Abstract

Purpose of review

Our review focuses on recent developments across many settings regarding the diagnosis, screening and management of delirium, so as to inform these aspects in the context of palliative and supportive care.

Recent findings

Delirium diagnostic criteria have been updated in the long-awaited Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition. Studies suggest that poor recognition of delirium relates to its clinical characteristics, inadequate interprofessional communication and lack of systematic screening. Validation studies are published for cognitive and observational tools to screen for delirium. Formal guidelines for delirium screening and management have been rigorously developed for intensive care, and may serve as a model for other settings. Given that palliative sedation is often required for the management of refractory delirium at the end of life, a version of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale, modified for palliative care, has undergone preliminary validation.

Summary

Although formal systematic delirium screening with brief but sensitive tools is strongly advocated for patients in palliative and supportive care, it requires critical evaluation in terms of clinical outcomes, including patient comfort. Randomized controlled trials are needed to inform the development of guidelines for the management of delirium in this setting.

Keywords: assessment, delirium, management, palliative care, screening

INTRODUCTION

Delirium is a complex neurocognitive manifestation of an underlying medical abnormality such as organ failure, infection or drug effects. It occurs frequently in palliative and supportive care, particularly in patients with advanced cancer, wherein most will experience delirium in the terminal phase of the illness [1▪]. Both advanced age and dementia are recognized risks factors for delirium [2], and projected demographic changes over the next two decades suggest that both will increase dramatically [3,4]. Cancer is predominantly a disease of the elderly and an increase in cancer-associated deaths is also expected [5]. The cognitive deficits arising in relation to cancer, its treatment, aging, frailty and their pathophysiological intersection are well highlighted [6,7]. Given the increasing exposure of practitioners in palliative and supportive care to delirium in the context of a broad spectrum of life-threatening diseases and care settings, their approach to the diagnosis, screening and management of delirium warrants careful consideration. Our review addresses predominantly recent publications and advances in relation to these specific issues. The scope of this review does not include the pivotal role of family support and education to both family and carers in the management strategy.

Box 1.

no caption available

MEETING THE STANDARD DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR DELIRIUM

The diagnosis of delirium is based on clinical assessment and is guided by standard criteria [8▪▪,9▪]. The delirium diagnostic criteria of the International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition (ICD-10) and the recently published Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) represent definitive standards in terms of diagnosis [10▪,11], based on the best available evidence and maximal expert consensus at the time of their publication. DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for delirium are as follows [10▪]:

A disturbance in attention (i.e. reduced ability to direct, focus, sustain, and shift attention) and awareness (reduced orientation to the environment).

The disturbance develops over a short period of time (usually hours to a few days), represents a change from baseline attention and awareness and tends to fluctuate in severity during the course of a day.

An additional disturbance in cognition (e.g. memory deficit, disorientation, language, visuospatial ability or perception).

The disturbances in Criteria 1 and 2 are not better explained by another preexisting, established or evolving neurocognitive disorder and do not occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal, such as coma.

There is evidence from the history, physical examination or laboratory findings that the disturbance is a direct physiological consequence of another medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal (i.e. because of a drug of abuse or to a medication), or exposure to a toxin, or is because of multiple etiologies.

Published comparative study data regarding ICD-10 and DSM-5 are limited, given that the latter was only published in mid-2013. However, earlier studies comparing the delirium diagnostic criteria of DSM-IV and ICD-10 suggested that the DSM criteria were more inclusive [12]. In research studies, use of either ICD-10 or DSM-5 criteria is recommended as the gold standard diagnostic criteria [9▪]. To date, most studies have used earlier DSM versions, as they have been easier to operationalize and standard user-friendly tools have been developed to meet this need, such as the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) [13], the most widely used tool to diagnostically screen for delirium in both clinical practice and research studies.

Subsyndromal delirium (SSD) is a more controversial clinical entity than full syndrome delirium [14▪]. Although SSD does not have universally agreed and clearly defined descriptive diagnostic criteria, it is listed in the neurocognitive disorder section of DSM-5 as ‘attenuated delirium syndrome’ [10▪]. In their systematic review of SSD in older people, Cole et al.[15▪] defined SSD as the presence of one or more symptoms of delirium, not meeting criteria for delirium and not progressing to delirium. In the 12 studies meeting their inclusion criteria, there was a combined SSD prevalence of 23% (95% confidence interval 9–42%). It is unclear whether SSD should be diagnosed categorically, as defined by Cole et al., or viewed from a broader dimensional perspective and defined on the basis of a subdiagnostic score on a delirium diagnostic tool, such as the Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98 (DRS-R-98) [16]. In a point prevalence study of delirium in a single acute care hospital, Ryan et al.[17] found an SSD prevalence of 10%, based on a DRS-R-98 subdiagnostic score range of 7–11. Further studies and consensus are needed to better define SSD.

Franco et al.[18] conducted exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses on a pooled 7-country, 14-study dataset of 445 nondemented patients with either full syndrome or subsyndromal delirium, based on DRS-R-98 scores. The study confirmed a core phenotype of delirium, based on three core domains: circadian disturbances (sleep–wake cycle and motor behavior changes); attentional and other cognitive impairments; and higher-level thinking (language, thought processing) deficits. The refinement and development of future versions of standard diagnostic criteria hinges on studies such as this and on more rigorous characterization of the nature of delirium and its core domains.

ISSUES REGARDING DELIRIUM RECOGNITION IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Recent studies have detected delirium with a prevalence in the range of 20–27% in acute care [17,19], and a systematic review reported a documented range of 7–20% in emergency care [20▪]. Although delirium is a known reason for seeking emergency medical care [21], the level of recognition in this setting is strikingly poor [20▪]. Much higher prevalence rates have been reported in palliative care settings, yet the level of recognition and documentation here too is remarkably poor [22▪]. Recognition may clearly be difficult with some of the specific syndromal features of delirium, such as their tendency to overlap or comorbidly exist with depression and dementia [14▪,23]; fluctuation in levels of symptom presentation; and the presence of hypoactivity [24▪]. Underrecognition may also relate to many professional, site of care and institutional policy issues, such as a lack of knowledge regarding cognitive assessment [25▪,[26▪,[27,[28]; privacy and time constraints in the emergency department [27]; under appreciation of nursing observations [26▪]; failure to integrate the assessment of delirious symptoms within the care delivery process and a conventional care pathway that is supported by guidelines [26▪]; and failure to incorporate a screening tool [20▪,25▪,26▪,27,29▪].

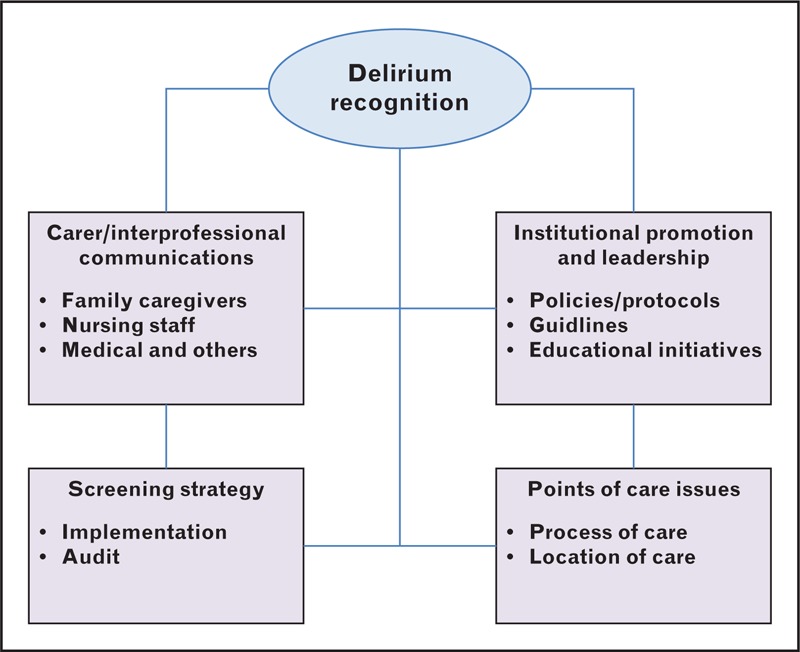

Collectively, delirium recognition problems require solutions at many levels, as graphically summarized in Fig. 1. At the carer level, there is a need for better communication within the interprofessional team and between the interprofessional team and family caregivers, so that valuable observations and information are appropriately conveyed [25▪,30,31▪,32▪]. At an institutional level, policies, protocols and guidelines regarding delirium detection need to be developed and implemented, and supported by effective educational initiatives [32▪,33,34▪]. The evidence-based guidelines that were developed by physicians and nurses for the management (including recognition and diagnosis) of pain, agitation and delirium in intensive care are a good example of how to address this need [35▪,36▪]. The implementation of guidelines on delirium recognition and screening is facilitated by many factors other than education and includes leadership; promotion as a quality improvement and safety culture initiative; and electronic health record documentation and prompting [37]. In terms of delirium recognition and screening, nurses occupy a uniquely strategic position in inpatient care; their 24-h level of patient contact affords an ideal opportunity to observe and record the fluctuating feature of delirium symptoms [33].

FIGURE 1.

Overarching framework to promote delirium recognition.

POTENTIAL DELIRIUM SCREENING STRATEGIES AND TOOLS

The ideal screening tool should have a high level of sensitivity, be brief and easy to use with minimal training [9▪]. In addition to minimizing burden on a vulnerable group of patients, the approach to delirium screening in supportive and palliative care should factor in the contextual aspects such as the specific location or point of care, or status in terms of disease trajectory [9▪,24▪]. Cognitive screening tools such as the Short Orientation Memory Concentration Test [38] are likely to be of most use on a more intermittent basis, particularly in relation transitions in the point of care such as emergency department attendance, hospice or acute care admission or outpatient encounters. Meanwhile, purely observational tools such as the Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (Nu-DESC) [39] are better adapted to the continuous surveillance mode of screening that might be required during inpatient care. Some tools have more of a hybrid nature, such as the CAM or the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS) [40], and include observational and cognitive assessment components. Using item response theory to improve screening brevity, a preliminary study by Yang et al. identified a parsimonious item bank of indicators that align with the major CAM features [41]. Although the MDAS was developed as a severity rating tool, it has also been used but not validated for delirium screening in palliative care [42].

Recent validation and other delirium screening tool studies are summarized in Table 1[43▪,[44,[45–[49,[50▪,[51▪,[52,[53▪]. Foremost among these is a systematic review of the CAM [43▪]. It concluded with the recommendation that the CAM should not replace clinical judgment in the diagnosis of delirium. Although the CAM has been validated in a palliative care population, its sensitivity is very much dependent on user training [54]. Combined use of the bCAM, a brief modified version, along with the Delirium Triage Scale (DTS) in older emergency department patients had an acceptable screening sensitivity range of 78–84% [44]. Interestingly, the DTS, which combines a single test of attention (to spell ‘lunch’ backwards) and a consciousness score from the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) [55], a brief observational tool, had a very high sensitivity at 98% for both physician and research assistant assessors. In terms of informant input, the Family version of the CAM (FAM-CAM) had a sensitivity of 88% in relation to the CAM as a diagnostic reference [45], whereas the Single Question in Delirium, the briefest of all tools, had moderately good sensitivity at 80% in a single study [46]. The original Nu-DESC validation study in mixed medical and hemato-oncology patients had a sensitivity of 85.7%, but more recent studies in postsurgical patients [47,48], and a study using caregiver ratings in home hospice care [49], all gave poorer results. Newer tools with promise but requiring further testing include the 4AT [50▪], Months Of The Year Backwards [51▪], Delirium Observational Screening Scale [52] and the Observational Scale of Level of Arousal [53▪], both observational.

Table 1.

Recent validation and other delirium screening tool studies

| Screening tool | Reference | Study sample | Administration | Sensitivity | Specificity | Comments |

| CAM | [43▪] | Mixed medical and postsurgical (n = 2442) | Mixed observational and direct patient questioning | 82% (Pooled) (95% CI: 69–91%) | 99% (Pooled) | Used frequently in research. Sensitivity dependent on rater training |

| (95% CI: 87–100%) | ||||||

| Brief CAM (bCAM) and DTS combined | [44] | Emergency department, aged ≥65 years | Mixed observational and direct patient questioning | 78–84% (Combination) | 95.8–97.2% (Combination) | DTS alone appears to have a high level of sensitivity at 98% |

| 74–84% (bCAM alone) | 95.8–96.9% (bCAM alone) | |||||

| 98% (DTS alone, research assistant and physician) | 56.2% (DTS alone, research assistant) | |||||

| FAM-CAM | [45] | Caregiver and elder (with dementia) dyads (n = 52) | Family observations used to score FAM-CAM and compared with interviewer CAM | 88% (95% CI: 47–99%) (using CAM as reference) | 98% (95% CI: 86–100%) (using CAM as reference) | High level of convergent validity of FAM-CAM and CAM: kappa = 0.85 |

| Single Question in Delirium | [46] | Friend or relatives of oncology inpatients (n = 21) | “Do you think (name) has been more confused lately?” | 80% (95% CI: 28.3–99.49%) | 71% (95% CI: 41.9–91.61%) | Very brief question. Good sensitivity using psychiatric diagnosis as reference |

| Nu-DESC | [47] | Post cardiac surgery (n = 142) | Observational, five items. Swedish version | 71.8% | 81.3% | Lower sensitivity for detection of hypoactive delirium |

| Nu-DESC | [48] | Postsurgical, aged ≥70 years (n = 196) | Observational, five items | 32% (Threshold score ≥2) | 29% (Threshold score ≥2) | The original cutoff score of ≥2 for positive screening performed poorly here |

| 80% (Threshold score ≥1) | 72% (Threshold score ≥1) | |||||

| Nu-DESC | [49] | Last week of life in a home hospice programme (n = 78) | Observational, five items | 63% (Nurse) | 67% (Nurse) | Diagnostic cutoff of >7/30 on Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale |

| 35% (Caregiver evening) | 80% (Caregiver evening) | |||||

| 21% (Caregiver night) | 95% (Caregiver night) | |||||

| 4AT | [50▪] | Elderly medical and postsurgical (n = 236), aged ≥70 years | Part observational. Has orientation questions, and months of the year backwards as a test of attention | 89.7% | 84.1% | Allows assessment of ‘untestable’ patients (drowsiness). Brief (<2 min), no special training required. Ideal for intermittent administration |

| (DSM-IV criteria used for diagnosis) | ||||||

| Months of the year backwards | [51▪] | Mixed general hospital (n = 265) | Direct patient questioning | 83.3% | 90.8% | Very brief. Needs further validation |

| Delirium Observation Screening Scale | [52] | Hospital Palliative Care Unit (n = 48) | Observational, 13 items | 81.8% | 96.1% | Brief, low burden Requires verbally active patients |

| Observational Scale of Level of Arousal | [53▪] | Acute hip fracture (n = 30). Exploratory study | Observational, four domains with 24 different descriptors | 87% | 81% | Verbal response is not required. Needs further validation |

bCAM, brief Confusion Assessment Method; CAM, Confusion Assessment method; CI, confidence interval; DTS, Delirium Triage Screen; FAM-CAM, family Confusion Assessment method; Nu-DESC, Nursing Delirium Screening Scale.

Data mainly from hospitalized but also long-term care and emergency department patients suggest that selective or targeted screening based on delirium risk factors or risk score is also an approach worth evaluating [2,7,56–58], though few data exist in relation to predictive models of delirium in the supportive and palliative care population. Despite demonstrable delirium prevention benefits in many other settings [59], a single evaluation study in palliative care with substantive methodological limitations showed no benefit [60]. Studies are needed to rigorously evaluate the benefits and potential harms of screening in relation to multiple outcomes such as medical intervention requirements, preventive strategies, delirium reversibility, care needs and economic burden [24▪].

PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT OF DELIRIUM WITH ANTIPSYCHOTICS

There remains a lack of good randomized controlled trial (RCT) evidence for the optimal treatment of delirium in palliative care patients. Furthermore, limited up-to-date clinical practice guidelines on delirium in this patient population are currently available [61▪]. Consequently, management is largely guided by expert opinion [62▪]. A survey of international delirium specialists, predominantly geriatricians and internal medicine physicians from Europe, demonstrated an ongoing lack of consensus as to the management of both hyperactive and hypoactive delirium and the frequency of using antipsychotic medications [63▪]. Haloperidol was the most frequently used antipsychotic for situations in which respondents used pharmacological approaches [63▪]. A pharmacovigilance study of haloperidol in 119 hospice/palliative care patients with delirium reported an average haloperidol dose of 2.1 mg every 24 h in a mostly elderly population with a poor performance status [64]. Over one-third of patients had a reduction in delirium as measured by the Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) [65] delirium scale after 48 h of treatment. After 10 days of treatment, somnolence was reported in 11 patients and urinary retention in six patients.

A recently published prospective double-blind RCT compared haloperidol with quetiapine in the management of multifactorial delirium in 52 medically ill hospital inpatients, aged 30–75 years (mean age 56.8 years and 67% male) in Thailand [66▪]. Both antipsychotics were administered with a flexible oral dose scheduled at bedtime and then every 2–3 h as needed for agitation, up to a set maximum dose per 24 h. Benzodiazepines and other antipsychotic medications were not allowed during the study period and there was no placebo arm. Thirteen out of 24 (54.2%) patients completed 7 days of treatment with quetiapine as compared with 22 of 28 (78.6%) patients who received haloperidol. Results were analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis. Mean doses of antipsychotic used were low: quetiapine 67.6 mg/day and haloperidol 0.8 mg/day. The response rates as measured by the reduction in the DRS-R-98 severity scores were not significantly different between the two groups. The total sleep time per day was greater in the quetiapine group, but was not significantly higher than the haloperidol group.

In a prospective observational study of 2453 general hospital inpatients in Japan, the three most common antipsychotics prescribed by consultation-liaison psychiatrists were risperidone (34%), quetiapine (32%) and intravenous haloperidol (20%) for those patients who were unable to take oral antipsychotic [67]. Mean patient age was 73.5 years and the comorbid dementia rate was 30%. Delirium resolved within 1 week in 54% of patients. The rate of serious adverse events was reported as 0.9% with no deaths attributed to antipsychotics. However, electrocardiogram monitoring was not reported. In the study by Hatta et al.[67] and another observational study of 80 patients referred to the consultation-liaison psychiatry service in a tertiary level hospital[68], it was the psychiatrist who determined the choice of antipsychotic.

Further to the 2012 Cochrane review by Candy et al.[69▪], recent systematic literature searches have also explored the evidence for antipsychotic therapy [62▪,70▪]. Out of 16 identified RCTs, palliative care patients were included in one study of 30 terminally ill patients [71]. None of the 15 prospective cohort studies specifically examined palliative care patients; however, four studies evaluated hospitalized cancer patients (total N = 139) [62▪]. A review of 28 prospective antipsychotic treatment studies for delirium concluded that around 75% of patients improved clinically when antipsychotic medications were administered [70▪]. Antipsychotic dose ranges (as measured by haloperidol equivalent daily doses) were higher in the palliative care and ICU populations. The authors suggested that improved patient outcomes may be demonstrated with the consistent use of protocolized care [70▪].

A recent systematic review on the pharmacological treatment of ICU delirium included three antipsychotic RCTs, of which two had placebo arms [72]. Sample sizes were small and the authors detailed methodological concerns. Similar to the intensive care and other settings, further well designed studies, including placebo RCTs, comparing the dosing schedule and antipsychotic selection in different delirium motor subtypes, and efficacy and adverse effects of antipsychotics in palliative care patients, are still needed.

Rather than relying on consensus expert opinion, the revised clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation and delirium in adult intensive patients assigned ‘no recommendation’ to statements if there was insufficient evidence or if, after reviewing the literature, the group could not reach consensus [35▪,36▪]. For adult ICU patients, the task force found low-level evidence for atypical antipsychotics and reduction in delirium duration but no evidence for haloperidol treatment and reduced duration of delirium [35▪]. Whereas some published delirium guidelines have suggested doses of antipsychotics, a less prescriptive approach may increase acceptance and uptake of a guideline into clinical practice, with local guideline adaptation specifically tailored for the local culture and environment.

In the elderly, it has been recommended that medications are reserved for severely agitated patients, or those with severe psychotic symptoms, and low antipsychotic starting doses have been suggested for this population, for example haloperidol 0.25–0.5 mg orally twice a day [8▪▪].

PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT WITH OTHER MEDICATIONS

There is growing evidence to support many hypotheses for the development of delirium, including a neuroinflammatory hypothesis and circadian rhythm dysregulation or melatonin deficiency [73▪,74,75]. In addition to proinflammatory cytokines leading to a reduction in melatonin production, many other medical conditions are also postulated to reduce melatonin activity [73▪]. Melatonin controls the sleep-wake cycle and circadian rhythms, and a small study of family caregivers (n = 20) confirmed sleep disturbance as a prodromal symptom for delirium [31▪]. A case study reported the successful treatment of a delirious 100-year-old Japanese male using a melatonin receptor agonist, ramelteon [76]. An older randomized placebo-controlled double blind trial of 145 internal medicine inpatients (mean age 84.5 years) demonstrated a significant reduction in the risk of delirium [77]; thus, the role of melatonin in reducing delirium in palliative care patients warrants further study.

Dexmedetomidine, an α2-receptor agonist, has been trialed for the treatment and prevention of delirium in ICU patients [78]. For palliative care patients, the roles of dexmedetomidine in the management of delirium sedation at the end of life and analgesia require further evidence [79].

NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT OF DELIRIUM

The role of nonpharmacological strategies in both the prevention and treatment of delirium in many medical ill populations, including elderly and postoperative patients, has been demonstrated [8▪▪]. These strategies have been recommended in the recent National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence clinical practice guidelines, which exclude patients at the end of life [80,81]. This is in contrast with palliative care populations and older people in long-term institutional care wherein nonpharmacological strategies have yet to demonstrate efficacy in delirium prevention [60,82]. Deprescribing (the dose reduction, withdrawal, or cessation) of psychoactive medications is an essential step in management in all patient populations [83], although for patients with advanced cancer, its benefits have not been clearly demonstrated at this time [84].

As each specialty (e.g. geriatrics, intensive care and palliative care) has a differing patient population, ongoing evidence and consensus should be sought for both the pharmacological and nonpharmacological management of delirium within each patient group. This can then be systematically evaluated for both efficacy, as assessed by delirium severity rating scales that have been validated in that specific population, and adverse effects using standardized tools specific to each particular patient population.

THE ROLE OF HYDRATION IN DELIRIUM MANAGEMENT

A trial of hydration is often given if attempts are made to reverse a delirium episode in line with the patient's goals of care. In a multicenter RCT of 129 hospice patients with cancer, incident delirium levels (as measured by the MDAS) deteriorated in both hydration (1000 ml/day) and placebo patient groups [85]. Similarly, a prospective study of 75 terminally ill cancer patients did not show a difference in the prevalence of hyperactive delirium between hydration and nonhydration groups [86]. Further studies including patients with delirium are needed to provide evidence for this practice.

PALLIATIVE SEDATION

For the optimal symptom management of refractory agitated delirium at the end of life, palliative sedation is frequently necessary, including the home setting [87–90]. Brinkkemper et al.[91▪] examined the availability of suitable tools for the appropriate monitoring of palliative sedation by the interprofessional team. A modified Spanish version of the RASS, originally validated in intensive care patients, was developed for the assessment of Spanish patients with advanced cancer [92]. In this study, 38 (24%) of the 156 patients admitted to the palliative care unit were receiving palliative sedation and 57 (37%) had delirium. When used by professionals experienced in palliative care, this modified version of the RASS demonstrated high inter-rater reliability.

In a small mixed-methods pilot study of 10 patients receiving palliative sedation or with an agitated delirium, the RASS-PAL (RASS modified for palliative care inpatients) also showed good psychometric properties and high inter-rater reliability [93]. The inter-rater intraclass correlation coefficient range of the RASS-PAL for the five assessment time points was 0.84–0.98. Training in the appropriate use of these instruments is essential, especially for nonexperienced staff [92,93].

CONCLUSION

Delirium continues to be poorly recognized and documented in many care settings, including palliative care. In addition to formal systematic screening, improved interprofessional team communication, educational initiatives and institutional policies that support the implementation of screening and a culture of better delirium recognition are necessary. The quest for briefer yet sensitive delirium screening tools continues and many validation and other tool assessment studies have recently been published. Screening tools should be selected on the basis of contextual need; at some points of care, a cognitive screening tool is most ideal, whereas an observational tool may be more appropriate for continuous inpatient surveillance and screening. Screening in supportive and palliative care settings needs to be critically evaluated in relation to outcomes such as the benefits and burdens of clinical interventions, including preventive measures quality of life and cost. RCTs of pharmacological and nonpharmacological therapeutic strategies are needed to inform the development of guidelines for the management of delirium in palliative and supportive care settings.

Acknowledgements

P.G.L. receives funding support through a joint research grant from the Gillin Family and Bruyère Foundation. Both P.G.L. and S.H.B. receive research awards from the Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa.

Conflicts of interest

Both authors declare no competing interests. Both authors were involved in multiple recent publications on delirium and some of these are referenced in this review.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

REFERENCES

- 1▪.Hosie A, Davidson PM, Agar M, et al. Delirium prevalence, incidence, and implications for screening in specialist palliative care inpatient settings: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2013; 27:486–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a systematic review of delirium that demonstrates its high occurrence rates in palliative care.

- 2.Ahmed S, Leurent B, Sampson EL. Risk factors for incident delirium among older people in acute hospital medical units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2014; 43:326–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010-2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology 2013; 80:1778–1783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacqmin-Gadda H, Alperovitch A, Montlahuc C, et al. 20-Year prevalence projections for dementia and impact of preventive policy about risk factors. Eur J Epidemiol 2013; 28:493–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Cancer Fact Sheet No297. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/index.html Accessed October 24th, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandelblatt JS, Hurria A, McDonald BC, et al. Cognitive effects of cancer and its treatments at the intersection of aging: what do we know; what do we need to know? Semin Oncol 2013; 40:709–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi D, Takahashi O, Arioka H, et al. A prediction rule for the development of delirium among patients in medical wards: Chi-Square Automatic Interaction Detector (CHAID) Decision Tree Analysis Model. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 21:957–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8▪▪.Inouye SK, Westendorp RG, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 2014; 383:911–922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a comprehensive, rigorous, state-of-the-art review.

- 9▪.Leonard M, Nekolaichuk C, Meagher D, et al. Practical assessment of delirium in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a comprehensive review of assessment tools with practical recommendations for use in palliative care settings.

- 10▪.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed2013; Arlington, VA:American Psychiatric Association, [Google Scholar]; These are long-awaited consensus-derived, gold standard diagnostic criteria.

- 11.World Health Organisation. ICD-10 Classifications of Mental and Behavioural Disorder: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laurila JV, Pitkala KH, Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS. Impact of different diagnostic criteria on prognosis of delirium: a prospective study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2004; 18:240–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med 1990; 113:941–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14▪.Leonard M, Agar M, Spiller J, et al. Delirium diagnostic and classification challenges in palliative care: subsyndromal delirium, comorbid delirium-dementia and psychomotor subtypes. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; (In Press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a rigorous review that addresses major diagnostic challenges in palliative care settings.

- 15▪.Cole MG, Ciampi A, Belzile E, Dubuc-Sarrasin M. Subsyndromal delirium in older people: a systematic review of frequency, risk factors, course and outcomes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 28:771–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a systematic review that highlights the importance of and controversies surrounding subsyndromal delirium.

- 16.Trzepacz PT, Mittal D, Torres R, et al. Validation of the Delirium Rating Scale-revised-98: comparison with the delirium rating scale and the cognitive test for delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 13:229–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryan DJ, O’Regan NA, Caoimh RO, et al. Delirium in an adult acute hospital population: predictors, prevalence and detection. BMJ Open 2013; 3: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franco JG, Trzepacz PT, Meagher DJ, et al. Three core domains of delirium validated using exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Psychosomatics 2013; 54:227–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whittamore KH, Goldberg SE, Gladman JR, et al. The diagnosis, prevalence and outcome of delirium in a cohort of older people with mental health problems on general hospital wards. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014; 29:32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20▪.Barron EA, Holmes J. Delirium within the emergency care setting, occurrence and detection: a systematic review. Emerg Med J 2013; 30:263–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a systematic review of delirium in a setting wherein the frequency of missed diagnosis is particularly high.

- 21.Doran DM, Hirdes JP, Blais R, et al. Adverse events among Ontario home care clients associated with emergency room visit or hospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13:227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22▪.Hey J, Hosker C, Ward J, et al. Delirium in palliative care: detection, documentation and management in three settings. Palliat Support Care 2013; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Although this is a retrospective study, it is well structured and provides useful discussion. It demonstrates the poor level of delirium documentation and recognition in palliative care settings.

- 23.Downing LJ, Caprio TV, Lyness JM. Geriatric psychiatry review: differential diagnosis and treatment of the 3 D's - delirium, dementia, and depression. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2013; 15:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24▪.Lawlor PG, Davis DHJ, Ansari M, et al. An analytic framework for delirium research in palliative care settings: integrated epidemiological, clinician-researcher and knowledge user perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is an open-access article that summarizes the input of multiple researchers, generates a series of pertinent research questions that arise along the care pathway for a patient in a palliative care setting and reports on survey findings in an effort to prioritize the research questions.

- 25▪.Hosie A, Agar M, Lobb E, et al. Palliative care nurses’ recognition and assessment of patients with delirium symptoms: a qualitative study using critical incident technique. Int J Nurs Stud 2014; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Clearly presented qualitative study that examines the critical issues relating to nurses recognition of delirium.

- 26▪.Hosie A, Lobb E, Agar M, et al. Identifying the barriers and enablers to palliative care nurses’ recognition and assessment of delirium symptoms: a qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is another well presented qualitative study that identified both barriers and enablers in relation to nurses recognition of delirium.

- 27.Kennelly SP, Morley D, Coughlan T, et al. Knowledge, skills and attitudes of doctors towards assessing cognition in older patients in the emergency department. Postgrad Med J 2013; 89:137–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaneko M, Ryu S, Nishida H, et al. Nurses’ recognition of the mental state of cancer patients and their own stress management - a study of Japanese cancer-care nurses. Psychooncology 2013; 22:1624–1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29▪.O’Hanlon S, O’Regan N, Maclullich AM, et al. Improving delirium care through early intervention: from bench to bedside to boardroom, Journal of Neurology. Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014; 85:207–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a review that focuses on early recognition, addresses health policy needs regarding delirium and provides a useful 12-point plan for improved delirium care.

- 30.Saczynski JS, Kosar CM, Xu G, et al. A tale of two methods: chart and interview methods for identifying delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62:518–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31▪.Kerr CW, Donnelly JP, Wright ST, et al. Progression of delirium in advanced illness: a multivariate model of caregiver and clinician perspectives. J Palliat Med 2013; 16:768–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provides detailed and useful insights from family caregivers regarding the prodromal phase of delirium development.

- 32▪.Brummel NE, Vasilevskis EE, Han JH, et al. Implementing delirium screening in the ICU: secrets to success. Crit Care Med 2013; 41:2196–2208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provides useful implementation strategies for delirium screening derived from the ICU experience.

- 33.Rice KL, Castex J. Strategies to improve delirium recognition in hospitalized older adults. J Contin Educ Nurs 2013; 44:55–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34▪.Yanamadala M, Wieland D, Heflin MT. Educational interventions to improve recognition of delirium: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013; 61:1983–1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a systematic review highlighting educational initiatives to promote knowledge and skill but also the importance of leadership engagement, and use of clinical pathways and assessment tools.

- 35▪.Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2013; 41:263–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; These are the comprehensive, rigorously developed guidelines that could serve as a model for guideline development in other settings.

- 36▪.Barr J, Kishman CP, Jr, Jaeschke R. The methodological approach used to develop the 2013 Pain, Agitation, and Delirium Clinical Practice Guidelines for adult ICU patients. Crit Care Med 2013; 41 (9 Suppl 1):S1–S15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article describes the rigorous approach used in the development of guidelines for delirium management in intensive care.

- 37.Carrothers KM, Barr J, Spurlock B, et al. Contextual issues influencing implementation and outcomes associated with an integrated approach to managing pain, agitation, and delirium in adult ICUs. Crit Care Med 2013; 41 (9 Suppl 1):S128–S135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, et al. Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:734–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaudreau JD, Gagnon P, Harel F, et al. Fast, systematic, and continuous delirium assessment in hospitalized patients: the nursing delirium screening scale. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005; 29:368–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Roth A, et al. The Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997; 13:128–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang FM, Jones RN, Inouye SK, et al. Selecting optimal screening items for delirium: an application of item response theory. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013; 13:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fadul N, Kaur G, Zhang T, et al. Evaluation of the memorial delirium assessment scale (MDAS) for the screening of delirium by means of simulated cases by palliative care health professionals. Support Care Cancer 2007; 15:1271–1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43▪.Shi Q, Warren L, Saposnik G, Macdermid JC. Confusion assessment method: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2013; 9:1359–1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a systematic review of the most commonly used assessment tool in delirium screening.

- 44.Han JH, Wilson A, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Diagnosing delirium in older emergency department patients: validity and reliability of the delirium triage screen and the brief confusion assessment method. Ann Emerg Med 2013; 62:457–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steis MR, Evans L, Hirschman KB, et al. Screening for delirium using family caregivers: convergent validity of the Family Confusion Assessment Method and interviewer-rated Confusion Assessment Method. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60:2121–2126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sands MB, Dantoc BP, Hartshorn A, et al. Single Question in Delirium (SQiD): testing its efficacy against psychiatrist interview, the Confusion Assessment Method and the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. Palliat Med 2010; 24:561–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lingehall HC, Smulter N, Engstrom KG, et al. Validation of the Swedish version of the Nursing Delirium Screening Scale used in patients 70 years and older undergoing cardiac surgery. J Clin Nurs 2013; 22:2858–2866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neufeld KJ, Leoutsakos JS, Sieber FE, et al. Evaluation of two delirium screening tools for detecting postoperative delirium in the elderly. Br J Anaesth 2013; 111:612–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de la Cruz M, Noguera A, San Miguel-Arregui MT, et al. Delirium, agitation, and symptom distress within the final seven days of life among cancer patients receiving hospice care. Palliat Support Care 2014; 20:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50▪.Bellelli G, Morandi A, Davis DH, et al. Validation of the 4AT, a new instrument for rapid delirium screening: a study in 234 hospitalised older people. Age Ageing 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Validation of a new, extremely brief screening tool with high sensitivity (89.7%).

- 51▪.O’Regan NA, Ryan DJ, Boland E, et al. Attention! A good bedside test for delirium? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article highlights the value of ‘months of the year backwards’ test as a brief test of attention.

- 52.Detroyer E, Clement PM, Baeten N, et al. Detection of delirium in palliative care unit patients: A prospective descriptive study of the Delirium Observation Screening Scale administered by bedside nurses. Palliat Med 2014; 28:79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53▪.Tieges Z, McGrath A, Hall RJ, Maclullich AM. Abnormal level of arousal as a predictor of delirium and inattention: an exploratory study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 21:1244–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Describes the use of an observational scale to rate level of arousal. This is a brief, minimally burdensome tool that might be studied further in palliative and supportive care settings.

- 54.Ryan K, Leonard M, Guerin S, et al. Validation of the confusion assessment method in the palliative care setting. Palliat Med 2009; 23:40–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 166:1338–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carrasco MP, Villarroel L, Andrade M, et al. Development and validation of a delirium predictive score in older people. Age Ageing 2014; 43:346–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cole MG, McCusker J, Voyer P, et al. Symptoms of delirium predict incident delirium in older long-term care residents. Int Psychogeriatr 2013; 25:887–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kennedy M, Enander RA, Tadiri SP, et al. Delirium risk prediction, healthcare use and mortality of elderly adults in the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62:462–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reston JT, Schoelles KM. In-facility delirium prevention programs as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158 (5 Pt 2):375–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gagnon P, Allard P, Gagnon B, et al. Delirium prevention in terminal cancer: assessment of a multicomponent intervention. Psychooncology 2012; 21:187–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61▪.Bush SH, Bruera E, Lawlor PG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for delirium management: potential application in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article highlights the need for formal evaluation of implemented delirium guidelines in palliative care populations, and also for more robust research evidence to inform their content.

- 62▪.Bush SH, Kanji S, Pereira JL, et al. Treating an established episode of delirium in palliative care: expert opinion and review of the current evidence base with recommendations for future development. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article describes expert consensus opinion and research agenda from an international multidisciplinary delirium study planning meeting.

- 63▪.Morandi A, Davis D, Taylor JK, et al. Consensus and variations in opinions on delirium care: a survey of European delirium specialists. Int Psychogeriatr 2013; 25:2067–2075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a survey of international delirium specialists that not only reveals similarities but also many differences in approaches to delirium management.

- 64.Crawford GB, Agar MM, Quinn SJ, et al. Pharmacovigilance in hospice/palliative care: net effect of haloperidol for delirium. J Palliat Med 2013; 16:1335–1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.National Cancer Institute. Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events. Available at: http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/About.html Accessed April 25th, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 66▪.Maneeton B, Maneeton N, Srisurapanont M, Chittawatanarat K. Quetiapine versus haloperidol in the treatment of delirium: a double-blinded, randomized, controlled trial. Drug Des Devel Ther 2013; 7:657–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This double-blinded RCT using low doses of either quetiapine or haloperidol in 52 medically ill hospitalized patients reported similar response and remission rates between groups.

- 67.Hatta K, Kishi Y, Wada K, et al. Antipsychotics for delirium in the general hospital setting in consecutive 2453 inpatients: a prospective observational study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014; 29:253–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yoon HJ, Park KM, Choi WJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of haloperidol versus atypical antipsychotic medications in the treatment of delirium. BMC Psychiatry 2013; 13: 240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69▪.Candy B, Jackson KC, Jones L, et al. Drug therapy for delirium in terminally ill adult patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 11:004770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Published online in November 2012, this intervention review updated the previous Cochrane review by Jackson and Lipman in 2004. Candy's review found no new prospective trials meeting the inclusion criteria since the 2004 review. The authors concluded that insufficient evidence exists for drug therapy in delirium management in this population.

- 70▪.Meagher DJ, McLoughlin L, Leonard M, et al. What do we really know about the treatment of delirium with antipsychotics? Ten key issues for delirium pharmacotherapy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 21:1223–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a thought-provoking article that concludes although evidence is limited, there is tentative support for antipsychotics in the treatment of delirium. The article includes excellent summary tables of pharmacological studies of antipsychotics in the treatment of delirium across patient populations, including palliative care, and provides Jadad scores for comparison studies.

- 71.Breitbart W, Marotta R, Platt MM, et al. A double-blind trial of haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and lorazepam in the treatment of delirium in hospitalized AIDS patients. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:231–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bathula M, Gonzales JP. The pharmacologic treatment of intensive care unit delirium: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother 2013; 47:1168–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73▪.Maldonado JR. Neuropathogenesis of delirium: review of current etiologic theories and common pathways. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 21:1190–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is an extremely comprehensive and detailed review, which summarizes seven theories that are currently proposed for the pathogenesis of delirium.

- 74.de Rooij SE, van Munster BC. Melatonin deficiency hypothesis in delirium: a synthesis of current evidence. Rejuvenation Res 2013; 16:273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fitzgerald JM, Adamis D, Trzepacz PT, et al. Delirium: a disturbance of circadian integrity? Med Hypotheses 2013; 81:568–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tsuda A, Nishimura K, Naganawa E, et al. Successfully treated delirium in an extremely elderly patient by switching from risperidone to ramelteon. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2013; 67:130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Al-Aama T, Brymer C, Gutmanis I, et al. Melatonin decreases delirium in elderly patients: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011; 26:687–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mo Y, Zimmermann AE. Role of dexmedetomidine for the prevention and treatment of delirium in intensive care unit patients. Ann Pharmacother 2013; 47:869–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Komasawa N, Kimura Y, Hato A, Ikegaki J. Three successful cases of continuous dexmedetomidine infusion for the treatment of intractable delirium associated with cancer pain. Masui 2013; 62:1450–1452 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.O’Mahony R, Murthy L, Akunne A, Young J. Guideline Development Group. Synopsis of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guideline for prevention of delirium. Ann Intern Med 2011; 154:746–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Young J, Murthy L, Westby M, et al. Guideline Development Group. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of delirium: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2010; 341:c3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Clegg A, Siddiqi N, Heaven A, et al. Interventions for preventing delirium in older people in institutional long-term care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 1:CD009537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thompson W, Farrell B. Deprescribing: what is it and what does the evidence tell us? Can J Hosp Pharm 2013; 66:201–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lindsay J, Dooley M, Martin J, et al. Reducing potentially inappropriate medications in palliative cancer patients: evidence to support deprescribing approaches. Support Care Cancer 2014; 22:1113–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bruera E, Hui D, Dalal S, et al. Parenteral hydration in patients with advanced cancer: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31:111–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nakajima N, Hata Y, Kusumuto K. A clinical study on the influence of hydration volume on the signs of terminally ill cancer patients with abdominal malignancies. J Palliat Med 2013; 16:185–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.de Graeff A, Dean M. Palliative sedation therapy in the last weeks of life: a literature review and recommendations for standards. J Palliat Med 2007; 10:67–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cherny NI, Radbruch L. Board of the European Association for Palliative Care. European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) recommended framework for the use of sedation in palliative care. Palliat Med 2009; 23:581–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Rosati M, et al. Palliative sedation in end-of-life care and survival: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30:1378–1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mercadante S, Porzio G, Valle A, et al. Home Care-Italy Group. Palliative sedation in patients with advanced cancer followed at home: a prospective study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; 47:860–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91▪.Brinkkemper T, van Norel AM, Szadek KM, et al. The use of observational scales to monitor symptom control and depth of sedation in patients requiring palliative sedation: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2013; 27:54–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Highlights that the few studies reporting the use of observational monitoring tools for palliative sedation, as determined by their systematic review, were of limited quality and identified current gaps for future research.

- 92.Benitez-Rosario MA, Castillo-Padros M, Garrido-Bernet B, et al. Members of the Asocacion Canaria de Cuidados Paliativos (CANPAL) Research Network. Appropriateness and reliability testing of the modified Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale in Spanish patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013; 45:1112–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bush SH, Grassau PA, Yarmo MN, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale modified for palliative care inpatients (RASS-PAL): a pilot study exploring validity and feasibility in clinical practice. BMC Palliat Care 2014; 13: 17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]