Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) in nonhuman primates is a serious menace to the welfare of the animals and human who come into contact with them, while the rapid, accurate, and robust diagnosis is challenging. In this study, we first sought to establish an appropriate primate TB model resembling natural TB in nonhuman primates. Four rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) of Chinese origin were infected intratracheally with two low doses of M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Regardless of the infectious doses, all monkeys were demonstrated to be successfully infected by clinical assessments, tuberculin skin test conversions, peripheral immune responses, gross observations, histopathology analysis, and M. tuberculosis burdens. Furthermore, we extended the usefulness of this model for assessing the following immunodiagnostic antigens: CFP10, ESAT-6, CFP10-ESAT-6, and an antigen cocktail of CFP10 and ESAT-6. The data showed that CFP10 was an M. tuberculosis-specific, “early” antigen used for serodiagnosis of TB in nonhuman primates. In conclusion, we established a useful primate TB model depending on low doses of M .tuberculosis and affording new opportunities for studies of M. tuberculosis disease and diagnostics.

Keywords: infection, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), serodiagnostic antigen

Introduction

Despite drastic measures in controlling tuberculosis (TB) in nonhuman primates (NHPs) maintained on breeding farms [5,6, 16], outbreaks of TB continue to occur in established colonies, with potential serious consequences in term of human exposures, animal losses, disruption of research, and even delayed release of new products into the market [10]. TB in monkeys is difficult to recognize early because infected animals may remain without clinical signs of disease for weeks or months, thus allowing the bacteria to spread through a colony before the index animal is recognized. The tuberculin skin testing (TST), which detects delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) to tuberculin antigens, has been the mainstay of tuberculosis screening and antemortem diagnosis in NHPs since the 1940s, but presents severe limitations [11, 20, 24], such as poor specificity, anergy in reaction, intermittent positive results on repeated TSTs, and even false-negative TST results for animals with obvious radiographic signs of TB. In recent years, many possible auxiliary diagnostic methods for TB have been developed. However, the use of most new diagnostic methods in NHPs still needs further evaluation by appropriate primate TB models.

The NHPs were used extensively for experimental tuberculosis research, documenting the usefulness of this model for diagnostic, pathologic, vaccine, and drugs studies [1, 2, 14, 18]. In general, NHPs are highly susceptible to TB infection; both rhesus (Macaca mulatta) and cynomolgus (Macaca fascicularis) monkeys have been used for TB studies [10, 24]. The infectious dose has ranged from 20 to 105 CFU [4, 13, 18, 24]. The data suggested that at low doses of M. tuberculosis(<1000 CFU), monkeys could usually control the infection and present no clinical symptoms, however, a larger dose (≥3000 CFU) always caused progressive disease, indicating that the types of NHP TB models largely depended on the doses of M. tuberculosis used for infection. The majority of naturally TB-positive NHPs is asymptomatically infected, so the relevant model for the study of new diagnostic methods or targets should be an asymptomatic TB model. Based on the above documented data, we set out to develop a NHP model of TB that resembled the possible outcomes of natural TB in NHPs, with the goal of having a system to study diagnosis of TB. We report here that we have established a useful primate TB model without obvious clinical signs that is useful for the evaluation of immunodiagnostic antigens.

Materials and Methods

Animals and anesthesia

The four animals (06-1519R, 06-1523R, 06-1411R, and 06-1445R) used in this study were rhesus monkeys of Chinese origin obtained from Gaoyao Kangyuan Laboratory Animal Science & Technology Co., Ltd. [License No.: SCXK (Yue) 2009–0009] and routinely tested negative for monkey B virus, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), and simian T-cell leukemia virus 1 (STLV-1) by ELISA and simian retrovirus (SRV) by immunofluorescence. After arrival at the facility, the monkeys were quarantined for one month, and were evaluated extensively for the absence of tuberculosis by biweekly repeated TSTs during the quarantine period. Monkeys were anesthetized intramuscularly with ketamine in combination with xylazine for M. tuberculosis infection, blood sample collection, administration of the skin test, and necropsy.

Another two animals (06-1885R and 06-1891R) with the same background as above were used as controls and only received repeated TSTs biweekly for 20 weeks to identify whether repeated TSTs would affect serum antibody responses and cytokines. This work was performed in a common laboratory.

Animal use protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Guangdong Laboratory Animal Monitoring Institute in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [19]. Work related to infection of the animals was conducted using biosafety level-3 operating procedures and policies in a biosafety level-3 animal facility with approval of and oversight by the local provincial institutional environmental health and safety office. All animals had never been used for any experimental procedures previously.

M. tuberculosis and experimental infection

M. tuberculosis H37Rv was cultured in Middlebrook 7H9 at 37°C for 6 weeks. After harvesting, the cultures were dispersed with ultrasound, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C. When used for infection, thawed bacilli were pelleted at 4,500 rpm for 15 min, and resuspended in PBS at two concentrations. At the same time, bacteria were counted in a Petroff-Hauser chamber, and viability was determined by enumerating CFU in serially diluted samples on 7H10 agar plates. Results showed that the viability was nearly a hundred percent and that the two inoculums reached 25 and 250 CFU/ml respectively.

After anesthesia, monkeys 06-1519R and 06-1523R received 500 CFU of M. tuberculosis H37Rv by intratracheal installation of 2 ml of the bacterial suspension followed by 1 ml of natural saline to flush the catheter, and monkeys 06-1411R and 06-1445R received 50 CFU of M. tuberculosis H37Rv by the same route.

Clinical assessment

Animals were observed daily throughout the study for alterations in behavior, appetite, and coughing. Body weights were recorded monthly. Every 2 to 4 weeks, 10 ml blood samples were obtained via femoral venipuncture for clinical hematology (0.5 ml), flow cytometry analysis (1 ml), and immunology (the remaining volume) of sera by centrifugation, which were stored frozen at −80°C.

Tuberculin and tuberculin skin testing (TST) procedures

Old tuberculin (OT) from Synbiotics Corp. and purified protein derivative (PPD) from Harbin Pharmaceutical Group Bio-vaccine Co., Ltd. were used in TSTs. For easy to visualization of the results of the TSTs without anesthetizing or restraining the animals, the palpebral area was chosen as the place for TSTs in this study. Intradermal palpebral skin testing was performed using 0.1 ml of OT in the right palpebra and 0.1 ml of PPD in the left palpebra respectively every 2 to 4 weeks after blood sample collection. Palpebral reactions were graded at 24, 48, and 72 h with the standard 1 to 5 scoring system [4], and in this study, reactions of grades 0–2 were considered negative, those of grades 2–3 were considered suspect, and those of grades ≥3 were considered positive.

Cytokine measurement in plasma

TNF-α, IL-8, IL-12/23p40, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-10 were measured with a standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The kits for IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-12 assays were purchased from Mabtech, Inc. (Mariemont, OH, USA), and those for IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α were purchased from Bender MedSystems, Inc. (Burlingame, CA).

Necropsy and histological analysis

Approximately 26 weeks post infection, monkeys 06-1519R (500 CFU) and 06-1411R (50 CFU) were euthanized intramuscularly with overdoses of ketamine in combination with Sumianxin II (Xylazine). About 19 weeks later, monkeys 06-1523R (500 CFU) and 06-1445R (50 CFU) were treated as above. All blood was collected via carotid route. Various tissues (lung, liver, spleen, kidneys, heart, lymph nodes, and brain) were collected for gross observation and microscopic examination. Gross observation was evaluated by scoring based on the number and extent of lesions present in those organs as previously described [7, 18].

Selected pieces of pulmonary, lymphatic, and other organ tissues were preserved in 10% formalin, routinely processed, and embedded in paraffin. Standard 5-µm sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Histopathological slides were evaluated by a scoring system described previously [13] with a slight modification. In this study, every lobe of the lungs was evaluated to obtain the sum score of all lung lobes.

M. tuberculosis burdens

To enumerate M. tuberculosis burdens, weighed samples of organs obtained at necropsy were minced and plated on Middlebrook 7H10 agar plates. For the lung and liver, half of each lobe with approximately 50% of the lesions was taken for CFU determination after extensive gross pathologic evaluation was accomplished. For other organs, half of the tissue was taken too. If there were no visible lesions in the lobes or organs, a random half of tissue was taken for evaluation.

Evaluation of serodiagnostic antigens

Three kinds of recombinant M. tuberculosis proteins (Table 1) purified to homogeneity from Escherichia coli were used as coating antigens for indirect ELISA to test serial serum samples of infected monkeys. The time course of antibody responses, the time to antibody detection, and the association between the outcomes of infection and antibody responses were analyzed respectively.

Table 1. Recombinant protein antigens of M. tuberculosis used in this study.

| Antigens | Rv no. of gene | Molecular mass (kDa) | Expression vector | Coating concentration | Serum dilution | Responders | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFP101) | Rv3874 | 11 | pET-24b | 0.5 μg/ml | 1:20 | 4 (100%) | [25] |

| ESAT-62) | Rv3875 | 6 | pET-24b | 1 μg/ml | 1:20 | 2 (50%) | [25] |

| CFP10-ESAT-63) | Rv3874/Rv3875 | 66 | pET-28a | 0.5 μg/ml | 1:20 | 4 (100%) | |

| Cocktail (CFP10 & ESAT-6) | Rv3874/Rv3875 | pET-24b | 0.5 & 1 μg/ml | 1:20 | 4 (100%) |

1)CFP10, culture filtrate protein 10 of M. tuberculosis. 2)ESAT-6, 6-kDa early secretory antigenic target of M. tuberculosis. 3)CFP10-ESAT-6, fusion protein of CFP10 and ESAT-6.

The ELISA procedure was performed as follows: 96-well polystyrene microtitration plates were coated overnight at 4°C with 100 µl antigen solution in 0.1 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH9.6). After coating and being washed, all wells were blocked with 150µl 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS at 37°C for 1h. After being washed again, the wells were filled with 100µl serum samples diluted in PBS and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After the plates were washed, they were incubated at 37°C for 1 h with 100 µl goat anti-monkey IgG antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) diluted 1:15,000. Enzyme activity was assayed with TMB peroxidase substrate (Dream Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Guangdong, P.R. China). To terminate the reaction, 50 µl of 2 M sulfuric acid was added, and then the optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm (OD450) in an automatic microplate reader (Bio-Rad.co.JP). Mixtures of 10 naturally TST-positive sera and 10 naturally TST-negative sera were set as the positive and negative controls respectively.

Results

Clinical observation

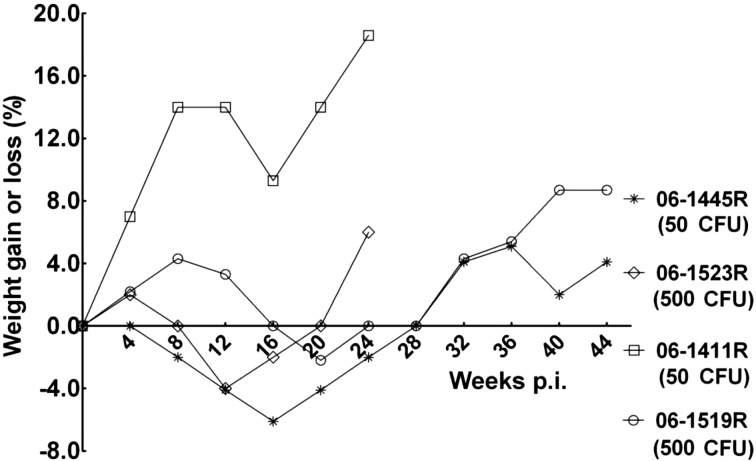

No obvious clinical symptoms were observed except occasional cough for all monkeys after infection (Table 2). Three monkeys, except 06-1411R (50 CFU), began to show delicate appetite at week 4 post infection, and all four animals showed delicate appetite at 8 to 16 weeks post infection. Feed intake decreased by about one-fourth to one-third. Animals showed a peak decrease in body weights associated with appetite, but the weight losses were no more than 6% of their starting body weights, and all animals were found to have gained weights at necropsy compared with the start of the infection (Fig. 1).

Table 2. The outcomes of monkeys experimentally infected with M. tuberculosis.

| Animal | 06-1523R (500 CFU) | 06-1411R (50 CFU) | 06-1519R (500 CFU) | 06-1445R (50 CFU) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical results | Occasional cough | Normal | Normal | Normal | |

| TST-positive at week | 4 | 6 | 4 | 4 | |

| Week of necropsy | 26 | 26 | 45 | 45 | |

| Gross observation1) | |||||

| Hilar lymph nodes | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |

| Lung | 17 | 8 | 0 | 4 | |

| Spleen | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Histopathology2) | |||||

| Hilar lymph nodes | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Lung | 15 | 11 | 7 | 11 | |

| Spleen | 2 | 0 | 0 | 13) | |

| Kidney | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Tissue (logCFU/g) | |||||

| Hilar lymph nodes | 4.3 | 4.1 | 2.3 | 2.9 | |

| Lung | 2.4 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | |

| Spleen | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

1)Scoring for gross pathology [7, 18]. Hilar lymph nodes: 0, visible but not enlarged; 1, visibly enlarged unilaterally (≤2 cm); 2, visibly enlarged bilaterally (≤2 cm); 3, visibly enlarged unilaterally or bilaterally >2 cm, respectively. Lung and extrapulmonary organs: 0, no visible lesion; 1, 1 gross lesion <10 mm diameter; 2, 2–5 gross lesions <10 mm diameter, or calcification; 3, >6 gross lesions <10 mm diameter or 1 lesion >10 mm diameter; 4, >1 gross lesion >10 mm diameter; 5, gross coalescing lesions. TB lesions in lungs were scored for each lobe of lung, and the other extrapulmonary organs were scored for the whole organs. 2)Histopathology key [13]: 0, normal; 1, minimal; 2, mild; 3, moderate; 4, severe. The scores of the lung were the sums of all lobes, and each lobe was scored by the above scoring system. 3)It was not the classic indications of disease but indications of immune suppression.

Fig. 1.

Body weight changes. Body weights of the monkeys were monitored monthly after M. tuberculosis infection. The net weight gain or loss post infection was compared with the weight at the time point (0 week) of infection.

TST results

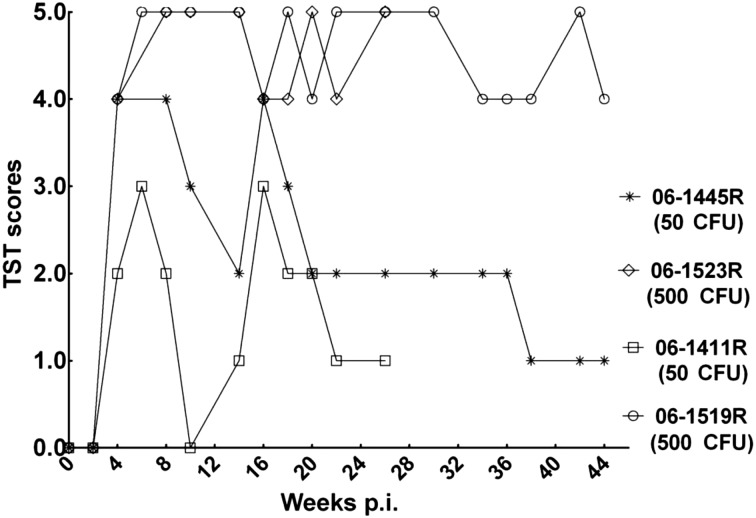

At week 4 post infection, intrapalpebral reactions were positive for three infected monkeys and suspected for monkey 06-1411R (50 CFU). All infected animals tested positive at week 6 post infection. Afterward, intrapalpebral reactions in monkeys 06-1523R (500 CFU) and 06-1519R (500 CFU) were strongly positive (graded 4–5) during the whole infection period, while monkeys 06-1445R (50 CFU) and 06-1411R (50 CFU) gave intermittent positive results 6 weeks post infection and never showed positive intrapalpebral reactions after 20 weeks post infection (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Results of repeated TSTs. The high-dose animals (06-1523R and 06-1519R) presented strong skin reactions graded ≥4 scores, and the low-dose animals (06-1445R and 06-1411R) only gave intermittent positive results during the infection period.

The control monkeys (06-1885R and 06-1891R) presented no positive or suspect reactions for repeated TSTs.

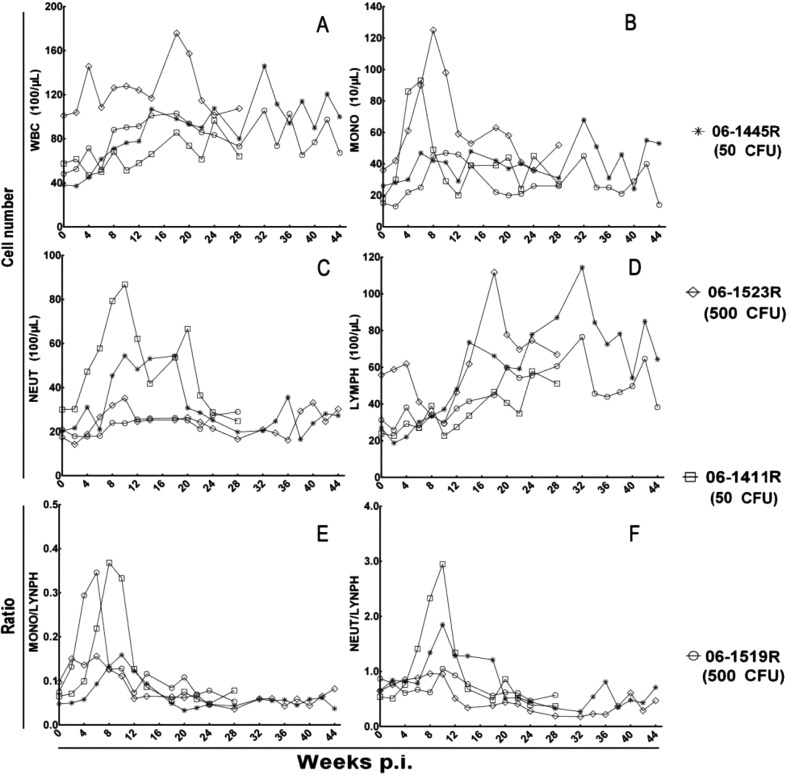

Total leukocyte and leukocyte populations

There was no significant change in total leukocyte count, but there was a slow time-dependent increase during the infection period (Fig. 3, A). The monocytes and neutrophiles showed an obvious distinctive characteristics, and their numbers declined to preinfection levels after a brief peak and remained like that from week 2 to week 24 postinfection (Fig. 3B, C). Three animals, except 06-1523R (500 CFU), exhibited a consistent increase of several folds in the numbers of lymphocytes after the infection, while the monkey 06-1523R (500 CFU) showed an initial increase in lymphocytes and then an increase following the initial downregulation.

Fig. 3.

Profiles of total leukocyte and leukocyte populations. Changes in (A) total number of WBCs, (B) number of monocytes, (C) number of neutrophiles, (D) number of lymphocytes, (E) Monocyte-lymphocyte ratio, and (F) neutrophile-lymphocyte ratio.

The monocyte-lymphocyte ratio and neutrophile-lymphocyte ratio were calculated from the numbers of monocytes, neutrophiles, and lymphocytes. A significant transient increase in monocyte-lymphocyte ratio occurred in monkeys 06-1519R (500 CFU) and 06-1411R (50 CFU) at an early stage of infection followed by recovery and maintenance of a normal ratio, and this occurred for the monocyte-lymphocyte ratio in monkeys 06-1445R (50 CFU) and 06-1411R (50 CFU) too. The changes in the two ratios in remaining animals were mild, or there was no obvious elevation during the infection course.

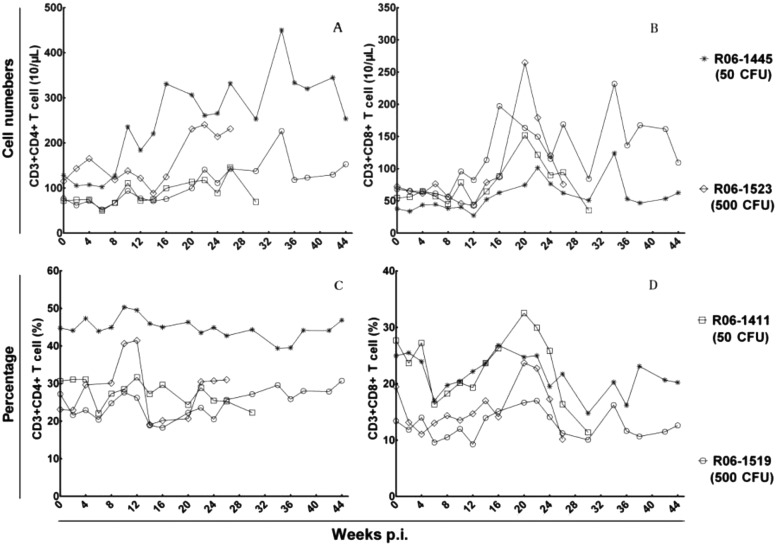

Peripheral T lymphocyte subsets

The dynamic changes in peripheral T lymphocyte subsets were various for infected monkeys (Fig. 4). Monkey 06-1445R (50 CFU) experienced substantial increases in numbers of peripheral CD4+ T cells during the infection course, while the other monkeys only showed a moderate time-dependent increase. The CD8+ T cell numbers of all monkeys began to rise at week 10 post infection followed by multiple peaks during the infection course, while the percentage of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells showed no significant changes. There was no obvious association between the infectious doses of M. tuberculosis and the elevated levels of peripheral T cell numbers.

Fig. 4.

Profiles of peripheral T lymphocyte populations. The dynamic changes of (A) CD4+ T cell numbers, (B) CD8+ T cell numbers, (C) CD4+ T cell percent, and (D) CD8+ T cell percent.

Serum cytokines in response to M. tuberculosis

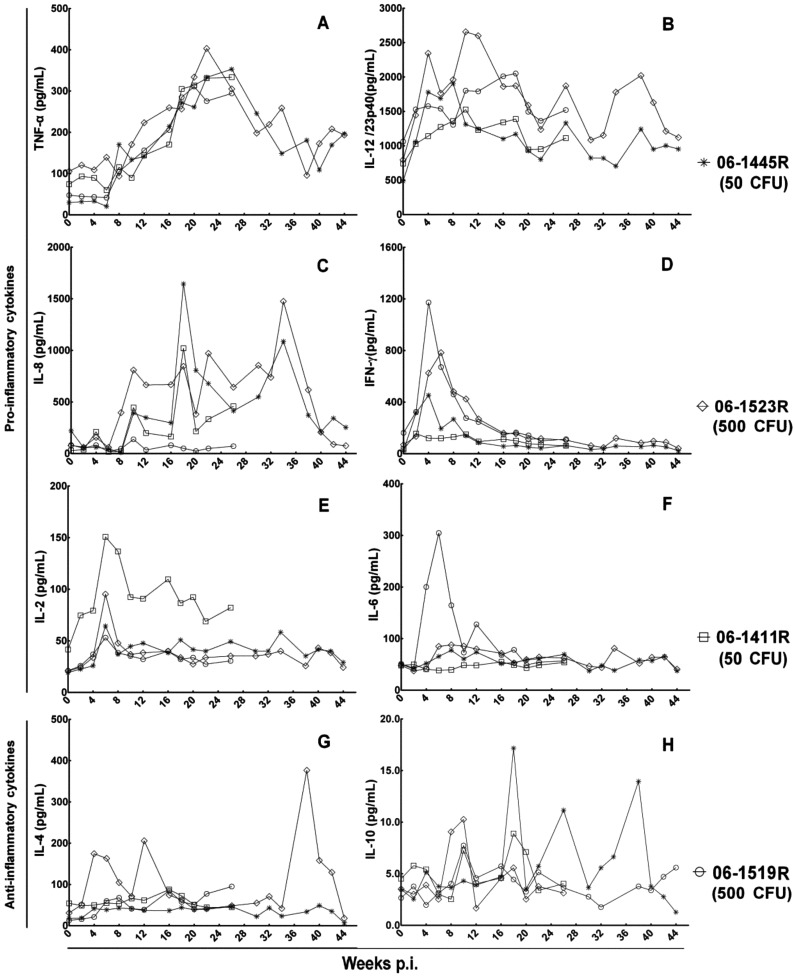

In present study, we detected 6 serum pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-12/23p40, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-6, and IL-8) and 2 serum anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4 and IL-10).

Serum pro-inflammatory cytokines were characterized by variant increases during the infection course (Fig. 5, A–F). The increase in TNF-α was detected as early as 8 weeks, and a sharp peak was observed at week 18 to 24 post infection, which was followed by a significant decrease to near baseline. The serum levels of IL-12/23p40 for all animals began to increase at week 2 post infection. As infection progressed, serum IL-12/23p40 showed multipeak kinetics in all animals and maintained high levels at most time during infection. The levels of IL-8 increased at week 8 post infection and present multipeak kinetics too. The changes in IFN-γ and IL-2 were similar and only presented a significant transient increase at the early stage of infection. For IL-6, only the monkey 06-1523R (500 CFU) showed a significant peak at week 6 post infection.

Fig. 5.

Profiles of serum cytokines. (A)–(E) show various increases in serum pro-inflammatory cytokines. (G), (H) show nonspecific changes in serum anti-inflammatory cytokines.

For 2 serum anti-inflammatory cytokines, no specific changes for TB infection were observed during the infection course (Fig. 5, G–H). For IL-4, monkey 06-1519R (500 CFU) showed two peaks at the early stage and one peak at the end of infection, and other animals showed baseline levels all the time. For IL-10, animals showed only multipeak kinetics at low levels.

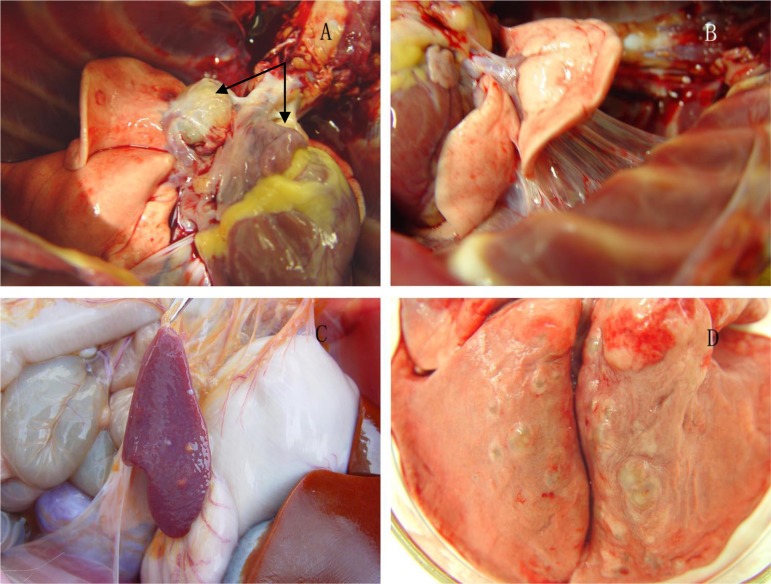

Gross pathology

At necropsy, each monkey was scored for lesions in all lung lobes and extrapulmonary organs according to gross pathology scoring systems described in Materials and Methods (Table 2). The score proportionately reflects the extent of gross pathology observed during necropsy.

Coalescing solid, enlargement and classic caseous appearance upon dissection were seen in hilar lymph nodes of all monkeys (Fig. 6, A). While the lesions in lung lobes and extrapulmonary sites were not similar to each other. In monkey 06-1523R (500 CFU), a large amount of fibrin exudation resulted in adhesion of the left middle lung lobe to the inner chest wall and adjacent lung lobes (Fig. 6, B), and the middle lobe showed consolidation and caseous changes upon dissection. Compared with left lung lobes, there were only a few lesions distributed in right lung lobes. Of the extrapulmonary organs, only the spleen showed lesions on the surface and upon dissection, although there were few (Fig. 6, C). In monkey 06-1519R (500 CFU), no obvious lesions were observed in any lung lobes and extrapulmonary organs. Monkey 06-1411R (50 CFU) demonstrated miliary lesions, from 1 to 12, in most of lung lobes (Fig. 6, D), but without extrapulmonary involvement. In monkey 06-1445R (50 CFU), only few lesions were observed in left and right lower lobes; in addition, splenic atrophy was obvious compared with the other monkeys.

Fig. 6.

Gross pathology. (A) Visibly enlarged hilar lymph nodes bilaterally in monkey 06-1411R (50 CFU). (B) Fibrin exudation and adhesion in the left middle lung lobe of monkey 06-1523R (500 CFU). (C) Several small gross lesions distributed on the surface of the spleen in monkey 06-1523R (500 CFU). (D) Miliary lesions in the lung of monkey 06-1411R (50 CFU).

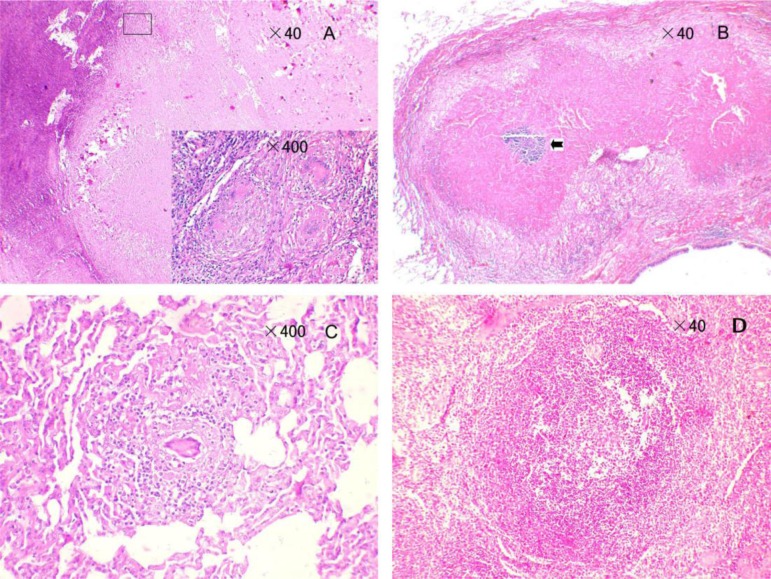

Histological analysis

On histological examination, massive pathologic changes were observed in hilar lymph nodes of all infected animals. Caseous granulomas and mineralized granulomas were present in hilar lymph nodes, and a margin of epithelioid macrophages and Langhans giant cells were seen surrounding the necrotic center (Fig. 7, A).

Fig. 7.

Histological findings. (A) Coalescing granulomas in hilar lymph nodes with a margin of epithelioid macrophages and Langhans giant cells. (B) Coalescing granulomas in the lung of 06-1445R (50 CFU); the mineralized center is indicated by an arrow. (C) Nonnecrotic granulomas in the lung of monkey 06-1519R (500 CFU). (D) Nonnecrotic granulomas of the spleen in monkey 06-1445R (50 CFU).

Based on microscopic histopathology characteristics, a variety of granuloma types can be seen within the lungs of monkeys 06-1411R (50 CFU), 06-1523R (500 CFU), and 06-1445R (50 CFU), i.e. coalescing granulomas of several caseous granulomas with central necrosis and widespread zones (Fig. 7, B), and nonnecrotic granulomas comprised of a central core of densely packed epithelioid macrophages with occasional neutrophils and multinucleated giant cells, usually with a thin outer rim of lymphocytes but no caseous necrotic debris. Additionally, interstitial pneumonia with abundant macrophages in the alveolus wall and without necrotic foci was seen in a background of multicentric. For monkey 06-1519R (500 CFU), there were no lesions in lung lobes according to gross observation, but histological analysis revealed dissemination of nonnecrotic granulomas in multiple lobes (Fig. 7, C), and granulomatous inflammation was also present.

Although multiple types of granulomas were commonly seen in lung lobes and hilar lymph nodes, they were rarely observed in extrapulmonary organs, and only monkey 06-1523R (500 CFU) showed a few nonnecrotic granulomas in the spleen. Granulomas were not present in other organs of all animals based on careful screening. Another important finding was the abnormal spleen white pulp morphology in monkey 06-1445R (50 CFU), the periarteriolar lymphocyte sheaths were clear with diffuse lymphatic tissue, but no germinal centers were present within the spleen (Fig. 7, D). The germinal center is a special place for clones of B-lymphocytes, so we can conclude that the monkey has a lower humoral immunity compared with other monkeys.

M. tuberculosis burdens

Two monkeys [06-1523R (500 CFU) and 06-1411R (50 CFU)] that euthanized earlier presented with similar high CFU scores. In contrast, the last two monkeys [06-1519R (500 CFU) and 06-1445R (50 CFU)] presented with much lower CFU scores compared with the earlier ones (Table 2). No positive correlation between infectious doses and CFU scores was found from the results, but there was a time-dependent decrease in the CFU scores in the same organs. As infection progressed, more and more bacteria were cleared by the immune system of monkeys. Specimens of heart, liver, kidneys, and brain from all four monkeys were negative for M. tuberculosis, and only the spleen specimen of monkey 06-1523R (500 CFU) was positive.

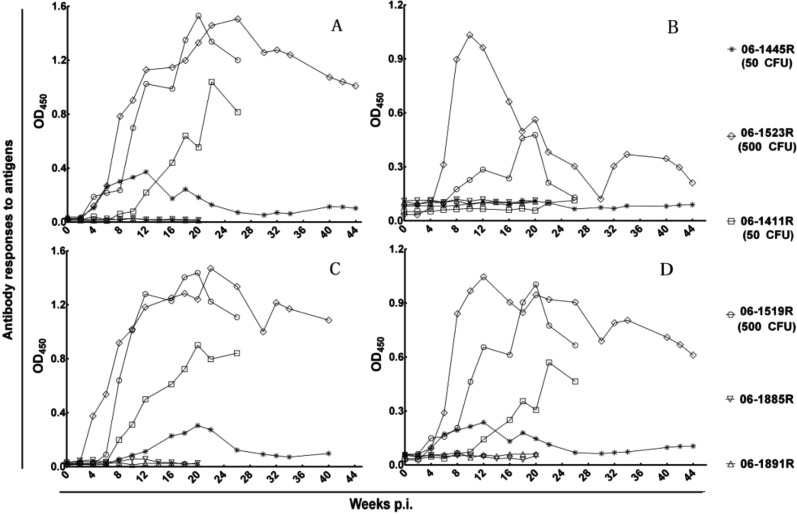

Characterization of antibody responses to serodiagnostic antigens

Sequential serum samples were tested against CFP10, ESAT-6, CFP10-ESAT-6, and the antigen cocktail (CFP10 and ESAT-6) by use of indirect ELISA to identify the antibody responses of infected monkeys. CFP10, CFP10-ESAT-6, and the antigen cocktail could be recognized by serum antibodies of all animals from at least one time point during the course of infection, while ESAT-6 could only be recognized by 2 high-dose monkeys [06-1523R (500 CFU) and 06-1519R (500 CFU)] (Table 1). For control monkeys (06-1885R and 06-1891R), the antibodies to the above antigens maintained baseline levels during the whole experiment period.

We next analyzed the time course of the antibody responses against selected antigens. Data obtained for all animals in every antigen are presented in Fig. 8. The results of antibody response characterization for CFP10, CFP10-ESAT-6, and the antigen cocktail were similar to each other. Serum antibodies to these antigens were detected as early as 4 or 6 weeks post infection, thereafter, the time-dependent increase in antibody levels were terminated at week 20 to 26 post infection, and this was followed by a slow decline in monkeys 06-1523R (500 CFU), 06-1519R (500 CFU), and 06-1411R (50 CFU). While serum antibodies to these antigens in monkey 06-1445R (50 CFU) had distinctive characteristics, antibodies to these antigens in this animal presented only a brief peak and declined to preinfection levels during the infection period. Additionally, the low-dose monkeys [06-1411R (50 CFU) and 06-1445R (50 CFU)] presented negative antibody responses to ESAT-6. The high-dose monkey 06-1519R (500 CFU) presented an initial sharp peak in the antibody responses to ESAT-6 and declined to the nadir followed by a slight recovery. The results of antibody response characterization for ESAT-6 in monkey 06-1523R (500 CFU) resembled those of monkey 06-1519R (500 CFU), but they were moderate, and the antibody level was lower.

Fig. 8.

Antibody response characterizations. The time course of antibody responses to (A) CFP10, (B) ESAT-6, (C) CFP10-ESAT-6, and (D) antigen cocktail of CFP10 and ESAT-6.

Discussion

With the development of techniques in molecular biology and immunology, many potential antigens and possible auxiliary diagnostic methods have been developed, but most of them still need further evaluation by appropriate primate TB models. An ideal model for assessing new antigens and diagnostic methods should highly resemble natural NHP TB, especially the outcomes of infection. So the relevant model would like to be an asymptomatic TB model, as the majority of naturally TB-positive NHPs are asymptomatically infected. This study developed and characterized a primate TB model that resembled natural TB in NHPs and assessed the immunodiagnostic potentials of several M. tuberculosis-specific antigens.

NHP TB models have a long history and have been used for many years for vaccine and drug testing studies, because of the close phylogenetic relationship between humans and NHPs, the well characterized immune system, and the similarity of outcomes of TB infection. Reports have also indicated rhesus monkeys are more susceptible to M. tuberculosis than other experimental monkeys [10, 13, 22, 23], such as cynomolgus monkeys, and develop a course of infection that highly resembles that in man. In this study, we treated rhesus monkeys from China with the M. tuberculosis H37Rv strain and provided compelling evidence demonstrating an asymptomatic TB model different from another recently reported model rhesus monkeys from China [25]. Regardless of the infectious doses of M. tuberculosis, all animals developed no significant clinical signs of M. tuberculosis infection except moderate staggered anorexia and weight loss during the early course of infection. In addition, lots of studies support the finding that the outcome of infection is dose dependent, and large infectious doses may result in rapidly progressive disease [4, 24, 25]. Unlike those studies, the gross and histological changes of infection in our study showed no obvious dose dependency, while the palpebral TST reactions and antibody levels were dose dependent. The monocyte-lymphocyte ratio and neutrophile-lymphocyte ratio in the peripheral blood, which have been thought to be a significant factor in tuberculosis [21], showed only a peak during the infection course, demonstrating that few secondary infections occurred after the primary infection. The pro-inflammatory cytokines were induced and the anti-inflammatory cytokines were suppressed in this study, also suggesting few secondary infections.

As the mainstay of tuberculosis screening in routine quarantine and antemortem diagnosis in NHPs, TST has a number of the well-documented limitations with regard to sensitivity and specificity that reduce its utility as a standalone test, such as intermittently positive reactions in repeated TSTs, false-negative TST results, and anergy reaction in TST [11, 20, 24]. In this study, after infection, the model was firstly used to evaluate the effect of repeated palpebral TSTs on immunodiagnostics at the intervals of 2 to 4 weeks. Monkeys (06-1519R and 06-1523R) infected with 500 CFU M. tuberculosis H37Rv became TST-positive within 4 weeks and retained strong reactions for the duration of study, while the monkeys (06-1445R and 06-1411R) infected with 50 CFU M. tuberculosis H37Rv only gave intermittently positive results. Monkey 06-1445R (50 CFU) showed two peaks of reactions at the interval of 8 weeks before week 20 post infection and thereafter eventually gave negative TST results, and the interval for monkey 06-1411R (50 CFU) were 10 weeks. The model demonstrated the chief limitations of TST in documents and the new finding that outcomes of TSTs were dose dependent. Also in routine animal quarantine, maintaining a sufficiently interval between TSTs may produce optimal results, such as quarter quarantine and annual quarantine.

Earlier efforts to detect antibodies based on PPD, were limited mainly by insufficient specificity and cross-reactivity with mycobacterial species [9, 12]. Recently, the identifications of secreted proteins that are specific to M. tuberculosis have been facilitated by advances in the sequencing of M. tuberculosis [8, 12]. Among them, ESAT-6 and CFP10 are highly immunogenic and show great potentials in TB immunodiagnostics [3, 15, 17], but several questions still remain open, including (i) whether it is possible to shorten the time to antibody detection and (ii) whether the antibody repertoire reflects the outcomes of infection. Here, we characterized the dynamic antibody responses of CFP10, ESAT-6, CFP10-ESAT-6, and the cocktail of CFP10 and ESAT-6 in experimentally infected rhesus monkeys. An important result obtained from this study was the specific CFP10 antigen-antibody response. Serum antibody to this antigen could be detected out as early as week 4 post infection and all animals were seropositive at at least one time point during the course of infection. The results of antibody response characterizations of CFP10-ESAT-6 and the antigen cocktail highly resembled those of CFP10. As opposed to previous studies on ESAT-6 [3, 15, 17], ESAT-6 in our study showed poor sensitivity and a short time course of antibody response, and only two monkeys [06-1519R (500 CFU) & 06-1523R (500 CFU)] were seropositive to this antigen. A second significant result, that the antibodies levels were dose dependent, could be drawn from our ELISA results, and this has rarely been reported in previous studies. Kunnath-Velayudhan, et al. demonstrated that macaque outcome groups were associated with distinct antibody profiles: early, transient responses in latent infection and stable antibody increase in active and reactivation disease [17]. According to the above report, monkey 06-1445R (50 CFU) had a latent infection due to transient antibody responses, while the other monkeys were experiencing active and reactivation disease. Besides, antibody repertoires showed significant positive correlation with TST reactions, but no significant correlation with M. tuberculosis burdens and gross and histological changes in our study.

To clarify whether repeated TSTs affect the antibody responses, we selected two animals (06-1885R and 06-1891R) to receive only repeated TSTs biweekly for 20 weeks and detected the antibodies in sequential sera. The antibodies to four antigens remained at baseline levels at all time points, indicating that there were no effects on antibody responses in healthy monkeys caused by repeated TSTs.

In conclusion, we established an asymptomatic TB model in rhesus monkeys that was useful for assessing the immunodiagnostic antigens and methods. The secretion of ESAT-6, which is critical to the virulence of M. tuberculosis and regarded as an ideal candidate for immunodiagnostics and vaccines, shows a poor antibody level and short time course of antibody response, while the secretion of CFP10 demonstrates a specific antibody response, indicating its high potential in NHP TB diagnosis, but it still needs further identification in more naturally TB-positive monkeys.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants 2005B60302002, 2006B20801004, and 2009B060300017 of Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Project and the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Laboratory Animals (grant 2007B060101002).

We are grateful to Professor Wende Li of Guangdong Medical College for expert technical assistance and helpful discussions.

References

- 1.Anacker R.L., Brehmer W., Barclay W.R., Leif W.R., Ribi E., Simmons J.H., Smith A.W.1972. Superiority of intravenously administered BCG and BCG cell walls in protecting rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) against airborne tuberculosis. Z. Immunitatsforsch. Exp. Klin. Immunol. 143: 363–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barclay W.R., Busey W.M., Dalgard D.W., Good R.C., Janicki B.W., Kasik J.E., Ribi E., Ulrich C.E., Wolinsky E.1973. Protection of monkeys against airborne tuberculosis by aerosol vaccination with Bacillus Calmette-Guerin. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 107: 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brusasca P.N., Peters R.L., Motzel S.L., Klein H.J., Gennaro M.L.2003. Antigen recognition by serum antibodies in non-human primates experimentally infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Comp. Med. 53: 165–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capuano S.V.3rd.,, Croix D.A., Pawar S., Zinovik A., Myers A., Lin P.L., Bissel S., Fuhrman C., Klein E., Flynn J.L.2003. Experimental Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of cynomolgus macaques closely resembles the various manifestations of human M. tuberculosis infection. Infect. Immun. 71: 5831–5844. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5831-5844.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC.1991. Update: nonhuman primate importation. MMWR 40: 684–685, 691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC.1993. Tuberculosis in imported nonhuman primates: United States, June 1990-May 1993. MMWR 42: 572–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C.Y., Huang D., Wang R.C., Shen L., Zeng G., Yao S., Shen Y., Halliday L., Fortman J., McAllister M., Estep J., Hunt R., Vasconcelos D., Du G., Porcelli S.A., Larsen M.H., Jacobs W.R., Jr, Haynes B.F., Letvin N.L., Chen Z.W.2009. A Critical Role for CD8 T Cells in a Nonhuman Primate Model of Tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 5: e1000392. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole S.T., Brosch R., Parkhill J., Garnier T., Churcher C., Harris D., Gordon S.V., Eiglmeier K., Gas S., Barry C.E. 3rd., Tekaia F., Badcock K., Basham D., Brown D., Chillingworth T., Connor R., Davies R., Devlin K., Feltwell T., Gentles S., Hamlin N., Holroyd S., Hornsby T., Jagels K., Krogh A., McLean J., Moule S., Murphy L., Oliver K., Osborne J., Quail M.A., Rajandream M.A., Rogers J., Rutter S., Seeger K., Skelton J., Squares R., Squares S., Sulston J.E., Taylor K., Whitehead S., Barrell B.G.1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393: 537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corcoran K.D., Thoen C.O.1991. Application of an enzyme immunoassay for detecting antibodies in sera of Macaca fascicularis naturally exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Med. Primatol. 20: 404–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia M.A., Bouley D.M., Larson M.J., Lifland B., Moorhead R., Simkins M.D., Borie D.C., Tolwani R., Otto G.2004. Outbreak of Mycobacterium bovis in a conditioned colony of rhesus (Macaca mulatta) and cynomolgus (Macaca fascicularis) macaques. Comp. Med. 54: 578–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia M.A., Yee J., Bouley D.M., Moorhead R., Lerche N.W.2004. Diagnosis of tuberculosis in macaques, using whole-blood in vitro interferon-gamma (PRIMAGAM) testing. Comp. Med. 54: 86–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garnier T., Eiglmeier K., Camus J.C., Medina N., Mansoor H., Pryor M., Duthoy S., Grondin S., Lacroix C., Monsempe C., Simon S., Harris B., Atkin R., Doggett J., Mayes R., Keating L., Wheeler P.R., Parkhill J., Barrell B.G., Cole S.T., Gordon S.V., Hewinson R.G.2003. The complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium bovis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100: 7877–7882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1130426100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gormus B.J., Blanchard J.L., Alvarez X.H., Didier P.J.2004. Evidence for a rhesus monkey model of asymptomatic tuberculosis. J. Med. Primatol. 33: 134–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2004.00062.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta U.D., Katoch V.M.2005. Animal models of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 85: 277–293. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2005.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanaujia G.V., Motzel S., Garcia M.A., Andersen P., Gennaro M.L.2004. Recognition of ESAT-6 sequences by antibodies in sera of tuberculous nonhuman primates. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 11: 222–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaufmann A.F.1971. A program for surveillance of nonhuman primate disease. Lab. Anim. Sci. 21: 1061–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunnath-Velayudhan S., Davidow A.L., Wang H.Y., Molina D.M., Huynh V.T., Salamon H., Pine R., Michel G., Perkins M.D., Xiaowu L., Felgner P.L., Flynn J.L., Catanzaro A., Gennaro M.L.2012. Proteome-scale antibody responses and outcome of mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in nonhuman primates and in tuberculosis patients. J. Infect. Dis. 206: 697–705. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langermans J.A.M., Doherty T.M., Vervenne R.A.W., van der Laan T., Lyashchenko K., Greenwald R., Agger E.M., Aagaard C., Weiler H., van Soolingen D., Dalemans W., Thomas A.W., Andersen P.2005. Protection of macaques against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by a subunit vaccine based on a fusion protein of antigen 85B and ESAT-6. Vaccine 23: 2740–2750. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.11.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Research Council.2010. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th ed., National Academy Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Reilly L.M.1995. Tuberculin skin tests: sensitivity and specificity, pp. 85–91. In:Mycobacterium bovis Infection in Animals and Humans. (Thoen, C.O., and Steele, J.H., eds.), Iowa State University Press, Ames. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smithburn K.C., Sabin F.R., Hummel L.E.1937. Haematological studies in experimental tuberculosis: variations in the blood cells of rabbits inoculated with cultures differing in virulence. Am. Rev. Tuberc. 36: 673–691 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugawara I., Li Z., Sun L., Udagawa T., Taniyama T.2007. Recombinant BCG Tokyo (Ag85A) protects cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) infected with H37Rv Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 87: 518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2007.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugawara I., Sun L., Mizuno S., Taniyama T.2009. Protective efficacy of recombinant BCG Tokyo (Ag85A) in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) infected intratracheally with H37Rv Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 89: 62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2008.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh G.P., Tan E.V., dela Cruz E.C., Abalos R.M., Villahermosa L.G., Young L.J., Cellona R.V., Nazareno J.B., Horwitz M.A.1996. The Philippine cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) provides a new nonhuman primate model of tuberculosis that resembles human disease. Nat. Med. 2: 430–436. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J., Ye Y.Q., Wang Y., Mo P.Z., Xian Q.Y., Rao Y., Bao R., Dai M., Liu J.Y., Guo M., Wang X., Huang Z.X., Sun L.H., Tang Z.J., Ho W.Z.2011. M. tuberculosis H37Rv infection of Chinese Rhesus Macaques. J. Neuroimmune. Pharmacol. 6: 362–370. doi: 10.1007/s11481-010-9245-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]