Abstract

The defining anatomical feature of Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the degeneration of substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) neurons, resulting in striatal dopamine (DA) deficiency and in the subsequent alteration of basal ganglia physiology. Treatments targeting the dopaminergic system alleviate PD symptoms but are not able to slow the neurodegenerative process that underlies PD progression. The nucleus striatum comprises a complex network of projecting neurons and interneurons that integrates different neural signals to modulate the activity of the basal ganglia circuitry. In this review we describe new potential molecular and synaptic striatal targets for the development of both symptomatic and neuroprotective strategies for PD. In particular, we focus on the interaction between adenosine A2A receptors and dopamine D2 receptors, on the role of a correct assembly of NMDA receptors, and on the sGC/cGMP/PKG pathway. Moreover, we also discuss the possibility to target the cell death program parthanatos and the kinase LRRK2 in order to develop new putative neuroprotective agents for PD acting on dopaminergic nigral neurons as well as on other basal ganglia structures.

Keywords: synaptic plasticity, dopamine receptors, NMDA receptors, LRRK2, Parthanatos

The main anatomical feature of Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), resulting in the loss of endogenous dopamine (DA) in the striatum. The DA precursor l-dopa and other antiparkinsonian medications partially alleviate striatal DA deficiency. However, after years of treatment, patients become less responsive to l-dopa as the disease progresses and experience dyskinesias.1 In addition to dopaminergic degeneration, PD also results in the loss of nondopaminergic neurons throughout the nervous system.2 For this reason preclinical and clinical neuroprotective studies have been focused on protecting either dopaminergic neurons projecting to the striatum or nondopaminergic neurons critically involved in the pathophysiology of the disease.3

Maintenance of the correct functional assembly of synaptic striatal circuits and preservation of the fine striatal spine morphology of medium spiny neurons (MSNs) have been considered a secondary target in neuroprotection studies. The maintenance of this physiological equilibrium is a direct consequence of the restorative dopaminergic strategies. It has been assumed that striatal MSNs were free of pathology until the late phase of the disease, when they show progressive loss of dendritic spines.4 Striatal spine morphology and function are critically important because the “head” of striatal spines receives excitatory glutamatergic projections from the cerebral cortex, whereas dopaminergic projections from the SNc contact on the “neck” of the spines. In addition, glutamatergic projections from specific thalamic nuclei terminate on the dendritic shafts. The size of the dendritic trees of MSNs is significantly reduced in the caudate nucleus of brains of PD cases, and their complexity is changed in both the caudate nucleus and the putamen. Considering that dendritic spines integrate glutamatergic excitatory inputs and dopaminergic signals, reduction in both the density of spines and total dendritic length is likely to have a dramatic impact on the ability of these neurons to properly function and may partly explain the symptoms of the disorder.4,5 One of the reasons for this corticostriatal dysfunction might be represented by the Lewy body pathology appearing in the pyramidal neurons of the deep cortical layers (V–VI), where the cell bodies of the corticostriatal projections are located.6 Interestingly, a multiphoton imaging approach has revealed that after striatal denervation, striatopallidal MSNs are mainly involved in this process of loss of spines and glutamatergic synapses via a mechanism requiring dysregulation of Cav1.3 L-type Ca2+ channels at the level of the spines.7

Three-dimensional electron microscopy of tissue from 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-treated monkeys shows that striatal spines contacted by cortical terminals display an increased volume of their spine apparatus, suggesting increased protein synthesis at corticostriatal synapses. Thalamostriatal and corticostriatal afferents target different types of striatal spines, and these systems undergo partly different ultrastructural changes. Nevertheless, in both systems, ultrastructural changes are indicative of increased strength of glutamatergic striatal transmission in this model of PD.8

New ultrastructural findings also suggest that astrocytes are integral functional elements of tripartite glutamatergic synaptic complexes in the cerebral cortex and the striatum. In the striatum of parkinsonian animals there is significant expansion of the astrocytic coverage of tripartite synapses, suggesting ultrastructural compensatory changes that affect both neuronal and glial elements. These findings suggest that new neuroprotective strategies have to take into account the concept of glial–neuronal communication in the striatum, where astrocytes respond to changes in neuronal activity regulating extracellular transmitter levels and excitatory transmission.9

A2A Adenosine/D2 Dopamine Receptors: From Synaptic Effects to Neuroprotection

Adenosine receptors are G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) that mediate the physiological functions of adenosine. In the central nervous system adenosine A2A receptors (A2ARs) are selectively expressed in the striatum, where they are mainly located postsynaptically in D2 DA receptor–expressing striatopallidal MSNs.10,11 In striatopallidal neurons they form functional oligomeric complexes with other GPCRs including D2 receptors. Blockade of A2A receptors with specific antagonists facilitates striatal D2 receptor function. Thus, A2AR antagonists can be considered prodopaminergic agents and could potentially reduce the effects associated with DA depletion in PD. This class of compounds has recently attracted considerable attention for PD pharmacotherapy for counteracting motor dysfunction. Moreover, A2AR antagonists are also neuroprotective in animal models of PD.12–14 In PD patients with l-dopa-induced dyskinesia, there is increased striatal A2A receptor availability, suggesting altered adenosine transmission in dyskinesia and providing an additional rationale for testing A2A receptor antagonists in this motor complication.15,16

Epidemiological and preclinical data suggest that caffeine may confer neuroprotection against the underlying dopaminergic neuron degeneration and may influence the onset and progression of PD. It has been demonstrated that among the various pharmacological effects attributed to caffeine, this agent exerts A2A receptor antagonistic properties. Thus, it is possible that caffeine and its derivatives via the modulation of A2A receptors might reduce PD symptoms and possibly exert neuroprotective effects.17

Molecular and electrophysiological data suggest a direct interaction between A2A receptors and the receptor tyrosine kinase fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR).18 Concomitant activation of these 2 receptors, but not individual activation of either alone, causes robust activation of the MAPK/ERK pathway, differentiation and neurite extension of PC12 cells, and spine morphogenesis in primary neuronal cultures. Interestingly, a novel interaction between A2A and FGFR receptors also controls corticostriatal plasticity.18 The demonstration of synergy between the A2A and FGFR receptors might have important clinical implications considering the localization of A2A receptors in striatopallidal neurons, where they influence the actions of D2 receptors. Accordingly, the neuroprotective effects of basic FGF in focal brain ischemia have been demonstrated.19 Thus, the discovery of cross talk between the A2A and the FGFR opens new possibilities for therapeutic interventions directly targeting striatal circuitry dynamics.

A2A and D2 receptors converge in the control of corticostriatal glutamatergic transmission by exerting an opposite function.20 The possible molecular mechanisms underlying this interaction and the neuronal subtypes implicated in this negative modulation of glutamate release have recently been investigated.21 This study suggested that endocannabinoid and cholinergic interneurons take part in this modulatory function (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Striatal D2/A2A interaction on cholinergic interneurons modulates both D1- and D2-receptor-expressing medium spiny neuron (MSN) activity. In the nucleus striatum activation of both dopamine D2 and adenosine A2A receptors decreases the activation of cholinergic interneurons and the release of acetylcholine. The subsequent lowering of the M1 muscarinic receptor tone favors the disinhibition of Cav1.3 Ca2+ channels, the increase in intracellular calcium concentration, and finally the production and release of endocannabinoids (ECBs). ECBs travel across the synapse and activate presynaptic CB1 receptors, causing reduced glutamate release, thus modulating excitatory synaptic transmission onto both (left) D1- and (right) D2-receptor-expressing medium spiny neurons (Ach, acetylcholine; DA, dopamine; Glu, glutamate; GluRs, glutamate receptors).

Recently the effect of subchronic blockade of A2A receptors on striatal neuron physiology and morphology has been addressed in a murine model of PD.22 The A2A receptor antagonist SCH58261, systemically administered to DA-depleted mice for 5 days, significantly attenuated alterations in synaptic currents, spine morphology, and dendritic excitability of MSNs of the indirect pathway caused by DA depletion. However, this treatment failed to prevent the spine loss observed after denervation in this subtype of MSNs. This study suggests that subchronic A2A receptor antagonism does not fully prevent ultrastructural striatal spine alterations, but it improves striatal function by attenuating synaptic adaptations of MSNs to DA depletion.22

The interaction between A2A receptors and dysfunctional mitochondrial activity in PD represents another interesting target for the identification of new neuroprotective strategies for PD. Complex I is the first protein component of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, and it plays a crucial role in ATP production and mitochondrial function. Mitochondrial dysfunction has been identified in a number of neurodegenerative diseases, in particular in PD. Mitochondrial toxins such as rote-none and MPTP are capable of producing relatively selective neuronal cell death and have been used to produce models of PD.23,24 The possible neuroprotective action of A2A receptor antagonists against mitochondrial dysfunction has been investigated in striatal slices exposed to the acute application of rotenone, a pesticide acting as a selective inhibitor of mitochondrial complex I activity.25 In striatal slices rotenone causes irreversible loss of corticostriatal field potential amplitude as well as membrane depolarization. A2A receptor antagonists reduced the irreversible electrophysiological effects induced by this mitochondrial toxin, suggesting that the treatment with A2A receptor antagonists might represent a possible neuroprotective strategy in basal ganglia disorders involving a deficit of mitochondrial complex I activity such as PD.25

NMDA Receptor Subunit Composition and Its Role in Physiological and Aberrant Striatal Synaptic Plasticity as a Possible Target for Neuroprotection

NMDA receptors have been implicated in the induction of the major forms of synaptic plasticity such as long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD). These forms of plasticity are believed to underlie complex tasks including learning and memory (Kandel, 2001). NMDA receptors also play a critical role in striatal LTP, which is considered a synaptic and cellular model for motor learning.26–29 Moreover, NMDA-mediated aberrant striatal synaptic plasticity has been implicated in several experimental models of neurological diseases including PD,30,31 l-dopa-induced dyskinesia,1,32,33 Huntington’s disease,34,35 epilepsy,36,37 ischemia,38–40 and Down syndrome.41 Alterations of the NMDA receptor channel complex have been identified as an underlying molecular mechanism in neurological disorders ranging from acute stroke to chronic neurodegeneration. Excessive glutamate levels have been detected in pathological conditions including PD, resulting in abnormal stimulation of NMDA receptors, which in turn trigger a cascade of excitation-mediated neuronal damage and apoptosis via Ca2+-dependent mechanisms. Thus, NMDA receptors have been identified as potential targets for neuroprotective strategies. Although competitive NMDA receptor antagonists have been found to be neuroprotective in animal models, these drugs failed in clinical trials because of serious adverse effects such as cognitive alterations and sedation.42

Recently, the concept that the pathways’ downstream NMDA receptor activation could represent a key variable element among neurological disorders has been suggested.43 In particular, variations in NMDA receptor subunit composition could be important in neurodegenerative processes. The possibility to target specific NMDA subunits rather than to use competitive NMDA antagonists has been explored as a symptomatic as well as neuroprotective strategy. The NMDA receptor complex has been shown to be altered in experimental models of parkinsonism and in PD in humans. Changes of specific NMDA receptor subunits as well as postsynaptic associated signaling complex including kinases and scaffolding proteins occur in experimental parkinsonism and PD.43 These findings may allow the identification of specific molecular targets whose pharmacological or genetic manipulation might lead to innovative therapies for PD. The NR1 subunit and PSD-95 protein levels are selectively reduced in the postsynaptic density (PSD) of fully DA-denervated striata. These effects are accompanied by an increase in striatal levels of αCaMKII autophosphorylation coupled with higher recruitment of activated CaM-KII to the regulatory NMDA receptor NR2A-NR2B subunits. The effect of DA denervation was mimicked by the blockade of D1-like but not D2-like receptors. Administration of CaMKII inhibitors reversed both the alterations in corticostriatal synaptic plasticity and the deficits in spontaneous motor behavior found in this model of PD. A similar beneficial effect was obtained following subacute l-dopa, suggesting that normalization of CaMKII activity may represent a critical mechanism of the therapeutic effect of l-dopa in PD.44

Full DA denervation in experimental animal models mimics advanced PD, causing altered plasticity,27 loss of striatal dendritic spines,7,45 and changes of glutamatergic signaling.44,46 After complete dopaminergic denervation, there is loss of both LTP and LTD at striatal glutamatergic synapses, indicating that the integrity of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathway is of crucial importance for the induction of striatal long-lasting synaptic changes.28,31,47–50 However, it is important to stress that early clinical symptoms of PD are only detected when >70% of DA neurons are lost.51 For this reason, a reliable model of early PD characterized by lowered DA close to this threshold is of key importance in understanding the molecular and synaptic changes underlying this early stage and finding new therapeutic strategies to treat early phases of the disease. Following this line of research, it has been recently shown that distinct levels of DA denervation differentially alter the induction and maintenance of 2 distinct and opposite forms of corticostriatal synaptic plasticity.52 Partial DA denervation does not affect corticostriatal LTD. However, this form of synaptic plasticity is blocked following full denervation, indicating that a low, although critical, level of endogenous DA is necessary for LTD. This observation leads to the hypothesis that LTD is implicated in the motor abnormalities seen in the late phase of PD but not in the early stage of the disease. Conversely, partial DA denervation affects the maintenance of LTP, confirming the critical role of this form of synaptic plasticity in early motor parkinsonian symptoms.52

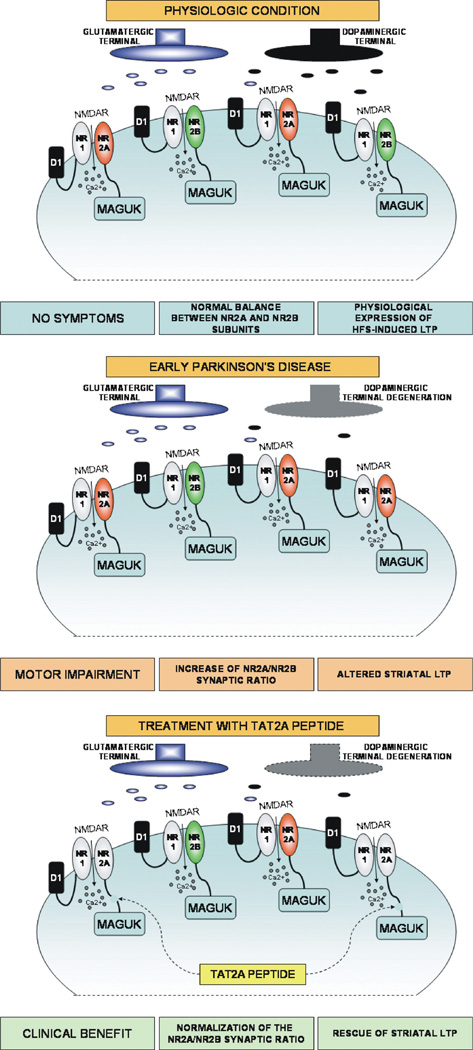

Previous reports have clearly addressed the capability of cell-permeable TAT peptides fused to the C-terminal domain of NMDA receptor subunits to reach and to disrupt NMDA/MAGUK association in both in vitro and in vivo studies.53,54 Exposure to a TAT peptide fused to the last 9 C-terminal amino acids of NR2A (TAT2A)53 directly targets PSD-95–NR2A subunit interaction and can reverse motor and synaptic plasticity abnormalities in early parkinsonism. Systemic administration of TAT2A peptide normalizes both LTP and motor behavior in partially lesioned rats, which could be considered a model of “early” PD (Fig. 2). The possibility of targeting intracellular pathways and protein complexes using cell-permeable peptide conjugates represents a possible new and potent approach to blocking intracellular pathways implicated in neurodegenerative processes with reduction of the side effects related to the direct antagonism of the NMDA receptor channel complex.55

FIG. 2.

The importance of physiologic NMDA receptor subunit balance for motor activity and striatal synaptic plasticity. In physiologic condition (upper), a correct balance between NR2A and NR2B subunits of the NMDA receptor is associated with normal motor activity and with the ability of excitatory striatal synapses to induce long-term potentiation (LTP) after high-frequency stimulation (HFS) of corticostriatal fibers. In experimental models of early Parkinson’s disease (middle), development of motor impairment is associated with an increase of the synaptic NR2A/NR2B subunit ratio and with altered expression of synaptic LTP after HFS. The treatment with TAT2A peptides (lower) targeting MAGUK–NR2A subunit interaction is able to ameliorate the clinical symptoms of the experimental disease, to normalize the synaptic NR2A/NR2B synaptic ratio, and to restore thesynapses’ ability to express LTP after HFS (MAGUK, membrane-associated guanylate kinases).

The NO–sGC–cGMP Signaling Pathway in Striatal Plasticity and Neuroprotection

Nitric oxide (NO) is a diffusible gaseous molecular agent of critical importance in both physiological and pathological functioning of brain activities, acting either as a retrograde transmitter or as a mediator of toxicity. In addition to its role in neurotransmission of central and peripheral neurons, NO mediates blood vessel relaxation by the endothelium and immune activity of macrophages. NO is produced from 3 NO synthase (NOS) isoforms: Neuronal NOS (nNOS), endothelial NOS, and inducible NOS (iNOS). Excessive production of NO following a pathologic insult can lead to neurotoxicity. NO plays a role in mediating neurotoxicity associated with a variety of neurologic disorders, including stroke, PD, and HIV dementia.56

In the striatum NO is produced by interneurons57 and it plays an important role in the regulation of corticostriatal synaptic plasticity58 and motor activity.59 Concomitant activation of NMDA and D1-like DA receptors in the striatum triggers NO synthesis.60 NO diffuses into the dendrites of MSNs, which have soluble guanylyl cyclases (sGC) activated by NO production. In turn, activation of sGC stimulates the synthesis of the second messenger cGMP. In the intact striatum, transient changes of intracellular cGMP modulate neuronal excitability as well as short- and long-term glutamatergic corticostriatal transmission. Striatal DA depletion alters NO–sGC–cGMP signaling and contributes to the pathophysiological changes observed in basal ganglia circuits in PD. The NO–sGC–cGMP signaling pathways play an important role in basal ganglia dysfunction and the motor symptoms associated with PD and in l-dopa-induced dyskinesias, raising the possibility that this system might represent a possible target for neuroprotection.

Behavioral studies have suggested a general facilitatory role of the striatal NO–sGC–cGMP system in locomotor activity59; however, the scenario is more complex in PD and in PD animal models.60 The basal ganglia of PD patients61,62 as well as the striatum of DA-denervated animals show altered NO signaling.63 Experimental data concerning striatal cGMP levels in PD models are not univocal, probably because of different measuring techniques and regions selected for analysis. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that phosphodiesterase (PDE) mRNA, protein, and activity are elevated, suggesting that the metabolism of cGMP is increased in DA-depleted rats.63,64 There is a critical need for functional characterization of striatal activity of the various steps involved in this biochemical pathway such as NOS, sGC, cGMP, PKG, and distinct classes of PDEs. This characterization should be done in the same experimental models and at various times after DA denervation as well as following l-dopa treatment. In line with this idea, the role of the NO–sGC–cGMP system has recently been characterized in the induction of corticostriatal LTD in fully DA-denervated animals65 (Fig. 3). The effect of cGMP-related signaling has also been recently investigated in transgenic animals expressing mutant α-synuclein, in particular in mice transgenic for mutant A53T-α-synuclein. These mice showed age-dependent biochemical alterations of the DA system and behavioral impairments.66

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of phosphodiesterases rescues striatal long-term depression (LTD) in experimental models of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Nitric oxide (NO) released by nitric oxide synthase (NOS)–positive interneurons activates soluble guanylyl cyclases (sGC), which stimulates the synthesis of the second-messenger cGMP, which, in turn, facilitates striatal LTD induction. Experimental models of PD are associated with the loss of LTD at glutamatergic striatal synapses onto spiny neurons. Treatment with inhibitors of phosphodiesterases (PDEs) is able to restore LTD induction at striatal synapses and to ameliorate motor performances (cGMP, cyclic GMP; DA, dopamine; DARPP32, dopamine and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein 32 kDa; Glu, glutamate; MSN, medium spiny neuron; PDE, phosphodiesterases; PDE-inh, inhibitors of phosphodiesterases; PKG, protein kinase G).

NO leads to cell death and pathological plasticity through several pathways in addition to the activation of the c-GMP-PKG-related intracellular signal. NO participates in cell death signaling through cell stress and activation of inducible or neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS), leading to S-nitrosylation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) by NO. S-nitrosylation of GAPDH abolishes catalytic activity and confers on GAPDH the ability to bind to Siah1 (hereafter designated Siah), an E3-ubiquitin-ligase whose nuclear localization signal mediates nuclear translocation of the GAPDH/Siah complex. Interestingly, deprenyl and TCH346 at subnanomolar concentrations prevent S-nitrosylation of GAPDH, reduce GAPDH/Siah binding and block the nuclear translocation of GAPDH. These actions also occurred in an experimental model of PD at very low doses.67

The Role of Parthanatos in Models of Parkinson’s Disease

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase–1 (PARP-1), an important nuclear enzyme, is potently activated by DNA damage and facilitates DNA repair.68,69 Severe DNA damage, which is induced either by a variety of environmental stimuli such as the DNA-alkylating agent N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidin, free radicals, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, peroxynitrite, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), and ionizing radiation or by activation of glutamate receptors, leads to overactivation of PARP-1.69,70 Excessive activation of PARP-1 causes an intrinsic cell death program that is unique compared to apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy and has been designated parthanatos.69,71 Parthanatos is widely involved in various diseases,72 including PD, stroke, trauma, ischemia reperfusion injury, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Huntington’s disease, heart attack, and diabetes.

PAR polymer is produced by PARP-1 activation using nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) as the substrate and functions as a signal molecule to induce cell death.69,73–75 PAR polymer is potentially elevated in dopaminergic neurons and caused cell death in substantia nigra pars compacta after the treatment of mice with the neurotoxin MPTP.76 PARP-1 knockout robustly protects dopaminergic neurons from MPTP neurotoxicity.76 Moreover, pharmacological inhibition of PARP-1 also reduced α-synuclein- and 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium MPP+-induced cytotoxicity in PD in vitro models.77 These studies indicate that parthanatos plays a pivotal role in dopaminergic neuron loss in different models of PD.

Parthanatos is mainly mediated by mitochondrial oxidoreductase apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) release from the mitochondria and translocation to nucleus,78 as AIF knockdown or neutralizing anti-AIF antibodies prevent AIF translocation to the nucleus and inhibit alkylating DNA damage-mediated cell death in a variety of experimental paradigms.69,73,79,80 Although the mechanisms of dopaminergic neuron loss in the MPTP animal models of PD are not yet fully understood, AIF has been implicated in mediating MPP+ toxicity in dopaminergic cells, which was not inhibited by caspase inhibitors but was prevented by knockdown of AIF.81 Recent studies have advanced our understanding of the cross talk between mitochondria and the nucleus in parthanatos. On PARP-1 activation, PAR is formed and signals to mitochondria, where PAR interacts with AIF, disrupts AIF-mitochondria binding, and triggers AIF release from mitochondria and translocation to the nucleus, eventually causing cell death.71 However, an AIF mutant, which has no PAR-binding property, cannot be released from mitochondria and fails to translocate to the nucleus to mediate cell death after PARP-1 activation.71 In addition, a previously undescribed NMDA-induced cell survival molecule Iduna, encoded by Rnf146,82 was found to be a PAR-dependent ubiquitin E3 ligase. Iduna protects against NMDA excitotoxicity and stroke through preventing AIF nuclear translocation.82,83 Thus, Iduna functions as an endogenous inhibitor in parthanatos. Interestingly, it was found that PAR binding is required for Iduna’s E3 ligase activity and neuroprotective effects. Therefore, targeting PAR signaling or PAR-AIF interaction could be a novel potential strategy to prevent dopaminergic neuron loss in PD.

LRRK2 Inhibition as a Potential Therapeutic for PD

Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) is a large multidomain protein comprising numerous functional domains including an ankyrin repeat region, a leucine-rich repeat domain, a Roc GTPase domain, a C-terminal of Ras domain, a kinase domain, and a WD40 domain.84–86 Studies have demonstrated that the LRRK2 protein is widely expressed in several organs as well as in the mammalian central nervous system, including the neurons of the striatum, cortex, substantia nigra, hippocampus, and cerebellum, where it associates with membranes and vesicular structures.84–87 Despite the identification of LRRK2’s localization, distribution, and functional domains, the main physiological role of this protein and its physiological substrates remain largely unknown.85,88,89

Currently, more than 40 LRRK2 mutations have been identified, most of which are a result of single amino acid substitutions.89 The most prevalent LRRK2 mutation is an amino acid substitution whereby a highly conserved glycine residue (Gly2019), in the kinase domain of LRRK2, is replaced by a serine residue.85,86,89,90 Several studies have demonstrated that this autosomal dominant mutation is associated with increased LRRK2 kinase activity, and it has also been linked to the majority of sporadic and familial cases of PD.84,86

In an effort to compensate for the robust increase in kinase activity from the G2019S mutation in the LRRK2 gene, numerous studies have focused on inhibiting LRRK2’s increased kinase activity by means of small molecules.87–89,91,92 Myriad excellent studies have demonstrated that the use of pharmacological inhibitors such as the idoline compound GW5074 or the Raf kinase inhibitor sorafenib could not only inhibit LRRK2’s autophosphorylation as well as its ability to phosphorylate several artificial substrates, but also significantly decrease neurotoxicity in both in vitro and in vivo model systems of PD88,93 (Table 1). Results such as those published by Lee and colleagues are highly promising, as they provide support that the inhibition of LRRK2 by small molecules may indeed present an avenue for the development of effective therapeutics for the treatment of PD.

TABLE 1.

Summary of confirmed LRRK2 kinase inhibitors

| Compound name | Model system used | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Staurosporin | In vitro kinase assay | 86 |

| 95 | ||

| GF 109203X | In vitro kinase assay | 86 |

| Ro 31–8220 | In vitro kinase assay | 86 |

| 5-iodotubercidin | In vitro kinase assay | 86 |

| GW5074 | In vitro kinase assay | 86 |

| Primary cortical cultures | 91 | |

| In vivo | ||

| Indirubin-3′-monooxime | In vitro kinase assay | 86 |

| Primary cortical cultures | ||

| In vivo | ||

| SP 600125 | In vitro kinase assay | 86 |

| Damnacanthal | In vitro kinase assay | 86 |

| Raf inhibitor IV | In vitro kinase assay | 86 |

| ZM 336372 | In vitro kinase assay; | 86 |

| Primary cortical cultures | ||

| Sorafenib | In vitro kinase assay; | 86 |

| Primary cortical cultures | 91 | |

| Raf-1 kinase inhibitor 1 | In vitro kinase assay | 95 |

| Gö6976 | In vitro kinase assay | 95 |

| K-252a | In vitro kinase assay | 95 |

| K-252b | In vitro kinase assay | 95 |

| H-1152 | In vitro | 89 |

| 87 | ||

| Sunitinib | In vitro | 89 |

| 87 | ||

| LRRK2-IN-1 | In vitro kinase assay | 88 |

| In vitro | ||

| In vivo | ||

| Y-27632 | In vitro kinase assay | 87 |

| CZC-25146 | In vitro kinase assay | 90 |

| CZC-54252 | Primary neuronal cultures | |

| Hydroxyfasudil | In vitro kinase assay | 87 |

Table represents a summary of LRRK2 kinase inhibitors which have been shown to robustly inhibit the catalytic activity of LRRK2 in a variety of model systems.

However, caution has to be taken when considering the pharmacological inhibition of LRRK2 to treat PD. One main concern regarding the use of kinase inhibitors is the potential of off-target effects, as many kinase inhibitors not only inhibit LRRK2’s kinase activity but also inhibit multiple other kinases such as Rho kinases.89 Although numerous published LRRK2 inhibitors successfully inhibited LRRK2’s kinase activity in vitro and in vivo, the specificity and selectivity of several of these compounds for LRRK2 remains to be determined. In a recent study by Deng et al, the LRRK2 inhibitor LRRK2-IN-1 was found to selectively inhibit LRRK2 in vitro and in vivo.90 Although the data presented by Deng et al are compelling, it remains unknown if the LRRK2 inhibitor LRRK2-IN-1 can also effectively and selectively inhibit the catalytic activity of LRRK2 in a mouse model or other in vivo model systems of PD. Moreover, the degree of LRRK2 inhibition required to have therapeutic potential has to be evaluated, as too little or too much inhibition of LRRK2 could elicit undesired side effects. In a recent study by Liu et al,94 the authors demonstrated that LRRK2 deficiency results in the development of severe colitis in LRRK2-knockout mice.94 In addition, in genetically engineered mice deficient in LRRK2, there were inclusions and potential injury in the proximal tubules of the kidney.95,96 These results further support the notion that the pharmacological interference with LRRK2’s kinase activity as a means to treat PD is a very delicate fine-tuning act and that more research aimed at even better understanding the physiological role of LRRK2 is required.

Conclusions

Clinical trials failed in demonstrating clinical efficacy of drugs that in preclinical studies showed promising neuroprotective profiles in experimental models of PD. Nevertheless, neuroprotection in PD remains an important goal of current preclinical and clinical research. In fact, a successful neuroprotective treatment could dramatically ameliorate the quality of life of PD patients and improve the clinical efficacy of current symptomatic therapies. Present difficulties in achieving this goal include limited information on the mechanisms of neurodegeneration as well as problems in the methodology used to study disease progression. The failures of several potential neuroprotective therapies tested in the clinical studies could also be explained by the limitations of animal models on which the rationale to use a specific agent was tested. At present, animal models generated on the ground of both genetic and toxicological information of PD offer a wide repertoire of possibilities for the screening of putative neuroprotective drugs. Nevertheless, none of these models per se recapitulates the complex picture of the disease and its progression. Moreover, the identification of several genes implicated in PD has further supported the heterogeneity of this disorder, suggesting the idea that the neurodegeneration does not only involve the dopaminergic system but also affects other anatomical sites. Among these sites, the striatum is a major candidate. In fact, the correct functioning of the dopaminergic system within the basal ganglia requires an intact target area represented by the striatum and its anatomical, synaptic, and molecular mechanisms. Thus, future neuroprotective strategies, in addition to the classical nigral “focus” should also consider the striatum as a novel target for neuroprotection.

Acknowledgments

Funding agencies: This work was supported by grants from European Community contract number 222918 (REPLACES) FP7—Thematic priority HEALTH (PC), and Progetto Giovani Ricercatori Ministero Sanita 2008 (BP).

Footnotes

Relevant conflicts of interest/financial disclosures: Nothing to report.

Full financial disclosures and author roles may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Calabresi P, Filippo MD, Ghiglieri V, Tambasco N, Picconi B. Levodopa-induced dyskinesias in patients with Parkinson’s disease: filling the bench-to-bedside gap. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:1106–1117. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lang AE, Obeso JA. Challenges in Parkinson’s disease: restoration of the nigrostriatal dopamine system is not enough. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:309–316. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00740-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olanow CW, Kieburtz K, Schapira AH. Why have we failed to achieve neuroprotection in Parkinson’s disease? Ann Neurol. 2008;64(Suppl 2):S101–S110. doi: 10.1002/ana.21461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stephens B, Mueller AJ, Shering AF, et al. Evidence of a break-down of corticostriatal connections in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience. 2005;132:741–754. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deutch AY. Striatal plasticity in parkinsonism: dystrophic changes in medium spiny neurons and progression in Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2006:67–70. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-45295-0_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braak H, Del Tredici K. Invited Article: Nervous system pathology in sporadic Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;70:1916–1925. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000312279.49272.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day M, Wang Z, Ding J, et al. Selective elimination of glutamatergic synapses on striatopallidal neurons in Parkinson disease models. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:251–259. doi: 10.1038/nn1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villalba RM, Smith Y. Differential structural plasticity of corticostriatal and thalamostriatal axo-spinous synapses in MPTP-treated Parkinsonian monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 2011;519:989–1005. doi: 10.1002/cne.22563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villalba RM, Smith Y. Neuroglial plasticity at striatal glutamatergic synapses in Parkinson’s disease. Front Syst Neurosci. 2011;5:68. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferre S, Fredholm BB, Morelli M, Popoli P, Fuxe K. Adenosine-do-pamine receptor-receptor interactions as an integrative mechanism in the basal ganglia. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:482–487. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schiffmann SN, Fisone G, Moresco R, Cunha RA, Ferre S. Adenosine A2A receptors and basal ganglia physiology. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;83:277–292. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morelli M, Di Paolo T, Wardas J, Calon F, Xiao D, Schwarzschild MA. Role of adenosine A2A receptors in parkinsonian motor impairment and l-DOPA-induced motor complications. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;83:293–309. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vallano A, Fernandez-Duenas V, Pedros C, Arnau JM, Ciruela F. An update on adenosine A2A receptors as drug target in Parkinson’s disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2011;10:659–669. doi: 10.2174/187152711797247803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu K, Bastia E, Schwarzschild M. Therapeutic potential of adenosine A(2A) receptor antagonists in Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;105:267–310. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mishina M, Ishiwata K, Naganawa M, et al. Adenosine A(2A) receptors measured with [C]TMSX PET in the striata of Parkinson’s disease patients. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramlackhansingh AF, Bose SK, Ahmed I, Turkheimer FE, Pavese N, Brooks DJ. Adenosine 2A receptor availability in dyskinetic and nondyskinetic patients with Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2011;76:1811–1816. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821ccce4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prediger RD. Effects of caffeine in Parkinson’s disease: from neuroprotection to the management of motor and non-motor symptoms. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 1):S205–S220. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flajolet M, Wang Z, Futter M, et al. FGF acts as a co-transmitter through adenosine A(2A) receptor to regulate synaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1402–1409. doi: 10.1038/nn.2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song BW, Vinters HV, Wu D, Pardridge WM. Enhanced neuroprotective effects of basic fibroblast growth factor in regional brain ischemia after conjugation to a blood-brain barrier delivery vector. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;301:605–610. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.2.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tozzi A, Tscherter A, Belcastro V, et al. Interaction of A2A adenosine and D2 dopamine receptors modulates corticostriatal glutamatergic transmission. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:783–789. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tozzi A, de Iure A, Di Filippo M, et al. The Distinct Role of Medium Spiny Neurons and Cholinergic Interneurons in the D2/A2A Receptor Interaction in the Striatum: Implications for Parkinson’s Disease. J Neurosci. 2011;31:1850–1862. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4082-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peterson JD, Goldberg JA, Surmeier DJ. Adenosine A2a receptor antagonists attenuate striatal adaptations following dopamine depletion. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;45:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gubellini P, Picconi B, Di Filippo M, Calabresi P. Downstream mechanisms triggered by mitochondrial dysfunction in the basal ganglia: From experimental models to neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:151–161. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schapira AH. Complex I: inhibitors, inhibition and neurodegeneration. Exp Neurol. 2010;224:331–335. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belcastro V, Tozzi A, Tantucci M, et al. A2A adenosine receptor antagonists protect the striatum against rotenone-induced neurotoxicity. Exp Neurol. 2009;217:231–234. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calabresi P, Di Filippo M. Neuroscience: brain’s traffic lights. Nature. 2010;466:449. doi: 10.1038/466449a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calabresi P, Picconi B, Tozzi A, Di Filippo M. Dopamine-mediated regulation of corticostriatal synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calabresi P, Pisani A, Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. Long-term Potentiation in the striatum is unmasked by removing the voltage-dependent magnesium block of NMDA receptor channels. Eur J Neurosci. 1992;4:929–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1992.tb00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lovinger DM. Neurotransmitter roles in synaptic modulation, plasticity and learning in the dorsal striatum. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:951–961. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bagetta V, Ghiglieri V, Sgobio C, Calabresi P, Picconi B. Synaptic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38:493–497. doi: 10.1042/BST0380493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pisani A, Centonze D, Bernardi G, Calabresi P. Striatal synaptic plasticity: implications for motor learning and Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2005;20:395–402. doi: 10.1002/mds.20394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calabresi P, Giacomini P, Centonze D, Bernardi G. Levodopa-induced dyskinesia: a pathological form of striatal synaptic plasticity? Ann Neurol. 2000;47(4 Suppl 1):S60–S68. discussion S68–S69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Picconi B, Centonze D, Hakansson K, et al. Loss of bidirectional striatal synaptic plasticity in L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:501–506. doi: 10.1038/nn1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghiglieri V, Sgobio C, Costa C, Picconi B, Calabresi P. Striatum-hippocampus balance: from physiological behavior to interneuronal pathology. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;94:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Picconi B, Passino E, Sgobio C, et al. Plastic and behavioral abnormalities in experimental Huntington’s disease: A crucial role for cholinergic interneurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghiglieri V, Picconi B, Sgobio C, et al. Epilepsy-induced abnormal striatal plasticity in Bassoon mutant mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:1979–1993. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghiglieri V, Sgobio C, Patassini S, et al. TrkB/BDNF-dependent striatal plasticity and behavior in a genetic model of epilepsy: modulation by valproic acid. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1531–1540. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calabresi P, Centonze D, Pisani A, Cupini L, Bernardi G. Synaptic plasticity in the ischaemic brain. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:622–629. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Filippo M, Tozzi A, Costa C, et al. Plasticity and repair in the post-ischemic brain. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:353–362. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Picconi B, Tortiglione A, Barone I, et al. NR2B subunit exerts a critical role in postischemic synaptic plasticity. Stroke. 2006;37:1895–1901. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000226981.57777.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Filippo M, Tozzi A, Ghiglieri V, et al. Impaired plasticity at specific subset of striatal synapses in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:666–671. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lipton SA. Pathologically activated therapeutics for neuroprotection. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:803–808. doi: 10.1038/nrn2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gardoni F, Ghiglieri V, Luca M, Calabresi P. Assemblies of glutamate receptor subunits with post-synaptic density proteins and their alterations in Parkinson’s disease. Prog Brain Res. 2010;183:169–182. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(10)83009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Picconi B, Gardoni F, Centonze D, et al. Abnormal Ca2+-calmod-ulin-dependent protein kinase II function mediates synaptic and motor deficits in experimental parkinsonism. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5283–5291. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1224-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anglade P, Mouatt-Prigent A, Agid Y, Hirsch E. Synaptic plasticity in the caudate nucleus of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neuro-degeneration. 1996;5:121–128. doi: 10.1006/neur.1996.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Betarbet R, Poisik O, Sherer TB, Greenamyre JT. Differential expression and ser897 phosphorylation of striatal N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunit NR1 in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2004;187:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bagetta V, Picconi B, Marinucci S, et al. Dopamine-dependent long-term depression is expressed in striatal spiny neurons of both direct and indirect pathways: implications for Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2011;31:12513–12522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2236-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Centonze D, Gubellini P, Picconi B, Calabresi P, Giacomini P, Bernardi G. Unilateral dopamine denervation blocks corticostriatal LTP. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:3575–3579. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.6.3575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kreitzer AC, Malenka RC. Endocannabinoid-mediated rescue of striatal LTD and motor deficits in Parkinson’s disease models. Nature. 2007;445:643–647. doi: 10.1038/nature05506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang K, Low MJ, Grandy DK, Lovinger DM. Dopamine-dependent synaptic plasticity in striatum during in vivo development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1255–1260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031374698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114:2283–2301. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paille V, Picconi B, Bagetta V, et al. Distinct levels of dopamine de-nervation differentially alter striatal synaptic plasticity and NMDA receptor subunit composition. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14182–14193. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2149-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aarts M, Liu Y, Liu L, et al. Treatment of ischemic brain damage by perturbing NMDA receptor- PSD-95 protein interactions. Science. 2002;298:846–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1072873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gardoni F, Picconi B, Ghiglieri V, et al. A critical interaction between NR2B and MAGUK in L-DOPA induced dyskinesia. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2914–2922. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5326-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gardoni F, Sgobio C, Pendolino V, Calabresi P, Di Luca M, Picconi B. Targeting NR2A–containing NMDA receptors reduces L-DOPA-induced dyskinesias. Neurobiol Aging. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.019. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Nitric oxide in neurodegeneration. Prog Brain Res. 1998;118:215–229. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kawaguchi Y, Wilson CJ, Augood SJ, Emson PC. Striatal interneurones: chemical, physiological and morphological characterization. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:527–535. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)98374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Calabresi P, Gubellini P, Centonze D, et al. A critical role of the nitric oxide/cGMP pathway in corticostriatal long-term depression. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2489–2499. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-07-02489.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Del Bel EA, Guimaraes FS, Bermudez-Echeverry M, et al. Role of nitric oxide on motor behavior. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2005;25:371–392. doi: 10.1007/s10571-005-3065-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.West AR, Tseng KY. Nitric oxide-soluble guanylyl cyclase-cyclic GMP signaling in the striatum: new targets for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease? Front Syst Neurosci. 2011;5:55. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bockelmann R, Wolf G, Ransmayr G, Riederer P. NADPH-diaphorase/nitric oxide synthase containing neurons in normal and Parkinson’s disease putamen. J Neural Transm Park Dis Dement Sect. 1994;7:115–121. doi: 10.1007/BF02260966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eve DJ, Nisbet AP, Kingsbury AE, et al. Basal ganglia neuronal nitric oxide synthase mRNA expression in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;63:62–71. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sancesario G, Giorgi M, D’Angelo V, et al. Down-regulation of nitrergic transmission in the rat striatum after chronic nigrostriatal deafferentation. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:989–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Giorgi M, D’Angelo V, Esposito Z, et al. Lowered cAMP and cGMP signalling in the brain during levodopa-induced dyskinesias in hemiparkinsonian rats: new aspects in the pathogenetic mechanisms. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:941–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Picconi B, Bagetta V, Ghiglieri V, et al. Inhibition of phosphodiesterases rescues striatal long-term depression and reduces levodopa-induced dyskinesia. Brain. 2011;134:375–387. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tozzi A, Costa C, Siliquini S, et al. Mechanisms underlying altered striatal synaptic plasticity in old A53T–alpha synuclein overexpressing mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:1792–1799. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hara MR, Thomas B, Cascio MB, et al. Neuroprotection by pharmacologic blockade of the GAPDH death cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3887–3889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511321103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.David KK, Andrabi SA, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Parthanatos, a messenger of death. Front Biosci. 2009;14:1116–1128. doi: 10.2741/3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Y, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Poly(ADP-ribose) signals to mitochondrial AIF: a key event in parthanatos. Exp Neurol. 2009;218:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Deadly conversations: nuclear-mitochondrial cross-talk. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2004;36:287–294. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBB.0000041755.22613.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang Y, Kim NS, Haince JF, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) binding to apoptosis-inducing factor is critical for PAR polymerase-1-dependent cell death (parthanatos) Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra20. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pacher P, Szabo C. Role of the peroxynitrite-poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase pathway in human disease. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:2–13. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Andrabi SA, Kim NS, Yu SW, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) polymer is a death signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18308–18313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606526103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lautier D, Lagueux J, Thibodeau J, Menard L, Poirier GG. Molecular and biochemical features of poly (ADP-ribose) metabolism. Mol Cell Biochem. 1993;122:171–193. doi: 10.1007/BF01076101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smulson ME, Simbulan-Rosenthal CM, Boulares AH, et al. Roles of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and PARP in apoptosis, DNA repair, genomic stability and functions of p53 and E2F-1. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2000;40:183–215. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(99)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mandir AS, Przedborski S, Jackson-Lewis V, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation mediates 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced parkinsonism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5774–5779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Outeiro TF, Grammatopoulos TN, Altmann S, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of PARP-1 reduces alpha-synuclein- and MPP+-induced cytotoxicity in Parkinson’s disease in vitro models. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yu SW, Wang H, Poitras MF, et al. Mediation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-dependent cell death by apoptosis-inducing factor. Science. 2002;297:259–263. doi: 10.1126/science.1072221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cheung EC, Melanson-Drapeau L, Cregan SP, et al. Apoptosis-inducing factor is a key factor in neuronal cell death propagated by BAX-dependent and BAX-independent mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1324–1334. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4261-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Culmsee C, Zhu C, Landshamer S, et al. Apoptosis-inducing factor triggered by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and Bid mediates neuronal cell death after oxygen-glucose deprivation and focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10262–10272. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2818-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chu CT, Zhu JH, Cao G, Signore A, Wang S, Chen J. Apoptosis inducing factor mediates caspase-independent 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium toxicity in dopaminergic cells. J Neurochem. 2005;94:1685–1695. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Andrabi SA, Kang HC, Haince JF, et al. Iduna protects the brain from glutamate excitotoxicity and stroke by interfering with poly(-ADP-ribose) polymer-induced cell death. Nat Med. 2011;17:692–699. doi: 10.1038/nm.2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kang HC, Lee YI, Shin JH, et al. Iduna is a poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR)-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase that regulates DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14103–14108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108799108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Biskup S, Moore DJ, Celsi F, et al. Localization of LRRK2 to membranous and vesicular structures in mammalian brain. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:557–569. doi: 10.1002/ana.21019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cookson MR. The role of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) in Parkinson’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:791–797. doi: 10.1038/nrn2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mata IF, Wedemeyer WJ, Farrer MJ, Taylor JP, Gallo KA. LRRK2 in Parkinson’s disease: protein domains and functional insights. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Biskup S, West AB. Zeroing in on LRRK2-linked pathogenic mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:625–633. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee BD, Shin JH, VanKampen J, et al. Inhibitors of leucine-rich repeat kinase-2 protect against models of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Med. 2010;16:998–1000. doi: 10.1038/nm.2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nichols RJ, Dzamko N, Hutti JE, et al. Substrate specificity and inhibitors of LRRK2, a protein kinase mutated in Parkinson’s disease. Biochem J. 2009;424:47–60. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Deng X, Dzamko N, Prescott A, et al. Characterization of a selective inhibitor of the Parkinson’s disease kinase LRRK2. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:203–205. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dzamko N, Deak M, Hentati F, et al. Inhibition of LRRK2 kinase activity leads to dephosphorylation of Ser(910)/Ser(935), disruption of 14-3-3 binding and altered cytoplasmic localization. Biochem J. 2010;430:405–413. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ramsden N, Perrin J, Ren Z, et al. Chemoproteomics-based design of potent LRRK2-selective lead compounds that attenuate Parkinson’s disease-related toxicity in human neurons. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:1021–1028. doi: 10.1021/cb2002413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu Z, Hamamichi S, Lee BD, et al. Inhibitors of LRRK2 kinase attenuate neurodegeneration and Parkinson-like phenotypes in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila Parkinson’s disease models. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3933–3942. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu Z, Lee J, Krummey S, Lu W, Cai H, Lenardo MJ. The kinase LRRK2 is a regulator of the transcription factor NFAT that modulates the severity of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1063–1070. doi: 10.1038/ni.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.MC Kolly C, Persohn E, et al. LRRK2 protein levels are determined by kinase function and are crucial for kidney and lung homeostasis in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:4209–4223. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tong Y, Yamaguchi H, Giaime E, et al. Loss of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 causes impairment of protein degradation pathways, accumulation of alpha-synuclein, and apoptotic cell death in aged mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;107:9879–9884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004676107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]