Abstract

Background

This is an update of a review published in The Cochrane Library 2008, Issue 4. Celecoxib is a selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor usually prescribed for the relief of chronic pain in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Celecoxib is believed to be associated with fewer upper gastrointestinal adverse effects than conventional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Its effectiveness in acute pain was demonstrated in the earlier reviews.

Objectives

To assess analgesic efficacy and adverse effects of a single oral dose of celecoxib for moderate to severe postoperative pain.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Oxford Pain Database, and ClinicalTrials.gov. The most recent search was to 3 January 2012.

Selection criteria

We included randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) of adults prescribed any dose of oral celecoxib or placebo for acute postoperative pain.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors assessed studies for quality and extracted data. We converted summed pain relief (TOTPAR) or pain intensity difference (SPID) into dichotomous information, yielding the number of participants with at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours, and used this to calculate the relative benefit (RB) and number needed to treat to benefit (NNT) for one patient to achieve at least 50% of maximum pain relief with celecoxib who would not have done so with placebo. We used information on use of rescue medication to calculate the proportion of participants requiring rescue medication and the weighted mean of the median time to use.

Main results

Eight studies (1380 participants) met the inclusion criteria. We identified five potentially relevant unpublished studies in the most recent searches, but data were not available at this time. The number of included studies therefore remains unchanged.

The NNT for celecoxib 200 mg and 400 mg compared with placebo for at least 50% of maximum pain relief over four to six hours was 4.2 (95% confidence interval (CI) 3.4 to 5.6) and 2.5 (2.2 to 2.9) respectively. The median time to use of rescue medication was 6.6 hours with celecoxib 200 mg, 8.4 with celecoxib 400 mg, and 2.3 hours with placebo. The proportion of participants requiring rescue medication over 24 hours was 74% with celecoxib 200 mg, 63% for celecoxib 400 mg, and 91% for placebo. The NNT to prevent one patient using rescue medication was 4.8 (3.5 to 7.7) and 3.5 (2.9 to 4.6) for celecoxib 200 mg and 400 mg respectively. Adverse events were generally mild to moderate in severity, and were experienced by a similar proportion of participants in celecoxib and placebo groups. One serious adverse event probably related to celecoxib was reported.

Authors’ conclusions

Single-dose oral celecoxib is an effective analgesic for postoperative pain relief. Indirect comparison suggests that the 400 mg dose has similar efficacy to ibuprofen 400 mg.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Acute Pain [*drug therapy]; Administration, Oral; Cyclooxygenase 2 Inhibitors [*administration & dosage]; Pain, Postoperative [*drug therapy]; Pyrazoles [*administration & dosage]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Sulfonamides [*administration & dosage]

MeSH check words: Humans

BACKGROUND

This is an update of a review published in The Cochrane Library in Issue 4, 2008, which in turn updated the review in Issue 1, 2003.

Description of the condition

Acute pain occurs as a result of tissue damage either accidentally due to an injury or as a result of surgery. Acute postoperative pain is a manifestation of inflammation due to tissue injury. The management of postoperative pain and inflammation is a critical component of patient care.

This is one of a series of reviews whose aim is to present evidence for relative analgesic efficacy through indirect comparisons with placebo, in very similar trials performed in a standard manner, with very similar outcomes, and over the same duration. Such relative analgesic efficacy does not in itself determine choice of drug for any situation or patient, but guides policy-making at the local level. The series includes well-established analgesics such as paracetamol (Toms 2008), naproxen (Derry C 2009a), diclofenac (Derry P 2009), and ibuprofen (Derry C 2009b), and newer cyclo-oxygenase-2 selective analgesics, such as lumiracoxib (Roy 2010) and etoricoxib (Clarke 2012). An overview brings together the results from all the individual drug reviews (Moore 2011a).

Acute pain trials

Single-dose trials in acute pain are commonly short in duration, rarely lasting longer than 12 hours. The numbers of participants are small, allowing no reliable conclusions to be drawn about safety.

To show that the analgesic is working it is necessary to use placebo (McQuay 2005). There are clear ethical considerations in doing this. These ethical considerations are answered by using acute pain situations where the pain is expected to go away, and by providing additional analgesia, commonly called rescue analgesia, if the pain has not diminished after about an hour. This is reasonable, because not all participants given an analgesic will have significant pain relief. Approximately 18% of participants given placebo will have significant pain relief (Moore 2006), and up to 50% may have inadequate analgesia with active medicines. The use of additional or rescue analgesia is hence important for all participants in the trials.

Clinical trials measuring the efficacy of analgesics in acute pain have been standardised over many years. Trials have to be randomised and double-blind. Typically, in the first few hours or days after an operation, patients develop pain that is moderate to severe in intensity, and will then be given the test analgesic or placebo. Pain is measured using standard pain intensity scales immediately before the intervention, and then using pain intensity and pain relief scales over the following four to six hours for shorter-acting drugs, and up to 12 or 24 hours for longer-acting drugs. Pain relief of half the maximum possible pain relief or better (at least 50% pain relief) is typically regarded as a clinically useful outcome. For patients given rescue medication it is usual for no additional pain measurements to be made, and for all subsequent measures to be recorded as initial pain intensity or baseline (zero) pain relief (baseline observation carried forward). This process ensures that analgesia from the rescue medication is not wrongly ascribed to the test intervention. In some trials the last observation is carried forward, which gives an inflated response for the test intervention compared to placebo, but the effect has been shown to be negligible over four to six hours (Moore 2005a). Patients usually remain in the hospital or clinic for at least the first six hours following the intervention, with measurements supervised, although they may then be allowed home to make their own measurements in trials of longer duration.

Knowing the relative efficacy of different analgesic drugs at various doses can be helpful. Results from completed reviews of many different analgesics have been brought together to facilitate (indirect) comparisons in a recently published acute pain overview (Moore 2011a), and analgesics relevant to dentistry are discussed in Barden 2004 and Derry 2011.

Description of the intervention

Selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors or ‘coxibs’ were developed to address the problem of upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Hawkey 2001). Celecoxib (brand names Celebrex, Celebra, Onsenal) was one of the first of the new generation of NSAIDs known as selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors (COX-2 inhibitors) or ‘coxibs’, and Celebrex® is currently licensed for the relief of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis pain in many countries around the world, including the United Kingdom and United States of America. The drug is licensed for acute pain in the United States and some other regulatory areas, but not in the United Kingdom. It is available by prescription only in many countries, as 50 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg, or 400 mg capsules, but generic formulations are available in some parts of Asia and the Far East, where patents have expired. It is most often used for chronic painful conditions, such as osteoarthritis, where the usual adult dose is 100 mg to 200 mg twice daily. In acute painful conditions, such as postoperative pain and menstrual pain, up to 400 mg is sometimes given as a single, or starting dose. In primary care in England in 2010, there were 460,000 prescriptions for celecoxib, with almost equal numbers for the 100 mg and 200 mg doses (PACT 2010).

How the intervention might work

NSAIDs have pain-relieving, antipyretic, and anti-inflammatory properties, and are thought to relieve pain by inhibiting cyclo-oxygenases and thus the production of prostaglandins (Hawkey 1999). Prostaglandins occur throughout body tissues and fluids and act to stimulate pain nerve endings and promote/inhibit the aggregation of blood platelets. Cyclo-oxygenase has at least two isoforms: COX-1 and COX-2. COX-1 is constitutive while COX-2 is induced at sites of inflammation and produces the prostaglandins involved in inflammatory responses and pain mediation (Grahame-Smith 2002). Unlike traditional NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and ketoprofen, the coxibs are selective inhibitors, blocking primarily the action of COX-2, providing pain relief and causing fewer gastrointestinal effects (Moore 2005b). In addition, they should not precipitate bleeding events through inhibition of platelet aggregation (Straube 2005).

In common with other NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors can give rise to fluid retention and renal damage (Garner 2002), so particular caution is needed in the elderly (Hawkey 2001). COX-2 inhibitors have been implicated in increased cardiovascular problems in long-term use, but this is complicated by differences in pharmacology and pharmacokinetics (Patrono 2009). Moreover, recent evidence indicates that prior cardiac damage may be a more important trigger than any particular drug or class of drug (Ruff 2011).

OBJECTIVES

To evaluate the analgesic efficacy and safety of celecoxib in the treatment of acute postoperative pain, using methods that permit comparison with other analgesics evaluated in the same way, using wider criteria of efficacy recommended by an in-depth study at the individual patient level (Moore 2005a; Moore 2011b).

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included studies if they were full publications of double-blind trials of a single-dose oral celecoxib against placebo for the treatment of moderate to severe postoperative pain in adults, with at least 10 participants randomly allocated to each treatment group. We included multiple-dose studies if appropriate data from the first dose were available, and included cross-over studies provided that data from the first arm were presented separately.

We excluded studies if they were:

posters or abstracts not followed up by full publication;

reports of trials concerned with pain other than postoperative pain (including experimental pain);

trials using healthy volunteers;

trials where pain relief was assessed by clinicians, nurses or carers (i.e. not patient-reported);

trials of less than four hours’ duration or which failed to present data over four to six hours postdose.

Types of participants

We included studies of adult participants (15 years old or above) with established moderate to severe postoperative pain. For studies using a visual analogue scale (VAS), pain of at least moderate intensity was assumed when the VAS score was greater than 30 mm (Collins 1997). We included trials of patients with postpartum pain provided the pain investigated resulted from episiotomy or Caesarean section (with or without uterine cramp). We excluded trials investigating pain due to uterine cramps alone.

Types of interventions

Orally administered celecoxib or matched placebo for relief of postoperative pain.

Types of outcome measures

Data collected included the following if available:

patient characteristics;

pain model;

patient-reported pain at baseline (physician, nurse, or carer reported pain would not be included in the analysis);

patient-reported pain relief expressed hourly over four to six hours using validated scales, or reported total pain relief (TOTPAR) at four to six hours;

patient-reported pain intensity expressed hourly over four to six hours using validated pain scales, or reported summed pain intensity difference (SPID) at four to six hours;

patient-reported global evaluation of treatment using validated scale;

number of participants using rescue medication, and the time of assessment;

time to use of rescue medication;

withdrawals - all-cause, adverse event;

adverse events - participants experiencing one or more, and any serious adverse event, and the time of assessment.

Primary outcomes

Participants achieving at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours.

Secondary outcomes

Median (or mean) time to use of rescue medication.

Participants using rescue medication.

- Participants with:

- any adverse event;

- any serious adverse event (as reported in the study);

- withdrawal due to an adverse event.

Other withdrawals.

Search methods for identification of studies

We applied no language restriction.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases:

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2011, Issue 12);

MEDLINE via Ovid (1966 to 3 January 2012);

EMBASE via Ovid (1980 to 3 January 2012);

Oxford Pain Database (Jadad 1996a);

ClinicalTrials.gov (on 3 January 2012) for update only.

See Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy, Appendix 2 for the EMBASE search strategy, and Appendix 3 for the Cochrane CENTRAL search strategy.

Searches for the original review were up to May 2002, and for the first update were to July 2008.

Searching other resources

We manually searched reference lists of retrieved studies. We did not search abstracts, conference proceedings, and other grey literature. We did not contact manufacturers. For this update we searched ClinicalTrials.gov for any unpublished and ongoing studies, and attempted to contact the study sponsors for further information.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed and agreed the search results for studies that might be included in the review. We resolved disagreements by consensus or referral to a third review author.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data and recorded on a standard Data Extraction form. One author entered data suitable for pooling into RevMan 5.1 (RevMan 2011).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed each study using a three-item, five-point scale (Jadad 1996b), and agreed a consensus score.

The scale used is as follows.

Is the study randomised? If yes - one point.

Is the randomisation procedure reported and is it appropriate? If yes add one point, if no deduct one point.

Is the study double-blind? If yes then add one point.

Is the double-blind method reported and is it appropriate? If yes add one point, if no deduct one point.

Are the reasons for patient withdrawals and dropouts described? If yes add one point.

We also completed a ‘Risk of bias’ table, considering randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, and size.

Measures of treatment effect

We used relative risk (or ‘risk ratio’, RR) to establish statistical difference. We used numbers needed to treat (NNT) and pooled percentages as absolute measures of benefit or harm.

We use the following terms to describe adverse outcomes in terms of harm or prevention of harm:

When significantly fewer adverse outcomes occur with diclofenac than with control (placebo or active) we use the term the number needed to treat to prevent one event (NNTp).

When significantly more adverse outcomes occur with diclofenac compared with control (placebo or active) we use the term the number needed to harm or cause one event (NNH).

Unit of analysis issues

We accepted only randomisation to the individual patient.

Dealing with missing data

The only likely issue with missing data in these studies is from imputation using last observation carried forward when a patient requests rescue medication. We have previously shown that this does not affect results for up to six hours after taking study medication (Barden 2004).

Assessment of heterogeneity

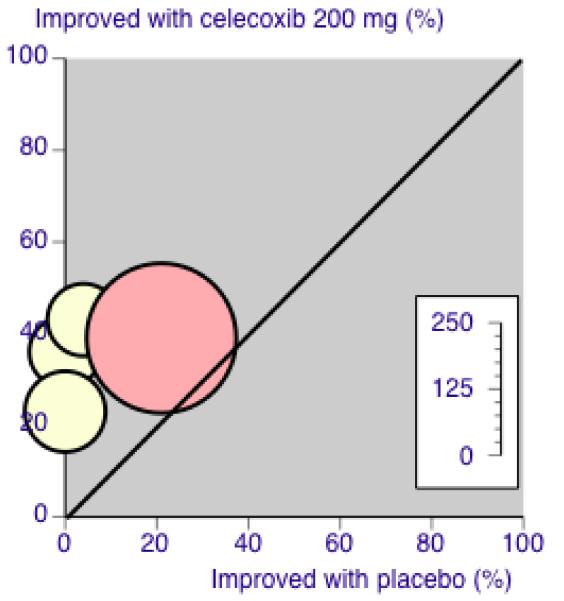

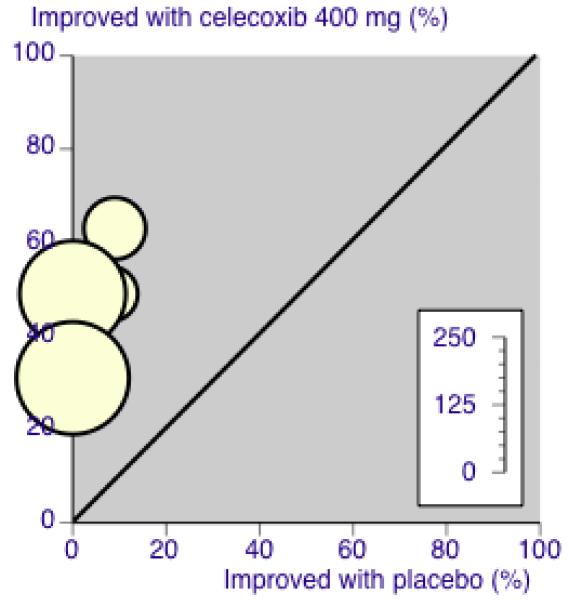

We examined heterogeneity visually using L’Abbé plots (L’Abbé 1987).

Data synthesis

We followed QUOROM guidelines (Moher 1999). For efficacy analyses we used the number of participants in each treatment group who were randomised, received medication, and provided at least one post baseline assessment. For safety analyses we used number of participants randomised to each treatment group who took the study medication. We planned analyses for different doses. For each study we converted the mean TOTPAR, SPID, VAS TOTPAR, or VAS SPID (Appendix 4) values for active and placebo to %maxTOTPAR or %maxSPID by division into the calculated maximum value (Cooper 1991), and calculated the proportion of participants in each treatment group who achieved at least 50%maxTOTPAR using verified equations (Moore 1996; Moore 1997a; Moore 1997b). We then converted these proportions into the number of participants achieving at least 50%max-TOTPAR by multiplying by the total number of participants in the treatment group. We used this information on the number of participants with at least 50%maxTOTPAR for active and placebo to calculate relative benefit or relative risk, and number needed to treat to benefit (NNT).

We accepted the following pain measures for the calculation of TOTPAR or SPID:

five-point categorical pain relief (PR) scales with comparable wording to ‘none, slight, moderate, good or complete’;

four-point categorical pain intensity (PI) scales with comparable wording to ‘none, mild, moderate, severe’;

VAS for pain relief;

VAS for pain intensity.

If none of these measures were available, we used the number of participants reporting ‘very good or excellent’ on a five-point categorical global scale with the wording ‘poor, fair, good, very good, excellent’ for the number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief (Collins 2001).

For each treatment group we extracted the number of participants reporting treatment-emergent adverse effects, and calculated relative benefit and risk estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using a fixed-effect model (Morris 1995). We calculated NNT and number needed to treat to harm (NNH) and 95% CI using the pooled number of events using the method devised by Cook and Sackett (Cook 1995). We assumed a statistically significant difference from control when the 95% CI of the relative risk or relative benefit did not include one.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned subgroup analyses to determine the effect of dose and presenting condition (pain model), and sensitivity analyses for high versus low (two or fewer versus three or more) quality trials. A minimum of two trials and 200 participants had to be available in any subgroup or sensitivity analysis (Moore 1998), which was restricted to the primary outcome (50% pain relief over four to six hours). We determined significant differences between NNT, NNTp, or NNH for different groups in subgroup and sensitivity analyses using the z test (Tramèr 1997).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned sensitivity analyses for pain model (dental versus other postoperative pain), trial size (39 or fewer versus 40 or more per treatment arm), and quality score (2 versus 3 or more).

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Updated searches did not find any published new studies for inclusion. However, we did identify five potentially relevant unpublished studies that are completed.

Two in which celecoxib was used as an active comparator for indomethacin (IND2-08-03) and diclofenac (DIC2-08-03). Both were placebo-controlled. Although these studies are completed, the research programme is still under development and the data remain confidential. The study sponsor (Iroko) has said they will provide notice when they are published.

Two in which celecoxib was used as an active comparator for an experimental compound, ARRY-371797. One (ARRY-797-222) is placebo-controlled, but the other (ARRY-797-221) may not be. We have requested further details from the study sponsor (Array BioPharma).

One in which celecoxib is compared with etodolac and placebo (177-CL-102). We have been unable to contact the study sponsor.

Eight studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were available (Malmstrom 1999; Gimbel 2001; Doyle 2002; Malmstrom 2002; Kellstein 2004; Cheung 2007; Moberly 2007; Fricke 2008). Two studies (Malmstrom 1999; Gimbel 2001) were in the first review. We excluded two studies after reading the full paper (Salo 2003; White 2007). One study (Shirota 2001) is in Chinese and has not been translated. Details of included and excluded studies, and studies awaiting classification, are in the corresponding ‘Characteristics of studies’ tables (Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

Celecoxib 200 mg was used in five treatment arms (Malmstrom 1999; Gimbel 2001; Doyle 2002; Malmstrom 2002; Kellstein 2004), and celecoxib 400 mg in four treatment arms (Malmstrom 2002; Cheung 2007; Moberly 2007; Fricke 2008). In total 1380 participants were analysed; 497 received celecoxib 200 mg, 415 received celecoxib 400 mg, and 468 received placebo.

Seven studies (Malmstrom 1999; Doyle 2002; Malmstrom 2002; Kellstein 2004; Moberly 2007; Cheung 2007; Fricke 2008) enrolled participants with dental pain following extraction of at least one impacted third molar, and one (Gimbel 2001) enrolled participants with pain following uncomplicated orthopaedic surgery. Trial duration was eight hours in two trials, 12 hours in three trials, and 24 hours in three trials. Three trials (Malmstrom 1999; Gimbel 2001; Doyle 2002) were multiple-dose studies, but provided data on the first dose for at least some outcomes.

Risk of bias in included studies

Five studies were given a quality score of five (Malmstrom 1999; Doyle 2002; Malmstrom 2002; Cheung 2007; Fricke 2008), two a score of four (Kellstein 2004; Moberly 2007), and one study a score of three (Gimbel 2001). Details are in the ‘Characteristics of included studies’ table.

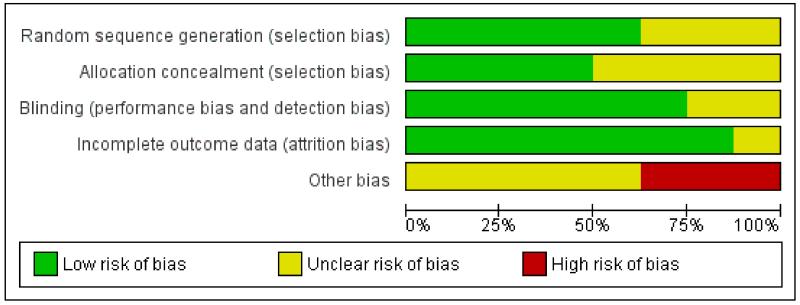

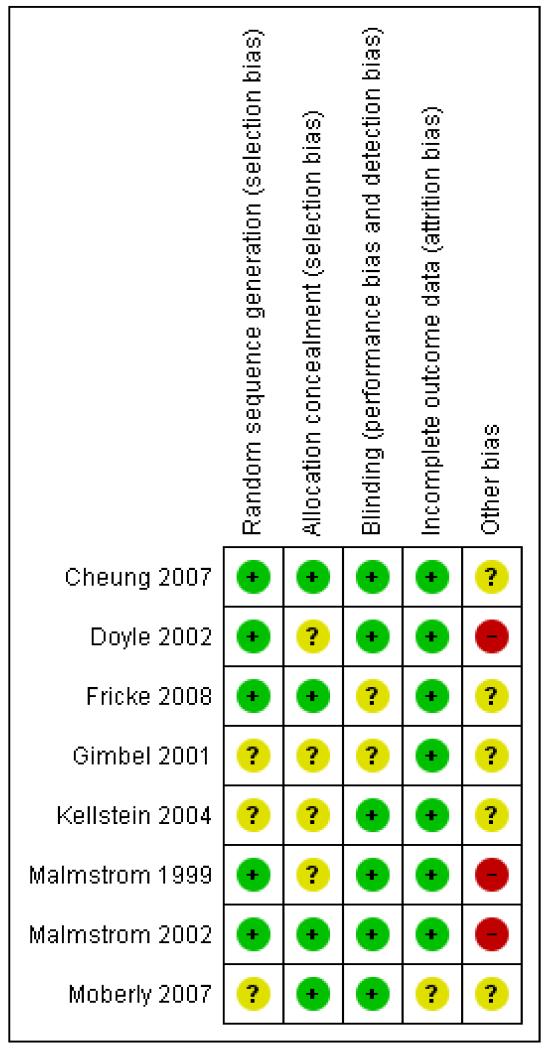

We completed a ‘Risk of bias’ table and results are presented graphically in Figure 1, and summarised in Figure 2. The major threat to reliability was the relatively small size of the studies.

Figure 1. ‘Risk of bias’ graph: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 2. ‘Risk of bias’ summary: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

Eight studies met the inclusion criteria and provided data for analysis. Details of results in individual studies are in Appendix 5 (efficacy) and Appendix 6 (adverse events and withdrawals).

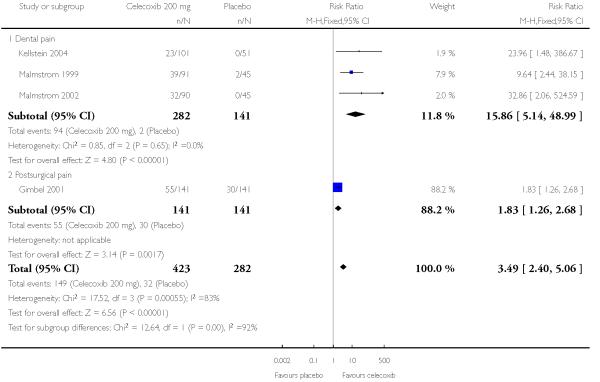

Number of participants achieving at least 50% pain relief

Celecoxib 200 mg versus placebo

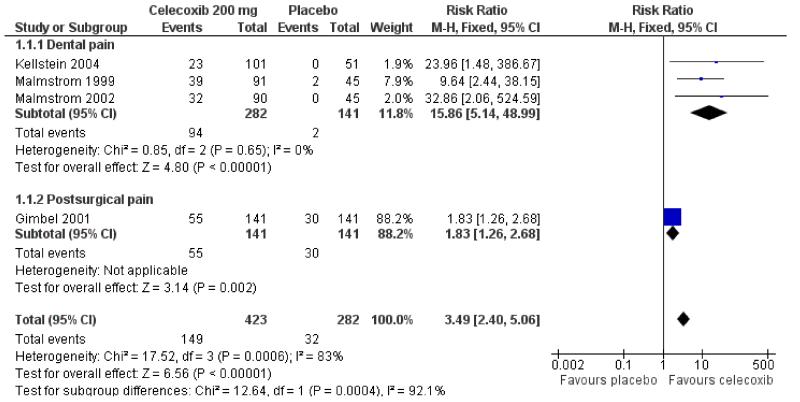

Four studies provided data (Malmstrom 1999; Gimbel 2001; Malmstrom 2002; Kellstein 2004); 423 participants were treated with celecoxib 200 mg and 282 with placebo.

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with celecoxib 200 mg was 35% (149/423).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with placebo was 11% (32/282).

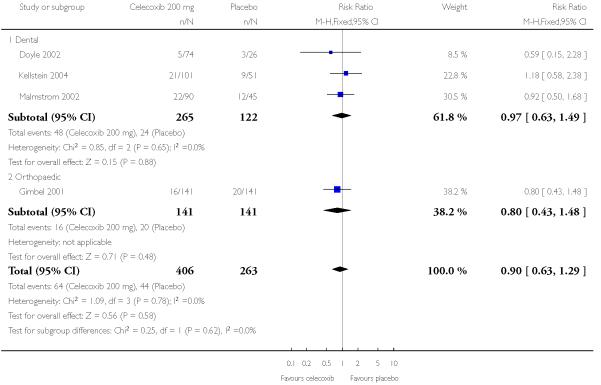

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 3.5 (2.4 to 5.1); the number needed to treat to benefit (NNT) was 4.2 (3.4 to 5.6) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 3; Appendix 7).

Figure 3. Forest plot of comparison: 1 Celecoxib 200 mg versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 At least 50% pain relief over 4-6 hours.

For every four participants treated with celecoxib 200 mg, one would experience at least 50% pain relief who would not have done so with placebo.

Celecoxib 400 mg versus placebo

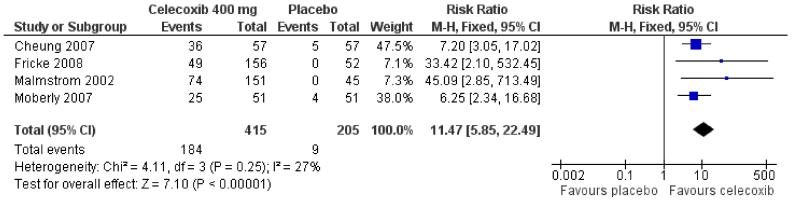

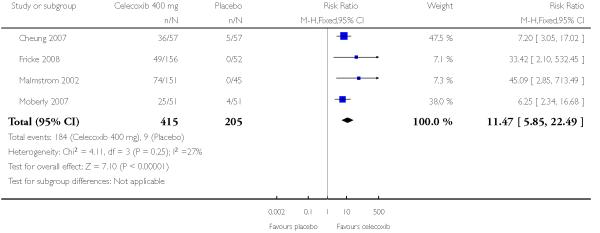

Four studies provided data (Malmstrom 2002; Moberly 2007; Cheung 2007; Fricke 2008); 415 participants were treated with celecoxib 400 mg and 205 with placebo.

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with celecoxib 400 mg was 44% (184/415).

The proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours with placebo was 4% (9/205).

The relative benefit of treatment compared with placebo was 11.5 (5.9 to 22); the NNT was 2.5 (2.2 to 2.9) (Analysis 2.1; Figure 4; Appendix 7).

Figure 4. Forest plot of comparison: 2 Celecoxib 400 mg versus placebo, outcome: 2.1 At least 50% pain relief over 4-6 hours dental pain.

For every five participants treated with celecoxib 400 mg, two would experience at least 50% pain relief who would not have done so with placebo.

There was a significant difference between celecoxib 200 mg and celecoxib 400 mg (z = 3.92, P < 0.0001).

| Summary of results: 50% pain relief over 4 to 6 hours | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg) | Pain model | Studies | Participants | Celecoxib % | Placebo % | Relative benefit (RB) (95% CI) | NNT (95%CI) 50% |

| 200 mg | Dental + Orthopaedic | 4 | 705 | 35 | 11 | 3.5 (2.4 to 5.0) | 4.2 (3.4 to 5.6) |

| 200 mg | Dental | 3 | 423 | 33 | 1 | 16 (5.1 to 49) | 3.2 (2.7 to 3.9) |

| 400 mg | Dental | 4 | 620 | 34 | 4 | 11 (5.9 to 22) | 2.5 (2.2 to 2.9) |

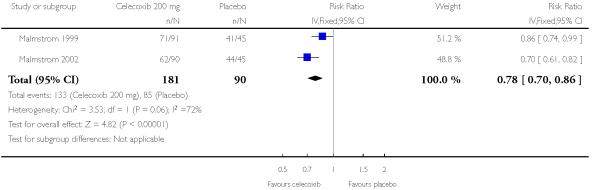

Use of rescue medication

Number of participants using rescue medication over 24 hours

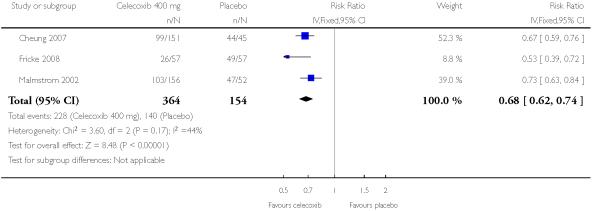

All studies reported some information on use of rescue medication. The time at which use of rescue medication was censored varied between studies. The weighted mean proportion of participants requiring rescue medication by 24 hours was 74% for celecoxib 200 mg (133/181), 63% for celecoxib 400 mg (228/364), and 91% for placebo (181/199 participants). Significantly fewer participants used rescue medication with celecoxib than placebo (200 mg: relative risk (RR) 0.8 (0.7 to 0.9), NNT to prevent use of rescue medication 4.8 (3.5 to 7.7)); 400 mg: RB 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8), NNT to prevent use of rescue medication 3.5 (2.9 to 4.6)). The difference between the two doses of celecoxib was not significant (z = 1.37, P = 0.085).

The proportion of participants requiring rescue medication was also reported at eight hours (Gimbel 2001, 44%) and 12 hours (Doyle 2002, 41%) for celecoxib 200 mg, and at six hours (Moberly 2007, 24%) for celecoxib 400 mg.

| Summary of results: use of rescue medication within 24 hours | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg) | Pain model | Studies | Participants | Celecoxib % | Placebo % | RB (95% CI) | NNTp (95% CI) |

| 200 mg | Dental | 2 | 271 | 73.5 | 94.4 | 0.78 (0.70 to 0.86) | 4.8 (3.5 to 7.8) |

| 400 mg | Dental | 3 | 518 | 62.6 | 90.9 | 0.68 (0.62 to 0.74) | 3.5 (2.9 to 4.6) |

Time to use of rescue medication

The median time to use of rescue medication was highly variable, particularly for the celecoxib treatment arms. It ranged from two to > 12 hours for celecoxib 200 mg, 3.8 to > 12 hours for celecoxib 400 mg, and 1.3 to 3.9 hours for placebo. The weighted mean of the median time to use of rescue medication was 6.6 hours for celecoxib 200 mg, 8.4 hours for celecoxib 400 mg, and 2.3 hours for placebo (2.6 in 200 mg trials and 1.6 in 400 mg trials). For dental studies only the weighted mean of the median time to use of rescue medication was 6.1 hours for celecoxib 200 mg, and 1.6 hours for placebo.

| Summary of results: weighted mean of median time to use of rescue medication | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg) | Pain model | Studies | Participants | Celecoxib (hr) | Placebo (hr) |

| 200 mg | Dental + Orthopaedic | 5 | 805 | 6.6 | 2.6 |

| 200 mg | Dental | 4 | 523 | 6.1 | 1.5 |

| 400 mg | Dental | 4 | 620 | 8.4 | 1.6 |

Adverse events

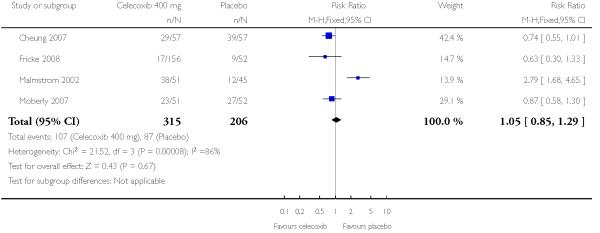

All studies except (Malmstrom 1999) reported the number of participants with one or more adverse event for each treatment arm, although the time over which the information was collected varied between trials, from eight to 24 hours (Appendix 6). It was unclear in some reports whether the adverse event reports covered only the duration of the trial, or whether they included any adverse events occurring between the end of the trial and a follow-up visit some days later. Only one study arm reported a significant difference between placebo and celecoxib (400 mg) (Malmstrom 2002). There was no significant difference between celecoxib 400 mg and placebo when studies were pooled (Analysis 2.3), or for individual or pooled studies for celecoxib 200 mg (Analysis 1.3), so we did not calculate numbers needed to treat to harm (NNHs). Adverse events were generally described as mild to moderate in severity.

| Summary of results: participants with at least one adverse event | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg) | Pain model | Studies | Participants | Celecoxib % | Placebo % | RR (95% CI) | NNH (95%CI) |

| 200 mg | Dental + Orthopaedic | 4 | 669 | 16 | 17 | 0.90 (0.63 to 1.3) | Not calculated |

| 200 mg | Dental | 3 | 382 | 20 | 18 | 0.97 (0.63 to 1.5) | Not calculated |

| 400 mg | Dental | 4 | 521 | 34 | 42 | 1.05 (0.85 to 1.3) | Not calculated |

Two studies reported serious adverse events. Malmstrom 2002 reported one serious adverse event in each of the 200 mg and 400 mg treatment arms. These events were reported at the post study visit and were judged unrelated to the study medication. Cheung 2007 reported one serious adverse event in a participant treated with celecoxib 400 mg. The event, rhabdomyolysis, occurred two days after the study, and was judged to be probably related to the study medication by the trialists, although the patient had received a number of other medications both pre and post study. No statistical analysis of serious adverse events was possible.

One adverse event withdrawal was reported for celecoxib 200 mg (Malmstrom 1999) and for celecoxib 400 mg (Cheung 2007), and four for placebo (Malmstrom 1999; Cheung 2007).

Other withdrawals

Withdrawals for reasons other than lack of efficacy (participants who use rescue medication) were uncommon and usually due to protocol violations (Appendix 6). No further statistical analysis of withdrawals was possible.

Sensitivity analyses

Pain model

One trial using celecoxib 200 mg (Gimbel 2001) included participants who had undergone orthopaedic surgery. Excluding this trial from the primary analysis left dental trials only, giving a relative benefit for treatment compared with placebo of 16 (5.1 to 49), and a NNT for at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours of 3.2 (2.7 to 3.9). This apparently better efficacy in dental trials is due to the fact that the event rate in the placebo group of the orthopaedic trial was much higher (21%) than in the placebo groups of the dental trials (1% to 4%), while the event rate in the celecoxib group of the orthopaedic trial was more similar (39%) to the dental trials (23% to 43%). It is not possible to draw any firm conclusions about the effect of pain model with only one non-dental trial in this data set.

Quality score

All studies scored three or more for quality, so we carried out no sensitivity analysis.

Trial size

All studies enrolled more than 40 participants per treatment arm, so we carried out no sensitivity analysis.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

No new data were available for this updated review. The review in 2008 included 497 participants treated with a single dose of celecoxib 200 mg, more than twice the number as in the first review, giving a more robust (Moore 1998), but almost identical result. It also included 415 participants treated with a single dose of 400 mg celecoxib (NLM 2002). The number needed to treat to benefit (NNT) for 50% pain relief over four to six hours was significantly better for 400 mg (NNT 2.5, 2.2 to 2.9) than for 200 mg (NNT 4.2, 3.4 to 5.6) (P < 0.0001).

The same methods and analyses have been conducted, therefore it is possible to compare the NNT for a single dose of oral celecoxib with that of a single dose of other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Analgesics with comparable efficacy to celecoxib 200 mg include aspirin 600/650 mg (NNT 4.2 (3.8 to 4.6); Derry 2012), and paracetamol 1000 mg (NNT 3.6 (3.2 to 4.1) (Toms 2008). Analgesics with comparable efficacy to celecoxib 400 mg include naproxen 500/550 mg (NNT 2.7 (2.3 to 3.3), (Derry C 2009a), and ibuprofen 400 mg (NNT 2.5 (2.4 to 2.6) (Derry C 2009b). An overview of analgesic efficacy in acute pain summarises all available results (Moore 2011a)

Significantly fewer participants required rescue medication with celecoxib than with placebo. The NNTs to prevent one patient remedicating within 24 hours were 4.8 for celecoxib 200 mg and 3.5 for celecoxib 400 mg, but the difference was not significant (P = 0.085). The median time to use of rescue medication varied greatly between trials, particularly for the active treatment arms, but was generally longer for celecoxib than placebo, and for celecoxib 400 mg than celecoxib 200 mg. The weighted mean of the median time to use of rescue medication at 6.6 hours for celecoxib 200 mg and 8.4 hours for celecoxib 400 mg is longer than for some non-selective NSAIDs (ibuprofen 400 mg 5.6 hours, diclofenac 50 mg 4.3 hours), though not all (naproxen 500 mg 8.9 hours) but shorter than other coxibs (etoricoxib 120 mg 20 hours, rofecoxib 50 mg 14 hours, lumiracoxib nine hours). Longer duration of action is desirable in an analgesic, particularly in a postoperative setting where the patient may experience postoperative nausea or be dependent on a third party to respond to a request for rescue medication (or both). Duration of pain relief and requirement for rescue medication information have only recently been recognised as important outcomes (Moore 2005a), and a fuller evaluation of the importance of these outcomes will depend on more data being collected from other, ongoing, systematic reviews.

Assessment of adverse events is limited in single-dose studies as the size and duration of the trials permits only the simplest analysis, as has been emphasised previously (Edwards 1999b). There were insufficient data in these studies to compare individual adverse events. There was no significant difference between celecoxib and placebo for numbers of participants experiencing any adverse event in the hours immediately following a single dose of the study medication. Although all but one trial reported this outcome, combining results was potentially hampered by the different periods over which the data were collected. Most adverse events were reported as mild to moderate in intensity, and were most likely to be related to the anaesthetic or surgical procedure (e.g. nausea, vomiting, and somnolence). Serious adverse events and withdrawals due to adverse events occurred in both celecoxib and placebo treatment arms, but were uncommon and too few for any statistical analysis. It is important to recognise that adverse event analysis after single-dose oral administration will not reflect possible adverse events occurring with use of drugs for longer periods of time. In addition, the numbers of participants are insufficient to detect rare but serious adverse events.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Included studies reported useful data for both primary and secondary outcomes, with the exception of Doyle 2002 for the primary outcome. Seven studies enrolled participants with dental pain following extraction of at least one impacted third molar. These individuals are generally in their early 20s, and are otherwise fit and healthy, so are clearly not representative of the range of individuals who might need analgesia for acute postoperative pain. There is no a priori reason why analgesic response in these individuals should differ in any systematic way from a more generalised population, but it is entirely possible that adverse events (gastrointestinal in particular) may be more frequent, intense, or severe in older patients, and those with comorbidities. The remaining study (Gimbel 2001) was carried out in patients with pain following uncomplicated orthopaedic surgery. The placebo response in this study was unusually high (21%), which gave reduced efficacy, but it is impossible to speculate whether there is a real difference between pain conditions where there is only one study to consider. Differences between different pain models have either not been demonstrable in the past (Barden 2004), or have been possible to demonstrate only where there are an abundance of data (e.g. for ibuprofen; Derry C 2009b).

There were no data available for lower doses of celecoxib, so conclusions/inferences about the benefit and harm of a lower dose cannot be made.

The unavailability of five completed randomised trials means that not all of the extant information on celecoxib in acute pain was available for analysis.

Quality of the evidence

All studies were of adequate methodological quality, with five scoring 5/5 on the Oxford Quality Scale, and all administered the medication when pain levels were moderate or severe, ensuring that the study was sensitive to detect a 50% reduction.

Potential biases in the review process

We carried out a comprehensive search for relevant studies, and investigated the potential influence of publication bias by examining the number of participants in trials with zero effect (relative risk of 1.0) needed for the point estimate of the NNT to increase beyond a clinically useful level (Moore 2008). In this case, we chose a clinically useful level as 8. For the primary outcome of at least 50% pain relief with celecoxib 200 mg, about 640 participants would have to have been involved in unpublished trials with zero treatment effects for the NNT to increase above this threshold. For celecoxib 400 mg, twice as many (1360) participants in unpublished trials would be needed. Given that we know of five unpublished studies, it is possible, although unlikely, that these results could be overturned, although efficacy estimates could be changed.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We are not aware of any other systematic reviews of celecoxib in treating acute postoperative pain.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

No new publications have been identified that provide data for analysis, so the conclusions of the previous review are unchanged. Celecoxib at its recommended dosage of 400 mg for acute pain is an effective analgesic, equivalent to ibuprofen 400 mg, but providing a longer duration of pain relief than many traditional NSAIDs. Significantly fewer individuals achieve effective pain relief with celecoxib 200 mg than with celecoxib 400 mg.

Implications for research

There are no major implications for research other than the possible benefits that are known to come from single-patient analysis, allowing different ways of reporting trial results which can be more useful to clinical practices (Edwards 1999a).

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Single-dose oral celecoxib for postoperative pain

Celecoxib was one of the first of the new generation of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) known as COX-2 inhibitors. Compared with conventional NSAIDs celecoxib has fewer gastrointestinal side effects with long-term use. It is used for the relief of chronic pain caused by osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. This review examined the efficacy of celecoxib in relieving acute pain. Eight trials provided data. Just over 3 in 10 people (33%) taking celecoxib 200 mg, and over 4 in 10 (44%) taking celecoxib 400 mg experienced a good level of pain relief (at least 50%), compared with about 1 in 10 (range 1 to 11%) with placebo. Indirect comparisons indicate that the 200 mg dose of celecoxib is at least as effective as aspirin 600/650 mg and paracetamol (acetaminophen) 1000 mg for relieving postoperative pain, while a 400 mg dose is at least as effective as ibuprofen 400 mg. Adverse events occurred at a similar rate with celecoxib and placebo. One serious adverse event (rhabdomyolysis - muscle breakdown) was probably related to celecoxib. Withdrawals due to adverse events were few and occurred at similar rates with celecoxib and placebo.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This update was supported by funds from the Oxford Pain Relief Trust. The first update was supported by the NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant Scheme.

Jodie Barden, Jane Edwards, and Henry McQuay were involved in the earlier reviews.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

Oxford Pain Relief Trust, UK.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT, DB single oral dose, 3 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90 mins then hourly up to 12 h, and at 16 and 24 h |

|

| Participants | Impacted third molar extraction Mean age 22 years N = 171 M = 77, F = 94 |

|

| Interventions | Celecoxib 400 mg, n = 57 Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 57 Placebo, n = 57 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4-point scale PR: std 5-point scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication Number of participants reporting any adverse event and serious adverse events Number of participants withdrawing due to adverse event |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1 Participants asked to refrain from rescue medication for 1 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “computer-generated randomization schedule, prepared before the start of the study” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Medication supplied in patient-specific carton. Identity of assignment contained in concealed section of label, which was removed at dispensing, and attached to patient case report form |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-blind method. Placebo capsules or tablets identical in number and appearance to active treatments |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | All participants accounted for; analysis appropriate for relevant time interval |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Small treatment group size (57 participants) |

| Methods | RCT, DB single oral and multiple oral dose, 3 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90 mins then hourly up to 12 h |

|

| Participants | Impacted third molar extraction Mean age 22 years N = 174 M = 75, F = 99 |

|

| Interventions | Celecoxib 200 mg, n = 74 Ibuprofen liquigel 400 mg, n = 74 Placebo, n = 26 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: 4-point scale PR: 5-point scale PGE: std 5-point scale (patients reporting “very good” or “excellent”) Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication Number of participants reporting any adverse event and serious adverse events Number of participants withdrawing due to adverse event |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1 Participants asked to refrain from rescue medication for 1 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “computer-generated allocation schedule” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-dummy method. “The appearance, presentation and labelling of the placebo formulations were identical to those of the corresponding active drugs” |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Participants accounted for; analysis appropriate for relevant time interval |

| Other bias | High risk | Small treatment group size (74 active, 26 placebo participants) |

| Methods | RCT, DB, double-dummy, single oral dose, 3 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90 mins then hourly up to 12 h, and at 24 h |

|

| Participants | Impacted third molar extraction Mean age 23 years N = 364 M = 133, F = 231 |

|

| Interventions | Celecoxib 400 mg, n = 156 Lumiracoxib 400 mg, n = 156 Placebo, n = 52 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4-point scale PR: std 5-point scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication Number of participants reporting any adverse event and serious adverse events Number of participants withdrawing due to adverse event |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB1, W1 Participants permitted to use rescue medication at any time |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer-generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Remote, automated allocation to randomisation numbers |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Participants accounted for; analysis appropriate for relevant time interval |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Small treatment group size (156 active, 52 placebo participants) |

| Methods | RCT, DB single oral and multiple oral dose, 3 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90 mins then hourly up to 8 h. Multiple-dose phase continued over 3 days |

|

| Participants | Orthopaedic surgery (uncomplicated) Mean age 46 years N = 418 M = 165, F = 253 |

|

| Interventions | Celecoxib 200 mg, n = 141 Hydrocodone 10 mg + acetaminophen 1000 mg, n = 136 Placebo, n = 141 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4-point scale PR: std 5-point scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication Number of participants reporting any adverse event and serious adverse events Number of participants withdrawing due to adverse event |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB1, W1 Participants permitted to use rescue medication at any time |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Participants accounted for; analysis appropriate for relevant time interval |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Small treatment group size (136 to 141 participants) |

| Methods | RCT, DB, double-dummy, single oral dose, 4 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90 mins then hourly up to 12 h, and at 24 h |

|

| Participants | Impacted third molar extraction Mean age 22 years N = 355 M = 112, F = 243 |

|

| Interventions | Celecoxib 200 mg, n = 101 Lumiracoxib 400 mg, n = 101 Rofecoxib 50 mg, n = 102 Placebo, n = 51 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4-point scale PR: std 5-point scale PGE: std 5-point scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1 Participants asked to refrain from rescue medication for 1 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-dummy method. Placebo capsules and tablets matching corresponding active treatments |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Participants accounted for; analysis appropriate for relevant time interval |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Small treatment group size (100 to 101 active, 51 placebo participants) |

| Methods | RCT, DB single oral dose and multiple oral dose, 4 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 mins, then at 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 h |

|

| Participants | Impacted third molar extraction Mean age 23 years N = 272 M = 100, F = 172 |

|

| Interventions | Celecoxib 200 mg, n = 91 Rofecoxib 50 mg, n = 90 Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 46 Placebo, n = 45 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4-point scale PR: std 5-point scale PGE: std 5-point scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1 Participants asked to refrain from rescue medication for 1.5 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “computer-generated allocation schedule” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-dummy method, using marketed tablet or capsule formulations or matching placebos |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Participants accounted for; analysis appropriate for relevant time interval |

| Other bias | High risk | Small treatment group size (90, 91 coxib, 45,46 ibuprofen, and placebo participants) |

| Methods | RCT, DB single oral dose, 5 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 mins, then at 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 12 h |

|

| Participants | Impacted third molar extraction Mean age 22 years N = 482 M = 124, F = 358 |

|

| Interventions | Celecoxib 400 mg, n = 151 Celecoxib 200 mg, n = 90 Rofecoxib 50 mg, n = 150 Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 45 Placebo, n = 45 |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4-point scale PR: std 5-point scale PGE: std 5-point scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R2, DB2, W1 Participants asked to refrain from rescue medication for 1.5 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “computer-generated allocation schedule” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants allocated to next randomisation number (lowest for moderate pain, highest for severe pain) |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-dummy method. Each active treatment had matching placebo tablets or capsules |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Participants accounted for; analysis appropriate for relevant time interval |

| Other bias | High risk | Small treatment group size (90 to 151 coxib, 45 to 50 ibuprofen, and placebo participants) |

| Methods | RCT, DB single oral dose, 6 parallel groups Medication administered when baseline pain reached a moderate to severe intensity Pain assessed at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 mins, then at 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, and 24 h |

|

| Participants | Impacted third molar extraction Mean age 22 years N = 304 M = 111, F = 193 |

|

| Interventions | Celecoxib 400 mg, n = 51 Placebo, n = 52 CS-706 also tested at 10, 50, 100, 200 mg |

|

| Outcomes | PI: std 4-point scale PR: std 5-point scale PGE: std 5-point scale Time to use of rescue medication Number of participants using rescue medication |

|

| Notes | Oxford Quality Score: R1, DB2, W1 Participants asked to refrain from rescue medication for 1.5 h |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Investigator, all study staff and related personnel were unaware of treatment assignment |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Double-dummy method. Matching tablets for CS-706 and corresponding placebo. Celecoxib and corresponding placebo capsules differed in markings, so participant blindfolded and treatment administered by a third party |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Participants accounted for; analysis appropriate for relevant time interval |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Small treatment group size (50 to 51 participants) |

RCT - randomised controlled trial; R - randomisation; DB - double blind; W - withdrawals; PI - pain intensity; PR - pain relief; PGE - patient global evaluation; std - standard

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Salo 2003 | No placebo group; included participants with musculoskeletal injuries, not postoperative pain |

| White 2007 | Not established moderate to severe pain |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, duration 2 days Medication given when pain ≥ moderate |

| Participants | Postoperative pain M and F, age ≥ 20 years N = 616 |

| Interventions | Celecoxib Etodolac Placebo Doses not given |

| Outcomes | Patient impression Pain intensity, pain intensity difference Discontinuation due to lack of efficacy Adverse events |

| Notes | May not have single-dose data Primary completion date November 2010 |

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | Mentioned as “recently completed postoperative pain study” in ARRY-797-22 |

| Methods | Randomised, double-blind, single-dose, parallel-group, duration 6 h (to second dose) Medication given when pain > moderate |

| Participants | Surgical removal of ≥ 3 third molars (1 mandibular and impacted) M and F, age 18 to 50 years N = 250 |

| Interventions | Celecoxib 400 mg ARRY-31797 200mg ARRY-31797 400 mg ARRY-31797 600 mg Placebo |

| Outcomes | TOTPAR (dose 1) Use of rescue medication Adverse events |

| Notes | Primary completion June 2008 |

| Methods | Randomised, double-blind, single-dose, parallel-group, duration 12 h Medication given when pain ≥ moderate |

| Participants | Surgical removal of ≥ 2 impacted third molars M and F, age 18 to 50 years N = 202 |

| Interventions | Celecoxib 400 mg Diclofenac, lower dose Diclofenac, higher dose Placebo |

| Outcomes | TOTPAR |

| Notes | Primary completion December 2010 |

| Methods | Randomised, double-blind, single-dose, parallel-group, duration 8 h Medication given when pain ≥ moderate |

| Participants | Surgical removal of ≥ 2 impacted third molars M and F, age 18 to 50 years N = 203 |

| Interventions | Celecoxib 400 mg Indomethacin, lower dose Indomethacin, higher dose Placebo |

| Outcomes | TOTPAR |

| Notes | Primary completion December 2010 |

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | Awaiting translation (Chinese) |

DATA AND ANALYSES

Comparison 1. Celecoxib 200 mg versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 At least 50% pain relief over 4-6 hours | 4 | 705 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.49 [2.40, 5.06] |

| 1.1 Dental pain | 3 | 423 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 15.86 [5.14, 48.99] |

| 1.2 Postsurgical pain | 1 | 282 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.83 [1.26, 2.68] |

| 2 Use of rescue medication over 24 hours | 2 | 271 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.70, 0.86] |

| 3 Any adverse event | 4 | 669 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.63, 1.29] |

| 3.1 Dental | 3 | 387 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.63, 1.49] |

| 3.2 Orthopaedic | 1 | 282 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.8 [0.43, 1.48] |

Comparison 2. Celecoxib 400 mg versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 At least 50% pain relief over 4-6 hours, dental pain | 4 | 620 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 11.47 [5.85, 22.49] |

| 2 Use of rescue medication over 24 hours | 3 | 518 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.62, 0.74] |

| 3 Any adverse event | 4 | 521 | Risk Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.85, 1.29] |

Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Celecoxib 200 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 At least 50% pain relief over 4-6 hours.

Review: Single dose oral celecoxib for acute postoperative pain in adults

Comparison: 1 Celecoxib 200 mg versus placebo

Outcome: 1 At least 50% pain relief over 4-6 hours

|

Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Celecoxib 200 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Use of rescue medication over 24 hours.

Review: Single dose oral celecoxib for acute postoperative pain in adults

Comparison: 1 Celecoxib 200 mg versus placebo

Outcome: 2 Use of rescue medication over 24 hours

|

Analysis 1.3. Comparison 1 Celecoxib 200 mg versus placebo, Outcome 3 Any adverse event.

Review: Single dose oral celecoxib for acute postoperative pain in adults

Comparison: 1 Celecoxib 200 mg versus placebo

Outcome: 3 Any adverse event

|

Analysis 2.1. Comparison 2 Celecoxib 400 mg versus placebo, Outcome 1 At least 50% pain relief over 4-6 hours, dental pain.

Review: Single dose oral celecoxib for acute postoperative pain in adults

Comparison: 2 Celecoxib 400 mg versus placebo

Outcome: 1 At least 50% pain relief over 4-6 hours, dental pain

|

Analysis 2.2. Comparison 2 Celecoxib 400 mg versus placebo, Outcome 2 Use of rescue medication over 24 hours.

Review: Single dose oral celecoxib for acute postoperative pain in adults

Comparison: 2 Celecoxib 400 mg versus placebo

Outcome: 2 Use of rescue medication over 24 hours

|

Analysis 2.3. Comparison 2 Celecoxib 400 mg versus placebo, Outcome 3 Any adverse event.

Review: Single dose oral celecoxib for acute postoperative pain in adults

Comparison: 2 Celecoxib 400 mg versus placebo

Outcome: 3 Any adverse event

|

Appendix 1. MEDLINE via OVID search strategy

celecoxib.sh

(celecoxib OR celebrex OR Celebra OR Onsenal).ti.ab.kw.

1 OR 2

PAIN, POSTOPERATIVE.sh

((postoperative adj4 pain$) or (post-operative adj4 pain$) or post-operative-pain$ or (post$ NEAR pain$) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi$) or (post-perative adj4 analgesi$) or (“post-operative analgesi$”)).ti,ab,kw.

((post-surgical adj4 pain$) or (“post surgical” adj4 pain$) or (post-surgery adj4 pain$)).ti,ab,kw.

((“pain-relief after surg$”) or (“pain following surg$”) or (“pain control after”)).ti,ab,kw.

((“post surg$” or post-surg$) AND (pain$ or discomfort)).ti,ab,kw.

((pain$ adj4 “after surg$”) or (pain$ adj4 “after operat$”) or (pain$ adj4 “follow$ operat$”) or (pain$ adj4 “follow$ surg$”)).ti,ab,kw.

((analgesi$ adj4 “after surg$”) or (analgesi$ adj4 “after operat$”) or (analgesi$ adj4 “follow$ operat$”) or (analgesi$ adj4 “follow$ surg$”)).ti,ab,kw.

OR/4-10

randomized controlled trial.pt.

controlled clinical trial.pt.

randomized.ab.

placebo.ab.

drug therapy.fs.

randomly.ab.

trial.ab.

groups.ab.

OR/12-19

3 AND 11 AND 20

Appendix 2. EMBASE via Ovid search strategy

celecoxib.sh.

(celecoxib OR celebrex OR Celebra OR Onsenal).ti.ab.kw.

OR/1-2

PAIN, POSTOPERATIVE.sh.

((postoperative adj4 pain$) or (post-operative adj4 pain$) or post-operative-pain$ or (post$ NEAR pain$) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi$) or (post-operative adj4 analgesi$) or (“post-operative analgesi$”)).ti.ab.kw.

((post-surgical adj4 pain$) or (“post surgical” adj4 pain$) or (post-surgery adj4 pain$)).ti.ab.kw.

((“pain-relief after surg$”) or (“pain following surg$”) or (“pain control after”)).ti.ab.kw.

((“post surg$” or post-surg$) AND (pain$ or discomfort)).ti.ab.kw.

((pain$ adj4 “after surg$”) or (pain$ adj4 “after operat$”) or (pain$ adj4 “follow$ operat$”) or (pain$ adj4 “follow$ surg$”)).ti.ab.kw.

((analgesi$ adj4 “after surg$”) or (analgesi$ adj4 “after operat$”) or (analgesi$ adj4 “follow$ operat$”) or (analgesi$ adj4 “follow$ surg$”)).ti.ab.kw.

OR/4-10

clinical trials.sh.

controlled clinical trials.sh.

randomized controlled trial.sh.

double-blind procedure.sh.

(clin$ adj25 trial$).ab.

((doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ab.

placebo$.ab.

random$.ab.

OR/12-19

3 AND 11 AND 20

Appendix 3. Cochrane CENTRAL search strategy

MESH descriptor celecoxib

(celecoxib OR celebrexOR Celebra OR Onsenal):ti.ab.kw.

OR/1-2

MESH descriptor PAIN, POSTOPERATIVE

((postoperative adj4 pain$) or (post-operative adj4 pain$) or post-operative-pain$ or (post$ NEAR pain$) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi$) or (post-operative adj4 analgesi$) or (“post-operative analgesi$”)):ti.ab.kw.

((post-surgical adj4 pain$) or (“post surgical” adj4 pain$) or (post-surgery adj4 pain$)):ti.ab.kw.

((“pain-relief after surg$”) or (“pain following surg$”) or (“pain control after”)):ti.ab.kw.

((“post surg$” or post-surg$) AND (pain$ or discomfort)):ti.ab.kw.

((pain$ adj4 “after surg$”) or (pain$ adj4 “after operat$”) or (pain$ adj4 “follow$ operat$”) or (pain$ adj4 “follow$ surg$”)): ti.ab.kw.

((analgesi$ adj4 “after surg$”) or (analgesi$ adj4 “after operat$”) or (analgesi$ adj4 “follow$ operat$”) or (analgesi$ adj4 “follow$ surg$”)):ti.ab.kw.

OR/4-10

Limit 11 to Clinical Trials (CENTRAL)

Appendix 4. Glossary

Categorical rating scale

The commonest is the five category scale (none, slight, moderate, good or lots, and complete). For analysis numbers are given to the verbal categories (for pain intensity, none = 0, mild = 1, moderate = 2, and severe = 3, and for relief none = 0, slight = 1, moderate = 2, good or lots = 3, and complete = 4). Data from different subjects is then combined to produce means (rarely medians) and measures of dispersion (usually standard errors of means). The validity of converting categories into numerical scores was checked by comparison with concurrent visual analogue scale measurements. Good correlation was found, especially between pain relief scales using cross-modality matching techniques. Results are usually reported as continuous data, mean or median pain relief or intensity. Few studies present results as discrete data, giving the number of participants who report a certain level of pain intensity or relief at any given assessment point. The main advantages of the categorical scales are that they are quick and simple. The small number of descriptors may force the scorer to choose a particular category when none describes the pain satisfactorily.

Visual analogue scale (VAS)

Analogue scale: lines with left end labelled ‘no relief of pain’ and right end labelled ‘complete relief of pain’, seem to overcome this limitation. Patients mark the line at the point which corresponds to their pain. The scores are obtained by measuring the distance between the no relief end and the patient’s mark, usually in millimetres. The main advantages of VAS are that they are simple and quick to score, avoid imprecise descriptive terms, and provide many points from which to choose. More concentration and co-ordination are needed, which can be difficult postoperatively or with neurological disorders.

TOTPAR

Total pain relief (TOTPAR) is calculated as the sum of pain relief scores over a period of time. If a patient had complete pain relief immediately after taking an analgesic, and maintained that level of pain relief for six hours, they would have a six-hour TOTPAR of the maximum of 24. Differences between pain relief values at the start and end of a measurement period are dealt with by the trapezoidal rule.

SPID

Summed pain intensity difference (SPID) is calculated as the sum of the differences between the pain scores over a period of time. Differences between pain intensity values at the start and end of a measurement period are dealt with by the trapezoidal rule.

VAS TOTPAR and VAS SPID are visual analogue versions of TOTPAR and SPID.

See ‘Measuring pain’ in Bandolier’s Little Book of Pain, Oxford University Press, Oxford. 2003; pp 7-13 (Moore 2003).

Appendix 5. Summary of outcomes in individual studies: efficacy

| Analgesia | Rescue medication | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study ID | Treatment | PI or PR | Number with 50% PR | PGE: very good or excellent | Median time to use (hr) | Number using |

| Malmstrom 1999 |

|

TOTPAR 6:

|

|

At 8 hrs:

|

|

In 24 hrs:

|

| Gimbel 2001 |

|

SPID 6:

|

|

No data |

|

At 8 hrs:

|

| Malmstrom 2002 |

|

TOTPAR 6:

|

|

At 8 hrs:

Pts did not report - assume poor response |

|

At 24 hrs:

|

| Kellstein 2004 |

|

TOTPAR 6:

|

|

No usable data |

|

14.9% of whole group |

| Moberly 2007 |

|

TOTPAR 4:

|

|

At 24 hrs:

|

|

At 6 hrs:

|

| Doyle 2002 |

|

No usable data | No data | No usable data |

|

At 12 hrs:

|

| Cheung 2007 |

|

TOTPAR 6:

|

|

No data |

|

At 24 hrs:

|

| Fricke 2008 |

|

TOTPAR 6:

|

|

No usable data |

|

At 24 hrs:

|

cele - celecoxib; CS-706 - experimental compound; hydrocod/paracet - hydrocodone/paracetamol; ibu - ibuprofen; lumira - lumira-coxib; pts - participants; rofe - rofecoxib

Appendix 6. Summary of outcomes in individual studies: adverse events and withdrawals

| Adverse events | Withdrawals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study ID | Treatment | Any | Serious | Adverse event | Other |

| Malmstrom 1999 |

|

No useable data Mostly nausea, vomiting, headache | None reported |

|

None |

| Gimbel 2001 |

|

to 8 hrs:

Mostly nausea, vomiting, somnolence, headache |

None reported |

|

None |

| Malmstrom 2002 |

|

To 24 hrs:

Mostly nausea and vomiting |

|

None reported | None |

| Kellstein 2004 |

|

To 24 hrs:

|

None | None | None |

| Moberly 2007 |

Also tested CS-706 at 10, 50, 100, 200 mg |

To 24 hrs:

Drug-related: (1) 5/51; (2) 13/52 |

None | None | 1 placebo pt had protocol violation (rescue medication early) - excluded from ITT analysis |

| Doyle 2002 |

|

To 12 hrs:

Most mild to moderate, nausea, vomiting, headache |

None |

|

5 pts (2 cele) excluded from analysis due to protocol violation, admin reason, withdrew consent |

| Cheung 2007 |

|

To 24 hrs:

|

|

|

1 placebo pt withdrew consent |

| Fricke 2008 |

|

To 24 hrs:

|

None | None | None |

cele - celecoxib; CS-706 - experimental compound; hydrocod/paracet - hydrocodone/paracetamol; ibu - ibuprofen; ITT - intention-to-treat; lumira - lumiracoxib; pts - patients; rofe - rofecoxib

Appendix 7. L’Abbé plots

Figure 5. L’Abbé plot of celecoxib 200 mg versus placebo for at least 50% pain relief. Size of circle is proportional to size of study (inset scale). Cream circles - dental studies; pink circle - orthopaedic study.

Figure 6. L’Abbé plot of celecoxib 400 mg versus placebo for at least 50% pain relief. Size of circle is proportional to size of study (inset scale). Cream circles - dental studies.

WHAT’S NEW

Last assessed as up-to-date: 3 January 2012.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 January 2012 | New search has been performed | Searches updated. No new studies with available data identified. Five potentially relevant, completed, but unpublished studies identified; data not yet available. Conclusions unchanged |

| 3 January 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The search for this review update was brought up to date to January 2012 |

HISTORY

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2003

Review first published: Issue 2, 2003

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 September 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 7 November 2008 | Amended | Further RevMan 5 changes. |

| 22 July 2008 | New search has been performed | This is an update of the original review published in Issue 2, 2003 |

| 22 July 2008 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | This review now contains data from eight studies using celecoxib 400mg and 200mg (1380 participants), compared with two (418 participants) at 200 mg previously. In addition to the proportion of participants with at least 50% pain relief over six hours, the update collected information on median time to use of rescue medication. This may be a more useful practical outcome |

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST: SD has no interests to declare. RAM has consulted for various pharmaceutical companies and received lecture fees from pharmaceutical companies related to analgesics and other healthcare interventions. Both authors have received research support from charities, government, and industry sources at various times: no such support was received for this work.

References to studies included in this review

- Cheung 2007 {published data only} .Cheung R, Krishnaswami S, Kowalski K. Analgesic efficacy of celecoxib in postoperative oral surgery pain: a single-dose, two-center, randomized, double-blind, active- and placebo-controlled study. Clinical Therapeutics. 2007;29(Suppl):2498–510. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle 2002 {published data only} .Doyle G, Jayawardena S, Ashraf E, Cooper SA. Efficacy and tolerability of nonprescription ibuprofen versus celecoxib for dental pain. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2002;42(8):912–9. doi: 10.1177/009127002401102830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke 2008 {published data only} .Fricke J, Davis N, Yu V, Krammer G. Lumiracoxib 400 mg compared with celecoxib 400 mg and placebo for treating pain following dental surgery: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Pain. 2008;9(1):20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimbel 2001 {published data only} .Gimbel JS, Brugger A, Zhao W, Verburg KM, Geis GS. Efficacy and tolerability of celecoxib versus hydrocodone/acetaminophen in the treatment of pain after ambulatory orthopedic surgery in adults. Clinical Therapeutics. 2001;23(2):228–41. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellstein 2004 {published data only} .Kellstein D, Ott D, Jayawardene S, Fricke J. Analgesic efficacy of a single dose of lumiracoxib compared with rofecoxib, celecoxib and placebo in the treatment of post-operative dental pain. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2004;58(3):244–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2004.00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmstrom 1999 {published data only} .Malmstrom K, Daniels S, Kotey P, Seidenburg BC, Desjardins PJ. Comparison of rofecoxib and celecoxib, two cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, in postoperative dental pain: a randomised, placebo- and active-comparator-controlled clinical trial. Clinical Therapeutics. 1999;21(10):1653–63. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(99)80045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmstrom 2002 {published data only} .Malmstrom K, Fricke JR, Kotey P, Kress B, Morrison B. A comparison of rofecoxib versus celecoxib in treating pain after dental surgery: a single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-comparator-controlled, parallel-group, single-dose study using the dental impaction pain model. Clinical Therapeutics. 2002;24(10):1549–60. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)80059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberly 2007 {published data only} .Moberly JB, Xu J, Desjardins PJ, Daniels SE, Bandy DP, Lawson JE, et al. A randomized, double-blind, celecoxib- and placebo-controlled study of the effectiveness of CS-706 in acute postoperative dental pain. Clinical Therapeutics. 2007;29(3):399–412. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(07)80078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

- Salo 2003 {published data only} .Salo DF, Lavery R, Varma V, Goldberg J, Shapiro T, Kenwood A. A randomized, clinical trial comparing oral celecoxib 200 mg, celecoxib 400 mg, and ibuprofen 600 mg for acute pain. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2003;10:22–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White 2007 {published data only} .White PF, Sacan O, Tufanogullari B, Eng M, Nuangchamnong N, Ogunnaike B. Effect of short-term postoperative celecoxib administration on patient outcomeafter outpatient laparoscopic surgery. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2007;54(5):342–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03022655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

- 177-CL-102 {unpublished data only} .An etodolac- and placebo-controlled, multicenter, double-blind, group comparison study to verify the efficacy of YM177 (Celecoxib) in postoperative pain patients. CTG: NCT01118572. [Google Scholar]

- ARRY-797-221 {unpublished data only}

- ARRY-797-222 {unpublished data only} .A randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled, parallel-group analgesic efficacy trial of oral ARRY-371797 in subjects undergoing third molar extraction. CTG: NCT00663767. [Google Scholar]

- DIC2-08-03 {unpublished data only} .A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, single-dose, parallel-group, active- and placebo-controlled study of diclofenac [Test] capsules for the treatment of pain after surgical removal of impacted third molars. CTG: NCT00985439. [Google Scholar]

- IND2-08-03 {unpublished data only} .A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, single-dose, parallel-group, active- and placebo-controlled study of indomethacin test capsules for the treatment of pain after surgical removal of impacted third molars. CTG: NCT00964431. [Google Scholar]

- Shirota 2001 {published data only} .Shirota T, Ohno K-S, Michii K-I, Kamijo R, Nagumo M, Sato H, et al. A study of the dose-response of YM177 for treatment of postsurgical dental pain. Oral Therapeutics and Pharmacology. 2001;20(3):154–72. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

- Barden 2004 .Barden J, Edwards JE, McQuay HJ, Andrew Moore R. Pain and analgesic response after third molar extraction and other postsurgical pain. Pain. 2004;107(1-2):86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.09.021. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke 2012 .Clarke R, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oral etoricoxib for postoperative pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004309.pub2. Issue in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins 1997 .Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. The visual analogue pain intensity scale: what is moderate pain in millimetres? Pain. 1997;72:95–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins 2001 .Collins SL, Edwards J, Moore RA, Smith LA, McQuay HJ. Seeking a simple measure of analgesia for mega-trials: is a single global assessment good enough? Pain. 2001;91:189–94. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00435-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook 1995 .Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ. 1995;310:452–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper 1991 .Cooper SA. Single-dose analgesic studies: the upside and downside of assay sensitivity. In: Max MB, Portenoy RK, Laska EM, editors. The Design of Analgesic ClinicalTrials. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy. Vol. 18. Raven Press; New York: 1991. pp. 117–24. [Google Scholar]

- Derry 2011 .Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA. Relative efficacy of oral analgesics after third molar extraction - a 2011 update. British Dental Journal. 2011;211(9):419–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.905. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]