rat esophageal mucosa induced by nicotine. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:853–858. doi: 10.1007/BF02064991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orlando RC, Bryson JC, Powell DW. Effect of cigarette smoke on esophageal epithelium of the rabbit. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:1536–1542. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]