Abstract

Amylin, a pancreatic peptide, and amyloid-beta peptides (Aβ), a major component of Alzheimer's disease (AD) brain, share similar β-sheet secondary structures, but it is not known whether pancreatic amylin affects amyloid pathogenesis in the AD brain. Using AD mouse models, we investigated the effects of amylin and its clinical analog, pramlintide, on AD pathogenesis. Surprisingly, chronic intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of AD animals with either amylin or pramlintide reduces the amyloid burden as well as lowers the concentrations of Aβ in the brain. These treatments significantly improve their learning and memory assessed by two behavioral tests, Y maze and Morris water maze. Both amylin and pramlintide treatments increase the concentrations of Aβ1-42 in cerebral spinal fluid (CSF). A single i.p. injection of either peptide also induces a surge of Aβ in the serum, the magnitude of which is proportionate to the amount of Aβ in brain tissue. One intracerebroventricular injection of amylin induces a more significant surge in serum Aβ than one i.p. injection of the peptide. In 330 human plasma samples, a positive association between amylin and Aβ1-42 as well as Aβ1-40 is found only in patients with AD or amnestic mild cognitive impairment. As amylin readily crosses the blood–brain barrier, our study demonstrates that peripheral amylin's action on the central nervous system results in translocation of Aβ from the brain into the CSF and blood that could be an explanation for a positive relationship between amylin and Aβ in blood. As naturally occurring amylin may play a role in regulating Aβ in brain, amylin class peptides may provide a new avenue for both treatment and diagnosis of AD.

Introduction

Amylin is a short peptide of 37 amino acids produced and secreted by the pancreas. It passes through the blood–brain barrier (BBB) easily1,2 and mediates brain functions, including inhibiting the appetite to improve glucose metabolism,3 relaxing cerebrovascular structure4,5 and probably enhancing neural regeneration.6 Despite the fact that amylin is a natural peptide in the body with physiological functions, it could aggregate in the pancreas in type 2 diabetes.7 Thus, an amylin analog pramlintide was developed, and it serves as an effective drug in clinical use for diabetes.8,9 Pramlintide contains 3 amino-acid differences from amylin, so does not aggregate like amylin, but it mediates all of amylin's functions in the brain.

Amylin and amyloid-beta peptide (Aβ), the major component of brain Alzheimer's disease (AD) pathology, share several features, including having similar β-sheet secondary structures,10 binding to the same amylin receptor11 and being degraded by the same protease, insulin-degrading enzyme.12, 13, 14 Interestingly, several studies show that monomeric amylin and its analogs inhibit the formation of Aβ aggregation in vitro.15, 16, 17, 18, 19 A recent study found an accumulation of amylin amyloid in the cerebrovascular system in the AD brain,20 whereas abundant Aβ in the AD brain may block the ability of amylin to bind its receptor to hinder normal amylin functions that are essential for the brain.3 All these prompted us to hypothesize that exogenous amylin class peptides would influence amyloid pathology in the AD brain. Because of their effects on glucose metabolism, cerebral vasculature, and possible neuroregeneration, the influence of amylin class peptides could be positive, especially using unamyloidgenic pramlintide. Using AD murine models, we investigated the effects of amylin and its clinical analog on Aβ amyloid pathogenesis in AD.

Methods

Mice and experimental treatments

5XFAD mice, which are APP/PS1 double transgenic mice with five familial AD mutations,21 were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Tg2576 (APPsw, K670N/M671L) transgenic mice22 were originally purchased from Taconic (Hudson, NY, USA) and were maintained on a B6SJLF1/J background at the Boston VA animal facility before this study. Dutch amyloid precursor protein (APP) mice, which are APP transgenic mice carrying the Dutch mutation (E693Q),23 were generated by Dr Hui Zheng's laboratory. Non-transgenic B6SJLF1/J wild type were used as control mice. For this study, all mice were maintained in microisolator cages in the Animal Facilities of Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA.

Amylin was purchased from AnaSpec (Fremont, CA, USA), and pramlintide was from Amylin Pharmaceutical (San Diego, CA, USA). Experimental groups of animals were matched for age, gender and weight. Female 5XFAD mice aged 3.5 months, female Tg2576 mice aged 9 months and Dutch APP mice aged 12 months were used. For the chronic treatment experiments, mice were treated with intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of amylin (200 μg kg−1) (5XFAD n=20; Tg2576 n=8) or pramlintide (200 μg kg−1) (Tg2576 n=8) vs phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 5XFAD n=20; Tg2576 n=8) once daily for 10 weeks. For the challenge experiments, the mice received a single i.p injection of amylin (200 μg kg−1) (5XFAD n=8; Tg2576 n=20; Dutch APP n=6) or pramlintide (200 μg kg−1) (Tg2576, n=8) vs PBS (5XFAD, n=8; Tg2576, n=20; Dutch APP, n=6) or intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection of amylin (200 μg kg−1) (5XFAD, n=6). For i.c.v. injection, the animals were under anesthesia to receive the procedure described previously.24 A 1-mm burr hole was drilled at a stereotactically defined ventricular location (1 mm caudal to the bregma, 1.3 mm lateral to the midline and at 2 mm depth to the pia surface), and a pulled glass pipette mounted onto a Nanoject II injector (Drummond Scientific Company, Broomall, PA, USA) was used to inject PBS or amylin. Blood draws were conducted before and after the injection to isolate serum. To collect cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), the cisterna magna was exposed under anesthesia in these mice and a pulled glass micro-pipette was used to do lumbar puncture to obtain CSF (http://www.jove.com/video/960/a-technique-for-serial-collection-cerebrospinal-fluid-from-cisterna). Generally, 10–20 μl of CSF were collected from each procedure. All animal procedures were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Boston University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Analysis of amyloid burden in brain

Brains of the mice were removed, post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 4 h, treated with 30% sucrose (in PBS) for 24 h and then embedded in Tis-sue-Tek optimal cutting temperature. Serial coronal cryosections (8–l0 μm) were cut and stored at 20 °C. After air drying and washing with PBS, quenching of endogenous peroxidase activity was performed by incubating the sections for 30 min in 0.3% H2O2 in methanol followed by PBS washes. Slides were preincubated in blocking solution (5% (vol/vol) goat serum (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and 0.3% (vol/vol) Triton-X100 in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by mouse-on-mouse blocking reagent (Vector Labs, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA, MKB-2213) incubation for 1 h. Primary antibody for the amyloid beta (mouse mAb anti-6E10, SIG-39320, 1:300, Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA) was incubated overnight. Secondary antibodies used were biotinylated mouse (Vector Labs, Inc.; 1:500) for immunohistochemistry. Immunobinding of primary antibodies was detected by biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies and Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Labs, Inc.) using DAB (3,3′-diaminobenzidine; Vector Labs, Inc.) as a substrate for peroxidase and counter-staining with hematoxylin.

End products were visualized as eight-bit RBG images using the NIS Elements BR 3.2 software (http://www.nikoninstruments.com/Products/Software/NIS-Elements-Br-Microscope-Imaging-Software) at a total magnification of × 40. For analysis of the amyloid burden, the ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) was used. After adjusting for threshold, ImageJ was used to count all plaques and to measure the area taken up by plaques, average size of the plaques and the percentage of total brain area occupied by plaques. The intensity × size values of the plaques were measured by analyzing average raw gray levels of the plaques in the image, normalizing them to the background of the slide not taken up by brain and multiplying by the average size of the plaques in the image. The brain area (cortex or hippocampus or thalamus) was outlined using the edit plane function. The number of plaques in the outlined structure was also recorded. Data were pooled from three independent readers who were blind to the treatment for all three sections and averaged. The outcomes of amyloid burden in the brain between treatment and controls were compared by using the Student's t-test.

Characterizing APP processing and measurements of Aβ levels

Brain proteins were extracted by TBS-X or extracted and fractionated into three parts: (1) TBS-soluble fraction, (2) TBS-X fraction, and (3) formic acid-soluble fraction, as described.25 The presence of APP processing was visualized by using western blots with human APP-specific antibody, 6E10, after fractionating brain proteins and using reduced SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis). The amounts of full-length APP and C99 fragments from the TBS-X soluble fraction and of secreted APP (sAPP) from the TBS-soluble fraction were also quantitated and compared using t-tests.

Cerebral Aβ levels were assayed in the total protein by TBS-X extraction of hemi-brain sucrose homogenates. The Aβ levels in serum, plasma and CSF were assayed after the samples were collected and centrifuged. We used an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method26,27 in which Aβ was trapped with either monoclonal antibody to the C-terminal of Aβ1–40 (2G3) or Aβ1–42 (21F12) and then detected with biotin-conjugated to the N-terminus of Aβ. A dilution of 6E10 was optimized to detect Aβ in the range of 50–800 pg protein in the brain samples. The dilution of blood and CSF samples was between twofold and fivefold; the lowest detection level for each Aβ peptide in blood was 1.6 pg ml−1 determined from a standard curve. Streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was added and incubated, and the signal was amplified by adding alkaline phosphatase fluorescent substrate (Promega), which was then measured.

Behavioral tests and data analysis

All behavioral experiments were done blind with respect to the treatment and the genotype of the mice. Behavioral data were analyzed using t-tests to determine the significance of differences.

Y maze test with spontaneous alternation performance21 (n=10 per group) was performed three times with different groups of 5XFAD, Tg2576 and control mice after the treatments. Each mouse was placed in the center of the symmetrical Y maze and was allowed to explore freely through the maze during a 5-min session. The sequence and total number of arms entered were recorded. Percentage of alternation was determined as follows: number of trials containing entries into all three arms/maximum possible alternations × 100. The maximum possible alterations=total number of arms entered−2.

Morris water maze test with spatial learning and memory performance28 was used with 5XFAD mice (n=10 per group) after the completion of treatment. All mice underwent reference memory training with a hidden platform in one quadrant of the pool for 10 days with four trials per day. After the last trial of day 10, the platform was removed, and each mouse received one 60-s swim probe trial. Escape latency (in seconds) is reported in Figure 1. Other indices, including length of swim path, swim speed, percentage of time in the outer zone and percentage of time and path in each quadrant of the pool were also recorded using an HVS image video tracking system (Reston, VA, USA).

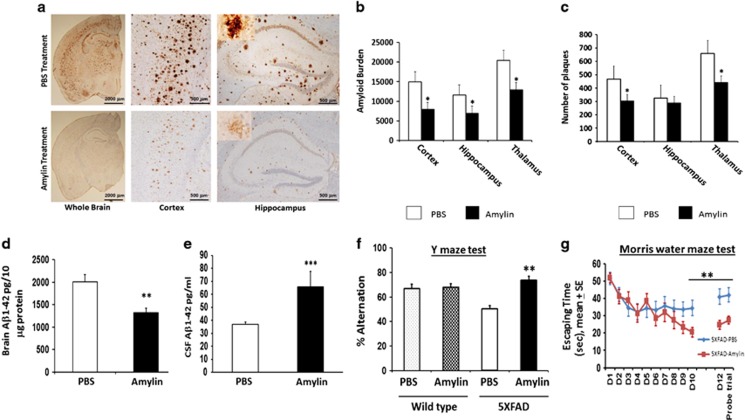

Figure 1.

Amylin treatment of 5XFAD mice reduces the amyloid burden and improves their learning and memory. At 3.5 months of age, 5XFAD mice were treated by intraperitoneal injection of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or amylin (200 pg kg−1) daily for 10 weeks (n=10 per group) (Supplementary Table S1). (a) Dense-cored Aβ plaque burden is reduced in the whole brain, including the cerebral cortex and the hippocampus. (b) Amylin-treated mice had a significant reduction in Aβ amyloid burden in the cortex, hippocampus and thalamus quantitated by average amyloid intensity × plaque size. (c) Compared with PBS treatment, the amylin-treated mice also had fewer plaques in the cortex and thalamus, while the hippocampus region only showed a tendency. Compared with the PBS treatment, the amylin-treated mice had lower concentration of Aβ1-42 (pg per 10 μg brain protein) in the brain (d) (P=0.005) but had higher concentrations of Aβ1-42 in CSF (pg ml−1) (e) (P=0.04). The amylin-treated 5XFAD mice illustrated improved cognition by showing increased percentage of alternation in the Y maze test (f) (P=0.001) and by showing shortened times in Morris water maze test (g) in finding the hidden platform at day 10 (D10) (P=0.005), in memory at day 12 (D12) after the completion of training and skipping day 11 (P=0.002) and in the probe trial (P=0.03). Mean±s.e. was used with *P<0.0001; **P<0.01; ***P<0.05.

In vitro BACE1 activity assay

BACE1 activity was measured by incubating recombinant BACE1 with a 9mer substrate (Dabcyl-SEVNLDAEF-Edans). In brief, 0.2 μg of recombinant BACE1 was pre-incubated for 5 min in the presence of PBS, a known BACE1 inhibitor,29 or amylin or pramlintide in BACE1 activity assay buffer (50 mM NaOAc (pH 4.5), 1 mg ml−1 BSA, 15 mM EDTA (pH 4.5), 0.8% CHAPS). Then the substrate at 5 μM was added to the reaction, and samples were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Cleavage of BACE1 substrate was measured in fluorescence intensities (excitation at 340 nm and emission at 492 nm) using EnVision Multilabel Reader (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA, USA). A specific BACE1 activity was calculated after subtracting the assay background. For measuring IC50 of amylin, different concentrations of amylin were incubated with recombinant BACE1, and BACE1 activity was measured as described above.

Human study

The plasma samples from the Nutrition, Aging and Memory in the Elderly (NAME) study27 were used for this study. The protocol and consent form were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tufts University New England Medical Center. The measurements of plasma Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 are described above. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used to measure plasma amylin according to the manufacturer's instructions (LINCO Research, St Charles, MO, USA).

Diagnosis of dementia

The diagnosis of dementia was based on the DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition) criteria. NINCDS-ADRDA guidelines30 were used to determine whether criteria were met for a diagnosis of possible or probable AD.

Diagnosis of amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

The diagnostic criteria for MCI were based on Petersen et al.31 1999 guidelines, with some modifications to broaden the concept of MCI. Those with memory impairment only or cognitive impairment including memory and other domains were considered to have amnestic MCI; those without forgetfulness and with impairments in other cognitive domains, such as executive and visuospatial dysfunction, were considered to have non-amnestic MCI.

Definition of the controls

Subjects were considered cognitively intact if they were not demented and scored no more than 1 s.d. below the mean of age- and education-defined strata on MMSE (mini mental state exam) and no more than 1.5 s.d. below the mean of age- and education-defined strata on the neuropsychological tests.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS (version 9.1, Middleton, MA, USA). Normally distributed variables such as age and MMSE scores were presented as mean±s.d. and were compared using analysis of variance. Amylin, Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 were transformed to Log10 for association analyses owing to their skewed distributions. Univariate analyses were performed to determine the correlation coefficients between amylin and Aβ1–42 or Aβ1–40. Multivariate linear regression was performed to evaluate the associations between amylin and Aβ1–42 or Aβ1–40 after adjusting for potential confounders.

Results

Treatment with amylin or its analog reduces the AD pathology

We treated APP transgenic mice 5XFAD, which have abundant Aβ1–42 but little or no Aβ1–40 in the brain,21 by i.p. injection of amylin (200 μg kg−1) once daily for 10 weeks (n=10 in each group) (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Compared with controls, amylin treatment significantly reduced the amyloid pathology in the cortex, hippocampus and thalamus (Figure 1a). Amylin-treated mice had the reduction in both the size and intensity of amyloid plaques in these brain regions (P<0.0001; Figure 1b) and had decreased numbers of amyloid plaques wherever measured, except for such a tendency in the hippocampus (Figure 1c). Measurements of Aβ indicated that the amylin treatment also reduced the level of Aβ1–42 in brain tissue (P=0.005; Figure 1d) but increased the level of Aβ1–42 in CSF (P=0.04; Figure 1e).

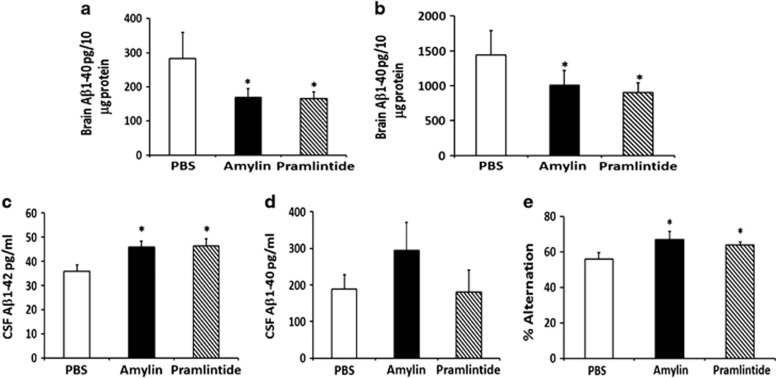

To validate the amylin specificity of this effect, we used either amylin or pramlintide to treat another AD mouse line, Tg257622 (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S2). Unlike 5XFAD mice, Tg2576 mice generate both Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 in the brain. Amylin and pramlintide treatments had similar effects in reducing Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 in the brain (Figure 2a). Although both amylin and pramlintide treatment effectively increased Aβ1–42 in CSF, neither affected Aβ1–40 in CSF to a statistically significant level (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Treatment of Tg2576 mice with amylin or its analog pramlintide reduces the amyloid burden and improves their learning and memory. At 9 months of age, Tg2576 mice were treated with intraperitoneal injection of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), amylin (200 pg kg−1) or pramlintide (200 pg kg−1) daily for 10 weeks (n=8 per group) (Supplementary Table S2). Both amylin- and pramlintide-treated mice had reduced concentrations of (a) Aβ1-42 (measured as pg per 10 μg brain protein) and (b) Aβ1–40 in the brain compared with PBS-treated controls. (c) Both amylin- and pramlintide-treated mice had increased concentrations of Aβ1–42 (pg ml−1) in CSF, but (d) neither treatment significantly affected the concentration of Aβ1–40. (e) Compared with PBS treatment, both amylin- and pramlintide-treated mice exhibited improved cognition by showing increased percentage of alternation in the Y maze test. Mean±s.e. was used with *P<0.05.

Treatment with amylin or its analog improves learning and memory

To evaluate the effect of amylin treatment on learning and memory, we conducted Y maze and Morris water maze behavioral tests in these mice. We found that amylin treatment significantly increased the average percentage of alternation in the Y maze test in 5XFAD mice (P=0.0001) but not in control mice (Figure 1f). In the Morris water maze test, amylin treatment reduced the time for acquisition during maze training (P=0.01) and shortened the time for memory retention (P=0.007) and for probe trial (P=0.02) 2 days after maze training (Figure 1g). Again, in Tg2576 mice, both amylin and pramlintide treatments equally improved the performance of mice in the Y maze test (Figure 2c). With two different behavioral tests in two different AD mouse models, these data demonstrate that both peripheral treatments with either amylin or pramlintide improved learning and memory in these mice.

Amylin and pramlintide enhance the removal of Aβ out of the brain

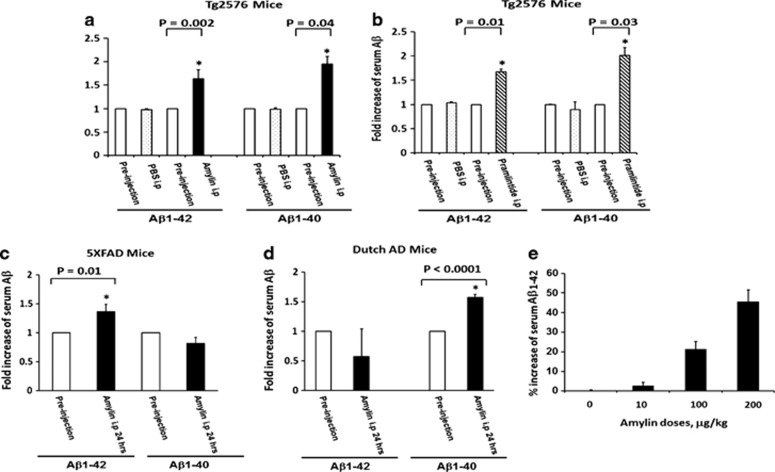

To elucidate the mechanism by which amylin class peptides reduce the amyloid pathology in the brain but increased the concentrations of Aβ1–42 in CSF (Figures 1 and 2), we first tested the possibility that amylin class peptides stimulate the removal of the toxic Aβ from the AD brain to another compartment of the body. We measured Aβ levels in serum before and after i.p injection of a single dose of amylin or pramlintide into the AD mice. A single dose of amylin in Tg2576 mice, but not in control mice, produced a significant increase in serum Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 at different time points (Supplementary Figure 1) up to 24 h (Figure 3a). In contrast to amylin, injection of PBS did not induce the Aβ surge in blood in Tg2576 mice, indicating that the increase of serum Aβ was provoked by the injection of amylin (Figure 3a). Consistently, a single i.p. injection of pramlintide also provoked surges of Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 in serum similar to those induced by amylin (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

A single injection of amylin or pramlintide induces a change of serum Aβ in the amyloid precursor protein (APP) transgenic mice. After one intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of phosphate-buffered saline vs amylin (a) or pramlintide (b) (200 μg kg−1) in Tg2576 mice, changes in levels of serum Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 were observed. A single i.p. injection of amylin induced an increase in serum Aβ1–42 but not Aβ1–40 in 5XFAD mice (c); in contrast, i.p. injection of amylin induced an increase in serum Aβ1–40 but not Aβ1–42 in Dutch APP mice (d). In 5XFAD mice, the changes in serum Aβ1–42 in response to a challenge with amylin were dose dependent (e). Significance of changes in Aβ levels before and after the injection was determined by Student's t-test. *P<0.05.

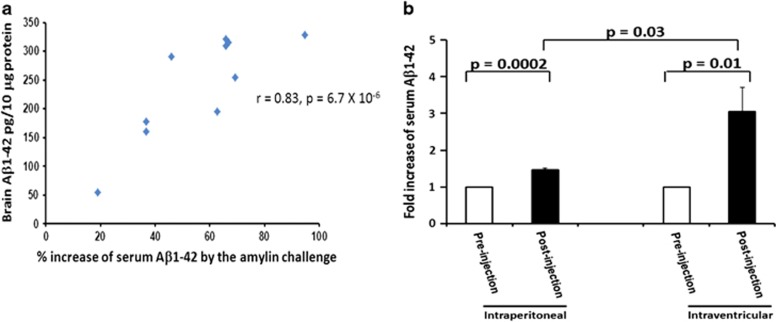

To further determine that the surge of Aβ in serum provoked by amylin challenge reflected the Aβ pathology in the brain, we repeated the experiment using 5XFAD mice, which have abundant Aβ1–42 but little or no Aβ1–40 in the brain. We found that a single i.p. injection of amylin into 5XFAD mice resulted in an increased level of Aβ1–42 but not of Aβ1–40 in serum (Figure 3c). We then assessed the response in another APP mouse line, which carries the knock-in Dutch mutation of APP in the context of Swedish and London mutations and mainly produces Aβ1–40 but little Aβ1–42 in the brain. Amylin challenge in these mice provoked a surge of Aβ1–40 but not of Aβ1–42 in the blood (Figure 3d). Using 5XFAD mice of different ages, we found that peripheral amylin injection resulted in increases in serum Aβ levels that were proportionate to the levels of Aβ in the brain (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Change in serum Aβ levels induced by amylin challenge and Aβ pathology in the brain. Serum samples were isolated before and after 5XFAD mice, which were at different ages, were challenged by a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of amylin. The mice were killed immediately after the amylin challenge procedure, and the brain protein was extracted. The percentage of changes in serum Aβ1–42 induced by a single i.p. injection of amylin significantly correlated with the amounts of Aβ1–42 in their brains (r=0.83, P=6.7 × 10−6) (a). Amylin-induced serum Aβ1-42 changes induced by i.p. injection or intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection in the 5XFAD mice were compared (b). Higher levels of increased serum Aβ1–42 induced by i.c.v. injection of amylin than by i.p. injection of amylin were observed (P=0.03) in these mice.

Despite the fact that all of the APP transgenic mice studied here express substantial APP in the brain, they probably express little APP in peripheral tissues. To confirm that the source of the Aβ surge in serum is the brain, and is mediated by the effects of amylin on the brain, we assessed the surge of Aβ in serum following a single injection of amylin into the brain ventricles of these APP mice. I.c.v. injection of amylin (200 μg kg−1) provoked a much greater surge of Aβ in serum than a peripheral i.p. injection of amylin (200 μg kg−1) in the same APP mice (Figure 4b). These data suggest that because peripherally administered amylin or pramlintide must cross the BBB to influence the amyloid pathology in the brain, the effect of i.p. injection was not as pronounced as that produced by i.c.v. injection.

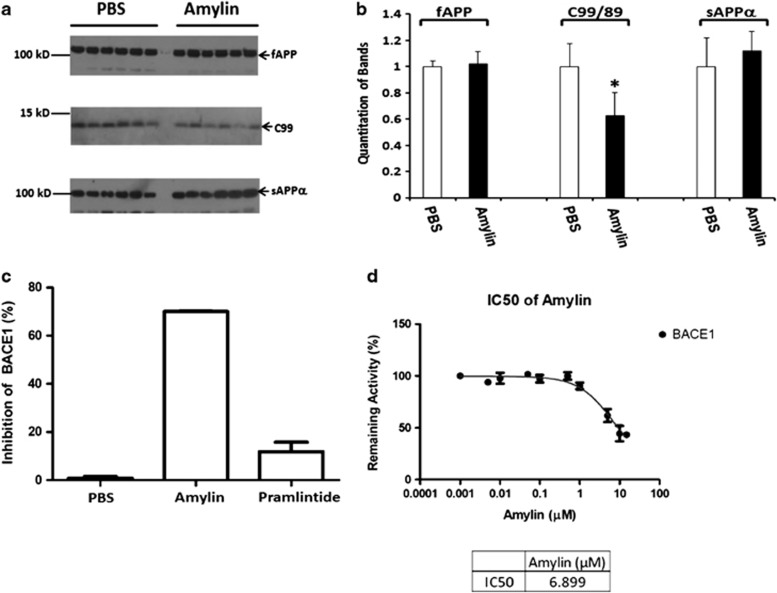

Amylin inhibits BACE1 activity

We next examined the effects of amylin on APP expression and processing in the brain of Tg2576 mice. There were no observable differences between the control and treatment groups in the expression levels of APP mRNA (Supplementary Figure S2) or in the levels of full-length APP protein or in the levels of one form of secreted APP (sAPPα) in brain extracts (Figure 5a). However, compared with controls, mice treated with amylin had lower levels of the APP processing fragments C9932 (Figures 5a and 5b). The β-site APP cleaving enzyme (BACE1) is the key protease initiating the generation of C99 by cleaving APP leading to further production of Aβ.33,34 In an in vitro assay using purified BACE1, we found that amylin significantly inhibited BACE1 activity (70%) in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 5c and 5d). The IC50 for BACE1 inhibition by amylin was 6.9 μM. Surprisingly, pramlintide, which only has 3 amino-acid differences from amylin, showed little or no ability to inhibit BACE1 activity in this assay and did not reduce C99 levels compared with saline-treated controls (data not shown). As pramlintide treatment reduced Aβ in the brain to the same extent as amylin treatment (Figure 2), these data suggest that inhibition of BACE1 is not the major mechanism by which amylin class peptides reduce the Aβ burden in the brain.

Figure 5.

Characterization of the effect of amylin on amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing and BACE1. (a) Detection of full-length APP (fAPP) and APP processed products by 6E10 antibody in western blotting in brain homogenates from Tg2576 mice treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or amylin (n=6 per group), and (b) quantitation of the results (mean±s.e.) are shown. Although there were no differences in the levels fAPP and secreted APP cleaved by α secretase (sAPPα) between PBS control and the amylin treatment, there was an increase in C99 fragment from APP cleaved by BACE1 in the brains treated with amylin compared with PBS treatment (*P=0.004). (c) In vitro assay using purified BACE1 showed that amylin significantly inhibited BACE1 activity, but pramlintide had little inhibition for BACE1. The concentration of amylin necessary to inhibit 50% BACE1 activity (IC50) in this assay is 6.9 μM (d).

The association between amylin and Aβ in human plasma

If these observations made in mice that exogenously and peripherally added amylin removed Aβ out of the brain into the blood causing increased levels of both amylin and Aβ in blood were implied to the naturally occurring amylin and applicable to human AD patients, we should be able to see a positive association between amylin and Aβ in blood in humans. We assessed amylin and Aβ levels in plasma samples from a human study with diagnoses35 and did find that amylin was positively associated with Aβ1–42 as well as Aβ1–40 in plasma after adjusting for the confounders (Supplementary Table S3). After dividing the subjects into subgroups based on the diagnoses and using univariate analysis, we found that plasma amylin was associated with Aβ1–42 (r=+0.52, P=0.0004) and only tended to be associated with Aβ1–40 (r=+0.29, P=0.06) among AD subjects (n=42) (Table 1). The correlations between plasma amylin and Aβ1–42 (r=+0.73, P=0.001) or Aβ1–40 (r=+0.58, P=0.02) were stronger among the elderly with amnestic MCI (n=16), a prodromal stage of AD. In contrast, there was no correlation between plasma amylin and either form of Aβ among the elderly who had normal cognition (n=145). There were no differences in the concentrations of amylin and Aβ among the three subgroups, and these relationships between amylin and Aβ were also not found among patients with other types of dementia and non-amnestic MCI (data not shown).

Table 1. Correlations between Aβ and amylin in plasma in humans.

| Diagnoses | Controls, N=145 | Amnestic, MCI N=16 | Alzheimer's disease, N=42 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year, mean±s.d.* | 72.3±8.0 | 75.7±8.7 | 80.5±8.1 |

| MMSE, mean±s.d.* | 27.1±2.6 | 26.4±2.5 | 22.2±3.3 |

| Log10 amylin with Log10 Aß1-42 | r=+0.06, P=0.46 | r=+0.73, P=0.001 | r=+0.52, P=0.0004 |

| Log10 amylin with Log10 Aß1-40 | r=+0.02, P=0.83 | r=+0.58, P=0.02 | r=+0.29, P=0.06 |

Abbreviations: MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, Mini Mental State Exam.

Using analysis of variance, age and average MMSE scores in the subgroups of the controls, amnestic MCI and Alzheimer's disease are compared. *P<0.0001. Pearson's analyses were performed to determine the correlation coefficient between plasma Aβ40 or Aβ42 and amylin in different subgroups: the controls, amnestic MCI and Alzheimer's disease. P-values for statistical significance are shown.

Discussion

These data indicate that long-term peripheral amylin treatment improved learning and memory in the AD mice. Reducing neurotoxic Aβ species, especially monomers and small oligomers,36 rather than decreasing plaque burden per se, is probably more critical for and relevant to cognitive improvement by the treatment of AD in our experiments. Indeed, one study shows that hyper-aggregation of Aβ is even protective for neurodegeneration.37 In addition, these Aβ species in the AD brain may block the ability of amylin to bind to its receptor11 and lead to the loss or reduction of amylin's activities, which are essential for the brain.3, 4, 5, 6 Another example of the loss of function in AD is that some early onset AD cases may manifest in cognitive decline as a result of the loss of presenilin function.38 The drug inhibiting presenilin function worsens cognition in AD patients.39

Our study and others argue for a therapeutic application of amylin class peptides for AD through the following mechanism. First, amylin and pramlintide enhance the removal of Aβ from the brain and its transfer into the blood, probably through their effects on cerebral vasculature as amylin has been shown to improve cerebral vasculature.5 Dysfunction of the BBB, decreased cerebral blood flow and impaired vascular clearance of Aβ from the brain are all thought to contribute to AD pathogenesis.40 Solanezumab, an immune drug that also removes Aβ from the AD brain into blood,41 has been shown to delay cognitive decline in those who have an early stage of AD.42 Induced removal of Aβ from the brain into the blood by the amylin class peptides also could be used in a challenge test to specifically reflect and diagnose AD pathology in the brain.

Second, despite the fact that BACE is considered to be a prime target for developing the drugs for AD, and that BACE1 knockout in the APP transgenic mice significantly reduce the amyloid burden in the brain43 and are viable,44 most peptide-based BACE1 inhibitors failed as drugs for AD owing to their inability to pass through the BBB.45 Our study shed some light that amylin, but not pramlintide, is a BACE1 inhibitor crossing the BBB. However, unlike other published BACE1 inhibitors, which decrease Aβ in CSF and blood,46,47 treatment with amylin increased the concentrations of Aβ1-42 in CSF and blood. Additionally, although pramlintide was unable to inhibit BACE1, pramlintide equally reduced amyloid pathology in the brain like amylin. These data suggest that enhancing Aβ removal from the brain and translocation of Aβ into the blood, rather than inhibition of BACE1, is the major mechanism by which amylin class peptides reduce the Aβ burden in the brain in our study.

Third, evidence from numerous studies suggests other benefits of amylin class peptides for AD. As brain imaging studies have demonstrated perturbed cerebral glucose metabolism in the AD brain,48 glucose metabolism should be a target for drug development for AD. Because of their ability to cross the BBB, both amylin and pramlintide could potentially improve glucose metabolism in the brain.49 Additionally, several studies show that amylin and its analogs have an effect to inhibit the formation of Aβ aggregation and reduces cell death caused by the Aβ aggregates,15, 16, 17, 18, 19 which is a key element in AD pathogenesis. As in type 2 diabetes large amounts of amylin can aggregate in the pancreas, amylin itself may not be suitable to treat AD in patients who also have diabetes. It is noteworthy that pramlintide does not form aggregates and has become an effective and safe drug for diabetes.7 Our results certainly suggest a therapeutic potential of pramlintide for AD and warrant a clinical trial in AD with off-label use.

When exogenous and synthetic amylin was i.p injected into mice in our experiments, it increased the level of amylin in the blood as expected while also increasing the blood levels of Aβ through translocating Aβ out of the brain into the blood. If endogenous pancreatic amylin in the body has the same role in regulating Aβ in brain, amylin and Aβ in blood should be positively associated. Thus the finding of a positive association between amylin and Aβ, especially Aβ1-42, in plasma in AD and amnestic MCI patients supports the relevance of our findings in mice. Other drugs targeting Aβ clearance and removing Aβ out of the brain were shown to be effective for prodromal or early stage of AD.50 However, there is broad agreement that more therapeutic avenues need to be explored in addition to targeting Aβ for the treatment of AD. Amylin class drugs not only remove Aβ from the brain, as demonstrated by our study, but can also improve glucose metabolism51 and cerebrovasculature4,5 in the AD brain. Some amylin analogs may be BACE1 inhibitors in the brain. Based on their multiple effects, we propose that the amylin class peptides have potential to become a new avenue as a challenge test for diagnosis of amnestic MCI and AD and as a therapeutic for the disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Benjamin Wolozin and Dr Susan Leman for critically discussing the data and the manuscript preparation. We thank Dr Dennis J Selkoe for providing the antibodies against Aβ, Dr Tarik Haydar and Dr Pietro Cottone for sharing their equipment for this study and Ruiying Zhu and Stephen Avery for their technical support. We also thank the NAME study staff and the Boston homecare agencies for their hard work and acquisition of subjects. This work was supported by Grants from NIA, AG-022476 and Ignition Award (to WWQQ) and BU ADC pilot grant (to HZ). Support was also provided through P30 AG13864 (to NK).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Molecular Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/mp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Banks WA, Kastin AJ. Differential permeability of the blood-brain barrier to two pancreatic peptides: insulin and amylin. Peptides. 1998;19:883–889. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(98)00018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson M, Herrington MK, Reidelberger RD, Permert J, Arnelo U. Comparison of the effects of chronic central administration and chronic peripheral administration of islet amyloid polypeptide on food intake and meal pattern in the rat. Peptides. 2007;28:1416–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth JD, Roth JD, Erickson MR, Chen S, Parkes DG. Amylin and the regulation of appetite and adiposity: recent advances in receptor signaling, neurobiology and pharmacology GLP-1R and amylin agonism in metabolic disease: complementary mechanisms and future opportunities. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20:8–13. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32835b896f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westfall TC, Curfman-Falvey M. Amylin-induced relaxation of the perfused mesenteric arterial bed: meditation by calcitonin gene-related peptide receptors. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;26:932–936. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199512000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvinsson L, Goadsby PJ, Uddman R. Amylin: localization, effects on cerebral arteries and on local cerebral blood flow in the cat. ScientificWorldJournal. 2001;1:168–180. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2001.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevaskis JL, Turek VF, Wittmer C, Griffin PS, Wilson JK, Reynolds JM, et al. Enhanced amylin-mediated body weight loss in estradiol-deficient diet-induced obese rats. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5657–5668. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillay K, Govender P. Amylin uncovered: a review on the polypeptide responsible for type II diabetes. Biomed Res Int. 2013;826706:1–17. doi: 10.1155/2013/826706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zraika S, Hull RL, Verchere CB, Clark A, Potter KJ, Fraser PE, et al. Toxic oligomers and islet beta cell death: guilty by association or convicted by circumstantial evidence. Diabetologia. 2010;53:1046–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1671-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogwerf BJ, Doshi KB, Diab D. Pramlintide, the synthetic analogue of amylin: physiology, pathophysiology, and effects on glycemic control, body weight, and selected biomarkers of vascular risk. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4:355–362. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YA, Ittner LM, Lim YL, Gotz J. Human but not rat amylin shares neurotoxic properties with Abeta42 in long-term hippocampal and cortical cultures. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2188–2194. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu W, Ruangkittisakul A, MacTavish D, Shi JY, Ballanyi K, Jhamandas JH, et al. Amyloid beta (Abeta) peptide directly activates amylin-3 receptor subtype by triggering multiple intracellular signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:18820–18830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.331181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, W Q, Walsh DM, Ye Z, Vekrellis K, Zhang J, Podlisny MB, et al. Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates extracellular levels of amyloid beta-protein by degra dation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32730–32738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RG, Hamel FG, Duckworth WC. An insulin-degrading enzyme inhibitor decreases amylin degradation, increases amylin-induced cytotoxicity, and increases amyloid formation in insulinoma cell cultures. Diabetes. 2003;52:2315–2320. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.9.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Joachimiak A, Rosner MR, Tang WJ. Structures of human insulin-degrading enzyme reveal a new substrate recognition mechanism. Nature. 2006;443:870–874. doi: 10.1038/nature05143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan LM, Velkova A, Tatarek-Nossol M, Andreetto E, Kapurniotu A. IAPP mimic blocks Abeta cytotoxic self-assembly: cross-suppression of amyloid toxicity of Abeta and IAPP suggests a molecular link between Alzheimer's disease and type II diabetes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:1246–1252. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellin D, Yan LM, Kapurniotu A, Winter R. Suppression of IAPP fibrillation at anionic lipid membranes via IAPP-derived amyloid inhibitors and insulin. Biophys Chem. 2010;150:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreetto E, Yan LM, Caporale A, Kapurniotu A. Dissecting the role of single regions of an IAPP mimic and IAPP in inhibition of Abeta40 amyloid formation and cytotoxicity. Chembiochem. 2011;12:1313–1322. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan LM, Velkova A, Kapurniotu A.Molecular characterization of the hetero-assembly of beta-amyloid peptide with islet amyloid polypeptide Curr Pharm Des 2013(e-pub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yan LM, Velkova A, Tatarek-Nossol M, Rammes G, Sibaev A, Andreetto E, et al. Selectively N-methylated soluble IAPP mimics as potent IAPP receptor agonists and nanomolar inhibitors of cytotoxic self-assembly of both IAPP and Abeta40. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:10378–10383. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K, Barisone GA, Diaz E, Jin LW, DeCarli C, Despa F, et al. Amylin deposition in the brain: a second amyloid in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2013;74:517–526. doi: 10.1002/ana.23956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, Maus E, Shao P, Craft J, et al. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer's disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10129–10140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, Ueberham U, Brückner MK, Seeger G, Arendt T, Gärtner U, et al. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Broeckhoven C, Haan J, Bakker E, Hardy JA, Van Hul W, Wehnert A, et al. Amyloid beta protein precursor gene and hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis (Dutch) Science. 1990;248:1120–1122. doi: 10.1126/science.1971458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Acquaviva J, Ramachandran P, Boskovitz A, Woolfenden S, Pfannl R, et al. Oncogenic EGFR signaling cooperates with loss of tumor suppressor gene functions in gliomagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2712–2716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813314106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youmans KL, Tai LM, Nwabuisi-Heath E, Jungbauer L, Kanekiyo T, Gan M, et al. APOE4-specific changes in Abeta accumulation in a new transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:41774–41786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.407957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu WQ, Summergrad P, Folstein M. Plasma Abeta42 levels and depression in the elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:930. doi: 10.1002/gps.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Steffens DC, Au R, Folstein M, Summergrad P, Yee J, et al. Amyloid-associated depression: a prodromal depression of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:542–550. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janus C, Pearson J, McLaurin J, Mathews PM, Jiang Y, Schmidt SD, et al. A beta peptide immunization reduces behavioural impairment and plaques in a model of Alzheimer's disease transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2000;408:979–982. doi: 10.1038/35050110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn CA, Stachel SJ, Li YM Rush DM, Steele TG, Chen-Dodson E, et al. Identification of a small molecule nonpeptide active site beta-secretase inhibitor that displays a nontraditional binding mode for aspartyl proteases. J Med Chem. 2004;47:6117–6119. doi: 10.1021/jm049388p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer F, Molinari M, Bodendorf U, Paganetti P. The disulphide bonds in the catalytic domain of BACE are critical but not essential for amyloid precursor protein processing activity. J Neurochem. 2002;80:1079–1088. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassar R, Bennett BD, Babu-Khan S, Kahn S, Mendiaz EA, Denis P, et al. Beta-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science. 1999;286:735–741. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan R, Bienkowski MJ, Shuck ME, Miao H, Tory MC, Pauley AM, et al. Membrane-anchored aspartyl protease with Alzheimer's disease beta-secretase activity. Nature. 1999;402:533–537. doi: 10.1038/990107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Bhadelia R, Liebson E, Bergethon P, Folstein M, Zhu JJ, et al. The relationship between plasma amyloid-beta peptides and the medial temporal lobe in the homebound elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:593–601. doi: 10.1002/gps.2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, Brett FM, et al. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14:837–842. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Paulsson JF, Blinder P, Burstyn-Cohen T, Du D, Estepa G, et al. Reduced IGF-1 signaling delays age-associated proteotoxicity in mice. Cell. 2009;139:1157–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Kelleher RJ., 3rd The presenilin hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: evidence for a loss-of-function pathogenic mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:403–409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608332104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doody RS, Raman R, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S, et al. A phase 3 trial of semagacestat for treatment of Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:341–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagare AP, Bell RD, Zlokovic BV. Neurovascular dysfunction and faulty amyloid beta-peptide clearance in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:1–17. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMattos RB, Bales KR, Cummins DJ, Paul SM, Holtzman DM. Brain to plasma amyloid-beta efflux: a measure of brain amyloid burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Science. 2002;295:2264–2267. doi: 10.1126/science.1067568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uenaka K, Nakano M, Willis BA, Friedrich S, Ferguson-Sells L, Dean RA, et al. Comparison of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, and tolerability of the amyloid beta monoclonal antibody solanezumab in Japanese and white patients with mild to moderate alzheimer disease. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2012;35:25–29. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e31823a13d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Bolon B, Kahn S, Bennett BD, Babu-Khan S, Denis P, et al. Mice deficient in BACE1, the Alzheimer's beta-secretase, have normal phenotype and abolished beta-amyloid generation. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:231–232. doi: 10.1038/85059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberds SL, Anderson J, Basi G, Bienkowski MJ, Branstetter DG, Chen KS, et al. BACE knockout mice are healthy despite lacking the primary beta-secretase activity in brain: implications for Alzheimer's disease therapeutics. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1317–1324. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.12.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassar R, Kovacs DM, Yan R, Wong PC. The beta-secretase enzyme BACE in health and Alzheimer's disease: regulation, cell biology, function, and therapeutic potential. J Neurosci. 2009;29:12787–12794. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3657-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain I, Hawkins J, Harrison D, Hille C, Wayne G, Cutler L, et al. Oral administration of a potent and selective non-peptidic BACE-1 inhibitor decreases beta-cleavage of amyloid precursor protein and amyloid-beta production in vivo. J Neurochem. 2007;100:802–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert JS. Progress in the development of beta-secretase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease. Prog Med Chem. 2009;48:133–161. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6468(09)04804-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KA, Fox NC, Sperling RA, Klunk WE. Brain imaging in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006213. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz O, Brock B, Rungby J. Amylin agonists: a novel approach in the treatment of diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53:S233–S238. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomone S, Caraci F, Leggio GM, Fedotova J, Drago F. New pharmacological strategies for treatment of Alzheimer's disease: focus on disease modifying drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:504–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevaskis JL, Griffin PS, Wittmer C, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Brunt EM, Dolman CS, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonism improves metabolic, biochemical, and histopathological indices of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G762–G772. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00476.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.