Abstract

An optofluidic bio-laser integrates biological materials into the gain medium while forming an optical cavity in the fluidic environment, either on a microfluidic chip or within a biological system. The laser emission has characteristics fundamentally different from conventional fluorescence emission. It can be highly sensitive to a specific molecular change in the gain medium as the light-matter interaction is amplified by the resonance in the cavity. The enhanced sensitivity can be used to probe and quantify the underlying biochemical and biological processes in vitro in a microfluidic device, in situ in a cell (cytosol), or in vivo in a live organism. Here we describe the principle of the optofluidic bio-laser, review its recent progress and provide an outlook of this emerging technology.

Fluorescence from dyes and fluorescent proteins has widely been used in analyzing biomolecules. The characteristics such as intensity and spectrum of the fluorescence emission vary in response to the molecular interactions associated with the fluorescence probes, thus generating a sensing signal. However, we often encounter situations where the signal is too weak and buried in the background noise. One may consider a radically different approach based on stimulated emission, rather than fluorescence, from the probe molecules by placing them in a laser cavity. This arrangement can amplify the process of signal generation and, therefore, could enable more sensitive detection and accurate analysis of biomolecules. Unlike biological amplification processes, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) that increases the sensing signal by simply multiplying the number of molecules, the signal amplification in the laser is accomplished through the optical feedback provided by the laser cavity.

Here emerges the optofluidic bio-laser laser, which is a new class of laser using biochemical or biological molecules in the gain medium. The sensing molecules are present in a fluidic environment, such as microfluidic devices1-6, within a live cell (cytosol)7 or, more broadly, interstitial tissue8,9. Since its debut less than a decade ago5,10-16, the optofluidic bio-laser has quickly been explored in biosensing7,17-25, outperforming or complementing the conventional fluorescence-based detection. In this Perspective, we describe the principle of laser-based detection, review various embodiments demonstrated to date and discuss the opportunity for technological innovation and broader applications.

Fluorescence-based detection vs. laser emission-based detection

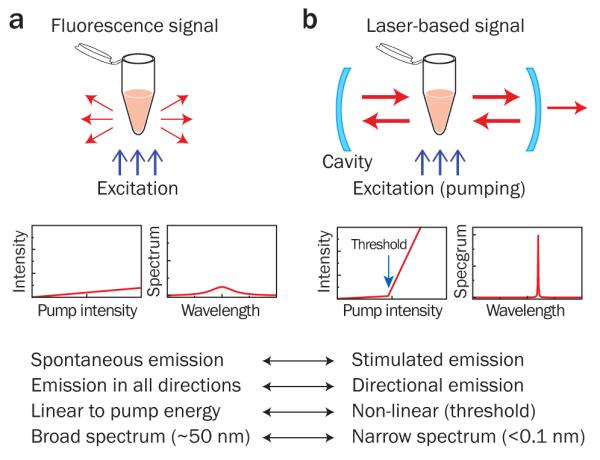

Moving from fluorescence-based detection to laser emission-based detection represents a significant paradigm change. Consider fluorescent molecules in a test tube (Fig. 1a). The fluorescence is emitted in all directions with a broad spectrum (30-70 nm). When the same sample is placed between a pair of mirrors (Fig. 1b), a portion of the fluorescence is confined within the cavity defined by the mirrors and amplified by stimulated emission in the test tube each time the light passes through the gain medium (Box 1). The resulting emission from the cavity features spectral, spatial, and temporal characteristics distinctly different from those of fluorescence in many respects. The laser emission is generated in a specific direction(s) determined by the cavity, and hence the output intensity tends to be much higher than the omnidirectional fluorescence light. In addition, the output intensity exhibits a distinct threshold behavior and its spectrum is narrower by several orders of magnitude.

Figure 1. Comparison of fluorescence-based detection and laser-based detection.

a, Fluorescence emission from a sample in a cuvette. Left graph, fluorescence output intensity as a function of the pump intensity. Right graph, typical broad fluorescence spectrum. b, Laser emission from the same sample placed inside a laser cavity. Left graph, laser output intensity; Right graph, typical narrowband laser spectrum. Above threshold, many characteristics of laser emission are different from those of fluorescence emission, and so are their responses and sensitivities to the biochemical and biological changes occurring in the cuvette.

Box 1. OPTOFLUIDIC BIO-LASERS.

An optofluidic laser consists of three essential components: (1) gain medium in the fluidic environment, (2) optical cavity and (3) pumping. The photons emitted from the gain medium are trapped by the cavity, and the optical feedback induces stimulated emission. When the cavity has a sufficient number of gain molecules excited by pumping, the available gain becomes greater than the total loss in the cavity and laser oscillation builds up. The lasing threshold condition is expressed as42:

| (1) |

where n1 and n0 are the concentration of the gain molecules in the excited and the ground state, respectively. σe and σa are the emission and absorption cross-section of the molecule, respectively, at the lasing wavelength, λ. γc is the cavity loss coefficient. Below the threshold, the output through the highly reflecting mirror comprises only weak spontaneous fluorescence emission. Above the threshold, the output intensity increases dramatically as coherent stimulated emission builds up and grows linearly with the pump energy with a much greater slope than the fluorescence emission (Fig. 1)42.

To reach the laser threshold, sufficient pumping is required. It is shown42 that the pump intensity necessary to excite 50% of the total fluorescent molecules (i.e., n1=n0) is Ip=hνp/(τσp), where h is the Planck constant, νp is the pump light frequency, τ is the lifetime of the excited state, and σp is the absorption cross-section at the excitation wavelength. For the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP, σp=2.1×10−16 cm2, τ=~3 ns) and an excitation wavelength of 488 nm (hνp=4.1×10−19 J), the required pump intensity is Ip=6.5×105 W/cm2, which can readily be obtained with a pulsed laser. Assuming that the pulse duration, τp, is equal to the excited state lifetime, the required pump flux to excite half of the molecules is given by Fp=τpIp=20 μJ/mm2. This intensity is two orders of magnitude lower than the maximum permissible power for biological tissues43.

Cavity quality factor, or Q-factor, determines the cavity’s capability to trap photons. Q-factor is inversely proportional to the cavity loss γc. The higher Q-factor, the lower concentration of the gain molecules and lower pump energy are required to reach the threshold. The intrinsic spectral linewidth Δλc of the cavity is given by Δλc/λ=1/Q. The resonance wavelength of the cavity is sensitive to the average refractive index inside the cavity, with a linear relationship: δλ/λ=δn/n, where δn/n is the relative index change.

Laser cavity

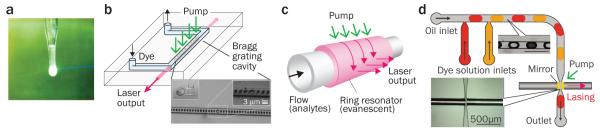

One of the earliest examples was a liquid-based dye laser (Fig. 2a)44. Fluorescein dye is dissolved in the substrate of biocompatible “edible” Jell-O material. Without having a specific cavity structure, the dye solution in gelatin produces amplified spontaneous emission upon intense pumping. Optical feedback by a cavity is essential for laser oscillation. To date, different types of cavities compatible with fluidic gain media have been demonstrated, including distributed feedback gratings12,13,45 (Fig. 2b), optical ring resonators (Fig. 2c)14,18,20-23,25,46-54 and Fabry-Pérot cavities (Fig. 2d)7,10,19,55,56. Other types of cavities, such as photonic crystals and disordered media, have also been explored8,9,28,57. The typical Q-factor ranges from 102 (for Fabry- Pérot cavities) to >107 (for ring resonators).

Gain medium

Any fluorescent materials in fluorescence-based detection can potentially be used for a laser, including dyes18,20,22, luciferin58, Vitamin B225, quantum dots53, enzyme-activated substrates and fluorescent proteins in vitro and inside a live cell7,19,23. In addition to a single type of fluorophore, two or more types of molecules can be used in the gain medium. Particular, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) pair and a fluorophore-quencher pair are useful for measuring biomolecular interactions and conformational changes. A small change of the energy transfer efficiency between the donor and acceptor can result in a large variation of the laser output.

Pumping

Optical pumping is the most effective method known to date for the optofluidic bio-laser. Typically a pulsed pump laser is used, such as a Q-switched solid-state laser and an optical parametric oscillator. The optimal duration of the pump pulse is approximately a tenth to several times of the excited state lifetime of the gain molecule. Depending on the cavity Q-factor, and the composition and concentration of the gain medium, the lasing threshold is typically achieved at a pump intensity of 10 nJ/mm2 to 100 μJ/mm2 per pulse10,12,13,20,23,56,58,59. A single excitation pulse is sufficient for a single measurement, but averaging over multiple pulses improves the measurement accuracy. Excessive pump energy should be avoided to prevent heating, which may damage the biomolecules and cause bleaching of the gain molecules. Continuous wave (CW) lasers are compact and inexpensive and have a wider selection of wavelengths, but do not provide sufficient intensity to reach the threshold16. A CW-excited optofluidic laser has not yet been demonstrated. Depending on the specific mechanism of molecular excitation, the pumping method can be categorized as direct and indirect excitation. For direct excitation, the pump laser is tuned into the absorption band of the fluorophore. Indirect excitation relies on energy transfer such as FRET to transfer the excitation energy from the donor to the acceptor for the acceptor to lase.

Sensing

As Eq. (1) implies, the characteristics of laser emission are governed by several factors, such as the emission cross-section (σe)21, the concentration of fluorophores (n1) in the excited states20,23, and the absorption cross-section (σa), as well as the cavity loss (γc)17. In an optofluidic bio-laser, these parameters can vary in response to specific biomolecular interactions and conformation changes. In turn, by monitoring the changes in the laser output characteristics, such as the intensity, spectrum, and threshold, the underlying biochemical and biological processes can be revealed. Relatively high concentrations of gain molecules, typically ranging from 1 μM to 10 mM, may be required to reach the laser threshold. However, the primary advantage of laser-based detection is not necessarily to detect low concentrations of analytes (detection of analytes below fM is possible by employing enzyme-substrate reactions in a laser cavity, as discussed later in this Perspective) but to discern the otherwise hard-to-distinguish small signals resulting from the biochemical interaction and biological process of interest (see the examples in Fig. 3). Due to the improved SNR, the sensing dynamic range of the laser-based detection is one to three orders of magnitude higher than the fluorescence-based detection15,22.

The laser output characteristics are sensitive to the specific condition of the gain medium. Consider a situation where the number of gain molecules has increased as a result of some biochemical or biological process in the test tube. This change increases the amount of optical gain available and may also change the refractive index of the medium. These variations in the cavity alter the intensity of light in the cavity and the cavity resonance condition. In the cavity, resonant light is bounced back and forth between the mirrors and interacts with the gain medium thousands to millions of times, depending the total gain and cavity Q-factor (Box 1). Through this enhanced interaction between the light and molecules, the sensing signal is amplified. Consequently, the output intensity, spectrum, threshold, and other characteristics can provide highly sensitive readouts of the biochemical and biological change occurring in the cavity. The above signal enhancement mechanism is fundamentally different from the external amplification by an optical amplifier before a photodetector, in which both the signal and noise in the light are simultaneously increased without enhancing the signal-to-noise-ratio (SNR) of measurement.

Call-out Box 1

Current implementations and applications to sensing

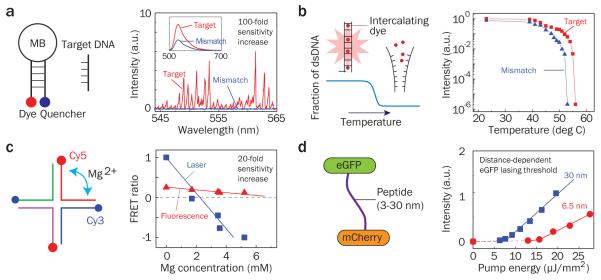

In the past few years, various types of optofluidic lasers have been developed (see Fig. 2) and applied to a number of sensing applications for DNAs20-22, proteins7,23, and cells7. Differentiation of target 16-mer DNA and its single-base mismatched counterpart was achieved by using molecular beacons (MBs) inside a laser cavity (Fig. 3a)20. Lasing light circulating in the cavity interacts with the gain medium that is modulated by the number of open MBs. Higher gain is obtained with the target DNA than the mismatched DNA, as more MBs are open. This difference in the gain medium translates to a significant differential intensity ratio of about 240 between the target and the mismatched DNA compared to a ratio of 2 in conventional fluorescence-based detection, which represents over 100-fold advantage in sensitivity. Similar results have been obtained with breast cancer gene BRCA1 in serum20.

Figure 2. Optofluidic lasers.

a, Stimulated emission from a droplet of fluorescein disodium salt in “edible” gelatin, demonstrated by T. W. Hänsch and A. L. Schawlow in 1970. b, Optofluidic laser based on a distributed feedback grating embedded in a microfluidic channel. c, Optofluidic laser sensor using evanescently-coupled ring resonator. d, Optofluidic laser using dye micro-droplets and an integrated Fabry-Pérot cavity formed by two reflectors coated on optical fiber tips. Figure reproduced with permission from: a, ref. 44 © 2005 OSA; b, adapted from ref. 13 © 2006 OSA; c, adapted from ref. 22 © 2012 RSC; d, ref. 56 © 2011 AIP.

Figure 3. Biochemical sensing applications of optofluidic lasers.

a, Distinguishing the target DNA (16-mer) and the single-base mismatched DNA using molecular beacons. The differential ratio between the target and the mismatch is approximately 240, compared to only ~2 in the fluorescence-based detection using the same molecular beacons (inset). b, Melting curves for 40-base long target DNA and single-base mismatched DNA using laser emission from intercalating dyes. The transition temperature differs by 3 °C between the target and the mismatch. c, Detection of the Holliday junction conformational change upon addition of magnesium ions. d, Peptide length-dependent FRET. The long-linked (30 nm) and the short-linked (6.5 nm) FRET pairs have drastically different effects on the laser threshold. Figure reproduced with permission from: a, ref. 20 © 2012 Wiley-VCH; b, ref. 21 © 2012 ACS; c, ref. 22 © 2012 RSC; d, ref. 23 © 2013 RSC.

In DNA melting analysis21 (Fig. 3b), the stimulated emission from DNA intercalating dyes is modulated by the concentration of double-stranded DNA. At temperatures lower than 40 °C, the gain is high due to the presence of a large fraction of double-stranded DNA. As the temperature increases, double-stranded DNA gradually melts into single-stranded DNA and the intercalating dye loses its emission capability (i.e., σe), leading to a decrease in the gain. At temperatures above 50 °C the gain becomes so low that it can no longer sustain the laser oscillation. Consequently, a sharp transition from laser emission to residual fluorescence occurs, with a dramatic output intensity change by six orders of magnitude. A differential ratio as large as 104 is achieved between the target and the single-base mismatched DNA around the transition temperature, in comparison with only 1.4 obtained with the fluorescence-based detection (i.e., sensitivity enhancement by ~10,000). Melting analysis of double-stranded DNA up to 100 base pairs has been demonstrated21.

Detection of conformational changes of biomolecules can be accomplished by using a FRET pair as the gain medium. In a recent study the Holliday junction was used as a model system (Fig. 3c), which can reversibly be tuned by magnesium ionic strength22. When the Holliday junction is open, the laser emission is generated only from the donor dye, Cy3. With increased Mg2+ concentration, the junction closes gradually, allowing FRET to occur from Cy3 to Cy5. Therefore, the gain for the Cy5 laser increases at the expense of the donor gain, which decreases the Cy3 laser emission and increases the Cy5 laser emission. The intensity ratio of the donor and acceptor laser emission, or the FRET ratio, varies with the Mg2+ concentration at a much higher sensitivity than the conventional FRET detection. In addition to DNA structures, proteins or peptides can be analyzed7,23. Fluorescent protein pairs, such as eGFP and mCherry, are another choice for FRET laser sensing23. For a long-linked FRET pair (30 nm), energy transfer from eGFP to mCherry is negligible. Therefore, strong laser emission is observed from the eGFP (Fig. 3d)23. In contrast, when a shorter linker (6.5 nm) is used, higher (17%) energy transfer occurs, which results in 25-fold reduction in the laser emission from the eGFP.

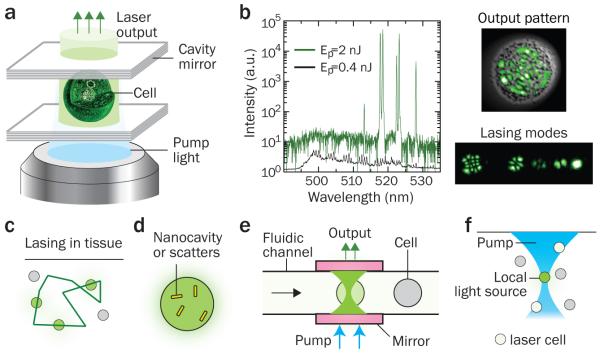

The optofluidic laser can further be extended to cells and other biological entities. The first cell laser was demonstrated by using the cytoplasm with eGFP molecules as the gain medium (Fig. 4a)7. The eGFP-expressing cell is inserted into a miniature cavity and excited with nanosecond pulses of blue light. The output of the cell laser shows spatial and spectral patterns (i.e., transverse and longitudinal modes, respectively), which provides quantitative parameters such as the number of modes (laser lines), the wavelengths of spectral lines, the relative and absolute intensity of each mode, and the overall beam profiles, as well as the total output intensity (Fig. 4b). Lasing cells can remain alive even after prolonged lasing action up to 1,000 pulses at 50 nJ/pulse (<500 μJ/mm2 per pulse). Minute differences in the gain and refractive index topography within different cells influence the selection of the laser-active modes and their spectral shape. For instance, the number of concurrently lasing transverse and longitudinal modes and their relative brightness depend on various factors, including the concentration of gain molecules, their spatial distribution, cell size, etc. This feature can therefore be used as a fingerprint of each cell and could enable intracellular sensing.

Figure 4. Cell-based optofluidic lasers.

a, Schematic of a cell laser. The eGFP-expressing cell is placed inside an optical resonator consisting of two parallel mirrors 20 μm apart. When excited by a 5-ns pump pulse, the cell generates coherent laser emission. b, Output characteristics of the cell laser. Left, emission spectra below (green line) and above (black line) the lasing threshold (0.7 nJ/pulse). The spectrum is plotted on the log-scale to emphasize contrast between laser lines and fluorescent background. Right Top, the profile of a higher-order lasing mode (green), superimposed on a cell image (gray); Right Bottom, several lower-order laser modes distinguished by ***hyperspectral imaging. c, Random laser based on close-loop multiple scattering in tissue. d, Illustration of a lasing cell employing intracellular plasmonic nano-resonators or random-scattering nanoparticles. e, Optofluidic laser cytometry. f, Turning on a lasing cell as remote light source in a tissue. Figures in a & b are adapted from: ref. 7, © 2011 NPG.

Outlook

The optofluidic bio-laser is still in its infancy; many opportunities are worth exploring. From technological perspectives, it is expected that more advanced laser designs and strategies will continue to develop:

(1) Ultrahigh Q-factor cavity. While some types of ring resonators can achieve a high Q-factor over 107, most of the optofluidic cavities have a Q-factor on the order of 102–103. Improving Q-factor by advanced cavity designs will significantly enhance the laser sensing performance by lowering the lasing threshold and the required analyte concentration, and increasing the sensitivity.

(2) Photonic crystal-based optofluidic lasers. A photonic crystal is a periodic micro/***nanosized dielectric structure26. The voids in the photonic crystal provide sample containment with a volume ranging from femto-liters to pico-liters. In photonic crystals, the optical feedback and interaction between light and biomolecules can be engineered with high precision using micro/nano-lithographic technologies.

(3) Random lasers. The random laser uses a turbid gain medium, where stochastically formed, closed-loop scattering paths provide optical feedback and generate stimulated emission8,9,27,28 (Fig. 4c). Since the random laser does not require mirrors, when implemented in tissue it can generate laser emission without embedding physical objects to form a cavity. It has been shown that pumping dye molecules in turbid soft tissues and bones can generate coherent random-laser light8,9. Extending this principle, it might be possible to generate random-laser light from a cell containing scattering particles in the cytosol, which would lead to a stand-alone cell laser.

(4) Plasmonic nanocavity lasers. Substantial efforts have been made to develop miniature lasers with sub-femto-liter volumes. Lasing was observed from semiconductor nanowires29 and by using surface plasmon polariton modes confined in metallic nanostructures30-33. One may envision submicron-scale stand-alone lasers to operate in the fluidic environment. Such lasers may be inserted into a cell (Fig. 4d), generating stimulated emission that is highly sensitive to the evanescent interaction with the gain or absorbing molecules in the cytosol.

(5) Pump laser. To make the optofluidic laser more accessible, it is desirable to have an inexpensive and miniature pump laser. Palm-sized solid-state pulsed lasers (10 ns, <1 μJ) are commercially available, but further developments of pump lasers at lower cost with more options for wavelength, shorter pulse durations (0.1–1 ns, for lower threshold energy) and higher repetition rates (>1 kHz) are anticipated.

(6) Lasers without optical excitation. Alternative pumping by electrical, chemical, and electrochemical mechanisms34 is challenging but can significantly extend the bio-laser to applications where optical excitation is difficult or impossible.

From application perspectives, we expect improvement in the performance of optofluidic bio-laser sensors and the emergence of novel concepts of sensing and other applications at the molecular, cellular and tissue levels:

(1) In vitro biomolecular analysis. Owing to its superior capability to differentiate small changes in the underlying biochemical and biological process, the optofluidic laser can be used to detect small thermal dynamic differences and conformational changes in biomolecules. Potential applications include analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphism for DNA sequences over thousands of bases long and protein conformational change upon external stimuli (such as drug molecules). Other existing biotechnologies can also be incorporated in the laser. For example, DNA scaffold or origami technology provides a means to precisely control the spatial distribution and stoichiometry of fluorophores through well-defined and self-assembled DNA nanostructures18,35, which may change in response. A combination of DNA nanostructures with the laser will open a door to a broad range of biomolecular sensing. Traditional ELISA technology can be used in the optofluidic laser, where the gain medium is provided by the fluorescent products through enzyme-substrate reaction. Recently it has been shown that the optofluidic ELISA laser is capable of detecting IL-6 below 0.1 pg/mL, boding well for detection of molecules at extremely low concentrations (Wu et al., unpublished). Certainly one of the important goals in biosensing is to detect and analyze biomolecules at the single molecule level. By single-molecule detection, it means both detecting the presence of a single analyte and, more importantly, distinguishing the changes caused by the single analyte.

(2) Biological analysis in live cells. Single-cell lasing can be adapted for optofluidic (flow) cytometry (Fig. 4e) (Gather et al., unpublished). Besides fluorescent proteins, it is possible to build cell lasers by using biocompatible chemical dyes, which may be chosen to selectively stain the nuclei, specific organelles, or plasma membranes. The directional, bright and nanosecond pulsed emission increases the throughput and speed of analysis. The inherently narrowband laser emission may enable multiple co-staining by dense wavelength multiplexing (N>10), for example, by incorporating intracellular cavities with distinct resonance peaks into cells containing the same or similar gain molecules, which are not easily distinguishable by conventional fluorescence detection because of the spectral overlap. Furthermore, it should be possible to generate laser light by putting the gain medium outside a cell. In this case, the laser output characteristics are affected by the three-dimensional refractive-index profile of the cell in the same way as in the case where the gain molecules are in the cell, and thus could enable label-free cellular phenotyping with the greater sensitivity than conventional scattering-based cytometry. The cell laser may serve as a useful platform for intracellular analysis of biological activities in situ in real-time. For example, genetically encoded protein FRET pairs can be placed on the surface of or inside a live cell to probe the extracellular local environment and biological change occurring inside a cell. One important application is to screen libraries of small molecules in live cells. The enhanced sensitivity of laser-based sensing may prove useful for distinguishing the compounds that activate or inactivate proteins and for rank-ordering them based on their relative efficacy. For better understanding of cells, laser detection can be combined with cell imaging, which provides spatial information as well as molecular information. Micro-mirrors with high curvature may be employed for high-resolution intracellular sensing or cytometry.

(3) Biological analysis in tissues and other potential applications. Laser-based detection at the tissue level will be a leap-forward to interface optofluidic bio-lasers directly with diagnostic applications. It might be possible to analyze a labeled histological tissue section with laser-based detection by placing it between a pair of mirrors. Stimulated emission is an emerging scheme to improve resolution and sensitivity of microscopic imaging, which has led to the invention of stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy36, stimulated Raman scattering (SRS) microscopy37, and pump-and-probe microscopy38,39. It should be possible to place laser cells with intracellular cavities in tissue and turn on them selectively by using a focused pump beam, where the lasing threshold is reached only at the focal region (Fig. 4f). Each lasing cell serves as a local light source emitting coherent, narrowband light, which may be used for low-background imaging and phototherapy with three-dimensional resolution. The spatial and temporal characteristics of a random laser formed in tissue can provide information about the structural and viscoelastic properties of the tissue and, therefore, may be applied for diagnosis of diseases, such as cancer and atherosclerosis8,40, and for optical micro-rheometry41. By using a focused pump beam, three-dimensional analysis of tissue would be possible. Furthermore, in vivo optical amplification by gain molecules may offer an effective method to increase the penetration depth of light by compensating the optical attenuation in sensing, imaging, and therapy.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the support from the National Science Foundation (grants CBET-1037097, ECCS-1045621 and CBET-1158638 to X.F., and ECCS-1101947 and CBET-1264356 to S.Y.) and National Institutes of Health (P41EB015903 to S.Y.). D. Psaltis, Z. Li, and M. Gather are acknowledged for providing original figures (Figs. 2b and 4b) and Ian White for proofreading the manuscript.

References

- 1.Psaltis D, Quake SR, Yang C. Developing optofluidic technology through the fusion of microfluidics and optics. Nature. 2006;442:381–386. doi: 10.1038/nature05060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monat C, Domachuk P, Eggleton BJ. Integrated optofluidics: A new river of light. Nature Photon. 2007;1:106–114. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan X, White IM. Optofluidic Microsystems for Chemical and Biological Analysis. Nature Photon. 2011;5:591–597. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2011.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt H, Hawkins AR. The photonic integration of non-solid media using optofluidics. Nature Photon. 2011;5:598–604. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawkins AR, Schmidt H. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fainman Y, Lee LP, Psaltis D, Yang C. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gather MC, Yun SH. Single-cell biological lasers. Nature Photon. 2011;5:406–410. *First live cell laser.

- 8.Polson RC, Vardeny ZV. Random lasing in human tissues. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004;85:1289–1291.. *Random lasers are important in dealing with disordered gain media such as tissues.

- 9.Song Q, et al. Random lasing in bone tissue. Opt. Lett. 2010;35:1425–1227. doi: 10.1364/OL.35.001425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helbo B, Kristensen A, Menon A. A micro-cavity fluidic dye laser. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2003;13:307–311. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng Y, Sugioka K, Midorikawa K. Microfluidic laser embedded in glass by three-dimensional femtosecond laser microprocessing. Opt. Lett. 2004;29:2007–2009. doi: 10.1364/ol.29.002007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balslev S, Kristensen A. Microfluidic single-mode laser using high-order Bragg grating and antiguiding segments. Opt. Express. 2005;13:344–351. doi: 10.1364/opex.13.000344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Z, Zhang Z, Emery T, Scherer A, Psaltis D. Single mode optofluidic distributed feedback dye laser. Opt. Express. 2006;14:696–701. doi: 10.1364/opex.14.000696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shopova SI, Zhu H, Fan X, Zhang P. Optofluidic ring resonator based dye laser. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007;90:221101. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shopova SI, et al. Opto-fluidic ring resonator lasers based on highly efficient resonant energy transfer. Opt. Express. 2007;15:12735–12742. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.012735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z, Psaltis D. Optofluidic dye lasers. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2007;4:145–158. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galas JC, Peroz C, Kou Q, Chen Y. Microfluidic dye laser intracavity absorption. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006;89:224101. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Y, Shopova SI, Wu C-S, Arnold S, Fan X. Bioinspired optofluidic FRET lasers via DNA scaffolds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:16039–16042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003581107. *Optofluidic bio-laser through DNA controlled FRET processes.

- 19.Gather MC, Yun SH. Lasing from Escherichia coli bacteria genetically programmed to express green fluorescent protein. Opt. Lett. 2011;36:3299–3301. doi: 10.1364/ol.36.003299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun Y, Fan X. Distinguishing DNA by Analog-to-Digital-like Conversion by Using Optofluidic Lasers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:1236–1239. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107381. *First paper to use the optofluidic bio-laser for analysis of biomolecular interactions. Theoretical analysis therein laid the foundation for optofluidic bio-laser sensors.

- 21.Lee W, Fan X. Intracavity DNA Melting Analysis with Optofluidic Lasers. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:9558–9563. doi: 10.1021/ac302416g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Lee W, Fan X. Bio-switchable optofluidic lasers based on DNA Holliday junctions. Lab Chip. 2012;12:3673–3675. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40183e. *Sensitive detection of biomolecule conformational change using the optofluidic bio-laser.

- 23.Chen Q, et al. Highly sensitive fluorescent protein FRET detection using optofluidic lasers. Lab Chip. 2013;13:2679–2681. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50207d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, et al. Optofluidic microcavities: Dye-lasers and biosensors. Biomicrofluidics. 2010;4:043002. doi: 10.1063/1.3499949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nizamoglu S, Gather MC, Yun SH. All-Biomaterial Laser using Vitamin and Biopolymers. Adv. Mater. 2013 doi: 10.1002/adma201300818. DOI: 10.1002/adma201300818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joannopoulos JD, Johnson SG, Winn JN, Meade RD. Photonic Crystals: Molding the Flow of Light. 2nd Edition Princeton University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao H, et al. Random Laser Action in Semiconductor Powder. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999;82:2278–2281. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cerdán L, et al. FRET-assisted laser emission in colloidal suspensions of dye-doped latex nanoparticles. Nature Photon. 2012;6:621–626. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang MH, et al. Room-Temperature Ultraviolet Nanowire Nanolasers. Science. 2001;292:1897–1899. doi: 10.1126/science.1060367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noginov MA, et al. Demonstration of a spaser-based nanolaser. Nature. 2009;460:1110–1113. doi: 10.1038/nature08318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma R-M, Oulton RF, Sorger VJ, Bartal G, Zhang X. Room-temperature sub diffraction-limited plasmon laser by total internal reflection. Nature Mater. 2011;10:110–113. doi: 10.1038/nmat2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho C-H, Aspetti CO, Park J, Agarwal R. Silicon coupled with plasmon nanocavities generates bright visible hot luminescence. Nature Photon. 2013;7:285–289. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2013.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oulton RF, et al. Plasmon lasers at deep subwavelength scale. Nature. 2009;461:629–632. doi: 10.1038/nature08364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horiuchi T, Niwa O, Hatakenaka N. Evidence for laser action driven by electrochemiluminescence. Nature. 1998;394:659–661. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Q, et al. Self-assembled DNA tetrahedral optofluidic lasers with precise and tunable gain control. Lab Chip. 2013;13:3351–3354. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50629k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hell SW. Far-Field Optical Nanoscopy. Science. 2007;316:1153–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.1137395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang MC, Min W, Freudiger CW, Ruvkun G, Xie XS. RNAi screening for fat regulatory genes with SRS microscopy. Nature Methods. 2011;8:135–138. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Min W, et al. Imaging chromophores with undetectable fluorescence by stimulated emission microscopy. Nature. 2009;461:1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/nature08438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang P, et al. Far-field imaging of non-fluorescent species with sub-diffraction resolution. Nature Photon. 2013;7:449–453. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2013.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nadkarni SK, et al. Characterization of Atherosclerotic Plaques by Laser Speckle Imaging. Circulation. 2005;112:885–892. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.520098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mason TG, Weitz DA. Optical Measurements of Frequency-Dependent Linear Viscoelastic Moduli of Complex Fluids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995;74:1250–1253. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siegman AE. Lasers. University Science Books; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matthes R, et al. Revision of guidelines on limits of exposure to laser radiation of wavelengths between 400 nm and 1.4 μm. Health Phys. 2000;79:431–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hänsch TW. Edible Lasers and Other Delights of the 1970s. Opt. Photonics News. 2005 Feb;:14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song W, Vasdekis AE, Li Z, Psaltis D. Optofluidic evanescent dye laser based on a distributed feedback circular grating. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009;94:161110. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qian S-X, Snow JB, Tzeng H-M, Chang RK. Lasing Droplets: Highlighting the Liquid-Air Interface by Laser Emission. Science. 1986;231:486–488. doi: 10.1126/science.231.4737.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moon H-J, Chough Y-T, An K. Cylindrical Microcavity Laser Based on the Evanescent-Wave-Coupled Gain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000;85:3161–3164. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Azzouz H, et al. Levitated droplet dye laser. Opt. Express. 2006;14:4374–4379. doi: 10.1364/oe.14.004374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kiraz A, et al. Lasing from single, stationary, dye-doped glycerol/water microdroplets located on a superhydrophobic surface. Opt. Commun. 2007;276:145–148. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang X, Song Q, Xu L, Fu J, Tong L. Microfiber knot dye laser based on the evanescent-wave-coupled gain. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007;90:233501. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanyeri M, Perron R, Kennedy IM. Lasing droplets in a microfabricated channel. Opt. Lett. 2007;32:2529–2531. doi: 10.1364/ol.32.002529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang SKY, et al. A multi-color fast-switching microfluidic droplet dye laser. Lab Chip. 2009;9:2767–2771. doi: 10.1039/b914066b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schäfer J, et al. Quantum Dot Microdrop Laser. Nano Lett. 2008;8:1709–1712. doi: 10.1021/nl080661a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee W, Luo Y, Zhu Q, Fan X. Versatile optofluidic ring resonator lasers based on microdroplets. Opt. Express. 2011;19:19668–19674. doi: 10.1364/OE.19.019668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang Y, et al. A tunable 3D optofluidic waveguide dye laser via two centrifugal Dean flow streams. Lab Chip. 2011;11:3182–3187. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20435a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aubry G, et al. A multicolor microfluidic droplet dye laser with single mode emission. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011;98:111111. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Christiansen MB, Kristensen A, Xiao S, Mortensen NA. Photonic integration in k-space: Enhancing the performance of photonic crystal dye lasers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008;93:231101. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu X, Chen Q, Sun Y, Fan X. Bio-inspired optofluidic lasers with luciferin. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013;102:203706. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lacey S, et al. Versatile opto-fluidic ring resonator lasers with ultra-low threshold. Opt. Express. 2007;15:17433–17442. doi: 10.1364/oe.15.015523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]