Key Points

The robustness of the VWF:collagen-binding assay is confirmed in a comprehensive evaluation of VWD collagen-binding defects.

Collagen binding by VWF, GPVI, and α2β1 have major albeit overlapping functions in primary hemostasis.

Abstract

Rare missense mutations in the von Willebrand factor (VWF) A3 domain that disrupt collagen binding have been found in patients with a mild bleeding phenotype. However, the analysis of these aberrant VWF-collagen interactions has been limited. Here, we have developed mouse models of collagen-binding mutants and analyzed the function of the A3 domain using comprehensive in vitro and in vivo approaches. Five loss-of-function (p.S1731T, p.W1745C, p.S1783A, p.H1786D, A3 deletion) and 1 gain-of-function (p.L1757A) variants were generated in the mouse VWF complementary DNA. The results of these various assays were consistent, although the magnitude of the effects were different: the gain-of-function (p.L1757A) variant showed consistent enhanced collagen binding whereas the loss-of-function mutants showed variable degrees of functional deficit. We further analyzed the impact of direct platelet-collagen binding by blocking glycoprotein VI (GPVI) and integrin α2β1 in our ferric chloride murine thrombosis model. The inhibition of GPVI demonstrated a comparable functional defect in thrombosis formation to the VWF−/− mice whereas α2β1 inhibition demonstrated a milder bleeding phenotype. Furthermore, a delayed and markedly reduced thrombogenic response was still evident in VWF−/−, GPVI, and α2β1 blocked animals, suggesting that alternative primary hemostatic mechanisms can partially rescue the bleeding phenotype associated with these defects.

Introduction

von Willebrand factor (VWF) plays an important role in coagulation as a carrier protein for factor VIII (FVIII) and in primary hemostasis with binding of VWF to exposed subendothelial collagens. The most hemostatically important forms of collagen include the fibrillar collagens I and III, and the microfibrillar collagen VI. VWF binds to collagen I and III via the VWF A1 and A3 domains1,2 whereas only the A1 domain binds collagen VI.3 Although the relative hemostatic importance of the A3 and A1 collagen-binding domains is controversial, they likely have a complementary role and blood flow-mediated shear stress is important for the conformation and function of both.4 Once immobilized by collagen, the VWF platelet glycoprotein Ibα (GPIbα)–binding site within the A1 domain is exposed and the high affinity, rapid, and reversible interaction between VWF and GPIbα tethers platelets to the endothelium where they roll until they are immobilized by direct platelet-collagen binding which has slower binding kinetics.5 This is mediated by 2 collagen receptors on platelets, GPVI and the integrin α2β1 (or GPIa/IIa), which lead to irreversible adhesion and activation of platelets.6-8

von Willebrand disease (VWD) is a highly heterogeneous mucocutaneous bleeding disorder marked by either quantitative or qualitative pathologies of VWF.9 The qualitative disorders representing type 2 VWD are further classified into variants that affect VWF-platelet interactions (types 2A, 2B, and 2M VWD) or affect VWF-FVIII binding (2N). The diagnostic algorithm for the evaluation of VWD recommended by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) VWD guidelines includes the measurement of VWF antigen (VWF:Ag), VWF ristocetin cofactor activity (VWF:RCo, a measure of VWF-GpIbα activity), and factor VIII coagulant activity (FVIII:C).10 The evaluation of collagen binding is infrequently incorporated into diagnostic testing and the omission of this assay will miss cases where rare mutations affect only the VWF collagen-binding function (also classified as type 2M VWD).

Several enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)–based VWF collagen-binding assays (VWF:CB) which use type I, type III, or a mixture of the 2 collagens, are commercially available and have been previously evaluated and compared.11 Because the VWF:CB assay is sensitive to the loss of high-molecular-weight multimer (HMWM) VWF in addition to detecting a defect of collagen binding, studies have focused on optimizing this assay to discriminate between deficiencies of VWF (type 1 VWD) from dysfunction (type 2A/B VWD), potentially replacing the need for VWF:RCo or multimer analysis.12,13 On the other hand, an abnormal CB:Ag ratio of <0.7,14 with a normal multimer profile indicates a collagen-binding defect. Collagen-binding mutations are rare and comprehensive analysis of the aberrant VWF-collagen interaction has been limited. To date, 4 point mutations within the VWF A3 domain affecting collagen binding have been described in 12 patients: p.S1731T, p.W1745C, p.S1783A, and p.H1786D.15-17 The phenotypic characteristics of these 12 patients, who were all heterozygous for a collagen-binding mutation, are summarized in Table 1.18,19

Table 1.

Phenotypic characteristics of patients with collagen-binding mutations

| p.S1731T | p.W1745C | p.S1783A | p.H1786D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 6 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Bleeding score* | 0-2† | 4-8 | 5-10 | 8 |

| VWF:Ag, IU/dL | 0.30-0.75 | 0.29-0.52 | 0.68-0.88 | 0.41 |

| VWF:RCo, IU/dL | 0.30-0.64 | 0.27-39 | 0.57-0.66 | 0.44 |

| CB:Ag ratio | 0.4-0.9 | 0.1-0.3 | 0.2-0.4 | 0.5 |

| Multimers | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| References | 16 | 17 | 17 | 15 |

All of the subjects included were heterozygous for the collagen-binding mutation, except 1 of the p.W1745C subjects who was compound heterozygous for a second missense mutation associated with type 1 VWD (p.R760H).

The condensed MCMDM-1 and original MCMDM-1 questionnaires were used.18,19 A score of ≥4 is abnormal.

A bleeding score was only available for 4 of 6 of these subjects.

Given the rarity of collagen-binding mutants and the heterogeneous genetic backgrounds of the described subjects, we reasoned that studies in an inbred mouse model would provide a more controlled strategy to comprehensively evaluate the 4 previously described VWD collagen-binding defects, a collagen-binding gain-of-function mutant (p.L1757A),20 and VWF with an A3 domain deletion. Furthermore, in light of the continuing, albeit attenuated, thrombogenesis documented with the VWF collagen-binding variants, we have also used this mouse model to determine the relative contribution of GPVI and α2β1 to this process.7,21,22

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction and mutagenesis

The full-length murine VWF complementary DNA (cDNA) (mVWF, kindly provided by Dr Peter Lenting, Inserm U770 and Université Paris-Sud, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France) was cloned into the pCIneo plasmid (Promega)23 to produce recombinant mouse VWF protein (r-mVWF) and into the pSC11 plasmid24 (courtesy of Dr Luigi Naldini, San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy) for hydrodynamic delivery.25 Mutagenesis was performed using the Quikchange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) to introduce the gain-of-function mutation (p.L1757A) and loss-of-function mutations (p.S1731T, p.W1745C, p.S1783A, p.H1786D, A3 deletion). All of these wild-type (WT) amino acids are conserved between human and mouse.

Recombinant protein production

HEK293T cells were transiently transfected using the calcium phosphate method and r-mVWF was obtained as previously described.26 mVWF protein concentration (VWF:Ag) was determined by ELISA as previously described.26 All values of both media and lysates were normalized to the level of VWF:Ag expressed in the media (n = 10). Multimers were analyzed by electrophoresis as previously described and HMWM is defined as >10 bands.27

Collagen-binding assay (VWF:CB)

The collagen-binding activity of VWF was measured by ELISA. Ninety-six-well microtiter plates (Thermo Scientific) were coated with either type I or type III collagen derived from human placenta (Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 40 μg/mL in sodium carbonate/bicarbonate buffer (0.035 M NaHCO3, 0.015 M Na2CO3, pH 9.6) at room temperature for 48 hours. Wells were washed with imidazole buffer (0.12 M NaCl, 0.02 M imidazole, 0.005 M citric acid, pH 7.3). After washing and blocking with imidazole buffer, samples were added to the wells and incubated for 2 hours at 37°C. Wells were washed with imidazole buffer 3 times and incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated rabbit anti-human VWF Ab (Dako) diluted 1:220 in imidazole buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. Bound antibody was detected with Color Fast O–phenylenediamine substrate (Sigma-Aldrich) and the absorbance recorded at 492 nm.

Flow chamber experiments

The parallel flow chamber was coated with human placenta collagen type I (500 μg/mL) or III (250 μg/mL) and recombinant mVWF mutants (10 U/mL) were applied after washing and blocking. Whole mouse blood was taken from VWF−/− mice by cardiac puncture and anticoagulated with Argatroban (200 μM). Platelets are labeled with 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbobyanine iodide (DiOC6, 1 μM). The flow chamber was set on a Quorum WaveFX-X1 spinning disk confocal system (Quorum Technologies Inc). Whole mouse blood was drawn through the chamber by a 6-channel syringe pump (New Era Pump Systems Inc) at 2500 s−1. The lanes were sequentially imaged using 491-nm excitation laser and acquired on Hamamatsu EM-CCD camera through 520/35-nm BP filter for 10 minutes. For each channel, z series were acquired at 2-μm steps for an overall distance of 12 μm. Platelet adhesion and aggregation was evaluated as surface coverage based on the confocal sliced images at the height of 2 μm from the collagen surface, and subsequent thrombus formation was analyzed as thrombus volume, which was calculated by summing all sliced images of platelet covering area using Image Pro Plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics).

Hydrodynamic injections into VWF−/− mice

C57Bl/6 WT mice or C57Bl/6 VWF−/− mice,28 10 to 12 weeks of age, were used in all experiments. All mouse experiments were reviewed and approved by the Queen’s University Animal Care Committee. Plasmid DNA (100 μg of pSC11-ET-mVWF) was diluted in a 10% body weight volume of lactated Ringer solution and injected via tail vein of C57Bl/6 VWF−/− in <5 seconds using a 27-gauge needle and 3-mL syringe.29 Blood was collected as previously described.28

Inhibition of platelet GPVI and α2β1

Anti-mouse GPVI antibody (JAQ1; Emfret) and anti-α2β1 antibody (23C11-Fab fragment: LEN/B) were used to inhibit the function of GPVI and α2β1 integrin, respectively. The inhibitory effect of these antibodies was confirmed by flow cytometry and platelet aggregation assay. For flow cytometry, heparinized whole blood was diluted 1:20, and incubated with the appropriate fluorophore-conjugated monoclonal antibodies for 15 minutes at room temperature and analyzed on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson). For platelet aggregation, washed platelets (160 μL with 1.56 × 108 platelets/mL) from normal mice or mice lacking α2β1 (Itga2−/−) were used in the presence of 70 μg/mL human fibrinogen. Platelet aggregation upon fibrillar type I collagen (Nycomed) was analyzed by using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled JAQ1 and LEN/B. Transmission was recorded on a 4-channel aggregometer (Fibrintimer; APACT) for 15 minutes and expressed in arbitrary units, with buffer representing 100% transmission. For the in vivo thrombosis studies, JAQ1 and LEN/B were injected intraperitoneally into VWF−/− mice or VWF−/− mice treated with the hydrodynamic delivery of the WT-mVWF expression plasmid 3 days and an hour, respectively, prior to the intravital experiments.21

Intravital microscopy for the ferric chloride injury model of thrombosis

Intravital microscopy was performed as previously described.30 At the time of these experiments, the plasma VWF levels were between 0.5 and 4.5 U/mL, 10 to 21 days posthydrodynamic injection. Rhodamine 6G (40 μg; Sigma-Aldrich) was injected via the jugular vein to fluorescently label platelets in vivo. Arterioles ranging in size from 30 to 60 μm in the cremaster muscle were selected and injured with 10% ferric chloride-soaked filter paper for 3 minutes. Following injury, a single arteriole in the injured area was observed for 40 minutes. Size of the formed thrombus was measured, as was the time to vessel occlusion by 2 blinded observers. Occlusion times exceeding 40 minutes were recorded as 40 minutes. Thrombus was evaluated with percentage occlusion according to the area of thrombus in the defined area (as shown in Figure 6A). Thrombus covering the whole vessel diameter with residual blood flow was recorded as 100% and complete occlusion with stasis of blood flow was recorded as 125% (stable occlusion).

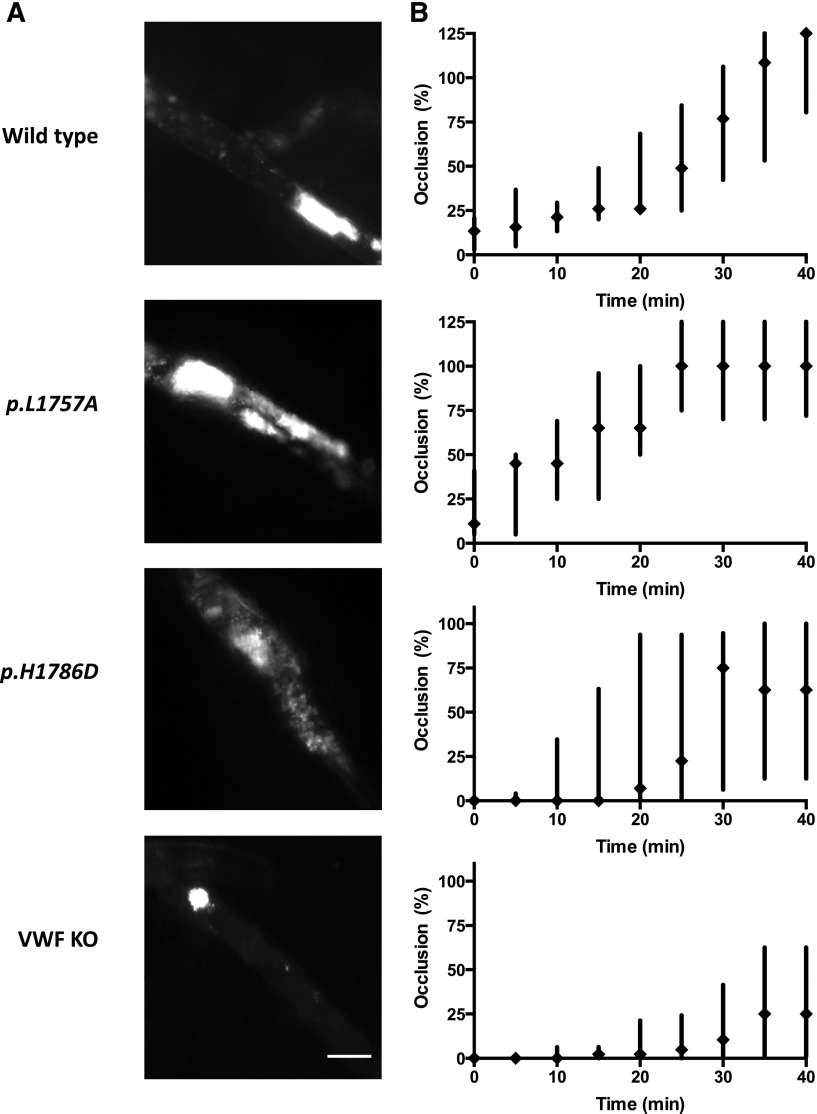

Figure 6.

In vivo assessment of VWF:CB variants using a ferric chloride-induced cremasteric arteriolar injury model. (A) Evaluation of thrombus size in the ferric chloride injury model. The cremaster muscle was exteriorized and platelets were labeled by the injection of rhodamine 6G via the catheter placed in the jugular vein. Thrombosis was induced by the application of 10% ferric chloride for 3 minutes. The injured area was observed for 40 minutes. Representative images of indicated group at 30 minutes after injury were shown. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) Occlusion time course of collagen-binding VWF variants. Intravital microscopy was performed with the VWF−/− mice expressing WT or collagen-binding mutant-mVWF via hydrodynamic injection. The p.L1757A gain-of-function mutant showed enhanced thrombus generation. In contrast, the p.H1786D loss-of-function mutant showed decreased thrombus generation. Thrombus generation was most reduced in the VWF−/− mice. However, even in these animals, residual thrombus activity of ∼25% occlusions were documented (n > 6). Scale bar, 50 μm.

Data presentation and statistical analysis

All data and statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.03 for Windows or 6.0 for Mac (GraphPad Software). Data are presented as mean values ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analyses were performed using the Student unpaired t test, 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), or 2-way ANOVA. For Figures 6B and 7B, data are presented as median values ± standard error of the median. For Figure 7C, Mann-Whitney tests were performed.

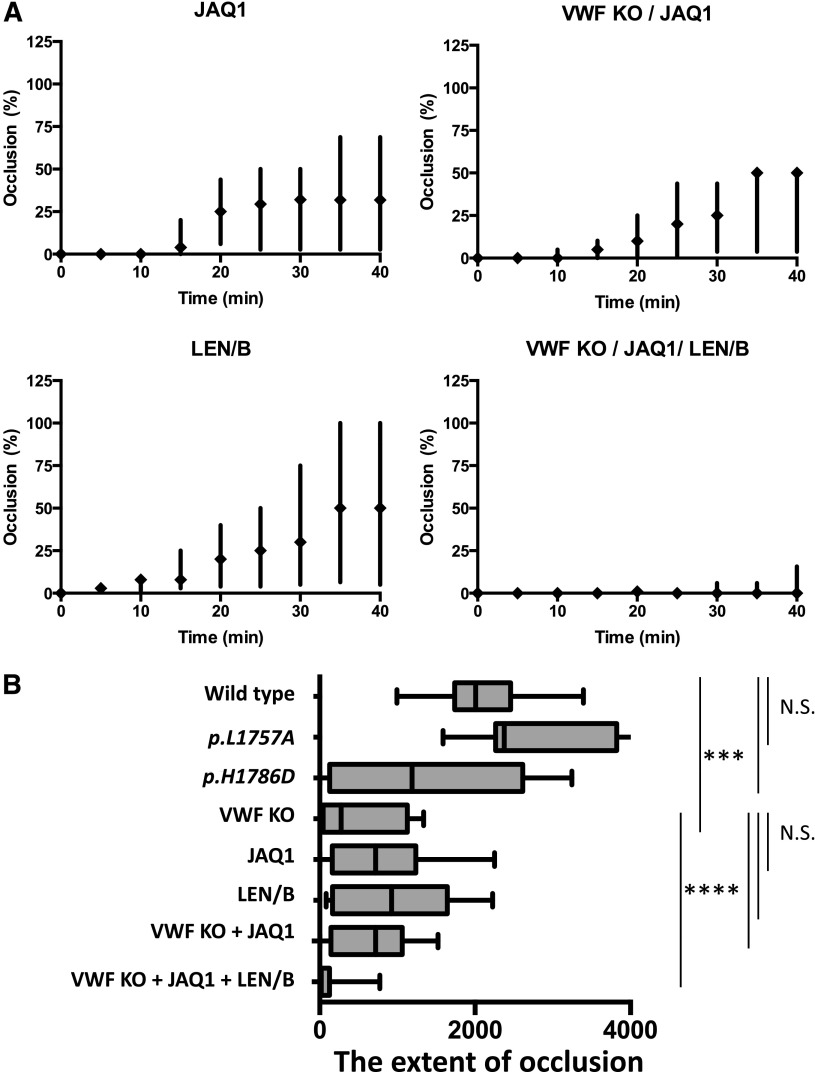

Figure 7.

Platelet- and VWF-mediated–collagen binding in a ferric chloride-induced cremasteric arteriolar injury model. (A) Impact of GPVI and α2β1 depletion in the ferric chloride injury model. Occlusion time course with the following mice: VWF−/− expressing WT-mVWF, treated with JAQ1 (GPVI depletion) (n = 6), LEN/B (α2β1 depletion) (n = 9), and VWF−/− mice treated with JAQ1 (n = 9) or both JAQ1 and LEN/B (n = 8). The impact of JAQ1 was similar to VWF−/−. However, the combination of both did not demonstrate further inhibition. LEN/B-treated mice demonstrated a milder phenotype. Treatment of both JAQ1 and LEN/B in VWF−/− mice markedly inhibited thrombus formation, although residual initial platelet adhesion was observed. (B) Summary of the extent of vessel occlusion in the intravital experiments. Box-and-whisker plots of occlusion extent for each injury condition. The extent of occlusion with each injury was defined as the integrated occlusion time course, determined by area under the curve using the trapezoidal rule. Median and interquartile range are shown. ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

Results

Expression and characterization of recombinant proteins

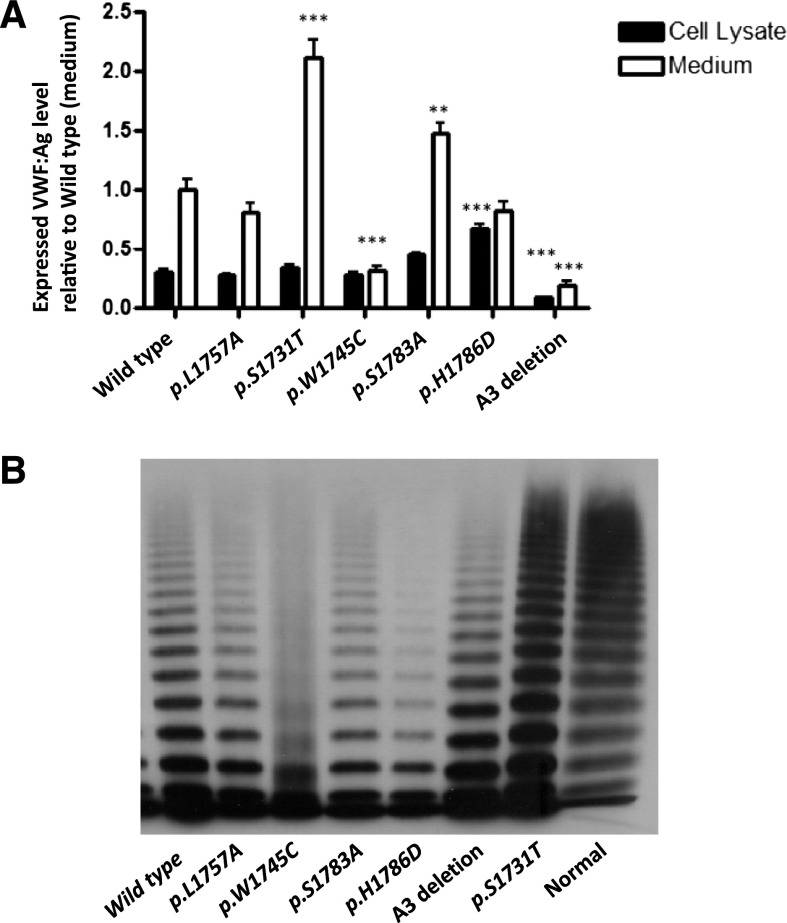

Results of recombinant mVWF levels measured both in cell lysate and medium are shown in Figure 1A. mVWF secretion did not differ significantly for p.L1757A-mVWF and p.H1786D-mVWF as compared with WT-mVWF. p.W1745C-mVWF and A3del-mVWF secretion into the medium was significantly lower than WT-mVWF (0.31, and 0.19, P < .001) whereas for p.S1731T-mVWF and p.S1783A-mVWF secretion was increased (2.11, P < .001, and 1.47, P < .01). Cell lysate retention of VWF was similar for the different recombinant proteins with the exception of A3 del-mVWF which was reduced (0.091, P < .00001) and p.H1786D-mVWF which was increased (1.68, P < .00001).

Figure 1.

Expression of recombinant mouse VWF:CB variants. (A) Transient transfection of murine VWF cDNA was performed in HEK293T cells and expressed in serum-free medium. Total VWF:Ag level in medium and lysates per 10-cm dish was measured via VWF:Ag ELISA and results were normalized to WT-VWF expressed in medium equal to 1 (n = 10). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001. (B) Multimeric analysis for r-mVWF. All of the mutant mVWFs had a normal complement of HMWMs, except p.W1745C, which showed a smeary multimer pattern. The A3 deletion mutant showed a triplet band shift corresponding to loss of the A3 domain.

Multimer analysis (Figure 1B) demonstrated that all of the mutant proteins had a similar complement of HMWMs to wt-mVWF except p.W1745C, which showed a smeary multimer pattern. The A3 deletion mutant showed a triplet band shift corresponding to loss of the A3 domain.

Collagen-binding activity

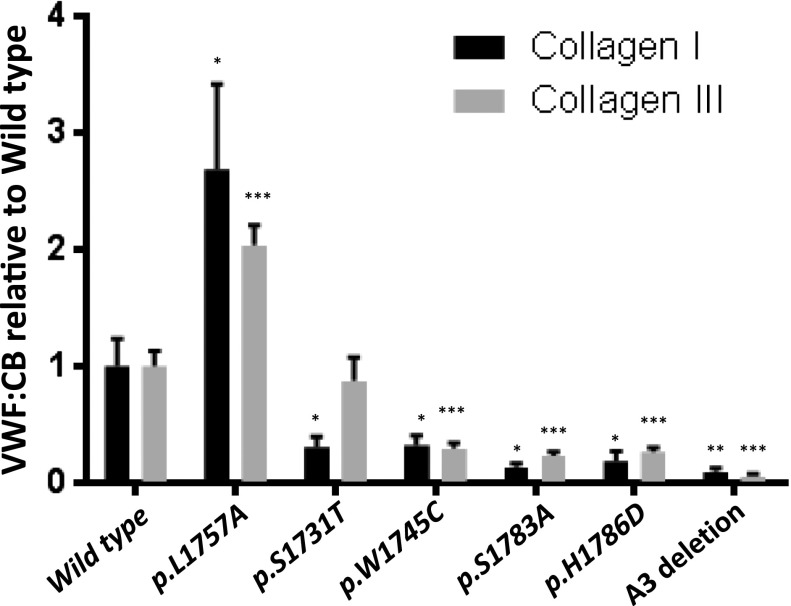

VWF function is closely related to its tertiary structure.31 In vivo, VWF is exposed to shear stress that alters VWF structure from a globular to extended configuration. In vitro collagen-binding activity of the r-mVWFs was assessed using 2 different methodologies: a static ELISA-based VWF:CB and a flow chamber system. The mutant VWF constructs, p.W1745C, p.S1783A, p.H1786D, and A3 deletion, demonstrated significant and parallel reductions in binding to type I and III collagen between 10.0% and 32.3% of WT-mVWF activity. In contrast, the p.S1731T-mVWF demonstrated a significant reduction of binding to only type I collagen (30.9%, P < .05), with normal levels of binding to type III collagen (87.7%, P > .05). The gain-of-function construct, p.L1757A, showed increased binding to both collagens (type I, 268%, P < .05, and type III, 204%, P < .001) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Static collagen-binding assay. The ability of mutant recombinant mVWFs to bind collagen type I or III was determined by ELISA and normalized to wild-type VWF. p.L1757A showed significant enhanced binding. p.S1731T showed distinct responses to collagen type I or III. The other mutations showed significant decreased binding (n = 8). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

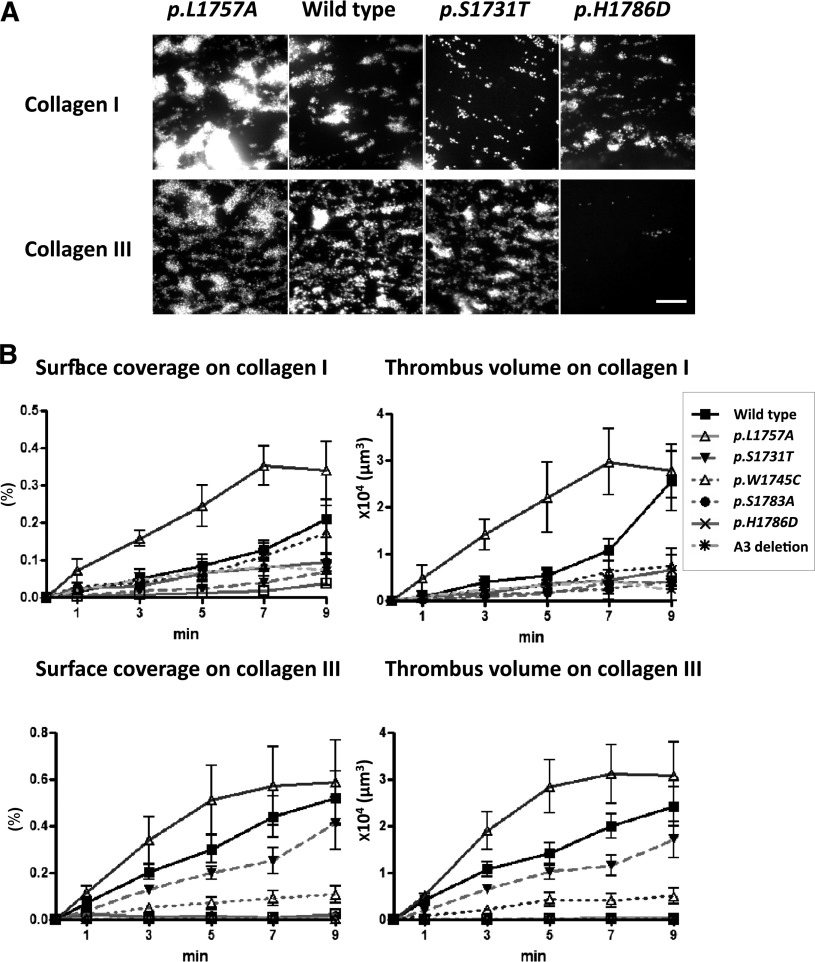

Using a flow chamber system, we demonstrate the ability of the r-mVWF proteins to mediate platelet adhesion to collagen under physiological high shear (Figure 3A). Compared with WT-mVWF, the p.L1757A-mVWF showed clearly increased platelet adhesion on both types I and III collagen surfaces, whereas p.H1786D-mVWF demonstrated decreased platelet adhesion. p.W1745C- and p.S1783A-mVWF imaging results were comparable to those of p.H1786D and are not shown. p.S1731T-mVWF demonstrated decreased platelet adhesion to collagen I with a subtle decrease in adhesion to collagen III. Figure 3B summarizes the image analysis of the flow chamber results. Using the parameters of surface coverage by platelets and volume of platelet adhesion on the collagen surfaces, p.L1757A-mVWF again shows accelerated and enhanced platelet adhesion (P < .01), whereas the loss-of-function mutants showed varying extents of functional deficit.

Figure 3.

r-mVWF mediated platelet adhesion under physiologic high shear. (A) Impact of collagen-binding mutants on collagen I or III surface under high shear conditions. Whole blood from VWF knockout mice containing DiOC6 (1 μM)–labeled platelets, anticoagulated with argatroban, was perfused over a type I or III collagen and recombinant mouse VWF-coated chamber under high shear rate (2500 S−1). Representative images of collagen-binding mutants at 7 minutes after perfusion. p.L1757A showed accelerated platelet adhesion on both collagen I and III surfaces. p.S1731T and p.H1786D showed decreased platelet adhesion. These images were constructed from spinning disk confocal laser scanning microscopy–based data on successive horizontal slices. The images are representative of 4 flow experiments. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) Flow-based analysis of platelet adhesion. Statistical analyses corresponding to the images in panel A. Error bars represent mean (± standard deviation) surface coverage and total thrombus volume in the flow experiments. Thrombus generation with the p.L1757A gain-of-function variant is accelerated and enhanced, whereas the loss-of-function mutants showed various degrees of functional deficit (n = 5).

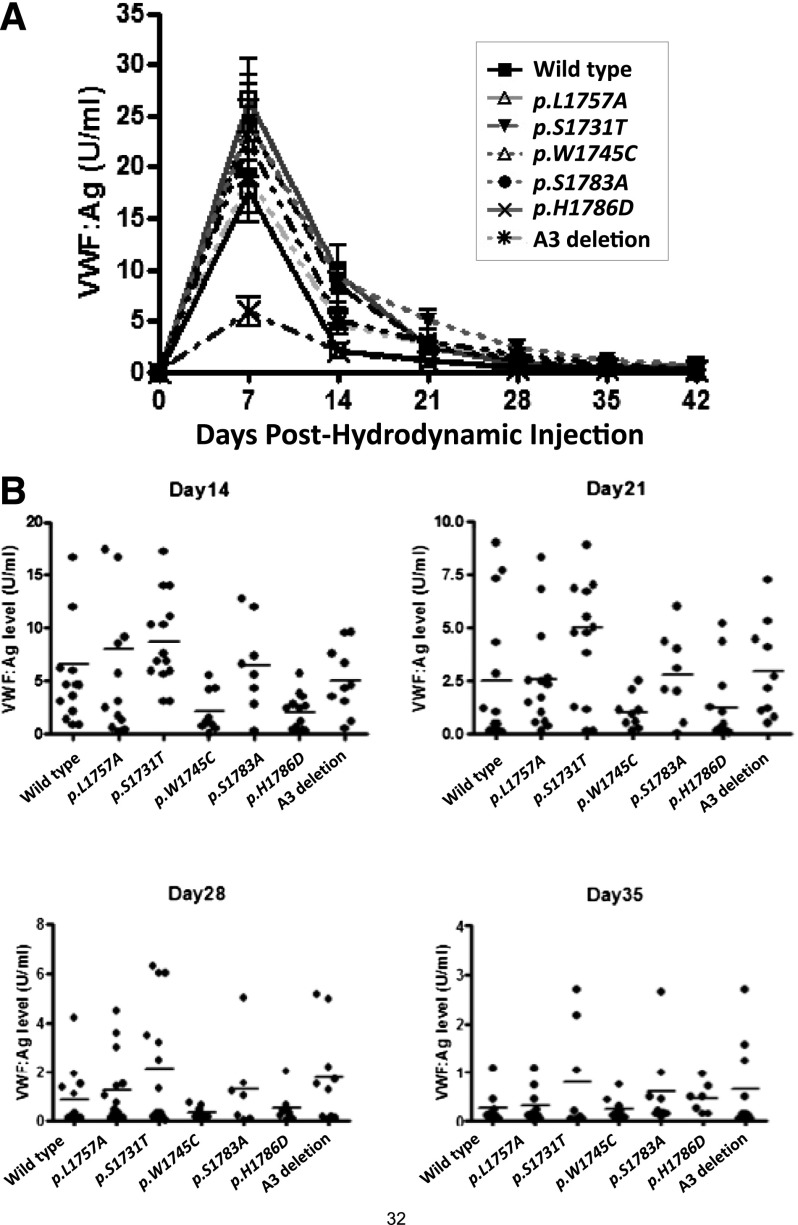

VWF transgene expression

VWF:Ag was monitored every 7 days in the mice hydrodynamically injected with the mVWF expression plasmids. Peak VWF levels were seen at day 7 (Figure 4A). The variability between the individual animals, compared with the mean, is shown in Figure 4B. When the plasma VWF levels were between 0.5 and 4.5 U/mL, intravital microscopy was performed: this occurred between 10 and 21 days posthydrodynamic injection. Similar to the expression from HEK293T cells, p.W1745C showed reduced expression in this hydrodynamic delivery system.

Figure 4.

Expression of mVWF in VWF−/− mice after hydrodynamic injection. (A) VWF:Ag levels after hydrodynamic injection (group data). VWF−/− mice were sampled every 7 days after hydrodynamic injection of the VWF expression plasmid (n > 8 for each group). (B) VWF:Ag levels after hydrodynamic injection (individual mouse responses). VWF knockout mice expressing collagen-binding mutants were sampled after hydrodynamic injection (n > 8). The levels of VWF:Ag for each individual mouse are shown at 14, 21, 28, and 36 days following the hydrodynamic delivery. The horizontal lines indicate mean values for each group.

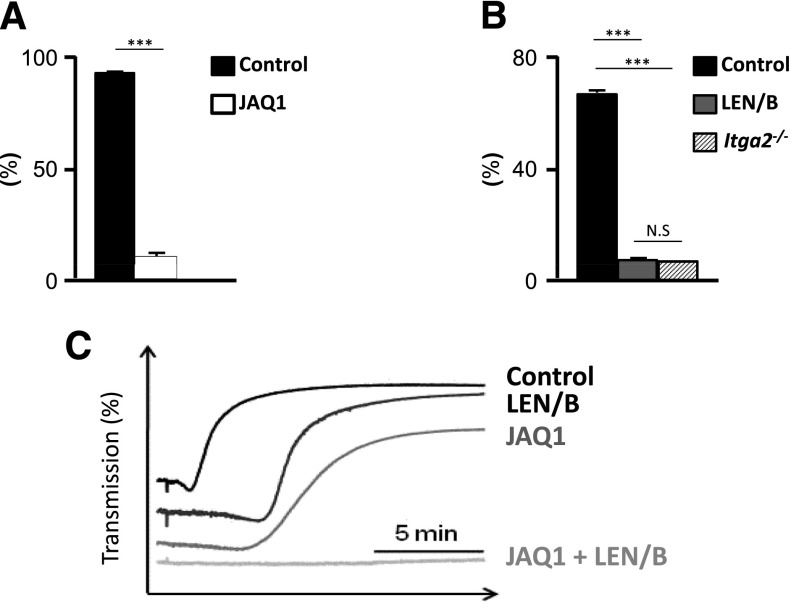

Effects of GPVI and α2β1 depletion with JAQ1 and LEN/B Abs

We explored the relative contribution of the platelet receptor GPVI and α2β1 on platelet adhesion to sites of vascular injury by using the anti-GPVI (JAQ1) and α2β1 (LEN/B) antibodies to transiently deplete the receptors.21 Injection of these antibodies had no effect on platelet count (data not shown). Flow cytometry shows effective blockade of the GPVI receptor that was statistically significant (P < .001, Figure 5A). α2β1 was also effectively blocked, with flow cytometry results that were comparable to platelets obtained from mice lacking α2β1 (Itga2−/−) (Figure 5B). In the collagen-induced platelet aggregation assay, LEN/B-opsonized platelets demonstrated delayed aggregation. The magnitude of the inhibition of aggregation was larger in JAQ1-treated platelets. However, combination of JAQ1 and LEN/B completely abolished platelet aggregation. (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of platelet collagen binding by JAQ1 and LEN/B. (A) Monoclonal anti-GPVI antibody (JAQ1) was injected intraperitoneally, and GPVI level was monitored by flow cytometric analysis. Platelets were detected by FITC-labeled anti-GPVI antibody (n = 6). The percentage of GPVI-positive platelets was significantly (P < .001) reduced following JAQ1 treatment after 3 days of injections. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of LEN/B-FITC binding to platelets from untreated mice (control), mice which received 100 µg of LEN/B, or mice lacking α2β1 (Itga2−/−).2 Results are MFI ± standard deviation of 4 mice per group. The inhibition of α2β1 by LEN/B was significant and comparable to Itga2−/−. (C) Washed platelets were incubated 10 minutes at 37°C with control IgG (control) or the indicated antibodies and subsequently stimulated with collagen. Light transmission was recorded on a Born aggregometer. Representative aggregation curves of 2 individual experiments (n = 4 each) are depicted. Delayed response in LEN/B-treated platelets and decreased response in JAQ1-treated platelets were observed. Aggregation was abolished with the inhibition of both. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; N.S, not significant; ***P < .001.

Evaluation of in vivo thrombogenesis

Ferric chloride-induced arteriolar injury monitored by intravital microscopy was performed on 6 to 9 mice in each of the following groups: VWF−/− mice, and VWF−/− transfected with WT-, p.L1757A-, or p.H1786D-mVWF. p.H1786D was chosen for this series of experiments as it represented the most severe loss-of-function defect in the VWF:CB assay and flow chamber analysis. After cremaster arteriolar damage with 10% ferric chloride for 3 minutes, the vessel was observed for 40 minutes. At the time of these experiments, the plasma VWF levels in the hydrodynamic-injected mice were between 0.5 and 4.5 U/mL. The rate and extent of thrombosis was analyzed as percentage occlusion by measuring the covered area of thrombus in the vessel. Representative images of each group (Figure 6A) and corresponding analysis are shown (Figures 6B, 7B). As compared with the WT-mVWF–expressing mice, the p.L1757A-mVWF gain-of-function mutant-expressing mice showed an increased rate of initiation and progression to a 100% thrombus though it was not statistically significant in the box-and-whisker plot analysis (Figures 6B, 7B).

The p.H1786D-mVWF–expressing mice demonstrated a nonstatistically delayed onset of platelet adhesion, decreased rate of extension of thrombosis, and failure to completely occlude the vessel in 8 of 9 mice. The lack of statistical significance is likely a result of the small study population. The VWF−/− mice demonstrated a variable degree of platelet adhesion and thrombogenesis, but none of the mice formed a stable occlusion of the vessel (P < .001).

To evaluate the impact of GPVI and α2β1 platelet receptors, we also included mice with the following: VWF−/− mice expressing WT-mVWF were treated with JAQ1 to inhibit GPVI binding (n = 6), or LEN/B (n = 9), and VWF−/− mice treated with JAQ1 (n = 9) or both JAQ1 and LEN/B (n = 8). All 4 groups demonstrated delayed initiation of platelet adhesion and attenuated thrombus formation with none of the mice being able to form stable occlusions at 40 minutes (JAQ1:P < .01, LEN/B:P < .05) (Figure 7A). The VWF−/− mice demonstrated the most severe hemostatic defect (P < .001), with no significant changes being seen with the addition of GPVI inhibition with JAQ1. The α2β1-inhibited group had the mildest phenotype of the 4 groups, with 3 of the 9 LEN/B-treated WT-mVWF group forming 100% occlusion within the observation time. Six of the 8 JAQ1- and LEN/B-treated VWF−/− mice demonstrated initial platelet adhesion (P < .0001). However, only 2 of them formed 25% occlusion.

Discussion

Type 2M VWD caused by collagen-binding mutations is rare: only 4 point mutations have been described in 12 patients; 11 were heterozygous for the collagen-binding mutation and 1 was compound heterozygous for a type 1 VWD mutation (Table 1). This suggests that collagen-binding mutations within the A3 domain have an autosomal dominant effect. We have used a series of comprehensive in vitro and in vivo strategies to characterize the functional deficit of the 4 mutations, p.S1731T, p.W1745C, p.S1783A, and p.H1786D, as well as a gain-of-function mutation, p.L1757A. Although the homozygous state evaluations used here allow for characterization of these mutant proteins, it may not reflect the disease process in humans where these mutations are expressed in the heterozygous state.

The static VWF:CB assay has been used in the diagnostic workup of VWD to aid in the discrimination between type 1 and types 2A/2B VWD, potentially eliminating the routine clinical use of VWF multimers or VWF:RCo.32 However, commercially available assays vary significantly in their ability to provide this discrimination.11 This manuscript highlights the role of the VWF:CB assay in identifying defective VWF collagen binding. VWD caused by collagen-binding mutations appears rare, although no systematic evaluation of its prevalence has been performed. The reported cases (summarized in Figure 1B) would have been diagnosed as type 1 VWD with parallel decreases in VWF platelet-dependent function and antigen level (RCo:Ag ratio >0.6) and normal multimer profiles, or would have been missed altogether with low-normal VWF:Ag and VWF:RCo levels. Studies have shown that over 50% of patients who present with symptoms consistent with a mild bleeding disorder will remain undiagnosed despite extensive investigations.33 The addition of the VWF:CB assay may not only allow for the accurate classification of apparent type 1 VWD, but also diagnosis of a subset of patients currently known as bleeders with undefined cause. The type, concentration, and source of collagen for clinical use also needs to be considered to optimize the detection of defective collagen binding. For example, the mutation p.S1731T showed marked differential binding to collagen types I and III in our study (Figure 2). This differential response was confirmed in our flow-chamber analysis (Figure 3) and by previously published data.17

VWF function is influenced by its conformational structure as determined by the shear rates of blood flow.34,35 At the site of vascular injury, VWF binds to exposed collagen through its A3 domain. Shear forces then induce conformational changes to the bound VWF resulting in changes to the VWF A1 domain that promote rapid and reversible attachment of platelets. Studies suggest that the VWF A1 domain may also play a role in binding to both type VI and type III collagen.3 This binding requires high-shear conditions and triggers platelet adhesion to immobilized collagen.4,36 The flow-chamber model allows in vitro evaluation of both A1 and A3 domain-mediated collagen binding and platelet adhesion via the A1 domain at physiological shear conditions.37 In this study, the pattern of collagen binding in the flow system was largely consistent with the results of the static collagen-binding assay, whereas the magnitude of the effect varied between the assays (Figures 2-3). The exception was p.W1745C-mVWF which showed significant differences in the flow system in surface coverage compared with thrombus volume with collagen type I. The explanation for this discrepancy is unclear. Consistent with the static VWF:CB assay, the p.S1731T mutant again showed a differential response: we demonstrated significantly decreased binding with collagen I but normal binding with collagen III when assessed by the static VWF:CB assay or only minimally defective function with type III collagen in the flow-based assay. In this flow system, we did not see a rescue of collagen/platelet binding by the VWF A1 binding to type III collagen with high shear rates as has been previously described.4,36

We evaluated the thrombogenic potential of the collagen-binding variants in an established in vivo thrombosis model using ferric chloride-induced cremaster arteriolar injury. This method has adequate sensitivity to differentiate normal VWF function from a range of type 1 and type 2 VWD mutations.24,30,38 The results from the thrombosis injury model are consistent with the static and flow-based collagen-binding studies, and differentiate the 3 groups of mice: the gain-of-function mutant, p.L1757A, from WT-mVWF, and loss of function, p.H1786D. In addition to the A3-collagen interaction, VWF likely mediates platelet adhesion through a number of complementary mechanisms: the binding of the A1 domain to collagen VI3 and possibly to collagen I/III,36 self-association of VWF, and the interaction of VWF and αIIbβIII.38 These mechanisms may account for the significant amount of thrombosis seen in the p.H1786D-mVWF mice despite collagen binding via the A3 domain being almost completely abolished, as seen in the VWF:CB assay and the flow experiments. Importantly, although platelet adhesion and thrombus formation was significantly reduced in VWF−/− mice using this model, there is residual thrombogenic activity. This has been previously described.28,38 We hypothesized that this residual platelet adhesion was mediated through a direct platelet-collagen interaction. Platelets interact with collagen through 2 receptors: the α2β1 integrin and GPVI. GPVI is reported to play a central role, whereas α2β1 has an accessory role.7 We transiently inhibited GPVI using the JAQ1 antibody and α2β1 using LEN/B in VWF−/− mice that expressed WT-mVWF through hydrodynamic delivery. Our results show important roles for VWF, GPVI and α2β1-mediated collagen binding, with GPVI inhibition proving to be as significant as VWF knockout on thrombus development. Consistent with previous publications,7 α2β1 inhibition resulted in a milder phenotype as compared with inhibition of GPVI. The addition of GPVI inhibition to VWF−/− mice did not demonstrate an additive defect to platelet binding whereas the inhibition of both GPVI and α2β1 in VWF−/− mice almost completely abolished any platelet binding. Unfortunately, further studies using the combination of VWF−/− with α2β1 inhibition, or VWF WT mice with both GPVI and α2β1 inhibition are outside the scope of this study. We hypothesize that GPVI and α2β1 have overlapping and complementary functions that account for the thrombosis seen in the GPVI inhibited VWF−/−.

We continued to demonstrate a small amount of platelet binding and initial thrombus generation in mice who were VWF−/− and whose platelet-collagen receptors, GPVI and α2β1, were inhibited. This suggests that an alternative pathway(s) that is independent of collagen binding supports delayed and reduced, but not abolished, platelet adhesion to sites of endothelial injury. Previous studies, using laser-induced vessel injury, demonstrated that platelet accumulation was largely independent of the collagen-VWF and collagen-GPVI interactions, and dependent on thrombin in this particular thrombosis model that is strongly influenced by tissue-factor–mediated thrombin generation.6,39,40 In contrast, the FeCl3 injury model has been reported to be dominated by collagen exposure, with up to 5 times less tissue factor as compared with a laser injury model.6 The delayed and reduced platelet adhesion seen in the face of inhibition of GPVI and α2β1 in the VWF−/− mice may be mediated by platelet interactions with other subendothelial adhesive proteins such as vitronectin and fibronectin.39 Alternatively, a recent report suggests that FeCl3 injury does not expose subendotheial matrices.41 The authors observe that red blood cells (RBCs) and RBC fragments are the first to adhere to the injured endothelium with the association between the endothelium and RBCs being unclear. Once bound, the RBC structures then bind platelets via GPIbα and initiation a thrombus in a collagen-independent manner.41 Our current data, in which we have focused on collagen-binding via either VWF or GPVI and α2β1, demonstrate the importance of collagen binding in the FeCl3 injury model. However, the small amount of platelet binding and thrombus initiation in the VWF−/− and GPVI- and α2β1-inhibitied mice may be accounted for by direct endothelial-RBC-platelet binding. The relative importance of this mechanism remains to be confirmed.

A3 domain collagen-binding mutants are associated with mild bleeding phenotypes and thus might be considered as safe candidates for antithrombotic therapy. However, the residual thrombus generation documented with the p.H1786D mutant in the ferric chloride injury studies suggests that the antithrombotic protection provided by these variants may be of limited value. No naturally occurring gain-of-function collagen-binding variant of VWF has been described. Increased VWF levels have been associated with cardiovascular disease and deep venous thrombosis.42-44 Our experiments with the gain-of-function collagen-binding mutation, p.L1757A, suggest that the associated phenotype would be thrombotic in nature and may have significant implications regarding risk of both arterial and venous thrombosis.

In conclusion, these studies present a comprehensive evaluation of 4 previously described VWD collagen-binding defects,15-17 a collagen-binding gain-of- function mutant (p.L1757A),20 and VWF with an A3 domain deletion. Because defects in collagen binding may be associated with normal VWF multimers, VWF:Ag, and VWF:RCo levels, the current approach to the diagnosis of VWD in many laboratories will miss these cases. Our results confirm the robustness of the VWF:CB assay and demonstrate that the results of this static assay are reflective of those obtained in a more complex, flow-based assay system. The results obtained with the VWF:CB were also in accordance with our findings in an in vivo thrombosis model. Overall, the findings in this study strongly support the standardization and inclusion of the VWF:CB assay in the routine workup of VWD.

Our studies examining the contribution of GPVI and α2β1 to primary hemostasis confirm that collagen binding by VWF, GPVI, and α2β1 have major roles in thrombus formation. Furthermore, the VWF−/−, GPVI, and α2β1 inhibited mice were still able to initiate platelet adhesion and thrombus formation in our ferric chloride injury model, demonstrating an important role for collagen-independent pathway(s) of primary hemostasis that likely contribute to the mild bleeding phenotype in patients with VWF collagen-binding mutations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Matthew Gordon for technical assistance.

This work was supported by operating grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP 97849), the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario (NA 6386), and the US National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (2PO1HL081588-06).

N.R. is the recipient of a Bayer Hemophilia Awards Program Clinical Training Award. D.L. is the recipient of a Canada Research Chair in Molecular Hemostasis.

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: Y.S. designed, performed, and interpreted the research, and wrote the manuscript; N.R. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript; D.S., C.B., J.M., K.S., O.D., B.C., B.V., C.A.H., and B.N., performed and analyzed the research; C.M.P. helped design the research; and D.L. provided the overall experimental design and direction of this work and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: David Lillicrap, Queen’s University, Richardson Laboratory, 88 Stuart St, Kingston, ON, K7L 3N6, Canada; e-mail: dpl@queensu.ca.

References

- 1.Cruz MA, Yuan H, Lee JR, Wise RJ, Handin RI. Interaction of the von Willebrand factor (vWF) with collagen. Localization of the primary collagen-binding site by analysis of recombinant vWF a domain polypeptides. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(18):10822–10827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lankhof H, van Hoeij M, Schiphorst ME, et al. A3 domain is essential for interaction of von Willebrand factor with collagen type III. Thromb Haemost. 1996;75(6):950–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoylaerts MF, Yamamoto H, Nuyts K, Vreys I, Deckmyn H, Vermylen J. von Willebrand factor binds to native collagen VI primarily via its A1 domain. Biochem J. 1997;324(Pt 1):185–191. doi: 10.1042/bj3240185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonnefoy A, Romijn RA, Vandervoort PA, VAN Rompaey I, Vermylen J, Hoylaerts MF. von Willebrand factor A1 domain can adequately substitute for A3 domain in recruitment of flowing platelets to collagen. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(10):2151–2161. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang I, Raghavachari M, Hofmann CM, Marchant RE. Surface-dependent expression in the platelet GPIb binding domain within human von Willebrand factor studied by atomic force microscopy. Thromb Res. 2007;119(6):731–740. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubois C, Panicot-Dubois L, Merrill-Skoloff G, Furie B, Furie BC. Glycoprotein VI-dependent and -independent pathways of thrombus formation in vivo. Blood. 2006;107(10):3902–3906. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nieswandt B, Brakebusch C, Bergmeier W, et al. Glycoprotein VI but not alpha2beta1 integrin is essential for platelet interaction with collagen. EMBO J. 2001;20(9):2120–2130. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siljander PR, Munnix IC, Smethurst PA, et al. Platelet receptor interplay regulates collagen-induced thrombus formation in flowing human blood. Blood. 2004;103(4):1333–1341. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadler JE, Budde U, Eikenboom JC, et al. Working Party on von Willebrand Disease Classification. Update on the pathophysiology and classification of von Willebrand disease: a report of the Subcommittee on von Willebrand Factor. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(10):2103–2114. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nichols WL, Hultin MB, James AH, et al. von Willebrand disease (VWD): evidence-based diagnosis and management guidelines, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Expert Panel report (USA). Haemophilia. 2008;14(2):171–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Favaloro EJ. Evaluation of commercial von Willebrand factor collagen binding assays to assist the discrimination of types 1 and 2 von Willebrand disease. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(5):1009–1021. doi: 10.1160/TH10-06-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budde U, Pieconka A, Will K, Schneppenheim R. Laboratory testing for von Willebrand disease: contribution of multimer analysis to diagnosis and classification. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2006;32(5):514–521. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-947866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Favaloro EJ. Detection of von Willebrand disorder and identification of qualitative von Willebrand factor defects. Direct comparison of commercial ELISA-based von Willebrand factor activity options. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;114(4):608–618. doi: 10.1309/2PMF-3HK9-V8TT-VFUN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Federici AB, Canciani MT, Forza I, Cozzi G. Ristocetin cofactor and collagen binding activities normalized to antigen levels for a rapid diagnosis of type 2 von Willebrand disease—single center comparison of four different assays. Thromb Haemost. 2000;84(6):1127–1128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flood VH, Lederman CA, Wren JS, et al. Absent collagen binding in a VWF A3 domain mutant: utility of the VWF:CB in diagnosis of VWD. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(6):1431–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ribba AS, Loisel I, Lavergne JM, et al. Ser968Thr mutation within the A3 domain of von Willebrand factor (VWF) in two related patients leads to a defective binding of VWF to collagen. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86(3):848–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riddell AF, Gomez K, Millar CM, et al. Characterization of W1745C and S1783A: 2 novel mutations causing defective collagen binding in the A3 domain of von Willebrand factor. Blood. 2009;114(16):3489–3496. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tosetto A, Rodeghiero F, Castaman G, et al. A quantitative analysis of bleeding symptoms in type 1 von Willebrand disease: results from a multicenter European study (MCMDM-1 VWD). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(4):766–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowman M, Mundell G, Grabell J, et al. Generation and validation of the Condensed MCMDM-1VWD Bleeding Questionnaire for von Willebrand disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(12):2062–2066. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishida N, Sumikawa H, Sakakura M, et al. Collagen-binding mode of vWF-A3 domain determined by a transferred cross-saturation experiment. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10(1):53–58. doi: 10.1038/nsb876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nieswandt B, Schulte V, Bergmeier W, et al. Long-term antithrombotic protection by in vivo depletion of platelet glycoprotein VI in mice. J Exp Med. 2001;193(4):459–469. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.4.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato K, Kanaji T, Russell S, et al. The contribution of glycoprotein VI to stable platelet adhesion and thrombus formation illustrated by targeted gene deletion. Blood. 2003;102(5):1701–1707. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenting PJ, de Groot PG, De Meyer SF, et al. Correction of the bleeding time in von Willebrand factor (VWF)-deficient mice using murine VWF. Blood. 2007;109(5):2267–2268. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-054718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi C-X, Graham FL, Hitt MM. A convenient plasmid system for construction of helper-dependent adenoviral vectors and its application for analysis of the breast-cancer-specific mammaglobin promoter. J Gene Med. 2006;8(4):442–451. doi: 10.1002/jgm.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vigna E, Amendola M, Benedicenti F, Simmons AD, Follenzi A, Naldini L. Efficient Tet-dependent expression of human factor IX in vivo by a new self-regulating lentiviral vector. Mol Ther. 2005;11(5):763–775. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pruss CM, Golder M, Bryant A, et al. Pathologic mechanisms of type 1 VWD mutations R1205H and Y1584C through in vitro and in vivo mouse models. Blood. 2011;117(16):4358–4366. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-303727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stakiw J, Bowman M, Hegadorn C, et al. The effect of exercise on von Willebrand factor and ADAMTS-13 in individuals with type 1 and type 2B von Willebrand disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(1):90–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denis C, Methia N, Frenette PS, et al. A mouse model of severe von Willebrand disease: defects in hemostasis and thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(16):9524–9529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marx I, Lenting PJ, Adler T, Pendu R, Christophe OD, Denis CV. Correction of bleeding symptoms in von Willebrand factor-deficient mice by liver-expressed von Willebrand factor mutants. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(3):419–424. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.159442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Golder M, Pruss CM, Hegadorn C, et al. Mutation-specific hemostatic variability in mice expressing common type 2B von Willebrand disease substitutions. Blood. 2010;115(23):4862–4869. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Springer TA. Biology and physics of von Willebrand factor concatamers. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(suppl 1):130–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flood VH, Gill JC, Christopherson PA, et al. Comparison of type I, type III and type VI collagen binding assays in diagnosis of von Willebrand disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(7):1425–1432. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quiroga T, Mezzano D. Is my patient a bleeder? A diagnostic framework for mild bleeding disorders. Hematology. 2012;2012:466-474. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Novák L, Deckmyn H, Damjanovich S, Hársfalvi J. Shear-dependent morphology of von Willebrand factor bound to immobilized collagen. Blood. 2002;99(6):2070–2076. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ulrichts H, Udvardy M, Lenting PJ, et al. Shielding of the A1 domain by the D’D3 domains of von Willebrand factor modulates its interaction with platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX-V. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(8):4699–4707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morales LD, Martin C, Cruz MA. The interaction of von Willebrand factor-A1 domain with collagen: mutation G1324S (type 2M von Willebrand disease) impairs the conformational change in A1 domain induced by collagen. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(2):417–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuchs B, Budde U, Schulz A, Kessler CM, Fisseau C, Kannicht C. Flow-based measurements of von Willebrand factor (VWF) function: binding to collagen and platelet adhesion under physiological shear rate. Thromb Res. 2010;125(3):239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marx I, Christophe OD, Lenting PJ, et al. Altered thrombus formation in von Willebrand factor-deficient mice expressing von Willebrand factor variants with defective binding to collagen or GPIIbIIIa. Blood. 2008;112(3):603–609. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-142943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dubois C, Panicot-Dubois L, Gainor JF, Furie BC, Furie B. Thrombin-initiated platelet activation in vivo is vWF independent during thrombus formation in a laser injury model. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(4):953–960. doi: 10.1172/JCI30537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mangin P, Yap CL, Nonne C, et al. Thrombin overcomes the thrombosis defect associated with platelet GPVI/FcRgamma deficiency. Blood. 2006;107(11):4346–4353. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barr JD, Chauhan AK, Schaeffer GV, Hansen JK, Motto DG. Red blood cells mediate the onset of thrombosis in the ferric chloride murine model. Blood. 2013;121(18):3733–3741. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-468983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conlan MG, Folsom AR, Finch A, et al. Associations of factor VIII and von Willebrand factor with age, race, sex, and risk factors for atherosclerosis. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Thromb Haemost. 1993;70(3):380–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spiel AO, Gilbert JC, Jilma B. von Willebrand factor in cardiovascular disease: focus on acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2008;117(11):1449–1459. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.722827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koster T, Blann AD, Briët E, Vandenbroucke JP, Rosendaal FR. Role of clotting factor VIII in effect of von Willebrand factor on occurrence of deep-vein thrombosis. Lancet. 1995;345(8943):152–155. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]