Abstract

Objectives

Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN), thought to represent the dominant precursor of pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC), is often found synchronously adjacent to resected PDAC tumors. However, its prognostic significance on outcome following PDAC resection is unknown.

Methods

A total of 342 patients who underwent resection for PDAC between 2005 and 2010 at a single institution were identified and stratified according to highest grade of PanIN demonstrated surrounding the tumor. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of each patient and tissue were recorded and analyzed. The primary outcome was length of survival following resection.

Results

An absence of PanIN lesions was identified in 32 cases (9%), low grade PanIN without synchronous high grade lesions was identified in 52 cases (15%), and high grade PanIN was found in 258 cases (75%). Median survival in the non-PanIN group was 12.8 months, 26.3 months for the low grade PanIN group, and 23.8 months for the high grade PanIN groups (P=.043). In multivariable analysis, absence of PanIN was independently associated with poor survival (P= .002).

Conclusions

The patients who demonstrate an absence of PanIN in the pancreatic tissue adjacent to the resected PDAC tumor have shorter post-resection survival compared to those who demonstrate a PanIN lesion.

Keywords: pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia, pancreatic cancer

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is highly lethal and is the second leading cause of digestive cancer related death in the United States. An estimated 45,220 new cases of PDAC and an estimated 38,460 PDAC-driven deaths will occur in 2013 1. Furthermore, the mortality from this disease appears to be rising, despite the fact that overall cancer mortality is falling 1. While less than 20% of patients diagnosed with PDAC are surgical candidates, surgery is the only potentially curative treatment. Even in the subset of patients who undergo tumor resection with curative intent, prognosis after resection remains poor, with five-year survival estimated at 10 to 25 percent 2-7. In addition, many trials looking at outcomes in adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy have failed to show a survival benefit over surgery alone 8.

Therefore, understanding which patients do well following resection is important both for patient’s expectations, and to maximize effective management 9. The few validated prognostic factors predicting survival after PDAC tumor resection independent of TNM staging include status of surgical margins, tumor size, tumor differentiation, presence or absence of lymphatic invasion, and post-operative CA 19-9 levels 3, 7, 9.

One aspect of prognosis following PDAC resection that remains yet to be studied is the co-presence of lesions known as pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN), which refers to non-invasive proliferation and metaplasia of small caliber ductal epithelium 10. One likely reason that PanIN has been poorly studied compared to other precursor lesions is that PanIN lesions cannot be accurately identified pre-operatively by existing imaging modalities and can only be identified histologically. This is in contrast to intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) and mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs), two other precursor lesions known to associate with PDAC which can readily be seen radiographically and diagnosed pre-operatively.

PanIN lesions are graded from low-grade dysplasia (PanIN 1) to severe dysplasia/carcinoma in situ (PanIN 3), with PanIN 2 as an intermediate grade. PanIN 2 and 3 are both generally considered high-grade lesions with higher risk of malignant transformation compared to PanIN 1 11-14. The progression from low grade to high grade PanIN is thought to occur in a step-wise accumulation of genetic mutational events ultimately leading to PDAC 15. As such, PanIN status surrounding resected tumor could be an important biomarker for prognosis. A more accurate assessment of prognosis may help guide clinicians and patients in determining how aggressively to pursue treatment with the goal of curative intent and survival prolongation.

Low grade PanIN is frequently found in normal pancreas, whereas high grade PanIN is less common. On the other hand, high grade PanIN is found commonly in normal tissue adjacent to resected PDAC tumors. One study demonstrated high grade PanIN in 59% of PDAC resections compared to 17% of matched normal control pancreas specimens 14. Despite the fact that PanIN commonly coexists with PDAC, there is scant data on its prognostic significance on survival following PDAC resection. One study demonstrated that the presence of PanIN specifically at the surgical margin does not have any prognostic significance 16. The purpose of the current study was to determine if the presence of PanIN has a prognostic or predictive effect on survival following resection for PDAC with curative intent.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board. Patients who underwent surgical resection for PDAC between January 2005 and December 2010 at the Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) were identified from a prospective database and included in the analysis. Baseline characteristics of the cohort were recorded, including age, gender, ethnicity, and tobacco history, and use of adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The pathology report of each resected tumor (formatted in a stereotyped fashion across all cases) was queried from the CUMC clinical data warehouse 17 for the following variables: TNM stage of tumor, largest dimension of tumor, degree of differentiation of tumor, presence of adenocarcinoma at resected margin, presence of lymph nodes positive for adenocarcinoma, and presence of perineural invasion.

The pathology report was additionally investigated for highest degree of PanIN found anywhere within the surgical specimen. In cases where no PanIN was identified in the pathology report, the histology slides were reviewed by an experienced pancreas pathologist to confirm absence of PanIN. The primary endpoint of the study was survival following surgical resection.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using SAS 9.3 (Cary, North Carolina). Demographic and histologic comparisons across groups were made using ANOVA testing. Kaplan–Meier curves were generated and survival compared across PanIN strata with the Log Rank test. Cox Proportional Hazards Models were then constructed to control for additional variables. All p-values were two-sided and a level 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of the cohort

Baseline characteristics of the cohort are recorded in Table 1. Our study included 342 subjects who were followed for a mean of 22 months (range 0 to 83 months). The cohort had a mean age at time of surgery of 67 (range 37 to 91) and included 181 men (53%) and 161 women (47%). 273 subjects were Caucasian (80%), 12 were African American (4%), 15 were Hispanic (4%), 18 were other ethnicities (5%), and 24 patients were of unknown ethnicity (7%). 175 subjects had a smoking history (51%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of each cohort.

| VARIABLE | No PanIN (n=32) |

Low Grade PanIN (n=52) |

High Grade PanIN (n=258) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 64 (14) | 67 (8) | 68 (10) | 0.22 |

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Male | 17 (53) | 26 (50) | 138 (53) | 0.89 |

| Female | 15 (47) | 26 (50) | 120 (47) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian (%) | 25 (78) | 44 (85) | 204 (79) | 0.84 |

| Black (%) | 2 (6) | 4 (8) | 6 (2) | |

| Latino (%) | 1 (3) | 2 (4) | 12 (5) | |

| Other (%) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 16 (6) | |

| Unknown (%) | 2 (6) | 2 (4) | 20 (8) | |

| Smoking history? | ||||

| Yes (%) | 17 (53) | 25 (48) | 133 (52) | 0.75 |

| No (%) | 12 (38) | 23 (44) | 97 (38) | |

| Unknown (%) | 3 (9) | 4 (8) | 28 (11) | |

| Receiving chemo (%) | ||||

| Yes (%) | 7 (22) | 12 (23) | 83 (32) | 0.17 |

| No (%) | 16 (50) | 29 (56) | 113 (44) | |

| Unknown (%) | 9 (28) | 11 (21) | 60 (23) |

At time of data censoring, 122 patients were still alive (36%). Median survival time of the cohort after resection was 23 months (range 0-84 months). One-year survival of the cohort was 71% and three-year survival was 30%.

Pathologic data

Pathology characteristics of each cohort are summarized in Table 2. The tumor was found in the head of the pancreas in 252 cases (73%). Mean tumor size (in largest dimension) was 3.2 ± 1.6 cm. Lymph nodes positive for malignant cells were identified in 233 cases (68%). Surgical margins were positive in 91 cases (26%). 34 subjects had stage I disease (10%), 69 had stage IIA disease (20%), 217 had stage IIB disease (63%), and 20 (6%) had stage III or IV disease. In terms of histologic grade, 25 tumors (7%) were well differentiated (Grade 1), 165 (48%) were moderately differentiated (Grade 2), 144 (42%) were poorly differentiated (Grade 3), and 4 (1%) were undifferentiated (Grade 4). Perineural invasion was identified in 269 cases (79%) and lymphovascular invasion was seen in 215 cases (63%).

Table 2.

Pathologic characteristics of each cohort.

| VARIABLE | No PanIN (n=32) |

Low Grade PanIN (n=52) |

High Grade PanIN (n=258) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Largest Tumor Dimension ± SD |

3.3 ± 1.5 | 3.1 ± 2.0 | 3.3 ± 1.5 | 0.85 |

| Stage (%) | ||||

| I | 6 (19) | 5 (10) | 23 (9) | 0.34 |

| IIA | 9 (28) | 10 (19) | 50 (19) | |

| IIB | 11 (34) | 34 (65) | 172 (68) | |

| III | 6 (19) | 0 (0) | 11 (4) | |

| IV | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 2 (1) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Histologic grade | ||||

| G1 | 2 (6) | 2 (4) | 21 (8) | 0.01 |

| G2 | 9 (28) | 28 (55) | 128 (50) | |

| G3 | 18 (56) | 21 (41) | 105 (41) | |

| G4 | 3 (9) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | |

| Tumor Location | ||||

| Head | 21 (70) | 35 (67) | 196 (76) | 0.3 |

| Body/Tail | 9 (28) | 13 (25) | 50 (19) | |

| Unknown | 2 (6) | 4 (8) | 12 (5) | |

| Positive margins? | ||||

| Yes | 7 (22) | 11 (21) | 73 (28) | 0.49 |

| No | 24 (75) | 38 (73) | 175 (68) | |

| Unknown | 1 (3) | 3 (6) | 10 (4) | |

| Positive lymph nodes |

||||

| Yes | 16 (50) | 35 (67) | 182 (71) | 0.043 |

| No | 16 (50) | 15 (29) | 72 (28) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 4 (2) | |

| Perineural invasion (%) |

||||

| Yes | 25 (78) | 33 (63) | 211 (82) | 0.02 |

| No | 7 (22) | 18 (35) | 46 (18) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion (%) |

||||

|

Yes |

17 (53) | 30 (58) | 168 (65) | 0.35 |

|

No |

14 (44) | 21 (41) | 87 (34) | |

|

Uknown |

1 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (1) |

PanIN analysis

An absence of PanIN was demonstrated in 32 cases (9%). Low grade PanIN (PanIN 1) without any co-existing high-grade lesions was found in 52 cases (15%), and high grade PanIN (2 or 3) was found in 258 lesions (75%).

Using ANOVA testing to compare across cases stratified by PanIN status, there were no significant differences with respect to age (P =.22), gender (P= .89), ethnicity (P =.84), smoking history (P =.75), or use of chemotherapy (adjuvant or neoadjuvant; P =.17). In terms of pathologic characteristics, no significant differences were demonstrated between PanIN groups with respect to size of tumor (P= .85); stage of disease (P =.34); tumor location (P =.30); prevalence of positive margins (P =.49); or lymphovascular invasion (P=.35).

Subjects in the non-PanIN group demonstrated more poorly differentiated tumors (P= .01). The non-PanIN group displayed decreased frequency of positive lymph nodes (50% compared to 67% for the low grade PanIN group and 71% for the high grade group; P= .043). In addition, PanIN groups differed with respect to presence of perineural invasion, although there was no clear trend comparing the non-PanIN group to the other groups (78% compared to 63% for the low grade and 82% for the high grade group; P =.02).

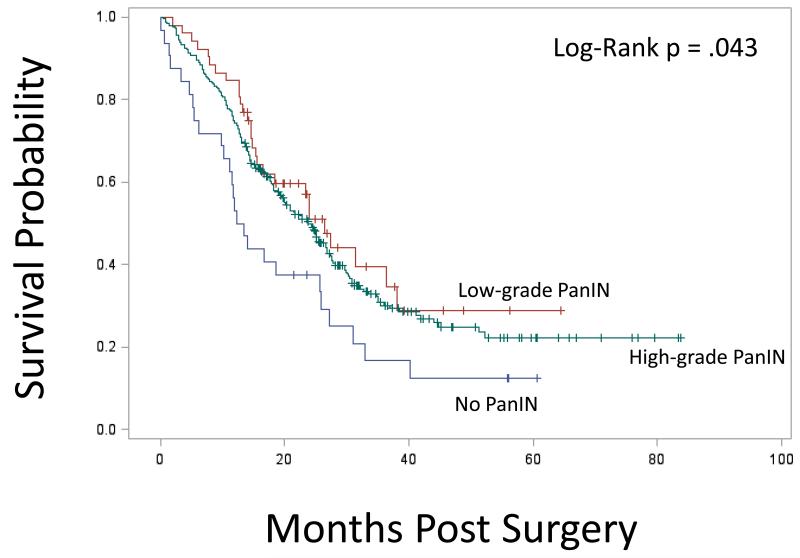

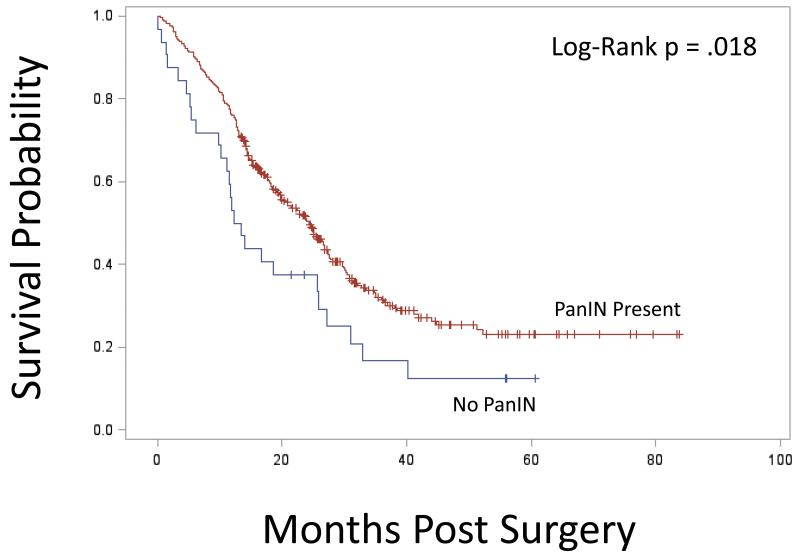

Kaplan-Meier survival stratified by PanIN grade is presented in Figure 1A. Median survival in the non-PanIN group was 12.8 months compared to 26.3 months for the low grade PanIN group and 23.8 months in the high-grade PanIN group (Figure 1A). Survival in the non-PanIN group was significantly decreased compared to high grade and low-grade PanIN groups (Figure 1A; P = .043). Survival curves comparing all patients with any grade PanIN to the non-PanIN group is presented in Figure 1B; here again the non-PanIN group survival was significantly decreased (P = .018). In univariate analysis, the hazard ratio (HR) for death for the non-PanIN group compared to the low grade PanIN 1 group was 1.89 (CI 1.10-3.22; P = .02); and compared to the high grade PanIN group was 1.59 (CI 1.05-2.41; P= .03). There was no difference in univariate analysis comparing risk of death in low grade to high PanIN cohorts (HR 0.84; CI 0.57-1.26; P= .41).

Figure 1A.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for cohorts of no PanIN, low grade PanIN, and high grade PanIN. Survival in the non-PanIN group was significantly decreased compared to high grade and low-grade PanIN groups (P = .043 comparing all groups).

Figure 1B.

Kaplan-Meier curves comparing the group with no PanIN to all patients with PanIN of any grade. The non-PanIN group survival was significantly decreased compared to all patients with PanIN of any grade (P= .018).

In multivariable analysis, the HR for death for the non-PanIN group compared to the low grade panIN group (PanIN 1) was 2.5 (CI 1.39-4.52; P =.002), controlling for age of patient, stage of disease, histologic grade of tumor, margin status, and presence of lymphovascular invasion. The HR for death of the non-PanIN group compared to the high grade PanIN group (PanIN 2/3) was 2.23 (CI 1.39-3.57; P <.001), controlling for the same variables. The addition of current smoking (P =.31), a history of smoking (P =.26), perineural invasion (P =.61), presence of positive lymph nodes (P =0.38), and maximum tumor diameter (P =.14) did not predict survival after controlling for tumor stage and patient age.

CONCLUSIONS

We demonstrate that the patients who lack PanIN in the pancreatic tissue adjacent to the PDAC tumor (9% of our cohort) have shorter post-resection survival compared to those who have PanIN lesions, controlling for multiple factors known to have prognostic significance, including stage of disease, histologic grade, margin status, and presence of lymphovascular invasion. While we did find that a greater proportion of the tumors in the group were poorly differentiated, controlling for histologic grade did not diminish the survival difference seen across groups. While groups differed significantly with regard to frequency of perineural invasion, there were no clear trends comparing the non-PanIN group to the other groups, as the low grade PanIN group showed less perineural invasion while the high grade PanIN group showed more perineural invasion. Finally, the non-PanIN group showed significantly fewer subjects with positive lymph nodes compared to other groups.

One of the great controversies in the field of PDAC research is the cellular origin of tumor cells, which remains to be firmly established, in part because most patients present with advanced disease long after the earliest developmental steps have occurred 18. Animal data attempting to isolate the cell of origin have been conflicting, and current evidence suggests that many compartments in a mature pancreas may have malignant potential 18. Furthermore, it is clear from genetic studies that significant heterogeneity exists between individual tumors, and patterns have been identified to allow pathologists to sub-classify PDAC tumors with respect to both morphology and molecular genetics 19, 20.

It is therefore reasonable to assume that subtypes of PDAC tumors exist which develop via independent pathways. Consistent with this concept that PDAC represents a collection of disease subtypes, PDAC is known to arise from a heterogeneous group of precursor lesions, including not only PanIN but also IPMNs and MCNs 10. In addition, studies of screening for patients with a strong family history of pancreatic cancer have shown an association with multiple types of precursor lesions, including PanIN, cystic lesions, and IPMN 21. One large screening study of asymptomatic patients with a strong family history of pancreatic cancer found that greater than 40% of subjects had at least one pancreatic mass 22.

PanIN is thought to be the dominant precursor lesion, a hypothesis generated from several lines of evidence. Firstly, animal models of PDAC have demonstrated a convincing progression from PanIN to PDAC (including evidence from both hamster and mouse models) 10, 23, 24. In addition, molecular analysis of genetic abnormalities found in human tumors has demonstrated a predictable accumulation of genetic abnormalities in sequence from low grade PanIN to PDAC, starting with abnormalities in k-ras, a step thought necessary to lead to PanIN and subsequent PDAC 10, 13, 24-26. Furthermore, pathological specimens of pancreata harboring PDAC contain PanIN lesions (both low and high grade) in greater frequency than seen in control pancreas specimens 14. High-grade PanIN lesions are commonly found adjacent to PDAC but only rarely seen otherwise 10. PanIN is found more commonly associated with familial pancreatic cancer syndromes compared to sporadic pancreatic cancer 27. In familial syndromes, it has been speculated that the entire pancreatic bed is abnormal and arises to multi-focal PanIN in a non-contiguous process, leading to frequent recurrence of disease without complete pancreatectomy 28. In addition, high grade PanIN synchronous with pancreatic cancer has been associated with recurrent disease after pancreatic cancer resection 29. PanIN seems to be especially common in patients with early onset PDAC and was found in 96% of cases in one series 30. Previous work has shown that the majority of high-grade PanIN lesions occur directly adjacent to the adenocarcinoma but lower grade lesions occurred more sporadically throughout the tissue 31. Finally, case reports have demonstrated patients with PanIN lesions later developing PDAC 32.

It is therefore believed that high grade PanIN represents an immediate precursor to the development of PDAC in a majority of cases 16. No prior studies have investigated PanIN grade or presence and absence of PanIN to determine if this could be a prognostic factor, or ultimately utilized to effect clinical management decisions. Given the understanding that PDAC can arise from various precursor lesions, it is possible that subtypes of tumors are biologically distinct and arise from a PanIN-independent pathway. Pancreatic carcinogenesis may therefore mirror colon carcinogenesis, in that while the majority of sporadic colon cancers arise via the progression from adenoma to carcinoma, there exist at least two other independent pathways to carcinoma 33. For example, defects in DNA mismatch repair give rise to colon cancers in an adenoma-independent route in patients with the Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC) syndrome.

The subset of tumors lacking PanIN may represent such a biologically distinct group, populated with more locally aggressive and poorly differentiated cancers that are arising independently from the usual PanIN route in an as yet undefined pathway. These tumors were found to be more poorly differentiated and spread to lymph nodes less frequently, which may suggest a unique tumor biology compared to tumors harboring PanIN. Patients with this subtype of cancer may have a worse prognosis that would suggest the need for more aggressive treatment with the goal of prolonging survival. Further investigation is warranted to elucidate the tumor biology of PDAC that is associated with high-grade PanIN lesions and those that do not demonstrate PanIN lesions.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding:

Muzzi Mirza Pancreatic Cancer Prevention and Genetics Program

Hirshberg Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research grant (PI: Harold Frucht)

NIH T32 DK083256 Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (PI: Timothy C. Wang, Recipient: Aimee L. Lucas)

Footnotes

Author contribution: Study concept and design (BGH, ALL, LGK, HF), Acquisition of data (BGH, MS, CW, FL, HF), Analysis and interpretation of data (all authors), drafting of manuscript (all authors), statistical analysis (BGH, ALL, HF).

Previously presented: Abstract/Poster presentation. American College of Gastroenterology 2012 Annual Scientific Meeting. Las Vegas, NV.

Conflicts of Interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Ca Cancer J Clin. Cancer statistics, 2013. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, et al. Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies in the 1990s: pathology, complications, and outcomes. Ann Surg. 1997;226:248–57. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199709000-00004. discussion 257-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benassai G, Mastrorilli M, Quarto G, et al. Survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Chir Ital. 2000;52:263–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millikan KW, Deziel DJ, Silverstein JC, et al. Prognostic factors associated with resectable adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Am Surg. 1999;65:618–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer of the head of the pancreas. 201 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;221:721–31. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199506000-00011. discussion 731-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY, et al. Validation of the 6th edition AJCC Pancreatic Cancer Staging System: report from the National Cancer Database. Cancer. 2007;110:738–44. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geer RJ, Brennan MF. Prognostic indicators for survival after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 1993;165:68–72. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80406-4. discussion 72-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witkowski ER, Smith JK, Tseng JF. Outcomes following resection of pancreatic cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:97–103. doi: 10.1002/jso.23267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinsella TJ, Seo Y, Willis J, et al. The impact of resection margin status and postoperative CA19-9 levels on survival and patterns of recurrence after postoperative high-dose radiotherapy with 5-FU-based concurrent chemotherapy for resectable pancreatic cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008;31:446–53. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318168f6c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scarlett CJ, Salisbury EL, Biankin AV, et al. Precursor lesions in pancreatic cancer: morphological and molecular pathology. Pathology. 2011;43:183–200. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e3283445e3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhanot U, Heydrich R, Moller P, et al. Survivin expression in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN): steady increase along the developmental stages of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:754–9. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200606000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albazaz R, Verbeke CS, Rahman SH, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression associated with severity of PanIN lesions: a possible link between chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology. 2005;5:361–9. doi: 10.1159/000086536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maitra A, Adsay NV, Argani P, et al. Multicomponent analysis of the pancreatic adenocarcinoma progression model using a pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia tissue microarray. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:902–12. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000086072.56290.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andea A, Sarkar F, Adsay VN. Clinicopathological correlates of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: a comparative analysis of 82 cases with and 152 cases without pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:996–1006. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000087422.24733.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macgregor-Das AM, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. Molecular pathways in pancreatic carcinogenesis. J Surg Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/jso.23213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthaei H, Hong SM, Mayo SC, et al. Presence of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia in the pancreatic transection margin does not influence outcome in patients with R0 resected pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:3493–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1745-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson SB. Generic data modeling for clinical repositories. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1996;3:328–39. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1996.97035024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonald OG, Maitra A, Hruban RH. Human correlates of provocative questions in pancreatic pathology. Adv Anat Pathol. 2012;19:351–62. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e318273f998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi C, Daniels JA, Hruban RH. Molecular characterization of pancreatic neoplasms. Adv Anat Pathol. 2008;15:185–95. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31817bf57d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucas AL, Shakya R, Lipsyc MD, et al. High Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Germline Mutations with Loss of Heterozygosity in a Series of Resected Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma and Other Neoplastic Lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3396–3403. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verna EC, Hwang C, Stevens PD, et al. Pancreatic cancer screening in a prospective cohort of high-risk patients: a comprehensive strategy of imaging and genetics. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5028–37. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canto MI, Hruban RH, Fishman EK, et al. Frequent detection of pancreatic lesions in asymptomatic high-risk individuals. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:796–804. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hruban RH, Adsay NV, Albores-Saavedra J, et al. Pathology of genetically engineered mouse models of pancreatic exocrine cancer: consensus report and recommendations. Cancer Res. 2006;66:95–106. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cerny WL, Mangold KA, Scarpelli DG. K-ras mutation is an early event in pancreatic duct carcinogenesis in the Syrian golden hamster. Cancer Res. 1992;52:4507–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi C, Hong SM, Lim P, et al. KRAS2 mutations in human pancreatic acinar-ductal metaplastic lesions are limited to those with PanIN: implications for the human pancreatic cancer cell of origin. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:230–6. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins MA, Bednar F, Zhang Y, et al. Oncogenic Kras is required for both the initiation and maintenance of pancreatic cancer in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:639–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI59227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi C, Klein AP, Goggins M, et al. Increased Prevalence of Precursor Lesions in Familial Pancreatic Cancer Patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7737–7743. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brentnall TA. Management strategies for patients with hereditary pancreatic cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2005;6:437–45. doi: 10.1007/s11864-005-0046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang C, Rotterdam H, Bill AZ, et al. High-grade pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) is associated with local recurrence of pancreatic adenocarcinoma after “curative” surgical resection. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:A93. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liszka L, Pajak J, Mrowiec S, et al. Precursor lesions of early onset pancreatic cancer. Virchows Arch. 2011;458:439–51. doi: 10.1007/s00428-011-1056-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hisa T, Suda K, Nobukawa B, et al. Distribution of intraductal lesions in small invasive ductal carcinoma of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2007;7:341–6. doi: 10.1159/000107268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brat DJ, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ, et al. Progression of pancreatic intraductal neoplasias to infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:163–9. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199802000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noffsinger AE. Serrated polyps and colorectal cancer: new pathway to malignancy. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:343–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]