Abstract

Mental clouding is an almost universal complaint among patients with postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS), but remains poorly understood. Thus, we determined whether POTS patients exhibit deficits during neuropsychological testing relative to healthy subjects. A comprehensive battery of validated neuropsychological tests was administered to 28 female POTS patients and 24 healthy subjects in a semi-recumbent position. Healthy subjects were matched to POTS patients on age and gender. Selective attention, a primary outcome measure, and cognitive processing speed were reduced in POTS patients compared to healthy subjects (Ruff 2&7 Speed t-score: 40±9 vs. 49±8; p=0.009; Symbol Digit Modalities Test t-score: 45±12 vs. 51±8; p=0.011). Measures of executive function were also lower in POTS patients (Trails B t-score: 46±8 vs. 52±8; p=0.007; Stroop Word Color t-score: 45±10 vs. 56±8; p=0.001) suggesting difficulties in tracking and mental flexibility. Measures of sustained attention, psychomotor speed, memory function or verbal fluency were not significantly different between groups. This study provides evidence for deficits in selective attention and cognitive processing in patients with POTS, in the seated position when orthostatic stress is minimized. In contrast, other measures of cognitive function including memory assessments were not impaired in these patients, suggesting selectivity in these deficits. These findings provide new insight into the profile of cognitive dysfunction in POTS, and provide the basis for further studies to identify clinical strategies to better manage the mental clouding associated with this condition.

Keywords: orthostatic intolerance, postural tachycardia syndrome, autonomic diseases, cognition, neuropsychological tests

Introduction

Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is one of the most frequent forms of chronic orthostatic intolerance. This heterogeneous disorder is a common source of disability among young adults, with a strong predilection for premenopausal females [1;2]. POTS is characterized by a sustained exaggerated heart rate (HR) increase within 10 minutes of standing, in the absence of orthostatic hypotension, and associated orthostatic symptoms that are relieved by recumbence [3]. Common orthostatic symptoms include palpitations, lightheadedness, blurred vision, nausea and fatigue. In addition, POTS patients commonly experience mental clouding even while lying down or seated, which poses significant limitations to daily activities [4;5].

Although cognitive impairment is an almost universal complaint among POTS patients, this phenomenon remains poorly understood. Our group previously showed that POTS patients exhibit mild to moderate depression and anxiety symptoms as well as significant self-rated inattention, all of which could negatively impact cognition [6]. These patients did not have an increased prevalence of major depression or anxiety disorders compared to the general population, however, and measures of cognitive function were not assessed. More recently, studies have shown that orthostatic stress produced by head-up tilt worsens measures of working memory in POTS patients with comorbid chronic fatigue syndrome [7;8]. While these findings provide some evidence for potential mechanisms underlying cognitive impairment in POTS, the precise nature of these deficits has not been described. Thus, the aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that POTS patients exhibit deficits in cognitive function during standardized neuropsychological testing relative to healthy subjects, to provide the first detailed neuropsychological characterization of these patients.

Methods

Study Participants

This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association, approved by the Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board, and registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01366963). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. We enrolled 30 female POTS patients consecutively admitted to the Vanderbilt Autonomic Dysfunction Center between February 2011 and July 2012. Screening included a comprehensive medical history, physical examination, orthostatic stress testing, 12-lead ECG and routine laboratory tests. Patients were diagnosed with POTS if all of the following criteria were met: (a) sustained HR increase ≥ 30 bpm or HR level ≥ 120 bpm within 10 minutes of standing or head-up tilt; (b) absence of orthostatic hypotension; (c) at least a 6-month history of self-reported daily orthostatic symptoms; and (d) absence of medications or other medical conditions predisposing to tachycardia such as acute dehydration.

For comparison, we enrolled 30 healthy subjects matched for age and gender to POTS patients. Healthy subjects were recruited by advertising in the Vanderbilt community and through the ResearchMatch.org volunteer registry. A screening with medical history was performed to document absence of significant medical problems. Healthy subjects were free of current or lifetime history of psychiatric disorders, were not taking psychotropic medications or medications that might predispose to tachycardia, and did not meet criteria for POTS. All subjects were at least 18 years of age and were non-smokers and non-pregnant. Subjects with evidence of systemic illness, hematologic disease, liver or renal abnormalities, or diseases that might predispose to tachycardia were excluded.

General Protocol

POTS patients were admitted to the Vanderbilt Clinical Research Center and placed on a low monoamine, methylxanthine-free, fixed sodium (150 mEq/day) and potassium (60–80 mEq/day) diet. Psychotropic drugs and medications affecting the autonomic nervous system, blood pressure or volume were discontinued for ≥5 half-lives before admission. Healthy subjects were studied on an outpatient basis and did not consume methylxanthine-containing products or medications the morning of the study.

Study Design

All subjects completed a comprehensive battery of validated neuropsychological tests. Cognitive testing was performed in the morning, at least two hours after breakfast, and in a quiet thermo-neutral room. Subjects were studied while seated at a 45° angle, a clinically relevant and well-tolerated position, to minimize orthostatic heart rate changes. After a 15-minute acclimation period, cognitive tests were administered in the same order to all subjects by the same trained research investigators (ACA and EMG). At the end of the study, demographic information was collected and subjects were asked to complete self-assessment surveys for depression, anxiety, and cognitive symptoms. Since race can influence results of cognitive testing, subjects were also asked during this period to self-report race based on NIH-defined categories. The total study period lasted less than two hours.

Cognitive Tests

As shown in Table 1, neuropsychological testing consisted of measures of estimated intelligence (Wechsler Test of Adult Reading, WTAR),[9] selective and sustained attention (Ruff 2&7),[10] psychomotor speed (Trails A),[11] cognitive processing speed (Symbol Digits Modalities Test, SDMT),[12] memory function (Randt Memory Test),[13] verbal fluency (Controlled Oral Word Association, COWA),[14] and executive function (Trails B and Stroop Word Color) [11;15]. Self-assessment surveys included: (a) depression symptoms (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: CES-D) [16]; (b) anxiety symptoms (Cognitive-Somatic Anxiety Questionnaire) [17]; and (c) subjective cognitive difficulties (Subjective Cognitive Impairment Scale: SCIS) [18]. These tools have shown good reliability and reproducibility in prior clinical studies, as described in the supplemental methods.

Table 1.

Outcome Measures in Neuropsychological Test Battery

| Neuropsychological Test | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Wechsler Test of Adult Reading | Estimated intelligence (IQ) |

| Ruff 2&7 Speed | Selective Attention |

| Ruff 2&7 Accuracy | Sustained Attention |

| Trails A | Psychomotor Speed |

| Trails B | Executive Function |

| Symbol Digits Modalities Test | Cognitive Processing Speed |

| Stroop Word Color | Executive Function |

| Randt, Short Story | Semantic Memory |

| Randt, Paired Words | Associative Memory |

| Randt, Repeating Numbers | Working Memory |

| Controlled Oral Word Association | Verbal Fluency |

Hemodynamic Measures

Seated blood pressure was measured immediately prior to cognitive testing using an automated sphygmomanometer cuff (Vital-Guard 450C, Ivy Biomedical, Branford, CT). HR was measured by continuous ECG.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 22.0, IBM Corp) and STATA (version 12.0, StataCorp LP) software. A two-tailed p value <0.05 was defined as statistically significant. The objective of this study was to test the null hypothesis that seated cognitive function is not different between POTS patients and healthy subjects. Given our previous finding for inattention in POTS,[6] our a priori primary outcome was selected as the Ruff 2&7 measures of selective attention and sustained attention. Secondary outcomes included measures of executive function, cognitive processing speed, psychomotor speed, memory and verbal fluency. When specified in scoring guidelines for individual tests, raw scores were converted to t-scores based on population norms for age, gender and education level. Clinical characteristics and comparisons of cognitive outcomes between groups were assessed using Mann Whitney U nonparametric analysis. Comparisons of clinical characteristics within groups were assessed using Wilcoxon signed-rank nonparametric paired analysis. The proportion of subjects achieving below a certain threshold for a given cognitive test (based on being below the mean score of a defined SD) was compared between groups using chi-square analysis. To determine whether psychiatric symptoms confounded results of cognitive testing, a general linear model was used with significant cognitive test scores defined as the dependent measure and depression and anxiety symptom scores included as a fixed factor.

Sample Size

A blinded sample size calculation was performed from preliminary data obtained on selective attention (Ruff 2&7 speed score) in the first 5 POTS patients and 5 healthy subjects enrolled. These data showed a mean difference of 7 in t-scores between groups, and a within group SD of 9. Based on these data, we estimated that 27 patients per group would have 80% power to detect a significant difference between groups. We conservatively anticipated 10% dropout for these studies, and thus enrolled 30 patients per group. Sample size calculations assumed an alpha level of 0.05 and were performed using independent t-test analysis (PS Software, Version 3.0.34) [19].

Results

Clinical Characteristics

Following enrollment, two POTS patients were excluded from analysis due to incomplete data sets. One healthy subject declined to participate after enrollment, and five enrolled healthy subjects were excluded due to use of psychotropic medications or psychiatric conditions that were initially undisclosed. Thus, the final analysis included data from 28 POTS patients and 24 healthy subjects. POTS patients and healthy subjects did not differ significantly in gender, age, body mass index, or race (Table 2). While there was no difference in estimated intelligence between groups, education level was significantly lower in POTS patients (p=0.007). There were no differences in seated blood pressure between POTS patients and healthy subjects immediately prior to cognitive testing (Table 2); however, seated HR was modestly higher in POTS patients (Table 2; 78±11 bpm vs. 69 ± 9 bpm; p=0.013).

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants

| Parameter, unit | Healthy | POTS | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Duration, years | 2.2 ± 1.9 | ||

| Age, years | 30 ± 6 | 31 ± 9 | 0.85 |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 22 ± 3 | 22 ± 3 | 0.60 |

| Race, Caucasian [n (%)] | 22 (92%) | 27 (96%) | 0.20 |

| Education Level, years | 18 ± 2 | 16 ± 3 | 0.007* |

| Estimated Intelligence (IQ) score | 112 ± 5 | 110 ± 7 | 0.24 |

| Seated Vitals | |||

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mm Hg | 101 ± 7 | 100 ± 11 | 0.54 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, mm Hg | 64 ± 8 | 64 ± 8 | 0.80 |

| Heart Rate, bpm | 69 ± 9 | 78 ± 11 | 0.01* |

Data represent mean ± SD. Vital signs were obtained after a 15-minute acclimation period with subjects seated at a 45° angle. POTS, Postural Tachycardia Syndrome; IQ, intelligence quotient. P value is comparison for each outcome between healthy subjects and POTS patients, with

representing p<0.05.

Neuropsychological Testing

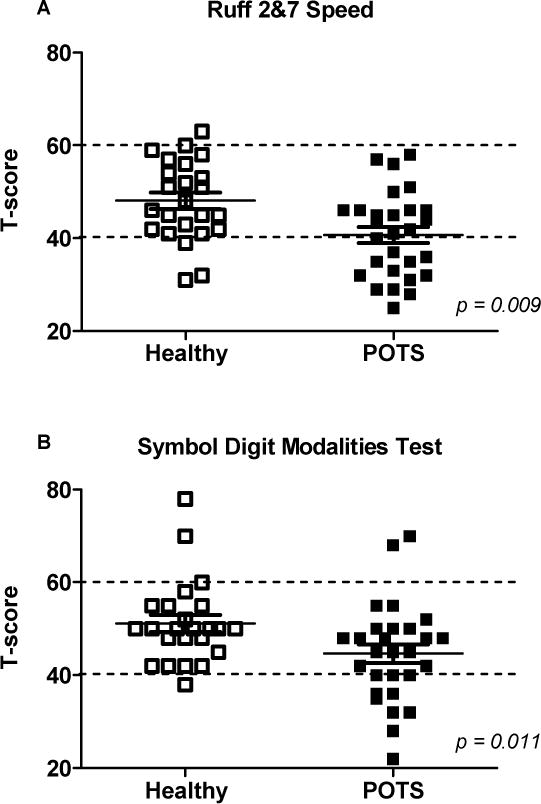

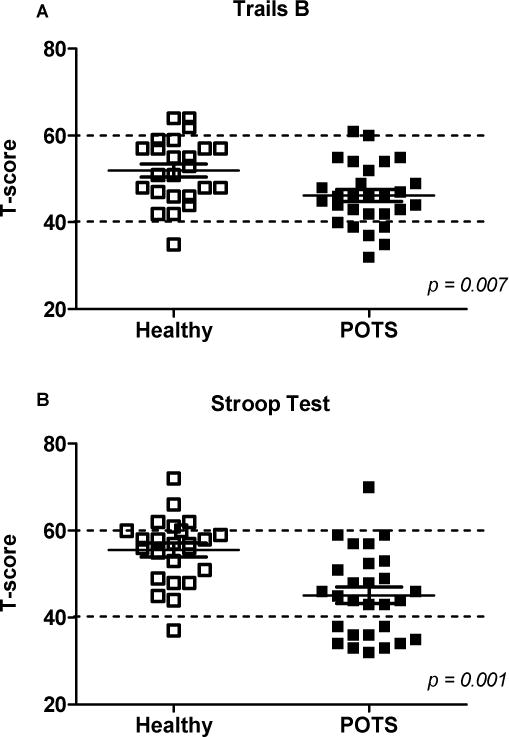

Selective attention was significantly reduced in POTS patients compared with healthy subjects (Table 3; Ruff 2&7 Speed t-score; p=0.009; Figure 1A). Cognitive processing speed (SDMT t-score; p=0.011; Figure 1B) and executive function (Trails B and Stroop Word Color t-scores; p=0.007 and 0.001, respectively; Figure 2) were also reduced in POTS. For selective attention, a higher proportion of POTS patients scored more than 2 SD below the mean, suggesting clinically meaningful impairment (4 POTS vs. 0 Healthy; p= 0.042; Figure 1A). In addition, a higher proportion of POTS patients scored more than 1.5 SD below the mean on the SDMT (6 POTS vs. 0 Healthy; p=0.011; Figure 1B) and Stroop Word Color (6 POTS vs. 0 Healthy; p=0.011; Figure 2B) tests, suggesting mild impairment of cognitive processing speed and executive function, respectively. As shown in Table 3, measures of sustained attention (Ruff 2&7 Accuracy), psychomotor speed (Trails A), memory function (Randt) and verbal fluency (COWA) did not differ between groups.

Table 3.

Seated Measures of Cognitive Function

| Neuropsychological Test, unit | Healthy | POTS | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ruff 2&7 Speed, t-score | 48 ± 9 | 41 ± 9 | 0.009* |

| Ruff 2&7 Accuracy, t-score | 52 ± 4 | 52 ± 6 | 0.96 |

| Trails A, t-score | 48 ± 11 | 45 ± 10 | 0.53 |

| Trails B, t-score | 52 ± 8 | 46 ± 7 | 0.007* |

| SDMT, t-score | 51 ± 9 | 45 ± 11 | 0.01* |

| Stroop Word Color, t-score | 56 ± 8 | 45 ± 10 | 0.001* |

| Randt Short Story Immediate, number correct | 11 ± 2 | 10 ± 3 | 0.20 |

| Randt Short Story Recall, number correct | 10 ± 3 | 9 ± 3 | 0.13 |

| Randt Paired Words Immediate, number correct | 5 ± 1 | 5 ± 1 | 0.18 |

| Randt Paired Words Recall, number correct | 5 ± 1 | 5 ± 1 | 0.20 |

| Randt Repeating Numbers Forward, number correct | 10 ± 2 | 9 ± 3 | 0.16 |

| Randt Repeating Numbers Backwards, number correct | 7 ± 3 | 7 ± 3 | 0.78 |

| COWA Letters, t-score | 43 ± 9 | 41 ± 14 | 0.70 |

| COWA Category, t-score | 36 ± 9 | 32 ± 14 | 0.38 |

Data represent mean ± SD. SDMT, Symbol Digits Modalities Test; COWA, controlled oral word association. P value is comparison for each outcome between healthy subjects and POTS patients, with

representing p<0.05.

Figure 1. Selective attention and cognitive processing speed are impaired in seated POTS patients.

A, The Ruff 2&7 Speed measure of selective attention was significantly reduced in POTS patients compared to healthy subjects. B, The Symbol Digit Modalities measure of cognitive processing speed was also significantly lower in POTS. Values represent mean ± SD of t-scores normalized for age, gender and education. Dotted lines represent ±1 SD of mean.

Figure 2. Measures of executive function are reduced in seated POTS patients.

The Trails B (A) and Stroop Word Color (B) measures of executive function were significantly reduced in POTS patients compared to healthy subjects. Values represent mean ± SD of t-scores normalized for age, gender and education. Dotted lines represent ±1 SD of mean.

Self-Assessment Surveys

POTS patients scored higher on the CES-D depression survey compared with healthy subjects (17±10 vs. 5±4; p=0.001), suggesting mild to moderate depression symptoms. Cognitive anxiety symptom scores did not significantly differ between groups (15±5 vs. 12±5; p=0.071), but somatic anxiety symptom scores were higher in POTS patients (17±5 vs. 12±4; p=0.001). The overall SCIS survey score was lower in POTS patients (29±7 vs. 36±3, p<0.05), suggesting broad self-perceived cognitive difficulties.

Neuropsychological Testing adjusted for Depression and Anxiety Symptoms

The potential contribution of psychiatric symptoms to cognitive impairment was assessed using a general linear model. With selective attention defined as the dependent variable, there was not a significant main effect of anxiety symptoms (p=0.416), although a trend for depression symptoms was evident (p=0.069). Even after adjustment for depression and anxiety symptoms, patient group remained the significant driver of this score (p=0.001). For executive function, there was no significant effect of depression (Trails B, p=0.668; Stroop Word Color, p=0.870) or anxiety symptoms (Trails B, p=0.883; Stroop Word Color, p=0.383). After adjustment, the patient group effect remained significant (Trails B, p=0.017; Stroop Word Color, p=0.001). For cognitive processing speed, there was no significant effect of depression (p=0.801) or anxiety symptoms (p=0.563). After adjustment the patient group effect was no longer significant (p=0.063), although a trend was apparent.

Discussion

The primary findings of this study are that seated POTS patients exhibit: (1) impaired selective, but not sustained, attention; (2) impaired cognitive processing speed and executive function; and (3) no differences in measures of psychomotor speed, memory function, or verbal fluency. These findings provide evidence for selective cognitive deficits in POTS patients, even when orthostatic tachycardia is minimized.

Cognitive Dysfunction in POTS

Deficits in attention are commonly observed in disease states, and we previously reported significant inattention in POTS [6]. Consistent with this finding, we observed impairment of selective attention and cognitive processing speed in POTS patients. Sustained attention was intact suggesting an ability to maintain responses during continuous activity. The deficit in selective attention, however, suggests that these patients struggle with appropriately focusing on competing cues and processing this information. Executive function was also impaired in POTS suggesting a diminished ability to shift cognitive strategies in response to changes in environmental cues, which can impair the ability to plan, organize and adapt [20]. Importantly, impairments in executive function measures, including the Trails B test, have been associated with functional disability and mortality in clinical populations [21–23].

The average cognitive test scores were within normal limits, but a significantly higher proportion of POTS patients scored in ranges consistent with clinically meaningful impairment for selective attention and executive function. The overlap in scores between POTS patients and healthy subjects likely reflects the heterogeneous origins of POTS. Selectivity in cognitive deficits, as observed in POTS patients, has been reported in neurogenic orthostatic hypotension [24] and in elderly patients with orthostatic hypotension [25]. The pattern of cognitive dysfunction in POTS differs from chronic fatigue syndrome and other conditions of orthostatic intolerance, in which deficits in memory function and concentration are often observed [26–29]. This suggests some disease specificity, but we are not able to differentiate whether these cognitive deficits are specific to POTS or reflect more general chronic illness.

Of interest, cognitive deficits were observed in seated POTS patients, and not just in the presence of orthostatic tachycardia. It has been shown, however, that HR is still modestly elevated by approximately 10 bpm in POTS patients even in the supine or seated positions [30;31]. Seated cognitive impairment has also been reported in autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy [28] and in elderly patients with symptomatic orthostatic hypotension [25;32]. In this initial study we chose to study patients in the seated position for several reasons. First, since there is no information on the pattern of cognitive deficits in POTS, we wanted to administer a comprehensive battery of neuropsychological tests which required at least 30 minutes for completion. Most POTS patients would not have tolerated standing for this length of time. Second, many of our patients report cognitive difficulties while seated in their work environment and thus we wanted to study this clinically relevant position. Finally, these conditions allowed us to assess cognitive deficits independent of the excessive orthostatic tachycardia with standing. It is possible that cognitive function would be substantially worse in POTS patients under conditions of increased orthostatic stress. For example, there was no impairment in working memory in POTS patients with comorbid chronic fatigue syndrome when studied in the supine position, but impairments became evident following graded head-up tilt [8]. Regardless, the present results suggest that cognitive impairment does not arise solely from hemodynamic changes in POTS, but may result from underlying disease pathophysiology.

Finally, while estimated intelligence was similar between groups, POTS patients were less educated compared to controls (although on average they achieved 16 years of education). It is probable that POTS symptoms impact daily functioning and ability to work thus interfering with educational and occupational attainment, particularly in settings requiring significant activity or standing. The impact of POTS on these aspects of quality of life has not been systematically assessed. Alternatively, our control group may have been more highly educated than the general population, due to partial recruitment from a university setting. The observed difference in educational level is unlikely to impact our interpretation as standardized psychometric tools were used with scores adjusted for education level, age, and gender.

Subjective Depression and Anxiety Symptoms and Cognitive Difficulties

The presence of psychiatric symptoms can negatively impact cognitive function. POTS patients exhibit mild depression and anxiety as well as somatic panic-like symptoms that are distinct from panic disorder [33–35]. In addition, POTS is associated with mild to moderate depression and anxiety symptoms, without an increased prevalence of major depression or anxiety disorders [6]. Psychiatric symptoms were assessed in this study to determine if cognitive deficits were due solely to elevated psychopathology in POTS. Similar to our previous study,[6] we observed mild depression symptoms and a selective elevation in somatic anxiety symptoms in POTS, which is believed to reflect a contribution of biological (e.g. tachycardia and palpitations) rather than psychological factors to the clinically observed anxiety in these patients.

Cognitive deficits were still observed in POTS patients after adjustment for psychiatric symptoms, suggesting that cognitive dysfunction is independent of depression and anxiety. Patients with chronic fatigue syndrome also exhibit cognitive deficits that are not explained by comorbid depressive disorders or symptoms [29]. It is noteworthy that POTS patients scored worse on every domain when asked to self-assess their cognitive impairment, with scores similar to levels reported for patients with depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder [18]. Our finding for broad self-perceived cognitive impairment in POTS contrasts with the selective impairment observed with objective neuropsychological testing. This may reflect more critical self-rating of symptoms, as well as increased patient recall of cognitive difficulties during prior periods of greater orthostatic stress.

Potential Pathophysiological Mechanisms for Cognitive Dysfunction in POTS

While not explored in this study, several pathophysiological mechanisms could contribute to cognitive dysfunction in POTS. First, there is an established association between central norepinephrine dysregulation and psychiatric conditions [35;36]. Centrally acting norepinephrine transporter inhibitors improve attention and working memory, but can recapitulate clinical features of POTS [37;38]. Conversely, high levels of catecholamines disrupt cognitive function. In this study, half of POTS patients exhibited a hyperadrenergic phenotype, defined as standing norepinephrine levels ≥600 pg/ml. There was no association, however, between norepinephrine levels and individual cognitive measures in POTS patients suggesting that noradrenergic dysregulation does not play a major role in cognitive dysfunction. Second, studies have reported that POTS is associated with impaired cerebral perfusion in response to orthostatic stress [7;39]. However, Ocon et al. showed that reductions in working memory in response to graded head-up tilt were not associated with altered cerebral blood flow in POTS patients with comorbid chronic fatigue syndrome [7]. Taken together with the present finding for seated cognitive dysfunction, these studies suggest an uncoupling of mental clouding from peripheral and cerebral hemodynamic regulation in this condition. Third, while not assessed in this study, POTS patients are frequently diagnosed with other conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome, small fiber peripheral neuropathy, vasovagal syncope and irritable bowel syndrome, which could impact cognitive function. Finally, many POTS patients exhibit fatigue [40] as well as increased sleep-related symptoms and poor sleep efficiency [41] which may negatively impact cognitive function and overall mental health.

Study Limitations

There are potential limitations to this study. First, patients were enrolled at a tertiary care center for autonomic disorders, and thus may not reflect the broader POTS population. Second, we did not examine for gender differences, as there were no male POTS patients admitted during the enrollment period, reflecting the strong predominance of this condition for premenopausal females. Third, this study provides evidence for cognitive impairment in POTS patients in the more favorable seated position. Future studies should include standing assessments to evaluate if cognitive deficits are further exacerbated when patients are most symptomatic. Finally, this study included a relatively small number of subjects. It is possible that some variables may have reached significance with a larger cohort; however, our sample size was similar to other clinical studies in POTS patients.

Clinical Perspectives

Mental clouding is an almost universal finding in patients with POTS, but this phenomenon is still poorly understood. This study provides new insight into the pattern of cognitive dysfunction in POTS, which is characterized by specific deficits in selective attention, cognitive processing speed, and executive function. Further studies are needed, however, to identify the precise pathophysiological mechanisms involved in these cognitive deficits and to determine targeted clinical strategies for management of mental clouding in this condition. Importantly, cognitive dysfunction in POTS is present in the absence of orthostatic stress, and therefore could represent an independent consequence of disease pathophysiology in these patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our participants and the staff of the Elliot V. Newman Clinical Research Center. Dr. Arnold was supported by an American Heart Association grant (11POST7330010). Dr. Haman is supported by NIMH grants R34 MH094535-01A1 and RC1 MH088329. Dr. Biaggioni is a consultant for Chelsea Therapeutics and Astra Zeneca, is supported by NIH grants P01 HL056693 and U54 NS065736, and receives research funds from Astra Zeneca and Forest Laboratories. Dr. Robertson is a consultant for Chelsea Therapeutics, and is supported by NIH grants P01 HL056693 and U54 NS065736. Dr. Raj is supported by NIH grant R01 HL102387 and provides expert medical consulting for law firms regarding POTS patients.

Funding:

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01HL102387, U54NS065736, P01HL56693 and UL1TR000445.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Conception and design: Drs. Haman, V. Raj, Biaggioni, Robertson and S. Raj; Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data: Drs. Arnold, Haman, Garland, V. Raj, Dupont, and S. Raj; Drafting of the manuscript: Drs. Arnold, Haman and S. Raj; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors; Statistical analysis: Dr. Dupont; Obtaining funding: Drs. Haman and S. Raj; Administrative, technical, or material support: Drs. Arnold, Haman, Garland and V. Raj; Supervision: Drs. Haman, Biaggioni, Robertson and S. Raj.

Reference List

- 1.Low PA, Opfer-Gehrking TL, Textor SC, Benarroch EE, Shen WK, Schondorf R, Suarez GA, Rummans TA. Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) Neurology. 1995;45:S19–S25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raj SR. The Postural Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS): pathophysiology, diagnosis & management. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2006;6:84–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman R, Wieling W, Axelrod FB, Benditt DG, Benarroch E, Biaggioni I, Cheshire WP, Chelimsky T, Cortelli P, Gibbons CH, Goldstein DS, Hainsworth R, Hilz MJ, Jacob G, Kaufmann H, Jordan J, Lipsitz LA, Levine BD, Low PA, Mathias C, Raj SR, Robertson D, Sandroni P, Schatz IJ, Schondorf R, Stewart JM, van Dijk JG. Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome. Auton Neurosci. 2011;161:46–48. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karas B, Grubb BP, Boehm K, Kip K. The postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: a potentially treatable cause of chronic fatigue, exercise intolerance, and cognitive impairment in adolescents. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2000;23:344–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2000.tb06760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benrud-Larson LM, Dewar MS, Sandroni P, Rummans TA, Haythornthwaite JA, Low PA. Quality of life in patients with postural tachycardia syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:531–537. doi: 10.4065/77.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raj V, Haman KL, Raj SR, Byrne D, Blakely RD, Biaggioni I, Robertson D, Shelton RC. Psychiatric profile and attention deficits in postural tachycardia syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:339–344. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.144360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ocon AJ, Messer ZR, Medow MS, Stewart JM. Increasing orthostatic stress impairs neurocognitive functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome with postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;122:227–238. doi: 10.1042/CS20110241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart JM, Medow MS, Messer ZR, Baugham IL, Terilli C, Ocon AJ. Postural neurocognitive and neuronal activated cerebral blood flow deficits in young chronic fatigue syndrome patients with postural tachycardia syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1185–H1194. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00994.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wechsler D. The Wechsler Test of Adult Reading. San Antonio Texas: PsychCorp; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruff RM, Niemann H, Allen CC, Farrow CE, Wylie T. The Ruff 2 and 7 Selective Attention Test: A Neuropsychological Application. Percept Mot Skills. 1992;75:1311–1319. doi: 10.2466/pms.1992.75.3f.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lezak MD, Howieson D, Oring DW, Annay HJ, Ischer JS. Neuropsychological Assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Randt CT, Brown ER. Randt Memory Test. Bayport, New York: Life Science Associates; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruff RM, Light RH, Parker SB, Levin HS. Benton Controlled Oral Word Association Test: reliability and updated norms. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1996;11:329–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen AR, Rohwer WD. The Stroop color-word test: a review. Acta Psychol (Amst) 1966;25:36–93. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(66)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz GE, Davidson RJ, Goleman DJ. Patterning of cognitive and somatic processes in the self-regulation of anxiety: effects of meditation versus exercise. Psychosom Med. 1978;40:321–328. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197806000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moritz S, Kuelz AK, Jacobsen D, Kloss M, Fricke S. Severity of subjective cognitive impairment in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression. J Anxiety Disord. 2006;20:427–443. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dupont WD, Plummer WD. Power and sample size calculations. A review and computer program. Control Clin Trials. 1990;11:116–128. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(90)90005-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers RD, Andrews TC, Grasby PM, Brooks DJ, Robbins TW. Contrasting cortical and subcortical activations produced by attentional-set shifting and reversal learning in humans. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12:142–162. doi: 10.1162/089892900561931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanks RA, Millis SR, Ricker JH, Giacino JT, Nakese-Richardson R, Frol AB, Novack TA, Kalmar K, Sherer M, Gordon WA. The predictive validity of a brief inpatient neuropsychologic battery for persons with traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:950–957. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson JK, Lui LY, Yaffe K. Executive function, more than global cognition, predicts functional decline and mortality in elderly women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:1134–1141. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.10.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vazzana R, Bandinelli S, Lauretani F, Volpato S, Lauretani F, Di IA, Abate M, Corsi AM, Milaneschi Y, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Trail Making Test predicts physical impairment and mortality in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:719–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02780.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poda R, Guaraldi P, Solieri L, Calandra-Buonaura G, Marano G, Gallassi R, Cortelli P. Standing worsens cognitive functions in patients with neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. Neurol Sci. 2012;33:469–473. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0746-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perlmuter LC, Greenberg JJ. Do you mind standing?: cognitive changes in orthostasis. Exp Aging Res. 1996;22:325–341. doi: 10.1080/03610739608254015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeLuca J, Christodoulou C, Diamond BJ, Rosenstein ED, Kramer N, Natelson BH. Working memory deficits in chronic fatigue syndrome: differentiating between speed and accuracy of information processing. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:101–109. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704101124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heims HC, Critchley HD, Martin NH, Jager HR, Mathias CJ, Cipolotti L. Cognitive functioning in orthostatic hypotension due to pure autonomic failure. Clin Auton Res. 2006;16:113–120. doi: 10.1007/s10286-006-0318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibbons CH, Centi J, Vernino S, Freeman R. Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy with reversible cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:461–466. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shanks L, Jason LA, Evans M, Brown A. Cognitive impairments associated with CFS and POTS. Front Physiol. 2013;4:113. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu Q, VanGundy TB, Galbreath MM, Shibata S, Jain M, Hastings JL, Bhella PS, Levine BD. Cardiac origins of the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2858–2868. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arnold AC, Okamoto LE, Diedrich A, Paranjape SY, Raj SR, Biaggioni I, Gamboa Low-dose propranolol and exercise capacity in postural tachycardia syndrome: a randomized study. Neurology. 2013;80:1927–1933. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318293e310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehrabian S, Duron E, Labouree F, Rollot F, Bune A, Traykov L, Hanon O. Relationship between orthostatic hypotension and cognitive impairment in the elderly. J Neurol Sci. 2010;299:45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masuki S, Eisenach JH, Johnson CP, Dietz NM, Benrud-Larson LM, Schrage WG, Curry TB, Sandroni P, Low PA, Joyner MJ. Excessive heart rate response to orthostatic stress in postural tachycardia syndrome is not caused by anxiety. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:896–903. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00927.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khurana RK. Experimental induction of panic-like symptoms in patients with postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Auton Res. 2006;16:371–377. doi: 10.1007/s10286-006-0365-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esler M, Alvarenga M, Pier C, Richards J, El-Osta A, Barton D, Haikerwal D, Kaye D, Schlaich M, Guo L, Jennings G, Socratous F, Lambert G. The neuronal noradrenaline transporter, anxiety and cardiovascular disease. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20:60–66. doi: 10.1177/1359786806066055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biederman J, Spencer T. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as a noradrenergic disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1234–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vincent S, Bieck PR, Garland EM, Loghin C, Bymaster FP, Black BK, Gonzales C, Potter WZ, Robertson D. Clinical assessment of norepinephrine transporter blockade through biochemical and pharmacological profiles. Circulation. 2004;109:3202–3207. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130847.18666.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schroeder C, Tank J, Boschmann M, Diedrich A, Sharma AM, Biaggioni I, Luft FC, Jordan J. Selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibition as a human model of orthostatic intolerance. Circulation. 2002;105:347–353. doi: 10.1161/hc0302.102597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Low PA, Novak V, Spies JM, Novak P, Petty GW. Cerebrovascular regulation in the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) Am J Med Sci. 1999;317:124–133. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199902000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross AJ, Medow MS, Rowe PC, Stewart JM. What is brain fog? An evaluation of the symptom in postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Auton Res. 2013;23:305–311. doi: 10.1007/s10286-013-0212-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bagai K, Wakwe CI, Malow B, Black BK, Biaggioni I, Paranjape SY, Orozco C, Raj SR. Estimation of sleep disturbances using wrist actigraphy in patients with postural tachycardia syndrome. Auton Neurosci. 2013;177:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.