Abstract

Nanotechnology approaches have tremendous potential for enhancing treatment efficacy with lower doses of chemotherapeutics. Nanoparticle-based drug delivery approaches are poorly developed for childhood leukemia. Dexamethasone (Dex) is one of the most common chemotherapeutic drugs used in the treatment of childhood leukemia. In this study, we encapsulated Dex in polymeric nanoparticles and validated their anti-leukemic potential in vitro and in vivo. Nanoparticles (NPs) with an average diameter of 110 nm were assembled from amphiphilic block copolymers poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) and poly (ε-caprolactone) (PCL) bearing pendant cyclic ketals. The blank nanoparticles were non-toxic to cultured cells in vitro and to mice in vivo. Encapsulation of Dex into the nanoparticles (Dex-NP) did not compromise the bioactivity of the drug. Dex-NPs induced glucocorticoid phosphorylation and showed cytotoxicity similar to the free Dex in leukemic cells. Studies using nanoparticles labeled with fluorescent dyes revealed leukemic cell surface binding and internalization. In vivo biodistribution studies showed NP accumulation in the liver and spleen with subsequent clearance of the particles with time. In a pre-clinical model of leukemia, Dex-NPs significantly improved the quality of life and survival of mice compared to the free drug. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing the efficacy of polymeric nanoparticles to deliver Dex to potentially treat childhood leukemia and reveals that low dose of Dex should be sufficient for inducing cell death and improve survival.

Keywords: Nanomedicine, Drug Delivery, Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Dexamethasone, Pre-clinical Model

Introduction

Cancer nanotechnology is an emerging multi-disciplinary field that involves novel and practical application of materials or devices on the nanometer scale while integrating concepts in biology, chemistry, engineering and medicine for early cancer diagnosis and therapy. Unprecedented growth of research in this field has led to significant advances in various biomedical applications; especially in the field of drug delivery. Nanosized drug delivery systems not only enhance the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic properties of anti-cancer agents; but also ensure specific delivery of chemotherapeutic agents to cancer cells.1, 2 The existence of a subtle balance in achieving therapeutic efficacy and reducing deleterious side-effects in any form of therapy raises the need to maintain control over drug release for extended periods of time. Attaining this control is paramount and a key design factor in engineering novel drug delivery systems prior to targeting them. Over the years, numerous nanoscaled drug delivery systems have been formulated and explored for treating cancers. These systems include polymeric nanoparticles and micelles, liposomes, gold nanoshells, dendrimers, quantum dots and fullerenes.2

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common form of pediatric leukemia. It is characterized by malignant proliferation of immature lymphoblasts, curbing the development of healthy blood cells comprising of (i) red blood cells or RBCs that carry oxygen and nutrients throughout the body via the circulatory system; (ii) platelets that prevent excessive bleeding in case of injuries and (iii) white blood cells (WBCs) that are essential for strengthening the body's immune system to fight infections. The proliferation of the malignant cells further leads to massive infiltration of immature lymphoblasts to various sites in the body including the lymphoid system – liver and spleen (hepatosplenomegaly); the bone marrow (joint aches) and the central nervous system. The disease accounts for 76% of all childhood and adolsescent leukemia with incidence rates that peak at the age of 5 years.3 Although chemotherapeutic regimens in combination with radiation therapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation have increased 5-year relative survival rates for children with ALL to 90.5%; leukemia is still the leading cause of cancer-related death in children in the age category 0-14.4, 5 The use of combination chemotherapy to treat and cure leukemia inflicts a severe toll on the child's health in the form of acute or delayed onset of treatment related side-effects that often result in fatality. Although advances in nanotechnology for drug delivery has resulted in pharmaceutical formulations that effectively combat adult cancers,6-8 little research has been performed to develop innovative therapeutic strategies for childhood cancers.

Dexamethasone (Dex), a glucocorticoid class steroid hormone, is widely used as a potent anti-inflammatory and bone growth steroid.9 Dex is also one of the most commonly used chemotherapeutic drugs to treat childhood leukemia.10, 11 It induces apoptosis of B and T lymphocytes and consequently kills a large population of leukemic cells. However, long-term systemic exposure to Dex causes adverse side effects. These include fluid retention, slowed growth, stomach and intestinal bleeding due to ulcers, damage to the joints that can result in pain and loss of motion usually involving the hip and knee (osteoporosis), high blood sugar (Cushing's syndrome), high blood pressure (hypertension), increased pressure in the eyes and most important of all; the body's inability to fight infections due to non-specific killing of normal T and B lymphocytes (immunosuppression). To date the potential of nanocarriers to deliver Dex for ALL has not been explored.

We have previously reported the synthesis of amphiphilic block copolymers consisting of hydrophilic poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) and hydrophobic polyester bearing pendant cyclic ketals via PEG-initiated ring-opening copolymerization of ε-caprolactone (CL) and 1,4,8-trioxaspiro-[4,6]-9-undecanone (TSU) using Sn(Oct)2 as the catalyst.12 The resultant copolymers, referred to as ECTx with x indicating the monomer feed ratio, assembled into nanoparticles (NPs) capable of encapsulating camptothecin (CPT). Particularly, nanoparticles derived from ECT2 (20% (w/w) TSU in monomer feed) offered the best control for CPT release, and the released CPT effectively induced dose-dependent apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Herein we examine and validate ECT2-NPs as a novel biocompatible carrier that can deliver Dex at a controlled rate and induce apoptotic cell death in leukemia cell lines. In this study, we demonstrate that Dex encapsulated ECT2-NPs (Dex-NPs) induce leukemia cell apoptosis in vitro and show enhanced therapeutic efficacy in vivo. The ability to sensitize leukemia cells with this novel system highlights significant therapeutic implications for NPs for the future treatment of childhood leukemia.

Experimental Section

Reagents, Cell Lines and Mouse Models

All chemicals necessary for the synthesis of the amphiphilic copolymers were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO) and were used as received unless otherwise indicated. Dexamethasone for in vitro studies was purchased from Tocris Biosciences (Minneapolis, MN) and clinical grade Dex for in vivo studies was obtained through Nemours-A.I. duPont Hospital for Children's Pharmacy. Nile red was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). DilC18 (7) tricarbocyanine probe (DiR) was acquired from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Cell lines, RS4;11 (established from an ALL patient); Nalm6 (established from a patient with ALL at relapse) and Hela (established from epitheloid cervical carcinoma), were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). RS4;11, Nalm6 cells were maintained in RPMI media (Life Technologies) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Hela cells were maintained in DMEM media (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FBS, glutamine and penicillin/streptomycin. All cells were maintained at 37 °C under a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Whole blood samples were drawn from healthy volunteers into blood collection tubes with heparin in accordance with Institutional Review Board approved protocols. C57BL/6 mice used for in vivo tolerability studies, BALB/c mice used for in vivo pharmacokinetic analysis, and immune-compromised NSG-B2m mice used to develop pre-clinical acute lymphoblastic leukemia mouse models for efficacy studies were all purchased from Jacksonville Laboratories, U.S.A. C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were bred in-house. Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Polymer Synthesis

ECT copolymers were synthesized following a previously reported procedure.12 As determined by 1H NMR (polymers were dissolved in CDCl3 and the spectrum was recorded on a Bruker AV400 NMR spectrometer) and gel permeation chromatography (the system comprised of a Waters 515 pump, a Waters Styragel® HR column and a Waters 2414 refractive index detector and mobile phase; tetrahydrofuran), the resultant copolymer showed a composition of EG113CL497TSU85, a number-average molecular weight (Mn) of 64.2 kg/mol, and polydispersity index (PDI) of 1.39.

Particle Formulation and Drug/Dye Encapsulation

NPs were formulated using a nanoprecipitation method. To a vigorously stirred (900 rpm) aqueous phase (5 ml DI water) was added an acetone solution of ECT (16 mg/ml, 1.4 ml). The mixture was allowed to stabilize overnight under constant agitation at room temperature to obtain blank or ECT2-NPs. Dex- or Nile red-loaded NPs were prepared using an acetone solution of ECT containing 1.8 mg/ml Dex or 0.16 mg/ml Nile red, respectively. Similarly, DiR dye was dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 0.9 mg/ml. The DiR dye solution (100 μl) was then mixed with the ECT solution (16 mg/ml, 1.4 ml) in acetone. The resulting dye/polymer mixtures were used for nanoprecipitation as described above. Centrifugation (4,000 rpm for 10 min) was applied to all types of NP suspension to remove large aggregates formed from the polymer. The supernatant containing NPs was collected and then additional centrifugation was performed (14,000 rpm for 10 min) to spin down the NPs. Subsequently, NPs were thoroughly washed with PBS for three times by centrifugation and immediately used for the characterization and biological studies.

Characterization of NPs

The hydrodynamic diameters of ECT2- and Dex-NPs were measured using the Zetasizer nanoZS (Malvern Instruments) via dynamic light scattering (DLS). Z-average particle size and size distribution were analyzed by using Malvern's DTS software (v.5.02). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used for the morphological examination of the NPs. TEM samples were prepared by applying a drop of NP suspension (3 μl) directly onto a carbon-coated copper TEM grid. Samples were allowed to dry under ambient condition prior to imaging using a Tecnai G2 12 Twin TEM (FEI Company).

Drug/Dye Loading and Release

Aliquots (1 ml each) of the Dex-NP, Nile red-NP and DiR-NP suspension were collected and lyophilized. The dried powder was weighed accurately before being dissolved in DMSO (1 ml). The drug/dye concentration was determined using a UV-Vis spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, King of Prussia, PA) at 254 nm (Dex), 520 nm (Nile red) and 750 nm (DiR). Drug loading content was defined as the amount of drug (μg) loaded per milligram of Dex-NPs. Drug encapsulation efficiency (EE, as percentage of the total) was calculated by dividing the amount of Dex loaded into the NPs with the amount of Dex initially added during the nanoprecipitation process. All measurements were carried out in triplicate and the results were indicated as the mean ± SD.

The in vitro release behaviors of Dex, Nile red and DiR were analyzed under sink conditions following a previous method.12 Briefly, freshly formulated NP suspensions were loaded into hydrated dialysis cassettes with a molecular weight cut-off of 10,000 Da. The cassettes were subsequently immersed in the release media (100 ml PBS) under gentle stirring. At predetermined time points, 10 ml of the release media was collected and 10 ml fresh PBS was replenished to maintain a constant volume (100 ml). Media containing the released Dex or dyes collected from each time point was lyophilized and the resultant solid was re-dissolved in DMSO. Subsequently, the concentrations of Dex or the dyes were determined by UV-Vis. Three repeats were performed for each time point and the cumulative release profile was calculated by dividing the amount of drug or dyes released in one specific measurement time by the total mass initially loaded.

In Vitro Toxicity

The toxicity of ECT2-NPs was tested in two ALL cell lines (RS4; 11 and Nalm6) and an epitheloid carcinoma cell line (Hela). The leukemia cells were seeded at 50,000 cells per well and Hela cells were seeded at 5,000 cells per well in 100 μl of cell culture media containing ECT2-NPs at a dosage ranging from 0.07 μg/ml to 70 μg/ml (1 to 1000 fold), corresponding to 10 nM to 10 μM Dex equivalents encapsulated within Dex-NPs, in 96-well cell culture plates. The plates were then incubated for 72 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. At the end of incubation, cell viability was measured by Cell Titer-Blue® Assay (Promega, Madison, WI) following manufacturer's instruction. The fluorescence measurements were recorded on a micro plate reader (Perkin Elmer Victor™, USA). Assays were repeated to obtain an average of 6 replicates and the data were expressed as the percentage of viable cells compared to the survival of a control group (untreated cells to define maximum cell viability).

Hemolytic Activity and in Vivo Tolerability

Hemolytic properties were evaluated by incubating ECT2-NPs at varying concentrations (0.1, 1, 2.5 mg/ml) for 240 min at 37 °C with human heparinized whole blood samples drawn from three different subjects. Blood samples treated with 1 % Triton X-100 and PBS were included as positive and negative controls, respectively. Sample tubes were gently inverted every 30 min during the incubation period, after which the tubes were centrifuged at 800 g for 15 min at room temperature to remove unlysed RBCs. The supernatants obtained were then mixed with a cyanmethemoglobin reagent and analyzed at 540 nm with a micro plate reader to quantify the hemoglobin concentration. The percentage hemolysis was then determined by calculating ratio of the relative absorbance of samples and Triton X-100 with respect to PBS.13

For in vivo toxicity evaluation of ECT2-NPs, NPs (100 μl of 0.5, 5 and 50 mg/kg of NPs in PBS) were intravenously injected to C57BL/6 mice (3/group) twice a week for 1 month. All mice were evaluated twice weekly for eight weeks post-treatment for clinical symptoms of toxicity. To monitor change in body weights of mice in all treatment groups, the ratio of values recorded each week to the pre-treatment values were calculated and compared with the ratios obtained for the group that received the vehicle (control).

Dexamethasone Bioactivity Assay

The bioactivity of the encapsulated Dex was analyzed by treating RS4;11 cells seeded at 50,000 cells per well and Hela cells at 5,000 cells per well in 100 μl of cell culture media composed of Dex-NPs at multiple doses (1-1000 fold) that correspond to 10 nM to 10 μM of Dex equivalents encapsulated within NPs in 96-well cell culture plates. The plates were incubated for 72 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere and cell viability was subsequently analyzed by Cell Titer-Blue® Assay as described in in vitro toxicity assay.

Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Dex-NPs

The cytotoxic effect of Dex-NPs or Dex in free form was tested and compared between ALL cell lines RS4;11 and Nalm6. The cells were seeded at an initial density of 50,000 cells per well in 100 μl of cell culture media constituted with Dex-NPs or free Dex at increasing doses ranging from 1 to 107 fold (1 pM to 10 μM Dex equivalents). The assays were performed in 96-well cell culture plates which were maintained at 37 °C in 5 % CO2 atmosphere for 24 h, 48 h, 72 h and 96 h. At the end of each incubation point; cell viability was measured by Cell Titer-Blue® Assay. The measurements were then expressed as the percentage of viable cells compared to the survival of respective control groups (untreated cells for Dex-NP and 0.01% DMSO treated cells for Dex in free form) defined as the maximum cell viability. The data obtained was further analyzed using Prism nonlinear regression software (Graphpad Software) for the curve-fitting and determination of IC50 values.

Evaluation of Apoptosis

RS4;11 cells were plated in 10 cm dishes at a density of 5 × 106 cells/dish and were incubated with Dex-NPs at dosages ranging from 1 pM to 10 μM Dex equivalents encapsulated within NPs for 48 h. Leukemia cells treated with 0.01% DMSO or 10 μM Dex in free form were considered as negative and positive experimental controls respectively. Post incubation, cells were collected, washed with cold PBS twice and centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 5 min. The cell pellets were resuspended in a lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 150 mM NaCl; 1 mM EDTA; 1 mM EGTA; 1 mM β-Glycerol Phosphate; 1 mM Sodium Vanadate; 1.25 mM Sodium Pyrophosphate; 1% (w/v) Triton X-100) with a 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (100 mM Phenylmethylsulfonyl Fluoride, 1:100; 15 mg/ml mixture of Antipain, Leupeptin, Pepstatin, 1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich. St Louis, MO) at 4 °C for 30 min. The cell lysates were then prepared from the homogenates by sonication and centrifugation at 12,000 rpm and 4 °C for 15 min. The protein concentration in the lysates was determined using a protein assay kit (DC protein assay reagent, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Equal amounts of protein (90 μg) were resolved on 15 % SDS-PAGE gels and transferred overnight onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) in 20 % methanol, 25 mM Tris, and 192 mM glycine. After transfer, the membranes were blotted with a rabbit polyclonal against active + pro caspase-3 antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) and a mouse monoclonal antibody against actin (1:10000, Cell Signaling) and visualized by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and Enhanced Chemiluminescence Plus reagent (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) followed by exposure to X-ray film (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Measurement of Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR) Phosphorylation

ALL cell lines RS4;11 and Nalm6 were plated in 10 cm dishes at an initial seeding density of 5 × 106 cells/dish with RPMI media containing 20% charcoal-stripped FBS. Cells were then incubated with Dex-NPs and free Dex at a concentration corresponding to 10 μM Dex encapsulated within NPs for 0.08, 0.25. 0.5, 1, 2 and 6 h. Cells treated with 0.01% DMSO was considered as the experimental control. The cell lysates were prepared and protein concentrations were estimated as described earlier. Equal amounts of protein (45 μg) were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred overnight onto nitrocellulose membranes and blotted with a rabbit polyclonal to phospho-GR antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling, MA) as explained above.

Determination of Cellular Uptake of ECT2-NPs

NPs containing encapsulated Nile red (485Ex/525Em) (NR-NPs) were used to determine cellular uptake of NPs. For flow cytometry (FCM) and confocal laser scanning microscopy analysis (CLSM), 1×106 RS4;11 and Nalm6 cells/ml were seeded in 12 well plates and incubated in the presence or absence of NR-NPs (final concentration 70.1 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 6 h. Cells were then washed three times with cold PBS and subjected to FCM analysis with BD Acuri C6 Flow Cytometer® System. Thereafter, the Nile-red fluorescence emitted by the particles bound or internalized by the leukemia cells was analyzed in the FL-1 channel at a wavelength of 530 nm and the data were generated using BD Accuri CFlow® software. To visualize cellular uptake of NPs, the NP treated cells were washed three times with cold PBS and transferred to Poly Prep Slides™ (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). Cells were then fixed for 5 min with 2% paraformaldehyde solution and embedded in ProLong Antifade Kit® mounting medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Images were acquired by sequential scanning using a Leica TCS SP5 laser-scanning confocal microscope and processed by merging of the fluorescence channels using the software LSM (Leica Microsystems, Mannhein, Germany).

In Vivo Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution

To investigate biodistribution and clearance rates of ECT2-NPs, female BALB/c mice (4-6 weeks of age; 3 per group) received intravenous injections of 100 μl of DiR-NPs (0.2 mg/kg DiR). Subsequently, liver, spleen, heart, lung, kidney, intestine, gonads, bladder and brain were dissected out after euthanizing the mice at 2 h, 15 h, 24 h, 48 h, 96 h, 1 week, 2 weeks and a month post administration for subsequent ex vivo imaging using Carestream Multi-spectral in vivo Imaging System. Additionally, the organs were lysed in tissue lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCL, pH 7.5; 150 mM Sodium Chloride; 1 mM EDTA; 1 mM EGTA; 1 mM β-Glycerol Phosphate; 1 mM Sodium Vanadate; 2.5 mM Sodium Pyrophosphate; 1% (w/v) Triton X-100; 1% (w/v) IGEPAL; 0.5 % (w/v) Deooxycholate; 1 % (w/v) SDS) and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (100 mM Phenylmethylsulfonyl Fluoride, 1:100; 15 mg/ml mixture of Antipain, Leupeptin, Pepstatin, 1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) at 4 °C for 1 h. The lysates were used to quantify the DiR-NP fluorescence levels in various organs using the imaging software and the NP levels were estimated by comparing with standards prepared in tissue lysis buffer. BALB/c mice treated with saline were included as controls for the experiment and to establish imaging settings based on background fluorescence for each measurement.

For analyzing plasma pharmacokinetics; a lipophilic “far-red” dye DiR (750Ex/830Em) was encapsulated in ECT2-NPs (DiR-NPs). A cohort of female BALB/c mice (4-6 weeks of age; 3/group) was injected via the tail vein with a single dose of 100 μl of DiR-NPs (0.2 mg/kg DiR) resuspended in PBS. At 0, 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 6, 8 and 12 h after nanoparticle injection, peripheral blood was collected from the mice by submandibular bleeding in tubes containing 20 μl of sodium citrate to prevent blood from clogging. Blood was then centrifuged and plasma was analyzed by multi-label microplate reader (Plate Chameleon V, Hidex, Finland) to assess the plasma half-life of DiR-NPs. The NP levels were then estimated by comparing with standards prepared in plasma.

In Vivo Antitumor Efficacy

RS4; 11 cells (5×106) were injected via the tail vein into female NSG-B2m mice (6 - 8 weeks old; 7 per group). Weekly submandibular bleeding was used to monitor disease progression, calculating the percentage of human cells in mouse peripheral blood by flow cytometry using FITC-conjugated anti-human CD45 and APC-conjugated anti-mouse CD45. Two weeks after leukemia cell injection, the mice received intravenous treatments of saline, free Dex, or Dex-NPs suspended in saline at Dex equivalents of 5 mg/kg every other day for 4 weeks. The treatment efficacy was determined using Kaplan-Meier curves, sacrificing animals when they depicted signs of morbidity, including hind-limb paralysis or excessive weight loss, according to IACUC guidelines.

Statistical Analysis

All data are indicated as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. The IC50 values were compared by the student's t-test. Survival data were presented using Kaplan–Meier plots and were analyzed using “Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) Test“. A p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

NP Formulation and Characterization

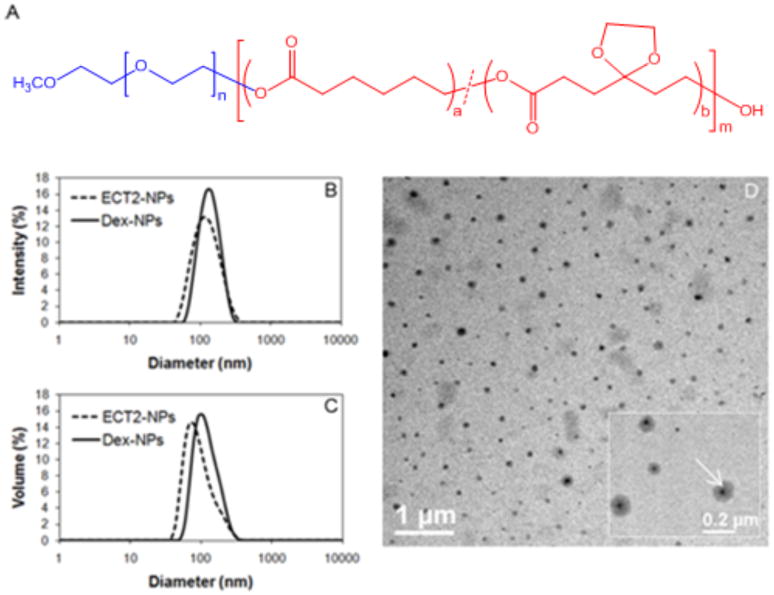

Amphiphilic block copolymers containing a hydrophilic PEG block and a hydrophobic PCL block randomly decorated with cyclic ketals were synthesized by ring opening polymerization of CL and TSU using mPEG as the initiator (Figure 1A).12 ECT2 with 14 mol% TSU in the hydrophobic block and an average molecular weight of 62 kDa was used for Dex encapsulation. Blank or ECT2-NPs and Dex-loaded NPs were prepared using the acetone/water system. Particle size analysis by DLS (Figure 1) showed that the ECT2-NPs exhibited an intensity-average size of 111 ± 4 nm (Figure 1B) and a volume-average size of 98 ± 3 nm (Figure 1C). Dex encapsulation increased the average size to 127 ± 1 nm (Figure 1B) and 124 ± 2 nm (Figure 1C) by intensity and by volume, respectively. The average size from intensity and volume were in agreement with each other for both ECT2-NPs and Dex-NPs, and reflected the size of the major nanoparticle population. In addition, NPs exhibited a narrow size distribution as shown by the low PDI values of 0.14 and 0.05 for ECT2-NPs and Dex-NPs, respectively. Inspection of Dex-NPs by TEM revealed the presence of spherical nanoparticles with an estimated diameter of 110 nm (Figure 1D), in good agreement with the measured size by DLS (Figure 1B, 1C). Higher magnification image (Figure 1D, insert) revealed the presence of a dense core (arrow) and a diffuse corona for Dex-loaded NPs, confirming the successful entrapment of Dex in the interior of the NPs. Nile red and DiR-labeled NPs showed similar size distributions as Dex-NPs (data not shown). All three types of NPs were stable upon dilution and prolonged incubation (up to 4.5 months) under experimental conditions employed in the study.

Figure 1.

(A) Chemical structure of ECTx copolymer consisting of a hydrophilic PEG block and a hydrophobic PCL segment carrying randomly distributed cyclic ketals. Analysis of particle size (B, C) and morphology (D). DLS analysis of ECT2-NPs (dash line) and Dex-NPs (solid line) - (B) intensity-based size distribution and (C) volume-based size-distribution. (D) Transmission electron micrograph of Dex-NPs formulated through nanoprecipitation. (D, insert) – TEM at a higher magnification. Note the dense core (arrow) showing the entrapment of the Dex.

Drug/Dye Loading and Release

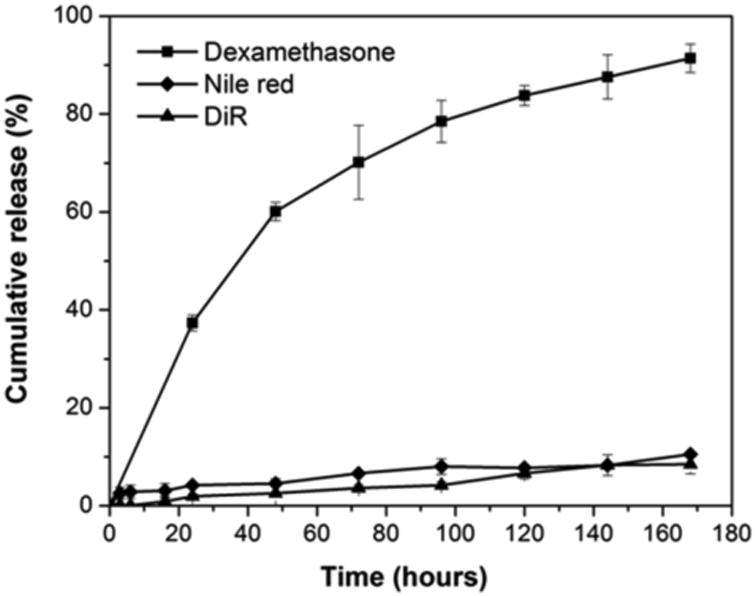

Dex was effectively entrapped in ECT2-NPs with a loading content and encapsulation efficiency of 58.4 ± 5 (μg/mg) and 52.6 ± 4%, respectively. Comparable values were obtained by other studies using amphiphilic polymers as carriers for hydrophobic drugs.14, 15 In vitro release was evaluated by incubating Dex-NPs in PBS under sink conditions at ambient temperature for up to 7 days. The release profile shown in Figure 2 revealed that 60.1 ± 1.9 wt% of the initially loaded Dex was released during the first two days, followed by a slower release with an average rate of 17.2 wt% and 14.1 wt% from day 2 to day 4 and day 4 to day 7, respectively. By day 7, 91.4 ± 2.9 wt% of the initially loaded Dex was released. Separately, in vitro release of Nile red and DiR loaded NPs were also performed (Figure 2). The loading content for Nile red and DiR were estimated as 7.9 ± 1.2 and 3.1 ± 0.4 μg/mg respectively, with the encapsulation efficiency as 78.8 ± 12.3% and 79.5 ± 10% for the corresponding dye loaded NPs. Only 2.8 ± 1.3 wt% and 0.5 ± 0.1 wt% of hydrophobic dyes were released after the first 6 h for Nile red and DiR respectively. By day 7 when the experiment was terminated, a total cumulative release of 10.5 ± 0.5 wt% and 8.5 ± 2.0 wt% were detected for Nile red and DiR respectively. This limited release has been attributed to the strong hydrophobicity of these dyes.16, 17 The high retention of hydrophobic fluorescent probes by NPs demonstrates the feasibility to use Nile red and DiR to track the fate of NPs within cellular environments without undesirable premature leaking.

Figure 2.

In vitro release profiles of Dex (square), Nile red (diamond) and DiR (triangle) from nanoparticles in PBS (pH 7.4) at ambient temperature. Data shown is average of three independent experiments.

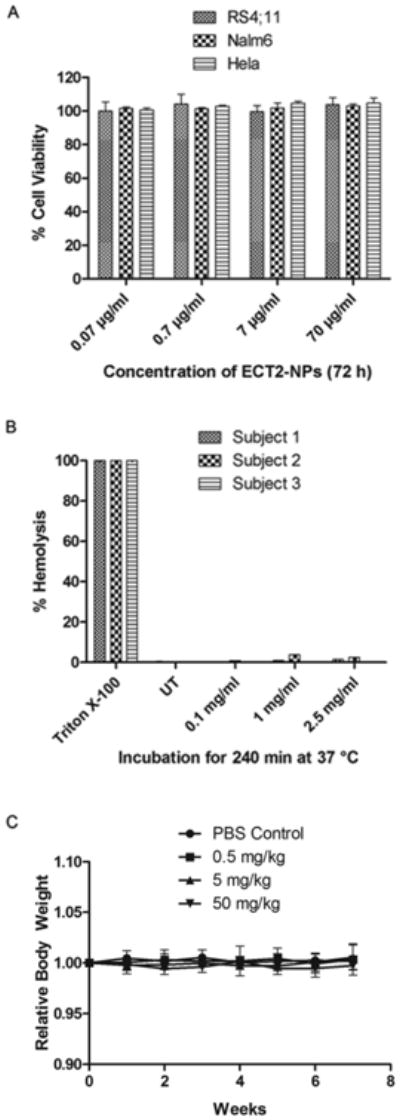

ECT2-NPs are Non-toxic in Vitro and in Vivo

Three different test platforms including cultured cells, human blood, and live animals were utilized to confirm the biocompatibility of ECT2-NPs. Two leukemia (RS4; 11, Nalm6) and one carcinoma (Hela) cell lines were used to test the biocompatibility of ECT2-NPs. As depicted in Figure 3A, cell viability remained unaffected in the presence of ECT2-NPs at concentrations ranging from 0.07 to 70 μg/ml, demonstrating their non-toxic nature towards leukemia cells and the adherent epithelial cancer cells. In vitro hemolytic evaluation was carried out by incubating ECT2-NPs with human whole blood samples drawn from three different individuals. Contrary to Triton X-100 (positive control), ECT2-NPs did not induce any hemolysis at concentrations of 0.1, 1.0 and 2.5 mg/ml (Figure 3B). In addition, the in vivo biocompatibility of ECT2-NPs was examined by monitoring changes of body weight or behavioral patterns in mice during the treatment. The body weight ratios remained stable and normal eating, drinking, grooming and physical activities continued throughout the duration of treatment and for 3 weeks post treatment (Figure 3C). The mice did not exhibit any symptoms of pain or hematuria and no damage was observed at the injection sites on lateral tail veins due to the intravenous dosing of NPs. These observations confirm ECT2-NPs as a biocompatible carrier for therapeutic agents.

Figure 3.

ECT2-NPs are non-toxic to cultured cells, human blood and mice. (A) Effect of ECT2-NPs on the viability of leukemia and carcinoma cell lines. (B) In vitro hemolytic analysis of ECT2-NPs on human blood. ECT2-NPs do not induce hemolysis in contact with human blood. (C) In vivo biocompatibility of ECT2-NPs in C57BL/6 mice (3 per group). Absence of changes in relative body weight of mice validates the safety of ECT-NPs.

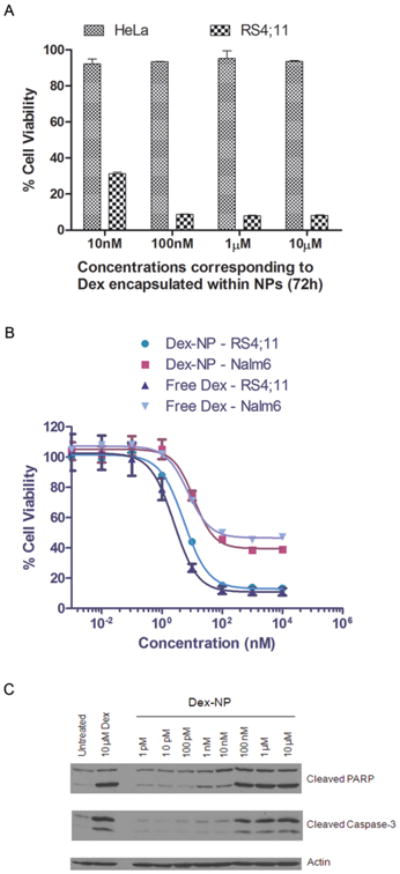

Dex-NPs Deliver Bioactive Dexamethasone and Induce Apoptosis in Leukemia Cells

RS4; 11 cells are highly sensitive to Dex while HeLa cells are not.18, 19 As expected, close to 100% viability was observed from Dex-NP-treated HeLa cells at equivalent Dex concentrations of 10 nM to 10 μM (Figure 4). By contrast, RS4;11 cells showed 10-30% viability after 72 h of Dex-NP treatment at the same concentration range. Interestingly, 100 nM of Dex-NPs caused close to 90% cell death and further increase in NP dosage (1 μM and 10 nM) did not induce a significant change in cell viability (Figure 4A). Dose-dependent cytotoxicity studies with free Dex or Dex-NPs on RS4;11 and Nalm6 revealed a similar pharmacological activity (Figure 4B). The IC50 values [(a) 1.7 nM (free Dex) and 2.4 nM (Dex-NP) for RS4;11, P = 0.16 and (b) 6.7 nM (free Dex) and 5.08 nM (Dex-NP) for Nalm6, P = 0.6] were not significantly different between either form of treatment in both cell lines. It is well established that Dex induces cell death in leukemic cells by apoptosis.20 Dex-NPs induced dose-dependent cleavage of caspase-3 protein and its substrate PARP (Figure 4C), indicating apoptotic cell death. Taken together, our results validate that ECT2-NPs deliver bioactive Dex and induce cytotoxicity in leukemia cells.

Figure 4.

Dex-NPs induce Cytotoxicity in leukemia cells. (A) Bioactivity of Dex is retained post encapsulation. Hela cells are insensitive to Dex and RS4;11 leukemia cells are sensitive to Dex. (B) Dose-response curves of free Dex and Dex-NPs at 48 h. (C) Cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3 levels confirm Dex-NP induced apoptosis in RS4;11 cells at 48 h. Data shown in ‘A’ and ‘B’ are the means of hexaplicates plus or minus SD. ‘C’ is a representative blot from 1 of 4 independent experiments.

ECT2-NPs are Bound to and Internalized by Leukemia Cells

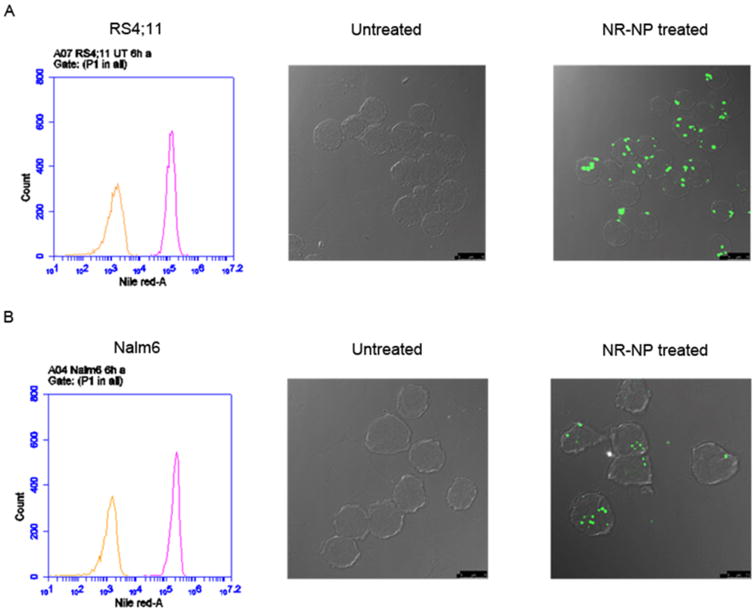

To investigate the potential of ECT2-NPs as drug carriers, cellular binding and uptake studies were performed on two leukemia cell lines (RS4;11, Nalm6) using NR-NPs at a concentration of 70.1 μg/ml. The shift in fluorescence peak from the untreated group (orange trace) to the treated samples (pink trace) in the FCM plot (Figure 5) confirms the binding of NR-NPs to leukemia cells. Further, CLSM revealed NR-NPs internalized and localized within RS4;11 and Nalm6 cells after 6 h post-treatment at 37 °C (Figure. 5A and 5B). Time course experiments further revealed that ECT2-NP binding to the cell surface was detected as early as 15 min. However at this time point there was negligible amount of internalization (data not shown).

Figure 5.

NR-NPs bind and internalize by non-specific uptake. Flow cytometry analysis of leukemia cells RS4;11 (A; upper left) and Nalm6 (B; lower left) depict untreated (orange trace) and cell-surface binding of NR-NPs at 6 h (pink trace). CLSM images of leukemia cells RS4;11 (A) and Nalm6 (B) represent untreated (middle) and NR-NP treated (right) in 6 h. Scale Bar: 10 μm

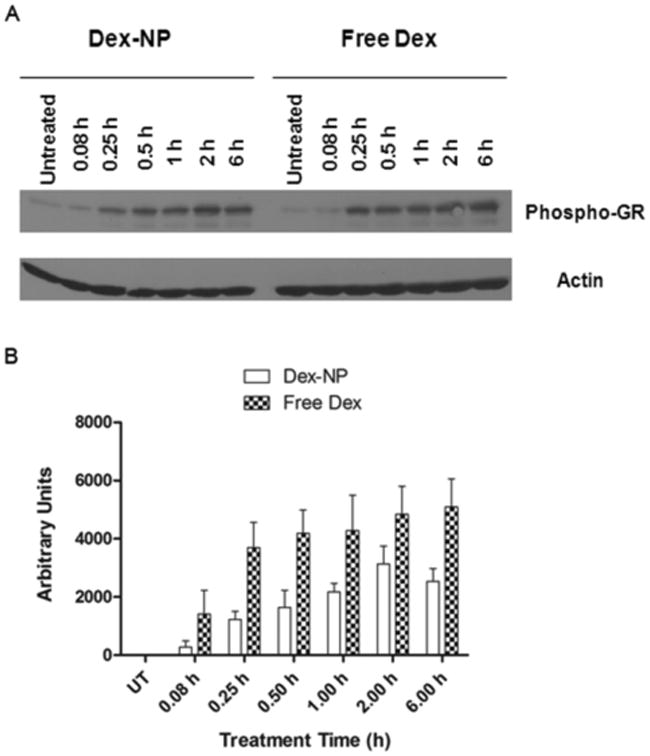

ECT2-NPs Deliver Dexamethasone to Leukemia Cells at Sustained Rates

Binding of Dex to the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) induces its phosphorylation, subsequently leading to cell apoptosis.21 Therefore, release of Dex from the NPs within the cells could be monitored by the extent of phosphorylation of GR. On the other hand, treatment of cells with free Dex is likely to induce higher levels of GR phosphorylation instantly. Thus, GR phosphorylation was used to gauge the intracellular functionality of Dex. RS4;11 cells were incubated with either 10 μM of free Dex or equivalent amounts of Dex encapsulated within the ECT2-NPs or Dex-NPs (70.1 μg/ml) for 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 6 h. Quantification of the blots revealed higher GR phosphorylation levels within 0.08 h (15 min) and it remained high for 6 h in cells treated with free Dex. By contrast, in Dex-NP treated cells GR phosphorylation levels increased gradually over the first two hours and by 6 h were only 50% of the free Dex treated cells (Figure 6A and B). This result suggests that a slow and sustained release of Dex occurs when it is encapsulated in NPs.

Figure 6.

Dex-NPs act as sustained-release formulations when treated with leukemia cells in vitro. (A) A representative immunoblot depicting GR phosphorylation levels in RS4;11 leukemia cells treated with Dex-NPs corresponding to 10 μM of drug encapsulated within or 10 μM of free Dex. (B) Quantified GR phosphorylation levels in RS4;11 cells highlight Dex-NPs as sustained-release formulations in vitro from three independent experiments.

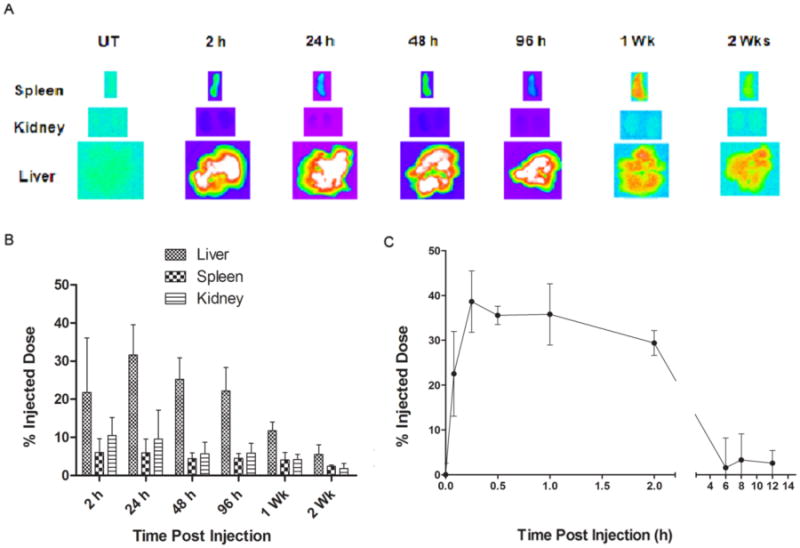

ECT2-NPs undergo Bioditribution and Clearance in Mice

To assess tissue distribution levels, BALB/c mice injected via the tail vein with DiR-NPs (0.2 mg/kg DiR) were euthanized at multiple time points to harvest liver, spleen, heart, lung, kidneys, intestine, gonads, bladder and brain. The ex vivo imaging of harvested tissues revealed maximum NP accumulation in liver and spleen, reduced levels in kidneys and no accumulation in other organs. The DiR-NP fluorescence levels detected in the liver, spleen and kidneys reduced one week later, decreased further in two weeks and cleared almost completely a month later (Figure 7A). The signals detected in the images correlated with DiR-NP levels extracted from tissue lysates (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

ECT2-NPs undergo bioditribution and subsequent clearance in mice. Balb/c mice (3 per group) were intravenously injected with DiR-NPs (0.2 mg/kg DiR). Subsequently, DiR-NP levels were monitored (A) by ex vivo imaging of spleen, kidney and liver. (B) DiR-NP levels in tissue lysates reveal in vivo biodistribution and clearance. (C) DiR-NP levels in blood plasma.

In order to evaluate plasma levels of DiR-NPs, peripheral blood samples drawn from mice at various time points were assessed for “DiR” fluorescence levels. As revealed in Figure 7C, there was an initial spike of DiR-NPs which sustained circulation in the blood plasma for at least 2 h and then reduced at 6 h post injection indicating biodistribution of DiR-NPs to various tissues from blood or clearance from the system. Overall, the results indicate time-dependent clearance of ECT2-NPs.

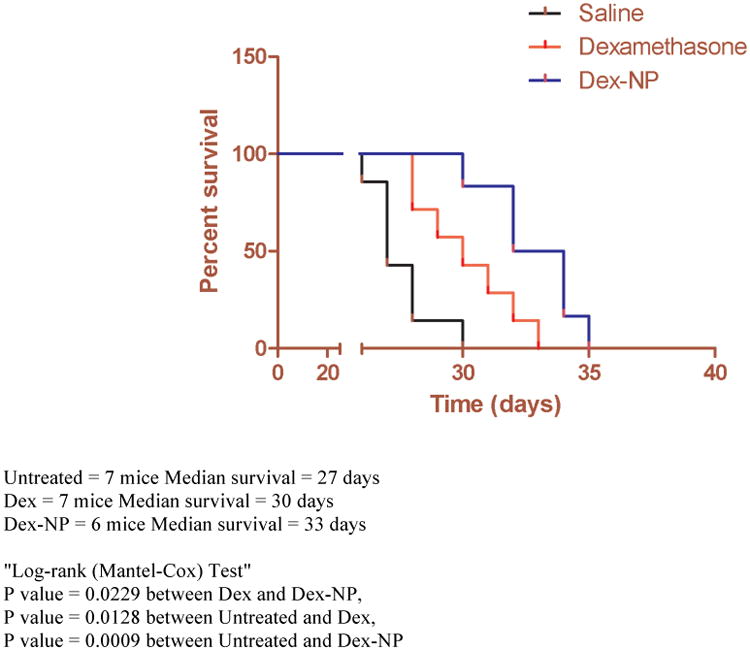

Dex-NPs Enhance Therapeutic Efficacy in a Pre-clinical ALL Mouse Model

To confirm the in vivo efficacy of Dex-NPs, ALL human xenograft models, developed in NSG-B2m mice, received intravenous injections at 5 mg/kg every other day for 4 consecutive weeks. The dose administered is one-third the usual recommended daily dose for controlling leukemia progression in pre-clinical models of mice described previously.22, 23 Following injection of RS4;11 leukemia cells, treatment was initiated after the successful engraftment, as determined by the percentage (>1%) of human cells detected in mouse blood.24 Mice were randomized into three groups (7/group) to receive saline, clinical grade Dex in free form or Dex-NPs. Kaplan-Meier survival curves show that mice that received intravenous administrations of Dex-NPs survived longer (Median Survival = 33 days) than those treated with saline (Median Survival = 27 days P = 0.0009) or the group treated with free Dex (Median Survival = 30 days, P = 0.0229) (Figure 8). Moreover, the group that received Dex-NPs manifested no disease symptoms and were active until the beginning of the 5th week whereas mice treated with free Dex depicted symptoms in 3.5 weeks and were lethargic during the treatment (Supporting Information: Figure A video insert).

Figure 8.

Dex-NPs enhance therapeutic efficacy and prolongs survival in pre-clinical leukemia mouse models: Efficacy of Dex-NPs in xenograft model of ALL. (Survival rate is presented in a Kaplan-Meier plot). Dex-NPs (5 mg/kg Dex) significantly prolonged survival in comparison with groups treated with saline and free Dex (5 mg/kg). This highlights the therapeutic efficacy of ECT based Dex-NP formulations in vivo.

Discussion

Dex is widely used as an anti-inflammatory and bone growth steroid. Drug delivery systems that promote osteoblast growth and enhance local treatment of arthropathies have been formulated.25, 26 Dex loaded polymeric implants or NPs have demonstrated tolerance for extended and controlled intravitreal release in vitro and in vivo.27, 28 In addition, Dexamethasone-eluting stents have been used in clinical trials for treating angina.29, 30 To date the potential of using nanocarriers to deliver Dex for ALL has not been explored.

We successfully prepared Dex-loaded NPs from amphiphilic block copolymers via a nanoprecipitation approach. Our results show that ECT2-NPs are not toxic in vitro or in vivo. Dex-NPs induce dose-dependent cytotoxicity by apoptosis and act as a controlled release formulation for Dex. The efficacy of these novel nanoparticle-based formulations in inducing cytotoxicity is confirmed by both in vitro studies with cell lines and in vivo studies in a pre-clinical leukemia mouse model. Dex-NPs were significantly more toxic than free Dex in vivo. Overall, these results demonstrate the suitability and promising potential of ECT2-NPs for delivery of Dex for acute lymphoblastic leukemia therapy.

Preclinical models using subcutaneous xenografts have contributed significantly to nanomedicine.31, 32 Although subcutaneous models are easy to create and evaluate tumor progression in response to a treatment, this approach does not reflect the in vivo situation viz all tumors are not subcutaneous. The ALL pre-clinical model used in this study accurately mimics the in vivo disease condition where the malignant cells are in the blood and are directly accessed by the intravenously administered therapeutics. This situation closely resembles the treatment received by the ALL patients in the clinic and suggests that this pre-clinical model will be a valuable tool in the evaluation of nanotherapeutics for hematological malignancies.

Owing to their biocompatibility and biodegradability, PCL-based polymeric nanoparticles have been widely used for the delivery and controlled release of anti-cancer drugs.33-36 The incorporation of a cyclic ketal group to the hydrophobic portion of the polymer backbone did not compromise the non-toxic nature of PCL, but allowed us to enhance the chain flexibility while decreasing the polymer crystallinity, offering the opportunity to fine-tune the drug release profile.12 Our NPs which varied in size from 100-120 nm were taken up by leukemia cells in vitro and produced a better outcome in leukemic mice. The loading efficiency of Dex in ECT2-NPs was comparable to previously reported values for polymeric nanoparticles.37 Although the incorporation of pendant cyclic ketals reduced the crystallinity of PCL,12 the low affinity of polymer for Dex may have compromised the overall drug loading. Future modification and adjustment of the polymer composition should allow increased loading and controlled release of Dex in vitro and in vivo.

In B-cell lymphoma, IC50s of the non-targeted liposomal formulations of Doxorubicin were higher than the free drug.38 This may be expected because there would be a time delay due to nonspecific cellular uptake and subsequent release of the drug from liposomes compared to simple diffusion of the free drug. Although there appears to be a small difference in IC50 values for free and encapsulated Dex, the changes were not significant. Our results are consistent with a notion that there is a time delay to initiate events leading to apoptosis in Dex treated cells and that this time delay is similar irrespective of the type of treatment. Since IC50 values are dependent on toxicity of the drug and cell viability which is the endpoint, a time delay in inducing cytotoxicity is a critical factor in justifying the lack of significant differences in the IC50 values between free and encapsulated Dex formulations.

The in vitro Dex release data in Figure 2 show that approximately 60% of the encapsulated drug was released by 48 h when measured at 25°C. Since Dex is susceptible to degradation (∼6% in 7 days) at 37°C, the release kinetics of Dex-NPs was accurately determined at room temperature39. We acknowledge that drug release kinetics at 25°C does not reflect actual in vivo conditions at 37°C where the rate of release tends to be faster. However, reduced and steady levels of Dex induced GR phosphorylation for prolonged periods (∼24h; data not shown) in leukemic cells treated with Dex-NPs in vitro indicates sustained release capabilities of ECT2-NPs. Although we cannot directly measure release of Dex from NPs within the cells, the lower levels of GR phosphorylation indicate that the effective intracellular dose of Dex may be lower in Dex-NP treated cells compared with free Dex treated cells. However, at 48 h, cell death was not significantly different between the two treatments. Thus there was not a significant correlation between GR phosphorylation and cell death.

Leukemic cells treated with free NR revealed intense continuous intracellular staining (Supporting Information: Figure B) compared to distinct punctuate staining observed in the NR-NP treated cells. This depicts that the fluorescence observed is primarily from the NR-NPs internalized by the leukemic cells and not due to premature and undesirable NR release.

Dex clearance rates in children with ALL are highly variable and dependent on co-administered drugs, age and treatment intensity.40 This variable clearance raises the need for repetitive drug dosing that can lead to overdosing and harmful side-effects. Non-targeted NPs typically accumulate rapidly in the liver (first pass metabolism) and spleen, often preventing them from reaching target organs.41 Our data corroborate these prior studies, showing that liver and spleen are the major organs that accumulate our NPs. This may be an advantage in the treatment of ALL because leukemic blasts accumulate and proliferate in these tissues resulting in hepatosplenomegaly (a symptom in pediatric ALL). It takes more than two weeks for our NPs to be eliminated from these tissues, indicating that non-targeted Dex-NPs are potentially valuable as a novel chemotherapy for ALL. In addition, reduced NP accumulation in organs of active filtration such as lungs and kidneys indicate that encapsulated Dex may have a longer elimination half-life than Dex administered as the free active form.

ALL being a liquid tumor, passive targeting by enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect is not relevant. The absence of targeting ligands on Dex-NPs does not permit active targeting as well. This significantly limits the rate of leukemic cell uptake in vivo despite being in systemic circulation. The short half-life of Dex in ALL patients entails the daily administration of high doses of the drug in actual clinical settings. By encapsulating Dex within ECT2-NPs, we may have increased the drug's half-life marginally though not to an extent that could improve the outcome in terms of reducing the dosage frequency.

In our study we used Dex concentrations that are only one-third of the recommended mouse therapeutic dose (5 mg/kg). Although the dose used was not able to affect a cure in the mice, it is quite remarkable that NP encapsulation significantly enhanced efficacy of Dex, delaying onset of disease symptoms and increasing survival time. Similar increases in efficacy of drug encapsulated in non-targeted liposomes or NPs have been noted for other cancers, 38, 42 but not in leukemia. ALL is treated at various stages with a combination of at least six drugs including Dex. Such a regimen is necessary for attaining full remission of the cancer in patients with treatable disease. The fact that reduced dose of Dex alone has improved the quality and survival significantly than the control is the key discovery of this study and justifies the potential of this platform for further development.

Our results indicate that Dex encapsulated in nanoparticles may enable the use of reduced doses of Dex to induce leukemia cell death and improve survival. The next step is to establish targeted drug delivery platforms with this novel system. The ECT-NP surface can easily be modified to covalently link targeting moieties. Several targeting moieties directed against folate43, 44, CD1945, 46, CD1047, 48 or transferrin receptors49, 50 have been utilized for specific targeting of hematological malignancies. Studies that test the effectiveness of such NPs to target ALL specifically and control disease progression with prolonged survival are currently underway. Translation of this technology into the clinic could reduce treatment related side-effects in children treated for cancer.

Supplementary Material

Figure A. Delayed onset of disease symptoms in pre-clinical mouse models of ALL treated with Dex-NPs. (Video link below).

The pre-clinical models of ALL seen in the video are representatives of the three treatment groups. Each group received 100 μl of Dex-NP (5 mg/kg) or free Dex (5 mg/kg) or saline every alternate day throughout the study until they were euthanized on displaying signs of morbidity, including hind-limb paralysis or excessive weight loss, according to IACUC guidelines or died due to sickness. Each mouse seen in the video was identified to have the same degree of leukemia at the initiation of the study. As observed, the mouse that received Dex-NP was active when compared with the lethargic behavior of the first mouse (free Dex treated) and the second mouse (added later; saline treated) at 3.5 weeks. The lethargic behavior may relate to the degree of sickness associated with the disease.

Figure B. CLSM images of Nalm6 leukemic cells treated with free Nile-red (L) and NR-NP (R). Please note the cytoplasmic staining in cells treated with free Nile Red. The nuclear regions are excluded.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health (RO1 DK56216, P20 RR016458, P20 RR017716), Delaware Health Sciences Alliance, Andrew McDonough B + Foundation, Caitlin Robb Foundation, Kids Runway for Research, Sones Brothers, Nemours Foundation and funds from the University of Delaware. We thank Dr. Christopher Frantz for drawing blood from volunteers used for evaluating hemolytic properties of NPs and Yingchao Chen for assisting with the TEM imaging of NPs.

References

- 1.Duncan R. The dawning era of polymer therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2(5):347–60. doi: 10.1038/nrd1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, Farokhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R. Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2(12):751–60. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Facts 2012. Leukemia and Lymphoma Society; 2012. p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunger SP, Lu X, Devidas M, Camitta BM, Gaynon PS, Winick NJ, Reaman GH, Carroll WL. Improved Survival for Children and Adolescents With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Between 1990 and 2005: A Report From the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1663–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.8018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Facts and Figures 2012. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2012. p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gradishar WJ, Tjulandin S, Davidson N, Shaw H, Desai N, Bhar P, Hawkins M, O'Shaughnessy J. Phase III trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel compared with polyethylated castor oil-based paclitaxel in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):7794–803. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhar S, Gu FX, Langer R, Farokhzad OC, Lippard SJ. Targeted delivery of cisplatin to prostate cancer cells by aptamer functionalized Pt(IV) prodrug-PLGA-PEG nanoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(45):17356–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809154105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis ME. The first targeted delivery of siRNA in humans via a self-assembling, cyclodextrin polymer-based nanoparticle: from concept to clinic. Mol Pharm. 2009;6(3):659–68. doi: 10.1021/mp900015y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. National Library of Medicine (PubMed Health) 2012 Jun 24; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0000773/

- 10.Hyman CB, Sturgeon P. Prednisone therapy of acute lymphatic leukemia in children. Cancer. 1956;9(5):965–70. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195609/10)9:5<965::aid-cncr2820090517>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaynon PS, Carrel AL. Glucocorticosteroid therapy in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;457:593–605. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4811-9_66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, Gurski LA, Zhong S, Xu X, Pochan DJ, Farach-Carson MC, Jia X. Amphiphilic Block Co-polyesters Bearing Pendant Cyclic Ketal Groups as Nanocarriers for Controlled Release of Camptothecin. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2011;22(10):1275–98. doi: 10.1163/092050610X504260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashi K, de Laey JJ. Indocyanine green angiography of choroidal neovascular membranes. Ophthalmologica. 1985;190(1):30–9. doi: 10.1159/000309489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoo HS, Park TG. Biodegradable polymeric micelles composed of doxorubicin conjugated PLGA-PEG block copolymer. J Control Release. 2001;70(1-2):63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shuai X, Merdan T, Schaper AK, Xi F, Kissel T. Core-cross-linked polymeric micelles as paclitaxel carriers. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15(3):441–8. doi: 10.1021/bc034113u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Garcia E, Andrieux K, Gil S, Kim HR, Le Doan T, Desmaele D, d'Angelo J, Taran F, Georgin D, Couvreur P. A methodology to study intracellular distribution of nanoparticles in brain endothelial cells. Int J Pharm. 2005;298(2):310–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bilensoy E, Sarisozen C, Esendagli G, Dogan AL, Aktas Y, Sen M, Mungan NA. Intravesical cationic nanoparticles of chitosan and polycaprolactone for the delivery of Mitomycin C to bladder tumors. Int J Pharm. 2009;371(1-2):170–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laane E, Panaretakis T, Pokrovskaja K, Buentke E, Corcoran M, Soderhall S, Heyman M, Mazur J, Zhivotovsky B, Porwit A, Grander D. Dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia involves differential regulation of Bcl-2 family members. Haematologica. 2007;92(11):1460–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yim EK, Lee MJ, Lee KH, Um SJ, Park JS. Antiproliferative and antiviral mechanisms of ursolic acid and dexamethasone in cervical carcinoma cell lines. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16(6):2023–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang JP, Wong CK, Lam CW. Role of caspases in dexamethasone-induced apoptosis and activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in human eosinophils. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;122(1):20–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01344.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Planey SL, Litwack G. Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in lymphocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279(2):307–12. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liem NL, Papa RA, Milross CG, Schmid MA, Tajbakhsh M, Choi S, Ramirez CD, Rice AM, Haber M, Norris MD, MacKenzie KL, Lock RB. Characterization of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia xenograft models for the preclinical evaluation of new therapies. Blood. 2004;103(10):3905–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lal D, Park JA, Demock K, Marinaro J, Perez AM, Lin MH, Tian L, Mashtare TJ, Murphy M, Prey J, Wetzler M, Fetterly GJ, Wang ES. Aflibercept exerts antivascular effects and enhances levels of anthracycline chemotherapy in vivo in human acute myeloid leukemia models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(10):2737–51. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lock RB, Liem N, Farnsworth ML, Milross CG, Xue C, Tajbakhsh M, Haber M, Norris MD, Marshall GM, Rice AM. The nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mouse model of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia reveals intrinsic differences in biologic characteristics at diagnosis and relapse. Blood. 2002;99(11):4100–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.11.4100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Kooten C, Stax AS, Woltman AM, Gelderman KA. Handbook of experimental pharmacology “dendritic cells”: the use of dexamethasone in the induction of tolerogenic DCs. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;(188):233–49. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-71029-5_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y, Song S, Yan Z, Fenniri H, Webster TJ. Self-assembled rosette nanotubes encapsulate and slowly release dexamethasone. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:1035–44. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S18755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fialho SL, Behar-Cohen F, Silva-Cunha A. Dexamethasone-loaded poly(epsilon-caprolactone) intravitreal implants: a pilot study. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;68(3):637–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L, Li Y, Zhang C, Wang Y, Song C. Pharmacokinetics and tolerance study of intravitreal injection of dexamethasone-loaded nanoparticles in rabbits. Int J Nanomedicine. 2009;4:175–83. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s6428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu X, Huang Y, Hanet C, Vandormael M, Legrand V, Dens J, Vandenbossche JL, Missault L, Vrints C, De Scheerder I. Study of antirestenosis with the BiodivYsio dexamethasone-eluting stent (STRIDE): a first-in-human multicenter pilot trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2003;60(2):172–8. doi: 10.1002/ccd.10636. discussion 179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffmann R, Langenberg R, Radke P, Franke A, Blindt R, Ortlepp J, Popma JJ, Weber C, Hanrath P. Evaluation of a high-dose dexamethasone-eluting stent. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94(2):193–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhar S, Kolishetti N, Lippard SJ, Farokhzad OC. Targeted delivery of a cisplatin prodrug for safer and more effective prostate cancer therapy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(5):1850–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011379108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X, Li J, Wang Y, Koenig L, Gjyrezi A, Giannakakou P, Shin EH, Tighiouart M, Chen ZG, Nie S, Shin DM. A folate receptor-targeting nanoparticle minimizes drug resistance in a human cancer model. ACS Nano. 2011;5(8):6184–94. doi: 10.1021/nn200739q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aliabadi HM, Mahmud A, Sharifabadi AD, Lavasanifar A. Micelles of methoxy poly(ethylene oxide)-b-poly(epsilon-caprolactone) as vehicles for the solubilization and controlled delivery of cyclosporine A. J Control Release. 2005;104(2):301–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aliabadi HM, Lavasanifar A. Polymeric micelles for drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2006;3(1):139–62. doi: 10.1517/17425247.3.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohanty C, Acharya S, Mohanty AK, Dilnawaz F, Sahoo SK. Curcumin-encapsulated MePEG/PCL diblock copolymeric micelles: a novel controlled delivery vehicle for cancer therapy. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2010;5(3):433–49. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mikhail AS, Allen C. Poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(epsilon-caprolactone) micelles containing chemically conjugated and physically entrapped docetaxel: synthesis, characterization, and the influence of the drug on micelle morphology. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11(5):1273–80. doi: 10.1021/bm100073s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panyam J, Williams D, Dash A, Leslie-Pelecky D, Labhasetwar V. Solid-state solubility influences encapsulation and release of hydrophobic drugs from PLGA/PLA nanoparticles. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93(7):1804–14. doi: 10.1002/jps.20094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen WC, Completo GC, Sigal DS, Crocker PR, Saven A, Paulson JC. In vivo targeting of B-cell lymphoma with glycan ligands of CD22. Blood. 2010;115(23):4778–86. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-257386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hickey T, Kreutzer D, Burgess DJ, Moussy F. Dexamethasone/PLGA microspheres for continuous delivery of an anti-inflammatory drug for implantable medical devices. Biomaterials. 2002;23(7):1649–56. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang L, Panetta JC, Cai X, Yang W, Pei D, Cheng C, Kornegay N, Pui CH, Relling MV. Asparaginase may influence dexamethasone pharmacokinetics in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(12):1932–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alexis F, Pridgen E, Molnar LK, Farokhzad OC. Factors affecting the clearance and biodistribution of polymeric nanoparticles. Mol Pharm. 2008;5(4):505–15. doi: 10.1021/mp800051m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhan C, Gu B, Xie C, Li J, Liu Y, Lu W. Cyclic RGD conjugated poly(ethylene glycol)-co-poly(lactic acid) micelle enhances paclitaxel anti-glioblastoma effect. J Control Release. 2010;143(1):136–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pan XQ, Zheng X, Shi G, Wang H, Ratnam M, Lee RJ. Strategy for the treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia based on folate receptor beta-targeted liposomal doxorubicin combined with receptor induction using all-trans retinoic acid. Blood. 2002;100(2):594–602. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.2.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen H, Ahn R, Van den Bossche J, Thompson DH, O'Halloran TV. Folate-mediated intracellular drug delivery increases the anticancer efficacy of nanoparticulate formulation of arsenic trioxide. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(7):1955–63. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harata M, Soda Y, Tani K, Ooi J, Takizawa T, Chen M, Bai Y, Izawa K, Kobayashi S, Tomonari A, Nagamura F, Takahashi S, Uchimaru K, Iseki T, Tsuji T, Takahashi TA, Sugita K, Nakazawa S, Tojo A, Maruyama K, Asano S. CD19-targeting liposomes containing imatinib efficiently kill Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Blood. 2004;104(5):1442–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang J, Tang Y, Li S, Liao C, Guo X. Targeting of the B-lineage leukemia stem cells and their progeny with norcantharidin encapsulated liposomes modified with a novel CD19 monoclonal antibody 2E8 in vitro. J Drug Target. 2010;18(9):675–87. doi: 10.3109/10611861003649720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoon TJ, Yu KN, Kim E, Kim JS, Kim BG, Yun SH, Sohn BH, Cho MH, Lee JK, Park SB. Specific targeting, cell sorting, and bioimaging with smart magnetic silica core-shell nanomaterials. Small. 2006;2(2):209–15. doi: 10.1002/smll.200500360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lapotko DO, Lukianova E, Oraevsky AA. Selective laser nano-thermolysis of human leukemia cells with microbubbles generated around clusters of gold nanoparticles. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38(6):631–42. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qian ZM, Li H, Sun H, Ho K. Targeted drug delivery via the transferrin receptor-mediated endocytosis pathway. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54(4):561–87. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang X, Koh CG, Liu S, Pan X, Santhanam R, Yu B, Peng Y, Pang J, Golan S, Talmon Y, Jin Y, Muthusamy N, Byrd JC, Chan KK, Lee LJ, Marcucci G, Lee RJ. Transferrin receptor-targeted lipid nanoparticles for delivery of an antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotide against Bcl-2. Mol Pharm. 2009;6(1):221–30. doi: 10.1021/mp800149s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure A. Delayed onset of disease symptoms in pre-clinical mouse models of ALL treated with Dex-NPs. (Video link below).

The pre-clinical models of ALL seen in the video are representatives of the three treatment groups. Each group received 100 μl of Dex-NP (5 mg/kg) or free Dex (5 mg/kg) or saline every alternate day throughout the study until they were euthanized on displaying signs of morbidity, including hind-limb paralysis or excessive weight loss, according to IACUC guidelines or died due to sickness. Each mouse seen in the video was identified to have the same degree of leukemia at the initiation of the study. As observed, the mouse that received Dex-NP was active when compared with the lethargic behavior of the first mouse (free Dex treated) and the second mouse (added later; saline treated) at 3.5 weeks. The lethargic behavior may relate to the degree of sickness associated with the disease.

Figure B. CLSM images of Nalm6 leukemic cells treated with free Nile-red (L) and NR-NP (R). Please note the cytoplasmic staining in cells treated with free Nile Red. The nuclear regions are excluded.