Abstract

Background:

Leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease, is caused by the Leishmania genus, a protozoan parasite transmitted by sand fly arthropods. Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) in old world is usually caused by L. major, L. tropica, and L. aethiopica complexes. One of the most important hyper endemic areas of CL in Iran is Isfahan province. Varzaneh is a city in the eastern part of Isfahan province. Due to different biological patterns of parasite strains which are distributed in the region, this study was design to identify Leishmania species from human victims using Kinetoplastid DNA as templates in a molecular PCR method.

Materials and Methods:

Among 186 suspected cases, 50 cases were confirmed positive by direct microscopy after Giemsa staining. Species characterization of the isolates was done using Nested- PCR as a very effective and sensitive tool to reproduce mini circle strands.

Results:

After Nested-PCR from all 50 cases, 560 bp bands were produced which according to products of reference strains indicate that the infection etiologic agent has been L. major. 22 (44%) of patients were females and 28 (56%) of them were males. Their age ranges were between 7 months and 60 years.

Conclusion:

According to the results of the study and the particular pattern of infection prevalent in the region, genetic studies and identification of Leishmania parasites are very important in the disease control and improvement of regional strategy of therapy protocols.

Keywords: Leishmania, nested-PCR, parasites

INTRODUCTION

Leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease, is caused by the Leishmania genus, a protozoan parasite transmitted by sand fly arthropods.[1] The disease is endemic in many tropical and subtropical regions in more than 88 countries worldwide. About 20 species of Leishmania parasites have been reported yet in human involvement. These species can lead to various clinical forms of leishmaniasis including visceral, cutaneous, and mucocutaneous.[2,3]

CL in old world is usually caused by L. major, L. tropica, and L. aethiopica complexes. In old world, 90% of cases were reported from Iran, Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Syria, and Algeria.[4,5] In Iran, the majority of CL are caused by L. major and L. tropica which are endemic in northern eastern, northern western, and central regions of the country.[6,7] One of the most important hyper endemic areas in Iran is Isfahan province. Varzaneh is a city in the eastern part of the province. Varzaneh is located at longitude 39’, 52° east and latitude 25’, 52° north. The city stands in the western part of Gavkhooni bog and is known as an endemic area of CL. The current population of the city is approximately 14,000.

In some reported cases from Varzaneh, the disease has had complex forms which were long lasting and non-healed. In addition, in the previous findings, it was experienced that parasites were thinly scattered on smears from patients. Therefore, identification of isolates is of great importance to access epidemiological aspects of CL in the region and design disease prevention guidelines and effective therapeutic protocols.[8] There have been various identification methods to define Leishmania parasite species including DNA hybridization, isoenzyme analysis, monoclonal antibody, schizodeme analysis, and other molecular methods.[9,10] Genomic DNA and kinetoplastid DNA can be used as templates to perform PCR in molecular ways.[10] In kinetoplastid parasites, Kinetoplast is the organelle which has almost 10,000 copy of small circle DNA strands known as kDNA. Leishmania's kDNA has a weight of about 600 to 800 bp. The mini circle DNA has 120 bp conserved region and a variable 600 bp region. The large number of copy numbers in Leishmania minicircles can be the subject of different studies aiming to detect and identify the species of the parasite.[10]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 186 suspected cases referred to health center of Varzaneh were tested. Among them, 50 cases were confirmed positive by direct microscopy after Giemsa staining.

Slides with smears from patients’ scraped lesions were prepared and used to extract parasite DNA as follow: smears were abrade from the surface of slides after 3 times of washing with Phosphate Saline Buffer (PBS), their DNA content was extracted using a Genet bio genomic DNA extraction kit (made in Korea) and was preserved at −70°C temperature.

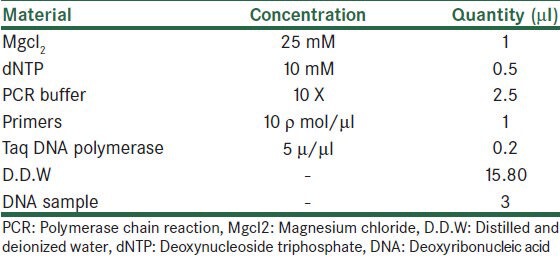

Species characterization of the isolates was done using nested PCR as a very effective and sensitive tool to reproduce mini circle strands. Two pairs of primers were prepared with the same sequences which previously Noyes et al. used to their studies.[11] The primers sequencing were based on the conserved region of template generate 750 bp bond for L. tropica and 560 bp bond for L. major.[11,12] Nested PCR is a two-stage polymerase chain reaction; in the first step, the volume of each reaction was considered 25 μl. The mixture contents are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The mixture contents of PCR reaction

The first step primers are as follows:

CSB2XF: 5’CGAGTAGCAGAAACTCCCGTTCA3’

CSB1XR: 5’ATTTTTCGCGATTTTCGCAGAACG3’

The temperature program of DNA amplification was shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The temperature program of DNA amplification

The PCR product obtained in the first step was used as a template in the second round. The materials used were as same as the previous round with the exception that PCR product was used instead of primary DNA. Primers used in the second step are:

13Z: 5’ACTGGGGGTTGGTGTAAAATAG3’

LiR: 5’TCGCAGAACGCCCCT3’

After final stage of PCR, the products were electrophoresed on agarose gel 1% containing ethidium bromide. Parasite species were detected based on the weight index of their PCR products compared to controls.

RESULTS

After nested PCR, all 50 cases were produced 560 bp bands which indicate the infection with L. major [Figures 1 and 2]. 22 (44%) of patients were females and 28 (56%) of patients were males and their age range was between 7 months and 60 years. 27% of all cases were between 0 and 9 years of age and 23% were between the age of 10 to 19 years, and 50% were older than 19. Anatomic locations of the lesions in their bodies were as follows: 46.6% of wounds were on hands, 33.3% on feet, 16.8% on faces, and 3.3% were located on other parts of the bodies. 40% of patients had a single lesion, 26.6% had two lesions, and 33.4% had 3 or more lesions.

Figure 1.

lane 1: ladder marker, lane 2 L. major (positive control, MRHO/IR/75/ER), lanes 3-10: Leishmania isolates from patients

Figure 2.

lane 1: ladder marker, lane 2 L. tropica (positive control, MHOM/IR/04/Mash10), lanes 3-10: Leishmania isolates from patients

DISCUSSION

All 50 patients were infected with wet type rural form of (CL) with etiologic agent of Leishmania major which the reservoir hosts are usually wild rodents of family Gerbillidae and their principle vectors are Phlebotomus papatasi sand flies.[13] The most common anatomic location of wounds on their bodies were hands, feet, and faces. Due to the fact that sand flies can’t eat the blood over shirt, the biting places were mostly on open parts of the patient bodies. These findings are compatible with other studies in other foci of Zoonotic Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (ZCL) in the country.[14,15] In this study, 40% of patients had single lesion and 60% had two or more. Other studies in which patients with ZCL had more than one lesion on their bodies showed that sand flies bite their hosts more than once due to their physiological characteristics or obstruction of the esophagus because of parasite proliferation on that anatomic place.[13] Two important reasons can be cited for the Varzaneh city that why this area has become an endemic area of CL. First, existence of Haloxylon plant filed in the eastern parts of Imam Sadegh complex which can be a good place for wild rodents to colonies; second, sewer of waste waters are open while passing through houses and the wild rodents burrow around the area. These conditions provide proper places for the proliferation of reservoir rodents and mosquito vectors.

In this study, Nested PCR method was used to identify the species of Leishmania. Due to the large number of kDNA minicircles of Leishmania and high sensitivity and specificity of the Nested PCR method, this technique can be used as an effective tool to identify Leishmania species. Using this method, Maraghi et al. in their study in Khozestan provience showed that 90% of infectious cases were caused by L. major and 10% were caused by L. tropica.[10] In the study of Razmjou et al. in Shiraz Leishmania major was identified through the same method.[16] Pour Esmaiilian also used this method as a robust way to identify Leishmania isolates.[17] The pattern of infection in this study is similar to those of other studies performed in the province.[18,19]

Considering the fact that Isfahan province is one of the most important places for CL in Iran, genetic studies and identification of Leishmania parasites are very important in disease control and combating vectors and reservoirs and improvement of therapy protocols.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pourmohammadi B, Motazedian M, Hatam G, Kalantari M, Habibi P, Sarkari B. Comparison of three methods for diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Iran J Parasitol. 2010;5:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desjeux P. Increase in risk factors for leishmaniasis worldwide. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95:239–43. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(01)90223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herwaldt BL. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 1999;354:1191–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eslami G, Salehi R, Khosravi s, Doudi D. Genetic analysis of clinical isolates of Leishmania major from Isfahan, Iran. J Vector Borne Dis. 2012;49:168–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akhoundi M, Hajjaran H, Baghaei A, Mohebali M. Geographical distribution of leishmania species of human cutaneous leishmaniasis in fars province, Southern Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2013;8:85–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nadim A, Abolhassani M. The epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Isfahan province of Iran. I-The reservoir. II-The human disease. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1968;62:534–42. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(68)90140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nadim A, Mesghali A, Seyedi-Rashti M. Epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran: B. Khorassan Part IV: Distribution of sandflies. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1971;64:865–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohammadi F, Narimani M, Nekoian S, Shirani BL, Mohammadi F, Hosseyni SM, et al. Identification and Isolation of the Cause of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Isfahan Using ITS-PCR Method. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2012;30:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahboodi F, Abolhassani M, Tehrani SR, Azimi M, Asmar H. Differentiation of old and new world Leishmania species at complex and species levels by PCR. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34:756–8. doi: 10.1080/0036554021000026930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maraghi S, Zadeh AS, Sarlak A, Ghasemian M, Vazirianzadeh B. Identification of cutaneous leishmaniasis agents by Nested Polymerase Chain Reaction (Nested-PCR) in Shush City, Khuzestan Province, Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2007;2:13–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noyes H, Reyburn H, Bailey JW, Smith D. A nested-PCRbased schizodeme method for identifying Leishmania kinetoplast minicircle classes directly from clinical samples and its application to the study of the epidemiology of Leishmania tropica in Pakistan. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2877–81. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2877-2881.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khosravi A, Sharifi I, Dortaj E, Ashrafi AA, Mostafavi M. The present status of cutaneous leishmaniasis in a recently emerged focus in South-West of Kerman Province, Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42:182–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azni SM, Rassi Y, Ershdi MY, Mohebali M, Abai M, Mohtarami F, et al. Determination of parasite species of cutaneous leishmaniasis using Nested PCR in Damghan-Iran, during 2008. J Gorgan Univ Med Sci. 2010;13:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rassi Y, Sofizadeh A, Abai M, Oshaghi M, Rafizadeh S, Mohebail M, et al. Molecular detection of Leishmania major in the vectors and reservoir hosts of cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Kalaleh district, Golestan Province, Iran. Iran J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2008;2:21–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Killick-Kendrick R. Phlebotomine vectors of the leishmaniases: A review. Med Vet Entomol. 1990;4:1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1990.tb00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Razmjou S, Hejazy H, Motazedian M, Baghaei M, Emamy M, Kalantary M. A new focus of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Shiraz, Iran. Tran R Soc Trop Med Hyp. 2009;103:727–30. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poursmaelian S, Mirzaei M, Sharifi I, Zarean M. The Prevalence of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the City and Suburb of Mohammadabad, Jiroft district and identification of parasite species by Nested-PCR. 2008. J Kerman Univ Med Sci. 2011;18:218–27. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hejazi SH, Mokhtarian K, Eslami G, Salehi R, Nilforoushzadeh MA, Shirani L, et al. Identification of Leishmania species isolated from paitients with cutaneous leishmaniasis in Mohammad Abad Isfahan using PCR method. Iran J Dermatol. 2007;10:229–35. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashemi N, Hashemi M, Eslami G, Shirani BL, Hejazi SH. Detection of leishmania parasites from cutaneous leishmaniasis patients with negative direct microscopy using NNN and PCR-RFLP. J Isfahan Medical Sch. 2012;29:2613–9. [Google Scholar]