Abstract

Background:

Population-based estimates of HIV prevalence, rates of new HIV diagnoses, and mortality rates among persons with HIV who have entered care are needed to optimize health service delivery and to improve the health outcomes of these individuals. However, these data have been lacking for Ontario.

Methods:

Using a validated case-finding algorithm and linked administrative health care databases, we conducted a population-based study to determine the prevalence of HIV and rates of new HIV diagnoses among adults aged 18 years or older in Ontario between fiscal year 1996/1997 and fiscal year 2009/2010, as well as all-cause mortality rates among persons with HIV over the same period.

Results:

Between 1996/1997 and 2009/2010, the number of adults living with HIV increased by 98.6% (from 7608 to 15 107), and the age- and sex-standardized prevalence of HIV increased by 52.8% (from 92.8 to 141.8 per 100 000 population; p < 0.001). Women and individuals 50 years of age or older accounted for increasing proportions of persons with HIV, rising from 12.8% to 19.7% (p < 0.001) and from 10.4% to 29.9% (p < 0.001), respectively, over the study period. During the study period, age- and sex-standardized rates of new HIV diagnoses decreased by 32.5% (from 12.3 to 8.3 per 100 000 population; p < 0.001) and mortality rates among adults with HIV decreased by 71.9% (from 5.7 to 1.6 per 100 adults with HIV; p < 0.001).

Interpretation:

The prevalence of HIV infection in Ontario increased considerably between 1996/1997 and 2009/2010, with a greater relative burden falling on women and individuals aged 50 years of age or older. These trends may be due to the decreased rate of new diagnoses among younger men. All-cause mortality rates declined among persons with HIV who entered care.

The natural history of HIV infection has been irrefutably altered by the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy during the latter half of the 1990s.1,2 Most notably, between 1995 and 2009, an estimated 14.4 million life-years were gained globally among HIV-infected adults who received this form of therapy.3 In conjunction with this achievement, the epidemiology of HIV infection has changed markedly since the earliest years of the epidemic, such that greater demographic diversity among persons with a diagnosis of HIV has been described internationally.4,5 In this context, accurate population-based estimates of the incidence and prevalence of persons with HIV who are entering care are needed to optimize health service delivery and to improve the health outcomes of these individuals.

In Ontario, epidemiologic surveillance of HIV infection is conducted by the Ontario HIV Epidemiologic Monitoring Unit. This agency publishes annual surveillance reports characterizing trends in the epidemic based on data from various sources, including the public health laboratory system of Public Health Ontario, which performs almost all HIV diagnostic testing in the province.6 However, these data do not provide insight into the characteristics of individuals with HIV who have accessed the health care system. Consequently, existing methods of population-based HIV surveillance are not conducive to the study of longitudinal trends in rates of comorbid illness, entry to and retention in care, and demographic characteristics of persons with physician-diagnosed HIV. In contrast, administrative health care databases provide a means for conducting longitudinal population-based research of all persons living with HIV who have entered care. Although these databases have been used for the surveillance of various chronic diseases,7–11 there have been, to our knowledge, no studies describing the use of these databases to characterize trends in the epidemiology and outcomes of persons living with HIV within a large geographic region. Accordingly, we used administrative health care databases to assemble a population-based cohort of all adults with HIV who have entered care in Ontario and used these data to quantify trends in rates of HIV prevalence, new HIV diagnoses, and mortality among adults with HIV in Ontario from fiscal year 1996/1997 to fiscal year 2009/2010.

Methods

Data sources.

We obtained data from Ontario's administrative health care databases, which are available at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences through a data-sharing agreement with the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Specifically, we used the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) database to identify physician claims for HIV-related visits and obtained socio-demographic and date-of-death information from the Registered Persons Database, a registry of all Ontario residents eligible for health insurance. We used validated disease registries maintained by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences to identify comorbid conditions in persons with HIV.12–15 These databases, which are routinely used for population-based chronic disease surveillance,7–11 were linked in an anonymous fashion using encrypted health card numbers.

Study population.

We used a case-finding algorithm that had been validated with the charts of patients from 2 primary care clinics16 to generate a database of individuals in Ontario aged 18 years or older who were living with HIV and who had entered care between 1 April 1996, and 31 March 2010. Briefly, an algorithm based on a minimum of 3 physician claims with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision code for HIV infection (i.e., code 042, 043, or 044) within a 3-year period achieved sensitivity of 96.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] 95.2% to 97.9%) and specificity of 99.6% (95% CI 99.1% to 99.8%) for identification of patients who were regular users of primary care.16 We chose the end of fiscal year 2009/2010 as the end point for our analyses to meet the 3-year look-forward criterion of the algorithm. Because HIV is incurable, individuals who met the case definition for HIV infection remained part of the cohort throughout the study period, unless they died or moved out of the province of Ontario.

Outcomes.

The primary outcomes of the study were age- and sex-standardized prevalence of HIV infection and rates of new HIV diagnoses per 100 000 population of Ontario for each fiscal year between 1996/1997 and 2009/2010, and yearly all-cause mortality rate per 100 adults with HIV over the same period. We calculated these rates by direct standardization using the 1991 Ontario population as the reference population. We determined the annual prevalence of HIV infection by dividing the number of adults with HIV who had entered care and who were alive at the end of each fiscal year by the census population of Ontario aged 18 years and older for the corresponding year. We classified patients as being newly diagnosed according to the date on which they first entered care (i.e., the date of their first claim for an HIV-related visit) and calculated rates of new diagnoses of HIV infection by dividing the number of new diagnoses by the number of individuals aged 18 or older at risk for the disease that year (the total population minus the number of people with prevalent HIV in the previous year). To distinguish between a new diagnosis and a prevalent case, we required that individuals have no prior physician claims for HIVrelated visits in the 5 years preceding their diagnosis date. Individuals who had a claim during this window were counted as prevalent cases rather than new diagnoses. Because the OHIP database does not include claims before 1991, we chose to start reporting results with fiscal year 1996/1997 to allow for this 5-year lookback period. We estimated the annual rate of all-cause mortality among adults with HIV who had entered care by dividing the annual number of deaths among these individuals by the number of adults with HIV in each year. We report annual rates of all-cause mortality because information on disease-specific mortality was unavailable in our databases.

Statistical analysis.

We used negative binomial regression analysis to examine temporal trends in prevalence of HIV, rates of new HIV diagnoses, and mortality rates, using the population denominators as the offset. All models included year as the main predictor, along with variables for age group (18–34 years, 36–49 years, and ≥ 50 years) and sex. Because of statistically significant (p < 0.001) 3-way interactions between age group, sex, and year in all models, we stratified the regression analyses by age group and sex. Therefore, for each age– sex stratum, the following model was fit:

where exp(β0) is the outcome rate in the reference year (1996/1997) and 100 × [exp(β1) – 1] is the percent relative annual change in the outcome averaged over the 14-year study period.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS institute, Cary, NC).

Ethics approval.

We obtained ethics approval for this study from the Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Results

Between 1996/1997 and 2009/2010, the number of adults living with HIV infection increased by 98.6% (from 7608 to 15 107), which far outpaced the 23.3% relative increase in the adult population of Ontario during this period. Women accounted for an increasing proportion of all adults with HIV during the study period, from 12.8% in 1996/1997 to 19.7% in 2009/2010 (p < 0.001) (Table 1). Similarly, the proportion of persons with HIV who were 50 years of age or older increased from 10.4% to 29.9% over the study period (p < 0.001) (Table 1). In 2009/2010, the majority of people with HIV aged 50 years or older were men (3847 of 4520 [85.1%]). Women and individuals 50 years of age or older were also increasingly represented among those with new HIV diagnoses, increasing from 15.4% (153 of 994) to 24.7% (198 of 802) (p < 0.001) and from 10.7% (106 of 994) to 15.6% (125 of 802) (p = 0.002), respectively, between 1996/1997 and 2009/2010. The prevalence of selected comorbid conditions associated with aging also increased over time (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Ontario adults living with HIV who have entered care

| Characteristic | Fiscal year; no. (%) of individuals | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996/1997 n = 7 608 |

2002/2003 n = 10 850 |

2009/2010 n = 15 107 |

||

| Age, yr | < 0.001 | |||

| 18–35 | 3 713 (48.8) | 2 973 (27.4) | 2 695 (17.8) | |

| 36–49 | 3 101 (40.8) | 5 902 (54.4) | 7 892 (52.2) | |

| ≥ 50 | 794 (10.4) | 1 975 (18.2) | 4 520 (29.9) | |

| Sex | < 0.001 | |||

| Female | 971 (12.8) | 1 781 (16.4) | 2 974 (19.7) | |

| Male | 6 637 (87.2) | 9 069 (83.6) | 12 133 (80.3) | |

| Urban residence | 7 353 (96.6) | 10 401 (95.9) | 14 500 (96.0) | 0.02 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 213 (2.8) | 563 (5.2) | 1 313 (8.7) | < 0.001 |

| COPD | 293 (3.9) | 588 (5.4) | 1 171 (7.8) | < 0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 53 (0.7) | 133 (1.2) | 284 (1.9) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 456 (6.0) | 1 142 (10.5) | 2 398 (15.9) | < 0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 28 (0.4) | 96 (0.9) | 200 (1.3) | < 0.001 |

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Prevalence.

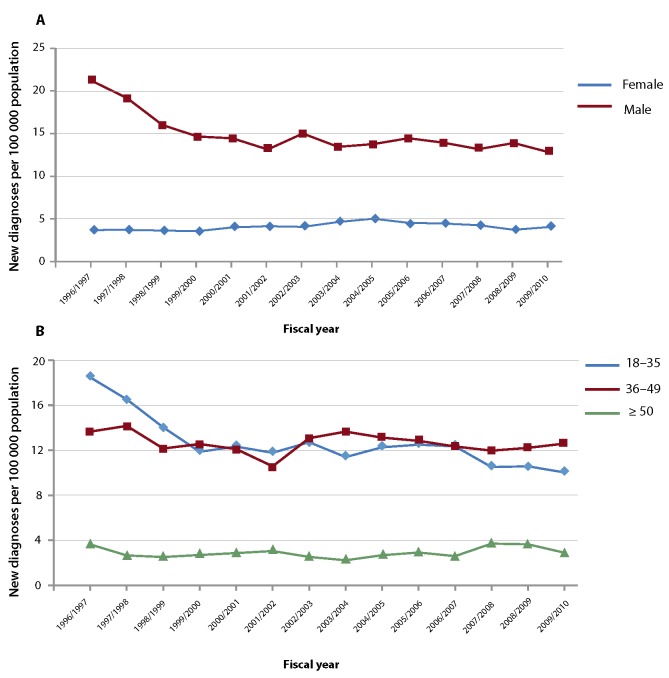

The age- and sex-standardized prevalence of HIV per 100 000 population increased from 92.8 (95% CI 90.7 to 94.9) in 1996/1997 to 141.8 (95% CI 139.5 to 144.1) in 2009/2010, a relative increase of 52.8% (p < 0.001) (Table 2). The age-standardized increase in HIV prevalence was greater among women than men (Figure 1A), and the sex-standardized prevalence increased with age (Figure 1B). The prevalence of HIV increased in all age strata of women over the study period, with the average increase ranging from 3.2% (95% CI 2.5% to 4.0%) per year among women aged 18 to 35 years to 11.3% (95% CI 10.4% to 12.2%) per year among women aged 50 years or older (Table 3). Among men aged 18 to 35 years, the prevalence of HIV decreased between 1996/1997 and 2009/2010, with a mean annual change of –5.3% (95% CI –6.0% to –4.7%). In contrast, the prevalence of HIV increased in the other age strata of men, the most notable change being observed for the group 50 years of age or older (10.6%, 95% CI 10.0% to 11.1%) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Age- and sex-standardized HIV prevalence, new diagnosis rate, and all-cause mortality rate among Ontario adults * who entered care, 1996/1997 to 2009/2010

| Fiscal year | Prevalence of HIV | New diagnoses of HIV | Deaths from any cause | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of adults living with HIV | Prevalence† per 100 000 population (95% CI) | No. of adults with new diagnosis | Rate† per 100 000 population (95% CI) | No. of deaths among adults with HIV | Mortality rate† per 100 adults with HIV (95% CI) | |

| 1996/1997 | 7 608 | 92.8 (90.7–94.9) | 994 | 12.3 (11.5–13.1) | 447 | 5.7 (4.6–6.9) |

| 1997/1998 | 8 079 | 97.1 (94.9–99.2) | 926 | 11.3 (10.6–12.1) | 244 | 4.4 (3.3–5.7) |

| 1998/1999 | 8 622 | 101.9 (99.8–104.1) | 803 | 9.7 (9.1–10.4) | 194 | 3.2 (2.3–4.4) |

| 1999/2000 | 9 193 | 106.4 (104.2–108.6) | 762 | 9.0 (8.4–9.7) | 224 | 2.8 (2.1–3.8) |

| 2000/2001 | 9 712 | 109.1 (106.9–111.3) | 781 | 9.1 (8.5–9.8) | 212 | 3.0 (2.2–4.0) |

| 2001/2002 | 10 228 | 111.2 (109.1–113.4) | 744 | 8.6 (7.9–9.2) | 189 | 2.6 (1.9–3.4) |

| 2002/2003 | 10 850 | 114.6 (112.5–116.8) | 836 | 9.4 (8.8–10.1) | 209 | 2.7 (2.0–3.6) |

| 2003/2004 | 11 439 | 118.1 (115.9–120.3) | 812 | 9.0 (8.3–9.6) | 182 | 2.5 (1.8–3.3) |

| 2004/2005 | 12 072 | 122.2 (120.0–124.4) | 848 | 9.3 (8.7–10.0) | 196 | 2.0 (1.5–2.6) |

| 2005/2006 | 12 702 | 126.3 (124.1–128.6) | 863 | 9.4 (8.8–10.0) | 209 | 1.9 (1.5–2.5) |

| 2006/2007 | 13 319 | 130.5 (128.3–132.8) | 838 | 9.1 (8.5–9.7) | 199 | 1.7 (1.3–2.1) |

| 2007/2008 | 13 893 | 134.0 (131.7–136.2) | 820 | 8.6 (8.0–9.2) | 210 | 1.9 (1.4–2.4) |

| 2008/2009 | 14 516 | 138.0 (135.8–140.3) | 835 | 8.7 (8.1–9.3) | 214 | 2.1 (1.7–2.7) |

| 2009/2010 | 15 107 | 141.8 (139.5–144.1) | 802 | 8.3 (7.8–8.9) | 228 | 1.6 (1.3–2.0) |

Age 18 years or older.

Age- and sex-standardized.

Figure 1.

Trends in HIV prevalence.

(A) Age-standardized trends, by sex.

(B) Sex-standardized trends, by age group.

Table 3.

Age- and sex-specific prevalence of adults with HIV who entered care in Ontario

| Sex and age | Fiscal year; crude prevalence per 100 000 population | % relative annual change (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996/1997 | 2002/2003 | 2009/2010 | ||

| Female | ||||

| 18–35 yr | 37.37 | 51.48 | 55.47 | 3.2 (2.5 to 4.0) |

| 36–49 yr | 23.69 | 52.65 | 99.53 | 11.0 (10.2 to 11.8) |

| ≥ 50 yr | 7.29 | 14.88 | 29.63 | 11.3 (10.4 to 12.2) |

| Male | ||||

| 18–35 yr | 205.09 | 144.12 | 112.38 | –5.3 (–6.0 to –4.7) |

| 36–49 yr | 234.60 | 369.97 | 455.75 | 5.2 (4.4 to 6.0) |

| ≥ 50 yr | 50.40 | 105.04 | 191.10 | 10.6 (10.0 to 11.1) |

CI = confidence interval.

New HIV diagnoses.

The age- and sex-standardized rate of new HIV diagnoses per 100 000 population declined from 12.3 (95% CI 11.5 to 13.1) in 1996/1997 to 8.3 (95% CI 7.8 to 8.9) in 2009/2010, a relative decrease of 32.5% (p < 0.001) (Table 2). However, despite this decline, the annual number of new HIV diagnoses was relatively stable between 2002/2003 and 2009/2010, ranging from 802 to 863 cases during this period. The agestandardized rate of new diagnoses decreased among men (Figure 2A), and overall sex-standardized rates declined in all age strata, most notably among individuals in the 18- to 35-year and 36- to 49-year strata (Figure 2B). In contrast to the situation for men, the annual rate of new HIV diagnoses increased among women 36 to 49 years of age (3.2%, 95% CI 1.0% to 5.4%) and those 50 years of age or older (5.0%, 95% CI 2.2% to 8.0%) (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Trends in rates of new diagnosis.

(A) Age-standardized trends, by sex.

(B) Sex-standardized trends, by age group.

Table 4.

Age- and sex-specific rates of new HIV diagnoses among adults who entered care in Ontario

| Sex and age | Fiscal year; crude rate of new diagnosis per 100 000 population | % relative annual change (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996/1997 | 2002/2003 | 2009/2010 | ||

| Female | ||||

| 18–35 yr | 6.47 | 6.95 | 5.48 | –0.3 (–2.0 to 1.5) |

| 36–49 yr | 2.78 | 3.43 | 5.22 | 3.2 (1.0 to 5.4) |

| ≥ 50 yr | 1.33 | 1.35 | 1.58 | 5.0 (2.2 to 8.0) |

| Male | ||||

| 18–35 yr | 30.17 | 18.32 | 14.44 | –4.3 (–5.8 to –2.8) |

| 36–49 yr | 24.45 | 22.63 | 19.90 | –1.1 (–2.0 to –0.2) |

| ≥ 50 yr | 6.31 | 3.89 | 4.42 | –0.3 (–2.4 to 1.7) |

CI = confidence interval.

All-cause mortality.

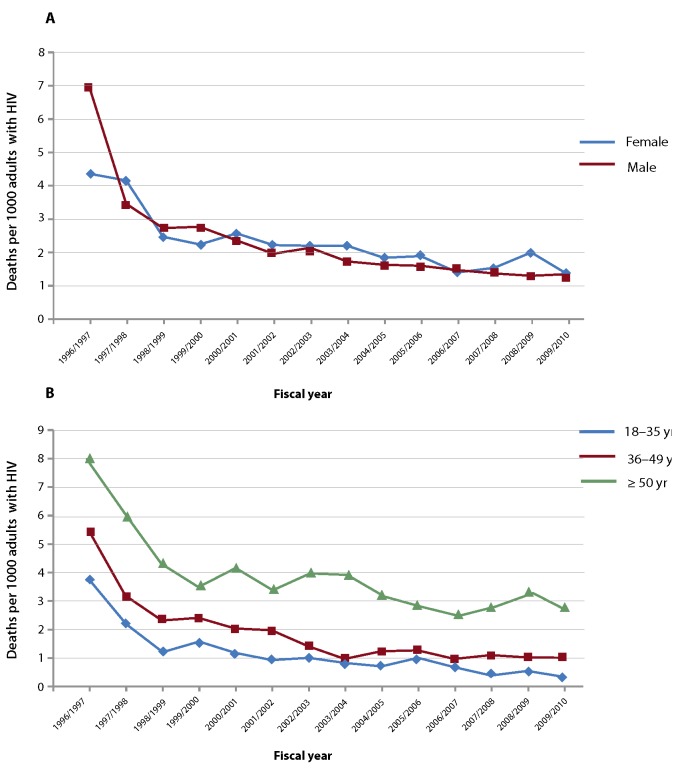

The overall age- and sex-standardized all-cause mortality rate per 100 adults with HIV declined from 5.7 (95% CI 4.6 to 6.9) in 1996/1997 to 1.6 (1.3 to 2.0) in 2009/2010, which represented a 71.9% relative decrease over this period (p < 0.001) (Table 2). All-cause mortality declined in all age strata of both men and women (Table 5, Figures 3A, 3B), although rates remained higher among individuals 50 years of age or older relative to younger people (Table 5, Figure 3B).

Table 5.

Age- and sex-specific all-cause mortality rates among adults living with HIV who entered care in Ontario

| Sex and age | Fiscal year; crude mortality rate per 100 adults with HIV | % relative annual change (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996/1997 | 2002/2003 | 2009/2010 | ||

| Female | ||||

| 18–35 yr | 3.18 | 0.65 | 0.22 | –14.2 (–18.6 to –9.5) |

| 36–49 yr | 3.79 | 1.63 | 1.42 | –7.7 (–10.9 to –4.3) |

| ≥ 50 yr | 6.09 | 4.35 | 2.53 | –4.7 (–8.4 to –0.8) |

| Male | ||||

| 18–35 yr | 4.26 | 1.36 | 0.44 | –13.8 (–17.0 to –10.6) |

| 36–49 yr | 7.40 | 1.74 | 1.19 | –10.6 (–13.4 to –7.8) |

| ≥ 50 yr | 10.16 | 3.55 | 2.70 | –7.9 (–10.2 to –5.5) |

CI = confidence interval.

Figure 3.

Trends in deaths of adults with HIV.

(A) Age-standardized trends, by sex.

(B) Sex-standardized trends, by age group.

Interpretation

In our population-based study, the number of adults with HIV increased by 98.6% between 1996/1997 and 2009/2010. This increase is most likely attributable to the striking reduction in all-cause mortality rates observed among these individuals during this period and the essentially stable number of new HIV diagnoses in the last decade of the period. Importantly, however, women and adults aged 50 years or older accounted for increasing proportions of new HIV diagnoses over the study period. Finally, we observed a steady increase in the prevalence of selected comorbid conditions among adults with HIV who had entered care, which reflects the transformation of HIV infection into a complex chronic disease affecting an aging cohort of patients expected to be increasingly burdened by multiple coexisting illnesses.

Our findings have important implications for HIV prevention and public health. The data suggest that the increased relative burden of HIV among women and older individuals may be mostly due to the decreased rate of new diagnoses among younger men, which perhaps reflects the differential emphasis or success of HIV prevention efforts. Older adults in particular have not been routinely targeted by public health interventions to prevent HIV infection, despite a general lack of knowledge about the disease, as well as evidence of HIV risk behaviour, among these individuals.17–19 In addition, the absolute number of new HIV diagnoses remained relatively stable in Ontario over the last decade of the study period. Rates of new HIV infections in British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec have been shown to decline 8% for each 10% increment in coverage for antiretroviral treatment,20 so universal coverage for these drugs might be useful to augment existing prevention programs in Ontario. Finally, the Ontario HIV Epidemiologic Monitoring Unit estimated that 27 420 Ontarians had had a positive test result for HIV and were alive as of 2009, of whom 17 818 were estimated to be aware of their diagnosis and could therefore presumably generate physician claims for HIV-related visits that would be captured in administrative health care databases.6 These estimates were based on epidemiologic models derived using data from sources different from the ones used for the current study, including the Public Health Laboratory and the Ontario Registrar General. Using administrative health care databases, we identified 15 107 individuals who met our case-finding definition for HIV infection and who were alive as of fiscal year 2009/2010. Although both approaches to estimating the burden of HIV infection in Ontario have their respective merits and limitations, a key interpretation of both data sets is that a significant proportion of individuals with HIV appear to be unaware of their infection or appear not to be retained in care once a diagnosis has been made and hence did not generate enough claims to be detected by our algorithm. Because these individuals may unknowingly contribute to the annual incidence of new infections and are unable to benefit from HIV-specific care, innovative interventions are required to increase the proportion of persons infected with HIV whose condition is diagnosed and who are retained in care.21

Our work had several limitations that merit emphasis. First, administrative health care databases can identify only individuals with physician-diagnosed HIV who are in care; they will not capture people with HIV who are unaware of their diagnosis or individuals who are aware of their diagnosis but have not entered care. Furthermore, we could not identify individuals who obtained care from physicians who do not bill OHIP and/ or were ineligible for provincial public health insurance (e.g., refugee claimants). Our findings therefore underestimate the true incidence and prevalence of HIV in Ontario. In addition, we had no access to patients' clinical data or information regarding method of HIV acquisition, which rendered it impossible to examine epidemiologic trends in relation to risk factors for HIV infection, stage of illness at the time of diagnosis, or country of birth. However, these limitations are common to all studies that use administrative data for chronic disease surveillance and must be balanced against the strengths of using these data for this purpose, including the identification of all patients who are in care within a geographically large jurisdiction, complete follow-up of these patients over time, and the potential for linkage with other health care data sets.12–15 Finally, the potential for misclassification is always a consideration when using administrative data for health services research. To address this concern, we assembled our cohort using a validated algorithm with excellent test characteristics for discriminating between HIV-infected and non-infected individuals.16 To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study using a validated case-finding algorithm and administrative data to examine trends in the epidemiology of persons with HIV who have entered care.

In summary, we assembled a population-based cohort of adults with HIV who had entered care and then examined trends in HIV prevalence, new HIV diagnoses, and mortality over a 14-year period. Our findings suggest that if current trends continue, it will be necessary to adapt HIV-related health and support services to the needs of an aging cohort of patients with multiple comorbidities who may inevitably require the expertise of sectors of the health care system that have not traditionally been involved in the provision of HIVrelated care, such as gerontology and long-term care. In addition, a large proportion of HIV-infected persons in Ontario are not receiving HIV-related care. Future research examining patterns of and disparities in health services utilization, entry to and retention in care, and trends in the prevalence of comorbid conditions will be required to ensure that HIV-related services continue to evolve in a manner that anticipates the needs of the growing population of persons with HIV.

Footnotes

During the past 3 years, Tony Antoniou has received unrestricted research grants from Merck for studies other than the one reported here, and Mona Loutfy has received grants from Abbott Laboratories, Merck Frosst Canada Ltd., Pfizer, and ViiV Healthcare. None declared by Brandon Zagorski, Ahmed M. Bayoumi, Carol Strike, Janet Raboud, or Richard H. Glazier.

This project was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The sponsors had no role in the design or conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding source. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Tony Antoniou is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Ontario HIV Treatment Network. Ahmed M. Bayoumi is supported by a Canadian Institutes for Health Research/ Ontario MOHLTC Applied Chair in Health Services and Policy Research. Mona Loutfy is the recipient of salary support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Janet Raboud is supported by an Ontario HIV Treatment Network Career Scientist Award and the Skate the Dream Fund, Toronto General and Western Hospital Foundation.

Contributor Information

Tony Antoniou, Tony Antoniou, PhD, is a Research Scholar in the Department of Family and Community Medicine and a Scientist in the Keenan Research Centre of the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Family and Community Medicine and the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario..

Brandon Zagorski, Brandon Zagorski, MSc, is an Adjunct Professor in the Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario. At the time of this study, he was also an Analyst with the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Toronto, Ontario..

Ahmed M Bayoumi, Ahmed M. Bayoumi is a Scientist in the Keenan Research Centre of the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute and Centre for Research on Inner City Health, St. Michael's Hospital, and an Associate Professor in the Department of Medicine and the Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario..

Mona R Loutfy, Mona R. Loutfy, MD, MPH, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, and a Scientist at the Women's College Hospital Research Institute, Toronto, Ontario..

Carol Strike, Carol Strike, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, and an Affiliate Scientist in the Health Systems and Health Equity Research Group, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Ontario..

Janet Raboud, Janet Raboud, PhD, is an Affiliate Scientist at the Toronto General Research Institute and an Associate Professor in the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario..

Richard H Glazier, Richard H. Glazier, MD, MPH, is a Professor and Clinician Scientist in the Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto and St. Michael's Hospital, a Senior Scientist at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, and a Scientist in the Keenan Research Centre of the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute and Centre for Research on Inner City Health, St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto, Ontario..

References

- 1.Hogg RS, Yip B, Kully C, Craib KJP, O'Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT, et al. Improved survival among HIV-infected patients after initiation of triple-drug antiretroviral regimens. CMAJ. 1999;160(5):659–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mocroft A, Vella S, Benfield TL, Chiesi A, Miller V, Gargalianos P, et al. Changing patterns of mortality across Europe in patients infected with HIV-1. Euro-SIDA Study Group. Lancet. Lancet;352(9142):1725–1730. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahy M, Stover J, Stanecki K, Stoneburner R, Tassie JM. Estimating the impact of antiretroviral therapy: regional and global estimates of life-years gained among adults. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(Suppl 2):ii67–ii71. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.046060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Health Protection Agency , author. HIV in the United Kingdom: 2011 report. London (UK): Health Protection Services; 2011. Nov, Available from: www.hpa.org.uk/webc/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1317131685847 (accessed 2013 Feb 1). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenton KA. Changing epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in the United States: implications for enhancing and promoting HIV testing strategies. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(Suppl 4):S213–S220. doi: 10.1086/522615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Remis RS, Swantee C, Liu J. Report on HIV/AIDS in Ontario 2009. Toronto (ON): Ontario HIV Epidemiologic Monitoring Unit; 2012. Jun, Available from: www.ohemu.utoronto.ca/tech%20reports.html (accessed 2013 Jan 31). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tu K, Chen Z, Lipscombe L. Canadian Hypertension Education Program Outcomes Research Taskforce. Prevalence and incidence of hypertension from 1995 to 2005: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2008;178(11):1429–1435. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tu K, Chen Z, Lipscombe L. Canadian Hypertension Education Program Outcomes Research Taskforce. Mortality among patients with hypertension from 1995 to 2005: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2008;178(11):1436–1440. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeung DF, Boom NK, Guo H, Lee DS, Schultz SE, Tu JV. Trends in the incidence and outcomes of heart failure in Ontario, Canada: 1997 to 2007. CMAJ. 2012;184(14):E765–E773. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipscombe LL, Hux JE. Trends in diabetes prevalence, incidence, and mortality in Ontario, Canada 1995�2005: a population-based study. Lancet. 2007;369(9563):750–756. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gershon AS, Wang C, Wilton AS, Raut R, To T. Trends in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevalence, incidence, and mortality in Ontario, Canada, 1996 to 2007: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(6):560–565. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tu K, Campbell NR, Chen ZL, Cauch-Dudek KJ, McAlister FA. Accuracy of administrative databases in identifying patients with hypertension. Open Med. 2007;1(1):e18–e26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V, Bica A. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(3):512–516. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Cicutto L, To T. Identifying patients with physician-diagnosed asthma in health administrative databases. Can Respir J. 2009;16(6):183–188. doi: 10.1155/2009/963098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Cicutto L, To T. Identifying individuals with physician diagnosed COPD in health administrative databases. COPD. 2009;6(5):388–394. doi: 10.1080/15412550903140865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antoniou T, Zagorski B, Loutfy MR, Strike C, Glazier RH. Validation of case-finding algorithms derived from administrative data for identifying adults living with human immunodeficiency virus infection. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21748–e21748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson SJ, Bernstein LB, George DM, Doyle JP, Paranjape AS, Corbie-Smith G. Older women and HIV: how much do they know and where are they getting their information? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(9):1549–1553. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooperman NA, Arnsten JH, Klein RS. Current sexual activity and risky sexual behavior in older men with or at risk for HIV infection. AIDS Educ Prev. 2007;19(4):321–333. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.4.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orel NA, Wright JM, Wagner J. Scarcity of HIV/AIDS risk-reduction materials targeting the needs of older adults among state departments of public health. Gerontologist. 2004;44(5):693–696. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.5.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogg RS, Heath K, Lima VD, Nosyk B, Kanters S, Wood E, et al. Disparities in the burden of HIV/AIDS in Canada. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e47260–e47260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders GD, Bayoumi AM, Sundaram V, Bilir SP, Neukermans CP, Rydzak CE, et al. Cost-effectiveness of screening for HIV in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):570–585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa042657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]