Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD), the most common ciliopathy of childhood, is characterized by congenital hepatic fibrosis and progressive cystic degeneration of kidneys. We aimed to describe congenital hepatic fibrosis in patients with ARPKD, confirmed by detection of mutations in PKHD1.

METHODS

Patients with ARPKD and congenital hepatic fibrosis were evaluated at the National Institutes of Health from 2003 to 2009. We analyzed clinical, molecular, and imaging data from 73 patients (age, 1–56 years; average, 12.7 ± 13.1 years) with kidney and liver involvement (based on clinical, imaging, or biopsy analyses) and mutations in PKHD1.

RESULTS

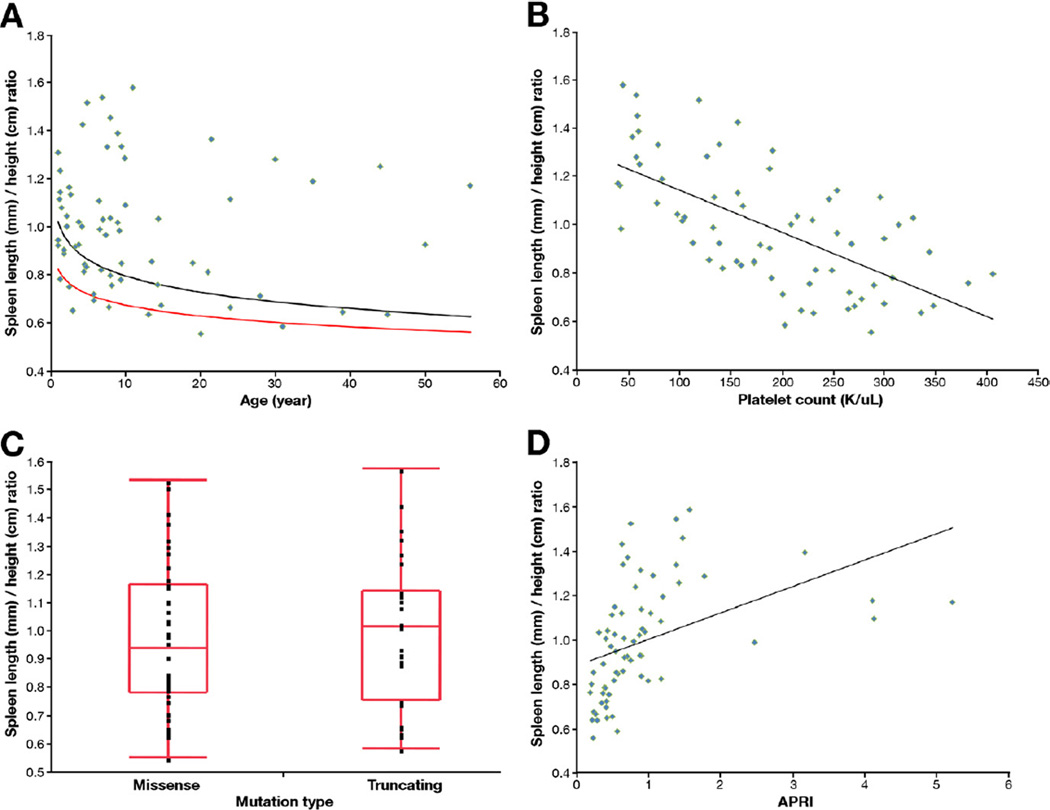

Initial symptoms were liver related in 26% of patients, and others presented with kidney disease. One patient underwent liver and kidney transplantation, and 10 others received kidney transplants. Four presented with cholangitis and one with variceal bleeding. Sixty-nine percent of patients had enlarged left lobes on magnetic resonance imaging, 92% had increased liver echogenicity on ultrasonography, and 65% had splenomegaly. Splenomegaly started early in life; 60% of children younger than 5 years had enlarged spleens. Spleen volume had an inverse correlation with platelet count and prothrombin time but not with serum albumin level. Platelet count was the best predictor of spleen volume (area under the curve of 0.88905), and spleen length corrected for patient’s height correlated inversely with platelet count (R2 = 0.42, P < .0001). Spleen volume did not correlate with renal function or type of PKHD1 mutation. Twenty-two of 31 patients who underwent endoscopy were found to have varices. Five had variceal bleeding, and 2 had portosystemic shunts. Forty-percent had Caroli syndrome, and 30% had an isolated dilated common bile duct.

CONCLUSIONS

Platelet count is the best predictor of the severity of portal hypertension, which has early onset but is underdiagnosed in patients with ARPKD. Seventy percent of patients with ARPKD have biliary abnormalities. Kidney and liver disease are independent, and variability in severity is not explainable by type of PKHD1 mutation;

Keywords: Ductal Plate Malformation, Noncirrhotic Portal Hypertension, Genetics, Hepatorenal Fibrocystic Disease

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) is invariably accompanied by congenital hepatic fibrosis (CHF).1–7 Affected individuals have nonobstructive fusiform dilatations of the renal collecting ducts leading to progressive renal insufficiency5 and ductal plate malformation8–12 of the portobiliary system. The result is CHF, often complicated by portal hypertension (PH).13–15 In addition to CHF, macroscopic dilatations of the intrahepatic bile ducts occur in some patients with ARPKD, a combination termed Caroli syndrome.8,10,16

The causative gene, PKHD1,17,18 encodes fibrocystin/polyductin that localizes to the primary cilium, an organelle that functions as the “sensory antenna” of the cell.19 Proteins defective in other diseases associated with fibrocystic pathology, such as autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, nephronophthisis, Joubert syndrome, and Bardet–Biedl syndrome, also localize to the primary cilium; these disorders, along with ARPKD, are referred to as “ciliopathies.”7,19 CHF also occurs in other ciliopathies, including Bardet–Biedl syndrome, Joubert syndrome, Meckel–Gruber syndrome, Jeune syndrome7 and rare cases of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.20

Most patients with ARPKD present perinatally with enlarged kidneys associated with hypertension, and many newborns die of pulmonary hypoplasia.1 The majority of those who survive the newborn period develop PH later in childhood.13,15,21 Some with mild kidney involvement present with PH in childhood or rarely in adulthood.5,22,23 The clinical phenotype of ARPKD has been largely defined based on perinatally symptomatic kidney-predominant patients.1–3 The literature on CHF is limited to reports of small patient series or individual case reports that lack accurate classification of the accompanying renal involvement; the characteristics of liver disease have not been systematically studied in a cohort of patients with ARPKD. We have recently reported the correlation of kidney function, imaging findings, and PKHD1 mutations in 73 patients with ARPKD and documented the association of renal corticomedullary involvement, often causing perinatal symptoms, with faster progression of kidney disease.5 We now detail the liver-related findings of the same 73 patients with ARPKD through clinical descriptions, biochemical studies, and imaging results. This report documents the independent nature of kidney and liver involvement in ARPKD, characterizes hepatic pathology and PH, defines the extent of biliary abnormalities, correlates functional and imaging findings, and provides a simple means of assessing the severity of the underlying PH.

Patients and Methods

Patients

All patients were enrolled in the intramural National Institutes of Health (NIH) protocol titled “Clinical Investigations into the Kidney and Liver Disease in Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease/Congenital Hepatic Fibrosis and other Ciliopathies” (www.clinicaltrials.gov, trial NCT00068224), which was approved by the National Human Genome Research Institute Institutional Review Board. Patients or their parents gave written informed consent.

This protocol was advertised to pediatric and adult gastroenterologists and nephrologists; patients with a clinical diagnosis of ARPKD made by a nephrologist or a clinical diagnosis of CHF made by a gastroenterologist were qualified to come to the NIH. Between November 2003 and January 2009, 90 potential patients with ARPKD and CHF referred by nephrologists or gastroenterologists were examined at the NIH Clinical Center. Based on clinical evaluations at the NIH, 78 of the 90 patients fulfilled the established clinical diagnostic criteria for ARPKD and CHF, that is, typical kidney and liver involvement on imaging and/or biopsy and autosomal recessive inheritance.3,24 In 73 of these 78 patients, we confirmed the diagnosis molecularly by finding at least one PKHD1 mutation.25 In this report, we present clinical, molecular, functional, and imaging data from these 73 patients with molecularly confirmed ARPKD and CHF.

Evaluations at the NIH Clinical Center included comprehensive biochemical testing, ultrasonography (USG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies, and sequencing of the PKHD1 gene. When possible, parents were evaluated by USG and parental DNA was analyzed. Data collected during the initial NIH visit are presented here. Prospective follow-up of this cohort of patients is under way.

Patient 25 (Supplementary Table 1), who underwent liver-kidney double transplantation, was excluded from all analyses except for splenomegaly decision. One patient (patient 58) with hereditary spherocytosis was excluded from splenomegaly decision. Four patients (patient 58; patient 59, who underwent splenectomy; and patients 48 and 56, who underwent surgical placement of portosystemic shunts) were excluded from further PH-related analyses. One patient with Gilbert syndrome (patient 30) was excluded from total and direct bilirubin analysis.

Biochemical Evaluations

Intestinal fatty acid binding protein (I-FABP) level was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Hycult Biotech Inc, Plymouth Meeting, PA). Renal glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was calculated based on serum cystatin C level, blood urea nitrogen level, creatinine level, and height using pediatric26 and adult27 formulas.

DNA Sequencing and Analysis

Coding exons (2– 67) of PKHD1 and their intronic boundaries were sequenced in 2 directions using a Beckman CEQ 8000 system (Beckman Coulter, Inc, Fullerton, CA) and a contract with Agencourt (Beverly, MA). DNA variant analyses were performed using Sequencher (GeneCodes, Ann Arbor, MI). The pathogenicity of missense variants was evaluated as described25 using segregation analysis, general population frequencies, 3 computational prediction tools (Align GVGD [http://agvgd.iarc.fr/agvgd_input.php], PolyPhen [http://coot.embl.de/PolyPhen], and SNAP [http://cubic.bioc.columbia.edu/services/SNAP]), and the splice variant interpretation software NetGene2 Server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetGene2).

Imaging Studies

Complete abdominal USG evaluations and color Doppler studies were performed on all patients by a single technologist using standard (4-MHz) and high-resolution (HR) (7-MHz) USG probes (AVI Sequoia Inc, Mountain View, CA). We calculated the spleen length/height (SL/H) ratio by dividing spleen length (mm) on USG by the patient’s height (cm). For controls, we combined normative data on 819 children from 2 references.28,29 Patients with SL/H ratios greater than the upper limit of normal defined in these 2 references28,29 were classified as having splenomegaly (Figure 5A). Dilatation of the common bile duct (CBD) was based on published normal values of <3.3 mm (1.27 ± 0.67 mm), obtained by performing USG on 173 children.30 Adults with a CBD diameter less than 5 mm on USG were considered to have a dilated CBD. MRI, including magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), was performed on patients who were old enough to tolerate the study without sedation or who agreed to sedation. MRI was performed using a 1.5- or 3-Tesla machine (Philips Medical Systems, NA, Bothell, WA; General Electric Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) without intravenous contrast media. All USG, MRI, and MRCP images were interpreted by a single radiologist. Liver echogenicity was judged to be normal or mildly, moderately, or severely increased based on the score card presented (Supplementary Figure 1). Liver and spleen volumes were calculated from MRI31,32 at the NIH Image Processing Center.

Figure 5.

(A) SL/H ratio plotted against age. The black line indicates the upper limit of normal range, and the red line is the mean in healthy individuals. Patients whose SL/H ratio was greater than the upper limit of normal were classified as having splenomegaly. (B) SL/H ratio correlated inversely with platelet count (R2 = 0.42, P < .0001). (C) SL/H ratios of patients with missense mutations and with truncating mutations were similar (P = .73). (D) SL/H ratio correlated with APRI (R2 = 0.19, P = .0002).

Statistics

Descriptive statistics for each variable were calculated for the cohort as a whole and separately for the “splenomegaly” and “no splenomegaly” groups, which were determined by SL/H. Values are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical tests used to compare 2 groups included t test for difference in means of continuous variables and Fisher exact test and Pearson χ2 test for difference in counts and frequency. Logistic regression with stepwise variable selection was used to measure the predicting ability of the independent variables (platelets and aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index [APRI], a previously validated noninvasive predictor of cirrhosis) on the probability of the occurrence of “splenomegaly” or “no splenomegaly.” For the purpose of this study, P ≤ .05 is considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.1.3; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and JMP (version 8.0; SAS Institute Inc).

All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The patients (Table 1) included 29 male and 44 female patients aged 1 to 56 years (12.7 ± 13.1 years). One family (family 10; Supplementary Table 1) contributed 4 siblings, 6 families contributed 2 siblings each, and one family (family 40) contributed an aunt and niece pair, leaving 63 independent families. There were 25 young children (younger than 5 years), 31 older children/adolescents (5–18 years), and 17 adults (older than 18 years) (Table 1). The age and sex of the patients in each group are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Patient Demographics and Main Clinical and Molecular Findings

| All patients | Younger than 5 y | 5–18 y | Older than 18 y | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 73 | 25 | 31 | 17 |

| Age at NIH visit (y) | 12.7 ± 13.1 | 2.7 ± 1.4 | 9.6 ± 2.8 | 33.3 ± 11.3 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 29 (40) | 11 (44) | 13 (42) | 5 (29) |

| Female | 44 (60) | 14 (56) | 18 (58) | 12 (71) |

| PKHD1 mutations | ||||

| Missense | 45 (62) | 16 (64) | 21 (68) | 8 (47) |

| Truncating | 28 (38) | 9 (36) | 10 (32) | 9 (53) |

| Liver echogenicity | ||||

| Normal | 6 (8) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 5 (29) |

| Mildly increased | 15 (21) | 4 (16) | 8 (26) | 3 (17) |

| Moderately increased | 37 (51) | 15 (60) | 17 (57) | 5 (29) |

| Severely increased | 14 (20) | 5 (20) | 5 (17) | 4 (25) |

| Liver volume (mL) | 1368 ± 690 | 624 ± 103 | 1203 ± 419 | 2110 ± 609 |

| Spleen volume (mL) | 548 ± 491 | 162 ± 47 | 514 ± 340 | 887 ± 686 |

| Splenomegalya | 47 (65) | 15 (60) | 20 (65) | 12 (71) |

| Varicesb | 22 (71) | 5 (63) | 10 (83) | 7 (64) |

| Platelet count (1,000/µL) | 189 ± 95 | 211 ± 76 | 187 ± 111 | 159 ± 86 |

| Caroli syndrome | 51 (71) | 18 (72) | 21 (70) | 12 (71) |

| Elongated gallbladder | 14 (20) | 4 (16) | 6 (21) | 4 (25) |

| Cholangitis | 4 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 3 (18) |

| Portosplenic shunt | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (6) |

| Liver transplantation | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Kidney transplantation | 11 (15) | 2 (8) | 3 (10) | 6 (35) |

| Kidney USG | ||||

| Medullary only | 23 (37) | 5 (22) | 13 (46) | 5 (45) |

| Corticomedullary | 39 (63) | 18 (78) | 15 (54) | 6 (55) |

| Kidney function/GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2)c | 77 ± 37 | 66 ± 28 | 85 ± 35 | 79 ± 51 |

NOTE. Values are reported as number (percentage) or mean ± SD.

Excluding the patient with hereditary spherocytosis.

Thirty-one patients underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

Only patients with native kidneys were included.

Molecular Genetic Findings

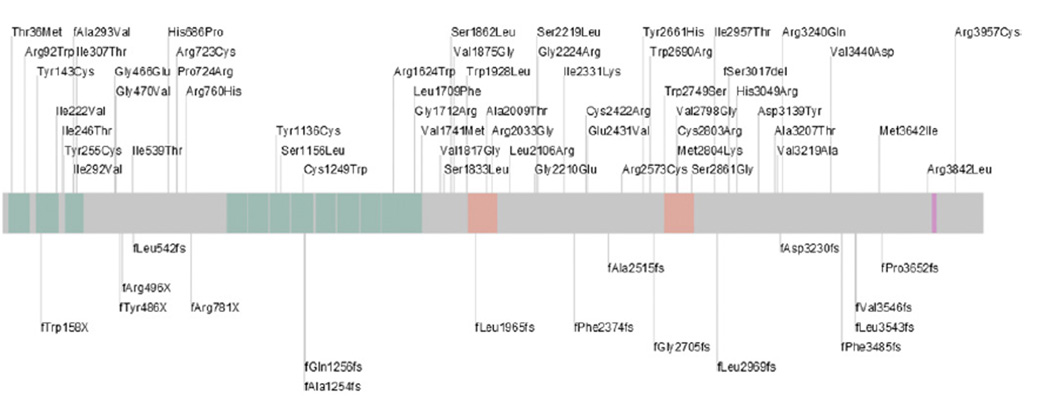

We identified 2 PKHD1 mutations in 43 families and one heterozygous mutation in 20 families (Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 1); these molecular findings are reported elsewhere in detail.25 Twenty-eight patients (25 families) had either one protein-truncating mutation or a truncating mutation in combination with a missense variant. Forty-five patients (38 families) had nontruncating missense mutations (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of fibrocystin/polyductin, the protein encoded by the PKHD1 gene, with positions of the mutations identified in our cohort indicated. Missense mutations are listed above and frameshifting mutations are listed below the bar. Domains of the protein are colorcoded as follows: pink, transmembrane; orange, TMEM2 homology; green, TIG/TIG-like (immunoglobulin-like fold shared by plexins and transcription factors).

Renal Findings

Eleven patients received a kidney transplant, including one kidney-liver transplant (Supplementary Table 1); renal functional and imaging data are reported elsewhere in detail.5 Renal USG of the 62 patients with native kidneys revealed abnormalities involving both renal cortex and medulla in 39 patients (63%), the entire medulla only in 8 (13%), and parts of the medulla only in 15 (24%).5 Thirty-one patients (43%) displayed perinatal symptoms and 42 (57%) first became symptomatic (kidney or liver related) between 1 month and 43 years of age (7.0 ± 11.7 years; median, 2.9 years).5 Diffuse renal pathology with involvement of both the renal medulla and cortex on USG was associated with perinatal presentation and faster progression of kidney disease, whereas patients with ARPKD who had medullary-only renal disease were less likely to become symptomatic perinatally and had slower progression of kidney disease.5

History of Hepatic Disease

The presenting symptom was liver related in 26% of patients (19 of 73); the remaining patients presented with kidney disease.5 Splenomegaly (9 patients), detected incidentally during a routine examination in most cases, was the most common liver-related presenting finding, followed by cholangitis (4 patients), thrombocytopenia (3 patients), liver cysts (2 patients), and acute esophageal variceal bleeding (1 patient). None of the patients had itching, jaundice, edema, or ascites; some patients had chronically decreased stamina. Many patients reported intermittent, diffuse, quite severe abdominal pain that required them to recline but resolved after resting for a short period. There was no consistent trigger or pattern to this abdominal pain, during which the patients were otherwise healthy without nausea, diarrhea, or fever.

One patient (patient 25; Supplementary Table 1) received a liver-kidney allograft at the age of 11 years. A total of 4 patients (patients 30, 40.2, 55, and 61.1; Supplementary Table 1) had cholangitis; the first 3 had recurrent episodes. Patient 40.2 had the first episode of cholangitis after undergoing an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. In patient 55, recurrent cholangitis resolved after surgical removal of a benign hepatic mass impinging on the CBD.

An endoscopic gastroduodenoscopy was performed in 31 of 73 patients; 22 had esophageal varices and 5 (patients 47, 54, 56, 61.2, and 63; Supplementary Table 1) had bleeding from esophageal varices at ages 5, 6, 32, 46, and 50 years. Two patients (patients 48 and 56) underwent surgical placement of portosystemic shunts. Patient 56 first presented with esophageal variceal bleeding at the age of 6 years and underwent surgery for placement of a portosystemic shunt at the age of 11 years. Patient 48 did not have bleeding but had a shunt placed at the age of 11 years because of worsening esophageal varices.

Findings on Abdominal Imaging

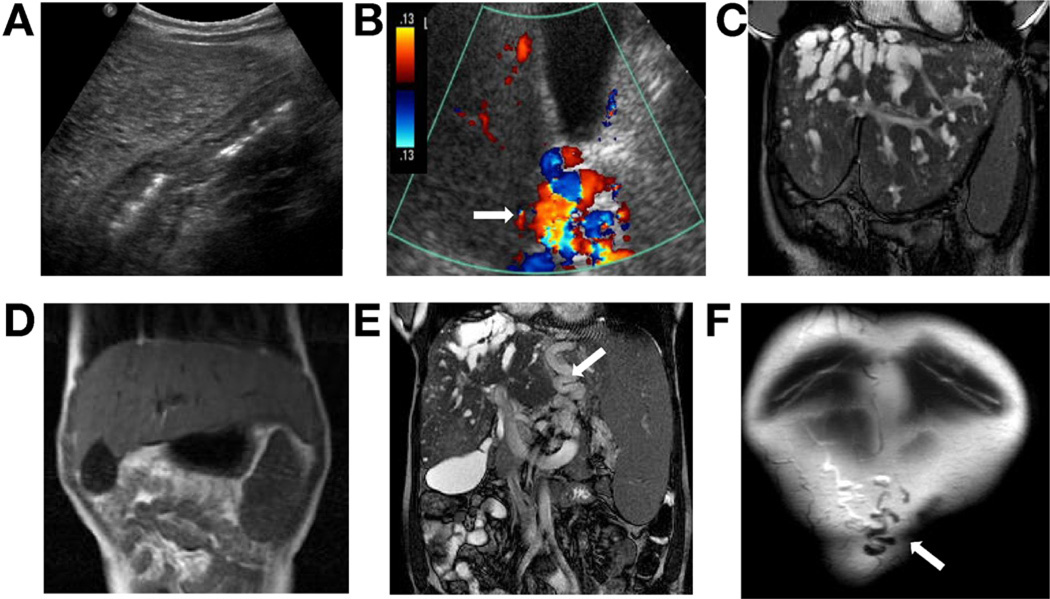

Liver echogenicity on USG was increased in 66 patients (92%); mildly in 15, moderately in 37, and severely in 14 (Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure 1). In 6 patients, color Doppler USG revealed multiple vessels at the porta hepatis resembling cavernous transformation but with a patent lumen (Figure 2B). Otherwise, findings on color Doppler USG were normal in all patients with normal direction of flow toward the liver.

Figure 2.

Findings on abdominal imaging in patients with ARPKD and CHF. (A) USG showing severely increased echogenicity of the liver. (B) Color Doppler USG showing multiple vessels at the porta hepatis with a patent portal vein (arrow) resembling the cavernomatous transformation. (C) MRI showing enlarged left lobe and multiple intrahepatic biliary cysts as well as splenomegaly. (D) MRI showing enlarged left lobe of the liver extending to the left subdiaphragmatic area. (E)MRI showing large collaterals (arrow) between the spleen and the liver, in addition to splenomegaly and multiple small liver cysts. (F) Anterior coronal MRI section showing patent umbilical vein (arrow).

Fifty-one patients underwent MRI and MRCP; 9 were younger than 5 years, 27 were 5 to 18 years, and 15 were adults (Supplementary Table 1). MRI revealed an abnormally shaped liver with a disproportionately enlarged left lobe in 35 of 51 patients (69%) (Figure 2C and D and Figure 3B–D), supporting the physical finding of a palpable left lobe under the xiphoid. In 53% of patients, the liver extended all the way to the left subdiaphragmatic area surrounding the spleen (Figure 2D).

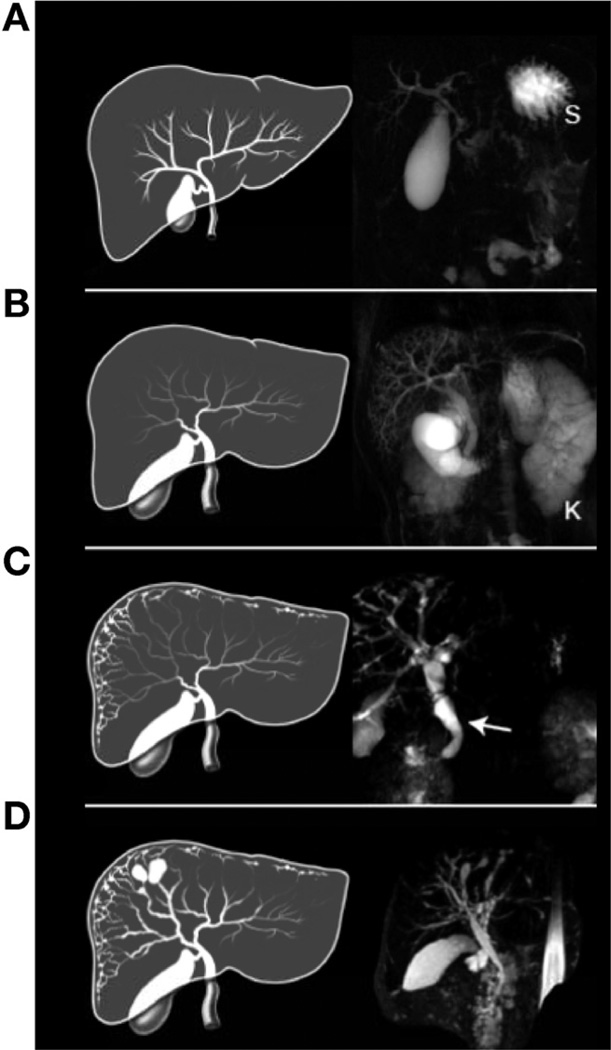

Figure 3.

Artist’s rendering and MRCP images showing the spectrum of biliary abnormalities in ARPKD. (A) Drawing of a normal liver. MRCP is normal except for an enlarged gallbladder. S, stomach. (B) Enlarged extrahepatic CBD and gallbladder. MRCP also shows dilated intrahepatic peripheral ducts. The kidney (K) is enlarged due to diffuse microcystic disease. (C) Fusiform and small cystic dilatations of peripheral and central intrahepatic bile ducts as well as fusiform dilatation of the extrahepatic CBD (arrow) and large gallbladder. (D) Fusiform and macrocystic intrahepatic and extrahepatic dilatations and enlarged gallbladder. All patient livers were abnormally shaped with a disproportionately large left lobe as indicated in the artist’s rendering (B–D).

Liver volume, calculated in 51 patients based on MRI, was above that of age- and weight-adjusted healthy subjects33,34 in 21 patients (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). There was no correlation between liver volume and albumin level, direct bilirubin level, spleen volume, or kidney volume (not shown).

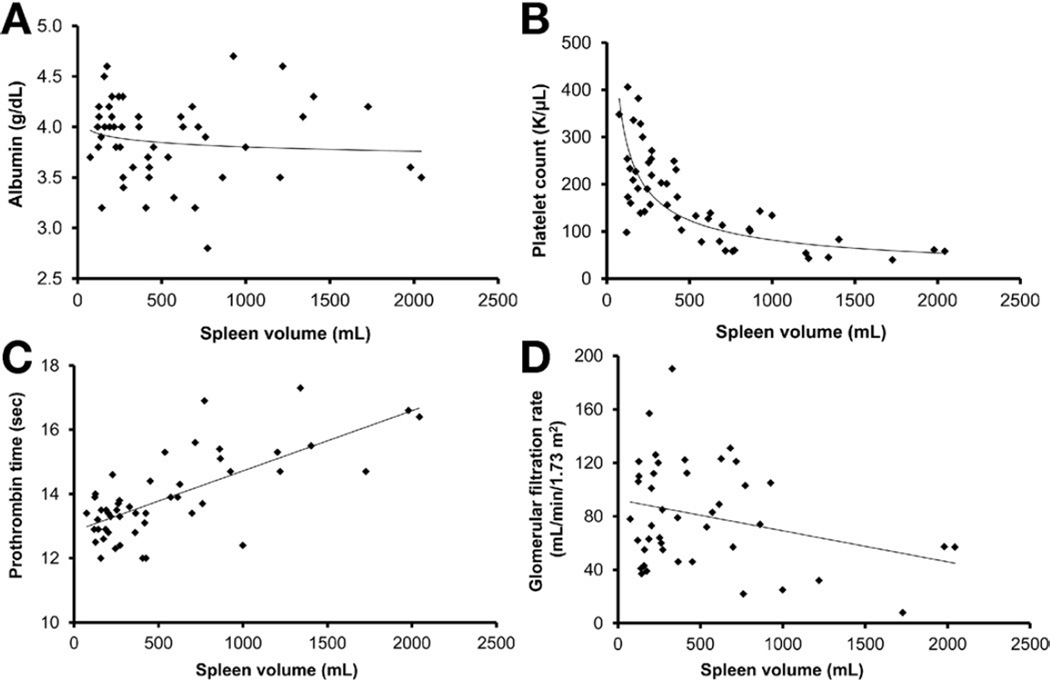

Based on the SL/H ratio, 47 of 72 patients (65%) had splenomegaly28,29,35–37 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Spleen volume did not correlate with bilirubin (not shown) or serum albumin level (y = 4.2515x−0.016, R2 = 0.0164, P = .6386) (Figure 4A). Platelet count correlated negatively with spleen volume (y = 4903x−0.593, R2 = 0.6487, P < .0001) (Figure 4B). Spleen length corrected for height provided the same correlation with platelet count as spleen volume (P < .0001).

Figure 4.

Serum albumin level and renal glomerular function showed no correlation with severity of PH, whereas PT and platelet count showed significant correlation with PH. (A) Serum albumin level did not decrease with worsening PH assessed by spleen volume (y = 4.2515x−0.016, R2 = 0.0164, P = .6386). (B) Platelet count displayed a negative correlation with spleen volume (y = 4903x−0.593, R2 = 0.6487, P < .0001). (C) PT increased with worsening PH measured by spleen volume (y = 0.0019x + 12.842, R2 = 0.51, P < .0001). (D) Renal GFR did not show a good correlation with severity of PH based on spleen volume, although there was a trend (y = 14.205x0.3025, R2 = 0.1021, P = .0225).

Intra-abdominal collateral vessels were detected on MRI in 15 patients (Figure 2E); 9 patients had patent umbilical veins (Figure 2F).

Based on HR-USG and MRCP, 50 of 72 patients (70%) had an abnormality of the biliary system. A total of 40 patients (56%) had a dilated CBD; 21 of these patients had no imaging abnormality of the intrahepatic biliary system (Table 1, Figure 3A–D, and Supplementary Table 1). A total of 29 patients (40%) had Caroli syndrome. All 29 patients with Caroli syndrome had lacy fusiform dilatation of peripheral intrahepatic bile ducts, detectable only on MRCP and HR-USG imaging (Figure 3C and D); in 7 patients, dilatation of peripheral intrahepatic bile ducts was the only abnormality, in 11 patients it was associated with dilated CBD, in 8 patients it was associated with dilatations of central medium-sized bile ducts and dilated CBD, and 3 patients had dilated peripheral and central intrahepatic ducts but a normal CBD (Table 1, Figure 3A–D, and Supplementary Table 1). Forty patients had an enlarged gallbladder.

Hepatic Enzymes and Synthetic Function

Liver enzyme levels were normal in the majority of patients and were only mildly elevated when abnormal (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Alkaline phosphatase level was mildly elevated in 3 patients, and γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT) level was elevated in 10 patients (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2.

Comparison of Laboratory Values in Patients With ARPKD/CHF With and Without Splenomegaly in 3 Age Groups

| All patients | Younger than 5 y | 5–18 y | Older than 18 y | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | SM n = 43 |

No SM n = 25 |

P value | Normal values |

SM n = 15 |

No SM n = 10 |

P value | Normal values |

SM n = 18 |

No SM n = 10 |

P value | Normal values |

SM n = 10 |

No SM n = 5 |

P value |

| Age (y) | 12.4 ± 13.3 | 11.2 ± 12.0 | .714 | — | 2.7 ± 1.3 | 2.6 ± 1.5 | .930 | — | 9.1 ± 2.2 | 9.4 ± 3.4 | .748 | — | 32.9 ± 13.0 | 31.8 ± 10.3 | .881 |

| Platelet count (1,000/µL) | 146 ± 79 | 265 ± 69 | <.0001 | 190–400 | 182 ± 72 | 253 ± 62 | .019 | 190–400 | 140 ± 81 | 288 ± 84 | <.0001 | 190–400 | 117 ± 71 | 242 ± 36 | .003 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 28 ± 16 | 28 ± 15 | .827 | 5–30 | 25 ± 9 | 27 ± 7 | .423 | 5–30 | 27 ± 16 | 23 ± 10 | .518 | 6–41 | 34 ± 23 | 41 ± 27 | .556 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 38 ± 17 | 34 ± 11 | .266 | <60 | 44 ± 12 | 43 ± 8 | .809 | <40 | 36 ± 18 | 30 ± 9 | .296 | 4–34 | 34 ± 19 | 26 ± 7 | .397 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 158 ± 65 | 169 ± 67 | .304 | 93–345 | 169 ± 60 | 181 ± 44 | .593 | 42–390 | 182 ± 47 | 205 ± 51 | .233 | 37–116 | 74 ± 25 | 74 ± 34 | .985 |

| GGT (U/L) | 25 ± 23 | 24 ± 29 | .761 | 4–22 | 17 ± 7 | 15 ± 8 | .583 | 4–42 | 20 ± 11 | 14 ± 3 | .118 | 5–80 | 48 ± 23 | 61 ± 53 | .522 |

| PT (s) | 13.6 ± 1.2 | 13.2 ± 0.6 | .018 | 11.6–15.2 | 13.1 ± 0.5 | 13.1 ± 0.7 | .864 | 11.6–15.2 | 14.5 ± 1.3 | 13.3 ± 0.7 | .014 | 11.6–15.2 | 14.1 ± 1.8 | 13.3 ± 0.6 | .354 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.4 | .641 | 2.9–4.7 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 4 ± 0.4 | .550 | 2.9–4.7 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | .320 | 3.7–4.7 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 1.000 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 6.6 ± 0.5 | 6.7 ± 0.5 | .504 | 6.4–8.2 | 6.4 ± 0.6 | 6.5 ± 0.4 | .874 | 6.4–8.2 | 6.7 ± 0.4 | 6.8 ± 0.4 | .548 | 6.4–8.2 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 6.8 ± 0.7 | .493 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | .196 | 0.0–0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | .524 | 0.0–0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | .863 | 0.0–0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | .061 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | .150 | 0.1–1.0 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | .062 | 0.1–1.0 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | .676 | 0.1–1.0 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | .125 |

| α-Fetoprotein (ng/mL) | 3.8 ± 3.9 | 4.2 ± 4.1 | .520 | 0.6–6.6a | 6 ± 5.2 | 7.2 ± 5.5 | .609 | 0.6–6.6 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 2.5 ± 1.1 | .068 | 0.6–6.6 | 3.2 ± 3.0 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | .519 |

| Ammonia (µmol/L) | 39 ± 22 | 32 ± 17 | .078 | 11–35 | 49 ± 21 | 44 ± 26 | .701 | 11–35 | 41 ± 18 | 31 ± 7 | .163 | 11–35 | 42 ± 36 | 20 ± 8 | .207 |

| I-FABP | 250 ± 390 | 74 ± 124 | .028 | — | 265 ± 459 | 75 ± 116 | .301 | — | 282 ± 401 | 79 ± 145 | .185 | — | 556 ± 478 | 20 ± 0.0 | .334 |

| APRI | 0.9 ± 0.9 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | .001 | — | 1 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | .222 | — | 1.3 ± 1.0 | 0.4 ± 0.3 | .015 | — | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | .092 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | .064 | 0.16–0.42 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | .931 | 0.29–0.81 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | .129 | 0.56–1.19 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1 ± 0.3 | .190 |

| GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 67 ± 31 | 90 ± 41 | .0177 | 65–120 | 62 ± 25 | 72 ± 32 | .433 | 74–120 | 78 ± 33 | 97 ± 39 | .154 | 100–136 | 58 ± 37 | 115 ± 56 | .068 |

SM, splenomegaly.

α-Fetoprotein values are higher within the first year of life.

Seventeen patients had low serum albumin values, ranging from 2.8 to 3.6 (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Total bilirubin level was mildly elevated in 7 patients, ranging from 1.1 to 3.2 mg/dL. Prothrombin time (PT) was mildly prolonged in 11 patients, ranging from 15.1 to 17.3 seconds. PT did not correlate with direct bilirubin or albumin level but did correlate with spleen volume (y = 0.0019x + 12.842, R2 = 0.51, P < .0001) (Figure 4C). α-Fetoprotein levels were normal in all patients.

Portal Hypertension

Based on the SL/H ratio, 47 of 72 patients (excluding the patient with hereditary spherocytosis) had splenomegaly. Four patients with splenomegaly (patient 58; patient 59, who underwent splenectomy; and patients 48 and 56, who underwent surgical placement of portosystemic shunts) were excluded from further PH-related analyses. The remaining 43 patients with splenomegaly were compared with the 25 patients without splenomegaly (Table 2); platelet count, PT, I-FABP, APRI, and GFR differed significantly. The mean age of the splenomegaly group (12.4 ± 13.3 years) was not statistically different from that of those without splenomegaly (11.2 ± 12.0 years) (P = .714). Consistently, the frequency of splenomegaly in patients younger than 5 years (60%) was similar to that in older children (65%) and adults (71%). The mean platelet count of patients with splenomegaly (146,000 ± 79,000/µL) was significantly lower than that of patients without splenomegaly (265,000 ± 69,000/µL) (P ≤ .0001). Platelet counts decreased as patients got older: 211,000 ± 76,000/µL in young children, 187,000 ± 111,000/µL in older children, and 159,000 ± 86,000/µL in adults (Table 1). The mean PT of patients with splenomegaly (13.6 ± 1.2 seconds) was significantly higher than that of patients without splenomegaly (13.2 ± 0.6 seconds) (P = .018). When patients with and without splenomegaly were compared within 3 age groups, platelet count remained significantly different for all 3 age groups (Table 2). The correlation was similar for the 3 age groups analyzed (younger than 5 years, 5–18 years, older than 18 years) but with more scatter in the youngest group (data not shown). Logistic regression analysis revealed platelet count as the single best predictor of spleen volume (P < .001, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.88905).

Patients with splenomegaly were more likely to have moderate to severely increased liver echogenicity (83%) in comparison to those without splenomegaly (48%) (P = .0027). As expected, all 15 patients with intra-abdominal collateral vessels on imaging were in the splenomegaly group. Similarly, 8 of the 10 patients with patent umbilical veins were in the splenomegaly group. In the splenomegaly group, 22 of the 27 patients who underwent endoscopy had esophageal varices, compared with 2 of the 4 without splenomegaly. All 4 patients with a history of esophageal variceal bleeding were in the splenomegaly group. Five of the 6 patients with multiple vessels at the porta hepatis were in the splenomegaly group.

There was no significant difference in liver enzyme levels between patients with or without splenomegaly. Similarly, the frequency and extent of biliary abnormalities were comparable between the 2 groups.

PKHD1 Mutation Severity and Liver Disease

To explore genotype-phenotype correlations, we compared patients with protein-truncating mutations to patients with nontruncating mutations. The mean spleen volume of patients with protein-truncating mutations (676 ± 581 mL) was not significantly different from that of patients with nontruncating mutations (465 ± 410 mL) (P = .35). The SL/H ratio of patients with missense mutations and those with truncating mutations was not statistically different. Similarly, the frequency of truncating and nontruncating mutations was not significantly different when patients with and without biliary abnormalities were compared (P = .7912). The distribution of protein-truncating and nontruncating mutations was similar in patients with and without splenomegaly (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

Relationship of Kidney and Liver Disease

To determine if the severities of kidney and liver disease were correlated, we compared the spleen volumes of patients with severe (Supplementary Table 1; corticomedullary) and mild (Supplementary Table 1; medullary) kidney involvement. The mean spleen volume of patients with corticomedullary involvement (535 ± 589 mL) was similar to that of patients with only medullary kidney disease (494 ± 257 mL) (P = .79). Kidney function, measured as GFR (Supplementary Table 1), did not correlate with spleen volume (R2 = 0.14, P = .0622) (Figure 4D). The GFR of patients with splenomegaly was lower than that of patients without splenomegaly (Table 2), most likely due to the progressive nature of both kidney and liver disease. Similarly, the extent of cystic renal disease on USG was similar between groups.

Discussion

Comprehensive prospective evaluation of liver and kidney disease in 73 children and adults with PKHD1 mutations has allowed for a new and more complete understanding of CHF in ARPKD. For example, an inverse relationship was previously suggested between the severity of kidney and liver disease in ARPKD,24 although not consistently.3,38 Our results show no correlation between kidney function and PH in ARPKD (Figure 4D). In fact, in our cohort, patients with combinations of severe liver/severe kidney, mild liver/mild kidney, mild liver/severe kidney, and severe liver/mild kidney were represented with approximate frequencies of 40%, 20%, 20%, and 20%, respectively (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 2A–F). Furthermore, the frequencies of PH and biliary abnormalities in patients with mild (medullary-only) renal disease were similar to those of patients with severe (corticomedullary) renal disease. Our patients with mild kidney disease, who were asymptomatic perinatally, first came to medical attention in late childhood or adulthood, when their PH was advanced enough to reveal splenomegaly or thrombocytopenia. By comparison, many of the patients with perinatally presenting severe kidney disease developed severe liver disease if they survived the neonatal period5 (Supplementary Table 1).

PH in ARPKD was not systematically studied in the past. We used the SL/H ratio as well as spleen volume to evaluate the severity of PH in ARPKD and to understand its characteristics. Our data indicate that the pathophysiology of PH in ARPKD is already established early in life; 60% of patients younger than 5 years of age had splenomegaly, which was not significantly different from that in older children and adults. Interestingly, the number of patients who came to medical attention due to splenomegaly (9) and thrombocytopenia (3) was low, suggesting that PH in ARPKD is underdiagnosed.

At spleen volumes greater than 500 mL/1.73 m2 (approximately twice the upper limit of normal for adults), platelet and white blood cell counts fell below the normal range (Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 4B). The correlation was not perfect, however, because platelet counts less than 100,000/L occurred with spleen volumes anywhere between 500 and 2000 mL/1.73 m2 (Figure 4B). Our data indicate that platelet count is the best predictor of spleen volume as a measure of the severity of PH in ARPKD (area under the curve of 0.88905). This is based on the excellent inverse correlation of the SL/H ratio with platelet count (R2 = 0.42, P < .0001) as well as the very significant negative correlation of platelet count with spleen volume (y = 4903x−0.593, R2 = 0.6487, P < .0001) (Figure 4B). Platelet counts of adults (159,000 ± 86,000/µL) and older children (187,000 ± 111,000/µL) were lower than that of younger children (211,000 ± 76,000/µL), suggesting that PH in ARPKD progresses as patients get older (Table 1).

PT correlated positively with spleen volume (Figure 4C). This suggested that the underlying mechanism for the elevation of PT was related to PH, as reported in other diseases associated with noncirrhotic PH.39 A further confirmation that spleen volume served as a measure of PH was the finding of higher levels of I-FABP in the patients with splenomegaly. I-FABP is a marker of enterocyte death and has been previously associated with PH.40 The ability of APRI to discriminate patients with and without splenomegaly is of interest, because APRI was not previously known to indicate advanced disease in noncirrhotic PH. Given that the aspartate aminotransferase values were similar in patients with and without splenomegaly, platelet counts account for the difference in APRI scores.

Other new information included the finding of a specific type of Caroli syndrome in the form of lacy fusiform dilatations of peripheral intrahepatic bile ducts visible only on MRCP and HR-USG (Figure 3C and D) in 40% of the patients. MRCP also revealed dilated extrahepatic CBDs and enlarged gallbladders in 40% (Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 3C and D); indeed, an abnormal extrahepatic biliary system, recently reported in 4 patients with ARPKD,41 is a common but underrecognized feature in ARPKD. Interestingly, of the 4 patients who had cholangitis, one had a dilated CBD in association with normal intrahepatic ducts; the other 3 had no biliary abnormalities detectable on HR-USG or MRCP. Of the 10 patients with elevated GGT levels, 2 had a normal biliary system, one had a dilated CBD, and 7 had Caroli syndrome (Supplementary Table 1). Conversely, of the 11 patients with both peripheral and central intrahepatic cysts, only 2 had mildly elevated GGT levels.

There was considerable variability in the severity of liver and kidney disease even among siblings (Supplementary Table 1). The mild nature of PH was consistent among the 4 affected siblings in family 10 (patients 10.1, 10.2, 10.3, and 10.4), whereas the severity of their renal disease was highly variable; the youngest sibling required renal transplantation at 18 years of age, whereas the oldest brother had only mild kidney dysfunction at 28 years of age. In family 60, the severity of liver involvement was variable but the kidney disease was similar; patient 61.2 had severe PH, differing from her brother (61.1), who had mild PH but also had cholangitis. This variability is probably not explained by the sex of the patient because in family 51, the 9-year-old sister (51.2) had much milder PH in comparison to her 7-year-old brother (51.1). Moreover, the variability in kidney and liver phenotype could not be explained by the location or type (truncating or missense) of PKHD1 mutations (Figure 1).

Our findings agree with those of previous investigations in many respects. All of our patients had evidence of CHF, with increased liver echogenicity or splenomegaly. Major complications of PH were esophageal varix formation and decreased platelet and white blood cell counts due to hypersplenism. Hepatic synthetic function was relatively preserved13; direct bilirubin and albumin levels were generally normal.

We conclude that the severity of kidney disease and severity of liver disease in ARPKD are independent from each other. Intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary abnormalities are common; alkaline phosphatase and GGT levels remain normal in most patients (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1). PH in ARPKD starts early in life and progresses over time. Platelet count is a good surrogate marker for severity of PH, which is underdiagnosed in ARPKD. Given the fact that liver enzyme levels are only minimally elevated, platelet count and abdominal USG are more informative in diagnosing the liver disease in ARPKD. Starting at the time of initial diagnosis, all patients with ARPKD should be evaluated by a gastroenterologist and undergo abdominal USG evaluations annually for increased liver echogenicity, biliary abnormalities, and splenomegaly as well as blood work with special attention to platelet counts. Longitudinal follow-up of this cohort will likely contribute to our understanding of the factors associated with progression of PH in ARPKD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the ARPKD/CHF Alliance for their extensive support and the patients and their families who generously participated in this investigation.

Funding

Supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and NIH Clinical Center.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- APRI

aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index

- ARPKD

autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease

- CBD

common bile duct

- CHF

congenital hepatic fibrosis

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- GGT

γ-glutamyltransferase

- HR

high-resolution

- I-FABP

intestinal fatty acid binding protein

- MRCP

magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- PH

portal hypertension

- PT

prothrombin time

- SL/H

spleen length/height

- USG

ultrasonography

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.056.

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

References

- 1.Zerres K, Rudnik-Schoneborn S, Deget F, et al. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease in 115 children: clinical presentation, course and influence of gender. Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Padiatrische, Nephrologie. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:437–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capisonda R, Phan V, Traubuci J, et al. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: outcomes from a single-center experience. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18:119–126. doi: 10.1007/s00467-002-1021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guay-Woodford LM, Desmond RA. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: the clinical experience in North America. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1072–1080. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunay-Aygun M, Heller T, Gahl WA. GeneReviews at GeneTests: Medical Genetics Information Resource. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2008. Congenital hepatic fibrosis overview. [database online] http://www.genetests.org. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gunay-Aygun M, Font-Montgomery E, Lukose L, et al. Correlation of kidney function, volume and imaging findings, and PKHD1 mutations in 73 patients with autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:972–984. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07141009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunay-Aygun M, Avner ED, et al. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease and congenital hepatic fibrosis: summary statement of a first National Institutes of Health/Office of Rare Diseases conference. J Pediatr. 2006;149:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gunay-Aygun M. Liver and kidney disease in ciliopathies. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2009;151C:296–306. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorgensen MJ. The ductal plate malformation. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand Suppl. 1977:1–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jorgensen M. A stereological study of intrahepatic bile ducts. 4. Congenital hepatic fibrosis. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A. 1974;82:21–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desmet VJ. Congenital diseases of intrahepatic bile ducts: variations on the theme "ductal plate malformation". Hepatology. 1992;16:1069–1083. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desmet VJ. What is congenital hepatic fibrosis? Histopathology. 1992;20:465–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1992.tb01031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desmet VJ. Ludwig symposium on biliary disorders—part I. Pathogenesis of ductal plate abnormalities. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:80–89. doi: 10.4065/73.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerr DN, Okonkwo S, Choa RG. Congenital hepatic fibrosis: the long-term prognosis. Gut. 1978;19:514–520. doi: 10.1136/gut.19.6.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarez F, Bernard O, Brunelle F, et al. Congenital hepatic fibrosis in children. J Pediatr. 1981;99:370–375. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(81)80320-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Summerfield JA, Nagafuchi Y, Sherlock S, et al. Hepatobiliary fibropolycystic disease: a clinical and histological review of 51 patients. J Hepatol. 1986;2:141–156. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(86)80073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caroli J. Diseases of the intrahepatic biliary tree. Clin Gastroenterol. 1973;2:147–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward CJ, Hogan MC, Rossetti S, et al. The gene mutated in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease encodes a large, receptor-like protein. Nat Genet. 2002;30:259–269. doi: 10.1038/ng833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Onuchic LF, Furu L, Nagasawa Y, et al. PKHD1, the polycystic kidney and hepatic disease 1 gene, encodes a novel large protein containing multiple immunoglobulin-like plexin-transcription-factor domains and parallel beta-helix 1 repeats. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:1305–1317. doi: 10.1086/340448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma N, Berbari NF, Yoder BK. Ciliary dysfunction in developmental abnormalities and diseases. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;85:371–427. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00813-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Brien K, Font-Montgomery E, Lukose L, et al. Congenital hepatic fibrosis and portal hypertension in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:83–89. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318228330c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roy S, Dillon MJ, Trompeter RS, et al. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: long-term outcome of neonatal survivors. Pediatr Nephrol. 1997;11:302–306. doi: 10.1007/s004670050281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fonck C, Chauveau D, Gagnadoux MF, et al. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease in adulthood. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:1648–1652. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.8.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adeva M, El-Youssef M, Rossetti S, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization defines a broadened spectrum of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85:1–21. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000200165.90373.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zerres K, Volpel MC, Weiss H. Cystic kidneys. Genetics, pathologic anatomy, clinical picture, and prenatal diagnosis. Hum Genet. 1984;68:104–135. doi: 10.1007/BF00279301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gunay-Aygun M, Tuchman M, Font-Montgomery E, et al. PKHD1 sequence variations in 78 children and adults with autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease and congenital hepatic fibrosis. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99:160–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz GJ, Munoz A, Schneider MF, et al. New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:629–637. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grubb A, Bjork J, Lindstrom V, et al. A cystatin C-based formula without anthropometric variables estimates glomerular filtration rate better than creatinine clearance using the Cockcroft-Gault formula. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2005;65:153–162. doi: 10.1080/00365510510013596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Megremis SD, Vlachonikolis IG, Tsilimigaki AM. Spleen length in childhood with US: normal values based on age, sex, and somatometric parameters. Radiology. 2004;231:129–134. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2311020963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Konus OL, Ozdemir A, Akkaya A, et al. Normal liver, spleen, and kidney dimensions in neonates, infants, and children: evaluation with sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1693–1698. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.6.9843315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernanz-Schulman M, Ambrosino MM, Freeman PC, et al. Common bile duct in children: sonographic dimensions. Radiology. 1995;195:193–195. doi: 10.1148/radiology.195.1.7892467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grantham JJ, Torres VE, Chapman AB, et al. Volume progression in polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2122–2130. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheong B, Muthupillai R, Rubin MF, et al. Normal values for renal length and volume as measured by magnetic resonance imaging. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:38–45. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00930306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noda T, Todani T, Watanabe Y, et al. Liver volume in children measured by computed tomography. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:250–252. doi: 10.1007/s002470050114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu HC, You H, Lee H, et al. Estimation of standard liver volume for liver transplantation in the Korean population. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:779–783. doi: 10.1002/lt.20188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coppoletta JM, Wolbach MD. Body length and organ weights of infants and children. Am J Pathol. 1933;9:55–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schlesinger AE, Edgar KA, Boxer LA. Volume of the spleen in children as measured on CT scans: normal standards as a function of body weight. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;160:1107–1109. doi: 10.2214/ajr.160.5.8470587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe Y, Todani T, Noda T, et al. Standard splenic volume in children and young adults measured from CT images. Surg Today. 1997;27:726–728. doi: 10.1007/BF02384985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gagnadoux MF, Habib R, Levy M, et al. Cystic renal diseases in children. Adv Nephrol Necker Hosp. 1989;18:33–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bajaj JS, Bhattacharjee J, Sarin SK. Coagulation profile and platelet function in patients with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction and non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:641–646. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sandler NG, Koh C, Roque A, et al. Host response to translocated microbial products predicts outcomes of patients with HBV or HCV infection. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1220–1230. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.063. 1230 e1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goilav B, Norton KI, Satlin LM, et al. Predominant extrahepatic biliary disease in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: a new association. Pediatr Transplant. 2006;10:294–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2005.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.