Abstract

Transport of macromolecules between the cytoplasm and the nucleus is critical for the function of all eukaryotic cells. Large macromolecular channels termed nuclear pore complexes that span the nuclear envelope mediate the bidirectional transport of cargoes between the nucleus and cytoplasm. However, the influence of macromolecular trafficking extends past the nuclear pore complex to transcription and RNA processing within the nucleus and signaling pathways that reach into the cytoplasm and beyond. At the Mechanisms of Nuclear Transport biennial meeting held from October 18-23, 2013 in Woods Hole, MA, researchers in the field met to report on their recent findings. The work presented highlighted significant advances in understanding nucleocytoplasmic trafficking including how transport receptors and cargoes pass through the nuclear pore complex, the many signaling pathways that impinge on transport pathways, interplay between the nuclear envelope, nuclear pore complexes, and transport pathways, and numerous links between transport pathways and human disease. The goal of this review is to highlight newly emerging themes in nuclear transport and underscore the major questions that are likely to be the focus of future research in the field.

Introduction

The primary cell biological feature of all eukaryotic cells is the presence of a nucleus, a double membrane-bound organelle that encapsulates the genetic material and physically separates the process of transcription from the translational machinery in the cytoplasm. This spatial compartmentalization necessitates selective and efficient transport through the nuclear pore complex or NPC, a huge macromolecular assembly of proteins that provides a selective portal for movement across the nuclear envelope (NE). Although the major factors required to recognize and transport macromolecules into and out of the nucleus through NPCs have been known for well over a decade, substantial gaps in our understanding of the mechanisms underlying this selective transit still exist.

A recent biennial meeting of researchers in this field held this past year in Woods Hole, MA provided an opportunity to report on new advances in the field of nucleocytoplasmic transport. This meeting highlighted the cutting-edge, multidisciplinary approaches being taken to understand not only transport across the NPC but also the assembly of this complex structure and the coupling of nuclear transport with other cellular processes. Exciting discussions resulted from the combined intellectual strengths of geneticists, cell biologists, structural biologists and biophysicists. While some consensus on transport of cargoes through nuclear pore complexes is emerging, additional functions and pathways are surfacing for NPC-associated proteins and for the NPC itself. This complexity indicates that the transport process is ripe for regulation at various levels, presenting additional opportunities and challenges to scientists as the basis for selective movement across the NPC continues to be revealed.

The Nuclear Pore Complex

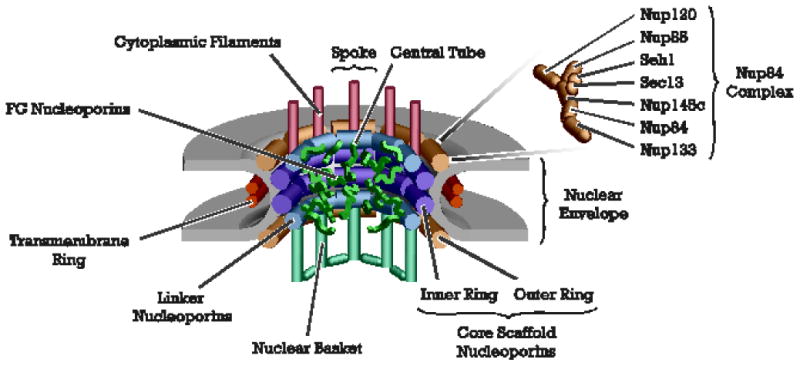

The nuclear envelope (NE) of a eukaryotic cell is composed of an outer and inner nuclear membrane (ONM and INM, respectively) separated by a luminal space. Distributed throughout the NE, the NPCs are embedded at sites of fusion between the ONM and INM [1, 2]. The NPCs themselves are composed of relatively few protein components (∼30) that are repeated in an 8-fold rotationally symmetric structure, with an additional two-fold axis of symmetry in the plane of the NE for many components (Figure 1) [2, 3]. Studies of the mechanism by which cargoes transit the NPC rely on building a comprehensive list of the puzzle pieces that comprise the NPC and an image of how these pieces assemble to form this remarkable macromolecular machine.

Figure 1. The architecture of the eight-fold, rotationally symmetric nuclear pore complex (provided by Michael Rout).

A schematic diagram of the primary features of the nuclear complex illustrates the sophisticated nature of this macromolecular assembly. The NPC is embedded within a NE pore, formed by fusion of the outer and inner nuclear membranes. A transmembrane ring is present on the outside of the pore, aiding stabilization. Within the core of the NPC are scaffolding proteins that form the inner and outer ring within the channel. At the cytoplasmic and nuclear face are the cytoplasmic filaments and nuclear basket structures, respectively, which serve as docking sites for nuclear transport events. The FG domains of the FG nucleoporins are shown protruding into the aqueous channel of the NPC. These domains serve as docking sites for transport receptors, allowing passage through the pore. The Nup84 complex is a substructure located at the outer periphery of the cytoplasmic face of the NPC, which is required for proper distribution of individual NPCs around the NE [7].

Architectural Assembly of the NPC

The NPC is composed of a central core that mediates transit across the NE as well as peripheral components comprised of cytoplasmic filaments and a nuclear basket that mediate transport receptor-cargo docking (Figure 1). The proteins that make up the NPC, collectively termed nucleoporins or Nups, anchor the NPC to the NE and provide interaction domains for transport events. While many researchers have helped to define individual components of the NPC, Michael Rout (Rockefeller University, USA) and his collaborators have provided some of the most comprehensive studies [4-6]. This group first reported the overall composition of the NPC in 2000 [5]. They now continue to refine our understanding of how specific Nups are organized within the larger structure of the NPC (Figure 1). At the meeting, Rout reported on his group's detailed analysis of budding yeast cells harboring mutations in specific sub-complexes within the NPC. Using a combination of electron microscopy, protein domain mapping data, and yeast genetics, they demonstrated that mutations in genes encoding components of the Y-shaped complex, which is composed of Nup84, Nup85, Nup120, Nup133, Nup145C, Sec13 and Seh1 in budding yeast [7, 8], have differential effects on mRNA export and NPC distribution. Such functional studies will continue to define the contributions of distinct sub-complexes within the NPC, thereby enhancing our understanding of NPC assembly and function.

Another approach to describe the overall architecture of the NPC is to define the high-resolution three-dimensional structures of individual domains of Nups and then map the resulting structures back to lower resolution models primarily from electron microscopy. Such structural information allows inference of both function and potential dynamics of the larger complex [9]. Sozanne Solmaz from the Blobel laboratory (Rockefeller University, USA) and Andre Hoelz (California Institute of Technology, USA) both reported structural studies of Nups that could provide insight into the overall organization and function of the NPC. Solmaz described analysis of the mammalian FG Nups, Nup62, Nup54, and Nup58, using X-ray crystallography. Her studies revealed the alpha-helical nature of these proteins, which could suggest that these Nups have the capacity to flex and slide, thus facilitating large diameter changes within the central transport channel of the NPC [10]. Hoelz described the structure of several Nups from the thermophilic fungi, C. thermophilum. His structural studies of the N-terminal domain of Nup192 reveal two rigid halves of the molecule connected by a flexible hinge region [11]. Interestingly, Hoelz and others have shown that the two domains are comprised of HEAT and ARM repeat motifs [11-13], which share structural similarity with transport receptors of the importin/karyopherin family [14-17]. Complementary biochemical approaches allowed the Hoelz group to define modes of interaction with both Nup53 and Nic96, two other components of the NPC [11]. Thus, structural studies are beginning to yield insight into how individual components of the NPC can be assembled to create this enormous macromolecular channel.

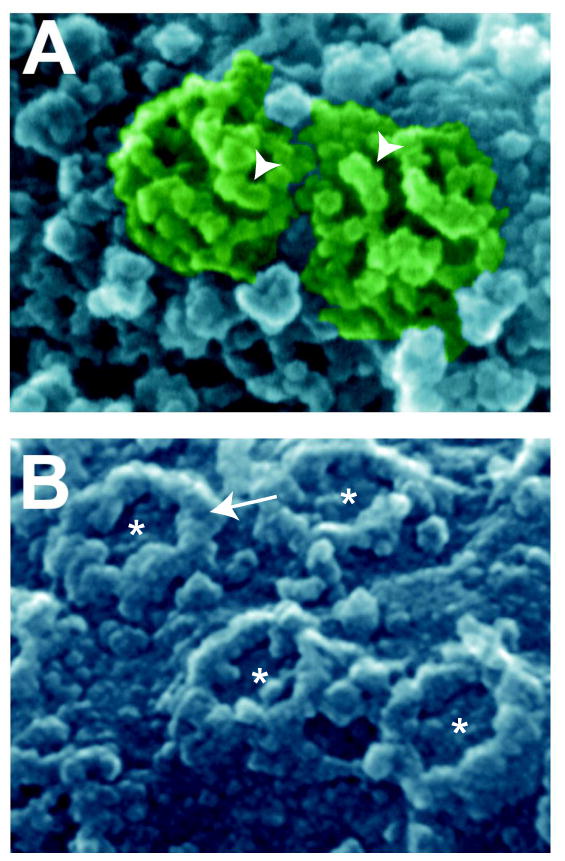

Productively piecing together the high-resolution crystal structures of individual Nup domains requires increasingly refined images of the Nup subcomplexes and intact NPCs, particularly by electron microscopy [18]. Martin Beck (EMBL, Germany) presented an impressive example showcasing the value of integrating new methodologies to reconstruct the architecture of the human NPC. Working in collaboration with the lab of Joseph Glavy (Stevens Institute of Technology, USA), the Beck group determined the overall structure of the human Y-shaped complex (also known as the Nup107 subcomplex and analogous to the S. cerevisiae Nup84 complex) by single-particle electron tomography [19] . The team also vastly improved the model of the human NPC scaffold to 3.2 nm resolution by combining cryo-electron tomography and sophisticated image analysis that leverages the 8-fold symmetry of the NPC [20], allowing them to place the Y-shaped complex within the NPC scaffold using a template-matching approach [19]. This model was further validated by crosslinking mass spectrometry [19]. Combining these powerful techniques, this study revealed that the stoichiometry of the Y-shaped complex within the NPC may differ in human cells compared to the Nup84 complex of budding yeast, providing a satisfying explanation to the mysterious difference in NPC mass across eukaryotic systems despite the similarity in individual Nup components [19] [6]. Collectively, these studies reveal a remarkably similar overall organization of the NPC across the kingdoms of life [21] as illustrated in images presented by Martin Goldberg (Durham University, UK) comparing field emission microscopic images of plant and fungal NPCs (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Field emission microscopic images of plant and fungal NPCs (provided by Martin Goldberg).

A. SEM image of the surface of an isolated S. cerevisiae nucleus showing two nuclear pore complexes (green). Arrowheads indicate prominent cytoplasmic filaments. B. SEM image of the surface of a tobacco BY-2 cell nucleus. The channel of the NPCs is indicated by asterisks and the cytoplasmic ring is indicated for one NPC with an arrow. These images illustrate the conservation of the symmetric nature of NPCs and the presence of a cytoplasmic ring and/or filaments across eukaryotes.

As all these multi-faceted approaches continue to improve and converge, the high-resolution structure of the NPC is beginning to come into focus [18, 22]. Researchers in the field continue to push the boundaries of technology to define the complex macromolecular structure that allows the NPC to serve as both an effective barrier and an efficient transit channel that can allow rapid and specific transport of numerous macromolecular cargoes.

Transport Through the Pore

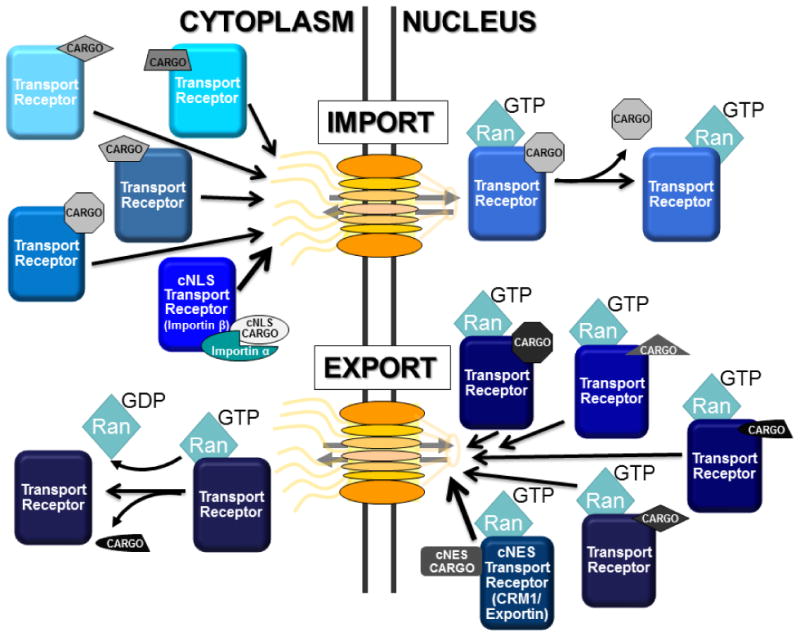

Movement through the NPC involves a series of steps including docking at the periphery of the NPC, translocation through the channel, and, finally, release from the NPC into the destination compartment [3]. With the exception of small molecules, metabolites and proteins < ∼40 kDa, transport through the NPC is both receptor and energy-dependent. Nuclear transport receptors often termed karyopherins or importins/exportins support bidirectional transport for the vast majority of nucleocytoplasmic transport events by virtue of their ability to interact with three distinct protein partners: transport cargo, FG Nups and the small GTPase, Ran [23]. As shown in Figure 3, Ran provides directionality to the transport process by regulating the interaction between transport receptors and the selected cargo.

Figure 3. Many Pathways Exist for Transport into and out of the Nucleus.

The vast majority of nuclear transport depends on the small GTPase Ran and nuclear transport receptors most often termed karyopherins but also importins/exportins. During cargo import (top), transport receptors (shown in shades of blue) associate with cargo (shown in gray) in the cytoplasm through either direct recognition of nuclear localization signals (NLS) or in the case of the classical NLS (cNLS) through the aid of the adaptor protein, importin/karyopherin α (Kap60 in budding yeast). These complexes transit the pore into the nucleus whereby cargo release is triggers by the binding of RanGTP to the receptor-cargo complex. Cargo export (bottom) occurs through formation of an obligate trimeric complex consisting of RanGTP, export cargo (shown in gray/black), and transport receptor (shown in shades of blue). This trimeric complex moves through the pore and is then disassembled in the cytoplasm when Ran hydrolyzes GTP to GDP. The GTPase activity of Ran is specifically localized to the cytoplasm by the presence of GTPase activating proteins. RanGDP is re-imported into the nucleus and then “re-loaded” with GTP through the activity of the Ran guanine nucleotide exchange factor or RanGEF, which is associated with chromatin. The compartmentalization of RanGTP/GDP confers directionality on the system. Thus, there are numerous transport pathways to move macromolecular cargoes into and out of the nucleus. The vast majority of the targeting signals required for these transport pathways have not yet been defined.

Cargo proteins contain specific transport signals that are recognized by transport receptors [23, 24]. The most well understood and thus described transport motifs are the classical Nuclear Localization Signal (cNLS) consisting of a series of basic residues [25] and the classical Nuclear Export Signal (cNES) consisting of spaced leucine and other hydrophobic residues [26]. Cargoes containing a cNLS motif are recognized by an importin/karyopherin α adapter protein to form a complex with the import karyopherin receptor, importin/karyopherin β. This trimeric import cargo complex assembles in the cytoplasm in the absence of RanGTP and is disassembled when RanGTP binds to importin/karyopherin β in the nucleus [27]. However, the cNLS import pathway is a specialized import pathway in that it utilizes an adaptor, importin α. Indeed, most transport cargoes are likely recognized directly through binding of a specific transport receptor from the importin/karyopherin β family (Figure 3). Export complexes, such as the cNES-dependent pathway that use the importin/karyopherin β export receptor termed CRM1 [28-30], form obligate trimeric complexes comprised of the transport receptor, the cargo, and RanGTP. This export complex is disassembled in the cytoplasm when Ran hydrolyzes GTP to GDP. Congruent with this mechanism, levels of RanGTP are elevated in the nucleus, where export complexes assemble and import complexes disassemble, due to the nuclear localization of the RanGTP exchange factor (GEF) that promotes generation of RanGTP from RanGDP and the cytoplasmic localization of the Ran GTPase Activating Protein (GAP) that stimulates the GTP hydrolysis activity of Ran [31]. Thus, the GTP-bound state of Ran defines the compartmental requirements for cargo loading and delivery.

The classical import and export pathways represent one route for cargoes to transit the NPC (Figure 3). However, there are more than 20 transport receptors in mammals and 14 in budding yeast [32]. Thus, the absence of a “classical” transport signal in no way precludes transport receptor-mediated transit of a cargo into or out of the nucleus. Some of the signals recognized by the other members of the transport receptor family have begun to be defined through structural studies of receptor/cargo complexes [23, 24]. One transport signal that has emerged from such an approach is termed a Proline Tyrosine (PY)-NLS, which is found in a number of RNA binding proteins [33]. Interestingly, the PY-NLS is defined not so much by the primary amino acid sequence but more by general structural features, making this motif challenging to identify by simple sequence analysis [34]. An ongoing goal for the field is to continue to define multiple cargo proteins that interact with specific transport receptors as well as to provide atomic level insight into mechanisms of recognition. Such approaches may lead to the development of tools to identify transport pathways/receptors for specific cargoes, which can only currently be inferred for the classical nuclear import and export pathways.

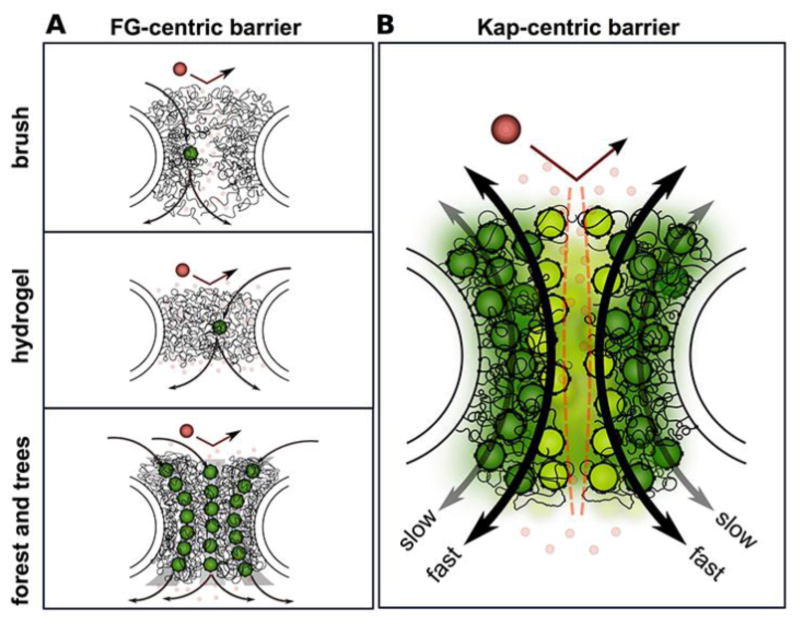

The NPC Permeability Barrier

A major open question in the nuclear transport field is the biochemical basis of the selective transport barrier within the NPC. The NPC supports two fundamental activities: 1) it restricts molecules greater than ∼5 nm in diameter from passing freely through the channel while; 2) simultaneously supporting the signal-dependent transit of larger cargo molecules through their interaction with transport receptors [3, 35]. At the heart of these activities lie the phenylalanine glycine (FG) repeat-containing Nups or FG Nups (reviewed in [36]) that line the interior of the NPC (Figure 4). These natively unfolded FG domains [37, 38] both define the effective sieve size of the NPC through intra- and intermolecular interactions and serve as interaction sites for soluble transport receptor-cargo complexes to facilitate their translocation across the NPC [39-41]. Several models for the physical nature of the FG network have been developed in the field, providing rich fodder for discussion [40, 42-44] (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Transport selectivity is maintained by the FG barrier within the NPC (adapted from material provided by Roderick Lim and Larisa E. Kapinos).

The question of how the NPC serves as both an efficient barrier and rapid transit machine remains a point of debate. Several models were discussed at the meeting. Prevailing transport models advocate that the barrier mechanism is composed of FG domains. In all cases, selective transport is exclusive to karyopherins (transport receptors; dark green) that bind the FG repeats via multivalent interactions. Small molecules (small red watermarked) diffuse freely through the barrier whereas large non-specific molecules (large red) are withheld due to insufficient interaction with the FG repeats. The models differ with respect to the nature of the FG barrier and its interactions with transport receptors. A. The hydrogel model is based on cohesive interactions between FG repeat domains that create a sieve-like barrier that is selectively permeable to transport receptors [39]. B. The brush model is based on the increased extensibility of the FG Nups due to steric repulsion that wins against competing cohesive interactions [143]. C. The forest model combines aspects of the hydrogel and brush models and is based on the concept that individual FG Nups have distinct properties, being either trees (favoring an extended conformation) or shrubs (favoring a compact conformation). Cohesive interactions also play a role in this model, which suggests that distinct “zones” through the NPC may be taken by individual cargo-transport receptor complexes [144]. D. A Kap-centric NPC barrier mechanism model is based on the ability for the FG domains to bind and accommodate large numbers of Kaps (transport receptors) at physiological concentrations [48, 49]. Owing to strong binding avidity, the Kaps that reside within the FG domains (dark green) are slow and form integral barrier constituents. Nevertheless, this is a prerequisite for weakly-bound Kaps (light green) that dominate fast transport due to limited penetration into the pre-occupied FG domains (e.g., aka the “dirty velcro” effect).

The selective phase model [45, 46], presented by Dirk Görlich (MPI for Biophysical Chemistry, Göttingen, Germany), relies on two principles. First, barrier-forming FG repeat domains (notably those from metazoan Nup98 and its yeast paralogues Nup100 and 116) engage in multivalent cohesive interactions, forming a sieve-like FG hydrogel whose mesh size sets an upper size limit for passive NPC-passage (Figure 4A). Second, FG repeat-repeat interactions disengage locally and transiently when a transport receptor binds the corresponding FG motifs, allowing the transport receptor to “melt” the gel and consequently pass through the hydrogel. Harnessing the powerful Xenopus and budding yeast model organisms, Görlich provided evidence that cohesive FG domains can form an FG hydrogel with NPC-like selectivity, excluding inert macromolecules ≥5nm, but allowing a >1000 times faster influx of the same macromolecule bound to a transport receptor [42, 47]. He also showed that replacing the cohesive Nup98/Nup100/Nup116 FG domains with non-cohesive FG domains is lethal in S. cerevisiae and disrupts the selectivity barrier of Xenopus NPCs.

Another model, termed the Kap-centric model [48, 49], was presented at the meeting by Roderick Lim (University of Basel, Switzerland), who proposed that Kaps (transport receptors) serve as integral, possibly regulatory constituents of the NPC barrier mechanism. This model is founded on the idea that each FG Nup can bind multiple Kaps, predicting that cargo-bearing Kaps might interact more transiently with FG Nups that are already saturated with Kaps as they the escort cargo through the central channel (Figure 4D) [48, 49]. Such a model could help explain the rapid transit time of transport receptor-cargo complexes through the NPC. Lim further demonstrated how this so-called “dirty velcro” effect could be applied in a biomimetic manner to regulate the two-dimensional diffusion of Kap-functionalized 1 μm-diameter colloidal beads on glass slides decorated with FG Nup molecular brushes [50]. Extending the question to consider how very large cargo molecules pass through the NPC is important as fully assembled ribosome subunits can exit the nucleus following assembly. Siegfried Musser (Texas A&M University) addressed this question by combining single molecule fluorescence microscopy and mathematical modeling. His work provides evidence that large cargoes require the binding of multiple transport receptors to transit the NPC [40], a process in which multivalent interactions between FG repeats and transport receptors are essential. While progress is being made in understanding how the FG Nups can function simultaneously as an efficient barrier and a medium for rapid transit, further work is required to ultimately define the precise biophysical properties that allow such diametrically opposed functions.

Whereas the FG repeats provide the permeability barrier within the NPC, the directionality of transport has been thought to reside solely in the docking and release steps of the receptor-cargo complexes with peripheral components of the NPC [51]. In contrast to this predominant view, Karsten Weis (ETH Zurich, Switzerland) provided evidence for a Ran-dependent step for receptor interaction with FG repeats. Initial analyses revealed that the transport receptor importin β can dock at the NPC but cannot translocate in the absence of Ran. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments using permeabilized HeLa cells revealed the presence of ∼20 RanGTP-sensitive importin β-binding sites, several of which reside within the FG repeat Nup, Nup153. Moreover, importin β binding to the FG repeat region of Nup153 (Nup153FG) is dependent on RanGTP, as evidenced by the use of the GTPase-deficient Ran-Q69L variant. A Ran-dependent gate through the NPC would rectify the fact that the NPC FG rich core is not selective or directional. Whether this model is generally applicable to other transport receptors and FG Nups or if this Ran-dependent binding site is exclusive to Nup153 remains to be determined. Complementing these experiments, Edward Lemke (EMBL, Germany) provided a structural analysis of the Nup153FG-importin β complex through the combined use of single molecule-FRET (sm-FRET) [52] and molecular dynamics simulations. These analyses suggest that the Nup153FG region has a collapsed structure in contrast to the extended nature generally attributed to natively unfolded FG domains [38]. Moreover, the conformation of the structure was insensitive to binding of importin β. An interesting question to address will be whether RanGTP binding might promote a structural change to a natively unfolded state, in line with other FG repeat domains. Together these studies shed light on the mechanisms that ensure rapid yet selective transit through NPCs, a question that has been at the forefront of this field for many years.

Not All NPCs are Created Equal

A long-standing question in the field of nucleocytoplasmic transport is whether all NPCs within a given organism are equivalent and thus equally capable of mediating the entire spectrum of nuclear transport events. Classic experiments performed by Dr. Carl Feldherr in the 1980s demonstrated that gold particles of different sizes could be transported simultaneously into and out of a single NPC [53]. This experiment has been cited as evidence that all NPCs are competent for both import and export and sometimes extended to suggest that all NPCs within a given organism are equivalent. However, more recent findings bring this point of view into question. At the meeting, several researchers presented evidence that NPCs can differ from one another in specific tissues, organisms or developmental stages.

Perhaps the most striking evidence in support of NPC diversity came from Tokuko Haraguchi (National Institute of Information and Communications Technology, Japan) who reported on her studies in Tetrahymena. Tetrahymena contain two functionally and structurally distinct nuclei termed macronuclei (MAC) and micronuclei (MIC) [54]. Haraguchi's group used a biochemical approach to isolate the two nuclei and identify the Nups present in each form [55]. She reported that the isolated NPCs from the MAC and MIC nuclei have common core Nups and share similar overall architectures. However, she also described distinct differences including at least four Nup98 variants with two distinct forms of Nup98 present in each nucleus type [55, 56]. Such differences in composition could underlie some of the functional differences between these nuclei, which are not only distinct in size but also transcriptional activity and cell cycle control despite their presence in the same organism.

Interestingly, Nup98 also emerged as a protein of interest in work described by Geraint Parry (University of Liverpool, UK). His systematic efforts to define the function of Arabidopsis Nups using insertional mutagenesis have begun to reveal those Nups that are essential in this plant model and those that play key roles in specific processes [57]. His genetic studies reveal two distinct Nup98 genes encoding proteins that appear to participate in different functions. He reported that further work will be required to define the functions of these dual Nup98 proteins.

Two presentations addressed the related question of whether individual nuclei can have distinct functions within a given tissue. Kate Loveland (Monash University, Australia) presented studies that examine the expression and function of importin/karyopherin α family members during spermatogenesis [58]. These studies reveal clear functions for different family members throughout the course of differentiation, providing evidence that different transport receptors can confer distinct transport properties. Differences in import receptor expression levels also support a model where there are specific functions for importin/karyopherin α family members. For example, importin α2 levels are more than 2-fold higher in spermatocytes than in spermatids while no significant difference was observed for importin α4 [59] suggesting a model where demands for these receptors differ at specific developmental stages. In another presentation analyzing nuclear protein import in a specific cell type, Grace Pavlath (Emory University, USA) presented studies examining import of proteins into the individual nuclei of multi-nucleated muscle cells. Results from this analysis provide evidence that the distinct nuclei within multi-nucleated muscle cells can have different import competence from one another despite a common cytoplasm within the multi-nucleated muscle fiber. As her work employed in vitro transport assays where all soluble factors are supplied by exogenous, added cytosol [60], differences in import-competence must be linked to the nuclei, presumably the NPCs, rather than soluble transport receptors. Taken together, these studies provide evidence that differences in nuclear transport can occur both through regulation of the transport receptors and NPCs. The challenge is to define the mechanisms that underlie this regulation and then understand how such regulation may influence tissue-specific function(s).

Such work provides evidence that even within a given organism or cell type, not all NPCs are equivalent. Additional studies in these systems can provide more detailed insight into how transport mechanisms are controlled. Once the details of the permeability barrier function of NPCs are delineated, there will be additional work to define regulatory pathways that modulate the properties of the NPC in different contexts.

Translocation of Proteins to the Inner Nuclear Membrane (INM)

A molecular mechanism for integral nuclear membrane protein movement to the INM represents a major gap in the trafficking field. There are two major models for INM transport [61]: the diffusion-retention model [62] and the Kap-dependent model [63]. To define the mechanism for INM transport, Ulrike Kutay (ETH Zurich, Switzerland) presented an elegant strategy for measuring the rate of transport of an integral membrane protein reporter. This approach involved the knowledge that INM transport is size-dependent, with proteins bearing extra-luminal domains greater than 60 kDa unable to translocate through NPCs to the INM. This feature was exploited to uncouple membrane integration into the ER from transport to the INM. Reporter proteins were then rendered transport-competent by size reduction using protease cleavage in semi-permeabilized cells, allowing measurement of INM transport kinetics. Transport of two different reporter proteins derived from the INM proteins, Lamin B receptor (LBR) and SUN2 [64, 65], could be reconstituted by addition of a HeLa cell lysate and an energy-regenerating system. However, the INM reporter proteins translocate to the INM in the absence of karyopherins, suggesting that energy is required for a poorly-understood step in the process, perhaps to support mobility of cargo from their site of synthesis to the outer aspect of the NPC. RNAi of specific Nups revealed ‘leaking’ of the large LBR reporter into the INM, consistent with transport of membrane proteins being hindered by the central NPC scaffold. The Kutay group then utilized mathematical modeling to integrate the kinetic data. Their preliminary model revealed that targeting of LBR can, in principle, be described through a diffusion-retention mechanism. Further work is underway to bring together the results of this work into a comprehensive model for targeting and localization of INM proteins.

In support of a Kap-dependent model for INM transport, Gino Cingolani (Thomas Jefferson University, USA) provided evidence for a direct interaction between the NLS of the yeast INM protein, Heh2, and karyopherin Kap60 (importin α in vertebrates). Interestingly, binding studies revealed a complex series of mutually exclusive interactions between the Importin β-binding domain of Kap60, the NLS of Heh2, and the nucleoporin, Nup2. Moreover, Nup2 is required for proper localization of both full-length Heh2 [63] and a Heh2-NLS-containing membrane protein reporter to the INM. Future studies will reveal if there are multiple mechanisms for translocation of integral membrane proteins to the INM or if these alternative pathways represent divergent trafficking mechanisms between humans and fungi.

The NE, Lamins and LINC Complex

In multicellular eukaryotes, the INM is associated with a class of intermediate filaments called lamins. The proteins that make up the nuclear lamina, lamin A, B and C, were described almost 35 years ago [66]. Despite this fact, the precise function(s) of the nuclear lamins are not fully understood. Key clues into their molecular roles have come from the study of human lamin diseases called laminopathies, which point to roles in cellular signaling pathways as well as maintenance of nuclear architecture and NPC positioning within the NE [67]. Larry Gerace (The Scripps Institute, USA) presented evidence that the lam in-interacting protein Lem2 may be a key integrator for cell signaling pathways during myogenesis. Lem2 is one of four LEM domain proteins in humans (LAP2, emerin and Man1 are the other three). The LEM proteins are thought to carry out multiple functions, including playing roles in cell signaling [68]. Gerace's group demonstrated that knockdown of Lem2 in muscle cells results in a MEK1-dependent myogenic defect, indicating a deficiency in mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling (MAPK signaling). Interestingly, Yosef Gruenbaum (Hebrew University, Israel) connected the lamin network to mTOR signaling and regulation of fat content in C. elegans. He showed that this interplay is mediated through ATX-2, whose expression level is inversely proportional to body size [69]. Furthermore, the function of ATX-2 requires lamin, S6K and an intact mTOR signaling pathway. Because the mTOR pathway plays a major role in translational control [70], these data suggest that lamins may transmit signals not only to the gene expression network in the nucleus but also to the translational pool within the cytoplasm.

A complex of transmembrane proteins termed the LINC complex (linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton) spans the NE and connects the cytoplasmic cytoskeletal filaments with the lamin network [71]. Iris Meier (The Ohio State University, Ohio) presented an elegant complementary genetic and cell biological study connecting plant-specific LINC proteins to male fertility in Arabidopsis. The LINC complex is composed of SUN and KASH domain proteins, which are transmembrane proteins that interact with each other in the NE lumen and extend into the nucleus or cytoplasm, respectively [72, 73]. Arabidopsis encodes two plant-specific, KASH-like proteins called WIP1 and WIP2 (WPP-interacting proteins) [74]. Consistent with a role in nuclear membrane architecture, Meier reported that loss of the WIP proteins causes severe nuclear morphology defects. Furthermore, her group identified two additional NE proteins, termed WIT1 and WIT2 (WPP-interacting tail proteins) and demonstrated that the WIT proteins are required for pollen tube nuclear movement and sperm cell delivery [75]. Because simultaneous mutation of the two WIT and two WIP genes results in reduced seed formation, this discovery may have broad agricultural applications. Furthermore, a conserved role for LINC complexes in meiosis across eukaryotes [76], suggests that insights from this model system will contribute to our knowledge of fertility defects in humans.

Messenger RNA Processing, Assembly and Export

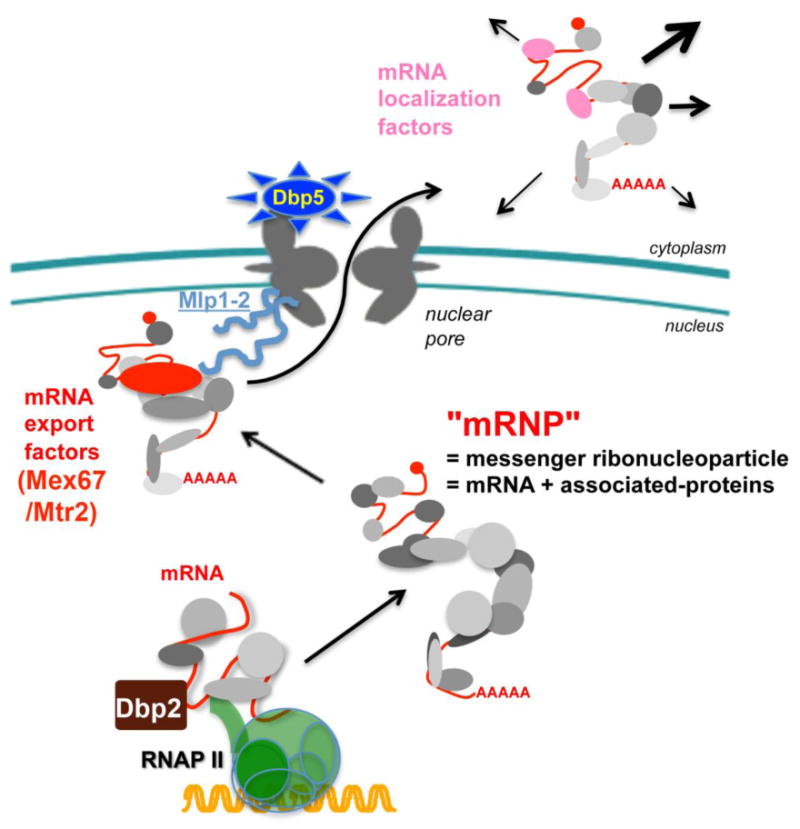

Transport receptor-mediated mechanisms move most soluble proteins, small RNAs and ribosomes through NPCs. In contrast, messenger RNA (mRNA) export is not dependent on any exportin/karyopherin or Ran [51]. Rather, mRNA export requires recruitment of the mRNA export receptor Mex67 in fungi (Tap or NXF1 in multicellular eukaryotes) and a heterodimerization partner, Mtr2 (p15 or NXT1), whose binding to mRNA is dependent on proper pre-mRNA processing in the nucleus (Figure 5). Recruitment of Mex67/Mtr2 in multicellular eukaryotes is highly linked to splicing [77] and 5′ capping [78] or specific recruitment sequences [79, 80], whereas, in budding yeast, recruitment is dependent on multiple processing steps [81] that are thought to be linked to accurate termination and 3′ end formation[82], although defining mechanisms that underlie this coordination remains an area of active investigation [83]. Because Mex67/Mtr2 lacks the ability to recognize RNA directly, recruitment is accomplished through interaction with other RNA-binding proteins such as Yra1 (Aly in humans) [84, 85], Npl3 [86, 87], and Nab2 [88, 89]. Many questions about how adaptor recruitment and assembly is coordinated with assembly of an export-competent mRNP remain. While some studies show recruitment of different factors at specific stages of maturation, e.g., splicing, termination, polyadenylation (Figure 5), other work shows that Mex67 is recruited co-transcriptionally [90]. The coupling of mRNA maturation with nuclear transport provides a layer of quality control to the gene expression process by preventing translation of potentially deleterious gene products [91, 92]. Following recruitment of Mex67/Mtr2 to a given mRNA, the complex docks at the NPC and then migrates through the channel via interaction of Mex67/Mtr2 with FG Nups [93]. The mRNA export receptor-cargo complex is disassembled at the cytoplasmic face of the NPC through the action of the ATPase and RNA helicase, Dbp5, which triggers release of Mex67/Mtr2 from the mRNA in a manner analogous to the role of Ran in transport receptor-dependent export [87, 89].

Figure 5. Messenger RNA (mRNA) assembly is required for transport through the NPC (provided by Benoit Palancade).

Export-competent mRNAs are assembled in the nucleus during transcription and mRNA processing steps. This includes binding of transport adaptor proteins such as Yra1, Npl3 and Nab2 to mRNA. These adaptor proteins (shown in gray) recruit the mRNA export receptor heterodimer, Mex67/Mtr2 (TAP/p15 in mammals), and facilitate docking of the mRNA-protein complex (mRNP) with the proteins at the nuclear face of the NPC (i.e., Mlp1/2) [145]. Direct binding of Mex67/Mtr2 to FG repeats within the NPC facilitates movement of the mRNP to the cytoplasm where the activity of the RNA helicase Dbp5 promotes mRNP remodeling and release into the cytoplasm. Proteins that remain associated with the mRNP in the cytoplasm can then influence mRNA stability, cellular localization and/or translational efficiency of the message.

Whereas the identity of the factors that are required for efficient mRNA export is established, the mechanisms for choreographing the numerous sequential steps in formation of an export-competent mRNP are not well understood. These steps include capping, pre-mRNA splicing, termination and polyadenylation, all of which have been linked to mRNP assembly and efficient export through the NPC (Figure 5). Elizabeth Tran (Purdue University, USA) presented evidence that the RNA helicase Dbp2 in budding yeast (p68/DDX5 in humans) controls RNA structure during transcription. Dbp2 is an active helicase in vitro that associates directly with transcribed chromatin [94, 95]. Moreover, Dbp2 is required for efficient assembly of Yra1 and Mex67 onto mRNAs as well as for efficient transcription termination. A model was presented whereby Dbp2 controls RNA folding during transcription to prevent the formation of RNA structures refractory to mRNP assembly, suggesting that RNA structure may add an additional layer of complexity to the mRNA export process.

To examine the regulation of key steps in assembly of export-competent mRNPs and interactions with the NPC during docking and export, Catherine Dargemont (Hospital Saint Louis, Paris, France) and Benoit Palancade (Institut Jacques Monod- Paris, France) explored the role of post-translational modifications [96] [97, 98]. Dargemont reported on her studies to examine post-translational modifications of Nups. Her work revealed interplay between ubiquitin and SUMO modification of Nup60 that is linked to cell cycle progression. Using a newly developed spinach aptamer-based mRNA visualization method in living yeast [99], Dargemont showed that specific post-translational modifications of Nup60 are involved in nuclear export of polarized mRNAs. Understanding how these modifications modulate the function of the NPC and defining the fraction of Nups modified at any given time remains a goal of her research. In contrast to examining modification of Nups, Palancade analyzed the requirement for SUMO modification of RNA binding proteins within mRNP export complexes. His group exploited budding yeast mutants of the Ulp1 SUMO protease [100] coupled with a proteomic approach to identify changes in mRNP complexes when SUMO modification is impaired. While several complexes analyzed were unaffected by this perturbation, Palancade reported specific changes in association of the THO complex with mRNPs. Further studies identified a specific class of stress-response RNAs that showed altered levels in the absence of SUMO modification [101]. These studies lay the groundwork for understanding how SUMO modification as well as other post-translational modifications modulates biogenesis and export of specific classes of mRNAs. Such experiments also highlight the question of whether specific RNA binding proteins mediate export of classes of mRNAs or whether a core cadre of mRNA export factors is required for all mRNA transcripts. These are future challenges for the field.

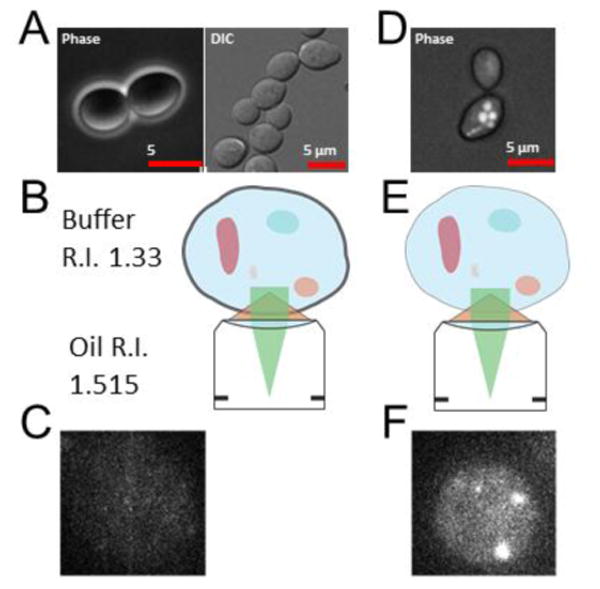

Once mature mRNPs are assembled within the nucleus, there is great interest in understanding the kinetics of the export of these complexes. Single transcript analyses of mRNA export have revealed that the docking and release steps are rate limiting for mRNA export [102]. Furthermore, mRNAs scan along the NE prior to export [103]. However, these studies have largely been performed in mammalian tissue culture systems. David Grünwald (University of Massachusetts Medical School, USA) reported on attempts from his lab, Karsten Weis' lab and Ben Montpetit's lab (University of Alberta, Canada) to combine the power of S. cerevisiae genetics with single transcript studies. Their team is focused on determining the kinetics of mRNA export in the budding yeast system and the impact that mutations in various export factors have on NE scanning, docking, transport, and release. To accomplish this goal, these laboratories have worked to develop a microscopy method to analyze the movement of individual transcripts in living yeast cells (Figure 6). Preliminary data suggest that mRNAs are rapidly exported following their interaction with the NE and these mRNAs do not exhibit observable NE scanning in wild type yeast cells. However, cells harboring mutations in the genes encoding either the RNA helicase, Dbp5 [104], or the cytoplasmic nucleoporin, Nup159 [105], display increased NE scanning events. This finding suggests that scanning may be an indicator of slower or inefficient mRNA export in these mutants. Furthermore, Grünwald noted that transcripts can be re-imported into the nucleus following initial transport into the channel in dbp5 and nup159 mutant cells, supporting the idea that mRNAs can move bi-directionally within the NPC [102]. The model that emerges from this study is that failure of Dbp5 to remodel the exported mRNP on the cytoplasmic side of the NPC and remove export factors, such as Mex67/Mtr2, allows for re-import. His group is now expanding their analysis to include other mRNA export mutants with the hopes of building a spatiotemporal model of when and where these various mRNA export factors function.

Figure 6. Improved methods for imaging single mRNA molecules in S. cerevisiae (provided by David Grünwald).

A. Budding yeast cells imaged in buffer show high contrast in Phase and DIC. B. Refractive Index (R.I.) differences between immersion and buffer are high for use of high N.A. objectives leading to a loss of emission light. The R.I. of yeast cells is unknown. C. Consequently, at viable excitation light power mRNA fluorescent signal from mRNA in the budding yeast cell is very dim. D & E. Modification of imaging conditions leads to reduced contrast in Phase (DIC contrast does not yield image) resulting in (F) improved mRNA signal for low light imaging.

Cytoplasmic events such as translational control and mRNA degradation can also be coupled to mRNA export. Susana Rodriguez-Navarro (Principe Felipe Research Institute, Spain) provided characterization of a largely unstudied Mex67/Mtr2-adaptor protein in budding yeast called Mip6. Mip6 was originally identified as a Mex67-interacting protein (MIP) in a yeast two-hybrid screen [106]. However, the role of Mip6 in mRNA export was not defined. Rodriguez-Navarro showed that Mip6 shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm in a Mex67-dependent manner, suggesting a possible role in mRNA export. However, deletion of MIP6 did not cause accumulation of poly(A) RNA within the nucleus, inconsistent with a general mRNA export role. Instead, Rodriguez-Navarro found that the Mip6 protein accumulated in heat-induced stress granules in response to heat shock. These observations suggest that Mip6 may couple mRNA export with translational control.

These studies highlight some of the complexities of defining the molecular nature of export-competent mRNPs, the selectivity for export of mature mRNPs through the NPC and the remodeling necessary to prepare the exported mRNAs for a productive life in the cytoplasm. Layered on top of these basic questions are several issues including whether all mRNAs are packaged and exported in the same manner and how these pathways are controlled. Cutting-edge approaches will continue to address these questions as there is still much to learn.

Transcriptional Control at the NPC

Both the NPC and the NE associate with transcriptionally active and repressed genes, suggesting that factors at the nuclear periphery contribute to control of gene expression [107, 108]. This control could be accomplished by regulation of transcription factors and/or chromatin structure to alter the accessibility for RNA Polymerase II (RNAP II). Studies in a number of different model systems have documented the re-localization of inducible genes from the nucleoplasm to the nuclear periphery upon transcriptional activation, suggesting a link between transcriptional induction and NPC association [109]. Both Francoise Stutz (University of Geneva, Switzerland) and Richard Wozniak (University of Alberta, Canada) provided evidence that this process involves a cycle of SUMOylation. Using the galactose-inducible GAL1 gene in budding yeast, the Stutz laboratory found that the NPC-associated SUMO protease Ulp1 [100] is required for normal induction of the GAL1 gene. The GAL1 transcriptional co-repressor Ssn6 is a target of Ulp1 deSUMOylation, suggesting that recruitment of the GAL1 gene to the NPC contributes to optimal activation kinetics by favoring deSUMOylation of chromatin-associated factors [110]. Richard Wozniak then showed that both SUMOylation and deSUMOylation (also mediated by Ulp1) events are necessary for NPC targeting of the inducible gene INO1 in budding yeast. For example, cells that express a Ulp1 mutant that does not associate with NPCs exhibited both drastic decreases in INO1 recruitment to the NPC and reduced INO1 transcription. Taken together, these studies suggest that changes in the SUMOylation state of chromatin-associated proteins regulate NPC targeting and the transcriptional state of inducible genes.

A unique mechanism for transcriptional control at the NPC is the modulation of gene expression through epigenetic memory, an area of research largely pioneered by Jason Brickner (Northwestern University, USA). The concept of transcriptional memory first originated from the observation that genes are more rapidly re-activated in subsequent rounds of induction than the first activation event [111, 112]. This activity is associated with movement of inducible genes to the NPC, suggesting that specific elements within the chromatin may be involved in memory. The Brickner lab has been exploring the DNA sequences responsible for the inducible association of target genes with the NPC. These sequences, called ‘zip codes’, are found in the INO1, TSA2, and HSP104 genes of S. cerevisiae [113]. Strikingly, Brickner presented evidence that epigenetic memory also occurs in human cells at the Interferon γ gene [114]. Using HeLa cells as a model system, he showed that the Interferon γ gene is more rapidly reactivated as compared to the initial activation event consistent with prior work in budding yeast [115]. Moreover, this rapid reactivation is associated with retention of RNAP II at the gene even after transcriptional shut off. RNAP II retention requires Nup98 as well as the H3K4me2 histone methylation mark catalyzed by MLL1 (Set1 in S. cerevisiae). Interestingly, INO1 epigenetic memory in yeast also requires H3K4me2, the Nup98 ortholog, Nup100, as well as the histone deacetylase Set3. Because the Set3-containing complex, Set3C, recognizes the H3K2me2 modification [116], Brickner proposed that histone dimethylation and subsequent deacetylation are essential for the transcriptional memory process. These findings suggest that heritable epigenetic states are controlled through physical association of the NPC with chromatin [117], representing an emerging area of research ripe for future discoveries.

Emerging Connections between Nucleocytoplasmic Transport and Human Disease

For some time, laminopathies have represented one of the most established link between nuclear transport/structure and disease [118, 119]. At this meeting, however, a number of new connections emerged including those with potentially exciting clinical implications. Dr. Yosef Landesman from Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc. presented recent research on Selective Inhibitors of Nuclear Export (SINE), compounds that target protein export from the nucleus, which have shown promising results for treatment of variety of human medical conditions. Potential targets include both hematological and solid malignancies [120]. Specifically, he presented evidence on Selinexor, a SINE compound, which shows promising results for treatment of several types of cancers [121, 122]. These promising results provide evidence that nuclear transport pathways can be druggable targets for therapeutic intervention and set the stage for further exploration of nuclear transport pathways as potential therapeutic targets.

A number of the emerging connections link mRNA processing/export to human disease [123, 124]. Susan Wente (Vanderbilt University, USA) spoke of her recent structure-function studies of the evolutionarily conserved Gle1 protein [125, 126]. Gle1 plays a key role in RNA export from the nucleus through modulating the DEAD box RNA helicase, Dbp5 [104, 127, 128], during mRNP remodeling upon nuclear export [87, 89] at the cytoplasmic face of the NPC (Figure 5; [129, 130]). In recent years, mutations in GLE1 have been linked to several devastating autosomal recessive diseases with tissue-specific consequences [131]. These diseases include lethal congenital contracture syndrome 1 (LCCS-1) and lethal arthrogryposis with anterior horn cell disease (LAAHD), which ultimately result in fetal death. Wente reported on experiments that used structure-function approaches to assess the functional consequences of specific mutations identified in patients. These studies reveal how a mutation in GLE1 termed FinMajor, which is named due to high prevalence in the Finnish population, causes production of a Gle1 protein with an altered capacity for nucleocytoplasmic transport. She also reported that human Gle1 can form higher order complexes and utilized a CryoEM approach to assess how alterations within the Gle1 protein impact this self-association [125]. Such studies that combine multiple approaches to assess the functional consequences of patient mutations provide insight not only into the defects that underlie the human disease but also into mechanisms critical for nuclear transport.

The example of mutations in GLE1 that cause tissue-specific disease is just one examples of genes that encode ubiquitously expressed RNA binding proteins which are mutated in tissue-specific disease [132]. Another example is spinal muscular atrophy, a motor neuron disease caused by mutation in the human SMN gene [133], which is required for spliceosome assembly and hence implicated in global splicing events. Anita Corbett (Emory University) described work relevant to two additional examples where alteration of ubiquitously expressed RNA binding proteins leads to tissue-specific disease. Her presentation touched on the ubiquitously expressed, nuclear, polyadenosine RNA binding protein, PABPN1, which is mutated in oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy [134], and then described more detailed efforts to define the role of another polyadenosine RNA binding protein, Nab2/ZC3H14 [135, 136]. Whereas the S. cerevisiae Nab2 protein is essential for viability [137], mutation of human ZC3H14 causes an autosomal recessive form of intellectual disability [136, 138]. A Drosophila loss-of-function model has been of significant value in demonstrating that Nab2/ZC3H14 function is most critical in neurons, consistent with the brain-specific phenotype in patients [138, 139]. This model also reveals aberrant brain morphology, suggestive of axon guidance defects. As with other cases where mutations in such ubiquitously expressed RNA processing/export factors lead to tissue-specific consequences, the challenge is both to define what could be a multitude of functions and then subsequently understand the critical requirement for those functions within the relevant tissue.

Other links between human disease and RNA export processing extended both into the nucleus and to the cytoplasmic translation machinery. Kathy Borden (University of Montreal, Canada) reported on how deregulation of the eIF4E protein, which is traditionally thought of as a key translation initiation factor [140], can contribute to defects in numerous steps of gene expression. Mechanistic studies of eIF4E are of critical importance as eIF4E is overexpressed in 30% of human cancers [141]. Borden showed evidence that eIF4E is a shuttling protein that is exported from the nucleus in an mRNA export-dependent manner. Her work suggests that nuclear functions of eIF4E could contribute to the oncogenic potential of eIF4E. She also reported on their identification of the previously unknown import receptor for eIF4E. An important extension of this work is an effort to define the mechanism by which ribavirin triphosphate, the only direct inhibitor of eIF4E to reach Phase II clinical trials for acute myeloid leukemia, impairs the function of eIF4E [142].

With the expanded ability to define the specific mutations that underlie human diseases, many of the key players involved in the critically important processes broadly termed nuclear transport are likely to be implicated. Such mutations may have very specific consequences, as complete loss of function of many of these vital factors would likely not be compatible with life. The lamins, however, provide an example of how distinct changes within a family of proteins can cause diverse disease phenotypes.

Future Challenges

As technology advances, our ability to peer into the NPC has grown exponentially, shifting the field from viewing the NPC as a static structure embedded within the nuclear envelope, to a dynamic macromolecular complex for exquisite control of nuclear transport, cell signaling and gene expression. These advances add new and exciting challenges to the transport field while simultaneously pinpointing the gaps in our knowledge regarding the fundamental process of transport into and out of the nucleus. Some of the basic mechanistic questions that remain to be addressed include: can multiple cargoes can be simultaneously transported through a single NPC at the same time in a bidirectional manner or, alternatively, are individual NPCs dedicated to specific transport events? If NPCs are transport event-specific, this property could provide an explanation for why NPC composition varies across organisms and tissues. Understanding the biophysical parameters of the NPC permeability barrier is also of key importance. Whereas FG domains are clearly critical for transport, these regions are non-selective and inefficient. Moreover, as eloquently stated by Dirk Görlich, it is paradoxical that energy-dependent, receptor-mediated transport of cargoes is faster than diffusion through the NPC. More analysis is necessary to define the rules for transport selectivity and determine the generality to specific transport events.

The NPC is clearly a core integrator for multiple, biochemically distinct nuclear processes. Thus, a future goal is to determine how different modes of regulation influence one another. For example, how or whether global regulation of transport receptors impacts mRNP assembly or the many subsequent steps in gene expression is not yet known. Given the intimate connectivity between these processes and the NPC, there is likely to be a high degree of synergy at both the cellular and molecular level. Uncovering the molecular connections that link early and late steps in gene expression with mechanisms for transport through the NPC and regulation of that transport will be necessary to determine the underlying basis for human diseases linked to defective NPC components, transport receptors, and/or NE integrity. The future of the nuclear transport field is bright with the prospects of novel discoveries, unique interdisciplinary collaborations, and applications to biomedical research.

Highlights.

Summary of the 2013 Mechanisms of Nuclear Transport Meeting

Insights into the overall architecture and function of the nuclear pore complex

Mechanisms by which cargo molecules are transported into and out of the nucleus

Links between the nuclear pore complex and gene expression including mRNA export

Emerging connections between nuclear transport pathways and human disease

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to Thomas Schwartz (MIT, USA) and Karsten Weis (ETH Zurich, Switzerland) for organizing an outstanding meeting. We also thank all of our colleagues in the field for sharing unpublished information. We apologize to those colleagues whose work is not specifically mentioned due to the space limitations.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Raices M, D'Angelo MA. Nuclear pore complex composition: a new regulator of tissue-specific and developmental functions. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2012;13:687–699. doi: 10.1038/nrm3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grossman E, Medalia O, Zwerger M. Functional architecture of the nuclear pore complex. Annual review of biophysics. 2012;41:557–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wente SR, Rout MP. The nuclear pore complex and nuclear transport. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2010;2:a000562. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez-Martinez J, Rout MP. A jumbo problem: mapping the structure and functions of the nuclear pore complex. Current opinion in cell biology. 2012;24:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rout MP, Aitchison JD, Suprapto A, Hjertaas K, Zhao Y, Chait BT. The yeast nuclear pore complex: composition, architecture, and transport mechanism. The Journal of cell biology. 2000;148:635–651. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alber F, Dokudovskaya S, Veenhoff LM, Zhang W, Kipper J, Devos D, Suprapto A, Karni-Schmidt O, Williams R, Chait BT, Sali A, Rout MP. The molecular architecture of the nuclear pore complex. Nature. 2007;450:695–701. doi: 10.1038/nature06405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez-Martinez J, Phillips J, Sekedat MD, Diaz-Avalos R, Velazquez-Muriel J, Franke JD, Williams R, Stokes DL, Chait BT, Sali A, Rout MP. Structure-function mapping of a heptameric module in the nuclear pore complex. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;196:419–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201109008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siniossoglou S, Wimmer C, Rieger M, Doye V, Tekotte H, Weise C, Emig S, Segref A, Hurt EC. A novel complex of nucleoporins, which includes Sec13p and a Sec13p homolog, is essential for normal nuclear pores. Cell. 1996;84:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80981-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brohawn SG, Partridge JR, Whittle JR, Schwartz TU. The nuclear pore complex has entered the atomic age. Structure. 2009;17:1156–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solmaz SR, Blobel G, Melcak I. Ring cycle for dilating and constricting the nuclear pore. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:5858–5863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302655110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stuwe T, Lina DH, Collins LN, Hurt E, Hoelz A. Evidence for an evolutionary relationship between the large adaptor nucleoporin Nup192 and karyopherins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:2530–2535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311081111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sampathkumar P, Kim SJ, Upla P, Rice WJ, Phillips J, Timney BL, Pieper U, Bonanno JB, Fernandez-Martinez J, Hakhverdyan Z, Ketaren NE, Matsui T, Weiss TM, Stokes DL, Sauder JM, Burley SK, Sali A, Rout MP, Almo SC. Structure, dynamics, evolution, and function of a major scaffold component in the nuclear pore complex. Structure. 2013;21:560–571. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen KR, Onischenko E, Tang JH, Kumar P, Chen JZ, Ulrich A, Liphardt JT, Weis K, Schwartz TU. Scaffold nucleoporins Nup188 and Nup192 share structural and functional properties with nuclear transport receptors. eLife. 2013;2:e00745. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conti E, Muller CW, Stewart M. Karyopherin flexibility in nucleocytoplasmic transport. Current opinion in structural biology. 2006;16:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conti E, Uy M, Leighton L, Blobel G, Kuriyan J. Crystallographic analysis of the recognition of a nuclear localization signal by the nuclear import factor karyopherin alpha. Cell. 1998;94:193–204. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81419-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vetter IR, Arndt A, Kutay U, Gorlich D, Wittinghofer A. Structural view of the Ran-Importin beta interaction at 2.3 A resolution. Cell. 1999;97:635–646. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80774-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cingolani G, Petosa C, Weis K, Muller CW. Structure of importin-beta bound to the IBB domain of importin-alpha. Nature. 1999;399:221–229. doi: 10.1038/20367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams RL, Wente SR. Uncovering nuclear pore complexity with innovation. Cell. 2013;152:1218–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bui KH, von Appen A, DiGuilio AL, Ori A, Sparks L, Mackmull MT, Bock T, Hagen W, Andres-Pons A, Glavy JS, Beck M. Integrated structural analysis of the human nuclear pore complex scaffold. Cell. 2013;155:1233–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck M, Lucic V, Forster F, Baumeister W, Medalia O. Snapshots of nuclear pore complexes in action captured by cryo-electron tomography. Nature. 2007;449:611–615. doi: 10.1038/nature06170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiserova J, Goldberg MW. Relationships at the nuclear envelope: lamins and nuclear pore complexes in animals and plants. Biochemical Society transactions. 2010;38:829–831. doi: 10.1042/BST0380829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck M, Glavy JS. Toward understanding the structure of the vertebrate nuclear pore complex. Nucleus. 2014;5 doi: 10.4161/nucl.28739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu D, Farmer A, Chook YM. Recognition of nuclear targeting signals by Karyopherin-beta proteins. Current opinion in structural biology. 2010;20:782–790. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guttler T, Gorlich D. Ran-dependent nuclear export mediators: a structural perspective. The EMBO journal. 2011;30:3457–3474. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lange A, Mills RE, Lange CJ, Stewart M, Devine SE, Corbett AH. Classical nuclear localization signals: definition, function, and interaction with importin alpha. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:5101–5105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600026200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kutay U, Guttinger S. Leucine-rich nuclear-export signals: born to be weak. Trends in cell biology. 2005;15:121–124. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee SJ, Matsuura Y, Liu SM, Stewart M. Structural basis for nuclear import complex dissociation by RanGTP. Nature. 2005;435:693–696. doi: 10.1038/nature03578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ossareh-Nazari B, Bachelerie F, Dargemont C. Evidence for a role of CRM1 in signal-mediated nuclear protein export. Science. 1997;278:141–144. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stade K, Ford CS, Guthrie C, Weis K. Exportin 1 (Crm1p) is an essential nuclear export factor. Cell. 1997;90:1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fornerod M, Ohno M, Yoshida M, Mattaj IW. CRM1 is an export receptor for leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Cell. 1997;90:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quimby BB, Dasso M. The small GTPase Ran: interpreting the signs. Current opinion in cell biology. 2003;15:338–344. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marelli M, Dilworth DJ, Wozniak RW, Aitchison JD. The dynamics of karyopherin-mediated nuclear transport. Biochemistry and cell biology = Biochimie et biologie cellulaire. 2001;79:603–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee BJ, Cansizoglu AE, Suel KE, Louis TH, Zhang Z, Chook YM. Rules for nuclear localization sequence recognition by karyopherin beta 2. Cell. 2006;126:543–558. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suel KE, Gu H, Chook YM. Modular organization and combinatorial energetics of proline-tyrosine nuclear localization signals. PLoS biology. 2008;6:e137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohr D, Frey S, Fischer T, Guttler T, Gorlich D. Characterisation of the passive permeability barrier of nuclear pore complexes. The EMBO journal. 2009;28:2541–2553. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terry LJ, Wente SR. Flexible gates: dynamic topologies and functions for FG nucleoporins in nucleocytoplasmic transport. Eukaryotic cell. 2009;8:1814–1827. doi: 10.1128/EC.00225-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel SS, Belmont BJ, Sante JM, Rexach MF. Natively unfolded nucleoporins gate protein diffusion across the nuclear pore complex. Cell. 2007;129:83–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denning DP, Patel SS, Uversky V, Fink AL, Rexach M. Disorder in the nuclear pore complex: the FG repeat regions of nucleoporins are natively unfolded. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:2450–2455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437902100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frey S, Richter RP, Gorlich D. FG-rich repeats of nuclear pore proteins form a three-dimensional meshwork with hydrogel-like properties. Science. 2006;314:815–817. doi: 10.1126/science.1132516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tu LC, Fu G, Zilman A, Musser SM. Large cargo transport by nuclear pores: implications for the spatial organization of FG-nucleoporins. The EMBO journal. 2013;32:3220–3230. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tetenbaum-Novatt J, Hough LE, Mironska R, McKenney AS, Rout MP. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: a role for nonspecific competition in karyopherin-nucleoporin interactions. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2012;11:31–46. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.013656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hulsmann BB, Labokha AA, Gorlich D. The permeability of reconstituted nuclear pores provides direct evidence for the selective phase model. Cell. 2012;150:738–751. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moussavi-Baygi R, Jamali Y, Karimi R, Mofrad MR. Brownian dynamics simulation of nucleocytoplasmic transport: a coarse-grained model for the functional state of the nuclear pore complex. PLoS computational biology. 2011;7:e1002049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weis K. The nuclear pore complex: oily spaghetti or gummy bear? Cell. 2007;130:405–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ribbeck K, Gorlich D. Kinetic analysis of translocation through nuclear pore complexes. The EMBO journal. 2001;20:1320–1330. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ribbeck K, Gorlich D. The permeability barrier of nuclear pore complexes appears to operate via hydrophobic exclusion. The EMBO journal. 2002;21:2664–2671. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Labokha AA, Gradmann S, Frey S, Hulsmann BB, Urlaub H, Baldus M, Gorlich D. Systematic analysis of barrier-forming FG hydrogels from Xenopus nuclear pore complexes. The EMBO journal. 2013;32:204–218. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schoch RL, Kapinos LE, Lim RY. Nuclear transport receptor binding avidity triggers a self-healing collapse transition in FG-nucleoporin molecular brushes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:16911–16916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208440109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kapinos LE, Schoch RL, Wagner RS, Schleicher KD, Lim RY. Karyopherin-centric control of nuclear pores based on molecular occupancy and kinetic analysis of multivalent binding with FG nucleoporins. Biophysical journal. 2014;106:1751–1762. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schleicher KD, Dettmer SL, Kapinos LE, Pagliara S, Keyser UF, Jeney S, Lim RYH. Selective transport control on molecular velcro made from intrinsically disordered proteins. Nature Nanotechnology. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.103. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stewart M. Nuclear export of mRNA. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2010;35:609–617. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tyagi S, Vandelinder V, Banterle N, Fuertes G, Milles S, Agez M, Lemke EA. Continuous throughput and long-term observation of single-molecule FRET without immobilization. Nature methods. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feldherr CM, Akin D. The location of the transport gate in the nuclear pore complex. Journal of cell science. 1997;110(Pt 24):3065–3070. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.24.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Orias E, Cervantes MD, Hamilton EP. Tetrahymena thermophila, a unicellular eukaryote with separate germline and somatic genomes. Research in microbiology. 2011;162:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iwamoto M, Mori C, Kojidani T, Bunai F, Hori T, Fukagawa T, Hiraoka Y, Haraguchi T. Two distinct repeat sequences of Nup98 nucleoporins characterize dual nuclei in the binucleated ciliate tetrahymena. Current biology : CB. 2009;19:843–847. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iwamoto M, Asakawa H, Hiraoka Y, Haraguchi T. Nucleoporin Nup98: a gatekeeper in the eukaryotic kingdoms. Genes to cells : devoted to molecular & cellular mechanisms. 2010;15:661–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parry G. Assessing the function of the plant nuclear pore complex and the search for specificity. Journal of experimental botany. 2013;64:833–845. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miyamoto Y, Baker MA, Whiley PA, Arjomand A, Ludeman J, Wong C, Jans DA, Loveland KL. Towards delineation of a developmental alpha-importome in the mammalian male germline. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1833:731–742. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arjomand A, Baker MA, Li C, Buckle AM, Jans DA, Loveland KL, Miyamoto Y. The alpha-importome of mammalian germ cell maturation provides novel insights for importin biology. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2014 doi: 10.1096/fj.13-244913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adam SA, Sterne-Marr R, Gerace L. In vitro nuclear protein import using permeabilized mammalian cells. Methods in cell biology. 1991;35:469–482. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Antonin W, Ungricht R, Kutay U. Traversing the NPC along the pore membrane: targeting of membrane proteins to the INM. Nucleus. 2011;2:87–91. doi: 10.4161/nucl.2.2.14637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Worman HJ, Courvalin JC. The inner nuclear membrane. The Journal of membrane biology. 2000;177:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s002320001096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.King MC, Lusk CP, Blobel G. Karyopherin-mediated import of integral inner nuclear membrane proteins. Nature. 2006;442:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature05075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ollins AL, Rhodes G, Welch DB, Zwerger M, Ollins DE. Lamin B receptor: multitasking at the nuclear envelope. Nucleus. 2010;1:53–70. doi: 10.4161/nucl.1.1.10515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Luxton GW, Gomes ER, Folker ES, Worman HJ, Gundersen GG. TAN lines: a novel nuclear envelope structure involved in nuclear positioning. Nucleus. 2011;2:173–181. doi: 10.4161/nucl.2.3.16243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fawcett DW. On the occurrence of a fibrous lamina on the inner aspect of the nuclear envelope in certain cells of vertebrates. The American journal of anatomy. 1966;119:129–145. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001190108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schreiber KH, Kennedy BK. When lamins go bad: nuclear structure and disease. Cell. 2013;152:1365–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huber MD, Guan T, Gerace L. Overlapping functions of nuclear envelope proteins NET25 (Lem2) and emerin in regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in myoblast differentiation. Molecular and cellular biology. 2009;29:5718–5728. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00270-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kiehl TR, Nechiporuk A, Figueroa KP, Keating MT, Huynh DP, Pulst SM. Generation and characterization of Sca2 (ataxin-2) knockout mice. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2006;339:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ma XM, Blenis J. Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2009;10:307–318. doi: 10.1038/nrm2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sosa BA, Rothballer A, Kutay U, Schwartz TU. LINC complexes form by binding of three KASH peptides to domain interfaces of trimeric SUN proteins. Cell. 2012;149:1035–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rothballer A, Schwartz TU, Kutay U. LINCing complex functions at the nuclear envelope: what the molecular architecture of the LINC complex can reveal about its function. Nucleus. 2013;4:29–36. doi: 10.4161/nucl.23387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhou X, Meier I. How plants LINC the SUN to KASH. Nucleus. 2013;4:206–215. doi: 10.4161/nucl.24088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou X, Graumann K, Evans DE, Meier I. Novel plant SUN-KASH bridges are involved in RanGAP anchoring and nuclear shape determination. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;196:203–211. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhao Y, Meier I. Efficient plant male fertility depends on vegetative nuclear movement mediated by two families of plant outer nuclear membrane proteins. Proceedings of National Academy of Science, USA. 2014 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323104111. published ahead of print July 29, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stewart CL, Burke B. The missing LINC: A mammalian KASH-domain protein coupling meiotic chromosomes to the cytoskeleton. Nucleus. 2014;5:3–10. doi: 10.4161/nucl.27819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Valencia P, Dias AP, Reed R. Splicing promotes rapid and efficient mRNA export in mammalian cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:3386–3391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800250105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cheng H, Dufu K, Lee CS, Hsu JL, Dias A, Reed R. Human mRNA export machinery recruited to the 5′ end of mRNA. Cell. 2006;127:1389–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lei H, Zhai B, Yin S, Gygi S, Reed R. Evidence that a consensus element found in naturally intronless mRNAs promotes mRNA export. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41:2517–2525. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moore MJ, Proudfoot NJ. Pre-mRNA processing reaches back to transcription and ahead to translation. Cell. 2009;136:688–700. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vitaliano-Prunier A, Babour A, Herissant L, Apponi L, Margaritis T, Holstege FC, Corbett AH, Gwizdek C, Dargemont C. H2B ubiquitylation controls the formation of export-competent mRNP. Molecular cell. 2012;45:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]