Abstract

Natural products are a major source for cancer drug development. NK cells are a critical component of innate immunity with the capacity to destroy cancer cells, cancer initiating cells, and clear viral infections. However, few reports describe a natural product that selectively stimulates NK cell IFN-γ production and unravel a mechanism of action. In this study, through screening, we found that a natural product, phyllanthusmin C (PL-C), alone enhanced IFN-γ production by human NK cells. PL-C also synergized with IL-12, even at the low cytokine concentration of 0.1 mg/ml, and stimulated IFN-γ production in both human CD56bright and CD56dim NK cell subsets. Mechanistically, TLR1 and/or TLR6 mediated PL-C’s activation of the NF-κB p65 subunit that in turn bound to the proximal promoter of IFNG and subsequently resulted in increased IFN-γ production in NK cells. However, IL-12/IL-15 receptors and their related STAT signaling pathways were not significantly modulated by PL-C. PL-C induced little or no T cell IFN-γ production or NK cell cytotoxicity. Collectively, we identify a natural product with the capacity to selectively activate human NK cell IFN-γ. Given the role of IFN-γ in immune surveillance, additional studies to understand the role of this natural product in prevention of cancer or infection in select populations are warranted.

Keywords: Phyllanthusmin C, NK cells, IFN-γ, NF-κB, p65, TLR

Introduction

NK cells are a critical component of innate immunity, and represent the first line of defense against tumor cells and viral infections (1). They are large granular lymphocytes with both cytotoxicity and cytokine-producing effector functions, representing one of major sources of IFN-γ in our bodies (2). IFN-γ has an important role in the activation of both innate and adaptive immunity. IFN-γ not only displays antiviral activity (3–5), but also regulates various cells of the immune system and performs a crucial role in tumor immunosurveillance (6), through enhancing tumor immunogenicity and antigen presentation (7), as well as inducing tumor cell apoptosis (8, 9). NK cell-derived IFN-γ also activates macrophages, promotes the adaptive T helper 1 immune response (10), and regulates CD8+ T cell priming (11) and dendritic cell migration during influenza A infection (11, 12). In addition, IFN-γ has the capacity to recruit CD27+ mature NK cells to lymph nodes during infection or inflammation (13). Deficiency in NK cell-mediated IFN-γ production is associated with an increased incidence of both malignancy and infection (14).

Exogenous recombinant IFN-γ has been used in various cancer immunotherapy trials, however, outcomes have been disappointing due to its toxicity (15). Enhancing endogenous IFN-γ production by stimulation with cytokines such as IL-2, IL-12, IL-15, IL-18 and IL-21, administered either individually or synergistically, has also been tried in preclinical or clinical studies (16–20). However, these approaches also had limitations (21) for many reasons, such as induction of regulatory T cells by IL-2 (22, 23), impairment of cytokine signaling via STAT-4 as a result of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or chemotherapy (24–26), and the systemic toxicity associated with the exogenous delivery of these cytokines that can, in some instances, activate a multitude of immune effector cells (27, 28).

There are multiple signaling pathways to control IFN-γ gene expression and its protein secretion. These include positive signaling pathways, such as the MAPK signaling pathway, the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, the T-BET signaling pathway, and the NF-κB signaling pathway, as well as negative regulation via the TGF-β signaling pathway (29). Activation of the MAPK pathway involves induction of ERK and p38 kinase, in part through the activation of Fos and Jun transcription factors (29). Binding of IL-12 to its receptor (R) activates the JAKs-Tyrosine Kinase 2 and JAK2, leading to phosphorylation and activation of STAT-4 and other STATs as well (30). In human NK cells, IL-15 activates the binding of STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, and STAT5 to the regulatory sites of the IFNG gene (18). The activation of numerous transcription factors, including NF-κB, may be critical for achieving a maximal activation of IFNG transcription. Many of the synergistic stimuli that enhance IL-12-mediated IFN-γ production by NK cells share the ability to activate the transcription factor NF-κB (31). NF-κB is also an important downstream mediator of TLR signaling, which becomes activated in immune cells during injury and infections (32–34) .

Small-molecule natural products have been the single most productive source for the development of drugs. By 1990, over 50% of all new drugs were either natural products or their analogues (35, 36), including those which act through immune modulation (37). This proportion has decreased in recent years, perhaps because the proportion of synthetic small molecules has increased, while performing the isolation of natural products from crude extracts is time-consuming and labor-intensive; however, natural products and their analogues still account for over 40% of newly developed drugs (38, 39). The popularity of developing drugs from natural products and their analogues is at least in part due to their relatively low side effects. Natural products provide enormous structural diversity, which also facilitates new drug discovery (40).

In this study, we screened natural products for their ability to enhance NK cell production of IFN-γ. We found that phyllanthusmin C (PL-C), a small molecule enriched in lignans of plants, can induce NK cell IFN-γ production in the presence or absence of monokines such as IL-12 and IL-15. The induced NK cell activity resulted from enhanced TLR-NF-κB signaling. Interestingly, PL-C negligibly activated T cell IFN-γ production and also did not activate NK cell cytotoxicity. This selectivity of PL-C in immune activation should make it more suitable for development of clinically useful immune modulator.

Materials and methods

Isolation of PBMCs and NK cells

Human PBMCs and NK cells were freshly isolated from leukopaks (American Red Cross, Columbus, OH) as described previously (41). PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll-Paque Plus (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA) density gradient centrifugation. NK cells (CD56+CD3−) were enriched with RosetteSep NK cell enrichment mixture (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). The purity of enriched NK cells was ≥80 % (data not shown), assessed by flow cytometric analysis after staining with CD56-APC and CD3-FITC antibodies (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). These enriched NK cells were further purified with CD56 magnetic beads and LS columns (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). The purity of magnetic bead-purified NK cells was ≥ 99.5% (data not shown), as determined by the aforementioned flow cytometric analysis. CD56bright and CD56dim NK cell subsets were sorted by a FACS Aria II cell sorter (BD Biosciences) based on CD56 cell-surface density after staining with CD56-APC and CD3-FITC antibodies. The purity of CD56bright and CD56dim subsets was ≥ 99.0% (data not shown). All human work is approved by The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board.

Cell culture and treatment

Primary NK cells, the NKL cell line (a generous gift of Dr. M. Robertson, Indiana University) and PMBCs were cultured or maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 50 µg/ml penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin, and 10% FBS (Invitrogen) at 37°C in 5% CO2. The NKL cell line is IL-2-dependent, and therefore 150 IU/ml rhIL-2 (Hoffman-LaRoche Inc, Pendergrass, GA) was included in the culture, but cells were starved for IL-2 for 24 hours prior to stimulation. For stimulation, cells were suspended at a density of 2.5 × 106 cells/ml and seeded into a 6-well culture plate and rested for 1–2 hours, followed by addition of stimuli. Cells were treated with PL-C in the presence or absence of IL-12 (10 ng/ml) or IL-15 (100 ng/ml) (R&D Systems Inc, Minneapolis, MN) for 18 hours or the indicated time. Cells were harvested for flow cytometric analysis or for RNA extraction to synthesize cDNA for real-time RT-PCR or for protein extraction to perform immunoblotting. Cell-free supernatants were collected to determine IFN-γ secretion by ELISA with commercially available mAb pairs (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s protocol as described previously (42). To test if PL-C also enhanced IFN-γ production when IL-12 or IL-15 were given at lower concentrations, purified primary NK cells were treated with 1, 0.1 ng/ml IL-12 or 10, 1 ng/ml IL-15 with or without 10 µM PL-C for 24 hours. Supernatants were then harvested for IFN-γ ELISA assay. To study NF-κB involvement in PL-C-mediated enhancement of NK cell IFN-γ production, 10 µM NF-κB inhibitor N-tosyl-L-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone (TPCK) was used to treat both purified primary NK cells or NKL cells together with PL-C in the presence of IL-12, compared to no-TPCK treatment. For TLR blocking assays, the above mentioned cells were pretreated with 10 µg/ml α-TLR1 (InvivoGen), α-TLR3 (Hycult Biotech), α-TLR6 (InvivoGen) or 10 µg/ml α-TLR1 plus 10 µg/ml α-TLR6 for 1 hour prior to PL-C and/or IL-12 stimulation. Cells treated with the same concentration of non-specific α-IgG were taken as control. The blocking antibodies were also kept in the culture during the stimulation. For studying the effect of PL-C combined with TLR agonist, cells were treated with or without various concentration of Pam3CSK4 (TLR1/2 agonist) or FSL-1 (TLR6/2 agonist) for 18 hours.

PL-C was isolated in chromatographically and spectroscopically pure form from the above-ground parts of plant Phyllanthus poilanei or synthesized (to be reported elsewhere).

Intracellular flow cytometry

Intracellular flow cytometry was performed as previously described (42, 43). Briefly, 1 µl/ml Golgi Plug (BD Biosciences) was added 5 hours before cell harvest. After surface staining with CD3-FITC and CD56-APC human antibodies (BD Biosciences), the cells were then washed and resuspended in Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences) at 4°C for 20 min. Fixed and permeabilized cells were stained with anti-IFN-γ-PE antibody (BD Biosciences). Labeled cells were used for a flow cytometric analysis. NK cells were gated on CD56+CD3− cells, and CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were gated on CD56−CD3+CD4+ or CD56−CD3+CD8+ cells, respectively. Data were acquired using a LSRII (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer, and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Real-time RT-PCR

Real-time RT-PCR was performed as previously described (42, 43). Briefly, total RNA from purified primary NK cells or NKL cells was isolated with RNeasy kit (Qiagene, Valencia, CA). cDNA was synthesized from 1–3 µg total RNA with random hexamers (Invitrogen). Real-time RT-PCR reactions were performed as a multiplex reaction with the primer/probe set specific for IFNG, GZMA (Granzyme A), GZMB (Granzyme B), PRF1 (Perforin), Fasl (Fas ligand) and an internal control 18S rRNA (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). mRNA expression of IL-12Rβ1 (IL-12Rβ1), IL-12Rβ2 (IL-12Rβ2), IL-15Rα (IL-15R α), IL-15Rβ (IL-15Rβ), and HPRT1 mRNA was detected by SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The primers used are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Expression levels were normalized to an 18S or HPRT1 internal control and analyzed by the ΔΔCt method.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity assay was performed as previously described (42, 43). Briefly, multiple myeloma cell line ARH-77 target cells were labeled with 51Cr and co-cultured with purified primary NK cells, which were pre-treated with or without 10 µM PL-C for 8 hours in the presence of IL-12 (10 ng/ml) or IL-15 (100 ng/ml) prior to the co-culture, at various effector/target ratios (E/T) in 96-well V-bottom plate at 37°C for 4 hours. At the end of co-culture, 100 µl supernatants were harvested and transferred into scintillation vials with a 3-ml liquid scintillation cocktail (Fisher Scientific). The release of 51Cr was countered on TopCount counter (Canberra Packard, Meriden, CT, USA). Target cells incubated in 1% SDS or complete medium were used to determine maximal or spontaneous 51Cr release. The standard formula of 100 × (cpm experimental release – cpm spontaneous release) / (cpm maximal release – cpm spontaneous release) was used to calculate the percentage of specific lysis.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed as previously described (42, 43). The equal number of cells from each sample were directly lysed in 2× Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) supplemented with 2.5% β-mercaptoethonal, boiled for 5 min, and subjected to immunoblotting analysis as described previously (42). Antibodies against p65, phosphorylated (p)-p65, p-STAT3, p-STAT4, p-STAT5, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5 (Cell Signaling Technology Inc, Danvers, MA), and T-BET (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa cruz, CA) were used, followed by immunoblotting with antibodies against β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotech) as internal control.

EMSA

Nuclear extracts were isolated using a nuclear extract kit according to manufacturer’s instruction (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). EMSA was performed as previously described (44). Briefly, a 32P-labeled double stranded oligonucleotide, 5’-GGGAGGTACAAAAAAATTTCCAGTCCTTGA-3’, containing an NF-κB binding site C3–3P (−278 to −268) of the IFNG promoter (45), was incubated with nuclear extracts (2 µg) for 20 minutes before resolving on a 6% DNA retardation gel (Invitrogen). After electrophoresis, the gel was transferred onto filter paper, dried, and exposed to X-ray films. In antibody gel supershift assays, p65 antibodies (Rockland Immunochemicals Inc, Gilbertsville, PA) were added to the DNA-protein binding reactions after incubation at room temperature for 10 minutes, followed by an additional incubation for 20 minutes before gel loading.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP assay was carried out with a ChIP assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. An equal amount (10 µg) of rabbit monoclonal anti-p65 antibodies or normal rabbit IgG antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology Inc) were used to precipitate the cross-linked DNA/protein complexes. The sequences of primers spanning the different NF-κB sites on the IFNG promoter have been described previously (31). DNA precipitated by the anti-p65 or the normal IgG antibodies was quantified by real-time PCR, and values were normalized to input DNA.

TLR activation assessment

Human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells were co-transfected with TLR1 or 6 expression plasmids (0.5 µg for each) for 24 hours along with pGL-3κB-Luc (1 µg), which contains three tandem repeats of κB site (46), and pRL-TK renilla-luciferase control plasmid (5 ng, Promega). The cells were then treated with various concentrations of PL-C for additional 24 hours after replacing old media with fresh media. Firefly and renilla luciferase activities were detected by using Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega), and the ratio of firefly/renilla luciferase activities was used to determine the relative activity of NF-κB.

TLR1 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) knockdown in NKL cells

A TLR1 shRNA plasmid was constructed by inserting RNA interference sequence (GTCTCATCCACGTTCCTAAT) into GFP expressing pSUPER-retrovirus vector. Viruses were prepared by transfecting the shRNA plasmid and packaging plasmids into phoenix cells. Infection was performed as follows: NKL cells were cultured in virus-containing media and centrifuged at 1,800 rpm at 32°C for 45 minutes, and then incubated for 2 to 4 hours at 32°C. This infection cycle was repeated twice. GFP-positive cells were sorted on a FACSAria II cell sorter (BD Bioscience). Knockdown of TLR1 in the sorted NKL cells was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR.

Statistical analysis

An unpaired student t test was used to compare two independent conditions (such as PL-C versus control) for continuous endpoints. Paired t test was used to compare two conditions with repeated measures from the same donor. A one-way ANOVA model was used for multiple comparisons. A two-way ANOVA model was used to evaluate the synergistic effect between IL-12 or IL-15 and PL-C. P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni method. All tests are two-sided. A P value < 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

Results

PL-C selectively enhances IFN-γ production in human NK cells

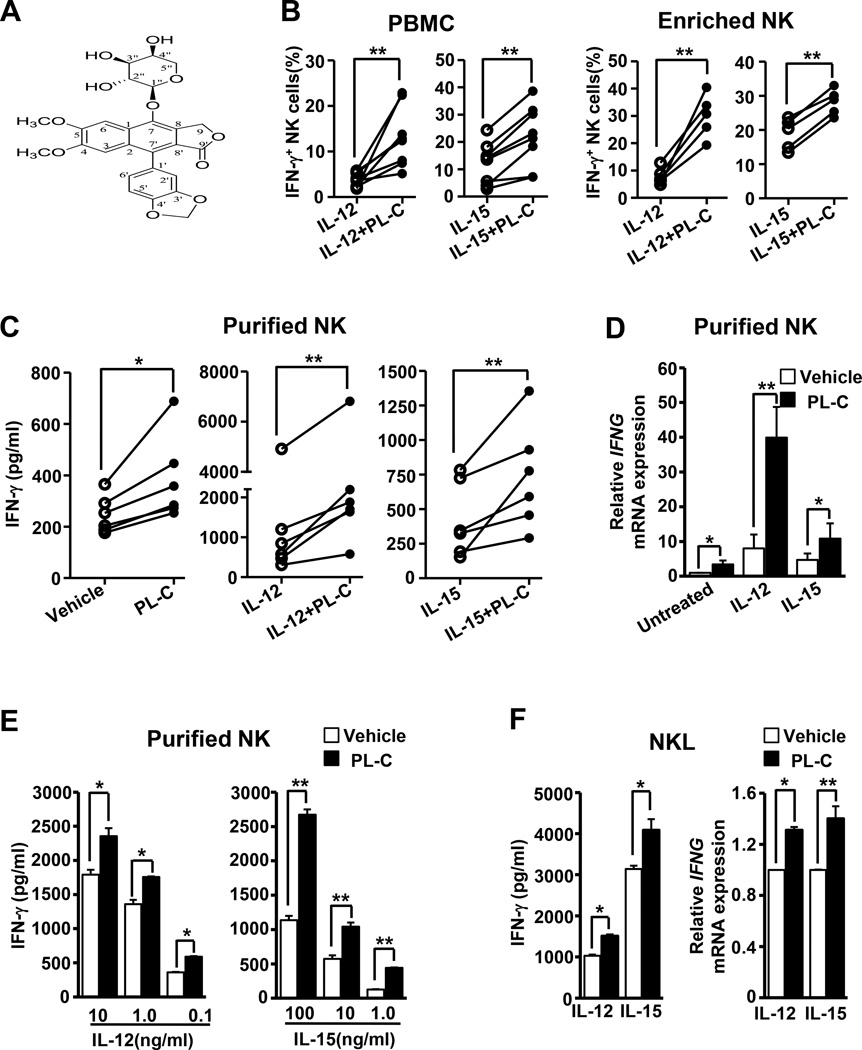

We were initially interested in over 50 candidate compounds (e.g. curcumin, β-glucan, etc.) isolated from edible or non-edible plants, which we screened for their capacity to enhance human NK cell activity. We found that a diphyllin lignan, PL-C (Fig. 1A), which can be isolated from both edible (e.g. Phyllanthus reticulatus) and non-edible (e.g. Phyllanthus poilanei) plants of the Phyllanthus genus collected from parts of Asia (Fig. S1A) (47, 48), was able to enhance IFN-γ production by NK cells. We first demonstrated that, when total PBMCs from healthy donors were cultured with PL-C in the presence of the cytokines IL-12 or IL-15 (stimulators of IFN-γ in NK cells, and each constitutively expressed in vivo (49)), intracellular staining for IFN-γ protein assessed via flow cytometric analysis indicated that NK cell IFN-γ production was significantly increased (Fig. 1B left). In addition, PL-C also significantly enhanced IFN-γ production in enriched NK cells in the presence of IL-12 or IL-15 (Fig. 1B right). To determine whether PL-C directly or indirectly act on NK cells to enhance their IFN-γ production, we purified NK cells (purity ≥ 99.5%) from total PBMCs via FACS and measured the level of IFN-γ secretion from the purified NK cells using ELISA. Interestingly, PL-C induced NK cell secretion of IFN-γ even in the absence IL-12 or IL-15 (Fig. 1C, left panel). PL-C also enhanced NK cell IFN-γ secretion in the presence of IL-12 or IL-15 stimulation (Fig. 1C, middle and right panels). Statistical analysis indicated a synergistic effect of IL-12 and PL-C on IFN-γ expression (Fig. S1B). Our data also showed that PL-C induced IFN-γ gene (IFNG) expression at the transcriptional level regardless of whether it was added alone or in the presence of IL-12 or IL-15 (Fig. 1D). When tested at a much lower concentration of IL-12 (1 and 0.1 ng/ml) or IL-15 (10 and 1 ng/ml), PL-C could also promote IFN-γ production in purified primary NK cells (Fig. 1E). Increased IFN-γ secretion and IFNG mRNA transcription were also found in the IL-2-dependent NK cell line, NKL (Fig. 1F). We found that the majority of IFN-γ-producing cells were NK cells, while there were few if any CD4+ or CD8+ T cells responding to PL-C stimulation in combination with IL-12 or IL-15 (Fig. S2A). Of note, PL-C showed no effect on NK cell cytotoxicity against the K562 cell line (data not shown) or multiple myeloma cell lines, ARH-77 (Fig. S2B) and MM.1S (data not shown), regardless of whether cells were incubated in media alone, with IL-12, or with IL-15. Consistent with this, expression of cytotoxicity-associated genes such as Granzyme A, Granzyme B, Perforin, and Fas ligand were also unaffected by PL-C when costimulated with IL-12 or IL-15 (Fig. S2C).

Figure 1. PL-C enhances IFN-γ production in human primary NK cells.

(A) Chemical structure of PL-C. (B) Healthy donor PBMCs (left) or enriched NK cells (right) were treated with DMSO vehicle control or 10 µM PL-C for 18 hours in the presence of IL-12 (10 ng/ml) or IL-15 (100 ng/ml). The cells were harvested and analyzed by intracellular flow cytometry to determine the frequency of IFN-γ+ cells in CD56+CD3− NK cells (n = 8 for PBMC and n = 5 for enriched NK). (C) Highly purified (≥ 99.5%) human primary NK cells were treated with 10 µM PL-C for 18 hours to determine the levels of IFN-γ secretion. IFN-γ secretion from treatment with PL-C alone (left) or in combination with IL-12 (10 ng/ml, middle) or IL-15 (100 ng/ml) (right) is shown. (D) Cells were treated as described in (C) and harvested at 12 hours. IFNG mRNA expression were assessed by real-time RT-PCR and the relative IFNG mRNA expression of each treatment was normalized to untreated vehicle control in the same donor. Data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. (n = 6 in each treatment; error bars represent S.E.M.). * and ** indicate P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, which denote statistical comparison between the two marked treatment groups (B, C and D). (E) Highly purified ((≥ 99.5%) primary human NK cells were treated with 10 µM PL-C in combination with various concentrations of IL-12 (10, 1, 0.1 ng/ml) or IL-15 (100, 10, 1 ng/ml) for 24 hours to determine the levels of IFN-γ secretion. Representative data from 1 out of 3 donors with the similar data are shown. * and ** indicate P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, which denote statistical comparison between the two marked treatment groups and are calculated from data of all tested donors. (F) NKL cells were treated with 10 µM PL-C in the presence of IL-12 or IL-15 for 18 hours or 12 hours to determine the levels of IFN-γ secretion (left) or IFNG mRNA (right) expression respectively. Data shown represent at least 3 independent experiments. * and ** indicate P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, compared to vehicle control. Error bars represent S.D.

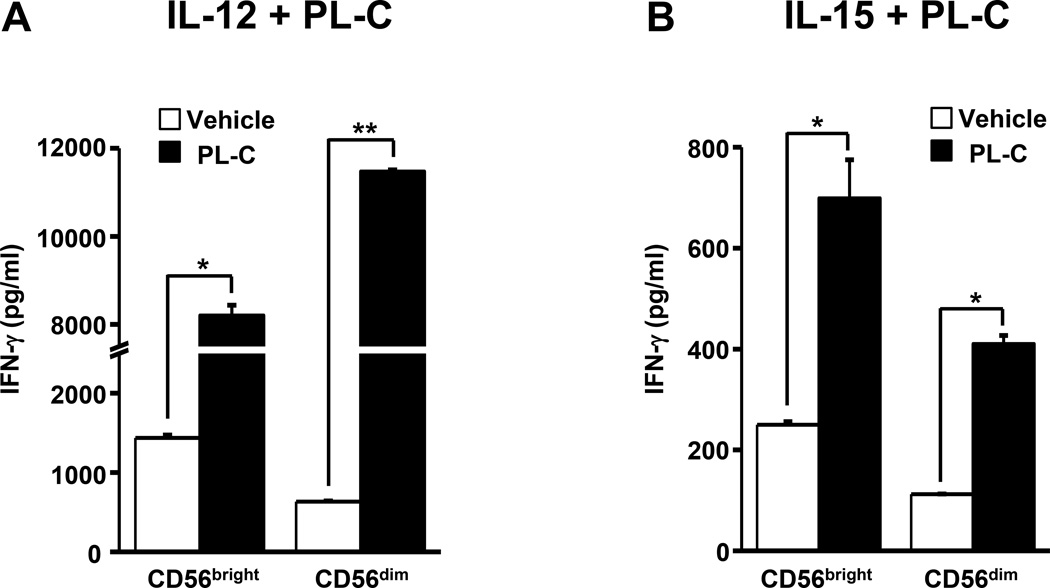

PL-C induces IFN-γ production in both CD56bright and CD56dim human NK cell subsets

Based on the relative density of CD56 surface expression, mature human NK cells can be phenotypically divided into CD56bright and CD56dim subsets. Human peripheral blood NK cells are comprised of ~10% CD56bright NK cells and ~90% CD56dim NK cells (50). Cytokine-activated CD56bright NK cells proliferate and secrete abundant IFN-γ, but display minimal cytotoxic activity at rest; in contrast, CD56dim NK cells have little proliferative capacity and produce negligible amounts of cytokine-induced IFN-γ, but are highly cytotoxic at rest (50). We found that during co-stimulation with IL-12 or IL-15, IFN-γ secretion from both CD56bright and CD56dim NK cells was enhanced by PL-C when compared to parallel cultures treated with a vehicle control (Fig. 2A and 2B). Noticeably, when co-stimulated with PL-C and IL-12, in some donors, CD56dim NK cells even produce more IFN-γ than CD56bright NK cells, as previously reported when NK cells recognize tumor cells (51, 52).

Figure 2. PL-C activates both CD56dim and CD56bright NK cells to secrete IFN-γ.

(A) Enriched NK cells were sorted via FACS into CD56dim and CD56bright NK cells based on the relative density of CD56 expressed on the cell surface. CD56dim and CD56bright NK cells were treated with 10 µM PL-C in the presence of IL-12 (10 ng/ml) for 18 hours and assessed for the levels of IFN-γ secretion. (B) Cells were isolated, treated and analyzed as in (A), but in the presence of IL-15 (100 ng/ml) instead of IL-12. Representative data from 1 out of at least 3 donors with similar results are shown. * and ** indicate P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, which denote statistical comparison between the two marked treatment groups and are calculated from data of all tested donors (A and B). Error bars represent S.D.

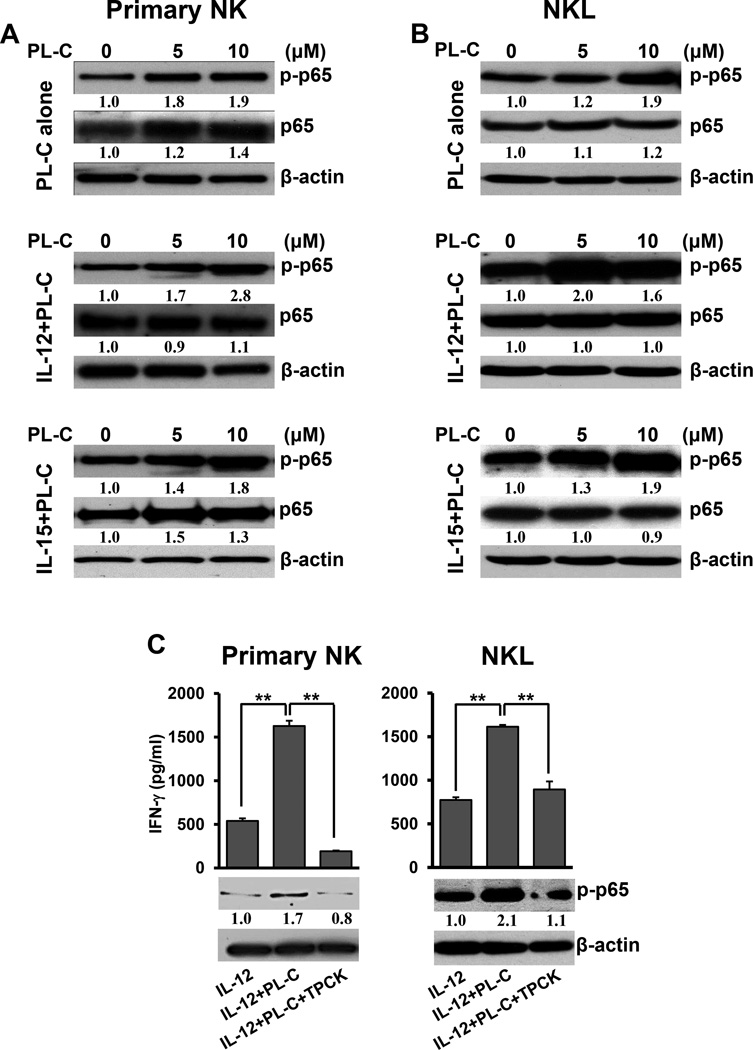

Induction of IFN-γ production by PL-C in human NK cells is correlated with activation of NF-κB signaling

Cytokine-induced IFN-γ production occurs mainly through the JAK-STATs, T-BET, MAPK, or NF-κB signaling pathways (29). Transcription factors in these signaling pathways associate with corresponding binding sites in the regulatory elements of the IFNG gene, subsequently enhancing IFNG mRNA synthesis (29). Therefore, we determined which of these signaling pathways participate in the PL-C-mediated IFN-γ induction in NK cells. We found that NF-κB p65 phosphorylation increased upon stimulation of primary NK cells and the NKL cell line with PL-C alone, while the level of total p65 was less or negligibly changed (Fig. 3A and 3B, upper panels). Similarly, the substantial increase of p65 phosphorylation but not total p65 was also observed when primary NK cells or NKL cells were treated with PL-C in the presence of IL-12 or IL-15 (Fig. 3A and 3B, middle and bottom panels). No significant change in the level of p65 transcript was observed in primary NK cells and NKL cells (data not shown). Next, we assessed whether PL-C affects IL-12R or IL-15R and their downstream STAT signaling pathways. When co-treated with IL-12, PL-C down-regulated mRNA expression of IL-12Rβ1, IL-12Rβ2 and IL-15Rα. However, when co-treated with IL-15, PL-C had no obvious effect on all IL-12R or IL-15R except for a moderate downregulation of IL-12Rβ1 (Fig. S3A). We did not observe any upregulation of total or phosphorylated STAT3, STAT4, and STAT5 in either purified primary NK or NKL cells. There was no significant change of T-BET in either purified primary NK cells or NKL cells being treated with PL-C (Fig. S3B and S3C). To further explore NF-κB involvement in PL-C-mediated enhancement of NK cell IFN-γ production, we utilized the NF-κB inhibitor TPCK, as it has been shown to directly modify thiol groups on Cys-179 of IKKβ and Cys-38 of p65/RelA, thereby inhibiting NF-κB activation (53). In purified primary NK cells and the NKL cell line, we found that TPCK indeed inhibited PL-C-induced p65 phosphorylation, and this was correlated with an inhibition of PL-C-induced IFN-γ secretion (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. PL-C increases the phosphorylation of p65 in human primary NK and NKL cells.

(A) Purified primary human NK cells were treated with 5 and 10 µM PL-C for 18 hours. The cells were harvested and lysed for immunoblotting using p65 and phosphorylated p65 (p-p65) antibodies. β-actin immunoblotting was included as the internal control. Data shown are for treatment with PL-C alone (top) or in combination with IL-12 (10 ng/ml) (middle) or IL-15 (100 ng/ml) (bottom), and are the representative plots of 4 donors with similar results. Numbers under each lane represent quantification of p-p65 or p65 via densitometry, after normalizing to β-actin. (B) NKL cells were treated, and data are presented as described in (A). Data from 1 of 3 independent experiments with similar results are shown. (C) Purified primary human NK (left) or NKL cells (right) were co-treated with 10 µM PL-C and IL-12 (10 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of the NF-κB inhibitor TPCK (10 µM) for 18 hours. Supernatants were assayed for IFN-γ secretion (top) and cells were harvested and lysed for immunoblotting of p-p65 (bottom). Representative data from 1 out of 3 donors with the similar data (left panel) and the summary of three independent experiments with similar results (right panel) are shown. ** indicates P < 0.01, and error bars represent S.D.

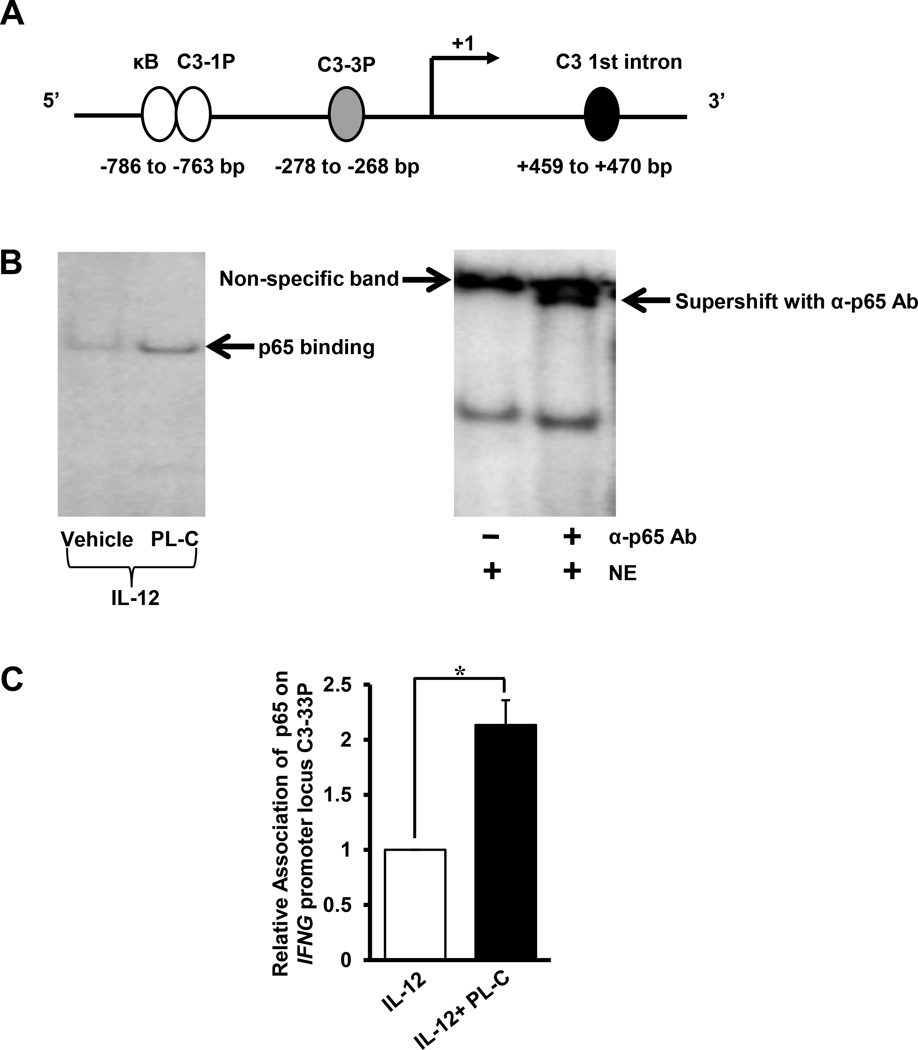

PL-C augments binding of p65 to the IFNG promoter in NK cells following PL-C stimulation

Since above we showed that PL-C induced NF-κB activity and also enhanced IFN-γ production in NK cells, we next investigated whether PL-C would facilitate the binding of NF-κB to the promoter of the IFNG gene in these cells. Four different NF-κB binding sites at the IFNG locus – κB, C3-1P, C3-3P, and C3 1st intron – have been previously reported (45) (Fig. 4A). EMSA using a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide containing the C3-3P NF-κB binding site of the IFNG promoter indicated that nuclear extracts prepared from purified primary NK cells treated with PL-C and IL-12 formed more DNA-protein complexes than those treated with IL-12 alone (Fig. 4B, left panel). The presence of p65 in the DNA-protein complexes was demonstrated by antibody gel supershift assay using anti-p65 antibodies (Fig. 4B, right panel). To find physiologically relevant evidence that PL-C augmented binding of p65 to the IFNG promoter, a ChIP assay was undertaken. Using primary NK cells purified from healthy donors, we found that treatment with PL-C in the presence of IL-12 enhanced p65 binding to the C3-3P binding site on the IFNG promoter when compared to IL-12-treated primary NK cells (Fig. 4C). No consistent results of ChIP assays among different donors showed that PL-C induced binding of p65 to the previously characterized κB, C3-1P and C3 1st intron NF-κB binding sites on the IFNG promoter (data not shown).

Figure 4. PL-C augments the binding of p65 to the IFNG promoter in human NK cells.

(A) Schematic of IFNG promoter potential binding sites for p65 (45). (B) NK cells purified from healthy donors were treated with 10 µM PL-C or DMSO vehicle control in the presence of IL-12 (10 ng/ml) for 12 hours. Cell pellets were harvested for nuclear extraction, followed by EMSA with a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide containing the C3-3P NF-κB p65 binding site of the IFNG promoter. Data shown represent 1 out of 3 donors with similar results. (C) Cells were treated as described in (B), and the cell pellets were harvested to extract protein for ChIP assay of p65 binding to the IFNG promoter locus C3-3P. Mean of relative association of p65 at the IFNG promoter locus C3-3P from three independent experiments is shown. * indicates P < 0.05, compared to cells treated with IL-12 alone. Error bars represent S.D.

PL-C augments TLR-NF-κB signaling in human NK cells

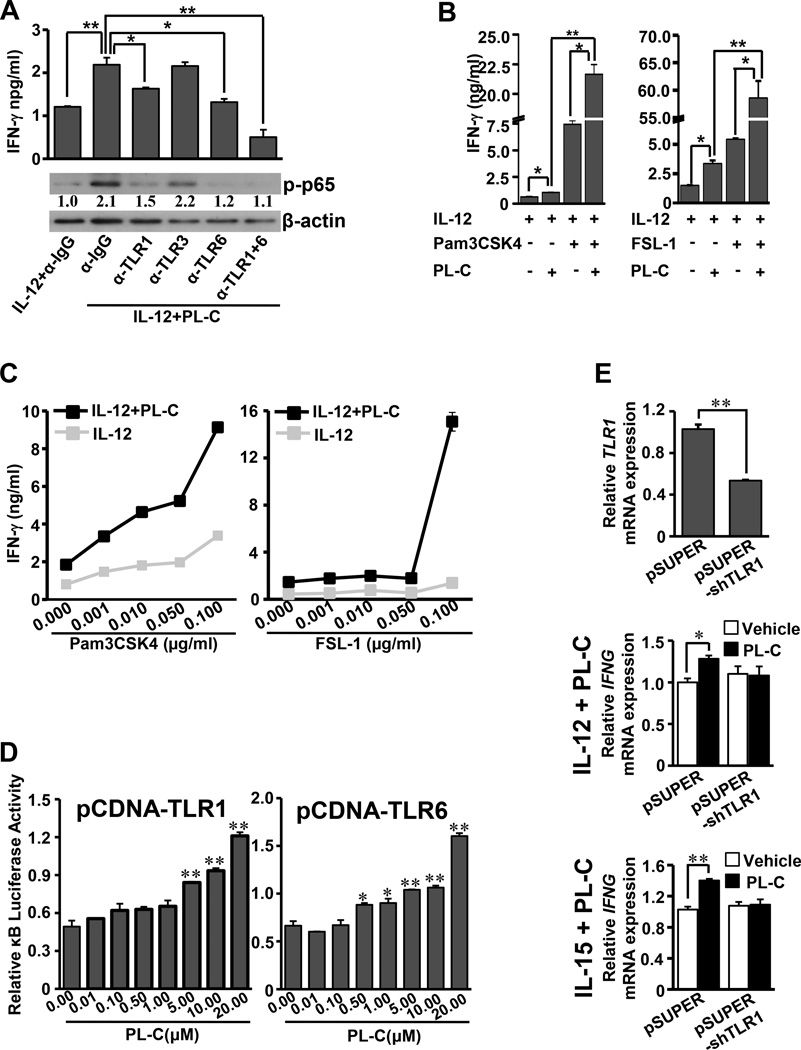

TLR signaling is upstream of NF-κB signaling, and activation of TLRs lead to a robust downstream TLR/IRAK-2/NF-κB-mediated induction of cytokine gene expression in immune cells (34). Therefore, we next determined whether TLRs mediated PL-C-induced IFN-γ production by human NK cells. Others and we have found that human NK cells mainly express TLR1, TLR3, and TLR6 (41, 54). We thus started the experiment by antibody blocking of these TLRs. It was found that blockade of TLR1 or TLR6 in primary NK cells significantly reduced PL-C-mediated induction of IFN-γ, while blockade of TLR3 had no significant effect on NK cell activation. Combined blockade of TLR1 and TLR6 reduced PL-C-enhanced NK cell IFN-γ expression to levels lower than those seen with blockade of either TLR1 or TLR6 (Fig. 5A, top panel). To determine if the effect of blocking antibodies on PL-C-induced IFN-γ production is likely mediated through the NF-κB signaling pathway, we examined the phosphorylation level of p65 induced by PL-C in the presence and absence of the TLR blocking antibodies. Consistently, blockade of TLR1 and/or TLR6 also inhibited PL-C-induced phosphorylation of p65, suggesting that PL-C-induced INF-γ production occurs at least in part through the TLR1/6-NF-κB signaling pathway (Fig. 5A, bottom panel). We next examined if PL-C could affect the expression of TLR1 and TLR6. No obvious changes in TLR1 or TLR6 gene expression were observed after treatment with PL-C alone or in the presence of IL-12 (data not shown). To further explore whether PL-C would augment TLR-mediated IFN-γ induction, NK cells were treated with 10 µM PL-C combined with a ligand of each of the two aforementioned TLRs in the presence of IL-12. PL-C enhanced IFN-γ production induced by Pam3CSK4 (TLR1/2 ligand) or FSL-1 (TLR6/2 ligand) in the presence of IL-12 when the ligands were at the previously reported concentration of 1 µg/ml (Fig. 5B). We also found that PL-C enhanced Pam3CSK4- and FSL-1-induced IFN-γ production in the presence of IL-12 when the ligands were added at various concentrations lower than 1 µg/ml (Fig. 5C). To further confirm that PL-C activates the TLR-NF-κB signaling pathway, we co-transfected TLR1 or TLR6 with pGL-3κB-Luc and control plasmid pRL-TK renilla-luciferase plasmids. PL-C treatment was found to induce luciferase reporter activity in a dose-dependent fashion, suggesting an increase of NF-κB binding to the κB binding sites (Fig. 5D). Finally, we knocked down TLR1 expression in NKL cells by using TLR1 shRNA to validate that TLR1 signaling participated in PL-C-mediated enhancement of NK cell IFN-γ production. After confirming TLR1 was successfully knocked down in TLR1 shRNA NKL cells with approximately 50% TLR1 mRNA inhibition (Fig. 5E, upper panel), we found the increase in IFN-γ production mediated by PL-C vanished when cotreated with IL-12 or IL-15 in these cells (Fig. 5E, middle and bottom panel). These data suggest that PL-C directly activates TLR-NF-κB signaling pathway to enhance IFN- γ production in NK cells.

Figure 5. TLR1 and/or TLR6 mediate IFN-γ induction by PL-C in human NK cells.

(A) Human NK cells were purified and pretreated with a non-specific IgG or anti-TLR1, anti-TLR3, anti-TLR6 or the combination of TLR1 and TLR6 blocking antibodies (α) for 1 hour. Cells were then treated with PL-C and IL-12 (10 ng/ml) for another 18 hours and were assessed for IFN-γ secretion. Data shown are representative of one of 6 different donors with similar results. * and ** indicate P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, which denote statistical comparison between the two marked treatment groups and are calculated from data of all tested donors. (B) Cell pellets were harvested from the above mentioned samples in (A), followed by p-p65 immunoblotting. Numbers underneath each lane represent quantification of protein by densitometry, normalized to β-actin. Representative data from 1 out of 6 donors with similar results are shown in (A and B). (C) Purified NK cells were treated with Pam3CSK4 (1 µg/ml, TLR1/2 ligand), or FSL-1 (1 µg/ml, TLR6/2 ligand) in the presence of IL-12 (10 ng/ml), with or without PL-C (10 µM) for 18 hours, and then supernatants were harvested to assay for IFN-γ secretion. Data shown are representative of 1 of 6 donors with similar results. * and ** indicate P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, which denote statistical comparison between the two marked treatment groups and are calculated from data of all tested donors. (D) Purified primary NK cells were treated with various low concentration of Pam3CSK4, or FSL-1 with or without PL-C (10 µM) in the presence of IL-12 (10 ng/ml), and then supernatants were harvested to assay for IFN-γ secretion. Data shown are representative 1 out of 3 donors with similar results. Error bars indicate S.D. (E) 293T cells were transfected with TLR1 (0.5 µg), or TLR6 (0.5 µg) expression plasmid along with pGL-3×κB-luc (1 µg) and pRL-TK renilla-luciferase control plasmids (5 ng, Promega). Cells were then treated with various concentration of PL-C for another 24 hours with fresh medium, and DMSO was included as vehicle control. The ratio of the firefly to the renilla luciferase activities was used to show the relative luciferase activity, which corresponded to NF-κB activation. * and ** indicate P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, compared to vehicle control. Error bars represent S.D. (F) NKL cells were infected with pSUPER or pSUPER-shTLR1 retroviruses and sorted based on GFP expression. Confirmation of TLR1 mRNA knockdown is shown in the left panel. Both the vector-transduced cells (pSUPER) and the TLR1 knockdown cells (pSUPER-shTLR1) were treated with or without PL-C in the presence or absence of IL-12 or IL-15. Cell pellets were harvested at 12 hours for real-time RT-PCR. The relative IFNG mRNA expression induced by PL-C under IL-12 (10 ng/ml) or IL-15 (100 ng/ml) was shown in middle or right panel, respectively. The summary of three independent experiments with similar results are shown. ** indicates P < 0.01, and error bars represent S.D.

Discussion

NK cells are an important lymphocyte subset with a capacity to destroy tumor cells and clear viral infection upon first encounter (50). Enhancement of NK cell activity for prevention or treatment of cancer and viral infection is a central goal in the field of immunology. NK cell activation can be achieved through exposure to cytokines such as IL-2 (55) and IL-12 (56, 57). However, this approach has had limited success in part due to the toxicity resulting from the systemic administration of these cytokines (58) and the pleotropic effects of these agents. One example of the latter is that IL-2 induces expansion of Treg cells (22, 23), which in turn dampen NK cell functions (59). What seems to be most useful for prevention of cancer or infection in those susceptible individuals would be an agent that produced a modest induction of NK function with relative specificity among immune effector cells.

In this study, we found that PL-C, a diphyllin lignan, which can be isolated from both edible and non-edible plants of the Phyllanthus genus, was able to specifically enhance IFN-γ production by human NK cells. Mechanistically, we show that PL-C may sense TLR1 and/or TLR6 on human NK cells which in turn activates the NF-κB subunit p65 to bind to the proximal region of the IFNG promoter. PL-C has only negligible effects on T cell effector function, which is consistent with higher expression of TLR1 and TLR6 in NK cells than in T cells (54). This increases the likelihood that pleiotropic effects on immune activation and systemic toxicity of the agent might be limited.

Targeting NK cells, especially by natural products, appears to be a rational approach for the prevention of cancer. In support of this, an 11-year follow-up population study of 3,625 people > 40 years of age demonstrated that the potency of peripheral blood NK cells for lysing tumor cell targets was inversely associated with cancer risk (60). Moreover, as cancer susceptibility increases with age, NK cell potency subsides with age (61, 62). NK cell activity is correlated with relapse-free survival in some cancer patients, e.g. those with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (63). NK cells should be excellent tools to control tumor development at the early stage as they play a critical role of tumor surveillance. Once cancer is established, tumor cells can inactivate immune cells, including NK cells, which can result in an immunosuppressive microenvironment (64). Indeed, NK cell function is found to be anergic or impaired in various types of cancer (65, 66). Moreover, at the late stage of cancer development, the immune system including NK cells and IFN-γ may edit tumor cells and facilitate their escape from immune destruction (6, 67, 68). Therefore, we think NK cells may play a more critical role in prevention than for treatment of cancer, and their selective modulation is important in this scenario. However, this is hurdled by the lack of safe and effective NK cell stimulators.

Our findings provide a new avenue to prevent or treat cancer using natural products through enhancing NK cell immunosurveillance. Like many other natural products, PL-C is likely relatively safe compared to cytokines, and this can be evidenced by that substantial toxicities were not observed in mice treated with up to 500 mg of PL-C per kg of body weight (data not shown). Developing less toxic drugs is important for preventing or treating some cancers, especially for those which are dominant in children or in elderly populations. One example for this is AML. AML is a disease that primarily affects older adults: the median age at diagnosis is over 65 (69, 70). The 5-year survival rate of AML remains under 10% (71). Elderly AML patients are less able than younger patients to tolerate effective therapies such as intensive chemotherapy and allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Therefore, PL-C may present a new approach to prevent or treat this disease.

PL-C selectively activates NK cells through regulating production of cytokines, especially IFN-γ. Therefore, in vivo, PL-C will most likely achieve its cancer prevention or treatment effects through increase NK cell IFN-γ secretion to activate other innate immune components such as macrophages (72) as well as adaptive immune components such as CD8+ T cells (11, 12). Unlike cytokine stimulation, which usually induces both IFN-γ production and cytotoxicity, the selective induction of NK cell IFN-γ production by PL-C also provides a good opportunity to separate the two major functions of NK cells, cytokine production and cytotoxicity, especially when cytotoxicity may cause damage to normal tissues, e.g. in the graft-versus-host disease and pregnancy contexts. Interestingly, this separation naturally exists in our immune system as CD56bright and CD56dim NK cells have differential functions in terms of IFN-γ production and cytotoxicity, and some tissue or organs predominantly have only one of these subsets. For example, the lymph nodes (73) and the uterus (74) almost exclusively contain CD56bright NK cells.

Mechanistically, we found that PL-C may sense TLR1 and TLR6 to activate NF-κB signaling in NK cells, leading to the enhancement of IFN-γ production. In support of this, knockdown of TLR1 by shRNA eliminated the effect of PL-C on IFN-γ production in NKL cells. Others and we have previously demonstrated that TLR1 and TLR6 are substantially expressed in human NK cells (41, 54). Interestingly, TLR1 and TLR6 share 56% amino acid sequence identity (75) and both complex with TLR2 to recognize bacterial lipoproteins and lipopeptides (76). TLR1 and TLR6 may thus possess a common binding site for PL-C. It is unknown whether PL-C’s ability to sense TLR1 and TLR6 requires binding to their partner TLR2, as TLR2 has very low expression in NK cells (54). It is possible that triggering TLR1 and TLR6 signaling may only require a minimal expression level of TLR2, as we found for NK precursor cells, which respond to IL-15 but lack expression of the IL-15R chains responsible for signaling at a level detectable by flow cytometry (77). Regardless, our current study may have identified a potential novel agonist for TLR1 and/or TLR6. In support of this, we found that PL-C also activates TLR1 and TLR6 downstream NF-κB signaling in NK cells, and transfection of TLR1 or TLR6 induces NF-κB reporter activity. Moreover, our data suggest that PL-C either lowers the threshold for or synergize with TLR1 and TLR6 ligands to activate NK cells.

In summary, we identified a natural product, PL-C, which effectively stimulates NK cells to secrete IFN-γ. PL-C appears to act through TLR1 and TLR6, which subsequently activate NF-κB signaling to induce binding of p65 to the proximal region of the IFNG promoter in NK cells. Our work would suggest that additional studies to understand the role of this natural product in prevention of cancer or infection in select populations are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Hsiaoyin C. Mao for flow cytometry technical and scientific support.

This project was supported in part by grants from National Institutes of Health (CA155521 and OD018403 to J.Y., CA163205 and CA068458 to M.A.C., and CA125066 to A.D.K.), a 2012 scientific research grant from the National Blood Foundation (to J.Y.), an institutional research grant (IRG-67-003-47) from the American Cancer Society (to J.Y.), and The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center Pelotonia idea grants (to J.Y.). This research was also supported by a grant from the Natural Science Foundation of China (81273507 to X. L).

Abbreviations used in this article

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- ChIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- HEK293T

Human embryonic kidney 293T

- PL-C

phyllanthusmin C

- TPCK

N-tosyl-L-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone

Footnotes

Disclosure Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Smyth MJ, Hayakawa Y, Takeda K, Yagita H. New aspects of natural-killer-cell surveillance and therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:850–861. doi: 10.1038/nrc928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vivier E, Tomasello E, Baratin M, Walzer T, Ugolini S. Functions of natural killer cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:503–510. doi: 10.1038/ni1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Novelli F, Casanova JL. The role of IL-12, IL-23 and IFN-gamma in immunity to viruses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:367–377. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SH, Miyagi T, Biron CA. Keeping NK cells in highly regulated antiviral warfare. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lanier LL. Evolutionary struggles between NK cells and viruses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:259–268. doi: 10.1038/nri2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The roles of IFN gamma in protection against tumor development and cancer immunoediting. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:95–109. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(01)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane A, Yang I. Interferon-gamma in brain tumor immunotherapy. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2010;21:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tu SP, Quante M, Bhagat G, Takaishi S, Cui G, Yang XD, Muthuplani S, Shibata W, Fox JG, Pritchard DM, Wang TC. IFN-gamma inhibits gastric carcinogenesis by inducing epithelial cell autophagy and T-cell apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4247–4259. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hacker S, Dittrich A, Mohr A, Schweitzer T, Rutkowski S, Krauss J, Debatin KM, Fulda S. Histone deacetylase inhibitors cooperate with IFN-gamma to restore caspase-8 expression and overcome TRAIL resistance in cancers with silencing of caspase-8. Oncogene. 2009;28:3097–3110. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin-Fontecha A, Thomsen LL, Brett S, Gerard C, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Induced recruitment of NK cells to lymph nodes provides IFN-gamma for T(H)1 priming. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1260–1265. doi: 10.1038/ni1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kos FJ, Engleman EG. Requirement for natural killer cells in the induction of cytotoxic T cells. J Immunol. 1995;155:578–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ge MQ, Ho AW, Tang Y, Wong KH, Chua BY, Gasser S, Kemeny DM. NK Cells Regulate CD8+ T Cell Priming and Dendritic Cell Migration during Influenza A Infection by IFN-gamma and Perforin-Dependent Mechanisms. J Immunol. 2012;189:2099–2109. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watt SV, Andrews DM, Takeda K, Smyth MJ, Hayakawa Y. IFN-gamma-dependent recruitment of mature CD27(high) NK cells to lymph nodes primed by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:5323–5330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colucci F, Caligiuri MA, Santo JPDi. What does it take to make a natural killer? Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:413–425. doi: 10.1038/nri1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn GP, Koebel CM, Schreiber RD. Interferons, immunity and cancer immunoediting. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:836–848. doi: 10.1038/nri1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner K, Schulz P, Scholz A, Wiedenmann B, Menrad A. The targeted immunocytokine L19-IL2 efficiently inhibits the growth of orthotopic pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4951–4960. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jahn T, Zuther M, Friedrichs B, Heuser C, Guhlke S, Abken H, Hombach AA. An IL12-IL2-antibody fusion protein targeting Hodgkin's lymphoma cells potentiates activation of NK and T cells for an anti-tumor attack. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44482. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strengell M, Matikainen S, Siren J, Lehtonen A, Foster D, Julkunen I, Sareneva T. IL-21 in synergy with IL-15 or IL-18 enhances IFN-gamma production in human NK and T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:5464–5469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Son YI, Dallal RM, Mailliard RB, Egawa S, Jonak ZL, Lotze MT. Interleukin-18 (IL-18) synergizes with IL-2 to enhance cytotoxicity, interferon-gamma production, and expansion of natural killer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:884–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Carlo E, Comes A, Orengo AM, Rosso O, Meazza R, Musiani P, Colombo MP, Ferrini S. IL-21 induces tumor rejection by specific CTL and IFN-gamma-dependent CXC chemokines in syngeneic mice. J Immunol. 2004;172:1540–1547. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baer MR, George SL, Caligiuri MA, Sanford BL, Bothun SM, Mrozek K, Kolitz JE, Powell BL, Moore JO, Stone RM, Anastasi J, Bloomfield CD, Larson RA. Low-dose interleukin-2 immunotherapy does not improve outcome of patients age 60 years and older with acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission: Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study 9720. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4934–4939. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.0472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gowda A, Ramanunni A, Cheney C, Rozewski D, Kindsvogel W, Lehman A, Jarjoura D, Caligiuri M, Byrd JC, Muthusamy N. Differential effects of IL-2 and IL-21 on expansion of the CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ T regulatory cells with redundant roles in natural killer cell mediated antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. MAbs. 2010;2:35–41. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.1.10561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah MH, Freud AG, Benson DM, Jr, Ferkitich AK, Dezube BJ, Bernstein ZP, Caligiuri MA. A phase I study of ultra low dose interleukin-2 and stem cell factor in patients with HIV infection or HIV and cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3993–3996. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson MJ, Chang HC, Pelloso D, Kaplan MH. Impaired interferon-gamma production as a consequence of STAT4 deficiency after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for lymphoma. Blood. 2005;106:963–970. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang HC, Han L, Goswami R, Nguyen ET, Pelloso D, Robertson MJ, Kaplan MH. Impaired development of human Th1 cells in patients with deficient expression of STAT4. Blood. 2009;113:5887–5890. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-179820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lupov IP, Voiles L, Han L, Schwartz A, Rosa M, De La, Oza K, Pelloso D, Sahu RP, Travers JB, Robertson MJ, Chang HC. Acquired STAT4 deficiency as a consequence of cancer chemotherapy. Blood. 2011;118:6097–6106. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-341867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salem ML, Gillanders WE, Kadima AN, El-Naggar S, Rubinstein MP, Demcheva M, Vournakis JN, Cole DJ. Review: novel nonviral delivery approaches for interleukin-12 protein and gene systems: curbing toxicity and enhancing adjuvant activity. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26:593–608. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amos SM, Duong CP, Westwood JA, Ritchie DS, Junghans RP, Darcy PK, Kershaw MH. Autoimmunity associated with immunotherapy of cancer. Blood. 2011;118:499–509. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-325266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoenborn JR, Wilson CB. Regulation of interferon-gamma during innate and adaptive immune responses. Adv Immunol. 2007;96:41–101. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(07)96002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watford WT, Hissong BD, Bream JH, Kanno Y, Muul L, O'Shea JJ. Signaling by IL-12 and IL-23 and the immunoregulatory roles of STAT4. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:139–156. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kannan Y, Yu J, Raices RM, Seshadri S, Wei M, Caligiuri MA, Wewers MD. IkappaBzeta augments IL-12- and IL-18-mediated IFN-gamma production in human NK cells. Blood. 2011;117:2855–2863. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-294702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Napetschnig J, Wu H. Molecular basis of NF-kappaB signaling. Annu Rev Biophys. 2013;42:443–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195–2224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li JW, Vederas JC. Drug discovery and natural products: end of an era or an endless frontier? Science. 2009;325:161–165. doi: 10.1126/science.1168243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan L, Chai H, Kinghorn AD. The continuing search for antitumor agents from higher plants. Phytochem Lett. 2010;3:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harvey AL. Natural products in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:894–901. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. J Nat Prod. 2012;75:311–335. doi: 10.1021/np200906s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan L, Chai HB, Kinghorn AD. Discovery of new anticancer agents from higher plants. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2012;4:142–156. doi: 10.2741/257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bindseil KU, Jakupovic J, Wolf D, Lavayre J, Leboul J, Pyl Dvan der. Pure compound libraries; a new perspective for natural product based drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2001;6:840–847. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(01)01856-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He S, Chu J, Wu LC, Mao H, Peng Y, Alvarez-Breckenridge CA, Hughes T, Wei M, Zhang J, Yuan S, Sandhu S, Vasu S, Benson DM, Jr, Hofmeister CC, He X, Ghoshal K, Devine SM, Caligiuri MA, Yu J. MicroRNAs activate natural killer cells through Toll-like receptor signaling. Blood. 2013;121:4663–4671. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-441360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu J, Wei M, Becknell B, Trotta R, Liu S, Boyd Z, Jaung MS, Blaser BW, Sun J, Benson DM, Jr, Mao H, Yokohama A, Bhatt D, Shen L, Davuluri R, Weinstein M, Marcucci G, Caligiuri MA. Pro- and antiinflammatory cytokine signaling: reciprocal antagonism regulates interferon-gamma production by human natural killer cells. Immunity. 2006;24:575–590. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu J, Mao HC, Wei M, Hughes T, Zhang J, Park IK, Liu S, McClory S, Marcucci G, Trotta R, Caligiuri MA. CD94 surface density identifies a functional intermediary between the CD56bright and CD56dim human NK-cell subsets. Blood. 2010;115:274–281. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-215491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bachmeyer C, Mak CH, Yu CY, Wu LC. Regulation by phosphorylation of the zinc finger protein KRC that binds the kappaB motif and V(D)J recombination signal sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:643–648. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sica A, Dorman L, Viggiano V, Cippitelli M, Ghosh P, Rice N, Young HA. Interaction of NF-kappaB and NFAT with the interferon-gamma promoter. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30412–30420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guttridge DC, Albanese C, Reuther JY, Pestell RG, Baldwin AS., Jr NF-kappaB controls cell growth and differentiation through transcriptional regulation of cyclin D1. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5785–5799. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma JX, Lan MS, Qu SJ, Tan JJ, Luo HF, Tan CH, Zhu DY. Arylnaphthalene lignan glycosides and other constituents from Phyllanthus reticulatus. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2012;14:1073–1077. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2012.712040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jansen PCM Plant Resources of Tropical Africa (Program) Dyes and tannins. Wageningen, Netherlands: PROTA Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stevceva L, Moniuszko M, Ferrari MG. Utilizing IL-12, IL-15 and IL-7 as Mucosal Vaccine Adjuvants. Lett Drug Des Discov. 2006;3:586–592. doi: 10.2174/157018006778194655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cells. Blood. 2008;112:461–469. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-077438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang X, Yu J. Target recognition-induced NK-cell responses. Blood. 2010;115:2119–2120. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-260448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fauriat C, Long EO, Ljunggren HG, Bryceson YT. Regulation of human NK-cell cytokine and chemokine production by target cell recognition. Blood. 2010;115:2167–2176. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-238469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ha KH, Byun MS, Choi J, Jeong J, Lee KJ, Jue DM. N-tosyl-L-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone inhibits NF-kappaB activation by blocking specific cysteine residues of IkappaB kinase beta and p65/RelA. Biochemistry. 2009;48:7271–7278. doi: 10.1021/bi900660f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hornung V, Rothenfusser S, Britsch S, Krug A, Jahrsdorfer B, Giese T, Endres S, Hartmann G. Quantitative expression of toll-like receptor 1–10 mRNA in cellular subsets of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sensitivity to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2002;168:4531–4537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang KS, Frank DA, Ritz J. Interleukin-2 enhances the response of natural killer cells to interleukin-12 through up-regulation of the interleukin-12 receptor and STAT4. Blood. 2000;95:3183–3190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robertson MJ, Soiffer RJ, Wolf SF, Manley TJ, Donahue C, Young D, Herrmann SH, Ritz J. Response of human natural killer (NK) cells to NK cell stimulatory factor (NKSF): cytolytic activity and proliferation of NK cells are differentially regulated by NKSF. J Exp Med. 1992;175:779–788. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.3.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chehimi J, Starr SE, Frank I, Rengaraju M, Jackson SJ, Llanes C, Kobayashi M, Perussia B, Young D, Nickbarg E, Wolf SF, Trinchieri G. Natural-Killer (Nk) Cell Stimulatory Factor Increases the Cytotoxic Activity of Nk Cells from Both Healthy Donors and Human-Immunodeficiency-Virus Infected Patients. J Exp Med. 1992;175:789–796. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.3.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosenberg SA, Lotze MT, Yang JC, Aebersold PM, Linehan WM, Seipp CA, White DE. Experience with the Use of High-Dose Interleukin-2 in the Treatment of 652 Cancer-Patients. Ann Surg. 1989;210:474–485. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198910000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ralainirina N, Poli A, Michel T, Poos L, Andres E, Hentges F, Zimmer J. Control of NK cell functions by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:144–153. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0606409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Imai K, Matsuyama S, Miyake S, Suga K, Nakachi K. Natural cytotoxic activity of peripheral-blood lymphocytes and cancer incidence: an 11-year follow-up study of a general population. Lancet. 2000;356:1795–1799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03231-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hazeldine J, Lord JM. The impact of ageing on natural killer cell function and potential consequences for health in older adults. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:1069–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shaw AC, Joshi S, Greenwood H, Panda A, Lord JM. Aging of the innate immune system. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tajima F, Kawatani T, Endo A, Kawasaki H. Natural killer cell activity and cytokine production as prognostic factors in adult acute leukemia. Leukemia. 1996;10:478–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jewett A, Tseng HC. Tumor induced inactivation of natural killer cell cytotoxic function; implication in growth, expansion and differentiation of cancer stem cells. J Cancer. 2011;2:443–457. doi: 10.7150/jca.2.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Critchley-Thorne RJ, Simons DL, Yan N, Miyahira AK, Dirbas FM, Johnson DL, Swetter SM, Carlson RW, Fisher GA, Koong A, Holmes S, Lee PP. Impaired interferon signaling is a common immune defect in human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9010–9015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901329106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guillot B, Portales P, Thanh AD, Merlet S, Dereure O, Clot J, Corbeau P. The expression of cytotoxic mediators is altered in mononuclear cells of patients with melanoma and increased by interferon-alpha treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:690–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:991–998. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.O'Sullivan T, Saddawi-Konefka R, Vermi W, Koebel CM, Arthur C, White JM, Uppaluri R, Andrews DM, Ngiow SF, Teng MW, Smyth MJ, Schreiber RD, Bui JD. Cancer immunoediting by the innate immune system in the absence of adaptive immunity. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1869–1882. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Estey E, Dohner H. Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet. 2006;368:1894–1907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yanada M, Naoe T. Acute myeloid leukemia in older adults. Int J Hematol. 2012;96:186–193. doi: 10.1007/s12185-012-1137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stein EM, Tallman MS. Remission induction in acute myeloid leukemia. Int J Hematol. 2012;96:164–170. doi: 10.1007/s12185-012-1121-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nathan CF. Identification of interferon-gamma as the lymphokine that activates human macrophage oxidative metabolism and antimicrobial activity. J Exp Med. 1983;158:670–689. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.3.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fehniger TA, Cooper MA, Nuovo GJ, Cella M, Facchetti F, Colonna M, Caligiuri MA. CD56bright natural killer cells are present in human lymph nodes and are activated by T cell-derived IL-2: a potential new link between adaptive and innate immunity. Blood. 2003;101:3052–3057. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.King A, Jokhi PP, Burrows TD, Gardner L, Sharkey AM, Loke YW. Functions of human decidual NK cells. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1996;35:258–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1996.tb00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jin MS, Kim SE, Heo JY, Lee ME, Kim HM, Paik SG, Lee H, Lee JO. Crystal structure of the TLR1-TLR2 heterodimer induced by binding of a tri-acylated lipopeptide. Cell. 2007;130:1071–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hopkins PA, Sriskandan S. Mammalian Toll-like receptors: to immunity and beyond. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;140:395–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02801.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Freud AG, Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cell development. Immunol Rev. 2006;214:56–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.