Abstract

Objective:

Despite substantial attention being paid to the health benefits of moderate alcohol intake as a lifestyle, the acute effects of alcohol on psychomotor and working memory function in older adults are poorly understood.

Method:

The effects of low to moderate doses of alcohol on neurobehavioral function were investigated in 39 older (55–70 years; 15 men) and 51 younger (25–35 years; 31 men) social drinkers. Subjects received one of three randomly assigned doses (placebo, .04 g/dl, or .065 g/dl target breath alcohol concentration). After beverage consumption, they completed the Trail Making Test Parts A and B and a working memory task requiring participants to determine whether probe stimuli were novel or had been presented in a preceding set of cue stimuli. Efficiency of working memory task performance was derived from accuracy and reaction time measures.

Results:

Alcohol was associated with poorer Trail Making Test Part B performance for older subjects. Working memory task results suggested an Age × Dose interaction for performance efficiency, with older but not younger adults demonstrating alcohol-related change. Directionality of change and whether effects on accuracy or reaction time drove the change depended on the novelty of probe stimuli.

Conclusions:

This study replicates previous research indicating increased susceptibility of older adults to moderate alcohol-induced psychomotor and set-shifting impairment and suggests such susceptibility extends to working memory performance. Further research using additional tasks and assessing other neuropsychological domains is needed.

Potential health benefits associated with regular moderate drinking (i.e., ≤ 2 drinks/day for men or ≤ 1 drink/day for women; United States Department of Agriculture & United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2010) have been the focus of several large-scale studies (Djoussé et al., 2009; Inoue et al., 2012). However, the acute neurobehavioral effects of subintoxicating blood alcohol concentrations (BACs) associated with moderate drinking sessions (i.e., < .08 g/dl) have received relatively little attention. A limited literature suggests that top-down attentional control, visual perception, and inhibitory function may be vulnerable to impairment at low to moderate BACs (Breitmeier et al., 2007; de Wit et al., 2000; Dougherty et al., 2008; Fillmore, 2007; Friedman et al., 2011; Holloway, 1994; Oscar-Berman and Marinković, 2007; Reed et al., 2012).

Most work on acute low to moderate dose effects has focused on endpoint outcomes (e.g., completion time or accuracy) that may not be optimally sensitive to subtle deficits as opposed to more sensitive process-oriented constructs (Kaplan, 1988). Our work and others’ have used the construct of cognitive efficiency, conceptualized as the ability to work quickly and accurately at the same time, to address this concern. For example, both chronic alcoholism and normal aging are associated with deficits in cognitive efficiency (Carriere et al., 2010; Fillmore, 2007; Nixon, 1999). Literature reviewed by Fillmore (2007) suggests that moderate alcohol doses may also undermine cognitive efficiency.

Another limitation of the larger literature is that studies of acute moderate alcohol effects have included primarily young adults (Dougherty et al., 2008; Reed et al., 2012). However, many older adults report moderate alcohol consumption (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011). Aging-related changes in body composition (e.g., reductions in lean body mass) may influence alcohol distribution and pharmacokinetics (Davies and Bowen, 1999; Gilbertson et al., 2009). Furthermore, aging is often associated with subclinical cognitive decrements, including declines in processing speed and deficits in suppression of attention to irrelevant stimuli (Charness, 2000; Gazzaley et al., 2005). Taken together, these changes constitute a mechanism by which age may modulate the neurobehavioral effects of moderate alcohol intake. Indeed, research in our laboratory using the Trail Making Test (TMT; Reitan and Wolfson, 1993) suggests that adults 50–75 years of age demonstrate deficits in psychomotor and set-shifting performance at BACs at which adults ages 25–35 years do not (i.e., ∼.05 g/dl; Gilbertson et al., 2009). Recent work using a covert attention task (Luck et al., 1994; Posner, 1980) found evidence for speed/accuracy tradeoffs in older, but not younger, adults at BACs ∼.05 g/dl (Sklar et al., 2012). In addition, older adults show disruption of neurophysiological indices of working memory function (i.e., P300 amplitude and latency) at this level, but younger adults do not (Lewis et al., 2013). These findings suggest that further work is needed to (a) clarify potential age-dependent thresholds for dose effects on performance and (b) specify whether behavioral indices may be affected by age and alcohol interactions.

The current study was designed to address these issues. Specifically, we included three target BAC levels: 0 (placebo), .04 g/dl, and .065 g/dl. We administered a visual working memory task involving top-down attentional control (Gazzaley et al., 2005). The TMT was also included for comparison with previous work (Reitan and Wolfson, 1993). Based on earlier studies (Gilbertson et al., 2009), we anticipated (a) age-related deficits on TMT Part A, a simple psychomotor task; (b) that the .04 g/dl dose level would result in faster TMT Part A completion times for younger adults but no significant dose effects for older adults; and (c) that both older age and alcohol dose would contribute to slower completion of the TMT Part B. In addition, we predicted that older adults’ sensitivity to alcohol’s negative effects would extend to the working memory task. We posed as an empirical question whether detrimental effects of age and alcohol on working memory efficiency would be attributable to changes in accuracy and/or reaction time (RT).

Method

Study design

The study used a 2 (age: younger, 25–35; older, 55–70) × 3 (alcohol dose: placebo; low [0.04 g/dl]; and moderate [0.065 g/dl]) double-blind, placebo-controlled, factorial design. Because our focus was on age and alcohol interactions, the upper cutoff for older adults was selected to minimize potential confounds associated with age-related cognitive decline. The University of Florida Health Science Center Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Screening

Community outreach occurred through flyers and radio/print advertisements. Interested individuals called the laboratory and were informed of basic inclusionary criteria, including (a) being between ages 25 and 35 or 55 and 70 years, (b) being a nonsmoker, (c) being in good physical health, (d) having at least a high school diploma but not more than a master’s degree, (e) having no significant history of head injury or unconsciousness, (f) having previous experience consuming alcohol, and (g) having no history of problems with alcohol or other substances. If, after hearing the criteria, individuals remained interested, they were scheduled for a screening session in the laboratory. Written informed consent was obtained before any data collection.

Basic screening measures included demographic assessments, drug and alcohol use histories, and state anxiety index (Spielberger, 1983). Participants also completed age-appropriate measures of depressive symptomatology (younger: Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd Ed. [BDI-II]; older: Geriatric Depression Scale [GDS]) (Beck et al., 1996; Yesavage et al., 1982–1983). Average daily consumption of absolute ethanol in ounces over the 6 months before screening (quantity–frequency index or QFI) was determined (Cahalan et al., 1969). Men were included if they had a QFI of ≤ 1.2 (∼2 drinks/day); women were included if they had a QFI of ≤ 0.6 (∼1 drink/day). Individuals completing screening were paid $15.

Persons continuing to qualify following screening provided a self-report of their medical history. Probabilistic psychiatric diagnoses were assessed with the computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Robins et al., 1995). Exclusionary psychiatric criteria included (a) current or lifetime diagnosis of alcohol or other substance dependence, including nicotine; (b) lifetime diagnosis of any psychotic disorder; and (c) current diagnosis of major depressive disorder (or lifetime diagnosis if electroconvulsive therapy was used for treatment). In addition, a history of serious medical illness—including uncontrolled type 2 diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension, epilepsy, HIV/AIDS, past incidence of powerful electric shock, prolonged periods of unconsciousness, or skull fracture—was exclusionary. Women who were pregnant or breastfeeding were also disqualified. Individuals who completed the interview process received $37.50.

Prescription medication use

To enhance ecological validity and feasibility of recruitment, use of common prescription and over-the-counter medications was allowed provided the drug(s) did not contra-indicate alcohol use. As expected, more older than younger adults reported medication use (61% vs. 25%, respectively). Commonly reported medications included birth control (55% of younger women), nonopioid analgesics (18.4% of older adults), and cholesterol medications (15.8% of older adults). A minority of participants had been stabilized for at least 3 months on selective serotonin or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (2.0% of younger adults and 7.9% of older adults), antihypertensives (13.2% of older adults), or hormone replacement (8.3% of older women).

Laboratory phase

Laboratory sessions typically began at 9:00 a.m. (range: 8:00–10:30 a.m. because of travel, etc.). Subjects were asked to (a) fast for 4 hours before their scheduled session, (b) take normal morning medications, and (c) avoid over-the-counter allergy or sinus medications on the morning of testing. Subjects were questioned regarding their compliance with these guidelines before study sessions. In addition, subjects confirmed that their use of medications was unchanged. Those reporting noncompliance or change in medication were rescheduled. Subjects provided separate written informed consent for the laboratory session before any study procedures.

Recent abstinence from alcohol consumption was confirmed using standard instruments (Intoxylizer 400PA; CMI, Inc., Owensboro, KY). Initial breath alcohol concentrations (BrACs) were required to be .000 g/dl. Subjects were required to produce a negative urine drug screen (i.e., benzodiazepines, amphetamines, cocaine, marijuana, and opiates) and pregnancy test (women of childbearing potential only). Subjects consumed a light snack (∼220 calories) approximately 1 hour before alcohol administration.

Alcohol administration

The quantity of medical-grade alcohol (100% ethanol) necessary to achieve assigned BrACs was calculated using sex-defined modifications of the Widmark formula (Watson et al., 1981). Alcohol was mixed with 366 ml of vehicle (ice-cold, sugar-free lemon-lime soda) and administered according to standard procedures (Fillmore et al., 2000). Placebo beverages contained only vehicle. Drinks and serving trays were misted with alcohol to enhance placebo effectiveness. Beverages were split into two servings consumed by the participant within 5 minutes. BrAC measurements were obtained 10, 25, 60, and 75 minutes after beverage administration. Twenty-five minutes after alcohol administration, subjects consumed a “booster” beverage containing half their initial alcohol dose if their BrAC was less than or equal to half of target. Five subjects (two older) received an active booster. All other subjects received a placebo booster containing only vehicle. Subjective intoxication was assessed before and after each task using a 10-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 10 = most in my life). Following testing (∼2.5 hours), subjects were transported home when their BrAC was ≤ .01 g/dl.

Trail Making Test

The TMT (Reitan and Wolfson, 1993), completed by subjects 10 minutes after alcohol consumption, has two parts. Part A is a simple psychomotor task requiring subjects to connect 24 numbered circles in sequence. Part B is more difficult, involving the connection of circles with alternating numbers and letters, engaging set-shifting and working memory processes. Time to complete both parts was recorded. The TMT typically required less than 5 minutes to complete.

Working memory task

The working memory task (Gazzaley et al., 2005) consisted of three trial blocks differing by instructional set and was completed 25 minutes after beverage administration and immediately following booster administration. Each of the 20 trials per block included two face and two scene “cue” stimuli presented in pseudo-random order to ensure that subjects could not anticipate their sequence. Cue stimuli were grayscale and presented for 800 ms each with a 200-ms interstimulus interval. After a 9-second delay, a probe image was presented. Subjects responded about whether the probe image was present in the preceding set (50% probability/trial). Subjects completed trial blocks with all three instruction sets in a counterbalanced order. In one, subjects were instructed to remember faces and ignore scenes. In another, subjects remembered scenes and ignored faces. In a control condition, subjects viewed cue faces and scenes passively and then indicated the direction of an arrow replacing the probe image via button press. Accuracy and RT were collected for each trial. From these, the proportion of “hits” (correct responses to previously presented probes) and “correct rejections” (correct response to a previously absent [i.e., novel] probe) and their average RTs were derived. Efficiency ratios (accuracy/RT), which were of primary interest, were then constructed for both trial types. Although reliability and validity measures are not available for behavioral outcomes from this task, some precedent for consistent performance across studies for this task has been established (Anguera and Gazzaley, 2012). The task required approximately 25 minutes to complete.

Analysis strategy

SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. To characterize study groups, demographic variables shared by older and younger participants were subjected to 2 (age group) × 3 (alcohol dose) analysis of variance (ANOVA) (SAS PROC GLM; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Follow-up t tests were conducted to characterize detected interactions. One-way ANOVA (alcohol dose: placebo, .04 g/dl, .065 g/dl) was conducted to determine whether participants differed on age group–specific variables. Follow-up t tests were conducted to characterize detected dose effects. As a conservative test for between-group differences in descriptive variables, no corrections for type I error were applied. Potential confounding relationships between demographic variables and behavioral measures were examined using Pearson’s r correlation matrices. Using this approach, six outcome variables (efficiency, accuracy, and RT for hits and correct rejections) were correlated with each demographic and affective variable. Because of the large number of simultaneous tests, Bonferroni corrections were applied, resulting in a significance threshold α < .008 (i.e., 0.05 / 6 simultaneous tests per demographic/affective variable). No significant correlations were detected.

Descriptive univariate statistics indicated that completion times for both parts of the TMT, but neither hit nor correct rejection efficiency on the working memory task, were skewed and kurtosed. TMT completion times were log-transformed for analyses to correct the distribution (Tabachnick and Fidell, 1989). Because of the relative simplicity of the “passive viewing” instruction set in the working memory task, almost all participants achieved 100% accuracy. In addition, RTs were significantly faster in the passive viewing instruction set than in both the “remember face” and “remember scene” instructions (ps < .0001). Thus, data from the passive viewing instruction set were not included in behavioral analyses.

Hypotheses regarding Age × Alcohol interactions for TMT performance were tested using 2 (age group) × 3 (dose group) ANOVA. Preliminary analyses of working memory task data revealed a significant three-way interaction of age group, dose, and trial type—repeated: hit vs. correct rejection, F(2, 84) = 5.83, p = .004. Thus, 2 (age group) × 3 (dose group) × 2 (repeated: instruction set [remember face vs. remember scene]) ANOVA was conducted separately for hits and correct rejections. Significant or trend-level (i.e., p < .10) Age × Dose interactions were characterized by performing comparisons of dose effects (i.e., t tests) within each age group. Relevant between-group comparisons were pre-planned (i.e., dose effects within each age group). To minimize type I error, extraneous comparisons (e.g., age effects at each dose level) were excluded, and two-tailed t tests were used despite our directional hypotheses. Given the nature of hypotheses and planned comparisons, and to better characterize empirical questions, additional type I correction was not applied. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) are reported for significant or trend-level comparisons to provide context for the results.

Results

Participants

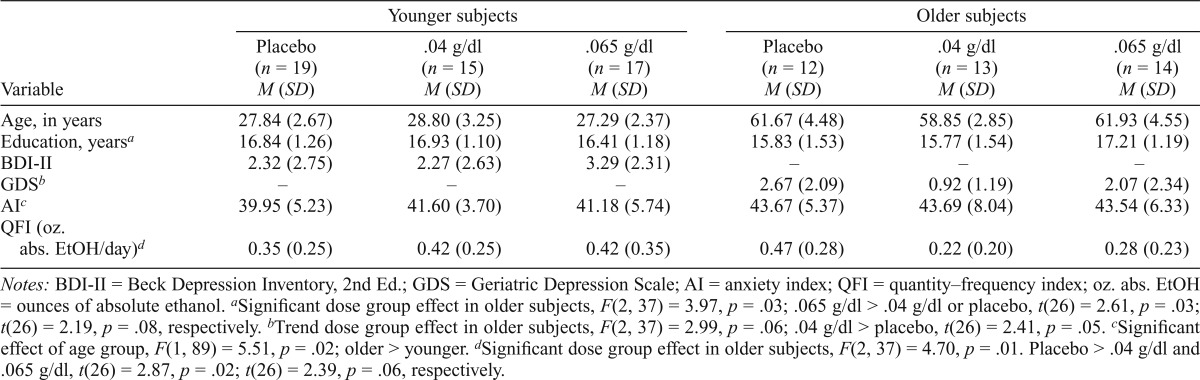

Older (n = 39, 15 men) and younger (n = 51, 31 men) community-dwelling moderate drinkers were recruited for the study. Ninety-one percent were White, 4% were African American, and 4% reported another race or multiple races. Eleven percent were Hispanic. Means of demographic, affective, and alcohol-related variables by age group and dose assignment are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and affective variables

| Variable | Younger subjects |

Older subjects |

||||

| Placebo (n = 19) M (SD) | .04 g/dl (n = 15) M (SD) | .065 g/dl (n = 17) M (SD) | Placebo (n = 12) M (SD) | .04 g/dl (n = 13) M (SD) | .065 g/dl (n = 14) M (SD) | |

| Age, in years | 27.84 (2.67) | 28.80 (3.25) | 27.29 (2.37) | 61.67 (4.48) | 58.85 (2.85) | 61.93 (4.55) |

| Education, yearsa | 16.84 (1.26) | 16.93 (1.10) | 16.41 (1.18) | 15.83 (1.53) | 15.77 (1.54) | 17.21 (1.19) |

| BDI-II | 2.32 (2.75) | 2.27 (2.63) | 3.29 (2.31) | – | – | – |

| GDSb | – | – | – | 2.67 (2.09) | 0.92 (1.19) | 2.07 (2.34) |

| AIc | 39.95 (5.23) | 41.60 (3.70) | 41.18 (5.74) | 43.67 (5.37) | 43.69 (8.04) | 43.54 (6.33) |

| QFI (oz. abs. EtOH/day)d | 0.35 (0.25) | 0.42 (0.25) | 0.42 (0.35) | 0.47 (0.28) | 0.42 (0.35) | 0.28 (0.23) |

Notes: BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd Ed.; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; AI = anxiety index; QFI = quantity–frequency index; oz. abs. EtOH = ounces of absolute ethanol.

Significant dose group effect in older subjects, F(2, 37) = 3.97, p = .03; .065 g/dl > .04 g/dl or placebo, t(26) = 2.61, p = .03; t(26) = 2.19, p = .08, respectively.

Trend dose group effect in older subjects, F(2, 37) = 2.99, p = .06; .04 g/dl > placebo, t(26) = 2.41, p = .05.

Significant effect of age group, F(1, 89) = 5.51, p = .02; older > younger.

Significant dose group effect in older subjects, F(2, 37) = 4.70, p = .01. Placebo > .04 g/dl and .065 g/dl, t(26) = 2.87, p = .02; t(26) = 2.39, p = .06, respectively.

Education level

There was no significant main effect of age for years of education (p > .10), although a significant Age Group × Dose interaction was detected, F(2, 84) = 5.37, p = .006. Follow-up analyses revealed that years of education were equivalent across dose groups for younger adults, but that older adults at the placebo and .04 g/dl dose levels had significantly fewer years than those at the .065 g/dl level, t(23) = 2.72, p = .008, and t(25) = 2.91, p = .005, respectively. All other effects were nonsignificant (Fs < 1).

Affective measures

State anxiety was higher in older than younger participants, F(1, 83) = 4.80, p = .03, but levels were not indicative of significant distress. No main effect of dose or Age × Dose Group interaction was detected (ps > .8).

Among older adults, a trend-level effect of the dose group was detected for GDS scores (p = .09), with those given placebo having greater depressive symptomatology than those at the .04 g/dl dose level, t(23) = 2.54, p = .02. The (a) .04 g/dl and .065 g/dl groups and (b) placebo and .065 g/dl did not differ significantly (ps > .12). No differences were detected between dose groups for BDI-II scores in younger adults (p > .43). Depressive symptomatology was within normal limits for all participants.

Alcohol consumption

A trend-level Age Group × Dose interaction was noted for QFI (average ounces of absolute ethanol consumed per day), F(2, 84) = 2.86, p = .06. Follow-up analyses indicated that among older participants, those in the placebo group had higher average daily alcohol consumption than the .04 g/dl dose group, t(25) = 2.27, p = .03. The placebo group also had a higher mean QFI than the .065 g/dl dose group, although this difference was nonsignificant, t(24) = 1.75, p = .08. No differences in QFI were detected between dose groups in younger adults.

Breath alcohol concentration measures and subjective intoxication

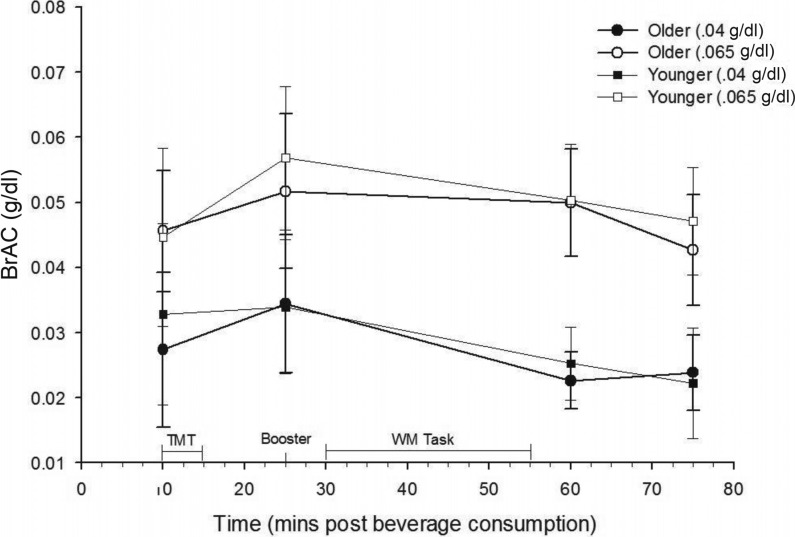

BrACs achieved in each age group and active dose condition are shown in Figure 1. As expected, a 2 (age group) × 2 (active dose level: .04 g/dl and .065 g/dl) ANOVA revealed significant differences between BrACs resulting from the two active dose levels at each time point, F(1, 53) > 21, ps < .0001. No differences in BrAC between older and younger participants were noted at any point in either active dose group (all ps > .40). In addition, although expected dose effects were detected for subjective intoxication measures (ps < .0001), no significant age effects or Age × Alcohol Dose interactions were noted (ps > .30).

Figure 1.

Breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) measures taken across the study session, by age group and dose. Significant effects of dose level, F(1, 53) > 21, p < .0001, but not age group were detected at each time point (ps > .40). As expected, a paired-samples t test indicated that mean BrACs were higher at working memory task administration than Trail Making Test (TMT) administration, t(58) = 4.90, p < .001. WM = working memory; mins = minutes.

Trail Making Test

The 2 (age group) × 3 (dose) ANOVA revealed the main effects of age group and dose, F(1, 89) = 31.64, p < .0001, and F(2, 89) = 3.13, p = .05 (Figure 2), respectively, for completion time on Part A of the TMT but no interaction (p > .78). Older adults exhibited slower completion times than younger adults, Molder = 31.09 (8.50s) versus Myounger = 22.57 (6.75s); Cohen’s d = 1.11. Follow-up t tests for the dose main effect revealed that the .04 g/dl dose level, M.04 = 24.06 (6.32s), was associated with faster completion times than placebo, Mplacebo = 28.58 (7.92s); t(60) = 2.46, p = .02; Cohen’s d = 0.63. This pattern held for the .065 g/dl dose level but did not reach significance, M.065 = 27.03 (10.53s); t(59) = 1.66, p = .10; Cohen’s d = 0.34.

Figure 2.

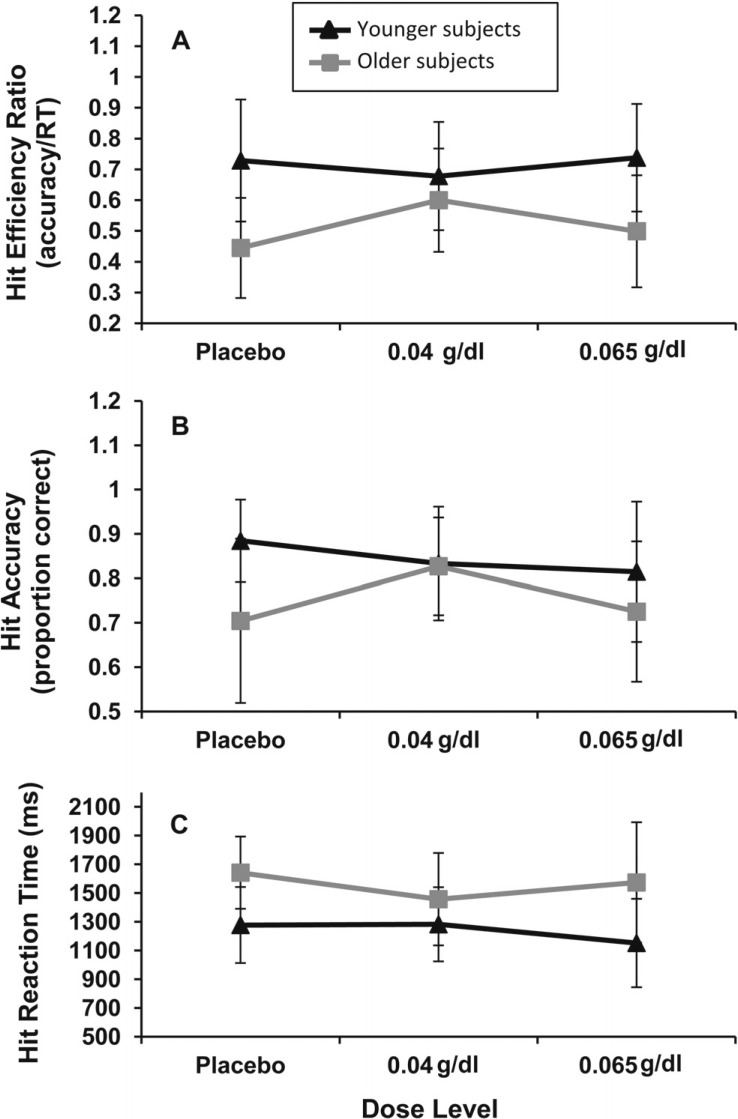

Analysis of dose effects by age group on hit performance. (A) Trend-level interaction of age group and dose on hit efficiency, F(2, 84) = 2.53, p = .09. Older subjects (Ss) were more efficient at .04 g/dl than placebo, t(23) = 2.34, p = .03. No dose effects on hit efficiency were detected for younger subjects. (B) Older subjects at .04 g/dl had higher hit rates than those at placebo, t(23) = 2.03, p = .05, or .065 g/dl, although at a trend level, t(25) = 1.95, p = .07. No dose effects on hit accuracy were noted for younger subjects (ps > .11). (C) No alcohol dose effects on hit reaction time (RT) were detected for either age group (ps > .11).

A main effect of age group, F(1, 89) = 24.70, p < .0001, and trend toward an Age Group × Dose interaction were detected, F(2, 89) = 2.51, p = .09, for Part B of the TMT. No dose main effect was detected (p > .28). As predicted, younger adults performed significantly faster than older adults regardless of alcohol dose, Myounger = 48.70 (17.16s) versus Molder = 71.57 (34.85s); Cohen’s d = 0.83. Planned comparisons revealed no difference between the three dose groups among young adults. On the contrary, older adults at the .065 g/dl dose level, M.065 = 86.46 (48.70s), performed significantly more slowly than those at the .04 g/dl dose level, M.04 = 60.47 (21.27s); t(26) = 2.52, p = .01; Cohen’s d = 0.69, but not placebo, Mplacebo = 70.13s (15.04s), p > .27. The placebo and .04 g/dl dose levels did not differ (p > .30).

Working memory task hit efficiency

The 2 (age group) × 3 (dose) × 2 (repeated: instruction set) ANOVA for hit efficiency detected significant main effects of age group, F(1, 84) = 29.83, p < .0001, and instruction set, F(1, 84) = 18.41, p < .0001, as well as a trend-level Age Group × Dose interaction, F(2, 84) = 2.53, p = .09. As expected, younger subjects were significantly more efficient than older subjects, Myounger = 0.73 (0.25) versus Molder = 0.52 (0.20); Cohen’s d = 0.92. Hit efficiency in the “remember face” instruction, Mface = 0.70 (0.26), was significantly higher than in the “remember scene” instruction, Mscene = 0.58 (0.21); Cohen’s d = 0.51. Planned comparisons following the trend-level Age Group × Dose interaction revealed no significant dose effects on hit efficiency for younger subjects (p > .32). In contrast, hit efficiency for older adults at the .04 g/dl dose level was higher than at placebo, t(23) = 2.34, p = .03; Cohen’s d = 0.91. Placebo versus .065 g/dl and .04 g/dl versus .065 g/dl comparisons were not significant (ps > .14). These effects and their characterization are illustrated in Figure 2.

Working memory task hit accuracy

Characterization of alcohol dose and age group effects on hit accuracy using similarly constructed ANOVA revealed the main effects of age group, F(1, 84) = 9.58, p = .003, and instruction set, F(1, 84) = 11.62, p = .001, and a trend-level Age Group × Dose interaction, F(2, 84) = 2.78, p = .07. Hit accuracy was, on average, higher for younger subjects than for their older counterparts, Myounger = 84.4 (12.8%) versus Molder = 75.2 (16.0%); Cohen’s d = 0.63. Likewise, hit accuracy was higher in the remember face than remember scene instruction set, Mface = 84.8 (17.9%) versus Mscene = 76.3 (19.0%); Cohen’s d = 0.46. Characterization of the Age Group × Dose interaction revealed that increasing dose was associated with nonsignificant reductions in hit accuracy relative to placebo for younger subjects (ps > .10). However, older adults showed a dose effect on hit accuracy that mirrored dose effects on hit efficiency. Hit accuracy was higher for older adults at the .04 g/dl dose level than either the placebo, t(23) = 2.03, p = .05; Cohen’s d = 0.81, or .065 g/dl dose level, although at a trend level, t(25) = 1.95, p = .07; Cohen’s d = 0.75. The placebo and .065 g/dl dose levels did not differ from one another (p > .75).

Working memory task hit reaction time

Analysis of age group, dose group, and instruction set effects on hit RT revealed predicted age-related slowing, F(1, 84) = 23.84, p < .0001; Myounger = 1,236.60 ms (279.2) versus Molder = 1,555.1 ms (341.9); Cohen’s d = 1.02. In addition, hit RTs were faster in the remember face than remember scene instruction set, F(1, 84) = 5.34, p = .02; Mface = 1,331.69 ms (395.48) versus Mscene = 1,417.36 ms (372.11), p = .02; Cohen’s d = 0.22. No other significant main or interactive effects were noted (ps > 0.28).

Working memory task correct rejection efficiency

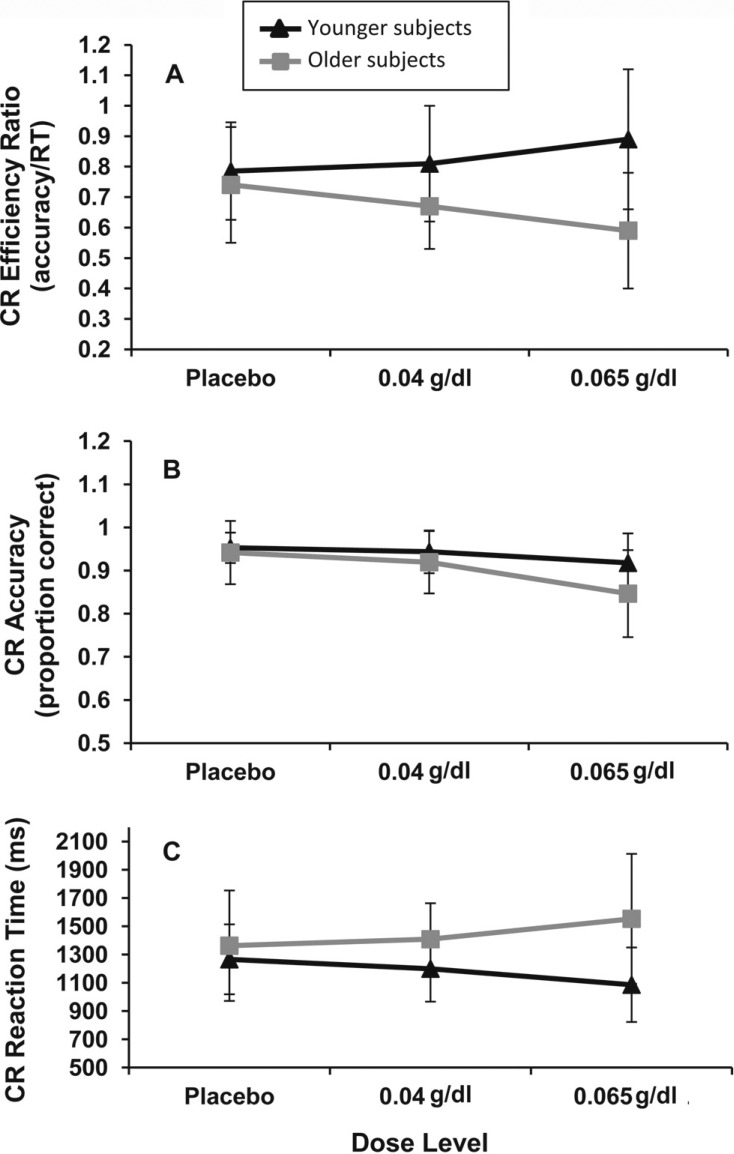

The 2 (age group) × 3 (dose) × 2 (repeated: instruction set) ANOVA for working memory task correct rejection efficiency revealed an expected main effect of age, F(1, 84) = 16.30, p = .0001, with older adults having lower efficiency than younger adults, Molder = 0.66 (0.18) versus Myounger = 0.83 (0.19); Cohen’s d = 0.92, and an Age Group × Dose interaction, F(2, 84) = 4.04, p = .02. Characterization of the Age Group × Dose interaction showed that younger adults at the .065 g/dl dose level were more efficient than those at placebo, albeit at a trend level, t(34) = 1.81, p = .07; Cohen’s d = 0.56; the .04 g/dl dose level was not significantly different from either dose (ps > .26). In contrast, older adults at the .065 g/dl dose level were significantly less efficient than those at placebo, t(24) = 2.06, p = .04; Cohen’s d = 0.79. Again, the .04 g/dl dose level was not significantly different from either of the others (ps > .24). These interactive effects and their subsequent characterization are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Analysis of age group by dose effects on correct rejection performance. (A) A significant interaction of age group and dose on correct rejection efficiency, F(2, 84) = 4.04, p = .02. Older subjects (Ss) at .065 g/dl had significantly lower efficiency than placebo, t(24) = 2.06, p = .04; an opposite trend-level effect was noted for younger subjects, t(34) = 1.81, p = .07. (B) Significant effect of dose on correct rejection accuracy across age groups, F(2, 84) = 7.57, p = .001. Subjects at the .065 g/dl dose level had lower accuracy than those at .04 g/dl, t(53) = 2.96, p = .02, or placebo, t(48) = 3.35, p = .001. (C) Trend-level Age Group × Dose interaction on correct rejection (CR) reaction time (RT), F(2, 84) = 2.78, p = .07. The .065 g/dl dose level was associated with decreased RT compared with placebo for younger subjects, t(34) = 1.72, p = .09). Older subjects showed a nonsignificant increase in RT (p > .12).

Finally, an Age Group × Dose × Instruction Set interaction, F(2, 84) = 3.04, p = .05, was also noted. Age Group × Dose interactions were in turn detected for both the remember face and the remember scene instruction sets, F(2, 84) = 3.71, p = .03, and F(2, 84) = 3.95, p = .02, respectively. Simple main effects analysis for the remember face instruction revealed that older adults at the .065 g/dl dose level had poorer efficiency than those at placebo, t(24) = 2.04, p = .04; Cohen’s d = 0.90, or the .04 g/dl dose level, t(25) = 1.87, p = .06; Cohen’s d = 0.87, although the latter comparison was trend level. The .04 g/dl and placebo dose levels did not differ (p > .84). Dose had no effect on the efficiency of younger subjects in this instruction set (ps > .19).

For the remember scene instruction, simple main effects analysis showed that younger adults at the .065 g/dl dose level had better efficiency than those at placebo, t(34) = 2.20, p = .03; Cohen’s d = 0.79. However, no differences between the .04 g/dl and either other dose level were detected (ps > .13). No significant dose effects were found on correct rejection efficiency for older adults (ps > .10).

Working memory task correct rejection accuracy

Main effects of age group and dose were identified for correct rejection accuracy, F(1, 84) = 6.01, p = .02, and F(2, 84) = 7.57, p = .001, respectively. Older subjects had a lower correct rejection accuracy, Molder = 90.0 (9.2%), than younger subjects, Myounger = 93.8 (5.4%); Cohen’s d = 0.50, and the .065 g/dl dose level, M.065 = 88.6 (9.1%), was associated with a lower accuracy for correct rejections than either the .04 g/dl dose, M.04 = 93.2 (6.1%); t(53) = 2.96, p = .02; Cohen’s d = 0.59, or placebo, Mplacebo = 94.8 (5.2%); t(48) = 3.35, p = .001; Cohen’s d = 0.84, across all subjects. No other main effects or interactions were noted (ps > .13).

Working memory task correct rejection reaction time

Both a main effect of age group and a trend-level Age Group × Dose interaction were noted for correct rejection RTs, F(1, 84) = 14.89, p = .0002, and F(2, 84) = 2.78, p = .07, respectively, with older subjects having a slower mean RT than younger subjects, Molder = 1,441.00 (432.10 ms) versus Myounger = 1,183.92 (267.4 ms); Cohen’s d = 0.72. No other main effects or interactions were noted (ps > .11).

Interestingly, comparisons following the trend-level Age Group × Dose interaction revealed opposite patterns of increasing alcohol dose on RT for younger and older subjects. Trend-level speeding of correct rejection RT for younger subjects at the .065 g/dl dose level versus placebo was detected, t(34) = 1.72, p = .09; Cohen’s d = 0.70. The .04 g/dl dose level was not significantly different from either alternate dose (ps > .30). In contrast, nonsignificant slowing was seen for older adults at the .065 g/dl dose level (p > .12). The .04 g/dl was again not significantly different from the other doses (ps > .23).

Discussion

Analyses indicated age-related deficits in psychomotor, set shifting, and working memory performance consistent with the existing literature (Gazzaley et al., 2008; Verhaeghen et al., 2003). The effects of acute alcohol administration were more variable. As predicted, simple psychomotor performance (i.e., TMT Part A) was not impaired by the moderate alcohol doses used in this study. However, a modest benefit in simple psychomotor performance relative to placebo was noted at the lower dose for both age groups. We are unaware of previous reports describing such an effect in older adults. In contrast, there were medium to large impairments in TMT Part B performance in older adults at the higher dose level, a task previously shown to be sensitive to alcohol and age interactions (Gilbertson et al., 2009).

Effects of age group and alcohol dose level on working memory efficiency differed between trials with previously presented and previously unseen probes. For previously presented probes (hits), older adults at the lower dose had better efficiency than those at the other dose levels, making their performance equivalent to that of younger adults. This increase in efficiency was driven by an increase in accuracy. Although further work is needed, we speculate that this effect may be attributable to alcohol myopia; that is, the .04 g/dl dose may have increased the focus of older adults on cue and/or probe stimuli, resulting in improved accuracy (Steele and Josephs, 1990). If this is the case, then detected facilitatory effects of moderate alcohol administration on working memory performance in older adults may be attenuated in tasks where attention is divided. Alcohol administration had no effect on RT, suggesting that performance differences were not due to a speed/accuracy tradeoff.

An alternate explanation for the apparent facilitatory effect of the .04 g/dl dose level on efficiency of responding to previously presented probes in older adults is related to the lower depressive symptomatology noted in the .04 g/dl group compared with the placebo or .065 g/dl dose levels. However, as noted in the Analysis strategy section, GDS score did not correlate significantly with any dependent variable, including RT. Thus, differences in depressive symptomatology between dose groups in older adults do not appear to account for these results. However, future studies should consider potential confounding effects of subclinical depressive symptomatology on processing speed.

Age and alcohol effects on the efficiency of responses to previously unseen probes (correct rejections) followed a divergent pattern. Younger adults performed more efficiently at the highest dose level, similar to previous results (Sklar et al., 2012). In contrast, older adults performed least efficiently at the highest dose level. Despite negative effects of the .065 g/dl dose on accuracy of rejection across age groups, we found that this dose was associated with decreased RT for younger adults and increased RT for older adults. Decreased efficiency in older adults appeared as a result of a combination of poorer accuracy and a nonsignificant increase in RT.

The processes underlying the differential effects of alcohol dose and age on hits and correct rejections are unclear. It is possible that these mechanisms relate to the effects of alcohol dose and age group on one or more aspects of working memory, including (a) the employed memory scanning strategies and/or (b) the costs (in terms of mental effort) associated with these strategies (Crowder, 1976; Donkin and Nosofsky, 2012; Sternberg, 1975). However, we did not test these possibilities in the current study (see limitations below).

Study limitations

Observed differences in the effects of moderate alcohol administration on neuropsychological function in older adults may not be strictly attributable to age, per se. For example, although we minimized variability in blood glucose levels by requiring study participants to fast for at least 4 hours before the start of the laboratory session, it is possible that those participants whose sessions began relatively later (e.g., 10:30 a.m.) may have eaten breakfast outside the 4-hour window. Unfortunately, participants were not asked whether they had eaten before beginning their 4-hour fast. Therefore, although participants were aware that they would receive breakfast on arrival, potential variation in blood glucose levels because of this behavior cannot be assessed. Furthermore, although thorough screening was conducted to avoid inclusion of participants with potentially confounding medical histories, the effects of certain risk factors for neuropsychological decline—such as estrogen levels and sleep quality/quantity (Ratcliff and Van Dongen, 2009; Sherwin, 2012)—on study measures cannot be assessed because these data were not collected. Educational attainment and occupational demands may also influence age-related changes in neuropsychological function. As previously noted, educational attainment did not correlate with efficiency, accuracy, or RT measures in this study. Data related to occupational demand were not available for this analysis; however, future studies should include it as a consideration.

It is poorly understood whether physiological differences between sexes may modulate the effects of acute moderate alcohol on psychomotor, set shifting, and working memory performance. Thus, the potential interaction of sex with alcohol administration and age is of interest. However, insufficient numbers of older men at the placebo and .04 g/dl dose levels (n = 5 and n = 4, respectively) prevented meaningful analysis of sex effects and interactions. We are currently conducting studies designed to address this limitation.

In addition, the remember/ignore task used in this study was relatively straightforward, requiring maintenance of only two faces or scenes in working memory. Extending these results using a more difficult task, including additional cue stimuli, would help (a) determine whether detected Age Group × Alcohol Dose interactions differ as a function of memory load and (b) prevent ceiling effects on performance.

The between-subjects design of this study may be considered a limitation because within-subject designs minimize intersubject variability, maximizing power to detect treatment effects. Therefore, potentially important effects and interactions might have been detected with a within-subjects design. Although future studies would benefit from repeated assessments, the between-subjects design of this study avoids issues related to practice effects or incomplete data that result from loss at follow-up.

Finally, although of significant conceptual interest, a comprehensive signal detection analysis of remember/ignore task performance was not possible because participants did not indicate their level of confidence when indicating whether stimuli were previously presented. Future studies would benefit from inclusion of this measure.

Conclusions

Taken together, the results of this study suggest differential effects of moderate alcohol administration on working memory efficiency in older and younger adults. Whether effects were negative or apparently beneficial depended on age group, dose, and probe stimulus novelty. Of particular interest were findings of improved efficiency and accuracy for previously present stimuli under the .04 g/dl dose level in older adults. Analysis of electrophysiological data recorded during task performance, currently underway, may help elucidate potential attentional mechanisms underlying this study’s findings. In addition, further investigation using additional task modalities, including complex behavioral paradigms (e.g., simulated driving), is necessary. Such studies are ongoing in our laboratory.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the subjects of the study for their generosity and willingness to participate. Special thanks to Adam Gazzaley, M.D., Ph.D., who graciously provided working memory task stimuli and timing parameters. Ben Lewis, Ph.D., Layla Lincoln, Lauren Hoffman, and Cole McCarty assisted in recruiting, screening, and conducting laboratory sessions. In addition, Dr. Lewis provided helpful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

This study was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants R01AA019802 (to Sara Jo Nixon, principal investigator) and F31AA0919862 (to Jeff Boissoneault, principal investigator, and Sara Jo Nixon, sponsor). Jeff Boissoneault is currently supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Training Grant T32NS045551 to the University of Florida Pain Research and Intervention Center of Excellence.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anguera JA, Gazzaley A. Dissociation of motor and sensory inhibition processes in normal aging. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2012;123:730–740. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Breitmeier D, Seeland-Schulze I, Hecker H, Schneider U. The influence of blood alcohol concentrations of around 0.03% on neuropsychological functions—A double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation. Addiction Biology. 2007;12:183–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan D, Cissin L, Crossley H. American drinking practices: A national study of drinking behaviors and attitudes (Monograph No. 6) New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Carriere JS, Cheyne JA, Solman GJ, Smilek D. Age trends for failures of sustained attention. Psychology and Aging. 25:569–574. doi: 10.1037/a0019363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charness N. Can acquired knowledge compensate for age-related declines in cognitive efficiency? In: Qualls SH, Abeles N, editors. Psychology and the aging revolution: How we adapt to longer life (pp. 99–117) Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Crowder RG. Principles of learning and memory. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Davies BT, Bowen CK. Total body water and peak alcohol concentration: A comparative study of young, middle-age, and older females. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23:969–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H. Laboratory-based assessment of alcohol craving in social drinkers. Addiction. 2000;95(Supplement 2):S165–S169. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djoussé L, Lee IM, Buring JE, Gaziano JM. Alcohol consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease and death in women: Potential mediating mechanisms. Circulation. 2009;120:237–244. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.832360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donkin C, Nosofsky RM. The structure of short-term memory scanning: An investigation using response time distribution models. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2012;19:363–394. doi: 10.3758/s13423-012-0236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DM, Marsh-Richard DM, Hatzis ES, Nouvion SO, Mathias CW. A test of alcohol dose effects on multiple behavioral measures of impulsivity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT. Acute alcohol-induced impairment of cognitive functions: Past and present findings. International Journal on Disability and Human Development. 2007;6:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Dixon MJ, Schweizer TA. Alcohol affects processing of ignored stimuli in a negative priming paradigm. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:571–578. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman TW, Robinson SR, Yelland GW. Impaired perceptual judgment at low blood alcohol concentrations. Alcohol. 2011;45:711–718. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaley A, Clapp W, Kelley J, McEvoy K, Knight RT, D’Esposito M. Age-related top-down suppression deficit in the early stages of cortical visual memory processing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:13122–13126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806074105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaley A, Cooney JW, Rissman J, D’Esposito M. Top-down suppression deficit underlies working memory impairment in normal aging. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:1298–1300. doi: 10.1038/nn1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson R, Ceballos NA, Prather R, Nixon SJ. Effects of acute alcohol consumption in older and younger adults: Perceived impairment versus psychomotor performance. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:242–252. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway FA. Low-dose alcohol effects on human behavior and performance: A review of post-1984 research (Pub. No. 94–35919) Washington, DC: Federal Aviation Administration; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Nagata C, Tsuji I, Sugawara Y, Wakai K, Tamakoshi A, Tsugane S the Research Group for the Development and Evaluation of Cancer Prevention Strategies in Japan. Impact of alcohol intake on total mortality and mortality from major causes in Japan: A pooled analysis of six large-scale cohort studies. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2012;66:448–456. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.121830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E. A process approach to neuropsychological assessment. In: Boll T, Bryant BK, editors. Clinical neuropsychology and brain function: Research, measurement, and practice (pp. 125–167) Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis B, Boissoneault J, Gilbertson R, Prather R, Nixon SJ. Neurophysiological correlates of moderate alcohol consumption in older and younger social drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:941–951. doi: 10.1111/acer.12055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon SJ. Neurocognitive performance in alcoholics: Is polysubstance abuse important? Psychological Science. 1999;10:181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Oscar-Berman M, Marinković K. Alcohol: Effects on neurobehavioral functions and the brain. Neuropsychology Review. 2007;17:239–257. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9038-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI. Orienting of attention. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1980;32:3–25. doi: 10.1080/00335558008248231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Van Dongen HPA. Sleep deprivation affects multiple distinct cognitive processes. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009;16:742–751. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.4.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed SC, Levin FR, Evans SM. Alcohol increases impulsivity and abuse liability in heavy drinking women. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2012;20:454–465. doi: 10.1037/a0029087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological test battery: Theory and clinical interpretation. 2nd ed. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychology Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholz KK, Compton W. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version IV. St. Louis, MO: Washington University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin BB. Estrogen and cognitive functioning in women: Lessons we have learned. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2012;126:123–127. doi: 10.1037/a0025539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar AL, Gilbertson R, Boissoneault J, Prather R, Nixon SJ. Differential effects of moderate alcohol consumption on performance among older and younger adults. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36:2150–2156. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Manual for state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg S. Memory scanning: New findings and current controversies. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1975;27:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-41, DHHS Publication No. SMA 11–4658) Rockville, MD: Author; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Illinois. HarperCollins; 1989. Using multivariate statistics: Second edition. Glenview. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture & United States Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. Retrieved from www.dietaryguidelines.gov. [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P, Steitz DW, Sliwinski MJ, Cerella J. Aging and dual-task performance: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:443–460. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson PE, Watson ID, Batt RD. Prediction of blood alcohol concentrations in human subjects: Updating the Widmark equation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1981;42:547–556. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1981.42.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1982–1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]